ABSTRACT

Bacteria have evolved a variety of enzymes to eliminate endogenous or host-derived oxidative stress factors. The Dps protein, first identified in Escherichia coli, contains a ferroxidase center, and protects bacteria from reactive oxygen species damage. Little is known of the role of Dps-like proteins in bacterial pathogenesis. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae causes pleuropneumonia, a respiratory disease of swine. The A. pleuropneumoniae ftpA gene is upregulated during shifts to anaerobiosis, in biofilms and, as found in this study, in the presence of H2O2. An A. pleuropneumoniae ftpA deletion mutant (ΔftpA) had increased H2O2 sensitivity, decreased intracellular viability in macrophages, and decreased virulence in a mouse infection model. Expression of ftpA in an E. coli dps mutant restored wild-type H2O2 resistance. FtpA possesses a conserved ferritin domain containing a ferroxidase site. Recombinant rFtpA bound and oxidized Fe2+ reversibly. Under aerobic conditions, the viability of an ΔftpA mutant was reduced compared with the wild-type strain after extended culture, upon transition from anaerobic to aerobic conditions, and upon supplementation with Fenton reaction substrates. Under anaerobic conditions, the addition of H2O2 resulted in a more severe growth defect of ΔftpA than it did under aerobic conditions. Therefore, by oxidizing and mineralizing Fe2+, FtpA alleviates the oxidative damage mediated by intracellular Fenton reactions. Furthermore, by mutational analysis, two residues were confirmed to be critical for Fe2+ binding and oxidization, as well as for A. pleuropneumoniae H2O2 resistance. Taken together, the results of this study demonstrate that A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA is a Dps-like protein, playing critical roles in oxidative stress resistance and virulence.

IMPORTANCE As a ferroxidase, Dps of Escherichia coli can protect bacteria from reactive oxygen species damage, but its role in bacterial pathogenesis has received little attention. In this study, FtpA of the swine respiratory pathogen A. pleuropneumoniae was identified as a new Dps-like protein. It facilitated A. pleuropneumoniae resistance to H2O2, survival in macrophages, and infection in vivo. FtpA could bind and oxidize Fe2+ through two important residues in its ferroxidase site and protected the bacteria from oxidative damage mediated by the intracellular Fenton reaction. These findings provide new insights into the role of the FtpA-based antioxidant system in the pathogenesis of A. pleuropneumoniae, and the conserved Fe2+ binding ligands in Dps/FtpA provide novel drug target candidates for disease prevention.

KEYWORDS: oxidative stress, FtpA, Dps, ferroxidase, Fenton reaction, virulence, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae

INTRODUCTION

All living organisms have to deal with oxidative stress to survive. With the action of ionizing radiation, oxygen molecules form three kinds of reactive oxygen species (ROS): superoxide (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (HO·). In microbial cells, endogenous O2− and H2O2 are mainly the results of accidental autoxidation caused by the impact of O2 upon flavoproteins such as glutathione reductase and fumarate reductase (1–4). In addition to endogenous ROS derived from the chemical oxidation of sulfur and reducing metals, and the photochemical reactions of chromophores in bacterial cells (5), host-derived ROS is also an important source of oxidative stress for pathogens. Host phagocytes carry out the respiratory burst in which NADPH oxidase produces O2− (6). Subsequently, in neutrophils, some H2O2 reacts with chloride ions to form the strong oxidizer, HOCl, due to the action of myeloperoxidase (7, 8). Exogenous O2− has no membrane permeability toward bacteria because of its negative charge, so it cannot directly cause oxidative damage, but its secondary product, H2O2, can easily penetrate into the bacterial cytoplasm and be toxic. H2O2, as an important source of oxidative damage, can inactivate dehydratases (5) and mononuclear Fe2+ enzymes (9, 10) by oxidation of iron. Inside the bacterial cells, H2O2 reacts with intracellular Fe2+ in the Fenton reaction (Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + HO− + HO·), generating hyperactive HO·, which can cause the inactivation of bacterial proteins such as iron-sulfur-dependent dehydratases, mononuclear iron proteins, and the ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (5). In addition, HO· oxidizes the nitrogenous base and the ribose of nucleotides, leading to DNA single-strand breaks and fatal damage to genetic material (11–13).

In order to resist the toxic effects of ROS, microorganisms have evolved a variety of ROS-scavenging proteins, including members of the superoxide dismutase family (SODs) which scavenge extracellular O2−, alkyl hydrogen peroxide reductase (AHP), and catalases G (KatG) and E (KatE) (14) which scavenge intracellular H2O2. As a conserved H2O2 signal response factor, the transcription factor OxyR (15, 16) strongly induces the expression of ahpCF and katG with an increase in intracellular exogenous H2O2 levels (17). When bacteria are exposed to redox-cycling compounds that trigger the elevation of intracellular O2−, the regulatory system SoxRS enhances the expression of sodA (18) and acrAB (19) to protect bacteria from damage by O2−.

As a member of the classic nucleoid-associated protein family, Dps was first discovered in Escherichia coli. The Dps of E. coli (EcDps) belongs to the mini-ferritin family, and forms a spherical hollow sphere composed of 12 monomers with negative charges on the inner and outer surfaces (20). Unlike traditional ferritins, EcDps prefers utilizing H2O2 to oxidize Fe2+ to Fe3+, followed by O2. Through oxidation at the conservative ferroxidase site (FOC), the product Fe3+ migrates to the nucleation center and is stored in the form of hydrous iron oxide (FeOOH) as mineralized cores (21, 22). The mineralization of iron by Dps is reversible: the immobilized iron can be released in the presence of a reducing agent and return to the cytoplasm through N-terminal or C-terminal residues (23–25). The oxidation of Fe2+ by Dps not only provides iron storage for bacteria, but it also inhibits the Fenton reaction and eliminates DNA damage by HO·. In addition, under starvation conditions, many Dps-like proteins can bind DNA (26, 27). The Dps-DNA complex enhances the resistance of DNA to DNase (20).

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, an important respiratory pathogen of swine, causes porcine infectious pleuropneumonia and is responsible for serious economic losses to the worldwide pig industry (28). It mainly colonizes the lower respiratory tract and can escape host clearance. Lysis of host cells and inflammation induced by the pathogen cause serious lung damage in the host. In the process of infection, A. pleuropneumoniae can be subjected to oxidative stress from exogenous ROS via phagocytes and from endogenous ROS via the collision of oxygen and flavoproteins. Several genes encoding different kinds of reductases as terminal electron acceptors involved in anaerobic respiration have been identified in the A. pleuropneumoniae genome (29). Genes encoding members of flavoproteins that participate in the electron respiratory transport chain were upregulated in A. pleuropneumoniae after a shift to anaerobic conditions (30). In addition to enzymes that directly scavenge ROS, e.g., superoxide dismutase C (SodC) (31), other proteins involved in ameliorating oxidative stress in A. pleuropneuroniae have also been reported. CpxR, belonging to the two-component system, positively regulates the synthesis of O antigen in A. pleuropneuroniae, and has been suggested to be involved in H2O2 resistance (32), as has the outer membrane channel component of the TolC1/TolC2 type 1 secretion system (33, 34). The Lon protein homologue LonA is required to conquer oxidative stress (35), and the polyamine-binding protein PotD2, responsible for maintaining the intracellular level of polyamines, has also been reported to contribute to H2O2 tolerance in A. pleuropneuroniae (36). However, the anti-oxidative stress mechanisms of these proteins are unknown.

In our previous study, a gene named ftpA was found to be upregulated in A. pleuropneumoniae during the shift from aerobic to anaerobic culture (30). This gene was also upregulated in a medium in which A. pleuropneumoniae forms a robust biofilm (37). These findings suggested that FtpA might be a stress response factor of A. pleuroneuroniae. FtpA is annotated as a protein considered a pili subunit structure in Haemophilus ducreyi (38). However, A. pleuroneuroniae FtpA shares no homology with the known pili proteins but has 32% identity and 72% similarity with EcDps (38). By analyzing the sequence, we found that FtpA contained a conserved ferritin domain with a highly homologous FOC site to that in EcDps. In this study, we focused on the possible anti-oxidative stress function of ftpA in A. pleuropneumoniae. The ftpA-deleted mutant showed reduced resistance to H2O2, was attenuated for survival in macrophages, and was attenuated for virulence in a mouse model of infection. The in vitro and in vivo experiments showed that FtpA inhibited the intracellular Fenton reaction by oxidizing and mineralizing Fe2+. The two iron-binding ligands in the FOC domain of FtpA were validated to be essential for the Fe2+ oxidizing ability of these proteins, and for the contribution of FtpA to H2O2 resistance of A. pleuropneumoniae.

RESULTS

FtpA contributes to A. pleuropneumoniae virulence and resistance to oxidative damage in vivo.

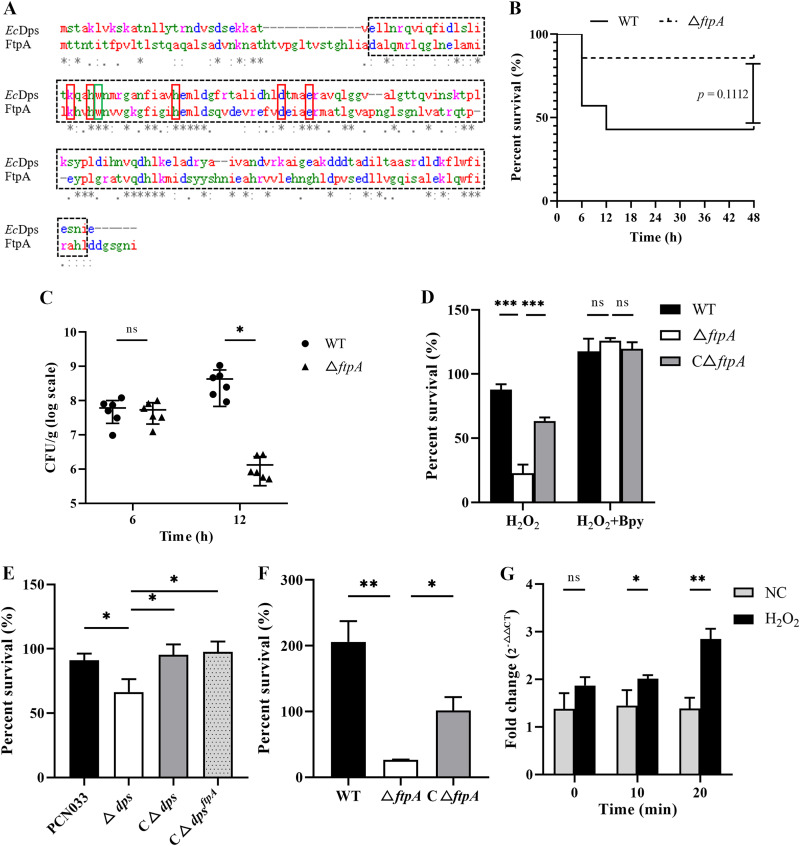

The CDS of A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA contained a conserved ferritin domain, located at 45 to 184 amino acid residues, which shared 72% similarity with EcDps. According to the sequence comparison results, FtpA and EcDps possess the same five iron-binding ligands in the FOC domain (21, 22), as well as Trp52, which, in EcDps, are responsible for the capture of free radicals (39) (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

FtpA has a role in A. pleuropneumoniae virulence and resistance to H2O2. (A) DNA sequence alignment of ftpA of A. pleuropneumoniae and dps of E. coli. The common ferritin domain (black dotted box), FOC sites (red box), and tryptophan free radical (green box) are shown. (B) The survival rates of mice infected with WT or ΔftpA. Four-week-old mice (n = 6) were infected nasally with 1 × 108 CFU (log phase). Survival rates were continuously recorded until 48 h postinfection. (C) Bacterial burden in the lungs of mice infected with 2 × 106 CFU of WT or ΔftpA at 6 and 12 h postinfection. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 6). (D) The H2O2 sensitivities of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA. Bacteria at 10,000 CFU were incubated with or without 500 μM 2,2′-bipyridine (Bpy) for 20 min, then treated with 250 μM H2O2 for 10 min. A control group without H2O2 treatment was also used (data not shown). (E) H2O2 sensitivities of PCN033, Δdps, CΔdps, and CΔdpsftpA. Strains at 10,000 CFU were treated with 250 μM H2O2 for 10 min. A control group without H2O2 treatment was also used (data not shown). (F) Intracellular survival of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA in macrophages. Bacteria were incubated with RAW 264.7 cells with an MOI of 10:1 for 4 h. Supernatants of the cells were discarded and the remainder were treated with antibiotics and incubated with fresh medium for an additional 0.5 h. Viable counts of bacteria inside macrophages were determined after lysis of the cells. Survival percentages of the strains are displayed as means ± SD (n = 3). (G) Influence of H2O2 on the expression level of the ftpA gene. The cDNA used as the templates were extracted from WT cultures (log phase) which had been incubated with 100 μM H2O2 for 0, 10, and 20 min. qRT-PCR was performed to determine the transcription level of ftpA using the 2−ΔΔCt method normalized to 16s rRNA genes. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 4). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***; P < 0.001, ns, not significant, as shown by Student's t test. Significant difference in the mortality of mice was analyzed by log rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

To identify the function of FtpA, the ftpA-deleted mutant strain ΔftpA and the complementary strain CΔftpA were constructed and confirmed by PCR using both gDNA and cDNA (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The virulence of ΔftpA was compared with that of the wild-type (WT) strain in a mouse infection model. The survival rate of mice infected with ΔftpA (86%) was higher than the rate for those infected with WT strain (43%) (P = 0.1112) (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, at a lower infection dose, the bacterial load of ΔftpA in the lungs of mice was significantly less than that of WT at 12 h postinfection (P < 0.05) but not at 6 h postinfection, indicating that the absence of ftpA weakened the ability of A. pleuropneumoniae to survive in the lungs at the later infection stage (Fig. 1C).

In order to investigate the possible anti-oxidative stress role of FtpA, the H2O2 resistance potentials of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were compared. After treatment with a high concentration of H2O2, ΔftpA showed significantly decreased survival compared with WT and CΔftpA (P < 0.001). Supplementation of 2,2′-bipyridine, a chelator-binding loose intracellular iron, together with H2O2 made the bacteria less sensitive to H2O2, and the growth difference between WT and ΔftpA disappeared (Fig. 1D). The control groups without H2O2 treatment showed no significant difference between the bacterial numbers of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA (data not shown). These results indicate that the low survivability of ΔftpA caused by H2O2 results from the Fenton reaction. To verify that ftpA and dps share a similar function in anti-oxidative stress capacity, the dps-deleted mutant strain Δdps and complementary strain CΔdps in porcine extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) PCN033 (40) were constructed (Fig. S2). The ftpA gene was introduced into Δdps (CΔdpsftpA). The Δdps also presented significantly reduced viability compared with PCN033 and CΔdps (P < 0.05), and both CΔdps and CΔdps ftpA showed restored tolerance to H2O2 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E), indicating that ftpA has an antioxidant ability similar to that of Dps.

The survival abilities of the WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA in macrophages were also assessed. Viable counts of ΔftpA inside macrophages was significantly lower than those of the WT (P < 0.05), and CΔftpA had a restored ability to survive inside macrophages to WT levels (Fig. 1F). At the same time, the results of cytotoxicity testing showed that the survival rates of macrophages infected with WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were not significantly different (Fig. S3). Additionally, the gene expression of ftpA was significantly upregulated after treatment with H2O2 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1G). These results demonstrated that FtpA, an EcDps-like protein, contributed to antioxidant capacity, survival in macrophages and virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae.

FtpA possesses the ability to capture and oxidize ferrous iron reversibly.

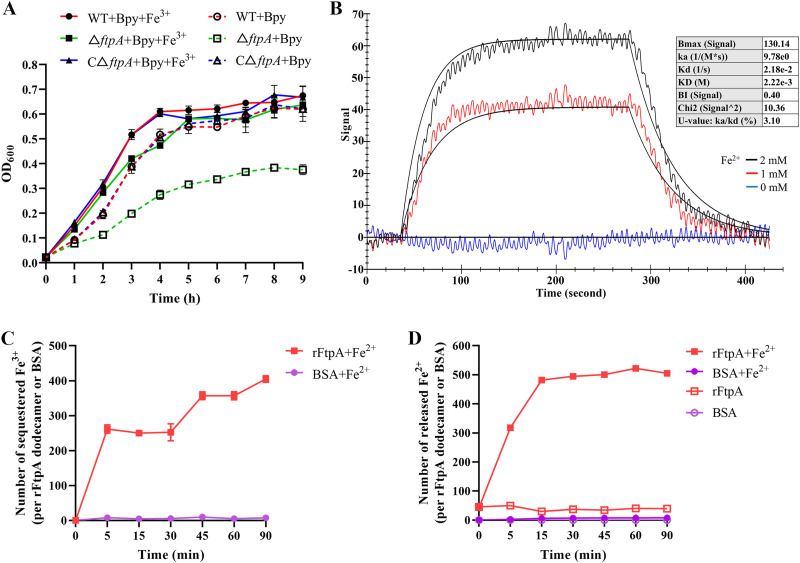

FtpA contains a conserved ferritin domain which may confer the capacity to oxidize free iron. To confirm this hypothesis, the ability of FtpA to capture iron was tested both in vivo and in vitro. The growth curves of the WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were determined under iron-restricted conditions generated by the addition of 2,2′-bipyridine, which chelates both Fe2+ and Fe3+. The mutant ΔftpA displayed a growth deficiency compared with the WT, which was reversed by CΔftpA (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the growth defect of ΔftpA was eradicated by adding excessive Fe3+ (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

FtpA possesses the ability to reversibly capture and oxidize ferrous iron. (A) Growth curves of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA under iron-restricted conditions. Growth curves of the bacteria were determined in medium containing 2,2′-bipyridine (solid symbols) or both 2,2′-bipyridine and ferric iron (hollow symbols) at an initial OD600 of 0.01. (B) Interaction between rFtpA and Fe2+. Molecular interaction was tested in a system containing rFtpA (6 μg) and either Fe2+ or Fe3+ (0, 1, and 2 mM) (Fig. S4) in PBS. Interaction parameters are presented in the box. (C) Identification of iron capture capacity of rFtpA. After incubation of 2.5 mM FeCl2 with 1 μM rFtpA at various times ranging from 0 to 90 min, the protein was removed and phenanthroline was added to detect residual Fe2+ in the solution of the reaction to measure the amount of Fe3+ sequestered per rFtpA dodecamer. (D) Release of iron bound by rFtpA. The rFtpA was preincubated with excess Fe2+, then the protein was separated and sodium ascorbate was added to reduce iron sequestered by rFtpA. Phenanthroline was applied to detect the amount of Fe2+ released from the rFtpA dodecamer. BSA was used as a negative control. Fe2+ added to Tris-HCl instead of protein was used as a blank control.

In vitro, the interaction of FtpA with iron and the capacity of FtpA to capture iron were assessed. Based on the results of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) using purified recombinant protein rFtpA with Fe2+ or Fe3+, rFtpA was found to interact with Fe2+ (Fig. 2B) but not with Fe3+ (Fig. S3). The binding signal of rFtpA with Fe2+ intensified with an increase in Fe2+ concentration (Fig. 2B). rFtpA was subsequently incubated with Fe2+. The amount of iron sequestration by FtpA was determined by adding phenanthroline. The results showed that the amount of sequestered Fe2+ increased gradually with elongated incubation times following rFtpA treatment, indicating that FtpA possesses the ability to bind Fe2+ in vitro (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, after adequate incubation with excess Fe2+, sodium ascorbate was used as a reducing agent to release the sequestered iron. The results showed that the Fe2+ released from rFtpA gradually increased; the rFtpA not incubated with Fe2+ also showed a low level of released Fe2+, which indicated that the binding of Fe2+ by rFtpA was reversible (Fig. 2D).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that FtpA is capable of capturing free Fe2+ reversibly, and may have an iron storage function in bacterial cells.

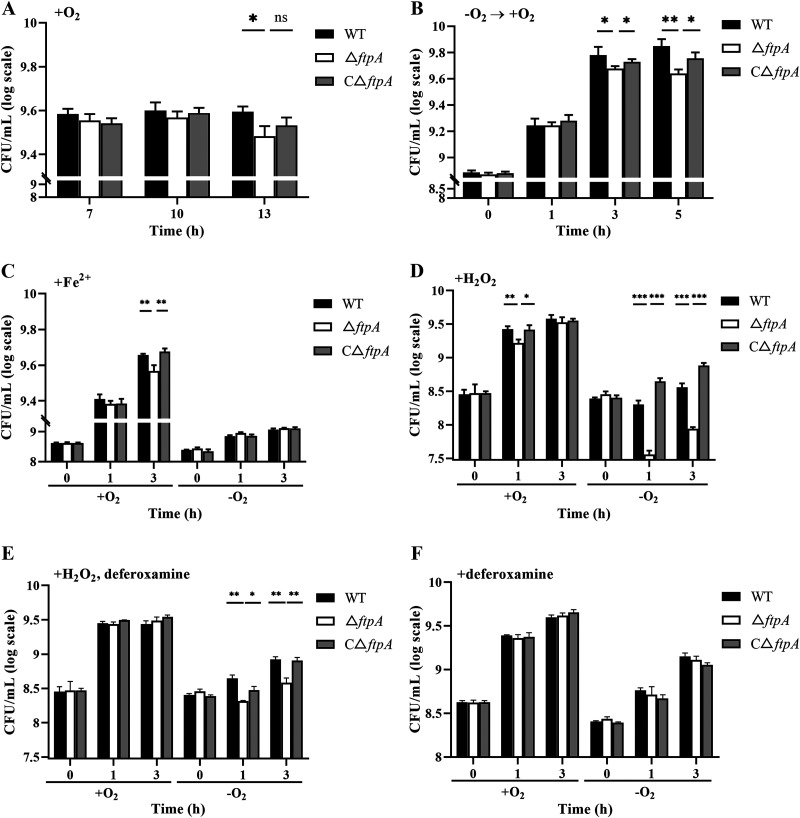

FtpA alleviates oxidative damage mediated by an intracellular Fenton reaction.

Intracellular oxidative damage to cells results from the Fenton reaction. Since FtpA was able to bind Fe2+, the substrate of the Fenton reaction, but not Fe3+, the product of this reaction, the possible ability of FtpA to protect against damage by the Fenton reaction was determined. There was no significant difference in growth of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA before the early stationary phase had been reached (before 10 h after subculture). However, at a longer aerobic culture time (13 h after subculture), where considerable ROS accumulating partially from the Fenton reaction would be anticipated (41), the viable count of ΔftpA was significantly lower than that of the WT (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A), and there was no significant difference in the growth abilities of the WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA in anaerobic culture (Fig. S5). In order to mimic oxidative stress to the bacteria during growth, they were shifted from anaerobic to aerobic conditions at early log phase. A growth defect in ΔftpA was found at 3 h and 5 h after the shift (Fig. 3B). Then, Fe2+ or H2O2, the substrate of the Fenton reaction, was added separately to bacterial cultures at the early log phase under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The survival defect of ΔftpA under aerobic conditions was observed at 2 h after supplementation with Fe2+ (P < 0.05). Under anaerobic conditions, the addition of Fe2+ did not inhibit the growth of ΔftpA, possibly due to the depletion of intracellular H2O2 (Fig. 3C). Compared with the WT, additional H2O2 caused a severe growth defect in ΔftpA which was more significant under anaerobic conditions (P < 0.001) than under aerobic conditions (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3D). When Fe2+ chelator deferoxamine was supplemented together with H2O2 (42), the growth difference between ΔftpA and the WT disappeared under aerobic conditions and decreased under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 3E). As a control, the chelator deferoxamine alone did not affect the growth ability of ΔftpA (Fig. 3F).

FIG 3.

FtpA alleviates oxidative damage mediated by the intracellular Fenton reaction. WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were continuously cultured aerobically for 13 h (A), or cultured anaerobically for 4 h and then transferred to an aerobic environment for an additional 5 h (B). Strains were cultured aerobically or aerobically for 2 h and then either 2.5 mM Fe2+ (C), 100 μM H2O2 (D), 100 μM H2O2 plus 200 μM deferoxamine (E), or deferoxamine alone (F) was added until stationary phase. Viable bacterial numbers were counted at selected time points. All data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, as indicated by Student’s t test.

Together, these results show that FtpA alleviates oxidative damage mediated by an intracellular Fenton reaction.

Identification of critical ligands involved in ferrous iron binding and FtpA anti-oxidative stress activity.

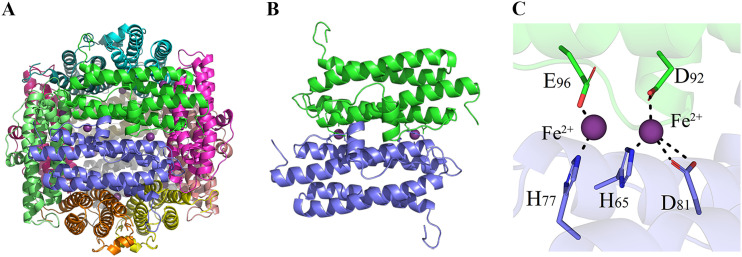

According to sequence comparison using the SWISS-MODEL database, the DpsA15 of Streptomyces coelicolor (43) shared the highest similarity with FtpA (47% identity and 44% similarity). Therefore, DpsA15 was chosen as the template for homologous modeling (Fig. 4A). The index quantitative structure quality estimate was 0.73, the index global model quality estimate was 0.61, and the index global and local absolute quality estimate was −1.62, which indicated the reliability of the modeling. The polymer structure of FtpA was demonstrated to be the major active state in physiological conditions via native PAGE (Fig. S4). To further analyze the structural characteristics of the ferroxidase sites of FtpA, we predicted the specific amino acid residues for substrate binding in the FOC cavity by molecular docking, which indicated a connection between the amino acid residues in the dimer and Fe2+ (Fig. 4B). The FOC consisted of five residues, of which three (His65, Asp81, and Asp92) were predicted to be responsible for high-affinity binding and two (His77 and Glu96) for low-affinity binding (21, 22) (Fig. 4C).

FIG 4.

Predicted structure of FtpA with iron binding ligands. (A) Homologous modeling of FtpA. Using S. coelicolor DpsA15 as the template, the monomer and dodecamer structures are shown. (B) Detailed illustration of binding forms of FtpA. The two monomers form a dimer in a central symmetric structure, with two FOC sites located at each interface. (C) Molecular docking of FtpA with Fe2+. The amino acid residues in the Fe2+-binding pocket were predicated to be H65, H77, D81, D92, and E96.

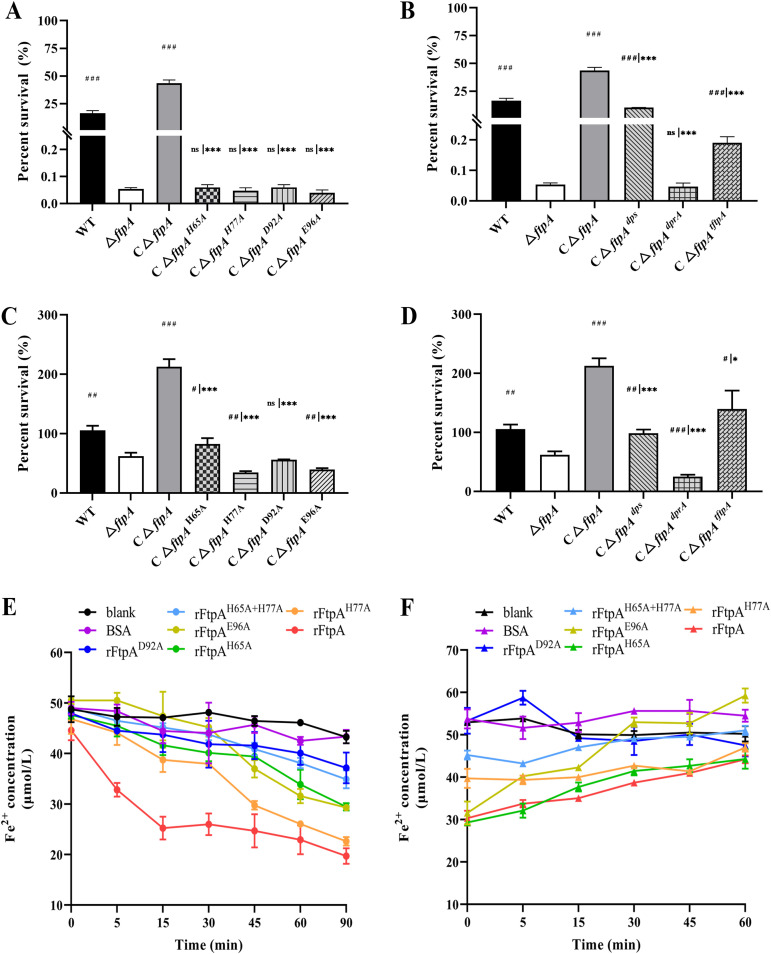

In order to validate which FtpA amino acid residues have key roles in binding and oxidation of Fe2+, point mutations of the four predicted Fe2+-binding residues that are also conserved in EcDps were constructed. The four mutated ftpA genes were inserted into the complementary vectors and introduced into ΔftpA (CΔftpAmut). When the strains were treated with 250 μM H2O2, the complementary strains carrying point mutations did not have the ability to resist H2O2 (Fig. 5A). Therefore, the residues His65, His77, Asp92, and Glu96 are critical for the anti-H2O2 ability of FtpA. Furthermore, the genes encoding EcDps, and the Dps-like protein DprA from Streptococcus suis (44), were also introduced into the mutant (CΔftpAdps and CΔftpAdprA). The results showed that EcDps could restore the deficiency of antioxidant stress of ΔftpA, while DprA could not (Fig. 5B). Additionally, a truncated ftpA lacking the upstream sequence before the ferritin domain-containing FOC of FtpA, a region with unknown function, was also cloned and integrated into ΔftpA (CΔftpAtftpA). H2O2 resistance could only be partially reversed in CΔftpAtftpA, indicating that the intact sequence was required for full function of FtpA (Fig. 5B). Additionally, complementary strains carrying point mutations were incubated with macrophages. The intracellular survival ratio showed that the strains with point mutations did not show restored survivability in macrophages compared to ΔftpA (Fig. 5C). However, CΔftpAdps and CΔftpAtftpA, but not CΔftpAdprA, displayed restored survivability in macrophages compared with ΔftpA, with CΔftpAtftpA showing significantly decreased survivability compared with CΔftpA (Fig. 5D).

FIG 5.

Confirmation of critical ligands involved in ferrous iron binding and anti-oxidative stress activity of FtpA. (A and B) Detection of H2O2 sensitivity. Complemented strains with point mutations in ftpA (CΔftpAH65A, CΔftpAH77A, CΔftpAD92A, or CΔftpAE96A) (A) or dps (CΔftpAdps), dprA (CΔftpAdprA), or tftpA (a truncated ftpA gene lacking the upstream sequence before the ferritin domain, CΔftpAtftpA) (B) (500 CFU) were treated with 250 μM H2O2 for 10 min. As a control, the WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA strains were treated in the same way. (C and D) Intracellular survival of strains. All of the above strains were incubated with RAW 264.7 cells for 4.5 h and viable counts were determined. (E) Comparison of iron oxidative ability of rFtpA and those carrying point mutations. Phenanthroline was used to assay Fe2+ concentration after incubation with 1 μM rFtpA or rFtpAmut at 37°C for 90 min. (F) Comparison of reversibility of iron oxidative abilities of rFtpA and rFtpAmut. Sodium ascorbate was added to the preincubated mixture containing 1 μM rFtpA or rFtpAmut with Fe2+ to reduce Fe3+ in the rFtpA or rFtpAmut at 37°C for 60 min. BSA was used as a negative control and Fe2+ added to PBS alone was used as a blank control. All data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). The symbols # and * represent the significance of the difference compared with ΔftpA or CΔftpA, respectively. # or *, P < 0.05; ## or **, P < 0.01; ### or ***, P < 0.001, as indicated by Student’s t test.

These mutated ftpA genes were also cloned and introduced into E. coli BL21 to obtain mutated recombinant proteins of FtpA (rFtpAmut) which maintained their activity to form polymers (Fig. S4). According to the Fe2+ levels indicated by phenanthroline assay, the final Fe2+ concentrations in the solution incubated with rFtpAmut were higher than those in rFtpA (Fig. 5E). rFtpAH77A and rFtpA had equivalent levels after a 90-min incubation with Fe2+. The mutants rFtpAH65A and rFtpAE96A showed attenuated binding capacity to Fe2+ compared with rFtpA. The mutant rFtpAD92A had a significantly diminished ability to bind Fe2+. Furthermore, the combination of mutated H65A and H77A led to a loss of binding with Fe2+. After treatment with exogenous reductant, the increased concentration of Fe2+ released by rFtpAH65A or rFtpAH77A shared similar trends to that of rFtpA. However, the combination of mutated H65A and H77A released much more Fe2+ compared with rFtpA. The mutant rFtpAD92A lost the ability to release Fe2+, while rFtpAE96A showed a decreased ability to release Fe2+ compared with rFtpA (Fig. 5F).

Together, these findings indicate that FtpA contained conserved ferroxidase sites, of which Asp92 and Glu96 were critical for the iron binding and the anti-oxidative stress function of FtpA, while His65 and His77 also contributed to these functions.

DISCUSSION

In the process of infection, pathogens have to encounter both exogenous and endogenous ROS. Host phagocytes are a major exogenous source of ROS. Phagocytosis leads to the direct exposure of pathogens to high concentrations of H2O2 (100 μM), which is produced via the respiratory burst of NADPH oxidase in phagosomes (41). Even if the extracellular concentration of H2O2 is only 5 μM, the intracellular concentration can easily reach toxic levels (1 μM) in pathogens via rapid diffusion (45). Endogenous ROS can be produced from autoxidation by non-respiratory flavoproteins of bacteria, and this allows the Fenton reaction using H2O2 and free Fe2+ as the substrate to proceed. The reaction rate constant of the Fenton reaction in physiological conditions is 2 orders of magnitude higher than it is under an acidic pH environment, indicating that this reaction may easily occur in bacterial cytoplasms (42). Free Fe2+ can be released from iron-proteins damaged by ROS (46). Thus, the availability of the intracellular Fe2+ pool is critical in preventing the Fenton reaction. In addition to the ROS-scavenging enzymes and related regulatory systems, Dps, first found in the model organism E. coli, has been considered to be responsible for restricting the intracellular Fe2+ pool and the consumption of H2O2 (20).

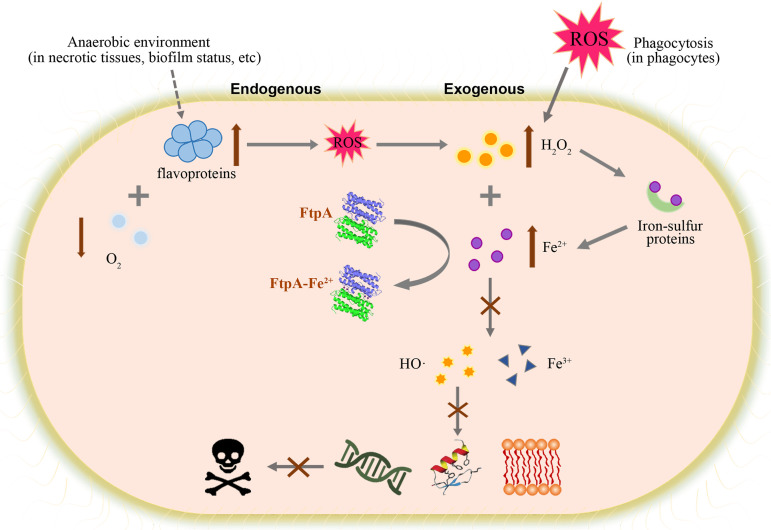

At present, there are limited reports on the molecular function and role in virulence of Dps proteins in pathogens. Dps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was reported to be involved in bacterial resistance to H2O2, survival in macrophages, and virulence (47). Deletion of the Dps-like protein Fri reduced the colonization ability of Listeria monocytogenes in the liver and spleen of mice (48). In Campylobacter jejuni, Dps promoted the development of intestinal microscopic lesions in piglets (49). Deletion of Dps in Riemerella anatipestifer resulted in reduced bacterial burdens in multiple organs of ducklings during late infection (50). These findings suggest that Dps is related to the persistence of pathogens in the host. However, the mechanism of virulence attenuation caused by dps gene deletion was not further explained in these reports. In this study, the Dps-like protein FtpA was identified in A. pleuropneumoniae. The mutant of ftpA showed reduced virulence in mice. In vitro studies indicated that A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA contributes to resistance to H2O2 and phagocytosis, and that it can be upregulated by H2O2. Moreover, FtpA can restore the growth defect of Δdps treated with H2O2 in E. coli. All of these results indicate that ftpA and dps share functional similarity in resistance to oxidative stress. A conserved FOC domain was found in FtpA by sequence alignment. Subsequently, SPR and phenanthroline assays verified the reversible binding and oxidation ability of Fe2+ in FtpA. In addition, a growth defect in ΔftpA occurred in long-duration aerobic culture or due to a shift from anaerobic to aerobic conditions. Excessive H2O2 could result in growth deficiency in ΔftpA. As another substrate of the Fenton reaction, Fe2+ also inhibited the growth of ΔftpA in aerobic conditions. This inhibition disappeared in anaerobiosis, possibly because hypoxia leads to the depletion of intracellular H2O2 production. H2O2 together with an iron chelator diminished the differences between WT and ΔftpA in aerobic conditions, and decreased those differences in anaerobic conditions. The difference in anaerobiosis could not be completely eliminated by chelator, perhaps due to the weaker chelation of Fe2+ by deferoxamine in the presence of oxygen. Altogether, by binding with Fe2+, FtpA protects bacteria from the oxidative damage mediated by Fenton reaction. These results reflect the typical characteristics of a Dps-like protein. Therefore, during A. pleuropneumoniae infection, FtpA has a primary role in resisting oxidative stress by restricting Fe2+, which in turn limits the intracellular Fenton reaction (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

FtpA has a role in resisting oxidative stress by restricting Fe2+ and alleviating oxidative damage mediated by the intracellular Fenton reaction. When exposed to ROS released from phagocytes or endogenous ROS from autoxidation of flavoproteins, H2O2 accumulates to inactivate iron-sulfur proteins. The released Fe2+ reacts with H2O2 in the Fenton reaction to generate toxic HO·. As an anti-oxidative stress protein, FtpA interferes with the Fenton reaction by binding with and oxidizing Fe2+, and therefore protects the bacteria from damage by HO·. This process may be important to A. pleuropneumoniae survival in an anaerobic environment in necrotic tissue and/or biofilms.

Unlike the upregulation of EcDps, which is caused by exposure to H2O2 stress (51), the upregulation of FtpA is not only activated by H2O2; it is also induced by reduced oxygen levels, (30) and in biofilms (37), which are also considered to be anaerobic environments. Moreover, the ΔftpA mutant is more sensitive to H2O2 under anaerobic conditions than under aerobic conditions. Therefore, it seems that the function of FtpA is more important under anaerobic conditions. In lung tissue, A. pleuropneumoniae can survive in an oxygen-limited environment during infection, which results from rapid oxygen depletion during the early stage of infection and oxygen exhaustion in necrotic tissue (52). During these infection periods, exposure to high ROS levels from phagocytic attack would rapidly damage bacterial cells; upregulation of ftpA contributes to protecting the pathogen from oxidative damage from both exogenous and endogenous ROS (Fig. 6).

The polymer structure and the conserved iron binding ligands of FtpA of A. pleuropneumoniae were also validated in this study. In EcDps, there is a high-affinity and a low-affinity Fe2+-binding site located at the interface of two protein monomers (21, 22). The dodecamer structure endows EcDps with excellent iron storage potential, although the iron mineralization site has not yet been determined (53). Homology modeling showed that FtpA and Dps shared similar dodecamer structures and FOC sites, indicating that FtpA may be an iron storage protein. The absence of FtpA may reduce intracellular iron storage, as reflected by the poor growth of ΔftpA in iron-restricted media and its recovery after treatment with excess Fe3+. From the results of molecular docking analysis of FtpA and sequence alignment, four conserved residues involved in Fe2+-binding reported in EcDps were predicted in FtpA, which were validated by functional point mutation in vitro and in vivo studies. The results demonstrated that Asp92 and Glu96 were critical for the binding of Fe2+ and for the anti-oxidative stress function of FtpA. In EcDps, the residue corresponding to Asp92 is part of the high-affinity binding site for Fe2+, while the one corresponding to Glu96 is responsible for both high- and low-affinity binding (21, 22). The combined substitution of His65 and His77 in A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA resulted in a loss of oxidative ability in FtpA, compared with single point mutations of these two residues. His65 and His77 correspond to the high-affinity and low-affinity binding Fe2+ ligands in EcDps, respectively. In A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA, Asp92 and Glu96 are the most critical residues for binding and oxidation of Fe2+ among the four residues, while His65 and His77 help to guarantee the functional integrity of the FOC site. Heterologous complementation using the gene encoding EcDps and another member of the Dps-like proteins, the DprA reported in S. suis, was also conducted. EcDps could restore the capacity of ΔftpA to resist H2O2 and its survival in macrophages. Although FtpA shares a potential residue for iron-binding (Asp81) with that of DprA (Asp63) (54), DprA could not substitute for FtpA in A. pleuropneumoniae possibly because there is no significant similarity between their CDSs. Additionally, there is a 132-bp sequence upstream of the coding region for the ferritin domain of FtpA which has no homologous sequence in the databases. Complementation using a truncated FtpA lacking this encoded sequence led to significantly reduced H2O2 resistance and survivability in macrophages compared with to the strain complemented by the intact FtpA. Thus, the upstream sequence of the ferritin domain also contributed to the function of FtpA, and we speculate that it enhances protein stability. In general, FtpA of A. pleuropneumoniae shared high structural and functional similarities with EcDps. Analysis of the key active ligands shows that Fe2+ provides the basis for the prediction of compounds that can inhibit the interaction.

In addition to its ferroxidase function, we also detected whether FtpA possesses DNA-binding potential. The nonspecific DNA-binding ability of EcDps likely relies on three lysine residues (K5, K8, and K10) in the N-terminal tail (20, 55). However, the Dps-like proteins of some known species do not share this feature (56). FtpA did not bind either A. pleuropneumoniae genomic or plasmid DNA (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), possibly due to the lack of an N-terminal tail rich in positively charged residues equivalent to that of EcDps. In H. ducreyi, the gene ftpA was as annotated as one encoding a fine tangled pili major subunit gene, and was reported to be essential for pili formation in this bacterium (38). FtpA of H. ducreyi shares no homology with known pili proteins but does have homology with EcDps and with Treponema pallidum antigen TpF1 or 4D (38). However, it seems that FtpA is not required for full virulence in H. ducreyi (57). In A. pleuropneumoniae, two different pili have been identified. The type IV pilus, which uses ApfA as its structure protein, is a cell contact-induced pilus and is important for adhesion and virulence in mice (58, 59). The Flp pilus, encoded by a large operon of 14 genes, also mediates A. pleuropneumoniae adhesion and colonization in vivo (60). In this study, deletion of ftpA did not reduce the adhesion ability of A. pleuropneumoniae (data not shown), but it significantly reduced the anti-oxidative stress capacity of this pathogen. The FtpA of H. ducreyi shares high similarities (82% identity) with that of A. pleuropneumoniae; it also contains the four Fe2+ binding ligands in its FOC site, which implies that FtpA of H. ducreyi may also possess the ferroxidase function.

In summary, this study identifies that A. pleuropneumoniae FtpA has an anti-oxidative function and contributes to the virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae. In this Dps-like protein, the FOC site with four Fe2+ binding residues has critical roles in reversible binding to and oxidation capacity of Fe2+, inhibition of the intracellular Fenton reaction, and protection of the bacterium from H2O2 and macrophages. This process may be important for the resistance of this pathogen to both exogenous and endogenous oxidative stress during the later infection stage. These results provide new insights into the roles of antioxidant systems in the virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae. Further studies of specific regulation of A. pleuropneumoniae ftpA under different O2 conditions will enable a more complete understanding of the function of FtpA during the life cycle of this major pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, cells, plasmids, primers, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, cells, plasmids, and primers used in this study are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Among these strains, E. coli DH5α and DH5α λpir (Trans, Beijing, China) were used for cloning, E. coli BL21 (Trans, Beijing, China) for protein expression, and E. coli β2155 (61) and χ7213 (62) for transconjugation. All E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) or on LB agar plates, and incubated at 37°C. Ampicillin (100 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (12.5 and 20 μg/mL), apramycin (150 μg/mL) and kanamycin (25 μg/mL) were used to screen the E. coli transformants when necessary. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP, 50 μg/mL) was supplemented into the medium for the growth of E. coli β2155 and χ7213. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.75 mM) was used to induce the expression of recombinant protein in E. coli BL21. All A. pleuropneumoniae strains, including WT 4074 (reference strain of serovar 1), ΔftpA, and CΔftpA strains, were cultured in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA) or on Tryptic Soy Agar plates (TSA, Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA). Additionally, 10 μg/mL of NAD was added for the growth of A. pleuropneumoniae, chloramphenicol (2 μg/mL) was added for the construction of CΔftpA strains, and apramycin (150 μg/mL) was added for the construction of CΔdps strains of E. coli PCN033. Mouse leukemia cells of monocyte macrophage (RAW264.7) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco, Waltham MA, US) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Construction of mutant and complementary strains.

To construct the A. pleuropneumoniae ftpA-deleted mutant (ΔftpA), the upstream and downstream fragments of ftpA were amplified with primers ftpA-U-F/R and ftpA-D-F/R, respectively, using the gDNA from A. pleuropneumoniae WT as the template. The PCR products were used as the templates for overlapping extension PCR to amplify the fusion fragment ftpA-UD with primers pSK-F/R. The resultant fragment digested with restriction enzymes XhoI and HindIII was inserted into cloning vector pBluescript II SK (+). Thereafter, the PCR products of ftpA-UD using the primers pEMOC2-F/R were treated with the same restriction enzymes and then inserted into the suicide vector pEMOC2 (61). The resultant plasmid pEM-ftpAUD was transformed into E. coli β2155 acting as a donor, then incubated with WT to perform transconjugation. Chloramphenicol (2.5 μg/mL) and 10% d-(+)-sucrose were used to induce the two-step homologous recombination in WT carrying the plasmid pEM-ftpAUD to obtain the ftpA deleted mutant (63). Correct mutants were identified via amplification and DNA sequencing of ftpA and flanking regions. To confirm that the deletion did not influence the expression of upstream and downstream genes, PCR and RT-PCRs targeting the upstream and downstream genes using gDNA and cDNA, respectively, of the identified ΔftpA as the template were performed.

The construction of E. coli PCN033 dps-deleted mutant (Δdps) was as follows. The primers dps-U-F/R and dps-D-F/R were used to amplify upstream and downstream fragments of dps, respectively, using the gDNA from E. coli PCN033 as the template. The PCR products were inserted into the cloning vector pRE112 (64) digested with restriction enzymes NdeI and KpnI, and the resultant plasmid pRE-dpsUD was transformed into E. coli χ7213 (62) acting as a donor to perform transconjugation. Chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL) and 5% d-(+)-sucrose were used to induce the two-step homologous recombination. Screening and identification methods for Δdps were the same as those for ΔftpA.

To construct the complementary vectors, the CDS of intact ftpA or truncated ftpA, dps from E. coli, and dprA from S. suis were amplified from gDNA of the WT, E. coli PCN033 and S. suis SC19, using the primers pJF-ftpA-F/R, pJF-tftpA-F/pJF-ftpA-R, pJF-dps-F/R, and pJF-dprA-F/R, respectively. The purified PCR products were inserted into the vector pJFF224-XN (65) digested with restriction enzymes SalI and NotI to obtain the complementary vectors pJF-ftpA, pJF-ftpAtftpA, pJF-ftpAdps, and pJF-ftpAdprA, respectively. To construct the complementary vectors carrying the CDS of ftpA with point mutations (H65A, H77A, D92A, E96A), the ftpA genes were amplified as two segments with reverse complementary connections, where the specific bases to be mutated were substituted in corresponding primers. The two segments were recombined and inserted into the vector pJFF224-XN. The transformants carrying pJF-ftpAmut, including pJF-ftpAH65A, pJF-ftpAH77A, pJF-ftpAD92A, and pJF-ftpAE96A were obtained by screening them on plates with chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL). All of the resulting complementary vectors were electroporated into the mutant ΔftpA. The confirmation of different complementary genes in ΔftpA was conducted by PCR.

For construction of E. coli PCN033 complementary strains, the CDS of intact ftpA and dps were amplified from gDNA of the A. pleuropneumoniae WT and E. coli PCN033 using the primers pHSG-dps-F/R and pHSG-ftpA-F/R, respectively. The PCR products were inserted into the vector pHSG396 digested with restriction enzymes SalI and KpnI to obtain complementary vectors. Apramycin (150 μg/mL) was applied to screen the complementary strains. The transformation of vectors and the identification of complementary strains were conducted by PCR.

Sequence alignment, homology modeling, and molecular docking.

The sequence alignment of ftpA (WP_005598741.1) and Ecdps (WP_000100800.1) was performed by the amino acid sequence obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein). The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST.cgi) was used for sequence analysis. The preliminary homology model of FtpA was built and presented via the SWISS Model Server (66) with DpsA15 as the template from Streptomyces coelicolor, which shared the highest similarity with FtpA. The quantitative structure quality estimate (reliable value of >0.7), global model quality estimate (reliable value of 0 to 1), and global and local absolute quality estimate indicating the reliability of the modeling were calculated. In addition, the optimal homology model was promoted by MODELLER v9.18 and determined by the probability density function (PDF) value. The molecular docking of FtpA with substrate Fe2+ was conducted via AutoDock v4.2. The 3D structure was generated using ChemDraw v20.

Expression and purification of recombinant protein rFtpA.

The ftpA fragment amplified from gDNA of WT by primers pET-ftpA-F/R was inserted into the vector pET-28a-c(+) and introduced into E. coli DH5α to screen transformants (pET-ftpA) with kanamycin (25 μg/mL) as the selection. Subsequently, the expressing plasmid pET-ftpA was transformed into E. coli BL21. The transformant was cultured to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.7, and 0.75 mM IPTG was used to induce protein expression for 4 h. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole [pH 7.5]) and cellular contents were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min after high-pressure crushing. Affinity chromatography was used for protein purification. The recombinant proteins with His-tags were added to Ni-Sepharose columns followed by elution and collection on a BioLogic Chromatography System. A gradient of buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) and buffer B1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole [pH 7.5]) was used. Protein detection was by UV absorption peak, and fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Imidazole was removed by ultrafiltration with buffer B2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]).

In order to identify the polymer form of protein in physiological conditions, native-PAGE was used to detect the natural form of rFtpA (or rFtpAmut) or the denatured form of rFtpA (treated with loading buffer containing SDS). Sufficient ultrafiltration was necessary for the complete removal of SDS.

Mouse infection assays.

The virulence of WT and ΔftpA was compared in the Kunming mouse infection model. Briefly, 4-week-old female mice were randomly divided into 5 groups (n = 6). Two groups were infected with WT and ΔftpA and monitored for mortality, and another two groups were infected with WT and ΔftpA to evaluate tissue colonization. The remaining group was used as a negative control. Mice were anesthetized by 1.25% tribromoethanol with a dosage of 450 μL/25 g. Mid-log-phase cultures of bacterial strains at a dosage of 1 × 108 CFU/20 μL were used to infect mice by nasal drip. The survival rates were recorded up to 60 h. The same infection method, but using a dose of 2 × 106 CFU/20 μL, was used to measure the tissue colonization of the strains. At 6 h and 12 h postinfection, mice were euthanized by exposure to diethyl ether. The lungs of the mice were collected and homogenized. Bacterial numbers in the homogenates were quantified by plating the diluted homogenates onto agar.

H2O2 sensitivity assay.

To determine the H2O2 resistance abilities of the bacteria, the strains of A. pleuropneumoniae or E. coli PCN033 were cultured to log phase, centrifuged, and resuspended into phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) to a concentration of 10,000 CFU/20 μL. The bacteria were cultured in either TSB containing 10 μg/mL NAD, or in LB, and were incubated with or without 500 μM 2,2′-bipyridine at 37°C for 20 min. Subsequently, the mixtures were treated with 250 μM H2O2 for 10 min. Bacterial culture without H2O2 treatment was used as the control. Bacterial numbers were quantified by viable counting. The results are shown as the proportion of live bacteria numbers in the H2O2-treated group compared with that of the control group.

Intracellular viability in macrophages.

To measure the survivability of bacteria in macrophages, A. pleuropneumoniae strains were cultured to log phase, centrifuged, and resuspended into DMEM. The bacteria were incubated with RAW 264.7 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5:1. After incubation for 4 h, planktonic bacteria were removed by washing with fresh PBS and adherent bacteria were killed by incubation with DMEM containing penicillin and streptomycin for 0.5 h. As the control group, RAW 264.7 cells were washed thoroughly and disrupted by double-distilled water (ddH2O). Intracellular live bacterial numbers were quantified by viable counting. As per the test group, the RAW 264.7 cells containing phagocytic bacteria were washed without lysis and then cultured for another 0.5 h, followed by washing, disruption by ddH2O, and viable counting. The results are shown as the proportion of live bacterial numbers in the test group compared with that of the control groups. As another control, the cytotoxicity caused by different strains was measured using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay based on the detection of dehydrogenase availability in the mitochondria of living cells.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

To determine whether the ftpA gene was induced by H2O2, A. pleuropneumoniae WT was subcultured until reaching OD600 = 0.1. Bacteria were treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 0, 10, and 20 min, with the untreated group as a control. The total RNA of these cultures was extracted by an RNA isolation kit (Tianmo Biotech, China). HiScript Q Select RT SuperMix (+ gDNA wiper) was applied for residual gDNA removal and cDNA synthesis (Vazyme, China). Using cDNA as the template, qPCR was performed with a TaKaRa TB Green Premix Ex Taq II kit (TaKaRa Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a QuantStudio 6 Flex fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher, USA). The expression level of the ftpA gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized to a 16s rRNA gene.

Growth curve determination.

Overnight cultures of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were subcultured at an initial OD600 of 0.02 in 10 mL of either TSB containing 10 μg/mL NAD and 150 μM 2,2′-bipyridine (Bpy), or TSB containing10 μg/mL NAD, 150 μM Bpy, and 100 μM FeCl3, at 37°C at 170 rpm. The OD600s were recorded until growth reached the stationary phase.

Biomolecular interaction analysis of rFtpA with Fe2+/Fe3+.

Based on SPR technology, biomolecular interaction analysis was performed to detect the binding capacity of rFtpA to Fe2+ or Fe3+. In brief, the Carboxyl sensor chip (COOH chip; Nicoya Lifesciences Inc.) was prepared according to the OPENSPRTM operation procedure. PBS (pH 7.4) was used to wash channels at 150 μL/min until signals reached the baseline. Channels were defoamed by the injection of 200 μL of 80% isopropanol, washing of the loading loop with PBS, and evacuation. A solution of 400 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) with 200 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (1:1) was preloaded, followed by loading at 20 μL/min for 4 min of a solution of 6 μg rFtpA diluted into an active buffer with 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 3.5). Ethanolamine-HCl at 15 mM was used to immobilize FtpA protein. The ligands of ferrous iron (FeCl2) or ferric iron (FeCl3) diluted into PBS were incubated with the protein. Tests were carried out at 25°C and conducted in triplicate. The relevant parameters are presented in the attached box in Fig. 2B: Bmax (Signal), the maximum signal related to the amount of labeled ligand and the concentration of analyte; ka, association rate constant; Kd, dissociation rate constant; KD, affinity constant; BI (Signal), concentration effect; Chi2 (signal2), deviation between the experimental data (original curve) and the fitted curve; U-value, accuracy of dynamic fitting. The results were analyzed using TraceDrawer (Ridgeview Instruments AB, Sweden) with a One-to-One model.

Detection of capacity of rFtpA to oxidize Fe2+.

The reagent ferrozine, which can chelate Fe2+ and form a purple complex, was used to measure the Fe2+ oxidative capacity of rFtpA. This assay was carried out under aerobic conditions. Reactions containing 2.5 μL FeCl2 at 2.5 mM and 97.5 μL rFtpA or rFtpAmut at 1 μM in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) were carried out for 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min at 37°C. After the reaction, the rFtpA was removed by ultrafiltration tubes and 5 μL of 1 mM ferrozine was added into the filtrate. The concentration of free Fe2+ in the filtrate was determined by measuring the OD562 and was calculated by standard curves. The results are shown as the amount of Fe2+ oxidized per dodecamer rFtpA, excluding the Fe2+ directly oxidized by oxygen. For the mutant proteins of rFtpA (rFtpAmut), the postreaction solution was directly treated with ferrozine and the results are shown as the concentration of free Fe2+. To determine whether FtpA-mediated oxidized Fe2+ could be reversed, 97.5 μL rFtpA or rFtpAmut at 1 μM was preincubated with 2.5 μL FeCl2 at 2.5 mM for 90 min. After separation of rFtpA in ultrafiltration tubes, 10 μL sodium ascorbate at 1.5 M was applied to reduce and release the Fe2+ sequestered in rFtpA. After incubation for 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min, the free Fe2+ was also determined using 1 mM ferrozine. The results are shown as the amount of Fe2+ released per dodecamer rFtpA. For the mutant proteins of rFtpA (rFtpAmut), the preincubated rFtpA was directly treated with sodium ascorbate, and the results are shown as the concentration of free Fe2+. Groups with BSA instead of rFtpA or rFtpAmut were used as negative controls. Groups without proteins were used as blank controls.

Testing the ability of FtpA to alleviate oxidative damage mediated by the intracellular Fenton reaction.

Overnight cultures of WT, ΔftpA, and CΔftpA were subcultured at an initial OD600 of 0.005 at 37°C, 170 rpm and were continuously cultured for 13 h in aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Bacterial numbers were counted at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 13 h. In another experiment, the bacteria were subcultured until reaching an OD600 of 0.1, and one group was cultured in an anaerobic environment for 4 h and shifted to aerobic conditions for 5 h, during which the bacterial numbers at 0, 1, 3, and 5 h after the shift were counted. In the other groups, the bacteria were cultured aerobically or anaerobically for 2 h and then supplemented with 2.5 mM Fe2+, 100 μM H2O2, 100 μM H2O2 plus 200 μM deferoxamine, or 200 μM deferoxamine alone until cultured to stationary phase. The bacterial numbers at 0, 1, and 3 h after the shift were counted.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism v8 was used to analyze the significant difference of averages by the independent sample t test (Student's t test). The results were presented as “X ± SD (standard deviation).” In addition, the significant difference of mortality of mice was analyzed by log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Values with P > 0.05 indicate no significant difference, and values with P < 0.05 indicate a significant difference.

Four-week-old female Kunming mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Huazhong Agricultural University. The animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Monitoring Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University, and were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations of “The guides for nursing and use of experimental animals in Hubei Province” (approval no. HZAUMO-2020-0061).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572535), the National Key R & D Program of China (2017YFD0500201), the Applied Basic Frontier Projects of Wuhan (2018020401011300), and the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/S019901/1).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Lu Li, Email: lilu@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Julie A. Maupin-Furlow, University of Florida

REFERENCES

- 1.Boveris A, Chance B. 1973. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J 134:707–716. 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imlay JA, Fridovich I. 1991. Superoxide production by respiring membranes of Escherichia coli. Free Rad Res Comms 12–13:59–66. 10.3109/10715769109145768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kussmaul L, Hirst J. 2006. The mechanism of superoxide production by NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:7607–7612. 10.1073/pnas.0510977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messner KR, Imlay JA. 1999. The identification of primary sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide formation in the aerobic respiratory chain and sulfite reductase complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 274:10119–10128. 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imlay JA. 2013. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:443–454. 10.1038/nrmicro3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang FC. 2004. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:820–832. 10.1038/nrmicro1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klebanoff SJ. 1968. Myeloperoxidase-halide-hydrogen peroxide antibacterial system. J Bacteriol 95:2131–2138. 10.1128/jb.95.6.2131-2138.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foote CS, Goyne TE, Lehrer RI. 1983. Assessment of chlorination by human neutrophils. Nature 301:715–716. 10.1038/301715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anjem A, Imlay JA. 2012. Mononuclear iron enzymes are primary targets of hydrogen peroxide stress. J Biol Chem 287:15544–15556. 10.1074/jbc.M111.330365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobota JM, Imlay JA. 2011. Iron enzyme ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase in Escherichia coli is rapidly damaged by hydrogen peroxide but can be protected by manganese. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:5402–5407. 10.1073/pnas.1100410108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson F. 1985. Chemical changes induced in DNA by ionizing radiation. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol 32:116–154. 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dizdaroglu M, Rao G, Halliwell B, Gajewski E. 1991. Damage to the DNA bases in mammalian chromatin by hydrogen peroxide in the presence of ferric and cupric ions. Arch Biochem Biophys 285:317–324. 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90366-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Candeias LP, Steenken S. 1993. Electron transfer in di(deoxy)nucleoside phosphates in aqueous solution. Rapid migration of oxidative damage (via adenine) to guanine. J Am Chem Soc 115:2437–2440. 10.1021/ja00059a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 183:7173–7181. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslund F, Zheng M, Beckwith J, Storz G. 1999. Regulation of the OxyR transcriptional factor by hydrogen peroxide and the cellular thiol-disulfide status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:6161–6165. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi H, Kim S, Mukhopadhyay P, Cho S, Woo J, Storz G, Ryu SE. 2001. Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell 105:103–113. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng M, Wang X, Templeton LJ, Smulski DR, LaRossa RA, Storz G. 2001. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol 183:4562–4570. 10.1128/JB.183.15.4562-4570.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomposiello PJ, Bennik MH, Demple B. 2001. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J Bacteriol 183:3890–3902. 10.1128/JB.183.13.3890-3902.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma D, Cook DN, Alberti M, Pon NG, Nikaido H, Hearst JE. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 16:45–55. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant RA, Filman DJ, Finkel SE, Kolter R, Hogle JM. 1998. The crystal structure of Dps, a ferritin homolog that binds and protects DNA. Nat Struct Biol 5:294–303. 10.1038/nsb0498-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilari A, Ceci P, Ferrari D, Rossi GL, Chiancone E. 2002. Iron incorporation into Escherichia coli Dps gives rise to a ferritin-like microcrystalline core. J Biol Chem 277:37619–37623. 10.1074/jbc.M206186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao G, Ceci P, Ilari A, Giangiacomo L, Laue TM, Chiancone E, Chasteen ND. 2002. Iron and hydrogen peroxide detoxification properties of DNA-binding protein from starved cells. A ferritin-like DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 277:27689–27696. 10.1074/jbc.M202094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews SC. 2010. The Ferritin-like superfamily: evolution of the biological iron storeman from a rubrerythrin-like ancestor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800:691–705. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khare G, Gupta V, Nangpal P, Gupta RK, Sauter NK, Tyagi AK. 2011. Ferritin structure from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: comparative study with homologues identifies extended C-terminus involved in ferroxidase activity. PLoS One 6:e18570. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellapadrona G, Stefanini S, Zamparelli C, Theil EC, Chiancone E. 2009. Iron translocation into and out of Listeria innocua Dps and size distribution of the protein-enclosed nanomineral are modulated by the electrostatic gradient at the 3-fold “ferritin-like” pores. J Biol Chem 284:19101–19109. 10.1074/jbc.M109.014670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stillman TJ, Upadhyay M, Norte VA, Sedelnikova SE, Carradus M, Tzokov S, Bullough PA, Shearman CA, Gasson MJ, Williams CH, Artymiuk PJ, Green J. 2005. The crystal structures of Lactococcus lactis MG1363 Dps proteins reveal the presence of an N-terminal helix that is required for DNA binding. Mol Microbiol 57:1101–1112. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frenkiel-Krispin D, Levin-Zaidman S, Shimoni E, Wolf SG, Wachtel EJ, Arad T, Finkel SE, Kolter R, Minsky A. 2001. Regulated phase transitions of bacterial chromatin: a non-enzymatic pathway for generic DNA protection. EMBO J 20:1184–1191. 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rycroft AN, Garside LH. 2000. Actinobacillus species and their role in animal disease. Vet J 159:18–36. 10.1053/tvjl.1999.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z, Zhou Y, Li L, Zhou R, Xiao S, Wan Y, Zhang S, Wang K, Li W, Li L, Jin H, Kang M, Dalai B, Li T, Liu L, Cheng Y, Zhang L, Xu T, Zheng H, Pu S, Wang B, Gu W, Zhang XL, Zhu GF, Wang S, Zhao GP, Chen H. 2008. Genome biology of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae JL03, an isolate of serotype 3 prevalent in China. PLoS One 3:e1450. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Zhu J, Yang K, Xu Z, Liu Z, Zhou R. 2014. Changes in gene expression of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in response to anaerobic stress reveal induction of central metabolism and biofilm formation. J Microbiol 52:473–481. 10.1007/s12275-014-3456-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheehan BJ, Langford PR, Rycroft AN, Kroll JS. 2000. [Cu, Zn]-Superoxide dismutase mutants of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae are unattenuated in infections of the natural host. Infect Immun 68:4778–4781. 10.1128/IAI.68.8.4778-4781.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan K, Liu T, Duan B, Liu F, Cao M, Peng W, Dai Q, Chen H, Yuan F, Bei W. 2020. The CpxAR two-component system contributes to growth, stress resistance, and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae by upregulating wecA transcription. Front Microbiol 11:1026. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Cao S, Zhang L, Yuan J, Zhao Q, Wen Y, Wu R, Huang X, Yan Q, Huang Y, Ma X, Han X, Miao C, Wen X. 2019. A requirement of TolC1 for effective survival, colonization and pathogenicity of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microb Pathog 134:103596. 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Cao S, Zhang L, Yuan J, Yang Y, Zhu Z, Wen Y, Wu R, Zhao Q, Huang X, Yan Q, Huang Y, Ma X, Wen X. 2017. TolC2 is required for the resistance, colonization and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J Med Microbiol 66:1170–1176. 10.1099/jmm.0.000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie F, Li G, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Liu S, Liu S, Wang C. 2016. The Lon protease homologue LonA, not LonC, contributes to the stress tolerance and biofilm formation of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microb Pathog 93:38–43. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Z, Zhao Q, Zhao Y, Zhang F, Wen X, Huang X, Wen Y, Wu R, Yan Q, Huang Y, Ma X, Han X, Cao S. 2017. Polyamine-binding protein PotD2 is required for stress tolerance and virulence in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110:1647–1657. 10.1007/s10482-017-0914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labrie J, Pelletier-Jacques G, Deslandes V, Ramjeet M, Auger E, Nash JH, Jacques M. 2010. Effects of growth conditions on biofilm formation by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vet Res 41:3. 10.1051/vetres/2009051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brentjens RJ, Ketterer M, Apicella MA, Spinola SM. 1996. Fine tangled pili expressed by Haemophilus ducreyi are a novel class of pili. J Bacteriol 178:808–816. 10.1128/jb.178.3.808-816.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellapadrona G, Ardini M, Ceci P, Stefanini S, Chiancone E. 2010. Dps proteins prevent Fenton-mediated oxidative damage by trapping hydroxyl radicals within the protein shell. Free Radic Biol Med 48:292–297. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan C, Xu Z, Zheng H, Liu W, Tang X, Shou J, Wu B, Wang S, Zhao GP, Chen H. 2011. Genome sequence of a porcine extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. J Bacteriol 193:5038. 10.1128/JB.05551-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González-Flecha B, Demple B. 1995. Metabolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in aerobically growing Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 270:13681–13687. 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S, You X, Imlay JA. 2005. Substantial DNA damage from submicromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide detected in Hpx- mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:9317–9322. 10.1073/pnas.0502051102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hitchings MD, Townsend P, Pohl E, Facey PD, Jones DH, Dyson PJ, Del Sol R. 2014. A tale of tails: deciphering the contribution of terminal tails to the biochemical properties of two Dps proteins from Streptomyces coelicolor. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:4911–4926. 10.1007/s00018-014-1658-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergé M, Mortier-Barrière I, Martin B, Claverys JP. 2003. Transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae relies on DprA- and RecA-dependent protection of incoming DNA single strands. Mol Microbiol 50:527–536. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide fluxes and compartmentalization inside growing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 183:7182–7189. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7182-7189.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flint DH, Smyk-Randall E, Tuminello JF, Draczynska-Lusiak B, Brown OR. 1993. The inactivation of dihydroxy-acid dehydratase in Escherichia coli treated with hyperbaric oxygen occurs because of the destruction of its Fe-S cluster, but the enzyme remains in the cell in a form that can be reactivated. J Biol Chem 268:25547–25552. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halsey TA, Vazquez-Torres A, Gravdahl DJ, Fang FC, Libby SJ. 2004. The ferritin-like Dps protein is required for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium oxidative stress resistance and virulence. Infect Immun 72:1155–1158. 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1155-1158.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olsen KN, Larsen MH, Gahan CGM, Kallipolitis B, Wolf XA, Rea R, Hill C, Ingmer H. 2005. The Dps-like protein Fri of Listeria monocytogenes promotes stress tolerance and intracellular multiplication in macrophage-like cells. Microbiology (Reading) 151:925–933. 10.1099/mic.0.27552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theoret JR, Cooper KK, Glock RD, Joens LA. 2011. A Campylobacter jejuni Dps homolog has a role in intracellular survival and in the development of campylobacterosis in neonate piglets. Foodborne Pathog Dis 8:1263–1268. 10.1089/fpd.2011.0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian X, Huang L, Wang M, Biville F, Zhu D, Jia R, Chen S, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, Zhang S, Huang J, Zhang L, Yu Y, Cheng A, Liu M. 2020. The functional identification of Dps in oxidative stress resistance and virulence of Riemerella anatipestifer CH-1 using a new unmarked gene deletion strategy. Vet Microbiol 247:108730. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altuvia S, Almirón M, Huisman G, Kolter R, Storz G. 1994. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and sigma S in stationary phase. Mol Microbiol 13:265–272. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buettner FF, Bendalla IM, Bossé JT, Meens J, Nash JH, Härtig E, Langford PR, Gerlach GF. 2009. Analysis of the Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae HlyX (FNR) regulon and identification of iron-regulated protein B as an essential virulence factor. Proteomics 9:2383–2398. 10.1002/pmic.200800439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ilari A, Stefanini S, Chiancone E, Tsernoglou D. 2000. The dodecameric ferritin from Listeria innocua contains a novel intersubunit iron-binding site. Nat Struct Biol 7:38–43. 10.1038/71236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kauko A, Pulliainen AT, Haataja S, Meyer-Klaucke W, Finne J, Papageorgiou AC. 2006. Iron incorporation in Streptococcus suis Dps-like peroxide resistance protein Dpr requires mobility in the ferroxidase center and leads to the formation of a ferrihydrite-like core. J Mol Biol 364:97–109. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ceci P, Cellai S, Falvo E, Rivetti C, Rossi GL, Chiancone E. 2004. DNA condensation and self-aggregation of Escherichia coli Dps are coupled phenomena related to the properties of the N-terminus. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5935–5944. 10.1093/nar/gkh915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haikarainen T, Papageorgiou AC. 2010. Dps-like proteins: structural and functional insights into a versatile protein family. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:341–351. 10.1007/s00018-009-0168-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Tawfiq JA, Bauer ME, Fortney KR, Katz BP, Hood AF, Ketterer M, Apicella MA, Spinola SM. 2000. A pilus-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is virulent in the human model of experimental infection. J Infect Dis 181:1176–1179. 10.1086/315310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou Y, Li L, Chen Z, Yuan H, Chen H, Zhou R. 2013. Adhesion protein ApfA of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is required for pathogenesis and is a potential target for vaccine development. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:287–294. 10.1128/CVI.00616-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boekema BK, Van Putten JP, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Smith HE. 2004. Host cell contact-induced transcription of the type IV fimbria gene cluster of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect Immun 72:691–700. 10.1128/IAI.72.2.691-700.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li T, Zhang Q, Wang R, Zhang S, Pei J, Li Y, Li L, Zhou R. 2019. The roles of flp1 and tadD in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae pilus biosynthesis and pathogenicity. Microb Pathog 126:310–317. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu J, Hu L, Xu Z, Tan C, Yuan F, Fu S, Cheng H, Chen H, Bei W. 2015. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae two-component system QseB/QseC regulates the transcription of PilM, an important determinant of bacterial adherence and virulence. Vet Microbiol 177:184–192. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roland K, Curtiss R, 3rd, Sizemore D. 1999. Construction and evaluation of a delta cya delta crp Salmonella typhimurium strain expressing avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 LPS as a vaccine to prevent airsacculitis in chickens. Avian Dis 43:429–441. 10.2307/1592640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oswald W, Tonpitak W, Ohrt G, Gerlach G. 1999. A single-step transconjugation system for the introduction of unmarked deletions into Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 7 using a sucrose sensitivity marker. FEMS Microbiol Lett 179:153–160. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards RA, Keller LH, Schifferli DM. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149–157. 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frey J. 1992. Construction of a broad host range shuttle vector for gene cloning and expression in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and other Pasteurellaceae. Res Microbiol 143:263–269. 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90018-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1; Fig. S1 to S7. Download jb.00326-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.9 MB (928.7KB, pdf)