Abstract

Vestibular schwannoma is a known cause of progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Treatment options include observation, radiation therapy and surgical resection. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula is a known postsurgical complication that can lead to CSF otorrhoea, rhinorrhoea or CSF leakage from the surgical wound. We present a case report of a patient who underwent vestibular schwannoma resection and postoperatively developed CSF rhinorrhoea, which was refractory to multiple attempts at surgical repair. This was successfully treated under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance using a biliary cytology brush to disrupt the surface of the eustachian tube followed by injection of n-Butyl cyanoacrylate.

Keywords: ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology, interventional radiology

Background

Vestibular schwannomas are a cause of progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks are a well-established complication of vestibular schwannoma surgery and were first described in 1944 by Dandy.1 After a translabyrinthine surgical approach for vestibular schwannoma resection, the rate of CSF leak from the wound, ear or nose ranges from 12% to 17%.2 3 An individual or a combination of techniques, including abdominal fat grafts, muscle and bone wax, fascia lata grafts and fibrin glue, have been employed to decrease leak rates.4 CSF rhinorrhoea can be managed conservatively using pressure dressings and lumbar punctures or lumbar drains. However, in cases of persistent CSF leak, revision surgery may be required. Revision surgery can include obliteration of the middle ear space with overclosure of the ear canal. Endonasal closure of the eustachian tube (ET) has also been described utilising cauterisation to induce scarring as well as marsupialisation of the mucosa overlying the torus tubarius.5

A single report using cadaveric specimens has shown that it is feasible to perform ET embolisation with ethyl vinyl alcohol (EVOH; Onyx, Medtronic, Irvine, California).6 The authors would like to document the use of ET embolisation to successfully treat a persistent CSF leak in a living human, as no such reports exist in the current literature.

Case presentation

A patient aged between 30 and 39 years presented with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and slowly progressive, bothersome non-pulsatile tinnitus related to a right vestibular schwannoma. The patient underwent a right translabyrinthine approach for microsurgical resection of the lesion on 1 May 2019. Postoperatively, the course was complicated by persistent CSF rhinorrhoea, and the patient, 5 weeks later (7 June 2019), underwent a right transmastoid repair of the leak with an abdominal fat graft. Two weeks postsurgery, the patient experienced a CSF leak again and underwent a repeat transmastoid repair (26 June 2019) without success. Given this, endoscopic ET obliteration via transoral and transnasal approaches was performed on 12 July 2019, which was unsuccessful. The patient underwent a revision transnasal endoscopic repair on 24 July 2019 with a multilayer patch (temporalis muscle, right nasal floor free mucosa, Nu-Knit, DuraSeal, Gelfoam and Merocel taped to nasal dorsum). This only partially resolved the symptoms. Finally, the patient underwent placement of a right transmastoid abdominal fat graft and closure of the ear canal on 6 August 2019. This controlled the CSF rhinorrhoea for 6 months until the patient travelled on an aeroplane to Denver and developed recurrence of clear fluid leaking from the right nare.

Investigations

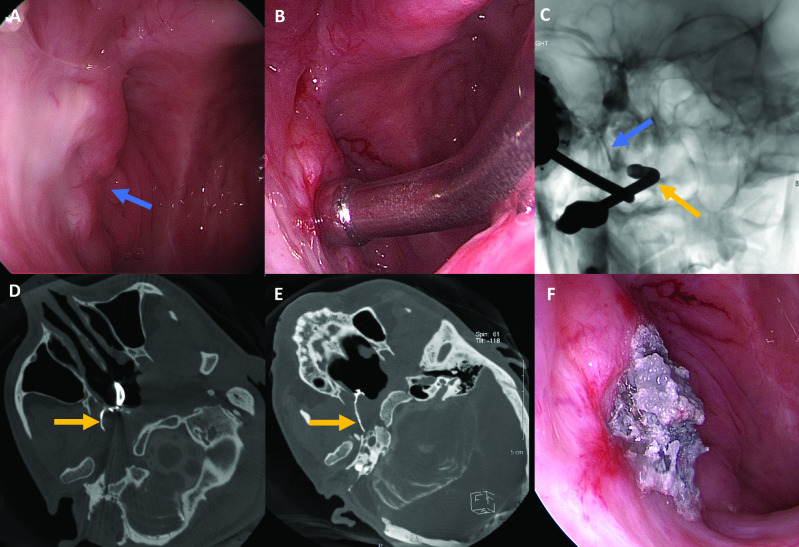

Workup of the patient’s CSF rhinorrhoea included provocative myelography. An intrathecal lumbar puncture was performed with the administration of 10 mL of iohexol (Omnipaque 240, GE Health Care, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). The patient was positioned in the Trendelenburg position to allow contrast to flow into the intracranial compartment. Next, in the CT scanner, the patient was placed in the prone position with the right side of the head down to recreate the position in which the patient experienced the most drainage. CT demonstrated the intrathecal contrast extending from the subarachnoid space, through the middle ear cavity, and into the ET. There was evidence of contrast pooling within the nasopharynx and right aspect of the nasal cavity (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Oblique postmyelogram CT demonstrates contrast tracking from the intracranial subarachnoid space through the right eustachian tube (yellow arrow) and layering within the nasopharynx (blue arrow).

Treatment

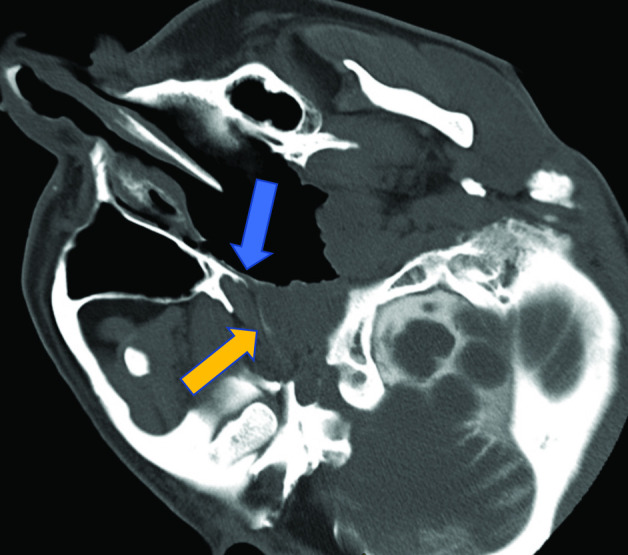

The embolisation procedure was performed on 13 May 2020. Under general anaesthesia, a 0° and 30° sinus endoscope was used to identify the remnant right ET orifice. A small dimple was noted at the expected location of the remnant ET orifice (figure 2A). A curved, metal suction cannula was positioned at the orifice of the right remnant ET (figure 2B). Through the metal suction cannula and under fluoroscopic guidance, a 2.8 French Progreat microcatheter (Terumo Medical Corporation, Somerset, New Jersey),) was advanced over its microwire into the right remnant right ET (figure 2C). The wire was removed and iodinated contrast was injected through the microcatheter. A DynaCT (Siemens) was performed and reformatted images were evaluated to document the location of contrast within the remnant ET (figure 2D). Next, through the metal suction cannula, a 3 mm diameter biliary cytology brush (Cook Medical) was introduced into the remnant ET. The bristle cytology brush was used to disrupt the endothelial lining of the remnant ET. n-Butyl cyanoacrylate (n-BCA) mixed 1:2 with lipiodol was prepared and injected under fluoroscopic guidance through the microcatheter placed in the remnant ET. Repeat DynaCT demonstrated glue filling the remnant ET from the skull base to the ostium (figure 2E). Endoscopic camera images confirmed filling of the ostium and adherence of polymerised n-BCA to the adjacent nasal mucosa (figure 2F). Excess glue was removed with suction, leaving a plug at the orifice.

Figure 2.

(A) Endoscopic image of the remnant eustachian tube (ET; blue arrow). (B) Endoscopic camera image with a curved metal suction canula at the orifice of the remnant ET. (C) Unsubtracted anteroposterior fluoroscopic single-shot image demonstrating the suction canula within the nasal cavity at ET orifice (yellow arrow) and microcatheter within the right eustachian tube (blue arrow). (D) Oblique intraoperative cone-beam CT image demonstrating a curved metal suction canula at the orifice of the right ET and contrast within the remnant eustachian tube (yellow arrow). (E) Oblique intraoperative cone-beam CT image demonstrates glue cast within the right ET (yellow arrow) extending to the skull base. (F) Endoscopic image demonstrates the glue cast adherent to the nasal mucosa at the ET orifice.

Outcome and follow-up

Postprocedure management included lifting restrictions to avoid straining and the avoidance of nose blowing and insertion of objects into the nares. At 1 month follow-up, the patient reported resolution of the right nare drainage, which had stopped 4 days after the injection of n-BCA. At 4.5 months post embolisation, there was continued resolution of both CSF rhinorrhoea and the sensation of wetness in the back of the nose. The patient denied feeling pain. However, the patient noted unchanged, non-pulsatile tinnitus similar to the described preprocedure symptoms as well as feeling ‘something plugged’ and ‘a bit of a heavy feeling’ in the back of the nose.

Discussion

CSF rhinorrhoea is a known and potentially debilitating complication following vestibular schwannoma resection. A single report using cadaveric specimens showed that it is feasible to perform ET embolisation using an angiographic catheter with EVOH.6 However, there are no living human case reports in the literature using the approach to treat a persistent CSF leak.

This case highlights the successful closure of a persistent CSF leak using a biliary cytology brush and n-BCA. The authors hypothesise that a brush biopsy device can disrupt the endothelial lining of a chronic sinus tract, which can assist in the development of scar formation to seal the tract similar to the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulae.7 Furthermore, given the adhesive properties and marked inflammatory reaction of n-BCA, this may be a better agent than EVOH to permanently occlude the ET in a patient presenting with a CSF leak. The procedure appears safe, can be performed on an outpatient basis in the neurointerventional radiology angiosuite, and may obviate the need for multiple open surgeries to resolve CSF rhinorrhoea. Previous procedural instrumentation of the ET likely aided in luminal epithelial agitation needed to establish a stable n-BCA plug. In assessing the potential for embolisation as a first-line treatment, it may be necessary to further investigate the efficacy of a biliary cytology brush alone to sufficiently disrupt the lumen. Further study and clinical follow-up is also needed to determine the longevity of symptom relief and ET occlusion.

Learning points.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea is a known complication of translabyrinthine approach for surgical resection of vestibular schwannomas.

Conservative and surgical options exist in the treatment of CSF fistula.

Endonasal obliteration via fluoroscopic-guided embolisation is feasible and can provide resolution of symptoms in properly selected patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Neeraj Chaudhary for his assistance in manuscript editing and image selection. We would like to acknowledge Ms Leonore Deichelbohrer, NP for her assistance in patient follow-up and clinical assessments.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ZWilseckMD

Contributors: All the authors (ZW, SB, ES and JJG) contributed to planning, drafting and editing the manuscript. ZW, ES and JJG performed the procedure.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Dandy WE. Treatment of rhinorrhea and otorrhea. Arch Surg 1944;49:75. 10.1001/archsurg.1944.01230020080001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamikoglu B, Wiet RJ, Esquivel CR. Translabyrinthine approach for the management of large and giant vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 2002;23:224–7. 10.1097/00129492-200203000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangus BD, Rivas A, Yoo MJ, et al. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks after vestibular schwannoma surgery. Otol Neurotol 2011;32:1525–9. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318232e4a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goddard JC, Oliver ER, Lambert PR. Prevention of cerebrospinal fluid leak after translabyrinthine resection of vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:473–7. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181cdd8fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwartler JA, Schulder M, Baredes S, et al. Endoscopic closure of the eustachian tube for repair of cerebrospinal fluid leak. Am J Otol 1996;17:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel NS, Carlson ML. Fluoroscopy-Assisted transnasal Onyx occlusion of the eustachian tube for lateral skull base cerebrospinal fluid leak repair. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2018;79:489–94. 10.1055/s-0038-1625975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman FN, Stavas JM. Interventional radiologic management and treatment of enterocutaneous fistulae. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015;26:7–19. 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]