Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the joint (combined) association of excess adiposity and genetic predisposition with the risk of incident female gout, and compare to their male counterparts; and determine the proportion attributable to body mass index (BMI) only, genetic risk score (GRS) only, and to their interaction.

Methods

We prospectively investigated potential gene-BMI interactions in 18,244 women from the Nurses’ Health Study [NHS] and compared to 10,888 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). Genetic risk score (GRS) for hyperuricemia was derived from 114 common urate-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Results

Multivariable relative risk (RR) for female gout was 1.49 (95% CI: 1.42 to 1.56) per 5 kg/m2 increment of BMI and 1.43 (1.35 to 1.52) per standard deviation increment in the GRS. For their joint association of BMI and GRS, RR was 2.18 (2.03 to 2.36), more than the sum of each individual factor, indicating significant interaction on an additive scale (p for interaction <0.001). The attributable proportions of joint effect for female gout were 42% (37% to 46%) to adiposity, 37% (32% to 42%) to genetic predisposition, and 22% (16% to 28%) to their interaction. Additive interaction among men was smaller although still significant (p interaction 0.002, p for heterogeneity 0.04 between women and men), and attributable proportion of joint effect was 14% (6% to 22%).

Conclusions

While excess adiposity and genetic predisposition both are strongly associated with a higher risk of gout, the excess risk of both combined was higher than the sum of each, particularly among women.

Keywords: Gout, epidemiology, crystal arthropathies

INTRODUCTION

Gout, the most common inflammatory arthritis, leads to excruciatingly painful flares and joint damage, and an excess burden of cardiometabolic-renal comorbidities.1 Indeed, the global burden of gout and comorbidity has increased in recent decades,2 3 disproportionately so among women.2 Yet, traditionally considered a disease of men, data on female-specific gout are scarce, despite purported differences from males in risk factors4-7 and clinical spectrums.8 For example, obesity, the strongest modifiable risk factor for gout,2 3 9-15 is more strongly associated with female gout than male gout in cross-sectional analyses,4 6 7 as are the obesity-driven comorbidities such as myocardial infarction, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.1 4 5 Obesity and associated insulin resistance lead to hyperuricemia and gout primarily by decreasing renal excretion of urate;16-21 the causality is supported by recent Mendelian randomisation studies.22-27

Furthermore, genetics substantially contribute to overall gout risk (serum urate heritability estimates range from 25% to 60%), with differential sex-specific effects from the prominent genes.28-31 For example, of the two top genes, compared to male gout, the SLC2A9 effect is stronger for female gout, whereas the ABCG2 effect is weaker.28 30 As such, the impact of excess adiposity on the risk of incident gout may vary according to one’s genetic predisposition, particularly for female gout where obesity appears to play a larger role.4 6 7 Correspondingly, excess adiposity may serve to exacerbate an individual’s genetic susceptibility to gout. However, no relevant prospective data for the risk of incident female gout are available.

Our objective was to prospectively investigate the potential impact of adiposity on the risk of incident female gout, according to genetic predisposition, in a large prospective cohort of women (Nurses’ Health Study [NHS] cohort) and to replicate in a separate prospective cohort of younger women (NHS II). We also compared these results to men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). We addressed etiological inferences as well as greater public health implications, using additive interactions,32-38 and determined the proportion of excess risk attributable to BMI alone, to genetic predisposition alone, and to their interaction.35-38

METHODS

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is a prospective cohort study of 121,700 US female registered nurses who were 30 to 55 years of age upon enrollment in 1976,39 whilst the NHS II is a prospective cohort study of 116,430 US female registered nurses who were 25 to 42 years of age upon enrollment in 1989. The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) is a prospective cohort of 51,529 US male health professionals who were 40 to 75 years of age upon enrollment in 1986.40 In all studies, participants were mailed validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQ)41-45 every four years (starting from baseline for the HPFS and from the 1984 and 1991 follow-up questionnaires for the NHS and NHS II, respectively) and biennial questionnaires that asked about new medical diagnoses, medication use, and lifestyle factors. Completion of the self-administered questionnaire was considered to imply informed consent. The current analysis, approved by the Massachusetts General Brigham Institutional Review Board, includes data from 26,490 women (N=18,244 from the NHS; N=8,246 from the NHS II) and 10,899 men of European ancestry who did not report a history of gout at baseline, and for whom genotype data based on GWAS were available.46 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Assessment of adiposity, covariates, and incident gout

Adiposity was determined by body mass index (BMI), weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). For each cohort, information on weight and height was obtained on the baseline questionnaire, and weight was updated every two years. In validation studies, self-reported weight in the HPFS and NHS I was highly correlated with values obtained by technicians during home visits (r = 0.97 for both).47 Covariates of interest, which have also been validated and used extensively in these cohorts, included age, history of hypertension,9 systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diuretic use,9 and among women, menopausal status and the use of hormone replacement therapy;48 these were ascertained from the biennial questionnaires. Alcohol consumption,49 total energy intake, and consumption of meat, seafood, and dairy foods40 were ascertained from the FFQ.41-45 Incident gout was based on these nurses and health professionals’ report of new-onset, physician-diagnosed gout on the biennial health questionnaires.50 The present analysis uses data from questionnaires completed during the years 1984 to 2018 for the NHS, 1991 to 2017 for NHS II, and 1986 to 2018 for the HPFS.

Genetic risk score and key individual genes

We constructed a genetic risk score (GRS) from 114 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) derived from European-ancestry meta-analysis of serum urate among 288,649 individuals.29 GRS was computed as a weighted sum of risk alleles from the 114 SNPs, followed by standardization to mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Specifically, each SNP was weighted by its relative effect size for serum urate.29 Higher scores indicate a greater genetic predisposition for hyperuricemia and gout. We also assessed the individual SNPs mapped to the two most prominent serum urate genes driving gout risk, SLC2A9 and ABCG2, both of which have exhibited sex-specific effects.29 30

Statistical analysis

We assessed the individual and joint (combined) associations between BMI, GRS, and the risk of incident gout, using Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for previously identified risk factors for gout in a time-updated manner,9 40 51-53 separately for each cohort: NHS (discovery), NHS II (replication), and HPFS (male comparators). Participants contributed person-time from the return of the first questionnaire (NHS, 1984; NHS II, 1991; HPFS, 1986) until gout diagnosis, death, loss to follow-up, or end of the follow-up period (30 June 2018 for the NHS and HPFS and 30 June 2017 for NHS II), whichever came first.

To assess etiological as well as greater public health implications, 32-34 we investigated the additive interaction35-38 between continuous measures of adiposity and genetic predisposition on incident gout risk, considering BMI in 5 kg/m2 increments and GRS in one standard deviation (SD) increments. The relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI)35-38 54 55 was assessed as an index of additive interaction;34 56 95% confidence intervals were computed using the delta method described by Hosmer and Lemeshow.57 Briefly, on the relative risk (RR) scale, we divided the relative risk from both exposures (RR11-1) into the excess relative risk from BMI alone (RR01-1), GRS alone (RR10-1), and their additive interaction (RERI): RR11-1=(RR01-1) + (RR10-1 )+ RERI. We used Cochrane’s Q statistic and the I2 statistic to examine heterogeneity in the associations for women and men. We subsequently calculated the proportion of the joint effect (the attributable proportion) due to BMI alone (RR01-1)/(RR11-1); GRS alone (RR10-1)/(RR11-1); and due to their additive interaction, RERI/(RR11-1), as done previously.35-38 This represents the proportion of the excess incident gout cases (over-and-above the background risk) attributable either to elevated BMI alone, elevated genetic risk alone, or the combination. We also evaluated for multiplicative interactions using the Wald test of a cross-product term of BMI and GRS.58 We conducted the same analyses for the individual SNPs. Our secondary analyses assessed the exposures categorically, using obesity (BMI ≥ vs < 30) or overweight (BMI ≥ vs < 25) cut-offs for adiposity and GRS above vs below the mean for genetic predisposition, and their joint effects.

Finally, to assess the contribution of overweight/obesity towards gout risk at the population level according to genetic predisposition, we calculated the population attributable risk (PAR).59 This is an estimate of the percentage of incident gout cases in each cohort that would theoretically not have occurred if all individuals had been in the lowest-risk category (e.g., BMI< 25 kg/m2) within each GRS stratum, assuming a causal relation between BMI and incident gout. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4. All p-values are two-sided.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or other members of the public were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design and implementation of the study. The results of the research conducted in the three cohorts are regularly reported to study participants.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

We included 18,244 women from the NHS (mean age 47.1 years) in our primary (discovery) analysis and 8,246 women from the NHS II (mean age 37.4) in our replication analysis, along with 10,888 men from the HPFS in our comparison analysis (mean age 54.3 years at baseline). Total follow-up time among all participants exceeded 1,090,858 person-years. At baseline, the distribution of clinical gout risk factors was similar among those with GRS below and above the mean, in all three cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Gout Risk Factors in Each Cohort, by Genetic Predisposition

| Characteristics | 114 SNP Genetic Risk Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Below Mean | Above Mean | |

| Nurses Health Study, 1984: n=18,244 (women, discovery cohort) | ||

| No. (%) | 9162 (50.2) | 9082 (49.8) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 47.1 (6.9) | 47.0 (6.9) |

| Hypertension, % | 15 | 17 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 24.5 (4.5) | 24.5 (4.4) |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week, mean (SD) | 14.6 (20.8) | 14.0 (19.3) |

| Alcohol, g/d, mean (SD) | 6.5 (10.2) | 6.6 (10.5) |

| Sugar sweetened soft drink intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Meat intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) |

| Seafood intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) |

| Low-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) |

| High-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) |

| Diuretic use, % | 9.6 | 10.2 |

| Nurses Health Study II, 1991: n=8,246 (women, replication cohort) | ||

| No. (%) | 4056 (49.2) | 4190 (50.8) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37.5 (4.4) | 37.3 (4.4) |

| Hypertension, % | 3.21 | 3.61 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 24.3 (4.9) | 24.5 (5.1) |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week, mean (SD) | 19.9 (24.9) | 20.7 (28.3) |

| Alcohol, g/d, mean (SD) | 3.2 (5.9) | 3.2 (6.1) |

| Sugar sweetened soft drink intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.42 (0.8) | 0.44 (0.8) |

| Meat intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.92 (0.6) |

| Seafood intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.51 (0.5) |

| Low-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.09 (1.1) |

| High-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.85 (0.9) | 0.85 (0.9) |

| Diuretic use, % | 2.6 | 2.7 |

| Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, 1986: n=10,888 (men, comparison cohort) | ||

| No. (%) | 5463 (50.2) | 5425 (49.8) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 54.3 (8.6) | 54.2 (8.7) |

| Hypertension, % | 21 | 21 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 25.6 (3.2) | 25.6 (3.1) |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week, mean (SD) | 20.2 (23.5) | 19.9 (23.7) |

| Alcohol, g/d, mean (SD) | 12.1 (15.6) | 12.4 (16.3) |

| Sugar sweetened soft drink intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) |

| Meat intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| Seafood intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) |

| Low-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| High-fat dairy foods intake, servings/d, mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.3) |

| Diuretic use, % | 10.0 | 10.1 |

Values are age-adjusted (except for age). BMI=body mass index; SD=standard deviation; SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism

Risk of incident female gout according to BMI and genetic risk score

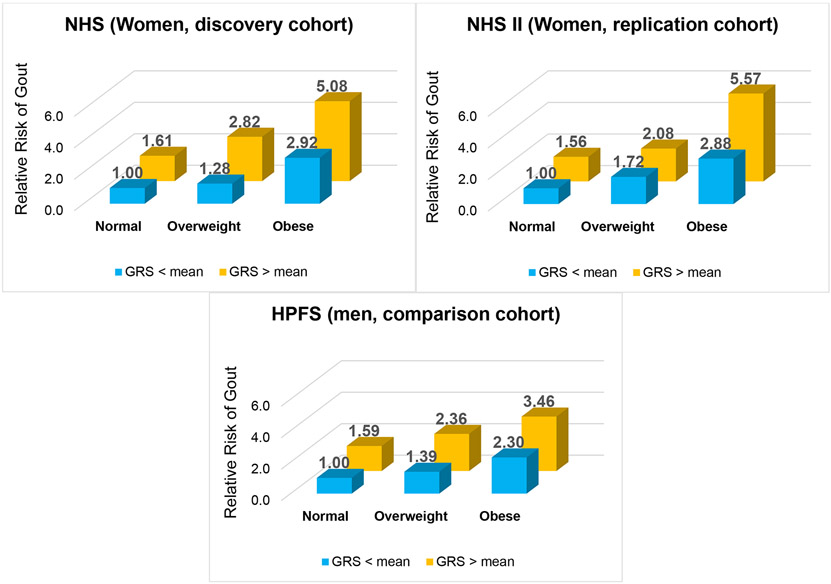

There were 1360 cases of incident female gout in the NHS cohort (discovery analysis) and 188 cases in the NHS II (replication analysis). The frequency of obesity at the time of gout diagnosis in these two female cohorts was 41% and 57%, respectively. Individually, higher levels of adiposity and higher GRS were positively and significantly associated with the risk of incident gout in multivariable analysis (p for trend < 0.01 in each cohort) (Tables 2, S1 and S2). For example, the RR for NHS women in the highest BMI category (versus the lowest) was 4.86 (95% CI: 3.96 to 5.95), whilst the RR for women in the highest GRS quintile (versus the lowest) was 2.89 (2.40 to 3.47) (Table 2). These trends persisted upon collapsing into three categories of BMI (corresponding to normal weight, overweight, and obesity) and dichotomous GRS (above and below the mean) (Table S3). Moreover, joint effects analysis revealed that obese women with a higher genetic predisposition had a five-times higher risk of incident gout (RR 5.08 [4.15 to 6.22]) than women in the lowest-risk category (e.g., normal weight and GRS below the mean), while that in men tended to be smaller (RR 3.46 [2.83 to 4.24] (Figure 1).

Table 2:

Relative Risk (RR) of Incident Gout According to Body Mass Index and According to Genetic Risk Score, Nurses Health Study (women, discovery cohort)

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <23 | 23-24.9 | 25-29.9 | 30-34.9 | ≥35 | Per Unit Increasea |

P for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N cases | 201 | 172 | 433 | 316 | 238 | - | - |

| Person-years | 189,242 | 116,119 | 192,533 | 76,228 | 35,075 | - | - |

| Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | 1.06 | 1.48 | 2.25 | 4.15 | 6.79 | - | - |

| Age-Adjusted RR (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.41 (1.15 to 1.72) | 2.09 (1.77 to 2.47) | 3.97 (3.31 to 4.74) | 7.00 (5.78 to 8.48) | 1.63 (1.57 to 1.70) | <0.01 |

| MV RR* (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.32 (1.07 to 1.62) | 1.78 (1.50 to 2.11) | 2.95 (2.45 to 3.56) | 4.66 (3.80 to 5.72) | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.54) | <0.01 |

| MV RR + GRS** (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.33 (1.08 to 1.62) | 1.80 (1.51 to 2.13) | 2.98 (2.48 to 3.60) | 4.86 (3.96 to 5.95) | 1.49 (1.43 to 1.56) | <0.01 |

| Genetic risk score | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Per Unit Increaseb |

P for trend |

| N cases | 153 | 206 | 263 | 310 | 428 | - | - |

| Person-years | 121,847 | 121,819 | 121,887 | 121,867 | 121,777 | - | - |

| Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | 1.26 | 1.69 | 2.16 | 2.54 | 3.51 | - | - |

| Age-Adjusted RR (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.36 (1.10 to 1.68) | 1.73 (1.42 to 2.11) | 2.06 (1.70 to 2.50) | 2.82 (2.35 to 3.40) | 1.45 (1.37 to 1.53) | <0.01 |

| MV RR* (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.73) | 1.71 (1.40 to 2.08) | 2.08 (1.71 to 2.52) | 2.78 (2.31 to 3.35) | 1.43 (1.36 to 1.51) | <0.01 |

| MV RR + BMI*** (95% CI) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.45 (1.17 to 1.78) | 1.72 (1.41 to 2.10) | 2.14 (1.76 to 2.60) | 2.89 (2.40 to 3.47) | 1.45 (1.38 to 1.53) | <0.01 |

per 5 kg/m2 increase

per standard deviation increase

Multivariable (MV) relative risk adjusted for age, total energy intake, consumption of meat, seafood, and dairy foods, history of hypertension, diuretic use, menopausal status, and use of oral contraceptive or postmenopausal hormone therapy.

1. Joint Association of Body Mass Index (BMI) and Genetic Predisposition on the Risk of Incident Gout.

GRS=genetic risk score; HPFS=Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; NHS=Nurses Health Study; NHS II=Nurses Health Study II. Normal weight = BMI <25 kg/m2; Overweight = 30<BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2; Obese = BMI ≥30 kg/m2

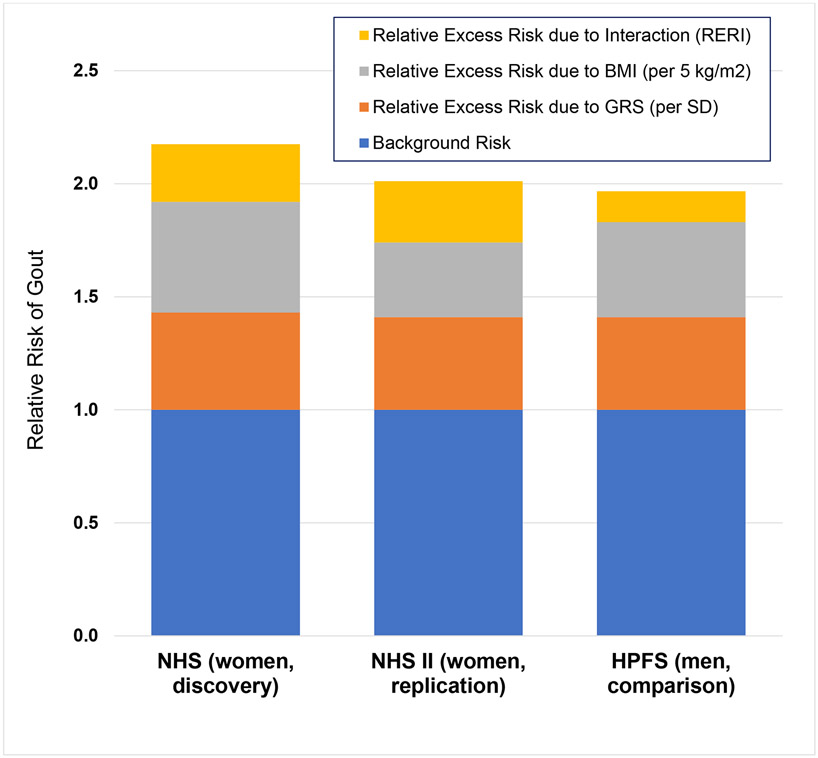

When examining the joint effects of continuous BMI and GRS on female gout risk, there was a significant additive interaction between these exposures among our discovery cohort (relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI)=0.25 [95% CI: 0.12 to 0.33], p < 0.001) (Table 3). Specifically, the RRs for incident gout in the NHS were 1.49 (1.42 to 1.56) per unit (5 kg/m2) increase of BMI (adjusting for GRS), 1.43 (1.35 to 1.52) per SD increase of GRS (adjusting for BMI), and 2.18 (2.03 to 2.36) for their joint effect (Table 3 and Figure 2). Put another way, if there was no evidence of additive interaction (e.g., RERI=0), the expected RR for the joint effect would be 1.92 (e.g., 1.43 + 1.49 – 1). The attributable proportions of the joint effect were 42% for BMI alone, 37% for GRS alone, and 22% for their interaction (Figure 2). At the same time there was no evidence of an interaction on the multiplicative scale (p ≥ 0.15). These findings were replicated among younger women in the NHS II (p for interaction < 0.001), where the attributable proportion due to interaction was 27% (16% to 38%) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Attributing Effects to Additive Interaction between Body Mass Index and Genetic Risk Score on Risk of Incident Gout

| NHS (Women, discovery; N=1,360 cases) |

NHS II (Women, replication; N=188 cases) |

HPFS (Men, comparison; N=1,703 cases) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects, relative risk (95% CI) | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2* | 1.49 (1.42 to 1.56) | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.48) | 1.42 (1.35 to 1.51) |

| Genetic risk score** | 1.43 (1.35 to 1.52) | 1.41 (1.19 to 1.68) | 1.41 (1.34 to 1.48) |

| Joint effect | 2.18 (2.03 to 2.36) | 2.01 (1.69 to 2.39) | 1.97 (1.83 to 2.12) |

| Relative excess risk (95% CI) due to interaction | |||

| Relative excess risk due to interaction | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| (RERI)*** | (0.12 to 0.33) | (0.14 to 0.40) | (0.05 to 0.22) |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Attributable proportion, % (95% CI) | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2* | 41.5 (37.3 to 45.8) | 32.8 (22.4 to 43.1) | 43.8 (37.8 to 49.8) |

| Genetic risk score** | 36.8 (31.5 to 42.1) | 40.4 (27.1 to 53.7) | 42.1 (36.2 to 47.9) |

| Additive interaction | 21.7 (16.2 to 27.7) | 26.8 (15.9 to 37.7) | 14.1 (6.1 to 22.2) |

Multivariable relative risk adjusted for age, total energy intake, consumption of meat, seafood, and dairy foods, history of hypertension, diuretic use, menopausal status (women only), and use of oral contraceptive or postmenopausal hormone therapy (women only).

per 5 kg/m2 increase

per standard deviation increase

RERI > 0 is consistent with the presence of additive interaction.

2. Joint Association of Body Mass Index (BMI) and Genetic Risk Score (GRS) on the Risk of Incident Gout.

HPFS=Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; NHS=Nurses Health Study; NHS II=Nurses Health Study II; SD=standard deviation. The area of each coloured bar represents the proportion of the excess risk of incident gout attributable to each individual exposure (BMI and GRS) and to their joint effects.

When examining these exposures categorically, there were additive interactions between obesity status and genetic risk among women. Obese women with a higher genetic predisposition had a 4.5-times higher risk of incident female gout (RR 4.49 [3.81 to 5.29]) than non-obese women with lower genetic predisposition (e.g., BMI < 30 kg/m2 and GRS below the mean) (Table S4). The attributable proportion due to this interaction was 29%, whilst that for women in the NHS II was 53% (Table S4).

Comparison with incident gout among males

There were 1703 cases of incident gout in the HPFS (male comparison cohort) during the 32 years; obesity was much less frequent among incident male gout (21% were obese at the time of diagnosis) than incident female gout (41% and 57% were obese, respectively, in the NHS and NHS II). The relative excess risk due to interaction among males was 0.14 (0.05 to 0.22), significantly lower than that among females (p for heterogeneity between the male and pooled female cohorts = 0.04) though still indicative of an additive BMI-GRS interaction (p=0.002) (Table 3). Findings were consistent when assessing these exposures categorically (Table S4 and S5); the relative excess risk due to interaction between obesity status and genetic predisposition among males tended to be lower than in females.

Interaction between BMI and key individual genes

Additive interactions were also observed between BMI and the individual SNPs mapped to the two most prominent serum urate genes, with relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) values of 0.21 (0.13 to 0.29) for SLC2A9 and 0.23 (0.08 to 0.38) for ABCG2 in the NHS (p for interaction <0.01). These findings were replicated within the NHS II (p for interaction <0.03). The additive interactions among men tended to be smaller, with RERI values of 0.14 (0.03 to 0.24) for SLC2A9 and 0.03 (−0.19 to 0.25) for ABCG2.

Population attributable risk of BMI according to genetic risk

Among women, the PAR of excess adiposity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) was 42.0% (36.8 to 46.6) and 33.2% (25.0 to 39.9) among those with GRS above and below the mean, respectively. Excess adiposity tended to account for smaller proportions of incident gout cases among men, with PARs of 27.4% (20.9 to 33.1) and 24.7% (15.9. to 32.1) among those with GRS above and below the mean, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In our large-scale prospective cohort analysis of US women with 114-SNP GRS and serial BMI measures, higher adiposity and higher genetic predisposition (whether inferred from a polygenic score or key individual loci) were independently and jointly associated with the risk of incident female gout, adjusting for other pertinent health and lifestyle risk factors. Among women, 42% of the joint effect was attributable to higher BMI alone, 37% to higher genetic risk alone, and 22% to an additive interaction between the two. These findings were replicated in a separate cohort of younger women among whom the attributable proportion due to interaction tended to be larger (27%), whereas that among men was only 14%. These findings underscore the importance of addressing excess adiposity for mitigating the risk of incident female gout and its cardiometabolic sequalae, especially for those with higher genetic predisposition, who are particularly prone to the deleterious effects of excess adiposity on gout.

Potential mechanisms

The mechanisms of this possible causal interaction,60 particularly among women, remain to be clarified. The sex differences in the independent and joint effects of BMI on gout risk are consistent with prior findings of higher prevalence of obesity (or mean level of BMI) in women with gout than in men, even after accounting for differences in age.4 7 Whether sex hormones or related factors contribute to the interaction between genetic predisposition and excess adiposity warrants further investigation. Moreover, a recent analysis of four US-based prospective cohorts found that the risk of incident gout was 42% higher among men even after accounting for differences in serum urate levels,61 suggesting the sex difference is explained by factors above and beyond hyperuricemia. To that end, obesity is associated with increased inflammatory biomarkers,62 adipokines, cytokines, and reduced levels of AMPK activity (as a master regulator of gouty inflammation),63-66 which may promote the development of gout by affecting an inflammatory response to deposited monosodium urate crystals.67 For example, leptin, an adipokine, was found to promote urate crystal induced inflammation in human and murine models;68 reduced AMPK activity in obesity could contribute to higher mononuclear phagocyte responses to urate crystals, including NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β and chemokine release.69 70

Public health implications

Our findings align with the recent Global Burden of Disease Study,2 3 which reported a disproportionate rise in gout burden among women over 1990-2017.2 Moreover, high BMI accounted for 31% of the burden of female gout globally in 2017, including 35% of the burden in Western Europe and 49% in high-income North America. From a public health standpoint, our findings reinforce adiposity as a major target for reducing the incidence and burden of female gout, with its higher frequencies of coronary heart disease,1 5 type 2 diabetes,1 4 5 and other cardiometabolic-renal comorbidities than male gout, particularly for women born with a greater genetic predisposition to developing this disease. For example, while our data indicated the combination of obesity and genetic predisposition resulted in an additional 29% of cases of incident female gout (above-and-beyond the background rate), this 29% would not occur if one of these factors (namely obesity, the modifiable one) were absent. Successful interventions for achieving and maintaining a healthy weight could be tailored towards an individual’s comorbidity profile and personal preferences.14 15 For example, in our recent ancillary analysis of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT),71 three established healthy weight loss diets (Mediterranean, low-fat, and low-carbohydrate) each resulted in considerable reductions in serum urate levels, particularly among those at risk with baseline hyperuricemia (by 1.9 to 2.4 mg/dL by 6 months and 1.1 to 1.4 mg/dL by 24 months), which were mediated by significant reductions in body weight and plasma insulin levels.72 The addition of physical activity to these healthy diets may further mitigate gout risk through the direct effects on BMI73 or indirect effects on insulin resistance.15 74

Strengths and limitations of study

Strengths of our study included the sex-specific analysis of large cohorts of females, and replication of our findings in another female cohort, the NHS II, and comparison to male counterparts (HPFS). Another important focus of our study is the absolute risk (additive) scale, which has greater implications for population health32-34 75 as applied to related endpoints.35-38 55 76 In fact, the absence of a significant multiplicative interaction between exposure (e.g., relative risk ratio not significantly different between exposure groups) can mislead about the impact of joint exposures; a significant additive interaction still implies that a larger number of cases is expected when the group with one deleterious risk factor is exposed to a second deleterious factor. The FFQs and other instruments for collecting covariate data have been well validated in these cohorts, 41-45 47 48 77 and participants’ height and weight data were found to be highly reliable.47 We collected biennial measures of BMI and a comprehensive set of other health and lifestyle factors repeatedly, thus minimising measurement error. Moreover, our prospective collection of exposure data, before gout diagnosis, eliminated the potential for recall bias and gave the rare opportunity to prospectively assess the interactions between gout-risk genes and BMI measured before diagnosis, unlike previous cross-sectional studies with unclear temporal relations with BMI and relevant lifestyle covariates.67 78-80 However, despite our comprehensive adjustment for covariates, these findings are subject to potential residual and unmeasured confounding, like with any observational study. Although the absolute rates of gout and the distribution of adiposity of our cohorts may not be representative of a random sample of Americans, all risk factors identified from our study cohorts have been consistently replicated as those for hyperuricemia in the US general population based on the NHANES.9 40 49 51 53 81-90 Furthermore, similar associations, including those for BMI and the risk of gout,91 have been reported in somewhat older-aged, sociodemographically diverse cohorts such as the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study in the US (e.g., age 45 to 64 years at baseline, 25% African American, 40% with annual household income ≤ $25,00092).

In these prospective female cohorts, both excess adiposity and genetic predisposition were strongly associated with a higher risk of gout, and the excess risk of both combined was higher than the sum of each, whereas a weaker interaction was present in male counterparts. These findings suggest addressing excess adiposity could prevent a large proportion of female gout cases in particular, as well as its cardiometabolic comorbidities, and the benefit could be greater in genetically predisposed women.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

What is already known about this subject?

The global gout burden is rising disproportionately in women, a historically overlooked population.

Excess adiposity is a major risk factor for the development of gout; women with gout have had a higher prevalence of obesity than men with gout in prior cross-sectional studies.

Gout is driven substantially by genetics with serum urate heritability estimates ranging from 25% to 60%.

What does this study add?

The combination of higher genetic predisposition and overweight or obesity imposes an excess risk of incident gout, one larger than the sum of each exposure alone, particularly among women.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

Keeping a healthy body weight would be especially important for prevention of female gout, particularly those genetically predisposed.

Funding:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [P50 AR060772, R01 AR065944, R01 AR056291, U01 CA167552, UM1 CA186107, and U01 CA176726]. NM was supported by a Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CY was supported by the National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Award [T32 AR007258] and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. GC is supported by the National Institutes of Health [K24 DK091417].

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: All authors have completed the ICMJE form for competing interests disclosure. NM, CY, NL, and ADJ have no competing interests to declare. HKC reports research support from Ironwood and Horizon, and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. GC reports research support from Decibel Therapeutics, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Allena Pharmaceuticals, Shire/Takeda, Dicerna, and Orfan, and is the Chief Medical Officer at OM1, Inc.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Mass General Brigham (protocol # 2000P002515).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007-2008. American Journal of Medicine 2012;125(7):679–87 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia Y, Wu Q, Wang H, et al. Global, regional and national burden of gout, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(7):1529–38. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez476 [published Online First: 2019/10/19] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Cross M, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Years Lived With Disability Due to Gout and Its Attributable Risk Factors for 195 Countries and Territories 1990-2017: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Arthritis & rheumatology 2020. doi: 10.1002/art.41404 [published Online First: 2020/08/06] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Te Kampe R, Janssen M, van Durme C, et al. Sex Differences in the Clinical Profile Among Patients With Gout: Cross-sectional Analyses of an Observational Study. J Rheumatol 2021;48(2):286–92. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200113 [published Online First: 2020/07/03] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrold LR, Yood RA, Mikuls TR, et al. Sex differences in gout epidemiology: evaluation and treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65(10):1368–72. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.051649 [published Online First: 2006/04/29] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drivelegka P, Sigurdardottir V, Svard A, et al. Comorbidity in gout at the time of first diagnosis: sex differences that may have implications for dosing of urate lowering therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1596-x [published Online First: 2018/06/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrold LR, Etzel CJ, Gibofsky A, et al. Sex differences in gout characteristics: tailoring care for women and men. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1465-9 [published Online First: 2017/03/16] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puig JG, Michan AD, Jimenez ML, et al. Female gout. Clinical spectrum and uric acid metabolism. Arch Intern Med 1991;151(4):726–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(7):742–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roubenoff R, Klag MJ, Mead LA, et al. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. JAMA 1991;266(21):3004–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormick N, Rai SK, Lu N, et al. Estimation of Primary Prevention of Gout in Men Through Modification of Obesity and Other Key Lifestyle Factors. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(11):e2027421. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27421 [published Online First: 2020/11/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen SM, Bartels EM, Henriksen M, et al. Weight loss for overweight and obese individuals with gout: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2017;76(11):1870–82. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maglio C, Peltonen M, Neovius M, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on gout incidence in the Swedish Obese Subjects study: a non-randomised, prospective, controlled intervention trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2017;76(4):688–93. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokose C, McCormick N, Choi HK. The role of diet in hyperuricemia and gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021;33(2):135–44. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000779 [published Online First: 2021/01/06] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokose C, McCormick N, Choi HK. Dietary and Lifestyle-Centered Approach in Gout Care and Prevention. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2021;23(7):51. doi: 10.1007/s11926-021-01020-y [published Online First: 2021/07/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fam AG. Gout, diet, and the insulin resistance syndrome. The Journal of rheumatology 2002;29(7):1350–5. [published Online First: 2002/07/26] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;334(7):445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emmerson BT. Alteration of urate metabolism by weight reduction. Aust N Z J Med 1973;3(4):410–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modan M, Halkin H, Fuchs Z, et al. Hyperinsulinemia--a link between glucose intolerance, obesity, hypertension, dyslipoproteinemia, elevated serum uric acid and internal cation imbalance. Diabete Metab 1987;13(3 Pt 2):375–80. [published Online First: 1987/07/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facchini F, Chen YD, Hollenbeck CB, et al. Relationship between resistance to insulin-mediated glucose uptake, urinary uric acid clearance, and plasma uric acid concentration. JAMA 1991;266(21):3008–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita S, Matsuzawa Y, Tokunaga K, et al. Studies on the impaired metabolism of uric acid in obese subjects: marked reduction of renal urate excretion and its improvement by a low-calorie diet. Int J Obes 1986;10(4):255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormick N, O'Connor MJ, Yokose C, et al. Assessing the Causal Relationships between Insulin Resistance and Hyperuricemia and Gout Using Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization. Arthritis & rheumatology 2021. doi: 10.1002/art.41779 [published Online First: 2021/05/14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyngdoh T, Vuistiner P, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS One 2012;7(6):e39321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039321 [published Online First: 2012/06/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Si S, Tewara MA, Li Y, et al. Causal Pathways from Body Components and Regional Fat to Extensive Metabolic Phenotypes: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(8):1536–49. doi: 10.1002/oby.22857 [published Online First: 2020/09/17] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer TM, Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, et al. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 2013;347:f4262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4262 [published Online First: 2013/07/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson SC, Burgess S, Michaelsson K. Genetic association between adiposity and gout: a Mendelian randomization study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57(12):2145–48. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key229 [published Online First: 2018/08/08] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topless RKG, Major TJ, Florez JC, et al. The comparative effect of exposure to various risk factors on the risk of hyperuricaemia: diet has a weak causal effect. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02444-8 [published Online First: 2021/03/06] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehghan A, Kottgen A, Yang Q, et al. Association of three genetic loci with uric acid concentration and risk of gout: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 2008;372(9654):1953–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tin A, Marten J, Halperin Kuhns VL, et al. Target genes, variants, tissues and transcriptional pathways influencing human serum urate levels. Nat Genet 2019;51(10):1459–74. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0504-x [published Online First: 2019/10/04] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kottgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nature genetics 2013;45(2): 145–54. doi: 10.1038/ng.2500 [published Online First: 2012/12/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narang RK, Topless R, Cadzow M, et al. Interactions between serum urate-associated genetic variants and sex on gout risk: analysis of the UK Biobank. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1787-5 [published Online First: 2019/01/11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ. Synergy and antagonism in cause-effect relationships. Am J Epidemiol 1974;99(6):385–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121626 [published Online First: 1974/06/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Closas M, Rothman N, Figueroa JD, et al. Common genetic polymorphisms modify the effect of smoking on absolute risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Res 2013;73(7):2211–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2388 [published Online First: 2013/03/29] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ. A Tutorial on Interaction. Epidemiol Methods 2014; 3(1): 33–72 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Ley SH, Tobias DK, et al. Birth weight and later life adherence to unhealthy lifestyles in predicting type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2015;351:h3672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3672 [published Online First: 2015/07/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shan Z, Li Y, Zong G, et al. Rotating night shift work and adherence to unhealthy lifestyle in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes: results from two large US cohorts of female nurses. BMJ 2018;363:k4641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4641 [published Online First: 2018/11/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timpka S, Stuart JJ, Tanz LJ, et al. Lifestyle in progression from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to chronic hypertension in Nurses' Health Study II: observational cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j3024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3024 [published Online First: 2017/07/14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui J, Raychaudhuri S, Karlson EW, et al. Interactions Between Genome-Wide Genetic Factors and Smoking Influencing Risk of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis & rheumatology 2020;72(11): 1863–71. doi: 10.1002/art.41414 [published Online First: 2020/09/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health 1997;6(1):49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49 [published Online First: 1997/02/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med 2004;350(11):1093–103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035700 [published Online First: 2004/03/12] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology 1985; 122(1):51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. American Journal of Epidemiology 1992; 135(10):1114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, et al. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 1993;93(7):790–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, et al. Validity of a Dietary Questionnaire Assessed by Comparison With Multiple Weighed Dietary Records or 24-Hour Recalls. Am J Epidemiol 2017;185(7):570–84. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww104 [published Online First: 2017/03/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Shaar L, Yuan C, Rosner B, et al. Reproducibility and Validity of a Semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire in Men Assessed by Multiple Methods. Am J Epidemiol 2020. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi Q, Chu AY, Kang JH, et al. Fried food consumption, genetic risk, and body mass index: gene-diet interaction analysis in three US cohort studies. BMJ 2014;348:g1610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1610 [published Online First: 2014/03/22] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1990;1(6):466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology 1987;126(2):319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Alcohol Intake and Risk of Incident Gout in Men - A Prospective Study. Lancet 2004;363:1277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hak AE, Curhan GC, Grodstein F, et al. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and risk of incident gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69(7):1305–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.109884 [published Online First: 2009/07/14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. Bmj 2008;336(7639):309–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Risk Factors for Incident Gout in a Large, Long-Term, Prospective Cohort Study. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2003;48(9S):S680. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA 2010;304(20):2270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joshi AD, Lindstrom S, Husing A, et al. Additive interactions between susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified in genome-wide association studies and breast cancer risk factors in the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180(10):1018–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu214 [published Online First: 2014/09/27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim J, Wirth J, Wu K, et al. Obesity, Adiposity, and Risk of Symptomatic Gallstone Disease According to Genetic Susceptibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.044 [published Online First: 2021/07/05] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.VanderWeele TJ, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ. Attributing effects to interactions. Epidemiology 2014;25(5):711–22. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000096 [published Online First: 2014/07/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Confidence interval estimation of interaction. Epidemiology 1992;3(5):452–6. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00012 [published Online First: 1992/09/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41(2):514–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr218 [published Online First: 2012/01/19] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wacholder S, Benichou J, Heineman EF, et al. Attributable risk: advantages of a broad definition of exposure. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140(4):303–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117252 [published Online First: 1994/08/15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Mutsert R, Jager KJ, Zoccali C, et al. The effect of joint exposures: examining the presence of interaction. Kidney Int 2009;75(7):677–81. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.645 [published Online First: 2009/02/05] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dalbeth N, Phipps-Green A, Frampton C, et al. Relationship between serum urate concentration and clinically evident incident gout: an individual participant data analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77(7):1048–52. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212288 [published Online First: 2018/02/22] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strohacker K, Wing RR, McCaffery JM. Contributions of body mass index and exercise habits on inflammatory markers: a cohort study of middle-aged adults living in the USA. BMJ Open 2013;3(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002623 [published Online First: 2013/06/26] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ix JH, Sharma K. Mechanisms linking obesity, chronic kidney disease, and fatty liver disease: the roles of fetuin-A, adiponectin, and AMPK. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2010;21(3):406–12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009080820 [published Online First: 2010/02/13] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao J, Miyamoto S, You YH, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation inhibits nuclear translocation of Smad4 in mesangial cells and diabetic kidneys. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2015;308(10):F1167–77 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00234.2014 [published Online First: 2014/11/28] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Decleves AE, Mathew AV, Cunard R, et al. AMPK mediates the initiation of kidney disease induced by a high-fat diet. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2011;22(10):1846–55. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010026 [published Online First: 2011/09/17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, et al. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN 2012;7(12):1938–46. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03500412 [published Online First: 2012/10/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tai V, Narang RK, Gamble G, et al. Do Serum Urate-Associated Genetic Variants Differentially Contribute to Gout Risk According to Body Mass Index? Analysis of the UK Biobank. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72(7):1184–91. doi: 10.1002/art.41219 [published Online First: 2020/02/06] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu Y, Yang J, Fu S, et al. Leptin Promotes Monosodium Urate Crystal-Induced Inflammation in Human and Murine Models of Gout. J Immunol 2019;202(9):2728–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801097 [published Online First: 2019/03/31] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Terkeltaub R. What makes gouty inflammation so variable? BMC medicine 2017;15(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0922-5 [published Online First: 2017/08/19] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y, Viollet B, Terkeltaub R, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses urate crystal-induced inflammation and transduces colchicine effects in macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 2014. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206074 [published Online First: 2014/11/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;359(3):229–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681 [published Online First: 2008/07/19] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yokose C, McCormick N, Rai SK, et al. Effects of Low-Fat, Mediterranean, or Low-Carbohydrate Weight Loss Diets on Serum Urate and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Secondary Analysis of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT). Diabetes Care 2020:dc201002. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams PT. Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87(5):1480–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gepner Y, Shelef I, Schwarzfuchs D, et al. Effect of Distinct Lifestyle Interventions on Mobilization of Fat Storage Pools: CENTRAL Magnetic Resonance Imaging Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2018;137(11):1143–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030501 [published Online First: 2017/11/17] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blot WJ, Day NE. Synergism and interaction: are they equivalent? Am J Epidemiol 1979;110(1):99–100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112793 [published Online First: 1979/07/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim K, Jiang X, Cui J, et al. Interactions between amino acid-defined major histocompatibility complex class II variants and smoking in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & rheumatology 2015;67(10):2611–23. doi: 10.1002/art.39228 [published Online First: 2015/06/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giovannucci E, Colditz G, Stampfer MJ, et al. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology 1991;133(8):810–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brandstatter A, Kiechl S, Kollerits B, et al. Sex-specific association of the putative fructose transporter SLC2A9 variants with uric acid levels is modified by BMI. Diabetes Care 2008;31(8):1662–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huffman JE, Albrecht E, Teumer A, et al. Modulation of genetic associations with serum urate levels by body-mass-index in humans. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0119752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119752 [published Online First: 2015/03/27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li WD, Jiao H, Wang K, et al. A genome wide association study of plasma uric acid levels in obese cases and never-overweight controls. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(9):E490–4. doi: 10.1002/oby.20303 [published Online First: 2013/05/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of Purine-Rich Foods, Protein, Dairy Products, and Serum Uric Acid Level - The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52(1):283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi HK, Curhan G. Beer, Liquor, Wine, and Serum Uric Acid Level - The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51(6):1023–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao X, Qi L, Qiao N, et al. Intake of added sugar and sugar-sweetened drink and serum uric acid concentration in US men and women. Hypertension 2007;50(2):306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, et al. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59(1):109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nguyen S, Choi HK, Lustig RH, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, serum uric acid, and blood pressure in adolescents. J Pediatr 2009;154(6):807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and serum uric acid level: The third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57(5):816–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in men: A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56(6):2049–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2010. 92(4):922–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gao X, Curhan G, Forman JP, et al. Vitamin C Intake and Serum Uric Acid Concentration in Men. J Rheumatol 2008;35(9):1853–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Choi HK, Gao X, Curhan G. Vitamin C intake and the risk of gout in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(5):502–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maynard JW, McAdams DeMarco MA, Baer AN, et al. Incident gout in women and association with obesity in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Med 2012;125(7):717 e9–17 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.018 [published Online First: 2012/05/11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.ARIC. Cohort Description [Available from: https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/aric/Cohort_Description.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.