Abstract

Motivated by a suicide prevention trial with hierarchical treatment allocation (cluster-level and individual-level treatments), we address the sample size requirements for testing the treatment effects as well as their interaction. We assume a linear mixed model, within which two types of treatment effect estimands (controlled effect and marginal effect) are defined. For each null hypothesis corresponding to an estimand, we derive sample size formulas based on large-sample z-approximation, and provide finite-sample modifications based on a t-approximation. We relax the equal cluster size assumption and express the sample size formulas as functions of the mean and coefficient of variation of cluster sizes. We show that the sample size requirement for testing the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment is more sensitive to cluster size variability than that for testing the controlled effect of the individual-level treatment; the same observation holds for testing the marginal effects. In addition, we show that the sample size for testing the interaction effect is proportional to that for testing the controlled or the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment. We conduct extensive simulations to validate the proposed sample size formulas, and find the empirical power agrees well with the predicted power for each test. Furthermore, the t-approximations often provide better control of type I error rate with a small number of clusters. Finally, we illustrate our sample size formulas to design the motivating suicide prevention factorial trial. The proposed methods are implemented in the R package H2x2Factorial.

Keywords: Coefficient of variation, controlled effect, marginal effect, interaction test, linear mixed model, power analysis

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Intervention programs with multiple components or treatments are common in health, behavioral and educational research. Factorial design is a rigorous framework to evaluate the effects of different intervention components or treatments.1 In a traditional 2×2 factorial trial with two treatments, T1 and T2, investigators could simultaneously randomize the two treatments and assign the individual participants to one of the four conditions: T1 only, T2 only, both T1 and T2, and double usual care. The cross-classification of participants into four conditions allows the identification of each single treatment effect as well as the interaction effect of different treatments.2 While traditional factorial designs randomize treatments at the individual level, recent design variants have considered factorial randomization at the cluster level, where a cluster could be a school, clinic or hospital.3 In a cluster randomized factorial trial, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the outcome inflates the required sample size compared to an individually randomized factorial trial, and thus represents a key consideration for study planning.3,4,5,6

While sample size formulas for factorial designs with randomization carried out at the same level (cluster level or individual level) were previously studied2,3 (for example, Lemme et. al7,8 have proposed variance expressions for the treatment effect estimator as well as optimal design results for 2×2 factorial cluster randomized and multi-center individually randomized trials), sample size formulas when randomization is carried out at two different levels are less developed. Our motivating example is a hierarchical 2 × 2 factorial trial, which aims to assess the clinical effectiveness of a two-component intervention program for suicide prevention among community-dwelling transgender individuals. In this trial, participating clinics will be randomized to either the Caring Contacts (CC) arm or the usual care condition.9 In addition, participants within each clinic will be individually randomized to either Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP) arm or usual care.10 Because participants are nested within clinics, the ICC of the outcome should be considered for study planning as in a cluster randomized factorial trial. However, unlike the cluster randomized factorial trial, individual-level randomization of the CBT-SP program necessitates additional design considerations for testing the treatment effects.

In the experimental design literature, the hierarchical 2×2 factorial design has also been referred to as the split-plot design.11,12 A recent systematic review of split-plot trials suggested that rigorous methods for sample size calculation were lacking.12 Shin et al.13 developed a sample size procedure for testing (both separately or jointly) the main effects and their interaction under a split-plot design with an arbitrary number of factor levels. However, their approach assumes moment-based estimators of the regression parameters, and therefore does not exploit the ICC during the analysis stage. Failure to account for the within-cluster correlation in the estimation of parameters can be less statistically efficient and can lead to a larger sample size than necessary. In this article, we consider generalized least square (GLS) estimators for the regression coefficients, and develop corresponding sample size formulas for testing the effects of the two treatments based on our motivating study. A common complication of 2×2 factorial trials is the definition of estimands. Here, we proceed by first clarifying two different sets of estimands to characterize the treatment effect, based on which we derive a set of closed-form sample size formulas for study planning. Specifically, in the context of the 2 × 2 table commonly constructed for factorial trials, we refer to the main effects of treatments as the inside-the-table estimands, whereas we refer to the marginal treatment effects as the at-the-margin estimands.14 We formally define these causal estimands under the framework of potential outcomes15 and discuss their interpretation and implication for sample size estimation. Finally, we also address the interaction effect of the two treatments within our framework.

For sample size considerations, while it is conventional to assume equal cluster sizes in a split-plot design,13 we relax this assumption to mimic more realistic scenarios observed in practice. Unequal cluster sizes arise frequently in pragmatic studies, in which participating providers or clinics naturally have different source population sizes or rates of participation. While the implications of unequal cluster sizes have been studied in cluster randomized trials (CRT),16,17,18,19 its implications for hierarchical factorial designs with two treatments remain unclear. Assuming the cluster sizes are randomly sampled from an underlying distribution, we will derive, for each hypothesis testing procedure, the corresponding closed-form sample size formula that further depends on the mean cluster size as well as the coefficient of variation (CV) of cluster sizes. In particular, we show that the sample size requirement for testing the main effect of the cluster-level treatment tends to be more sensitive to cluster size variation than that for testing the main effect of the individual-level treatment. Interestingly, this observation also holds for the at-the-margin analyses. Furthermore, we show that the sample size for testing the interaction effect is proportional to that for testing the main effect or the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the considered linear mixed model, treatment effect estimands, and derive the large-sample covariance matrix for the GLS estimators assuming unequal cluster sizes. Section 3 presents the closed-form sample size formulas for testing each hypothesis of interest and discuss finite-sample considerations. In Section 4, we conduct extensive simulation studies to evaluate the accuracy of the proposed sample size formulas with equal and unequal cluster sizes. We apply our approach to obtain the sample size for the suicide prevention factorial trial in Section 5, and Section 6 concludes with a discussion.

2 ∣. STATISTICAL MODEL

2.1 ∣. Linear mixed model and estimands for hierarchical 2×2 factorial trials

We consider a hierarchical 2×2 factorial trial with one treatment (T1) randomized at the cluster level and the second (T2) at the individual level. In the context of the suicidal prevention trial, T1 and T2 refer to the CC and CBT-SP programs, respectively. Let Yij be a continuous outcome measured from the jth individual (j = 1, …, mi) in the ith cluster (i = 1, …, n). We assume nπx (0 < πX < 1) clusters are randomized to T1, and n(1 − πX) to usual care. Within each clusters, we further assume miπZ (0 < πZ < 1) participants are randomized to T2, and the remaining mi(1 − πZ) to usual care. We assume a “saturated” linear mixed model to characterize the outcomes according to treatment combinations as

| (1) |

where Xi is the indicator for the cluster-level treatment (Xi = 1 if cluster i is assigned to T1 and Xi = 0 otherwise), Zij is the indicator for the individual-level treatment (Zij = 1 if the jth individual in cluster i is assigned to T2 and Zij = 0 otherwise), XiZij is the interaction between the two treatments, and β4 describes the direction and magnitude of the interaction effect. To account for clustering, we assume is a random intercept describing the unobserved between-cluster variability, and define as the within-cluster random error. We further assume independence between ai and ϵij. Model (1) implies a common ICC, defined by , where is the total variance of Yij.4,20 Of note, the ICC parameter in our model, ρ, and the total variance, , are both conditional on Xi and Zij, as opposed to only conditional on Xi in a traditional parallel CRT or on Zij in a traditional multi-center individually randomized trial.

Model (1) captures the average outcome for four types of patients based on their treatment status. The parameter β1 represents the mean outcome for those assigned to double usual care, β1 + β2 represents the mean outcome for those receiving T1 only, β1 + β3 represents the mean outcome for those receiving T2 only, and β1 + β2 + β3 + β4 represents the mean outcome for those receiving both treatments. These parameters summarize the information in a 2 × 2 table and are commonly used to describe the effects of interest for the inside-the-table analysis. To precisely define the treatment effect estimands in our context, we borrow the potential outcome notation and write Yij(x, z) as the potential outcome of each individual when he/she receives treatment combination Xi = x and Zij = z with x, z ∈ {0, 1}. We further assume the stable unit treatment value assumption, and therefore can connect the observed outcome Yij with the set of potential outcomes depending on the observed treatment status.21 Specifically, we define the controlled effect (CE) of a single treatment in the absence of the other treatment as:

Assuming model (1) and under factorial randomization, we can write

By the above equality, the two controlled effect estimands correspond to the main-effects parameters in model (1), and are conceptually similar to the usual estimands in a non-factorial randomized controlled trial with one treatment and one control. The controlled effects are of interest when investigators wish to study the pure effect of each treatment in a target population without being affected by the other treatment. We can further define the total effect (TE) of two treatment as TEX Z = E[Yij(1, 1) − Yij (0, 0)], which leads to the interaction effect (IE) estimand:

Alternatively, the at-the-margin analysis focuses on the marginal effect (ME) of one treatment when the other treatment is rolled out according to the pre-specified randomization plan. Resuming the potential outcome notation, the marginal effects can be defined as

Under factorial randomization, we obtain

which become weighted averages of certain controlled effect estimands. The marginal effect of each treatment in the trial population describes the effectiveness of each treatment when the other treatment is randomized according to schedule. In other words, the marginal effect addresses the question of whether one treatment affects the outcome on average in the trial where individuals naturally maintain their status of the other treatment. Both the controlled effect and marginal effect are valid causal estimands in the sense of Neyman22 and Rubin23,24, as they are defined as a comparison between potential outcomes on a common set of units. The interaction effect, IEX Z, however, should be interpreted as a function of causal estimands. Depending on the direction and maginitude of the interaction effect, the marginal effect may be stronger or weaker than the controlled effect for each treatment. Finally, in the absence of interaction such that β4 = 0, the controlled effect is identical to the marginal effect for each treatment.

2.2 ∣. Large-sample covariance matrix

To study the sample size requirements for the hierarchical 2×2 factorial trial, we first provide a closed-form characterization of the large-sample variance matrix of the regression parameter estimators, which are ingredients for assembling different sample size formulas corresponding to the treatment effect estimands defined in Section 2.1. While we follow the general strategy considered in Jung and Ahn25 and Yang et al.26 to derive the 4×4 variance matrix, a major difference in our work is that we allow for unequal cluster sizes. Specifically, we reparameterize model (1) by mean-centering the cluster-level treatment

| (2) |

where b1 = β1 + β2πX, b2 = β2, b3 = β3 + β4πX, and b4 = β4. Define the design vector Dij = (1, (Xi − πX), Zij, (Xi − πX)Zij)T and Di = (Di1, …, Dimi)T, then the Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) estimator for b = (b1, b2, b3, b4)T is given as , where Ri = (1 − ρ)Imi + ρJmi is the compound symmetric correlation matrix of the outcome, Imi is the mi × mi identity matrix, and Jmi is the mi × mi matrix of ones. Assuming the cluster sizes come from a well-defined distribution f(mi) with finite first and second moments, as the number of clusters n becomes large, the root-n scaled FGLS estimator, , converges to a multivariate normal distribution with mean zero and covariance matrix . In what follows, we provide an explicit form of the 4×4 matrix Σ to develop analytical sample size formulas based on the linear mixed model in equation (1).

For each cluster i, the inverse of the compound symmetric correlation matrix can be obtained as27

where ci = −ρ/[1 + (mi − 1)ρ]. Therefore, we can represent

| (3) |

Due to randomization, the cluster size distribution f(mi) is independent of both treatment indicators. Define as the mean cluster size, is the Bernoulli variance of cluster-level treatment, we show in Web Appendix A that

This allows us to obtain

We further define the following expectations for the functions of cluster sizes as

for r = 1, 2 and write as the Bernoulli variance of individual-level treatment. In Web Appendix A, we further show

These intermediate results allow us to obtain

Therefore, based on (3), the large-sample variance can be obtained by block matrix inversion as

where the component matrices can be derived explicitly as

3 ∣. SAMPLE SIZE ESTIMATION

As exemplified in Table 1, we develop sample size formulas based on several null hypotheses regarding the two controlled effects CEX and CEZ, the two marginal effects MEX and MEZ, as well as the interaction effect IEX Z in the hierarchical factorial trial.

TABLE 1.

Example types of null hypotheses for the motivating hierarchical 2 × 2 factorial trial. CC stands for the Caring Contact program, randomized at the clinic level, and CBT-SP stands for the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention program, randomized at the participant level. CEX denotes the controlled (or main) effect of the CC program, CEZ denotes the controlled effect of the CBT-SP program, MEX denotes the marginal effect of the CC program, MEZ denotes the marginal effect of the CBT-SP program, and IEX Z denotes the interaction effect of the CC and CBT-SP programs.

| Label | Null hypothesis | Scientific interpretation of null |

|---|---|---|

| (A1) | The net effect of the CC program in the absence of the CBT-SP program is zero. | |

| (A2) | The net effect of the CBT-SP program in the absence of the CC program is zero. | |

| (B1) | There is no effect due to the CC program compared with usual care among the trial population when clinics are randomized to CBT-SP according to trial. | |

| (B2) | There is no effect due to the CBT-SP program compared with usual care among all clinics when individuals are randomized to CC according to trial. | |

| (C) | There is no synergistic or antagonistic effect between the CC and CBT-SP interventions. |

3.1 ∣. Separate tests for the controlled effects

We first consider separately testing the null hypotheses concerning the two controlled effects introduced in section 2.1. The null hypotheses of interest are given by (A1) and (A2) . Define δ2 and δ3 as the effect sizes for the controlled effects of cluster-level and individual-level treatments, respectively. For testing , the total required number of clusters based on a two-sided Wald z-test is given by

where α and λ define the prescribed type I and type II error rates, and . Likewise, for testing , the total required number of clusters with a nominal test size α and power 1 − λ is given by

where . Therefore, sample size estimation for testing the controlled effect of each single treatment requires the explicit expressions of the scaled variance parameters, ω2 and ω3.

Based on model (2) and the corresponding variance derivation in Section 2.2, we can write that

While the expression of ω3 depends on the cluster size distribution only through , the expression of ω2 depends on both and . Following van Breukelen et al.19 and Candel et al.28, we use the second-order Taylor expansion and show in Web Appendix B that

Furthermore, we obtain

In the equations above, we use CV to refer to the coefficient of variation of cluster sizes. These key identities lead us to the approximate expressions of ω2 and ω3, and hence, the approximate sample size formulas for testing the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment and the individual-level treatment.

Starting from the simpler one, by plugging in the approximate expression of ω3, we can obtain the required number of clusters for testing as

| (4) |

This sample size formula implies that larger cluster size variability may reduce the required sample size for testing because nA2 is a decreasing function of the CV of cluster sizes mathematically. However, a closer examination of (4) also reveals that realistic degrees of cluster size variation (often with CV not exceeding 0.6) have a limited impact on the resulting sample size unless the mean cluster sizes happens to be small (since the factor ρ2(1 − ρ) is close to zero for common ICC values4,29).

Next, we obtain the sample size formula for testing the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment. The required number of clusters for testing is given by

| (5) |

where

Although the actual formula of nA1 appears cumbersome, it could be more conveniently decomposed as an addition of two components as indicated above, and we comment on each of them. For the component , we firstly find that it has the same form as the sample size formula derived in van Breukelen et al.19 in a parallel CRT with unequal cluster sizes. Further, under equal cluster sizes such that for all i, becomes the usual sample size formula in a two-arm parallel CRT, with variance inflation factor (VIF) due to clustering equal to 1 + (m − 1)ρ.4 For the second component, takes a similar form as nA2, and we further observe . Based on the results of van Breukelen et al.,19 it is clear that is more sensitive to cluster size variability compared to . Intuitively, the contribution of in our sample size for studying the controlled effect in a hierarchical factorial trial can be considered as the “additional cost” due to an additional individual-level treatment, as compared to a traditional two-arm CRT.

Furthermore, it will also be of interest to study the controlled effect of one treatment in the presence of the other treatment. In Web Appendix C, we provide definitions and derivations of the sample size formulas for testing the controlled effect of each treatment when the other treatment is present. For testing the controlled individual-level treatment effect in the presence of cluster-level treatment (X = 1), one can obtain the sample size formula by multiplying (4) with (1 − πX)/πX and replacing δ3 with δ3 + δ4 (δ4 defined as the interaction effect size in Section 3.3). For testing the controlled cluster-level treatment effect in the presence of the individual-level treatment (Z = 1), the required sample size shares the same form with (5), except that δ2 is replaced with δ2 + δ4 and the second component of is multiplied by .

3.2 ∣. Separate tests for the marginal effects

We next derive sample size formulas regarding the at-the-margin analyses, for testing the marginal effect of each treatment. The null hypotheses of interest are given by (B1) and (B2) . Define δX and δZ as the effect sizes for the marginal effects of the cluster-level treatment and the individual-level treatment, respectively. Similar to the strategies practiced in Section 3.1, for testing , the required number of clusters based on a two-sided Wald z-test with a nominal test size α and power 1 − λ is given by

where . Meanwhile, for testing , the corresponding framework of sample size formula is given by

where . Similarly, explicit expressions of ωX and ωZ should be obtained to derive the sample size formulas for the two marginal treatment effect tests.

Again, from the reparameterized model (2) as well as the large-sample variance derivations, we have

Utilizing the approximation identities in Section 3.1, the sample size formula for testing is given by

| (6) |

Because , the implications discussed for also apply directly to the sample size requirement for testing the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment. To reiterate, the VIF for nB1 due to unequal cluster sizes takes the same form as the VIF for a parallel CRT derived by van Breukelen et al.19. Second, under equal cluster sizes, the sample size formula for the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment has the same form of that in a parallel CRT. This is a major difference from the corresponding sample size requirement for the controlled effect in Section 3.1. When the CV of cluster sizes increases, the required number of clusters to detect the cluster-level marginal effect also increases as a nonlinear function. In addition, the VIF due to unequal cluster sizes has a parabolic relationship in ρ, and reaches its maximum when .19

For testing the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment, the corresponding large-sample variance is given by

By appealing to the identities approximated in Section 3.1, we arrive at the required number of clusters for testing as

| (7) |

Similar to the implications from formula (4) and , sample size formula (7) suggests that, under common values of ICC and cluster sizes, CV has only a negligible impact on the required sample size for testing the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment. Furthermore, when the cluster sizes are all equal ( for all i), sample size formula (7) reduces to

Interestingly, this equation suggests that the design effect for testing due to clustering equals to (1 − ρ){1 + (m − 1)ρ}/{1 + (m − 2)ρ}, which is strictly smaller than one. In other words, a positive within-cluster correlation actually improves the power for testing the individual-level marginal effect compared with the case of no correlation. Of note, in a multi-center individually randomized trial with the same value of ICC, one can show that the required number of clusters assuming a linear mixed model adjusting for Zij only is given by

which is smaller than nB2. However, if m becomes larger, then {1 + (m − 1)ρ}/{1 + (m − 2)ρ} ≈ 1 and .

3.3 ∣. Interaction test

One potential advantage of model (1) is that it introduces a formal test for potential interaction between the two treatments. Specifically, the null hypothesis of no interaction is given as (C) . The required number of clusters for testing based on a two-sided Wald z-test is given by

where δ4 is the target interaction effect size, and the corresponding variance result in Section 2.2 suggest

Based on the Taylor series approximation in Section 3.1, we obtain the sample size formula

| (8) |

Importantly, the required sample size only depends on the interaction effect size δ4 regardless of the magnitude of the main effect parameters in model (1). Furthermore, the required sample sizes for the interaction test and the tests of the two individual-level effect measures satisfy

which implies that the sample size relationship for these three tests depends on the ratio among the three effect sizes and only the allocation weight of the cluster-level treatment πX. This also suggests that the sample size for the interaction test may be larger or smaller than the required sample size for testing the individual-level controlled effect or marginal effect. And similar to the sample size requirements for testing the two estimands of the individual-level treatment effect, nC is also not sensitive to realistic degrees of cluster size variability. Finally, when the cluster sizes are all equal, we obtain

which is a special case of the formula derived in Yang et al.26 for testing the interaction between a cluster-level treatment and an individual-level binary covariate when the covariate exhibits no clustering.

3.4 ∣. Finite-sample considerations

Due to financial and human resource constraints, a frequent limitation of research designs using clusters (such as health centers or clinics) is that only a small number of clusters are available, even though the clusters may have moderate to large sizes. For example, recent systematic reviews of published CRTs found that more than half of the studies reviewed included 24 or fewer clusters.30,31 With a limited number of clusters available, the Wald z-test may carry an inflated type I error rate when studying both the controlled and marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, and a t-test coupled with the between-within degrees of freedom (df = n − 2) has been suggested to preserve the nominal test size.32 This finite-sample consideration necessitates modifications to the sample size procedures concerning the test for either types of cluster-level treatment effect. On the other hand, because the total sample size is usually much larger than the number of clusters, the Wald-tests for both the controlled and marginal effects of the individual-level treatment as well as the interaction effect has sufficient within-cluster degrees of freedom such that the z-approximation of the null distribution is expected to be adequate.

For testing the controlled or marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, we still proceed with the corresponding test statistics, and , both of which now approximately follow the t-distribution under the null. Under the alternative, W2 and WX follow the noncentral t-distribution with noncentrality parameter θX, which equals to or , respectively. Therefore, the corresponding power formula is given by

| (9) |

where t1−α/2,n−2 and tα/2,n−2 are the upper- and lower- α/2 quantile of the central t-distribution with n − 2 degrees of freedom, and Ψn−2(•; θ) is the cumulative distribution function of the noncentral t-distribution with n − 2 degrees of freedom and noncentrality parameter θ. Although equation (9) should in principal be solved iteratively, a non-iterative approximation could be made by computing the required sample size nA1 or nB1 through (5) or (6) and then multiplying by (n + 1)/(n − 1).33 The use of the t-approximation, as we shall see in Section 4, can help maintain the correct type I error rate with a limited number of clusters and therefore improve the validity for designing hierarchical factorial trials.

3.5 ∣. Joint tests and intersection-union tests with two treatments

While our focus is on the separate tests of the controlled effects and the marginal effects, our design methodology can extend to accommodate a joint test and an intersection-union (I-U) test when the interest lies in studying two treatments simultaneously. Specifically, whereas the joint test rejects the null when at least one treatment has an effect on the outcome, investigators may also conclude the “success” of a trial only when both treatments are effective. The I-U test is often used to address this kind of composite null hypothesis, and has been previously applied in trials with multiple co-primary endpoints; see, for example, Chuang et al.,34 Sozu et al.35 and Li et al.36

We extend our sample size methodology for the joint tests and I-U tests based on the controlled effect and marginal effect estimands. For these two types of tests, we present power formulas and use iterative procedures to obtain the sample size under the proposed power formulas. To derive power equations for these two tests, the n-scaled covariance between either the two controlled effect estimators or the two marginal effect estimators shall be derived, and the details are provided in Web Appendix D and E. Interestingly, we show that for the marginal effects, the two effect estimators are asymptotically orthogonal, or equivalently, , which allows for substantial simplification in the technical derivations. Finally, since both the joint test and the I-U test involve the cluster-level treatment effect estimator, we also consider finite-sample corrections for these two types of tests in Web Appendix D and E, parallel to the discussions in Section 3.4.

4 ∣. A SIMULATION STUDY

4.1 ∣. Simulation design

We carried out a simulation study to assess the performance of the proposed sample size formulas in a hierarchical 2×2 factorial trial with equal randomization (πX = πZ = 1/2). Based on the sample size equations we derived in Section 3, the number of clusters is determined by the following parameters: nominal type I error rate (α), power (1 − λ), total variance , ICC (ρ), mean cluster size , CV of cluster sizes, and the effect sizes specified in different hypotheses (δ2, δ3, δX, δZ, or δ4). Throughout, we fixed the total variance at 1, nominal type I error α at 0.05 and the desired power level 1 − λ at 0.8, and varied the remaining parameters. We considered three levels of mean cluster sizes , and three levels of ICC ρ ∈ {0.02, 0.05, 0.1}, based on the range commonly reported in the cluster randomized design literature.4,29 The CV of cluster sizes were chosen from CV ∈ {0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9} with CV = 0 representing equal cluster sizes. Our experiences suggest that most CRTs have CV no larger than 0.6, and therefore the scenario with CV = 0.9 corresponds to an extreme case for illustration. To ensure a realistic range of predicted sample sizes, we separately specified effect sizes for each type of hypothesis. We chose δ2 ∈ {0.2, 0.4} for testing , δ3 ∈ {0.15, 0.3} for testing , δX ∈ {0.2, 0.4} for testing , δZ ∈ {0.1, 0.15} for testing , and δ4 ∈ {0.2, 0.3} for testing . In summary, we considered 3×3×4×2 = 72 parameter combinations for each of the null hypotheses. For each parameter combination, we estimated the number of clusters n that gives at least 80% power and rounded to the nearest even integer above to ensure an exactly equal randomization. We used the predicted cluster number n to simulate correlated outcomes and obtain the empirical power to validate the accuracy of the formula-based power prediction.

We generated correlated outcome data based on model (1). We fixed β1 = 1 for simplicity. As described in Section 3, while the controlled effect sizes δ2, δ3 and the interaction effect size δ4 correspond to β2, β3 and β4, the marginal effect sizes δX and δZ are linear combinations of regression parameters and only correspond to certain constraints for β2, β3 and β4. Specifically, under the scenarios of and , we have β4 = 2(δX − β2) and β4 = 2(δZ − β3). Table 2 summarized the specification of regression parameters in each simulation scenario to match the assumed controlled or marginal effect sizes. Finally, given values of and CV, we simulate varying cluster sizes using mi ~ Gamma(g, h), where the shape parameter g = CV−2 and the rate parameter . Sensitivity of our results to alternative cluster size distributions is assessed by repeating our simulations under normal and uniform cluster size distributions. The detailed data generation processes and simulation results for those sensitivity analyses were presented in Web Appendix H. The results suggest that the power is primarily driven by mean and CV of cluster sizes, instead of higher-order moments, and therefore we focus on the Gamma distribution here. The simulated cluster size mi was rounded to the nearest integer and ensured to be at least 2 for computational stability. Finally, the cluster-specific random intercept ai was randomly generated from , and the random error ϵij was independently generated from . For each parameter combination, we generated 5,000 hypothetical factorial trials for the evaluation of empirical type I error under the null and power under the alternative.

TABLE 2.

Specification of regression parameters for generating correlated outcome data in different simulation scenarios. (A1) represents the test for the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment, (A2) represents the test for the controlled effect of the individual-level treatment, (B1) represents the test for the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, (B2) represents the test for the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment, (C) represents the interaction test. β2, β3, and β4 stands for the true regression parameters corresponding to the main effect of the cluster-level treatment, the main effect of the individual-level treatment, and the interaction effect, respectively.

| Test label | Hypothesis | β 2 | β 3 | β 4 | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A1) | Null () | 0 | 0.05 | 0.05 | CEX = 0 |

| Alternative () | δ 2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | CEX = δ2 | |

| (A2) | Null () | 0.15 | 0 | 0.05 | CEZ = 0 |

| Alternative () | 0.15 | δ 3 | 0.05 | CEZ = δ3 | |

| (B1) | Null () | 0.15 | 0.05 | −0.3 | MEX = 0 |

| Alternative () | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2(δX − 0.15) | MEX = δX | |

| (B2) | Null () | 0.15 | 0.05 | −0.1 | MEZ = 0 |

| Alternative () | 0.15 | 0.05 | 2(δZ − 0.05) | MEZ = δZ | |

| (C) | Null () | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0 | IEX Z = 0 |

| Alternative () | 0.15 | 0.05 | δ 4 | IEX Z = δ4 |

For each simulated hypothetical factorial trial, we fitted the linear mixed model (1) using the restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML) and carried out the corresponding Wald test for inference. Under the null, the empirical type I error rate was computed as the proportion of false rejections among the 5,000 trials. Under the alternative, the empirical power was calculated as the proportion of correct rejections among the 5,000 trials, and was compared with the power prediction based on our proposed formulas. We also conducted simulations to verify the proposed power formulas for the joint tests and I-U tests of the two treatments, with details provided in Web Appendix G. Finally, for the tests involving either the controlled effect or the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, i.e., those associated with and (, , , and in Web Appendix G), we replicated the simulations based on the modified sample size methods discussed in Section 3.4, using the same parameter configurations, to assess the potential improvement of type I error rate due to finite-sample adjustment. Our simulations were carried out in R (version 4.0.3) and all linear mixed models were fitted using the nlme package.37

4.2 ∣. Simulation results

Web Table 1 and Table 3 present the estimated required number of clusters (nA1), empirical type I error (ψ), empirical power (ϕ) and predicted power corresponding to testing the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment based on two levels of effect sizes. The t-test with the between-within degrees of freedom can require more clusters to achieve a similar level of power compared to the z-test. However, compared to the z-test, the t-test has more robust control of the empirical type I error rate, especially with a larger effect size δ2 and a smaller number of clusters. On the other hand, the empirical power of both the z-test and t-test agree well with the prediction even if the CV of cluster sizes is as extreme as 0.9, which confirms the accuracy of the proposed formulas. In addition, we also observe that the required sample size can be sensitive to the CV of cluster sizes when the effect size is relatively small (Web Table 1).

TABLE 3.

Required number of clusters nA1, empirical type I error ψ, empirical power ϕ, and predicted power corresponding to the test for the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment with and without finite-sample correction. The controlled effect size of the cluster-level treatment is δ2 = 0.4. Notation: is the mean cluster size, ρ is the ICC, CV is the coefficient of variation of cluster sizes. The results were based on 5,000 simulations.

| CV |

z-test |

t-test |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n A1 | ψ | ϕ | n A1 | ψ | ϕ | |||||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 24 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 24 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 28 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.9 | 26 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 30 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.83 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 30 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 32 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 34 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.9 | 34 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 36 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 38 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 40 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | |

| 0.3 | 40 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 42 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.6 | 40 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 42 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.9 | 44 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 46 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 12 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.80 | |

| 0.3 | 12 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.86 | ||

| 0.6 | 14 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 16 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.84 | ||

| 0.9 | 14 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 18 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 20 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 18 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 20 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 20 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 22 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.9 | 20 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 24 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.84 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 28 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 30 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 28 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 30 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 28 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.9 | 30 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 8 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 12 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.88 | |

| 0.3 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 12 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.87 | ||

| 0.6 | 10 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 12 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.86 | ||

| 0.9 | 10 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 12 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.83 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 14 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.6 | 16 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 18 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.84 | ||

| 0.9 | 16 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 18 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 24 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 24 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 24 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.9 | 26 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.82 | ||

Web Table 3 and Table 4 present the estimated required number of clusters (nB1), empirical type I error (ψ), empirical power (ϕ) and predicted power corresponding to testing the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment. With the same effect size and controlling for other design parameters, we confirm that nB1 is strictly smaller than nA1. Similar to results for the controlled effect tests, the t-test for the marginal effect has more robust control of the empirical type I error rate than the z-test, especially when effect size δX is large and nB1 is small. For example, with as few as 6 clusters, the z-test carries a type I error rate as large as 11% and necessitates finite-sample adjustment. The empirical power for both the z-test and t-test match well with the analytical results even under extreme CV cases, which suggests the proposed formulas are accurate. As expected from our prior discussions, the required sample size nB1 can also be sensitive to the CV of cluster sizes when the effect size is relatively small (Web Table 2). Overall, the findings for testing either the controlled effect or the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment in our hierarchical factorial trial are consistent with the previous findings in parallel CRTs.19

TABLE 4.

Required number of clusters nB1, empirical type I error ψ, empirical power ϕ, and predicted power corresponding to the test for the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment with and without finite-sample correction. The marginal effect size of the cluster-level treatment is δX = 0.4. Notation: is the mean cluster size, ρ is the ICC, CV is the coefficient of variation of cluster sizes. The results were based on 5,000 simulations.

| CV |

z-test |

t-test |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n B1 | ψ | ϕ | n B1 | ψ | ϕ | |||||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 14 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.6 | 16 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 18 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.9 | 18 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 20 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.84 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 20 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 22 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 20 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 22 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 22 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 24 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.9 | 24 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 28 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.83 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 30 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 32 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 34 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.9 | 36 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 38 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.82 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 8 | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 12 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.88 | |

| 0.3 | 8 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 12 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.87 | ||

| 0.6 | 10 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 12 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.85 | ||

| 0.9 | 10 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.87 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.6 | 16 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 18 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.9 | 18 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 20 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.84 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 24 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 24 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 26 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.9 | 26 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.80 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 6 | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.89 | |

| 0.3 | 6 | 0.10 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.89 | ||

| 0.6 | 8 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.87 | ||

| 0.9 | 8 | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 10 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.83 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 12 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | |

| 0.3 | 12 | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 16 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.86 | ||

| 0.6 | 14 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 16 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.84 | ||

| 0.9 | 14 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 16 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.82 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 22 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 24 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 22 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 24 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 22 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.9 | 24 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.82 | ||

When testing the controlled effect or the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment (Web Table 2 and 4) as well as the interaction effect (Table 5), the z-test provides close to nominal test size and dispenses the need for any finite-sample corrections. In our simulation design, we set , and therefore the estimated sample size nC and nB2 are identical in Table 5 and Web Table 4. Confirming our analytical discussion in Section 3.1 and 3.2, the estimated sample size is not sensitive to the CV of cluster sizes as the ICC in clustered designs is usually small.4,29 In general, the empirical power of the z-test for , and is close to the formula prediction, and confirms the accuracy of our sample size formulas. However, the empirical power of the interaction test appears to be slightly lower than the prediction when the effect size δ4 = 0.3, the mean cluster size , and the CV of cluster sizes becomes 0.9. In this case, the estimated number of clusters is often smaller than 15 and the large-sample approximation under unequal cluster sizes may be less accurate. With a larger cluster size, the empirical power of the z-test for testing the individual-level treatment effect and the interaction effect matches the formula prediction even when the CV of cluster sizes is equal to 0.9.

TABLE 5.

Required number of clusters nC, empirical type I error ψ, empirical power ϕ, and predicted power corresponding to the interaction test. Notation: δ4 is the interaction effect size, is the mean cluster size, ρ is the ICC, CV is the coefficient of variation of cluster sizes. The results were based on 5,000 simulations.

| CV |

δ4 = 0.2 |

δ4 = 0.3 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nC | ψ | ϕ | nC | ψ | ϕ | |||||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 158 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 70 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | |

| 0.3 | 158 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 70 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.6 | 156 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 70 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.9 | 156 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 70 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 154 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 70 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 154 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 68 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||

| 0.6 | 154 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 68 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0.9 | 154 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 68 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | |

| 0.9 | 154 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 68 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 148 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 66 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 148 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 66 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 146 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 66 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.9 | 146 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 66 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 64 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 64 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 64 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.9 | 64 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 62 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 62 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.6 | 62 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.9 | 62 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 58 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 58 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 58 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.9 | 58 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 26 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.02 | 0 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | |

| 0.3 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.6 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.9 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.81 | ||

| ρ = 0.05 | 0 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | |

| 0.3 | 32 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.6 | 32 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.82 | ||

| 0.9 | 32 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.82 | ||

| ρ = 0.10 | 0 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.84 | |

| 0.3 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.84 | ||

| 0.6 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.84 | ||

| 0.9 | 30 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 14 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.84 | ||

5 ∣. APPLICATION TO THE SUICIDE PREVENTION FACTORIAL TRIAL

We illustrate the proposed sample size formulas in the context of the motivating suicide prevention trial. The suicide prevention trial considers a hierarchical 2×2 factorial design, and aims to study the clinical effectiveness of two treatment strategies, CC delivered at the cluster level and CBT-SP delivered at the individual level, for suicide prevention among community-dwelling transgender individuals. Clinics will be randomized in a 1:1 ratio to usual care or to deliver CC, an efficacious suicide prevention approach that involves sending participants brief, non-demanding expressions of care and concern at specified time intervals.9 Participants within a clinic be randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive the CBT-SP program or usual care. CBT-SP consists of acute and continuation phases, each lasting about 12 individual sessions, and includes a chain analysis of the suicidal event, safety plan development, skill building, psychoeducation, family intervention, and relapse (recurrence of suicidal behavior) prevention.10 Since the depression is an outcome along the causal pathway to suicide attempt or suicide death,38 we consider it as an intermediate outcome to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of our two interventions. The level of depression will be measured using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a 9 item scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 27. We treat the score as a continuous outcome with larger values indicating ascending symptoms of depression.38

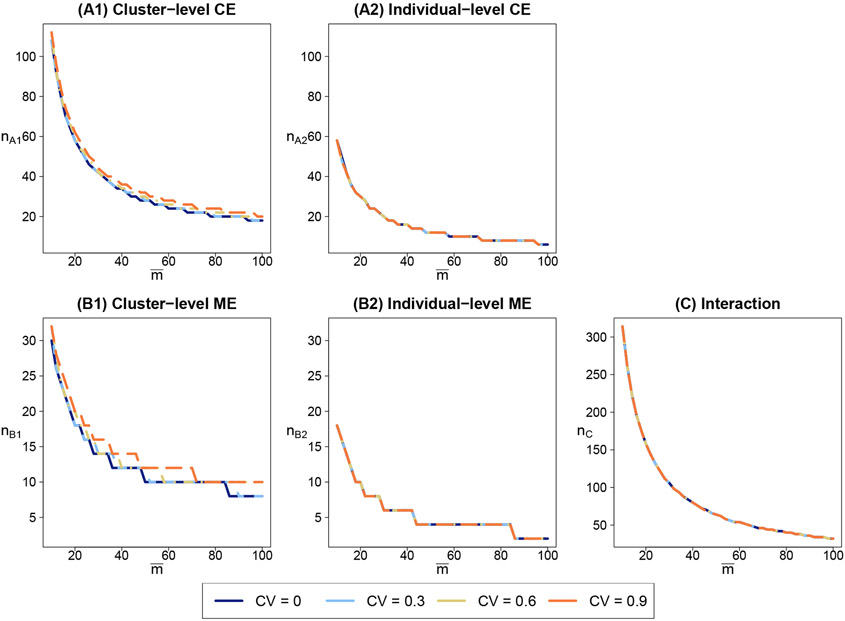

Figure 1 presents the sample size requirements for five different tests that can be relevant for planning the trial (also see Table 1 for interpretations of these hypotheses). Each panel plots the combinations of mean cluster size and the number of clusters for a two-sided test with 0.05 significance level to achieve 80% power, given a fixed set of CV of cluster sizes. We interpret each test separately and therefore do not further consider corrections for multiple testing. Because the t-approximation could substantially improve the empirical type I error rate, our calculation considers the t-based finite-sample corrections, whenever applicable. We hypothesize that the standardized effect size for the controlled effect of the CC program is δ2/σy = 0.25, and that for the controlled effect of the CBT-SP program is δ3/σy = 0.33. We also assume the standardized effect size of the interaction effect to be δ4/σy = 0.2. Therefore, the marginal effect of each program can be calculated, as δX/σy = 0.35 for the CC program and δZ/σy = 0.43 for the CBT-SP program. The ICC characterizing the within-cluster similarity is assumed to be 0.01, and the allocation ratio πX = πZ = 1/2 under equal randomization. Because each clinic on average is likely to recruit no more than 100 participants, we vary the mean cluster size from 10 to 100 for each test to examine the trend of required number of clusters.

FIGURE 1.

Required number of clusters n and mean cluster sizes to achieve 80% power across four levels of cluster size variability for five types of hypothesis tests for the marginal effect of Caring Contacts (CC) program and the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP) program in the motivating trial. (A1) stands for the test for the controlled effect of the CC program, (A2) stands for the test for the controlled effect of the CBT-SP program, (B1) stands for the test for the marginal effect of the CC program, (B2) stands for the test for the marginal effect of the CBT-SP program, (C) stands for the interaction test.

Panel (A1) in Figure 1 presents the sample size requirement for testing the controlled effect of the CC program across four levels of cluster size variations measured by CV. Under equal cluster sizes (CV = 0), as the mean cluster size increases, the required number of clusters decreases from 112 to 18. At the same level of mean cluster size, a larger CV will slightly inflate nA1. This observation is consistent with the findings in our simulation study and the prior results studied for a two-arm parallel CRT.19 Similar patterns can also be found in panel (B1) for testing the marginal effect of the CC program. Specifically, under equal cluster sizes and a synergistic interaction, the required number of clusters decreases from 30 to 8 as the mean cluster size increases from 10 to 100. The marginal effect size of CC is larger than the controlled effect size, a factor that contributes to a smaller sample size for testing the marginal effect of CC. Similarly, a larger CV tends to slightly inflate nB1 especially with larger mean cluster sizes.

In contrast, Panel (A2), (B2) and (C) indicate that the CV of cluster sizes has negligible influence on the sample sizes for testing the controlled effect of the CBT-SP program, the marginal effect of the CBT-SP program, or the interaction effect. This is expected because ρ2(1 − ρ) = 9.9 × 10−5 ≈ 0, and therefore the term involving CV in equation (4), (7) and (8) is negligible. In addition, we observe that, under a similar level of effect size, the interaction test can require a substantially larger number of clusters compared to the tests for either controlled or marginal effect associated with the CC program or the CBT-SP program. For example, to ensure an 80% power, the required number of clusters decreases from 58 to 6 for the controlled effect test of the CBT-SP program as the mean cluster size increases from 10 to 100, while the required number of clusters decreases from 18 to 2 for the marginal effect test of that individual-level program (partially because the effect size for the latter is larger with a synergistic interaction). However, for the interaction test, the required number of clusters decreases from 314 to 32.

6 ∣. DISCUSSION

In this article, we developed a set of sample size and power formulas in a hierarchical 2 × 2 factorial trial with a cluster-level treatment and an individual-level treatment. Based on a continuous outcome, we considered two types of treatment effect estimands, the controlled (or main) and marginal effects, as well as the interaction effect estimand. The controlled effects of treatments were referred to the inside-the-table estimands, while the marginal effects of treatments were referred to the at-the-margin estimands, and these two estimands were formally defined and compared under the potential outcome framework. The null hypotheses we considered include (A1) the test for the controlled effect of the cluster-level treatment, (A2) the test for the controlled effect of the individual-level treatment, (B1) the test for the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, (B2) the test for the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment, (C) the test for the interaction effect. Extensions to simultaneously studying the two controlled effects or the two marginal effects were provided in Web Appendix D and E. Our simulations indicate that the proposed sample size formulas can accurately track the empirical power of each test under a wide range of parameter configurations. We applied our formulas to study the sample size requirements for each test in the motivating suicide prevention factorial trial, and illustrated different possibilities on the number of clusters and average cluster sizes to achieve the desired level of power under a fixed set of design parameters.

While sample size formulas for planning research designs with clusters often assume an equal cluster size, our development relaxed this condition and provided approximations under unequal cluster sizes. Importantly, even in the presence of an individual-level treatment, the VIF for testing the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment due to unequal cluster sizes has the same form as the VIF developed for a two-arm parallel CRT.19 Therefore, the design implications from CRTs can be extrapolated to the cluster-level marginal treatment effect test in our hierarchical 2×2 factorial designs. For example, van Breukelen19 pointed out that the loss of efficiency (or the inflation of sample size) rarely exceeds 10% for CRTs analyzed by linear mixed models, which should apply to the at-the-margin analysis of cluster-level treatment based on our linear mixed model (1) with two treatments. In contrast, unequal cluster sizes have negligible effect on the sample size requirement for testing the either the controlled or the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment. This is mainly because the factor involving CV is multiplied by the average cluster size and ρ2(1 − ρ), the latter of which is usually fairly small in research designs with clusters. Furthermore, because the sample size formula for the interaction test is proportional to that for either individual-level treatment effect test, it is similarly insensitive to unequal cluster sizes.

Because research designs with clusters may not enlist a large number of clusters, and the z-test for either the controlled or the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment may carry an inflated type I error rate in small samples, our sample size development also considers a t-approximation with the between-within degrees of freedom32 as a finite-sample consideration. In contrast, because the individual treatment variable changes within each cluster and exploits within-cluster comparisons for estimation, the tests for the controlled effect and the marginal effect of the individual-level treatment as well as the interaction effect between two treatments have sufficient within-cluster degrees of freedom, which ensures the accuracy of the z-test even when the number of clusters is limited. These considerations were also included in developing the sample size formulas for the joint test and the I-U test for each type of the two effect estimands. Our simulations demonstrated that the t-approximation not only improves the test size (compared to the z-approximation) for both the tests for the controlled effect and the tests for the marginal effect of the cluster-level treatment, but also for the joint tests and the I-U tests for each effect measure, suggesting its necessity in developing a valid sample size procedure. Such finite-sample considerations were also included in determining the required sample size for the motivating suicide prevention trial.

For completeness, we have provided two sets of target estimands to describe the treatment effects in a hierarchical factorial trial, namely the controlled effect and marginal effect of each treatment. The former measures the net effect of one treatment in the absence of the other treatment and corresponds to the estimand considered in a conventional, non-factorial randomized trial with one treatment and one control, whereas the latter measures the effectiveness of one treatment in the factorial trial by assuming the other treatment is already rolled out per design. In other words, the marginal effects can be specific to the factorial trial, whereas the controlled effects may have a more straightforward interpretation due to their resemblance to conventional estimands. In the absence of interaction, the marginal effect size and the controlled effect size are identical for each treatment, but they have different values when the two treatments have either a synergistic or an antagonistic effect. Because the non-null interaction effect leads to either a larger or smaller marginal effect compared to the controlled effect for a given treatment, there have been debates on whether the marginal effect estimand is appropriate for factorial trials.2,14,39,40 Nevertheless, as we pointed out in Section 2.1, the marginal effect estimand has a valid causal interpretation and its potential may not be dismissed altogether. We do not argue that one type of estimand is always more favorable than the other, and recognize that the choice of estimands can depend on the specific context and scientific question. On the other hand, our work helps articulate their comparisons from a sample size perspective. In the absence of interaction, the two types of estimands share the same effect size such that CEX = δ2 = δX = MEX and CEZ = δ3 = δZ = MEZ. For studying the cluster-level treatment effect, because and nA1 > nB1, testing the controlled effect requires a larger sample size than testing the marginal effect. The same pattern holds for the individual-level treatment effect because . Furthermore, the above comparison patterns also hold when the two treatments have a synergistic effect, since the effect sizes of marginal effects are larger than those of the controlled effects. Finally, in the presence of an antagonistic interaction, the sample size comparisons between the controlled effect and marginal effect analyses can depend on the magnitude of interaction. These insights suggest that although the controlled effect may have a straightforward interpretation, the corresponding analysis based on model (1) may require a larger sample size than the marginal effect analysis.

While we focused on sample size formulas for distinct null hypotheses in the hierarchical 2 × 2 factorial trial, a possible strategy to analyze this type of trial is to first test whether there is an interaction between the two treatments. If the interaction is significant, then the interest lies in assessing the effect of each treatment for each level of the other treatment. If the interaction is not significant, then the main effects of treatments are tested. In this case, a conservative approach for study design is to identify the largest sample size needed for any of these possibly relevant statistical tests. Thus, our development may still be helpful for constructing this conservative approach. However, a critical aspect of this hierarchical testing procedure is that the subsequent null hypotheses concerning the separate treatment effects depend on the first-stage interaction test, which can require additional considerations on controlling for the overall type I error rate of the entire procedure. A more exact sample size formula appropriate for the hierarchical testing procedure in factorial designs is beyond the scope of this article and remains an important topic for future research.

There are several limitations that we plan to address in our future work. First, we have only considered a hierarchical 2 × 2 factorial design as in our motivating example, while other factorial clustered designs can have more than two arms at each level. For example, Shin et al.13 developed a sample size procedure for the split-plot design with K factors (treatment arms), but they have not considered testing the marginal effect for each factor (they have only considered testing the controlled effects and their interaction effect) and only assumed an equal cluster size. It would be interesting to extend our work to accommodate an arbitrary level of treatments at each level, while allowing for unequal cluster sizes. Second, while we considered several test statistics for different null hypotheses, we interpreted each test separately and have not addressed multiple testing when more than one test is used for the primary analysis. Nevertheless, our formulas can be easily combined with Bonferroni correction as a conservative approach to control for family-wise error rate. Third, we have not considered random cluster-by-treatment interactions to allow for treatment effect heterogeneity. In the presence of such heterogeneity, the corresponding ICC will depend on the treatment status, which will lead to a different large-sample covariance matrix of the regression coefficient estimators. A full derivation under this more complex model is beyond the scope of this article and will be left for future research. Finally, our development assumes a linear mixed model with a continuous outcome, and we plan to carry out future work to extend our methods to hierarchical factorial trials with a binary outcome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR001863 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the Associate Editor and two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive suggestions that led to improvements of the paper.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Web Tables 1-4 referenced in the article can be found at the online supplementary materials available at Wiley Library Online. R code for reproducing the simulation results and the figure in Section 5 is available at the author’s GitHub page https://github.com/BillyTian/code_Hierarchical2x2Factorial. The proposed sample size formulas are also implemented in an open-source R package H2x2Factorial that is available on the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Collins LM, Dziak JJ, Kugler KC, Trail JB. Factorial experiments: Efficient tools for evaluation of intervention components. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2014; 47(4): 498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery AA, Peters TJ, Little P. Design, analysis and presentation of factorial randomised controlled trials. Medical Research Methodology 2003; 3(1): 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dziak JJ, Nahum-Shani I, Collins LM. Multilevel factorial experiments for developing behavioral interventions: Power, sample size, and resource considerations. Psychological Methods 2012; 17(2): 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; . 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials in Health Research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; . 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mdege ND, Brabyn S, Hewitt C, Richardson R, Torgerson DJ. The 2× 2 cluster randomized controlled factorial trial design is mainly used for efficiency and to explore intervention interactions: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014; 67(10): 1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemme F, Breukelen vGJ, Berger MP. Efficient treatment allocation in 2× 2 cluster randomized trials, when costs and variances are heterogeneous. Statistics in Medicine 2016; 35(24): 4320–4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemme F, Breukelen vGJ, Candel MJ. Efficient treatment allocation in 2× 2 multicenter trials when costs and variances are heterogeneous. Statistics in Medicine 2018; 37(1): 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landes SJ, Kirchner JE, Areno JP, et al. Adapting and implementing Caring Contacts in a Department of Veterans Affairs emergency department: A pilot study protocol. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2019; 5(1): 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009; 48(10): 1005–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montgomery DC. Design and Analysis of Experiments. John Wiley & Sons; . 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulão B, MacLennan G, Ramsay C. The split-plot design was useful for evaluating complex, multilevel interventions, but there is need for improvement in its design and report. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 96: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin Y, Lafata JE, Cao Y. Statistical power in two-level hierarchical linear models with arbitrary number of factor levels. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 2018; 194: 106–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAlister FA, Straus SE, Sackett DL, Altman DG. Analysis and reporting of factorial trials: a systematic review. JAMA 2003; 289(19): 2545–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin DB. Causal inference using potential outcomes: Design, modeling, decisions. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2005; 100(469): 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerry SM, Martin Bland J. Unequal cluster sizes for trials in English and Welsh general practice: implications for sample size calculations. Statistics in Medicine 2001; 20(3): 377–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manatunga AK, Hudgens MG, Chen S. Sample size estimation in cluster randomized studies with varying cluster size. Biometrical Journal 2001; 43(1): 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: Effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. International Journal of Epidemiology 2006; 35(5): 1292–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Breukelen GJ, Candel MJ, Berger MP. Relative efficiency of unequal versus equal cluster sizes in cluster randomized and multicentre trials. Statistics in Medicine 2007; 26(13): 2589–2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner EL, Prague M, Gallis JA, Li F, Murray DM. Review of recent methodological developments in group-randomized trials: Part 2—analysis. American Journal of Public Health 2017; 107(7): 1078–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press; . 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neyman JS. On the application of probability theory to agricultural experiments. essay on principles. section 9.(tlanslated and edited by dm dabrowska and tp speed, statistical science (1990), 5, 465-480). Annals of Agricultural Sciences 1923; 10: 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies.. Journal of Educational Psychology 1974; 66(5): 688. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Bayesian inference for causal effects: The role of randomization. The Annals of Statistics 1978: 34–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung SH, Ahn CW. Sample size for a two-group comparison of repeated binary measurements using GEE. Statistics in Medicine 2005; 24(17): 2583–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S, Li F, Starks MA, Hernandez AF, Mentz RJ, Choudhury KR. Sample size requirements for detecting treatment effect heterogeneity in cluster randomized trials. Statistics in Medicine 2020; 39(28): 4218–4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li F, Turner EL, Preisser JS. Sample size determination for GEE analyses of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Biometrics 2018; 74(4): 1450–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candel MJ, van Breukelen GJ. Sample size adjustments for varying cluster sizes in cluster randomized trials with binary outcomes analyzed with second-order PQL mixed logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine 2010; 29(14): 1488–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray DM, Blitstein JL. Methods to reduce the impact of intraclass correlation in group-randomized trials. Evaluation Review 2003; 27(1): 79–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiero MH, Huang S, Oren E, Bell ML. Statistical analysis and handling of missing data in cluster randomized trials: a systematic review. Trials 2016; 17(1): 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivers N, Taljaard M, Dixon S, et al. Impact of CONSORT extension for cluster randomised trials on quality of reporting and study methodology: Review of random sample of 300 trials, 2000-8. British Medical Journal 2011; 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P, Redden DT. Comparing denominator degrees of freedom approximations for the generalized linear mixed model in analyzing binary outcome in small sample cluster-randomized trials. Medical Research Methodology 2015; 15(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steel dRG, Torrie JH. Principles and Procedures of Statistics: A Biometrical Approach. McGraw-Hill. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuang-Stein C, Stryszak P, Dmitrienko A, Offen W. Challenge of multiple co-primary endpoints: a new approach. Statistics in Medicine 2007; 26(6): 1181–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sozu T, Sugimoto T, Hamasaki T. Sample size determination in clinical trials with multiple co-primary binary endpoints. Statistics in Medicine 2010; 29(21): 2169–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li D, Cao J, Zhang S. Power analysis for cluster randomized trials with multiple binary co-primary endpoints. Biometrics 2020; 76(4): 1064–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer Science & Business Media; . 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death?. Psychiatric Services 2013; 64(12): 1195–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lubsen J, Pocock SJ. Factorial trials in cardiology: pros and cons. European Heart Journal 1994; 15: 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahan BC, Tsui M, Jairath V, et al. Reporting of randomized factorial trials was frequently inadequate. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2020; 117: 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.