Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) is a universal second messenger that participates in the regulation of innumerous physiological processes. The way in which local elevations of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration spread in space and time is key for the versatility of the signals. Ca2+ diffusion in the cytosol is hindered by its interaction with proteins that act as buffers. Depending on the concentrations and the kinetics of the interactions, there is a large range of values at which Ca2+ diffusion can proceed. Having reliable estimates of this range, particularly of its highest end, which corresponds to the ions free diffusion, is key to understand how the signals propagate. In this work, we present the first experimental results with which the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient is directly quantified in the cytosol of living cells. By means of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy experiments performed in Xenopus laevis oocytes and in cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we show that the ions can freely diffuse in the cytosol at a higher rate than previously thought.

Significance

Intracellular calcium signals are ubiquitous. Their versatility depends on the way in which local elevations of the cytosolic calcium concentration spread in space and time. The calcium diffusion coefficient is key in this regard. Calcium diffusion in the cytosol is hindered by the binding and unbinding of the ions with less mobile species. If the calcium concentration is high enough, calcium diffusion proceeds at its free rate. Having reliable estimates of the range of diffusion rates in situ is unavoidable for any quantitative modeling of calcium signals. In this work, we quantify directly the free diffusion coefficient of calcium in intact Xenopus laevis oocytes and in budding yeast live cells, finding that the ions can diffuse faster than previously thought.

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous intracellular messenger involved in the regulation of diverse biological processes (1). The versatility of Ca2+ signals relies on the variety of spatiotemporal distributions of the cytosolic [Ca2+] that elicit different end responses (2, 3, 4, 5). Prolonged high elevations of cytosolic [Ca2+] can lead to cell death (1,6). For this reason, cells have various mechanisms to keep its basal concentration at a very low (∼20–200 nM) level. Specialized proteins pump Ca2+ into internal stores, whereas others extrude it into the extracellular milieu. In vertebrates, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and sarcoplasmic reticulum are the principal Ca2+ internal stores, although mitochondria also take up Ca2+ (6). In budding yeast, the principal Ca2+ reservoir is the vacuole; the Golgi Apparatus and the ER are involved in the maintenance of Ca2+ basal levels by means of Ca2+ pumps and antiporter proteins that also provide Ca2+ to these organelles (7,8). The fastest way in which cells decrease their cytosolic [Ca2+] is by means of Ca2+ buffers (9), typically proteins, that bind Ca2+, modifying its free concentration and its transport rate (10, 11, 12). Intracellular Ca2+ signals are thus the result of the interplay of Ca2+ entry through specialized channels located either on the plasma membrane or the membrane of internal stores and the various processes that tend to reduce the cytosolic [Ca2+] and Ca2+ diffusion. Given a point of entry, the spatial range of the [Ca2+] elevation, which is delimited by the ions transport rate, then determines the eventual end response. Because of the reactions with the various buffers, the ions transport rate in the cytosol is not solely due to their free diffusion, the process that arises when (dilute) solute particles randomly change their direction of movement upon collision with solvent molecules (13,14). Under certain conditions, the net transport can be described in terms of effective diffusion coefficients that depend on the reaction rates with the buffers and on the concentrations and free diffusion coefficients of the interacting species (15, 16, 17). In the case of Ca2+, these effective rates go from very low values at basal conditions to values closer to the ions free diffusion rate upon buffer saturation. Thus, the effective coefficients change with [Ca2+] and, during the time course of a Ca2+ signal, are space and time dependent. It is the upper limit of the range of possible values, the free diffusion coefficient, that should remain fairly constant under various conditions. Knowing the range of possible values is relevant, especially for the understanding of situations in which the spatiotemporal distribution of intracellular Ca2+ is a key aspect of the signaling, as in frequency-encoded responses (18), long distance coupling phenomena (19,20), or at the transition to propagating either intra- (21, 22, 23, 24) or inter- (25,26) cellular Ca2+ waves. The direct quantification of the Ca2+ diffusion coefficient and of how it varies through the interaction with buffers in living cells is therefore of utmost importance.

The rate at which Ca2+ diffuses in the cytosol was estimated in Allbritton et al. (16) using cytosolic extracts of Xenopus laevis oocytes and radioactive Ca2+, 45Ca2+. The experiments of Allbritton et al. (16) were done by adding 45Ca2+ at one end of a test tube containing the cytosolic extract (previously equilibrated with different nonradioactive [Ca2+]) and then measuring the spatial spread of the radioactivity with time. The diffusion coefficient derived for the largest values of nonradioactive [Ca2+] probed in Allbritton et al. (16), 220 μm2/s, has been considered an estimate of the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient, DCa, in cells and has been widely used in mathematical models of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. One important caveat in Allbritton et al. (16) analyses is that 45Ca2+ ions interactions with buffers displace pre-existing nonradioactive ions, which in turn, also contribute to signal propagation but are experimentally invisible. In this sense, it has been shown that the effective rates with which 45Ca2+ diffuses in experiments like those in Allbritton et al. (16) are lower than those that would have been calculated measuring both contributing ions, radioactive and nonradioactive Ca2+ (17). Considering these analyses, it is legitimate to ask whether the largest value obtained by Allbritton et al. (16) underestimates the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient. In Allbritton et al. (16), this estimate was compared with the (free) diffusion coefficient of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), a co-agonist (with Ca2+) of IP3 receptors (IP3R) (27, 28, 29), a type of Ca2+ channel that is located on the membrane of the vertebrate cells ER. Because of regulation of cytosolic Ca2+, IP3R-mediated signals are subject to calcium-induced calcium release (30), by which the Ca2+ released through one open IP3R induces the opening of nearby ones. Because high cytosolic Ca2+ also inhibits IP3Rs, whether IP3 or Ca2+ reaches the IP3Rs first can thus determine whether a Ca2+ wave can propagate or not. In Allbritton et al. (16), the free IP3 diffusion coefficient was estimated as ∼280 μm2/s, i.e., larger than DCa. More recent experiments (31) have shown that IP3 diffusion in the cytosol is also hindered by trapping mechanisms; values similar to the effective diffusion rate of buffered Ca2+ (∼5 μm2/s) were estimated in Dickinson et al. (31). In view of these results, the question of what is the range within which the transport rates of Ca2+ and IP3 can vary in living cells becomes most relevant. Having a reliable estimate of DCa in the cytosol is also relevant outside the context of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signals. In particular, we think it is key to understand the Ca2+-dependent responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to external cues (32, 33, 34, 35), especially for the recently observed Ca2+ pulses that are elicited in response to the presence of the sexual pheromone (18).

Another limitation of the experiments of Allbritton et al. (16) is that they were performed in cytosolic extracts. Ca2+ diffusion in live cells was analyzed with experiments in which caged Ca2+ was photo-released and subsequently observed using a Ca2+ indicator (36). These observations, however, correspond to the fluorescence emitted by the Ca2+-bound dye. Going from the observed signal to the underlying Ca2+ spatiotemporal distribution is not completely straightforward; it requires a detailed model (37) and having reliable estimates of various biophysical parameters that are frequently unknown (38, 39, 40). To address these limitations for this work, we performed fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) experiments with which we estimate the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient in intact cells without the need of any previous knowledge of other biophysical parameters.

FCS is an optical technique that uses the statistical analysis of fluorescence fluctuations in a small detection volume to quantify the processes that underlie the fluctuations (41). In combination with confocal microscopy, FCS has been widely used to estimate diffusion coefficients, concentrations, and reaction rates (42, 43, 44). These estimates are derived from the correlation times that characterize the autocorrelation function (ACF) of the fluorescence fluctuations. The direct application of this technique to the case of Ca2+ transport in live cells is not completely straightforward; intracellular Ca2+ is observed indirectly monitoring sensors that change their fluorescence properties upon Ca2+ binding (45,46) and that compete with the intracellular Ca2+ buffers disrupting the normal time course of the underlying processes (12,47). Our previous work on FCS experiments using a single-wavelength (SW) Ca2+ sensor to monitor Ca2+ in aqueous solutions (48) and in solutions containing the Ca2+ chelator, EGTA, as well (49) showed that it was possible to derive the free diffusion coefficients of the nonfluorescent species (Ca2+ and EGTA) from the correlation times. The theoretical studies of Villarruel and Dawson (50) explained why this was possible. In this work, we build upon these previous works and present the results of FCS experiments performed in X. laevis oocytes and in live S. cerevisiae cells using chemical and genetically encoded fluorescent Ca2+ sensors, respectively. In this way, quantifying directly the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient, we have found that the Ca2+ ions can freely diffuse in the cytosol at a faster rate than previously thought.

Materials and methods

Cells

S. cerevisiae

SFmCherry-GCaMP6f expression vector construction. A vector expressing a dual sensor composed by the Ca2+ sensor green fluorescent protein-calmodulin fusion protein 6f (GCaMP6f) fused to the superfolder monomeric Cherry (SFmCherry) was constructed. The yeast integrative vector pRS306K-GPD1p-GCaMP6f-ADH1t-a (18) was used as template to perform restriction free cloning reactions (51) designed to insert SFmCherry and a short and flexible linker open reading frame in GPD1p-GCaMP6f. Then, a longer and rigid linker based on the aminoacid sequence of ER/K ((52,53) plasmids and oligos sequences available upon request) was inserted by RF cloning reactions in SFmCherry-GCaMP6f in the middle of the short linker to avoid Förster resonance energy transfer between the two proteins (54) (see Fig. S1). The final vector was verified by sequencing and subsequently linearized for yeast transformation.

Yeast strain and growth conditions. The strains used in this work are in the W303 background (leu2-3, 112 trp1-1 can1-100 ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11). Cells were grown at 30°C in either rich yeast extract-Peptone-Dextrose (YPD) medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, and 2% glucose) or synthetic defined medium containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Difco Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 2% glucose, and the appropriate drop-out mixture (mix) of amino acids, according to supplier’s instructions (Complete Supplemental Mixture; Sunrise Science Products, Knoxville, TN). In general, yeast strains were grown in 3 mL of rich medium YPD to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2–0.6 and then were cultured for a minimum of 18 h in synthetic defined medium and supplemented with 80 ng/mL adenine and tryptophan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 30°C to OD600 = 0.3–0.5. For imaging, 200 μL of cell culture was incubated in concanavalin-A (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated chambers for 10 min (number 1.5 glass; MatTek, Ashland, MA). Finally, synthetic defined medium was replaced by a fresh one, and cells were imaged. To generate a rise of cytoplasmic Ca2+, 20 μL of CaCl2 2 M were added to the medium (final volume, 220 μL) (55). Data were acquired during the first 5 min after the CaCl2 addition so as to prevent the mounting of the cell’s response to the increase in Ca2+ (55). Membrane integrity was previously verified in all cases.

X. laevis oocytes

X. laevis oocytes, previously treated with collagenase and stored in Barth’s solution (88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 0.33 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.14 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 0.05 mg/mL gentamycin (pH 7.4)) at 18°C, were loaded with 37 nL of a solution containing the Ca2+ indicator Fluo8 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and, for some experiments, the Ca2+ chelator EGTA. Fluo8 is a SW green fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, with a molecular weight of 877 g/mol and kD = 432 and 600 nM in vitro and in vivo, respectively. It has a >100 times fluorescence enhancement when bound to Ca2+. Its excitation maximum is at 488 nm, and its emission maximum is at 525 nm. EGTA has dissociation constant kD = 140 nM and diffusion coefficient in solution D = 405 μm2/s. The concentration of Fluo8 in the microinjected solution was 100 μM or 1 mM, and the concentration of EGTA was between 1.25 and 10 mM. Assuming a 1 μL cytosolic volume, the final concentration of Fluo8 was 3.7 and 37 μM, respectively, and that of EGTA ranged within 47–370 μM. Injections were performed at the equator of the cell. Microinjections were done using a Drummond Nanoject II microinjector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) with an injection speed of 26 nL per second. Solutions to be injected were backfilled into glass micropipettes obtained by heat stretching of Borosilicate Drummond capillaries (7′′ long, 0.53 mm internal diameter, and 1.14 mm external diameter) with a Puller PC-10 (Narishigue, Amityville, NY), which uses a heat method and vertical stretching by force of gravity. Oocytes were mounted on an aluminum chamber with a coverslip at the bottom for microscopic observations. Oocytes were deposited with the animal hemisphere down and immersed in Barth’s solution. To avoid photodamage of the ER membrane and the consequent Ca2+liberation, FCS measurements were performed at 3 μm from the granules zone.

Data acquisition

Fluorescence records were obtained at room temperature (∼20°C) in a spectral confocal scanning microscope FluoView 1000 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a photomultiplier detector, using a 60× oil immersion objective (UPlanSApo), NA 1.35, and a 115 μm pinhole size.

S. cerevisiae cells

The sample was illuminated with the 488 nm line of an Argon laser with an excitation power of 6–10 μW and the 543 nm line of a Helium-Neon laser with an excitation power of 2 μW. Cells were not simultaneously illuminated with the two laser lines because the SFmCherry protein gets bleached with the 488 nm laser line. The fluorescence was collected from a single point located at ∼2 μm from the coverslip at a 100/50 kHz acquisition rate during ∼10.8/21.6 s (equivalently, 1,024,000 data points) in the 500–530/580–630 nm range for the 488/543 nm lines (green/red channel).

X. laevis oocytes

The sample was illuminated with the 488 nm line of an Argon laser with an excitation power of 6–10 μW. The fluorescence was collected from a single point located at ∼15 μm from the coverslip at a 50 kHz acquisition rate during ∼180 s (equivalently, 8,388,096 data points) in the 500–600 nm range.

Calibration of the observation volume

The confocal volume was calibrated for each configuration. 100 nM of fluorescein (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a buffer solution (pH 9) was used to determine the lateral widths of the effective volume at 15 and 2 μm from the coverslip for the 488 nm line. 100 nM of 10 kDa tetramethylrhodamine dextran (TMR-D; Sigma-Aldrich) in a buffer solution (pH 9) was used to determine the widths at 2 μm from the coverslip for the 543 nm line. The calibrations were done assuming that the diffusion coefficients of fluorescein and TMR-D were 425 (56) and 85 μm2/s (57), respectively. The resulting values of the lateral widths were wr = (0.311 ± 0.002) μm and wr = (0.1581 ± 0.0047) μm for the 488 nm line at 15 and 2 μm from the coverslip, respectively, and wr = (0.1623 ± 0.0048) μm for the 543 nm line. The widths derived from the calibration at 15 μm from the coverslip were used in the experiments performed in oocytes, and those obtained at a 2-μm distance for the 488 nm and 543 nm lines were used in the experiments performed in yeast observed in the green and red channels (Gch and Rch), respectively.

Data analysis

Computation of the ACF

The ACF of the fluorescence fluctuations, G(τ), is given by:

| (1) |

where f(t) is the fluorescence collected from the observation volume at time t, is its mean value, and δf(t) is the deviation with respect to this mean at each time, t. To compute the experimental ACF N-long fluorescence record (N = 8,388,096 for oocytes and N = 1,024,000 for yeast), fluorescence record was divided into segments of Nl = 213 time points each. An ACF was computed for each of these N/Nl segments as:

| (2) |

adding zeros as needed, and then the average over the Gks was performed. This was done using custom-made routines on Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) (58). The average ACFs were fitted with different expressions as explained in what follows using the nlinfit function of Matlab (58). To avoid the effects of after-pulsing, the first one to three points of the experimental ACF were not considered for the fitting.

Fitting the ACF

To fit the ACFs obtained with fluorescein, TMR-D, or SFmCherry, we used the analytic expression that corresponds to a freely diffusive fluorophore that does not change its fluorescence properties with binding (see e.g., (59)):

| (3) |

i.e., a one-component model, where w = wz/wr is the aspect ratio of the sampling volume, and wz and wr are the sizes of the beam waist along z and r, with z the spatial coordinate along the beam propagation direction and r a radial coordinate in the perpendicular plane. τ1 is the correlation time, which is related to the diffusion coefficient of the sample.

To fit the ACFs obtained with Fluo8 and GCaMP6f, we tried different forms, with two or three components, that had been used to analyze FCS data obtained from experiments in aqueous solutions with Ca2+ and a SW Ca2+ indicator (48,49):

| (4) |

| (5) |

In particular, when the ACFs derived from the experiments performed in aqueous solutions with Fluo8 and Ca2+ and in oocytes at basal conditions (i.e., with no EGTA added) and the ACFs obtained for the fluorescence detected in the Gch in the case of yeast (emission from GCaMP6f) were fitted with a three-component model (Eq. 4), the diffusion coefficient derived from τ1 and τ1 were indistinguishable. That is why in such cases, we present the results obtained by fitting the ACFs with a two-component model (Eq. 4). For the ACFs obtained from experiments performed in oocytes injected with Fluo8 and EGTA, we present the fits obtained with a three-component model (Eq. 5).

In all cases, we used w = wz/wr = 5, and the width, wr, is derived from a calibration as explained before.

The goodness of the fit was evaluated computing the difference between the experimental ACFs, G(τ), and the fits, Gfit(τ), as:

| (6) |

where dτ is the fluorescence acquisition time, and Nl is the total number of data points of the experimental ACF.

Analysis of the fitted parameters

The diffusion coefficients, Di, were derived from the fitted correlation times, τi, as:

| (7) |

As explained in the Supporting materials and methods, in reaction-diffusion systems, these are actually effective diffusion coefficients, although they can be well approximated by free diffusion ones depending on the conditions.

The estimates derived for a given parameter could be different depending on the analyzed record. To study this variability, we generated histograms of the fitted parameters, binning the data in 10 equally spaced intervals. On some occasions, the histograms looked as if there was more than one population of parameters. To analyze this aspect, we applied the Akaike criterion (60) to determine if the underlying parameter distribution was uni or bimodal, employing the gmdistribution.fit function of Matlab. This function was used to estimate the parameters of a model distribution with one or two Gaussian components and to obtain the Akaike information criterion of each of these models. We then calculated the Akaike criterion’s difference (AkD) between both models. The values of AkD range from −1 to 1, with positive values suggesting bimodality and negative values suggesting unimodality. Results from the fittings are reported as mean ± SE for unimodal distributions and as mean and fraction of the total distribution (between parentheses) and AkD for bimodal ones. The subscripts a and b were used to identify the mean diffusion coefficient of each population. To decide whether the data followed a uni or bimodal distribution, not only the AkD was taken into account but also the proportion and the data distribution inside each group.

Numerical computations

We calculated the expected (theoretical) effective diffusion coefficients for reaction-diffusion systems with Fluo8 and Ca2+ and with Fluo8, EGTA, and Ca2+ as done in Sigaut et al. (48,49) using the parameters of Table 1 (also see Supporting materials and methods) and the following concentrations: [Fluo8]tot = 3.7 or 37 μM, [EGTA]tot = (0–370) μM, and [Ca2+]eq = 100 nM. The notation [X]tot indicates the total concentration of species, X, i.e., the sum of its free and all of its bound forms. The notation [Ca2+]eq refers to the free Ca2+ concentration in equilibrium with the other species of the system with which it interacts. The various diffusion coefficients listed in the tables (DX) are free diffusion coefficients of the corresponding species, X, in aqueous solutions. We assume that the ratio between any two of these free coefficients remains the same in aqueous solution and in the cytosol. It is implicit in this assumption that the free coefficients change with viscosity (and temperature) in such a way that their ratios do not. We assume that the reaction between Ca2+ and any of the other species, X, is of the form:

| (8) |

with dissociation constant kDX = koffX/konX. The off-rate and the dissociation constants are listed in Table 1. For the computation of the effective coefficients, we assumed that the free diffusion coefficient of each species, X, that interacts with Ca2+ is the same in its free and its Ca2+-bound form (i.e., DX = DCaX). In the case of the computations in the cytosol, we either rescaled all the diffusion coefficients by a common factor or divided all by the largest one obtained at each condition probed. For the first type of rescaling, we estimated the Ca2+-free diffusion coefficient in the cytosol from the experiments and calculated the rescaling factor as the ratio between this estimate and the value, DCa, of Table 1. In the second case, we compared the theoretical ratios with similar ones between the average coefficients derived from the experiments at each condition probed. Proceeding in this way is meaningful under the assumption that the ratios between the free diffusion coefficients are the same in solution and in the cytosol. These computations allowed us to relate the coefficients derived from the experimental fits with those that are acting in the system under study.

Table 1.

Parameters used for the computations corresponding to a system with Fluo8 and Ca2+ or Fluo8, EGTA, and Ca2+

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| DFluo8 | 100 μm2/s |

| DEGTA | 405 μm2/s |

| DCa | 760 μm2/s (61) |

| kDFluo8 | 432a and 600b nM |

| koffFluo8 | 45a and 70b s−1 |

| kDEGTA | 150 nM |

| koffEGTA | 0.75 s−1 |

The diffusion coefficients correspond to free diffusion of each species in aqueous solution.

The reaction constants correspond to aqueous solution.

The reaction constants correspond to situations in vivo. In the case of the reaction EGTA-Ca2+, we do not make this distinction.

Results

The design of the experiments described in this section was inspired by our previous work (48, 49, 50) on the use of FCS in aqueous solutions in which the fluorescence was emitted by SW Ca2+ sensor. These sensors increase their fluorescence intensity by a large factor when bound to Ca2+ (45). In these experimental setups, the fluorescence fluctuations not only depend on the transport of the sensor in and out of the observation volume but also on its binding reaction with Ca2+. Our previous work showed that the characteristic times of some of the processes that shape the free [Ca2+], such as diffusion and binding-unbinding reactions, are reflected on the correlation times of the fluorescence fluctuations ACF. The best fits of the experimental ACFs of Sigaut et al. (48,49) and Villarruel and Dawson (50) were characterized by two diffusive timescales that we could associate either to free or effective diffusion coefficients of the problem. Varying the concentration of one of the reactants, we determined if the derived coefficients were free (if they remained constant) or effective (if they changed). We describe in what follows how we proceeded with the two used cell types and the results that we obtained.

FCS experiments in S. cerevisiae cells

In this work, we used a modified version of the Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6f, which was originally developed to monitor neuronal activity and which we have already adapted to S. cerevisiae (18). To count with a Ca2+ sensor that was better suited to our FCS experiments, we fused GCaMP6f to SFmCherry, which is Ca2+ insensitive. Provided that there is no energy transfer between the two linked fluorophores (see Fig. S1), the fluctuations of the fluorescence coming from the latter should only depend on the transport properties of the sensor in and out of the observation volume, i.e., they serve to determine its free diffusion coefficient.

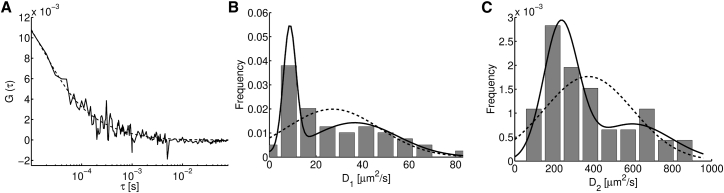

First, we performed FCS experiments in SFmCherry-LL-GCaMP6f expressing S. cerevisiae cells when the fluorescence was excited with the 543 nm line and collected in the Rch ( nm). This emission comes from the SFmCherry part of the sensor. Because we expect the diffusion coefficient of SFmCherry-LL-GCaMP6f to be unaltered upon Ca2+ binding (given the small fraction of the protein mass that an individual ion represents), we assumed that the corresponding SFmCherry ACF is solely characterized by one correlation time: the one associated to the free diffusion coefficient of the sensor. For this reason, this set of experimental results was fitted using a one-component model expressed in Eq. 3. We show in Fig. 1 A the example of an ACF obtained in this case and the corresponding fit. From the fits over 248 ACFs, we derived the SFmCherry-LL-GCaMP6f diffusion coefficient, D1 = (8 ± 0.25) μm2/s. The histogram (in frequency) of the derived D showed a relatively long tail toward the largest values (Fig. 1 B). The application of the Akaike criterion (see Materials and methods) gave a positive value for the AkD (AkD= 0.0613). The obtained means of the two subpopulations were D1a= 7 μm2/s and D1b = 12 μm2/s, with proportions, 70 and 30%, respectively. As discussed later, the difference can be attributed to heterogeneous cytoplasmic viscosity (62, 63, 64, 65, 66). These values are compatible with the ones previously estimated for cytosolic proteins in living yeast cells (67) and with those derived from the observations in the Gch (see below), indicating that we were able to infer the free diffusion coefficient of this genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor.

Figure 1.

FCS experiments to estimate the free diffusion coefficient of the Ca2+ dual sensor in S. cerevisiae. The experiments were performed with SFmCherry-LL-GCaMP6f-expressing cells incubated in synthetic complete growth media, exciting the fluorescence emitted by the SFmCherry part of the construct (excited with the 543 nm line and collected in the Rch). (A) Example of an ACF (solid line) and of its corresponding fit (dashed line) obtained with Eq. 3, χ2 = 0.003107. (B) Histogram (in frequency) of the diffusion coefficient derived from the fitting parameter, τ1, with curves that correspond to unimodal (dashed line) and bimodal (solid line) approximations of the obtained distributions (n = 248).

Subsequently, we performed FCS experiments as previously but illuminating the cells with the 488 nm line of an Argon laser and observing the fluorescence coming from the GCaMP6f part of the sensor in the 500–530 nm range. We show in Fig. 2 A an example of the ACF obtained in this way when the cells were incubated in synthetic complete growth media (solid line) and the best fit (χ2 = 0.002022) of the form of Eq. 4 (dashed line). Equation 4 is characterized by two diffusive timescales, τ1 and τ2, from which we derived two diffusion coefficients, D1 and D2. Attempts to fit the ACF with three diffusive components always converged to having only two distinguishable diffusion coefficients. We show in Fig. 2, B and C frequency histograms of D1 and D2, respectively, obtained from 185 fits. The mean values and corresponding mean ± SE over all the fitted parameters were D1 = (9 ± 1) μm2/s and D2 = (305 ± 12) μm2/s. Checking for bimodality, the AkD values obtained were 0.2664 for D1 and 0.0292 for D2, with mean values and proportions of D1a = 6 μm2/s (84%), D1b = 30 μm2/s (16%), D2a = 271 μm2/s (92%), and D2b = 698 μm2/s (8%).

Figure 2.

FCS experiments in SFmCherry-LL-GCaMP6f-expressing S. cerevisiae cells incubated in synthetic complete growth media collecting the fluorescence emitted by GCaMP6f (Gch). (A) Example of an ACF (solid line) and of its corresponding fit (dashed line) obtained with Eq. 4, χ2 = 0.002022. (B and C) Histograms (in frequency) of each of the two coefficients derived from the fitting parameters, with curves that correspond to unimodal (dashed line) and bimodal (solid line) approximations of the obtained distributions (n = 185).

We then repeated the experiments in cells incubated in synthetic complete growth media supplemented with 200 CaCl2 so as to change the equilibrium between intracellular Ca2+, the sensor, and the Ca2+ buffers. Also, in this case, we used Eq. 4 to fit the corresponding ACFs. We show in Fig. 3 histograms (in frequency) of the coefficients, D1 and D2, derived in this case. The mean values and corresponding mean ± SE were D1 = (27 ± 3) μm2/s and D2 = (374 ± 33) μm2/s. The AkD values obtained were positive, 0.0451 and 0.0192 for D1 and D2, indicating bimodality. The mean values and proportion of each population were D1a = 9 μm2/s (34%), D1b = 37 μm2/s (66%), D2a = 236 μm2/s (63%), and D2b = 605 μm2/s (37%).

Figure 3.

FCS experiments in SFmCherry-GCaMP6f-expressing S. cerevisiae cells incubated in synthetic complete growth media supplemented with 200 CaCl2 collecting the fluorescence emitted by GCaMP6f. (A) Example of an ACF (solid line) and of its corresponding fit (dashed line) obtained with Eq. 4, χ2 = 0.001144. (B and C) Histograms (in frequency) of the diffusion coefficients derived, with curves that correspond to unimodal (dashed line) and bimodal (solid line) approximations of the obtained distributions (n = 49).

The mean value obtained for D1 in experiments performed in cells with basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels (BC) and D1a for the measurements performed in cells with higher levels of cytosolic Ca2+ (HC) are consistent with the diffusion coefficient derived for the sensor, D = (8 ± 5) μm2/s. The mean values derived for the two populations of D2 in each set of experiments, with basal or high cytosolic Ca2+ levels, are similar but with different proportions and could correspond to effective coefficients.

FCS experiments in X. laevis oocytes

In this section, we present the results of FCS experiments performed in X. laevis oocytes. These oocytes are a well-known model system in which Ca2+ can be observed microinjecting the cells with solutions of the sensor of choice. The basal conditions can also be modified in a controlled manner, including different compounds in the microinjection mix. The experiments were done using the SW Ca2+ sensor, Fluo8, whose fluorescence intensity increases over 100 times when bound to Ca2+. In some experiments, the Ca2+ chelator EGTA was also added to the cells. To obtain an independent estimation of the free diffusion coefficient of Fluo8, we performed experiments in aqueous solutions (see Fig. S2).

We show in Fig. 4 A the example of an ACF obtained in a X. laevis oocyte microinjected with a solution containing 100 μM Fluo8 and no added EGTA (solid line) and the corresponding best fit (χ2 = 0.0002215), which was obtained using Eq. 4 (dashed line). Two diffusion coefficients, D1 and D2, were derived from the fits. As in the experiments in S. cerevisiae, attempts to fit the ACFs with three diffusive components gave only two distinguishable diffusion coefficients. We show in Fig. 4, B and C histograms (in frequency) of the values obtained for the two coefficients over 107 experiments. The average values and mean ± SE for these distributions were D1 = (24 ± 1) μm2/s and D2 = (434 ± 14) μm2/s, respectively. The AkD was positive in both cases, 0.0445 and 0.008, for D1 and D2, respectively. In particular, we obtained for D1, D1a = 15 μm2/s and D1b = 36 μm2/s with proportions 56 and 44%, and for D2, D2a = 372 μm2/s and D2b = 644 μm2/s, with proportions 77 and 23%.

Figure 4.

FCS experiments in X. laevis oocytes microinjected with the Ca2+ sensor, Fluo8. The microinjection solution contained 100 μM of Fluo8 and no added EGTA. (A) Example of an ACF (solid line) and of its corresponding fit (dashed line) obtained with Eq. 4, χ2 = 0.0002215. (B and C) Histograms (in frequency) of each of the two coefficients derived from the fitting parameters, with curves that correspond to unimodal (dashed line) and bimodal (solid line) approximations of the obtained distributions (n = 107).

We then repeated the experiments adding EGTA to the microinjection mix for two different concentrations of the dye (low 100 μM and high 1 mM; final values in the cytosol, low ∼3.7 μM and high ∼37 μM). The ACFs obtained were then fitted with Eq. 5, from which we could derive three distinguishable diffusion coefficients, D1, D2, and D3. We show in Fig. 5, A and B, with symbols, the three coefficients derived from the fits as functions of the EGTA concentration used in the mix. We also show, with curves, the four coefficients that, according to the theory, characterize the ACF in the case of a reaction-diffusion system with Ca2+, Fluo8, and EGTA (see Materials and methods; Supporting materials and methods). Three of these coefficients are effective ones (depicted with red, blue, and green), and the fourth one corresponds to the free coefficient of the dye, DFluo8. We computed them as explained in Materials and methods using the parameters of Table 1 and the same basal cytosolic Ca2+ concentration with or without EGTA (the rationale for it being that cells have various mechanisms to keep basal Ca2+ constant). The free diffusion coefficients shown in Table 1 actually correspond to values in aqueous solution. We rescaled them by the ratio between an estimate of DCa in the cytosol and its value in aqueous solution, = 760 μm2/s, to compute the theoretical curves. In Fig. 5 A, we set equal to the largest fitted coefficient derived from the experiments with the largest [EGTA] (D = 425 μm2/s). In Fig. 5 B, we set equal to the average of the largest coefficients derived from the fits with all [EGTA] values (D = 365 μm2/s). The reason for this second choice is that, for these [EGTA] values, the largest effective coefficient given by the simple Fluo8-Ca2+-EGTA reaction-diffusion model (red curve) is already indistinguishable from DCa. It is possible that this is not the case for the actual system probed experimentally, given the simplicity of the model, the variability of the experimental points (diamonds), and that the estimate, , derived from the data in Fig. 5 A is ∼16% larger than the average of the values in Fig. 5 B. If we use the same rescaling factor in Fig. 5 B as in Fig. 5 A, we obtain approximately the same figure, with the only difference being that the values along the theoretical curves are ∼16% larger than in the one shown here. This does not change the conclusions that we derive from this figure. Another possible reason for the differences between the theoretical curves and the experimental points is that variations in the cytosolic buffer composition of different cells or regions can lead to changes in the resulting effective diffusion coefficients. To scale out these variations, we show in Fig. 5, C and D, with symbols, the ratios between the coefficients obtained experimentally at each [EGTA] and the largest coefficient derived from the fits at the same [EGTA] value. Equivalently, for the theoretical curves, we plot the ratio between each coefficient and the largest effective one for each [EGTA]. The values derived directly from the fitting parameters can be seen in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Diffusion coefficients derived from experiments performed in oocytes with EGTA and Fluo8 and theoretical results obtained for a reaction-diffusion system with Ca2+, EGTA, and Fluo8. (A) and (C) correspond to experiments with [Fluo8] = 100 μM in the mix and (B) and (D) to [Fluo8] = 1000 μM in the mix. In all cases, the ACFs were fitted with Eq. 5, from which three diffusion coefficients, D1 < D2 < D3, were derived (shown with symbols). The theoretical computations (shown with solid lines) were done using the parameters of Table 1. In (A) and (B), the theoretical results (DFluo8, Def1, Def2, and Def3, in black, blue, red, and green, respectively) were rescaled by the factors 0.56 in (A) and 0.48 in (B), which we estimated as the ratio between DCa in the cytosol and in aqueous solutions (see main text). In (C) and (D), we show the ratios between the coefficients and one of them, Dmax, at each [EGTA]. For the theoretical curves, Dmax is the largest effective coefficient for the concentrations probed, Def2 (black: DFluo8/Def2, blue: Def1/Def2, green: Def3/Def2), and for the experimental ones, it is the largest fitted one, D3 (squares: D1/D3, circles: D2/D3). For a reference, we also include D3/D3 (diamonds) and Def2/Def2 (red curve). For the numerical computations, we used [Fluo8] = 3.7 and 37 μM for low and high Fluo8, respectively. Symbols represent mean values and error bars the mean ± SE. To see the figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Diffusion coefficients derived from the ACFs obtained in the experiments performed in oocytes with EGTA and two concentrations of [Fluo8]

| [EGTA]mix | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low [Fluo8] (Fig. 5, A and C) | 1.25 | 30 ± 4 | 213 ± 21 | 393 ± 22 |

| 2.5 | 26 ± 3 | 255 ± 23 | 411 ± 18 | |

| 3.75 | 19 ± 3 | 219 ± 19 | 357 ± 24 | |

| 5 | 34 ± 6 | 280 ± 32 | 450 ± 29 | |

| 10 | 30 ± 3 | 235 ± 19 | 425 ± 18 | |

| High [Fluo8] (Fig. 5, B and D) | 1.25 | 7 ± 1 | 124 ± 17 | 311 ± 34 |

| 2.5 | 9 ± 1 | 111 ± 10 | 388 ± 33 | |

| 3.75 | 9 ± 1 | 78 ± 13 | 309 ± 28 | |

| 5 | 7 ± 1 | 126 ± 21 | 453 ± 37 |

Diffusion coefficients are expressed in μm2/s, and [EGTA] is expressed in mM. Diffusion coefficients are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Discussion

The rate of Ca2+ diffusion is key to determine the cell responses that Ca2+ signals can elicit (1). Diffusion in dilute solutions is produced by the same processes that determine the viscosity of the medium, and the diffusion and viscosity coefficients are inversely proportional to one another (13). In such a case, the mean-square displacement of the particles over a time, t, is proportional to Dt, with D, the (free) diffusion coefficient of the particles. Diffusion in the intracellular medium does not always proceed as in dilute solutions, being affected by factors such as molecular crowding and cellular structure. In the case of Ca2+, the displacement of its ions is also affected by the binding/unbinding to/from different cell components generically called buffers. Thus, when moving across regions of approximately uniform buffer concentrations, after a transient, the mean-square displacement of the ions is proportional to with , an effective diffusion coefficient that depends on the concentration of Ca2+ and of the species it reacts with. as [Ca2+] increases, and the buffers become saturated (16,17). Knowing the range of values over which the Ca2+ diffusion rate can vary, particularly its highest (free diffusion) end, is key for a comprehensive understanding of the signals. In this work, we have built upon our previous theoretical and experimental works in aqueous solutions (48, 49, 50) to quantify the Ca2+ diffusion coefficient directly in intact living cells using FCS. As reflected in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4, the coefficients estimated with the experiments can vary quite noticeably between cell regions and cells that are subjected to the same conditions. As discussed in what follows, the variability can be due to differences in intracellular viscosity (which affect both free and effective coefficients) or to buffer composition (which not only affects the values that the effective coefficients take on but also which coefficients can be estimated with the experiments).

In this article, we have presented the results obtained in two cell types, X. laevis oocytes and cells of S. cerevisiae, in different conditions. A summary of the diffusion coefficients derived from the experiments is given in Table 2 (corresponding to the experiments of Fig. 5 that were performed in oocytes injected with Fluo8 and EGTA) and Table 3 (corresponding to the experiments of Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 that were performed, respectively, in S. cerevisiae observing the emission in the red and green channels (Rch and Gch), repeating the latter with a high [Ca2+] bath and in oocytes injected solely with Fluo8). The experiments of Fig. 5 and Table 2 illustrate how the values that the effective coefficients take on and the coefficients that can be estimated with the experiments vary with buffer composition, providing additional support to our interpretation of the results of Figs. 2, 3, and 4. The ACFs of the experiments of Fig. 5 were fitted with Eq. 5 because three distinguishable diffusion coefficients (D1, D2, and D3) could be derived. The main results of the article are contained in Table 3, where each row corresponds to the estimates derived from the analysis of many records obtained under the same condition. The ACFs of the experiments of Fig. 1 (first row in Table 3) were fitted with Eq. 3 because, as expected, they were characterized by a single diffusive component with coefficient D1. Those of Figs. 2, 3, and 4 (rows 2–4 of Table 3) were fitted with Eq. 4 because the use of Eq. 5 yielded, in almost all cases, two coefficients that were indistiguinshable between themselves. This occurs even if the actual underlying dynamical system is characterized by the diffusive timescales of the various species that Ca2+ interacts with. Which of these timescales can be captured in an experiment in which only one fluorescenct species is observed (Ca2+-bound dye) depends on the (spatially local) equilibrium situation that is being probed in each case (50). All the results reported in Table 3 showed a large variability of the coefficients estimated under the same conditions. To account for this variability, which is apparent in the long tails of the histograms of Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4, we applied the Akaike criterion (60), which determined that they were described better by a bimodal (the superposition of two Gaussians) than by a unimodal (Gaussian) distribution. This is why in Table 3, we report the means over the whole population of each derived coefficient (D1 and D2) and over each of the two subpopulations determined by the Akaike criterion (D1a, D1b, D2a, and D2b). We discuss in the following the interpretation of all these results.

Table 3.

Diffusion coefficients derived from the FCS experiments performed in S. cerevisiae cells, observing the fluorescence emitted by the SFmCherry (Rch) or the GCaMP6f (Gch) part of the fluorophore, as indicated, in basal (BC) or high (HC) Ca2+ media and in X. laevis oocytes with no EGTA

| D1 | D1a | D1b | D2 | D2a | D2b | N | Figure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | Rch | 8 ± 0.25 | 7 (70%) | 12 (30%) | – | – | – | 248 | Fig. 1 |

| Gch/BC | 9 ± 1 | 6 (84%) | 30 (16%) | 305 ± 12 | 271 (92%) | 698 (8%) | 185 | Fig. 2 | |

| Gch/HC | 27 ± 3 | 9 (34%) | 37 (66%) | 374 ± 33 | 236 (63%) | 605 (37%) | 49 | Fig. 3 | |

| X. laevis | 24 ± 1 | 15 (56%) | 36 (44%) | 434 ± 14 | 372 (77%) | 644 (23%) | 107 | Fig. 4 |

The diffusion coefficients are expressed in μm2/s as mean value ± SE for D1 and D2 or mean value (proportion of distribution) for D1a, D1b, D2a, and D2b.

The experiments of Fig. 5 (Table 2) were done with enough EGTA so that this buffer could be the “main competitor” with the dye for Ca2+. In this way, a meaningful comparison between the experimental results and the theoretical ones obtained with the simple Ca2+-dye-EGTA model described in the Supporting materials and methods could be done. Thus, varying [EGTA], we can analyze whether the experimentally derived coefficients are free or effective and to what extent the latter differ from the free ones. Comparing the second largest coefficient, D2 (circles), obtained in the experiments with low (Fig. 5, A and C) and high (Fig. 5, B and D) [Fluo8], we observe that it behaves similarly to the theoretical coefficient, Def1 (blue curve in Fig. 5, A and C) and to Def3 (green curve in Fig. 5, B and D). Notice that, with increasing [EGTA], Def1 approaches the EGTA-free diffusion coefficient (227 μm2/s, DEGTA from Table 1 rescaled by the factor 0.56, as explained in Results) in Fig. 5 A and Def3 approaches the free diffusion of Fluo8 (48 μm2/s, DFluo8 from Table 1 rescaled by the factor 0.48 or 56 μm2/s if the rescaling factor, 0.56, is used) in Fig. 5 B. This indicates that the set of diffusive timescales that are obtained with the experiments changes depending on the competition between the buffers and the dye, probably because the weight with which they contribute to the ACF also depends on this competition and thus are more or less detectable by the fitting procedure. This occurs on top of the dependence of each effective coefficient with the concentrations (e.g., the dependence with [EGTA] in Fig. 5). Thus, buffer composition affects both the values that the effective coefficients take on and which coefficients can be estimated with the experiments. This highlights the two main problems for the interpretation of the results of Table 3: 1) how to identify the coefficients derived from the fits with those of the actual system and 2) whether the fitted coefficients correspond to free or effective diffusion coefficients. The experiments of Fig. 5 allow us to obtain a consistent interpretation of the largest coefficient, D2, derived in the experiments of Fig. 4. The competing effects between the dye and the Ca2+ buffers can vary from cell to cell and between regions of a cell. Differences in buffer composition can then be the cause for the large variability of the experimentally derived coefficients of Table 3. As discussed in what follows, this is not the only source of variability.

The largest experimentally determined coefficient of Fig. 5 A, D3 (diamonds), increases with [EGTA] as the largest effective coefficient of the theoretical model, Def2. With increasing [EGTA], Def2 approaches the free Ca2+ diffusion coefficient DCa, which is the largest coefficient of the problem. We could thus consider that the value D3 = (425 ± 18) μm2/s, obtained for the largest [EGTA] in these experiments (see Table 2), is an estimate of DCa in the cytosol of oocytes. How do we reconcile this estimate with the fact that the largest coefficient derived from the experiments performed in oocytes with no EGTA (see Fig. 4 C) was much bigger in a significant fraction of the experiments? As mentioned before, the histogram of Fig. 4 C is best approximated by a bimodal distribution with subpopulations of means, 372 and 644 μm2/s, embracing 77 and 23% of the data (see fourth row in Table 3). This variability is much larger than the one that changes in buffer composition cause on the largest determined coefficient of Fig. 5. Namely, the experimental coefficient, D3, stays close to the theoretical one, Def2, which differs by less than ∼15% with respect to the free coefficient, DCa, for all the concentrations, [EGTA], and the two dye concentrations probed in the experiments of Fig. 5. Assuming that the Stokes-Einstein relation between viscosity and diffusivity holds, we can associate the variability of D2 in Fig. 4 C mostly to changes in viscosity, which, as already mentioned, would imply changes in the value of the free diffusion coefficients. Given that DCa = 760 μm2/s in aqueous solutions (61), if we consider that the values 372 and 644 μm2/s are within 15% of DCa in different regions of the cytosol, we then conclude that cytosolic viscosity could approximately vary between 2 and 1.2 times that of water. This variability, 1.2/2 ∼ 0.6, is consistent with the one observed in the results derived from the experiments in yeast in which the emission coming from the SFmCherry part of the sensor was analyzed (first row in Table 3). Namely, we observe that the set of values obtained for the diffusion coefficient, D1, which should correspond to the free diffusion coefficient of the sensor protein, can also be divided in two populations with means 12 and 7 μm2/s, whose ratio is 7/12 ∼ 0.6. Viscosity variability could then explain the wide, nonsymmetric distribution of the largest diffusion coefficient obtained in the experiments of Fig. 4. The results of Fig. 5 A were obtained over fewer experiments than those of Fig. 4. Thus, it is more likely that they correspond to values DCa within the subpopulation of Fig. 4 C of larger probability, i.e., the one with mean, 372 μm2/s. As shown in the Supporting materials and methods, the estimate, 372 μm2/s, falls very close to the theoretical curve Def3 of Fig. 5 A (red line), which approaches DCa = (425 ± 18) μm2/s with increasing [EGTA]. This provides further support to the conclusion that the experimentally determined coefficient, D2, of Fig. 4 (fourth row in Table 3) is very close (within ∼15%) to the free Ca2+ diffusion coefficient in the cytosol, and the variability among the estimated values, particularly between the means of each subpopulation, is mostly due to changes in cytosolic viscosity. It is important to note that the means over both populations are larger than the estimate, DCa = 220 μm2/s, of Allbritton et al. (16). It has been observed that the cytosol is a complex liquid that is not characterized by a single viscosity (62, 63, 64, 65, 66), with “sensed” values that depend on the size of the diffusive particles, which, for small ones, vary between ∼1.3 and 3 times the viscosity of water (65), similar to the 1.2–2 range that we derived from our experiments. Our results are also consistent with those of Rienzo et al. (68), which revealed that, in the cytosol, molecules diffuse freely with a coefficient as the one in a dilute solution at short scales.

A large variability is also observed among the values of the largest coefficient, D2, derived from the two types of experiments performed in S. cerevisiae in which the emission from the GCaMP6f part of the sensor was excited (Gch) (Figs. 2 and 3). The D2 variability in Figs. 2 C and 3 C, however, is slightly smaller than in Fig. 4 C. It is also smaller than the D1 variability observed in the experiments in which the fluorescence was collected in the Rch (Fig. 1 B), which is due to changes in cytosolic viscosity. The latter is reflected in that the ratio between the means over each population into which the values, D2, can be divided is D2a/D2b ∼ 0.39 and D2a/D2b ∼ 0.39 for the Gch/BC and Gch/HC experiments, respectively, whereas it is D1a/D1b ∼ 0.6 in the Rch experiments (Table 3). This is an indication that the coefficient, D2, obtained in the Gch experiments performed in S. cerevisiae might correspond to an effective coefficient that is further apart from DCa than in the experiments performed in oocytes. This is consistent with the observation that the means over each subpopulation, D2a and D2b, decrease with increasing Ca2+ (see Table 3), a behavior that has been observed in the largest coefficient derived in the experiments performed in aqueous solutions presented in Fig. 7 of Villarruel and Dawson (50). The means, D2b, over the subpopulations with the largest values obtained in the Gch/BC and Gch/HC experiments in S. cerevisiae (698 and 605 μm2/s, respectively), differ by less than 10% with respect to the value obtained in oocytes, D2b = 644 μm2/s. The means, D2a, over the subpopulations with the lowest values, on the other hand (271 and 236 μm2/s for Gch/BC and Gch/HC, respectively), differ by ∼30% with respect to the value obtained in oocytes, D2a = 372 μm2/s. It seems as if the highest end of the D2 distribution in S. cerevisiae is closer to DCa than the lowest one. This observation can be explained if we assume that the buffer composition in S. cerevisiae is such that the largest experimentally estimated coefficient corresponds to a different effective coefficient depending on the probed region of the cytosol (as illustrated by the transition observed in the second largest coefficient between Fig. 5, A and B). This is consistent with the fact that, when increasing Ca2+ in the bath, the means, D2a and D2b, do not vary as much as the relative probability of obtaining a diffusion coefficient within each subpopulation (the relative weights). This marked change in the relative weights can also be reflecting that it is not only the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that changes between the experiments with low and high Ca2+ bath but also the internal state of the cell (55). Another possibility is that these subpopulations can still be split once more, something that we will explore in future works.

We now analyze the smallest coefficient, D1, derived from the experiments in oocytes and the ones in yeast observed in the Gch. For the latter, both in the cases of basal (BC) or high (HC) Ca2+ media, the set of D1 values can be grouped in two subpopulations using the Akaike criterion. The means of one subpopulation (D1a, Gch/BC and Gch/HC in Table 3) are similar to the free diffusion of the sensor estimated from the observations in the Rch, 6–9 μm2/s (D1 or D1a, Rch, in Table 3). This gives a further validation to the estimate we obtained of the free sensor diffusion coefficient. The mean and the proportion of the other subpopulation, D1b, increase with [Ca2+] (compare the BC and the HC cases in Table 3). Thus, D1b most likely corresponds to an effective coefficient that is a concentration-dependent weighted average of the free coefficients of buffers, fluorophore, and Ca2+. In the case of X. laevis oocytes, the values, D1, derived from the fittings can be grouped into two subpopulations following the Akaike criterion as well. 56% of the data corresponded to a distribution centered around 15 μm2/s and the other 44% to a distribution centered around 36 μm2/s (Table 3). Given the results of Fig. 5 (see also Table 2), we can interpret these coefficients as effective ones that depend on the free coefficient of the dye (DFluo8 ∼50–60 μm2/s in the cytosol using the conversion factor from aqueous solution derived from Fig. 5, A and B) and on the coefficients of slower or immobile Ca2+ buffers.

Summarizing, the experiments performed in X. laevis oocytes and in S. cerevisiae that we have presented in this work show that the free diffusion coefficient of Ca2+ in the cytosol of living cells, DCa, is typically larger than previously assumed (∼220 μm2/s) and that it can vary over a very wide range of values in a similar way as has been observed for the cytoplasmic viscosity. Given the experiments performed in oocytes for which we have a better indication that one of the derived coefficients is close enough to DCa, we conclude that DCa varies around ∼400 μm2/s in most cases. There are certain instances, however, at which the Ca2+ cytosolic free diffusion can occur at approximately the same rate as in dilute aqueous solutions, ∼650 μm2/s. The implications of the latter for signaling will depend on the lengthscale over which such a high diffusion rate could be maintained. Further studies are necessary to analyze this aspect.

Author contributions

S.P.D. and C.V. participated in the oocytes experimental design and data interpretation. P.S.A. and C.V. participated in the yeast experimental design and data interpretation. C.V. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.P.D. supervised the project. C.V. and S.P.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sivaraj Sivaramakrishnan who provided the long linker sequence, Dr. Gabriela Amodeo who provided the X. laevis oocytes, Nahuel Tarkowski for help with some yeast experiments, and Dr. Lorena Sigaut for help with Förster resonance energy transfer efficiency experiments.

This research has been supported by Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBACyT 20020170100482BA) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2015-3824 and PICT 2018-02026 to S.P.D. and PICT 2017-0854 to P.S.A.). P.S.A. and S.P.D. are members of Carrera del Investigador Científico.

Editor: Alberto Diaspro.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.08.019.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Berridge M.J., Bootman M.D., Lipp P. Calcium--a life and death signal. Nature. 1998;395:645–648. doi: 10.1038/27094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei C., Wang X., Cheng H. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature. 2009;457:901–905. doi: 10.1038/nature07577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurley K., Tovey S.C., Falcke M. Reliable encoding of stimulus intensities within random sequences of intracellular Ca2+ spikes. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra59. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kniss-James A.S., Rivet C.A., Kemp M.L. Single-cell resolution of intracellular T cell Ca2+ dynamics in response to frequency-based H2O2 stimulation. Integr. Biol. 2017;9:238–247. doi: 10.1039/c6ib00186f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt H., Tilūnaitė A., Crampin E.J. Ca2+ release via IP3 receptors shapes the cardiac Ca2+ transient for hypertrophic signaling. Biophys. J. 2020;119:1178–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzuto R., De Stefani D., Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:566–578. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui J., Kaandorp J.A., Filatov M.V. Calcium homeostasis and signaling in yeast cells and cardiac myocytes. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:1137–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange M., Peiter E. Calcium transport proteins in fungi: the phylogenetic diversity of their relevance for growth, virulence, and stress resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2020;10:3100. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwaller B. Cytosolic Ca2+ buffers. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a004051. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dargan S.L., Schwaller B., Parker I. Spatiotemporal patterning of IP3-mediated Ca2+ signals in Xenopus oocytes by Ca2+-binding proteins. J. Physiol. 2004;556:447–461. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraiman D., Dawson S.P. Buffer regulation of calcium puff sequences. Phys. Biol. 2014;11:016007. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/11/1/016007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piegari E., Lopez L.F., Ponce Dawson S. Using two dyes to observe the competition of Ca2+ trapping mechanisms and their effect on intracellular Ca2+ signals. Phys. Biol. 2018;15:066006. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/aac922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einstein A. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1989. The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 2, Translated by Anna Beck, consultant Peter Havas. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg H.C. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1993. Random Walks in Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naraghi M., Neher E. Linearized buffered Ca2+ diffusion in microdomains and its implications for calculation of [Ca2+] at the mouth of a calcium channel. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6961–6973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allbritton N.L., Meyer T., Stryer L. Range of messenger action of calcium ion and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Science. 1992;258:1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.1465619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pando B., Dawson S.P., Pearson J.E. Messages diffuse faster than messengers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5338–5342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509576103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carbó N., Tarkowski N., Aguilar P.S. Sexual pheromone modulates the frequency of cytosolic Ca2+ bursts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:501–510. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flegg M.B., Rüdiger S., Erban R. Diffusive spatio-temporal noise in a first-passage time model for intracellular calcium release. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:154103. doi: 10.1063/1.4796417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDowell C.J., Buschman T.J. Low-dimensional spatiotemporal dynamics underlie cortex-wide neural activity. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:2665–2680.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson S.P., Keizer J., Pearson J.E. Fire-diffuse-fire model of dynamics of intracellular calcium waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6060–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voorsluijs V., Dawson S.P., Dupont G. Deterministic limit of intracellular calcium spikes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;122:088101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.088101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piegari E., Ponce Dawson S. Functional Ca2+ channels between channel clusters are necessary for the propagation of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ waves. Math. Comput. Appl. 2019;24:61. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lock J.T., Parker I. IP3 mediated global Ca2+ signals arise through two temporally and spatially distinct modes of Ca2+ release. eLife. 2020;9:e55008. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujii Y., Maekawa S., Morita M. Astrocyte calcium waves propagate proximally by gap junction and distally by extracellular diffusion of ATP released from volume-regulated anion channels. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13115. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13243-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denizot A., Arizono M., Berry H. Simulation of calcium signaling in fine astrocytic processes: effect of spatial properties on spontaneous activity. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bezprozvanny I. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foskett J.K., White C., Mak D.O. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor C.W., Tovey S.C. IP(3) receptors: toward understanding their activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a004010. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;245:C1–C14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson G.D., Ellefsen K.L., Parker I. Hindered cytoplasmic diffusion of inositol trisphosphate restricts its cellular range of action. Sci. Signal. 2016;9:ra108. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aag1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denis V., Cyert M.S. Internal Ca(2+) release in yeast is triggered by hypertonic shock and mediated by a TRP channel homologue. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:29–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viladevall L., Serrano R., Ariño J. Characterization of the calcium-mediated response to alkaline stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43614–43624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham K.W. Acidic calcium stores of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyert M.S., Philpott C.C. Regulation of cation balance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;193:677–713. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.147207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santamaria F., Wils S., Augustine G.J. Anomalous diffusion in Purkinje cell dendrites caused by spines. Neuron. 2006;52:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biess A., Korkotian E., Holcman D. Barriers to diffusion in dendrites and estimation of calcium spread following synaptic inputs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura A.C., Bruno L., Dawson S.P. A model-independent algorithm to derive Ca2+ fluxes underlying local cytosolic Ca2+ transients. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2403–2421. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruno L., Solovey G., Dawson S.P. Quantifying calcium fluxes underlying calcium puffs in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piegari E., Lopez L., Ponce Dawson S. Fluorescence fluctuations and equivalence classes of Ca2+ imaging experiments. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magde D., Elson E., Webb W.W. Thermodynamic fluctuations in a reacting system—measurement by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972;29:705–708. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haustein E., Schwille P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: novel variations of an established technique. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Arish A., Porcher A., Fradin C. High mobility of bicoid captured by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: implication for the rapid establishment of its gradient. Biophys. J. 2010;99:L33–L35. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta A., Phang I.Y., Wohland T. To hop or not to hop: exceptions in the FCS diffusion law. Biophys. J. 2020;118:2434–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paredes R.M., Etzler J.C., Lechleiter J.D. Chemical calcium indicators. Methods. 2008;46:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mank M., Griesbeck O. Genetically encoded calcium indicators. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1550–1564. doi: 10.1021/cr078213v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piegari E., Sigaut L., Ponce Dawson S. Ca2+ images obtained in different experimental conditions shed light on the spatial distribution of IP3 receptors that underlie Ca2+ puffs. Cell Calcium. 2015;57:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sigaut L., Villarruel C., Ponce Dawson S. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy experiments to quantify free diffusion coefficients in reaction-diffusion systems: the case of Ca∧2+ and its dyes. Phys. Rev. E. 2017;95:062408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.95.062408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigaut L., Villarruel C., Ponce Dawson S. FCS experiments to quantify Ca2+ diffusion and its interaction with buffers. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;146:104203. doi: 10.1063/1.4977586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villarruel C., Dawson S.P. Quantification of fluctuations from fluorescence correlation spectroscopy experiments in reaction-diffusion systems. Phys. Rev. E. 2020;102:052407. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.102.052407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van den Ent F., Löwe J. RF cloning: a restriction-free method for inserting target genes into plasmids. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2006;67:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sivaramakrishnan S., Spudich J.A. Systematic control of protein interaction using a modular ER/K α-helix linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20467–20472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116066108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swanson C.J., Sivaramakrishnan S. Harnessing the unique structural properties of isolated α-helices. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:25460–25467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.583906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho J.-H., Swanson C.J., Chow R.H. The GCaMP-R family of genetically encoded ratiometric calcium indicators. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:1066–1074. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai L., Dalal C.K., Elowitz M.B. Frequency-modulated nuclear localization bursts coordinate gene regulation. Nature. 2008;455:485–490. doi: 10.1038/nature07292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Culbertson C.T., Jacobson S.C., Michael Ramsey J. Diffusion coefficient measurements in microfluidic devices. Talanta. 2002;56:365–373. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(01)00602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gennerich A., Schild D. Anisotropic diffusion in mitral cell dendrites revealed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2002;83:510–522. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The MathWorks Inc . The MathWorks Inc.; Natick, MA: 2010. MATLAB version 7.10.0 (R2010a) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krichevsky O., Bonnet G. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: the technique and its applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2002;65:251–297. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akaike H. In: Breakthroughs in Statistics, Springer Series in Statistics (Perspectives in Statistics) Kotz S., Johnson N., editors. Springer US; 1992. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qin D.Y., Yoshida A., Noma A. Limitations due to unstirred layers in measuring channel response of excised membrane patch using rapid solution exchange methods. Jpn. J. Physiol. 1991;41:333–339. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.41.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blum J.J., Lawler G., Shin I. Effect of cytoskeletal geometry on intracellular diffusion. Biophys. J. 1989;56:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elowitz M.B., Surette M.G., Leibler S. Protein mobility in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:197–203. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.197-203.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szymański J., Patkowski A., Holyst R. Diffusion and viscosity in a crowded environment: from nano- to macroscale. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:25593–25597. doi: 10.1021/jp0666784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalwarczyk T., Zibacz N., Hołyst R. Comparative analysis of viscosity of complex liquids and cytoplasm of mammalian cells at the nanoscale. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2157–2163. doi: 10.1021/nl2008218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sozanski K., Wisniewska A., Holyst R. Motion of molecular probes and viscosity scaling in polyelectrolyte solutions at physiological ionic strength. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wood C., Huff J., Wiegraebe W. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy as tool for high-content-screening in yeast (HCS-FCS) Single Molecule Spectroscopy and Imaging IV, International Society for Optics and Photonics. 2011;7905:79050H. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Rienzo C., Piazza V., Cardarelli F. Probing short-range protein Brownian motion in the cytoplasm of living cells. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5891. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.