ABSTRACT

Reductive dehalogenases (RDases) are a family of redox enzymes that are required for anaerobic organohalide respiration, a microbial process that is useful in bioremediation. Structural and mechanistic studies of these enzymes have been greatly impeded due to challenges in RDase heterologous expression, potentially because of their cobamide-dependence. There have been a few successful attempts at RDase production in unconventional heterologous hosts, but a robust method has yet to be developed. Here we outline a novel respiratory RDase expression system using Escherichia coli. The overexpression of E. coli’s cobamide transport system, btu, and anaerobic expression conditions were found to be essential for production of active RDases from Dehalobacter—an obligate organohalide respiring bacterium. The expression system was validated on six enzymes with amino acid sequence identities as low as 28%. Dehalogenation activity was verified for each RDase by assaying cell extracts of small-scale expression cultures on various chlorinated substrates including chloroalkanes, chloroethenes, and hexachlorocyclohexanes. Two RDases, TmrA from Dehalobacter sp. UNSWDHB and HchA from Dehalobacter sp. HCH1, were purified by nickel affinity chromatography. Incorporation of the cobamide and iron-sulfur cluster cofactors was verified; however, the precise cobalamin incorporation could not be determined due to variance between methodologies, and the specific activity of TmrA was consistent with that of the native enzyme. The heterologous expression of respiratory RDases, particularly from obligate organohalide respiring bacteria, has been extremely challenging and unreliable. Here we present a relatively straightforward E. coli expression system that has performed well for a variety of Dehalobacter spp. RDases.

IMPORTANCE Understanding microbial reductive dehalogenation is important to refine the global halogen cycle and to improve bioremediation of halogenated contaminants; however, studies of the family of enzymes responsible are limited. Characterization of reductive dehalogenase enzymes has largely eluded researchers due to the lack of a reliable and high-yielding production method. We are presenting an approach to express reductive dehalogenase enzymes from Dehalobacter, a key group of organisms used in bioremediation, in Escherichia coli. This expression system will propel the study of reductive dehalogenases by facilitating their production and isolation, allowing researchers to pursue more in-depth questions about the activity and structure of these enzymes. This platform will also provide a starting point to improve the expression of reductive dehalogenases from many other organisms.

KEYWORDS: reductive dehalogenases, heterologous expression, Dehalobacter, cobalamin, Escherichia coli, enzyme purification, iron-sulfur clusters, anaerobic

INTRODUCTION

A wide array of naturally produced halogenated organic compounds, or organohalides, are present in the environment. Organohalides also make up some of the most pervasive and concerning anthropogenic soil, sediment, and groundwater contaminants. Anaerobic organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB) can readily transform a number of these pollutants, such as chlorinated ethenes and ethanes, by using them as terminal electron acceptors in their cellular respiration (1, 2). The respiration process removes halogen atoms from organohalide substrates via reductive dehalogenation, changing the properties of the parent substrate, often detoxifying or transforming them to more degradable substrates for other organisms. OHRB were first described in 1990 (1), and quite rapidly became a staple tool in commercial bioremediation. In particular, obligate OHRB Dehalococcoides and Dehalobacter are highly abundant in bioremediation cultures targeting chlorinated contaminants (3, 4). Obligate OHRB have very restricted metabolism and can only grow on organohalide substrates while facultative OHRB are flexible and can utilize a variety of electron acceptors (2). All OHRB use reductive dehalogenase enzymes (RDase) discovered in 1995 as part of their electron transport chain to perform these reduction reactions (5). RDases are key targets for studying the mechanism of OHRB respiration and remediation, and on their own RDases offer an intriguing tool for industrial applications.

RDases form a large family of oxygen-sensitive enzymes that rely on two iron-sulfur clusters [4Fe-4S] and a cobamide, commonly cobalamin or vitamin B12, as cofactors to perform catalysis; RDases are well described in previous reviews (2, 6). There are two broad categories: respiratory RDases from OHRB, and catabolic RDases which are catalytically similar but perform a different cellular function (7, 8). Here we will focus on respiratory RDases as they represent an unusual metabolism and are more relevant to bioremediation. All RDases remove halogen atoms from their substrate through either a hydrogenolysis reaction, where one halogen is substituted with a hydrogen, or a reductive β-elimination reaction, involving the loss of two halogen substituents from adjacent carbon atoms (6). Respiratory RDases also hold a twin arginine translocation (TAT) signal peptide to localize them to the periplasmic membrane, though these are cleaved off in the mature protein. While the RDase family has wide sequence variation, many of the described RDases are from Dehalococcoides and Dehalobacter and use chloroethenes, chloroethanes, or chlorobenzenes as substrates. Furthermore, obligate OHRB encode dozens of unique rdhA genes (RDase homologous genes) in their genomes (9); although, a majority are not expressed in culture and have unknown functions. Approximately 25 unique RDases have had their substrates experimentally determined (see Table S1 for details), yet there are almost 1,000 unstudied rdhA sequences in the Reductive Dehalogenase Database (9), and many more in metagenomic surveys such as the ones described in (10, 11). The number of identified rdhA sequences continues to climb with more sequencing, yet functional characterization methods lag far behind.

The majority of the functionally characterized RDases were purified from their endogenous (or native) producers (Table S1) through extensive methods (5, 12–23). Obtaining enough biomass for such purifications is not a trivial undertaking and the purification methods under anaerobic conditions are tedious. Because most OHRB are difficult to grow as they require toxic, poorly soluble, and often volatile halogenated substrates, small scale partial purification using blue native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) coupled with activity assays and proteomic analysis has proven very useful for ascribing substrates to specific RDases (24–29). All of the above characterization studies are confined both to lab-cultivatable organisms and to actively expressed genes. Table S1 and Text S1 provides a list of currently known RDases.

To address the limitations of purifying RDases from native producers, many research groups have attempted heterologous expression, but the complex cofactor requirements, which are crucial for RDase activity, have hindered efforts. We compiled a list of all expression studies (Table S2 and Text S1). The first published expression attempt was in 1998, where PceA from Sulfurospirillum multivorans was expressed in Escherichia coli but no activity was detected (30). Subsequent trials in E. coli involved denaturation and cofactor reconstitution (31, 32). It was not until 2014 when the first activity from heterologously expressed RDases were from the cobamide-producing host Shimwellia blattae; however, these enzymes were unable to be purified using a Strep affinity tag (33). Finally, 20 years after their discovery, the first RDase crystal structures were solved: one of PceA from S. multivorans, obtained from the native producer with a mutation to incorporate an affinity tag (34), and the catabolic RDase NpRdhA from Nitratireductor pacificus pht-3B, expressed in the cobalamin producing Bacillus megaterium (8). The two crystal structures confirmed that the cobamide cofactor is deeply buried within the enzyme and makes numerous interactions with the peptide sidechains suggesting that it may serve a structural role for proper enzyme folding (8, 34). Most typical heterologous hosts, such as E. coli, neither produce cobamides de novo nor import the molecule under basal conditions. Since the crystal structures, there have been a couple successful reports of catalytically active RDase expression all using hosts S. blattae and B. megaterium, both with full cobamide biosynthetic pathways (35, 36). However, less conventional hosts tend to have lower protein yields and have less standardized protocols. The preferable host would be E. coli as it grows quickly, is highly engineered to obtain high protein yield, and is amenable to modern molecular biology tools. Thus, far, expression attempts using E. coli have required enzyme denaturation and refolding for cofactor reconstitution to obtain activity (32, 37, 38), but these methods are too unpredictable and unreproducible to be used as a standard expression system. Although developing a generalizable RDase expression system has been a goal in the field for decades, to date, no respiratory RDase has been directly produced from E. coli in its active state.

Although E. coli does not synthesize cobalamin de novo, it, like many other organisms, possesses the vitamin B12 salvage pathway (btu) to take up cobalamin from the environment (39). This salvage pathway consists of a series of transport proteins: BtuB, a TonB-dependent transporter protein on the outer membrane to import cobalamin into the periplasm; BtuF, a periplasmic protein that will bind free cobalamin; BtuCD, an ABC-transporter that associates with BtuF to import cobalamin into the cytoplasm, a cartoon representation can be found in Fig. 1B (40–46). The gene btuE is also present in the btu operon but is not required for vitamin B12 transport (47). Expression of the btu operon is poor under typical growth conditions but can be enhanced with the use of ethanolamine-based media, which forces E. coli to use a cobalamin-dependent enzyme, or by induced expression (44, 48). Recently, the Booker lab developed an expression system for cobalamin-dependent S-adenosylmethionine methylases that expressed the entire btu operon from E. coli under arabinose induction in the vector pBAD42-BtuCEDFB (44). The application of this vector greatly enhanced the solubility and activity of several methylases tested (44). Similarly, the catabolic RDase, NpRdhA, had a slight increase in yield and cofactor incorporation when co-expressed with just BtuB (49). Given the success of these expression systems and the hypothesis that the cobamide cofactor supports proper RDase folding, we predicted that implementation of btu expression could result in generation of active RDases in E. coli.

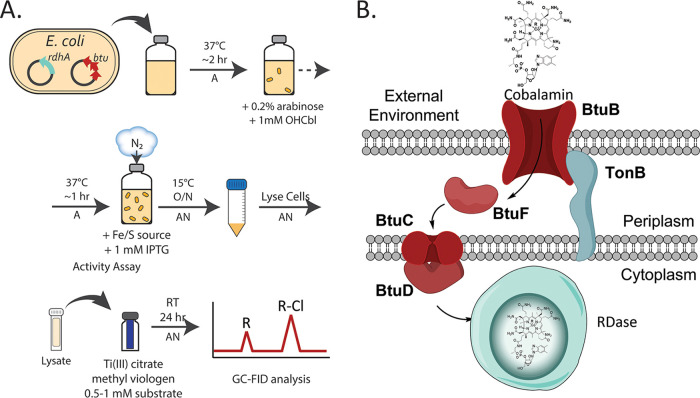

FIG 1.

(A) Schematic of the RDase expression system and small-scale expression tests to determine production of the active RDases. (B) Cartoon of the Btu pathway used for cobalamin incorporation in RDase expression (adapted from reference 44 with permission [copyright 2018 American Chemical Society]). A, aerobic conditions; AN, anaerobic conditions; O/N, overnight; GC-FID, gas chromatography with flame ionization detection.

In this work, we employ the pBAD42-BtuCEDFB, provided by the Booker lab, in several strains of E. coli with increased expression of the isc and/or suf operons to enhance their iron-sulfur cluster production and maintenance (50, 51), for the heterologous expression of several respiratory RDases from Dehalobacter spp. This expression system is a tremendous steppingstone to advance knowledge about the RDase enzyme family and organohalide respiration, and to facilitate future development in bioremediation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Developing the expression system in E. coli.

The expression system was developed using TmrA, a chloroalkane-reducing RDase from Dehalobacter sp. UNSWDHB. It was chosen because it was previously expressed in its active form in B. megaterium (35). TmrA was cloned without its TAT signal peptide into the p15TV-L expression vector. This construct expressed TmrA with an N-terminal x6His tag under IPTG control. The expression vector was introduced into E. coli ΔiscR, a strain engineered for enhanced [4Fe-4S] production by deleting the iron-sulfur cluster (isc) operon repressor (50, 52). Small-scale expression cultures were used to test TmrA production in a variety of conditions; a schematic of the final protocol is shown in Fig. 1. To establish necessary conditions for successful expression, TmrA was initially tested with and without pBAD42-BtuCEDFB for btu operon co-expression (44), and in the presence and absence of oxygen during induction. While TmrA expression was evident by SDS-PAGE in all conditions (Fig. S1 and Text S3), its solubility in each case was difficult to distinguish as very little enzyme was visible and overlapped with the host’s proteins. For this reason, an activity assay, specifically the level of chloroform (CF) reduction observed from soluble lysate fraction, was used to indicate the production of active TmrA under each set of conditions relative to each other. All assays were performed under anaerobic conditions using titanium(III) citrate as the reductant, and methyl viologen as the electron donor. The assay results were measured by endpoint detection after 18 h to 24 h using GC-FID to quantify the substrate and product(s) (see Materials and Methods). We found that the co-expression of the btu operon paired with TmrA induction under anaerobic conditions was essential to produce active TmrA in E. coli (Fig. 2A). Under these two conditions 76 ± 4 nmol of dichloromethane (DCM) was produced (significantly higher than the limit of detection of 5 nmol for DCM on this instrument), whereas with no btu co-expression or in the presence of oxygen, no DCM was detected.

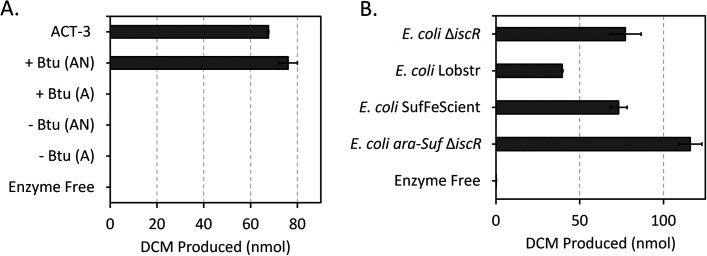

FIG 2.

Reduction of chloroform to dichloromethane (DCM) by E. coli cell extracts expressing TmrA over a period of 24 h. (A) Comparison of TmrA expressed in E. coli ΔiscR with (+Btu) and without (–Btu) pBAD42-BtuCEDFB plasmid expression, and with induction under anaerobic (AN) or aerobic (A) conditions. (B) Comparison of TmrA expressed in different E. coli strains with pBAD42-BtuCEDFB co-expression and under anaerobic conditions. ACT-3 mixed culture cell extract was used as a positive control and an enzyme free negative control was used. Error bars are standard deviation between replicates (n = 6, except for ACT-3, enzyme free, and aerobic samples where n = 3).

A variety of additional conditions were tested to see if the observed activity could be enhanced, these included: varying lysis buffer detergent, inclusion of the TAT signal peptide, and testing different E. coli strains. The detergents tested were 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% CHAPS, and 1% digitonin; there was only a minor difference in DCM production (nmol) between these detergents (82 ± 1, Triton X-100; 76 ± 2, digitonin; 67.9 ± 0.3, CHAPS), so all subsequent experiments were continued with Triton X-100. However, this flexibility may not be true for all RDases as some Dehalococcoides RDases were shown to be inhibited by certain detergents (53). The inclusion of the TAT sequence when expressing TmrA also did not have a noticeable effect on the enzyme activity in the soluble lysate fraction; although, it could interfere with downstream applications, so we chose to use the truncated TmrA. Finally, we tested three different strains of E. coli that have enhanced [4Fe-4S] production: E. coli ΔiscR (50, 52), E. coli SufFeScient (51), and E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR, as well as one typical expression strain, E. coli BL21(DE3) Lobstr. Lysates from E. coli ΔiscR and SufFeScient had similar levels of CF reduction, whereas there was a 30% increase in activity observed from TmrA expressed in E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR (Fig. 2B). All the [4Fe-4S] strains displayed at least double the activity as the typical strain E. coli Lobstr. E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR was subsequently used as the primary expression strain, unless the RDase of interest displayed poor expression in this strain, in which case E. coli ΔiscR was used.

The implementation of the pBAD42-BtuCEDFB plasmid to increase the uptake of cobalamin was key and essential to successful expression. This data confirms that a cobamide co-factor is critical to protein folding and activity in RDases as has been alluded to from previous expression attempts (32, 33, 35, 37, 49). The requirement of a cobamide during protein expression, in previous studies and this work, and its buried position within the known crystal structures suggests that the cobamide is needed for the enzyme to fold into its catalytically active form. Induction under anaerobic conditions was also necessary, most likely to prevent oxidative damage to the [4Fe-4S] clusters, but perhaps the addition of a strong reductant into the medium could allow for aerobic induction. The use of E. coli strains with increased [4Fe-4S] cluster production or stability also improved the level of activity seen in the lysates compared to conventional strains (Fig. 2B). These clusters are essential for electron transport within the enzyme. The specific strain of E. coli used for [4Fe-4S] production may depend on the desired RDase as the expression levels of some enzymes varied depending on the strain. Overall, this expression system successfully reached the goal of producing active respiratory RDases in E. coli. Furthermore, this expression system was successful on an RDase from the obligate OHRB Dehalobacter and may be particularly useful for studying the organohalide respiration process.

The only other account of E. coli being used for the production of a functional RDase, without cofactor reconstitution, was the expression of NpRdhA (49). Similarly, the authors improved cobalamin transport to support expression and cofactor incorporation (49). However, NpRdhA, being a nonrespiratory metabolic (i.e., not membrane associated) RDase which acts on relatively soluble halogenated phenols and hydroxybenzoic acids, is itself more soluble and more oxygen tolerant than respiratory RDases. NpRdhA was expressed in a conventional E. coli strain both with and without the co-expression of BtuB from the btu operon (49). The addition of the BtuB co-expression increased the cobalamin occupancy by 9% and doubled the enzyme yield (49), but was not a determining factor in the production of active protein, contrary to what we observe from the respiratory RDases. NpRdhA is not a suitable comparator for the systems presented here.

Comparing heterologous RDase substrate specificity.

We applied the optimized expression system to a series of other enzymes to validate its reproducibility. CfrA and DcrA, chloroethane reductases from Dehalobacter sp. CF and DCA, respectively, in the ACT-3 mixed culture (see Materials and Methods for a description of the culture), were chosen to be tested as they have >95% amino acid sequence identity to TmrA but have displayed differing substrate preferences when isolated and tested from their native producers (14, 27). CfrA was experimentally shown to reduce CF and 1,1,1-trichloroethane (1,1,1-TCA) but not 1,1-dichloroethane (1,1-DCA); DcrA accepts 1,1-DCA as a substrate, but not 1,1,1-TCA or CF; and TmrA accepts all three substrates (14, 27). As well, 1,1,2-trichloroethane (1,1,2-TCA) is a substrate for all three enzymes, although the products of reaction vary as 1,1,2-TCA can undergo both dihaloelimination or hydrogenolysis (14, 54). DcrA has not been explicitly assayed against 1,1,2-TCA, but the organism that it comes from can use 1,1,2-TCA as an electron acceptor so it has assumed activity on this substrate (54). The known distinction between these enzymes’ substrate ranges made them good subjects to confirm that the expressed enzymes exhibit the same specificity. Both CfrA and DcrA were successfully expressed in small-scale cultures and the resulting cell lysates displayed activity on their expected substrates.

TmrA, CfrA, and DcrA were all assayed against several chloroalkanes: CF, 1,1,1-TCA, 1,1,2-TCA, and 1,1-DCA. The amount (nmol) of each dechlorinated product produced in the assays are given in Table 1, some substrates yielded multiple products depending on the reaction pathway. Heat deactivated controls were used for each substrate, none of which showed notable reduction of the substrate except 1,1,1-TCA to 1,1-DCE though this transformation was also seen in the enzyme free control (Table S7). While the specific activity of each enzyme cannot be compared from the lysate assays, as the amount of RDase is unknown, their substrate preferences and products can be compared. TmrA and CfrA both reduced CF, 1,1,1-TCA, and 1,1,2-TCA via hydrogenolysis; although, TmrA transformed a considerable amount of 1,1,2-TCA into the β-elimination product, vinyl chloride (VC), while CfrA only produced a minute amount of VC. TmrA was also able to reduce 1,1-DCA to chloroethane (CA) while CfrA had negligible activity on this substrate consistent with previous studies (27). In contrast, DcrA reduced 1,1-DCA, but was not active on CF and barely on 1,1,1-TCA (Table 1), also consistent with previous studies (27). The one surprising result was the high production of 1,1-DCE from 1,1,1-TCA as this is only a minor by-product in the cultures and is mainly thought of as an abiotic reaction (55). Because 1,1-DCE is also seen in the negative controls, we anticipate it to be an abiotic reaction accelerated by a component of the buffer. The observed substrate selectivity, particularly those of CfrA and DcrA, act as validation that the heterologously expressed enzymes behave similarly to those partially purified and characterized from the native organisms.

TABLE 1.

Reduction of chlorinate substrates over 24 h by the cell extracts of E. coli expressing TmrA, CfrA, and DcrAe

| Amt produced (nmol) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substratef | Product(s) | Enzyme-free | TmrA | CfrA | DcrA |

| CF | DCM | n.d.a | 101 ± 7b | 90 ± 10b | n.d.a |

| 1,1,1-TCA | 1,1-DCA | 0.09 ± 0.06 a | 7 ± 3b | 13 ± 1b | 0.20 ± 0.02a |

| 1,1-DCEd | 1.3 ± 0.3 a | 12.4 ± 0.8b | 11.7 ± 0.2 b | 12.1 ± 0.1 a | |

| 1,1,2-TCA | 1,2-DCA | n.d.a | 38 ± 6c | 35 ± 5c | n.d.a |

| VCd | n.d.a | 11 ± 2c | 0.4 ± 0.2c | 1.0 ± 0.2a | |

| 1,1-DCA | CA | n.d.a | 9 ± 5c | 0.07 ± 0.05c | 13 ± 4b |

| VCd | n.d.a | n.d.c | n.d.c | 0.04 ± 0.03b | |

n = 2.

n = 6.

n = 4.

β-elimination pathway.

All assays were done with approximately 4 to 10 μg of total protein. Error is the standard deviation between replicates, number of replicates are indicated for each sample. CF, chloroform; DCM, dichloromethane; TCA, trichloroethane; DCA, dichloroethane; VC, vinyl chloride; CA, chloroethane; n.d., not detected.

Known substrates for TmrA are CF, 1,1,1-TCA, 1,1,2-TCA, and 1,1-DCA; known substrates for CfrA are CF, 1,1,1-TCA, and 1,1,2-TCA; known substrates for DcrA are 1,1-DCA and 1,1,2-TCA.

The successful expression of CfrA and DcrA was expected after optimizing the system on TmrA because the enzyme sequences are almost identical to each other and are thus likely to behave similarly. While these three enzymes have been previously studied, it was still intriguing to remove any other biological factors from the native organisms and confirm their unique substrate preferences in a heterologous system. In agreement with the literature, CfrA was much more efficient at reducing trichloroalkanes, whereas DcrA can almost exclusively reduce 1,1-DCA (27). TmrA displays activity against all the chloroalkanes assayed, and reduced 1,1,2-TCA to both 1,2-DCA and VC. The observed activity differences by each of these enzymes confirms that it is their amino acid sequence that affects their activity and not external factors such as the type of cobamide, protein-protein interactions, or other cellular components.

TmrA purification and specific activity.

TmrA was elected for large scale purification trials because TmrA has published activity and expression data to compare against. TmrA was semi-purified from a 1 L expression culture using nickel affinity chromatography. An SDS-PAGE of the TmrA purification is shown in Fig. S2A and Text S3. The concentrated protein sample was a yellow-brown color indicating the presence of [4Fe-4S] clusters. TmrA was purified to an approximate purity of 50%, 2.2 ± 0.2 mg of protein was obtained from about 7.5 g wet cell mass. For details about the purification and purity estimation see Fig. S2B and Table S5 of Text S3. To further assess the quality of the purification, the cofactors were extracted and quantified to measure their occupancy ratio. RDases are expected to have eight iron atoms from two [4Fe-4S] clusters. After adjusting for purity (i.e., assume the cofactors were only coming from TmrA), TmrA was found to have 6.2 ± 0.6 mol iron per mol enzyme. The cobalamin occupancy was measured by two methods; the first was extracted into water and measured by absorbance at 367 nm, characteristic of dicyanocobalamin. Using this method and correcting for purity, TmrA was estimated to have cobalamin occupancies of 62% ± 13% for TmrA. However, using the second method which involved extraction into acidified methanol and quantification by UHPLC-MS and correcting for purity (see Materials and Methods), the enzymes occupancies were measured to be 24% ± 2%. Finally, we found that TmrA was able to withstand freeze-thaw cycles without loss of activity and was able to retain all activity after being exposed to O2 for 3 h with 1 mM TCEP in the buffer (longer periods have not been tested; data not shown).

The specific activity of TmrA was determined for several substrates; specific activity was reported in nkat (nmol product/s) per mg protein. TmrA activity was measured for all of its known substrates that showed activity in the lysate assays. Assays with the purified enzyme also identified other transformations that were not observed in lysate, such as 1,2-DCA to CA and VC, as well as 1,1-DCA to VC. TmrA had the highest specific activity toward CF and 1,1,2-TCA into both 1,2-DCA and VC, whereas it had low specific activity toward 1,1,1-TCA and the less chlorinated substrates 1,1-DCA and 1,2-DCA (Fig. 3). When concentrated, TmrA was observed to reduce the dichloroethanes and perform both hydrogenolysis and β-elimination reactions on all chloroethane substrates. The reduction of 1,1,1-TCA to 1,1-DCE is not shown as there were similar concentrations in the enzyme-free negative controls so the biotic activity could not be distinguished (Table S10). There was also production of 1,1-DCE in the lysate samples, although the production from the enzymes was 10-fold higher than the enzyme-free control. In the purified protein case, the production levels were equivalent to the negative control which highly suggests it is not a biotic reaction.

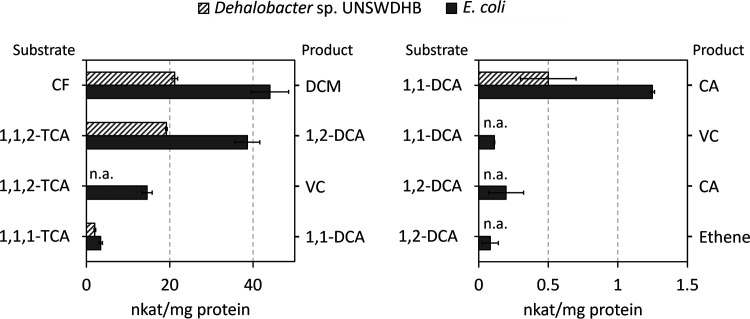

FIG 3.

Specific activity of TmrA for substrate-product transformations, where nkat is defined as the rate of product formation in nmol/s. Data for TmrA purified from the endogenous host Dehalobacter sp. UNSWDHB (striped bars) (14), and TmrA heterologously expressed and purified from E. coli (solid bars) are shown. Substrates are indicated on the left axis label and product is indicated on the right axis label. Error bars are from reported standard deviation for the literature values, and the standard deviation of purified enzyme assays (n = 3). n.a., not available.

Not only did the substrate profiles match the literature, the purified TmrA had a specific activity that corresponded well to the native enzyme purified from Dehalobacter sp. UNSWDHB. The native enzyme was found to be most active on CF and 1,1,2-TCA, and its specific activity toward its substrates was within the same magnitude of the heterologously expressed TmrA (Fig. 3). This consistency between the enzymes confirms that the heterologous system is representative of the native enzymes.

The use of E. coli as the heterologous host has several advantages over the hosts previously used for respiratory RDases, namely, S. blattae and B. megaterium. One advantage is higher protein yields in E. coli. From 1 L of culture, we were able to obtain approximately 2 mg of TmrA whereas to get 0.9 mg of TmrA at a similar purity, 15 L of B. megaterium was required (35). Furthermore, the RDase expression vectors can be commercially produced in typical pET vectors while those for B. megaterium and S. blattae generally have to be manually cloned (33, 35, 36). The cofactor occupancy of the RDases from this E. coli expression system are also comparable with other heterologous hosts. The molar ratio of iron to enzyme was reported to be 7.26 ± 0.48 mol iron/mol TmrA produced in B. megaterium and we measured 6.2 ± 0.6 mol iron/mol TmrA from our system (35). TmrA from B. megaterium was calculated to have 52% ± 3% cobalamin occupancy (35), using a similar absorbance based method we measured an occupancy of 62% ± 13%. Although, the variation in cobalamin occupancy measured between the two methods used in this study suggests that the true occupancy is within 20–60%. Our system seems to perform similarly to those using alternative heterologous hosts, is reproducible, and facilitates high-throughput protein production.

Expression and purification of a lindane reductase.

HchA, identified from Dehalobacter sp. HCH1 as a lindane or γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) reductase (56), was chosen to test the generalizability of the expression system because it has low amino acid sequence identity (32.8%) to TmrA. This enzyme was recently identified using BN-PAGE in enrichment cultures that dechlorinate HCH via three sequential dechlorination steps to form monochlorobenzene (MCB) and benzene (56, 57). HchA was successfully expressed and was assayed on several of the chlorinated solvents as well as on two isomers of HCH (γ-HCH and α-HCH).

HchA produced primarily monochlorobenzene (MCB) from its known substrate γ-HCH (Table 2). Interestingly, it transformed more of the α-HCH isomer and to a higher proportion of benzene. However, there was significant reduction of both isomers by the HchA heat-killed controls and by free cobalamin (Table 2), so the biotic activity needed to be further confirmed (see below). HchA was also able to take 1,1,2-TCA as a substrate and transform it to VC to a greater extent than the cobalamin negative control. Some highly chlorinated substrates, such as γ-HCH and 1,1,2-TCA, are more susceptible to abiotic reduction, whereas others including CF are much more resistant to reduction. HchA readily dechlorinated these permissive substrates and primarily seems to catalyze dihaloelimination reactions.

TABLE 2.

Reduction of chlorinated substrates over 24 h by the cell extracts of E. coli expressing HchA and the relevant negative controlse

| Substrate | Product(s) | Amt produced (nmol) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HchA | Heat killed HchA | Cobalamin | Catalyst free | ||

| CF | DCM | n.d.a | n.t. | n.t. | n.d.a |

| 1,1,2-TCA | 1,2-DCA | n.d.a | n.t. | n.d. | n.d.a |

| VCd | 18 ± 6a | n.t. | 9.5 | n.d.a | |

| 1,1-DCA | CA | n.d.a | n.t. | n.t. | n.d.a |

| γ-HCH | MCB | 7 ± 1b | 7.3 ± 0.7c | 9 ± 2 a | 0.4 ± 0.1c |

| Benzene | 0.07 ± 0.07b | 0.12 ± 0.07c | 0.21 ± 0.04 a | 0.07 ± 0.05c | |

| α-HCH | MCB | 18 ± 1a | n.t. | 5.1 | 0.58 |

| Benzene | 0.6 ± 0.1a | n.t. | 0.15 | n.d. | |

n = 2.

n = 6.

n = 3.

Dihaloelimination pathway.

All assays were done with approximately 4 to 10 μg of total protein, or 100 nmol of hydroxycobalamin. Error is standard deviation of replicates; number of replicates is indicated for each sample. CF, chloroform; DCM, dichloromethane; TCA, trichloroethane; DCA, dichloroethane; VC, vinyl chloride; CA, chloroethane; MCB, monochlorobenzene; n.d., not detected; n.t., not tested.

To probe relative importance of biotic and abiotic reduction of γ-HCH, HchA was scaled up and purified using the same methods as for TmrA. HchA was enriched to approximately 40% purity and 2.7 ± 0.4 mg of protein was obtained from about 7 g wet cell mass. For details about the purification see Fig. S3 and Table S5 and Text S3. The cofactors were also quantified to estimate their occupancy. HchA was found to have 6.4 ± 0.8 mol iron per mol enzyme, a cobalamin occupancy of 76% ± 14% using the UV-Vis method, and a cobalamin occupancy of 22.1 ± 0.7% using the LC-MS method. These numbers are consistent with what was observed for TmrA. HchA was also found to be tolerant of freeze-thaw cycles and retained all activity after 30 min of O2 exposure (with 1 mM TCEP), but only held 60% ± 35% of its activity after 1 h of exposure (data not shown).

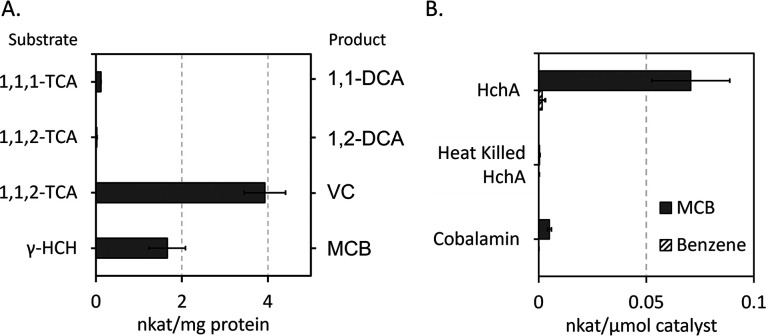

HchA specific activity was measured on γ-HCH, 1,1,2-TCA, and 1,1,1-TCA. HchA had the highest level of activity transforming 1,1,2-TCA to VC, whereas it showed minor transformation of 1,1,2-TCA to 1,2-DCA (0.02 ± 0.01 nkat/mg) and 1,1,1-TCA to 1,1-DCA (0.11 ± 0.01 nkat/mg; Fig. 4A). The activity on its primary substrate γ-HCH to MCB was 1.7 ± 0.4 nkat/mg, the transformation to benzene was not shown as it was also produced in the negative controls. Since the reduction of γ-HCH can also occur abiotically by free cobalamin, the rate of reduction was compared when normalized by mol of catalyst (i.e., HchA and cobalamin). HchA was approximately 14 times faster than the abiotic reaction (Fig. 4B). Further, the killed control of HchA no longer had significant activity indicating that the activity seen in the lysates was most likely due to free cobalamin and longer incubation periods. These results suggests that though γ-HCH is reduced by free cobalamin, the enzyme is clearly more effective.

FIG 4.

(A) Specific activity of HchA for substrate-product transformations. (B) The rate of monochlorobenzene (MCB) and benzene production from purified HchA, heat killed HchA, and free cobalamin (same molarity of catalysts were used). The nkat is defined as the rate of product formation in nmol/s, this rate is normalized to mols of catalyst. Error bars are the standard deviation between assays (n = 3).

Further, HchA displayed activity that was not tested previously, most likely due to the limited enzyme available from BN-PAGE separation. HchA was only ever documented to reduce γ-HCH though it seems to be more effective at transforming the alpha isomer and the permissive substrate, 1,1,2-TCA. These reactions seen by HchA in the lysates are all expected to be dihaloelimination reactions, but when HchA was concentrated after enrichment it was also observed to have slight hydrogenolysis activity against the 1,1,1-TCA. TmrA was tested against γ-HCH as well but did not catalyze any meaningful transformations (data not shown), suggesting that HchA has some specialization for HCH. HchA poses an interesting comparison to other RDases that predominantly undergo hydrogenolysis reactions to understand how the enzymes distinguish between reaction pathways.

Expression of putative rdhA genes.

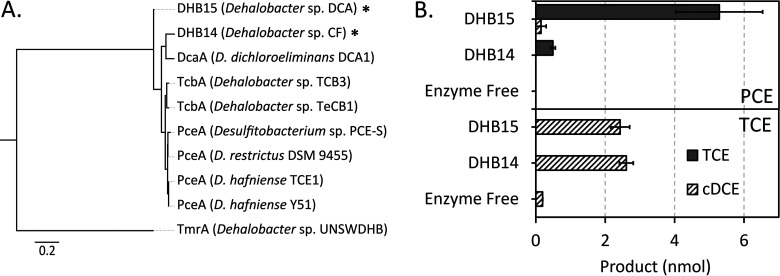

To further test the application of the expression system, we expressed two putative RdhAs, DHB14 and DHB15, that had been previously cloned from the genomic DNA of Dehalobacter sp. strains CF and DCA, respectively. These enzymes cluster to a group of Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium RDases including several PceA and TcbA enzymes (Fig. 5A), which accept unsaturated and aromatic substrates (29, 31, 58). Based on the similarities to known chloroethene reductases, DHB14 and DHB15 were expressed, the cell lysates were assayed against perchloroethene (PCE) and trichloroethene (TCE), and the presence of dechlorinated products was analyzed (Fig. 5B). DHB15 reduced PCE to TCE and a small amount of cis-dichloroethene (cDCE), DHB14 only reduced a minor amount of PCE to TCE. Both enzymes reduced a modest amount of TCE to cDCE. The enzymes were also tested for activity on 1,2-DCA; however, no product was detected after 24 h of incubation. The activity of these two enzymes demonstrate that this expression system has potential to functionally characterize the numerous rdhA genes encoded in Dehalobacter spp. genomes.

FIG 5.

(A) Maximum-likelihood (ML) tree of DHB14 and DHB15 RdhA amino acid sequences (indicated by *) to show relation to the closest characterized RDases in comparison to TmrA. (B) Reduction of either PCE (top) or TCE (bottom) by DHB14 and DHB15 in E. coli cell extract, assay was done over 24 h. Error bars are the standard deviation between replicates (n = 4), except negative controls (n = 2). An amino acid alignment was built using the Geneious v8.1.9 MUSCLE plugin, and the ML tree was constructed using RAxML v8.2.12 Gamma GTR protein method with 100 bootstraps, the highest scoring tree was selected. Scale indicates average number of substitutions per amino acid site. Protein accession numbers for sequences in panel A in descending order are as follows: DHB15, AFV02698; DHB14, AFV05674; DcaA, CAJ75430; TcbA, 2821531494 (IMG ID); TcbA, WP_068882928; PceA, AAO60101; PceA, AHF10727; PceA, CAD28792; PceA, WP_011460641; TmrA, WP_034377773.

Dehalococcoides RDase expression attempts.

The heterologous expression of several RDases from Dehalococcoides spp. was attempted using this expression system. Three characterized chloroethene reductases were cloned and expressed: VcrA from D. mccartyi VC, BvcA from D. mccartyi BAV1, and TceA from D. mccartyi 195. Expression of these enzymes was apparent by SDS-PAGE; however, no activity was ever detected from the expression culture lysates. The primers and plasmids used for cloning these RDases can be found in Tables S3 and S4 and Text S2, and details of all conditions tested for the expression of these RDases can be found in the Text S4.

The inability to achieve activity from the Dehalococcoides spp. enzymes could be due to the absence of an unknown component required for folding such as an organism-specific chaperone protein. Further work is needed to test more expression conditions for RDases from the Chloroflexi Dehalococcoides and Dehalogenimonas to identify the essential factors in their production. Nevertheless, the system we have presented provides an excellent starting point for future efforts.

Significance and future work.

Developing a heterologous system for RDase expression in E. coli has been a goal of the dehalogenation community for the past several decades. Here we have presented a solution for the expression of Dehalobacter derived RDases that will allow high yield expression and purification, enabling future structural and mechanistic studies. We demonstrated that this system was able to be applied to various RDases from Dehalobacter having as little as 28% amino acid sequence identity to each other. Given the high similarity between Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium RDases, we predict that this system would perform similarly for RDases from other Firmicutes.

We anticipate that this expression system will expedite the characterization of the RDase enzyme family and advance the future of enzyme-driven bioremediation. Mutational studies can now be carried out to identify key amino acids required for activity and specificity. The impact of the type of corrinoid incorporated into the RDase on activity and substrate range can also be more definitively investigated. However, the current standard assays used in this work require development of analytical methods and individual standards for each substrate and product to detect activity; a general assay to measure nonspecific activity would allow data to be obtained more quickly and would facilitate high-throughput analysis.

This work also has many implications for bioremediation. Individual RDases can be screened on wider substrates panels to better delineate substrate ranges and to quantify effects of putative inhibitors. This knowledge would better inform the choice of bioaugmentation culture(s) when targeting complex contamination sites. Furthermore, this expression system will also allow the functional determination for the huge number of undescribed rdhA genes present in metagenomes, which in turn could identify novel candidate organisms for bioremediation. Finally, having an established expression method in E. coli gives the opportunity to rationally engineer and evolve RDases to dehalogenate emerging and highly halogenated compounds. However, two bottlenecks that still must be addressed to truly jumpstart the future studies of RDases are (i) generalizing or extending the assay to Chloroflexi, and (ii) developing a high-throughput and generalizable assay to make data production quicker and allow for the testing of a wide array of substrates and enzymes.

In conclusion, we demonstrate the necessity of cobalamin and anaerobic conditions for the heterologous expression of respiratory RDases from the obligate OHRB Dehalobacter. The implementation of the pBAD42-BtuCEDFB expression vector allowed for the expression of active RDases in E. coli. We demonstrated that this system is easy to modify and was widely applicable within the Dehalobacter genus by expressing and obtaining activity from six unique RDases. The expressed RDases were able to be purified at high yields making this system useful for future analyses that require a lot of material. We expect that this expression system will allow for the study and characterization of many RDases that have so far remained elusive.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All chemicals and primers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) except for antibiotics, terrific broth (TB) media, and Bradford reagent which were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). All gases were supplied from Linde Canada Inc. (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Synthetic genes and the pET21-hchA plasmid were synthesized by Twist Bioscience (San Francisco, CA, USA) using codon optimized sequences for TmrA (WP_034377773), CfrA (AFV05253), DcrA (AFV02209), and HchA (IMG Accession: 2823894057). DNA isolations and purifications were done with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit and the QIAquick PCR purification kit, and nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose resin was purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). PCR reagents, restriction enzymes, Gibson Assembly master mix, the 1 kb DNA ladder, and E. coli DH5α were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). Sanger sequencing was performed by The Centre for Applied Genomics at SickKids Hospital (Toronto, ON, Canada). The pBAD42-BtuCEDFB plasmid was generously provided by the Booker Lab (Pennsylvania State University, PA, USA). E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔiscR was obtained from Patrick Hallenbeck (50, 52), E. coli BL21(DE3) cat-araC-PBAD-suf, ΔiscR::kan, ΔhimA::TetR, abbreviated to E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR, and E. coli SufFeScient were generously provided by the Antony and Kiley Labs (St. Louis University School of Medicine, MO, USA; University of Wisconsin-Madison, WI, USA) (51). The empty p15TV-L plasmid is available at Addgene #26093. All buffers used in protein extractions and purifications were purged with N2 gas prior to use. The anaerobic mixed dechlorinating culture ACT-3 was enriched in 2001 from groundwater contaminated with 1,1,1-TCA and trichloroethene in the northeastern United States. Several sub-enrichments have been made by growing the culture on 1,1,1-TCA, chloroform, or 1,1-dichloroethane as electron acceptors. For further culture growth and maintenance information see references (55, 59). Crude extracts (lysates) from the ACT-3 culture were used as a positive control in the chloroalkane reduction assays.

Plasmid construction and transformation.

Full tmrA, cfrA, and dcrA genes were codon-optimized and ordered as synthetic gene blocks (Text S1). Two primer sets were designed for amplification of the genes with extensions to introduce a 15 bp overlap sequence for Gibson Assembly into the linearized p15TV-L plasmid. One primer pair amplified the TAT signal peptide sequence and introduced a C-terminal x6His tag extension in case the N-terminal tag was cleaved with the endogenous TAT processing machinery, this pair was only designed for TmrA amplification. The second primer pair amplified the gene without the TAT sequence to truncate the cloned gene, the gene began at the previously observed TAT cleavage site (14). Primer sequences and their descriptions are in Table 3 and Table S3. Genes were amplified by PCR using the synthetic genes as the templates. The p15TV-L plasmid was linearized by BseRI digestion. The linear plasmid and the amplified gene products were purified with a QIAquick PCR Purification kit. The amplified gene product and the linearized plasmid were ligated by Gibson Assembly, transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells via chemical transformation, and plated on carbenicillin (100 ng/mL) selection plates.

TABLE 3.

Primers used for amplification of rdhA genes for cloning

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| TmrA_TAT_F | TTGTATTTCCAGGGCATGGACAAGGAAAAAAGTAAC | Forward primer to amplify tmrA with TAT signal peptide sequence for Gibson Assembly into p15TV-L. |

| TmrA_CHis_R | CAAGCTTCGTCATCAATGGTGATGGTGGTGATGGCCGCTGCTTTTCCACCAATCTGCTTT | Reverse primer to amplify tmrA with an added C-terminal x6His tag for Gibson Assembly into p15TV-L. |

| OG97_no_TAT_F | TTGTATTTCCAGGGCATGATCGATCCCAAACAGGTA | Amplify enzymes from OG 97 (tmrA, cfrA, dcrA, etc.), without TAT signal peptide sequence for Gibson Assembly into p15TVL. |

| TmrA_R | CAAGCTTCGTCATCATTATTTCCACCAATCTGCTTTC | Reverse primer to amplify tmrA for Gibson Assembly into p15TV-L. |

| CfrA_DcrA_R | CAAGCTTCGTCATCATTATTTCCACCAATCTGCTATC | Reverse primer to amplify cfrA and dcrA for Gibson Assembly into p15TV-L. |

Bolded sequences are complimentary to the rdhA gene, nonbolded sequences are an extension for Gibson assembly, and the underlined sequence is the added His tag.

Positive transformants were picked, grown up, and their plasmids were extracted. The plasmids were screened by PCR amplification of the desired gene and Sanger sequencing using universal T7 primers. The sequencing-confirmed plasmids were transformed into both E. coli ΔiscR and E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR strains with and without pBAD42-BtuCEDFB; those with pBAD42-BtuCEDFB were selected with carbenicillin and spectinomycin (50 ng/mL) plates. The plasmid p15TVL-tmrA was also transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) Lobstr and E. coli SufFeScient. The codon-optimized hchA gene without the TAT signal sequence, as predicted by SignalP-5.0 (60), was ordered in pET-21 with a C-terminal x6His tag. The genes for DHB14 and DHB15 had been previously amplified from genomic DNA extracted from the ACT-3 mixed culture and cloned into p15TV-L with their TAT signal sequences by the Yakunin and Savchenko Labs (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada). The plasmids pET21-hchA, p15TVL-DHB14, and p15TVL-DHB15 were transformed into E. coli ΔiscR with pBAD42-BtuCEDFB. Descriptions of all expression plasmids are included in Table 4, and descriptions of the E. coli strains used are in Table 5.

TABLE 4.

Expression plasmids used in this work

| Plasmid | Encoded enzyme | Tags | Induction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p15TVL-tmrA-TAT | TmrA (with TAT sequence) | N-term 6xHis, C-term 6xHis |

IPTG | This work |

| p15TVL-tmrA | TmrA (no TAT) | N-term 6xHis | IPTG | This work |

| p15TVL-cfrA | CfrA (no TAT) | N-term 6xHis | IPTG | This work |

| p15TVL-dcrA | DcrA (no TAT) | N-term 6xHis | IPTG | This work |

| pET21-hchA | HchA (no TAT) | C-term 6xHis | IPTG | This work |

| p15TVL-DHB14 | DHB14 (with TAT) | N-term 6xHis | IPTG | Yakunin and Savchenko labs (University of Toronto) |

| p15TVL-DHB15 | DHB15 (with TAT) | N-term 6xHis | IPTG | Yakunin and Savchenko labs (University of Toronto) |

| pBAD42-BtuCEDFB | BtuB, BtuCD, BtuE, BtuF | N/A | Arabinose | Booker lab (Pennsylvania State University) (44) |

TABLE 5.

Escherichia coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Cloning strain of E. coli. | New England Biolabs |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) Lobstr | Expression strain of E. coli. | (67) |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔiscR | Expression strain of E. coli with a deletion of the isc operon repressor, iscR, for increased iron-sulfur cluster production. KanR | Hallenbeck lab (University of Montreal) (50, 52) |

|

E. coli SufFeScient (BL21λDE3 cat-PsufA(Fur*)) |

Expression strain of E. coli with a repaired and overexpressed suf operon, for increased iron-sulfur cluster production. CmR | Antony lab (St. Louis University School of Medicine) and Kiley lab (University of Wisconsin-Madison) (51) |

|

E. coli

ara-suf ΔiscR (BL21λDE3 cat-araC-PBAD-suf, ΔiscR:: kan, ΔhimA::TetR) |

Expression strain of E. coli with a deletion of the isc operon repressor, iscR, and suf expression under arabinose control for increased iron-sulfur cluster production. CmR, KanR, TetR |

Small-scale protein expression and lysis.

Full schematic of small-scale expression and lysate activity assays is shown in Fig. 1. An aliquot (200 μL) of starter cultures containing the desired expression plasmids were used to inoculate 20 ml of TB media with the appropriate antibiotics in 160-mL serum bottles, or 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks if full expression was aerobic. In initial tests to establish the expression system, cultures in the serum bottles were grown anaerobically by sealing the bottle and purging the media with N2 prior to inoculation, these were then treated the same as the aerobic cultures (same induction and incubation times) though the cell density tended to be lower in these samples. After further optimization, the finalized expression system is described here. Bottles and flasks were kept aerobic for growth, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C, 180 rpm until the optical density at 600 nm (O.D.600) reached 0.4 to 0.6. Cultures were supplemented with a final concentration of 1 μM hydroxycobalamin and btu expression was induced with a final concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol) arabinose (regardless of whether pBAD42-BtuCEDFB was present in the culture strain). Cultures were incubated again at 37°C, 180 rpm until the O.D.600 reached 0.8 to 1. All cultures were put on ice, cultures in serum bottles were stoppered, crimped, and the headspace was purged with N2 gas for 10 min to remove excess O2, cultures in flasks remained aerobic. All cultures were supplemented with final concentrations of either 50 μM ammonium ferric sulfate used during TmrA expression optimization, or 50 μM cysteine and 50 μM ammonium ferric citrate used with all subsequent cultures to align with recommended iron-sulfur sources though no change in activity was observed (61), and RDase expression was induced using 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cultures were incubated at 15°C, 180 rpm overnight. Expression of TmrA under different conditions tested is in Fig. S1 and Text S3.

After incubation, all cultures were handled in a Coy anerobic glove box with a supply gas composition of 10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g (Avanti-JE SN:JSE07L45, Beckman Coulter) and 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were discarded and the pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of Buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100) with 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (PIC; final concentrations: 1 mM benzamidine, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) added fresh at time of use. In some cases, Triton X-100 in Buffer A was replaced with either 1% 3-((3-chloamidopropyl)dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) or 1% digitonin. The suspended pellet was transferred to a 2 mL O-ringed microcentrifuge tube with 50 mg of glass beads (150 to 500 μm). The cells were lysed via bead beating by vortexing the tubes for 2 min and resting on ice for 1 min, and repeated 3 times. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g (Thermo Scientific microcentrifuge, serial: 1931100817155), 4°C for 5 min. The soluble lysate fraction was used for subsequent activity assays. The positive controls using ACT-3, a mixed culture enriched maintained on either chloroform or 1,1,1-TCA as electron acceptor, were prepared the same way only 0.5 mL of buffer was used for resuspension.

TmrA and HchA large-scale protein expression and purification.

An overnight start culture (5 mL) of either E. coli ara-suf ΔiscR p15TVL-tmrA + pBAD42-BtuCEDFB or E. coli ΔiscR pET21-hchA + pBAD42-BtuCEDFB was used to inoculate 1 L of TB medium with appropriate antibiotics in a 2-L glass bottle (Fisher Scientific), that was kept aerobic for growth with a foil cap. The culture was incubated at 37°C, 150 rpm until the O.D.600 reached 0.4 to 0.6, 3 μM hydroxycobalamin was supplemented to the culture, and 0.2% (wt/vol) arabinose was used to induce btu expression. This was incubated at 37°C, 150 rpm again until the O.D.600 reached 0.8 to 1, after which the culture was put on ice, sealed with a rubber septa and cap, and the headspace was purged with N2 gas for 1 h to make anaerobic. The culture was supplemented with 50 μM cysteine and 50 μM ammonium ferric citrate, and RDase expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG. The culture was then incubated overnight at 15°C, 150 rpm.

The expression culture was handled in a Coy anaerobic glove box or kept sealed in an airtight vessel for all of the following steps. The culture was harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g, 4°C for 15 min (Avanti-JE SN:JSE07L45, Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of Binding Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 30 mM imidazole) per 1 g of wet cell weight with 1 mM TCEP and PIC added fresh to the buffer from concentrated stocks. The cells were lysed with the addition of 10x Bug Buster concentrate (Millipore), diluted to 1x concentration, 0.3 mg/mL lysozyme, 1.5 μg/mL DNase, and 10 mM MgCl2 (final concentrations). The lysate was incubated at RT shaking at 50 rpm for 20 min. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 29,000 × g, 4°C for 20 min (Avanti-JE SN:JSE07L45, Beckman Coulter).

A 1-mL Ni-NTA resin in a glass gravity-flow column (Econo-Column, Bio-Rad, USA) was set up inside a Coy anaerobic glove box with an atmosphere of 100% N2. Ni-NTA (1 to 2 mL) resin was purged with N2 prior to use. The column was washed with 5 column volumes (CVs) of ddH2O and conditioned with 5 CVs of binding buffer. The clarified cell lysate was loaded onto the column, and flow through was collected for subsequent analysis. The column was washed with 20 CVs of binding buffer until no protein was detected in the eluent by Bradford reagent. The RDase was eluted from the column using Elution Buffer (Buffer A, 300 mM imidazole). Collected fractions underwent a buffer exchange into Buffer A (without imidazole) with 1-mM TCEP, to remove the imidazole and the protein was concentrated using a 30-kDa cut-off Millipore filter tube. The concentrated protein was quantified using a Bradford assay and distributed into aliquots for flash freezing and storage in liquid N2. All steps of the purification were imaged and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the purity of the final enriched enzyme was estimated by band density compared with the overall lane density using Image Lab v6.1 Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The SDS-PAGE of the TmrA purification and band/lane density measurements for purity estimation are shown in Fig. S2, and protein yield is in Table S5 of Text S3. The same purity analysis and yield calculations were done for HchA.

Dechlorinating activity assays.

Initial protein activity assays to test btu expression and effect of oxygen were carried out in 2-mL reaction volumes, all subsequent assays were done at a volume of 500 μL to conserve materials. All assays were carried out in glass vials with no headspace and sealed with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-lined caps, these were set up and incubated under anaerobic conditions in a Coy glove box with a supply gas composition of 10% CO2, 10% H2, and 80% N2. The assay was carried out in a buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM Ti(III) citrate, and 2 mM methyl viologen. Enzyme was added in the form of either 50-μL soluble cell lysate (100 μL for 2 mL reaction volumes) or 0.3 to 2 μg purified TmrA/HchA. All substrates, except the hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) isomers, were supplemented from saturated water stocks to final concentrations of either 0.05 mM (in the case of perchloroethene), 0.5 mM, or 1 mM using Hamilton glass syringes. HCH was added from a 10 mM stock solution in DMSO to a final concentration of 0.3 mM. Lysate assays were kept at RT overnight (18 h to 24 h), purified enzyme assays were kept at RT for 1 h and then were stopped by acidification as described below.

All assays were stopped by transferring 0.4 mL (1 mL was taken for reactions with 2 mL total volumes) of the reaction volume into acidified water (pH < 2 using HCl) for a total sample volume of 6 mL; this was sealed in a 10-mL vial for headspace analysis by gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID). The assays were all run using the same GC-FID separation method on an Agilent 7890A GC instrument equipped with an Agilent GS-Q plot column (30 m length, 0.53 mm diameter). Sample vials were equilibrated to 70°C for 40 min in an Agilent G1888 autosampler, then 3 mL of the sample headspace was injected (injector set to 200°C) onto the column by a packed inlet. The flow rate was 11 mL/min of helium as the carrier gas. The oven was held at 35°C for 1.5 min, raised at a rate of 15°C/min up to 100°C, the ramp rate was reduced to 5°C/min until the oven reached 185°C at which point it was held for 10 min. Finally, the oven was ramped up to 200°C at a rate of 20°C/min and held for 10 min. The detector was set to a temperature of 250°C. Data were analyzed using Agilent ChemStation Rev. B.04.02 SP1 software, and peak areas were converted to liquid concentration using standard curves (external calibration) for each compound. An example chromatogram is shown in Fig. S4 and Text S3.

Three types of negative controls for the enzyme assays were used: enzyme-free controls, deactivated enzyme controls, and free cobalamin (cobalamin only; no enzyme) controls. Enzymes were deactivated by boiling lysate or purified sample for 5 to 10 min. This was only done for one representative enzyme for each substrate to verify there was no abiotic reaction from the E. coli lysates. Reduction using free cobalamin was tested using a final assay concentration of 0.2-μM cobalamin for lysate assays, and at an equimolar concentration to the enzyme when used as a negative control in the purified enzyme assays. ACT-3 mixed culture was used as a positive control where possible, using 50 μL of soluble cell lysate, similar to the heterologously expressed enzymes. All enzyme lysates were tested with six replicates (two lysates from independently grown expression cultures with three assays each) on their known substrates to confirm activity, and a minimum of duplicates on additional substrates (two lysates from independently grown cultures). Negative controls for α-HCH were only done as single samples due to limited substrate. The purified TmrA/HchA preparations were tested in triplicates. The number of replicates is indicated where the data are presented, all of the individual sample raw data are shown in Tables S6 to S10.

Cofactor quantification.

Iron content of purified TmrA and HchA was quantified using a ferrozine method as previously described (50, 62, 63). A range of 0.5 to 20 nmol FeCl3 was used to create a standard curve. Protein samples were boiled for 5 min; both the samples and standards were mixed with 300 μL iron-releasing agent (1.4 M HCl, 0.3 M KMnO4) and heated at 60°C for 30 min. This was brought to RT and then mixed with 150-μL iron-binding agent (6.5 mM ferrozine, 6.5 mM neocuproine-HCl, 2.5 M ammonium acetate, 1 M ascorbic acid). The absorbance was measured at 560 nm and iron content in the protein sample was determined by the standard curve and adjusted with the purity of TmrA/HchA to get an occupancy ratio that was not skewed by the impurities.

Cobalamin was quantified using two separate methods, in both cases cyanocobalamin at a concentration range of 0.1 to 10 μM (final concentration) was used for a standard curve. The first method was used as previously described with some modifications (35, 44, 64). The standard samples and protein samples (50 μL) were mixed with 15 mM KCN to a volume of 750 μL and were heated at 80°C for 10 min. The samples were clarified by centrifugation and their absorbance was measured at 367 nm and at 650 nm to normalize to the baseline. The second method was previously described (65, 66); briefly, samples were mixed with 10 mM KCN in 80% (vol/vol) methanol and acidified using 3% (vol/vol) acetic acid. Samples were then heated at 80°C for 1 h with slow shaking. Samples were clarified by centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred and dried, and the extract was resuspended in ddH2O such that the concentration was unaltered. These samples were analyzed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS). For both methods the cobalamin occupancy was adjusted for the purity of the enzymes.

The samples analyzed by UHPLC-MS were separated on a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 UHPLC instrument equipped with a Thermo Scientific Hypersil Gold C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm particle size) and a guard column held at 30°C. The sample (10 μL) was injected by an autosampler held at 5°C. Eluent A was 5 mM ammonium acetate in water, eluent B was 5 mM ammonium acetate in methanol, the flow rate was set to 300 μL/min. The separation method used started with a mix of 2% eluent B for 0.46 min, then held a linear gradient to 15% B from 0.46 to 0.81 min; a linear gradient to 50% B from 0.81 to 3.32 min; a linear gradient to 95% B from 3.32 to 5.56 min; 95% B was held until 7.5 min; finally, the composition was reduced to 2% B with a linear gradient from 7.5 to 8 min, and held at 2% B from 8 to 12 min. The eluent was introduced to a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive mass spectrometer with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI-II) probe at a spray voltage of 3.5 kV, and capillary temperature of 320°C. Data collection was done in positive ion modes with a scan range of 1,000 to 2,000 m/z, mass resolution of 70 000, an automatic gain control target of 3 × 106, and a maximum injection time of 200 ms. Data were processed using Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser v3.1 software, cyanocobalamin was detected at an [M+H]+ of 1355.5747 (ppm error = 5), and the peak area was used for quantification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC PGS-D to KJP) and a Canadian Research Chair to E.A.E.

E.A.E. and K.J.P. conceived of the experiments. R.F. performed the LC-MS separation and analysis of cobalamin, and K.J.P. conducted all other experiments. K.J.P. and E.A.E. drafted the manuscript.

We thank the Booker Lab from Pennsylvania State University for gifting the pBAD42-BtuCEDFB plasmid, and the Antony Lab from the St. Louis University School of Medicine and Kiley lab from the University of Wisconsin-Madison for gifting us the E. coli SufFeScient and ara-suf ΔiscR strains. We thank Connor Bowers for cloning and testing the activity of the SUMO fusion constructs. We thank Anna Khusnutdinova for helpful advice in working with anaerobic enzymes and more generally the Yakunin and Savchenko labs at the University of Toronto for sharing expression vectors and several RDase constructs, and for their support during this study. Finally, we thank Patrick Hellenbeck for providing the E. coli ΔiscR strain.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Edwards, Email: elizabeth.edwards@utoronto.ca.

Jennifer B. Glass, Georgia Institute of Technology

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohn WW, Tiedje JM. 1990. Strain DCB-1 conserves energy for growth from reductive dechlorination coupled to formate oxidation. Arch Microbiol 153:267–271. 10.1007/BF00249080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hug LA, Maphosa F, Leys D, Löffler FE, Smidt H, Edwards EA, Adrian L. 2013. Overview of organohalide-respiring bacteria and a proposal for a classification system for reductive dehalogenases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20120322. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duhamel M, Edwards EA. 2006. Microbial composition of chlorinated ethene-degrading cultures dominated by Dehalococcoides. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58:538–549. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grostern A, Edwards EA. 2006. Growth of Dehalobacter and Dehalococcoides spp. during degradation of chlorinated ethanes. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:428–436. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.428-436.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni S, Fredrickson JK, Xun L. 1995. Purification and characterization of a novel 3-chlorobenzoate-reductive dehalogenase from the cytoplasmic membrane of Desulfomonile tiedjei DCB-1. J Bacteriol 177:5135–5139. 10.1128/jb.177.17.5135-5139.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fincker M, Spormann AM. 2017. Biochemistry of catabolic reductive dehalogenation. Annu Rev Biochem 86:357–386. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Huang L, Xu C, Liu X, He J, Zinder SH, Li S, Jiang J. 2013. Molecular characterization of the enzymes involved in the degradation of a brominated aromatic herbicide. Mol Microbiol 89:1121–1139. 10.1111/mmi.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne KAP, Quezada CP, Fisher K, Dunstan MS, Collins FA, Sjuts H, Levy C, Hay S, Rigby SEJ, Leys D. 2015. Reductive dehalogenase structure suggests a mechanism for B12-dependent dehalogenation. Nature 517:513–516. 10.1038/nature13901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molenda O, Puentes Jácome LA, Cao X, Nesbø CL, Tang S, Morson N, Patron J, Lomheim L, Wishart DS, Edwards EA. 2020. Insights into origins and function of the unexplored majority of the reductive dehalogenase gene family as a result of genome assembly and ortholog group classification. Environ Sci Process Impacts 22:663–678. 10.1039/c9em00605b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futagami T, Morono Y, Terada T, Kaksonen AH, Inagaki F. 2009. Dehalogenation activities and distribution of reductive dehalogenase homologous genes in marine subsurface sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6905–6909. 10.1128/AEM.01124-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hug LA, Edwards EA. 2013. Diversity of reductive dehalogenase genes from environmental samples and enrichment cultures identified with degenerate primer PCR screens. Front Microbiol 4:341. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magnuson JK, Stern RV, Gossett JM, Zinder SH, Burris DR. 1998. Reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethene to ethene by a two-component enzyme pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:1270–1275. 10.1128/AEM.64.4.1270-1275.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Pas BA, Gerritse J, de Vos WM, Schraa G, Stams AJM. 2001. Two distinct enzyme systems are responsible for tetrachloroethene and chlorophenol reductive dehalogenation in Desulfitobacterium strain PCE1. Arch Microbiol 176:165–169. 10.1007/s002030100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jugder BE, Bohl S, Lebhar H, Healey RD, Manefield M, Marquis CP, Lee M. 2017. A bacterial chloroform reductive dehalogenase: purification and biochemical characterization. Microb Biotechnol 10:1640–1648. 10.1111/1751-7915.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller JA, Rosner BM, Von Abendroth G, Meshulam-Simon G, McCarty PL, Spormann AM. 2004. Molecular identification of the catabolic vinyl chloride reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS and its environmental distribution. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:4880–4888. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4880-4888.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisaillon A, Beaudet R, Lépine F, Déziel E, Villemur R. 2010. Identification and characterization of a novel CprA reductive dehalogenase specific to highly chlorinated phenols from Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain PCP-1. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7536–7540. 10.1128/AEM.01362-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maillard J, Schumacher W, Vazquez F, Regeard C, Hagen WR, Holliger C. 2003. Characterization of the corrinoid iron-sulfur protein tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Dehalobacter restrictus. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:4628–4638. 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4628-4638.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye L, Schilhabel A, Bartram S, Boland W, Diekert G. 2010. Reductive dehalogenation of brominated ethenes by Sulfurospirillum multivorans and Desulfitobacterium hafniense PCE-S. Environ Microbiol 12:501–509. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyer A, Pagé-Bélanger R, Saucier M, Villemur R, Lépine F, Juteau P, Beaudet R. 2003. Purification, cloning and sequencing of an enzyme mediating the reductive dechlorination of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol from Desulfitobacterium frappieri PCP-1. Biochem J 373:297–303. 10.1042/BJ20021837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasotkina J, Walters T, Maruya KA, Ragsdale SW. 2001. Characterization of the B12- and iron-sulfur-containing reductive dehalogenase from Desulfitobacterium chlororespirans. J Biol Chem 276:40991–40997. 10.1074/jbc.M106217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Pas BA, Smidt H, Hagen WR, van der Oost J, Schraa G, Stams AJM, de Vos WM. 1999. Purification and molecular characterization of ortho-chlorophenol reductive dehalogenase, a key enzyme of halorespiration in Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans. J Biol Chem 274:20287–20292. 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christiansen N, Ahring BK, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. 1998. Purification and characterization of the 3-chloro-4-hydroxy-phenylacetate reductive dehalogenase of Desulfitobacterium hafniense. FEBS Lett 436:159–162. 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thibodeau J, Gauthier A, Duguay M, Villemur R, Lépine F, Juteau P, Beaudet R. 2004. Purification, cloning, and sequencing of a 3,5-dichlorophenol reductive dehalogenase from Desulfitobacterium frappieri PCP-1. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:4532–4537. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4532-4537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang S, Chan WWM, Fletcher KE, Seifert J, Liang X, Löffler FE, Edwards EA, Adrian L. 2013. Functional characterization of reductive dehalogenases by using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:974–981. 10.1128/AEM.01873-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X, Molenda O, Tang S, Edwards EA. 2015. Identity and substrate specificity of reductive dehalogenases expressed in Dehalococcoides-containing enrichment cultures maintained on different chlorinated ethenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4626–4633. 10.1128/AEM.00536-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adrian L, Rahnenführer J, Gobom J, Hölscher T. 2007. Identification of a chlorobenzene reductive dehalogenase in Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:7717–7724. 10.1128/AEM.01649-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang S, Edwards EA. 2013. Identification of Dehalobacter reductive dehalogenases that catalyse dechlorination of chloroform, 1,1,1- trichloroethane and 1,1-dichloroethane. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20120318. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molenda O, Quaile AT, Edwards EA. 2016. Dehalogenimonas sp. strain WBC-2 genome and identification of its trans-dichloroethene reductive dehalogenase, TdrA. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:40–50. 10.1128/AEM.02017-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfán-Guzmán R, Ertan H, Manefield M, Lee M. 2017. Isolation and characterization of Dehalobacter sp. strain TeCB1 including identification of TcbA: A novel tetra- and trichlorobenzene reductive dehalogenase. Front Microbiol 8:558. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumann A, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. 1998. Tetrachloroethene dehalogenase from Dehalospirillum multivorans: Cloning, sequencing of the encoding genes, and expression of the pceA gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180:4140–4145. 10.1128/JB.180.16.4140-4145.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suyama A, Yamashita M, Yoshino S, Furukawa K. 2002. Molecular characterization of the PceA reductive dehalogenase of Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51. J Bacteriol 184:3419–3425. 10.1128/JB.184.13.3419-3425.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sjuts H, Fisher K, Dunstan MS, Rigby SE, Leys D. 2012. Heterologous expression, purification and cofactor reconstitution of the reductive dehalogenase PceA from Dehalobacter restrictus. Protein Expr Purif 85:224–229. 10.1016/j.pep.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mac Nelly A, Kai M, Svatoš A, Diekert G, Schubert T. 2014. Functional heterologous production of reductive dehalogenases from Desulfitobacterium hafniense strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4313–4322. 10.1128/AEM.00881-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bommer M, Kunze C, Fesseler J, Schubert T, Diekert G, Dobbek H. 2014. Structural basis for organohalide respiration. Science 346:455–458. 10.1126/science.1258118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jugder B-E, Payne KAP, Fisher K, Bohl S, Lebhar H, Manefield M, Lee M, Leys D, Marquis CP. 2018. Heterologous production and purification of a functional chloroform reductive dehalogenase. ACS Chem Biol 13:548–552. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunze C, Diekert G, Schubert T. 2017. Subtle changes in the active site architecture untangled overlapping substrate ranges and mechanistic differences of two reductive dehalogenases. FEBS J 284:3520–3535. 10.1111/febs.14258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parthasarathy A, Stich TA, Lohner ST, Lesnefsky A, Britt RD, Spormann AM. 2015. Biochemical and EPR-spectroscopic investigation into heterologously expressed vinyl chloride reductive dehalogenase (VcrA) from Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain VS. J Am Chem Soc 137:3525–3532. 10.1021/ja511653d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura R, Obata T, Nojima R, Hashimoto Y, Noguchi K, Ogawa T, Yohda M. 2018. Functional expression and characterization of tetrachloroethene dehalogenase from Geobacter sp. Front Microbiol 9:1774. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang H, Kang J, Zhang D. 2017. Microbial production of vitamin B12: a review and future perspectives. Microb Cell Fact 16:15. 10.1186/s12934-017-0631-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bassford PJ, Kadner RJ. 1977. Genetic analysis of components involved in vitamin B12 uptake in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 132:796–805. 10.1128/jb.132.3.796-805.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cadieux N, Bradbeer C, Reeger-Schneider E, Köster W, Mohanty AK, Wiener MC, Kadner RJ. 2002. Identification of the periplasmic cobalamin-binding protein BtuF of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 184:706–717. 10.1128/JB.184.3.706-717.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borths EL, Poolman B, Hvorup RN, Locher KP, Rees DC. 2005. In vitro functional characterization of BtuCD-F, the Escherichia coli ABC transporter for vitamin B12 uptake. Biochemistry 44:16301–16309. 10.1021/bi0513103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hvorup RN, Goetz BA, Niederer M, Hollenstein K, Perozo E, Locher KP. 2007. Asymmetry in the structure of the ABC transporter-binding protein complex BtuCD-BtuF. Science 317:1387–1390. 10.1126/science.1145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lanz ND, Blaszczyk AJ, McCarthy EL, Wang B, Wang RX, Jones BS, Booker SJ. 2018. Enhanced solubilization of class B radical S-adenosylmethionine methylases by improved cobalamin uptake in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 57:1475–1490. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVeaux LC, Kadner RJ. 1985. Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli: Cloning of the btuCD region. J Bacteriol 162:888–896. 10.1128/jb.162.3.888-896.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shultis DD, Purdy MD, Banchs CN, Wiener MC. 2006. Outer membrane active transport: Structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science 312:1396–1399. 10.1126/science.1127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rioux CR, Kadner RJ. 1989. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli K12 does not require the btuE gene of the btuCED operon. Mol Gen Genet 217:301–308. 10.1007/BF02464897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blaszczyk AJ, Wang RX, Booker SJ. 2017. TsrM as a model for purifying and characterizing cobalamin-dependent radical S-adenosylmethionine methylases. Methods Enzymol 595:303–329. 10.1016/bs.mie.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halliwell T, Fisher K, Payne K, Rigby SEJ, Leys D. 2021. Heterologous expression of cobalamin dependent class-III enzymes. Protein Expr Purif 177:105743. 10.1016/j.pep.2020.105743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akhtar MK, Jones PR. 2008. Deletion of iscR stimulates recombinant clostridial Fe-Fe hydrogenase activity and H2-accumulation in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 78:853–862. 10.1007/s00253-008-1377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corless EI, Mettert EL, Kiley PJ, Antony E. 2020. Elevated expression of a functional Suf pathway in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) enhances recombinant production of an iron-sulfur cluster-containing protein. J Bacteriol 202:e00496-19. 10.1128/JB.00496-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuchenreuther JM, Grady-Smith CS, Bingham AS, George SJ, Cramer SP, Swartz JR. 2010. High-yield expression of heterologous [FeFe] hydrogenases in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 5:e15491. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan WWM. 2010. Characterization of reductive dehalogenases in a chlorinated ethene-degrading bioaugmentation culture. University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]