SUMMARY

Glucose and fructose are closely related simple sugars, but fructose has been associated more closely with metabolic disease. Until the 1960s, the major dietary source of fructose was fruit, but subsequently, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) became a dominant component of the Western diet. The exponential increase in HFCS consumption correlates with the increased incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, but the mechanistic link between these metabolic diseases and fructose remains tenuous. Although dietary fructose was thought to be metabolized exclusively in the liver, evidence has emerged that it is also metabolized in the small intestine and leads to intestinal epithelial barrier deterioration. Along with the clinical manifestations of hereditary fructose intolerance, these findings suggest that, along with the direct effect of fructose on liver metabolism, the gut-liver axis plays a key role in fructose metabolism and pathology. Here, we summarize recent studies on fructose biology and pathology and discuss new opportunities for prevention and treatment of diseases associated with high-fructose consumption.

INTRODUCTION

Glucose is the major circulating carbohydrate in animals, whereas sucrose, a disaccharide consisting of glucose and fructose, is the major circulating carbohydrate in plants. However, certain fruits, such as figs, dates, mangoes, and pears, contain high amounts of free fructose. As humans have always consumed plants and fruits, fructose is a basic component of our diet and, for a long time, was considered neutral or even beneficial (Rippe and Angelopoulos, 2015). Nevertheless, the overconsumption of refined sugars, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in particular, is increasingly considered as a major contributor to the growing incidence of a myriad of so-called lifestyle diseases. These include type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its aggressive form, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH); certain cancers, especially those of the liver, pancreas, and colon; and cardiovascular and kidney diseases. Although HFCS has been banned in several countries, it still accounts for approximately 40% of caloric sweeteners in the USA (White, 2008). Instead of being an equimolar mix of fructose and glucose as in sucrose, semi-artificial HFCS contains 25%–50% more fructose than glucose (Tappy and Lê, 2010). Much of the large increase in the sugar content of the Western diet is due to sweetened beverages—not only sodas but also fruit juices and sport drinks. On average, such drinks contribute to ~5% of daily caloric intake and 2 in 3 high-school-aged children in the USA consume at least one of these beverages per day (Kit et al., 2013).

FRUCTOSE CONSUMPTION AND HEALTH: CLUES FROM HISTORY

It is widely believed that cane sugar (sucrose) was first used by humans in Polynesia, from where it spread to India. In the early centuries AD, Indians perfected the refining of cane sugar to crystal granules (Deerr, 1949). Cane sugar manufacturing had spread to the medieval Islamic world, where it was very expensive and was referred to as a “fine spice” and used for medicinal purposes. After the discovery of America, sugar cane culturing was introduced to the Caribbean, which supplied sugar to Europe (Deerr, 1949) and the United Kingdom, where sugar consumption increased by 1,500% in the 18th and 19th centuries. Despite this substantial growth, sugar consumption was not linked to increased metabolic disease risk until the 20th century. In the late 19th century, obesity, referred to as corpulence, affected less than 4% of the population (Osler, 1893) and T2DM affected 2 people per 100,000 (Johnson et al., 2017). As reviewed by Johnson and coworkers (Johnson et al., 2017), it was not until the early 20th century that a British physician stationed in India by the name of Sir Richard Havelock Charles made the observation that T2DM was increasing at a rapid rate among sugar-consuming, wealthy Indians living in Calcutta, but it was almost non-existent in poorer areas of India, where sugar consumption was nil. Sir Fredrick Banting, the Nobel laureate for medicine and physiology for his discovery of insulin, also hypothesized that refined sugar consumption could be linked to T2DM (Banting, 1926), but this was challenged by other notable scientists of the time, including Elliot Joslin, who believed that overeating and lack of physical activity led to metabolic diseases (Joslin and Lahey, 1934). Whether sugar consumption is a cause of modern-day obesity and T2DM still remains controversial (Khan and Sievenpiper, 2016).

It is important to note that, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the estimated per capita consumption of refined sugar has actually decreased in the past 50 years, but HFCS consumption has increased, such that by the mid-1990s it exceeded refined sugar consumption (Tappy and Lê, 2010). As the cost of sugar refinement grew in the mid-20th century, the industry was looking for cheaper alternatives, and in the late 1950s, scientists in the USA and Japan developed HFCS as a cheaper and sweeter sucrose substitute (Hanover and White, 1993). HFCS was also found to have a longer shelf life compared with cane sugar, leading to its increasing popularity as a sweetener and food additive in the latter part of the 20th century (White, 2008).

GLUCOSE VERSUS FRUCTOSE: GASTROINTESTINAL (GI) METABOLISM

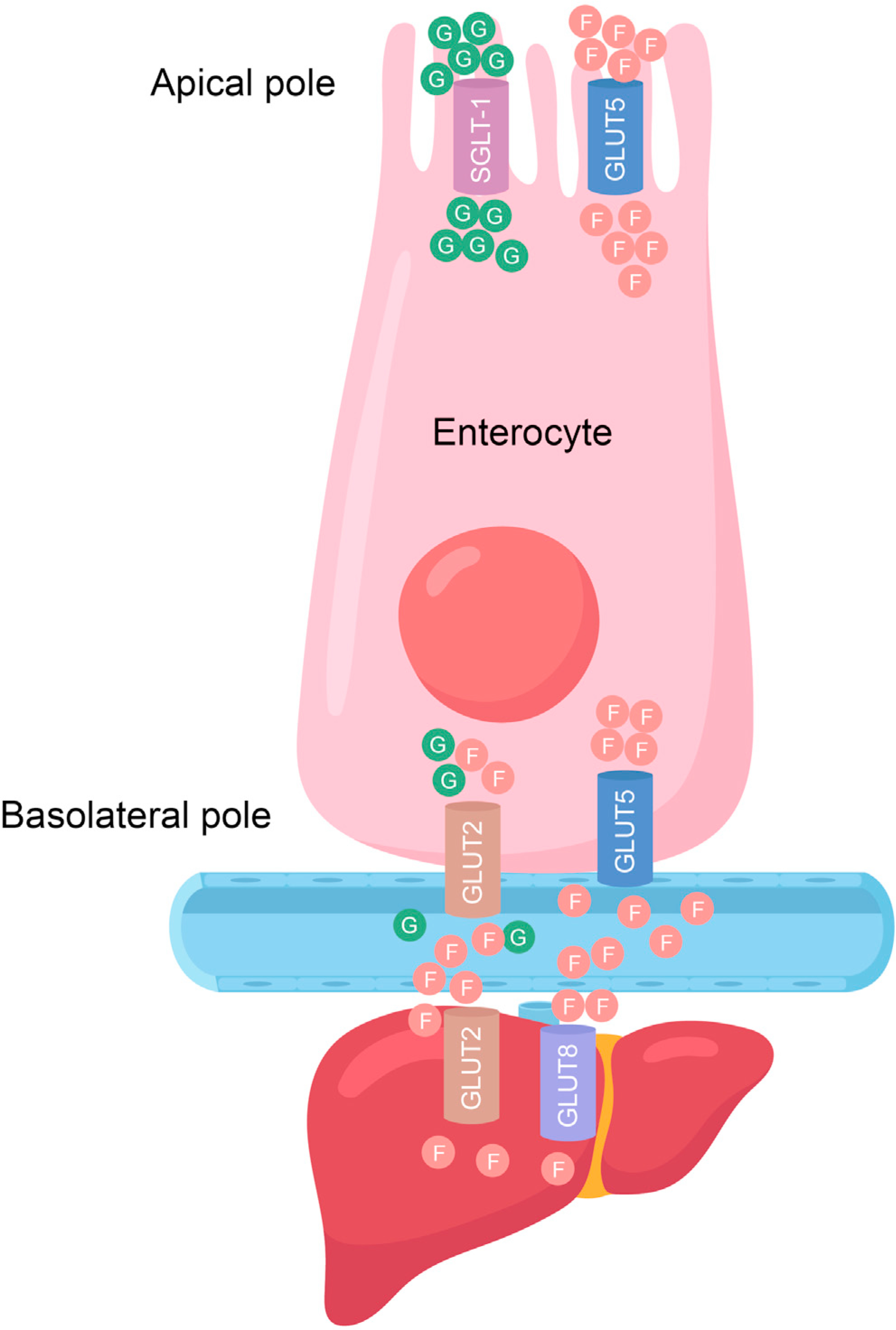

For many years, fructose and glucose were claimed to be indistinguishable in their health effects, but most recent studies suggest that fructose is the more deleterious of the two monosaccharides. The early dogma that fructose and glucose are equivalent is understandable, given that they are both hexoses with the same chemical formula C6H12O6. However, critically, fructose possesses a keto group in position 2 of its carbon chain, whereas glucose possesses an aldehyde group at position 1. Unlike glucose, which is mobilized by phosphofructokinase and glucokinase, the latter being an enzyme whose activity is subject to feedback inhibition and regulation by insulin, fructose is mobilized by the faster and constitutively active enzyme fructokinase (also known as ketohexokinase or KHK) (Geidl-Flueck and Gerber, 2017) (Figure 1). As KHK is not feedback inhibited, its action results in rapid and robust conversion of fructose to fructose-1 phosphate (F1P), a potentially toxic intermediate that will be discussed further on. Although dietary fructose was initially thought to be metabolized exclusively in the liver, to which it is delivered by the portal circulation (Lyssiotis and Cantley, 2013; Vos and Lavine, 2013), it is now clear that dietary fructose is also metabolized at its site of absorption, the small intestine (Jang et al., 2018; Mayes, 1993), particularly when it is consumed at physiological concentrations. Whether fructose presents as pure fructose, sucrose, or HFCS, it is transported intracellularly via GLUT5 (also known as SLC2A5), a transporter expressed at the apical pole of the enterocyte luminal membrane with a high affinity (Km = 6.0 mM) for fructose (Douard and Ferraris, 2008; Patel et al., 2015) (Figure 2). In mice, the deletion of GLUT5 markedly reduces fructose absorption and leads to colonic dilation and flatulence (Barone et al., 2009), results that are likely to be of direct human relevance. Fructose absorption can be limited in some humans that have a low absorption capacity and develop flatulence and diarrhea if they consume moderate to high amounts of fructose (Ravich et al., 1983), particularly if the fructose is free and not ingested as sucrose (Truswell et al., 1988). The molecular mechanisms that account for aberrant fructose metabolism are not fully understood, but they may be related to aging (Ferraris et al., 1993) and co-ingestion of other macronutrients, such as lipids (Perin et al., 1997). In addition, both the intestinal thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) (Dotimas et al., 2016) and the carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) (Iizuka et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2017b) are implicated in the regulation of GLUT5 and subsequent systemic fructose tolerance. Whether any of these proteins can be targeted to enhance fructose absorption, to the best of our knowledge, has not been investigated. These key findings, along with the clinical manifestations of hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) discussed further on, suggest that the GI tract plays a key role in fructose metabolism and pathology.

Figure 1. Fructose metabolism.

After ingestion, fructose is metabolized either in the gastrointestinal tract or the liver. Fructose is initially mobilized by the constitutively active enzyme ketohexokinase (KHK), which converts it to fructose 1 phosphate (F1P) that is subsequently cleaved by the rate limiting enzyme aldolase B to glyceraldehyde (GA) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP). GA undergoes a series of subsequent metabolic conversions to form pyruvate, from which it can be converted to lactate, undergoes oxidative metabolism via the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, or feed de novo lipogenesis after the generation of acetyl and malonyl coenzyme A (CoA), finally generating triacylglyceride (TAG). The formation of malonyl CoA can alter the balance between fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and synthesis through an effect on acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), resulting in the inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which stimulates FAO and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), which control the entry of fatty acids into the mitochondrion. ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), which uses cytosolic citrate to generate acetyl-CoA, is also upregulated by fructose consumption. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) converts DHAP to glycerol-3 phosphate (G3P), which, together with fatty acids, generates TAG.

Figure 2. Fructose absorption at different sites.

Fructose and glucose are absorbed at the apical pole of the enterocyte by glucose transporter (GLUT) 5 and sodium-glucose co-transporter 1 (SGLT-1), respectively. The entry of fructose from the basolateral pole of the enterocyte is facilitated by GLUT5 and possibly GLUT2. Fructose uptake by the liver is primarily due to the action of GLUT2, but GLUT8 may also play a role in this process.

FRUCTOSE METABOLISM: LESSONS LEARNED FROM HEREDITARY FRUCTOSE INTOLERANCE

HFI is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a mutation in the gene-encoding aldolase B, the enzyme that converts F1P into glyceraldehyde (GA) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP). GA is subsequently metabolized to pyruvate, which feeds the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle via pyruvate dehydrogenase or is converted by lactate dehydrogenase to lactate. Through DHAP, fructose serves as a precursor for triglyceride synthesis via the intermediary metabolite glycerol-3-phosphate, which is conjugated to fatty acids generated by de novo lipogenesis (DNL) from citrate, exiting the TCA cycle (Figure 1), although bacterial acetate has also emerged as a lipogenic substrate (Zhao et al., 2020), which will be further discussed later on. In patients with HFI, F1P accumulates, leading to phosphate trapping and ATP depletion (Kim et al., 2021). The reduction in ATP and inorganic phosphate leads to uric acid accumulation in enterocytes, hepatocytes, and renal tubular cells, as well as lactic acidosis and hypokalemia, resulting in liver and kidney cell toxicity (Kim et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 1979). These metabolic disturbances are thought to be responsible for hepatic and renal dysfunction in patients with HFI (Richardson et al., 1979). Fructose intolerance has largely been viewed as a liver disease, rather than as a GI disease, and this may be due to the histopathology and ultrastructural presentation of liver biopsies from patients with HFI, which show giant cell transformation, steatosis, fibrosis, and even cirrhosis (Phillips et al., 1968). HFI livers also present with abnormal membrane-bound bodies in the areas of glycogen deposition, which have been termed as “fructose holes” (Phillips et al., 1970). In addition, patients with HFI present with NAFLD, which is not related to obesity and insulin resistance (Aldámiz-Echevarría et al., 2020). In fact, unlike most patients who present with NAFLD and with insulin resistance and/or hyperglycemia, HFI is an unusual cause of hypoglycemia (Morales-Alvarez et al., 2019), suggesting that, in addition to DNL, HFI-induced NAFLD may be caused by impaired mitochondrial function (Lanaspa et al., 2012). As with many genetic disorders, much can be learned by studying pre-clinical models that phenocopy human disease, as is the case with aldolase-B-deficient mice (Oppelt et al., 2015). Genetic ablation and pharmacological inhibition of the KHK-C isoform in aldolase-B-deficient mice prevented hypoglycemia and the liver and GI injuries associated with HFI (Lanaspa et al., 2018).

HFI diagnosis is usually made at an early age (~6 months) when infants are weaned off breast milk. Early symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain (Kim et al., 2021), the severity of which depends on the specific mutation in ALD-B, which resides on chromosome 9q22. The most common mutations are A150P, A149P, and A174D (Esposito et al., 2004; Lau and Tolan, 1999). HFI is treated mainly by dietary adherence and patients have an excellent prognosis if they follow strict dietary advice (Ahmad and Sharma, 2021), although the work discussed earlier (Lanaspa et al., 2018) suggests that KHK inhibitors may provide an alternative therapeutic option. In toto, although aldolase B is expressed in the liver, kidney, and GI tract, and patients with HFI eventually develop severe liver abnormalities, the initial defect may be due to intestinal aldolase B deficiency, as patients first present with recurrent vomiting, abdominal bloating, and diarrhea (Ahmad and Sharma, 2021).

HEPATIC FRUCTOSE METABOLISM AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Fructose is taken up via GLUT5 at the enterocyte apical pole, whereas glucose is absorbed via the sodium-glucose-linked transporter-1 (SGLT-1) (Ferraris et al., 2018) (Figure 2). How the two sugars are released into the portal circulation is controversial. Although some have proposed that GLUT2 facilitates release of both glucose and fructose at the enterocyte basolateral pole (Ferraris et al., 2018; Kellett and Helliwell, 2000), others have observed that GLUT2 has a lower affinity for fructose compared with GLUT5 (GLUT2: Km = 11.0 mM) (Manolescu et al., 2007). This suggests that GLUT2 is a minor contributor to fructose export from the GI tract, with the major basolateral transporter being GLUT5 (Hannou et al., 2018; Manolescu et al., 2007) (Figure 2). However, it is well accepted that fructose uptake into the liver is primarily mediated by GLUT2 (Cheeseman, 1993; Colville et al., 1993; Karim et al., 2012) because GLUT5 is not well expressed in this tissue (Karim et al., 2012). GLUT8 may also play a role in fructose uptake by the liver (Debosch et al., 2014) (Figure 2). Once fructose enters the cell, it is rapidly metabolized by KHK to F1P (Figure 1). Along with its high affinity for fructose, KHK also has a high Vmax (~3 μmol/min/g wet weight in rat liver) (Adelman et al., 1967). As such, the metabolism of fructose, once inside the hepatocyte, is rapid, following the same path as within the enterocyte, eventually giving rise to citrate, as a result of oxidative stress-induced inhibition of aconitase (Lambertz et al., 2017), the enzyme that catalyzes the stereo-specific isomerization of citrate to isocitrate via cis-aconitate. Citrate is converted by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) to acetyl-CoA, which is converted by ACC1 to malonyl CoA, the precursor for fatty acid synthesis by fatty acid synthase (FASN). Upon conjugation with G3P, the C:16 and C:18 fatty acids made by FASN are converted to TAG (Figure 1), which forms lipid droplets. Excessive lipid droplet buildup within hepatocytes gives rise to NAFLD, which in response to additional hits progresses to NASH (Lyssiotis and Cantley, 2013; Vos and Lavine, 2013). The role of DNL in the generation of liver fat from fructose is unequivocal, since administration of 14C-fructose in rodents (Bar-On and Stein, 1968) or 13C-acetate together with fructose in humans (Parks et al., 2008) results in tracer incorporation into liver lipids. However, the role of ACLY in the fructose-driven NAFLD was recently questioned (Zhao et al., 2020), but as discussed further on, these results may not apply to NAFLD driven by long-term fructose consumption. However, it is also important to note that compared with glucose, fructose ingestion has a minor effect on plasma glucose and insulin, an important stimulator of fat storage. Moreover, a large fraction of ingested fructose is oxidized, with ~25% being converted to lactate and approximately 15%, giving rise to glycogen. Thus, compared with glucose, less ingested fructose is converted to triglycerides (Petersen et al., 2001; Tappy and Lê, 2010; Tappy et al., 1986).

As obesity rates have grown in parallel with HFCS consumption, many researchers assume that HFCS and fructose consumption contribute to obesity (Bray et al., 2004). However, recent research suggests that this may not be the case. Although rodent studies suggest that fructose feeding induces leptin resistance, which leads to weight gain (Shapiro et al., 2008), in well-controlled human studies, a fructose-rich diet did not increase weight compared with a diet matched for energy from glucose (Stanhope et al., 2009). Further human studies have demonstrated that gut-derived appetite-controlling hormones, such as leptin and ghrelin, are not elevated by HFCS consumption (Melanson et al., 2007; Soenen and Westerterp-Plantenga, 2007). This has led both the American Medical Association and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics to conclude that HFCS is not a direct cause of obesity (Klurfeld et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the weight of evidence suggests that long-term and excessive fructose consumption results in dyslipidemia and hepatosteatosis (Tappy and Lê, 2010). As discussed earlier, it is extremely difficult to determine the effects of increased fructose intake per se on disease pathology because fructose is usually consumed in the diet as sucrose or HFCS, not as free fructose and studies often do not match for caloric content (Tappy and Lê, 2010), raising the possibility that disease pathology is simply a function of caloric excess. This point has been addressed in a carefully controlled human study where overweight and obese subjects consumed glucose- or fructose-sweetened beverages providing 25% of their energy requirements for 10 weeks (Stanhope et al., 2009). Importantly, hepatic DNL and postprandial triglyceride content were only increased in the group subjected to fructose (Stanhope et al., 2009). Several studies have demonstrated that a much larger fraction of ingested fructose fluxes into DNL relative to glucose (Crescenzo et al., 2013; Kazumi et al., 1986; Parks et al., 2008; Zavaroni et al., 1982). These pre-clinical studies have recently been verified in a randomized-controlled study in humans (Geidl-Flueck et al., 2021). The pathways by which fructose supports hepatosteatosis, DNL, and the generation of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) triglycerides were comprehensively discussed in previous reviews (Hannou et al., 2018; Tappy and Lê, 2010). Importantly, fructose enhances the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1c), the major transcriptional regulator of the enzymes that mediate hepatic DNL (Matsuzaka et al., 2004; Shimomura et al., 1999; Softic et al., 2017). These results explain how fructose is associated with a poorer metabolic outcome compared with glucose ingestion (Softic et al., 2017). Fructose also affects the balance between fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and synthesis (DNL) by inhibiting the expression of critical FAO-related enzymes (Lally et al., 2019; Pinkosky et al., 2020), including carnitine palmitoyltransferase1 (CPT1), which controls the entry of fatty acids into the mitochondria (Bruce et al., 2009; Goedeke et al., 2018) (Figure 1). Of note, CPT1 activators and ACC1 inhibitors are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of metabolic diseases (Goedeke et al., 2018; Schreurs et al., 2010; Softic et al., 2017), whereas bempedoic acid (Nexletol), an ACLY inhibitor, is a clinically approved drug to treat hypercholesterolemia, as it lowers LDL cholesterol and attenuates atherosclerosis (Pinkosky et al., 2016). Work from our groups (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Todoric et al., 2020) and others (Kammoun et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2008) has demonstrated that fructose can induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which, in turn, can drive hepatosteatosis (Nakagawa et al., 2014). The underlying pathway seems to involve caspase-2, whose expression is inflammation (TNF) and ER stress inducible and leads to SCAP-independent activation of SREBP1/2 through non-canonical proteolytic activation of site 1 protease (S1P) (Kim et al., 2018). Interestingly, adipose tissue lipolysis has been suggested to contribute to NASH pathology (Thörne et al., 2010). However, paradoxically, acute fructose ingestion is antilipolytic (Abdel-Sayed et al., 2008; Tappy et al., 1986), suggesting that fructose does not promote adipose tissue lipolysis, which is consistent with the general observation that fructose consumption per se does not result in increased adiposity.

RECENT ADVANCES IN FRUCTOSE-INDUCED HEPATOSTEATOSIS

Until recently, fructose was thought to stimulate hepatosteatosis through liver-specific mechanisms. However, some years ago, Johnson and colleagues proposed that KHK in the GI tract could promote steatohepatitis in horses (Johnson et al., 2013) and humans (Jensen et al., 2018). This hypothesis was tested in mice by specifically ablating KHK in the intestine and/or liver (Andres-Hernando et al., 2020). Interestingly, intestinal-specific KHK deletion affected sugar intake and preference, causing an aversion type of response to fructose. These recent results are consistent with previous observations in whole-body A and C isoform KHK-deficient mice who, unlike their wild-type counterparts, did not show preference for fructose-sweetened water over water alone (Ishimoto et al., 2012). However, critically, intestinal-specific KHK deletion did not prevent hepatosteatosis (Andres-Hernando et al., 2020). In contrast, hepatocyte-specific KHK ablation prevented both hepatosteatosis and metabolic disease (Andres-Hernando et al., 2020). Recent work from several laboratories, including ours, also suggests that fructose affects hepatosteatosis through the “gut-liver axis,” a physiological circuit through which gut microbiota and/or their products reach the liver via the portal circulation to provoke an inflammatory response that alters liver metabolism. Although it may seem that fructose-induced liver pathology through a link between the gut and the liver is a relatively new concept, this physiological link has been known for some time. In 1969, Blendis and colleagues (Blendis et al., 1969) first described the coeliac axis and its impact on liver disease. This was not entirely surprising, since the gut and the liver are connected via the portal circulation that drains digested food and components of disintegrated bacteria into the liver. The concept that the gut affects liver disease is supported by observations that are as follows: (1) the liver is the primary site for colon cancer metastasis, (2) steatohepatitis frequently develops in patients with jejunoileal bypass and short bowel syndrome, and (3) many viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic diseases affect the intestine, as well as the liver and the biliary tract (Zeuzem, 2000). In a key paper published in 2006, Gordon and colleagues identified the gut microbiome as a pivotal player in the etiology of obesity-related metabolic disease (Turnbaugh et al., 2006). With this observation, the gut microbiome became a part of the gut-liver axis and a target for treatment of numerous metabolic diseases affecting the liver, discussed in detail subsequently. Moreover, hepatosteatosis and NAFLD are common co-morbidities of inflammatory bowel disease (Chao et al., 2016).

In a recent study conducted by Wellen, Rabinowitz, and coworkers (Zhao et al., 2020), ACLY was specifically ablated in mouse hepatocytes. Using in vivo isotopic tracing, the authors found that this genetic manipulation did not prevent fructose-induced hepatosteatosis, although it should be noted that, in this study, the high-fructose diet did not markedly increase hepatic triglyceride content even in wild-type control mice (Zhao et al., 2020). The same authors previously observed that fructose is converted to acetate by the microbiota (Jang et al., 2018) and that acetate can generate acetyl-CoA independent of ACLY (Zhao et al., 2016). Accordingly, they tested the hypothesis that fructose-induced lipogenesis in the liver is driven by microbiota-derived acetate. They observed that the depletion of microbiota markedly suppressed the conversion of fructose into acetyl-CoA in the liver and hepatosteatosis (Zhao et al., 2020), suggesting that fructose metabolism in the GI tract may control hepatosteatosis (Figure 3). However, as discussed below, any experiment based on bulk depletion of the microbiota needs to be carefully interpreted because of the major role of Gram-negative gut bacteria in the generation of endotoxin (LPS), which seems to be a key player in fructose-induced hepatosteatosis (Todoric et al., 2020). Moreover, all bacteria release bacterial nucleic acids that further enhance hepatic inflammation. In a recent study (Jang et al., 2020), the Rabinowitz group performed intestinal-specific KHK-C (the more active KHK isozyme) loss- and gain-of-function experiments. They demonstrated that, on the one hand, KHK-C deletion increased fructose delivery to the liver and that the microbiota promoted hepatosteatosis (Jang et al., 2020). On the other hand, KHK-C overexpression decreased fructose-induced lipogenesis (Jang et al., 2020). The authors concluded that metabolism of fructose in the gut shields the liver from fructose-induced fatty liver (Figure 3). Arriving at the same general conclusion, but via a different mechanism, our team found that fructose-induced hepatosteatosis is controlled by the intestinal epithelial barrier via the gut-liver axis (Todoric et al., 2020). Consistent with previous reports in animals (Cho et al., 2021; Kavanagh et al., 2013; Spruss et al., 2012) and humans (Jin et al., 2014), we found that excessive fructose consumption resulted in barrier deterioration, dysbiosis, low-grade intestinal inflammation, and endotoxemia (Todoric et al., 2020). Although we attributed barrier deterioration to KHK-dependent conversion of fructose to F1P in enterocytes, the protective effect of intestinal KHK-C ablation suggests that fructose-induced microbial dysbiosis may be the primary driver of barrier deterioration. Indeed, microbial depletion with antibiotics leads to a partial reversal of fructose-induced barrier deterioration (Todoric et al., 2020). Using RNA sequencing, we confirmed the presence of an endotoxin-induced transcriptional signature defined by the marked upregulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) 2,3,4,6,7, and 8, and their adaptor protein MyD88, and the induction of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, such as CCL2, CCL5, and TNF, in the livers of fructose-fed mice (Todoric et al., 2020). Similarly, Spruss and coworkers found that TLR4-deficient mice were protected from fructose-induced NAFLD (Spruss et al., 2009). Using several different approaches, including intestinal-specific expression of the antimicrobial protein Reg3b and myeloid-specific MyD88 ablation, we provided further support for the role of endotoxin and other microbial-generated inflammatory signals in the enhancement of fructose-induced DNL and hepatosteatosis (Todoric et al., 2020). This occurs through a multicomponent pathway consisting of recruited hepatic macrophages that produce TNF (Figure 3), which, by engaging its type 1 receptor (TNFR1) on hepatocytes, leads to the induction of the critical lipogenic enzymes ACLY, ACC1, and FASN, which convert fructose-derived acetyl-CoA to C16 and C18 fatty acids (Todoric et al., 2020). Consistent with our previous demonstration that TNFR1 signaling blockade prevents NASH (Febbraio et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2018), we found that incubation of human hepatocytes with TNF also results in the induction of lipogenic enzyme mRNAs and the conversion of either fructose or glucose to lipid droplets (Todoric et al., 2020). Critically, fructose, but not cornstarch (glucose), isocaloric feeding led to the downregulation of enterocyte tight-junction proteins and subsequent barrier deterioration, which is in agreement with previous rodents and human studies (Jin et al., 2014; Kavanagh et al., 2013; Lambertz et al., 2017; Spruss et al., 2012). In the past (Taniguchi et al., 2015), we found that enterocyte IL-6 signaling stimulates epithelial cell proliferation through the activation of Yes-associated protein (YAP), thereby conferring resistance to mucosal erosion. To test whether YAP activation can prevent fructose-induced inflammation, hepatosteatosis, and NASH, we expressed an activated form of IL-6 signal transducer (IL6ST), also known as gp130, exclusively in enterocytes, or injected fructose-fed mice with the YAP-induced matricellular protein cellular communication network factor 1 (CCN1). Both manipulations prevented the downregulation of tight-junction proteins, endotoxemia, and ameliorated fructose-induced hepatosteatosis, and NASH (Todoric et al., 2020). Although most of the studies mentioned earlier confirm the importance of the enterocyte in regulation of liver fructose metabolism, due to different experimental conditions, they arrive at seemingly different conclusions. Rabinowitz and colleagues (Jang et al., 2020), using comparatively low amounts of fructose, found that enterocyte-specific KHK-C deficiency was not protective, but hepatic steatosis was quite low in these experiments, as also observed previously (Zhao et al., 2020). Using higher amounts of fructose that cause barrier deterioration, we suggested that accumulation of toxic F1P within enterocytes may initiate the inflammatory cascade underlying hepatic steatosis and predicted that KHK inhibition should be protective (Todoric et al., 2020), which has been subsequently demonstrated (Gutierrez et al., 2021). However, as discussed earlier, the protective effect of KHK inhibition is mainly manifested in the liver and instead of F1P-induced toxicity, barrier deterioration is probably due to dysbiosis. Notably, fructose-induced inflammation is only observed after prolonged exposure, and its magnitude may depend on the animal facility, a variable that profoundly affects the microbiota (Ussar et al., 2015). Indeed, given the critical pathogenic role of barrier deterioration and endotoxemia, there is little doubt that the microbiota is a key contributor to fructose-induced liver disease (Jadhav and Cohen, 2020).

Figure 3. Schematic summary of proposed mechanisms for fructose-induced hepatosteatosis via the gut-liver axis.

Excess fructose consumption can lead to altered microbiota and the production of short chain fatty acids that ultimately stimulate hepatosteatosis. Fructose can also disrupt gut barrier integrity, resulting in systemic endotoxemia, leading to the activation of an inflammatory cascade via macrophage toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling, thus resulting in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced hepatosteatosis.

THERAPEUTIC TARGETS FOR FRUCTOSE-INDUCED STEATOHEPATITIS

NASH is one of the fastest growing metabolic diseases and has become the leading cause of liver transplantation in the USA. Not surprisingly, the NASH drug market is estimated to reach $40 billion (USD) by 2025 (Febbraio et al., 2019). Currently, there are over 30 clinical trials of new NASH drug candidates, as previously discussed by us (Febbraio et al., 2019; Smeuninx et al., 2020) and others (Lazaridis and Tsochatzis, 2017). Most therapeutic approaches to NAFLD and NASH have focused on pathways that affect the balance between fatty acid uptake and export, DNL, and FAO, as well as liver fibrosis. However, disappointingly, this therapeutic strategy has been associated with untoward side effects. Two of the most advanced drug candidates are the farnesoid X nuclear receptor (FXR) ligand obeticholic acid (Ocaliva; Intercept Pharmaceuticals) and the dual peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)α/δ agonist GFT505 (Elafibranor: Genfit), which have both reached phase III clinical trials. Another NASH drug candidate is MK-4074, a liver-specific ACC1/2 inhibitor. Although a 1-month treatment course was effective in reducing lipogenesis and liver TAG by >30%, MK-4074 unexpectedly increased plasma triglycerides by 200% (Kim et al., 2017a). Likewise, Ocaliva was rejected by the FDA in July 2020, owing to elevated LDL cholesterol in a significant number of patients. Given the common issue of hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia, new therapeutic strategies are warranted. Recently, Gilead released the results from the 392-patient ATLAS study, which tested Firsocostat, an ACC inhibitor, and Cilofexor, another FXR agonist, alone and in combination. In patients with bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis, 48 weeks of Cilofexor/Firsocostat was well tolerated and led to improvements in NASH activity but did not meet the antifibrotic target to conclude that the trial was successful (Loomba et al., 2021). Pfizer has also developed PF-05221304, an orally bioavailable, liver-directed ACC1/2 inhibitor. Recently, it was found to improve multiple NASH markers, including steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in both human primary hepatocytes and rats in vivo (Ross et al., 2020). It is currently undergoing human clinical trials (Bergman et al., 2020). As discussed earlier, the genetic deletion of KHK-C in hepatocytes (Andres-Hernando et al., 2020) can prevent hepatosteatosis and metabolic disease in mice, raising the possibility that KHK inhibition may be a viable therapeutic strategy. Recently, Pfizer has developed the KHK inhibitor PF-06835919, which is showing promise as a drug to treat NASH. In a recent study, this drug was tested in both primary hepatocytes and fructose-fed rats. PF-06835919 prevented hyperinsulinemia and hypertriglyceridemia, and reduced DNL (Gutierrez et al., 2021). Encouragingly, the authors reported the inhibitor to be safe and well tolerated in healthy humans, albeit after a single dose (Gutierrez et al., 2021). The drug is currently in a phase 2A trial in patients with NAFLD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03256526). However, of concern are the mouse studies showing that intestinal KHK deletion increased fructose delivery to the liver via spillover from the portal circulation (Andres-Hernando et al., 2020; Jang et al., 2020). Therefore, pan KHK inhibitors may present unwanted side effects, particularly when fructose ingestion is an important driver of NASH development.

Given the conflicting outcomes of KHK deletion in the gut versus the liver, we posit that new treatments for fructose-driven NASH should focus on preventing inflammation, ER stress, and gut barrier deterioration. We (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Todoric et al., 2020) and others (Kammoun et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2008) have demonstrated that fructose can lead to enterocyte ER stress, giving rise to barrier deterioration. Accordingly, the administration of ER-stress-inhibiting chemical chaperones, such as tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), a bile acid that is found in trace amounts in humans, but is quite abundant in black bears, was effective in preventing NAFLD-NASH in mice (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Todoric et al., 2020). TUDCA is sold as a nutritional supplement, but so far, it has only been used to treat primary biliary cholangitis, where it was found to be safe and effective (Ma et al., 2016). Recently, TUDCA and another chemical chaperone, phenylbutyrate (PB), were the subjects of a multicenter, randomized double-blinded clinical trial to test their safety and efficacy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Paganoni et al., 2020). Although the treatment resulted in slower functional decline than placebo, adverse GI events were noted (Paganoni et al., 2020). In recent, but important studies, evidence from the Randolph laboratory (Han et al., 2021) suggests that high-density-lipoprotein (HDL)-raising drugs may also be a therapeutic option for preventing gut-mediated liver injury. These authors demonstrated that the production of HDL by enterocytes protected the liver from gut-derived LPS leakage in both NASH and alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH).

Other important components of NAFLD-NASH pathogenesis, whose expression by infiltrating macrophages and resident Kupffer cells is induced subsequently to barrier deterioration are inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Naugler et al., 2007; Park et al., 2010). The inhibition of TNF signaling prevents NAFLD and NASH in mice (Wandrer et al., 2020) and TNF stimulates lipid droplet accumulation in human hepatocytes (Todoric et al., 2020), suggesting that TNF inhibition is a viable therapeutic strategy. The effect of TNF inhibitors on ASH and NASH in patients treated for auto-inflammatory diseases was examined and the results were mixed (Spahr et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2020; Zein et al., 2011; Zein and Etanercept Study Group, 2005). The selective activation of IL-6 signaling is more complex, as it can enhance the development of colorectal and liver cancers (Greten et al., 2004; Naugler et al., 2007). Therefore, we have undertaken a novel approach to generate selective IL-6 inhibitors that only block adverse IL-6 signaling and mimics that lack some of the negative effects of IL-6 itself. One such agent, sgp130 (Olamkicept), is a biologic that targets “IL-6 trans-signaling,” the component of IL-6 signaling that causes inflammation (Febbraio et al., 2010). Olamkicept is currently in a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (Schreiber et al., 2021), but we propose that this drug may also have therapeutic utility in NASH because in pre-clinical studies, we found that treating diet-induced obese mice with sgp130Fc ameliorates liver inflammation (Kraakman et al., 2015). Accordingly, we are currently pursuing studies in our mouse model of NASH. The selective blockade of trans-signaling has merit because activation of the membrane-bound IL-6 receptor can be beneficial for metabolic diseases, including NASH, due to barrier repair (Taniguchi et al., 2015; Todoric et al., 2020) and the activation of AMPK (Carey et al., 2006), further reducing hepatic steatosis (Matthews et al., 2010). Therefore, drugs that block the trans-signaling component of IL-6 but activate the membrane-bound IL-6R signaling, are desirable for treating metabolic disease. Accordingly, we developed IC7Fc, a chimera of IL-6 and a related cytokine, cliliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), which stimulates protective gp130 signaling, but cannot induce IL-6 trans-signaling, because it requires a different tripartite signaling complex compared with IL-6 (Findeisen et al., 2019). IC7Fc prevented high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and NAFLD, while preserving muscle mass through YAP activation (Findeisen et al., 2019). We are currently evaluating whether IC7Fc activates YAP in enterocytes and can thereby improve GI barrier function and prevent NASH, in addition to its ability to prevent NAFLD (Findeisen et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that, in certain circumstances, the activation of YAP may enhance colonic adenocarcimas in mice (Deng et al., 2018); therefore, drugs that directly and indiscriminately activate YAP may have limited therapeutic utility. Of note, Lau and coworkers have shown that systemic treatment with the YAP-induced protein CCN1 can enhance protective IL-6 signaling and ameliorate detran sodium sulfate (DSS)-indexed colitis in mice (Choi et al., 2015). These effects of CCN1 were incredibly similar to those of enterocyte-specific gp130 activation (Taniguchi et al., 2015) described earlier. Accordingly, we gave CCN1 to fructose-fed mice and found that it inhibited intestinal inflammation, endotoxemia, and NAFLD-NASH (Todoric et al., 2020). Therefore, these data suggest that targeting CCN1 downstream of YAP is a more viable therapeutic approach.

Other ways to enforce barrier function include the administration of an IL-22-Fc fusion protein (Shohan et al., 2020) and the induction of IL-22 expression with aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonists (Yang et al., 2020). IL-22 is a unique cytokine produced by type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) that acts on epithelial cells located at barrier surfaces. Studies conducted by Stockinger and coworkers have demonstrated that, under certain circumstances, IL-22 can prevent barrier disruption and protect against liver pathologies (Ahlfors et al., 2014; Mastelic et al., 2012; Turner et al., 2013). Others have shown that by stimulating intestinal stem cell proliferation, IL-22 maintains barrier integrity during graft versus host disease (Lindemans et al., 2015). Non-toxic AhR agonists that induce IL-22 production by ILC3 cells also maintain barrier integrity (Duarte et al., 2013; Schiering et al., 2018; Stockinger et al., 2009; Veldhoen et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2020).

As discussed earlier, the gut microbiota is another key component of the gut-liver axis that may play a cardinal, but poorly understood and complex, role in NAFLD-NASH pathogenesis and therefore may provide novel therapeutic opportunities. The concept that probiotics may be useful in NASH treatment was the subject of an extensive review (Lirussi et al., 2007). Preliminary data from two pilot, non-randomized studies suggested that probiotics may be well tolerated, may improve conventional liver function, and may decrease markers of lipid peroxidation. However, the 2007 review concluded that because these clinical trials were not well controlled, it was impossible to support or refute the use of probiotics in NASH. This is not unexpected because the gut microbiota is highly complex, consisting of thousands of different species, some of which are protective, whereas others are facultative pathogens. In addition to systemic endotoxemia (Schreurs et al., 2010) and production of acetate (Zhao et al., 2020), the microbiota is responsible for the generation of secondary bile acids that can have profound effects on liver physiology (Jadhav and Cohen, 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). Recently, the bacterial genus Clostridium was found to be markedly elevated in mice with NASH, resulting in low circulating glycine (Rom et al., 2020), which is associated with insulin resistance and hepatosteatosis (Newgard et al., 2009). Accordingly, Chen and colleagues (Rom et al., 2020) developed a glycine and leucine tripeptide, termed as DT109, whose administration to mice with NASH decreased Clostridium, increased glycine accumulation and attenuated hepatosteatosis. In addition, in a human NASH phase 2 clinical trial, Alderfermin, an engineered fibroblast growth factor 19 analog, which is secreted from the ileum in response to FXR activation and can suppress bile acid activity (Zhou et al., 2014), reduced liver fat with a mild improvement in fibrosis (Harrison et al., 2021). Interestingly, in a recent study, fecal microbiota transplantation from healthy, young vegan donors into patients with obesity and NASH resulted in a change in intestinal microbiota composition, which was associated with beneficial changes in plasma metabolites and markers of NASH (Witjes et al., 2020). Taken together, these findings suggest that microbiota modulation is a promising future approach to NASH treatment and prevention of fructose-induced steatosis. However, the enormous complexity of the gut microbiota requires rigorously controlled additional studies.

FRUCTOSE AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE (CVD)

There is convincing evidence that high fructose intake can increase CVD risk. This may be due, in part, to fructose-enhanced hypertension (Hwang et al., 1987; Hwang et al., 1989). Rodent studies have suggested that this may depend on increased sympathetic activity, accumulation of glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, or a fructose-induced magnesium and/or copper deficiency (Tappy and Lê, 2010). It was also proposed that fructose induces hyperuricemia and that this may not only result in hypertension but can also increase gout prevalence (Ayoub-Charette et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2003). Finally, high fructose intake was suggested to increase jejunal water and sodium chloride absorption through the transporters Slc26a6 and Slc2a5 (Singh et al., 2008). Irrespective of the mechanism, large human cohort studies show that high fructose consumption can increase CVD risk. This was examined in the Framingham Heart Study (6,039 people; mean age 52.9 years), in which participants were free of baseline metabolic syndrome. In this study, high soft drink consumption increased multiple CVD risk factors (Dhingra et al., 2007). Similarly, in a more recent study using the Jackson-Heart study data of African Americans, the consumption of HFCS in soda or fruit drinks (≥3 drinks per day) significantly increased CVD risk (DeChristopher et al., 2020). Although females were somewhat protected compared with men, the Nurse Health study of over 88,000 women also demonstrated that regular consumption of fructose in the form of soft drinks is associated with a higher CVD risk, even after other unhealthful lifestyle or dietary factors were accounted for (Fung et al., 2009).

FRUCTOSE AND CANCER

HFCS consumption, rates of obesity and T2DM, and the incidence of some cancers have increased in parallel during the past 50 years (Currie et al., 2012; Genkinger et al., 2011; Nakagawa et al., 2020). Therefore, it has been difficult to determine whether excessive fructose consumption directly affects cancer. However, several lines of evidence point to fructose being a tumor promoter. First, fructose is absorbed by GLUT5 (Figure 2), and several studies found that GLUT5 is highly expressed in a variety of cancer cell lines (Harris et al., 1992; Mahraoui et al., 1992; Zamora-León et al., 1996). An association between fructose and cancer seems to be most relevant to pancreatic cancer, as suggested by large human associative studies (Hui et al., 2009; Larsson et al., 2006; Michaud et al., 2002; Schernhammer et al., 2005). More recently (Nakagawa et al., 2020), fructose intake was found to be associated with lung adenocarcinoma, myeloma, breast cancer, and glioma, primarily due to aberrant GLUT5 expression and or activity. Recent research conducted by us (Nakagawa et al., 2014; Todoric et al., 2020) and others (Goncalves et al., 2019) demonstrated that high fructose consumption can promote liver and colorectal tumorigenesis. Remarkably, feeding miniscule amounts of fructose to adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-mutant mice, which are predisposed to intestinal tumors, markedly increased tumor size and grade, independent of obesity or metabolic syndrome (Goncalves et al., 2019). The mechanism by which fructose acts in this system remains to be identified, as FASN ablation used by the authors can have a general effect on cell viability (Tanosaki et al., 2020). Using the MUP-uPA mouse model of NASH-driven hepatocellular cellular carcinoma (HCC), we demonstrated that consumption of a high-fructose diet led to HCC development independent of obesity (Todoric et al., 2020). However, HCC induction may not be due to a direct effect of fructose on the hepatocyte, as it was completely inhibited when the mice were treated with either broad-spectrum antibiotics or barrier-reinforcing agents (Todoric et al., 2020). Another mechanism by which fructose consumption can enhance HCC development is the induction of liver fibrosis associated with increased production of TGF-β and IL-21 that convert naive B cells to immunosuppressive IgA+ plasma cells, which also accumulate in the livers of patients with NASH (Shalapour et al., 2017). Through the expression of IL-10 and PD ligand 1 (PD-L1), IgA+ plasma cells dismantle hepatic immunosurveillance mediated by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL). This can be avoided either by IgA+ plasma cell depletion or by treating the mice with a neutralizing PD-L1 antibody (Shalapour et al., 2017), which was proven to be effective in human HCC (El-Khoueiry et al., 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

It has become increasingly clear that the excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and HFCS has contributed to the escalating incidence of metabolic diseases, such as T2D, NASH, CVD, and certain cancers. Although the underlying mechanisms are just being elucidated and the relevance of small animal models is being debated, it is obvious that fructose-induced liver diseases depend on a multicomponent pathogenic cascade. Although an altered liver lipid metabolism is the endpoint for this cascade, recent evidence has highlighted the importance of fructose-induced alterations in GI physiology, including barrier deterioration and dysbiosis. The downward self-amplifying spiral triggered by fructose may also apply to other disease-provoking macronutrients, such as excess fat or cholesterol. Recognizing the importance of the microbiota, gut barrier disruption, and systemic inflammation in fructose-induced NAFLD-NASH has opened the doors to new therapeutic interventions with these common, but difficult to treat, lifestyle-related diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.A.F. is a Senior Principal Research Fellow at the NHMRC (APP1116936) and is also supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1194141). Research in his laboratory was supported by project grants from the NHMRC (APP1042465, APP1041760, and APP1156511 to M.A.F. and APP1122227 to M.A.F. and M.K.). M.K. is an American Cancer Research Society Professor and holds the Ben and Wanda Hildyard Chair for Mitochondrial and Metabolic Diseases. His research was supported by grants from the NIH (P42ES010337, R01DK120714, R01CA198103, R37AI043477, R01CA211794, and R01CA234128).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

M.K. holds US Patent No. 10034462 B2 on the use of MUP-uPA mice for the study of NASH and NASH-driven HCC. M.A.F. is a co-inventor of IC7Fc and hold patents for this molecule (US 60/920,822; WO/2008/119110 A1).

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Sayed A, Binnert C, Lê KA, Bortolotti M, Schneiter P, and Tappy L (2008). A high-fructose diet impairs basal and stress-mediated lipid metabolism in healthy male subjects. Br. J. Nutr 100, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman RC, Ballard FJ, and Weinhouse S (1967). Purification and properties of rat liver fructokinase. J. Biol. Chem 242, 3360–3365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlfors H, Morrison PJ, Duarte JH, Li Y, Biro J, Tolaini M, Di Meglio P, Potocnik AJ, and Stockinger B (2014). IL-22 fate reporter reveals origin and control of IL-22 production in homeostasis and infection. J. Immunol 193, 4602–4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad U, and Sharma J (2021). Fructose 1-phosphate aldolase deficiency. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldámiz-Echevarría L, de Las Heras J, Couce ML, Alcalde C, Vitoria I, Bueno M, Blasco-Alonso J, Concepción García M, Ruiz M, Suárez R, et al. (2020). Non-alcoholic fatty liver in hereditary fructose intolerance. Clin. Nutr 39, 455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres-Hernando A, Orlicky DJ, Kuwabara M, Ishimoto T, Nakagawa T, Johnson RJ, and Lanaspa MA (2020). Deletion of fructokinase in the liver or in the intestine reveals differential effects on sugar-induced metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab. 32, 117–127.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub-Charette S, Liu Q, Khan TA, Au-Yeung F, Blanco Mejia S, de Souza RJ, Wolever TM, Leiter LA, Kendall C, and Sievenpiper JL (2019). Important food sources of fructose-containing sugars and incident gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open 9, e024171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting FG (1926). An address on diabetes and insulin: being the Nobel lecture delivered at Stockholm on September 15th, 1925. Can. Med. Assoc. J 16, 221–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On H, and Stein Y (1968). Effect of glucose and fructose administration on lipid metabolism in the rat. J. Nutr 94, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone S, Fussell SL, Singh AK, Lucas F, Xu J, Kim C, Wu X, Yu Y, Amlal H, Seidler U, et al. (2009). Slc2a5 (Glut5) is essential for the absorption of fructose in the intestine and generation of fructose-induced hypertension. J. Biol. Chem 284, 5056–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman A, Carvajal-Gonzalez S, Tarabar S, Saxena AR, Esler WP, and Amin NB (2020). Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of a liver-targeting acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor (PF-05221304): a three-part randomized Phase 1 study. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev 9, 514–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendis L, Kreel L, and Williams R (1969). The coeliac axis and its branches in splenomegaly and liver disease. Gut 10, 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, and Popkin BM (2004). Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 79, 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce CR, Hoy AJ, Turner N, Watt MJ, Allen TL, Carpenter K, Cooney GJ, Febbraio MA, and Kraegen EW (2009). Overexpression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 in skeletal muscle is sufficient to enhance fatty acid oxidation and improve high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 58, 550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey AL, Steinberg GR, Macaulay SL, Thomas WG, Holmes AG, Ramm G, Prelovsek O, Hohnen-Behrens C, Watt MJ, James DE, et al. (2006). Interleukin-6 increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in humans and glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in vitro via AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetes 55, 2688–2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CY, Battat R, Al Khoury A, Restellini S, Sebastiani G, and Bessissow T (2016). Co-existence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease: a review article. World J. Gastroenterol 22, 7727–7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman CI (1993). GLUT2 is the transporter for fructose across the rat intestinal basolateral membrane. Gastroenterology 105, 1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YE, Kim DK, Seo W, Gao B, Yoo SH, and Song BJ (2021). Fructose promotes leaky gut, endotoxemia, and liver fibrosis through ethanol-inducible cytochrome P450–2E1- mediated oxidative and nitrative stress. Hepatology 73, 2180–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Kim KH, and Lau LF (2015). The matricellular protein CCN1 promotes mucosal healing in murine colitis through IL-6. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 1285–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colville CA, Seatter MJ, Jess TJ, Gould GW, and Thomas HM (1993). Kinetic analysis of the liver-type (GLUT2) and brain-type (GLUT3) glucose transporters in Xenopus oocytes: substrate specificities and effects of transport inhibitors. Biochem. J 290, 701–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzo R, Bianco F, Falcone I, Coppola P, Liverini G, and Iossa S (2013). Increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis and mitochondrial efficiency in a model of obesity induced by diets rich in fructose. Eur. J. Nutr 52, 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, and Morgan CL (2012). Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care 35, 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debosch BJ, Chen Z, Saben JL, Finck BN, and Moley KH (2014). Glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) mediates fructose-induced de novo lipogenesis and macrosteatosis. J. Biol. Chem 289, 10989–10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChristopher LR, Auerbach BJ, and Tucker KL (2020). High fructose corn syrup, excess-free-fructose, and risk of coronary heart disease among African Americans- the Jackson Heart Study. BMC Nutr. 6, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deerr N (1949). The History of Sugar, Volume 1 (Chapman & Hall; ). [Google Scholar]

- Deng F, Peng L, Li Z, Tan G, Liang E, Chen S, Zhao X, and Zhi F (2018). YAP triggers the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway and promotes enterocyte self-renewal, regeneration and tumorigenesis after DSS-induced injury. Cell Death Dis. 9, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB, D’Agostino RB, Gaziano JM, and Vasan RS (2007). Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation 116, 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotimas JR, Lee AW, Schmider AB, Carroll SH, Shah A, Bilen J, Elliott KR, Myers RB, Soberman RJ, Yoshioka J, and Lee RT (2016). Diabetes regulates fructose absorption through thioredoxin-interacting protein. eLife 5, e18313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douard V, and Ferraris RP (2008). Regulation of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 295, E227–E237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JH, Di Meglio P, Hirota K, Ahlfors H, and Stockinger B (2013). Differential influences of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor on Th17 mediated responses in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 8, e79819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling THR, et al. (2017). Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 389, 2492–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Santamaria R, Vitagliano L, Ieno L, Viola A, Fiori L, Parenti G, Zancan L, Zagari A, and Salvatore F (2004). Six novel alleles identified in Italian hereditary fructose intolerance patients enlarge the mutation spectrum of the aldolase B gene. Hum. Mutat 24, 534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Rose-John S, and Pedersen BK (2010). Is interleukin-6 receptor blockade the Holy Grail for inflammatory diseases? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 87, 396–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Reibe S, Shalapour S, Ooi GJ, Watt MJ, and Karin M (2019). Preclinical models for studying NASH-driven HCC: how useful are they? Cell Metab. 29, 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris RP, Hsiao J, Hernandez R, and Hirayama B (1993). Site density of mouse intestinal glucose transporters declines with age. Am. J. Physiol 264, G285–G293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris RP, Choe JY, and Patel CR (2018). Intestinal absorption of fructose. Annu. Rev. Nutr 38, 41–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen M, Allen TL, Henstridge DC, Kammoun H, Brandon AE, Baggio LL, Watt KI, Pal M, Cron L, Estevez E, et al. (2019). Treatment of type 2 diabetes with the designer cytokine IC7Fc. Nature 574, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, and Hu FB (2009). Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 89, 1037–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geidl-Flueck B, and Gerber PA (2017). Insights into the hexose liver metabolism-glucose versus fructose. Nutrients 9, 1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geidl-Flueck B, Hochuli M, Németh Á, Eberl A, Derron N, Köfeler HC, Tappy L, Berneis K, Spinas GA, and Gerber PA (2021). Fructose- and sucrose- but not glucose-sweetened beverages promote hepatic de novo lipogenesis: a randomized controlled trial. J. Hepatol 75, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, Calle EE, English DR, Folsom AR, Freudenheim JL, Fuchs CS, et al. (2011). A pooled analysis of 14 cohort studies of anthropometric factors and pancreatic cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 129, 1708–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedeke L, Bates J, Vatner DF, Perry RJ, Wang T, Ramirez R, Li L, Ellis MW, Zhang D, Wong KE, et al. (2018). Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibition reverses NAFLD and hepatic insulin resistance but promotes hypertriglyceridemia in rodents. Hepatology 68, 2197–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves MD, Lu C, Tutnauer J, Hartman TE, Hwang SK, Murphy CJ, Pauli C, Morris R, Taylor S, Bosch K, et al. (2019). High-fructose corn syrup enhances intestinal tumor growth in mice. Science 363, 1345–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, and Karin M (2004). IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 118, 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JA, Liu W, Perez S, Xing G, Sonnenberg G, Kou K, Blatnik M, Allen R, Weng Y, Vera NB, et al. (2021). Pharmacologic inhibition of ketohexokinase prevents fructose-induced metabolic dysfunction. Mol. Metab 48, 101196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YH, Onufer EJ, Huang LH, Sprung RW, Davidson WS, Czepie-lewski RS, Wohltmann M, Sorci-Thomas MG, Warner BW, and Randolph GJ (2021). Enterically derived high-density lipoprotein restrains liver injury through the portal vein. Science 373, 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannou SA, Haslam DE, McKeown NM, and Herman MA (2018). Fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Invest 128, 545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover LM, and White JS (1993). Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 58 (Supplement), 724S–732S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DS, Slot JW, Geuze HJ, and James DE (1992). Polarized distribution of glucose transporter isoforms in Caco-2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 7556–7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SA, Neff G, Guy CD, Bashir MR, Paredes AH, Frias JP, Younes Z, Trotter JF, Gunn NT, Moussa SE, et al. (2021). Efficacy and safety of Aldafermin, an engineered FGF19 analog, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 160, 219–231.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, Huang D, McArthur D, Nissen N, Boros LG, and Heaney AP (2009). Direct spectrophotometric determination of serum fructose in pancreatic cancer patients. Pancreas 38, 706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IS, Ho H, Hoffman BB, and Reaven GM (1987). Fructose-induced insulin resistance and hypertension in rats. Hypertension 10, 512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IS, Huang WC, Wu JN, Shian LR, and Reaven GM (1989). Effect of fructose-induced hypertension on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and atrial natriuretic factor. Am. J. Hypertens 2, 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka K, Bruick RK, Liang G, Horton JD, and Uyeda K (2004). Deficiency of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) reduces lipogenesis as well as glycolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7281–7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimoto T, Lanaspa MA, Le MT, Garcia GE, Diggle CP, Maclean PS, Jackman MR, Asipu A, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Kosugi T, et al. (2012). Opposing effects of fructokinase C and A isoforms on fructose-induced metabolic syndrome in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4320–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav K, and Cohen TS (2020). Can you trust your gut? Implicating a disrupted intestinal microbiome in the progression of NAFLD/NASH. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 592157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, Hui S, Lu W, Cowan AJ, Morscher RJ, Lee G, Liu W, Tesz GJ, Birnbaum MJ, and Rabinowitz JD (2018). The small intestine converts dietary fructose into glucose and organic acids. Cell Metab 27, 351–361.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, Wada S, Yang S, Gosis B, Zeng X, Zhang Z, Shen Y, Lee G, Arany Z, and Rabinowitz JD (2020). The small intestine shields the liver from fructose-induced steatosis. Nat. Metab 2, 586–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, Nadeau KJ, Green M, Roncal C, Nakagawa T, Kuwabara M, Sato Y, Kang D-H, et al. (2018). Fructose and sugar: a major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol 68, 1063–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Willment A, Patel SS, Sun X, Song M, Mannery YO, Kosters A, McClain CJ, and Vos MB (2014). Fructose induced endotoxemia in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Hepatol 2014, 560620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Kang DH, Feig D, Kivlighn S, Kanellis J, Watanabe S, Tuttle KR, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Herrera-Acosta J, and Mazzali M (2003). Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension 41, 1183–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Rivard C, Lanaspa MA, Otabachian-Smith S, Ishimoto T, Cicerchi C, Cheeke PR, Macintosh B, and Hess T (2013). Fructokinase, fructans, intestinal permeability, and metabolic syndrome: an equine connection? J. Equine Vet. Sci 33, 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Andrews P, and Lanaspa MA (2017). Perspective: a historical and scientific perspective of sugar and its relation with obesity and diabetes. Adv. Nutr 8, 412–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslin EP, and Lahey FH (1934). Diabetes and hyperthyroidism. Ann. Surg 100, 629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun HL, Chabanon H, Hainault I, Luquet S, Magnan C, Koike T, Ferré P, and Foufelle F (2009). GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress-induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest 119, 1201–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S, Adams DH, and Lalor PF (2012). Hepatic expression and cellular distribution of the glucose transporter family. World J. Gastroenterol 18, 6771–6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh K, Wylie AT, Tucker KL, Hamp TJ, Gharaibeh RZ, Fodor AA, and Cullen JM (2013). Dietary fructose induces endotoxemia and hepatic injury in calorically controlled primates. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 98, 349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazumi T, Vranic M, and Steiner G (1986). Triglyceride kinetics: effects of dietary glucose, sucrose, or fructose alone or with hyperinsulinemia. Am. J. Physiol 250, E325–E330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellett GL, and Helliwell PA (2000). The diffusive component of intestinal glucose absorption is mediated by the glucose-induced recruitment of GLUT2 to the brush-border membrane. Biochem. J 350, 155–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan TA, and Sievenpiper JL (2016). Controversies about sugars: results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on obesity, cardiometabolic disease and diabetes. Eur. J. Nutr 55, 25–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CW, Addy C, Kusunoki J, Anderson NN, Deja S, Fu X, Burgess SC, Li C, Ruddy M, Chakravarthy M, et al. (2017a). Acetyl CoA carboxylase inhibition reduces hepatic steatosis but elevates plasma triglycerides in mice and humans: a bedside to bench investigation. Cell Metab. 26, 576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Astapova II, Flier SN, Hannou SA, Doridot L, Sargsyan A, Kou HH, Fowler AJ, Liang G, and Herman MA (2017b). Intestinal, but not hepatic, ChREBP is required for fructose tolerance. JCI Insight 2, e96703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Garcia-Carbonell R, Yamachika S, Zhao P, Dhar D, Loomba R, Kaufman RJ, Saltiel AR, and Karin M (2018). ER stress drives lipogenesis and steatohepatitis via caspase-2 activation of S1P. Cell 175, 133–145.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Moon JS, Kim MJ, Seong MW, Park SS, and Ko JS (2021). Hereditary fructose intolerance diagnosed in adulthood. Gut Liver 15, 142–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, and Ogden CL (2013). Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 98, 180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klurfeld DM, Foreyt J, Angelopoulos TJ, and Rippe JM (2013). Lack of evidence for high fructose corn syrup as the cause of the obesity epidemic. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 37, 771–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraakman MJ, Kammoun HL, Allen TL, Deswaerte V, Henstridge DC, Estevez E, Matthews VB, Neill B, White DA, Murphy AJ, et al. (2015). Blocking IL-6 trans-signaling prevents high-fat diet-induced adipose tissue macrophage recruitment but does not improve insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 21, 403–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally JSV, Ghoshal S, DePeralta DK, Moaven O, Wei L, Masia R, Erstad DJ, Fujiwara N, Leong V, Houde VP, et al. (2019). Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase by phosphorylation or the inhibitor ND-654 suppresses lipogenesis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Metab. 29, 174–182.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertz J, Weiskirchen S, Landert S, and Weiskirchen R (2017). Fructose: a dietary sugar in crosstalk with microbiota contributing to the development and progression of non-alcoholic liver disease. Front. Immunol 8, 1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaspa MA, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Choi YJ, Cicerchi C, Kanbay M, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Ishimoto T, Li N, Marek G, Duranay M, et al. (2012). Uric acid induces hepatic steatosis by generation of mitochondrial oxidative stress: potential role in fructose-dependent and -independent fatty liver. J. Biol. Chem 287, 40732–40744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaspa MA, Andres-Hernando A, Orlicky DJ, Cicerchi C, Jang C, Li N, Milagres T, Kuwabara M, Wempe MF, Rabinowitz JD, et al. (2018). Ketohexokinase C blockade ameliorates fructose-induced metabolic dysfunction in fructose-sensitive mice. J. Clin. Invest 128, 2226–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, and Wolk A (2006). Consumption of sugar and sugar-sweetened foods and the risk of pancreatic cancer in a prospective study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 84, 1171–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, and Tolan DR (1999). Screening for hereditary fructose intolerance mutations by reverse dot-blot. Mol. Cell. Probes 13, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis N, and Tsochatzis E (2017). Current and future treatment options in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 11, 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, and Glimcher LH (2008). Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science 320, 1492–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemans CA, Calafiore M, Mertelsmann AM, O’Connor MH, Dudakov JA, Jenq RR, Velardi E, Young LF, Smith OM, Lawrence G, et al. (2015). Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature 528, 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lirussi F, Mastropasqua E, Orando S, and Orlando R (2007). Probiotics for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and/or steatohepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 1, CD005165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R, Noureddin M, Kowdley KV, Kohli A, Sheikh A, Neff G, Bhandari BR, Gunn N, Caldwell SH, Goodman Z, et al. (2021). Combination therapies including Cilofexor and Firsocostat for bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis attributable to NASH. Hepatology 73, 625–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyssiotis CA, and Cantley LC (2013). Metabolic syndrome: F stands for fructose and fat. Nature 502, 181–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Zeng M, Han Y, Yan H, Tang H, Sheng J, Hu H, Cheng L, Xie Q, Zhu Y, et al. (2016). A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial comparing the efficacy and safety of TUDCA and UDCA in Chinese patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Med. (Baltim.) 95, e5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahraoui L, Rousset M, Dussaulx E, Darmoul D, Zweibaum A, and Brot-Laroche E (1992). Expression and localization of GLUT-5 in Caco-2 cells, human small intestine, and colon. Am. J. Physiol 263, G312–G318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolescu AR, Witkowska K, Kinnaird A, Cessford T, and Cheeseman C (2007). Facilitated hexose transporters: new perspectives on form and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 22, 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastelic B, do Rosario AP, Veldhoen M, Renauld JC, Jarra W, Sponaas AM, Roetynck S, Stockinger B, and Langhorne J (2012). IL-22 protects against liver pathology and lethality of an experimental blood-stage malaria infection. Front. Immunol 3, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka T, Shimano H, Yahagi N, Amemiya-Kudo M, Okazaki H, Tamura Y, Iizuka Y, Ohashi K, Tomita S, Sekiya M, et al. (2004). Insulin-independent induction of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c expression in the livers of streptozotocin-treated mice. Diabetes 53, 560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews VB, Allen TL, Risis S, Chan MH, Henstridge DC, Watson N, Zaffino LA, Babb JR, Boon J, Meikle PJ, et al. (2010). Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop hepatic inflammation and systemic insulin resistance. Diabetologia 53, 2431–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes PA (1993). Intermediary metabolism of fructose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 58 (Supplement), 754S–765S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanson KJ, Zukley L, Lowndes J, Nguyen V, Angelopoulos TJ, and Rippe JM (2007). Effects of high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose consumption on circulating glucose, insulin, leptin, and ghrelin and on appetite in normal-weight women. Nutrition 23, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud DS, Liu S, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, and Fuchs CS (2002). Dietary sugar, glycemic load, and pancreatic cancer risk in a prospective study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 94, 1293–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Alvarez MC, Ricardo-Silgado ML, Lemus HN, González-Devia D, and Mendivil CO (2019). Fructosuria and recurrent hypoglycemia in a patient with a novel c.1693T>a variant in the 3’ untranslated region of the aldolase B gene. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep 7, 2050313X18823098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Umemura A, Taniguchi K, Font-Burgada J, Dhar D, Ogata H, Zhong Z, Valasek MA, Seki E, Hidalgo J, et al. (2014). ER stress cooperates with hypernutrition to trigger TNF-dependent spontaneous HCC development. Cancer Cell 26, 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Lanaspa MA, Millan IS, Fini M, Rivard CJ, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Andres-Hernando A, Tolan DR, and Johnson RJ (2020). Fructose contributes to the Warburg effect for cancer growth. Cancer Metab 8, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, and Karin M (2007). Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 317, 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF, Haqq AM, Shah SH, Arlotto M, Slentz CA, et al. (2009). A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab 9, 311–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppelt SA, Sennott EM, and Tolan DR (2015). Aldolase-B knockout in mice phenocopies hereditary fructose intolerance in humans. Mol. Genet. Metab 114, 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler W (1893). The Principles and Practice of Medicine (D Appleton and Co; ), pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Paganoni S, Macklin EA, Hendrix S, Berry JD, Elliott MA, Maiser S, Karam C, Caress JB, Owegi MA, Quick A, et al. (2020). Trial of sodium phenylbutyrate-taurursodiol for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 919–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, Osterreicher CH, Takahashi H, and Karin M (2010). Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 140, 197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, and Dingfelder CS (2008). Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. J. Nutr 138, 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C, Douard V, Yu S, Gao N, and Ferraris RP (2015). Transport, metabolism, and endosomal trafficking-dependent regulation of intestinal fructose absorption. FASEB J. 29, 4046–4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perin N, Keelan M, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Clandinin MT, and Thomson AB (1997). Ontogeny of intestinal adaptation in rats in response to isocaloric changes in dietary lipids. Am. J. Physiol 273, G713–G720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KF, Laurent D, Yu C, Cline GW, and Shulman GI (2001). Stimulating effects of low-dose fructose on insulin-stimulated hepatic glycogen synthesis in humans. Diabetes 50, 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MJ, Little JA, and Ptak TW (1968). Subcellular pathology of hereditary fructose intolerance. Am. J. Med. 44, 910–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MJ, Hetenyi G Jr., and Adachi F (1970). Ultrastructural hepatocellular alterations induced by in vivo fructose infusion. Lab. Invest 22, 370–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]