Abstract

Objectives

Transparent reporting of trials is necessary to assess their internal and external validity. Currently, little is known about the quality of reporting in antibiotics trials. Our study investigates the reporting of adverse events, conflicts of interest and funding information in trials of penicillins, cephalosporins and macrolides.

Design

A secondary analysis of trials included in a convenience sample of three systematic reviews.

Methods

All randomised controlled trials included in the systematic reviews were included, although duplicates were removed. Eligible trials compared the specified antibiotics to placebo, for any indication. Author pairs independently extracted the data on reporting of adverse events from parent reviews, and data on funding and conflict of interest information from the trial reports. We calculated the overall proportion of trials reporting adverse events, conflict of interest information and funding information, and their proportion before and after the publication of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2001 Statement.

Results

We included 432 trials. Overall, 62% of trials reported adverse events of any kind, although reporting of deaths or antibiotic resistance was less frequent (20% and 37%, respectively). Conflict-of-interest information was provided in 26% of the trials, and funding information was provided in 66% of the trials. There was no significant difference in reporting of adverse events before and after the publication of CONSORT 2001 Statement (62% vs 62%, p=0.92). Conflict of interest statements were provided more frequently (2% vs 55%, p<0.001) and conflict was present more often (0% vs 14%, p<0.001). There was no difference in the provision of the information about trial funding before (62%) and after (70%) CONSORT 2001 publication.

Conclusions

Information about adverse events, conflict of interest and funding, remains under-reported in trials of antibiotics.

Keywords: adverse events, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We analysed the reporting of adverse events, conflicts of interests and funding information in published antibiotic trials, overall, and before and after publication of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2001 Statement.

The dataset consists of 432 randomised controlled trials of antibiotics, conducted across a period of 50 years, without language or publication restrictions.

Because the data set are limited to three classes of antibiotics (macrolides, cephalosporins and penicillins), the conclusions may not be generalisable to other classes of antibiotics.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard in evaluating the effectiveness of new healthcare interventions.1 2 However, RCTs have frequently been criticised for poor reporting of harms or adverse events.3 4 Concerns have also been raised about the inadequacy of reporting of conflicts of interests and funding information, as those may influence—or appear to influence—trial design, its conduct, reporting of results, their interpretation and conclusions,5–12 in turn jeopardising public trust.13

A clear and transparent reporting of studies is therefore needed to assess both their internal and external validity.14 To improve the quality of RCT reporting, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement was first published in 1996,15 with two revisions, in 200116 and in 2010,14 to reflect the evolving consensus on the importance of reporting of elements of RCTs.

The 1996 CONSORT Statement did not include items requiring the reporting of adverse events, funding or conflicts of interest.15 The 2001 update included an addition of an adverse events item on the reporting checklist, recommending that ‘all important adverse events or side effects in each intervention group’ be reported.16 Although neither funding nor conflict of interest (COI) information was not listed among the reporting items, information about sources of funding of the trial was identified in the article as highly desirable, and its inclusion in an RCT report was encouraged.16

Although several studies have assessed the quality of reporting funding resources and conflicts of interests,17–19 little is known about the quality of reporting of antibiotics trials. In this study, we, therefore, investigated the reporting in trials of three commonly used antibiotic classes: penicillins, cephalosporins and macrolides. We focused on the reporting of adverse events, conflicts of interests and funding information, both overall, and before and after the CONSORT 2001 Statement.

Methods

Data set

This is a secondary analysis of RCTs included in a convenience sample of three systematic reviews conducted by our research group. We choose these reviews as their main objective was to analyse the adverse events associated with the use of the most commonly used antibiotics. These systematic reviews included trials of penicillin, cephalosporin, or macrolides antibiotics, that compared each class alone against a placebo arm, for any indication (excluding trials with combined therapy).20–22 The cephalosporin review protocol was withdrawn as the review authors did not finish it during the expected time frame, along with some administrative issues just before publication. However, as three of this study authors were coauthors of the review, they retrieved all the RCTs included in this review (final search date was January 2019). Data were extracted from the review and the authors used it for this study (eg, reporting of adverse events and resistant data).

All RCTs included in the systematic reviews were eligible for this study, although duplicates (ie, the same RCT included in more than one systematic review) were excluded. The Participant, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome characteristics of the included systematic reviews and trials are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

PICO characteristics of the included systematic reviews and trials.

| Systematic review (SR) | Participants | Interventions*, †, ‡ | Comparator | Outcome |

| Penicillins20 | Individuals of all ages | Any penicillin class antibiotic | Placebo† | Any reported drug-related adverse event, death, resistant bacteria§ |

| Cephalosporins22 | Any cephalosporin class antibiotics | |||

| Macrolides21 | Any macrolide class antibiotics |

*Interventions delivered by any route, including oral, topical, intravenous and intramuscular.

†The use of concomitant medications was permitted if it was given for both arms.

‡Macrolides SR included trials with more than two intervention arms as long as one arm was a macrolide arm and one was a placebo arm.

§Same antibiotic-resistant bacteria for each review.

PICO, Participant, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome.

Procedure

Author pairs (KY, RN, AMS, MB and JB) independently extracted and entered data into a prepiloted data extraction form. All discrepancies were resolved by reference to a third author. Data on reporting of adverse events were extracted from the systematic reviews, which categorised adverse events as: reported, not reported or unclear. For the present analysis, we considered ‘unclear’ reporting of adverse events as not reporting.

Data on COI and funding statements were extracted directly from the trial reports. As defined per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), COIs included: current or former board membership, industry employment, consultancy work, grants (financial or in-kind), royalties, stock, travel reimbursement or other relations with relevant pharmaceutical companies.23 Funding statements included such information—whether financial or in kind (eg, supply of drug)—found in the article. Conventional funding statements (eg, ‘this study was funded by a grant from an XYZ organisation’) were included; statements about in-kind provision of pharmaceuticals for the trial by its manufacturer, for example, were also included.

Analysis

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) and descriptive statistics were calculated. We calculated the proportion of trials reporting or not reporting adverse events, which: (1) provided a COI statement; (2) identified a present COI; (3) provided a funding statement; (4) stated whether the trial was funded; (5) provided information on the source of trial funding and (6) identified the funder’s role in the trial.

We calculated the proportion of trials up to and including 2001 (the year of publication of CONSORT 2001), and the proportion of trials published from 2002, which reported: (1) any adverse events (other than deaths or antibiotic resistance); (2) deaths; (3) antibiotic resistance; (4) COI statement; (5) identified an existing COI among the trial authors and (6) provided information on the source of trial funding. We chose CONSORT 2001 rather than the ICMJE disclosure form publication in 2009 as the cut-point for the before and after analysis, as the former is specific to issues in reporting of RCTs, while the latter is study type independent.

The χ2 test was used to test for significant differences in reporting before and after CONSORT Statement.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor public were directly involved in the conduct or writing of this work.

Results

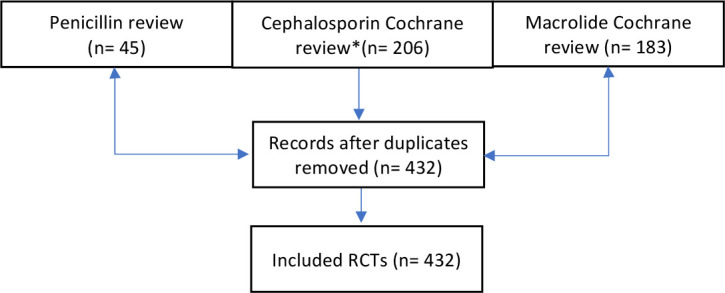

We included 432 RCTs after removing duplicates (figure 1). See online supplemental appendix 1 for the complete list of included trials.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included trials. *Cephalosporin Cochrane review is currently unpublished.

bmjopen-2020-045406supp001.pdf (416.7KB, pdf)

Summary of reporting characteristics

Overall, 62% of the 432 RCTs reported adverse events; reporting was less common specifically for deaths (20%) and antibiotic resistance (37%). COI statement was provided by 26% of all trials, and a COI was present in 7%. Funding information was provided in 66% of trials, and most commonly, the funding was provided by the industry (43%). Statement about the funder’s role in the trial was provided by nearly half (49%) of all trials (table 2).

Table 2.

Reporting of adverse events, COI and funding by the included RCTs (N=432)

| Any type of adverse event | All trials | ||||||

| Reported (n=334) | Not reported (n=98) | (n=432) | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Adverse events reporting | Drug-related adverse events reported (other than death / antibiotic resistance) | ||||||

| Yes | 266 | 80 | 266 | 62 | |||

| No* | 44 | 13 | 142 | 33 | |||

| Unclear | 24 | 7 | 24 | 5 | |||

| Deaths reported | |||||||

| Yes | 87 | 26 | 87 | 20 | |||

| No | 247 | 74 | 345 | 80 | |||

| Antibiotic-resistance reported | |||||||

| Yes | 158 | 47 | 158 | 36.6 | |||

| No | 173 | 52 | 271 | 62.7 | |||

| Unclear | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.70% | |||

| COI | COI statement provided? | ||||||

| Yes | 90 | 27 | 22 | 22 | 112 | 26 | |

| No | 244 | 73 | 76 | 78 | 320 | 74 | |

| COI present? | |||||||

| Present | 24 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 28 | 7 | |

| Absent | 66 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 84 | 19 | |

| Unclear (no COI statement provided) | 244 | 73 | 76 | 78 | 320 | 74 | |

| Funding | Funding statement provided? | ||||||

| Yes | 231 | 69 | 52 | 53 | 283 | 66 | |

| No | 103 | 31 | 46 | 47 | 149 | 34 | |

| Was the study funded? | |||||||

| Yes | 221 | 66 | 50 | 51 | 271 | 63 | |

| No | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 3 | |

| Unclear (no funding statement provided) | 103 | 31 | 46 | 47 | 149 | 34 | |

| Source of funding?†, ‡ | |||||||

| Industry | 100 | 45 | 17 | 34 | 117 | 43 | |

| Non-industry | 66 | 30 | 18 | 36 | 84 | 31 | |

| Both (industry and non-industry) | 54 | 25 | 15 | 30 | 69 | 26 | |

| Statement about the funder’s role provided?§ | |||||||

| Industry | |||||||

| Yes | |||||||

| No | 53 | 53 | 5 | 29 | 58 | 50 | |

| Non-industry | 47 | 47 | 12 | 71 | 59 | 50 | |

| Yes | |||||||

| No | 19 | 29 | 2 | 11 | 21 | 25 | |

| Both (industry and non-industry) | 47 | 71 | 16 | 89 | 63 | 75 | |

| Yes | 43 | 80 | 10 | 67 | 53 | 77 | |

| No | 11 | 20 | 5 | 33 | 16 | 33 | |

*Funding body involvement included, but not limited to, drug supply, laboratory services, study co-ordination and monitoring.

†The denominator here is for the number funded studies per each group.

‡The source of funding was not clear for one study

§The denominator here is for the total number of studies per each source of funding group.

COI, conflict of interest; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Among trials that did report any type of adverse events (n=344), 27% provided a COI statement and COI was present in 7%. Most trials provided a funding statement (69%), and 66% were funded—most frequently by the industry (45%). Just over half (52%) of the trials indicated the funder’s role in the trial (table 2).

Of the trials that did not report any type of adverse events (n=98), 22% provided a COI statement, and COI was present in 4% of the trials. Funding statement was provided by 53% of trials, and 51% of the trials were funded, most commonly by non-industry (36%). Thirty-four per cent of trials provided information about the funder’s role in the trial. (table 2)

Reporting before and after CONSORT 2001

The reporting of adverse events—overall, or for deaths or antibiotic resistance specifically—did not change after the publication of the CONSORT 2001 Statement (table 3). Provision of the COI statement increased from 2% to 55% of the trials after 2001 (p<0.001), and COIs became more pervasive, increasing from 0% to 14% after 2001 (p<0.001). There was a non-significant increase in provision of the funding statement, from 62% to 70% after 2001 (p=0.077) (table 3).

Table 3.

Reporting adverse events, COI and funding before and after consort 2001 by included studies (N=237 and 195, respectively)

| Reporting | Studies up to 2001 (inclusive) (n=237) |

Studies from 2002 (inclusive) (n=195) |

Significance of difference | |||

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Adverse events reporting | Drug-related adverse events reported (other than death/antibiotic resistance) | |||||

| Yes | 146 | 62 | 121 | 62 | ||

| No* | 91 | 38 | 74 | 38 | p=0.92 | |

| Deaths reported | ||||||

| Yes | 45 | 19 | 42 | 22 | ||

| No* | 192 | 81 | 153 | 78 | p=0.51 | |

| Antibiotic resistance reported | ||||||

| Yes | 93 | 39 | 65 | 33 | ||

| No | 144 | 61 | 130 | 67 | p=0.21 | |

| COI | COI statement provided? | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 2 | 107 | 55 | ||

| No | 232 | 98 | 88 | 45 | p<0.001 | |

| COI present? | ||||||

| Present | 1 | 0 | 27 | 14 | ||

| Absent | 4 | 2 | 80 | 41 | ||

| Unclear (no COI statement provided) | 232 | 98 | 88 | 45 | p<0.001 | |

| Funding | Funding statement provided? | |||||

| Yes | 146 | 62 | 136 | 70 | ||

| No | 91 | 38 | 59 | 30 | p=0.077 | |

*Trials whose reporting of adverse events was unclear were included in the ‘not reported’ category

COI, conflict of interest.

Discussion

We found that overall, nearly 40% of antibiotics trials did not report any adverse events, and there was no change in reporting of adverse events before and after the publication of the CONSORT Statement in 2001. Reporting of antibiotic resistance slightly (although non-significantly) decreased. Nearly three-quarters of the trials failed to provide the COI statement (74%). While 45% of the included trials were industry funded, only 7% reported a COI. Although there was a significant increase in its provision after the publication of the CONSORT Statement. Funding statements were provided by two-thirds of the trials overall, although no increase was observed after CONSORT.

Our findings are consistent with analyses of COI reporting in other areas. A study of 444 RCTs of surgical interventions found, similarly, that 79% of trials did not provide a COI statement, and there was a trend towards increase on its provision from 0% (of the trials conducted between 1985 and 1994) to 33% (of the trials conducted between 2005 and 2014).10 Fewer than half of 848 studies in supportive and palliative oncology provided COI information, although there was an increase in reporting, from 39% of studies in 2004 to 55% in 2009.7 However, funding information was provided in only 41% of the studies. An analysis of 374 studies in critical care also showed a trend towards increased reporting of conflicts of interest (from 4% of studies in 2001 to 84% in 2016),6 and in reporting of funding (from 17% to 59%, respectively). Why funding information provision in supportive and palliative oncology, or critical care, is lower than in trials of antibiotics (66%) is unclear.

Our finding of poor reporting of death is consistent with the results of a similar study that analysed a random sample of trials.24 This study of 500 randomly selected records in Clinical Trial registry found, similarly, that only 123 records (25%) reported the number of deaths.

We are unaware of previous analyses of trends around the reporting of adverse events of antibiotics over time. However, their continued under-reporting is particularly concerning, in light of the estimates that deaths attributable to antibiotic resistance may rise to 10 million per annum by 2050.25

Our study has several limitations. We analysed only the published trials previously included in our convenience sample of three systematic reviews, potentially limiting generalisability to other classes of antibiotics and other non-published trials. However, the included RCTs trialled antibiotics for a large variety of indications and in a wide range of settings. We also relied on the original systematic reviews’ reporting of adverse events in the original trials, which may have introduced errors, although two of the present authors (CDM and AMS) were also involved in conducting those systematic reviews. Although it would have been interesting to analyse the COI and funding reporting by individual journals, it was impossible to do so as their policies change over time and it would have been difficult to identify which policy was in effect at each trial’s publication date. Finally, the results from the macrolides trials (n=183) may bias the results towards better reporting of COI and funding as they are a newer class of antibiotics, compared with cephalosporins and penicillin. The strengths include the large number of included trials (n=432) covering three of the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes, and a 50-year period covered by the trials (1969–2018). The trials included in the analysis were not restricted by language or publication (eg, lower vs higher impact factor journals). Extraction of data on COI and funding from the included RCTs was conducted independently by two pairs of authors, and accuracy was checked by a third author.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that information about adverse events, conflicts of interest and funding remains under-reported in antibiotics trials. The lack of change in reporting of adverse events, and the small decrease in reporting of antibiotic resistance are concerning, although may shift in the coming years by adequately reporting the protocols of clinical trials by using Standard Protocol Items for Randomised Trials checklist,26 27 and by the adoption of checklists specific to reporting antibiotic resistance in prospective studies of antibiotic use, such as the checklist developed by several authors of the present study.28 Pervasiveness of conflicts of interest and funding in trials of antibiotics is unsurprising, as RCTs are expensive to conduct, and public funding sources are limited. However, their presence needs to be transparently reported, so that physicians, patients and other stakeholders can consider that information in assessing the evidence. An additional benefit would be a positive flow-on effect on systematic reviews of primary studies, which currently infrequently report the funding sources for included RCTs,11 despite requirement that this information be provided for studies included in the review.29 Much work remains to be done by research funders, journal editors, clinical trial registries and other research outlets to require and clearly convey this information to consumers of research, although the trends towards increased reporting over time in antibiotics and other areas are encouraging.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Mina_Bakhit

Contributors: AMS and CDM conceived and designed the project. MB, JB, RN, KY and AMS extracted the data. MJ conducted the analyses. All authors (MB, MJ, JB, RN, KY, CDM and AMS) contributed to writing and critical revisions of drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

The full list of RCTs analysed is provided in online supplemental appendix 1. Further data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

As the data source for this analysis consists of published trials and is publicly available, we did not seek human research ethics approval.

References

- 1.Bothwell LE, Greene JA, Podolsky SH, et al. Assessing the gold standard — lessons from the history of RCTs. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2016;374:2175–81. 10.1056/NEJMms1604593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018;125:1716. 10.1111/1471-0528.15199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannidis JP, Lau J. Completeness of safety reporting in randomized trials: an evaluation of 7 medical areas. JAMA 2001;285:437–43. 10.1001/jama.285.4.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips R, Hazell L, Sauzet O, et al. Analysis and reporting of adverse events in randomised controlled trials: a review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024537. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:454–65. 10.1001/jama.289.4.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darmon M, Helms J, De Jong A, et al. Time trends in the reporting of conflicts of interest, funding and affiliation with industry in intensive care research: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:1669–78. 10.1007/s00134-018-5350-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui D, Reddy A, Parsons HA, et al. Reporting of funding sources and conflict of interest in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:421–30. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:Mr000033. 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandrioli D, Kearns CE, Bero LA. Relationship between research outcomes and risk of bias, study sponsorship, and author financial conflicts of interest in reviews of the effects of artificially sweetened beverages on weight outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Probst P, Grummich K, Klaiber U, et al. Conflicts of interest in randomised controlled surgical trials: systematic review and qualitative and quantitative analysis. Innov Surg Sci 2016;1:33–9. 10.1515/iss-2016-0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA, et al. Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. JAMA 2011;305:1008–17. 10.1001/jama.2011.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kolfschooten F. Conflicts of interest: can you believe what you read? Nature 2002;416:360–3. 10.1038/416360a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeAngelis CD, Fontanarosa PB. Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence. JAMA 2008;299:1833–5. 10.1001/jama.299.15.1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Consort 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med 2010;8:18. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276:637–9. 10.1001/jama.276.8.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2001;1:2. 10.1186/1471-2288-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabbri A, Chartres N, Bero LA. Study sponsorship and the nutrition research agenda: analysis of cohort studies examining the association between nutrition and obesity. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:3193–9. 10.1017/S1368980017002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkansah N, Nguyen T, Iraninezhad H, et al. Randomized trials assessing calcium supplementation in healthy children: relationship between industry sponsorship and study outcomes. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:1931–7. 10.1017/S136898000900487X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner K, Carboni-Jiménez A, Benea C, et al. Reporting of drug trial funding sources and author financial conflicts of interest in Cochrane and non-Cochrane meta-analyses: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e035633. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillies M, Ranakusuma A, Hoffmann T, et al. Common harms from amoxicillin: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials for any indication. CMAJ 2015;187:E21–31. 10.1503/cmaj.140848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen MP, Scott AM, McCullough A, et al. Adverse events in people taking macrolide antibiotics versus placebo for any indication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1:CD011825-CD011825. 10.1002/14651858.CD011825.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCullough A, Scott AM, Macindoe C. Adverse events in patients taking cephalosporins versus placebo for any indication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;2020:CD012435. 10.1002/14651858.CD012435.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drazen JM, de Leeuw PW, Laine C, et al. Toward more uniform conflict disclosures: the updated ICMJE conflict of interest reporting form. Croat Med J 2010;51:287–8. 10.3325/cmj.2010.51.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earley A, Lau J, Uhlig K. Haphazard reporting of deaths in clinical trials: a review of cases of ClinicalTrials.gov records and matched publications-a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001963. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Neill J, Davies S, Rex J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations, 2014. Available: http://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf

- 26.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakhit M, Del Mar C, Scott AM, et al. An analysis of reporting quality of prospective studies examining community antibiotic use and resistance. Trials 2018;19:656. 10.1186/s13063-018-3040-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045406supp001.pdf (416.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The full list of RCTs analysed is provided in online supplemental appendix 1. Further data are available from the authors on reasonable request.