Abstract

Determining when to perform a bowel anastomosis and whether to divert can be difficult, as an anastomosis made in a high-risk patient or setting has potential for disastrous consequences. While the surgeon has limited control over patient-specific characteristics, the surgeon can control the technique used for creating anastomoses. Protecting and ensuring a vigorous blood supply is fundamental, as is mobilizing bowel completely, and employing adjunctive techniques to attain reach without tension. There are numerous ways to create anastomoses, with variations on the segment and configuration of bowel used, as well as the materials used and surgical approach. Despite numerous studies on the optimal techniques for anastomoses, no one method has prevailed. Without clear evidence on the best anastomotic technique, surgeons should focus on adhering to good technique and being comfortable with several configurations for a variety of conditions.

Keywords: bowel anastomosis, anastomotic technique, tension-free anastomosis, anastomotic leak

Bowel anastomosis is often the climax of the colorectal surgeon's operation, the culmination of significant planning and meticulous dissection. A well-constructed anastomosis yields timely patient recovery, reduces the chance of leak or stenosis, and provides adequate long-term function. One created in unfavorable conditions can render patients to be permanent ostomates, require additional reconstructive surgery, and subject them to complications including leak, sepsis, obstruction, and, in extreme cases, death. Therefore, careful and thoughtful attention to each anastomosis, no matter the surgeon's experience, is essential.

Factors contributing to anastomotic success are commonly categorized as patient-specific versus surgical technique. Patient-specific characteristics include nutritional status, use of medications that impair wound healing, availability of uninflamed and nonirradiated tissues for anastomosis, anemia, uncontrolled hyperglycemia, and intraoperative hemodynamic instability. 1 2 These factors are as elemental to the success of bowel anastomoses as the technical points discussed herein. Similarly, indications for a protective ostomy are not covered here, but low anastomoses (less than 6 cm from anal verge), immunosuppression, malnutrition, degree of contamination, and the patient's ability to tolerate the physiologic consequences of an anastomotic dehiscence are factors that commonly necessitate an upstream diverting ostomy, as is surgeon preference. 3 That said, a diverting ostomy cannot rescue an anastomosis made under bad conditions, it can only decrease the severity of the consequences.

The technical aspects which contribute to anastomotic success are eliminating tension, ensuring adequate perfusion, careful tissue handling, and appropriate stapler selection and manipulation. Understanding the variety of anastomotic configurations and when each type should be employed is another key to avoid complications.

Surgical Technique

Keys to avoiding anastomotic complications of leak and stricture are careful bowel handling and limited use of electrocautery, adequate visualization, ensuring adequate blood supply, and achieving a tension-free anastomosis. Handling tissue with care relies on limited bowel manipulation with forceps and clamps that have the potential to cause crush injury. When clamping bowel, atraumatic clamps designed for use on intestine should be applied with the minimal force needed to occlude the lumen. While electrocautery permits dissection, one should be cognizant of the risk of thermal spread and resultant injury that manifests several days postoperatively, particularly when the coagulation setting is used. 4 Limited electrocautery should be used on bowel to prevent these complications. The importance of adequate visualization must be recognized. In an open approach, adequate lighting and incision length are critical. For deep pelvic anastomoses, the surgeon should wear a headlight or use lighted retractors, and the vertical midline incision should extend all the way to the pubic symphysis. In a minimally invasive surgery (MIS) approach, patient positioning can help keep unnecessary bowel out of the way by taking advantage of gravity. For extracorporeal anastomoses performed in MIS procedures, the extraction site incision occasionally needs to be enlarged for adequate visualization of the bowel to be anastomosed.

Assessing Perfusion

A variety of techniques exist to evaluate perfusion of the segments to be anastomosed. Perhaps the simplest is visualizing arterial flow at the bowel wall and, in the colon, the marginal artery. 2 Dividing the bowel sharply and observing “nuisance” bleeding is a reassuring sign of perfusion. If there is any doubt about the vigor of arterial bleeding, additional bowel should be resected until acceptable bleeding is observed. 2 Palpating a pulsatile marginal artery at the bowel edge is another means of confirming adequate perfusion. 5 For thickened mesentery, intraoperative Doppler can be used to help identify arterial perfusion, though the surgeon must ensure that they hear the phasic signals characteristic of artery and not the constant “whoosh” of venous flow. 6 Other methods of gauging blood flow include fluorescence angiography. This is performed either with fluorescein or indocyanine green. Fluorescein is injected intravenously and bowel is then evaluated with ultraviolet light, such as a Wood's lamp. Its accuracy in predicting viability is limited and its use throughout a case constrained by the fact that the fluorescein persists in tissues. 7 Indocyanine green is also administered intravenously and then a near infrared imaging system is used to assess the intensity of the fluorescence as an indicator of perfusion. 7 8 The advantage of indocyanine green is its relatively rapid clearance, allowing repeated evaluation during a case. Several studies have indicated lower rate of anastomotic leak when indocyanine is used as compared with historical controls, but large randomized control trials are needed to definitively address outcomes. 9 10

Eliminating Tension

Achieving a tension-free anastomosis requires adequate mobilization of the bowel. Generally, enteroenteric anastomoses are not challenged by reach issues, nor are most ileocolic anastomoses. However, for laparoscopic ileocolic resections or right hemicolectomies where the anastomosis is performed extracorporeally via a small extraction site, one must ensure adequate mobilization of the bowel, so it can be manipulated outside of the abdominal cavity. For ileocolic anastomosis, this requires mobilization of the colon off the retroperitoneum; for a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, the omentum should be divided off the transverse colon well beyond the segment to be anastomosed. In patients with thickened mesenteries or excess subcutaneous adiposity, extracorporeal anastomoses may require enlarging the incision.

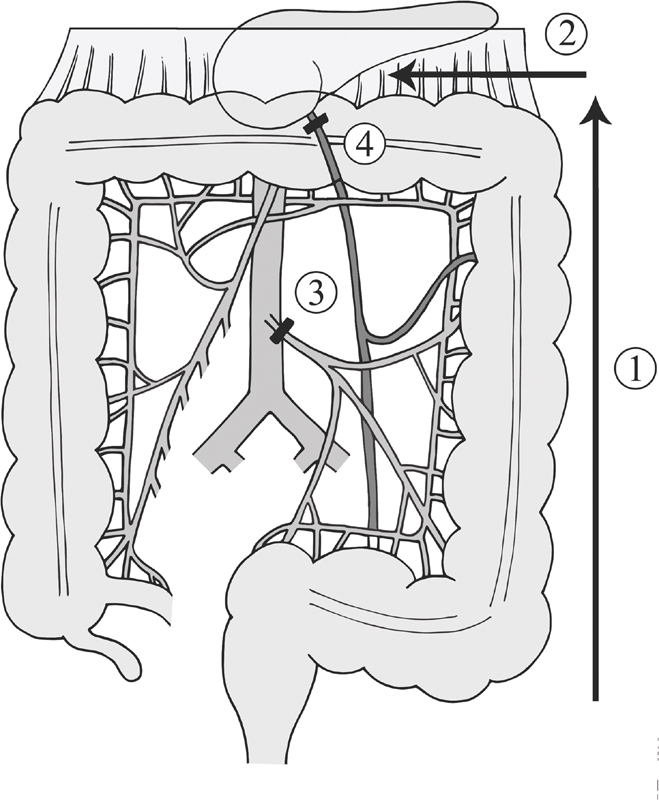

The issue of reach becomes more pronounced for left-sided and pelvic anastomoses. In these cases, the surgeon should start with full mobilization of the descending colon and splenic flexure, dividing along the white line of Toldt, and the phrenicocolic and splenocolic ligaments ( Fig. 1 , step 1). The greater omentum is divided off the distal transverse colon by entering the lesser sac ( Fig. 1 , step 2). Next, high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (proximal to the take-off of the left colic artery) and high ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein at the inferior edge of the pancreas should be performed ( Fig. 1 , steps 3 and 4). 11 If reach is still an issue, further mobilization of the transverse colon mesentery with division of middle colic branches may be necessary. Assessing bowel edge perfusion after this division is mandatory and, in fact, it may be wise to evaluate bowel viability prior to transection with the use of a vascular clamp on the vessel to be ligated. If ligating middle colic branches leads to colonic ischemia, the surgeon will then need to decide between creating an end colostomy and attempting less common anastomotic configurations.

Fig. 1.

Operative technique to obtain left colon length.

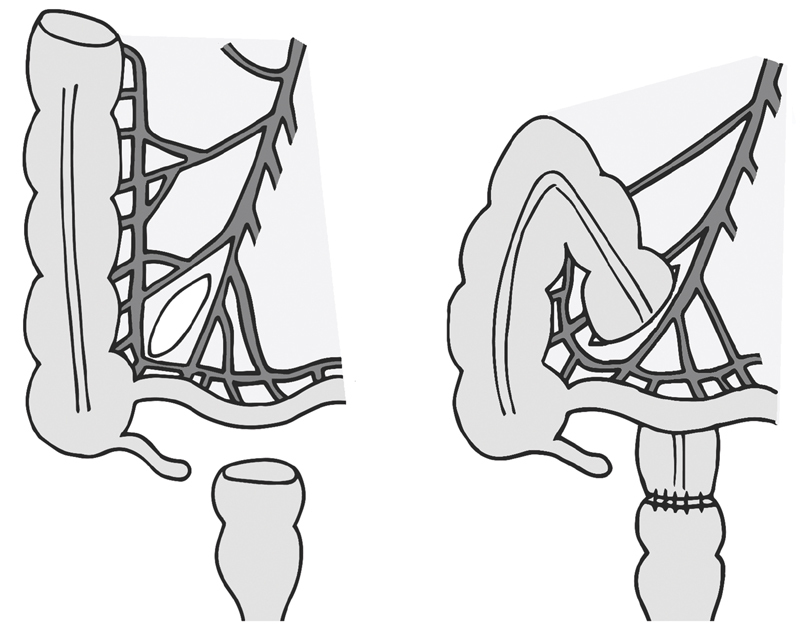

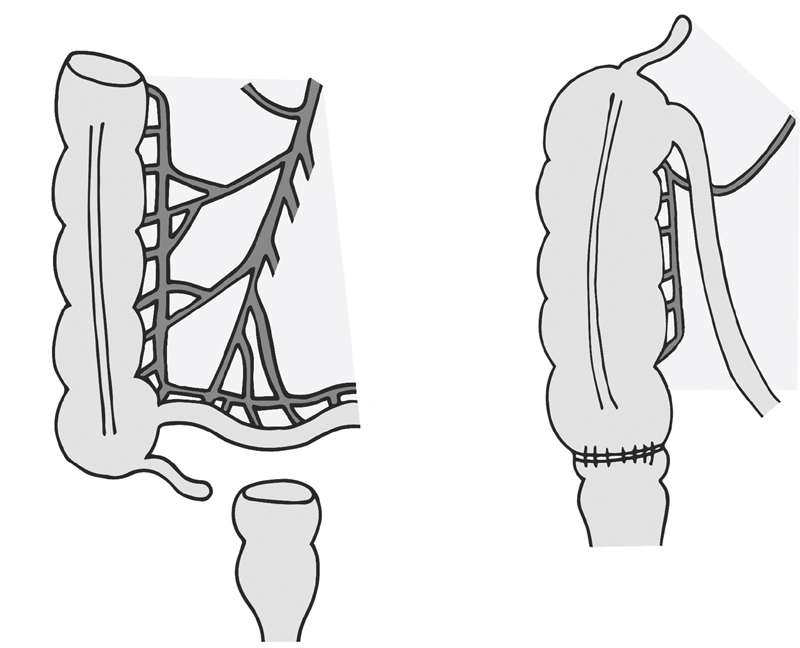

If tension persists despite those maneuvers, the transverse colon can be pulled through a retroileal window made in the terminal ileum mesentery ( Fig. 2 ). The window is made between the superior mesenteric vessels and ileocolic vessels, and should be kept small enough to prevent small bowel from herniating through. 12 The DeLoyers procedure, another maneuver described for achieving reach, is right colonic transposition which requires resection of the transverse and descending colon ( Fig. 3 ). With this, the ascending colon and hepatic flexure is fully mobilized. The right colic vessel, if present, is divided while the ileocolic pedicle is kept intact. The colon is rotated counterclockwise 180 degrees, so that the hepatic flexure now reaches into the pelvis. An appendectomy may be performed concurrently. 13 14

Fig. 2.

Retroileal anastomosis.

Fig. 3.

Right colonic transposition.

Anastomotic Configurations and Construction

While several studies have attempted to define the optimal anastomotic technique, there is no one technique that suffices for all, or even most, situations. The configurations available include side-to-side, end-to-end, side-to-end, and end-to-side anastomoses. The configuration descriptors assume the proximal bowel is listed first. For example, a side-to-end anastomosis indicates the side of proximal bowel is anastomosed to the end of distal bowel.

Materials for constructing vary from the commonly used staples and sutures to less popular and experimental approaches such as compression anastomoses and electric welding. 16 Whether stapled versus handsewn anastomoses perform better remains unanswered. For example, with ileocolic anastomoses, a Cochrane review published in 2011 reported significantly fewer leaks in stapled versus handsewn techniques, with no difference in anastomotic strictures, bleeding, wound infection, and associated mortality. 17 However, several recent trials have demonstrated the opposite, including a study of 1,414 Dutch patients which demonstrated a 5.4% anastomotic leak rate in stapled versus 2.4% in handsewn anastomoses ( p = 0.004). 18 19 This study was limited in that 72% of the anastomoses were handsewn and 28% were stapled, perhaps reflecting a bias toward the handsewn approach. Stapled anastomoses are often quicker to construct, though they have higher material-associated costs. 20 Additionally, staplers can misfire and require conversion to a handsewn anastomosis.

When performing a handsewn anastomosis, suture material, single- versus double-layer anastomosis, and running/continuous versus interrupted are choices the surgeon must make. Limited data exist to support suture material choice, though rate of absorption, elicitation of inflammatory response, and tensile strength are points of consideration. 21 22 The ANATECH trial attempted to distinguish single- versus double-layer continuous colonic anastomoses, but no difference in leak rate or other outcomes was demonstrated, though the trial was insufficiently powered. 23 Given the paucity of data to support specific choices as outlined above, the surgeon should focus on gentle tissue handling, spacing sutures appropriately, incorporating the submucosa (the strongest layer of the intestine), and tying knots securely but without causing local ischemia. With so many considerations, the type of anastomosis chosen often depends on the surgeon's familiarity with particular techniques and device availability.

Side-to-Side

This is a versatile anastomosis with multiple variations including isoperistaltic versus antiperistaltic alignment, intra- versus extracorporeal creation, and standard versus Barcelona techniques for stapling ( Fig. 4 ). It is favored for ease of creation and can be used for entero-entero, enterocolic, and colo-colic anastomoses, though there are situations where it is less optimal. While commonly used for ileocolonic anastomoses, the antiperistaltic configuration may make subsequent endoscopic intubation of the neoterminal ileum difficult, as this requires navigating a hairpin turn. 24 In patients with an ileal–anal pouch whose diverting loop ileostomy is being closed, an end-to-end anastomosis preserves that bowel for use in redo pouch construction, whereas a side-to-side closure does not. Whether antiperistaltic versus isoperistaltic is superior remains unclear; one randomized controlled study comparing the two was stopped early due to excess morbidity in the isoperistaltic group whereas another randomized controlled trial demonstrated no difference in operative time and either early or late complications. 25 26

Fig. 4.

Anastomotic configuration: side-to-side (ileum to colon, antiperistaltic, and isoperistaltic).

Extracorporeal, Hand Sewn

The two lengths of bowel are aligned with the help of stay sutures. If a two-layered technique is employed, the outer posterior row of sutures is placed 3 mm from the planned enterotomies, taking seromuscular bites. Once complete, enterotomies are created on the antimesenteric side. The posterior inner row sutures are placed, often full thickness and in a running fashion starting in the middle of the enterotomy and traveling to each corner. Approaching the corner, one may transition to the Connell suture until on the straightaway of the anterior–interior row. Once complete, the interior sutures are tied and the anterior outer layer sutures are placed in the Lembert fashion. The optimal length of the anastomosis is not defined but should be at least several centimeters at completion.

Extracorporeal, Stapled

An antiperistaltic stapled anastomosis is completed by aligning the two resection margins of bowel along their lengths, with mesenteries similarly oriented. If the ends have been stapled, an enterotomy is created at the antimesenteric edge of each staple line. One arm of the linear gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler is inserted into each enterotomy, and the stapler fired after ensuring no mesentery is caught in the staple line. The staple line should be inspected for hemostasis, the linear staple lines offset, and the common enterotomy closed with subsequent stapling. Typically, the linear stapler length used is 60 or 80 mm. A slight modification of this is the Barcelona technique developed by Ravitch, which saves the bowel resection for after the anastomotic creation. First, enterotomies are created on the antimesenteric side, several centimeters from the desired point of bowel transection. The linear GIA stapler is inserted and fired, and then the bowel is divided with another firing of the stapler to close the common enterotomy. The mesentery is divided either with an energy device or with clamps and ties. Without evidence to support this, a reinforcing suture is often placed at the crotch of the anastomosis, and the corners of the common enterotomy are often dunked or reinforced. The isoperistaltic stapled anastomosis is created similarly except for the bowel is overlapped in an isoperistaltic pattern, and the placement of the enterotomies is away from the stapled bowel ends. Additionally, the common enterotomy is closed with suture, often in two layers.

Intracorporeal

With the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, some surgeons have moved to intracorporeal anastomoses to minimize the amount of bowel that needs to be mobilized, as well as the extraction site incision size. This is of particular interest when operating on patients with high body mass index. Additionally, the extraction site can be away from the midline and placed in a less herniogenic location. Furthermore, it allows for direct visualization of the mesentery to ensure no twist occurs. 27 The downsides are that it is technically challenging as it requires manipulating bowel with enterotomies so as to prevent spillage, as well as laparoscopic suturing and knot tying. 27 28 Similar to the open approach, the steps include approximating the proximal and distal resection points and using intracorporeally placed stay sutures at the antimesenteric edge to maintain alignment. Enterotomies are made, the laparoscopic GIA stapler is placed through the enterotomies and fired. Generally, if the orientation is isoperistaltic, the enterotomy is closed with intracorporeal suturing, whereas if the orientation is antiperistaltic, the enterotomy can be closed with another firing of the stapler. A narrative review of intracorporeal anastomoses after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy found a range of anastomotic leak rate from 0 to 8.5%. 27 A recent double-blinded randomized controlled trial compared intracorporeal versus extracorporeal ileocolic anastomoses following laparoscopic right hemicolectomy in 140 patients. The surgeries took place at a high-volume center with experienced minimally invasive surgeons who had each performed at least 50 intracorporeal anastomoses. The operative times were the same between groups, as was the rate of complications at 30 days. The primary endpoint was length of stay, which was not different between groups, though the intracorporeal anastomoses patients had earlier return to flatus and stool. It should be noted, however, that the center did not adhere to enhanced recovery protocols. 29 Intracorporeal anastomoses can also be performed with the robotic platform with similar technique.

End-to-End

End-to-end anastomoses are performed for a variety of pathologies and with anatomic connections including entero-entero, ileocolic, ileorectal, colorectal, and pouch anal anastomoses ( Fig. 5 ). These can be stapled or sewn, though the ultralow coloanal anastomosis requires hand sewing. Unfortunately, lower anastomoses have a higher leak rate compared with more proximal. The leak rate in a 2011 Cochrane review of colorectal anastomoses performed electively, which included both clinically and radiographically identified leaks, and was 13.0% in the stapled and 13.4% in handsewn, an insignificant difference. 30 Counseling patients on the risks inherent to these anastomoses is critical.

Fig. 5.

Anastomotic configuration: end-to-end (colon to rectum).

That same Cochrane review examined the outcomes of stapled versus handsewn colorectal anastomoses in 1,233 elective cases and found no difference in mortality, anastomotic dehiscence, anastomotic bleeding, need for reoperation, and wound infection. 30 Stapled anastomoses were more likely to develop stricture (8 vs. 2% in handsewn), and handsewn anastomoses took longer to create. These findings persisted regardless of the anastomotic height. That said, performing these connections is facilitated greatly by end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) endoluminal circular staplers. And in the case of ileal pouch anal anastomosis, staplers afford improved function in the form of decreased seepage, increased nocturnal continence, and improved quality of life in stapled versus handsewn pouches. 31 32

When creating a stapled end-to-end anastomosis, one should aim for the largest diameter that can be safely accommodated by both ends of the bowel. 11 The bowel must be able to fit the anvil without tearing, and the stapler must be able to be advanced to the top of the stump without catching on and traumatizing the lumen. If there is question of fit, advancing EEA sizers to the top of the rectal staple line facilitates size estimation. One should start with the smallest sizer first and then gradually advance. Clearing fat from the distal end of the proximal bowel can improve visualization and also lead to less demand on the stapler. This should be done judiciously, such that the tip is not devascularized, and inadvertent electrocautery injury is avoided.

The ends should lie in proximity without tension, small bowel should be swept from underneath the descending bowel, and the descending bowel should lie without a twist. For a colorectal anastomosis, one can follow the taenia and ensure they travel in a straight line; for an ileorectal anastomosis, the mesentery should be visualized to be flat.

For distal anastomoses, the integrity is checked with some form of a leak test. The bowel upstream of the anastomosis is occluded. Options include installation of liquid, such as dilute povidone-iodine or methylene blue, or of air, with the anastomosis submerged in irrigant. Air installation can be performed with bulb syringe, rigid proctoscope, or flexible endoscope. The advantage of the flexible endoscope is the ability to directly visualize the anastomosis which, if a leak is present, may help identify the point of leak. Two large series evaluated the effects of anastomotic leak testing and found decreased leak-related adverse events with testing. 33 34 A positive leak intraoperatively requires intervention which may include suture reinforcement or revision of the anastomosis, and potentially proximal diversion. Suture reinforcement alone has been shown to be associated with a higher postoperative leak rate than when the anastomosis is revised, or when the repair is coupled with diversion. 34

Hand Sewn

Surgeons should be familiar with handsewn end-to-end anastomosis, as it can be a preferred or even necessary technique in certain situations such as ileostomy closure (particularly when upstream from an ileoanal J-pouch), small bowel resection, ileocolostomy, and coloanal anastomosis. In settings such as obstruction or ileocolonic anastomosis, the surgeon may encounter luminal diameter discrepancy. In such cases, perform the Cheatle slit, dividing the smaller caliber bowel wall longitudinally on its antimesenteric border. The bowel should be divided to the extent needed to approximate bowel diameters.

To create an end-to-end handsewn anastomosis, the bowel ends are aligned and the anastomosis is constructed with either one or two layers, with interrupted or continuous sutures. Those choices are less critical than careful attention to factors listed previously including avoiding tension, confirming perfusion, and thoughtful tissue handling. Stay sutures placed at four quadrants can improve visualization of the lumen.

For a coloanal anastomosis, anal eversion sutures or tools, such as the Lone Star retractor, are placed. The mucosa above the dentate line is incised with electrocautery, the internal sphincter divided cephalad of that, and the intersphincteric dissection continued until the pelvis is entered above the anorectal ring. Once the specimen is removed, the colon is passed into the anal canal, avoiding trauma to the distal end. Sutures are placed around the anal canal at the four quadrants with a suture in between each, for a total of eight sutures. The bites incorporate mucosa of the anal canal, as well as internal sphincter. The colon is then passed through the anal canal, and the sutures are individually placed through the colon wall, going from outside of colon to inside. Both bites, of the anal canal and of the colon wall, should be substantial. The sutures are tied and any gaps which are large enough to accommodate a clamp receive another anastomotic suture. The eversion sutures or device are then removed. 35

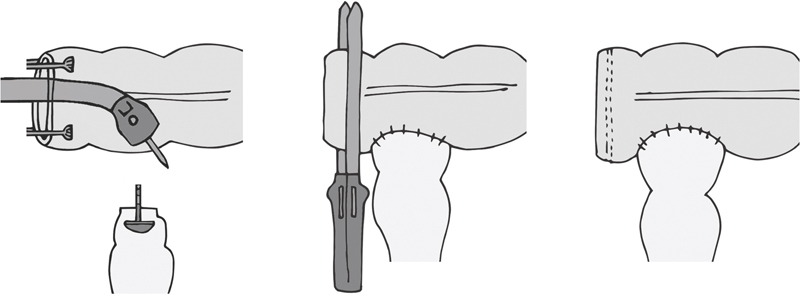

Double Stapled

This is perhaps the most common end-to-end colorectal anastomosis. The distal division is completed with a linear or curved stapler; the proximal division can be completed with atraumatic bowel clamps and sharp division or with stapler and excision of that staple line. After confirming adequate blood supply, a purse-string suture is placed around the distal end of the proximal bowel and the anvil is inserted and the purse-string is tied snugly. The purse-string is either sewn by hand or placed with a device. After cinching the purse-string, the bowel should be tight around the anvil shaft, and any gaps identified must be addressed or an incomplete anastomosis may result.

When advancing the stapler handle through the anal canal, care is taken to avoid pushing through the staple line. Positioning the patient low on the table with legs apart and lubricating the stapler are first steps. If the buttocks remain in the way, place Allis clamps at four quadrants around the anal verge and have an assistant spread them apart. Once inserted, the trocar should be deployed through or just above or below the staple line, so as to ensure perfusion of the bowel incorporated into the anastomosis.

Particular to the double-stapled colorectal anastomosis, it is critical to prevent incorporating the posterior vaginal wall, which creates a rectovaginal fistula. Adequately dissecting the rectovaginal septum, and palpating the posterior vaginal wall prior to firing the stapler lessen the chance of this occurring.

J-pouch anastomosis can have a pouch fashioned from ileum or colon. In either case, the distal end of the bowel is folded back on itself and a common channel is created. At the apex of the pouch, an enterotomy or colotomy is created, the anvil is inserted and secured with a purse string, and then mated to the trocar prior to deployment of the stapler. 2 The intricacies of ileoanal J-pouch, as well as the advantages of colonic pouch versus straight anastomosis are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Single Stapled

While double-stapled end-to-end anastomoses are more common, the single-stapled approach is occasionally employed. This requires a purse string at both proximal and distal ends. One advantage of this technique is that the stapler can be advanced with the anvil in place, so it slides through the rectal stump more easily. Once at the top of the stump, the anvil is placed in the proximal bowel and the purse string snugged around the anvil stem. At the distal bowel, the trocar is deployed and the purse string is tied around it. The anvil and trocar are mated and the stapler fired as usual.

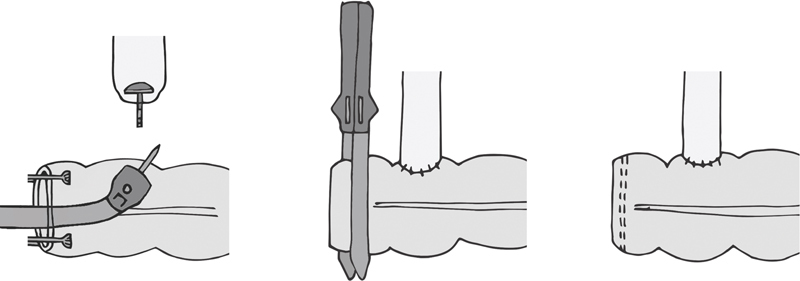

End-to-Side

This configuration is useful when joining bowel of different diameters ( Fig. 6 ). For an ileocolic anastomosis, it may also make future endoscopic intubation of the terminal ileum more feasible. To perform this, the bowel is resected as per routine. At the end of the proximal bowel, a purse-string suture is placed and the anvil tied down. Through the opening of the distal end, the stapler is advanced and the trocar is deployed through the side of the bowel. The trocar and anvil are attached, and the stapler is deployed. Both afferent and efferent limbs are checked for patency, and the staple line is inspected for hemostasis. The colotomy through which the stapler was introduced is closed with either a GIA or a TA stapler. At the surgeon's discretion, staple lines can be reinforced as discussed under side-to-side anastomosis.

Fig. 6.

Anastomotic configuration: end-to-side (end of ileum to side of colon).

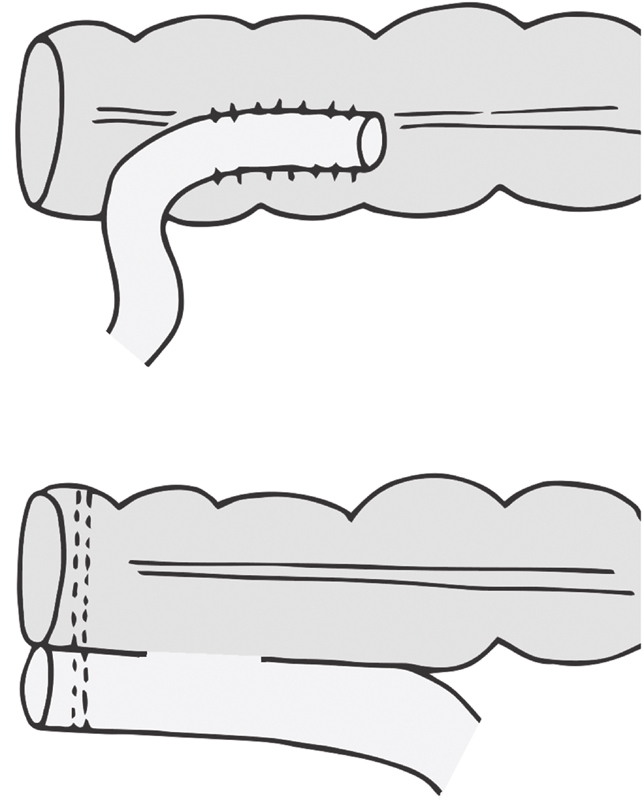

Side-to-End

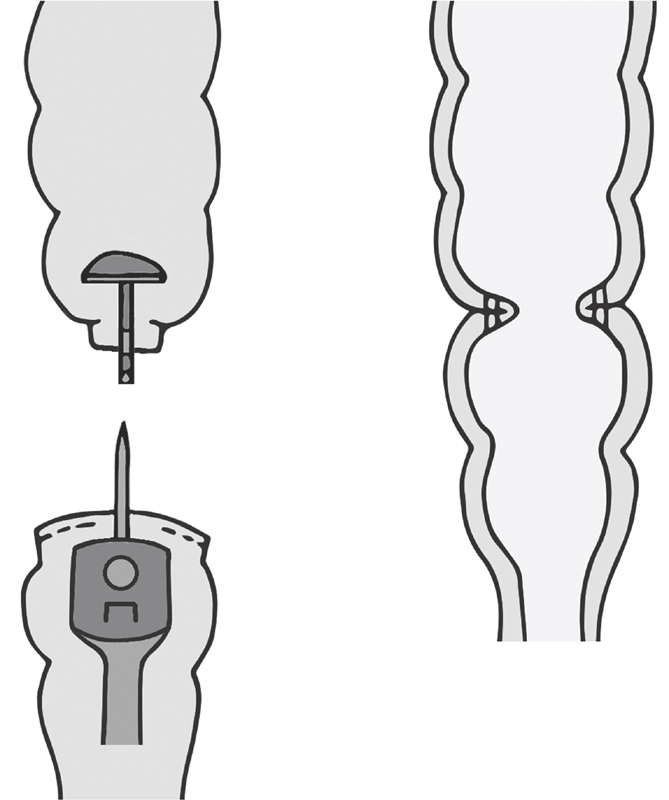

Baker described handsewn version in 1950, indicating its use in the setting of size discrepancy between the two bowel lumens to be joined. 36 Two options for stapling exist. In one, the end of the proximal bowel is left open, and the anvil stem is deployed through the side of the bowel ( Fig. 7 ). The removable spike that comes in the anvil facilitates this; it is removed once the anvil spike and stem have traversed the bowel wall. A purse string around the stem can be placed to ensure the bowel wall has no gaps. The open end of the proximal bowel is then stapled shut. The stapler is advanced to the top of the distal bowel and the anastomosis completed as in a stapled end-to-end fashion. Another option is to put a purse string at the top of the distal stump and tie the anvil there. Through the open end of the proximal bowel the stapler is placed, the trocar deployed through the wall, and the trocar and anvil mated. The remainder is similar, with closure of the proximal end of the bowel after ensuring no bleeding from the staple line. The optimal length of the side limb was studied, comparing a 3 versus 6 cm side limb. The study demonstrated no difference in clinically relevant bowel function. 37

Fig. 7.

Anastomotic configuration: side-to-end, the “Baker type” anastomosis (side of colon to end of rectum).

Conclusion

Bowel anastomoses can be fashioned in a variety of manners. Except for very specific conditions, such as ileoanal pouch anastomosis, there is conflicting data to support one modality over another. Rather than focusing on the materials and alignment, attention should be given to gentle tissue handling, eliminating tension, and anastomosing well-perfused tissues, as well as of avoiding anastomoses in high-risk patients and clinical settings.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.van Rooijen S J, Huisman D, Stuijvenberg M.Intraoperative modifiable risk factors of colorectal anastomotic leakage: why surgeons and anesthesiologists should act together Int J Surg 201636(Pt 0A):183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele S R, Hull T L, Read E Th, Saclarides T J, Senagore A J, Whitlow C B. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing; 2016. The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benlice C, Delaney C P, Liska D, Hrabe J, Steele S, Gorgun E. Individual surgeon practice is the most important factor influencing diverting loop ileostomy creation for patients undergoing sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Am J Surg. 2018;215(03):442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkatout I, Schollmeyer T, Hawaldar N A, Sharma N, Mettler L. Principles and safety measures of electrosurgery in laparoscopy. JSLS. 2012;16(01):130–139. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13291597716348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kann B R, Beck D E, Margolin D A, Vargas H D, Whitlow C B. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2018. Improving outcomes in colon and rectal surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnelly R, Hinwood D, London N J.ABC of arterial and venous disease. Non-invasive methods of arterial and venous assessment BMJ 2000320(7236):698–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbanavičius L, Pattyn P, de Putte D V, Venskutonis D. How to assess intestinal viability during surgery: a review of techniques. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3(05):59–69. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i5.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boni L, David G, Dionigi G, Rausei S, Cassinotti E, Fingerhut A. Indocyanine green-enhanced fluorescence to assess bowel perfusion during laparoscopic colorectal resection. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(07):2736–2742. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4540-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco-Colino R, Espin-Basany E. Intraoperative use of ICG fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(01):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen R, Zhang Y, Wang T. Indocyanine green fluorescence angiography and the incidence of anastomotic leak after colorectal resection for colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(10):1228–1234. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazio V W. Cancer of the rectum–sphincter-saving operation. Stapling techniques. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68(06):1367–1382. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rombeau J L, Collins J P, Turnbull R B., Jr Left-sided colectomy with retroileal colorectal anastomosis. Arch Surg. 1978;113(08):1004–1005. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1978.01370200098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sciuto A, Grifasi C, Pirozzi F, Leon P, Pirozzi R E, Corcione F. Laparoscopic Deloyers procedure for tension-free anastomosis after extended left colectomy: technique and results. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(12):865–869. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shariff U S, Kullar N, Dorudi S. Right colonic transposition technique: when the left colon is unavailable for achieving a pelvic anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(03):360–362. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182031e6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uraiqat A A, Byrne C M, Phillips R K. Gaining length in ileal-anal pouch reconstruction: a review. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(07):657–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho Y H, Ashour M A. Techniques for colorectal anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(13):1610–1621. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choy P Y, Bissett I P, Docherty J G, Parry B R, Merrie A, Fitzgerald A. Stapled versus handsewn methods for ileocolic anastomoses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(09):CD004320. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004320.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ANACO Study Group . Frasson M, Granero-Castro P, Ramos Rodríguez J L. Risk factors for anastomotic leak and postoperative morbidity and mortality after elective right colectomy for cancer: results from a prospective, multicentric study of 1102 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(01):105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordholm-Carstensen A, Schnack Rasmussen M, Krarup P M. Increased leak rates following stapled versus handsewn ileocolic anastomosis in patients with right-sided colon cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(05):542–548. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löffler T, Rossion I, Gooßen K. Hand suture versus stapler for closure of loop ileostomy–a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400(02):193–205. doi: 10.1007/s00423-014-1265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanz L E, Patterson J A, Kamath R, Willett G, Ahmed S W, Butterfield A B.Comparison of Maxon suture with Vicryl, chromic catgut, and PDS sutures in fascial closure in rats Obstet Gynecol 198871(3, pt 1):418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian F, Appert H E, Howard J M. The disintegration of absorbable suture materials on exposure to human digestive juices: an update. Am Surg. 1994;60(04):287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrle F, Diener M K, Freudenberg S. Single-layer continuous versus double-layer continuous suture in colonic anastomoses-a randomized multicentre trial (ANATECH trial) J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(02):421–430. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-3003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashash J G, Binion D G. Endoscopic evaluation and management of the postoperative Crohn's disease patient. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2016;26(04):679–692. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibáñez N, Abrisqueta J, Luján J, Hernández Q, Rufete M D, Parrilla P. Isoperistaltic versus antiperistaltic ileocolic anastomosis. Does it really matter? Results from a randomised clinical trial (ISOVANTI) Surg Endosc. 2019;33(09):2850–2857. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S. Isoperistaltic versus antiperistaltic stapled side-to-side anastomosis for colon cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res. 2015;196(01):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarta C, Bishawi M, Bergamaschi R. Intracorporeal ileocolic anastomosis: a review. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17(05):479–485. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-0998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamali F R, Soweid A M, Dimassi H, Bailey C, Leroy J, Marescaux J.Evaluating the degree of difficulty of laparoscopic colorectal surgery Arch Surg 200814308762–767., discussion 768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allaix M E, Degiuli M, Bonino M A. Intracorporeal or extracorporeal ileocolic anastomosis after laparoscopic right colectomy: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270(05):762–767. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neutzling C B, Lustosa S A, Proenca I M, da Silva E M, Matos D. Stapled versus handsewn methods for colorectal anastomosis surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(02):CD003144. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003144.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirat H T, Remzi F H, Kiran R P, Fazio V W.Comparison of outcomes after hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in 3,109 patients Surgery 200914604723–729., discussion 729–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovegrove R E, Constantinides V A, Heriot A G. A comparison of hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) following proctocolectomy: a meta-analysis of 4183 patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244(01):18–26. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225031.15405.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) Collaborative . Kwon S, Morris A, Billingham R. Routine leak testing in colorectal surgery in the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Arch Surg. 2012;147(04):345–351. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricciardi R, Roberts P L, Marcello P W, Hall J F, Read T E, Schoetz D J.Anastomotic leak testing after colorectal resection: what are the data? Arch Surg 200914405407–411., discussion 411–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fazio V W, Heriot A G. Proctectomy with coloanal anastomosis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2005;14(02):157–181. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker J W. Low end to side rectosigmoidal anastomosis; description of technic. Arch Surg. 1950;61(01):143–157. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1950.01250020146016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsunoda A, Kamiyama G, Narita K, Watanabe M, Nakao K, Kusano M. Prospective randomized trial for determination of optimum size of side limb in low anterior resection with side-to-end anastomosis for rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(09):1572–1577. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a909d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]