Abstract

A variety of species could be detected by using nanopores engineered with various recognition sites based upon non-covalent interactions, including electrostatic, aromatic, and hydrophobic interactions. The existence of these engineered non-covalent bonding sites was supported by the single-channel recording technique. The advantage of the non-covalent interaction-based sensing strategy was that the recognition site of the engineered nanopore was not specific for a particular molecule, but selective for a class of species (e.g., cationic, anionic, aromatic, and hydrophobic). Since different species produce current modulations with quite different signatures represented by amplitude, residence time, and even characteristic voltage dependence curve, the non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensor could not only differentiate individual molecules in the same category, but also enable discriminating between species with similar structures or molecular weights. Hence, our developed non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensing strategy may find useful application in detection of molecules of medical and environmental importance.

Keywords: Nanopore, Non-covalent interactions, Molecular recognition, Stochastic sensing, Peptides

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The molecular recognition process, one of the most fundamental processes in chemistry and biology, is very complicated and influenced by many factors.1,2 These factors, also called non-covalent interactions, include electrostatic interaction,3 aromatic-aromatic interaction,4,5 hydrophobic interaction,6 and hydrogen bond.7 Accordingly, in terms of ligand-receptor interactions, the design strategies generally involve the manipulation of hydrophobic, polar, and charged residues.8 Although non-covalent interactions are relatively weak, they play important roles in protein folding and unfolding, and are critical to the stability of protein structures.5,9,10

The ideal molecular recognition should have large binding affinity and high selectivity, which is exemplified by enzyme-substrate binding and antigen-antibody recognition.11 However, in terms of sensor application, although the advantage of high selectivity is obvious, the development of such a sensing system is time-consuming and sometimes is very difficult or even impossible to achieve. Furthermore, since this kind of sensing approach is highly specific for a certain target molecule, a variety of different sensing systems must be developed in order to detect different species. In this work, we reported a new generic approach to molecule analyses using nanopore stochastic sensing,12 in which nanopore sensors are engineered with weak non-covalent interaction recognition sites. In our strategy, the sensor is not specific for a target molecule, but selective for a group of compounds, instead.

Nanopore stochastic sensing is a label-free technique for measuring single molecules, which works by monitoring ionic current modulations produced by the passage of analyte molecules through a single nanopore.13,14 In addition to DNA sequencing,15,16 nanopore technology has been utilized as a versatile tool to explore various other applications, including study of biomolecular folding/unfolding,17,18 investigation of enzyme activity and kinetics,19,20,21 and biosensing of a variety of species.22,23,24 In Bayley and co-workers’ pioneering work, β-cyclodextrin (βCD) was introduced into the α-hemolysin protein pore as a molecular adapter, which could recognize a number of organic compounds through host-guest interaction.25 Their follow-up studies showed that βCD bound to the mutant α-hemolysin (M113N)7 pore hundreds fold more tightly than the wild-type α-hemolysin protein due to hydrogen bond.26,27 In this work, we focused on other non-covalent interactions including electrostatic, aromatic, and hydrophobic interactions. Briefly, we developed a systematic method to introduce a variety of recognition sites into the α-hemolysin nanopores so that they could recognize cations, anions, aromatic, and hydrophobic molecules. Our sensing strategy overcomes the restrictive constraints of specificity for a given receptor/analyte sensor system.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents

Peptides D-D-D-D-D-D (D6), D-D-D-D-D (D5), Y-Y-Y-Y-Y (Y6), Endomorphin-1 (sequence: Y-P-W-F), Endomorphin-2 (sequence: Y-P-F-F), and R-K-R-A-R-K-E were purchased from American Peptide Company, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Peptides cyclo(Pro-Gly)3 and Tyr-Phe-Phe amide were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All these peptides were dissolved in HPLC grade water, and the concentrations of the stock solutions were 1 mg/mL each. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Preparation and formation of protein pore

Mutant αHL genes were constructed by cassette mutagenesis with a previously remodeled gene in a T7 vector (pT7-αHL-RL2).28 Wild-type αHL and mutant αHL monomers were first synthesized by coupled in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT) using the E. Coli T7 S30 Extract System for Circular DNA from Promega (Madison, WI). And then, they were assembled into homoheptamers by adding rabbit red cell membranes and incubating for 1 h.29 The heptamers were purified by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

2.3. Single-Channel Recording and Data Analysis

A bilayer of 1,2-diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids; Alabaster, AL) was formed on an aperture of 120 μm in a 25 μm-thick Teflon septum (Goodfellow; Malvern, PA) that separated a planar bilayer chamber into two compartments, i.e., cis and trans (cis at ground). Each compartment contained 1.5 mL buffer solution, which consisted of 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The α-HL protein was added to the cis compartment and its final concentration was 0.2–2.0 ng·mL−1. The applied potential and which compartment (cis or trans) that the analytes were added to were described as shown in the corresponding figure legend. Currents were recorded with a patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Axon Instruments; Foster City, CA), low-pass filtered with a built-in 4-pole Bessel filter at 5 kHz, and sampled at 20 kHz by a computer equipped with a Digidata 1200 A/D converter (Axon Instruments). Data were analyzed with Clampfit 9.0 (Axon Instruments). For the determination of kinetic constants, three separate experiments were performed for each case, and data were acquired for at least 2 min in each experiment. Kinetic constants were calculated by using the following equations: kon = 1/(Cτon), koff = 1/τoff, Kf = kon/koff, and ΔG = −RTln(Kf), where R is molar gas constant, T is temperature in kelvin, τoff is event duration, τon is inter-event interval, and C is the concentration of the target compound. It should be noted that the beta-barrel entrance of the α-HL pore is negatively charged at neutral pH, and this charge would influence the peptide (especially charged) trafficking across the nanopore.30 In our study, peptide analytes were added either to the trans or to the cis compartment, and the applied potential bias was either positive or negative. To simplify our investigation, the reported values of τoff, kon, and ΔG were obtained without considering the charge effect of the α-HL beta-barrel entrance. Furthermore, kon values were not corrected for electrophoretic/electroosmotic mediated increase in the reaction association rate.31

2.4. Molecular Modeling and Graphics

Modeling of the WT α-HL protein was based on the wild-type α-HL pore (Protein Data Bank: 7αHL.pdb)29 using SPOCK 6.3.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Introduction of various non-covalent bonding sites to the α-HL protein pores.

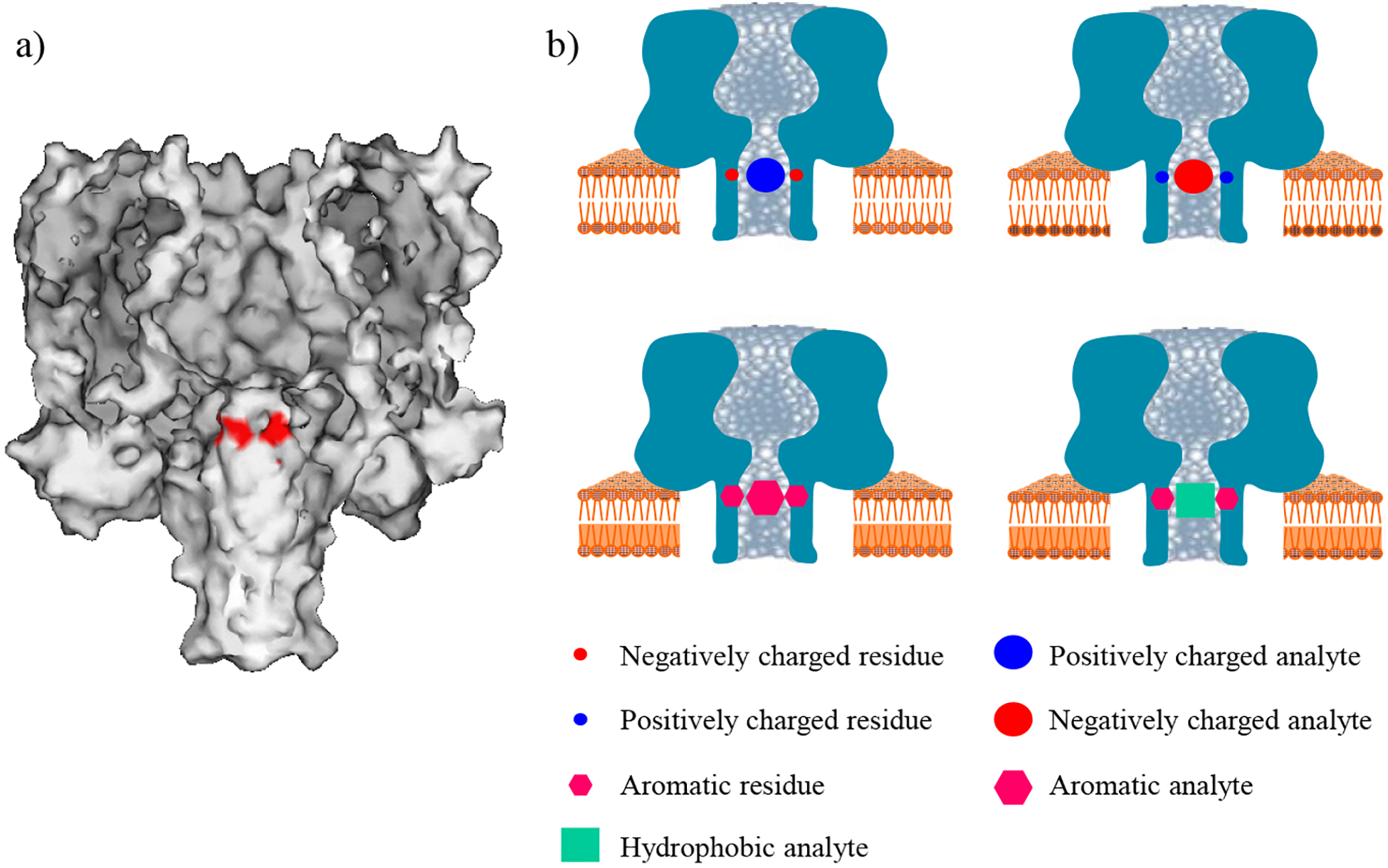

The basic principle for the construction of non-covalent bonding recognition sites was to engineer wild-type α-HL protein with new functional groups. For example, for the detection of anionic molecules, the hydrophobic amino-acid residues of the wild-type α-HL could be mutated to positively charged residues and to create an environment full of positive charge density, thus permitting to attract negatively charged compounds by electrostatic interactions. Similarly, for the detection of cationic compounds, the hydrophobic amino-acid residues could be mutated to negatively charged residues to create an electrostatic interaction site, while for the detection of aromatic / hydrophobic molecules, the hydrophobic amino-acid residues of the protein pore could be mutated to aromatic residues to create an aromatic-aromatic interaction site, and an aromatic-hydrophobic (or general hydrophobic) interaction site, respectively. In this work, by mutating the methionine residue of the wild-type α-HL protein at position 113, a series of homoheptamer mutants were constructed and imparted with the capability to recognize cationic, anionic, aromatic, and hydrophobic molecules based on electrostatic, aromatic-aromatic, cation-π, and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 1). Note that the β-barrel of the α-HL protein pore has three sensing regions/zones, including the primary (close to the narrowest constriction of the nanopore), secondary (near position 135), and trans-opening.32,33 Position 113 is located in the primary sensing zone, and is most widely utilized to design engineered nanopores for various applications.26,34,35,36,37

Figure 1.

a) Molecular graphics representation of the wild-type protein homoheptameric pore, showing the mutation site (in red) in this work; and b) schematic representation of the principle of the non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensing strategy.

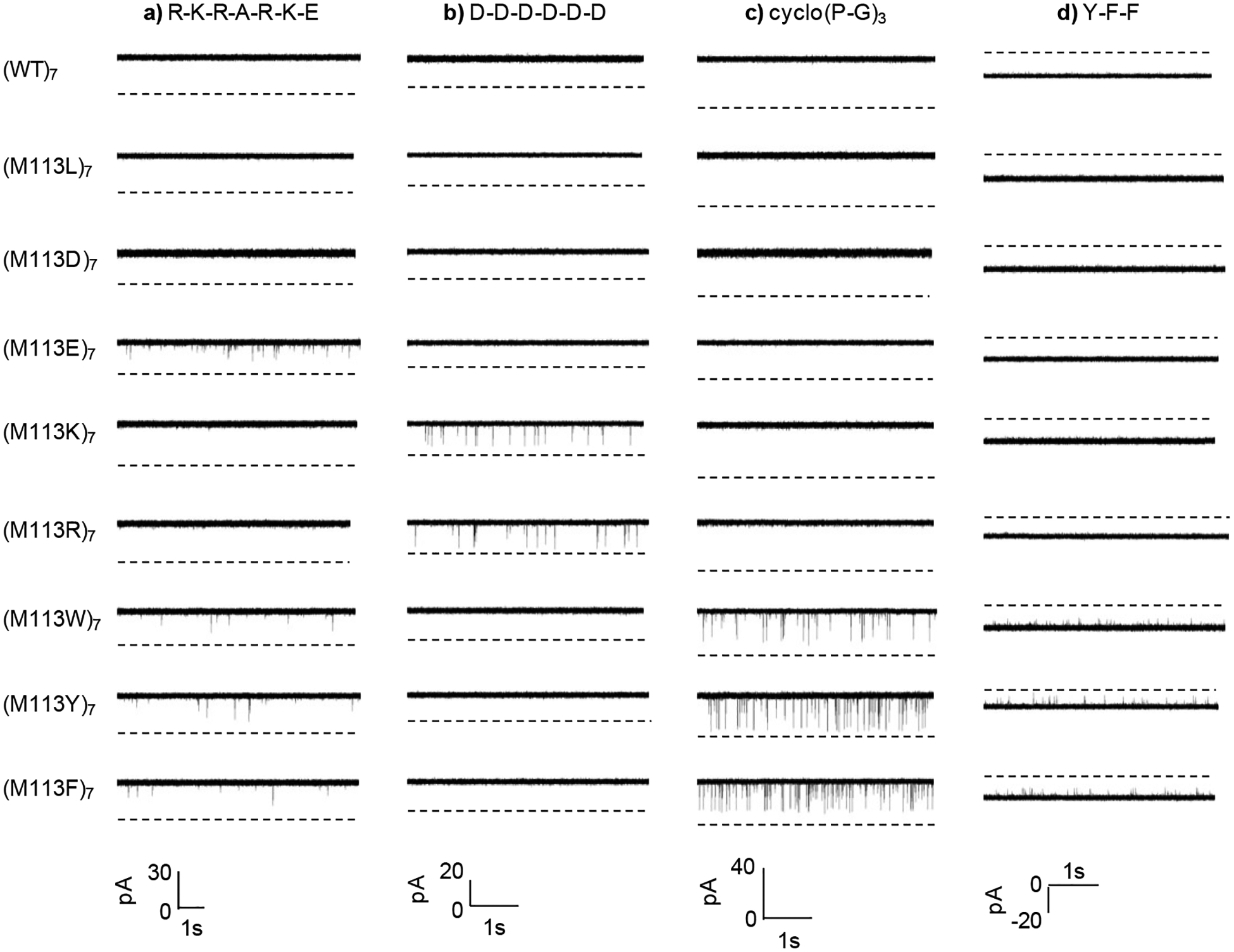

To demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing these engineered non-covalent interaction recognition sites for detection of negatively charged, positively charged, aromatic, and hydrophobic molecules, four series of cross-check single-channel recording experiments were performed, where the interactions between nine α-HL pores and four analyte species were examined. To be more specific, the amino acid residues in the nine protein pores used belonged to four major classes: hydrophobic (methionine, and leucine), negatively charged (aspartic acid, and glutamic acid), positively charged (arginine, and lysine), and aromatic (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), while the analytes also included the same four categories, i.e., hydrophobic (peptide cyclo(Pro-Gly)3), negatively charged (peptide D-D-D-D-D-D), positively charged (peptide R-K-R-A-R-K-E), and aromatic (peptide F-Y-Y) molecules. Since the peptide analytes were very short (only containing 3 to 7 amino acids) and they were also confined inside the nanopore during the translocation, these biomolecules were not expected to have secondary structures.30 Therefore, the peptides used in this study were estimated to be ~1.2 to ~2.8 nm long and had diameters ranging from ~ 0.4 to ~1.0 nm, which is comparable with the nanopore constriction (~1.4 nm diameter).29 These estimated values were obtained according to the contour length of 0.4 nm per amino acid and the size of the amino acid, respectively.38,39 Our experiments (Figure 2) showed that, for aromatic compounds (peptide F-Y-Y), current blocking events were identified only with three aromatic M113 mutants (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), which supports the hypothesis that the binding events arise from the aromatic-aromatic interaction. As to the anionic compound (peptide D-D-D-D-D-D), hydrophobic molecule (peptide cyclo(pro-gly)3), and positively charged analyte (peptide R-K-R-A-R-K-E), current modulation signals were observed only with two positively charged M113 mutants (arginine, and lysine), three aromatic M113 mutants (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), and one negatively charged and three aromatic M113 mutants (glutamic acid, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), respectively, which provided evidence that the events are caused by electrostatic interaction, general hydrophobic interaction, and electrostatic as well as cation-pi interactions, respectively.40 The electrostatic interaction was not observed with the addition of R-K-R-A-R-K-E to the (M113D)7 α-HL pore, which might be attributed to the steric effect of the neighboring side chains on the designed non-covalent bonding site (i.e., the amino-acid Asp) of the mutant pore. For example, it was possible that the small negatively charged Asp side chains were hidden by their neighboring large amino-acid residues and thus could not interact with the positively charged molecules that entered the protein pore. Further data analysis (Table 1) showed that the reaction free energies (ΔG) for the experimental electrostatic, aromatic-aromatic, and general hydrophobic interactions were in the range of from −6.96 kJ mol−1 to −27.99 kJ mol−1, from – 16.28 kJ mol−1 to −29.33 kJ mol−1, and from – 10.42 kJ mol−1 to −12.84 kJ mol−1, respectively. These values were in agreement with the other reported results.41 It should be mentioned that, the electrostatic interaction between D-D-D-D-D-D and the (M113K)7 / (M113R)7 pore we demonstrated here was not due to the electrophoresis effect, since when the negatively charged peptide D-D-D-D-D-D was added to the cis compartment, current blocking events were identified not only with an applied positive potential, but also with a low negative potential. Furthermore, the failure of D-D-D-D-D-D to bind other three classes of α-HL pores also argued against the electrophoresis effect and the size effect of the nanopore. In the latter case (i.e., if our findings were due to the size effect), the translocation of D-D-D-D-D-D in the (M113F)7, (M113Y)7, and (M113W)7 pores should produce observable current modulation events since phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan residues have similar (or slightly larger) van der Waals volumes to those of lysine and arginine side chains.42 It should also be noted that, in those four series of single channel recording experiments, proteins were added to the cis compartment of the chamber, while the peptides were added either to the trans or to the cis compartment, and the applied voltage were either positive or negative. The choice of the trans or cis where the peptides were added and the positive or negative potential applied depends on several factors, e.g., the obtained event frequency and residence time. Usually, the analytes were added to the trans compartment, while a positive potential was applied. In the aromatic-aromatic interaction reported in this work, current blocking events could be observed when peptide F-Y-Y was added in either the cis or trans compartment, and with either a positive or a negative potential applied. More events were observed when peptide Y-F-F was added in the trans compartment of the chamber under a negatively applied potential bias. However, on the other hand, take the negatively charged peptide D-D-D-D-D-D for example, if it was added in the trans, an applied positive potential will prevent the peptide entering the pore, and therefore, it is difficult to observe the peptide’s interaction with the engineered receptor.

Figure 2.

Typical single-channel recording trace segments, demonstrating the non-covalent interactions observed in stochastic studies of the translocation of various peptide molecules through pores of wild-type and mutant alpha-hemolysin proteins. All the experiments were performed in an electrolyte solution containing 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.5), with α-HL protein pores added in the cis compartment of the chamber. In the series of experiments with cationic peptide R-K-R-A-R-K-E (20 μM), which was added in the trans chamber compartment, the applied potential was +40 mV (cis at ground); in the experiments with anionic peptide D-D-D-D-D-D (which was added in the cis compartment of the chamber), a positive +30 mV (cis at ground) voltage was applied. In the traces of (M113R)7 and (M113K)7, the final concentration of D-D-D-D-D-D was 1.41 μM, while 30 μM D-D-D-D-D-D was added in other protein pores; in the case of hydrophobic peptide cyclo(pro-gly)3 (21.5 μM), which was added in the trans chamber compartment, the voltage was +50 mV (cis at ground); and with aromatic peptide Y-F-F, (which was added in the trans comparment of the chamber), the experiments were performed at −25 mV (cis at ground). In the traces of (M113F)7, (M113W)7, and (M113Y)7, the final concentration of Y-F-F was 1 μM, while 10 μM Y-F-F was added in the traces of other protein pores.

Table 1.

Experimental results of non-covalent bonding interaction free energy*

| Interaction Type | Protein | Analyte | τoff (ms) | kon (s−1M−1) | ΔG (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | (M113R)7 | D-D-D-D-D-D | 0.371 | 2.55×106 | −16.78 |

| (M113K)7 | D-D-D-D-D-D | 0.475 | 3.69×106 | −18.33 | |

| (M113E)7 | R-K-R-A-R-K-E | 0.191 | 8.95×104 | −6.95 | |

| (M113RT145R)7 | D-D-D-D-D-D | 16.0 | 5.71×106 | −27.99 | |

| (M113RG143R)7 | D-D-D-D-D-D | 2.94 | 3.88×106 | −22.89 | |

| Aromatic | (M113F)7 | Y-F-F | 0.231 | 3.29×106 | −16.28 |

| (M113W)7 | Y-F-F | 0.270 | 4.86×106 | −17.61 | |

| (M113Y)7 | Y-F-F | 0.258 | 4.79×106 | −17.48 | |

| (M113Y)7 | Y-Y-Y-Y-Y-Y | 57.6 | 2.75×106 | −29.33 | |

| Hydrophobic | (M113F)7 | Cyclo(Pro-Gly)3 | 0.406 | 1.71×105 | −10.42 |

| (M113W)7 | Cyclo(Pro-Gly)3 | 0.647 | 2.86×105 | −12.80 | |

| (M113Y)7 | Cyclo(Pro-Gly)3 | 0.406 | 4.63×105 | −12.84 |

All the relative errors are less than 10%.

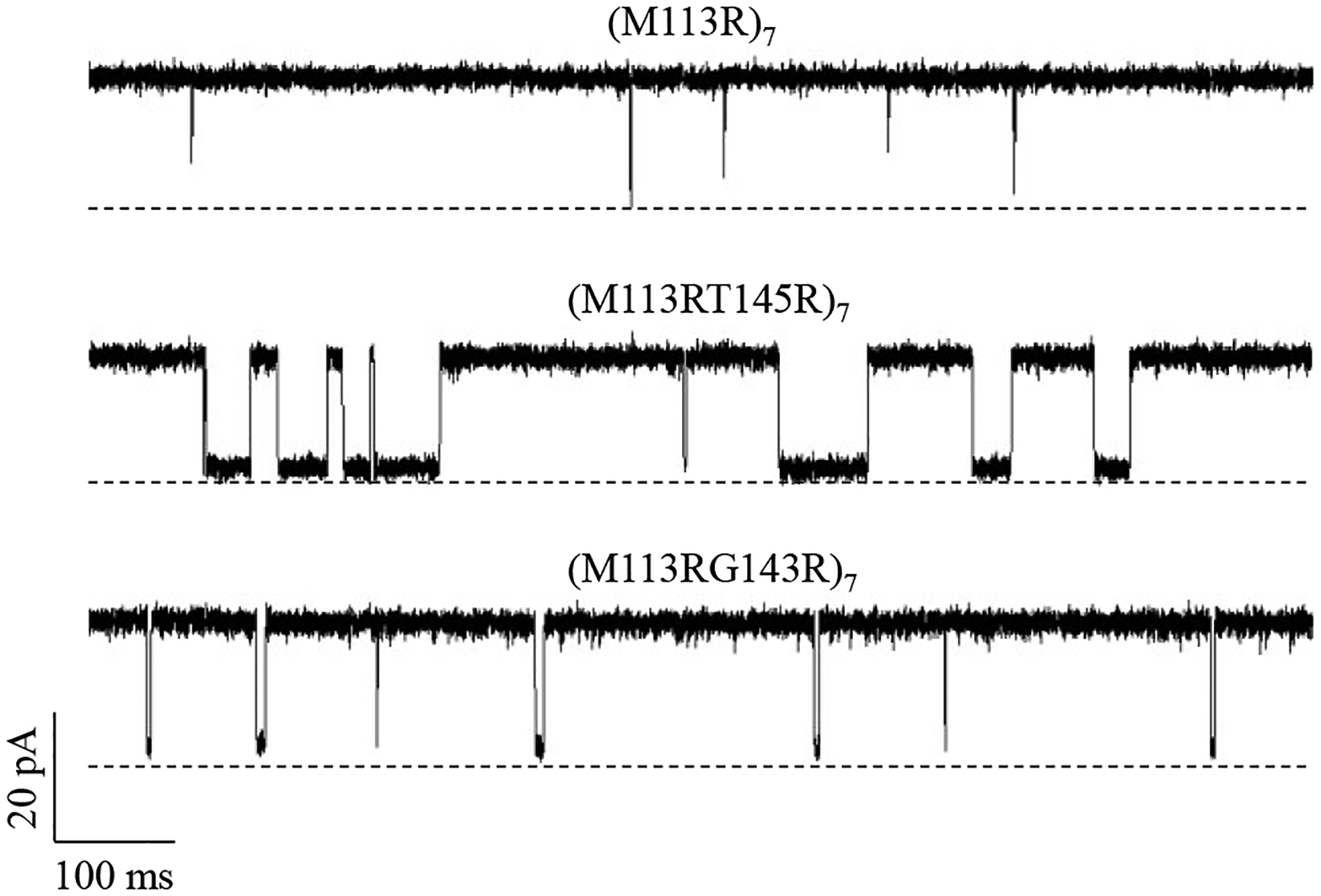

The experiments with two additional double mutant homoheptamer proteins, (M113RT145R)7 and (M113RG143R)7, provide further evidence that the nature of protein pore-analyte interaction is attributed to the non-covalent bonding interactions. Compared with the single mutant protein (M113R)7, these two double mutants contained seven more positively charged arginine residues, thus having higher positive charge density. Furthermore, our molecular modeling of the two double mutants demonstrated that (M113RT145R)7 had higher positive charge density than (M113RG143R)7. Therefore, it could be expected that the order of the affinity for D-D-D-D-D-D’s binding to these pores will be (M113R)7 < (M113RG143R)7 < (M113RT145R)7 if the binding events arise from electrostatic interactions. This order was confirmed by our experimental results (Figure 3 and Table 1), where the event residence time (τoff) values were 0.37 ms, 2.94 ms, and 16.0 ms, while the formation constants (Kf) were 946 M−1, 1.14×104 M−1, and 9.14×104 M−1 for D-D-D-D-D-D’s binding to the three pores (M113R)7, (M113RG143R)7, and (M113RT145R)7, respectively. This suggests a 12-fold, and 97-fold increase in the binding affinity with the two double mutants than that with the (M113R)7 pore. Our results were very similar to those reported by Bayley and co-workers in their study with 1,4,5-Trisphosphate (IP3),43 where IP3 bound to (M113RG143R)7 and (M113RT145R)7 proteins approximately 10- and 100-fold stronger than (M113R)7.

Figure 3.

Single-channel recordings of anionic peptides D-D-D-D-D-D in α-hemolysin mutant protein homoheptamer pores (M113RT145R)7, (M113RT145R)7, and (M113R)7, supporting the electrostatic interaction nature, and also suggesting that the sensitivity of the non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensor could be improved significantly by introducing multiple functional groups to the nanopore. The experiments were performed at +30 mV (cis at ground) in an electrolyte solution containing 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.5). Both the α-HL protein and anionic peptide D-D-D-D-D-D (1.4 μM) were added in the cis compartment of the sensing chamber.

3.2. Application of non-covalent bonding interactions.

Unlike the specific recognition approach, where only one or only a few compounds could be detected by a single engineered nanopore, our developed weak non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensor has selectivity toward a class of compounds based on charge, aromaticity, and hydrophobicity. Thus, our approach can serve as a generic sensing technique for a wide variety of molecules. Take the (M113E)7 pore with the cationic recognition site for example, it can identify only the cationic molecules through the electrostatic interaction, but not anionic, aromatic, or hydrophobic compounds. It should be mentioned that there might be some misconception about the viability of this non-covalent interaction strategy in practical sensor application since it is possible for many analytes to interact with the binding site of the nanopore. To address this issue, several other compounds were tested with the (M113E)7 pore, including L-arginine, L-lysine, spermidine, and spermine. Our experiments showed that there were no current blocking events when L-arginine, L-lysine, or spermidine was added to the (M113E)7 pore. Only a few events were observed with spermine. This suggests that not all the cationic compounds could bind to the recognition site and thus induce signals, since for a given protein channel, current modulations are dependent on the pore size, the structure and the size of the analyte, as well as the affinity of the analyte’s binding to the recognition site of the pore. In addition, even if two or more molecules could bind to the same recognition site of the pore, they could be conveniently differentiated given that each analyte has its unique signature represented by amplitude, residence time, and even characteristic voltage dependence curve. Therefore, one of the advantages of the non-covalent bonding approach is its capability to permit the simultaneous identification and quantification of a number of similar compounds (e.g., in terms of charge, aromaticity, structure, and molecular weight), which will be discussed in detail below.

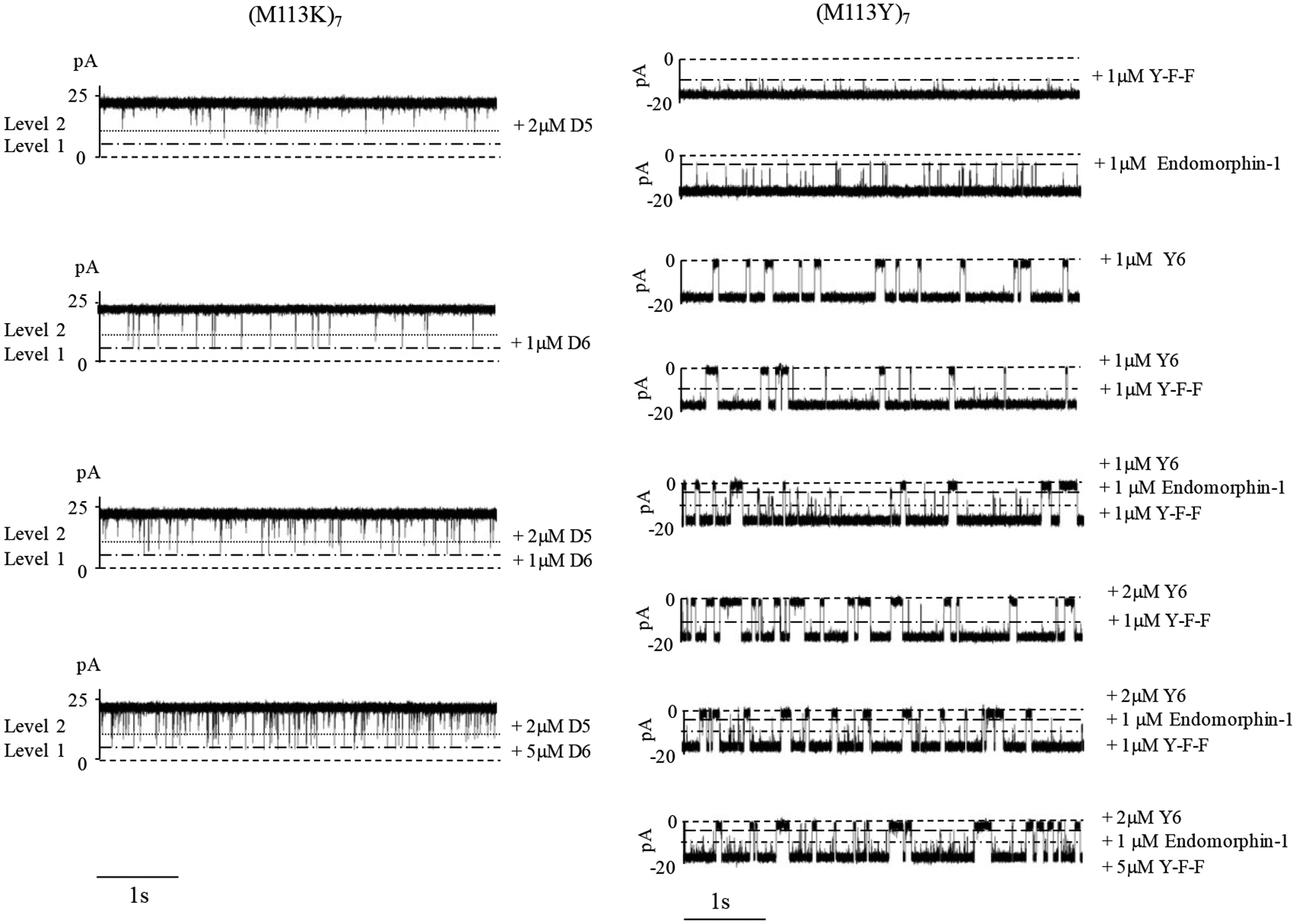

3.3. Simultaneous identification and quantification of a mixture of analytes.

Figure 4 showed that a mixture of two negatively charged peptides and a mixture of three aromatic peptides could be differentiated through different amplitudes and/or residence time values of the binding events. Briefly, with the (M113K)7 pore, it was found that peptide D-D-D-D-D-D produced current blocking events with about 75% of full channel block, while the events of peptide D-D-D-D-D showed around 50% of full channel block. Thus, two quite different signals could be easily identified in a mixture solution containing peptides D-D-D-D-D-D and D-D-D-D-D. As to aromatic compounds, peptides F-Y-Y, endomorphin-1 (Y-P-W-F), and Y-Y-Y-Y-Y-Y had three quite different signals when they bound to (M113Y)7. Their binding events were at 40%, 75%, and 90% of full channel block, respectively. In addition, it was found that in both the cases, with an increase in the concentration of the added target analyte, the event frequency increased linearly even in the presence of other species. This suggested that the target analyte could be differentiated against other compounds present in the solution, and its concentration could be also quantified. Furthermore, the simultaneous detection of a mixture of two or even three compounds could be achieved by using a single pore engineered with a non-covalent bonding site.

Figure 4.

Simultaneous detection of multiple analytes. (Left) Typical single-channel recording trace segments, showing different binding behaviors of α-hemolysin mutant protein homoheptamer (M113K)7 pore with anionic peptides D-D-D-D-D-D (D6) and D-D-D-D-D (D5). The experiments were performed at +30 mV (cis at ground) in an electrolyte solution containing 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.5). Both the α-HL protein and anionic peptides D6 and/or D5 were added in the cis chamber compartment. (Right) Typical single-channel recording trace segments, showing different binding behaviors of α-hemolysin mutant protein homoheptamer (M113Y)7 pore with peptides F-Y-F, endomorphin-1 (Y-P-W-F), and Y-Y-Y-Y-Y-Y (Y6). The experiments were performed at −25 mV (cis at ground) in an electrolyte solution containing 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.5). The α-HL protein was added in the cis compartment, while peptides Y-F-F, endomorphin-1, and/or Y6 were added in the trans compartment of the chamber device.

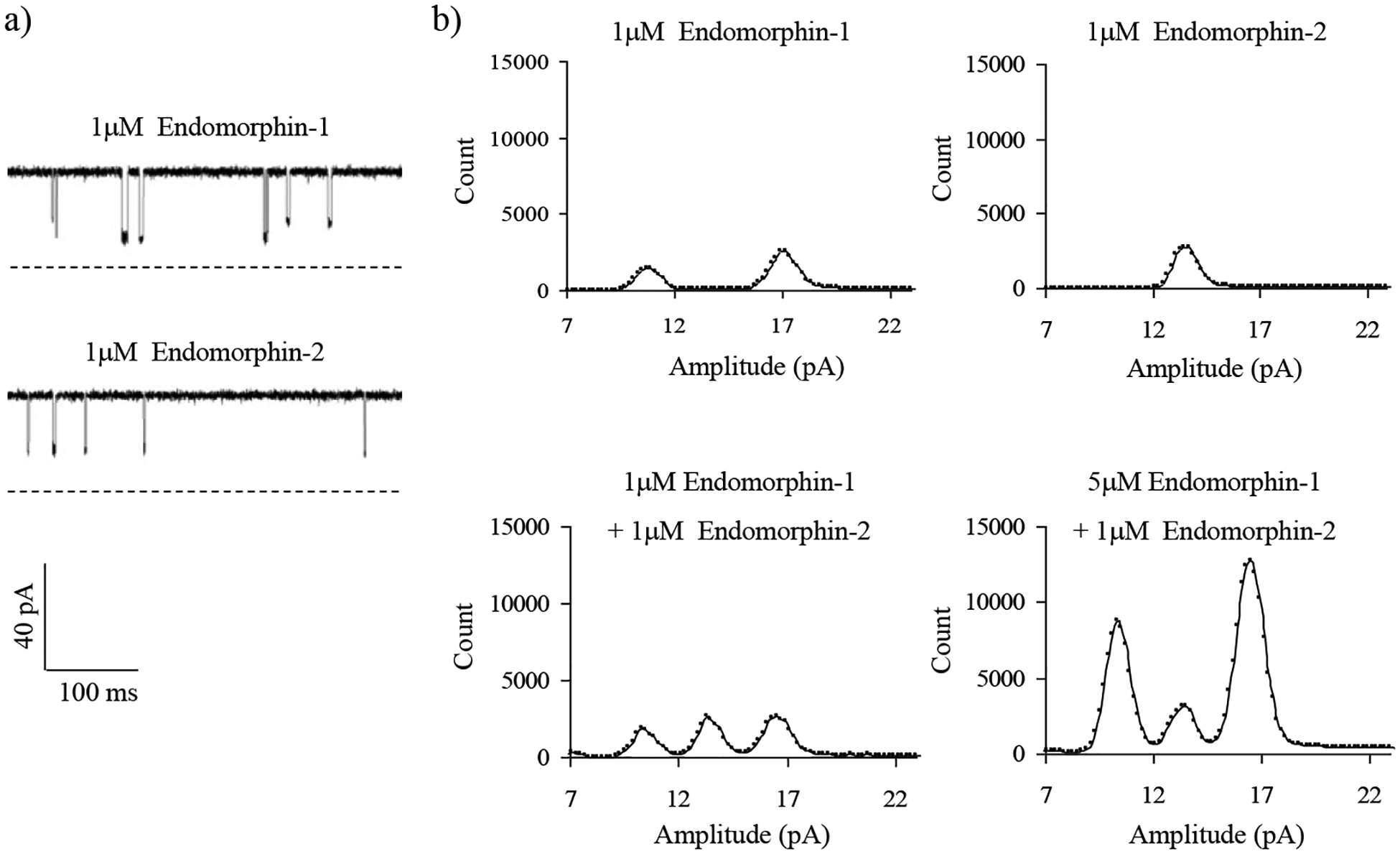

In addition to the detection of the compounds belonging to a same category (e.g., charge, and aromaticity), other significant application of our developed non-covalent bonding sensing strategy includes differentiation of analytes with similar structure and even almost identical molecular weight. As one of such examples, endomorphine-1 (peptide sequence: Y-P-W-F) and endomorphine-2 (sequence: Y-P-F-F) have very similar structure and sequence, which only differ by one amino acid (i.e., the third amino-acid in the sequence is W for endomorphin-1, instead of F for endomorphin-2). However, the subtle difference in the structures of these two peptides resulted in the production of current blockage events with significant different signatures (i.e., amplitudes and residence time values), allowing them readily differentiated and even simultaneously quantitated (see Figure 5). On the other hand, although peptides Y-P-W-F (with molecular weight of 610.7) and F-F-G-L-M (with molecular weight of 612.9) had almost identical molecular weights, they could be discriminated and concurrently measured based on their unique blockage amplitude signatures (Supporting Information, Fig. S1).

Figure 5.

a) Single-channel recordings and b) all points histograms, showing different binding behaviors of α-hemolysin mutant protein homoheptamer (M113Y)7 pore with peptides endomorphin-1 (Y-P-W-F) and endomorphin-2 (Y-P-F-F). The experiments were performed at +50 mV (cis at ground) in an electrolyte solution containing 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.5). The α-HL protein was added in the cis chamber compartment, while peptides endomorphin-1, and/or endomorphin-2 were added in the trans compartment of the sensing chamber.

4. Conclusion

In summary, by introducing non-covalent bonding recognition sites in the nanopore, a variety of species can be detected based on their characteristic event signatures (e.g., amplitude, and residence time) in the nanopore. The presence of other compounds in the sample solution would not interfere with the detection of the target analyte as long as the nanopore sensor can provide sufficient resolution. Since the concentration of the target analyte could linearly be related to the event frequency, the concentration of the analyte molecules could also be quantified (Supporting Information, Fig. S2). Therefore, our developed non-covalent interaction-based nanopore sensing strategy may find useful sensor application in detection of molecules of medical and environmental importance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully thank National Institutes of Health (2R15GM110632-02), National Science Foundation (1708596) for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Additional figures, including all-points histograms showing differentiation and simultaneous detection of two peptides having almost the same molecular weight, and calibration curve for peptide D-D-D-D-D-D.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hunter CA; Lawson KR; Perkins J; Urch CJ Aromatic Interactions. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2 2001, No. 5, 651–669. 10.1039/b008495f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Leckband D Measuring the Forces That Control Protein Interactions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 2000, 29, 1–26. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Syed A; Battula H; Mishra S; Jayanty S Distinct Tetracyanoquinodimethane Derivatives: Enhanced Fluorescence in Solutions and Unprecedented Cation Recognition in the Solid State. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (4), 3090–3105. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Lanzarotti E; Defelipe LA; Marti MA; Turjanski AG Aromatic Clusters in Protein-Protein and Protein-Drug Complexes. J Cheminform 2020, 12 (1), 30. 10.1186/s13321-020-00437-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rashkin MJ; Waters ML Unexpected Substituent Effects in Offset Pi-Pi Stacked Interactions in Water. J Am Chem Soc 2002, 124 (9), 1860–1861. 10.1021/ja016508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mateos B; Holzinger J; Conrad-Billroth C; Platzer G; Żerko S; Sealey-Cardona M; Anrather D; Koźmiński W; Konrat R Hyperphosphorylation of Human Osteopontin and Its Impact on Structural Dynamics and Molecular Recognition. Biochemistry 2021. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lin Y; Sun J; Tang M; Zhang G; Yu L; Zhao X; Ai R; Yu H; Shao B; He Y Synergistic Recognition-Triggered Charge Transfer Enables Rapid Visual Colorimetric Detection of Fentanyl. Anal Chem 2021, 93 (16), 6544–6550. 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Escobar L; Ballester P Molecular Recognition in Water Using Macrocyclic Synthetic Receptors. Chem Rev 2021, 121 (4), 2445–2514. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Osipiuk J; Azizi S-A; Dvorkin S; Endres M; Jedrzejczak R; Jones KA; Kang S; Kathayat RS; Kim Y; Lisnyak VG; Maki SL; Nicolaescu V; Taylor CA; Tesar C; Zhang Y-A; Zhou Z; Randall G; Michalska K; Snyder SA; Dickinson BC; Joachimiak A Structure of Papain-like Protease from SARS-CoV-2 and Its Complexes with Non-Covalent Inhibitors. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 743. 10.1038/s41467-021-21060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sepay N; Saha PC; Shahzadi Z; Chakraborty A; Halder UC A Crystallography-Based Investigation of Weak Interactions for Drug Design against COVID-19. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2021, 23 (12), 7261–7270. 10.1039/d0cp05714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Houk KN; Leach AG; Kim SP; Zhang X Binding Affinities of Host-Guest, Protein-Ligand, and Protein-Transition-State Complexes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2003, 42 (40), 4872–4897. 10.1002/anie.200200565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bayley H; Cremer PS Stochastic Sensors Inspired by Biology. Nature 2001, 413 (6852), 226–230. 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Roozbahani GM; Chen X; Zhang Y; Wang L; Guan X Nanopore Detection of Metal Ions: Current Status and Future Directions. Small Methods 2020, 4 (10). 10.1002/smtd.202000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang Y; Zhang Y; Chen X; Guan X; Wang L Analysis with Biological Nanopore: On-Pore, off-Pore Strategies and Application in Biological Fluids. Talanta 2021, 223 (Pt 1), 121684. 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Deamer D; Akeson M; Branton D Three Decades of Nanopore Sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2016, 34 (5), 518–524. 10.1038/nbt.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sethi K; Dailey GP; Zahid OK; Taylor EW; Ruzicka JA; Hall AR Direct Detection of Conserved Viral Sequences and Other Nucleic Acid Motifs with Solid-State Nanopores. ACS Nano 2021. 10.1021/acsnano.0c10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Si W; Aksimentiev A Nanopore Sensing of Protein Folding. ACS Nano 2017, 11 (7), 7091–7100. 10.1021/acsnano.7b02718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tripathi P; Benabbas A; Mehrafrooz B; Yamazaki H; Aksimentiev A; Champion PM; Wanunu M Electrical Unfolding of Cytochrome c during Translocation through a Nanopore Constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118 (17). 10.1073/pnas.2016262118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chen X; Zhang Y; Roozbahani GM; Guan X Salt-Mediated Nanopore Detection of ADAM-17. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2019, 2 (1), 504–509. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Li M; Rauf A; Guo Y; Kang X Real-Time Label-Free Kinetics Monitoring of Trypsin-Catalyzed Ester Hydrolysis by a Nanopore Sensor. ACS Sens 2019, 4 (11), 2854–2857. 10.1021/acssensors.9b01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pham B; Eron SJ; Hill ME; Li X; Fahie MA; Hardy JA; Chen M A Nanopore Approach for Analysis of Caspase-7 Activity in Cell Lysates. Biophys J 2019, 117 (5), 844–855. 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Asandei A; Mereuta L; Park J; Seo CH; Park Y; Luchian T Nonfunctionalized PNAs as Beacons for Nucleic Acid Detection in a Nanopore System. ACS Sens 2019, 4 (6), 1502–1507. 10.1021/acssensors.9b00553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhang Y; Chen X; Wang C; Roozbahani GM; Chang H-C; Guan X Chemically Functionalized Conical PET Nanopore for Protein Detection at the Single-Molecule Level. Biosens Bioelectron 2020, 165, 112289. 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yu R-J; Xu S-W; Paul S; Ying Y-L; Cui L-F; Daiguji H; Hsu W-L; Long Y-T Nanoconfined Electrochemical Sensing of Single Silver Nanoparticles with a Wireless Nanopore Electrode. ACS Sens 2021, 6 (2), 335–339. 10.1021/acssensors.0c02327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gu LQ; Braha O; Conlan S; Cheley S; Bayley H Stochastic Sensing of Organic Analytes by a Pore-Forming Protein Containing a Molecular Adapter. Nature 1999, 398 (6729), 686–690. 10.1038/19491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gu LQ; Cheley S; Bayley H Prolonged Residence Time of a Noncovalent Molecular Adapter, Beta-Cyclodextrin, within the Lumen of Mutant Alpha-Hemolysin Pores. J Gen Physiol 2001, 118 (5), 481–494. 10.1085/jgp.118.5.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Li W-W; Claridge TDW; Li Q; Wormald MR; Davis BG; Bayley H Tuning the Cavity of Cyclodextrins: Altered Sugar Adaptors in Protein Pores. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133 (6), 1987–2001. 10.1021/ja1100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Cheley S; Braha O; Lu X; Conlan S; Bayley H A Functional Protein Pore with a “Retro” Transmembrane Domain. Protein Sci 1999, 8 (6), 1257–1267. 10.1110/ps.8.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Song L; Hobaugh MR; Shustak C; Cheley S; Bayley H; Gouaux JE Structure of Staphylococcal Alpha-Hemolysin, a Heptameric Transmembrane Pore. Science 1996, 274 (5294), 1859–1866. 10.1126/science.274.5294.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Asandei A; Chinappi M; Kang H-K; Seo CH; Mereuta L; Park Y; Luchian T Acidity-Mediated, Electrostatic Tuning of Asymmetrically Charged Peptides Interactions with Protein Nanopores. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7 (30), 16706–16714. 10.1021/acsami.5b04406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Asandei A; Apetrei A; Park Y; Hahm K-S; Luchian T Investigation of Single-Molecule Kinetics Mediated by Weak Hydrogen Bonds within a Biological Nanopore. Langmuir 2011, 27 (1), 19–24. 10.1021/la104264f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ervin EN; Barrall GA; Pal P; Bean MK; Schibel AEP; Hibbs AD Creating a Single Sensing Zone within an Alpha-Hemolysin Pore Via Site Directed Mutagenesis. Bionanoscience 2014, 4 (1), 78–84. 10.1007/s12668-013-0119-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Stoddart D; Heron AJ; Mikhailova E; Maglia G; Bayley H Single-Nucleotide Discrimination in Immobilized DNA Oligonucleotides with a Biological Nanopore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106 (19), 7702–7707. 10.1073/pnas.0901054106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kang X-F; Cheley S; Guan X; Bayley H Stochastic Detection of Enantiomers. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128 (33), 10684–10685. 10.1021/ja063485l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhao Q; Jayawardhana DA; Wang D; Guan X Study of Peptide Transport through Engineered Protein Channels. J Phys Chem B 2009, 113 (11), 3572–3578. 10.1021/jp809842g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Krishantha DMM; Breitbach ZS; Padivitage NLT; Armstrong DW; Guan X Rapid Determination of Sample Purity and Composition by Nanopore Stochastic Sensing. Nanoscale 2011, 3 (11), 4593–4596. 10.1039/c1nr10974j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Han Y; Zhou S; Wang L; Guan X Nanopore Back Titration Analysis of Dipicolinic Acid. Electrophoresis 2015, 36 (3), 467–470. 10.1002/elps.201400255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ainavarapu SRK; Brujic J; Huang HH; Wiita AP; Lu H; Li L; Walther KA; Carrion-Vazquez M; Li H; Fernandez JM Contour Length and Refolding Rate of a Small Protein Controlled by Engineered Disulfide Bonds. Biophys J 2007, 92 (1), 225–233. 10.1529/biophysj.106.091561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ching CB; Hidajat K; Uddin MS Evaluation of Equilibrium and Kinetic Parameters of Smaller Molecular Size Amino Acids on KX Zeolite Crystals via Liquid Chromatographic Techniques. Separation Science and Technology 1989, 24 (7–8), 581–597. 10.1080/01496398908049793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Dougherty DA Cation-Pi Interactions in Chemistry and Biology: A New View of Benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Science 1996, 271 (5246), 163–168. 10.1126/science.271.5246.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Goshe AJ; Steele IM; Ceccarelli C; Rheingold AL; Bosnich B Supramolecular Recognition: On the Kinetic Lability of Thermodynamically Stable Host-Guest Association Complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99 (8), 4823–4829. 10.1073/pnas.052587499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Counterman AE; Clemmer DE Volumes of Individual Amino Acid Residues in Gas-Phase Peptide Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121 (16), 4031–4039. 10.1021/ja984344p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Cheley S; Gu LQ; Bayley H Stochastic Sensing of Nanomolar Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate with an Engineered Pore. Chem Biol 2002, 9 (7), 829–838. 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.