Abstract

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is a core neuropsychiatric condition. To date, promising yet inconsistently identified neural circuit profiles have been observed in patients with FND, suggesting important gaps remain in our systems-level neurobiological understanding. As such, other important physiological variables including autonomic, endocrine and inflammation findings need to be contextualized for a more complete mechanistic picture. Here, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of available case-control and cohort studies in FND. PubMed, PsycINFO and Embase databases were searched from January 1, 1900 to September 1, 2020 for studies that investigated autonomic, endocrine and/or inflammation markers in patients with FND. Sixty-six of 2,056 screened records were included in the review representing 1,699 patients, with data from 23 articles used in meta-analyses. Findings show that children/adolescents with FND vs. healthy controls (HCs) have increased resting heart rate; there is also a tendency towards reduced resting heart rate variability in patients with FND across the lifespan vs. HCs. In adults, peri-ictal heart rate differentiated those with functional seizures from individuals with epileptic seizures. Other autonomic and endocrine profiles in patients with FND were heterogeneous, with several studies highlighting the importance of individual differences. Inflammation research in FND remains in its early stages. Moving forward, there is a need to use larger sample sizes to consider the complex interplay between functional neurological symptoms and behavioral, psychological, autonomic, endocrine, inflammation, neuroimaging and epigenetic/genetic data. More research is also needed to determine whether FND is mechanistically (and etiologically) similar or distinct across phenotypes.

Keywords: functional neurological disorder, conversion disorder, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, heart rate, cortisol, inflammation

Introduction

Functional neurological disorder (FND) is a condition at the intersection of neurology and psychiatry{1}. While of interest to early clinical neuroscience leaders such as Jean Martin Charcot and Sigmund Freud, FND was neglected by clinicians and academics alike throughout much of the late 20th century. Nonetheless, FND is the second most common condition seen in outpatient neurology clinics, a finding compounded by observations of high healthcare costs and poor prognoses in many patients{2–4}. Renewed interest in the field has been promoted by recognition that FND can be reliably diagnosed using physical examination signs and semiological features{1, 5}. This high diagnostic specificity has led to a surge in research on the pathophysiology of FND, particularly using brain imaging approaches{6, 7}. Promising yet inconsistently identified neural circuit profiles have been observed to date{6}, suggesting that there are important gaps in our systems-level understanding of this condition. As such, there is a need to contextualize autonomic, endocrine and inflammation findings for a more complete mechanistic understanding of FND. Such efforts offer the promise of developing novel biologically-informed treatments.

Some functional neuroimaging studies across the motor spectrum of FND (including functional seizures (FND-seiz)) have identified several noteworthy findings compared to healthy controls: i) enhanced amygdala reactivity to affectively-valenced stimuli{8, 9}; ii) increased task and resting-state connectivity between salience network and motor control circuits{9–11}; and iii) hypoactivation and altered connectivity of the right temporoparietal junction/inferior parietal lobule{12–14}. Additionally, resting-state functional connectivity studies have found positive correlations between salience network – motor control network connectivity strength and patient-reported symptom severity{11, 15}. However, findings have been inconsistent across studies. For example, not all studies have observed increased coupling between salience and motor control networks{16}.

Several grey and white matter characterization studies in FND samples have also implicated similar brain networks to those identified using functional neuroimaging, including two studies reporting that decreased white matter integrity of the stria terminalis/fornix (an amygdala outflow tract) correlated with FND illness duration and age of onset{17, 18}. Nonetheless, structural neuroimaging findings have also been inconsistently identified across studies{6}. Thus, while the neuroimaging literature suggests that some patients with FND have functional and structural alterations in brain areas implicated in emotion/threat processing, homeostasis, salience, arousal, agency and motor control, the observed heterogeneity limits conclusions about specific FND neural signatures at present time. This may relate to differences in disease-related mechanisms across patients, phenotypic heterogeneity, concurrently present neuropsychiatric disorders, medication effects, and/or compensatory neuroplastic effects.

Given salience and limbic network involvement in some patients with FND, characterizing sympathetic/parasympathetic activity (e.g., heart-rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), skin conductance etc. (see Box 1)) and endocrine hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis markers are important gaps in the literature. Similarly, quantifying inflammation profiles, which are known to modulate salience and limbic networks{19, 20}, would add mechanistic value. Here, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively characterize the available autonomic, endocrine and inflammation literature in patients with FND. In the discussion, we contextualize this literature with other available pathophysiology considerations.

Box 1. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Parameter Definitions.

TP, total power; SDNN, standard deviation of normal to normal beats; rMSSD, root mean square of the successive differences; HF, high frequency; CVI, cardiovagal index; LF, low frequency; CSI, cardiosympathetic index.

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| General parameters | Heartbeat fluctuations irrespective of autonomic innervation. |

| TP | The sum of HF and LF. |

| R-R or Interbeat Intervals | The time elapsed between consecutive heartbeats. |

| SDNN | The R-R intervals of normal heartbeats; ectopic beats are excluded. |

| Parasympathetic parameters | Heart rate changes mediated by vagal (parasympathetic) tone. |

| rMSSD | An index of parasympathetic tone less prone to respiratory changes. |

| HF or Respiratory Sinus Arrythmia | Heart rate changes that reflect the respiratory cycle patterns. |

| CVI | A measure of HF with less physiological noise. |

| Sympathetic parameters | Heart rate changes associated with sympathetic activity. |

| LF | A measure predominantly driven by the sympathetic nervous system. |

| CSI | A LF-related measure with less physiological noise. |

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We followed PRISMA guidelines for performing a systematic review and meta-analysis and registered the study in PROSPERO (ID# CRD42020157679). The databases PubMed, PsycINFO and Embase were searched from January 1, 1900 to September 1, 2020 using the following search terms: (“functional neurological disorder” OR “functional neurological symptom disorder” OR “conversion disorder” OR “psychogenic” OR “pseudoseizure” OR “non-epileptic” OR “dissociative seizures” OR “hysteri*” OR “non-organic”) AND (“heart rate” OR “heart rate variability” OR “electrodermal” OR “skin conductance” OR “autonomic” OR “sympathetic” OR “parasympathetic” OR “neuroendocrine” OR “hormone” OR “cortisol” OR “HPA” OR “hypothalamic pituitary adrenal” OR “amylase” OR “brain-derived neurotrophic factor” OR “BDNF” OR “glucocorticoid” OR “inflammat*” OR “interleukin-*” OR “immune” OR “autoimmun*” OR “innate immun*” OR “TNF” OR “C reactive protein” OR “erythrocyte sedimentation rate” OR “lactate” OR “anion gap”). Additional potentially eligible articles were identified from those known to the authors and following inspection of reference lists.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: case-control or cohort studies with at least 5 adult or pediatric participants with FND who had an autonomic, endocrine, and/or inflammation data points measured. Case reports, abstracts, dissertations, review articles, and papers written in a language other than English were excluded. Studies that exclusively measured imaging, electroencephalographic or prolactin were also excluded and previously reviewed elsewhere{5, 6, 21}; publications in somatic symptom disorders, somatoform pain, somatization disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, and the spectrum of functional medical disorders (e.g. fibromyalgia) were also excluded.

Data Extraction and Systematic Review

EndNote was used to compile abstracts. After removing duplicates, S.P.E. and J.M. independently applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to determine articles to be read. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by D.L.P. Data regarding demographics, outcome measurements, and results presented in the text, tables or graphs were systematically extracted and reviewed. Quality and bias was assessed using the National Institute of Health Study Quality Assessment Tools guidelines (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) for cohort and case-control studies{22}. All eligible articles were included in the systematic review.

Meta-Analysis

At least four independent articles had to report findings on a given autonomic, endocrine or inflammation finding to be pooled and added in the meta-analysis. Since only a limited number of studies recorded these data in FND populations, we used a transdiagnostic approach across FND subtypes. Authors were contacted when data was not explicitly reported as measures of central tendency or dispersion, and, in three instances, between-group comparisons (i.e., Student t-test) were performed when absent in the article{23–25}. We followed Cochrane guidelines for data preparation, such as: obtaining standard deviations from standard errors, confidence intervals, t-values and p-values; and using transformed data.

For all meta-analyses, we used the software Stata/IC 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). With the command meta we calculated effect sizes (θ): mean difference (MD) for raw data and the Hedge’s g standardized mean difference (SMD) for transformed data. To measure precision, we used a 95% confidence interval (CI) with unequal variances for mean difference comparisons. All estimations were done with the random-effects model after testing homogeneity (Q), heterogeneity (H2) and variation (I2). Between-study variability (τ2) was computed with the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) model and used to calculate the weight of every primary study. Furthermore, analyses on peri-ictal time points (pre-ictal, ictal, and post-ictal) in FND-seiz studies were also performed. Funnel plots and sensitivity analyses evaluated publication bias and estimated the effects of individual studies.

Results

Sixty-six articles as described in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) were included in the systematic review, with 23 articles included in the meta-analysis. In general, most studies reported a clear research question and inclusion/exclusion criteria but were typically not blinded to group identity and sample sizes were small. Additionally, more recently published studies better adhered to quality standards. See Supplementary Table 1 for more details pertaining to study quality and Supplementary Figures 1–7 for funnel plot and sensitivity analysis results.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Article Selection.

FND, Functional Neurological Disorder.

Autonomic Findings

Baseline HR

Eight articles measured baseline mean HR in patients with FND compared to healthy controls (HCs){26–30}, normative data{31}, or neurological populations{32, 33}. In adults, baseline HR findings have been inconsistent. Compared to HCs, FND-seiz (n=20) and functional movement disorder (FND-movt, n=20) samples did not show group-level resting HR differences{30}; however, patients with FND-movt (n=35) exhibited a higher baseline HR compared to HCs in another study {29}. Across two pediatric cohorts (mixed FND and FND-seiz), baseline HR was increased vs. HCs{26–28}. A third pediatric FND-seiz sample (n=33) reported that 18% had a baseline HR in the 90th percentile of expected norms, a finding that correlated with seizure frequency{31}. Additionally, there were no baseline HR differences in 9 patients with mixed FND vs. neurological controls (e.g., cervical lesion){32}, or between patients with functional (n=44) vs. neural-mediated syncope (n=44){33}.

Applying a meta-analysis to the four FND studies (across 5 cohorts – one study reported FND-movt and FND-seiz data separately) vs. HCs, there was no statistically significant effect of group on baseline mean HR (mean difference [95% confidence interval]: 5.08 [-0.87, 11.03], Figure. 2). However, based on the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure. 1), removal of the Demartini et al (2016) FND-seiz cohort would result in a statistically significant effect of FND group identity on increased baseline mean HR (MD [95% CI]: 7.43 [2.69, 12.17], Figure. 2){30}.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Baseline Heart Rate Mean Difference between Patients with Functional Neurological Disorder vs. Healthy Controls.

Panel A. Forest plot of baseline heart rate mean difference between functional neurological disorder vs. healthy control cohorts. Panel B. Forest plot of baseline heart rate mean difference between functional neurological disorder vs. healthy control cohorts, when the FND-seiz cohort in Demartini et al., 2016 is removed based on the sensitivity analysis results (see Supplementary Figure 1). FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; HC, Healthy Control; CI, Confidence Interval; Mean Diff, Mean Difference; θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Task-Related HR

Five studies measured mean HR in patients with FND vs. HCs during task performance{26, 32, 34–36}. Across cognitive and affective paradigms (i.e., Stroop, emotional Stroop, low and high stress mathematics), two FND-seiz cohorts showed no-group level differences in task-related HR{34, 35}, although interestingly patients with FND-seiz reporting higher levels of perceived stress exhibited smaller HR changes{35}. Conversely, another study identified that patients with FND-seiz showed a shorter HR deacceleration amplitude vs. HCs during visual emotion processing{36}. Compared to neurological controls, no task-related HR differences were observed in patients with mixed FND symptoms during several tasks (i.e., illness interview, word-association task, presentation of physical stressors){32}. In a mixed pediatric FND cohort, higher HR was observed during 3 tasks (i.e., auditory oddball, Go/No-Go, facial emotion-perception) compared to HCs{26}; additionally, HCs showed greater HR increases during auditory oddball and Go/No-Go tasks compared to pediatric FND patients{26}.

Peri-Ictal or Event-Related HR

Five FND-seiz studies measured mean HR during pre-ictal, ictal, and post-ictal periods{23, 37–40}. Compared to patients with epileptic seizures (ES){23, 37–39}, studies showed a lower HR in FND-seiz pre-ictally{23, 37}, ictally{23, 37, 39}, and/or post-ictally{23, 37, 38}. Also, a within-group study found higher pre-ictal and decreased post-ictal HR in FND-seiz relative to their baseline HR{40}. In 66 symptomatic children/adolescents with mixed FND, increased mean HRs were observed compared to HCs{41}.

In a meta-analysis of case-control studies{23, 37–39}, patients with FND-seiz were more likely to have a lower mean HR than individuals with ES ictally and post-ictally (MD [95% CI]: −21.72 [−22.77, −20.66] and −12.47 [−20.01, −4.94] respectively, Figure. 3). Considering all peri-ictal time points, patients with FND-seiz also showed a significant overall lower mean HR (MD [95% CI]: −12.65 [−20.20, −5.11]). See Supplementary Figure. 8 for meta-analysis findings related to within-group peri-ictal comparisons in patients with FND-seiz.

Figure 3. Forest Plot of Peri-ictal Heart Rate Mean Difference between Patients with Functional Seizures vs. Epileptic Seizures.

FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; ES, Epileptic Seizures; CI, Confidence Interval; Mean Diff, Mean Difference; θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Tilt Table Findings

Using tilt table testing, one study observed that patients with functional syncope had significantly higher mean HR 120-seconds prior to losing consciousness vs. those with neurally-mediated syncope{33}; notably, this difference became more pronounced at 30-seconds prior to loss of consciousness where neurally-mediated syncope participants began dropping their HR and functional syncope continued to show escalating HRs{33}. Similarly, a within-group study found that eight patients with functional syncope showed rising HRs immediately preceding loss of consciousness{42}.

Summary of HR Findings

Evidence suggests that patients with pediatric FND have elevated baseline HRs vs. HCs. The study of HR changes during task performance has not robustly identified group-level differences to date. Compared to ES, patients with FND-seiz show decreased HRs ictally and post-ictally (a finding confirmed by our meta-analysis). HR profiles during tilt table testing may aid the differentiation of functional vs. other causes of syncope.

General HRV Parameters

Across studies, results on total power (TP){24, 29, 43}, R-R (inter-beat) interval variability{24, 43–47}, and standard deviation of normal to normal intervals (SDNN){24, 29, 43, 45, 48} are inconsistent. To date, these markers do not reliably differentiate between FND, ES, and HCs during any time points.

HRV Parasympathetic Parameters

Eight FND studies reported the root mean square of successive differences (rMSSD) compared to HCs{26, 29, 34, 41, 43} and/or ES{24, 43, 48, 49}. At rest, lower rMSSD was identified across a variety of FND cohorts compared to HCs{26, 29, 34, 43}, however, this parameter did not differentiate FND-seiz vs. ES cohorts{24, 43, 48, 49}. Pediatric studies found that patients with mixed FND had lower rMSSD during cognitive-affective tasks{26} and while symptomatic compared to HCs{41}. One study found increased rMSSD in FND-seiz during events vs. ES{24}, while another study did not find any group-level ictal differences{49}.

In the meta-analysis between the four case-control articles comparing FND cohorts and HCs at baseline, there was no significant effect of diagnosis on resting rMSSD (SMD [95% CI]: −0.28 [−0.64,0.09], Figure. 4).

Figure 4. Forest Plot of Baseline Heart Rate Variability Standardized Mean Difference between Patients with Functional Neurological Disorder vs. Healthy Controls.

FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; HC, Healthy Controls; rMSSD, Root Mean Square of Successive Differences; CI, Confidence Interval; St. Mean Diff, Standardized Mean Difference; θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Eight studies described high frequency (HF) in FND compared to HCs{26, 29, 43, 46, 47}, ES{24, 43, 49}, mixed FND-seiz/ES{45}, and/or trauma controls{46, 47}. Compared to HCs, studies reported decreased resting HF in mixed FND{26} and FND-seiz{43}, while a separate FND-movt study did not find any group-level differences{29}. During behavioral/cognitive tasks, decreased HF was observed while recalling happy memories{46} and performing auditory oddball and facial recognition tasks{26} in patients with FND-seiz compared to HCs; however, no group-level differences were observed during Go/No-go{26} and affective picture viewing tasks{47}. Three articles did not find differences in resting HF between FND-seiz and ES{24, 43, 49}. However, ictal HF findings in FND-seiz vs. ES have been inconsistent{24, 49}. There were also no resting or peri-ictal HF differences in FND-seiz vs. FND-seiz/ES{45}.

Regarding the cardiovagal index (CVI), one study identified that patients with FND-seiz showed a higher resting CVI compared to HCs{43}, however this measurement did not reliably differentiate FND-seiz from ES{24, 43, 48, 49} or FND-seiz/ES{45} across rest and/or peri-ictal periods.

HRV Sympathetic Parameters

Five studies recorded low frequency (LF) in FND populations{24, 29, 31, 43, 45}. A FND-seiz pediatric cohort had 0.6% LF at baseline{31}. Two studies compared findings with HCs: one identified decreased LF in FND-seiz at rest{43}, however, there were no group differences observed in a FND-movt cohort{29}. Compared to ES, two articles did not find resting LF differences with FND-seiz{24, 43}, but one reported higher LF in the FND-seiz group ictally{24}. A study of 11 FND-seiz vs. 11 FND-seiz/ES patients found that those with FND-seiz had higher LF irrespective of condition (baseline, pre-ictal, ictal or post-ictal){45}.

Five articles reported the cardio sympathetic index (CSI) of participants{24, 43, 45, 48, 49}. At baseline, patients with FND-seiz had higher CSI than HCs{43}, and all but one{48} reported a similar CSI to ES{24, 43, 49} and FND-seiz/ES{45}. Ictally, two studies showed that patients with FND-seiz had a decreased ictal CSI vs. ES{24, 49}, and one reported similar CSI to FND-seiz/ES{45}.

Summary of HRV Findings

Across resting and task conditions, children/adolescents with FND showed lower rMSSD – indicative of reduced parasympathetic tone - compared to HCs. There is also a tendency towards reduced rMSSD in adults with FND vs. HCs. Other indices of HRV have not robustly differentiated FND vs. HCs or ES across studies.

Skin Conductance (Electrodermal) Activity (SCA)

Three studies compared SCA between patients with FND and HCs{28, 50} or ES{51}. Compared to HCs, children/adolescents with mixed FND had increased baseline SCA{28}, while adults with mixed FND did not show resting group-level differences{50}. Compared to ES, FND-seiz had decreased SCA during the peri-ictal period{51}.

Skin Conductance Level (SCL)

Five studies measured SCL at baseline{52}, during baseline and task{31, 53–55}, or only at task{56}. In the article only reporting findings at baseline, nine mixed FND patients had more SCL fluctuations vs. HCs{52}. At baseline and task, three case-control articles reported varied results{53–55}: 40 FND-seiz patients had increased resting SCL compared to HCs after controlling for depression and anti-depressants, with no group differences during a facial affect recognition task{53}. At baseline and while viewing affectively-valenced images, the SCL of 39 patients with FND-seiz co-varied with the depression scores but there were no group differences with HCs at any time point whilst controlling for depression scores {54}. Additionally, during interoceptive accuracy and dissociation-induction tasks there were no SCL differences between mixed FND and HCs{55}. Meanwhile, in a pediatric sample, SCL failed to return to baseline levels following a cognitive stress task in 18 of 31 patients with FND-seiz – a finding that correlated with greater illness duration{31}. In the study that only reported task SCL, patients with mixed FND had significantly higher SCL fluctuations than HCs and psychiatric controls during an auditory task{56}. The meta-analysis of the four case-control studies did not find a significant effect of condition on SCL during task (SMD [95% CI]: −1.82 [−1.40,5.03], Supplementary Figure 9).

3.1.12. Skin Conductance Response (SCR)

Nine studies reported SCR findings at baseline{44, 51}, peri-ictally{44, 51}, and/or during a trigger/task{32, 36, 53, 54, 57–59}. Interictally, one article found that patients with FND-seiz had decreased upper limb SCR compared to ES{44}, while another did not find group differences{51}. Yet, both articles observed that peri-ictally individuals with ES had significantly greater SCR than patients with FND-seiz{44, 51}. Compared to patients with peripheral neuropathies, one study reported that only patients with functional sensory symptoms elicited an SCR to a pinprick{58}. In contrast, another article found that mixed FND patients had increased SCR to specific interview questions and threat-related words, but it did not find overall group differences{32}.

Although there were no group differences between patients with FND-movt and HCs during an auditory stimulus{59}, studies comparing SCR between FND-seiz and HCs reported differentiating task-related findings{36, 53, 54, 57}. Two studies showed that while viewing affectively-valenced images{36} or films{57}, patients with FND-seiz had lower SCR than HCs – a potential marker of decreased (or suppressed) emotion processing in the patient group. Interestingly, in the subgroup of participants with a heightened autonomic response, researchers found that patients with FND-seiz vs. HCs had increased SCR while viewing affectively valenced images{54} and decreased SCR amplitude during a facial emotion recognition task{53}.

Skin Conductance Habituation Rate

Three studies investigated skin conductance habituation rates{56, 59, 60}. A case-control study found that patients with FND-movt vs. HCs had similar habituation to an auditory stimulus{59}; another study reported that, unlike psychiatric and HCs, mixed FND patients exhibited impaired habituation after a trigger{56}. Finally, one article found that trait anxiety scores were closely linked to habituation rate variance in 10 patients with mixed FND{60}.

Startle Response

Two studies compared acoustic startle responses in patients with FND-movt vs. HCs{59, 61}. One found that patients had increased early (physiological) and late (behavioral) startle response probability{59}, while the other did not find group differences in startle response latency or amplitude{61}.

Summary of Skin Conductance and Startle Responses

Overall, SCL, SCR, and startle response in modest sample size studies have demonstrated mixed results - suggesting heterogeneity at rest and during task performance across patients with FND. Early indications suggest that SCRs are decreased peri-ictally in patients with FND-seiz vs. ES.

Endocrine Findings

Cortisol

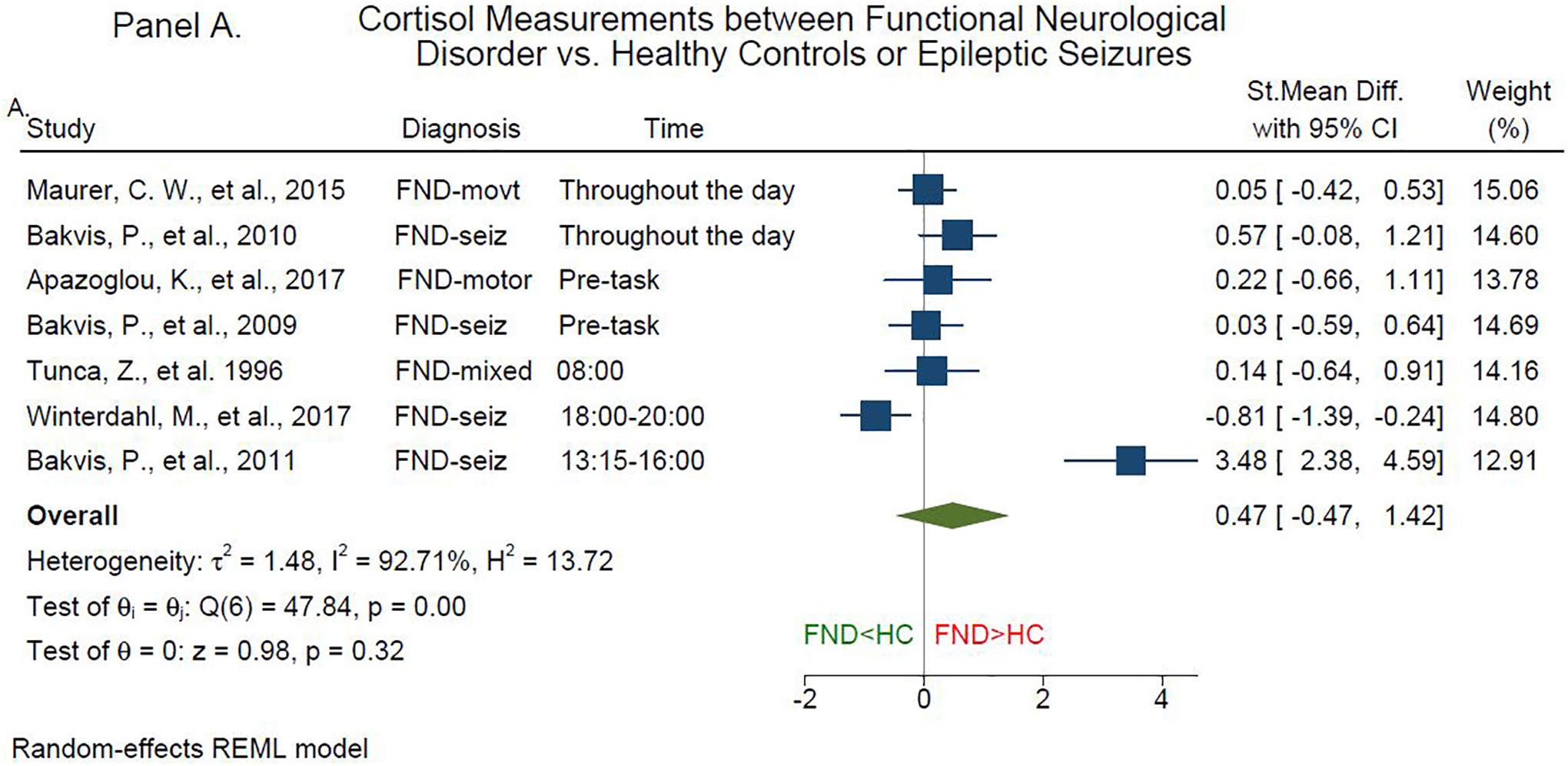

Eleven articles measured baseline cortisol levels{25, 48, 62–71}. There is a near consensus that FND patients have similar baseline cortisol levels compared to HCs{62–69}. In terms of diurnal patterns, six studies did not find group x time differences between patients with mixed FND{69}, FND-movt{62, 65}, or FND-seiz{63, 64, 66, 67} vs. HCs; one study found between-group differences from 12:00 to 20:00{68} in patients with FND-seiz vs. HCs. Notably, the post-hoc analysis of the latter study found that higher salivary cortisol levels in patients with FND-seiz were driven by those who reported past sexual trauma{68}. Our meta-analysis showed that compared to HCs, there was no consistent effect of FND on baseline cortisol levels (SMD [95% CI]: 0.47 [-0.47, 1.42], Figure 5, Panel A).

Figure 5. Forest Plot of Cortisol Standardized Mean Difference between Patients with Functional Neurological Disorder, Epilepsy and Healthy Controls.

Panel A. Forest plot of baseline cortisol standardized mean difference between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. Panel B. Forest plot of baseline cortisol standardized mean difference between functional neurological disorder and epilepsy patients. FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; HC, Healthy Controls; ES, Epileptic Seizures; St. Mean Difference, Standardized Mean Difference; θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

The results from five articles (four cohorts) comparing baseline cortisol in FND-seiz vs. ES suggest no between-group differences{25, 48, 64, 70, 71} across morning{25, 48, 70, 71}, evening{25, 48}, and baseline prior to task performance{64}. In the meta-analysis, the diagnosis of FND vs. ES did not influence baseline cortisol levels (SMD [95% CI]: 0.22 [-0.33, 0.36], Figure 5, Panel B).

Task-Related Cortisol Responses

Five studies compared cortisol levels in FND vs. HCs while performing a task{34, 35, 62–64}. Across a variety of cognitive-affective tasks (i.e., Trier Social Stress, Approach-Avoidance, Emotional Stroop, Awareness check, Stroop Color-Word, or stressful math), no group x time differences were observed{34, 35, 62, 63}. However, one study reported the total salivary cortisol correlated with the adverse life events in patients with FND-movt{62}. Within-group analyses found that salivary cortisol levels positively correlated with attentional bias for angry faces in patients with FND-seiz{64}. In a postural control study, task-related salivary cortisol and movement parameters did not correlate{72}.

Peri-Ictal Cortisol

Two studies compared peri-ictal cortisol levels{25, 73}, with one demonstrating that the FND-seiz group had increased pre-ictal serum cortisol levels compared to ES{25}. Separately, another study found that post-ictal plasma cortisol levels did not differentiate FND-seiz vs. ES{73}.

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH)

Baseline ACTH was measured in three cohorts across five studies {25, 66, 67, 70, 71}. Out of the studies that compared measurements with ES, one group found that at rest patients with FND-seiz had significantly decreased plasma ACTH{70, 71}, while another article suggested no between-group differences in serum samples{25}. Meanwhile, articles that compared serum ACTH at rest between FND-seiz, HCs, and trauma controls determined that from 18:00–20:00 patients with FND-seiz had differentially increased ACTH levels, and that baseline ACTH predicted diagnosis{66, 67}. One study reported that patients with FND-seiz had higher pre-event and lower post-event serum ACTH levels vs. ES{25}.

Amylase

Three articles measured salivary amylase during task performance{35, 62, 72}. One article found that during the Tier Social Stress Task patients with FND-movt had higher baseline amylase levels vs. HCs, without group x time differences across the task{62}. Additionally, during a math performance task, there were no group differences in patients with FND-seiz vs. HCs{35}. Relatedly, amylase levels and stressful mental arithmetic or speech task performances did not correlate across FND-movt and HCs{72}.

Other Endocrine Markers

Compared to HCs, patients with mixed FND had increased urinary epinephrine excretion in the morning and decreased in the afternoon{74–76}. Other studies have investigated between group differences in a range of other markers without compelling findings to date (i.e., neuropeptide Y, norepinephrine, amino-terminal pro-peptide C-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro CNP), ghrelin, nefastin-1, testosterone, progesterone, oxytocin, and estradiol){66, 67, 74–76}.

Summary of Endocrine Findings

While useful for the study of individual differences, there are no compelling data to date to suggest that cortisol and ACTH levels reliably differentiate FND. More studies are needed to investigate the utility of other endocrine markers (i.e. neuropeptide Y, estradiol, testosterone).

Inflammation Findings

Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)

Two studies found that patients with FND had decreased serum BDNF compared to HC{77, 78}, observed in a mixed FND cohort (n=15){77} and in patients with FND-seiz (n=12){78}. Neither study showed FND-related differences when compared to patients with major depression{77} or ES{78}.

Other Inflammation Markers

In 79 children with mixed FND, researchers found that baseline C-Reactive Protein titers were above the normative range in 36 individuals{79}. Group level baseline differences show that patients with mixed FND have increased platelets, IgA and IgM{80, 81}, and decreased lymphocyte count{81}, compared to HCs; no group differences were observed for IgG, TNF-alpha, IL-beta or IL-6 levels{80, 82}. Compared to ES peri-ictally, patients with FND-seiz have decreased white blood cell counts{83}, serum creatine kinase{84–86}, lactate dehydrogenase, and lactate but higher bicarbonate and anion gap levels{86–88}.

Summary of Inflammation Findings

Initial data suggest that serum BDNF levels may differentiate FND vs. HCs, but do not reliably differentiate FND from neurological or psychiatric controls. Overall, potential inflammation markers in FND require more research.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that pediatric patients with FND compared to HCs have increased resting HR and lower parasympathetic tone (rMSSD levels). Autonomic studies in adults with FND yielded mixed results, with initial evidence showing increased baseline HR compared to HCs, decreased peri-ictal HR vs. ES, and differentiating HR patterns on tilt table testing for functional syncope. Although other autonomic and endocrine measurements did not reliably differentiate FND from controls, individual differences in these indices related to clinically meaningful variables. For example, autonomic measurements related to illness duration{31}, symptom severity{31}, perceived stress{35} and mood/anxiety scores{53, 54, 60} in patients with FND. In terms of inflammation data, this literature is in its early stages.

Evidence suggests that children and adolescents with FND have increased autonomic arousal states – a finding that advances our pathophysiological understanding of FND in this subgroup{89}. Compared to HCs, pediatric FND showed increased HR and decreased HRV (rMSSD) at baseline and during cognitive and emotional tasks{26–28, 41}. This suggests that compared to the prominent heterogeneity appreciated in adults with FND, autonomic markers reflecting increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic tone are more consistently present in this sub-population. In one of the few studies analyzing neural circuit and autonomic data concurrently, Kozlowska and colleagues showed that heighted arousal (indexed using HR values) served as a moderator of increased delta power in salience and default mode networks in patients with pediatric FND vs. HCs{28}. Nonetheless, analyses also identified that autonomic activation patterns varied by age, attachment patterns, and clinical phenotype in children/adolescents with FND{26}. These differences underscore the presence of heterogeneity even in pediatric FND, pointing out that there are likely multiple mechanistic pathways through which the stress-system can be recruited{89}. Moving forward, it will be important to incorporate the diathesis-stress model of FND with developmental trajectories through in part the use of longitudinal studies{90}. In the pediatric literature, more work is specifically needed to directly compare children/adolescent with FND to neuropsychiatric controls, including individuals with chronic pain, anxiety, and personality disorders to evaluate the specificity of these promising results.

The systematic review and meta-analysis findings also indicate that peri-ictal HR levels differentiated patients with FND-seiz from those with ES. Specifically, patients with ES showed increased HR during the ictal and post-ictal periods. Other autonomic markers such as SCA and SCR yielded similar results; however, more studies are needed to determine FND-seiz’s effect on these physiological parameters. Nevertheless, the already identified autonomic peri-ictal differences between FND-seiz and ES are noteworthy, particularly given the multi-year delay between symptom onset and diagnosis in patients with FND-seiz. While the capture of typical events on video-electroencephalogram remains the gold standard for diagnosis{5}, newly developed technologies can simultaneously measure HR, HRV and SCA data, offering the opportunity to study the utility of composite diagnostic biomarkers in ambulatory and inpatient settings. Such an approach could help reduce long diagnostic delays that are unfortunately far too common in this population. This wearable technology could also be extended beyond the spectrum of FND-seiz to aid the real-world capture of autonomic data across the full range of patients with FND.

The lack of high-quality studies investigating inflammation profiles in FND is an important gap in the literature, noteworthy given growing evidence showing a role for low grade inflammation in the biology of a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms. For example, in a study investigating the biological and neurocognitive effects of a transient inflammatory response (i.e., typhoid vaccination) in heathy participants, self-reported fatigue correlated with activation changes in the posterior/mid insula and anterior cingulate cortex{20}. In a separate study using the same paradigm, inflammation-associated mood changes correlated with decreased cingulate gyrus-amygdala connectivity{19}. Furthermore, the combined influences of low-grade inflammation and perceived stress increased the risk of developing PTSD in traumatized participants through disruptions in salience, default mode and central executive network connectivity{91}. Given that the onset of FND can be precipitated by physical injury, surgeries or infections{1, 5} (processes that themselves are associated with inflammatory states), it will be impactful to further investigate possible associations between inflammation, brain networks, symptom severity, and prognosis across FND populations.

The heterogeneous findings identified across autonomic, endocrine and inflammation data described in this article underscore the mechanistic, etiological and methodological challenges of pathophysiology research in FND. To help illustrate the mechanistic complexity, an example is the role of the amygdala in this condition. Some studies have identified amygdala hyper-reactivity to affectively-valenced stimuli, with time course data indicating impaired habituation{9} and heightened sensitization{8}. However, using similar paradigms, others have reported no group-level differences or amygdala hypo-activations in patients with FND vs. HCs{92, 93}. Notably, the amygdala has afferent connections to the hypothalamus, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, and periaqueductal gray that drive sympathetic/parasympathetic tone and stress-related hormonal responses. What remains unclear in patients with FND is whether amygdala hyperactivity is coupled with parallel heightened autonomic and endocrine (i.e., cortisol, amylase) profiles, or if there is a mismatch between neurocircuit profiles and downstream responses. This knowledge gap is important because it is possible that heightened amygdala activity could reflect a relative inefficiency in appropriately activating fight-or-flight and other defense response pathways. In support of the latter possibility is evidence that illness duration is associated with reduced integrity of amygdala-based white matter pathways{17, 18}. Conversely, patients with FND have also demonstrated increased information flow (link-step connectivity) between the laterobasal (sensory) amygdala and the periaqueductal gray, suggesting that a limbic fast-track in patients with FND may prime the nervous system for enhanced sympathetic responses{11}.

Mechanistically, another concern in FND research is whether disease-related neurobiological processes are shared or distinct across FND sub-populations (e.g., FND-seiz vs. FND-movt). In support of a transdiagnostic approach are clinical observations that many patients experience mixed symptoms and yet others presenting with one phenotype develop distinct functional neurological symptoms. Notably, imaging profiles correlated to symptom severity in a mixed FND cohort remained significant adjusting for subtypes{11}. Nonetheless, these questions remain actively debated with some suggesting that FND-seiz should be considered a distinct entity from FND-movt{94}.

Etiological heterogeneity likely also contributes to heterogeneous findings described across autonomic and endocrine data. For instance, stressful life events and early life maltreatment are well-known predisposing vulnerabilities for FND{95}, with studies identifying that hypercortisolism was associated with trauma burden{62, 68}. However, antecedent adverse life experiences were not systematically accounted for across studies in this review, and differences in trauma burden across FND samples could be a major factor contributing to inconsistently identified results. Such themes raise the question of a possible trauma-subtype of FND{96}.

Regarding methodological challenges, the multiplicity of additional physical symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue) and commonly co-occurring neurological (e.g., traumatic brain injury) and psychiatric conditions (major depression, PTSD) that are themselves associated with altered autonomic, endocrine and inflammation profiles are additional important considerations. For example, pain is a highly prevalent symptom in many patients with FND that is associated with a poor prognosis{4}; stratifying FND patients by the presence or absence of prominent pain would likely help disentangle the heterogeneity present in the literature{97}. Notably, pain is associated with heightened autonomic activity, increased inflammation, and endocrine alterations in other neuropsychiatric conditions{98}. Similarly, PTSD is associated with hypercortisolism and elevated inflammation markers{99}. To adequately account for these factors and other confounds (e.g., medication effects, and time and type of cortisol sample drawn etc.), larger samples are undoubtedly needed. Larger patient samples would also assist in comprehensively investigating the complex interplay between functional neurological symptoms and behavioral, psychological, autonomic, endocrine, inflammation, neuroimaging, and epigenetic/genetic data{100}. Furthermore, replication of the same methods across studies need to be encouraged to allow for straight forward comparisons of results. More research is also needed to determine to what extent FND is mechanistically (and etiologically) similar or distinct across phenotypes. Lastly, given that several negative physiology studies found differences in self-report measures, as well as in cognitive and behavioral task performances, it is worth considering the overall utility (and framing) of biomarker research in this field.

In conclusion, the study of autonomic, endocrine and inflammatory measurements in patients with FND remains a promising, yet complex, area of research. Given that FND is likely mechanistically and etiologically heterogenous, the study of biologically-informed subtypes and composite biomarkers may be particularly fruitful future directions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Study quality assessment according to the National Institute of Health Study Quality Assessment Tools. NR, not reported; NA, not applicable.

Supplementary Figure 1. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of studies comparing baseline heart rate between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. The red box indicates the cohort that is driving the overall effect. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 2. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of peri-ictal heart rate between functional neurological disorder and epilepsy patients. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 3. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline heart rate variability between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 4. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline cortisol between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 5. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline cortisol between functional neurological disorder and epilepsy patients. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 6. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of within-group comparison of functional neurological disorder peri-ictal heart rate. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 7. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of skin conductance levels while performing a task in functional neurological disorder and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 8. Forest plot of the within-group comparison of the peri-ictal heart rate mean difference in functional neurological disorder. CI, Confidence Interval; Mean Diff, Mean Difference. Θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Supplementary Figure 9. Forest plot of the standardized mean difference of skin conductance levels at task in functional neurological disorder and healthy controls. FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; HC, Healthy Controls; CI, Confidence Interval; St. Mean Diff, Standardized Mean Difference. Θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Acknowledgements:

This study was also submitted for abstract presentation at the 2021 American Neuropsychiatric Association conference.

Funding:

D.L.P. was funded by the NIMH (K23MH111983) and the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundation. S.P. is funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (UK).

Footnotes

Disclosures / Conflicts of Interest:

D.L.P. has received honoraria for continuing medical education lectures in functional neurological disorder and is on the editorial board of Epilepsy & Behavior. All other authors do not report any disclosures / conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perez DL, Aybek S, Popkirov S, Kozlowska K, Stephen CD, Anderson J, et al. A Review and Expert Opinion on the Neuropsychiatric Assessment of Motor Functional Neurological Disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(1):14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone J, Carson A, Duncan R, Roberts R, Warlow C, Hibberd C, et al. Who is referred to neurology clinics?--the diagnoses made in 3781 new patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(9):747–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephen CD, Fung V, Lungu CI, Espay AJ. Assessment of Emergency Department and Inpatient Use and Costs in Adult and Pediatric Functional Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelauff JM, Carson A, Ludwig L, Tijssen MAJ, Stone J. The prognosis of functional limb weakness: a 14-year case-control study. Brain. 2019;142(7):2137–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baslet G, Bajestan SN, Aybek S, Modirrousta M, JP DCP, Cavanna A, et al. Evidence-Based Practice for the Clinical Assessment of Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: A Report From the American Neuropsychiatric Association Committee on Research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;33(1):27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bègue I, Adams C, Stone J, Perez DL. Structural alterations in functional neurological disorder and related conditions: a software and hardware problem? NeuroImage Clinical. 2019;22:101798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Hallett M, Jankovic J. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of functional (psychogenic) movement disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;127:32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aybek S, Nicholson TR, O’Daly O, Zelaya F, Kanaan RA, David AS. Emotion-motion interactions in conversion disorder: an FMRI study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, Ameli R, Roelofs K, LaFrance WC Jr., et al. Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1526–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aybek S, Nicholson TR, Zelaya F, O’Daly OG, Craig TJ, David AS, et al. Neural correlates of recall of life events in conversion disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(1):52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez I, Ortiz-Teran L, Williams B, Jalilianhasanpour R, Ospina JP, Dickerson BC, et al. Corticolimbic fast-tracking: enhanced multimodal integration in functional neurological disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(8):929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurer CW, LaFaver K, Ameli R, Epstein SA, Hallett M, Horovitz SG. Impaired self-agency in functional movement disorders: A resting-state fMRI study. Neurology. 2016;87(6):564–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, Bruno M, Ekanayake V, Hallett M. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arthuis M, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Bartolomei F, McGonigal A, Guedj E. Resting cortical PET metabolic changes in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(10):1106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, Liu K, Ma X, Li Z, Duan X, An D, et al. Altered Functional Connectivity Patterns of the Insular Subregions in Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures. Brain Topogr. 2015;28(4):636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szaflarski JP, Allendorfer JB, Nenert R, LaFrance WC Jr., Barkan HI, DeWolfe J, et al. Facial emotion processing in patients with seizure disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;79:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diez I, Williams B, Kubicki MR, Makris N, Perez DL. Reduced limbic microstructural integrity in functional neurological disorder. Psychol Med. 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jungilligens J, Wellmer J, Kowoll A, Schlegel U, Axmacher N, Popkirov S. Microstructural integrity of affective neurocircuitry in patients with dissociative seizures is associated with emotional task performance, illness severity and trauma history. Seizure. 2020;84:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison NA, Brydon L, Walker C, Gray MA, Steptoe A, Critchley HD. Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison NA, Brydon L, Walker C, Gray MA, Steptoe A, Dolan RJ, et al. Neural origins of human sickness in interoceptive responses to inflammation. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):415–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomsen BLC, Teodoro T, Edwards MJ. Biomarkers in functional movement disorders: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(12):1261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NIH: National Heart L, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [10/29/2020].

- 23.De Oliveira GR, Gondim FDAA, Hogan ER, Rola FH. Movement-induced heart rate changes in epileptic and non-epileptic seizures. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67(3 B):789–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponnusamy A, Marques JLB, Reuber M. Comparison of heart rate variability parameters during complex partial seizures and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2012;53(8):1314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang SW, Liu YX. Changes of serum adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol levels during sleep seizures. Neurosci Bull 2008;24(2):84–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlowska K, Palmer DM, Brown KJ, McLean L, Scher S, Gevirtz R, et al. Reduction of autonomic regulation in children and adolescents with conversion disorders. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(4):356–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlowska K, Rampersad R, Cruz C, Shah U, Chudleigh C, Soe S, et al. The respiratory control of carbon dioxide in children and adolescents referred for treatment of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(10):1207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozlowska K, Spooner CJ, Palmer DM, Harris A, Korgaonkar MS, Scher S, et al. “Motoring in idle”: The default mode and somatomotor networks are overactive in children and adolescents with functional neurological symptoms. NeuroImage Clinical. 2018;18:730–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurer CW, Liu VD, LaFaver K, Ameli R, Wu T, Toledo R, et al. Impaired resting vagal tone in patients with functional movement disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;30:18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demartini B, Goeta D, Barbieri V, Ricciardi L, Canevini MP, Turner K, et al. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures and functional motor symptoms: A common phenomenology? J Neurol Sci. 2016;368:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawchuk T, Buchhalter J, Senft B. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures in children - psychophysiology & dissociative characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice D, Greenfield NS. Psychophysiological correlates of la belle indifference. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1969;20(2):239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyer GL, Harvey RA, Islam MP. Signs of autonomic arousal precede tilt-induced psychogenic nonsyncopal collapse among youth. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;86:166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakvis P, Roelofs K, Kuyk J, Edelbroek PM, Swinkels WAM, Spinhoven P. Trauma, stress, and preconscious threat processing in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1001–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allendorfer JB, Nenert R, Hernando KA, DeWolfe JL, Pati S, Thomas AE, et al. FMRI response to acute psychological stress differentiates patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures from healthy controls – A biochemical and neuroimaging biomarker study. NeuroImage Clinical. 2019;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herrero H, Tarrada A, Haffen E, Mignot T, Sense C, Schwan R, et al. Skin conductance response and emotional response in women with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Seizure. 2020;81:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opherk C, Hirsch LJ. Ictal heart rate differentiates epileptic from non-epileptic seizures. Neurology. 2002;58(4):636–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinsberger C, Perez DL, Murphy MM, Dworetzky BA. Pre- and postictal, not ictal, heart rate distinguishes complex partial and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23(1):68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Oliveira GR, Gondim FDAA, Hogan RE, Rola FH. Heart rate analysis differentiates dialeptic complex partial temporal lobe seizures from auras and non-epileptic seizures. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65(3 A):565–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Kruijs SJM, Vonck KEJ, Langereis GR, Feijs LMG, Bodde NMG, Lazeron RHC, et al. Autonomic nervous system functioning associated with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Analysis of heart rate variability Epilepsy Behav. 2016;54:14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radmanesh M, Jalili M, Kozlowska K. Activation of Functional Brain Networks in Children With Psychogenic Non-epileptic Seizures. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claffey P, Pérez-Denia L, Rivasi G, Finucane C, Kenny RA. Near-infrared spectroscopy in evaluating psychogenic pseudosyncope - A novel diagnostic approach. QJM. 2020;113(4):239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponnusamy A, Marques JL, Reuber M. Heart rate variability measures as biomarkers in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: potential and limitations. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(4):685–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müngen B, Berilgen MS, Arikanoğlu A. Autonomic nervous system functions in interictal and postictal periods of nonepileptic psychogenic seizures and its comparison with epileptic seizures. Seizure. 2010;19(5):269–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romigi A, Ricciardo Rizzo G, Izzi F, Guerrisi M, Caccamo M, Testa F, et al. Heart Rate Variability Parameters During Psychogenic Non-epileptic Seizures: Comparison Between Patients With Pure PNES and Comorbid Epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2020;11:713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts NA, Burleson MH, Torres DL, Parkhurst DK, Garrett R, Mitchell LB, et al. Emotional Reactivity as a Vulnerability for Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures? Responses While Reliving Specific Emotions. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;32(1):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts NA, Burleson MH, Weber DJ, Larson A, Sergeant K, Devine MJ, et al. Emotion in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Responses to affective pictures. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24(1):107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novakova B, Harris PR, Reuber M. Diurnal patterns and relationships between physiological and self-reported stress in patients with epilepsy and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;70:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeppesen J, Beniczky S, Johansen P, Sidenius P, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A. Comparing maximum autonomic activity of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures and epileptic seizures using heart rate variability. Seizure. 2016;37:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanyal S, Chattopadhyay PK, Biswas D. Electro-dermal arousal and self-appraisal in patients with somatization disorder. Indian J Clin Psychol. 1998;25(2):144–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinsberger C, Sarkis R, Papadelis C, Doshi C, Perez DL, Baslet G, et al. Autonomic changes in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: toward a potential diagnostic biomarker? Clin EEG Neurosci. 2015;46(1):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higgitt A, Fonagy P, Toone B, Shine P. The prolonged benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: Anxiety or hysteria? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82(2):165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pick S, Mellers JD, Goldstein LH. Explicit Facial Emotion Processing in Patients With Dissociative Seizures. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(7):874–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pick S, Mellers JDC, Goldstein LH. Autonomic and subjective responsivity to emotional images in people with dissociative seizures. J Neuropsychol 2018;12(2):341–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pick S, Rojas-Aguiluz M, Butler M, Mulrenan H, Nicholson TR, Goldstein LH. Dissociation and interoception in functional neurological disorder. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2020:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lader M, Sartorius N. Anxiety in patients with hysterical conversion symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968;31(5):490–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kotwas I, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Khalfa S, McGonigal A, Bastien-Toniazzo M, Bartolomei F. Subjective and physiological response to emotions in temporal lobe epilepsy and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Redlich FC. Organic and hysterical anesthesia; a method of differential diagnosis with the aid of the galvanic skin response. Am J Psychiatry. 1945;102:318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dreissen YEM, Boeree T, Koelman JHTM, Tijssen MAJ. Startle responses in functional jerky movement disorders are increased but have a normal pattern. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;40:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rabavilas AD. Clinical significance of the electrodermal habituation rate in anxiety disorders. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22(2):68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seignourel PJ, Miller K, Kellison I, Rodriguez R, Fernandez HH, Bauer RM, et al. Abnormal affective startle modulation in individuals with psychogenic [corrected] movement disorder. Mov Disord. 2007;22(9):1265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Apazoglou K, Mazzola V, Wegrzyk J, Frasca Polara G, Aybek S. Biological and perceived stress in motor functional neurological disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;85:142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bakvis P, Spinhoven P, Zitman FG, Roelofs K. Automatic avoidance tendencies in patients with Psychogenic Non Epileptic Seizures. Seizure. 2011;20(8):628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bakvis P, Spinhoven P, Roelofs K. Basal cortisol is positively correlated to threat vigilance in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;16(3):558–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maurer CW, LaFaver K, Ameli R, Toledo R, Hallett M. A biological measure of stress levels in patients with functional movement disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(9):1072–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miani A, Pedersen AS, Rask CU, Uber-Zak L, Zak PJ, Winterdahl M. Predicting psychogenic non-epileptic seizures from serum levels of neuropeptide y and adrenocorticotropic hormone. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2019;31(3):167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winterdahl M, Miani A, Vercoe MJH, Ciovica A, Uber-Zak L, Rask CU, et al. Vulnerability to psychogenic non-epileptic seizures is linked to low neuropeptide Y levels. Stress. 2017;20(6):589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bakvis P, Spinhoven P, Giltay EJ, Kuyk J, Edelbroek PM, Zitman FG, et al. Basal hypercortisolism and trauma in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tunca Z, Fidaner H, Cimilli C, Kaya N, Biber B, Yeşil S, et al. Is conversion disorder biologically related with depression?: A DST study. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(3):216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallagher BB. Endocrine Abnormalities in Human Temporal Lobel Epilepsy. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:93–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gallagher BB, Murvin A, Flanigin HF, King DW, Luney D. Pituitary and Adrenal Function in Epileptic Patients. Epilepsia. 1984;25(6):683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zito GA, Apazoglou K, Paraschiv-Ionescu A, Aminian K, Aybek S. Abnormal postural behavior in patients with functional movement disorders during exposure to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;101:232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mehta SR, Dham SK, Lazar AI, Narayanswamy AS, Prasad GS. Prolactin and cortisol levels in seizure disorders. J Assoc Physicians India. 1994;42(9):709–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pankova OF, Keshokov AA. Autonomic-humoral regulation in neuroses and neurotic development of the personality. Soviet Neurology & Psychiatry. 1983;16(3):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ceylan M, Yalcin A, Bayraktutan OF, Laloglu E. Serum NT-pro CNP levels in epileptic seizure, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure, and healthy subjects. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(12):2135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aydin S, Dag E, Ozkan Y, Arslan O, Koc G, Bek S, et al. Time-dependent changes in the serum levels of prolactin, nesfatin-1 and ghrelin as a marker of epileptic attacks young male patients. Peptides. 2011;32(6):1276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deveci A, Aydemir O, Taskin O, Taneli F, Esen-Danaci A. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in conversion disorder: Comparative study with depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(5):571–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lafrance WC Jr, Leaver K, Stopa EG, Papandonatos GD, Blum AS. Decreased serum BDNF levels in patients with epileptic and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2010;75(14):1285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kozlowska K, Chung J, Cruickshank B, McLean L, Scher S, Dale RC, et al. Blood CRP levels are elevated in children and adolescents with functional neurological symptom disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khanam M, Azad MAK, Ullah MA, Ahsan MS, Bari W, Islam SN, et al. Serum immunoglobulin profiles of conversion disorder patients. Germ J Psychiatry. 2008;11(4):141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Büyükaslan H, Asoğlu M. Evaluation of mean platelet volume, red cell distributed width and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in conversion disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2879–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tiyekli U, Calıyurt O, Tiyekli ND. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with conversion disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2013;25(3):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shah AK, Shein N, Fuerst D, Yangala R, Shah J, Watson C. Peripheral WBC Count and Serum Prolactin Level in Varios Seizure Types and Nonepileptic Events. Epilepsia. 2001;42(11):1472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Holtkamp M, Othman J, Buchheim K, Meoerjord H. Diagnnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic status epilepticus in the emergency settings. Neurology. 2006;66:1727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wyllie E, Lueders H, Pippenger C, F. V. Postictal Serum Creatine Kinase in the Diagnosis of Seizure Disorders. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kugu N, Bolayir E, Akyuz A, Ersan E. Muscle enzymes, blood gases and quantitative EEG in differential diagnosis of generalized tonic-clonic seizures and conversive non-epileptic seizures. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2004;11(3):133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Matz O, Zdebik C, Zechbauer S, Bündgens L, Litmathe J, Willmes K, et al. Lactate as a diagnostic marker in transient loss of consciousness. Seizure. 2016;40:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olaciregui Dague K, Surges R, Litmathe J, Villa L, Brokmann J, Schulz JB, et al. The discriminative value of blood gas analysis parameters in the differential diagnosis of transient disorders of consciousness. J Neurol. 2018;265(9):2106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kozlowska K A stress-system model for functional neurological symptoms. J Neurol Sci. 2017;383:151–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keynejad RC, Frodl T, Kanaan R, Pariante C, Reuber M, Nicholson TR. Stress and functional neurological disorders: Mechanistic insights. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2019;90(7):813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim J, Yoon S, Lee S, Hong H, Ha E, Joo Y, et al. A double-hit of stress and low-grade inflammation on functional brain network mediates posttraumatic stress symptoms. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Allendorfer JB, Nenert R, Hernando KA, DeWolfe JL, Pati S, Thomas AE, et al. FMRI response to acute psychological stress differentiates patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures from healthy controls - A biochemical and neuroimaging biomarker study. NeuroImage Clinical. 2019;24:101967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Espay AJ, Maloney T, Vannest J, Norris MM, Eliassen JC, Neefus E, et al. Impaired emotion processing in functional (psychogenic) tremor: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. NeuroImage Clinical. 2018;17:179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kanaan RAA, Duncan R, Goldstein LH, Jankovic J, Cavanna AE. Are psychogenic non-epileptic seizures just another symptom of conversion disorder? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(5):425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, Aybek S, David AS, Tuck S, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(4):307–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Diez I, Larson AG, Nakhate V, Dunn EC, Fricchione GL, Nicholson TR, et al. Early-life trauma endophenotypes and brain circuit-gene expression relationships in functional neurological (conversion) disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maggio J, Alluri PR, Paredes-Echeverri S, Larson AG, Sojka P, Price BH, et al. Briquet syndrome revisited: implications for functional neurological disorder. Brain Communications. 2020;2(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ying-Chih C, Yu-Chen H, Wei-Lieh H. Heart rate variability in patients with somatic symptom disorders and functional somatic syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:336–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, et al. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1002–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spagnolo PA, Norato G, Maurer CW, Goldman D, Hodgkinson C, Horovitz S, et al. Effects of TPH2 gene variation and childhood trauma on the clinical and circuit-level phenotype of functional movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(8):814–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Study quality assessment according to the National Institute of Health Study Quality Assessment Tools. NR, not reported; NA, not applicable.

Supplementary Figure 1. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of studies comparing baseline heart rate between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. The red box indicates the cohort that is driving the overall effect. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 2. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of peri-ictal heart rate between functional neurological disorder and epilepsy patients. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 3. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline heart rate variability between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 4. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline cortisol between functional neurological disorder patients and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 5. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of baseline cortisol between functional neurological disorder and epilepsy patients. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 6. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of within-group comparison of functional neurological disorder peri-ictal heart rate. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 7. Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis of skin conductance levels while performing a task in functional neurological disorder and healthy controls. CI, Confidence Interval.

Supplementary Figure 8. Forest plot of the within-group comparison of the peri-ictal heart rate mean difference in functional neurological disorder. CI, Confidence Interval; Mean Diff, Mean Difference. Θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.

Supplementary Figure 9. Forest plot of the standardized mean difference of skin conductance levels at task in functional neurological disorder and healthy controls. FND, Functional Neurological Disorder; HC, Healthy Controls; CI, Confidence Interval; St. Mean Diff, Standardized Mean Difference. Θ, effect size; Q, homogeneity; H2, heterogeneity; I2, variation; τ2, variability; REML, restricted maximum likelihood model.