Abstract

Although there is no age criterion for rivaroxaban dose reduction, elderly patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) are often prescribed an off-label reduced dose. We aimed to evaluate whether age is a necessary criterion for rivaroxaban dose reduction in Korean patients with AF. Among 2208 patients who prescribed warfarin or rivaroxaban, 552 patients over 75 years without renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance >50 mL/min) were compared based on propensity score matching. The rivaroxaban group was further divided into a 20 mg (R20; on-label) and a 15 mg (R15; off-label). Primary net clinical benefit (NCB) was defined as the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, and all-cause mortality. Secondary NCB was defined as the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding. Patients were followed for 1 year, or until the first outcome occurrence. Both rivaroxaban groups had comparable efficacy compared with warfarin. However, both R20 (0.9% vs 7.4%, p = .014) and R15 (2.3% vs 7.4%, p = .018) had a significant reduction in major bleeding. There were no differences in efficacy or safety outcomes between R20 and R15. R20 had significantly reduced primary (hazard ratio [HR] 0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.12–0.93) and secondary (HR 0.31, 95% CI: 0.10–0.93) NCBs compared with warfarin. However, primary and secondary NCBs were not reduced in R15. In real-world practice with elderly patients with AF, off-label rivaroxaban dose reduction to 15 mg conferred no benefits. Therefore, guideline-adherent rivaroxaban 20 mg is favorable in elderly Korean patients with AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, rivaroxaban, age groups, reference standards

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia. The prevalence of AF in Korea increased consistently, by 1.7-fold, from 2008 (0.4%) to 2015 (0.7%) and is increasing rapidly as the Korean population ages. 1 AF is also a major cause of stroke, disability, and death among the elderly. Given that AF confers a substantial risk of mortality and morbidity from stroke, the use of oral anticoagulants (OACs) for stroke prevention is very important. Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) have been the mainstay of stroke prevention treatment in AF for more than half a century. 2 However, the narrow therapeutic index and multiple drug–drug and drug–food interactions of warfarin complicate its use. In particular, Asians have a lower prevalence of AF but carry a specific, increased risk of ischemic stroke, are more sensitive to warfarin, and are more prone to suffer from warfarin-related bleeding. 3 It is well established that effective stroke prevention requires OACs, but the problem is compounded by the substantial numbers of patients in Asia who are not treated with warfarin because of the increased risk of side effects or for some other reason. 4 Therefore, non-vitamin K oral antagonists (NOACs) have been developed; these dose dependently inhibit thrombin or activated factor X (or factor Xa), are effective against stroke or systemic embolic events (with lower rates of ICH and mortality), and have similar effects on major bleeding compared with warfarin. 5 Rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor, is associated with a comparable risk of ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolism, and a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), compared with warfarin. 6 Also, rivaroxaban administered to a subgroup of Asian patients showed similar efficacy and safety compared with warfarin. 7

The current guidelines for the optimal dose of rivaroxaban are based on global trial results. 8 However, few studies have investigated the optimal rivaroxaban dosage for Asian patients, because of the limited No. of Asian patients sampled in current studies. 7 Because of concerns over bleeding with rivaroxaban in Asian patients, off-label rivaroxaban dose reduction to 15 mg is common in Asian clinical practice. 9 Furthermore, the Korean Heart rhythm society has recommended that rivaroxaban 15 mg be used for patients who are older than 75 to 80 years or who have a creatinine clearance of 15 to 50 mL. 10 Nevertheless, there is a controversy over the optimal rivaroxaban dose for elderly patients without renal dysfunction. Thus, this study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin and to verify the optimal dose of rivaroxaban for elderly Korean AF patients without renal dysfunction.

Method

Study Population

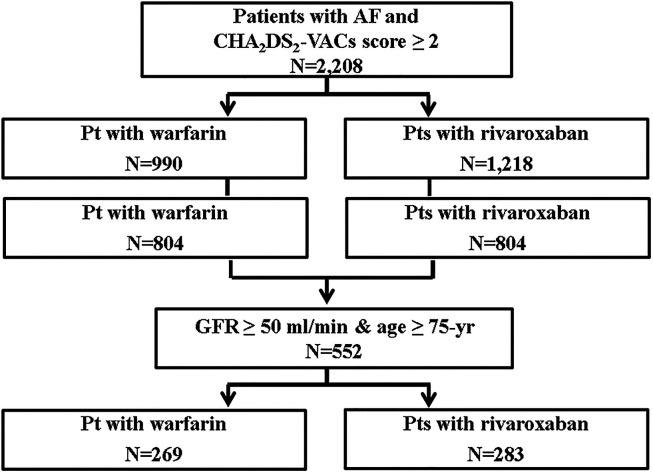

Patient enrollment and flowchart are shown in Figure 1. A total 2,208 patients with AF who were taking warfarin or rivaroxaban from 2012 to 2017 in the Department of Neurology and Cardiology, Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, South Korea were initially included. Other inclusion criteria were taking OACs such as warfarin or rivaroxaban and having a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2. The exclusion criteria were valvular AF (eg, rheumatic mitral stenosis, prosthetic mitral valve replacement, or repair), any OAC class change (from warfarin to NOACs or NOACs to warfarin), a rivaroxaban dose change during the 1 year of follow-up, any bleeding diathesis resulting cessation of OAC, end-stage renal disease (creatinine clearance < 15 mL/min or hemodialysis), and severe hepatic dysfunction. Follow-up for all selected patients was 1 year, or until the first occurrence of any study outcome, from the date of enrollment. Propensity score matching was used to balance covariates. After propensity matching, 552 patients older than 75 years without renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance > 50 mL/min) were included. Warfarin was used by 269 patients (48.0%), and rivaroxaban was used by 283 patients (52.0%). Patients treated with rivaroxaban were divided into either the 20 mg group (R20; on-label, n = 106, 37.4%) or 15 mg group (R15; off-label, n = 177, 62.6%).

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment and flowchart.

Definition

New-onset stroke was defined as the sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit in a location consistent with the territory of a major cerebral artery and categorized as an ischemic, hemorrhagic, or transient ischemic attack (TIA). TIA was defined as the sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit without evidence of a newly developed cerebral lesion. Systemic embolism was defined as an acute vascular occlusion of an extremity or organ, documented via imaging or surgery. Major bleeding was defined according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) criteria, as clinically overt bleeding accompanied by a 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin level or transfusion of at least two units of packed red cells, occurring at a critical site, or resulting in death. Minor bleeding was defined as clinically overt bleeding that did not meet major bleeding criteria. Mucosal bleeding was defined as any bleeding from mucosa including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, genitourinary tract, or respiratory mucosa.

Efficacy outcome was defined as thromboembolism composed of new-onset stroke, or systemic embolism. Safety outcome was major bleeding. Primary net clinical benefits (NCBs) were defined as the composite of new-onset stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, and all-cause death. NOACs are known to reduce the risk of both stroke and death; therefore, we included all-cause death both as a single end point and as a combined end point with stroke, consistent with our previously published study. 11 Secondary NCBs were defined as the composite of new-onset stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, between-group differences were evaluated using unpaired t-tests or Mann–Whitney rank-sum tests. For discrete variables, differences were expressed as counts and percentages and were analyzed using a chi-square test or Fisher's exact probability test, as appropriate. To minimize the effects of selection bias in comparisons between warfarin and rivaroxaban groups, equal numbers of patients with similar baseline characteristics taking rivaroxaban or warfarin were paired (1:1) using propensity scores; equal numbers of patients with similar baseline characteristics taking warfarin or rivaroxaban were then compared (1:1). Propensity scores were estimated based on the likelihood of selection of OACs, using a multiple logistic regression model with patient age, sex, hypertension status, diabetes mellitus status, previous history of MI, previous history of heart failure, and previous history of stroke or TIA. Matching was performed using a greedy matching protocol (1:1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement). We subsequently constructed Kaplan–Meier curves for clinical outcomes, and differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze hazard ratios (HRs) as estimates of clinical outcomes. HRs was adjusted for propensity scores and important risk covariates that were statistically significant (P < .1) in univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS-PC Inc.) and R version 2.14.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All analyses were two-tailed, with clinical significance defined as P < .05.

Results

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 shows the enrolled patients’ demographic characteristics. Before propensity score matching, the rivaroxaban group was older, and had a higher prevalence of females, smoking, hypertension, heart failure, and previous history of myocardial infarction, stroke, or TIA. The CHA2DS2-VASc score was higher in patients treated with rivaroxaban (3.5 ± 1.7 vs 3.3 ± 1.9, P = .019). After propensity score matching, there were no differences in gender, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, previous history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, TIA, or stroke or CHA2DS2-VASc score in patients older than 75 years with AF and without renal dysfunction.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics.

| Before PS matching | After PS matching | After PS matching (≥75-year old without renal dysfunction) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin (n = 990) | Rivaroxaban (n = 1218) |

P-value | Warfarin (n = 804) | Rivaroxaban (n = 804) |

P-value | Warfarin (n = 269) | Rivaroxaban (n = 283) |

P-value | |

| Female gender, n (%) | 338 (34.1) | 546 (44.8) | <.001 | 318(39.6) | 295(36.7) | .238 | 130 (49.4) | 130 (45.9) | .410 |

| Age, years | 69.3 ± 10.8 | 72.5 ± 9.8 | .004 | 70.4 ± 10.2 | 71.4 ± 10.5 | .086 | 79.8 ± 4.1 | 80.4 ± 4.0 | .435 |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 517 (52.2) | 767 (63.0) | <.001 | 440 (54.7) | 430 (53.5) | .617 | 161 (59.9) | 171 (60.4) | .891 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 213 (21.5) | 292 (24.0) | .185 | 179 (22.3) | 194 (24.1) | .375 | 57 (21.2) | 63 (22.3) | .760 |

| Smoking | 265 (26.8) | 220 (18.1) | <.001 | 189 (23.5) | 164 (20.4) | .132 | 50 (18.6) | 49 (17.3) | .697 |

| Previous history of MI | 57 (5.8) | 132 (10.8) | <.001 | 55 (6.8) | 55 (6.8) | 1.000 | 26 (9.7) | 21 (7.4) | .345 |

| Heart failure | 91 (9.2) | 120 (9.4) | <.001 | 41 (5.1) | 46 (5.7) | .582 | 9 (3.3) | 13 (4.6) | .454 |

| TIA, stroke | 378 (38.2) | 241 (19.8) | <.001 | 233 (29.2) | 235 (29.2) | .913 | 97 (36.1) | 91 (32.2) | .333 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.34 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | .019 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | .183 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | .168 |

Abbreviations: MI: myocardial infarction; PS: propensity score; ; TIA: transient ischemic attack

Clinical Outcomes in Warfarin Versus Rivaroxaban Groups

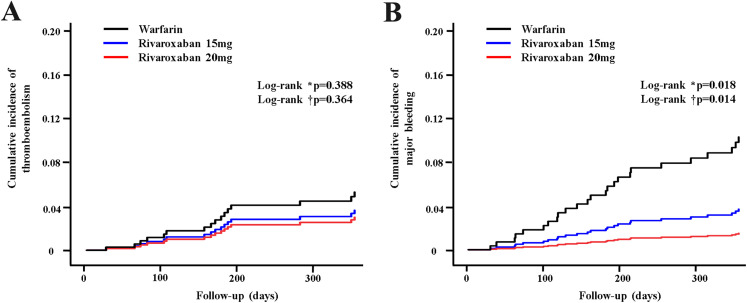

There were no significant differences in the rates of stroke or systemic embolism between R20 and warfarin, between R15 and warfarin, or between R20 and R15 during the 12-month follow-up (Table 2, Figure 2A, 2B). Rivaroxaban was associated with a similar risk of ischemic stroke compared with warfarin (1.8% vs 2.2%, P = .697). The risk of major bleeding (1.8% vs 7.1%, P = .002), GI bleeding (1.1% vs 3.7%, P = .04), mucosal bleeding (1.4% vs 5.2%, P = .012), or intracranial bleeding (0% vs 2.2%, P = .04) was significantly lower in rivaroxaban compared with warfarin (Table 2). All-cause mortality was lower in rivaroxaban compared with warfarin (1.4% vs 5.6%, P= .007).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes in Warfarin Versus Rivaroxaban.

| Warfarin (n = 269) | Rivaroxaban (n = 283) |

P-value | Warfarin (n = 269) | Rivaroxaban

15 mg (n = 177) |

P-value | Warfarin (n = 269) | Rivaroxaban

20 mg (n = 106) |

P-value | Rivaroxaban

15 mg (n = 177) |

Rivaroxaban 20 mg (n = 106) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thromboembolism | 11 (4.1) | 7 (2.5) | .285 | 11 (4.1) | 5 (2.8) | .482 | 11 (4.1) | 2 (1.9) | .366 | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1.9) | .715 |

| Systemic embolism | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | .971 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| New-onset stroke | 10 (3.9) | 6 (2.1) | .264 | 10 (3.9) | 4 (2.3) | .580 | 10 (3.7) | 2 (1.9) | .5222 | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.9) | .833 |

| Ischemic stroke | 6 (2.2) | 5 (1.8) | .697 | 6 (2.2) | 4 (2.3) | .622 | 6 (2.2) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 | 4 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | .654 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | .160 | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) | .155 | 4(1.5) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | .375 |

| TIA | 0 | 0 | .000 | 0 | 0 | .000 | 0 | 0 | .000 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Major bleeding | 20 (7.4) | 5(1.8) | .002 | 20 (7.4) | 4(2.3) | .018 | 20(7.4) | 1 (0.9) | .014 | 4(2.3) | 1 (0.9) | .654 |

| GI bleeding | 11 (4.1) | 3 (1.1) | .040 | 11 (4.1) | 2 (1.1) | .069 | 11 (4.1) | 1 (0.9) | .191 | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Mucosal bleeding | 15 (5.6) | 4 (1.4) | .012 | 15 (5.6) | 3 (1.7) | .049 | 15 (5.6) | 1 (0.9) | .048 | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) | .040 | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) | .155 | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) | .581 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Death | 15 (5.6) | 4 (1.4) | .007 | 15 (5.6) | 3 (1.7) | .049 | 15 (5.6) | 1 (0.9) | .048 | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | .604 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | .959 | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | .651 | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | .530 |

| Noncardiac death | 13 (4.8) | 2 (0.7) | .003 | 13 (4.8) | 1 (0.6) | .011 | 13 (4.8) | 1 (0.9) | .125 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimation for primary outcomes between patients with warfarin and rivaroxaban. (A) Cumulative incidence of thromboembolism. (B) Cumulative incidence of major bleeding.

Abbreviations: W, Warfarin; R15: Rivaroxaban 15 mg; R20: Rivaroxaban 20 mg.

Clinical Outcomes Between Rivaroxaban 20 mg and 15 mg Groups

Both rivaroxaban groups had comparable efficacy compared with warfarin. Furthermore, both R20 (0.9% vs 7.4%, P = .014) and R15 (2.3% vs 7.4%, P = .018) had significantly reduced major bleeding (Table 2). There were no efficacy or safety outcome differences between R20 and R15.

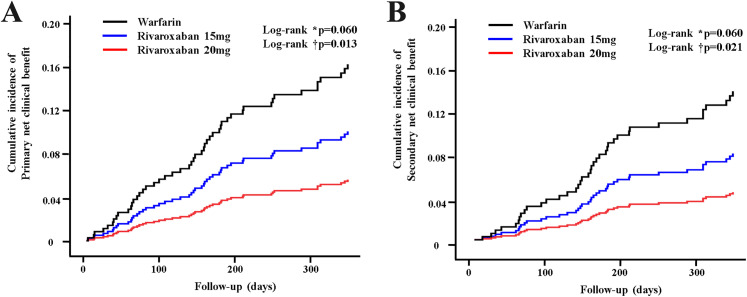

Composite net Clinical Benefits

Rivaroxaban showed better outcomes compared with warfarin for all composite end points. Rivaroxaban 20 mg significantly lowered the risk of primary (HR 0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.12–0.93, P= .037), and secondary (HR 0.31, 95% CI: 0.10−0.93, P= .043) NCBs compared with warfarin (Figure 3A, 3B). There were no significant differences in the risk of primary or secondary NCBs between R15 and warfarin or between R20 and R15 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Predictors of Net Clinical Benefit (NCB).

| Clinical outcome | Warfarin (n = 269) |

R15 (n = 177) |

R20 (n = 106) |

Warfarin versus R15 | P-value | Warfarin versus R 20 | P-value | R 20 versus R 15 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Primary NCB | 33 (12.3) | 12 (6.8) | 4 (3.8) | 0.60 (0.31−1.16) | 0.127 | 0.33 (0.12−0.93) | .037 | 1.83 (0.591−5.69) | .294 |

| Secondary NCB | 27 (10.0) | 9 (5.1) | 3 (2.8) | 0.56 (0.26−1.20) | .134 | 0.31 (0.10−0.93) | .043 | 1.86 (0.50−6.87) | .352 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; R15: Rivaroxaban 15 mg, R20: Rivaroxaban 20 mg; Primary NCB: primary net clinical benefit (the composite of stroke/systemic embolism/major bleeding/death); Secondary NCB: secondary net clinical benefit (the composite of stroke/systemic embolism/major bleeding).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimation for clinical benefit between patients with warfarin and rivaroxaban. (A) Cumulative incidence of primary net clinical benefit (NCB) (stroke/systemic embolism/major bleeding/death). (B) Cumulative incidence of secondary NCB (stroke/systemic embolism/major bleeding).

Abbreviations: W: Warfarin; R15: Rivaroxaban 15 mg; R20: Rivaroxaban 20 mg.

Discussion

This population-based observational study focused specifically on Asian patients to assess the effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban in the elderly without renal dysfunction. We found that rivaroxaban had greater safety compared with warfarin in elderly patients with AF. The risks of bleeding and all-cause mortality were significantly lower in rivaroxaban compared with warfarin. Specifically, compared with warfarin, on-label rivaroxaban 20 mg significantly improved NCBs in elderly patients without renal dysfunction, whereas off-label rivaroxaban 15 mg did not have this effect. Our results suggest that elderly patients who have AF without renal dysfunction do not need dose-reduced rivaroxaban.

AF is common in elderly patients, who also have higher rates of stroke and major bleeding. Given that AF confers substantial risks of mortality and morbidity from stroke, anticoagulant therapy for stroke prevention is paramount. Bleeding risk during anticoagulant therapy is also amplified with advanced age and thus requires frequent anticoagulation monitoring. Consequently, elderly patients are often not prescribed anticoagulants or are unable to sustain warfarin therapy over time, leaving many at higher risk of stroke. 12 Rivaroxaban, the first oral factor Xa inhibitor approved as an alternative to warfarin for several thromboembolic indications, is noninferior to adjusted dose warfarin. 6 In particular, the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban relative to warfarin did not differ with age, supporting rivaroxaban as an alternative for the elderly. 13 Elderly patients in the ROCKET AF study receiving rivaroxaban had equal benefits, including lower risk of intracranial bleeding, compared with those receiving warfarin. Although less clinically significant compared with that phase three study, our real-world data also show that rivaroxaban is safe for elderly Asian patients with AF, who had similar rates of ischemic stroke but lower rates of major bleeding, including intracranial and GI bleeding, compared with warfarin.

The optimal dosage of rivaroxaban, including maximal efficacy and safety, was determined from global trials. 6 Unlike other factor Xa inhibitors (eg, apixaban, edoxaban), old age is not an indication for rivaroxaban dose reduction. 8 Rivaroxaban 15 mg prescribed to patients whose creatinine clearance values were 30 and 50 mL/min showed positive effects. However, most NOAC trials have only included approximately 10% Asian participants 7 Therefore, application of the same NOAC dosage criteria to Asians is debated, because of ethnic and lifestyle differences, and thus requires additional clinical evidence. Compared with Western patients, Asian patients are more prone to developing major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhaging, on the same dose of warfarin; this has been explained as being due to ethnic differences. 3 These characteristics were reflected in Japanese guidelines for anticoagulation therapy in patients with AF, suggesting that the optimal anticoagulation range of warfarin is an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6 to 2.6 in patients aged over 70 years.. 14 NOAC dose reduction criteria include antiplatelet therapy, hepatic dysfunction, and low body weight as well as old age and renal dysfunction. However, rivaroxaban has a single dose reduction criterion as decreased creatinine clearance 15 to 50 mL/min. For the consideration of the above major determinants of NOAC dose reduction, the Korean Heart Rhythm Society added age 75 to 80 years old as rivaroxaban dose reduction criteria. 15 Following current guidelines on rivaroxaban dose reduction criteria, the present study aimed to focus on old age as the major determinant of rivaroxaban dose reduction.

Based on concerns about major bleeding risk from rivaroxaban in Asian patients, off-label rivaroxaban dose reduction to 15 mg is a common clinical practice in Asia. 16 The recently published XANAP study, which enrolled 2273 patients from 10 Asian countries, described real-world treatment of Asian patients with rivaroxaban. 9 More than half of Asians (50.2%) were prescribed a reduced dose of rivaroxaban, unlike the XANTUS study, in which only 20% were prescribed rivaroxaban 15 mg. 17 This present study shows similar real-world practices, reflecting common clinical practice in Korea in which more than half of elderly patients with AF (62.5%) take off-label rivaroxaban 15 mg.

However, no randomized clinical studies exist to determine the effects of low-dose rivaroxaban in elderly patients with normal renal function. Because rivaroxaban is partially eliminated by the kidneys, drug–blood concentrations in patients with normal renal function might decrease to subtherapeutic levels at low doses. 18 The use of NOAC doses inconsistent with drug labeling has been associated with worse outcomes; for example, underdosing with apixaban in patients with normal or only mildly reduced renal function is less effective (ie, has higher stroke rates) and confers no additional safety benefits. 19 In our study, compared with warfarin, on-label rivaroxaban 20 mg significantly improved primary and secondary NCBs, whereas off-label reduced rivaroxaban 15 mg did not. These results are similar to the XANTUS study, which showed that rates of major outcomes were worse in patients receiving a reduced rivaroxaban dose. 17 Our results suggest that in elderly AF patients with normal renal function, the standard dosing regimen (ie, 20 mg daily) may be more appropriate and should be considered for patients who there is no concern of increased bleeding risk.

Several study limitations must be considered. First, the study was based on retrospective data. Second, the sample size was relatively small compared with global studies. Third, the duration of each patient's time in therapeutic range (TTR) was unavailable, indicating the quality of INR-based control. Fourth, other major determinants of NOAC dose reduction criteria were not considered in the present study except age. The lower dosage group (R15) had a higher rate of major bleeding than R20, which suggests that there might be some residual confounding factor that clinicians selected lower dose on the basis of higher inherent bleeding risk. Therefore, there might be some selection bias, even though propensity score matching was performed. As such, these results can only suggest that rivaroxaban 20 mg may be a better option than rivaroxaban 15 mg for elderly Korean patients who are without renal dysfunction. Prospective, randomized trials are needed to determine comprehensively the optimal dose and best methods to obtain optimal TTRs in patients prescribed warfarin.

Conclusion

In real-world clinical practice with elderly Korean patients without renal dysfunction, rivaroxaban showed a similar risk of ischemic stroke and lower risk of major bleeding compared with warfarin. These real-world data indicate that more than half of elderly patients with AF in our sample were prescribed off-label rivaroxaban 15 mg. However, on-label rivaroxaban 20 mg significantly improved both primary and secondary NCBs, whereas off-label reduced rivaroxaban 15 mg did not confer these benefits. Clinicians should use caution in prescribing unreasonably low doses of rivaroxaban to elderly patients with AF.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2021R1F1A1048115) and a grant (BCRI21067) of Chonnam National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from the ethics committee at Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, South Korea (CNUH-2018-109).

Informed Consent: Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was not obtained and exempted because of the retrospective study protocol.

ORCID iD: Ki Hong Lee https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9938-3464

References

- 1.Lee SR, Choi EK, Han KD, Cha MJ, Oh S. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and estimated thromboembolic risk using the CHA2DS2-VASc score in the entire Korean population. Int J Cardiol. 2017 ;236:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for prevention of vascular events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9526):1903-1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen AY, Yao JF, Brar SS, Jorgensen MB, Chen W. Racial/ethnic differences in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(4):309-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SR, Choi EK, Han KD, Cha MJ, Oh S, Lip GYH. Temporal trends of antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in Korean patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the era of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong KS, Hu DY, Oomman A, et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in east asian patients from the ROCKET AF trial. Stroke. 2014;45(6):1739-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 european heart rhythm association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Europace. 2018;20(8):1231-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y-H, Shim J, Tsai C-T, et al. XANAP: a real-world, prospective, observational study of patients treated with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in Asia. J Arrhythm. 2018;34(4):418-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KH, Joung B, Lee S-R, et al. KHRS Expert consensus recommendation for oral anticoagulants choice and appropriate doses: specific situation and high risk patients. Korean J Med. 2018;93(2):110-132. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KH, Park HW, Lee N, et al. Optimal dose of dabigatran for the prevention of thromboembolism with minimal bleeding risk in Korean patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2017;19(supp_4):iv1-iv9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabir I, Khavandi K, Brownrigg J, Camm AJ. Oral anticoagulants for asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2014;11(5):290-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Wojdyla DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin among elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the rivaroxaban once daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared With vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation (ROCKET AF). Circulation. 2014;130(2):138-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation (JCS 2013). Cir J. 2014;78(8):1997-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joung B, Lee JM, Lee KH, et al. Korean Guideline of atrial fibrillation management. Korean Cir J. 2018;48(12):1033-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori M, Matsumoto M, Tanahashi N, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in Japanese patients With atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2012;76(9):2104-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camm AJ, Amarenco P, Haas S, et al. XANTUS: a real-world, prospective, observational study of patients treated with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(14):1145-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubitza D, Becka M, Roth A, Mueck W. The influence of age and gender on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53(3):249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao X, Shah ND, Sangaralingham LR, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Non-Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant dosing in patients With atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(23):2779-2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]