Abstract

The field of implementation science has devoted increasing attention to optimizing the fit of evidence-based interventions to the organizational settings in which they are delivered. Institutionalization of health promotion into routine organizational operations is one way to achieve this. However, less is known about how to maximize fit and achieve institutionalization, particularly in settings outside of the healthcare system. This paper reports on findings from a parallel cluster-randomized trial that compared an organizationally tailored with a standard (core components only) approach for institutionalizing (“integrating”) an evidence-based cancer control intervention into African American churches. Churches randomized to the organizationally tailored condition identified three or more implementation strategies from a menu of 20, with an implementation time frame for each. The primary study outcome was assessed through the Faith-Based Organization Health Integration Inventory, a measure of institutionalization of health promotion activities in church settings, completed by pastors at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Seventeen churches were randomized and 14 were analyzed as 3 did not implement the study protocol. Though the percent increase in total integration score was greater in the tailored condition (N = 9; 18%) than in the standard condition (N = 5; 12%), linear mixed-effect models did not detect a statistically significant group × time interaction. Despite the challenges of integrating health promotion activities outside of healthcare organizations, the current approach shows promise for fostering sustainable health promotion in community settings and merits further study.

Keywords: Adaptation, Institutionalization, Implementation, Sustainability, Cancer, Organizational context

Implications.

Practice: Practitioners should leverage and expand organizational resources and structures for health promotion in faith-based settings, while finding ways to bolster the role of organizational communication.

Policy: Policymakers in faith-based organizations should formalize organizational resources, structures, processes, and communication to support sustainable health promotion activities.

Research: Future research is needed to further investigate the development and evaluation of organizationally tailored health promotion interventions to maximize intervention-setting fit, particularly when working in settings outside of the healthcare system.

The field of implementation science in recent years has increasingly recognized the importance of organizational factors in intervention implementation [1–5]. This focus has included the idea of maximizing the fit of interventions with organizational settings where they are implemented [6–9]. Though intervention adaptation has not historically been encouraged in the context of efficacy trials and was often discouraged as a threat to fidelity, there is now wider acceptance that interventions require adaptation to fit the host setting [6, 10, 11]. This shift in the zeitgeist is illustrated by the emergence of models providing guidance on how to adapt interventions for new settings or priority populations [11–19].

Common among adaptation models is the notion that an intervention’s core components should be identified to preserve fidelity in the face of adaptations [13–15]. The identification of core components as active ingredients should be guided by the behavior change theory underlying the intervention, which outlines the mechanism of its effect [13, 14, 16]. It is also recommended that adaptations should be guided by community engagement involving the priority population and/or key stakeholders [11, 12]. Much of this research focuses on healthcare organizational settings; however, sustainability may be at greater risk when interventions are delivered in community settings, particularly those limited in resources or those in which health promotion is not central to their mission.

One such community setting where health promotion often occurs is faith-based organizations or churches [20–22]. However, implementing and sustaining evidence-based health interventions in these settings has its own unique set of challenges [23, 24], primarily involving competing demands and limited resources. In a sample of Latino churches Allen and colleagues [25] reported that though the churches scored highly on a variety of organizational factors thought to facilitate health promotion, actual health promotion activities were limited. This suggests that further research is needed to understand predictors or facilitators of health promotion in these settings. A related study in Latino churches indicated that high organizational readiness and the presence of a health ministry were related to health promotion activities offered in the prior year [26]. Because there is considerable variation in organizational capacity for health promotion among faith-based organizations [5, 27–29], it is important that interventions delivered in these settings are adaptable and customizable to the host organization without compromising fidelity. Though there is little guidance on how to tailor implementation strategies to the delivery setting, methods such as concept mapping, group model building, conjoint analysis, and intervention mapping have been suggested [30]. Powell and colleagues [31] suggested that further research is needed to strengthen methods to tailor implementation strategies to context and to test the effectiveness of multi-faceted and tailored implementation strategies. Duong and colleagues [32] suggested that implementation strategies may need to be tailored to the evidence-based practice itself.

The current paper reports on findings from a cluster-randomized trial that compared a new organizationally tailored with a standard (core components only) approach for institutionalizing (“integrating” into the organization’s routine operations [33]) an evidence-based cancer control intervention into 14 African American churches in Maryland. A cluster-randomized design was appropriate as the research question and study outcomes are evaluated at the organizational level. The primary outcome was assessed through the Faith-Based Organization Health Integration Inventory [29], a measure of the extent to which churches institutionalized health promotion activities into their routine operations, completed by pastors at baseline and 12-month follow-up. It was hypothesized that integrated condition (IC) churches would report a significantly greater increase in institutionalization scores from baseline to follow-up than those randomized to the standard condition (SC). Because there is little research on intervention-organization fit outside of healthcare settings, study findings have implications for future behavioral translational and implementation science research and practice.

Methods

Project HEAL intervention

The intervention platform for this research is “Project HEAL” (Health through Early Awareness and Learning) [34–38]. The Project HEAL intervention aims to increase awareness and screening for breast, prostate (informed decision making for screening), and colorectal cancer. This theory-based, culturally targeted intervention is delivered by trained and certified lay peer community health advisors, through African American church settings. Details on the intervention are described elsewhere [39] though key points are covered here, guided by the TIDieR checklist. The intervention begins with a Health Ministry Guide, which serves as an introduction of Project HEAL to church leadership and provides general guidance on how to implement the intervention. The intervention is delivered by lay persons in the church who complete a 13-module training with core modules (e.g., cancer-specific content) delivered in-person and additional modules (e.g., research ethics, leadership) taken online [34]. After certification, the community health advisors deliver a series of three monthly cancer educational workshops in their churches (cancer overview, breast/prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer). The workshops are guided by a spiritually based PowerPoint slide deck and the community health advisors distribute project-specific print educational booklets to attendees. The Health Ministry Guide, community health advisor training modules, workshop materials (including the slide deck and cancer educational booklets), and cancer resource guide (listing of local screening providers) are considered the intervention core components. The Project HEAL workshops have been shown to result in significant increases in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer knowledge, as well as significant increases in reports of fecal occult blood test and colonoscopy, mammography maintenance among women, and digital rectal exams in men, over 24 months [35]. Building upon this work, the current study tested an approach to institutionalizing Project HEAL in a new set of churches through an organizationally tailored approach, previously described in detail [39].

Churches randomized to the organizationally tailored, hereafter referred to as the IC, implemented the intervention’s core components and additionally identified three or more implementation strategies from a menu of 20, with an implementation time frame for each. The IC as well as the current study’s evaluation approach were based on implementation science theory around institutionalization, primarily the work of Goodman and colleagues [9, 40], who developed the Level of Institutionalization Scales [40]. Though developed for use in healthcare systems, this approach emphasized aspects of institutionalization including niche saturation (e.g., integration of an evidence-based intervention into an organization’s subsystems), maintenance routine (e.g., dedicated staff), and supportive routine (e.g., established funding source), which we further tailored for use in church settings [29]. Churches randomized to the SC implemented the intervention’s core components only with no organizational tailoring.

The IC approach was implemented through the use of a customized, menu-based checklist as part of a church-specific memorandum of understanding [39]. IC churches delivered the core components and were additionally asked to implement a minimum of three additional health implementation strategies (e.g., form a health team, keep records of health activities, allocate budget for health activities) within timeframes (3, 6, 9, 12, or 24 months), both selected by the pastor. The IC included an additional training module to teach the community health advisors how to integrate health promotion activities into their churches’ routine activities. IC churches were allowed to train as many community health advisors as they wished, while SC churches trained one male and one female, consistent with the standard Project HEAL protocol.

Randomization

This study used a parallel cluster-randomized trial design with church cluster as the unit of analysis. After enrollment by the community partners, the study biostatistician independently randomized churches to the SC or IC condition using SAS syntax and matched pairs based on church membership size (smaller, larger) in which one church in each pair was assigned to each study group (1:1 ratio). The CONSORT checklist was used in the trial reporting.

Recruitment

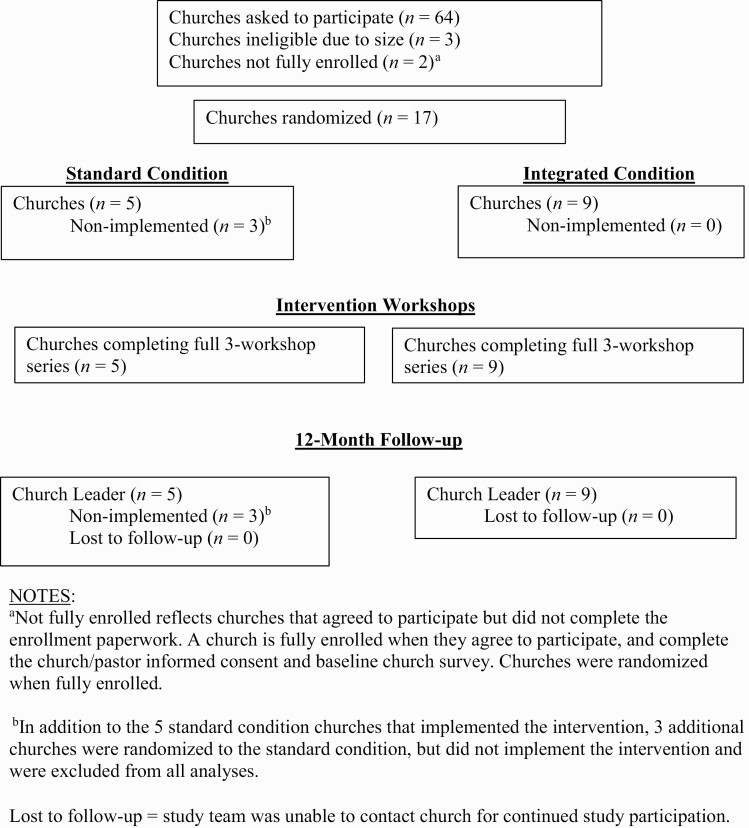

All study methods were approved by the University of Maryland, College Park Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent to participate. Recruitment occurred at three levels: church/pastor, community health advisor, and intervention workshop participant. Because the focus of the current analysis is on the primary study outcome of church-level integration of the intervention, workshop participant outcomes are not reported here. The efficacy of the Project HEAL intervention on workshop participant outcomes has been previously documented [35]. Church eligibility guidelines included that the church was a predominantly African American congregation, with between 150 and 900 weekly adult attendees, and the church had not hosted a similar health promotion or research activity in cancer control in the previous 5 years. Two community partners on the study team led the recruitment of 17 churches from Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and Prince George’s County, Maryland (see CONSORT flow diagram, Fig. 1). An uneven number of churches were randomized because one additional church was recruited. The number of churches was estimated by power analysis and sample size calculation based on the cluster-randomized design, using estimated effect size and a size of 40 per cluster. Churches received a $500 incentive for their time and participation.

Fig 1.

Project HEAL 2.0 CONSORT flow diagram. aNot fully enrolled reflects churches that agreed to participate but did not complete the enrollment paperwork. A church is fully enrolled when they agree to participate, and complete the church/pastor informed consent and baseline church survey. Churches were randomized when fully enrolled. bIn addition to the 5 standard condition churches that implemented the intervention, 3 additional churches were randomized to the standard condition, but did not implement the intervention and were excluded from all analyses. Lost to follow-up = study team was unable to contact church for continued study participation.

The pastor in each church identified individuals to serve as community health advisors. Community health advisor eligibility criteria included self-identification as African American, age 21 or older, regularly attending services at the host church, and willingness to complete the Project HEAL training and certification and implement the intervention. A total of 46 community health advisors were recruited, with IC churches training between 2 and 9 people, while SC churches each trained 2 people. Community health advisors received an incentive of $50 at the first of the 3-part workshop series and another $49 upon completion of the series.

Data collection and study measures

Data collection occurred from the period of 2017–2018 (baseline) to 2019–2020 (12-month follow-up) and the analyses were conducted in 2020. Upon enrollment, each pastor completed a self-administered church survey that contained descriptive information about each church [5] (e.g., membership size, number of staff) and the main study outcome measure of integration, described below. The community partner who recruited each church/pastor was responsible for collecting completed surveys at baseline and follow-up.

The integration measure, the Faith-Based Organization Health Integration Inventory (FBO-HII), was completed by pastors at baseline and 12-month follow-up. The FBO-HII was developed as a measure of institutionalization of health promotion practices designed for use in church settings [29]. The measure contains 22 items, with 4 subscales identified using exploratory factor analysis [29] (see Table 1). Items used a yes/no, count, or frequency format. Subscale scores were derived by summing the items, with a total score calculated as the sum of the subscales. The four subscales assessed organizational structures (e.g., health ministry, health team), organizational processes (e.g., records on health activities, instituted health policy), organizational resources (e.g., health promotion budget, space for health activities), and organizational communication (e.g., health content in church bulletins, discussion of health in pastor sermons) for health promotion. A previous psychometric examination revealed the measure had strong internal consistency reliability (α = .89), including for each subscale (α = .90, α = .82, α = .81, α = .87, respectively) [29].

Table 1 .

Implementation strategies selected by N = 9 integration condition churches

| FBO-HII subscale | Implementation strategy | # Churches that selected strategy for implementation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeframe (months) | ||||||

| Already doing | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | ||

| Organizational structures | a Church has an existing health ministry | – | – | – | – | – |

| Form a health team | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Form a health ministry | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| a Health activities are conducted under regional/national religious organization | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Organizational processes | Develop a written church health policy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Include health in church’s mission statement | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Host a health retreat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Volunteers working on health activities | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Paid staff working on health activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| b Dedicate one person to be in charge of health activities | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Keep records of health activities | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Organizational resources | Provide training for those working on health activities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Evaluate the quality of health activities | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Develop a health clinic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Allocate space for health activities | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Allocate budget for health activities | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Conduct fundraising for health activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Organizational communication | Hold organizational planning meetings for health activities | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| b Hold regular health meetings for church membership | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Include health content in Pastor sermons | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Include health content in church bulletins/newsletters | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Include health content in church social media posts | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

FBO-HII Faith Based Organization Health Integration Inventory.

aItem used in evaluation (FBO-HII) but not in the menu of implementation strategies.

bItem not used in evaluation (FBO-HII) but was included in menu of implementation strategies.

Statistical analyses

The comparison between FBO-HII scores by study group (e.g., IC vs. SC) from baseline to 12-month follow-up was assessed by linear mixed-effects models, where a random effect term was included to adjust for the within-church correlations among repeated measures. An interaction effect term between time and study group was used to assess the differences between IC and SC churches in the change of FBO-HII scores over time. The analysis is based on the 14 churches that implemented the intervention as 3 had dropped out before initiating the protocol.

Results

Table 2 shows demographic information for the churches overall and by study group. All analyses are based on the 9 IC and 5 SC churches that implemented the intervention. Churches had an average estimated size of 320 members attending weekly service (SD = 417), the pastors ranged in educational level with 8 of the 14 holding a Ph.D. or other doctoral degree, 85.7% of the churches owned their building, and the churches had an average of 3.6 paid staff (SD = 5.4). There were no statistically significant differences at baseline in any of the church characteristics.

Table 2 .

Church demographic information overall and by study group

| Overall (N = 14) | Integrated (N = 9) | Standard (N = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly service attendance (Mean, SD) | 321 (417) | 334 (446) | 296 (407) |

| Pastor outside employment N (% yes) | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Pastor education N (%) | |||

| Doctor of Ministry | 4 (28.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ph.D. | 4 (28.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Other | 4 (28.6%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Missing data | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Church owns its building N (% yes) | 12 (85.7%) | 8 (88.9%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Number of paid full-time staff (Mean, SD) | 3.6 (5.4) | 4.0 (6.3) | 2.8 (2.9) |

| Number of paid part-time staff (Mean, SD) | 9.3 (22.4) | 12.9 (27.4) | 2.3 (1.3) |

| Number of volunteers (Mean, SD) | 41.5 (37.3) | 37.4 (39.3) | 48.0 (37.2) |

Table 1 includes the menu of implementation strategies and their planned timelines for implementation. Notably, no churches planned to dedicate paid staff time for health promotion activities or to allocate budget for these activities if they were not already doing so. Forming a health clinic was only included in the churches’ longer-term plans.

Table 3 shows the mean values for the study outcomes at baseline and 12 months by study group, as well as the baseline to 12-month percent change in each study group. The IC churches had greater baseline levels of the outcomes, though this difference was only statistically significant for the organizational resources for health subscale, p < .01. Churches in both groups increased in most of the outcome subscales over the study period. The change in outcome means in the IC churches was greater, though not statistically, than in the SC churches. The outcome subscale that increased the most was organizational resources for health promotion.

Table 3 .

Means and standard deviations for study outcomes at baseline and follow-up by study group

| Integrated (N = 9) | Standard (N = 5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Baseline | 12 months | % Changea | Baseline | 12 months | % Changea |

| Organizational structures (e.g., health ministry, team)/5 max |

4.11 (2.03) |

4.89 (0.93) |

15.60 | 3.40 (1.34) |

3.40 (1.34) |

0.00 |

| Organizational processes (e.g., records, health policy)/9 max |

4.80 (2.59) |

6.11 (1.83) |

14.55 | 2.80 (1.10) |

4.60 (0.89) |

2.00 |

| Organizational resources (e.g., budget, space)/9 max |

4.25 (1.83) |

6.44 (1.24) |

24.33 | 1.25 (0.96) |

4.00 (1.58) |

30.55 |

| Organizational communication (e.g., health in church bulletins, sermons)/16 max |

8.38 (3.89) |

9.78 (2.33) |

8.75 | 6.80 (4.92) |

5.60 (2.30) |

−7.50 |

| Total integration score/39 max | 20.20 (9.34) |

27.22 (4.38) |

18.00 | 13.00 (6.58) |

17.60 (3.51) |

11.79 |

aPercent change is based on percent of scale possible score.

Table 4 shows the regression coefficient estimates of the fixed effects for the linear mixed-effects models to examine the study group comparison in the change in integration scores over the 12-month study period. The primary effect of interest is the group × time interaction. The study groups did not significantly differ in the change in any of the outcomes from baseline to 12 months. Churches in both study groups had a significant increase in organizational resources.

Table 4 .

Linear mixed-effects models of study group and change in outcomes baseline to 12 months

| Parameter | β | SE | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Organizational structures | |||

| Intercept | 3.40 | 0.67 | <0.001** |

| Study group | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.41 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| Study group × time | 0.78 | 1.19 | 0.52 |

| Model 2: Organizational processes | |||

| Intercept | 2.80 | 0.78 | 0.002** |

| Study group | 2.13 | 1.08 | 0.06 |

| Time | 1.80 | 0.84 | 0.06 |

| Study group × time | −0.62 | 1.15 | 0.60 |

| Model 3: Organizational resources | |||

| Intercept | 1.25 | 0.72 | 0.10 |

| Study group | 3.10 | 0.89 | 0.002** |

| Time | 2.75 | 0.73 | 0.003** |

| Study group × time | −0.65 | 0.90 | 0.48 |

| Model 4: Organizational communication | |||

| Intercept | 6.80 | 1.52 | <0.001** |

| Study group | 1.59 | 1.92 | 0.42 |

| Time | −1.20 | 1.54 | 0.45 |

| Study group × time | 2.59 | 1.95 | 0.21 |

| Model 5: Total integration | |||

| Intercept | 12.95 | 2.930 | <0.001** |

| Study group | 7.65 | 3.908 | 0.07 |

| Time | 4.65 | 3.317 | 0.19 |

| Study group × time | 1.97 | 4.363 | 0.66 |

*Effect is significant at p < .05.

**Effect is significant at p < .01.

P values are calculated using Wald tests.

Analysis conducted on the 14 churches that completed the intervention.

Time effect is based on the reference group (standard condition churches).

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of a novel intervention to foster sustainable health promotion activities in African American church settings, by integrating (i.e., institutionalizing) them into routine church operations through organizational structures, processes, resources, and communications. The current IC approach could be considered an adaptive intervention, where adaptation is not only permissible but actively encouraged based on an a priori set of modifications provided by the developers [41], where the implementation strategy(ies) can be tailored over time [42], optimally based on a community-engaged process. The contribution of the study is innovative particularly because most previous research on the concept of institutionalization of health promotion interventions has occurred in healthcare settings, as opposed to a community setting where the primary focus is not health promotion.

The baseline data indicated that pre-intervention scores were greatest for organizational structures relative to the other outcomes. This suggests that most of the enrolled churches already had some structural mechanism, such as a health ministry or team, for conducting health promotion activities. Though churches that were inclined to participate in the trial may be more likely to have such a precedent for health promotion than those that did not, having such structures would appear to bode well for the implementation of the intervention. This reflects Goodman and colleagues’ [40] concept of niche saturation, in which an intervention is integrated throughout an organization’s subsystems. Future research in these settings may consider further enumerating the church’s subsystems such as the various ministry groups (e.g., health, seniors, families) and evaluating the extent to which a health promotion intervention permeates or is implemented through those subsystems. This will require the health ministry volunteers to work in concert with other church ministry volunteers to implement health programming through these structures.

Theory on institutionalization also emphasizes the maintenance routine [40] concept, which includes but is not limited to having dedicated staff for implementation. Our study data indicate that none of the churches planned to dedicate paid staff time for health promotion activities. This reflects the limited resource nature of the setting, with few paid staff available to cover the church operations. Though valued, health promotion activities come at an opportunity cost in which a limited pool of often overcommitted volunteers must either expand their slate of activities or take attention away from ongoing activities to focus on health promotion. This is illustrative of one of the primary challenges in implementing and sustaining health promotion interventions in church settings.

The IC churches scored higher at baseline than the SC churches in all of the integration subscales, however, this difference was only statistically significant for organizational resources (e.g., health promotion budget, space for health activities). While it is possible that there was a limitation in the randomization of equalizing the two groups at the outset, baseline study group differences for either general church characteristics or the outcome variables in large part did not reach the threshold for statistical significance. The baseline group difference in resources was not due to church size, as the churches were randomized in pairs matched by size, an attribute thought to be most closely linked to such resources. The difference was also not driven by church physical location (e.g., Prince George’s County; Baltimore City), as preliminary analyses did not indicate a statistically significant, or even notable, mean difference at baseline (data not shown).

With regard to change in integration scores over time, most study outcomes exhibited increases from baseline to the 12-month follow-up. While the increase was only significant for organizational resources, some of these increases were substantial in magnitude. While the IC intervention was designed specifically to encourage the churches to apply the implementation strategies through a tailored memorandum of understanding, it appears the SC churches also implemented a number of these activities during the study period. The increases in SC churches were not likely due to contamination as there was no evidence of inter-organizational communication and there was a considerable geographic separation between many of the churches. The observed pattern could be due to a testing effect where pastors in both study groups were inclined to indicate greater activities at follow-up just by virtue of being involved in a health promotion intervention. Use of a no-treatment control group could have eliminated this potential bias, however, we do not consider collecting data without benefit to the community to be consistent with ethical research conduct [43], particularly in settings disproportionately impacted by health disparities. It is challenging to collect church organizational data when in most cases only one person, the pastor, is authorized or has the organizational knowledge to provide the information. Future studies should consider collecting implementation data from the implementers, in the current case the community health advisors based on their activities, but also from the intervention participants themselves. Another strategy would have been to collect implementation data through direct observation rather than self-report, though this would likely require a more resource-intensive approach.

Though not statistically significant, the magnitude of change over time in the overall integration score was greater in IC than in SC churches. The IC churches increased in total integration score by 18% while the SC churches increased by 12%, both of which appear to be a clinically meaningful increase in practice. Because the greater number of community health advisors in the IC churches could have driven this group difference, we ruled out this possibility through a secondary analysis that controlled for number of community health advisors. Though the cluster-randomized study design was appropriate to test the research question, there are limitations in statistical power with a total of 14 churches as the units of analysis, each with only one observation per time point. Having three churches drop out of the standard condition further attenuated statistical power though there is no reason to expect a systematic reason for their dropping out. The limitation in number of clusters is driven by the feasibility recruitment in that it often takes several months to build relationships with individual churches resulting in enrollment in the study, as evidenced by our lengthy church recruitment period. Future research in this area may benefit from the application of alternative research designs (e.g., dynamic wait list design, interrupted time series design) that maximize efficiency of small samples where the intervention is implemented at the organizational or group level [43, 44].

Strengths and limitations

The current study had many strengths, primarily with the innovative, prospective, organizationally tailored method for maximizing intervention-organization fit and fostering the integration of health promotion activities in church settings. In an extension of the RE-AIM Framework aiming to increase sustainability and promote health equity, Shelton and colleagues [45] proposed that to achieve greater sustainability and an impact on health inequities, settings should preserve core components of an evidence-based intervention but also include proactive, planned, and iterative adaptations to the implementation strategies that fit with the context. It has been reported that adaptations made systematically and proactively, consistent with the intervention’s core functions, and implemented to increase fit are more likely than those that are not, to have a positive impact on the intervention outcomes [46]. Future research could consider an approach in which the selection of the implementation strategies is co-created using a process in which the investigative team helps identify appropriate strategies in consultation with the church leadership, based on a discussion or mapping of existing resources, capacities, and infrastructure. Providing this technical assistance to churches in the selection of implementation strategies may help them identify those that are most likely to be not only feasible but impactful.

As previously discussed, our study limitations involved primarily the number of church clusters that could be enrolled due to the intensity of community engagement, and an unexplainable differential dropout in the standard condition which attenuated our realized statistical power. This limited the ability of our analytic approach to identify statistical significance, even in the face of clinically meaningful change in study outcomes over time particularly in the IC churches. Because the study compared an already high quality, church-targeted intervention with the new organizationally tailored approach, this made it difficult for study group differences to manifest in the outcomes. Finally, findings may not generalize beyond the participating churches.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that the churches were in large part able to integrate health promotion into a number of their existing organizational operations over 12 months. The findings around meaningful increases in integrated health promotion activities over time are perhaps more impressive given that the church’s primary mission is not health promotion and many of these settings have limited resources. Implications for future research merit further development and evaluation of organizationally tailored health promotion interventions to maximize intervention-setting fit, especially in settings outside of the healthcare system. Implications for public health practice reinforce the idea that practitioners should encourage intervention adaptation to the settings in which the interventions are delivered, while retaining core effective components. Specifically, future research and practice may consider leveraging and expanding organizational resources for health promotion, while finding ways to bolster missed opportunities in organizational communication’s role in health promotion. By implementing evidence-based and sustainable health promotion interventions in community-based settings, we can have population-level impact on the health disparities that continue to plague medically underserved and other under-resourced communities, including those of color.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to acknowledge the work of Dr. Mary Ann Scheirer and Rev. Alma Savoy for their contributions to the development of the HEAL 2.0 intervention. This work was supported by the American Cancer Society under Grant RSG1602201CPPB, and by funds through the Maryland Department of Health’s Cigarette Restitution Fund Program. Dr. Knott, Mr. Woodard, and Ms. Okwara are supported by the National Cancer Institute—Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG)—P30CA134274.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Human rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any

of the authors.

Transparency Statements

Study registration: The study was pre-registered at clinicaltrials.gov (registered 06/05/17). Identifier: NCT03178383. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03178383.

Analytic plan pre-registration: The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data availability: De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author, following an executed data use agreement.

Analytic code availability: Analytic code used to conduct the analyses presented in this study are not available in a public archive. They may be available by emailing the corresponding author.

Materials availability: All materials used to conduct the study are available through a request to the corresponding author. Intervention materials are available at https://sph.umd.edu/department/bch/lab/43501.

References

- 1. Locke J, Lawson GM, Beidas RS, et al. Individual and organizational factors that affect implementation of evidence-based practices for children with autism in public schools: a cross-sectional observational study. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Farahnak LR. Assessing the organizational context for EBP implementation: the development and validity testing of the Implementation Climate Scale (ICS). Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Chavarin CV, et al. Implementation of an efficacious intervention for high risk women in Mexico: protocol for a multi-site randomized trial with a parallel study of organizational factors. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, Santos SLZ, et al. Assessing capacity of faith-based organizations for health promotion activities. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(5):714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval. 2005;26(3):320–347. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Estabrooks PA, Smith-Ray RL, Dzewaltowski DA, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based community-based physical activity programs for older adults: lessons from Active for Life. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(2):208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goodman RM, Steckler A. A model for the institutionalization of health promotion programs. Fam Community Health. 1989;11(4): 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen EK, Reid MC, Parker SJ, Pillemer K. Tailoring evidence-based interventions for new populations: a method for program adaptation through community engagement. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(1): 73–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Udelson H, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2018;9(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Backer TE. Finding the Balance: Program Fidelity and Adaptation in Substance Abuse Prevention: A State-of-the-Art Review. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bartholomew Eldredge L, Highfield L, Hartman M, Mullen P, Leerlooijer J, Fernandez M. Using intervention mapping to adapt evidence-based interventions. In: Bartholomew Eldredge L, Markham C, Ruiter R, Fernandez M, Kok G, Parcel G, eds. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention m Apping Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2016:597–649. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Card JJ, Solomon J, Cunningham SD. How to adapt effective programs for use in new contexts. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SJ, Altschul I, Mowbray CT. Using planned adaptation to implement evidence-based programs with new populations. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):290–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, et al. ; ADAPT Team . Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 suppl A):59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Cancer Institute. Guidelines for Choosing and Adapting Programs (Research-Tested Intervention Programs); 2017. Retrieved from http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/reference/adaptation_guidelines.pdf.

- 19. Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV Interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(suppl 1):S40–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28(1):213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slade JL, Holt CL, Bowie J, et al. Recruitment of African American churches to participate in cancer early detection interventions: a community perspective. J Relig Health. 2018;57(2):751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis DT, Bustamante A, Brown CP, et al. The urban church and cancer control: a source of social influence in minority communities. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(4):500–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graham-Phillips AG, Holt CL, Mullins CD, Slade JL, Savoy A, Carter R. Health ministry and activities in African American faith-based organizations: a qualitative examination of facilitators, barriers, and use of technology. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holt CL, Chambers DA. Opportunities and challenges in conducting community-engaged dissemination/implementation research. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):389–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center Facts. Vol. 800-888-8823. Baltimore, Maryland: University of Maryland Medical Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen JD, Torres MI, Tom LS, et al. Enhancing organizational capacity to provide cancer control programs among Latino churches: design and baseline findings of the CRUZA Study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holt CL, Shelton RC, Allen JD, et al. Development of tailored feedback reports on organizational capacity for health promotion in African American churches. Eval Program Plann. 2018;70:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leyva B, Allen JD, Ospino H, et al. Enhancing capacity among faith-based organizations to implement evidence-based cancer control programs: a community-engaged approach. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams RM, Zhang J, Woodard N, Slade J, Santos SLZ, Knott CL. Development and validation of an instrument to assess institutionalization of health promotion in faith-based organizations. Eval Program Plann. 2020;79:101781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duong MT, Cook CR, Lee K, Davis CJ, Vázquez-Colón CA, Lyon AR. User testing to drive the iterative development of a strategy to improve implementation of evidence-based practices in school mental health. Evid Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;5(4):414–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Developing the terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012:23–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holt CL, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, et al. Translating evidence-based interventions for implementation: Experiences from Project HEAL in African American churches. Implement Sci. 2014;9:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holt CL, Tagai EK, Santos SLZ, et al. Web-based versus in-person methods for training lay community health advisors to implement health promotion workshops: participant outcomes from a cluster-randomized trial. Transl Behav Med. 2018;9(4):573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santos SL, Tagai EK, Wang MQ, Scheirer MA, Slade JL, Holt CL. Feasibility of a web-based training system for peer community health advisors in cancer early detection among african americans. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2282–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santos SL, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, et al. Adoption, reach, and implementation of a cancer education intervention in African American churches. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scheirer MA, Santos SL, Tagai EK, et al. Dimensions of sustainability for a health communication intervention in African American churches: a multi-methods study. Implement Sci. 2017; 12(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Knott CL, Bowie J, Mullins CD, et al. An approach to adapting a community-based cancer control intervention to organizational context. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(2):168–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goodman RM, McLeroy KR, Steckler AB, Hoyle RH. Development of level of institutionalization scales for health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1993;20(2):161–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pérez D, Van der Stuyft P, Zabala MC, Castro M, Lefèvre P. A modified theoretical framework to assess implementation fidelity of adaptive public health interventions. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller CK. Adaptive intervention designs to promote behavioral change in adults: what is the evidence? Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(2):7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wyman PA, Henry D, Knoblauch S, Brown CH. Designs for testing group-based interventions with limited numbers of social units: the dynamic wait-listed and regression point displacement designs. Prev Sci. 2015;16(7):956–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fok CC, Henry D, Allen J. Research designs for intervention research with small samples II: stepped wedge and interrupted time-series designs. Prev Sci. 2015;16(7):967–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moore JE, Bumbarger BK, Cooper BR. Examining adaptations of evidence-based programs in natural contexts. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(3):147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]