Abstract

Background

Team-based learning has been utilized inside and outside of medical education with success. Its use in bioethics education—particularly in graduate medical education—has been limited, despite its proven pedagogical strength and the critical importance of ethics and professionalism.

Activity

From 2015–2018, we created and administered 10 TBL bioethics modular exercises using L. Dee Fink’s “Principles of Significant Learning” and the evidence-based methodology of TBL (with some modifications, given the nature of graduate medical education) to pediatric residents. We evaluated the TBL curriculum and report satisfaction scores and qualitative thematic analysis of strengths and weaknesses.

Results and Discussion

Pediatric residents, despite a perception of “curricular squeeze” and lack of interest in ethics, were highly engaged and satisfied with a TBL-only-based bioethics curriculum. We were able to successfully adapt the TBL structure to the situational factors surrounding the rigors and unpredictable nature of clinical graduate education. We offer four “Lessons Learned” for creating and implementing TBL exercises in graduate medical education. TBL can be used in bioethics education successfully, not just for individual exercises, but also to create a comprehensive ethics curriculum.

Keywords: Bioethics, Ethics education, Medical education, Graduate medical education, Team-based learning, Curricular development

Background

Medical Ethics Education in Undergraduate and Graduate Medical Education

Bioethics education has been, for several decades, a theoretical priority in undergraduate medical education. Medical schools in the USA universally accept the idea that a bioethics curriculum is an essential component of medical education, particularly in the pre-clinical years. All medical schools in the USA, for example, contain an ethics component within the first 2 years of medical school [1]. Surveys of ethics syllabi from medical schools in the USA and Canada have shown that bioethics courses focus on a discrete group of “core concepts”—the “nuts and bolts” of a basic bioethics education [2–4]. However, as Alastair Campbell and colleagues pointed out more than a decade ago, few studies measuring outcomes, such as learning and retention, have demonstrated the educational value of a bioethics course in the pre-clinical years in medical school [5], and few to date have shown modest gains in cognitive knowledge in medical ethics [6]. In graduate medical education (GME), different specialties have recognized the need for medical ethics education in residency, since few effective curricula exist in the bioethics educational literature [7–9]. In pediatrics specifically, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has tasked pediatric residency programs to provide a structured curriculum in medical ethics and professionalism [10]. Furthermore, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) lists a wide range of learning outcomes in their content specifications for the pediatric board exam, highlighting the need for a rigorous education in ethics [11]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has also published a 20- module, online, case-based bioethics curricula, complete with teaching guides and written by content experts in pediatric bioethics [12]. Though ambitious in scale and laudatory in its aims, one survey of program directors found it is used by only 15% of the 113 programs surveyed [13], and no published data exists on its effectiveness. Furthermore, the AAP online curriculum involves working through ethical cases, which may require multiple trained faculty to facilitate, and, similar to other online curricula, employs a more passive model of learning.

Barriers to Teaching Bioethics in Residency

Despite requirements to train and evaluate residents in ethics and professionalism, there have been several barriers to teaching and ensuring competency in these areas. A recent systematic review of effectiveness of bioethics education found both low numbers of studies and subjects, and considerable variation in content and rigor [14]. Another review of pediatric ethics education concluded that “existing training regimens are insufficient to meet the real-life ethical challenges experienced in actual practice, particularly with respect to palliative care and the commission of clinical errors” [15]. As early as 1997, Diekema and Shugerman identified barriers to ethics education in pediatric residency. “These barriers included time constraints of faculty and residents, scheduling difficulties and lack of continuity, attitudes of residents toward the material, and inadequate ethics training for faculty” [16]. Cook and her colleagues, following Lang et al. [17] noted that while the majority of pediatric residency programs offer clinical ethics, research ethics, or professionalism training, barriers exist to effective implementation. Lack of awareness of available resources was evident in the program directors’ responses to the curricular survey on ethics. Furthermore, program directors specifically identified: (1) crowding in the curriculum—what we call “curricular squeeze”; (2) lack of faculty expertise; (3) lack of faculty interest; (4) lack of trainee interest; and (5) lack of administrative support [13]. A more recent review by Martakis and colleagues showed similar barriers [18].

Our own experience in teaching and clinical care at one of the largest children’s hospitals in the USA suggests that other challenging “situational factors” exist including (1) a relative lack of “outcomes” data in bioethics education; (2) perception of relevance—given competing residency requirements in other competencies, and lack of dedicated time to ethics education; (3) the subjective-objective tension and subsequent ambiguity present in ethical discussions, making assessment more challenging; (4) a lack of trained faculty, which makes “quality control” problematic; (5) varying schedules/rotations of trainees; and (6) lack of incentives to study ethics in residency (in contrast to medical school, where learners have higher-stakes, summative assessments that count toward a grade) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Barriers to teaching ethics education in pediatric residency (“situational factors”)

| Empirical (surveyed) barriers (Cook et al., 2013) | Other potential pedagogical barriers |

|---|---|

| Lack of awareness of available resources | Lack of outcomes data in bioethics education |

| Curricular squeeze | Perception of relevance given other duties |

| Lack of faculty expertise | Inherent ambiguity in ethics/moral decision making |

| Lack of faculty interest | Quality control in facilitation |

| Lack of trainee interest | Varying schedules of residents |

| Lack of administrative support | Lack of incentives to learn ethics in residency (no grades) |

Such barriers have an effect. Cook and her colleagues showed that more than half (53%) of the program directors who responded to their survey had no formal assessment of clinical ethics at all. Methods to assess residents included observation (50%), examination (5%), simulated patients (about 12%), and “other” (about 5%), but the efficacy of these modalities has been difficult to ascertain [13].

The Use of Team-Based Learning in Bioethics Education

In designing a pediatric ethics curriculum, aware of the aforementioned barriers to teaching, and desiring a modality that had evidence-based results, we decided to build a curriculum that utilized team-based learning (TBL). We utilized Michaelson and Sweet’s now-classic description of TBL as the basis of our curricular planning [19], as well as Parmelee and colleagues guide to creating TBL exercises [20]. TBLs can assess the learner’s ability to “know” (IRAT/GRAT) and to “know how” (Group application exercise (GaPP)) in a setting which is not costly or faculty-intensive.

The use of TBL in medical schools in the USA is growing, and its effectiveness has been demonstrated in the literature in both clinical [21] and pre-clinical settings [22, 23]. Several systematic reviews have showed the effectiveness of TBL approaches in education, including in business, nursing, and other health professions [24–26]. In particular, these studies showed that compared with more traditional modalities, learner satisfaction and active learning (engagement) were higher. More recently, TBL approaches have been utilized effectively in graduate medical education in areas as diverse as evidence-based medicine [27], internal medicine [28], primary care [29], and even pathology [30]. Poeppelman and colleagues [31] reviewed the use of TBL in GME and concluded that its use was feasible in educating residents—but pointed to similar barriers previously noted: faculty preparation and time; heterogeneity of resident education and attendance; outcomes measures; and incentives to influence the preparatory work essential to TBL exercises.

Interestingly, in our own review of the literature, we found only 2 studies that utilized TBL to teach ethics (one was a small South Korean study of first year medical students, and the other involved research ethics) [32–34]; no studies that utilized TBL to teach pediatric residents; and no studies that showed the effectiveness of teaching residents bioethics—pediatric or otherwise—using TBL.

Our hypothesis was that a TBL-based bioethics curricula could be designed and executed for pediatric residents that would show high satisfaction, and increased engagement and practice in confronting ethical dilemmas. Our choice to use TBL in bioethics education in residency would therefore fill a large, much-needed gap in the TBL and medical ethics education literature.

Methods

Creating an Ethics Educational Task Force

While our TBL bioethics curriculum is on-going, the methods and qualitative results described below cover the period from 2015 to 2018. We began our process in 2015 with significant buy-in from the residency program director (co-author JM), and departmental chair, who wanted to prioritize ethics and professionalism education at our institution. A task force was created with clinical content experts in emergency medicine (co-author SS), neonatology (co-author SW), hospital medicine (co-authors AF, RK), palliative medicine (co-author LH), nephrology (JM), and ambulatory medicine (AF). Two members had extensive experience in medical education (JM, AF), and two in bioethics (AF, SW). The task force began in December 2014, and the first module of the TBL exercise was implemented in July of 2015.

Theoretical Grounding

Significant Learning

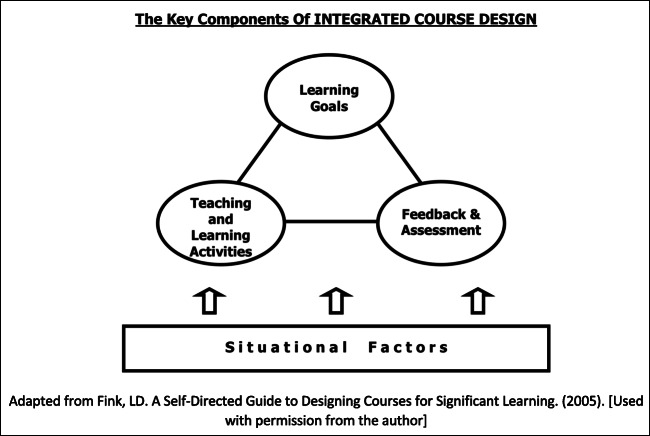

In designing our TBL-based ethics curricula for residents, we wanted to ensure that both the curriculum as a whole and the specific modality (TBL) were grounded in peer-reviewed, published educational theory for adult learners. To that end, planning the curricula began utilizing L. Dee Fink’s principles of “Significant Learning” [34, 35], a well-known approach to curricular planning that utilizes an “integrated course design” to achieve desired learning outcomes. Fink notes that “situational factors” (such as the educational barriers in Table 1) must be taken into account when designing learning goals, teaching and learning activities, and assessments (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

LD Fink’s integrated course design. Adapted from Fink, LD. A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning (2005) (used with permission from the author)

This insight allowed us to make certain decisions regarding the structure of the TBL (and how much we could deviate from it), as well as how and when to administer each module, and incentives to encourage participation (since residents do not receive “grades”). For example, because TBL exercises utilize a “flipped classroom” approach, a small number of faculty with pertinent clinical experience could facilitate a large group of learners—since most of the learning takes place in discussion groups among trainees. This ameliorated one educational barrier to teaching ethics that Cook and colleagues pointed to—“lack of faculty expertise.”

In another example of how the theoretical grounding aided our adaptation to residency education, we chose to utilize the Individual Readiness Assurance Test (IRAT) and Group Readiness Assurance Test (GRAT) multiple-choice assessments formatively, and not to grade the group application exercises in the TBL at all. Making the assessments low stakes and without a “right answer” was critical to allowing open and transparent ethics discussions, and emphasizing that, while answers were important for pediatric board preparation, the key to the exercise was collaboration, tolerance of ambiguity, professional communication, and respect for diversity of ethical views.

In resident education, all teachers must contend with the demanding, heterogeneous, and stressful schedule of the trainees. To address this “situational factor,” the residency program director (JM) made it clear that attendance at ethics educational sessions was required (like all resident lectures), but our goal was to administer approximately 3–4 per TBL exercises per year—with the goal of residents attending approximately 6–9 of those (out of 10) in a 3–4-year residency. Ethics education also occurred at mandatory resident retreats. This elevated the significance of resident ethics education and improved attendance. In the first years of administration, when attendance was taken for all resident lectures (not just bioethics), an extra “lecture credit” was given to residents who attended the ethics sessions, thus further incentivizing participation.

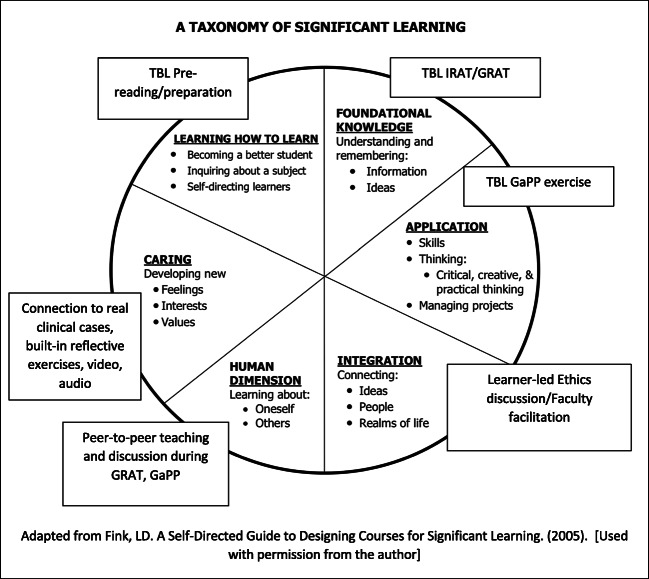

Fink also created a “Taxonomy of Significant Learning” [34]. We adapted this taxonomy to plan our TBL exercises and ensure an integrated approach to significant learning was employed. We used bioethics and pediatric literature, paper cases, social media, video, and audio in designing a multimodal TBL experience (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

LD Fink’s taxonomy of significant learning. Adapted from Fink, LD. A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning (2005) (used with permission from the author)

Learning Outcomes and Topics

L. Dee Fink’s Significant Learning approach also employs what he calls “Backwards Design”—starting with the learning outcomes (“what do you want the learner to be able to do?”), and designing teaching and learning methods and assessments afterward [34]. This is particularly important in residency, when the emphasis is on ethical clinical care (“know how”) rather than simply “knowing.” We therefore adopted the core learning outcomes in ethics as outlined by the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) [11] to design our TBL-based ethics curriculum for residents. Based on these learning outcomes, our task force of expert faculty identified ten vital ethics topics for residency education that would form the basis for our TBL exercises (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pediatric bioethics TBL topics

| 1. Introduction to medical ethics and the Four Box Method | |

| 2. Assent and consent | |

| 3. Professionalism and social media | |

| 4. Neonatal and perinatal ethics | |

| 5. Spirituality in medicine | |

| 6. Pediatric palliative care | |

| 7. Interpersonal relationships | |

| 8. Pediatric decision making and the best interest standard | |

| 9. Child abuse, intimate partner violence, and toxic stress | |

| 10. Pediatric research ethics |

TBL Design

This curriculum outline was evaluated by the Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt from review. The TBL ethics curriculum was designed for pediatric residents at a large, free standing tertiary care pediatric hospital with approximately 50 residents per class. Each of the 10 TBL sessions was approximately 1.5 h in length, with the last 5 min reserved for evaluations of the teaching and learning exercise to be completed by residents. Residents could theoretically experience the entire curriculum over a 3-year period, since ethics TBLs given approximately three to four times per year during pre-designated, protected resident educational time.

Advance Preparation Resources

Session objectives and preparatory resources were electronically distributed 1 week ahead of the in-class TBL activity. Students were reminded of the required nature of the TBL, as well as the incentives for attendance. Some examples of preparatory resources included a written summary of ethical principles or concepts, informed by the peer-reviewed literature; relevant scholarly articles in bioethics; or American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statements on ethical issues.

Team Formation

Residents were randomly assigned to TBL groups upon entering the in-class activity by being given a number from one of the faculty facilitators. Each number corresponded to a group table in the room. The individuals were instructed to sit at the table corresponding to the number they received.

Readiness Assurance Process

Each individual resident completed an Individual Readiness Assessment Test (IRAT) of 6–8 peer-reviewed multiple-choice questions based on pre-reading material. The time allotted was 10 min. The same Readiness Assurance Test was administered to the randomized groups (GRAT), with an allotted time of 15–20 min. The GRAT discussion period was closed-book, without use of any outside resources (internet, handouts, etc.).

Immediate feedback

Immediate feedback was provided during the GRAT process. The procedure used to provide immediate feedback was “scratch-off” Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique (IFAT) cards. At the end, the facilitator(s) led the whole group of residents in a highly interactive, engaged discussion by going through the challenging questions raised and allowing students to discuss/debate answers.

Group Application Activities

The group application exercises were composed of case vignettes in various formats, such as in written form, live action (role play), or in video or audio format. Only one case vignette was used for each session. Each case vignette had questions to be discussed and answered by each team in small groups, utilizing a well-known ethics tool called the “Four Box Method” [36]. The use of this tool was taught during the introductory TBL exercise, then practiced throughout the curriculum. Then, teams were asked to simultaneously report their answers to the larger group. During this time, teams are given the opportunity to debate, defend, and appraise their answers with expert faculty facilitation. One to five faculty (depending on availability) were present for each of the 10 TBL sessions.

True patient encounters provided the basis for application exercises. We utilized and adapted ethical situations from “classical” pediatric ethics cases, news media, local ethics committee consults, research experiences, and the personal experiences of the team leaders. We anonymized the patients and other participants, but this allowed the residents participating in the TBL to have “real-world” examples to engage in and experience.

TBL Logistical Preparation

Faculty and Student Training/Orientation

Faculty facilitators were given several hours training in facilitating TBL exercises by the chair of the ethics educational task force (AF) who is an expert educator in TBL. TBLs are also delivered frequently in the curriculum of both the local medical school associated with this pediatric residency, and the pediatric residency itself. Many learners were therefore familiar with the basics of TBL exercises. However, a brief 5-min introduction to the TBL process was also given at the beginning of the first several TBLs to ensure learner understanding of the process. This was particularly important since residents would be participating in TBL exercises over the entire course of their residency.

Additional Logistical Resources

Additional resources were also needed to ensure the flow of TBL exercises. Note that such resources are typical for most TBL exercises, whether the subject is bioethics or not. These included (1) access to audio-visual equipment to project presentations and play video or audio (if needed); (2) test booklets and answer sheets for the IRAT; (3) GRAT answer cards (“IFAT cards”); (4) table numbers, pencils, dry erase markers, lettered and color-coded answer cards for use in the GaPP exercise; and, more specifically for our ethics curricula, (5) a laminated “Four Box Method” worksheet where students could collectively write notes in each box while conducting their ethical analysis.

Assessment and Evaluation Strategy

Before the administration of our first TBL exercise, we developed an ethics knowledge-application pre-test, post-test, and question bank for IRAT questions. These questions were presented in American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) Board format after development and review by ABP question preparers at our institution. The multiple-choice questions had face validity since no prior residency ethics question bank was available and based on review by our faculty content experts in ethics, professionalism, and pediatric medicine.

Once the question bank was completed, a 20-question pre-test was created to define educational needs and establish baseline comprehension, as well as a post-test utilizing non-identical but same-subject questions to identify gains in cognitive knowledge. The pre-test was administered during the first TBL exercise to set up a baseline for resident knowledge. IRATs were graded individually, with one point for a correct answer and zero point for incorrect answers. GRATs were also graded for each group.

Groups received one point for a correct answer on the first try, 0.5 points for a correct answer on the second try, and no points for additional tries. The post-test was then given after the first 10 TBLS were completed.

Despite the fact that no “grades” were given that affected residency performance per se, we believe that residents were motivated to do well in our TBL exercises due to “intrinsic motivation”—such as prior conditioning for higher-stakes testing (as medical students and residents). In addition, Jeno and colleagues showed that TBL itself increases engagement (over lectures) through perceived competence and autonomy, and the desire for “self-determination” [37]. Quantitative data analysis for our TBL curricula is on-going, promising, and we intend to report and publish this data once fully finalized.

Results

Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Narrative Comments

For the purposes of this monograph, we have included a summary of qualitative data from an analysis of hand-written comments by residents (n = 369) after thematic analysis (Tables 3 and 4). Our data shows that, consistent with the literature in medical education in the sciences (cited above), engagement was extremely high (see Table 3). Residents found both the amount (52%) and specific content of the pediatric bioethical discussions (10%) highly satisfying. They enjoyed the case-based peer interaction facilitated by our expert faculty educators (12%). Finally, affirming L. Dee Fink’s approach to Significant Learning in curricular planning, residents specifically mentioned multi-modal forms of learning and application as positives—including video (6%), role-play (3%), and debate (3%). All of these positive qualities centered around better, more effective engagement through TBL use, and seemed to overcome some of the perceived barriers to ethics education in residency.

Table 3.

Summary of 10 most frequent positive themes for the bioethics TBL sessions

| Question: “Please name 1–2 things you found particularly valuable about this session.” (Multiple answers accepted/analyzed, n = 369 pediatric residents, 2015–2018) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Increased amount of discussion (general) | 127 | 52 |

| Interesting/relevant/helpful educational material (general) | 53 | 22 |

| Cases (interesting topic, discussion) | 30 | 12 |

| Discussion content (enjoyed discussing specific ethics subject material) | 25 | 10 |

| Team-based learning approach/working as a group | 23 | 10 |

| Involving experts/facilitators/attending’s was very helpful | 21 | 9 |

| Interesting/relevant/helpful educational material (specifically IRB exercise) | 15 | 6 |

| Video | 14 | 6 |

| Activity (specifically role-play) | 8 | 3 |

| Debate | 8 | 3 |

Table 4.

Summary of 10 most frequent negative themes for the bioethics TBL sessions

| Question: “Please name 1–2 ways this session can be improved.” (Multiple answers accepted/analyzed, n = 369 pediatric residents, 2015–2018) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Timing (stick to time limits, too, too long, too much time spent on one area) | 30 | 18 |

| More group discussion | 19 | 11 |

| Improving multiple-choice question wording/questions were confusing/too many questions/not enough questions/more challenging questions | 14 | 8 |

| Readings not necessary/less reading | 13 | 8 |

| More clear/structured discussion | 10 | 6 |

| Provide readings earlier | 9 | 5 |

| More variety of cases/examples | 9 | 5 |

| Too much time spent on IRB session/IRB lesson was repetitive | 8 | 5 |

| TBL format: IRAT was not applicable to lesson, IRAT/GRAT unnecessary, skip the quiz | 7 | 4 |

| Exclude video at the end/video not helpful | 7 | 4 |

Elements of the TBL curricula that residents viewed negatively were not surprising. These included timing/length of time (18%), the multiple-choice questions used in the IRAT/GRAT (8%), and readings (8%). Less seemed dissatisfied with the structure of TBL itself (4%). Interestingly, several “negative” comments were actually suggestions for enhancing elements of TBL, including more group discussion (11%), more cases (5%), and readings being given earlier so they could be completed (5%) (see Table 4).

Overall Satisfaction and Self-report of Pre-reading/Preparation

In addition, our data showed a high mean Likert scale rating for overall satisfaction across the 10 TBL modules of 4.42/5. Table 5 shows individual Likert satisfaction means for each subject area, as well as the percentage of students who reported completing the readings. This overall percentage was low (high of 47% (Neonatal and Perinatal Ethics) to a low of 14% (Child Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence, and Toxic Stress)), despite the witnessed and self-reported high level of engagement in the GRAT and application exercises.

Table 5.

Mean 5-point Likert satisfaction scores and self-reported pre-reading (n = 369)

| Satisfaction mean (1 = poor; 5 = excellent) | % Agree “I did the reading” |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1. Introduction to medical ethics and the Four Box Method | 4.5 | 36 |

| 2. Assent and consent | 4.5 | 30 |

| 3. Professionalism and social media | 4.3 | 15 |

| 4. Neonatal and perinatal ethics | 4.8 | 47 |

| 5. Spirituality in medicine | 4.8 | 33 |

| 6. Pediatric palliative care | 4.4 | 44 |

| 7. Interpersonal relationships | 4.3 | 14 |

| 8. Pediatric decision making and the best interest standard | 4.1 | 26 |

| 9. Child abuse, intimate partner violence, and toxic stress | 4.6 | 14 |

| 10. Research ethics | 3.9 | 17 |

| Total average | 4.42 | 27.6 |

Discussion

Our TBL-based pediatric ethics curriculum for residents, created using evidence-based educational theory and practice, shows promising results. Our curriculum demonstrates high resident satisfaction with the experience and high engagement. Predictably, residents least liked the amount of time spent taking multiple-choice assessments (even while low-stakes), and reading. Conversely, they indicated that they would have enjoyed a greater amount of time spent on discussion, and more time to practice and read content.

Important Lessons in Creating a Pediatric Ethics Curriculum

Several important lessons were learned from our successful program that could be utilized in implementing ethics curricula elsewhere.

Use Theoretically Grounded Methods

We recommend Fink’s 2005 curricular planning guide and worksheets as a “first step” in designing a TBL curricula in bioethics. The utilization of Significant Learning and a modified TBL format (e.g., non-graded GaPP and low-stakes IRAT/GRAT) in the creation of an ethics curriculum helped to overcome many practical and pedagogic barriers to teaching bioethics in residency. In particular, the critical importance of ethics to the practice of medicine and the nature of moral ambiguity in clinical ethics demands a curricular format that is flexible, serious, and open to a diversity of views in which learners feel free to discuss uncertainties and question norms. The TBL format is well suited to provide this learning environment. In developing the curriculum, the faculty team sought to create a content specific, applicable, and interactive medical ethics experience that also addressed multiple learning styles. The TBL structure has the ability to provide both and gave confidence to our curricular planning team that—given the data already available on the success of TBL—we could be successful teaching ethics despite the paucity of bioethics-specific data.

Make Content Relevant to Both Clinical Medicine and the Board Exam

Pediatric residents’ desire to pass the American Board of Pediatrics qualifying exam demands that residency educational content be specifically linked to the exam. The IRAT/GRAT portion of this TBL curricula allowed the instructors to both specifically address ABP content specifications in ethics and provide board review style questions, similar to questions that may be seen on the qualifying exam. This adds the short-term relevance that individual residents and program directors seek in ethics education.

Furthermore, residents (and faculty) also desire interactive and clinically applicable experiences that will prepare the learner for the realities of clinical medicine. Our team selected GaPP exercises with patients and experiences similar to those encountered by residents and attending physicians, avoiding more abstract ethical discussions that residents find unrelatable. The TBL format provides interaction between resident peer groups and the content expert leaders through conversation, not through static lectures. It also allows faculty facilitators to draw on their own experience to utilize real-life cases that are not necessarily dramatic—what Diekema and Shugerman called “zinger cases” [16].

Create a Multi-modal, Engaging Experience

The TBL curricula allow multiple learning style experiences, especially in the GaPP exercise. Teaching ethics should avoid the “sage on stage” lecture style that has historically been used. Even purely case-based ethics curricula (with no pre-exercise preparation, testing of readiness, immediate feedback, and engaged peer-to-peer teaching, as in TBL) can lead to an unstructured discussion and challenges in meeting learning outcomes. Individual work occurs during the pre-reading and IRAT. Highly engaged small group experiences occur during the GRAT and application exercises, where learners discuss among themselves and come to a conclusion first—before the “intrusion” of faculty opinions.

Especially in ethics, this TBL format has the advantage of allowing students the freedom to discuss sensitive opinions they might otherwise be reticent to bring up in front of attending physicians. Large group discussions with small didactic portions from faculty group leaders also occur during the GRAT and application exercises. Application exercises in TBL modules can be done in a variety of formats. We used paper cases, video, audio, role play, and even debates to help guide learners to meet the prescribed learning objectives. This allowed our curriculum to address multiple resident needs while providing high-quality medical ethics education. Our results support high resident engagement and satisfaction using varied formats for learning when applying ethical knowledge.

Incentivize Residents by “Meeting Them Where They Are”

Resident’s varied and demanding schedule needs special attention in planning an ethics curriculum, especially when competing competencies and subjects (e.g., cardiology and infectious disease), as well as clinical duties, can be perceived as “more important.” Most programs would find both mandated and graded ethics exercises problematic, and we agree. Therefore, our curricula made no “extra” participation demands on learners (e.g., they were required to attend all resident lectures or retreats, not just ethics). We also positively incentivized them by giving them lecture credit when they did come and allowing them to miss several modules as their schedule demanded. Over the course of 3 years, we hoped that residents would have participated in most of the modules. Finally, residents do respond to priorities set by the chair and program directors. It was imperative for the success of our ethics curricula that buy-in from the program and associate program directors, as well as the chair of pediatrics, be transparent. We suggest, for example, that reminders about the TBL preparation be sent from the program director him/herself to the residents, and that department chairs and division heads be invited to observe and even facilitate discussion.

Challenges Not Fully Met

Pre-reading

We continued to face several challenges during implementation of the TBL ethics curriculum. The first challenge resulted from residents failing to complete the pre-work (readings). Only 27% of residents on average reported completing the readings. Clearly, based on the qualitative responses from the residents, the readings also represented one of the least favorite parts of the TBL. We tried to address this issue in later TBL modules by limiting the number of articles required, using summaries of articles (written by faculty) instead of full articles, and, at times, giving them time just prior to the TBL to review the material. However, pre-reading was still low. This may simply be due to the nature of residency—residents are so busy with clinical care, and then with clinical self-directed learning that ethical reading may simply take a back seat. This is a problem, however, for all ethics education and will need to be studied further.

Attendance

The second major challenge was attendance at TBL ethics modules, a barrier anticipated by the extant literature on resident education. Residents on away rotations, night float, post-call, or on intensive care unit rotations were automatically excused. However, sometimes attendance still waned, despite the fact that all resident didactic sessions (ethics and non-ethics) were “required.” This was addressed in two ways. First, by positively reinforcing attendance through lecture “extra credit” (if residents attended ethics lectures, they could gain “double credit”) for others. Second, the program linked attendance at all resident didactics to utilization of resident book money, and professionalism scores on the pediatric milestones. This program rule was in place antecedent to the introduction of the ethics curriculum.

Later, attendance was improved by teaching ethics TBL sessions at activities in which an entire class of residents will be there—such as resident retreats.

Generalizability

Several limitations to the generalizability of this curriculum exist. Our residency program is large, allowing for enough participants to create several groups for each TBL. This may be challenging in smaller residency programs, although Edmunds and Brown have shown that small groups of as few as 6–8 are ideal, with some early studies showing that even groups of 3–4 can be effective [38]. We also have a core group of 6 faculty members with diverse clinical experience, experience in curricular design and implementation, a vested interest in professionalism education, and expertise in medical ethics who were able to help co-lead the TBL modules. While one advantage to TBL is that they can be run without formal ethics expertise, some questions generated by discussion will be more challenging. We do suggest that clinical faculty need to be present and actively engaged in facilitation (rather than non-clinical bioethics faculty alone) in order to bring practical experience and relevant knowledge to more complex medical scenarios that residents find themselves in. Finally, the inherent nature of limited time for pediatric residency education may make this curriculum difficult to implement, depending on the specific needs of an institutions’ pediatric residency program. Still, each TBL module can be implemented independently from one another—they need not be “sequential.” So, programs utilizing TBL to teach ethics could tailor their curricula to the institution’s needs, and even expand the TBL modules to include other timely or locally relevant subjects.

Future Directions

In the future, we would like to build on this initial success by creating other TBL-based ethics modules. In 2019, we are piloting a new module on pediatric brain death and hope to continue expansion with modules such as global health ethics and ambulatory/outpatient ethics. We would also like to expand bioethics TBL curricula to other institutions. This would help other residencies—pediatric or otherwise—to provide a structured evidence-based ethics curriculum that is board exam oriented, while still being relevant to clinical practice.

Pediatric ethics is inseparable from pediatric medicine. The pediatrician in training requires ethical training as much as they require lessons in pulmonary or critical care medicine. Therefore, the desire of pediatric residency programs to expand ethics education for its own sake and the prioritizing of ethics education by the ACGME, AAP, and ABP all suggest that an effective, evidence-based method for teaching ethics with high learner satisfaction is necessary and should be sustained in every residency program. Our creation of a successful, entirely TBL-based ethics curriculum we believe is a first in medical education. We also believe it is highly adaptable to different institutions and learning environments, and in the future will not only show improvements in satisfaction and engagement, but most critically for pediatrics—in ethical and professional behavior.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the IRB.

Informed Consent

N/A

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: where are we? Where should we be going? A Review. Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1143–1152. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox E, Arnold R, Brody B. Medical ethics education: past, present, and future. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):761–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehman L, Kasoff W, Koch P, Federman D. A survey of medical ethics education at US and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2004;79(7):682–689. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200407000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musick DW. Teaching medical ethics: a review of the literature from North American medical schools with an emphasis on education. Med Health Care Philos. 1999:239–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Campbell A, Chin J, Voo T. How do we know that ethics education produces ethical doctors? Med Teach. 2007;29:431–436. doi: 10.1080/01421590701504077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes AK, Borges NJ, Rodabaugh H. Measuring outcomes in a pre-clinical bioethics course. Perspect Med Educ. 2012;1:92–97. doi: 10.1007/s40037-012-0014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain N, Aronowitz P. Teaching medical humanities in an internal medicine residency program. Acad Intern Med Insight. 2008;6(1):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keune JD, Kodner IJ. The importance of an ethics curriculum in surgical education. World J Surg. 2014;38:1581–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traner CB, Tolchin DW, Tolchin B. Medical ethics education for neurology residents: where do we go from here? Semin Neurol. 2018;38:497–504. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics (2017). https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/320_pediatrics_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2019: 17-18.

- 11.American Board of Pediatrics. Content specifications map. Pediatrics in Review. 2019. https://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/abp-content-specifications-map. Accessed February 22, 2019.

- 12.Section on Bioethics, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diekema DS, Leuthner SR, Vizcarrondo FE, eds. American Academy of Pediatrics Bioethics Resident Curriculum: case-based teaching guides. Revised 2017. http://www.aap.org/sections/bioethics/default.cfm , Accessed, February 22, 2019.

- 13.Cook AF, Sobotka SA, Ross LF. Teaching and assessment of ethics and professionalism: a survey of pediatric program directors. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Garza S, Phuoc V, Throneberry S, et al. Teaching medical ethics in graduate and undergraduate medical education: a systematic review of effectiveness. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:520–525. doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deonandan R, Khan H. Ethics education for pediatric residents: a review of the literature. Can Med Educ J. 2015;6(1):e61–e67. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diekema DS, Shugerman RP. An ethics curriculum for the pediatric residency program: confronting barriers to implementation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(6):609–614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430075015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang CW, Smith PJ, Ross LF. Ethics and professionalism in the pediatric curriculum: a survey of pediatric program directors. Pediatr. 2009;124:1143–1151. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martakis K, Czabanowska K, Schröder-Bäck P. Teaching ethics to pediatric residents: a literature analysis and synthesis. Klin Pädiatr. 2016;228(5):263–269. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-109709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michaelson LK, Sweet M. The essential elements of team-based learning. New Dir Teach Learn. 2008;116:7–27. doi: 10.1002/tl.330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parmelee D, Michaelsen LK, Cook S, Hudes PD. Team-based learning: a practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e275–e287. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Touchet TK, Coon KA. A pilot use of team-based learning in psychiatry resident psychodynamic psychotherapy education. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:293–296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deardorff AS, Moore JA, Borges N, Parmelee DX. Assessing first-year medical student attitudes of the effectiveness of team-based learning. Med Sci Educ. 2010;20(2):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieder G, Parmelee DX, Stolfi A, Hudes P. Team-based learning in a medical gross anatomy and embryology course. Med Teach. 2005;18(3):56–63. doi: 10.1002/ca.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimschisel T, Herring AL, Huang J, Minor TJ. A systematic review of the published literature on team-based learning in health professions education. Med Teach. 2017;39(12):1227–1237. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1340636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess AW, McGregor DM, Mellis CM. Applying established guidelines to team-based learning programs in medical schools: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):678–688. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sisk RJ. Team-based learning: systematic research review. J Nurs Educ. 2011;50(12):665–669. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20111017-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulet Juncà G, Belli D, Bajwa NM. Team-based learning to contextualise evidence-based practice for residents. Med Educ. 2017;51(5):542–543. doi: 10.1111/medu.13297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balwan S, Fornari A, DiMarzio P, Verbsky J, Pekmezaris R, Stein J, Chaudhry S. Use of team-based learning pedagogy for internal medicine ambulatory resident teaching. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):643–648. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00790.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shellenberger S, Seale JP, Harris DL, Johnson JA, Dodrill CL, Velasquez MM. Applying team-based learning in primary care residency programs to increase patient alcohol screenings and brief interventions. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):340–346. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181972855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandler TC, Laser J, Williamson AK, et al. Team-based learning in a pathology residency training program. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142:23–28. doi: 10.1309/AJCPB8T1DZKCMWUT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poeppelman RS, Liebert CA, Vegas DB, Germann CA, Volerman A. A narrative review and novel framework for application of team-based Learning in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):510–517. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00516.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung E, Rhee J, Baik Y, OS A. The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Med Teach. 2009;31:1013–1017. doi: 10.3109/01421590802590553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormack WT, Garvan CW. Team-based learning instruction for responsible conduct of research positively impacts ethical decision-making. Account Res. 2014;21(1):34–49. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2013.822267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fink, LD. A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning. 2005. Published online: https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf . Accessed February 22, 2019.

- 35.Fink LD. Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses. 2. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonsen A, Siegler M, Winslade W. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. 7. New York: McGraw Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeno LM, et al. The relative effect of team-based learning on motivation and learning: a self-determination theory perspective. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(4):ar59. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-03-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edmunds S, Brown G. Effective small group learning: AMEE Guide No. 48. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):715–726. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.505454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]