Abstract

Background

This study aimed to examine the sphincter-preservation rate variations in rectal cancer surgery. The influence of hospital volume on sphincter-preservation rates and short-term outcomes (anastomotic leakage (AL), positive circumferential resection margin (CRM), 30- and 90-day mortality rates) were also analysed.

Methods

Non-metastasized rectal cancer patients treated between 2009 and 2016 were selected from the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Surgical procedures were divided into sphincter-preserving surgery and an end colostomy group. Multivariable logistic regression models were generated to estimate the probability of undergoing sphincter-preserving surgery according to the hospital of surgery and tumour height (low, 5 cm or less, mid, more than 5 cm to 10 cm, and high, more than 10 cm). The influence of annual hospital volume (less than 20, 20–39, more than 40 resections) on sphincter-preservation rate and short-term outcomes was also examined.

Results

A total of 20 959 patients were included (11 611 sphincter preservation and 8079 end colostomy) and the observed median sphincter-preservation rate in low, mid and high rectal cancer was 29.3, 75.6 and 87.9 per cent respectively. After case-mix adjustment, hospital of surgery was a significant factor for patients’ likelihood for sphincter preservation in all three subgroups (P < 0.001). In mid rectal cancer, borderline higher rates of sphincter preservation were associated with low-volume hospitals (odds ratio 1.20, 95 per cent c.i. 1.01 to 1.43). No significant association between annual hospital volume and sphincter-preservation rate in low and high rectal cancer nor short-term outcomes (AL, positive CRM rate and 30- and 90-day mortality rates) was identified.

Conclusion

This population-based study showed a significant hospital variation in sphincter-preservation rates in rectal surgery. The annual hospital volume, however, was not associated with sphincter-preservation rates in low, and high rectal cancer nor with other short-term outcomes.

This manuscript describes the influence of hospital of surgery on patients’ likelihood of receiving sphincter-preserving surgery in rectal cancer treatment. The authors believe that awareness regarding this subject, and the potential differences between doctors and their preferences regarding choice of surgical treatment, need to be addressed. Besides hospital variation, the influence of annual hospital volume regarding rectal resections on sphincter-preservation rate and short-term outcomes are shown. Most of the previously reported effects of hospital volume on short-term outcomes seem to be resolved, probably due to ongoing clinical auditing and multidisciplinary team meetings.

Introduction

Surgery, often in combination with (chemo)radiotherapy, is standard in the treatment of rectal cancer. The majority of patients can be treated with a sphincter-preserving procedure, but this is mainly dependent on the location of the tumour in the rectum. Tumours located in the distal rectum, involving the internal or external sphincter are often treated with an abdominoperineal resection (APR). In the more proximal rectum, when a sphincter-preserving procedure is technically possible, other factors such as age, co-morbidity or preoperative impaired anal sphincter function are important for the decision or whether to perform a sphincter-preserving procedure or an end colostomy1. Also, hospital volume has been reported as a factor influencing sphincter preservation, where high-volume hospitals seem to be associated with higher rates of sphincter preservation2–5. In a Swedish study, significant variation in permanent ostomy rates after anterior resection between different regions was described6.

Previous nationwide population-based studies have reported the effect of hospital variation on the probability of patients receiving a curative treatment for colon, gastric, pancreatic and oesophageal cancer7–10. Recently, a significant hospital variation regarding neoadjuvant treatment in rectal cancer has been described11. Furthermore, differences in postoperative outcome due to variability based on hospital type and volume were reported in pancreatic and upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery12–15. The influence of hospital volume on colorectal surgery was described in a Dutch nationwide study between 2005 and 2012, and the authors reported a higher 30-day postoperative mortality rate in low-volume hospitals compared with high-volume hospitals. Anastomotic leakage (AL) rate and overall survival (OS) rate were equal between the different hospital volume groups in this study16. Since 2012, however, an annual minimum volume of 20 rectal cancer resections per hospital has been recommended in the Netherlands.

The aim of this study was, therefore, to examine hospital variation and hospital volume using data of the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) on the probability of undergoing sphincter-preserving rectal surgery. Second, the influence of hospital volume on positive circumferential resection margin (CRM), AL and 30- and 90-day mortality rates was analysed.

Methods

Netherlands Cancer Registry

Data were obtained from the nationwide population-based NCR. This registry collects data for all newly diagnosed patients with cancer from hospitals in the Netherlands, comprising approximately 17 million inhabitants. The NCR is based on notification of all newly diagnosed malignancies in the Netherlands by the national automated pathological archive (PALGA). Additional sources are the national registry of hospital discharge. Specially trained data managers of the NCR routinely extracted information on diagnosis, tumour characteristics and treatment from the medical records. Quality of the data is high, and data completeness is estimated to be more than 95 per cent17. Information on vital status was obtained through an annual linkage with the Municipal Administrative Database, in which all deceased and emigrated persons in the Netherlands are registered. Tumour staging was performed using the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification, according to the edition valid at the time of cancer diagnosis (6th and 7th edition)18. This study was approved by the Privacy Review Board of the NCR and does not require approval from an ethics committee in the Netherlands.

Patients and surgical procedure

All patients diagnosed with non-metastasized (cT1-4N0-2M0) rectal cancer between 2009 and 2016 who underwent surgery in the Netherlands were included. Information regarding surgical procedure was extracted from the NCR. Abdominoperineal resection (APR) and a Hartmann’s procedure (Hartmann) were defined as the end colostomy group. Low anterior resection (LAR) was assigned to the sphincter-preserving group. Both transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) were assigned to the local excision (LE) group. Patients who underwent salvage total mesorectal excision (TME) after LE were excluded. A positive pathological CRM was defined as 1 mm distance or less between the tumour and the resection margin. AL was defined as the presence of contrast extravasation or as an abscess near the anastomosis requiring surgical or radiological intervention and was only recorded as such if it was necessary within 2 months after primary anastomosis.

Statistical analysis

The observed variation of all different surgical strategies (end colostomy, sphincter-preserving, LE) was presented as a figure based on hospital of diagnosis. Since LE is not performed in all hospitals in the Netherlands, this approach was excluded from further analyses. All patients were assigned to three subgroups based on tumour distance from the anal verge, 5 cm or less (low rectal cancer), more than 5 cm to 10 cm (mid rectal cancer) and more than 10 cm (high rectal cancer) respectively. Three separate figures were created to display the observed hospital variation regarding sphincter-preserving surgery for each subgroup based on hospital of surgery. Analysis regarding hospital variation was based on the hospital in which the surgical procedure was performed, although the choice of surgical procedure was made by the operating surgeon. Hospitals with fewer than 10 cases during the whole period between 2009 and 2016 were defined as outliers in subanalyses and therefore excluded. Multivariable multilevel logistic regression models were performed to analyse the hierarchically structured data as it accounts for the dependency of patients within hospitals. Patient (age, gender) and tumour (cT stage, cN stage, differentiation grade) characteristics were added to the multilevel models, based on multivariable logistic regression models using forward stepwise selection. These models were created for the different groups based on tumour distance from anal verge. Outcome of the multilevel logistic regression models were the probability of undergoing sphincter-preserving surgery. These probabilities were assessed for each individual hospital of surgery and expressed as an odds ratio with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The likelihood ratio test was used to assess the influence of hospital level on these probabilities. To determine hospital volume, the mean number of resections (excluding LE) per year per hospital over the period 2009–2016 was calculated. Hospital volume was divided into three categories: less than 20, 20–39 and 40 or more resections per year. The lowest volume category was based on the Dutch minimum annual volume norm for rectal cancer. The same cut-offs were used as previously reported11. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine the association between hospital volume and the presence of AL, positive CRM and 30-day and 90-day mortality rates adjusted for gender, age, year of surgical resection, cT stage, cN stage, differentiation grade, tumour height and neoadjuvant treatment. Postoperative 90-day mortality was also investigated19. In the analyses regarding AL, only patients in the sphincter-preserving group were included.

For all analyses P < 0.050 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA/SE version 14.2. (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Patients

Between January 2009 and December 2016, a total of 20 959 patients were diagnosed with non-metastasized rectal cancer (cT1-4, cN0-2, M0) who underwent a surgical procedure. Median age was 67 (range 20–99) years and 63 per cent were male. A low anterior resection was performed in 11 611 patients (sphincter-preserving group) and 1269 patients underwent a TEM or TAMIS (LE group). A total of 8079 patients underwent Hartmann or APR (end colostomy group). Table 1 shows general characteristics of the included population.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients

| Number of patients | |

|---|---|

| All patients | 20 959 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 274 (63.3) |

| Female | 7685 (36.7) |

| Age (years) | 67 (20–99)* |

| <60 | 4670 (22.3) |

| 60–74 | 11 737 (56.0) |

| ≥75 | 4552 (21.7) |

| Distance from anal verge | |

| ≤5 cm | 7691 (36.7) |

| >5 and ≤10 cm | 8042 (38.4) |

| >10 cm | 4119 (19.7) |

| Unknown | 1107 (5.3) |

| cT classification | |

| T1 | 1047 (5.0) |

| T2 | 4923 (23.5) |

| T3 | 10 809 (51.6) |

| T4 | 1536 (7.3) |

| Tx | 2644 (12.6) |

| cN classification | |

| N0 | 11 194 (53.4) |

| N1 | 5931 (28.3) |

| N2 | 3834 (18.3) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | |

| SCRT | 8211 (39.2) |

| CRT | 7185 (34.3) |

| None | 5563 (26.5) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; *values are median (range). SCRT, short course radiotherapy; CRT, chemoradiotherapy

Hospital variation in rectal cancer surgery

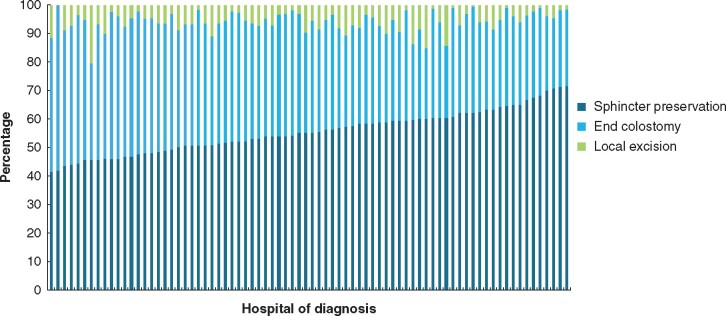

Figure 1 shows the observed distribution of all surgical procedures of all rectal cancer patients according to hospital of diagnosis in the Netherlands between 2009 and 2016. Median sphincter preservation rate was 55.2 (range 41.5–71.7) per cent. Almost all (77 out of 78) hospitals treated or referred patients with rectal cancer for LE, and the median LE rate was 5.5 (range 0–20.5) per cent.

Fig. 1.

Hospital variation in surgical procedure according to hospital of diagnosis (n = 20 959)

Sphincter-preservation rates according to tumour distance from anal verge

Figure 2a shows the hospital variation in observed distribution between sphincter preservation or end colostomy of patients diagnosed with a tumour within 5 cm from the anal verge by hospital of surgery. Median sphincter-preservation rate was 29.3 per cent (ranging from 6.7 to 56.7 per cent between hospitals). Fig. 2b shows the calculated odds ratio per hospital, corrected for age, gender, cT and differentiation grade. In the multivariable multilevel analysis, variability in hospital of surgery was a significant factor in patients’ likelihood for sphincter preservation (P < 0.001). Figure 3a shows the hospital variation in observed distribution of sphincter preservation and end colostomy rates of patients diagnosed with a tumour more than 5 cm to 10 cm from the anal verge by hospital of surgery. Median sphincter-preservation rate was 75.8 per cent, ranging from 37.5 to 98.2 per cent between hospitals. Figure 3b shows the calculated odds ratio per hospital, corrected for age, gender, cT stage and cN stage. In the multivariable multilevel analysis, variability in hospital of surgery was a significant factor in patients’ likelihood for sphincter preservation (P < 0.001). Figure 4a shows the hospital variation in observed distribution of sphincter-preservation and end colostomy rates of patients diagnosed with a tumour more than 10 cm from the anal verge. Median sphincter preservation rate was 87.9 per cent, ranging from 65.4 to 100 per cent between hospitals. Figure 4b shows the calculated odds ratio per hospital of surgery, corrected for age, gender, cT stage and cN stage. In the multivariable multilevel analysis, variability in hospital of surgery was a significant factor in patients’ likelihood for sphincter preservation (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Low rectal cancer

a Hospital variation in sphincter-preserving surgery in low (0–5 cm from anal verge) rectal cancer (n = 7116). b Odds ratios of receiving a sphincter-preserving procedure in low rectal cancer corrected for age, gender, cT and differentiation grade

Fig. 3.

Mid rectal cancer

a Hospital variation in sphincter-preserving surgery in mid (more than 5 cm to 10 cm from anal verge) rectal cancer (n = 7599). b Odds ratios of receiving a sphincter-preserving procedure in mid rectal cancer corrected for age, gender, cT and cN status

Fig. 4.

High rectal cancer

a Hospital variation in sphincter-preserving surgery in high (more than 10 cm from anal verge) rectal cancer (n = 3975). b Odds ratios of receiving a sphincter-preserving procedure in high rectal cancer corrected for age, gender, cT and cN status

Influence of hospital volume on sphincter-preservation rates and outcomes

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine whether annual hospital volume of rectal cancer surgery influenced sphincter-preservation rates. In the low (0 to 5 cm) and high (10–15 cm) rectal cancer groups, no effects of annual hospital volume on the odds of sphincter preservation were observed. In the mid (more than 5 cm to 10 cm) rectal cancer group, however, a borderline significant (odds ratio 1.20, 95 per cent c.i. 1.01 to 1.43) higher rate of sphincter preservation was seen in the low-volume surgery group.

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses on sphincter-preserving surgery according to tumour height and annual hospital volume

| Number | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Low rectal cancer (≤5 cm) | ||

| <20 resections/year | 845 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 2783 | 1.11 (1.00, 1.25) |

| ≥ 40 resections/year | 3497 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Mid rectal cancer (>5 and ≤10 cm) | ||

| <20 resections/year | 910 | 1.20 (1.01, 1.43) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 2883 | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 3806 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| High rectal cancer (>10 cm) | ||

| <20 resections/year | 465 | 1.07 (0.77, 1.48) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 1521 | 0.88 (0.71, 1.09) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 1995 | 1.00 (Reference) |

Adjusted for gender, age, year of surgical resection, cT stage, cN stage, differentiation grade and neoadjuvant treatment. Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to determine the association between annual hospital volume of rectal cancer surgery and short-term outcomes (AL, positive CRM rate, 30- and 90-day mortality rates). No effect of annual hospital volume on the three short-term outcome parameters was found, after adjustment for known case-mix variables (gender, age, year of resection, cT stage, cN stage, differentiation grade, distance of tumour to anal verge and neoadjuvant treatment; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of anastomotic leakage, positive circumferential resection margin, postoperative 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality according to annual hospital volume

| Number | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|

| Anastomotic leakage | ||

| <20 resections/year | 1326 | 0.98 (0.82, 1.17) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 4114 | 1.01 (0.90, 1.14) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 5216 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Positive CRM | ||

| <20 resections/year | 2026 | 1.05 (0.87, 1.28) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 6368 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 8118 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 30-day mortality | ||

| <20 resections/year | 2379 | 1.20 (0.86, 1.67) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 7592 | 1.07 (0.84, 1.36) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 9719 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 90-day mortality | ||

| <20 resections/year | 2379 | 1.09 (0.83, 1.44) |

| 20–39 resections/year | 7592 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.30) |

| ≥40 resections/year | 9719 | 1.00 (Reference) |

Adjusted for gender, age, year of surgical resection, cT stage, cN stage, differentiation grade, tumour height and neoadjuvant treatment. Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. CRM, circumferential resection margin.

Discussion

This nationwide population-based study revealed substantial hospital variance in sphincter-preservation rates in rectal cancer surgery, even after adjustment for case-mix factors. The median sphincter-preserving surgery rate was 55.2 per cent of all rectal cancer surgical procedures. The sphincter was less often preserved in patients with tumours within 5 cm of the anal verge compared with patients with more proximal rectal tumours of more than 5 cm to 10 cm, and more than 10 cm from the anal verge. Differences in overall sphincter preservation were not related to annual hospital volume of rectal cancer procedures. Moreover, hospital volume did not influence AL rate, positive CRM rate or 30- and 90-day mortality rates. Sphincter preservation in the low and high rectal cancer groups was not influenced by annual hospital volume. In the subgroup of mid rectal cancer patients, however, a significantly higher association of sphincter-preserving surgery was observed in the low-volume hospitals compared with the high-volume hospitals. This was the result of subgroup analysis. A possible explanation for this difference might be due to unmeasured case mix in the patient population. The observation that annual hospital volume was not related to sphincter-preservation rate was different from previous studies reporting more sphincter-preserving surgery rates for high-volume hospitals4,20. A recent paper from France showed that sphincter-preserving surgery was more frequently performed in high-volume centres (at least 41 cases per year) compared with low-volume centres (10 or fewer), although no subgroup analysis regarding tumour height was done21. Another study also demonstrated higher sphincter preservation in high-volume centres when a cut-off of 20 resections per year was used to define a high-volume centre20. In the present cohort, annual volumes are generally much higher, and fewer than 20 was considered low volume, so these results are difficult to compare with those of previous studies. Moreover, most data from these previous studies are from more than a decade ago, while the present study reflects rectal cancer surgery in a recent era of predominantly laparoscopic TME surgery. A more recent study demonstrated less sphincter preserving in cT1-3 patients in low-volume hospitals (1–20 per year) compared with high-volume hospitals (50 or more per year)22. However, the authors did not perform a multivariable analysis, the study period was slightly earlier and research patients with distant metastasis were excluded.

Whether sphincter-preserving surgery is conducted probably depends on variety of selection standards, experience and functional expectation23,24. Surgeons’ experience and the incidence of AL, possibly also play a role in counselling patients and surgical strategy25. Therefore, patients’ preferences and patient-related factors are crucial and should be taken into account26. Decision tools could refine preoperative counselling, reduce selection bias and tailor individual approaches. From a patient’s perspective, a stoma could be undesirable, impair self-image and influence quality of life (QoL)27. Moreover, stoma-related complications as well as serious psychological problems after rectal cancer surgery might undermine QoL28. Nevertheless, stoma disadvantages need to be weighed against anastomotic complications or low anterior resection syndrome, which can be severely disturbing in daily life29.

In contrast to the present findings, an independent association of CRM positivity and hospital volume was documented in a study including more than 5000 rectal cancer patients undergoing primary resection in 2011–2012. A 1.5-fold higher risk of CRM involvement was observed in low-volume hospitals30. Another Dutch study with data from 2008 to 2013 collected from 10 community hospitals in the Southern Netherlands did not, however, show significantly higher CRM involvement in hospitals performing 20 or fewer rectal cancer surgeries per year (low-volume) compared with hospitals executing at least 40 per year (high-volume)31. For defining a high-volume hospital, the same cut-off value of 40 or more in which CRM involvement was unaffected by hospital volume differences was used and, potentially, a higher cut-off could have influenced the present results16,22,32. A Cochrane Review has previously reported volume-related AL in rectal cancer surgery32. Meta-analysis displayed no significant influence of high-volume hospitals in unadjusted studies and a significantly lower association between high‐volume hospitals and AL rate was demonstrated in studies with case-mix adjustment. The included studies in this review used different definitions for AL and were published before 2011. A more up-to-date review with meta-analysis showed a significant association with hospital volume studying morbidity (including AL) overall, but this correlation was not confirmed by two studies that focused on the correlation between hospital volume and AL33. A recent paper based on more than 45 000 patients in a French database showed that 90-day postoperative mortality was lower in high-volume hospitals compared with low-volume centres (10 or fewer rectal cancer surgeries per year)21. A previous Dutch population-based study with data from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated a correlation between hospital volume and postoperative complications. The odds ratio of 30-day mortality was higher in low-volume hospitals than in hospitals performing 40 or more rectal resections annually16. In the present cohort study with data from a more recent time period (2009–2016), differences in 30- and 90-day mortality rates between hospital volumes have been resolved. An overall significant improvement of outcomes (decreased duration of stay, less severe complications and postoperative mortality) in patients with even higher risk profiles throughout the years was reported in the Netherlands34,35. This is probably because of ongoing clinical auditing, evaluating outcome parameters and increased specialization in colorectal surgery34. Furthermore, multidisciplinary team meetings and specialized rectal cancer teams are associated with better treatment strategies, more adherence to guidelines and enhanced care36–38.

As a limitation in this study, information regarding co-morbidity, frailty and baseline sphincter function was lacking and could have contributed to the observed variation between the different hospitals. Furthermore, unmeasured case-mix differences, such as patients’ preferences or systematic differences in hospital distribution of older patients with worse baseline characteristics, might have affected the observed differences in distal rectal cancer surgery. However, it is expected, that due to large numbers, patients were more or less equally divided over the different hospitals. Due to the current definition of AL in the NCR, leaks occurring after 2 months from primary surgery were not included. Further studies are needed for clear understanding which components induce hospital variability in performing sphincter-preserving surgery in rectal cancer patients and to what extent it is undesirable. There is still progress to be made in reducing variation in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer, which is most pronounced in low rectal tumours.

Disclosure. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

T Koëter, Department of Surgery, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

L C F de Nes, Department of Surgery, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Department of Surgery, Maasziekenhuis Pantein, Boxmeer, The Netherlands.

D K Wasowicz, Department of Surgery, Elisabeth TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

D D E Zimmerman, Department of Surgery, Elisabeth TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

R H A Verhoeven, Department of Research, Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

M A Elferink, Department of Research, Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

J H W de Wilt, Department of Surgery, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

References

- 1. Weitz J, Koch M, Debus J, Hohler T, Galle PR, Buchler MW. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2005;365:153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jonker FHW, Hagemans JAW, Burger JWA, Verhoef C, Borstlap WAA, Tanis PJ; Dutch Snapshot Research Group. The influence of hospital volume on long-term oncological outcome after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:1741–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snijders HS, van Leersum NJ, Henneman D, de Vries AC, Tollenaar RA, Stiggelbout AM et al. Optimal treatment strategy in rectal cancer surgery: should we be cowboys or chickens? Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3582–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harling H, Bulow S, Moller LN, Jorgensen T; the Danish Colorectal Cancer Groups. Hospital volume and outcome of rectal cancer surgery in Denmark 1994–99. Colorectal Dis 2005;7:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyerhardt JA, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Schrag D, Ayanian JZ et al. Impact of hospital procedure volume on surgical operation and long-term outcomes in high-risk curatively resected rectal cancer: findings from the Intergroup 0114 Study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:166–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holmgren K, Haapamaki MM, Matthiessen P, Rutegard J, Rutegard M. Anterior resection for rectal cancer in Sweden: validation of a registry-based method to determine long-term stoma outcome. Acta Oncol 2018;57:1631–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bakens MJ, van Gestel YR, Bongers M, Besselink MG, Dejong CH, Molenaar IQ et al. Hospital of diagnosis and likelihood of surgical treatment for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2015;102:1670–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Putten M, Verhoeven RH, van Sandick JW, Plukker JT, Lemmens VE, Wijnhoven BP et al. Hospital of diagnosis and probability of having surgical treatment for resectable gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2016;103:233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Putten M, Koeter M, van Laarhoven HWM, Lemmens V, Siersema PD, Hulshof M et al. Hospital of diagnosis influences the probability of receiving curative treatment for esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 2018;267:303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elferink MA, Wouters MW, Krijnen P, Lemmens VE, Jansen-Landheer ML, van de Velde CJ et al. Disparities in quality of care for colon cancer between hospitals in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:S64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koeter T, Elferink MA, Verhoeven RHA, Zimmerman DDE, Wasowicz DK, Verheij M et al. Hospital variance in neoadjuvant rectal cancer treatment and the influence of a national guideline update: Results of a nationwide population-based study. Radiother Oncol 2020;145:162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molina Rodriguez JL, Flor-Lorente B, Frasson M, Garcia-Botello S, Esclapez P, Espi A et al. Low rectal cancer: abdominoperineal resection or low Hartmann resection? A postoperative outcome analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:958–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. den Dulk M, Putter H, Collette L, Marijnen CAM, Folkesson J, Bosset JF et al. The abdominoperineal resection itself is associated with an adverse outcome: the European experience based on a pooled analysis of five European randomised clinical trials on rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1175–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, Marijnen CA, van Krieken JH, Quirke P. Low rectal cancer: a call for a change of approach in abdominoperineal resection. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9257–9264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mamidanna R, Ni Z, Anderson O, Spiegelhalter SD, Bottle A, Aylin P et al. Surgeon volume and cancer esophagectomy, gastrectomy, and pancreatectomy: a population-based study in England. Ann Surg 2016;263:727–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bos AC, van Erning FN, Elferink MA, Rutten HJ, van Oijen MG, de Wilt JH et al. No difference in overall survival between hospital volumes for patients with colorectal cancer in The Netherlands. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:943–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schouten LJ, Hoppener P, van den Brandt PA, Knottnerus JA, Jager JJ. Completeness of cancer registration in Limburg, The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (7th edn). New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutegard M, Haapamaki M, Matthiessen P, Rutegard J. Early postoperative mortality after surgery for rectal cancer in Sweden, 2000–2011. Colorectal Dis 2014;16:426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hodgson DC, Zhang W, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, Wright WE, Ayanian JZ. Relation of hospital volume to colostomy rates and survival for patients with rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:708–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. El Amrani M, Clement G, Lenne X, Rogosnitzky M, Theis D, Pruvot FR et al. The impact of hospital volume and Charlson score on postoperative mortality of proctectomy for rectal cancer: a nationwide study of 45,569 patients. Ann Surg 2018;268:854–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hagemans JAW, Alberda WJ, Verstegen M, de Wilt JHW, Verhoef C, Elferink MA et al. Hospital volume and outcome in rectal cancer patients; results of a population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rullier E, Denost Q, Vendrely V, Rullier A, Laurent C. Low rectal cancer: classification and standardization of surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abdelsattar ZM, Wong SL, Birkmeyer NJ, Cleary RK, Times ML, Figg RE et al. Multi-institutional assessment of sphincter preservation for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:4075–4080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bakker IS, Snijders HS, Wouters MW, Havenga K, Tollenaar RA, Wiggers T et al. High complication rate after low anterior resection for mid and high rectal cancer; results of a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:692–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee L, Trepanier M, Renaud J, Liberman S, Charlebois P, Stein B et al. Patients' preferences for sphincter preservation versus abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer. Surgery 2021;169:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koeter T, Bonhof CS, Schoormans D, Martijnse IS, Langenhoff BS, Zimmerman DDE et al. Long-term outcomes after surgery involving the pelvic floor in rectal cancer: physical activity, quality of life, and health status. J Gastrointest Surg 2019;23:808–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thyo A, Emmertsen KJ, Pinkney TD, Christensen P, Laurberg S. The colostomy impact score: development and validation of a patient reported outcome measure for rectal cancer patients with a permanent colostomy. A population-based study. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:O25–O33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Emmertsen KJ, Espin E, Jimenez LM et al. International validation of the low anterior resection syndrome score. Ann Surg 2014;259:728–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gietelink L, Henneman D, van Leersum NJ, de Noo M, Manusama E, Tanis PJ et al. The influence of hospital volume on circumferential resection margin involvement: results of the Dutch Surgical Colorectal Audit. Ann Surg 2016;263:745–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Homan J, Bokkerink GM, Aarts MJ, Lemmens VE, van Lijnschoten G, Rutten HJ et al. Variation in circumferential resection margin: reporting and involvement in the South-Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:1485–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jorgensen P, Iversen LH. Workload and surgeon's specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (3) CD005391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chioreso C, Del Vecchio N, Schweizer ML, Schlichting J, Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Charlton ME. Association between hospital and surgeon volume and rectal cancer surgery outcomes in patients with rectal cancer treated since 2000: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:1320–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Neree Tot Babberich MPM, Detering R, Dekker JWT, Elferink MA, Tollenaar R, Wouters M et al. ; Dutch ColoRectal Audit Group. Achievements in colorectal cancer care during 8 years of auditing in The Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1361–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brouwer NPM, Heil TC, Olde Rikkert MGM, Lemmens V, Rutten HJT, de Wilt JHW et al. The gap in postoperative outcome between older and younger patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer has been bridged; results from the Netherlands cancer registry. Eur J Cancer 2019;116:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Leersum N, Martijnse I, den Dulk M, Kolfschoten N, Le Cessie S, van de Velde C et al. Differences in circumferential resection margin involvement after abdominoperineal excision and low anterior resection no longer significant. Ann Surg 2014;259:1150–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oliphant R, Nicholson GA, Horgan PG, Molloy RG, McMillan DC, Morrison DS; West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network. Contribution of surgical specialization to improved colorectal cancer survival. Br J Surg 2013;100:1388–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hall GM, Shanmugan S, Bleier JI, Jeganathan AN, Epstein AJ, Paulson EC. Colorectal specialization and survival in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:O51–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]