Abstract

Purpose

In order to counteract the obesity has epidemics, since current anti-obesity drugs effects remain limited, there is a need to provide new options. As a project aiming to assess potential anti obesity natural compounds, the effects of consumption of a minimal dose of green tea hydro alcoholic extract (GT) on adipocyte differentiation of 3T3L1 cell line were investigated.

Methods

Obesity was induced in female NMRI mice (which are less used overall) by the use of a high fat diet. Mice were divided into four groups of control (C), treated control (TC), obese (O) and treated obese (TO). TC and TO groups received 8 mg/Kg/day of GT for 8 weeks, and weighted weekly, after what biochemical and histological parameters were measured. GT was used at doses of 100,150 and 200 µg/ml on 3T3L1, and staining with Oil-red-O was done for estimation of fat droplet accumulation.

Results

Body weight was found to be affected significantly by GT. Blood glucose levels did not show significant changes between groups, while triglycerides levels of the O group was significantly higher than the C group, but the TO group showed no significant difference with the C group upon GT treatment. Liver and visceral fat tissues showed more normalized tissue and less fat accumulation in the TO group. TO and TC groups showed an ameliorated morphologic state of liver tissues. GT was also able to decrease fat droplet formation in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusions

Adding a minimal amount of GT to the daily consumption may have preventive effects on fat accumulation in healthy subjects, while in obese cases, GT shows significant therapeutic effect.

Keywords: Obesity, Green tea, High fat‐diet, NMRI mouse, 3T3L1, Adipogenesis

Introduction

There is a worldwide exponential increase of obesity cases [1]. Epidemiological studies have predicted global figures of 2.16 billion overweight and 1.2 billion obese people by the year 2030 [2]. Both these global health problems cause an impressive social and economic burden, associated with a range of diseases including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis and many types of cancers [3, 4].

Life style modifications have proven to be beneficial in delaying the appearance of metabolic diseases linked to obesity (such as diabetes), but are not easy to implement [5, 6]. On the other hand, due to severe side effects, withdrawal of marketing authorization has occurred for major anti-obesity drugs [7], and currently, alongside with new chemicals, natural products are seriously considered as a promising source for the next anti-obesity therapeutics [8, 9].

Obesity is related to an increase of adipogenesis which is due to an increase in the size or number of adipocytes. This complex process affects the normal functioning of the body via hormone sensitivity and gene expression. Several specific adipocytes genes are involved in adipocyte differentiation, such as sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), fatty acid synthase(FAS), peroxisome proliferator –activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and CCAAT enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBPα) that lead to fat accumulation and morphological changes in adipocytes [10]. An important signaling mechanism in adipocyte differentiation is the activation of Serine/threonine kinase Akt pathway by which insulin and some other growth factors stimulate adipogenesis [11] ; two significant enzymes which are key enzymes in lypolysis include lipoprotein lipase(LPL) and hormone- sensitive lipase(HSL) [12, 13].

Green tea (GT) (Camellia sinensis) belongs to the Theaceae family and contains different polyphenols, caffeine and amino acids. It is an ideal source of polyphenols, including the antioxidant catechins, and mainly Epicatechin gallate, Epigallocatechin, and Epicatechin [14]. Hydroalcoholic extract of tea has been shown to contain alkaloids (caffeine as major component), as well as phtalic acid and octadecenoic acid [15, 16]. Green tea (GT) has been used by Japanese and Chinese populations for centuries and is one of the most popular beverage besides water in Asian society. Tea drinking has been associated with reduction of serum cholesterol, prevention of low density lipoprotein oxidation, decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer [17, 18]. Green tea, either brewed or as an extract, has been suggested to have interesting anti-obesity potential in recent reviews [19, 20]. GT infusion exhibits strong inhibition activity against pancreatic lipase which is an important enzyme in dietary triacylglycerol absorption, and hydrolyzes triacylglycerols to monoacylglycerols and fatty acids [21]. GT has also been suggested to have protective effects against Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease [22], and ischemic damage [23], as well as anti-diabetic, antioxidants [24], and anti-aging effects [25] in experimental models. GT and its constituents are safe to ingest and does not cause mortality or toxicity effects in rodents upon acute and chronic use up to relatively high doses (e.g. 764 mg/kg body weight/day for male rats on a 90 days experiment on catechin) [26–29].

The current study aimed at investigating the potential anti-obesity effects of GT hydroalcoholic extract (GT ) treatment on female NMRI mice that were fed by a high fat-diet (female mice are overall less studied in these kind of investigation). Emphasis has been put on histology, and the used dose of the extract was adjusted to be comparable with drinking a minimal amount of green tea in vivo. GT effect on the differentiation of 3T3L1 preadipocytes to adipocytes has also been investigated as an indicator of adipogenesis and fat accumulation. We believe this mixed in vivo-in vitro approach and the minimal dose that has been used, would provide valuable new data on GT.

Materials and methods

Animals and diet

Thirty-two female NMRI mice were purchased from Pasteur institute (Karaj-Iran). They were allowed to acclimatize to animal house conditions for one week. During this period, they were fed by standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum. After adaptation, mice basic weights were 25 ± 2 g. All animals were maintained at a room temperature 22 ± 2 °C with relative humidity of 55–60 % and a 12 h light/dark cycle during eight weeks. After one week adaptation, the mice were randomly divided to four groups (n = 8): Control (C), Treated control (TC), Obese (O) and Treated obese (TO). (C) and (TC) groups were fed by standard chow diet, whereas (O) and (TO) groups were fed by a high fat diet [30] for eight weeks.

The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute (EMRI)(code: EC00250) in accordance with Helsinki declaration and guidelines of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education.

Green tea extract preparation

Dry green tea leaves were purchased from Tala Tea Co.(Tehran,Iran).The tea leaves (25 g) were ground and refluxed under steam bath in round bottom flask with double distilled water (1000ml)and ethanol (150ml)for 3 h. Collected extracts were centrifuged after filtration and then lyophilized under vacuum [31].

Treatment

(TC) and (TO) groups received green tea extract that was dissolved in boiled double distilled water to a dose equivalent to the extract content of a 50 ml cup of green tea (equivalent to 2 gr dry green tea leaves extraction), this amount was equal to 8 mg/Kg/day/ mouse. It should be noted that with regard to mice faster metabolic rate, translating this dose to humans would result into approximately 0.65 mg/Kg [32].

Measured factors in mice

Body weight was measured weekly. Non-fasted mice were sacrificed after the experiment duration under anesthesia via inter peritoneal injection of Ketamine /xylazine(100/7.5 mg/Kg). and their blood were collected. The blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Blood sugar and triglyceride were measured by commercial kits(Pars Azmoon Co, Iran) by a photometric method.

Histological studies

The tissues from liver and visceral fat were removed and fixed in buffered formalin 10 %.After fixation tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin and cut with microtome.7µmtick sections affixed on to slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining and Sudan black-B kit.

Cell culture

3T3L1 cell line were obtained from Iranian Biological Resource Center (Tehran, Iran). Low Glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s ,medium (DMEM), Trypsin-EDTA 100 X, Fetal Bovine Serum ( FBS), Penicillin-Streptomycin (10000U/ml), DMSO were purchased from Zist Fanavari Kowsar (Tehran, Iran) and GIBCO (NY, USA). Inducer agents, Dexamethasone, Human Insulin and Isobutylmethylxantine (IBMX), Oil red O, formaldehyde and isopropanol were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, USA).

3T3L1 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10 % FBS until confluence (80 %). Four days after confluence (Day 0), the cells were counted and 8 × 104 cells were seeded to every well in a 6 well plate. Next day (Day 1) cells were stimulated to differentiate in induction medium (IM) with DMEM containing 10 % FBS, 1 % antibiotics, insulin 1 mg/ml, dexamethasone, IBMX and hydro-alcoholic extract of green tea in different concentrations (50,100,150,200 µg/ml) Preadipocytes with induction media were used without green tea as a control and with normal cell culture media as blank for 10 days.

Oil‐red O staining and triglyceride assay

Cells were washed with Phosphate-buffered saline(PBS) and fixed with formaldehyde 10 % for 30 min. Then cells were stained with filtered Oil-red O solution(60 % isopropanol,40 %water) for 45 min in incubator at 37 °C. Additional stain was removed and the plates were rinsed with water and dried. The stained cells were photographed at a magnification of ×20 and x40 using an Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope system (Tokyo, Japan). After the Oil red O retained in the cells was extracted with isopropanol, absorbance was determined spectrophotometrically at 520 nm as described by Kim and Carvajal-Aldaz [33, 34].

Statistical analysis

The results were evaluated by one way (ANOVA) test(SPSS), and the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Body weight

At the end of the 8th week, body weight of the(TC) group decreased significantly compared with the(C) group (p < 0.001).This factor had increased significantly in the (O) group compared to the (C) group (p < 0.001), while in the (TO) group, the body weight had decreased significantly compared to (O) group although still higher compared to the (TC) group (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01 respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison with Control (*), with Treated control (#), and with Obese group (@)

| Groups | Weight (gr) | Glucose levels (mg/dl) | Triglycerides Levels (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 31.19 ± 0.66 | 120.83 ± 15.47 | 119.50 ± 11.74 |

| Treated Control | 27.54 ± 0.47 *** | 111.33 ± 10.47 | 90.33 ± 13.49 |

| Obese | 33.29 ± 0.45 *** | 116.50 ± 5.64 | 144.67 ± 17.97 * |

| Treated Obese | 29.96 ± 0.68 ##, @@@ | 115.17 ± 3.72 | 122.67 ± 9.14 |

***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, @@@p < 0.001

Biochemical factors

Unfasted blood glucose showed differences between various groups which were not significant (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Triglycerides levels of the (O) group were significantly higher than the (C) group (p < 0.05), while these had decreased in the treated groups, although not significantly (Table 1).

Histological studies

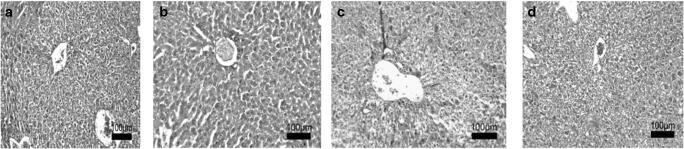

Upon H&E staining, C and TC groups hepatocytes showed natural morphology, where radial cords and canalicules were in the best status in TC ; in (O), hepatocytes exhibited very high necrosis compared to other groups (intact/degenerated hepatocytes ratio : 2/25), in )TO), hepatocytes cords were irregular and some polymorphonuclear cells were also observed, but were generally in better condition compared to (O) (Fig. 1a-d).

Fig. 1.

Liver tissue of different groups stained with Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E).Magnification × 10. a Control, b Treated Control, c Obese, d Treated Obese

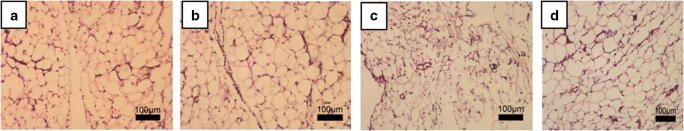

Comparison of adipocytes size showed that in (C), adipocyte diameter was approximately 50µ, 30–35 µ in (TC), higher than 60 µ in (O), and 60 µ in (TO) (Fig. 2a-d).

Fig. 2.

Visceral tissue in different groups stained with Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E). Magnification × 10. a Control, b Treated Control, c Obese, d Treated Obese

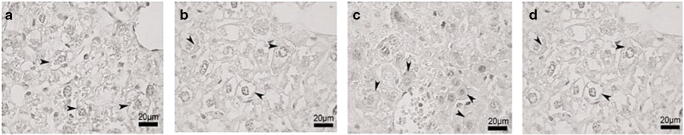

Upon staining with Sudan black, it was observed that treated obese mice hepatocytes manifested similar morphology with the control group, with regard to accumulation of lipid droplets under cell membrane. On the other hand, large amount of lipid droplets were deposited in obese group hepatocytes in approximately all cytoplasm spaces (Fig. 3a-d).

Fig. 3.

Liver tissue in different groups stained with Sudan black B. Magnification× 40. a Control, b Treated Control, c Obese, d Treated Obese

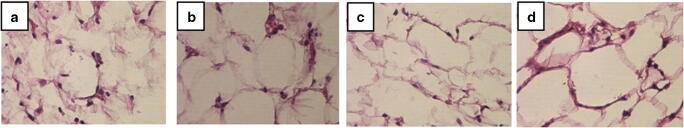

With regard to visceral fat, treated obese mice adipocytes showed similar morphology with control and treated control groups while in the obese group adipocytes large amount of lipid droplets were observed (Fig. 4a-d).

Fig. 4.

Visceral fat tissue in different groups stained with Sudan black B. Magnification× 40. a Control, b Treated Control, c Obese, d Treated Obese

GT effect on in vitro adipogenesis

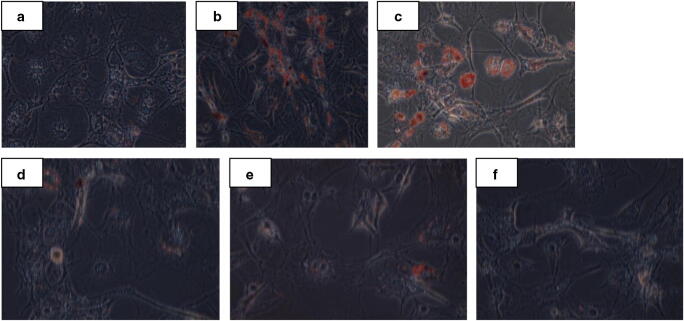

To investigate the anti- adipogenic effects of the (GT ) on conversion of preadipocytes to adipocytes, 3T3L1 cell line (as immature adipocytes) were differentiated with DMI media (0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine,0.25 µM dexamethasone, and 1 mg insulin) and different dosage of (GT ) for 10 days. Lipid deposition as a key marker of adipogenesis was quantified by Oil- red O staining ( lipophilic stain). The staining results indicated that (GT ) treatment in different dosage inhibited 3T3L1 adipocyte differentiation in a dose-dependent manner specially in high dosage(200 µg/ml) compared with lower concentrations (Fig. 5a-f).

Fig. 5.

The Effect of different doses of GT on 3T3L1 stained with Oil-red-O. Magnification× 40. a Cell culture medium; b Induction medium with out GT; c GT concentration 50 µg/ml; d GT concentration 100 µg/ml; e GT concentration 150 µg/ml; f GT concentration 200 µg/ml

Discussion

Green tea components are suggested to have generally positive effects on health [18]. The supposed weight lowering effect of green tea has been extensively studied but the results obtained from different reports are sometimes controversial.

We based our investigation on two points; an approximate simulation of low doses of daily green tea consumption and a mice model of obesity. It should be considered that with regard to differences in mice metabolism, it is usual to use an adjustment which diminishes the dose used in rodent up to several folds [32]. To our knowledge, our study is particular in the way it investigates the effect of a minimum dosage of GT on visceral fat tissue with such a histological focus.

We observed a significant effect of the extract on weight loss, and interestingly, a marked effect on the normal diet mice which received GT. Erba et al. have studied the effect of drinking two cups of GT (approximately 250 mg catechins) compared to a controlled diet group that did not consume GT. Their results showed that green tea consumption has a positive influence on body weight control [35]. In a study by Bajerska et al.,administration of 1.1 and 2 % GT aqueous extract resulted into improved body weight and visceral fat content in rats during eight weeks in a dose-dependent manner [31]. Diepvens et al. have investigated metabolic effects of GT and the phases of weight loss, and found that in a 12-weeks green tea consumption with a low energy diet, GT itself had no effect on body weight or body composition [36]. Auvichayapat et al.. studied the efficacy of green tea on weight reduction on obese Thais during 12 weeks, which showed that green tea induced body weight reduction [37]. Westerterp-Plantenga has emphasized the effectiveness of green tea components on body weight regulation, suggesting consumption of GT and caffeine together, which would result into thermogenesis [38]. The anti-obesity property of GT may actually be due to its capacity in increasing thermogenesis and fat oxidation and lower lipid peroxidation. GT suppresses appetite and nutrient absorption via inhibition of gastric and pancreatic lipases [31]. The catechin content of GT may also inhibit the activity of catechol-o-methyl-transferase(COMT)resulting in a longer duration of activity for catecholamines. On the other hand, caffeine which is another component of green tea, inhibits phosphodisterase which induces disruption of intracellular cyclic AMP(cAMP) resulting into increase of norepinephrine release and increase of cellular concentration of cAMP. Cyclic AMP is a major intracellular mediator for the catecholamines action on thermogenesis. Catecholamines play an important role in satiety in the brain and could thus be involved in green tea mechanism of weight loss [37, 38]. Bun et al. have studied the effect of a herbal medicinal product containing a GT, on liver function in Wistar rats. This study was conducted in order to test the hypothesis concerning the existence of hepatotoxins in green tea, but did not reveal any significant increase of hepatic functional parameters in any of treated group, however, bilirubin levels were decreased significantly (p < 0.05) [39].

Skrzydlewskaet al. study on the protective effect of green tea on liver lipid peroxidation, blood serum and the brain in rats has confirmed that traditional consumption of green tea could be effective against lipid peroxidation in these organs [40].

In our study, blood sugar levels of obese mice were not affected upon receiving the high-fat diet, while the triglycerides serum levels were increased, which is the characteristic of this model of initial stage of obesity. Upon treatment with GT, a lowering of triglyceride levels occurred in both normal and obese groups relative to their control untreated group (p > 0.05). The fact that some parameters changes were not significant may be due to the limited time of exposure (two months) or dosage of green tea (which was chosen to be minimal). Erba et al. mention that conflicting results are reported with regard to catechin effect on lipid plasma levels, as no significant effects were seen on plasma lipids upon six cups/day intake of green tea for four weeks [35]. In a study by Alessio et al., green tea consumption had no influence on TG and glucose levels in male rats after 6.5 weeks [41]. In an investigation that was done on GT consumption in healthy workers in Japan, Tokunaga et al.. reported that serum triglycerides differences were not statistically significant between various groups [42]. On the other hand, Hsu et al.. examined the effect of GT extract consumption on obese population for 12 weeks which resulted in significant reduction in triglyceride levels [43]. Wang et al. suggested that the inhibitory influence of green tea catechins on lipid absorption could be attributed to their interference with the micellar solubilization of lipids and inhibition of luminal lipolysis by pancreatic lipase [44].

In this study, we observed positive effect of green tea on liver tissue, especially in TC group which were fed by rodent standard pellet. Interestingly, a related protective effect of GT has been observed: Elhalwagy et al.. have reported that green tea (60 mg/animal/day) consumption in albino rats for 28 days could palliate the toxic effects of fenitrothion organophosphate insecticide in liver and kidney [45]. In the same line of studies, Kobayashi et al. have investigated the beneficial antioxidant effect of catechin on liver damage and have concluded that green tea catechin may even reduce hepatic fibrosis via suppressing oxidative stress and controlling the transcription factor involved in stellate cell activation [46]. An earlier study has also demonstrated a hepatoprotective effect of green tea in male rats that had been treated with 2-nitropane(2NP) for two weeks [47].

Liver and visceral fat tissues in TC and TO groups indicated better morphologic state than obese groups (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) which confirms the positive effect of green tea which is rich in various poly phenols, that show free radical scavenging and antioxidant properties and affect lipid oxidation [48].

Our in vitro results indicate that (GT ) decreased triglyceride droplets formation in a dose- dependent manner (Fig. 5). Other studies have been done on 3T3L1 cell line, for evaluation of different herbals extracts effects on lipogenesis, which have been associated with in vivo experiments, and showed a macro effect too. As examples, water soluble -extract of the edible brown algae petalonia binghamiae inhibits preadipocyte differentiation in a dose-dependent manner [49], and coptis chinesis ( which is used in china traditional medicine with anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive effects) exerts anti-adipogenic activity on 3T3L1 cell line [50]. SH21B, an anti-obesity mixture of seven herbs used in traditional Korean medicine inhibits also fat accumulation in 3T3L1 adipocytes, and affects key transcriptional factors of the adipogenesis pathway [51]. Clerodendron glandulosum leaf extract which is used by people in North East India to relieve signs of diabetes, obesity and hypertension, decreases adipogenesis and triglyceride aggregation on 3T3L1 preadipocytes via down regulation of PPARλ2- related genes and Lep expression [52].

Kim et al. have investigated effects of Atroctylods macrocephala Koidzumi rhizome on 3T3L1 cell line and found an inhibitory effect on adipogenesis through reduction of adipogenic factor phosphor-Akt [53]. Cho et al.. have studied the anti-obesity property of Schisandra chinesis ( Sc)in 3T3L1 cells. Sc impaired the conversion of preadipocytes to adipocytes in a dose –dependent manner by decreasing expression of the major adipocyte differentiation regulator C/EBPβ as well as C/EBPα or PPARλ and down regulation of the terminal marker gene aP2 during differentiation process [54]. Yellow capsicum extract has inhibited proliferation and differentiation of 3T3L1 preadipocytes and aggregation of triglyceride in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, this extract decreased expression of leptin, lipoprotein lipase (LPL), PPARλ and C/EBPα significantly as Zhang et al..(2014) have reported [55].

Overall, suppression of lipid accumulation in 3T3L1 cell line has been related to down-regulation of adipogenic genes such as PPARλ for Scoparone and terpenoid containing Ulmus pumila L. (UP), containing different triterpenoids [56, 57]and PPARλ, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ and adipocyte- specific gene such as aP2 for blueberry peel extract [58].

Our results indicated that (GT ) affected triglycerides formation droplets in a dose-dependent manner on 3T3L1 cell line, which could be related on similar mechanisms as mentioned above. In particular, caffeine has been shown to affect preadipocytes via (C/EBP)α and PPAR)γ inhibition [59].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the positive effect of GT on counteracting the consequences of high fat diet consumption, at serum, tissue, and cell level. The appreciable effect of GT on normal mice is also of interest and could be translated into suggestion of green tea consumption in a healthy diet, provided that further studies results concur with the present one.

Acknowledgements

National Elite’s Foundation has supported this study by Allameh-Tabatabaei grant. This study has also been supported by Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute (EMRI) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

This is a report of a post-doctoral project of FB under supervision of BL and advisory role of AE-H. FB has gathered the data, made data analysis and wrote first draft. MSA role was in GT extraction and in vitro section, MMA and SS in cell culture section, and RK in the in vivo section.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare to have no conflict of Interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Azadeh Ebrahim-Habibi, Email: aehabibi@sina.tums.ac.ir, Email: azadehabibi@yahoo.fr.

Bagher Larijani, Email: emrc@tums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Van der Ploeg LH. Obesity: an epidemic in need of therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4(4):452–60. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen C-S, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes. 2008;32(9):1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey R, Kumar N, Paroha S, Prasad R, Yadav M, Jain S, et al. Impact of obesity and diabetes on arthritis: An update. Health. 2013;5(1):143. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.51019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malekzadeh R, Mohamadnejad M, Merat S, Pourshams A, Etemadi A. Obesity pandemic: an Iranian perspective. Arch Iran Med. 2005;8(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutten GM, Meis JJ, Hendriks MR, Hamers FJ, Veenhof C, Kremers SP. The contribution of lifestyle coaching of overweight patients in primary care to more autonomous motivation for physical activity and healthy dietary behaviour: results of a longitudinal study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berendsen BA, Kremers SP, Savelberg HH, Schaper NC, Hendriks MR. The implementation and sustainability of a combined lifestyle intervention in primary care: mixed method process evaluation. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onakpoya IJ, Heneghan CJ, Aronson JK. Post-marketing withdrawal of anti-obesity medicinal products because of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun JW. Possible anti-obesity therapeutics from nature–A review. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(14–15):1625–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo S, Lenon GB, Gill H, Yuen H, Yang AW, Hung A, et al. Do the natural chemical compounds interact with the same targets of current pharmacotherapy for weight management?-A review. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(4):399–411. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666180830125958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moseti D, Regassa A, Kim W-K. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis and potential anti-adipogenic bioactive molecules. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(1):124. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Liu G, Guo J, Su Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(11):1483. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.27173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lass A, Zimmermann R, Oberer M, Zechner R. Lipolysis–a highly regulated multi-enzyme complex mediates the catabolism of cellular fat stores. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50(1):14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Kratky D, Riederer M, Knipping G, et al. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice changes the plasma lipid profile by affecting the tissue-specific expression pattern of lipoprotein lipase in adipose tissue and muscle. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(15):12946–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bastos DH, Saldanha LA, Catharino RR, Sawaya A, Cunha IB, Carvalho PO, et al. Phenolic antioxidants identified by ESI-MS from yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) and green tea (Camelia sinensis) extracts. Molecules. 2007;12(3):423–32. doi: 10.3390/12030423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoshraftar Z, Shamel A, Safekordi A, Zaefizadeh M. Chemical composition of an insecticidal hydroalcoholic extract from tea leaves against green peach aphid. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2019;16(11):7583–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad M, Baba WN, Gani A, Wani TA, Gani A, Masoodi F. Effect of extraction time on antioxidants and bioactive volatile components of green tea (Camellia sinensis), using GC/MS. Cogent Food Agric. 2015;1(1):1106387. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaveri NT. Green tea and its polyphenolic catechins: medicinal uses in cancer and noncancer applications. Life Sci. 2006;78(18):2073–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan N, Mukhtar H. Tea and health: studies in humans. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(34):6141–7. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319340008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasani-Ranjbar S, Jouyandeh Z, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of anti-obesity medicinal plants-an update. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013;12(1):28. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y, Shi D, Su B, Wei J, Găman MA, Sedanur Macit M, et al. The effect of green tea supplementation on obesity: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2020;34(10):2459–2470 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gulua L, Nikolaishvili L, Jgenti M, Turmanidze T, Dzneladze G. Polyphenol content, anti-lipase and antioxidant activity of teas made in Georgia. Ann Agric Sci. 2018;16(3):357–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinreb O, Mandel S, Amit T, Youdim MB. Neurological mechanisms of green tea polyphenols in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15(9):506–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong JT, Ryu SR, Kim HJ, Lee JK, Lee SH, Yun YP, et al. Protective effect of green tea extract on ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury in Mongolian gerbils. Brain Res. 2001;888(1):11–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haidari F, Omidian K, Rafiei H, Zarei M, Shahi MM. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) supplementation to diabetic rats improves serum and hepatic oxidative stress markers. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(1):109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutter S, Fraser O, Zito S-R, et al. Green tea extract suppresses the age-related increase in collagen crosslinking and fluorescent products in C57BL/6 mice. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2003;73(6):453–60. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.6.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu Y-W, Tsai C-F, Chen W-K, Huang C-F, Yen C-C. A subacute toxicity evaluation of green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(10):2624–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D, Meng J, Xu K, Xiao R, Xu M, Liu Y, et al. Evaluation of oral subchronic toxicity of Pu-erh green tea (camellia sinensis var. assamica) extract in Sprague Dawley rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;142(3):836–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takami S, Imai T, Hasumura M, Cho Y-M, Onose J, Hirose M. Evaluation of toxicity of green tea catechins with 90-day dietary administration to F344 rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(6):2224–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt M, Schmitz H-J, Baumgart A, Guedon D, Netsch M, Kreuter M-H, et al. Toxicity of green tea extracts and their constituents in rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43(2):307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banakar F, Parivar K, Yaghmaei P, Mohseni-Kouchesfehani H. Comparison of body weight gain and loss between male and female NMRI mice on a high fat-diet and treated by Orlistat. HealthMed.J7. 2013;1610–1617.

- 31.Bajerska J, Wozniewicz M, Jeszka J, Drzymala-Czyz S, Walkowiak J. Green tea aqueous extract reduces visceral fat and decreases protein availability in rats fed with a high-fat diet. Nutr Res. 2011;31(2):157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008;22(3):659–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim YS, Lee YM, Kim H, Kim J, Jang DS, Kim JH, et al. Anti-obesity effect of Morus bombycis root extract: anti-lipase activity and lipolytic effect. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130(3):621–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvajal-Aldaz DG. Inhibition of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cell line by quercetin or isorhamnetin. 2012.LSU Master's Theses. 4267

- 35.Erba D, Riso P, Bordoni A, Foti P, Biagi PL, Testolin G. Effectiveness of moderate green tea consumption on antioxidative status and plasma lipid profile in humans. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16(3):144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diepvens K, Kovacs E, Vogels N, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Metabolic effects of green tea and of phases of weight loss. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(1):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auvichayapat P, Prapochanung M, Tunkamnerdthai O, Sripanidkulchai B-o, Auvichayapat N, Thinkhamrop B, et al. Effectiveness of green tea on weight reduction in obese Thais: A randomized, controlled trial. Physiol Behav. 2008;93(3):486–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westerterp-Plantenga M. Green tea catechins, caffeine and body-weight regulation. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(1):42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bun S, Bun H, Guedon D, Rosier C, Ollivier E. Effect of green tea extracts on liver functions in Wistar rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44(7):1108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skrzydlewska E, Ostrowska J, Farbiszewski R, Michalak K. Protective effect of green tea against lipid peroxidation in the rat liver, blood serum and the brain. Phytomedicine. 2002;9(3):232. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alessio HM, Hagerman AE, Romanello M, Carando S, Threlkeld MS, Rogers J, et al. Consumption of green tea protects rats from exercise-induced oxidative stress in kidney and liver. Nutr Res. 2002;22(10):1177–88. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokunaga S, White IR, Frost C, Tanaka K, Kono S, Tokudome S, et al. Green tea consumption and serum lipids and lipoproteins in a population of healthy workers in Japan. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(3):157–65. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu C-H, Tsai T-H, Kao Y-H, Hwang K-C, Tseng T-Y, Chou P. Effect of green tea extract on obese women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(3):363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Noh SK, Koo SI. Green tea catechins inhibit pancreatic phospholipase A2 and intestinal absorption of lipids in ovariectomized rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17(7):492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elhalwagy ME, Darwish NS, Zaher EM. Prophylactic effect of green tea polyphenols against liver and kidney injury induced by fenitrothion insecticide. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2008;91(2):81–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi H, Tanaka Y, Asagiri K, Asakawa T, Tanikawa K, Kage M, et al. The antioxidant effect of green tea catechin ameliorates experimental liver injury. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(3–4):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sai K, Kai S, Umemura T, Tanimura A, Hasegawa R, Inoue T, et al. Protective effects of green tea on hepatotoxicity, oxidative DNA damage and cell proliferation in the rat liver induced by repeated oral administration of 2-nitropropane. Food Chem Toxicol. 1998;36(12):1043–51. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(98)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng Q, Yu X, Xu J, Wang L, Huang F, Huang Q, et al. Effects of endogenous and exogenous micronutrients in rapeseed oils on the antioxidant status and lipid profile in high-fat fed rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang S-I, Kim M-H, Shin H-S, Kim H-M, Hong Y-S, Park J-G, et al. A water-soluble extract of Petalonia binghamiae inhibits the expression of adipogenic regulators in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and reduces adiposity and weight gain in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21(12):1251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi JS, Kim J-H, Ali MY, Min B-S, Kim G-D, Jung HA. Coptis chinensis alkaloids exert anti-adipogenic activity on 3T3-L1 adipocytes by downregulating C/EBP-α and PPAR-γ. Fitoterapia. 2014;98:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H, Kang R, Yoon Y. SH21B, an anti-obesity herbal composition, inhibits fat accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and high fat diet-induced obese mice through the modulation of the adipogenesis pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127(3):709–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jadeja RN, Thounaojam MC, Ramani UV, Devkar RV, Ramachandran A. Anti-obesity potential of Clerodendron glandulosum. Coleb leaf aqueous extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135(2):338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim CK, Kim M, Oh SD, Lee S-M, Sun B, Choi GS, et al. Effects of Atractylodes macrocephala Koidzumi rhizome on 3T3-L1 adipogenesis and an animal model of obesity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park HJ, Cho J-Y, Kim MK, Koh P-O, Cho K-W, Kim CH, et al. Anti-obesity effect of Schisandra chinensis in 3T3-L1 cells and high fat diet-induced obese rats. Food Chem. 2012;134(1):227–34. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng Z, Hai-ning Y, Xiao-man C, Zun-chen W, Sheng-rong S, Das UN. Effect of yellow capsicum extract on proliferation and differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Nutrition. 2014;30(3):319–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noh J-R, Kim Y-H, Hwang JH, Gang G-T, Yeo S-H, Kim K-S, et al. Scoparone inhibits adipocyte differentiation through down-regulation of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Food Chem. 2013;141(2):723–30. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh C, Chung H-Y, Nandre RM, Lee JH, Jeon T-I, Kim I-S, et al. An active extract of Ulmus pumila inhibits adipogenesis through regulation of cell cycle progression in 3T3-L1 cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50(6):2009–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song Y, Park HJ, Kang SN, Jang S-H, Lee S-J, Ko Y-G, et al. Blueberry peel extracts inhibit adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells and reduce high-fat diet-induced obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim HJ, Yoon BK, Park H, Seok JW, Choi H, Yu JH, et al. Caffeine inhibits adipogenesis through modulation of mitotic clonal expansion and the AKT/GSK3 pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. BMB Rep. 2016;49(2):111. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]