Graphical abstract

Keywords: Emulsion Gels, Turbulent Flow, Colloidal Particles, Ultrasound

Abbreviations: TIEG, turbulence-induced emulsion gel; CP, colloidal particle; HIPE, high-internal phase emulsion; HILF-US, high-intensity low-frequency ultrasound; HPH, high-pressure homogenization; GO, graphene oxide; rGO, reduced graphene oxide; OF, oil fraction; UT, Ultra-Turrax; SFO, sunflower oil; BMC, bovine micellar casein; WPI, whey protein isolate; WPP, whey protein particle; SC, sodium caseinate; rMC, reconstituted micellar casein; SPI, soy protein isolate; PPI, pea protein isolate; WIL, water-immiscible liquid

Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound-generated turbulence is used to generate stable emulsion gels.

-

•

A new mechanism for producing stable emulsion gels is proposed.

-

•

Inter-droplet bridging and void filling by colloidal particles are crucial to generate stable emulsion gels.

-

•

The properties of emulsion gels could be tailored for specific applications.

Abstract

Emulsion gels have a wide range of applications. We report on a facile and versatile method to produce stable emulsion gels with tunable rheological properties. Gel formation is triggered by subjecting a mixture containing aqueous colloidal particle (CP) suspensions and water-immiscible liquids to intense turbulence, generated by low frequency (20 kHz) ultrasound or high-pressure homogenization. Through systematic investigations, requisite gel formation criteria are established with respect to both formulation and processing, including ratio/type of liquid pairs, CP properties, and turbulence conditions. Based on the emulsion microstructure and rheological properties, inter-droplet bridging and CP void-filling are proposed as universal stabilization mechanisms. These mechanisms are further linked to droplet-size scaling and sphere close-packing theory, distinctive from existing gel-conferring models. The study thereby provides the foundation for advancing the production of emulsion gels that can be tailored to a wide range of current and emerging applications in the formulation and processing of food, cosmetics or pharmaceutical gels, and in material science.

1. Introduction

Emulsions are an important class of materials with a broad range of applications. They comprise two immiscible liquids and commonly have a bulk liquid texture. Research on emulsion texturization has surged in recent decades. In particular, it can be desirable to produce emulsions with gel-like consistencies for a wide range of applications across food science [1], cosmetics [2], [3], pharmaceuticals [4], and material science [5]. While emulsion gel formation has been observed across both biopolymer and inorganic systems, mechanistic understanding remains fragmented. Various triggers for emulsion gel formation have been identified at different dispersed phase volume fractions. At low volume fractions , gelation of the continuous phase is a common approach to texturize liquid emulsions, for example, by producing hydrogels/organogels in which the dispersed phase droplets are imbedded [1], [6]. At higher dispersed phase fractions, the droplets themselves can form networks that confer a gel-like consistency. In this case, droplet flocculation via bridging or depletion mechanisms can lead to macroscopic gel-like textural properties in concentrated emulsion systems [7], [8], [9]. Finally, high-internal phase emulsion (HIPE) gels have a dispersed phase fraction that is typically higher than the continuous phase, starting from about 0.6 [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. In this case, droplet close-packing models have been used to explain gel formation. Interfacial stabilizers also play an important role in emulsion gel formation. Apart from stabilizing newly created droplet interfaces, interactions amongst stabilizers or stabilized droplets, such as crosslinking and aggregation, can contribute to the macroscopic rheological properties (e.g. hydrogels and polymeric HIPEs). Particle-stabilized emulsion systems, namely Pickering emulsions, involve mesoscopic to submicron-sized colloidal particles (CPs) as the main stabilizing agent in place of molecular surfactants. Amongst many potential CP interactions, interfacial bridging/sharing between droplets by the CP monolayer has been proposed to be the key mechanism for colloidal emulsion gel formation over a wide range of dispersed phase fractions [16], [17], [18].

The role of turbulence in producing liquid emulsions has been long understood, yet at the same time, it has been largely overlooked regarding its effect on emulsion texturization. More recently, a growing number of studies have reported turbulence-related formation of gel-like emulsions using polymeric/inorganic particle stabilizers [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. Interestingly, high-intensity emulsification methods, such as ultrasonication and high-pressure homogenization, have repeatedly been employed, yet seldomly investigated. Instead, the textural transition has been commonly reasoned in relation to the established gel formation mechanisms mentioned above. Of relevance to this study, there has historically been an emphasis on understanding the particle interfacial wetting behavior and inter-droplet bridging in particle-stabilized emulsions, which have largely overshadowed the effect of turbulence.

In this work, we report for the first time the criteria for the rapid formation of turbulence-induced emulsion gels (TIEGs) across a wide range of water/water-immiscible liquid pairs, stabilized by suspensions of biopolymeric or inorganic colloidal particles. The universal trigger for this type of emulsion gel formation was found to be intense turbulence, which could be generated by high-intensity low-frequency ultrasonication (HILF-US) or high-pressure homogenization (HPH). In contrast, the less intensive turbulence imparted by rotor–stator mixing was insufficient for TIEG formation. It was observed at a microscopic level that all TIEGs had droplets of order 10-1-101 μm, which could be related to a fractal close packing model involving both colloidal particle stabilizers and emulsion droplets. By collecting evidence from the microstructure and rheological behavior of TIEGs obtained from a wide variety of CP systems, we have proposed a universal mechanism for TIEG formation. Finally, a range of potential applications was explored to demonstrate the versatile platform-like capabilities of TIEGs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Bovine micellar casein and whey protein isolate were obtained by microfiltration as reported elsewhere [30]. Soy protein isolate (Premium Powders Pty Ltd), pea protein isolate (True Protein Pty Ltd), titanium dioxide (P25, ≥99.5%, 21 nm primary particle size, Sigma-Aldrich), two graphite materials (synthetic powder, <20 µm, Sigma-Aldrich; and natural flakes, −325 mesh, Sigma-Aldrich), chitosan (from shrimp shells, ≥75% deacetylated, Sigma-Aldrich), sodium caseinate (SC, Sigma-Aldrich), gold(III) chloride trihydrate (≥99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich), cyclohexane, decane, dodecane, tetradecane and hexadecane (≥99% for all alkanes, Sigma-Aldrich), sunflower oil, skim milk powder, butter (local supermarket), polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR, Palsgaard A/S), single-layer graphene oxide suspension (SKU# GNO1W001, 10 mg mL−1, ACS Material, LLC) were used as received. Analytical grade chemicals, including sodium chloride, L-ascorbic acid, potassium permanganate, sulfuric acid, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, tri-potassium citrate, calcium chloride, dipotassium phosphate, were obtained from Chem-Supply. Milli-Q water was used in all experiments.

2.2. Colloidal particle suspensions fabrication

The general method for producing natural CP suspensions involves suspending dry CP materials in Milli-Q water. Briefly, suspensions of BMC (protein concentration 10 – 100 mg mL−1), skim milk powder (casein concentration 100 mg mL−1), SPI and PPI (100 mg mL−1), P25 (100 mg mL−1) were prepared by simple water dispersion with sufficient CP hydration process (e.g. constant stirring). Following methods were applied to convert the raw materials into their CP form. For heat-unstable, water-soluble proteins such as whey protein isolate, the as-prepared aqueous solution (50 mg mL−1) was subjected to heat treatment (e.g. 85 ˚C for 30 min) to produce the whey protein particulate suspension. pH-shifting was performed on acidic chitosan solution (HCl, pH = 4) under vigorous stirring by adding concentrated NaOH solution (to avoid excessive dilution) until its isoelectric point (pH = 6.5) was reached, after which the clear solution became cloudy with apparent aggregates. The size of the chitosan aggregates was then reduced via ultrasonication (calorimetric power 30 W, 5 min sonication with ice bath) until a uniform turbid colloidal suspension was formed.

Micellar casein reconstitution was carried out using a previously reported method[31]. Briefly, 200 mL of 50 mg mL−1 sodium caseinate solution was mixed with 4 mL of 1 M tri-potassium citrate, 24 mL of 0.2 M K2HPO4 and 20 mL of 0.2 M CaCl2. Subsequently, another 8 sequential additions of 2.5 mL of 0.2 M K2HPO4 and 5 mL of 0.2 M CaCl2 were made at 15 min intervals. The process was undertaken under constant stirring at 37 °C, while the pH was maintained around 6.7 to 7. The volume of the final reconstituted micellar casein (rMC) colloidal suspension was then increased to 400 mL by adding water, the pH was adjusted to 6.7, and the suspension was stirred for another 1 h, resulting in a final rMC concentration of 25 mg mL−1.

The fabrication of GO suspension followed the described method [32] with modifications [33] using two graphite materials. Briefly, with the same quantities of precursors (3 g graphite powder, 70 mL concentrated H2SO4, and 9 g KMnO4), the oxidation process was set to 40 ˚C, 8 h after the water addition step. The suspension was subjected to dialysis (molecular weight cut-off 14 kDa) for one week after repeating washing cycles using 5% HCl solution and water. Ultrasonic exfoliation was conducted after dialysis for 30 min (20 kHz, input power 200 W, pulse mode, 20-s on and 10-s off duty cycle, ice bath), after which the suspension was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min to remove unexfoliated particles and then freeze-dried. As-prepared GO powder was redispersed in Milli-Q water (up to 15 mg mL−1) for direct use as CP. Alternatively, commercial single-layer GO suspension (10 mg mL−1) was used for TIEG formation without purification. Partially reduced GO suspensions were prepared by introducing L-ascorbic acid with an ascorbic acid:GO ratio of 10:1 (w/w) [34]. The suspension was vortexed and incubated at 60 ˚C for 20 and 35 min, before subjecting to TIEG formation. Fabrication of CPs has not been discussed in the main text, however provided in the supporting information.

2.3. TIEG formation

The formation of TIEGs for all reported systems involved 1) pairing an aqueous CP suspension with oil, or water-immiscible liquid (WIL) at oil fraction (OF) 0.5 (v/v), and 2) subjecting this mixture to emulsification using either HILF-US or HPH (requires a coarse liquid emulsion by rotor–stator pre-emulsification), after which TIEGs can be directly obtained without additional ingredients or steps. The effect of WIL type on TIEG formation was examined using cyclohexane, decane, dodecane, tetradecane and hexadecane, and sunflower oil (SFO). Melted butterfat was used for application demonstration.

For HILF-US and HPH approaches, the total energy density input was at the low-medium level compared to the maximum capacity of the two technologies. Small-volume samples (10 – 20 mL) for characterization proposes, for example, can be formed within 30 – 60 s of sonication (Branson Digital Sonifier, Model No. 450, nominal power 400 W) at a calorimetric power level of 23 W (12 mm tip, 20 kHz. consistent tip position and container geometry), resulting in an energy density input around 40 – 80 J mL−1. Alternatively, a single-stage/pass homogenization (PandaPLUS 1000, GEA Niro Soavi, Parma, Italy) was performed with a fixed pressure at 40 MPa on the pressure valve with a constant flow rate of 2.77 mL/s to achieve continuous process at a larger sample volume level (starting from 0.2 L). Excessive energy density input (up to 1000 J mL−1) has been applied for rotor–stator mixing using Ultra-Turrax (UT, T25, IKA-Labortechnik) for comparison. The OF effect was investigated by varying OF from 0.1 − 0.9 between UT and HILF-US following the same formation protocol (i.e. combining a liquid pair and subjecting to turbulent homogenization).

2.4. Fabrication of TIEG-derived architectures

Aerogels were fabricated from TIEGs made with WILs, which are removable via freeze-drying, such as low carbon number alkanes (C6 – C12), with the same emulsification protocol. The microstructure of TIEG samples was fixed by liquid-nitrogen freezing for 30 min, followed by vacuum freeze-drying at −50 ˚C for 72 h to remove the liquid pairs. Oleogels were produced from TIEGs with non-evaporative WILs by moisture removal, which can be further fractured into oil sands/granules.

The method of introducing guest components into TIEGs and aerogels can vary. At the emulsion gel stage, water-in-oil-in-water double emulsion gels can be formed by replacing the WIL with a primary water-in-oil (W/O). Briefly, the primary W/O emulsion consists of water-SFO liquid pair at an OF = 0.75, which contains 0.5% (w/w) PGPR and 20 mg mL−1 NaCl in oil and aqueous phase, respectively. The primary emulsion was subjected to sonication for 10 min (ice bath for maintaining room temperature) at a calorimetric power of 30 W. The double emulsion gel was prepared with 100 mg mL−1 BMC as the CP suspension and the as-prepared primary W/O emulsion with a 1:1 vol ratio. To incorporate guest components in aerogels, multiple pathways could be taken depending on the desired systems and applications, from which we demonstrated two approaches. In the case of gold (Au) nanoparticle (NP)-embedded chitosan aerogels, the guest component was introduced in the format of Au(III) ions. Briefly, an aliquot of 2 mM gold chloride solution was introduced into NaOH solution (1:9), which was further consumed in the chitosan pH-shifting treatment described above. Consequently, ultrasonic particulation was carried out in an ice bath to prevent the reduction of Au(III), which resulted in the formation of Au(III)-chitosan CP suspension. The early introduction of Au(III) showed no significant impact on TIEG and aerogel formation. As a result, Au(III)-chitosan aerogels are successfully obtained. The in-situ reduction of Au(III) to Au NPs was achieved by thermal reduction at 100 ˚C. In GO-P25 aerogel system, GO (10 mg mL−1) and P25 (100 mg mL−1) suspensions were properly mixed (3:1 v/v) and subjected to the subsequent TIEG and aerogel preparation (cyclohexane, OF = 0.5 v/v). Thermal treatment was conducted for GO aerogel systems at 300 ˚C for 1.5 h [35] to increase the reduction level of GO.

3D printing of the GO TIEG was carried out using 3D-Bioplotter (EnvisionTEC, Inc.). Briefly, as-prepared TIEG (ascorbic acid-reduced GO-cyclohexane, 10 mg mL−1) was loaded in the fluid dispensing system (Optimum® syringe barrel, 30 cc and 0.41 mm tip, Nordson Corporation). A 20 mm × 20 mm area with a grid printing pattern was used, where TIEGs were dispensed at a printing speed of 40 mm/s and pressure of 0.4 bar at room temperature (22 ˚C for both the low-temperature print head and print stage). The same aerogel fabrication process was conducted for producing 3D-printed aerogels.

2.5. Characterization of physicochemical properties of CP suspensions and emulsions

CP size was measured by dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano S90, 633 nm laser, Malvern) and laser diffraction (Mastersizer 3000, with Hydro EV dispersion system, Malvern) depending on suspension volume and turbidity. For Zetasizer measurements, samples were subjected to dilution, centrifugation, and ultrasonication (45 kHz ultrasonic bath, Branson) to avoid excessive aggregation. For Mastersizer measurements, laser obscuration from sample introduction was controlled in the range of 5–10%. Software default refractive indices of proteins, chitosan, P25 and GO were applied for CP suspension sizing (1.45, 1.53, 2.49, and 1.957, respectively). The average size of CPs was expressed as z-average or volume-mean diameter (D4,3) corresponding to the two sizing approaches, and volume-based size distributions were presented for CPs. A refractive index of 1.47 (SFO) was used for liquid emulsion measurements (Matersizer). Number size distributions were recorded for turbulence condition estimation amongst UT, HILF-US and HPH (supporting information).

The storage (G’) and loss (G’’) moduli were probed with an AR-G2 rheometer (TA Instruments) using a 40 mm 2° steel cone (988134) as the upper mounted probe and a temperature-controlled plate as the lower stage. An oscillatory strain sweep from strain, γ = 0.01–1000% at a constant frequency of 1 Hz was performed. The zero-shear elastic modulus (G0′) was calculated based on the average value obtained within the linear viscoelasticity region (LVER). The viscosity of the samples was measured as a function of increasing shear rate from 0.1 to 100 s−1 at 25 °C using the same geometry setup.

Dynamic interfacial tension was examined amongst selected CP (10 mg mL−1), including BMC, SC, SPI, PPI, chitosan (colloidal particles and solution at pH = 6.5 and 4, respectively), WPP and WPI, P25 and GO. The pendant drop method was applied using OCA 15EC system (DataPhysics Instruments GmbH). The pendant drop was formed by automated injection of CP suspension/water into SFO as the WIL, loaded in the 1 cm cuvette. A live video of the drop was recorded, and the interfacial tension (IFT) was calculated from the captured drop image with the automatic edge extraction and Young-Laplace equation fitting by the software (SCA 20). From the time point of the drop creation, data acquisition in intervals was employed using the tracking function. Noted that a significant IFT reduction occurred in BCPs from the first recording right after the formation of pendant drop, surface pressure () was calculated based on IFT values between the pure liquid pair (i.e. water-SFO, ) and CP-SFO at given recording time (, ), and plotted as the function of drop age (t).

2.6. Microstructural analysis of TIEGs and aerogels

Optical microscopic images of emulsion samples were taken using an inverted Olympus IX71 wide-field fluorescence microscope with a × 60 objective lens. The images were captured by a CCD camera (Cool SNAP fx, Photometrics, Tucson). For confocal microscopy, biopolymeric CP-SFO TIEGs (BMC, SPI, WPP and rMC) were prepared with SFO containing pre-dissolved Nile red dye (Sigma Aldrich). After TIEG formation, gel samples were transferred onto microscope glass slides, after which 2 drops of Fast Green solution (2 mg/mL in water, Sigma Aldrich) were applied to the surface of samples for staining the proteins in the aqueous phase. The staining of FG was set for 5 min, after which the excess dye solution was carefully removed by filter papers. Finally, the samples were covered with a coverslip. Confocal microscopic images were acquired using Leica SP5, where the fluorescence emission was captured through a 60 × lens using photomultiplier tubes set at 500–600 nm (Nile red emission) and 655–755 nm (Fast Green emission). The color of aqueous and WIL channels was adjusted by ImageJ after image acquisition. The in-situ cellular structure, interfacial rearrangement and morphology of CP aerogels were investigated using scanning electron microscopy (Teneo VolumeScope, FEI). Aerogels were subjected to the SEM imaging protocol, in which gold sputtering was performed on non-conductive BCP aerogels. The thickness of CP scaffolds was measured via ImageJ from the SEM images.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All TIEG formation criteria experiments were conducted with triplicates with representative data presented. Characterizations were measured in triplicates with representative data presented. The mean and the standard deviation were calculated based on the replicates. One-way ANOVA was conducted for the statistical significance analysis with p = 0.05 and Fisher’s test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Universal transitions triggered by turbulence

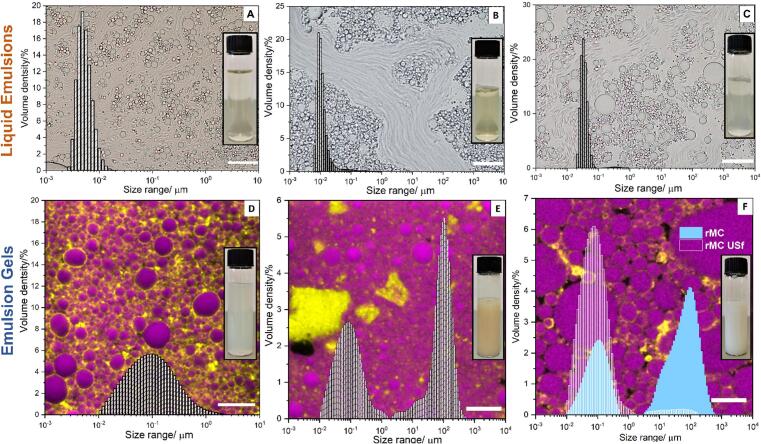

The liquid-gel transition under turbulent flow is illustrated in Fig. 1 using bovine micellar casein (BMC), a class of natural biopolymeric colloidal particles (BCPs), and two common types of inorganic colloidal particles (ICPs) – TiO2 nanoparticles (P25) and graphene oxide (GO). Although these colloidal particles have distinctively different physicochemical properties, the resulting emulsion texture (see Figure S1 for rheological results) can change from free-flowing liquids to paste-like, highly viscous emulsion gels solely depending on the emulsification method. In particular, it is the intensity of localized turbulence that is important, rather than the overall bulk energy consumption (see SI for definition), as the total energy input of Ultra-Turrax (UT) per unit volume mixing was much higher (600 J mL−1, 10 min of mixing) than that of the HILF-US (60 J mL−1, 60 s sonication). Microscopically, high-intensity turbulence resulted in greater droplet size reduction and inter-droplet jamming. Interestingly, a similar manifestation can be found using a wide range of colloidal stabilizers when subjected to a similar HILF-US treatment (Table S1). This outcome indicates that the turbulence triggered oil-in-water emulsion gel formation could be a universal phenomenon in emulsion systems involving colloidal particle stabilizers.

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of the need for high-intensity turbulence to trigger emulsion gel formation, with examples using three types of colloidal stabilizers. Comparison of the microstructure and bulk texture of emulsions formed at prolonged low-intensity emulsification using an Ultra-Turrax (UT) rotor–stator mixer (A, B and C, respectively), and a short pulse with high-intensity emulsification using high-intensity low-frequency ultrasound (HILF-US, also achievable using high-pressure homogenization, HPH) (D, E and F, respectively). Sunflower oil (SFO) was the oil phase at 0.5 v/v. Optical microscopic images of microstructures of emulsions stabilized by bovine micellar casein (BMC) (100 mg mL−1), TiO2 particles (P25, 100 mg mL−1), and graphene oxide (GO) (10 mg mL−1) are presented in the left (A and D), middle (B and E) and right (C and F) columns, respectively. Scale bars: 20 µm. Macroscopic representations (images) of the gels are presented as inserts.

3.2. Experimental criteria of TIEG formation

The requisite criteria of TIEG formation were then extensively investigated. Based on the experimental outcomes across all tested emulsion systems, the formation of TIEGs is related to 1) the size of colloidal particles (CPs), 2) oil fraction (OF) and type, and 3) turbulence intensity. The universal TIEG formation amongst a wide variety of CP candidates became an intriguing observation as it leveraged CPs with divergent chemical constitutions and no conventional gelling factors. We found that these CP candidates shared similar physical properties, in which the importance of CP size was apparent, with all TIEGs showing ‘turbid’ suspensions rather than ‘clear’ solutions. More specifically, the volume-mean diameter (D4,3) of the tested CPs was found to be > 0.1 µm (Table S2). For example, emulsions made using whey protein isolate (WPI) remained as liquids (Fig. 2A). However, after converting WPI into whey protein particles (WPP, Fig. 2D), TIEGs were obtained. Similar micro-/macroscopic liquid-gel transition behavior was observed for sodium caseinate (SC, liquid emulsion Fig. 2C) versus reconstituted micellar casein (rMC, TIEG Fig. 2F), and soy protein isolate (SPI, liquid emulsion Fig. 2E) versus its clear supernatant (TIEG Fig. 2B). The size dependence also applies to ICPs. Nano-sized TiO2 could form TIEGs, whereas micron-sized TiO2 could not (Figure S2). The thickness and size of the 2D GO sheets likewise affected TIEG formation, with a higher degree of exfoliation found to promote gel formation (Figure S3). When comparing single/few-layer GO suspensions, a larger sheet size/area yielded stronger gels (Figure S3). It is worth noting that converting small biopolymers to their submicron particles for stabilizing Pickering emulsions is a popular approach, in which some have reported liquid-gel transitions [14], [21], [22], [36], [29]. However, discussions in these studies were largely biased to specific interactions, whereas the obvious size alteration was commonly neglected. In contrast to the strong dependence of TIEG formation on CP size, there was no apparent dependence on the interfacial properties of CPs. The dynamic interfacial tension of various successful/unsuccessful candidates was found to overlap (Figure S4). Overall, proteins offered greater interfacial stabilization compared to polysaccharides and inorganic CPs, due to their ability to undergo complex interfacial rearrangements [37], regardless of their size (e.g. WPI/WPP and SC/BMC),

Fig. 2.

Microstructure of liquid emulsions (top row) and emulsion gels (bottom row) produced by HILF-US emulsification. Superimposed are the volume size distributions of the corresponding colloidal particle (CP) stabilizers and images of the clear (top row) and turbid (bottom row) suspensions. Optical microscopic images of liquid emulsions under long exposure (200 ms) prepared with WPI (A, 50 mg mL−1), SPI supernatant (B, 25 mg mL−1), and SC (C, 50 mg mL−1), where fast-moving droplets became blurred. Confocal microscopic images of WPP (D, 50 mg mL−1), SPI (E, 100 mg mL−1) and rMC (F, 25 mg mL−1) emulsion gels. (F) Size distributions of rMC suspension before (solid-blue symbol) and after (rMC USf, open-white). Scale bars: 20 μm (A, B, C, and F) and 10 μm (D and E).

TIEG formation was found to occur within an OF range of 0.4–0.6 v/v. At lower OF (<0.3), low-viscosity liquid emulsions with partial inter-droplet clustering were typically observed (Fig. 3A). Above the OF window, rapid phase inversion (oil-in-water to water-in-oil) occurred (Fig. 3E), resulting in rapid phase separation (Figure S5). It is worth noting that low-intensity mixing yielded no significant gel formation across the entire OF span (Fig. 3G). The lack of gel-like texture above OF ∼ 0.6 differentiates our observations from the reported HIPE gels, which generally require a dispersed phase fraction > 0.6 v/v [10], [12], [13], [14], [15], [38]. In addition, such strong OF dependence observed in TIEGs can be distinguished from the reported colloidal gel formation[17], [26], in which G0′ was shown to be independent of the dispersed phase fraction. Properties of oils or water-immiscible liquids (WILs) could affect the dynamics of droplet breakup[39], [40]. However, their effects on such emulsion gel formation are unknown. We examined TIEG formation using a series of alkanes (Section 2.3). As shown in Fig. 3I, increasing alkane carbon number was found to either determine TIEG formation (e.g. GO-alkane), or to enhance gel viscoelasticity (e.g. chitosan-alkane) further. It is speculated that the increased viscosity/density of WILs with higher carbon numbers improves TIEG formation by mitigating droplet deformation, coalescence, and aqueous syneresis, which would destabilize the gels. The result is consistent with the high stability of TIEGs formed with relatively viscous/dense triglycerides (e.g. SFO, Figure S1).

Fig. 3.

Dependence of TIEG formation on the oil fraction and type. Optical microscopy images of BMC-SFO emulsions (10 mg mL−1) subjected to HILF-US emulsification (70 J mL−1, A, C and E) and UT (300 J mL−1, B, D, and F) at OF = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.7. Visualization of the macroscopic texture difference of emulsions formed by HILF-US and UT at OF = 0.5 (G). Scale bars: 20 µm (A – D), 200 µm (E and F) and 1 mm (G). Strain oscillatory sweep profiles (H) of BMC-SFO emulsions (HILF-US) within 0.01 – 1000% oscillating strain (γ) of emulsions at OF = 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6 and 0.7 (G’ and G’’ represented with closed and open symbols, respectively). Zero-shear elastic moduli (G0′) of GO (10 mg mL−1, grey columns) and chitosan (pH = 6.5, 20 mg mL−1, white columns) emulsions (I, OF = 0.5 v/v) prepared with cyclohexane, dodecane and hexadecane. The picture insert shows the texture of corresponding GO-alkane emulsions (left to right, cyclohexane, dodecane and hexadecane, 20 J mL−1, 3 mm HILF-US microtip).

The facile and rapid liquid-gel transition under intense turbulence is of great interest. Apart from HILF-US, which enables TIEG formation, single-stage high-pressure homogenization (HPH) was found to be successful for TIEG formation. Despite the different working principles [41], [42], [43] and modes of operation for HPH (flow-through) and HILF-US (tested with batch mode), similar rheological properties and emulsion microstructures can be obtained (Figure S6, Movie S1). The consistent outcome for ultrasonication and HPH reveals that the mechanism responsible for TIEG formation is the same, namely, the extreme level of turbulence, rather than the chemical effects generated by cavitation. Although there are a number of studies that could be relevant to the occurrence of TIEGs [17], [20], [21], [22], [26], [27], [29], [36], [44], [45], it is noticed that the role of turbulence during emulsification on emulsion textural transition lacks explanation (Table S3). We estimate the energy dissipation rate and turbulent eddy size amongst UT, HILF-US and HPH using a model emulsion system (Supporting Information) to highlight the importance of turbulence intensity on TIEG formation [39], [46], [47], [48]. At a low OF level, HILF-US and HPH are known to produce stable nanoemulsions [39], [49]. At the same energy density level (40 J mL−1), the smallest turbulent eddy size (Figure S7) of HILF-US and HPH is situated at around 0.2 µm, which is three times smaller than UT (0.6 µm). Correspondingly, the energy dissipation rate of HILF-US and HPH falls within the reported range of 108 –109 W kg−1 for low-viscosity nanoemulsion systems[39], [46], whereas the value of UT was much lower, in the order of 106 W kg−1. As presented above, such a difference in turbulent energy intensity cannot be compensated by the total energy input level (Fig. 1, Fig. 3). In addition, the residence time in both HILF-US and HPH process is extremely short (in the order of seconds), compared to other conventional emulsion gelation/aggregation processes triggered, for example, by centrifugation [50], aqueous self-aggregation [24], heating [23], pH [51], enzyme treatment [52], or chelation [53]. Together, we emphasize that the turbulent field not only governs the droplet breakup kinetics but also plays a critical role in altering the microstructure and macroscopic texture of a given emulsion system.

3.3. Mechanistic investigation of TIEG formation

We can bring together the experimental findings discussed above to develop further mechanistic understandings of the TIEG formation phenomenon. It should be noted that all successful emulsion systems had a consistent microstructure, comprised of close-packed, polydisperse, CP-stabilized droplets, typically 10-1-101 µm in diameter. The microstructure of an emulsion must be relatable to its macroscopic rheological properties. In particular, the ability of an emulsion to flow (i.e. behave as a liquid) relies on the droplets being able to move in relation to one another. Therefore, the reasons for the reduced mobility of droplets and CP in TIEGs should rely on their microstructural alteration, which could reveal the fundamental mechanism in relation to turbulence and CP properties. We propose two interdependent modes of structural stabilization provided by the CPs – inter-droplet bridging (IDB) and colloidal particle void filling (CVF). These can correspond to immobilization between and around the droplets in the primary domain of the dispersed phase and continuous phase, respectively.

3.3.1. Occurrence of IDB in TIEGs

First, the layer of interfacially-adsorbed CPs provides a barrier between droplets that prevents droplet–droplet coalescence. When droplets are in close proximity, adjacent droplets could share a monolayer or a bilayer of the stabilizing CP, forming IDB sites [17], [18], [27], [54]. The number of IDB sites increases with the droplet size reduction, which would affect the macroscopic texture of an emulsion [27]. Compared to rigid solids, interfacial deformation and preferential wetting of microgel particles could also occur to govern droplet coalescence, hence emulsion stability [55], [56], [57], [58]. On top of these ideas, we found that the establishment of IDB could be further developed based on CP properties. In particular, the CPs in the following example systems were able to support IDB between droplets across a wide length scale, spanning 10-3-100 µm.

To probe the microstructural stabilizing role of CP, aerogels were produced from TIEGs in which volatile WIL and water were evaporated to leave behind intact and observable CP scaffolds (Section 2.4). BCPs generally are highly deformable upon interfacial adsorption due to their polymeric and polyelectrolytic nature. For example, we found that BMC underwent a transition from individual spheres in aqueous environments (Figure S8) into a continuous 3D cellular scaffold around the droplets (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the wall thickness near the tangent of two droplets, which was expected to be the major site of IDB, was only about 20–30 nm, considerably thinner than the typical diameter of hydrated casein micelles (50–300 nm). Correspondingly, the 2D sheets of single-layer GO demonstrated a high degree of interfacial flexibility, resulting in the development of 3D cellular microstructures that are more polygonal-deformed (Fig. 4B). Compared to BMC, a robust network of IDB could be established by a very thin layer of 2D sheets (Fig. 4E). Amongst all the CPs reported in this work, only P25 were non-deformable solid particles. However, as mentioned above, P25 are generally present as aggregates in aqueous suspensions (Figure S2 and Table S2), which can deform based on rearrangements of the individual rigid nanoparticles. Microscopic observation of P25 aerogels suggested that the IDB was achieved by dense P25 interfacial wetting and the attractive clustering of individual P25 particles (Fig. 4I), with a wall thickness from 0.4 µm to over 1 µm (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

SEM images of microstructures of TIEG-derived from BMC-cyclohexane (100 mg mL−1) (A and D), GO-dodecane (15 mg mL−1) (B and E) and P25-dodecane (100 mg mL−1, 60 mM NaCl) aerogels (C and F). The estimated wall thickness of IDB was approximately 101, 100 and 102 nm, respectively. The effective IDB unit was speculated to be single-layer interfacially-deformed BMC films (indicated by arrows, D), thin layers of GO sheets (E), and deformed clusters of P25 (F), corresponding to the schematic illustrations (G-I). Scale bars: 5 µm (A and B), 50 µm (C), 500 nm (D and E), and 20 µm (F).

As mentioned earlier, the presence of droplet bridging is common in many Pickering emulsion systems stabilized either by deformable or non-deformable particles. The results shown in these TIEGs provided additional insights in both the length scale (i.e. 10-3 – 100 µm) and the dimensions of the effective bridging units (i.e. deformable protein particles, 2D GO sheets or P25 clusters, Fig. 4G-I, respectively). Although effective IDB could reduce inter-droplet recoalescence and improve emulsion stability, IDB could generally occur in many jammed emulsion systems regardless of the droplet size and stabilizer types. Therefore, the strong CP size and turbulence dependence on TIEG formation could not be reasoned clearly solely based on this stabilization mode.

3.3.2. Stabilization of continuous phase by CVF

This leads to the discussion of colloidal particle void filling (CVF), the stabilization mode relating to the presence of CP within the continuous phase of TIEGs. Compared to IDB, the occurrence of CVF is expected to occur only if the CPs are large enough to act as another group of ‘spheres’ that contribute to the overall packing density by filling the inter-droplet voids. This can be illustrated by considering a 2D Apollonian packing model, in which inter-droplet voids are filled with progressively smaller tangent droplets, connected via IDB, until reaching an iteration in which CPs could act as the fillers (Fig. 5A–C). Experimentally, the transition observed in the microstructure of PPI aerogel scaffold (Fig. 5E) resembles this packing arrangement, with the CP scaffold gradually thickening when approaching a void center.

Fig. 5.

Connection between 2D Apollonian gasket model (A-C) and microstructural evidence (D and E) of CVF stabilization in TIEG. Schematic diagram of the fractal-like close packing based on three consecutive filling iterations starting from three mother droplets with IDB configuration, including two IDB steps (A and B) and the appearance of CVF in the third void filling iteration (C). The diameters of IDB droplets and CPs undergo CVF (before deformation, indicated with light blue dashed circle) were calculated and labeled correspondingly (in microns) based on a given diameter (10 µm) of the three mother droplets, resulting in the overall reduction of length scale from 101 – 10-1 µm. In SEM images of a PPI (PPI-cyclohexane, 100 mg mL−1, OF = 0.5 v/v) aerogel, the extremely thin IDB sites exhibit web-like networks, which could be due to the damage caused by the freeze-drying process (D). A higher magnification (E, the zoomed-in area indicated by the white-dashed box in D) revealed a cross-section of the IDB-CVF transition, where the gradual increase (1–5) in cell wall thickness is recorded in the table. Scale bars: 1 µm (D), and 500 nm (E). A comparable section of the microstructure shown in E is indicated in the model diagram (C). The dispersed phase droplet is labeled with the asterisk and the transition of IDB site to CVF center is indicated using white-dashed lines.

We believe the presence of CVF could be essential to explain 1) the size criteria of CP and 2) the role of high-intensity turbulence for TIEG formation determined from the experimental results. First, extreme turbulent conditions in HILF-US and HPH reduce the average size of the CP-stabilized droplets and inter-droplet voids, initiating the formation of CVF packing structures. Such fractal connections may not form due to limited droplet splitting capacity at a lower turbulent intensity (e.g. UT), which led to the formation of liquid emulsion with an excess of CPs unused in the aqueous phase (Figure S9). On the other hand, molecular stabilizers (e.g. WPI, SC, and SPI supernatant) would be too small for effective void filling, resulting in the formation of liquid emulsions under HILF-US emulsification (Fig. 2A–C). As IDB should be highly prevalent in these emulsions, the absence of a gel texture can be attributed to a lack of effective CVF due to the absence of CPs.

3.3.3. Effects of CP properties on CVF stabilization

We further highlight the close connection between CP properties and CVF stabilization using BMC and GO systems. In particular, the development of CVF appeared to be dependent on CP concentration and CP dimensional properties. Evidently, high BMC concentration contributed to the further droplet size reduction, creating more IDB and CVF sites, contributing to the higher viscoelastic properties of the TIEG (Figure S1 compared to Fig. 3H). Further, the excessive fraction of BMC in the continuous phase, after the consumption for interfacial adsorption, created extensive CVF sites throughout the microstructure. These CP-enriched tetrahedral/octahedral voids showed as the inter-connected vein-like networks at inner droplet interfaces (Fig. 6C). In comparison, early depletion of BMC during droplet breakup at low concentration resulted in the lack of visible CVF (Fig. 6A). Therefore, the development of CVF could require not only size matching (Fig. 5) but also a sufficient CP concentration level.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CP concentration and dimensional alteration on IDB-CVF stabilization in BMC (A and C, 10 and 100 mg mL−1, BMC-cyclohexane, OF = 0.5 v/v) and GO (B, GO-dodecane, 15 mg mL−1, and D, GO/rGO-cyclohexane, 10 mg mL−1, partially reduced by ascorbic acid, OF = 0.5 v/v) TIEGs. The presence of CVF effect can be observed from the inner droplet curvature at high BMC concentration (C, indicated by arrows), which is absent in the low concentration counterpart (A). 2D single-layer GO sheets (B, 15 mg mL−1) were not capable of providing effective CVF. (D) Similar vein-like morphology is visible (indicated by arrows) potentially due to the 3D profile of reduced GO self-assemblies (10 mg mL−1) (I). Scale bars: 10 µm.

The dimensional requirement of CVF stabilization can be found in the GO system. For example, GO aerogel (Fig. 6B) showed a highly polygonal deformed microstructure dominated by nanoscale IDB (Fig. 4H) with no sign of CVF despite a high concentration (15 mg mL−1). While IDB can be purely based on the alignment of the 2D sheets, the lack of effective CVF could be the cause of polygonal droplet deformation upon relaxation. Although such deformation could further extend IDB, the resulting expulsion of continuous phase from the voids could lead to syneresis and microstructural instability. This is consistent with the fact that single/few-layer GO suspensions only yielded soft gels (Fig. 3I).

In comparison, partially reduced GO suspensions promoted stronger TIEG formation at a lower GO concentration (Figure S10). The microstructure of the corresponding aerogel (Fig. 6D) showed both robust IDB via thin GO/rGO sheets and evident CVF with vein-like networks visible from the inner droplet surface, resembling the aerogel microstructure based on 3-dimensional CPs (Fig. 6C). It is, therefore, speculated that the partial reduction of GO could lead to the development of 3-dimensional self-assemblies due to enhanced hydrophobic interactions to enable effective CVF while maintaining the flexibility and amphiphilicity necessary for interfacial adsorption and IDB. Overall, it is consistent with the role of CVF in enhancing structural integrity by converting vulnerable inter-droplet voids into anchor points from the continuous phase.

Together, the presence of CVF and IDB could enable the two groups of spheres to act synergistically to develop an integrated network, resulting in significantly reduced mobility of both liquid phases at the microscopic level. While IDB could be present in both crowded liquid emulsions and emulsion gels, we propose that effective CVF must be present in TIEGs but is lacking in the liquid emulsions. At this stage, we speculate that the short-range physical interactions like hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals, hydrophobic, or electrostatic interactions amongst CPs could be responsible for the adaptive IDB-CVF stabilization. Nevertheless, further detailed investigation based on experimental examination (e.g., zeta potential of colloidal particle suspensions and their corresponding TIEGs) and numerical modeling (i.e., total interaction potential based on DLVO theory) may have to be carried out to fully understand the role of short-range interactions on TIEG formation.

3.3.4. Mechanism of TIEG formation

Based on the extensive experimental evidence across a wide range of colloidal systems, we have proposed a mechanism for TIEG formation, as illustrated in Fig. 7. On the interface of an aqueous CP suspension and a WIL, droplet breakup events occur as a result of turbulent energy injection, from which polydisperse CP-stabilized droplets are developed. Within the OF window of 0.4 – 0.6, the dispersed droplets are in close proximity and can interact with each other as facilitated by high-intensity turbulence. The sufficient droplet size reduction along with the presence of CPs gives rise to two complementary stabilizing modes – IDB and CVF, corresponding to stabilization in domains of the dispersed phase and inter-droplet voids in the continuous phase. Specifically, the development of CVF requires size matching between the inter-droplet voids and CPs, which connects the role of intense turbulence (to produce small droplets) and CP criteria (large enough to be able to fill voids). The close packing pattern based on two groups of 3D subjects (i.e. CPs and CP-stabilized droplets), therefore, can be established across a length scale of 10-1 – 101 µm, which potentially extends short-range interactions amongst CPs. This universal packing pattern offers microstructural immobilization, which can account for the dramatic macroscopic liquid-gel transition.

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of TIEG formation mechanism. Emulsion formulation factors including oil fraction and type (e.g. alkanes and triglycerides) and physical properties of CP (e.g. particle size) were shown to be central to TIEG formation. High-intensity turbulent conditions are needed to physically trigger the TIEGs from emulsions with requisite compositions. The macroscopic liquid-gel transition can be related to universal droplet stabilization mechanisms: IDB and CVF provide stabilization at droplet–droplet interfaces and within inter-droplet aqueous voids, respectively. High-intensity micro-turbulence is required to create sufficiently fine droplets and aqueous void spaces able to directly accommodate the remaining CPs as the second group of 3D subjects, therefore, initiating CVF stabilization. Given the same emulsion formulation, low-intensity macro-turbulence poses limited droplet splitting capability, which leads to the absence of CVF and high droplet mobility within the continuous (aqueous) phase, hence macroscopic free-flowing liquids.

Additionally, the formation of TIEGs could be considered in light of a fractal sphere packing process, with the CPs involved in CVF serving as the base-level particle in the packing hierarchy. Following this thread, we further speculate that TIEG formation could connect droplet breakup kinetics in turbulent fields (droplet focused)[48] to the random Apollonian close packing model (generalized to all ‘spheres’)[59], [60].

3.4. Architectural derivations and potential applications based on TIEGs

Based on the mechanistic understandings of TIEG formation, we now demonstrate several potential applications of TIEGs and architectural derivations based on TIEGs, highlighting its platform-like capability. First, a wide selection of natural biopolymers can be utilized to produce food emulsion gels without requiring conventionally used e-numbered stabilizers, thickeners, or gelling agents. For example, a low-fat TIEG butter spread analog possessed superior heat stability when benchmarked against a commercial product (Figure S11). Furthermore, the formation of double emulsion gels (Figure S12), oleogels (Figure S12) and aerogels (Figures S13-S15) can be achieved based on the TIEG platform by manipulating liquid phases.

It is worth highlighting that many TIEGs are 3D-printable, which could help to generate potential 3D printing ink sources based on the selected CP. For instance, TIEGs based on graphene materials could be 3D printed, which are precursors of 3D architectures (Figure S13). The current TIEG criteria enable the facile formation of 3D printable self-standing GO/rGO ink sources, posing several advantages compared to other printing methods[5], [61], [62], [63], [64] – the formation of GO/rGO TIEG inks does not require complicated surface functionalization, external emulsifiers/thickeners/gelling agents, or room-temperature solidified dispersed phase to grant 3D printability, owning a competitively low solids concentration requirement, simple formulation and wide selection of WILs (Table S4).

Apart from single-component aerogel formation, the introduction of guest components can be achieved in many ways. P25-GO aerogel was prepared by applying P25 and GO mixture as the CP suspension, resulting in highly wrinkled morphology due to the nanoscale wrapping/folding of TiO2 particles (Figure S14). In another approach, Au(III) was introduced during chitosan colloidal suspension preparation, where in-situ nucleation and growth of gold nanoparticles can be achieved on-demand after forming a chitosan-Au(III) aerogel (Figure S15). Indeed, these systems need dedicated tailoring to evaluate performance in specific applications. The key takeaway message here, instead, is the great potential of exploiting the proposed TIEG formation mechanism in various applied fields such as food, cosmetics, pharmaceutics, environmental, energy and material science.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we reported findings on a universal type of emulsion textural transition from free-flowing liquids to semi-solid gels amongst a wide range of emulsion systems. Interestingly, the emulsion gel formation across all examined systems reported in this work was found to be physically triggered by the intense turbulence during the emulsification process, distinctively different from known emulsion gel conferring manifestations [23], [24], [50], [51], [52], [53], which led to investigations into the formation criteria of TIEGs. First, a strong dependence of stabilizer size was found, where colloidal particle stabilizers with an average size>0.1 µm were required for TIEG formation, despite their diverse chemical constitution. In addition, TIEG formation occurred within a universal oil fraction window between 0.4 and 0.6 (v/v), beyond which unstable W/O emulsions were observed. This criterion differentiated TIEG formation with gel-like HIPEs, typically reported at high OF levels above 0.6 v/v [10], [12], [13], [14], [15], [38]. Apart from the wide selection of aqueous CPs, TIEG formation was examined with a selection of WILs, including alkanes and triglycerides, from which the density and viscosity increase of WILs could improve the viscoelastic properties of TIEGs. TIEG formation can be physically triggered withlow total energy input (40 – 80 J mL−1) via HILF-US and HPH, but not by UT with extensive mixing (600 J mL−1). It was found that HILF-US and HPH offer greater turbulent intensity, estimated as the markedly higher energy dissipation rate (108-109 W kg−1) and smaller turbulent eddy size (∼0.2 µm) compared with UT mixing, highlighting the critical role of turbulent intensity on TIEG formation rather than total energy input. Such perspective was emphasized for the first time on a universal emulsion textural transition phenomenon, which lacks explanation in many relatable studies [17], [20], [21], [22], [26], [27], [29], [36], [44], [45]. Two stabilization modes, IDB and CVF, were observed at the microscopic level. The observation showed highly adaptive IDB based on CP properties, whereas the presence of CVF successfully explained the strong dependence of CP size and turbulent intensity from the experimental results. The two interconnected stabilizations from dispersed (IDB) and continuous phase (CVF) domain within a length scale 10-1-101 µm were unified under a dual-component (CP and droplets) 3D close packing model. This mechanism may also be useful to understand other emulsion systems that form TIEG [17], [21], [22], [26], [27], [29]. Finally, a selection of practical implementations based on TIEGs was demonstrated, showing its platform-like function and potential multi-field applications. We highlighted its capacity of generating a new type of ink materials for 3D printing graphene materials, which poses potential advantages compared to the reported routes [5], [61], [62], [63], [64]. The methodological and mechanistic insights of TIEGs in this work could serve as a foundation for further exploration of individual emulsion systems and their applications in a wide range. Nevertheless, further rigorous investigations on additional TIEG formation criteria (e.g. effects of aqueous environments and CP categorization) and numerical modeling and prediction of TIEG formation (e.g. droplet breakup criteria under turbulent flow and random close packing theories) are of great importance to exploit the full potential of the platform.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wu Li: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Gregory J.O. Martin: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Muthupandian Ashokkumar: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the support of Melbourne Research Scholarship and Albert Shimmins Research Continuity Funding. The research was supported under Australian Research Council's Industrial Transformation Research Program (ITRP) funding scheme (IH120100005). The ARC Dairy Innovation Hub is a collaboration between The University of Melbourne, The University of Queensland and Dairy Innovation Australia Ltd.. We acknowledge the two imaging platforms, namely Bio21 Ian Holmes Imaging Centre (IHIC) and Biological Optical Microscopy Platform (BOMP) for the imaging facilities. We thank BY. Zhang for the drawings of mechanistic illustration.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105847.

Contributor Information

Wu Li, Email: wu.li@unimelb.edu.au.

Muthupandian Ashokkumar, Email: masho@unimelb.edu.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dickinson E. Emulsion gels: the structuring of soft solids with protein-stabilized oil droplets. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;28(1):224–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupi F.R., Gabriele D., Seta L., Baldino N., de Cindio B., Marino R. Rheological investigation of pectin-based emulsion gels for pharmaceutical and cosmetic uses. Rheol. Acta. 2015;54(1):41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu Z., Patten T., Pelton R., Cranston E.D. Synergistic stabilization of emulsions and emulsion gels with water-soluble polymers and cellulose nanocrystals. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2015;3(5):1023–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallegos C., Franco J.M. Rheology of food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999;4(4):288–293. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barg S., Perez F.M., Ni N., do Vale Pereira P., Maher R.C., Garcia-Tuñon E., Eslava S., Agnoli S., Mattevi C., Saiz E. Mesoscale assembly of chemically modified graphene into complex cellular networks. Nat. Commun. 2014;5(1) doi: 10.1038/ncomms5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farjami T., Madadlou A. An overview on preparation of emulsion-filled gels and emulsion particulate gels. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;86:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quemada D., Berli C. Energy of interaction in colloids and its implications in rheological modeling. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002;98(1):51–85. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(01)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everett D. Manual of symbols and terminology for physicochemical quantities and units. Pure Appl. Chem. 1972;31:579–638. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Aken G.A., Blijdenstein T.B.J., Hotrum N.E. Colloidal destabilisation mechanisms in protein-stabilised emulsions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;8(4-5):371–379. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan H., Sun G., Lin W., Mu C., Ngai T. Gelatin particle-stabilized high internal phase emulsions as nutraceutical containers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(16):13977–13984. doi: 10.1021/am503341j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaganyuk M., Mohraz A. Role of particles in the rheology of solid-stabilized high internal phase emulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;540:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron N.R. High internal phase emulsion templating as a route to well-defined porous polymers. Polymer. 2005;46:1439–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X.-N., Zhou F.-Z., Yang T., Yin S.-W., Tang C.-H., Yang X.-Q. Fabrication and characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (HIPEs) stabilized by chitosan-caseinophosphopeptides nanocomplexes as oral delivery vehicles. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;93:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y.-T., Liu T.-X., Tang C.-H. Novel pickering high internal phase emulsion gels stabilized solely by soy β-conglycinin. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;88:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y.-T., Tang C.-H., Binks B.P. High internal phase emulsions stabilized solely by a globular protein glycated to form soft particles. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;98 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar A., Dickinson E. Sustainable food-grade Pickering emulsions stabilized by plant-based particles. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;49:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M.N., Chan H.K., Mohraz A. Characteristics of Pickering emulsion gels formed by droplet bridging. Langmuir. 2012;28:3085–3091. doi: 10.1021/la203384f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horozov T.S., Binks B.P. Particle-stabilized emulsions: a bilayer or a bridging monolayer? Angew. Chem. 2006;118(5):787–790. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X., Chen X.-W., Guo J., Yin S.-W., Yang X.-Q. Wheat gluten based percolating emulsion gels as simple strategy for structuring liquid oil. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;61:747–755. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Y.Q., Chen X., McClements D.J., Zou L., Liu W. Pickering-stabilized emulsion gels fabricated from wheat protein nanoparticles: Effect of pH, NaCl and oil content. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2018;39:826–835. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang C.-H., Liu F. Cold, gel-like soy protein emulsions by microfluidization: emulsion characteristics, rheological and microstructural properties, and gelling mechanism. Food Hydrocolloids. 2013;30:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu F., Tang C.-H. Cold, gel-like whey protein emulsions by microfluidisation emulsification: Rheological properties and microstructures. Food Chem. 2011;127:1641–1647. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y., Liu L., Wang B., Yang X., Chen Z., Zhong Y., Zhang L., Mao Z., Xu H., Sui X. Polysaccharide-based edible emulsion gel stabilized by regenerated cellulose. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;91:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X.-Y., Wang J., Rousseau D., Tang C.-H. Chitosan-stabilized emulsion gels via pH-induced droplet flocculation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;105 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaganyuk M., Mohraz A. Impact of particle size on droplet coalescence in solid-stabilized high internal phase emulsions. Langmuir. 2019;35:12807–12816. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang N., Zhang L., Sun D. Influence of emulsification process on the properties of Pickering emulsions stabilized by layered double hydroxide particles. Langmuir. 2015;31:4619–4626. doi: 10.1021/la505003w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaganyuk M., Mohraz A. Non-monotonic dependence of Pickering emulsion gel rheology on particle volume fraction. Soft Matter. 2017;13:2513–2522. doi: 10.1039/c6sm02858f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee M.N., Chan H.K., Mohraz A. Characteristics of pickering emulsion gels formed by droplet bridging. Langmuir. 2011;28:3085–3091. doi: 10.1021/la203384f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manoi K., Rizvi S.S.H. Emulsification mechanisms and characterizations of cold, gel-like emulsions produced from texturized whey protein concentrate. Food Hydrocolloids. 2009;23:1837–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gamlath C.J., Leong T.S.H., Ashokkumar M., Martin G.J.O. The inhibitory roles of native whey protein on the rennet gelation of bovine milk. Food Chem. 2018;244:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semo E., Kesselman E., Danino D., Livney Y.D. Casein micelle as a natural nano-capsular vehicle for nutraceuticals. Food Hydrocolloids. 2007;21:936–942. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J., Yao B., Li C., Shi G. An improved Hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon. 2013;64:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang J.H., Kim T., Choi J., Park J., Kim Y.S., Chang M.S., Jung H., Park K.T., Yang S.J., Park C.R. Hidden second oxidation step of Hummers method. Chem. Mater. 2016;28:756–764. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J., Yang H., Shen G., Cheng P., Zhang J., Guo S. Reduction of graphene oxide via L-ascorbic acid. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:1112–1114. doi: 10.1039/b917705a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z.-L., Xu D., Huang Y., Wu Z., Wang L.-M., Zhang X.-B. Facile, mild and fast thermal-decomposition reduction of graphene oxide in air and its application in high-performance lithium batteries. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:976–978. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16239c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F., Tang C.-H. Soy protein nanoparticle aggregates as Pickering stabilizers for oil-in-water emulsions. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2013;61:8888–8898. doi: 10.1021/jf401859y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beverung C., Radke C.J., Blanch H.W. Protein adsorption at the oil/water interface: characterization of adsorption kinetics by dynamic interfacial tension measurements. Biophys. Chem. 1999;81:59–80. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(99)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiao B., Shi A., Wang Q., Binks B.P. High-internal-phase pickering emulsions stabilized solely by peanut-protein-isolate microgel particles with multiple potential applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:9274–9278. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta A., Eral H.B., Hatton T.A., Doyle P.S. Controlling and predicting droplet size of nanoemulsions: scaling relations with experimental validation. Soft Matter. 2016;12:1452–1458. doi: 10.1039/c5sm02051d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boxall J.A., Koh C.A., Sloan E.D., Sum A.K., Wu D.T. Droplet size scaling of water-in-oil emulsions under turbulent flow. Langmuir. 2012;28(1):104–110. doi: 10.1021/la202293t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stang M., Schuchmann H., Schubert H. Emulsification in high-pressure homogenizers. Eng. Life Sci. 2001;1:151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moholkar V.S., Pandit A.B. Bubble behavior in hydrodynamic cavitation: effect of turbulence. AIChE J. 1997;43(6):1641–1648. [Google Scholar]

- 43.P.S. Kumar, A. Pandit, Modeling hydrodynamic cavitation, Chemical engineering & technology: industrial chemistry‐plant equipment‐process engineering‐biotechnology, 22 (1999) 1017-1027.

- 44.French D.J., Taylor P., Fowler J., Clegg P.S. Making and breaking bridges in a Pickering emulsion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;441:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Floury J., Desrumaux A., Legrand J. Effect of ultra-high-pressure homogenization on structure and on rheological properties of soy protein-stabilized emulsions. J. Food Sci. 2006;67:3388–3395. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies J. A physical interpretation of drop sizes in homogenizers and agitated tanks, including the dispersion of viscous oils. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1987;42:1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vankova N., Tcholakova S., Denkov N.D., Ivanov I.B., Vulchev V.D., Danner T. Emulsification in turbulent flow: 1. Mean and maximum drop diameters in inertial and viscous regimes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007;312:363–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skartlien R., Sollum E., Schumann H. Droplet size distributions in turbulent emulsions: Breakup criteria and surfactant effects from direct numerical simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139 doi: 10.1063/1.4827025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W., Leong T.S., Ashokkumar M., Martin G.J. A study of the effectiveness and energy efficiency of ultrasonic emulsification. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:86–96. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07133g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimitrova T.D., Leal-Calderon F. Rheological properties of highly concentrated protein-stabilized emulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;108:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bai H., Li C., Wang X., Shi G. A pH-sensitive graphene oxide composite hydrogel. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:2376–2378. doi: 10.1039/c000051e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang X., Ma C., Yan X., Zeng H., McClements D.J., Liu X., Liu F. Structure, rheology and functionality of whey protein emulsion gels: effects of double cross-linking with transglutaminase and calcium ions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;102 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Luo K., Liu S., Zeng M., Adhikari B., He Z., Chen J. Textural and rheological properties of soy protein isolate tofu-type emulsion gels: influence of soybean variety and coagulant type. Food Biophys. 2018;13:324–332. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohraz A. Interfacial routes to colloidal gelation. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;25:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richtering W. Responsive emulsions stabilized by stimuli-sensitive microgels: emulsions with special non-pickering properties. Langmuir. 2012;28:17218–17229. doi: 10.1021/la302331s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plamper F.A., Richtering W. Functional microgels and microgel systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:131–140. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geisel K., Isa L., Richtering W. Unraveling the 3D localization and deformation of responsive microgels at oil/water interfaces: a step forward in understanding soft emulsion stabilizers. Langmuir. 2012;28:15770–15776. doi: 10.1021/la302974j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Destribats M., Lapeyre V., Wolfs M., Sellier E., Leal-Calderon F., Ravaine V., Schmitt V. Soft microgels as Pickering emulsion stabilisers: role of particle deformability. Soft Matter. 2011;7(17):7689. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05240c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farr R.S., Groot R.D. Close packing density of polydisperse hard spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131 doi: 10.1063/1.3276799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Desmond K.W., Weeks E.R. Influence of particle size distribution on random close packing of spheres. Phys. Rev. E. 2014;90(2) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.90.022204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.García-Tuñon E., Barg S., Franco J., Bell R., Eslava S., D'Elia E., Maher R.C., Guitian F., Saiz E. Printing in three dimensions with graphene. Adv. Mater. 2015;27(10):1688–1693. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu C., Han T.-Y.-J., Duoss E.B., Golobic A.M., Kuntz J.D., Spadaccini C.M., Worsley M.A. Highly compressible 3D periodic graphene aerogel microlattices. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin Y., Liu F., Casano G., Bhavsar R., Kinloch I.A., Derby B. Pristine graphene aerogels by room-temperature freeze gelation. Adv. Mater. 2016;28(36):7993–8000. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fu K., Wang Y., Yan C., Yao Y., Chen Y., Dai J., Lacey S., Wang Y., Wan J., Li T., Wang Z., Xu Y., Hu L. Graphene oxide-based electrode inks for 3D-printed lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2016;28(13):2587–2594. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.