Abstract

Plant Pectin acetylesterase (PAE) belongs to family CE13 of carbohydrate esterases in the CAZy database. The ability of PAE to regulate the degree of acetylation of pectin, an important polysaccharide in the cell wall, affects the structure of plant cell wall. In this study, ten PtPAE genes were identified and characterized in Populus trichocarpa genome using bioinformatics methods, and the physiochemical properties such as molecular weight, isoelectric points, and hydrophilicity, as well as the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein were predicted. According to phylogenetic analysis, ten PtPAEs can be divided into three evolutionary clades, each of which had similar gene structure and motifs. Tissue-specific expression profiles indicated that the PtPAEs had different expression patterns. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis showed that transcription level of PtPAEs was regulated by different CO2 and nitrogen concentrations. These results provide important information for the study of the phylogenetic relationship and function of PtPAEs in Populus trichocarpa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02918-1.

Keywords: Bioinformatics analysis, Carbon treatment, Expression patterns, Nitrogen treatment, Pectin acetylesterase, Populus trichocarpa

Introduction

Cell wall is an important component of plant cells. Plant cell wall functions are related to most life activities of plants, such as increasing the mechanical strength of plants, regulating the growth rate of cells, participating in plant material transportation, resisting the damage of pathogens and adversity, and participating in information transmission between cells (Showalter 1993; Miller et al. 1997; Obel et al. 2002). The cell walls of higher plants are mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin and so on (Heredia et al. 1995). Pectin is an important matrix polysaccharide in the cell wall. It has been confirmed that its main chemical components are rhamnogalacturonan (RG-I and RG-II), homogalacturonan (HG), xylogalacturonan (XGA) and galacturonic acids (GalA) (Mohnen 2008), in which up to 80% of acidic carboxyl groups are esterified by methyl or acetyl groups (Anderson 2016).

Pectin acetylesterase (PAE; E.C. 3.1.1.6) can regulate the degree of acetylation of pectin, which deacetylates pectin by cleaving acetyl ester bonds (Gou et al. 2012; Orfila et al. 2012). Pectin acetylation occurs during the secretion of pectin from the Golgi apparatus to the cell wall, and then the acetylated pectin is incorporated into the cell wall (Scheller and Ulvskov 2010; Gou et al. 2012). The changes of physical and chemical properties of pectin components caused by PAE could affect the adhesion of cells and the structure of the cell wall. (Bonnin and Clavurier 2008). PAE and pectin methylesterase (PME) regulate the acetylation and methylation of pectin, by which the cell wall has the ability to adsorb and bind more heavy metal ions, thereby participating in the accumulation and detoxification of heavy metals in the plant cell wall (Krzeslowska 2011). The process detoxification is defined as when some substance exceeds its threshold value and affects the growth and development of plants, the plant will eliminate or disperse the substance to different tissues to reduce the damage to the plant itself by regulating the expression of genes (Zhang et al. 2018).

The diversity of complex carbohydrates is controlled by a panel of enzymes involved in their assembly (glycosyltransferases) and their breakdown (glycoside hydrolases, polysaccharide lyases, carbohydrate esterases), collectively designated as Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZymes) (Lombard et al. 2014). The Carbohydrate-Active enZymes database (CAZy, www.cazy.org) specializes in carbohydrate-active enzymes and classifies them into five classes of enzymes based on their activity and sequence similarity (Lombard et al. 2014). One of them is the class of Carbohydrate Esterases (CEs), consisting of 17 CE families numbered from 1 to 18 with the family CE10 being removed because the vast majority of its members act mostly on non-carbohydrate substrates (Lombard et al. 2010). Plant PAE belong to family CE13 of carbohydrate esterases in the CAZy database (Geisler-Lee et al. 2006; de Souza and Pauly 2015; Cantarel et al. 2009). The phylogenetic analysis showed that 72 plant PAE proteins from 16 species could be divided into 5 clades, among which the AtPAE proteins existed in 4 clades in Arabidopsis thaliana (Philippe et al. 2017). In addition, the study also showed that PAEs had nine conservative motifs including ClDG, PxYh, GgxwC, GS, nWN, rYCDg, GCSxG, NxayDxwQ and HCQ (Philippe et al. 2017). Among them, GCSxG, NxayDxwQ and HCQ may be important conserved motifs of the putative catalytic site (Ileperuma et al. 2007; Kakugawa et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2015; Philippe et al. 2017), but their specific functions are still unclear. The research demonstrated the diversity of AtPAE genes expression profiles, which was consistent with other pectin remodeling enzymes and regulators including PME, PMEI, PLL and PG (Louvet et al. 2006; Senechal et al. 2014).

Pectin is one of the important components of plant cell walls. PAE can regulate the degree of acetylation of pectin and affect the structure of cell wall. So far, studies have found that PAE plays an important role in plant growth and development, fruit hardness and stress defense (Gou et al. 2012; Pogorelko et al. 2013; de Souza et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2018). Tobacco overexpressing poplar PAE1 showed reduced degree of pectin acetylesters and severe male sterility. The study also showed that pectin acetylase affected the remodeling and physicochemical properties of cell wall polysaccharides by regulating the degree of pectin acetylation, thereby affecting the ductility of cells, and played an important structural regulatory role in plants (Gou et al. 2012). Mutations in A. thaliana PAE members (pae8 and pae9) led to an increase in acetate content, and its double mutants showed additive effects, and both exhibited a slower inflorescence growth phenotype, which indicated that the function of these two genes was not redundant, and played an important role in plant growth and development (de Souza et al. 2014). Via quantitative proteomics strategy, study showed that PAE expression was significantly up-regulated in the response of tea leaves to fluoride stress, indicating that PAE was involved in the process of fluoride enrichment and detoxification in leaves (Liu et al. 2018).The transgenic A. thaliana and Brachypodium biscuit which overexpressed Aspergillus nidulans PAE showed significantly reduced the degree of acetylation of pathogens, and the transgenic plants showed greater resistance to Botrytis Cinerea and Bipolaris Sorokiniana. These results suggested that pectin acetylation played a role in the defense of plants against fungal pathogens in monocot and dicot plants (Pogorelko et al. 2013).

It is well known that carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) are essential to the basic life activities as well as normal growth and development of plants. In fact, there are often interactions between carbon and nitrogen metabolism (Sahrawy et al. 2004; Gao et al. 2008; Nunes-Nesi et al. 2010). Exogenous nitrogen can affect the thickening of the cell wall of poplar trees (Euring et al. 2014). The cell wall, as the plant’s largest carbon pool, is also regulated by carbon supply (Verbancic et al. 2018). CO2 is the main carbon source for plants in atmosphere. And due to global climate change (the CO2 index rises) (Niu et al. 2013) and the low availability of nitrogen in the soil (Castro-Rodriguez et al. 2016), the dynamic balance of carbon and nitrogen metabolism is significantly affected. Transcriptome analysis that nitrogen affected poplar cell wall synthesis had shown that PAE expression profile had changed (Lu et al. 2019). Pectin is the important component of the cell wall (Heredia et al. 1995). It is unclear that whether the PAE gene family has an effect on carbon and nitrogen under different conditions or not. It has been published that Populus trichocarpa as a model plant in woody plants, has been completely genome sequenced. (Tuskan et al. 2006). In this study, 10 PtPAEs were identified in P. trichocarpa with bioinformatics methods. Amino acid sequence analysis and multiple sequence alignment showed that they all had conserved PAE domains. In addition, we studied the expression profile of PtPAEs under adequate C vs low N, adequate C vs high N, high C vs low N, and high C vs high N treatments using RT-qPCR technology. This study revealed the composition of the PtPAEs family members and the different expression patterns affected by changes in nitrogen and carbon dioxide. The results lay a theoretical foundation for the study of structure and function of the PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa.

Materials and methods

Identification and analysis of the PtPAEs in Populus trichocarpa

The phytozome v12.1 database (Goodstein D M et al. 2012) was used to search for the amino acid sequences of 12 A. thaliana PAEs (At1g09550, At1g57590, At2g46930, At3g09405, At3g09410, At3g62060, At4g19410, At4g19420, At5g23870, At5g26670, At5g45280 and At3g05910). The HMM file of PAE (PF03238) was downloaded from the Pfam database (Finn et al. 2006) with the obtained sequence as reference, and HMMER 3.0 (Potter et al. 2018) was used to identify putative PAE family members from the P. trichocarpa database. In addition, BlastP search (Xu et al. 2017a) was performed with the AtPAE sequence as reference to obtain candidate genes in the P. trichocarpa database. Finally, we manually deleted genes that do not contain conserved domains according to the plant PAE conserved domains. After screening and identification, ten PAE genes were obtained. We analyzed the characteristics of the amino acid sequence with using the ProtParam tool of the ExPASy program (Wilkins et al. 1999), such as molecular weight, isoelectric points, amino acid number, aliphatic index, and hydrophilic average (GRAVY) score. The cellular location was predicted using the online tool WOLF PSORT (Horton et al. 2007).

Analysis of the gene structure and conserved motifs of PtPAEs

The genome sequences and CDS of PtPAEs were downloaded using Phytozome (Goodstein D M et al. 2012; Tuskan et al. 2006), and then the introns and exons of PtPAEs were analyzed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS2.0, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn) (Guo et al. 2007). The conserved motifs of the protein sequence of PtPAEs were predicted via the online software MEME (Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation, version 4.11.3, http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) (Bailey et al. 2009).

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of PtPAEs

The PtPAE amino acid sequences were aligned using Clustal X (Thompson et al. 1997), and the conserved motifs were checked using MEGA7.0 software (Kumar et al. 2016) to construct a phylogenetic tree (No. of bootstrap replications = 1000) with the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method.

Chromosome distribution and gene duplication events of PtPAEs

The location information of the PtPAEs was retrieved from Phytozome (Goodstein et al. 2012) and PopGenIE (Sjodin et al. 2009) and mapped on the chromosome using the MG2C tool (http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0). Multicollinearity scanning toolbox (MCScanX) was used to analyze the gene replication events of PtPAEs with parameters as default (Wang et al. 2012).

The secondary and tertiary structure prediction of putative PtPAEs

Network Protein Sequence analysis (NPSA) online software (Combet et al. 2000) was used to predict the secondary structure of putative PtPAE proteins. The tertiary structure of putative PtPAE proteins was predicted with the help of the SWISS-MODEL database (Waterhouse et al. 2018).

Gene ontology annotation of PtPAEs

Gene ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al. 2000) annotation of PtPAEs was conducted using Blast2GO v5.2 software (Conesa et al. 2005). Initially, we uploaded all protein sequences of PtPAEs to Blast2GO, and performed BLAST in NCBI online database. After drawing and annotating, GO results and visualization images were downloaded. All procedures were conducted with parameters as default.

The tissue-specific expression patterns of PtPAEs

The tissue-specific expression data of the PtPAEs in mature leaves, young leaves, roots, nodes, and internodes were derived from PopGenIE (Sjodin et al. 2009), and visual images were generated.

Plant materials, growth conditions and treatment

Populus trichocarpa is derived from the State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding (Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China). The seedlings, which were almost 15 cm in height, were cultured for 21 days after being rooted in hydroponic culture. Once established, the seedlings were then moved into a hydroponic box filled with modified 1/2 nitrogen-free Hoagland nutrient solution (Liu et al. 2015). The culture was carried out in a greenhouse under the condition of a 16-h light/8-h darkness cycle and a stable temperature of 25 ℃. The seedlings of P. trichocarpa were treated for 28 days with four respective patterns: 0.1 mM NH4NO3 vs 400 ppm CO2, 5 mM NH4NO3 vs 400 ppm CO2, 0.1 mM NH4NO3 vs 800 ppm CO2, and 5 mM NH4NO3 vs 800 ppm CO2 (Kim et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2013; Euring et al. 2014). During this period, the nutrient solution was renewed every 3 days, and the 1 mM NH4NO3 and 400 ppm CO2 served as the control (Pitre et al. 2007; Qu et al. 2019). Roots, stems, and leaves of the plants were sampled, respectively. The surface nutrient solution was rinsed, and then the excess water was absorbed by absorbent paper. The collected tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at – 80 ℃ for subsequent analysis. The biological replicates were set three times for reliable results.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from different tissues of P. trichocarpa seedlings using RNA extraction kit (Plant RNA Kit; OMEGA), and the RNA concentration was measured and the RNA quality was examined in 1% agarose gel. Then a reverse transcription kit was used (PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit; Takara Bio) to synthesize single-stranded cDNA. Based on the SYBR Green fluorescence program, the RT-qPCR experiment was performed using UltraSYBR Mixture reagent (CWBIO, Beijing, China). The total reaction volume was 20 ul. The specific reaction systems were as follows: 95 ℃ for 10 min, then 95 ℃ for 15 s, 60 ℃ for 1 min for 45 cycles. The PtUBQ7 genes were used as the internal reference gene (Leng et al. 2021), and each reaction was repeated three times. The method of 2−ΔΔCT (Livak and Schmittgen 2001) was used to analyze the RT-qPCR amplification data. The primer sequences used in RT-qPCR in this study were listed in Table S1. TBtools (Chen et al. 2020) was used to generate a heat map of gene expression, and the difference in gene expression level was analyzed with Duncan’s multiple range test method (P < 0.05).

Results

Identification and sequence analysis of PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa

To identify and analyze the PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa, AtPAE in A. thaliana was used as a probe sequence. 10 PAEs were identified through Pfam analysis and HMMER prediction in the P. trichocarpa genome database. PtPAE1-PtPAE10 were named according to their order on the chromosome. The 10 PtPAE genes were analyzed and the parameters, including locus name, chromosome location, protein length, molecular weight, isoelectric point, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) score, are listed in Table 1. The 10 putative PtPAE protein sequences varied from 356 to 462 amino acids (aa) in length and the molecular weight ranged from 40 to 51 kDa. The isoelectric points ranged from 5.71 to 6.67. The nine putative PtPAE proteins were hydrophilic as the GRAVY values were negative among the PtPAE family proteins except the PtPAE7. The putative PAE proteins were predicted to be located in the chloroplast, nucleus, extracellular, and endoplasmic reticulum.

Table 1.

Parameters for the ten identified PAE genes and deduced polypeptides present in the P. trichocarpa genome

| Name | Locus name NCBI |

Locus name Phytozome v12.1 |

Amino acid no | Molecular weight (Da) | Isoelectric points | GRAVY | Aliphatic index | Chromosome location of genes | Cellular localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtPAE1 | XP_024452270.1 | Potri.003G046200 | 394 | 42,917.07 | 8.88 | − 0.139 | 78.25 | Chr03:6,280,211..6283204 ( +) | Chloroplast |

| PtPAE2 | XP_006385133.1 | Potri.004G233900 | 394 | 42,804.58 | 6.59 | − 0.184 | 73.02 | Chr04:23,992,214..23995447 (−) | Chloroplast |

| PtPAE3 | XP_024454679.1 | Potri.004G234100 | 427 | 47,067.55 | 9.14 | − 0.081 | 85.20 | Chr04:24,002,973..24007727 (−) | Nucleus |

| PtPAE4 | XP_006382250.1 | Potri.005G001500 | 419 | 46,542.76 | 8.59 | − 0.199 | 73.87 | Chr05:83,104..87321 ( +) | extracellular |

| PtPAE5 | XP_024458361.1 | Potri.006G084900 | 356 | 40,044.19 | 8.81 | − 0.096 | 88.51 | Chr06:6,424,066..6428890 ( +) | chloroplast |

| PtPAE6 | XP_006378039.1 | Potri.010G004400 | 437 | 49,470.78 | 9.11 | − 0.218 | 69.45 | Chr10:394,553..399064 ( +) | Extracellular |

| PtPAE7 | XP_024437950.1 | Potri.012G142300 | 396 | 43,818.91 | 5.15 | 0.004 | 83.33 | Chr12:15,558,242..15563759 (−) | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| PtPAE8 | XP_002318919.3 | Potri.013G000900 | 419 | 46,466.47 | 7.83 | − 0.239 | 74.32 | Chr13:63,656..67706 ( +) | Extracellular |

| PtPAE9 | XP_002320250.3 | Potri.014G110900 | 462 | 51,208.80 | 5.66 | − 0.172 | 78.70 | Chr14:8,652,283..8657816 ( +) | Extracellular |

| PtPAE10 | XP_002322478.1 | Potri.015G145400 | 393 | 44,249.71 | 8.37 | − 0.083 | 84.68 | Chr15:15,078,303..15083946 (−) | Chloroplast |

The phylogenetic tree of PtPAEs was constructed to further understand the conservative and evolutionary relationships among ten PtPAEs (Fig. 1A), and the distribution of introns and exons among PtPAEs was analyzed. The results showed that PtPAE3 and PtPAE9 contained 13 exons, PtPAE5 containing 11 exons, and the other PtPAE genes containing 12 exons (Fig. 1B). According to the results of MEME motif analysis (Fig. 1C), PtPAE5 protein contains five conserved motifs, PtPAE6 protein containing seven conserved motifs, PtPAE7/9/10 proteins containing eight conserved motifs, and the other PtPAE proteins containing nine conserved motifs. The nine conserved motifs CLDG, PXYH, GGGWC, GS, NWN, RYCDG, GCSAG, NXAYDXWQ and HCQ were included in Motif1, Motif2, Motif3, Motif4, and Motif5 (Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree and structure analysis of ten PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa. A PtPAE phylogenetic tree was constructed according to full-length sequences of PtPAEs with the Neighbor-Joining method; B structure of corresponding PtPAE genes. Yellow represents exons, blue represents upstream/downstream sequences, and black lines represent introns; C conserved motifs in the PtPAEs sequences predicted by online MEME tool. The sequence of the motif was listed in Table S2

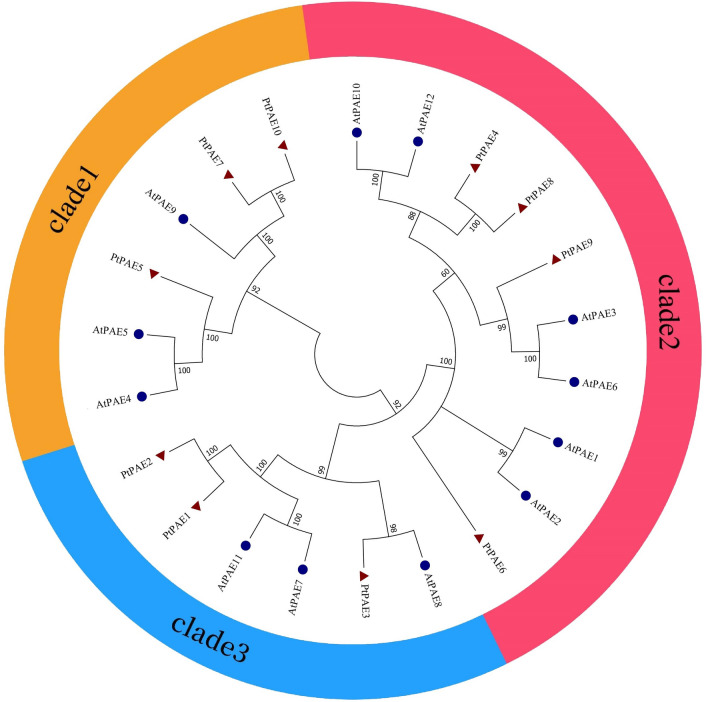

The phylogenetic tree of the PAEs in P. trichocarpa and A. thaliana was constructed (Fig. 2). The 12 AtPAEs were divided into 3 clades, which was consistent with the results of previous studies (Philippe et al. 2017). PtPAE5/7/10 were clustered with AtPAE4/5/9 in clade 1. PtPAE4/8/9/6 were closely related with AtPAE10/12/3/6/1/2, all of which were clustered in clade 2. PtPAE3/1/2 and AtPAE8/7/11 were classified in clade 3.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of PAE proteins in Populus trichocarpa and Arabidopsis thaliana. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The blue circle represents AtPAEs; the red triangle represents PtPAEs. Orange, pink, and blue represent clades 1, 2 and 3, respectively

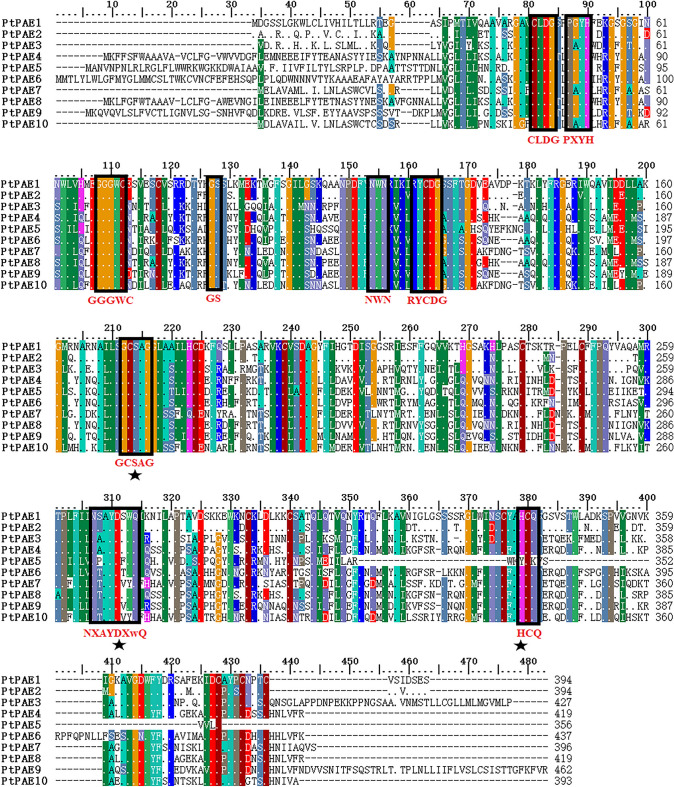

Sequence analysis of PtPAEs

The research found that PAEs had nine conserved motifs, including CLDG, PxYh, gGxwC, GS, Nwn, rYCDg, GCSxG, NxayDxwQ, and HCQ (Philippe et al. 2017). Multiple sequence alignment of ten putative PtPAEs was performed, as shown in Fig. 3. The CLDG, PXYH, GGGWC, GS, NWN, RYCDG, GCSAG, NXAYDXWQ and HCQ conserved motifs existed in nine putative PtPAEs, except putative PtPAE5, which lacks the C-terminal conserved motif HCQ (Fig. 3). It was basically consistent with previous results (Li et al. 2020). The amino acid sequences of the ten putative PtPAEs shared 29.4–88.58% identities (Table S4). The homology of all the ten proteins reached 54.7%. The conserved motifs of PtPAE contained strong catalytically active sites S (Ser), D (Asp) and H (His) residues (Philippe et al. 2017). The deletion of protein conserved motifs, especially the deletion of N-terminal and C-terminal conserved motifs, may be caused by alternative splicing or incomplete sequencing.

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequences alignments of P. trichocarpa PAEs (PtPAEs). The black boxes represent the positions of conserved motifs, and the corresponding amino acid sequences were marked below. The catalytic triad (Ser-Asp-His) sites were marked with a black five-pointed star

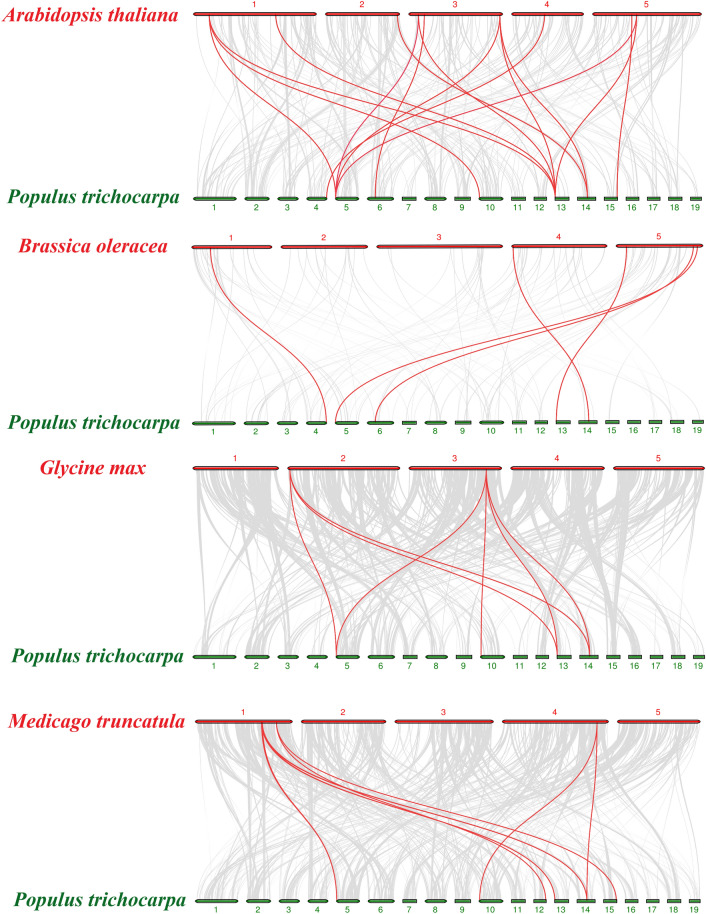

Chromosome distribution and synteny analysis of PtPAE genes

Chromosome locations of ten PtPAEs were mapped based on the genomic information of P. trichocarpa (Fig. 4). The results showed that ten PtPAEs were located on nine different chromosomes (Chr03, 04, 05, 06, 10, 12, 13, 14 and 15). PtPAE2/3 were tandem replications on Chr04. The segmental duplication analysis results of PtPAEs were shown in Fig. 5. PtPAE1/2 had segmental duplication on Chr03/04. PtPAE7/10 had segmental duplication on Chr12/15, and PtPAE4/6/8/9 had segmental duplication on Chr05/10/13/14. To further understand the replications mechanism of PtPAE gene family, we constructed comparative syntenic maps of poplar and other four species, including A. thaliana, Glycine max, Medicago truncatula, and Brassica oleracea (Fig. 6). The results showed that the PtPAEs had highly syntenic gene pairs with the PAE genes of A. thaliana, followed by M. truncatula, G. max and B. oleracea. The numbers of syntenic gene pairs between them were 15, 7, 7, and 5, respectively. The PtPAEs had a high degree of evolutionary difference compared with the PAE genes in other dicotyledonous plants. Some PAEs were related to at least four syntenic gene pairs, such as PtPAE4 and PtPAE8.

Fig. 4.

Chromosome locations of the PAEs in P. trichocarpa. The yellow bar represents the chromosome, and chromosome numbers are shown above the bar graph; scale on the left represents the chromosome length (Mb)

Fig. 5.

Schematic representations of segmental duplications of PtPAEs. The gray line represents all the collinear blocks in the P. trichocarpa genome, and the green line represents repeated PAE gene pairs. The black font at the end of the green line and the scale bar marked on the chromosomes represent the genes name and the length of chromosome (Mb), respectively. Chromosomes numbers were shown at the bottom of each chromosome

Fig. 6.

Synteny analysis of PAEs between P. trichocarpa and the other four plants. Gray lines in background and red lines represent collinear blocks among P. trichocarpa and other plant genomes, as well as PAE gene pairs, respectively. Red or green lines represent chromosomes which were marked with chromosome number at the top or bottom, and the species names were on the left. The four plants are Arabidopsis thaliana (A), Glycine max (B), Medicago truncatula (C) and Brassica oleracea (D)

Secondary and tertiary structure prediction of putative PtPAEs protein

Proteins are the basic unit of life activities, whose functions are determined by their structures. All proteins have a specific spatial conformation, and are adapt to their specific biological functions. The structure and function of proteins are highly unified (Redfern et al. 2009). The secondary and tertiary structure of putative PtPAE proteins were predicted using NPSA and SWISS-MODEL online database. The secondary structure of putative PtPAE proteins were divided into four structural modes: α-helix, β-turn, extended strand, and random coils (Fig. 7A). The coil content of putative PAE proteins is around 40%. The content of α-helix is between 27.53 and 34.77%, and the content of β-turn is around 7% (Table S3). We found that the secondary structures of PtPAE1/2, PtPAE4/8 and PtPAE7/10 are relatively similar, which is consistent with the phylogenetic tree results. Based on the secondary structure, the peptide chain further forms a more complex tertiary structure according to a certain spatial structure. The tertiary structure of all PAE proteins is basically the same (Fig. 7B) with catalytic triad geometry, except PAE5 (Supplementary File 1). The related information of template for putative PtPAE proteins were provided in Table S8.

Fig. 7.

The secondary and tertiary structure of PtPAE proteins. A The secondary structure of PtPAE proteins. The patterns have different colors: blue, α-helix; purple, random coil; red, extended strand; green, β-turn. B Tertiary structure of PtPAE proteins

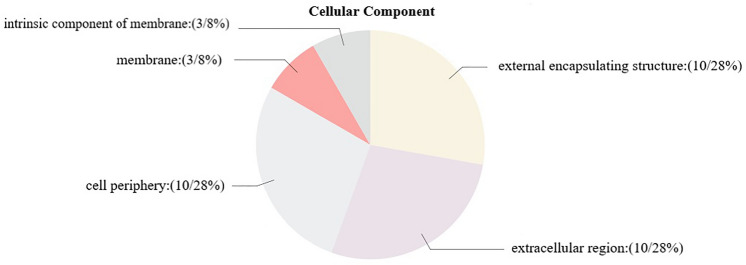

GO annotation

GO annotations can generally be divided into three categories: cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes. Detailed information about the GO annotation of the PtPAEs was provided in Table S7. For cell components, ten putative PtPAE proteins were in the cell periphery, external encapsulating structure and extracellular region. Three putative PtPAE proteins were in the intrinsic component of membrane and membrane (Fig. 8). All PtPAE genes were involved in cellular components and cell wall organization or biogenesis, and perform the molecular functions of PAE (Fig. S1).

Fig. 8.

GO analysis of the PtPAE genes. The gene ontologies were predicted for the categories of cellular components

Tissue-specific expression analysis of the PtPAEs

To analyze the possible roles of the PtPAEs in the developmental processes of P. trichocarpa, the tissue-specific expression of the PtPAE genes was analyzed and visual images were generated (Fig. 9). Next, we used the RT-qPCR method to further verify the previous microarray data (Fig. 9, Fig. S2). The results showed that the expression patterns of PtPAE1/2/7 were similar, and they all had stem-specific expression, while the expression pattern of PtPAE10 was exactly opposite, with the lowest expression in stem. The expression traits of PtPAE5/8/9 were similar, and they were all expressed specifically in roots. PtPAE3 had the highest expression in leaves, but lower in roots and stems, which was exactly opposite with PtPAE6. In general, PtPAE4/5/9 had the highest expression levels in roots. PtPAE1/4 had higher expression levels in stems, and PtPAE3/4 had the highest expression levels in leaves (Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 9, the results of RT-qPCR were generally consistent with microarray analysis and had very different tissue-specific expression patterns in roots, stems and leaves. It was worth noting that PtPAE8/9 showed different expression patterns between RT-qPCR analysis and microarray analysis, which may be caused by differences in experimental materials, such as conditions, sample collection time and so on.

Fig. 9.

Tissue-specific expression analysis of PtPAEs. Tissue-specific expression data on mature leaves, young leaves, roots, nodes and internodes derived from PlantGenIE online tool. Tissue-specific expression analysis on roots, stems and leafs was performed using RT-qPCR and the bar graph was generated. The expression level of each gene in plant roots was normalized to 1.0, and significant difference in gene expression were indicated by letters

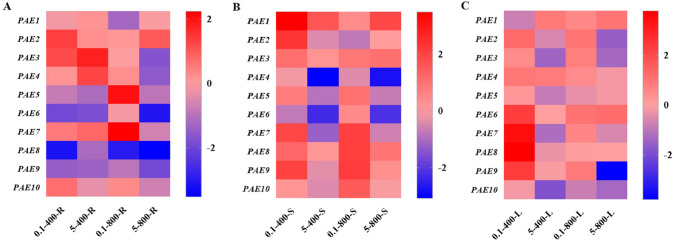

To understand the response of the PtPAEs to carbon and nitrogen, the PAE gene expression patterns under different CO2 and nitrogen concentrations were analyzed using RT-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 10, PtPAE2/3/10 were significantly up-regulated, and PtPAE5/6/8/9 were significantly down-regulated under adequate C and low N treatments in roots. Under adequate C and high N conditions, PtPAE3/4/7 were significantly up-regulated while PtPAE5/6/8/9 were significantly down-regulated in roots. Under high C and low N treatments, the expression of PtPAE5/7 significantly increased, while PtPAE1/8/9 decreased significantly. Under high C and high N conditions, only PtPAE2 was significantly up-regulated, and all genes were significantly down-regulated, except PtPAE1 and PtPAE2. In stem, five PtPAE genes were obviously not responsive to C but had a significant response to N. For example, PtPAE4/7 were suppressed by high N, while PtPAE7/8/9 were induced by low N. PtPAE6 was suppressed under all conditions expect high C and low N, while the expression profiles of PtPAE1 was just opposite. In leaves, PtPAE6/7/8/9 were significantly induced under adequate C and low N conditions, PtPAE9 was significantly suppressed under high C and high N conditions at the same time. PtPAE2/3 were significantly suppressed under high N conditions but not affected by C treatment. PtPAE4 is responsive to neither carbon nor nitrogen. PtPAE10 was suppressed under all conditions except under adequate C and low N.

Fig. 10.

Relative expression level of PtPAE genes under different N and CO2 concentration treatments by RT-qPCR. The expression pattern of PtPAE genes in roots (A), stems (B) and leaves (C) is shown. The concentration of N treatment is 0.1 mM NH4NO3 (low nitrogen concentration) and 5 mM NH4NO3 (high nitrogen concentration), and the concentration of CO2 treatment is 400 ppm (adequate carbon concentration) and 800 ppm (high carbon concentration). The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the transcription level of PtPAEs, and the log2 (sample/control) value of each PtPAE was used to show its relative expression level. In the heat map, the right side was a scale bar, and different colors indicated that the gene expression of the treated sample is up-regulated or down-regulated compared to the control

Discussion

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for plant growth and development (Aerts et al. 1995; Kraiser et al. 2011). Nitrogen availability is a ‘particular challenge’ for plant survival. In natural soil, nitrogen is often an important factor that restricts plant growth and development. Therefore, plants have evolved different metabolic patterns to fulfill the important role in the life cycle of this essential nutrient (Canton et al. 2005). Previous studies showed that poplar formed early secondary cell walls in the elongation zone, and the cell walls were thickened under nitrogen treatment (Euring et al. 2014). In addition, studies also showed that Populus × euramericana and Populus alba led to cell wall thickness decrease under the conditions of elevated CO2 concentration, and carbon partitioning to mobile and structural fractions were affected under high CO2 and N conditions (Luo et al. 2004, 2006). In this study, ten PtPAEs were identified in P. trichocarpa genome. Their physical and chemical properties, gene structure, phylogenetic tree, chromosome distribution and tissue specificity were analyzed. The effect of nitrogen and carbon on the transcription level of PtPAE genes were shown using RT-qPCR. Our results revealed the regulation of PAE expression by carbon and nitrogen treatment, and provided new insights into how carbon and nitrogen affected pectin synthesis in the cell wall during plant development.

So far, the analysis of the evolution, function, and structure of the PAE genes in plants have been very scarce (McCarthy et al. 2014; de Souza and Pauly 2015; Philippe et al. 2017). Eleven putative PAEs were found in P. trichocarpa in the previous study (Philippe et al. 2017). However, we found that the length of Potri.002G185600 was quite different from other PtPAEs after multiple sequence alignments. Potri.002G185600 was ruled out of our study due to its lack of plant PAE conservative motifs. In this study, ten PtPAE genes were identified in the P. trichocarpa genome (Table 1), and were named PtPAE1 to PtPAE10 according to their chromosome locations. This was not consistent with the previous report (Philippe et al. 2017).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that 10 putative PtPAEs and 12 AtPAEs were clustered in 3 different clades, which may be related to their functional diversity. Multiple sequence alignment showed that the GGGWC and NXAYDXwQ conserved motifs existed in ten putative PtPAEs (Fig. 3). Residues of the catalytic triad and oxyanion hole have already been detected and experimentally / structurally confirmed in the Notum protein. The canonical S232-A233 and G126-G127 amides in hNotum participates in formation of the oxyanion hole, thereby providing optimal stabilization during the transition state (Kakugawa et al. 2015). Because all putative PtPAEs proteins have the same catalytic triad (S, D and H) and oxygen anion pore residues (S-A and G-G) (Fig. 3), we only use PtPAE1 and Notum protein for sequence alignment as an example in Figure S3. Multiple sequence alignments between the amino acid sequence of PtPAE1 and a human palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase (4UYU_A) showed that the predicted catalytic triad and oxygen anion pore residues in the PtPAE protein are consistent with the corresponding residues in the Notum protein (Figure S3). The residues of the catalytic triad and the oxyanion hole have already been predicted in AtPAE enzymes, but have not yet been experimentally confirmed (Philippe et al. 2017). The backbone amides of Ser10 and Gly50 and the Od1 of Asn90 formed hydrogen bonds to stabilize the tetrahedral intermediate as an oxyanion hole, and these interactions also rigidified the active site geometry (Kim 2015). The Asn residue found in the NxayDxwQ motif could also contribute to the stability of the active site (Philippe et al. 2017).

In general, gene families expand by tandem duplication and segmental duplication (Cannon et al. 2004). Chromosome location analysis showed that ten PtPAE genes were located on nine different poplar chromosomes, among which PtPAE2/3 were tandem replications on Chr04 (Fig. 4). A genome-wide analysis showed that PtPAE1/2, PtPAE7/10, and PtPAE4/8 had segmental replications (Fig. 5). We found that the amplification drivers of PtPAE gene family are tandem duplication and segmental duplication events. Fortunately, it is the same as the result of the phylogenetic tree of P. trichocarpa, which further proves our results accurate. Synteny analysis of the PAE gene families of P. trichocarpa and four dicotyledonous species showed that at least five genes were collinear with other species (Fig. 6), suggesting that PAE genes were highly conserved among species.

The 3D homology models obtained with each selected PtPAE had a typical similar α/β hydrolase fold and showed the conserved S, D and H amino acid residues (Fig. 3, 7). Among 17 CAZy CE families, 11 families have (α/β/α) sandwich folding and catalytic triad mechanism. Among them, CE2, CE3, CE6, CE12, CE16 and CE17 family members belong to the SGNH hydrolase superfamily (Pfam: CL0264). They are characterized by a flavin-like folding, that is, a three-layer α/β/α structure, in which β-Sheet is composed of five parallel chains. They usually contain the catalytic triad Ser-acid-His, and the catalytic serine is Serine in the GDSL motif. Catalytic Asp and His are separated usually by two residues (Urbanikova 2021). The sugar esterases of CE1, CE5, CE7, CE13 and CE15 also have a (α/β/α) sandwich fold, which is very different from the SGNH hydrolase, belonging to AB hydrolase superfamily (PFAM: CL0028). In addition, the arrangement of the active site residues is also different, and the catalytic serine is located in the G-x-S-x-G motif (x represents any amino acid). The catalytic Asp and His belong to different conserved regions and are relatively far apart. The PAE family (PF03283) was originally classified as a member of the SGNH hydrolase clan, but this has recently been changed and the PAE family now belongs to the AB hydrolase clan (Urbanikova, 2021). The AB hydrolase superfamily is one of the largest group of enzymes with diverse catalytic functions, that share common structural framework, and seem to be related through divergent evolutions (Holmquist 2000). While subunit size and oligomeric organization of family members can vary they all share conserved structural core and contain three topologically similar residues that form a catalytic triad (a nucleophile, catalytic acid and histidine) (Ollis et al. 1992; Carr and Ollis 2009).

In this study, the expression pattern of PtPAEs was analyzed, and it was found that all PtPAE genes expressed in various tissues, but the expression patterns were different (Fig. 9). It is worth noting that the expression patterns of most genes (such as PtPAE1/2 and PtPAE8/9) were consistent with the results of previous evolutionary clades, indicating that they may perform the similar function. The carbon sequestration capacity of trees was limited by the availability of soil nitrogen under higher carbon dioxide concentration (Oren et al. 2001; Sigurdsson et al. 2001). A few genes were proved shown to play an important role in C/N balance although a lot of physiological and molecular studies had been conducted (Zheng 2009). In this study, we found that most PtPAE genes responded to CO2 and nitrogen (Fig. 10). For example, the expression of PtPAE4/6 in stem was only induced by high N. Transcriptional level of some genes had no significant changes when only CO2 or N were changed alone. For example, under low N conditions, PtPAE1 was not significantly affected in roots but PtPAE5 was suppressed under adequate carbon conditions. After increasing CO2 concentration, PtPAE1 was significantly down-regulated and PtPAE5 was induced. We speculated that the gene may be an important function in the C/N balance.

Conclusion

In summary, bioinformatics methods were used to screen and analyze the PAE genes in P. trichocarpa genome, and ten PtPAE genes were identified. All PtPAE genes have similar exon/intron structures and conserved motifs in protein. Phylogenetic analysis showed that PtPAE genes can be divided into three clades. Chromosome locations of PtPAEs showed that PtPAE2/3 were tandem replications on Chr04. The gene duplication and protein structure prediction of the PtPAEs results suggested that PtPAEs family were highly conserved. We found that the expression patterns of PtPAEs in different tissues and their responses to different N and C treatments were different. This study provided a better understanding of the evolution and function of the PtPAE genes, and laid the foundation for further detailed analysis of the gene family.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig S1. GO analysis of the PtPAE genes, molecular function and biological process predicted by gene ontology. (TIF 84 KB)

Supplementary Fig S2. Relative expression level of PtPAE genes in roots, stems and leaves is shown by RT-qPCR. The 2-ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the transcription level of PtPAEs, and the log2 (sample/control) value of each PtPAE was used to show its relative expression level. In the heat map, the right side was a scale bar, and different colors indicated that the gene expression of the treated sample is up-regulated or down-regulated compared to the control. (TIF 14 KB)

Supplementary Fig. S3. Multiple sequences alignments between the amino acid sequence of PtPAE1 and a human palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase (4UYU_A). The catalytic triad in 4UYU is shown in red box; the canonical S-A and G-G amides in hNotum participating in formation of the oxyanion hole is shown in yellow box. (TIF 31 KB)

Supplementary Table S1. List of PtPAEs and reference gene primers used for the qRT-PCR analysis. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S2. Motif sequences of PtPAEs predicted in P. trichocarpa using MEME tools. (DOCX 17 KB)

Supplementary Table S3. The secondary structures prediction of PtPAE based on the sequence proteins using NPSA. (DOCX 16 KB)

Supplementary Table S4. The amino acid similarity of the 10 PtPAEs was aligned using DNAMAN tools. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S5. Effect of nitrogen or carbon on transcript levels of PtPAEs in different tissues by qRT-PCR. (DOCX 23 KB)

Supplementary Table S6. Tissue-specific expression data of roots, stems, and leaves derived by RT-qPCR. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S7. GO annotation of the PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa using Blast2GO software. (DOCX 16 KB)

Supplementary Table S8. The template information for the tertiary structure prediction PtPAE proteins. (DOCX 17 KB)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science Fund Project of Heilongjiang Province of China (ZD2020C004), the Special Fund for Basic Scientific research operation Fee of Central University (2572019CT02), and the Innovation Project of State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding (Northeast Forestry University) (2019A03).

Author contributions

GL and CQ conceived and designed the study, CX performed most of the experiments, SZ JS and RC conducted the sampling, CY and XX performed bioinformatics calculations, JS and ZX processed and analyzed the data, and CX, CQ and GL wrote the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Chunpu Qu and Guanjun Liu have contributed to this work equally.

Contributor Information

Caifeng Xu, Email: xucaifeng0610@126.com.

Shuang Zhang, Email: zs18846795221@163.com.

Juanfang Suo, Email: 243672692@qq.com.

Ruhui Chang, Email: crh1107@126.com.

Xiuyue Xu, Email: 15663593162@163.com.

Zhiru Xu, Email: xuzhiru2003@126.com.

Chuanping Yang, Email: yangcp@nefu.edu.cn.

Chunpu Qu, Email: qcp_0451@163.com.

Guanjun Liu, Email: liuguanjun2003@126.com.

References

- Aerts R, van Logtestijn R, van Staalduinen M, Toet S. Nitrogen supply effects on productivity and potential leaf litter decay of Carex species from peatlands differing in nutrient limitation. Oecologia. 1995;104:447–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00341342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CT. We be jammin’: an update on pectin biosynthesis, trafficking and dynamics. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:495–502. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin E, Clavurier K. Pectin acetylesterases from Aspergillus are able to deacetylate homogalacturonan as well as rhamnogalacturonan. Carbohydr Polym. 2008;74:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SB, Mitra A, Baumgarten A, Young ND, May G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D233–238. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton FR, Suarez MF, Canovas FM. Molecular aspects of nitrogen mobilization and recycling in trees. Photosynth Res. 2005;83:265–278. doi: 10.1007/s11120-004-9366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr PD, Ollis DL. Alpha/beta hydrolase fold: an update. Protein Pept Lett. 2009;16(10):1137–1148. doi: 10.2174/092986609789071298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodriguez V, Garcia-Gutierrez A, Canales J, Canas RA, Kirby EG, Avila C, Canovas FM. Poplar trees for phytoremediation of high levels of nitrate and applications in bioenergy. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:299–312. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combet C, Blanchet C, Geourjon C, Deleage G, et al. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25(3):147–150. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M, et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza AJ, Pauly M. Comparative genomics of pectin acetylesterases: insight on function and biology. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10:e1055434. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1055434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza A, Hull PA, Gille S, Pauly M. Identification and functional characterization of the distinct plant pectin esterases PAE8 and PAE9 and their deletion mutants. Planta. 2014;240:1123–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2139-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euring D, Bai H, Janz D, Polle A. Nitrogen-driven stem elongation in poplar is linked with wood modification and gene clusters for stress, photosynthesis and cell wall formation. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:391. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0391-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Xin Z, Zheng ZL. The OSU1/QUA2/TSD2-encoded putative methyltransferase is a critical modulator of carbon and nitrogen nutrient balance response in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler-Lee J, et al. Poplar carbohydrate-active enzymes. Gene identification and expression analyses. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:946–962. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.072652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein DM, Shu S, Russell H, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;D1:D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou JY, Miller LM, Hou G, Yu XH, Chen XY, Liu CJ. Acetylesterase-mediated deacetylation of pectin impairs cell elongation, pollen germination, and plant reproduction. Plant Cell. 2012;24:50–65. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo AY, Zhu QH, Chen X, Luo JC. GSDS: a gene structure display server. Yi Chuan. 2007;29:1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heredia A, Jimenez A, Guillen R. Composition of plant cell walls. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1995;200:24–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01192903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist M. Alpha/beta-hydrolase fold enzymes: structures, functions an mechanisms. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1(2):209–235. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ileperuma NR, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of plant carboxylesterase AeCXE1, from Actinidia eriantha, and its complex with a high-affinity inhibitor paraoxon. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1851–1859. doi: 10.1021/bi062046w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakugawa S, et al. Notum deacylates Wnt proteins to suppress signalling activity. Nature. 2015;519:187–192. doi: 10.1038/nature14259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KW, Oh CY, Lee J-C, Lee S, Kim P-G. Alteration of leaf surface structures of poplars under elevated air temperature and carbon dioxide concentration. Appl Microscopy. 2013;43:110–116. doi: 10.9729/am.2013.43.3.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of a carbohydrate acetylesterase from Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiser T, Gras DE, Gutierrez AG, Gonzalez B, Gutierrez RA. A holistic view of nitrogen acquisition in plants. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:1455–1466. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzeslowska The cell wall in plant cell response to trace metals: polysaccharide remodeling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33(1):35–51. doi: 10.1007/s11738-010-0581-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng X, Wang H, Zhang S, Qu C, Yang C, Xu Z, Liu G. Identification and characterization of the APX gene family and its expression pattern under phytohormone treatment and abiotic stress in Populus trichocarpa. Genes (basel) 2021 doi: 10.3390/genes12030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, et al. Systematic analysis and functional validation of citrus pectin acetylesterases (CsPAEs) reveals that CsPAE2 negatively regulates citrus bacterial canker development. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21249429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Rennenberg H, Kreuzwieser J. Hypoxia affects nitrogen uptake and distribution in young poplar (Populus x canescens) trees. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. TMT-based quantitative proteomics analysis reveals the response of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) to fluoride. J Proteomics. 2018;176:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Bernard T, Rancurel C, et al. A hierarchical classification of polysaccharide lyases for glycogenomics. Biochem J. 2010;432:437–444. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, et al. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvet R, et al. Comprehensive expression profiling of the pectin methylesterase gene family during silique development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2006;224:782–791. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, et al. Competing endogenous RNA networks underlying anatomical and physiological characteristics of poplar wood in acclimation to low nitrogen availability. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019;60:2478–2495. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z-B, Langenfeld-Heyser R, Calfapietra C, Polle A. Influence of free air CO2 enrichment (EUROFACE) and nitrogen fertilisation on the anatomy of juvenile wood of three poplar species after coppicing. Trees. 2004;19:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00468-004-0369-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z-B, Calfapietra C, Liberloo M, Scarascia-Mugnozza G, Polle A. Carbon partitioning to mobile and structural fractions in poplar wood under elevated CO2 (EUROFACE) and N fertilization. Glob Chang Biol. 2006;12:272–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01091.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Li H, Liu T, Polle A, Peng C, Luo ZB. Nitrogen metabolism of two contrasting poplar species during acclimation to limiting nitrogen availability. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:4207–4224. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy TW, Der JP, Honaas LA, dePamphilis CW, Anderson CT. Phylogenetic analysis of pectin-related gene families in Physcomitrella patens and nine other plant species yields evolutionary insights into cell walls. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Hable W, Gottwald J, Ellard-Ivey M, Demura T, Lomax T, Carpita N. Connections: the hard wiring of the plant cell for perception, signaling, and response. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2105–2117. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Chai R, Dong H, Wang H, Tang C, Zhang Y. Effect of elevated CO2 on phosphorus nutrition of phosphate-deficient Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh under different nitrogen forms. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:355–367. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Stitt M. Metabolic and signaling aspects underpinning the regulation of plant carbon nitrogen interactions. Mol Plant. 2010;3:973–996. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obel N, Porchia AC, Scheller HV. Dynamic changes in cell wall polysaccharides during wheat seedling development. Phytochemistry. 2002;60:603–610. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollis DL, Eong C, Miroslaw C, et al. The α/β hydrolase fold. Protein Eng. 1992 doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren R, et al. Soil fertility limits carbon sequestration by forest ecosystems in a CO2-enriched atmosphere. Nature. 2001;411:469–472. doi: 10.1038/35078064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfila C, Dal Degan F, Jorgensen B, Scheller HV, Ray PM, Ulvskov P. Expression of mung bean pectin acetyl esterase in potato tubers: effect on acetylation of cell wall polymers and tuber mechanical properties. Planta. 2012;236:185–196. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1596-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe F, Pelloux J, Rayon C. Plant pectin acetylesterase structure and function: new insights from bioinformatic analysis. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:456. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3833-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitre FE, Cooke JEK, Mackay JJ. Short-term effects of nitrogen availability on wood formation and fibre properties in hybrid poplar. Trees Struct Funct. 2007;21:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s00468-007-0123-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pogorelko G, et al. Arabidopsis and Brachypodium distachyon transgenic plants expressing Aspergillus nidulans acetylesterases have decreased degree of polysaccharide acetylation and increased resistance to pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:9–23. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.214460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter SC, Luciani A, Eddy SR, Park Y, Lopez R, Finn RD. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W200–W204. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C, Hao B, Xu X, Wang Y, Yang C, Xu Z, Liu G. Functional research on three presumed asparagine synthetase family members in poplar. Genes (basel) 2019 doi: 10.3390/genes10050326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern OC, Dessailly BH, Dallman TJ, Sillitoe I, Orengo CA. FLORA: a novel method to predict protein function from structure in diverse superfamilies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahrawy M, Avila C, Chueca A, Canovas FM, Lopez-Gorge J. Increased sucrose level and altered nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana transgenic plants expressing antisense chloroplastic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:2495–2503. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller HV, Ulvskov P. Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:263–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senechal F, Wattier C, Rusterucci C, Pelloux J. Homogalacturonan-modifying enzymes: structure, expression, and roles in plants. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:5125–5160. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell. 1993;5:9–23. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson BD, Thorgeirsson H, Linder S. Growth and dry-matter partitioning of young Populus trichocarpa in response to carbon dioxide concentration and mineral nutrient availability. Tree Physiol. 2001;21:941–950. doi: 10.1093/treephys/21.12-13.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjodin A, Street NR, Sandberg G, Gustafsson P, Jansson S. The populus genome integrative explorer (PopGenIE): a new resource for exploring the Populus genome. New Phytol. 2009;182:1013–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313:1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanikova CE16 acetylesterases: in silico analysis, catalytic machinery prediction and comparison with related SGNH hydrolases. 3 Biotech. 2021;11:84. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02575-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbancic J, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Persson S. Carbon supply and the regulation of cell wall synthesis. Mol Plant. 2018;11:75–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, Hochstrasser DF. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;112:531–552. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profile analysis of CCH gene family in Populus. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3962. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. OsATX1 interacts with heavy metal P1B-type ATPases and affects copper transport and distribution. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:329–344. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZL. Carbon and nitrogen nutrient balance signaling in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:584–591. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.7.8540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig S1. GO analysis of the PtPAE genes, molecular function and biological process predicted by gene ontology. (TIF 84 KB)

Supplementary Fig S2. Relative expression level of PtPAE genes in roots, stems and leaves is shown by RT-qPCR. The 2-ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the transcription level of PtPAEs, and the log2 (sample/control) value of each PtPAE was used to show its relative expression level. In the heat map, the right side was a scale bar, and different colors indicated that the gene expression of the treated sample is up-regulated or down-regulated compared to the control. (TIF 14 KB)

Supplementary Fig. S3. Multiple sequences alignments between the amino acid sequence of PtPAE1 and a human palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase (4UYU_A). The catalytic triad in 4UYU is shown in red box; the canonical S-A and G-G amides in hNotum participating in formation of the oxyanion hole is shown in yellow box. (TIF 31 KB)

Supplementary Table S1. List of PtPAEs and reference gene primers used for the qRT-PCR analysis. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S2. Motif sequences of PtPAEs predicted in P. trichocarpa using MEME tools. (DOCX 17 KB)

Supplementary Table S3. The secondary structures prediction of PtPAE based on the sequence proteins using NPSA. (DOCX 16 KB)

Supplementary Table S4. The amino acid similarity of the 10 PtPAEs was aligned using DNAMAN tools. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S5. Effect of nitrogen or carbon on transcript levels of PtPAEs in different tissues by qRT-PCR. (DOCX 23 KB)

Supplementary Table S6. Tissue-specific expression data of roots, stems, and leaves derived by RT-qPCR. (DOCX 18 KB)

Supplementary Table S7. GO annotation of the PtPAEs in P. trichocarpa using Blast2GO software. (DOCX 16 KB)

Supplementary Table S8. The template information for the tertiary structure prediction PtPAE proteins. (DOCX 17 KB)