Abstract

Pathogenic KMT2E variants underly O'Donnell-Luria-Rodan syndrome, a recently described neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by global developmental delay, variable degrees of intellectual disability, and subtle facial dysmorphism. Less common findings include autism, seizures, gastrointestinal (GI) problems, and abnormal head circumference. Occurrence of mostly truncating variants as well as the similar phenotype observed in individuals with deletions spanning KMT2E suggest haploinsufficiency of this gene as a common mechanism for the disorder, while a gain-of-function or dominant-negative effect cannot be ruled out for some missense variants. Deletions reported in the literature encompass several additional known or presumed haploinsufficient genes, thus leading to more complex phenotypes. Here, we describe a male with antenatal onset hydronephrosis, hypotonia, global developmental delay, prominent GI symptoms as well as facial dysmorphism. Chromosomal microarray revealed a 239-kb de novo microdeletion spanning KMT2E and LHFPL3. Clinical presentation of our proband, harboring one of the smallest deletions of the region confirms the core features of this disorder, suggests GI symptoms as a prominent finding in affected individuals while expanding the phenotypic spectrum to abnormalities of the urinary tract.

Keywords: KMT2E, O'Donnell-Luria-Rodan syndrome, 7q22.3 microdeletion, Developmental delay, LHFPL3

Established Facts

Heterozygous KMT2E variants cause a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by developmental delay, intellectual disability, and subtle dysmorphic features.

Autism, seizures, abnormal head circumference, and gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported in some individuals with this diagnosis.

Haploinsufficiency appears to be the mechanism underlying the most prevalent categories of pathogenic variants.

Novel Insights

Gastrointestinal dysmotility appears to be a prominent feature of the disorder, supporting routine evaluation in affected subjects.

Hydronephrosis in our proband likely broadens the phenotypic spectrum of the disorder adding abnormalities of the genitourinary tract among the possible manifestations.

Introduction

O'Donnell-Luria-Rodan syndrome (ODLURO; OMIM #618512) due to pathogenic KMT2E variants has been recently added to the list of monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders associated with regulation of H3K4 methylation [O'Donnell-Luria et al., 2019]. The syndrome is typically characterized by global developmental delay, speech delay, variable degrees of intellectual disability as well as subtle facial dysmorphism. Autism and seizures have been reported in a subset of affected individuals with the former being more common in affected males and the latter in affected females [Iossifov et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2014]. The original report highlighted occurrence of relative macrocephaly and gastrointestinal (GI) dysmotility among the suggestive albeit not obligatory features of this condition. Phenotypic similarities between 30 individuals with KMT2E truncating variants and 4 with microdeletions spanning this gene suggested haploinsufficiency as the mechanism underlying pathogenicity of these variants. Observation of more severe phenotypes in 6 additional subjects harboring missense variants as well as the occurrence of microcephaly in 2, led to the speculation that a gain-of-function or dominant-negative effect may apply for this category of variants [O'Donnell-Luria et al., 2019; Sharawat et al., 2021]. Most microdeletions reported in literature, with the exception of a 52-kb intragenic deletion, encompass several other genes possibly contributing to the neurodevelopmental outcome and/or occurrence of additional features in these patients [O'Donnell-Luria et al., 2019; Conforti et al., 2021]. Our report aims to further delineate the phenotype of this disorder by presenting the case of a 3-year-old male with a minimal 239-kb microdeletion of KMT2E and LHFPL3 as the only protein coding genes involved.

Case Presentation

The proband is the only child of a nonconsanguineous couple. Family history was notable for a paternal aunt with intellectual disability secondary to trisomy 21 but was otherwise noncontributory for neurodevelopmental or other congenital anomalies. Pregnancy was complicated by bilateral hydronephrosis of mild and moderate degree, as evidenced by a renal pelvis diameter of 7.2 mm (L kidney) and 14.2 mm (R) upon 3rd trimester measurements. The couple opted for noninvasive prenatal screening using cell-free DNA which yielded a normal result for common aneuploidies.

The boy was born at 39 + 2 weeks via cesarean section. Normal delivery was avoided due to maternal pathology of very high myopia which increases risk of maternal subretinal bleeding with subsequent acute visual loss. His weight was 3,910 g (75th centile), length 51 cm (50th–75th centile), and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) 35 cm (50th–75th centile). He experienced an episode of hypoglycemia in the first minutes after delivery. Skull radiographs and head ultrasound were performed following initial pediatric evaluation due to craniotabes and revealed a slit-like aspect of the lateral ventricles and a small choroid plexus cyst. Otoacoustic emissions were normal. Postnatal ultrasonography confirmed presence of a mild dilatation of the left renal pelvis and a moderate dilatation of the right pyelocaliceal system (measuring 57 and 149 mm, respectively) without additional findings. Dysmorphic features reportedly included upslanted palpebral fissures, a depressed nasal bridge, presence of a short neck, bilateral sandal gap, and 3rd toes overlapping the 4th and 5th. Due to the overall presentation, G-banding was performed, revealing a normal karyotype.

Constipation with onset in the first months necessitated introduction of polyethylene glycol at the age of 8 months.

At the same period, the proband was referred for neurological investigation because of hypotonia and developmental delay, as he was able to support his head at 6 and sit with support at 8 months, respectively. A brain MRI revealed widened interhemispheric fissure. Sleep EEG did not show epileptiform abnormalities. Routine blood investigations, renal and thyroid function as well as basic metabolic work-up were normal. Physical therapy was initiated.

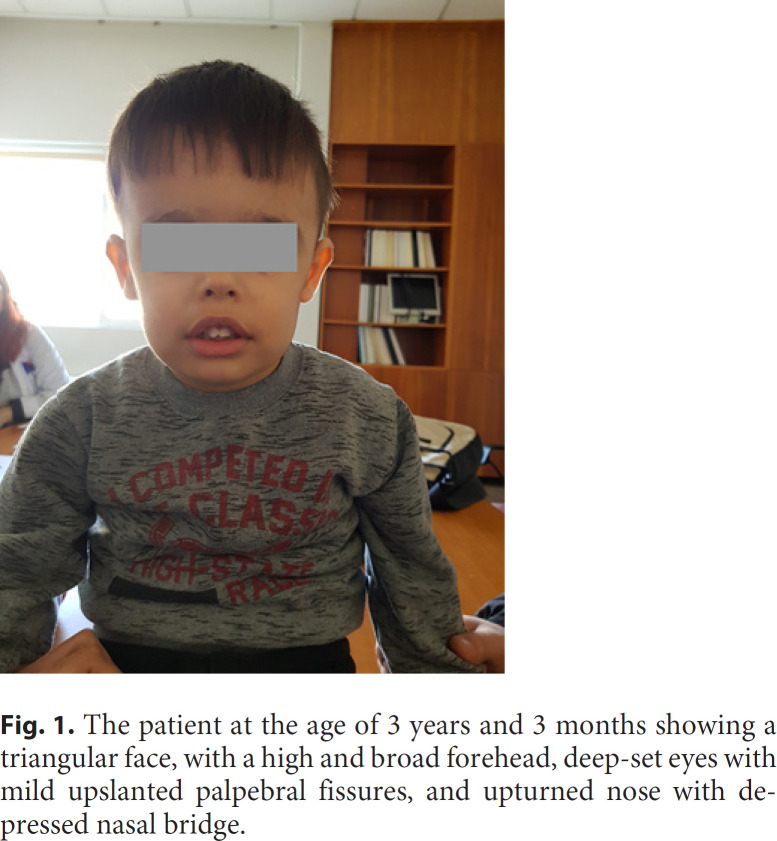

Upon examination at 11 months, he displayed a large forehead, upslanted palpebral fissures, long eyelashes, depressed nasal bridge, prominent ears, and a large mouth with tented upper and everted lower lip (Fig. 1). The chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) performed did not reveal any variants fulfilling criteria for classification as likely pathogenic/pathogenic at the time but revealed a 239-kb deletion encompassing the genomic region 7q22.2q22.3, characterized as variant of uncertain clinical significance.

Fig. 1.

The patient at the age of 3 years and 3 months showing a triangular face, with a high and broad forehead, deep-set eyes with mild upslanted palpebral fissures, and upturned nose with depressed nasal bridge.

Repeat urinary tract echography revealed on several occasions mild dilatation of the pyelocaliceal system with extrarenal pelvis bilaterally as well as enlarged kidneys. Antibiotic prophylaxis was discontinued following a normal cystourethrogram.

Due to persistence of constipation, serologic testing for celiac disease was requested but came out negative. Treatment with laxatives was sustained and later switched to lactulose following the recommendation of his gastroenterologist. Barium enema at 2.5 years revealed globally diminished peristalsis with slow transit of the contrast agent and a saw-tooth appearance at the wall of the descending colon. Medial sigmoid demonstrated a region of permanently diminished diameter and there was paradoxical motility of the distal sigmoid before the rectum. The rectosigmoid index was 1. The overall examination raised suspicion of Hirschsprung disease; however, additional investigations including rectal biopsy were deferred on parental request.

The child underwent a thorough developmental assessment at the age of 2 years and 9 months. Apart from delayed head control and independent sitting, crawling was achieved at the age of 15 months. Occupational therapy was initiated at 18 months. He was able to stand without support and walk at the age of 19 and 22 months, respectively. At 33 months, he was still described as clumsy. Due to speech and language delay, therapy was initiated at the age of 18 months. At 2 years he had a vocabulary of less than 5 to 10 words and began combining words at the age of 2.5 years. Developmental evaluation denoted expressive language delay with dysarthria, as speech remained limited and poorly intelligible upon assessment. Comprehension and cognitive levels grossly corresponded to his chronological age. Up to this age no elements in favor of an autism spectrum disorder (using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule), ADHD or other behavioral disorder were present. Ophthalmological evaluation at the same age was normal, without any evidence of strabismus. Fundoscopy was normal.

Echocardiography was scheduled due to persistence of a systolic murmur and revealed a minimal pulmonary and tricuspid valve regurgitation without clinical significance.

Upon follow-up in our genetics clinic at the age of 3 years and 3 months, the child displayed a triangular face, with high and broad forehead, deep-set eyes with mild upslanted palpebral fissures, and an upturned nose with depressed nasal bridge. The mouth was tented with eversion of the lower lip. Hand examination showed signs of excess palmar skin. There was bilateral 5th finger clinodactyly. Brief examination of the trunk did not reveal significant anomalies. The boy had dysplastic toenails, while the 4th toes were bilaterally overlapping the 3rd and 5th toes. Evaluation of the growth charts did not suggest any growth abnormality apart from an OFC consistently above other measurements (Fig. 1). Recent brain MRI was within normal limits. A new appointment was pending for further investigation of his constipation and/or rectal biopsy. On occasion of this follow-up, re-evaluation of the previous CMA result was carried out.

Materials and Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples of the proband and both parents using the QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality and quantity of DNA was determined using the NanoDrop 1000 UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

CMA was performed using the high resolution 4 × 180K G3 CGH + SNP microarray platform (G4890A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), featuring a total of 110,712 oligonucleotide CGH probes, spanning the whole genome with a median CGH probe spacing of 25.3 kb, as well as 59,647 SNP probes for the detection of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity.

The laboratory protocol was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Oligonucleotide Array-Based CGH for Genomic DNA Analysis) and in short, consisted of enzymatic digestion of each genomic DNA sample as well as a sex-matched reference DNA (Agilent Technologies), followed by differential fluorescent labeling, hybridization, and scan. The resulting tiff images were extracted and analyzed using the Agilent Feature Extraction software and the CytoGenomics v.5.0.1 software suite. The ADM-1 aberration detection algorithm was utilized, with the minimum number of probes required for a call set to 4 and the log2 ratio threshold for duplications and deletions set to ±0.25.

Data were annotated against the NCBI human genome build 37 (hg19, February 2009) and assessed by searching the literature and available databases as previously described [Oikonomakis et al., 2016]. CNV re-analysis was performed based on the recently published ACMG/ClinGen recommendations for interpretation and reporting of constitutional CNVs [Riggs et al., 2020].

Results

CMA of the patient revealed a 239-kb deletion from 7q22.2 to 7q22.3 (arr[GRCh37] 7q22.2q22.3(104477768_104716970)×1). Analysis of the parental samples revealed that the microdeletion had occurred de novo. The deletion is predicted to remove the terminal exon of LHFPL3 (NM_199000.2) as well as the first 9 exons of KMT2E (NM_182931.2) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The 239-kb microdeletion identified in our patient (top), spanning the KMT2E and LHFPL3 genes, and shown in the UCSC Genome Browser (bottom).

Taking into consideration (a) that the deletion contains only 2 protein-coding genes (KMT2E and LHFPL3, evidence 1 and 3A in the technical standards copy-number loss scoring metric [Riggs et al., 2020] − total score: 0), (b) that 2 or more haploinsufficiency predictors suggest that at least 1 gene within this interval is haploinsufficient (2E - score 0.15), (c) the several individual cases presenting with developmental delay due to assumed de novo occurrence of loss-of-function variants or CNVs spanning KMT2E (4C - total score of 0.9), and (d) that the CNV was not present in the parental samples (5A - score of 0.1), the deletion in our proband was classified as pathogenic. No other pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant was identified in the analysis.

Discussion

Our proband presented with hypotonia, developmental delay, GI dysmotility, repeated OFC measurements above the corresponding percentiles for height and weight, as well as facial dysmorphism − all features consistent with those reported in individuals with KMT2E deletions and truncating variants. Detailed assessment until this age did not reveal any behavioral anomalies, including autism spectrum disorder which was observed in some of the affected males in the original cohort. In addition, there was no clinical or EEG evidence of epilepsy until the age of 3 years.

He suffered from refractory chronic constipation which was brought to medical attention at the age of 2.5 months, necessitating early introduction of laxatives and extensive work-up. The latter allowed exclusion of celiac disease but raised clinical suspicion for Hirschsprung disease. Interestingly, O'Donnell-Luria et al. [2019] reported occurrence of GI dysmotility in a proportion of affected individuals within their cohort. In particular, constipation was reported in 1 individual with a microdeletion encompassing KMT2E, 4 with truncating KMT2E variants as well as 3 with missense variants. While some of these patients also had additional GI complaints, 8 further patients were noted to have other nonspecific GI problems including reflux or recurrent vomiting, delayed gastric emptying, colitis, diarrhea/loose stools, and abdominal distension. Overall, GI problems were reported in 16 of 29 (55%) of subjects for whom this information was available [O'Donnell-Luria et al., 2019]. We thus propose that constipation and GI symptoms are considered among the major features of KMT2E-related disorder, and that GI involvement be routinely evaluated in relevant individuals.

Our patient presented with prenatal onset of bilateral hydronephrosis which was confirmed upon repeated postnatal follow-up and associated with globally enlarged kidneys. Ultrasonography and cystourethrogram did not provide any evidence of associated obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux. There was no impairment of renal function. Urinary tract anomalies have not been previously reported in individuals with KMT2E-related disorder. Chromosomal anomalies, in particular common aneuploidies, however account for a significant proportion of antenatal hydronephrosis [Damen-Elias et al., 2005]. Review of individuals reported in the DECIPHER database (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk) did not reveal any other case with abnormalities of the urinary tract. Our deletion encompassed KMT2E and LHFPL3. The latter displays a haploinsufficiency index of 4.8% in DECIPHER and appears to be intolerant to loss-of-function variants (pLI score of 0.93 in gnomAD) [Karczewski et al., 2020]. Despite a plausible deleterious effect of LHFPL3 haploinsufficiency, data from the GTEx project [Lonsdale et al., 2013] suggest that this gene is only weakly expressed in the kidneys, with expression data for KMT2E further supporting a role of the latter in pathogenesis of the renal anomaly. One must however acknowledge that this feature may be unrelated to KMT2E haploinsufficiency and/or better explained by a variant elsewhere in the genome. Given our observation, we propose a low threshold for consideration of genitourinary investigations in relevant individuals.

Recognizing limitations of their sample size, O'Donnell-Luria et al. [2019] noted that developmental delay within the microdeletion group appeared to be more severe compared to those observed in subjects with intragenic variants. Microdeletions within this cohort however spanned several other genes, likely contributing to a more complex phenotype in the respective patients. Our knowledge of LHFPL3 is very limited, and there is currently no associated phenotype in OMIM. Rauch et al. [2012] reported on an individual belonging to a large cohort with severe nonsyndromic intellectual disability, who was found to harbor a de novo LHFPL3 missense variant. An additional patient with a de novo missense SNV, intellectual disability, microcephaly, abnormal prenatal growth, and bleeding abnormality is listed in the DECIPHER database (#368500). Taking into consideration the aforementioned metrics for LHFPL3, its brain-predominant expression based on available GTEx data, as well as the above observations, one cannot draw safe conclusions on eventual contribution of this gene to our patient's presentation. Additional reports will be needed to establish phenotypes − if any − associated with LHFPL3 haploinsufficiency.

Despite the advent of modern genetic testing modalities such as next-generation sequencing, diagnostic rate for rare pediatric disorders appears to be often unsatisfactory [Wright et al., 2018]. A recent study demonstrated the utility of existing data in making new diagnoses, mainly attributed to the rapidly growing knowledge in the field and recent discovery of causal genes for several disorders [Wright et al., 2018]. Our case illustrates the need to periodically re-evaluate inconclusive genetic test results, especially before considering further investigations.

Presentation of our proband, harboring a minimal deletion affecting KMT2E, was consistent with what has recently been reported for this disorder. Our report contributes substantially to the characterization of the GI problems which appear to be frequent in affected individuals and highlights genitourinary anomalies as possible manifestations of this condition, further delineating the phenotypic spectrum of this newly described genetic syndrome.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Bioethics Committee of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents for publication of this report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for the study.

Author Contributions

K. Kosma performed the detailed clinical evaluation of the patient. K. Varvagiannis prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, participated in clinical evaluation of the case and reanalysis of the CMA result. A. Mitrakos performed CMA testing, analysis of CMA results, and prepared the final draft of the manuscript. M. Tsipi contributed to CMA testing and preparation of the manuscript. J. Traeger-Synodinos supervised the study. M. Tzetis performed analysis of the results and supervised the study.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank the patient and his family for participating in this study.

References

- 1.Conforti R, Iovine S, Santangelo G, Capasso R, Cirillo M, Fratta M, et al. ODLURO syndrome: personal experience and review of the literature. Radiol Med. 2021;126((2)):316–22. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damen-Elias HA, De Jong TP, Stigter RH, Visser GH, Stoutenbeek PH. Congenital renal tract anomalies: outcome and follow-up of 402 cases detected antenatally between 1986 and 2001. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:134–43. doi: 10.1002/uog.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong S, Walker MF, Carriero NJ, DiCola M, Willsey AJ, Ye AY, et al. De Novo Insertions and Deletions of Predominantly Paternal Origin Are Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cell Rep. 2014;9:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iossifov I, Ronemus M, Levy D, Wang Z, Hakker I, Rosenbaum J, et al. De Novo Gene Disruptions in Children on the Autistic Spectrum. Neuron. 2012;74:285–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–43. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, Phillips R, Lo E, Shad S, et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell-Luria AH, Pais LS, Faundes V, Wood JC, Sveden A, Luria V, et al. Heterozygous Variants in KMT2E Cause a Spectrum of Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:1210–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oikonomakis V, Kosma K, Mitrakos A, Sofocleous C, Pervanidou P, Syrmou A, et al. Recurrent copy number variations as risk factors for autism spectrum disorders: Analysis of the clinical implications. Clin Genet. 2016;89:708–18. doi: 10.1111/cge.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch A, Wieczorek D, Graf E, Wieland T, Endele S, Schwarzmayr T, et al. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non-syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet. 2012;380:1674–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, Kantarci S, Kearney H, Patel A, et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Genet Med. 2020;22:245–57. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharawat IK, Panda PK, Dawman L. Clinical Characteristics and Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in Children with KMT2E Gene-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Report of Two New Cases and Review of Published Literature. Neuropediatrics. 2021;52:98–104. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright CF, FitzPatrick DR, Firth HV. Paediatric genomics: diagnosing rare disease in children. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:253–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]