Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to explore the mechanisms of Hippophae fructus oil (HFO) in the treatment of tympanic membrane (TM) perforation through network pharmacology‐based identification.

Methods

The compounds and related targets of HFO were extracted from the TCMSP database, and disease information was obtained from the OMIM, GeneCards, PharmGkb, TTD, and DrugBank databases. A Venn diagram was generated to show the common targets of HFO and TM, and GO and KEGG analyses were performed to explore the potential biological processes and signaling pathways. The PPI network and core gene subnetwork were constructed using the STRING database and Cytoscape software. A molecular docking analysis was also conducted to simulate the combination of compounds and gene proteins.

Results

A total of 33 compounds and their related targets were obtained from the TCMSP database. After screening the 393 TM‐related targets, 21 compounds and 22 gene proteins were selected to establish the network diagram. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses revealed that HFO may promote TM healing by influencing cellular oxidative stress and related signaling pathways. A critical subnetwork was obtained by analyzing the PPI network with nine core genes: CASP3, MMP2, IL1B, TP53, EGFR, CXCL8, ESR1, PTGS2, and IL6. In addition, a molecular docking analysis revealed that quercetin strongly binds the core proteins.

Conclusion

According to the analysis, HFO can be utilized to repair perforations by influencing cellular oxidative stress. Quercetin is one of the active compounds that potentially plays an important role in TM regeneration by influencing 17 gene proteins.

Keywords: Hippophae fructus, molecular docking, network pharmacology, tympanic membrane perforation, wound healing

The mechanism of hippophae fructus oil in treatment of tympanic membrane perforations was explored by the technology of network pharmacology and molecular docking. Hippophae fructus oil may repair perforations by influencing the regulation of cellular oxidative stress, and the quercetin may be one of the possibly effective compounds in tympanic membrane repair. This study provided a novel idea to explore new drugs in tympanic membrane repair.

1. INTRODUCTION

Tympanic membrane (TM) perforation is a common finding in otology clinics that causes hearing loss and infections and consequently decreases the quality of human life. 1 , 2 Persistent TM perforation with infection, if left untreated, usually requires surgical interventions. 2 , 3 Patients who undergo tympanoplasty may suffer from pain and potential postoperative complications and might incur high medical costs. 3 , 4 For simple perforations without other middle ear disorders (e.g., cholesteatoma), an alternative to rupture closure that is less invasive and expensive is preferable to surgical intervention. 5 , 6 , 7

Hippophae fructus oil (HFO), a traditional Chinese herb extracted from Hippophae fructus, 8 , 9 , 10 is composed of vitamin C, amino acids, and essential trace elements (e.g., zinc), which can enhance the proliferation of TM epithelial stem cells, promote their migration to lesions and induce blood vessel dilatation. 9 , 10 During the past few decades, HFO has been applied for the clinical treatment of TM perforation with satisfactory outcomes. 8 However, the biological mechanism of HFO therapy for TM regeneration remains unclear, and the main compounds of HFO that promote TM healing require further exploration.

The development of biological informatics engineering has made it possible to explore the mechanisms of Chinese herbs used for disease treatment. Network pharmacology combines pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties with the field of systems biology to study drugs, protein targets, and their pharmacological activities. 11 , 12 Hence, we explored the underlying mechanism of HFO in TM repair using the technologies of network pharmacology and molecular docking.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Identification of active compounds of HFO and corresponding target genes

Detailed information on the compounds, targets and other secondary data related to HFO was obtained from the Traditional Chinese Medicine System Pharmacology Database (TCMSP, http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php) with the keywords Hippophae Fructus. 13 Specifically, oral bioavailability (OB) and drug likeness (DL), which are the most important indicators for evaluating the characteristics of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), were used to filter the candidate active compounds based on the thresholds OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18. 14 For each active compound, we searched related target genes in the TCMSP database. An HFO gene set was then mapped using the UniProt database by limiting the species to “Homo sapiens” (https://www.uniprot.org/) to obtain gene symbol annotation. 15

2.2. Obtainment of the target genes related to TM

The TM‐related targets were mined by searching the following five databases: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM; https://omim.org/) database, 16 GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) database, 17 PharmGkb (https://www.pharmgkb.org/) database, 18 Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (http://db.idrblab.net/ttd/), 19 and DrugBank (https://www.drugbank.ca/) database. 20 A TM‐related gene set was established by combining the search results.

2.3. Compound‐target pharmacology network and functional analysis

After preparing two sets of target lists for the HFO‐related genes and disease targets, a screening for drug‐disease crossover was performed. The common targets were selected, and a Venn diagram was generated using the Venn Diagram package of R software to visualize the intersection sets. The compound‐target‐disease network diagram was prepared using Cytoscape version 3.8.0 software to show the relationships among the TM, HFO, and gene targets. 21

A functional enrichment analysis, including gene ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, was performed to elucidate the underlying mechanism through assessments of biological processes (BPs), cellular components (CCs), molecular functions (MFs), and key signaling pathways. The intersecting proteins were then evaluated by bioinformatics annotation using the “clusterProfiler” and “bioconductor” packages of R software. The significantly enriched GO and KEGG terms were identified, and p‐values < 0.05 and q‐values < 0.05 indicated a strong association with related BPs. 22 , 23

2.4. Protein–protein interaction network and critical subnetwork

For identification of the potential targets of HFO and the interactions between them, the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) (http://string‐db.org/) database 24 was used to analyze the intersecting protein–protein interactions (PPIs) through the intersection set between HFO targets and TM‐related genes. After importing the PPI network into Cytoscape software, a critical subnetwork was investigated using the CytoNCA plugin. 25 The values of betweenness, closeness, degree, eigenvector, and local average connectivity‐based method, as well as the network scores, were independently calculated, and the eligible genes with scores higher than the median value were selected to establish a critical subnetwork. 25

2.5. Molecule docking technology

The compound with the largest number of critical genes related to TM was selected for further analysis based on molecular docking. The 2D structure of the molecular ligands was downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), 26 and the 3D structure with minimum energy was calculated and exported using ChemBio3D software. 27 Furthermore, the 3D structure of the receptor protein encoded by the selected gene was obtained from the UniProt database and downloaded from the RCSB PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). 28

After preparing the files of the 3D structure, the receptor proteins were dehydrated, and the ligands were removed using PyMOL software. 29 AutoDock Tools was used to modify the receptor protein by calculating the hydrogenation and charges of proteins. Moreover, the parameters of the receptor protein docking site were set to include the active pocket sites where small molecule ligands bind, and the molecular docking between the compound and receptor proteins was displayed using AutoDock Vina software. 30

3. RESULTS

3.1. Active compounds and potential targets

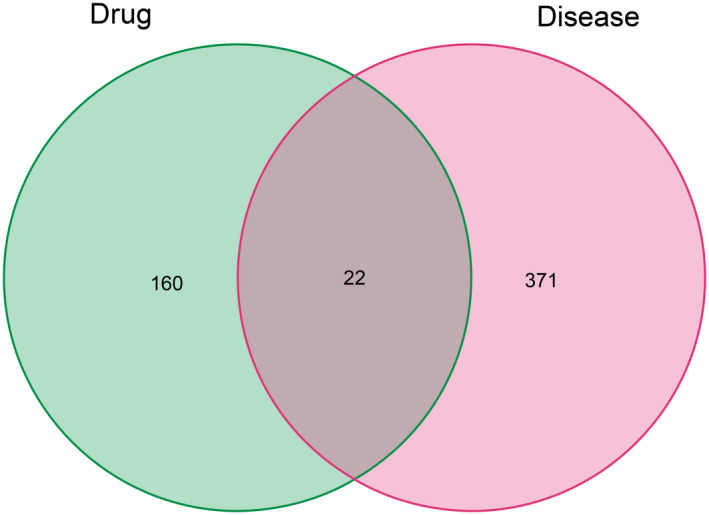

Using the criteria DL ≥ 0.18 and OB ≥ 30%, 33 main and effective compounds were retrieved and selected (Table 1). A total of 182 compound‐related targets were annotated into a gene symbol set using the UniProt database. In addition, 393 TM‐related targets were extracted from the OMIM, GeneCards, PharmGkb, TTD, and DrugBank databases after removing duplicates. Moreover, an intersection of the compound‐target and disease‐related genes, which contained 22 target proteins, was obtained and is shown in Figure 1.

TABLE 1.

Active compounds of hippophae fructus

| Mol ID | Molecule name | OB (%) | DL |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOL001004 | Pelargonidin | 37.98831233 | 0.21204 |

| MOL010211 | 14,15‐dimethyl‐alpha‐sitosterol | 43.13700612 | 0.78478 |

| MOL010212 | 14‐methyl‐alpha‐sitosterol | 43.48505263 | 0.78028 |

| MOL010227 | Canthaxanthine | 41.58914575 | 0.56161 |

| MOL010228 | Carotenoid | 40.75960813 | 0.54932 |

| MOL010230 | ST5330591 | 48.07729226 | 0.84329 |

| MOL010232 | Cislycopene | 45.51347546 | 0.54476 |

| MOL010234 | Delta‐Carotene | 31.80094312 | 0.54639 |

| MOL010240 | Ergosta‐7‐en‐3‐beta‐ol | 38.76055617 | 0.82626 |

| MOL010241 | Ergostenol | 35.40870144 | 0.71393 |

| MOL010247 | (2R,6S,7aR)‐2‐[(1E,3E,5E,7E,9E,11E,13E,15E)‐16‐[(1R,4R)‐4‐hydroxy‐2,6,6‐trimethyl‐1‐cyclohex‐2‐enyl]‐1,5,10,14‐tetramethylhexadeca‐1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15‐octaenyl]‐2,4,4,7a‐tetramethyl‐6,7‐dihydro‐5H‐benzofuran‐6‐ol | 57.88019692 | 0.52897 |

| MOL010248 | Gamma‐carotene | 30.98275266 | 0.55342 |

| MOL001979 | LAN | 42.11918897 | 0.74787 |

| MOL010267 | LYC | 32.57391809 | 0.50916 |

| MOL010283 | ZINC03831331 | 47.60362222 | 0.65038 |

| MOL001420 | ZINC04073977 | 37.99618556 | 0.75755 |

| MOL001494 | Mandenol | 41.99620045 | 0.19321 |

| MOL001510 | 24‐epicampesterol | 37.57681789 | 0.71413 |

| MOL002268 | Rhein | 47.06520991 | 0.27678 |

| MOL002588 | (3S,5R,10S,13R,14R,17R)‐17‐[(1R)‐1,5‐dimethyl‐4‐methylenehexyl]‐4,4,10,13,14‐pentamethyl‐2,3,5,6,7,11,12,15,16,17‐decahydro‐1H‐cyclopenta[a]phenanthren‐3‐ol | 42.36819868 | 0.76765 |

| MOL002773 | Beta‐carotene | 37.18433337 | 0.58358 |

| MOL000354 | Isorhamnetin | 49.60437705 | 0.306 |

| MOL000358 | Beta‐sitosterol | 36.91390583 | 0.75123 |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91390583 | 0.7512 |

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88224954 | 0.24066 |

| MOL000433 | FA | 68.96043622 | 0.7057 |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | 43.82985158 | 0.75665 |

| MOL000492 | (+)‐catechin | 54.82643405 | 0.24164 |

| MOL005100 | 5,7‐dihydroxy‐2‐(3‐hydroxy‐4‐methoxyphenyl)chroman‐4‐one | 47.73643694 | 0.27226 |

| MOL006756 | Schottenol | 37.42312067 | 0.75067 |

| MOL000073 | Ent‐Epicatechin | 48.95984114 | 0.24162 |

| MOL000953 | CLR | 37.87389754 | 0.67677 |

| MOL000098 | Quercetin | 46.43334812 | 0.27525 |

Abbreviations: OB, oral bioavailability; DL, drug likeness.

FIGURE 1.

Venn diagram of gene intersections between HFO and TM perforation. HFO, Hippophae fructus oil; TM, tympanic membrane

3.2. Network analysis of targets

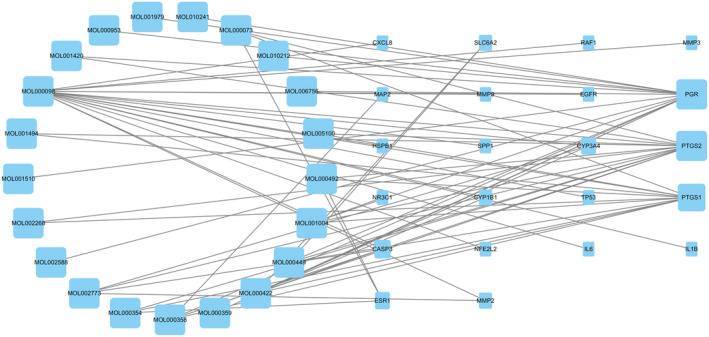

A compound–disease–target interaction network with 43 nodes and 66 edges was visualized using Cytoscape software. The possible effective compounds of HFO related to TM perforation repair are the following: pelargonidin, 14‐methyl‐alpha‐sitosterol, ergosterol, LAN, ZINC04073977, mandenol, 24‐epicampesterol, rhein, beta‐carotene, isorhamnetin, beta‐sitosterol, sitosterol kaempferol, stigmasterol, (+)‐catechin, schottenol, ent‐epicatechin, CLR, quercetin, (3S,5R,10S,13R,14R,17R)‐17‐((1R)‐1,5‐dimethyl‐4‐methylenehexyl)‐4,4,10,13,14‐pentamethyl‐2,3,5,6,7,11,12,15,16,17‐decahydro‐1H‐cyclopenta(a)phenanthren‐3‐ol, and 5,7‐dihydroxy‐2‐(3‐hydroxy‐4‐methoxyphenyl)methoxy‐chroman‐4. Moreover, the 22 related gene proteins were PTGS1, PTGS2, PGR, NR3C1, MMP2, CASP3, CYP3A4, ESR1, MAP2, SLC6A2, CYP1B1, MMP3, EGFR, MMP9, IL6, TP53, RAF1, IL1B, CXCL8, HSPB1, NFE2L2, and SPP1.

As shown in Figure 2, PTGS2 and PGR were identified as two genes that were most frequently targeted by the HFO ingredients, and both of these genes were targeted by 13 active compounds. Furthermore, quercetin may be one of the primary therapeutic compounds affecting 17 target proteins on the TM and may play a critical role in the healing process.

FIGURE 2.

HFO‐compounds‐targets‐TM perforation network diagram. HFO, Hippophae fructus oil; TM, tympanic membrane

3.3. GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

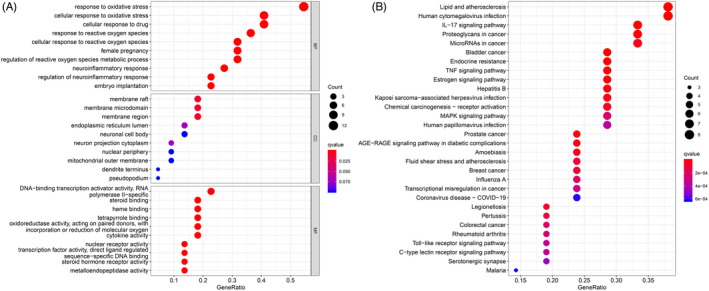

The GO enrichment analysis revealed the underlying BPs, CCs, and MFs of the 22 target genes. Using the criteria p‐value < 0.05 and q‐value < 0.05, a total of 1208 significantly enriched GO terms were obtained. The top 10 terms are illustrated in Figure 3. The analysis of BPs revealed that the targets were enriched in different GO terms, and the predicted therapeutic targets were mainly associated with three BPs, namely response to oxidative stress, cellular response to oxidative stress, and cellular response to drugs; three CCs, namely membrane raft, membrane microdomain, and membrane region; and one MF, namely DNA‐binding transcription activator activity (RNA polymerase II−specific).

FIGURE 3.

GO (A) and KEGG (B) enrichment analysis. GO, gene ontology; HEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Using the filters p‐value < 0.05 and q‐value < 0.05, a KEGG enrichment analysis was performed to elucidate the related pathways. The results revealed that 103 potential signaling pathways were enriched, and the top 30 of these pathways are shown in Figure 3. The bubble plot demonstrates that these gene targets affected pathways related to infection and wound healing, such as the IL‐17 signaling pathway.

3.4. PPI diagram and core subnetwork

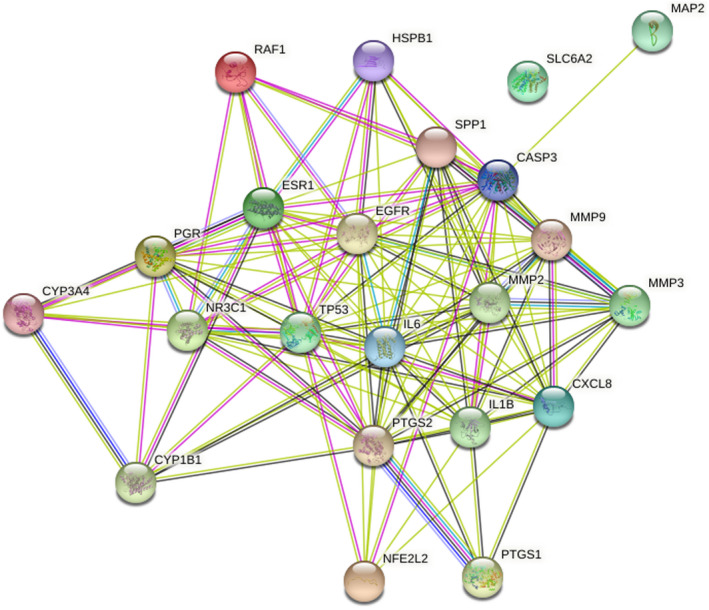

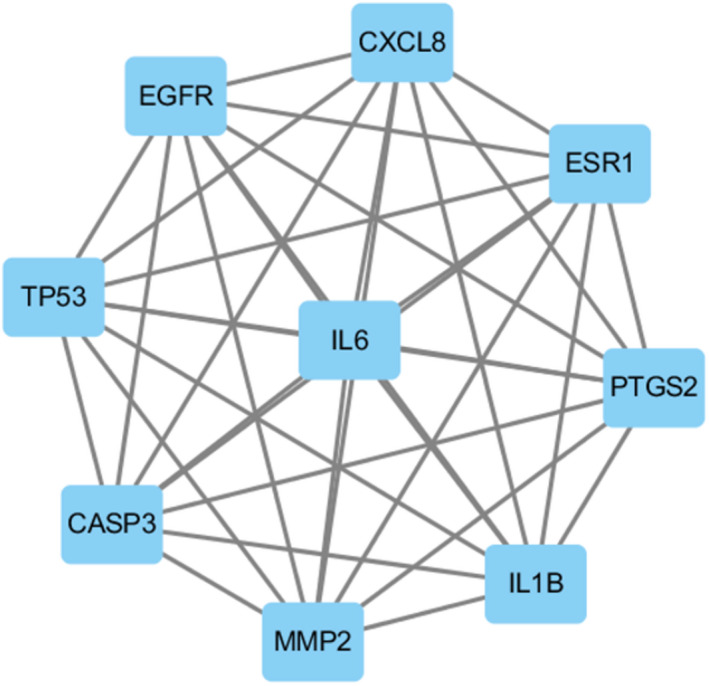

Twenty‐two overlapping genes associated with TM and HFO were inputted into the STRING database, and a PPI network diagram was established after selecting “Homo sapiens.” As shown in Figure 4, the network contained 22 nodes and 123 edges. In addition, while importing the results from the PPI network into Cytoscape and using the CytoNCA plugin, a further core subnetwork that contained nine nodes and 36 edges was obtained (Figure 5). These nine core gene targets included CASP3, MMP2, IL1B, TP53, EGFR, CXCL8, ESR1, PTGS2, and IL6. The results from the GO and KEGG analyses revealed that the core genes are involved in the cellular response to oxidative stress and play critical roles in signaling pathways. Detailed information on the compounds is summarized in Table 2.

FIGURE 4.

Protein–protein interactions diagram

FIGURE 5.

Core proteins subnetwork diagram

TABLE 2.

Core proteins and related active compounds

| Targets | Compounds |

|---|---|

| CASP3 | Beta‐carotene; beta‐sitosterol; kaempferol; quercetin |

| EGFR | Quercetin |

| MMP2 | Beta‐carotene; quercetin |

| TP53 | Quercetin |

| PTGS2 |

Pelargonidin; ZINC04073977; Mandenol; rhein; beta‐carotene; isorhamnetin; beta‐sitosterol; kaempferol; Stigmasterol; (+)‐catechin; 5,7‐dihydroxy‐2‐(3‐hydroxy‐4‐methoxyphenyl) chroman‐4‐one; ent‐Epicatechin; quercetin |

| IL1B | Quercetin |

| CXCL8 | Quercetin |

| ESR1 | Isorhamnetin; (+)‐catechin; ent‐Epicatechin |

| IL6 | Quercetin |

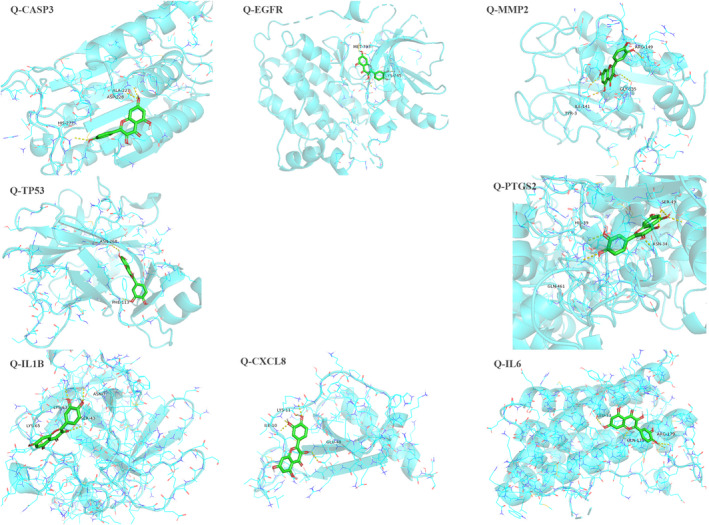

3.5. Molecular docking

Referring to the results of the core gene network, we identified quercetin as a ligand of CASP3, MMP2, IL1B, TP53, EGFR, CXCL8, PTGS2, and IL6 protein receptors. A further calculation was then conducted to simulate the molecular docking of quercetin with these eight gene proteins, and the docking affinity values are listed in Table 3. A greater absolute value for the docking affinity indicates stronger binding ability between the active site of the protein receptor and the compound. The docking results indicate that quercetin can easily enter and bind the active pocket of the eight core target proteins, can form hydrogen bonds with the amino acid residues, and exhibits high binding affinity (Figure 6).

TABLE 3.

Detailed results for molecular docking

| Targets | PDB code | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| CASP3 | 2DKO | −6.7 |

| EGFR | 2RGP | −8.7 |

| MMP2 | 3AYU | −8.6 |

| TP53 | 2PCX | −7.0 |

| PTGS2 | 5KIR | −9.6 |

| IL1B | 5R7W | −7.2 |

| CXCL8 | 3IL8 | −5.9 |

| IL6 | 1ALU | −6.9 |

FIGURE 6.

Visualized results for molecular docking

4. DISCUSSION

Tympanic membrane perforation can lead to severe morbidity and disability. 2 , 3 With the development of tissue engineering, various bioactive materials (e.g., growth factors) have been used as a replacement to conventional tympanoplasty in the treatment of simple TM perforations with great success rates. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 However, these molecules have their own limitations, such as otorrhea caused by a high dosage of growth factors, and an ideal bioactive material has not yet been identified. 2 , 7 In traditional Chinese medicine, doctors use Chinese herbs to repair TM perforations, and these herbs have been reported to accelerate the wound healing process. 31 , 32 , 33 Previous studies have suggested that HFO may be an effective, safe and convenient herb for promoting the healing of TM perforations. 8 However, the underlying mechanism of HFO in TM repair remains unknown. Thus, in this study, we performed a network pharmacology‐based analysis to explore the mechanism of HFO in TM repair.

The results from the GO enrichment analysis revealed that the mechanism through which HFO promotes TM regeneration may be associated with cellular oxidative stress. During the process of tissue wound healing, the biological regulation of cellular oxidative stress generally plays a critical role in cell proliferation and migration. 34 , 35 The signaling pathways identified from the KEGG enrichment analysis also suggested that these gene proteins may contribute to this biological process. Although the healing process of the TM differs from that of other tissues and despite the lack of direct evidence regarding the relationship of TM healing with oxidative stress, previous studies have indicated that individuals with chronic otitis media (particularly those accompanied by middle ear cholesteatoma) exhibit higher levels of oxidative stress markers in both the discharge fluid and serum than normal controls. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 This evidence may support our finding that HFO may promote TM healing by regulating biological processes related to cellular oxidative stress.

The PPI network diagram reflected the protein–protein relationships among the 22 overlapping gene proteins. Moreover, a further critical subnetwork indicated that the nine core gene proteins might play a major role in the biological process of TM regeneration in response to HFO. Among these nine proteins, the EGFR gene protein reportedly plays an important role in TM healing. EGFR consists of an extracellular ligand‐binding domain, a transmembrane region, and an internal tyrosine kinase domain. This protein is localized in the basal layer of the stratified squamous epithelium of the TM and is involved in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation. 40 When the TM is perforated, growth factors (e.g., EGF) are secreted and bound by EGFR to induce the proliferation of epithelial and endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes. 40 The activation of EGFR can induce the transcription of regulatory proteins that stimulate proliferation and induce angiogenesis and also enhances the proliferation, adhesion, and migratory ability of TM cells. 41 Moreover, animal experiments suggest that the inhibition of EGFR may prolong the duration of TM regeneration due to its synergistic effects with growth factors. 42

In addition to the EGFR protein, other gene proteins also play important roles in the TM healing process. Among these core proteins, IL1B and IL6 participate in the process of histological damage and inflammation, as demonstrated with acute animal models. 43 , 44 The activity of MMP2 is also hypothesized to be involved in destruction of the TM fibrous layer and the prognosis of otitis media. 45 , 46

According to our analysis, 21 ingredients of HFO may contribute to the regeneration of the TM. Among these ingredients, quercetin can be considered the most likely active compound of HFO that promotes TM healing because it influences 17 gene proteins. Although no direct evidence shows the effectiveness of quercetin in TM regeneration, studies have revealed healing benefits from the application of quercetin to a wound both in vivo and in vitro. 47 Reportedly, quercetin has great antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory properties and can increase the wound contraction rate and protect tissues from oxidative damage. 48 , 49 , 50 According to our analysis, quercetin can act on EGFR, which is associated with the cellular proliferation of epithelial and endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes. When HFO is applied to perforated TMs, quercetin is potentially bound by EGFR to induce proliferation and migration. In addition to the biological effects of quercetin on wound healing, other effective compounds of HFO also display potential efficacy in TM healing. For instance, beta‐sitosterol reportedly produces the rapid re‐epithelialization of wounds and can exert a synergistic effect on quercetin. 51 In addition, as one of the trace elements with a high HFO content, zinc increases inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress production, granulation, and re‐epithelization via the regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and its association with tripartite motif family proteins during membrane repair and wound healing. 52 , 53 , 54

As a nonsurgical method for TM perforation treatment, HFO therapy can be easily administered in clinics. Gao et al utilized a sterile cotton patch with HFO to cover TM perforations. Similar to topical growth factor therapy, this treatment of traumatic perforations with HFO also does not require hospitalization, which results in less inconvenience and lower medical costs for the patients. 8 Moreover, HFO displays a variety of advantages in addition to healing benefits and is less invasive. 8 , 9 , 10 , 31 , 32 As an extract from berries and seeds of traditional medicinal plants, HFO is extensively available from many sources. In addition, HFO is easily prepared and does not require cold storage, which may significantly reduce the associated costs. In addition, this treatment has the ability to prevent ototoxicity and infection, which is crucial for TM healing and auditory reconstruction. 55

Although HFO shows great healing potential for TM perforations, the number of studies on the clinical application of HFO is not as high as that of studies that investigated other bioactive materials, which may be due to its complex composition and unknown mechanism related to the TM. 9 , 10 Therefore, further studies, if possible, should not only concentrate on exploring the underlying mechanism but also focus on a more detailed assessment of its clinical effectiveness. In addition to the healing and hearing results of HFO applied to acute or chronic perforations, the most effective dosage, duration and frequency of the application, and the patching materials have not yet been fully investigated. 1 , 4

In addition to exploring the mechanism and efficacy of HFO in further studies, investigations should assess whether the ingredients of this mixture can also be applied for TM regeneration based on our analysis. Quercetin, for instance, has been utilized as a medicine‐loaded vehicle for topical delivery in wound healing according to previous studies. 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 The ability to quench reactive oxygen species and mitigate the inflammatory process is essential in wound healing after topical application. 49 , 50 Considering these advantages, the utilization of quercetin has led to the novel notion of using herb monomers combined with other bioactive materials and has resulted in the identification of promising topical prodrugs.

In this study, we employed network pharmacology to elucidate the multitarget effects of HFO on TM perforations. Additionally, we discussed several potential herb monomers for TM perforation treatment, which could contribute to the development of new therapeutic strategies. However, the possible effects of HFO revealed from the network analysis require further verification by in vitro biological experiments. This analysis provides theoretical evidence regarding the mechanism of HFO in TM regeneration that can be further explored in future studies.

5. CONCLUSION

According to the analysis, HFO can be utilized to effectively repair TM perforations by influencing the regulation of cellular oxidative stress. Quercetin is one of the active compounds of HFP that potentially plays an important role in TM regeneration by influencing 17 gene proteins. This pharmacology‐based approach helps elucidate the underlying mechanisms of HFO in repairing TM perforations, but further experimental exploration is needed for verification of these mechanisms.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All persons designated as the authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content of the manuscript. All the authors ensured that they all gave substantial contributions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81670920), Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science Research Foundation (No. 2020RC107, No.2020KY274, and No.2022KY1086), Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (No. 2018A610363), and Ningbo Public Science Research Foundation (No. 2021S170).

Huang J, Teh BM, Xu Z, et al. The possible mechanism of Hippophae fructus oil applied in tympanic membrane repair identified based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. J Clin Lab Anal.2022;36:e24157. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24157

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from TCMSP, GeneCardS, OMIM, TTD, PharmGkb, and DrugBank belong to public databases.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shen Y, Redmond SL, Teh BM, et al. Tympanic membrane repair using silk fibroin and acellular collagen scaffolds. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1976‐1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang J, Teh BM, Zhou C, Shi Y, Shen Y. Tympanic membrane regeneration using platelet‐rich fibrin: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-06915-1. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang J, Teh BM, Shen Y. Butterfly cartilage tympanoplasty as an alternative to conventional surgery for tympanic membrane perforations: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021. doi: 10.1177/01455613211015439. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang J, Teh BM, Eikelboom RH, et al. The effectiveness of bFGF in the treatment of tympanic membrane perforations: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2020;41:782‐790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen Y, Redmond SL, Teh BM, et al. Scaffolds for tympanic membrane regeneration in rats. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:657‐668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang J, Shi Y, Wu L, Lv C, Hu Y, Shen Y. Comparative efficacy of platelet‐rich plasma applied in myringoplasty: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2021;161:e0245968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teh BM, Shen Y, Friedland PL, Atlas MD, Marano RJ. A review on the use of hyaluronic acid in tympanic membrane wound healing. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:23‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao TX, Li XL, Hu J, et al. Management of traumatic tympanic membrane perforation: a comparative study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:927‐931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao S, Guo Q, Qin CG, Shang R, Zhang Z. Sea buckthorn fruit oil extract alleviates insulin resistance through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in type 2 diabetes mellitus cells and rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:1328‐1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hou DD, Gu F, Liang ZF, Helland T, Weixin F, Liping C. Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) oil protects against chronic stress‐induced inhibitory function of natural killer cells in rats. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:76‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xia QD, Xun Y, Lu JL, et al. Network pharmacology and molecular docking analyses on Lianhua Qingwen capsule indicate Akt1 is a potential target to treat and prevent COVID‐19. Cell Prolif. 2020;53:e12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tao Q, Du J, Li X, et al. Network pharmacology and molecular docking analysis on molecular targets and mechanisms of Huashi Baidu formula in the treatment of COVID‐19. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46:1345‐1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ru JL, Li P, Wang JN, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminform. 2014;6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ning K, Zhao X, Poetsch A, Chen WH, Yang J. Computational molecular networks and network pharmacology. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7573904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The UniProt Consortium . UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158‐D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D789‐D798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rebhan M, Chalifa‐Caspi V, Prilusky J, Lancet D. GeneCards: integrating information about genes, proteins and diseases. Trends Genet. 1997;13:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barbarino JM, Whirl‐Carrillo M, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: a worldwide resource for pharmacogenomic information. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2018;10:e1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Zhang S, Li F, et al. Therapeutic target database 2020: enriched resource for facilitating research and early development of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D1031‐D1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Wilson M. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074‐D1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498‐2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu GC, Li F, Qin YD, Bo X, Wu Y, Wang S. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:976‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen L, Zhang YH, Wang SP, Zhang Y, Huang T, Cai YD. Prediction and analysis of essential genes using the enrichments of gene ontology and KEGG pathways. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality‐controlled protein‐protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:362‐368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang Y, Li M, Wang JX, Pan Y, Wu FX. CytoNCA: a cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Biosystems. 2015;127:67‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Y, Bryant SH, Cheng T, et al. PubChem BioAssay: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D955‐D963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buntrock RE. ChemOffice ultra 7.0. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2002;42(6):1505‐1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. wwPDB Consortium . Protein Data Bank: the single global archive for 3D macromolecular structure data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D520‐D528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasanoff ES, Li F, George EM, Dagda RK. A pilot STEM curriculum designed to teach high school students concepts in biochemical engineering and pharmacology. EC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;7:846‐877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455‐461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ito H, Asmussen S, Traber DL, et al. Healing efficacy of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) seed oil in an ovine burn wound model. Burns. 2014;40:511‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim J, Lee CM. Wound healing potential of a polyvinyl alcohol‐blended pectin hydrogel containing Hippophae rahmnoides L. extract in a rat model. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;99:586‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen CC, Nien CJ, Chen LG, Huang KY, Chang WJ, Huang HM. Sapindus mukorossi effects of seed oil on skin wound healing: in vivo and in vitro testing. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20, 4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bilgen F, Ural A, Kurutas EB, Bekerecioglu M. The effect of oxidative stress and Raftlin levels on wound healing. Int Wound J. 2019;16:1178‐1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buranasin P, Mizutani K, Iwasaki K, et al. High glucose‐induced oxidative stress impairs proliferation and migration of human gingival fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi CH. Mechanisms and treatment of blast induced hearing loss. Korean J Audiol. 2012;16:103‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asher BF, Guilford FT. Oxidative stress and low glutathione in common ear, nose, and throat conditions: a systematic review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2016;22:44‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baysal E, Aksoy N, Kara F, et al. Oxidative stress in chronic otitis media. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1203‐1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sagiroglu S, Ates S, Tolun FI, Oztarakci H. Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidants effect on turning process acute otitis media to chronic otitis media with effusion. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22:375‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Daniel TG, Petitjean M, Jones SC, et al. Epidermal growth factor binding and action on tympanic membranes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:80‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee MC, Seonwoo H, Garg P, et al. Chitosan/PEI patch releasing EGF and the EGFR gene for the regeneration of the tympanic membrane after perforation. Biomater Sci. 2018;6:364‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaftan H, Reuther L, Miehe B, Hosemann W, Herzog M. The influence of inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor on tympanic membrane wound healing in rats. Growth Factors. 2010;28:286‐292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cetinkaya EA, Ciftci O, Alan S, Oztanır MN, Basak N. The efficacy of hesperidin for treatment of acute otitis media. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46:172‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cetinkaya EA, Ciftci O, Alan S, Oztanır MN, Basak N. What is the effectiveness of beta‐glucan for treatment of acute otitis media? Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87(6):683‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moon SK, Linthicum FH, Yang HD, Lee SJ, Park K. Activities of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase‐2 in idiopathic hemotympanum and otitis media with effusion. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:144‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jennings CR, Guo L, Collins HM, Birchall JP. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in otitis media with effusion. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001;26:491‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Polerà N, Badolato M, Perri F, Carullo G, Aiello F. Quercetin and its natural sources in wound healing management. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:5825‐5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ahmad M, Sultana M, Raina R, Pankaj NK, Verma PK, Prawez S. Hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and wound healing potential of quercetin in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic rats. Pharmacogn Mag. 2017;13:633‐639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jangde R, Srivastava S, Singh MR, Singh D. In vitro and In vivo characterization of quercetin loaded multiphase hydrogel for wound healing application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;115:1211‐1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Doersch KM, Newell‐Rogers MK. The impact of quercetin on wound healing relates to changes in αV and β1 integrin expression. Exp Biol Med. 2017;242:1424‐1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ezzat SM, Choucry MA, Kandil ZA. Antibacterial, antioxidant, and topical anti‐inflammatory activities of Bergia ammannioides: a wound‐healing plant. Pharm Biol. 2016;54:215‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lin PH, Sermersheim M, Li H, Lee PHU, Steinberg SM, Ma J. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lansdown AB, Mirastschijski U, Stubbs N, Scanlon E, Agren MS. Zinc in wound healing: theoretical, experimental, and clinical aspects. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:2‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilmoth JG, Schultz GS, Antonelli PJ. Tympanic membrane metalloproteinase inflammatory response. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:647‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu M, Fan Y, Gao Z, Chen J, Li J. Hearing loss and trace elements Fe2+ and Zn2+ in the perilymph. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1995;57:245‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from TCMSP, GeneCardS, OMIM, TTD, PharmGkb, and DrugBank belong to public databases.