Abstract

Objective:

The calcaneus is a rare location for the development of primary bone tumours. The purpose of the study is to review the imaging findings in a cohort of patients presenting with tumours and tumour-like lesions of the calcaneus and to develop a more structured approach to the diagnosis of calcaneal lesions.

Methods:

A retrospective study with a collection of 167 cases of calcaneal tumours and tumour-like lesions from our tertiary orthopaedic oncology institution over a period of 13 years. Cases were reviewed by two consultant musculoskeletal radiologists and the location of the lesion within the calcaneus and demographics of the patient were noted for each case. A diagnostic algorithm, which is based on patient age and tumour location, was then extrapolated.

Results:

Out of the 167 cases, we identified 24 different calcaneal pathologies which included both tumours and tumour-like lesions. The most common being simple bone cysts (18.3% of cases) and intra-osseous lipoma (15% of cases) sited in the diaphyseal equivalent of the calcaneus. A diagnostic algorithm was formulated, which describes the most common location of the different pathologies including both benign and malignant pathologies, subdivided by age.

Conclusion:

Our algorithm should help the radiologist narrow down the differential diagnosis when evaluating calcaneal lesions.

Advances in knowledge:

This article provides a radiological approach to calcaneal lesions.

Introduction

Tumours in the foot account for 3% of all skeletal tumour types. Primary calcaneal malignancies are rare and account for 31% of benign and 35% of malignant tumour types in the foot.1

Given the rarity of primary malignancies, the correct diagnosis can be missed for months especially as most are slow-growing and found incidentally. Patients most commonly present with pain and swelling.

The largest case series to date is of 131 cases of malignant calcaneal lesions which was published by Newman et al2. In our study, we present 167 cases which include both malignant calcaneal lesions and other tumour-like lesions. Using the data collected, we propose diagnostic diagrams for calcaneal lesions which could aid in their assessment. In some cases, a likely diagnosis may be reached based on the patient’s age and the location of the lesion alone.

Methods

The study was approved by the local research committee and the need for consent was waived. Reports on the radiology management system (RMS) of all foot examinations between 2007 and 2020 were searched using the term ‘calcaneus’ Calcan* + (lesion or mass or tumour). Patient data before 2007 was excluded due to lack of availability of imaging on PACS.

These entries were then reviewed to identify patients with a true calcaneal lesion on available imaging, which included X-ray, CT and MRI. All lesions of the calcaneus were included together with non-neoplastic conditions such as infection.

Each case was reviewed retrospectively by two fellowship-trained Musculoskeletal Radiology Consultants, one with over 10 years’ experience. For the purposes of this study, the calcaneus was considered as a long bone with different anatomical equivalents: apophysis (epiphysis), metaphysis (region adjacent to cartilage plate/subarticular) and diaphyseal (body). The calcaneus has six surfaces and is divided into epiphyseal, metaphyseal and diaphyseal equivalents (Figure 1). Of note, the calcaneus is considered to have three epiphyseal equivalents, the superior epiphysis corresponds to the superior subtalar surface, the anterior epiphysis is confluent with the anterior calcaneal surface articulating with the cuboid, the posterior epiphyseal equivalent or apophysis is where the Achilles tendon inserts. The diaphysis comprises the body of the calcaneus. The anterior and posterior metaphysis bridges the anterior and posterior epiphyses to the diaphysis, respectively. This concept described by Kricun ME in 1993 was used to describe the location of the calcaneal lesions more accurately.

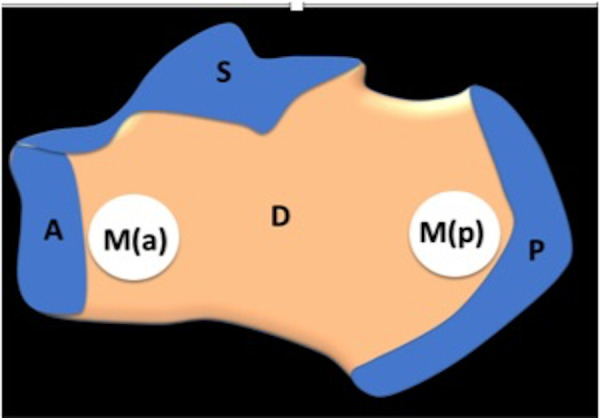

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the calcaneus demonstrating the three epiphyseal equivalent : posterior (P), superior (S), anterior (S), diaphysis (D) and anterior (a) and posterior (p) metaphyses (M)

The data recorded included the patient demographics and the location of the lesion which as described was based on the anatomical equivalent of a long bone. The pathology of the lesion was also recorded based on either definite histology where available, or in the case of a simple bone cyst for example, based on the imaging which is diagnostic.

The lesions were then grouped according to their location in the calcaneum and according to age. Diagrams were then created (Figures 2–4), which shows the percentage result of the more common lesions in the respective locations.

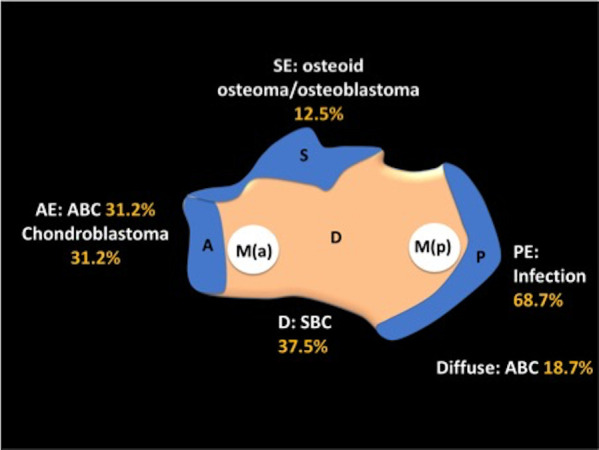

Figure 2.

Diagnostic flow chart to aid assessment of calcaneal lesions in patients < 20 years of age. AE, Anterior epiphyseal equivalent; D, Diaphyseal; PE, Posterior epiphyseal equivalent; SE, Superior epiphyseal equivalent.

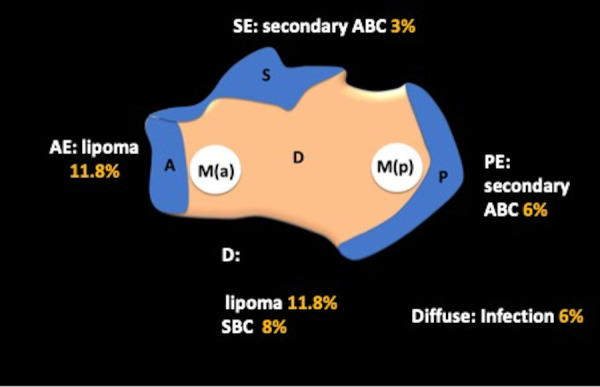

Figure 3.

Diagnostic flow chart to aid assessment of calcaneal lesions in patients 20–40 years of age. AE, Anterior epiphyseal equivalent; D, Diaphyseal; PE, Posterior epiphyseal equivalent; SE, Superior epiphyseal equivalent.

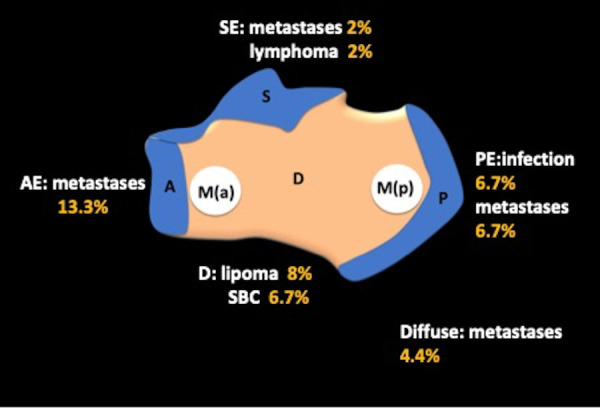

Figure 4.

Diagnostic flow chart to aid assessment of calcaneal lesions in patients > 40 years of age. AE, Anterior epiphyseal equivalent; D, Diaphyseal; PE, Posterior epiphyseal equivalent; SE, Superior epiphyseal equivalent.

Results

The search yielded 167 true calcaneal lesions. Twenty-four different pathologies were identified ranging from intra-osseous lipomas and simple bone cysts to more esoteric lesions such as epithelioid haemangioma (Figure 5). 104 (62.2%) patients were male and 63 (37.8%) were female with an average age of 31 years.

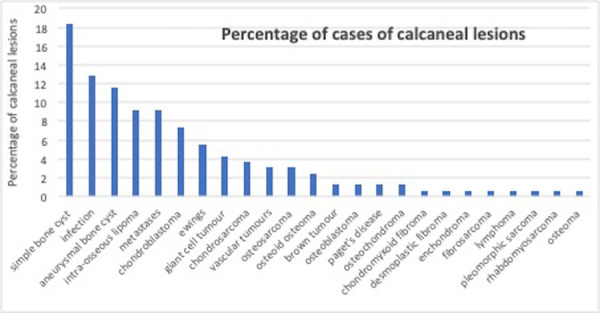

Figure 5.

Clustered bar chart demonstrating the 24 different calcaneal pathologies identified in descending frequency.

Three separate diagnostic diagrams were developed according to age <20 years, 20–40 years and >40 years (Figures 2–4).

In youngest patient group (<20 years), the most common pathologies were primary calcaneal bone lesions such as simple bone cyst (18.3%), aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) (11.5%) and chondroblastoma (7.3%). The most common non-neoplastic pathology in this age group to arising in the posterior epiphysis (posterior epiphyseal equivalent) was infection (12.8%).

The most common lesion in our series was the simple bone cyst. Below the age of 20, it is the most commonly seen lesion in the diaphyseal equivalent or body of the calcaneus. It is typically described in the anterior third of the calcaneus.

The second most common pathology affecting the calcaneus is infection. Calcaneal osteomyelitis accounts for roughly 7–8% of all osteomyelitis cases in adults.3

The superior epiphysis or subarticular surface of the calcaneus demonstrated that in the age group <20 years this was the most common location for osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas. With increasing age, the pathology changes and is more likely to be a secondary ABC in the 20–40 years age group or metastatic lesion in the over 40 s. Osteoid osteomas have a prevalence of 2 to 3% in the calcaneus.4

The second most common lesion that was seen in the anterior epiphyseal equivalent and also as a diffuse lesion is ABC. ABC in the calcaneum is uncommon with the literature quoting only 1.6% of ABCs in the calcaneum.5

Intra-osseous lipoma appeared to be the most common diaphyseal lesion in the age Groups 20–40 years and >40 years. Approximately 8% of intra-osseous lipomas involve the calcaneus.6

In the older cohort of patients (age >40 years), the more common pathology affecting the calcaneus was metastatic disease. Our study demonstrates that while posterior epiphyseal equivalent was a common location for metastatic disease cases of diffuse and anterior involvement were also seen.7

A few less common pathologies cases were also seen however the numbers were small. For instance, we identified only two cases of osteosarcoma and overall incidence of osteosarcoma in the foot is rare with an incidence of 0.2–2% of all cases.8 No specific location was identified and in the two cases one was diffuse and the other involved the posterior aspect of the calcaneus. There were at least nine cases of calcaneal Ewing’s sarcoma identified in our study with the most common location being the diaphysis/diaphyseal equivalent.

Discussion

The calcaneus is the first tarsal bone to ossify and is the only tarsal bone to have a secondary epiphysis.9 The principle that the location of lesions in the short tubular bones of the foot is equivalent to that of long bones was used in this study to describe the location of the different pathologies in the calcaneus. This is not the first time the calcaneus has been compared to a long bone.10

We found that the radiological characteristics and location (epiphyseal, metaphyseal and diaphyseal) of the tumours and tumour-like lesions in the calcaneus mirrored that of long bones leading to a helpful diagnostic algorithm.

The features of the lesions identified in our study follow the imaging characteristics of the same lesions in long bones. For instance, the most common pathology identified in the <20 year cohort of patients is the simple bone cyst. This demonstrated a typical location in the diaphyseal equivalent of the calcaneal body and features in keeping with a cyst with high signal on water-sensitive MRI sequences and low T1W signal. (Figure 6)

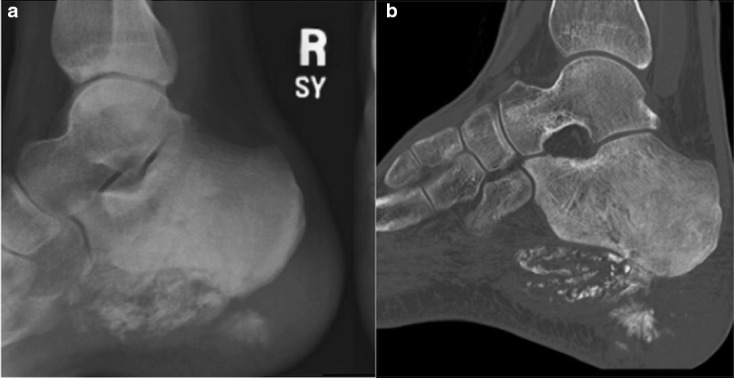

Figure 6.

Simple bone cyst. Typical site and appearances for this benign lesion. Lateral radiograph (Image a) shows a lytic diaphyseal lesion and Sag STIR (Image b) demonstrates a high T2W simple bone cyst.

The second most common calcaneal pathology identified is infection. This showed a predilection for the posterior epiphysis/apophysis. The calcaneal apophysis is equivalent to the epiphysis of long bones. In children, infection tends to spread to the calcaneal apophysis haematogenously. Most cases of haematogenous osteomyelitis begin in the posterior meta-epiphyseal region. Infection may spread across the cartilage plate to involve the nearby apophysis.9 Our study demonstrates that infection is the most common pathology to involve the posterior epiphyseal/metaphyseal region in most age groups but particularly in children. Radiographically this presents with bone destruction along its plantar aspect and associated soft-tissue swelling, which is the earliest sign. In children, infection may cause early ossification or destruction of the apophysis. Chronic osteomyelitis typically leads to increased bony sclerosis. MRI findings range from increased STIR and low T1 signal (oedema) to abscess formation, sinus tracts seen as areas of peripheral enhancement.11 The presence of fat within the marrow involved is a good indication that the pathological process is infection rather than malignancy.12 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

X-ray (a) demonstrating mixed lytic/sclerotic change in the posterior epiphyseal equivalent. This is confirmed on sagittal CT reconstructions (b) and STIR sagittal MRI (c), which depicts marked bony oedema involving the posterior metaphysis and surrounding soft tissues. These are features of osteomyelitis and this occurs most commonly in the posterior epiphyseal equivalent

The posterior calcaneus is also a common location for metastatic disease with 28% of metastases occurring in the posterior calcaneus, in view of the rich vascularity. It has been reported that calcaneal metastases are more likely to occur from subdiaphragmatic sites of primary disease, while supra diaphragmatic primary tumours are more likely to metastasize to the hand and upper extremity.13 The appearances of metastatic disease on imaging is varied. Most metastases are osteolytic on radiographs, but osteoblastic metastases may also occur depending on the primary. (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Lateral X-ray of the calcaneum shows marked destruction (a) of the calcaneum and distal tibia (white arrow). Sagittal T1 MR image shows malignant infiltration with low T1 signal involving the whole of the calcaneum with an epicentre in the posterior meta-epiphyseal equivalent. Low T1 focus also seen in the distal tibia (white arrow). This was diffuse metastases from renal carcinoma.

The lesions identified in this study maintained the imaging features seen in long bones. For instance, the chondroblastomas in this study (7.3%) were seen in the epiphyseal equivalents of the calcaneum, in particular the anterior epiphyseal equivalent was the most common site. On MRI, the typical finding of extensive perilesional oedema was present in all the cases.

Aneurysmal bone cysts also had a prevalence for the anterior epiphyseal equivalent, likely as they tend to arise secondary to a pre-existing chondroblastoma. The typical fluid–fluid levels are diagnostic on fluid-sensitive MRI sequences.

A few esoteric cases were also seen; however, the numbers were too small to pinpoint the frequency of occurrence in specific locations. (Figure 9,10, 11) Two cases of osteosarcoma and nine cases of Ewing’s sarcoma were identified.

Ewing’s sarcoma of the foot is very rare but when it occurs it is more likely to affect the calcaneus. (Figure 11) Due to its aggressive appearances it may be misdiagnosed as osteomyelitis. In the calcaneus, however, osteomyelitis usually develops posteriorly near the cartilage plate whilst Ewing’s sarcoma is mainly diaphyseal but may involve the whole calcaneus.14

Appearances of osteosarcoma in the calcaneus is similar to that of long bones with an osteolytic/sclerotic pattern of bone destruction.15 (Figure 9).

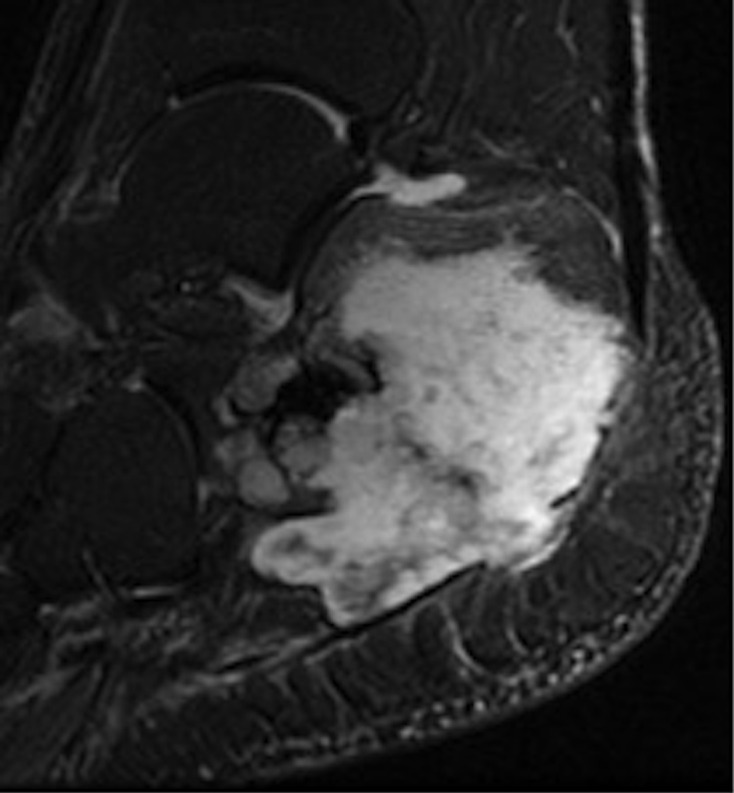

Figure 9.

Radiographic and CT features of osteosarcoma in the calcaneus. Appearances are of an aggressive lesion involving the whole of the calcaneal diaphysis with extra-osseous extension.

Figure 10.

Sagittal STIR MR image depicts typical appearance of a chondroid lesion with aggressive features. High signal on water sensitive sequences with chondroid matrix is typical of a chondroid tumour. The aggressive appearance is in keeping with biopsy proven chondrosarcoma

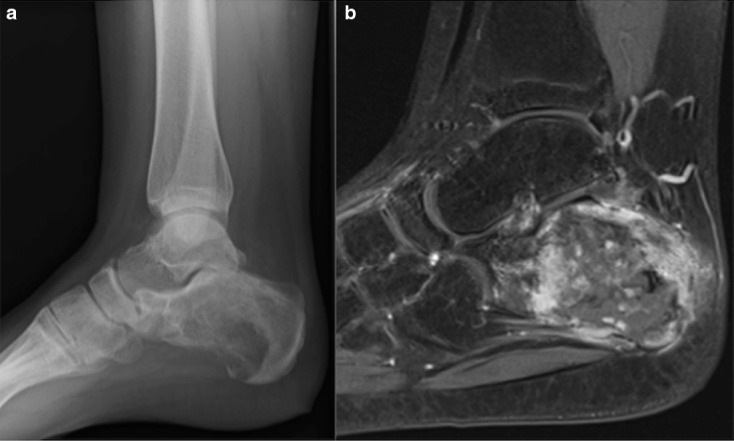

Figure 11.

Radiographic and MRI features of Ewing’s sarcoma in the calcaneum. 5.4% of the 164 calcaneal lesions in our cohort were Ewing’s sarcoma. The majority of cases were centred around the posterior epiphyseal equivalent as shown.

Conclusion

Our study includes the largest number of calcaneal lesions, both tumours and tumour like lesions identified in one study. The diagrams we present based on age and location can act as an aide-memoire for radiologists when they encounter a calcaneal lesion, hopefully simplifying the diagnostic process.

Contributor Information

Christine Azzopardi, Email: chrissyazz@yahoo.com.

Anish Patel, Email: anish.patel4@nhs.net.

Steven James, Email: stevenjames@nhs.net.

Rajesh Botchu, Email: drbrajesh@yahoo.com.

Mark Davies, Email: mark.davies8@nhs.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yan L, Zong J, Chu J, Wang W, Li M, Wang X, et al. Primary tumours of the calcaneus. Oncol Lett 2018; 15: 8901–14. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman ET, van Rein EAJ, Theyskens N, Ferrone ML, Ready JE, Raskin KA, et al. Diagnoses, treatment, and oncologic outcomes in patients with calcaneal malignances: case series, systematic literature review, and pooled cohort analysis. J Surg Oncol 2020; 122: 1731–46. doi: 10.1002/jso.26205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang EH, Simpson S, Bennet GC. Osteomyelitis of the calcaneum. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74: 906–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B6.1447256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai JW, Hong SH, Choi J-Y, Koh YH, Lee JW, Choi J-A, et al. Radiologic diagnosis of osteoid osteoma: from simple to challenging findings. Radiographics 2010; 30: 737–49. doi: 10.1148/rg.303095120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplanoğlu V, Ciliz DS, Kaplanoğlu H, Elverici E. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the calcaneus. J Clin Imaging Sci 2014; 4: 60. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.143732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narang S, Gangopadhyay M. Calcaneal intraosseous lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011; 50: 216–20. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zindrick MR, Young MP, Daley RJ, Light TR. Metastatic tumors of the foot: case report and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982; 170: 219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biscaglia R, Gasbarrini A, Böhling T, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Picci P. Osteosarcoma of the bones of the foot--an easily misdiagnosed malignant tumor. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73: 842–7. doi: 10.4065/73.9.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar R, Matasar K, Stansberry S, Shirkhoda A, David R, Madewell JE, et al. The calcaneus: normal and abnormal. Radiographics 1991; 11: 415–40. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.3.1852935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kricun ME. Imaging of bone tumours. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merlet A, Cazanave C, Dauchy F-A, Dutronc H, Casoli V, Chauveaux D, et al. Prognostic factors of calcaneal osteomyelitis. Scand J Infect Dis 2014; 46: 555–60. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.914241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies AM, Hughes DE, Grimer RJ. Intramedullary and extramedullary fat globules on magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic sign for osteomyelitis. Eur Radiol 2005; 15: 2194–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2771-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malicky ES, Kostic KJ, Jacob JH, Allen WC. Endometrial carcinoma presenting with an isolated osseous metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1997; 18: 492–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinus WR, Gilula LA, Shirley SK, Askin FB, Siegal GP. Radiographic appearance of Ewing sarcoma of the hands and feet: report from the intergroup Ewing sarcoma study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985; 144: 331–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.2.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma M, Sharma V, Sharma A, Khajuria A. Calcaneal osteosarcoma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2012; 55: 595. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.107845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]