Abstract

Introduction

The Wnt proteins play key roles in the development, homeostasis and disease progression of many organs including the prostate. However, the spatiotemporal expression patterns of Wnt proteins in prostate cell lineages at different developmental stages and in prostate cancer remain inadequately characterized.

Methods

We isolated the epithelial and stromal cells in the developing and mature mouse prostate by flow cytometry and determined the expression levels of Wnt lignads. We used Visium spatial gene expression analysis to determine spatial distribution of Wnt ligands in the mouse prostatic glands. Using laser-capture microscopy in combination with gene expression analysis, we also determined the expression patterns of Wnt signaling components in stromal and cancer cells in advanced human prostate cancer specimens. To investigate how the stroma-derived Wnt ligands affect prostate development and homeostasis, we used a Col1a2-CreERT2 mouse model to disrupt the Wnt transporter Wntless (Wls) specifically in prostate stromal cells.

Results

We showed that the prostate stromal cells are a major source of several Wnt ligands. Visium spatial gene expression analysis revealed a distinct spatial distribution of Wnt ligands in the prostatic glands. We also showed that Wnt signaling components are highly expressed in the stromal compartment of primary and advanced human prostate cancer. Blocking stromal Wnt secretion attenuated prostate epithelial proliferation and regeneration but did not affect cell survival and lineage maintenance.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a critical role for stroma derived Wnt ligands in prostate development and homeostasis.

Keywords: Wnt, Wls, prostate stromal cells, homeostasis, prostate cancer

Introduction

The prostate is a male sexual accessory gland developed from the embryonic urogenital sinus (UGS) (1). The mouse prostate consists of four pairs of lobes: the anterior (AP), ventral (VP), dorsal (DP) and lateral (LP) prostate lobes (2). The mouse prostate gland contains the Keratin 8-expressing luminal cells, Keratin 5-expressing basal cells and rare neuroendocrine cells (3, 4), and is surrounded by a thin layer of stromal cells. Although the prostate epithelial cells turn over slowly under normal physiological conditions, they possess extensive regenerative potential. The prostate luminal epithelial cells undergo apoptosis upon androgen deprivation but can quickly proliferate and regenerate after androgen replacement. Many signal transduction pathways have been shown to regulate prostate development and homeostasis, including the Wnt signaling pathway (5).

The Wnt proteins are a family of acylated and glycosylated secretory proteins with a pivotal role in embryonic morphogenesis, tissue development, and homeostasis (6, 7). Wntless (Wls) is a transmembrane protein that is essential for the intracellular trafficking and secretion of mammalian Wnts (8). Wnt signaling has been classified into the β-catenin-dependent canonical pathway and β-catenin-independent non-canonical pathway. Both pathways have been shown to play critical roles in prostate development. For example, Wnt3a and Wnt10b, two canonical Wnt ligands, stimulate and suppress prostate branching in the in vitro organ culture assays, respectively (9, 10); β-catenin in the prostate epithelia is necessary for prostatic budding and epithelial proliferation during early development, but is dispensable in adult mice (11, 12); the noncanonical Wnt ligand Wnt5a is highly expressed in the mesenchyme of UGS prior to prostatic bud formation and suppresses prostate budding (13, 14).

There are 19 Wnt ligands in mammals and they are widely expressed in the mouse prostate (15, 16). Mehta et al. performed a comprehensive in-situ hybridization analysis and profiled the expression patterns of Wnt ligands in mouse prostate at the early developmental stages (17). Previously, we showed that adult mouse prostate stromal cells expressed higher levels of many Wnt ligands compared to the epithelial cells (18). However, despite extensive prior work, the spatiotemporal expression patterns of the 19 Wnt ligands in the prostate tissues at different developmental stages remain inadequately characterized. In addition, it is unclear whether the Wnt ligands produced by the stromal cells play an indispensable role in prostate development and homeostasis. In this study, we examine the expression profiles of all 19 Wnt ligands in different cell lineages in pelvic urogenital sinus and adult mouse prostate. In addition, we also specifically disrupt Wls in the prostate stromal cells at different developmental stages to determine the role of stromal cell derived Wnt ligands in prostate development and homeostasis.

Dysregulation of Wnt signaling also occurs in various types of cancer, including the prostate carcinoma (19). A multi-institutional genomic sequencing analysis of castration resistant prostate cancer revealed mutations involving Wnt signaling components in 18% of the cases (20). Increasing canonical Wnt signaling induced the formation of high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (11, 16, 21, 22). Non-canonical Wnt signaling has also been suggested to promote resistance to the anti-androgen therapies (23). A previous study indicated that Wnt16b produced by the cells in the tumor microenvironment promoted the resistance of chemotherapy (24), but it remains largely unclear whether Wnt signaling in the tumor cells is activated via an autocrine or paracrine manner or both. In this study, we utilize laser-capture microscopy in combination with gene expression analysis to gain insights into this question.

Results

Stromal cells are a major source of Wnt ligands in the mouse prostate.

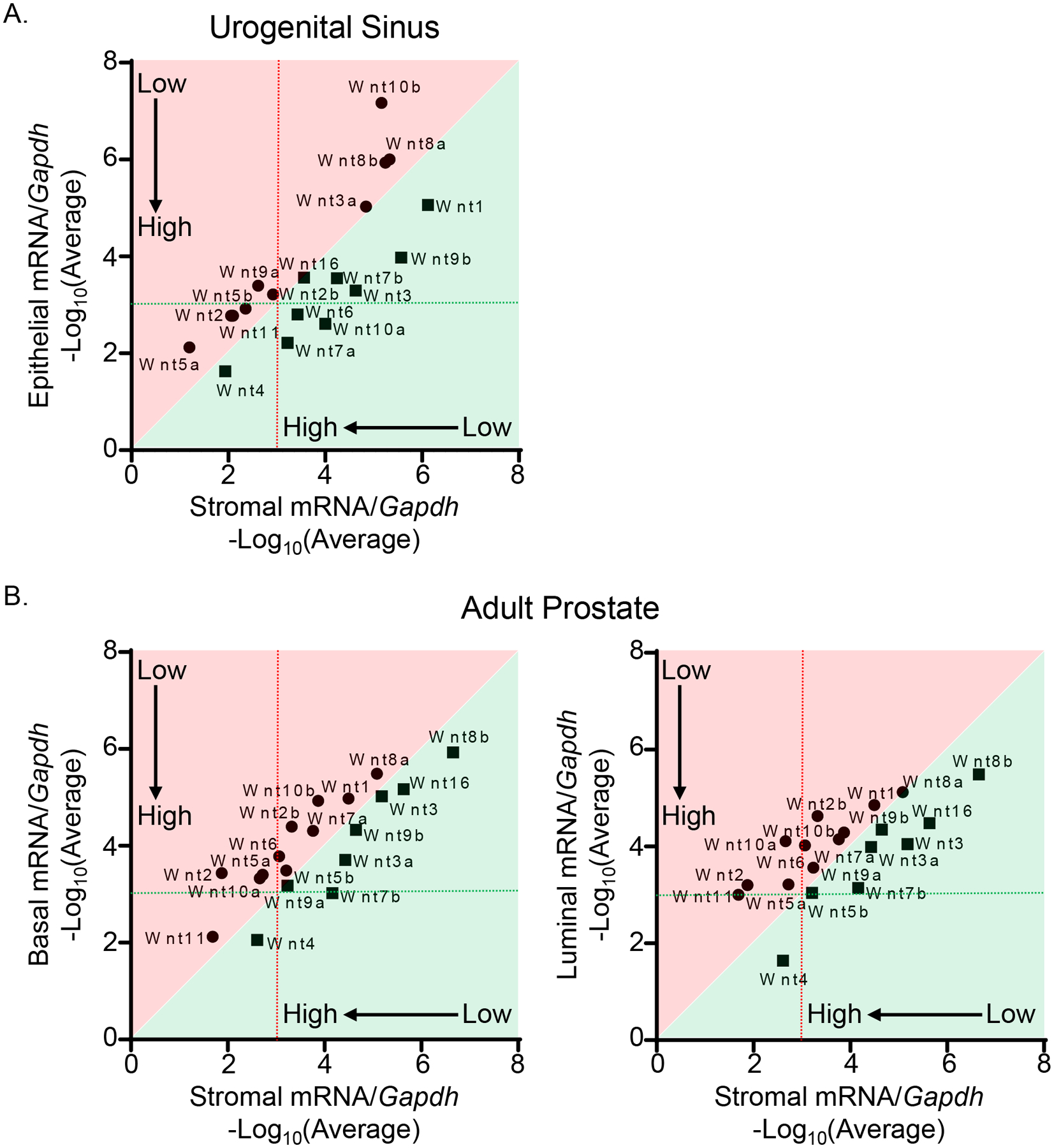

The prostate develops from the pelvic urogenital sinus (UGS). We FACS-isolated the Lin−Trop2+EpCAM+ epithelial and Lin−Trop2−EpCAM− mesenchymal cells from E17 pelvic UGS tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1A) and determined the expression profiles of Wnt ligands in the two cellular compartments by qRT-PCR. Ten out of nineteen Wnt ligands were expressed at a higher level in the UGS mesenchyme compared to epithelia (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1B). Some Wnts were expressed at a relatively higher level (> 0.1% of that of Gapdh), among which Wnt5a, Wnt2, Wnt11, Wnt5b, Wnt9a, and Wnt2b were highly expressed in the mesenchyme whereas Wnt4, Wnt7a, Wnt10a and Wnt6 were highly expressed in the epithelia.

Figure 1.

Spatiotemporal analysis of Wnt ligand expression during prostate development and homeostasis. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of 19 Wnt ligands in FACS-isolated epithelial and mesenchymal cells from E17 pelvic UGS tissues of C57BL/6 mice. Dot graphs represent means from three independent experiments. Genes shown in areas shaded in red and green are expressed at a relatively higher level in stromal cells and epithelial cells, respectively. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of 19 Wnt ligands in FACS-isolated basal, luminal, and stromal cells from adult prostates of C57BL/6 mice. Dot graphs represent means from four independent experiments. Genes shown in areas shaded in red and green are expressed at a relatively higher level in stromal cells and basal/luminal cells, respectively.

We also examined the expression profiles of Wnt ligands in different prostate cell lineages in adult mice, including the Lin−CD49f−Sca1+ stromal cells, Lin−CD49fHiSca1+ basal cells, and Lin−CD49fLowSca1− luminal cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Eleven Wnt ligands were expressed at a higher level in the stromal cells than in the basal cells or luminal cells (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1C). Wnt4 was still the most highly expressed Wnt ligand in the prostate epithelia whereas Wnt11, Wnt2, Wnt5a and Wnt10a were highly expressed in the stromal cells. Collectively, these results show that the stromal cells are a major source of the Wnt ligands during prostate development and homeostasis.

Wnt ligands show distinct spatial expression patterns in mouse prostate.

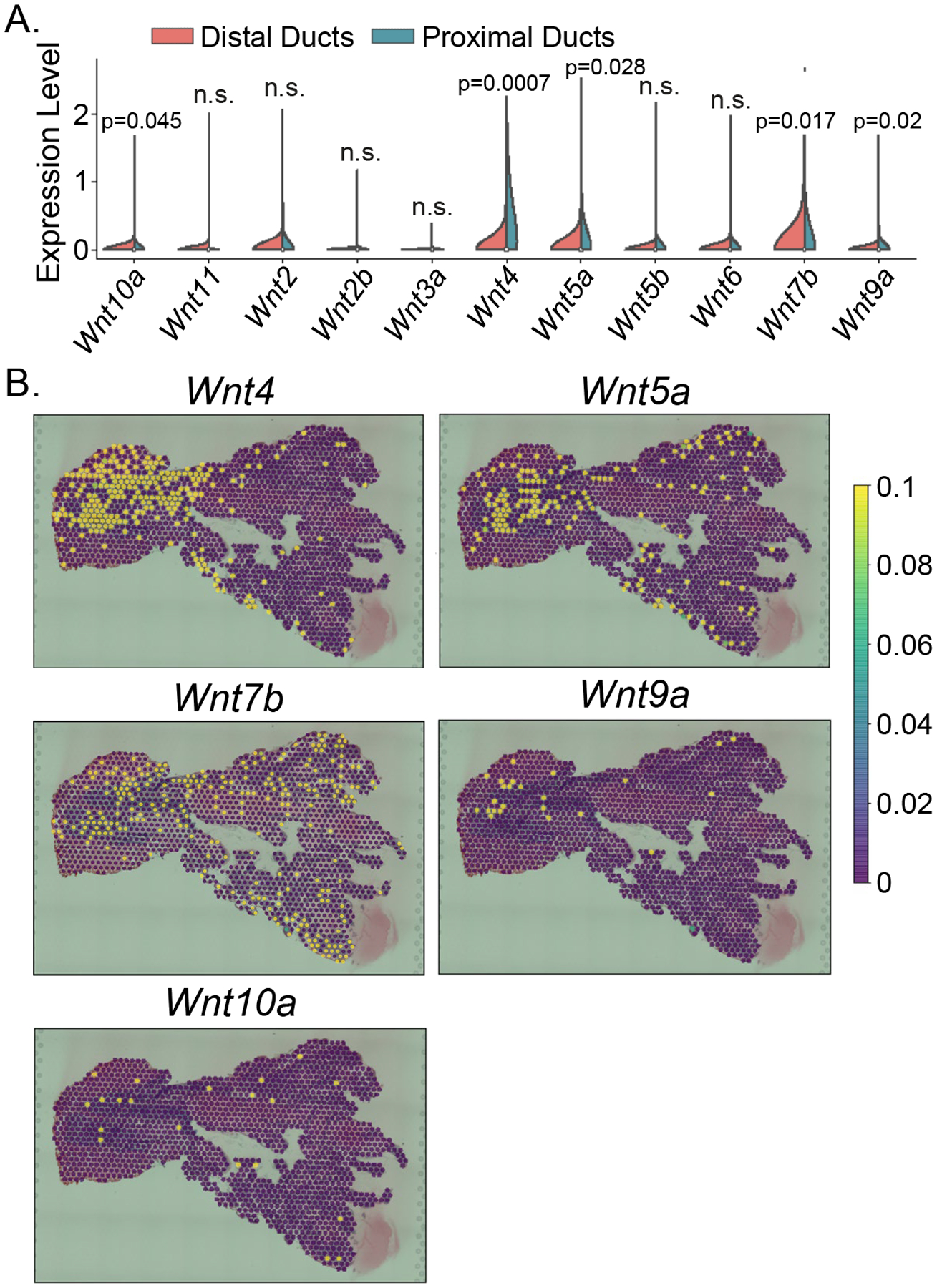

Patterns of gene expression in the prostate have been shown to associate with anatomical and histological structure (18, 25–27). We and others demonstrated that several Wnt ligands were expressed at a higher level in the periurethral prostatic ducts (i.e., proximal ducts) than other ductal locations (distal ducts) (18, 28). To gain a topographic view of the expression patterns of Wnt ligands, we performed a Visium spatial gene expression assay which captures the gene expression in the architecture of intact tissues through an on-slide cDNA synthesis approach. As shown in Fig. 2A, different Wnt ligands exhibited distinct expression levels and distribution patterns in the prostate of 10-week-old adult C57BL/6 mice. Among the ligands expressed at a relatively high level, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt7b, Wnt9a and Wnt10a showed significantly higher expression levels in the proximal ducts (Fig. 2B). The statistical analysis was performed based on four independent experiments. The representative images for other Wnt ligands without significant difference are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. These results show that the Wnt ligands have distinct spatial distribution patterns in the adult mouse prostate.

Figure 2.

Visium spatial gene expression analysis of Wnt ligands in adult mouse prostate. (A) Violin graph shows the average expression levels of 11 Wnt ligands in the distal and proximal ducts of anterior prostatic lobes from 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice. Other Wnt ligands were undetected in the Visium spatial gene expression assay and not shown in the violin graph. Statistical analysis was performed based on four independent experiments. (B) Representative images of spatial gene expression levels in the anterior prostatic lobe and urethra for Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt7b, Wnt9a and Wnt10a.

Ablating Wls in prostate stromal cells decreases epithelial proliferation during early prostate development.

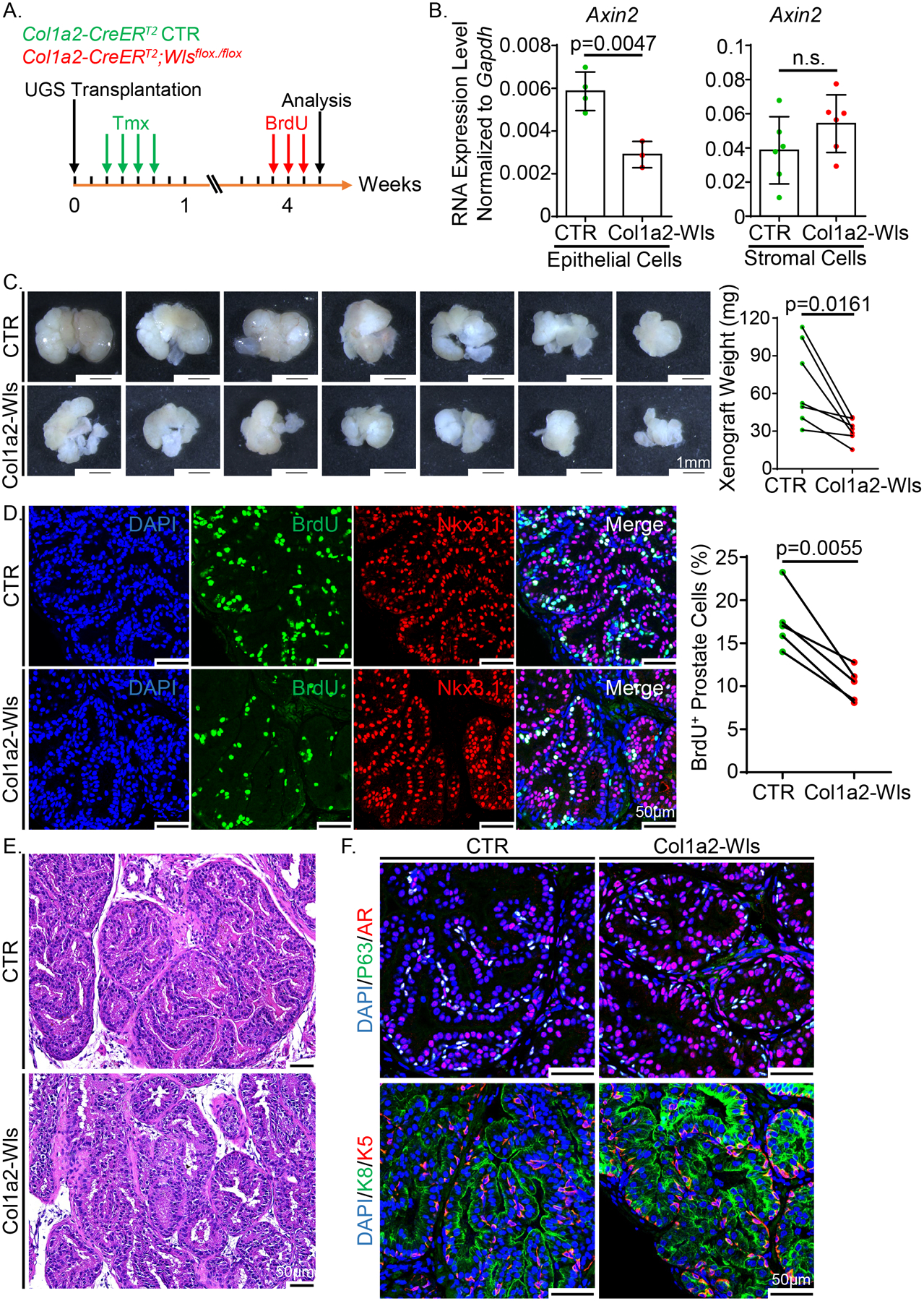

Wntless (Wls) is an evolutionarily conserved transmembrane protein that is indispensable for the secretion of Wnt ligands. To investigate the contribution of stromal cell-derived Wnt ligands to prostate development, we specifically disrupted Wls in the prostate stromal cells using the Col1a2-CreERT2;Wlsflox/flox (Col1a2-Wls) mouse model. To rescue the lethality caused by Wls knockout at early development, we transplanted E16 UGS of the Col1a2-Wls and control Col1a2-CreERT2 mice under the renal capsules of immunodeficient male mice and treated the hosts with tamoxifen one day after implantation to specifically disrupt Wls in the mesenchymal cells of the transplanted UGS tissues (Fig. 3A). The transplanted UGS tissues were collected after a 4-week incubation.

Figure 3.

Ablating Wls in prostate stromal cells decreases epithelial proliferation during early prostate development. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. A pair of UGS tissues from Col1a2-Wls and control groups were transplanted into the capsules of two kidneys in each SCID/Beige male host, respectively. Tmx: tamoxifen. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Axin2 in FACS-isolated epithelial and stromal cells from the xenografts of Col1a2-Wls and control groups. Data represent means ± SD from four and six independent experiments for the analysis of epithelial and stromal cells, respectively. (C) Transillumination images of the xenografts after tamoxifen treatment. Scale bars, 1 mm. Dot graph shows the weight of seven pairs of xenografts analyzed by paired t test. (D) Co-immunostaining of BrdU and Nkx3.1 in the xenografts of Col1a2-Wls and control groups. Scale bars, 50 μm. Dot graph shows the percentage of BrdU+ cells in Nkx3.1+ prostate cells from five pairs of xenografts analyzed by paired t test. (E) H&E staining of the xenografts of Col1a2-Wls and control groups. Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) Co-immunostaining of Trp63/AR and Krt5/Krt8 in the xenografts of Col1a2-Wls and control groups. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To examine whether Wls was specifically and efficiently disrupted in the stromal cells of the outgrown tissues, we FACS-isolated Lin−EpCAM−CD49f−Sca-1+ stromal cells and Lin−EpCAM+ epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A). PCR analysis confirmed that Wls knockout only occurred in the stromal cells (Supplementary Fig. 3B). In addition, qPCR analysis using the mesenchymal genomic DNA showed that the Wls knockout efficiency was approximately 86% (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Finally, qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the expression of Wls in the stromal cells was almost completed ablated whereas the expression was unaffected in the epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 3D). To verify the impact of Wls deletion on Wnt signaling, we examined the expression of Axin2, a downstream target of canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Axin2 was decreased by 51% in the epithelial cells (Fig. 3B), indicating that blocking Wnt secretion from prostate stromal cells decreased canonical Wnt signaling in the epithelial cells. Interestingly, although stromal cells also express Axin2, its transcript level was not affected by loss of Wls.

Fig. 3C shows that the xenografts in the Col1a2-Wls group were smaller than those in the Col1a2-CreERT2 control group. Co-immunostaining of BrdU with the prostate epithelial cell marker Nkx3.1 revealed a significant decrease in prostate epithelial proliferation in the Col1a2-Wls group (Fig. 3D). In contrast, cellular apoptosis was not affected as determined by immunostaining for cleaved caspase 3 (Supplementary Fig. 3E). In addition, we did not notice any differences in the histology (Fig. 3E) or the expression pattern of prostate cell lineage markers including Krt5, Krt8, Trp63 and androgen receptor (AR) (Fig. 3F). In conclusion, these results demonstrate that the stromal cell derived Wnt ligands contribute to the prostate epithelial cell proliferation during prostate development but are not essential for the specification and maintenance of prostate epithelial cell lineages.

Stroma-derived Wnts are necessary for the sustained growth of prostates in adult mice.

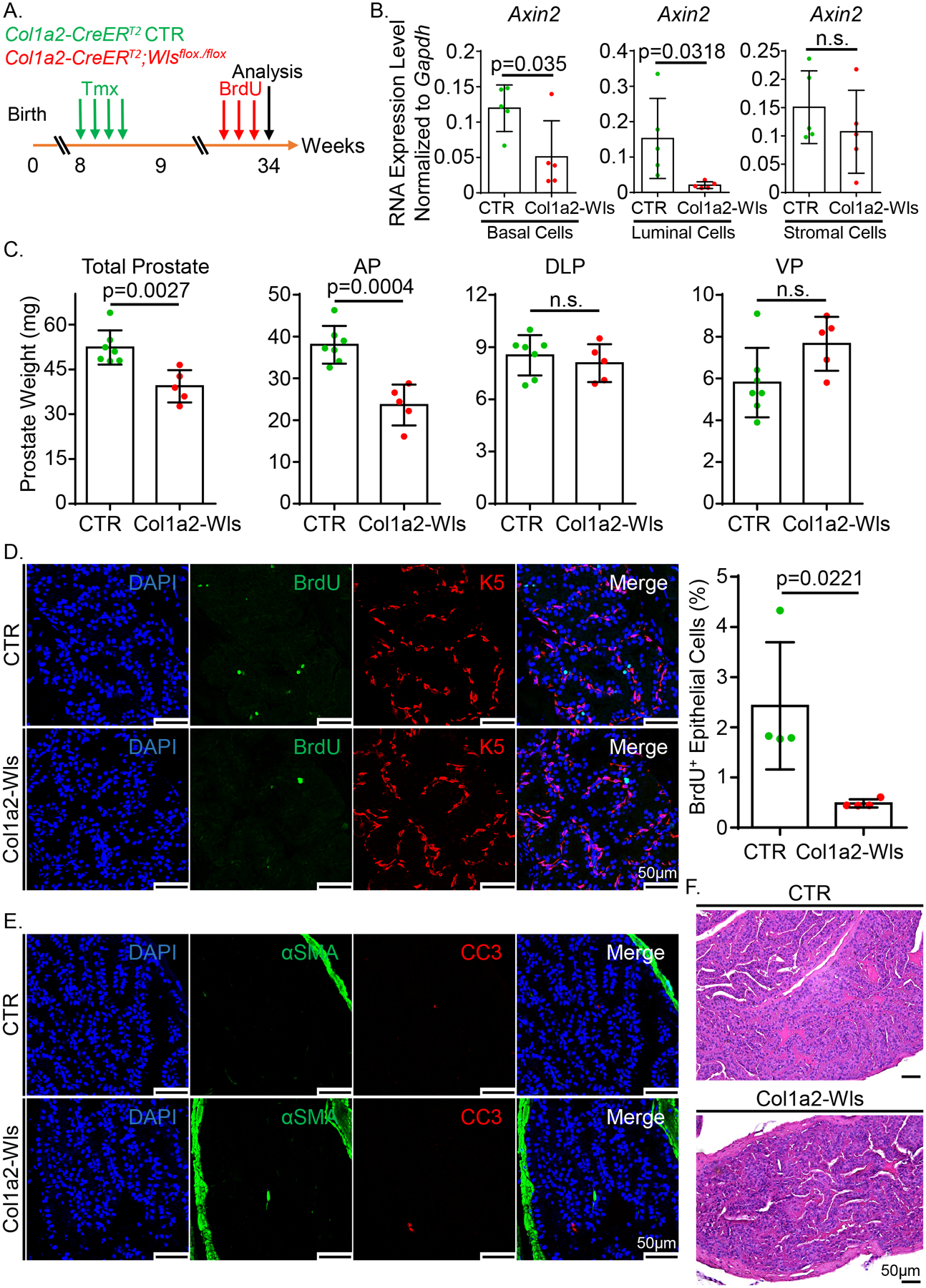

β-catenin is a key player of canonical Wnt signaling, yet the activity of epithelial β-catenin is dispensable for the maintenance of prostate epithelium in adult mice (11). Since Wls deletion affects both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling, we further investigated whether eliminating all stromal cell derived Wnt ligands affected prostate homeostasis in adult mice. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 4A, 8-week-old Col1a2-Wls male mice were treated with tamoxifen to disrupt Wls in prostate stromal cells. Prostate tissues were collected 6 months later to determine the impact on prostate homeostasis.

Figure 4.

Blockage of Wnt ligands secretion from prostate stromal cells impairs the prostate epithelial homeostasis in adult mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. Tmx: tamoxifen. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Axin2 in FACS-isolated prostate basal, luminal and stromal cells from the tamoxifen-treated Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Dot graphs show means ± SD from five independent experiments. (C) Dot graphs show the quantification of prostate weight of five Col1a2-Wls and seven control mice. (D) Co-immunostaining of BrdU and Krt5 in anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. Dot graph shows means ± SD of the percentage of BrdU+ cells in prostate epithelial cells from four pairs of mice. (E) Co-immunostaining of αSMA and CC3 in anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) H&E staining of anterior prostate lobes of the tamoxifen-treated Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Using an eYFP reporter line, we demonstrated that the Col1a2-CreERT2 model can specifically and efficiently target 61–67% of prostate stromal cells in different prostate lobes of adult mice (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We FACS-isolated Lin−CD49fHiSca1+ basal cells, Lin−CD49fLowSca1− luminal cells, and Lin−CD49f−Sca1+ stromal cells and verified that Wls was specifically and efficiently disrupted in prostate stromal cells at both the genomic DNA and RNA levels using the assays described above (Supplementary Fig. 4B–E). Axin2 was downregulated by 57% and 86% in the basal and luminal epithelial cells, respectively (Fig. 4B) although its expression in stromal cells was unaltered. Collectively, these results corroborate that stromal Wls was efficiently disrupted, which attenuated epithelial Wnt signaling. Fig. 4C shows that ablating stromal Wls caused a 25% reduction in prostate weights, mostly due to the decreased weight in the anterior prostates. This is due to a decreased epithelial proliferating index determined by BrdU staining (Fig. 4D). The epithelial apoptotic index was not affected (Fig. 4E). Prostate histology (Fig. 4F) and lineage marker expression were also not affected (Supplementary Fig. 4F). No change in the proliferation, apoptosis, lineage marker expression, or histology in the other three prostate lobes was noted (data not shown). The lobe-specific response is unlikely due to Wls being differentially disrupted in different lobes because Supplementary Fig. 4E shows that the expression of Wls was substantially reduced in the FACS-isolated prostate stromal cells from the tamoxifen-treated Col1a2-Wls mice.

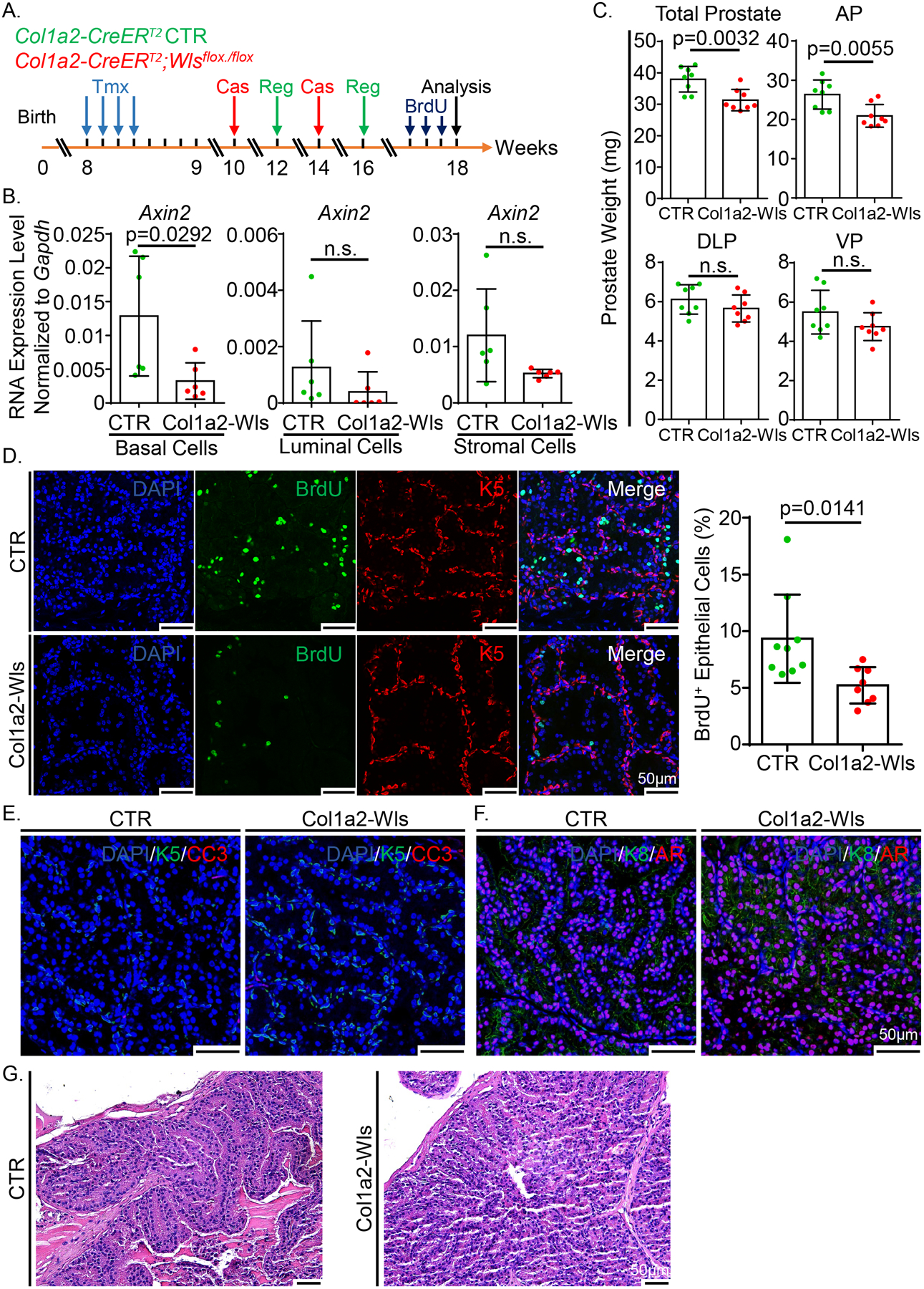

The prostate undergoes involution and regeneration in response to fluctuating testosterone levels. We reasoned that the stroma-derived Wnts play a crucial role in the extensive epithelial proliferation during androgen-stimulated prostate regeneration. To test this hypothesis, we treated 8-week-old Col1a2-Wls and Col1a2-CreERT2 control male mice with tamoxifen and then performed two cycles of castration and androgen replacement to induce epithelial turnover (Fig. 5A). We verified the specific and efficient ablation of Wls in the stromal cells (Supplementary Fig. 5A–D). Axin2 was downregulated in the basal and luminal cells but remained unchanged in the stromal cells of Col1a2-Wls mouse prostates (Fig. 5B). The average weight of prostate tissues in the Col1a2-Wls group was 82% of that of the mice in the control group, predominantly due to the decreased weight in the anterior prostate (Fig. 5C). Consistently, the proliferation index of the epithelial cells in the anterior prostate lobes of Col1a2-Wls mice was 44% less than that of the Col1a2-CreERT2 control mice (Fig. 5D), whereas the apoptotic index remained unchanged (Fig. 5E). The strong epithelial AR nuclear staining indicated that ablating stromal Wls did not affect AR signaling (Fig. 5F). In addition, there were no differences in prostate histology (Fig. 5G). We did not notice any change in the proliferation, apoptosis, AR staining, or histology in the other three prostate lobes (data not shown). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the Wnt proteins derived from the stromal cells are necessary for the sustained growth of the anterior prostate tissues in adult mice.

Figure 5.

Knockout of stromal Wntless reduces the proliferation of prostate epithelial cells during androgen-induced prostate regrowth. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. Tmx: tamoxifen. Cas: castration. Reg: regeneration. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Axin2 in FACS-isolated prostate basal, luminal and stromal cells from the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Dot graphs show means ± SD from six independent experiments. (C) Dot graphs show the quantification of prostate weight of 8 pairs of Col1a2-Wls and control mice. (D) Co-immunostaining of BrdU and Krt5 in anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. Dot graph shows means ± SD of the percentage of BrdU+ cells in prostate epithelial cells from eight pairs of mice. (E) Co-immunostaining of Krt5 and CC3 in anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) Co-immunostaining of Krt8 and AR in anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. (G) H&E staining of anterior prostate lobes of the Col1a2-Wls and control mice after androgen-induced regrowth. Scale bars, 50 μm.

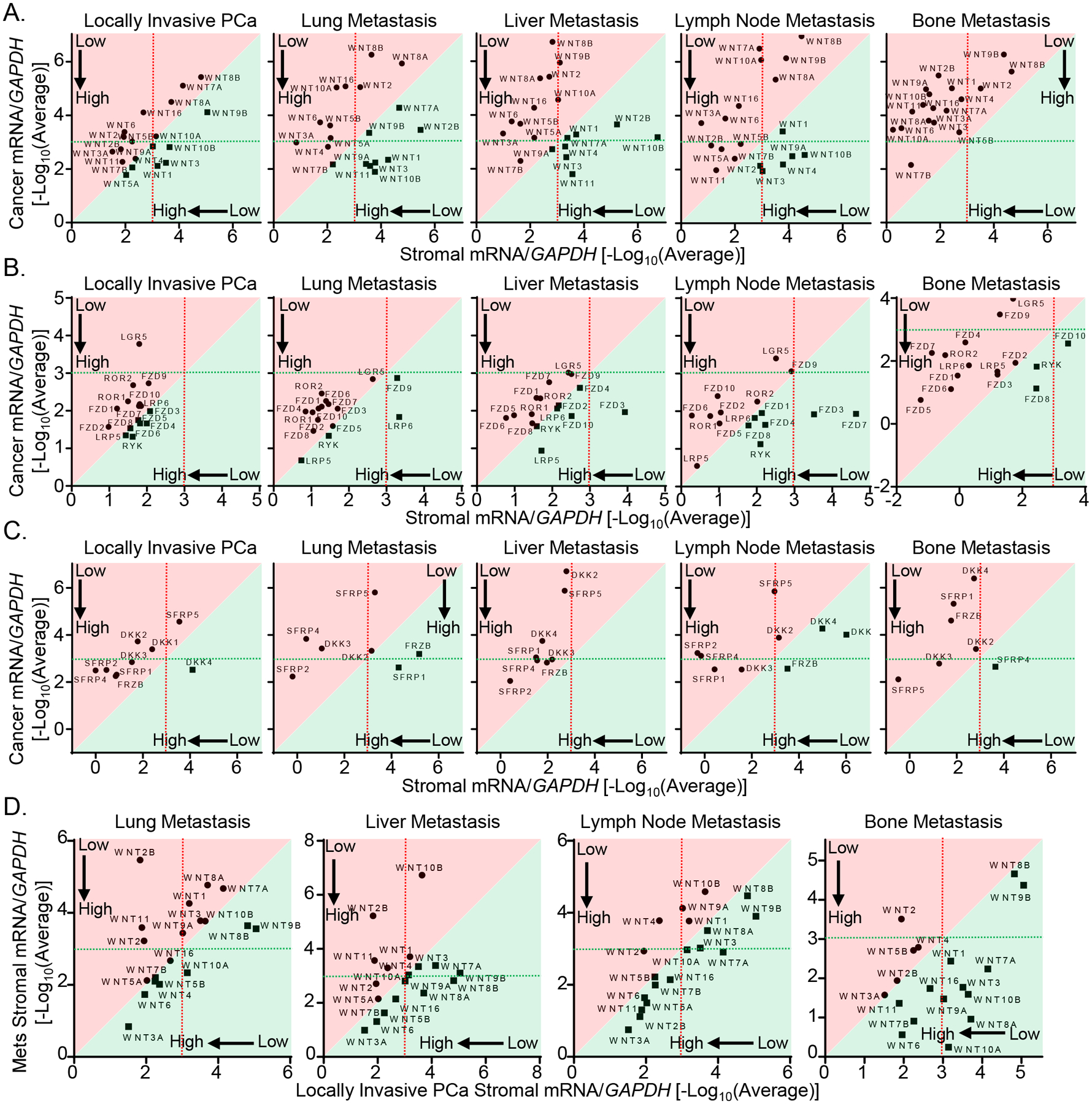

A systematic analysis of Wnt-related genes in human prostate cancer.

We sought to further investigate the spatial expression profiles of the Wnt signaling components in human prostate cancer including 10 locally invasive prostate cancers, 7 lung metastases, 8 liver metastases, 6 lymph node metastases and 4 bone metastases. We isolated tumor cells and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment by laser capture microscopy, extracted RNAs, and examined the expression levels of 44 Wnt signaling components by qRT-PCR. As the Wnt ligands usually function via local juxacrine signaling, we specifically captured stromal cells within 120 μm from cancerous glands and avoided any clusters of infiltrated immune cells (Supplementary Fig. 6A). The DV200 values for RNA quality were suitable for quantitation except for the bone stroma samples where degradation likely resulted from bone decalcification processes and low cell input (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

In addition to the Wnt components, we also assessed the lineage markers for epithelial cells (CDH1 and EPCAM) and stromal cells (ACTA2 and VIM) to verify the purity of the captured cells (Supplementary Fig. 6C). In summary, most Wnt ligands, receptors, and inhibitors were expressed at a higher level in the stromal cells than in the tumor cells (Figs. 6A–C). The most highly expressed Wnt ligands included WNT3A, WNT5A and WNT7B. FZD2, FZD5, FZD6 were among the several most highly expressed receptors. In addition, several Wnt inhibitors were highly expressed in the stromal cells. These results suggest that the stromal cells in advanced prostate cancer not only can provide the Wnt ligands to the tumor cells but also act as the receiving cells for Wnt ligands. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows the analysis of the Wnt-related genes differentially expressed between cancer and stromal cells. The other interesting finding from these data is that the expression levels of most Wnt ligands by the prostatic stromal cells were relatively lower than those by the stromal cells in distant metastases (Fig. 6D), indicating that the tumor cells in metastatic sites are in a Wnt richer microenvironment, supporting an important role of stroma derived Wnt signals in prostate cancer progression.

Figure 6.

A systematic analysis of Wnt-related genes in human advanced prostate cancer. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of 19 Wnt ligands in laser captured cancer and stromal cells from locally invasive PCa, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis and bone metastasis specimens. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt-related receptors/co-receptors in laser captured cancer and stromal cells from locally invasive PCa, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis and bone metastasis specimens. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of Secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs) and Dickkopf-related proteins (DKKs) in laser captured cancer and stromal cells from locally invasive PCa, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis and bone metastasis specimens. (D) Comparison of expressions of 19 Wnt ligands in laser captured stromal cells from locally invasive PCa with those in stroma of lung metastasis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis and bone metastasis specimens. Dot graphs represent means from 10 locally invasive PCa specimens, 7 lung metastasis specimens, 8 liver metastasis specimens, 6 lymph node metastasis specimens and 4 bone metastasis specimens. In all figures, genes shown in the areas shaded in red and green are expressed at a relatively higher level in stromal cells and cancer cells, respectively.

Discussion

Previously, Mehta et al has profiled the expression of Wnt ligands in developing urogenital sinus using the in-situ hybridization approach (17). Here, we used a more sensitive qRT-PCR approach in combination with flow cytometry to quantitatively compared the expression of different Wnt ligands in different cell lineages and at different developmental stages. Our study identified Wnt4 as the most highly expressed Wnt ligand in the prostate epithelia at early development and in adulthood. Wnt5a was highly expressed by the mesenchyme in E17 UGS but was downregulated in adult mouse prostate stromal cells. In contrast, Wnt2 and Wnt11 were highly expressed in prostate stromal cells throughout development. On the other hand, the in-situ hybridization approach can generate a topographic view of the expression of Wnt ligands in individual cellular compartments. For example, Wnt4 was shown to be expressed by proximal aspect of prostatic buds rather than the distal bud tips (17), which cannot be accomplished by our qRT-PCR analysis but was confirmed by the Visium analysis.

We determined that the stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment expressed higher levels of many Wnt ligands and inhibitors relative to neoplastic cells, particularly in prostate cancer metastases. Several ligands are consistently expressed at a relatively high level in stromal cells of the metastases, such as WNT3A, WNT5B, WNT6, WNT10A and WNT16. In addition, all the Wnt-related receptors/co-receptors including Frizzled receptors (FZD), Receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptors (ROR), Receptor like tyrosine kinase (RYK), LDL receptor related protein 5/6 (LRP 5/6) and Leucine rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) are highly expressed in the stromal cells of metastases, indicating that the stromal cells can also respond to the Wnt ligands. Our previous study showed that the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling in the prostate stromal cells suppresses normal prostate epithelial proliferation (18). Therefore, Wnt signaling in the epithelial and stromal cells may mediate opposite biological outcomes, which raises the question whether targeting stromal Wnt signaling should be avoided for the treatment of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer.

We demonstrated that ablating stromal Wls after E17 did not affect prostate basal and luminal cell lineage specification, which agrees with previous studies using β-catenin knockout models (11, 12). We also showed that the prostate stromal cell derived Wnt ligands are necessary for optimal epithelial proliferation and sustained growth of prostate tissues both at early development and in adulthood. This is also consistent with the observations that supplementing canonical Wnt ligands in prostate sphere and organoid assays promotes epithelial proliferation (29, 30) while ablating prostate epithelial β-Catenin suppresses prostate bud growth at early developmental stages (11, 12). Interestingly, ablating β-Catenin in adult mouse prostate epithelial cells using a Pb-Cre model did not affect prostate tissue homeostasis (11). In contrast, our study showed that disrupting stromal Wls attenuated epithelial cell proliferation and caused a reduction in prostate weight. Col1a2-Wls mice are indistinguishable from the control mice even 6 months after tamoxifen treatment (Data not shown), so it is unlikely that Wls deletion in stromal cells of other organs affected prostate epithelial proliferation. We showed that disrupting Wls in the prostate stromal cells attenuated the canonical Wnt activity in both the basal and luminal epithelial cells as determined by the expression of Axin2. In contrast, the canonical Wnt signaling (β-Catenin) was mainly disrupted in the luminal epithelial cells using the Pb-Cre model. Therefore, it is possible that the phenotype in adult Col1a2-Wls model is caused by the attenuated Wnt signaling in the basal cells. Or alternatively, loss of noncanonical Wnt signaling caused the decreased cell proliferation. Finally, we noticed that the growth suppression of the prostate gland is most prominent in the anterior lobe in our study (Fig. 4C and 5C). We showed previously that the Wnt-expressing CD90+Sca-1+ stromal cells are more abundant in the anterior lobes (31). Therefore, it is not surprising that disrupting the stromal Wls impacted the anterior prostate to the greatest extent.

Androgen signaling plays a critical role in prostate tissue homeostasis. Androgen deprivation leads to extensive epithelial apoptosis whereas androgen replacement drives epithelial proliferation and regeneration (32). Notably, androgen signaling in the prostate stromal cells regulates epithelial apoptosis and proliferation (33). The andromedin hypothesis proposed that androgen directly regulates the production of growth factors by the stromal cells and that these factors are essential for the survival and proliferation of the prostate epithelial cells (34). Although a strictly defined andromedin has not been identified, many Wnt ligands are regulated by androgen signaling including Wnt2, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt9a, Wnt10b, and Wnt11 (35–40). Our study determined that inhibiting Wnt secretion by the stromal cells attenuated epithelial proliferation. This supports the possibility that androgen signaling in the stromal cells promotes epithelial proliferation partially via Wnt. On the other hand, disrupting stromal Wls did not cause epithelial cell apoptosis. This indicates that androgen deprivation-induced epithelial apoptosis is unlikely a result of decreased Wnt ligands from the stromal cells.

Finally, based on the changes in the expression level of Axin2, we showed that disrupting Wls in prostate stromal cells attenuated canonical Wnt signaling in the prostate basal and luminal epithelial cells. Intriguingly, even though Axin2 was also highly expressed in the stromal cells, its expression was not affected when Wls was disrupted. This suggests that the canonical Wnt signaling in the prostate stromal cells was not affected in our study. One potential explanation is that Wnts can interact with the Frizzled receptors during intracellular trafficking and activate signaling. We have shown previously that altering canonical Wnt activity in prostate stromal cells can affect prostate epithelial proliferation (18). Therefore, the unaltered stromal canonical Wnt signaling in our model serendipitously excludes the possibility that the attenuated epithelial proliferation is caused indirectly by alterations in Wnt signaling in prostate stromal cells.

In summary, our study shows that the stromal cells are a major source of various Wnt ligands in developing and mature mouse prostates as well as in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer specimens. Ablating the stromal-derived Wnt ligands in vivo does not affect the survival of mouse prostate epithelial cells but attenuates their proliferative potential. We showed previously that the stromal cells also possess active Wnt signaling, which can indirectly affect epithelial cell biology (18). Therefore, it will be interesting to determine how active Wnt signaling in the stromal cells in prostate tumor microenvironment influences tumor progression in the future.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animals used in this study received humane care in compliance with the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NIH Publication, 1996 edition, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of University of Washington. The C57BL/6 and SCID/Beige mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Col1a2-CreERT2, 129S-Wlstm1.1Lan/J and B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm3(CAG-EYFP)Hze/J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction using mouse genomic DNA from tail biopsy specimens. The sequences of genotyping primers and the expected band sizes for PCR are listed in Table S1. PCR products were separated electrophoretically on 1% agarose gels and visualized via ethidium bromide under UV light.

Human specimens

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Washington (protocol code 2341 and date of approval: 5/10/2022). All rapid autopsy tissues were collected from patients who signed written informed consent under the aegis of the Prostate Cancer Donor Program at the University of Washington.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted using NucleoSpin RNA Plus XS Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA). RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using iScript™ Reverse Transcriptase Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). CDNA was pre-amplified using SsoAdvanced PreAmp Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA). QRT-PCR was performed using iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and detected on a Quantstudio Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers for target mouse genes were listed in Table S2.

Tamoxifen and BrdU treatment

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in corn oil and administrated i.p. into experimental mice at the specified age (5 mg/40 g/day for four consecutive days). BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (80 mg/kg/day) was administered 3 days before mice were sacrificed.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Dissociated single mouse prostate cells were incubated with florescence conjugated antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes. Information for the antibodies for FACS analysis and sorting is listed in Table S3. FACS analyses and sorting were performed using the BD LSR II and Aria I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), respectively.

Histology and immunostaining

Prostate tissues were fixed by 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining were performed with 5 microns sections. For hematoxylin and eosin staining, sections were processed as described previously (41). For immunostaining, sections were processed as described previously (41) and incubated with primary antibody in 3% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) overnight. Information for the antibodies is listed in Table S3. Slides then were incubated with secondary antibodies (diluted 1:250 in PBST) labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Sections were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Immunofluorescence staining was imaged using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Nikon, NY, USA). Images of immunofluorescence staining were analyzed by Fiji ImageJ. Cell number was determined by using the count feature in the software.

Renal capsule implantation

Urogenital sinuses (UGS) were dissected from Col1a2-Wls and Col1a2-CreERT2 control embryos. The UGS tissues were implanted under the renal capsules of SCID/Beige male hosts as described previously (42) with androgen pellets (15 mg/pellet, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) placed subcutaneously.

Castration and androgen replacement

Experimental mice were castrated at the age of 8 weeks using standard techniques (43). Two weeks after castration, androgen pellets (15 mg/pellet, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were placed subcutaneously to restore serum testosterone level and stimulate prostate regeneration for two weeks. Subsequently, androgen pellets were removed to re-induce prostate regression for two weeks and were replaced to re-induce regeneration for another two weeks.

qRT-PCR analysis of laser captured cells from the FFPE specimens

Ten-micron FFPE sections were mounted onto Arcturus PEN Membrane Frame Slides (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and dried overnight at room temperature. Sections were stained with Cresyl Violet (Acros Organic, New Jersey, NJ) and left at room temperature for one hour to dry. Adjacent 5-micron sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histology review and slide annotation was performed by a pathologist. Areas of the benign tissue, cancer, PIN, and extensive inflammation were marked if present. Areas of stroma within 120 microns of cancer cells were captured using the Arcturus XT (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with CapSure Macro LCM Caps (Thermo Scientific, LCM0211) and RNA was extracted using the truXTRAC FFPE RNA Plus Kit-Magnetic Bead (Covaris, Woburn, MA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. RNA quality (DV200) and quantity were assessed using the TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with High Sensitivity RNA Screentape (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using iScript Reverse Transcriptase kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA). CDNA was preamplified using SsoAdvanced PreAmp Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA). QRT-PCR was performed using iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and detected on a Quantstudio Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers for target human genes were listed in Table S4.

Visium spatial gene expression assay and data analysis

Visium Spatial Tissue Optimization Slides & Reagent Kit was used (PN-1000193, 10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA) to optimize the permeabilization of mouse urethra and prostate tissues. Briefly, frozen sections of intact urethra and prostate tissues from C57BL/6 mice were fixed for H&E staining and imaging following the manufacturer’s protocol (CG000160, 10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA). Then, tissue permeabilization was performed for 12 min and spatially barcoded full-length cDNA was generated using Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slide & Reagent Kit (PN-1000187, 10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA). CDNA amplification was conducted with 14 cycles and 10 μl cDNA was used for the library preparation. The libraries (650 pM with a final volume of 20 μL) were sequenced with NextSeq 1000/2000 P2 Reagents 100 cycles (Cat#20043738, Illumina, San Diego, CA) on the NextSeq2000 (Illumina), with Read 1: 28 cycles, i7 index:10 cycles, i5 index: 10 cycles, and Read 2: 90 cycles. The raw sequencing data were converted to FASTQ format using BCL Convert v1.2.1 on Illumina’s BaseSpace sequencing hub and downstream data processing, visualization, and statistics were completed using the following python libraries: Scanpy (ver.1.8.1), Pandas (1.1.5), Scipy (1.4.1), Seaborn (0.11.2), and Matplotlib (3.2.2). Raw spatial transcriptomics data were normalized using Scanpy preprocessing APIs. Gene counts per cell were normalized for their total counts over all genes and logarithmized. For this study, we defined spatial profiles of distal and proximal prostatic ducts within the sample tissues by aligning both histological features and spatial gene clusters identified using Scanpy clustering APIs. For Leiden cluster analysis, the dimensionality of the expression data was reduced to 50 with principal component analysis and then computed for neighborhood connectivity with a local neighborhood size of 15. Leiden clustering algorithm from Scanpy with a resolution of 0.1 consistently revealed spatial cluster distributions that closely resemble histological features of distal and proximal prostatic ducts across all the samples. “Contaminating” Visium spots from the clusters based on their histology were excluded from downstream analysis. Each cluster was labeled based on their histological identities for further gene expression analysis. The expression levels of Wnt ligands between the distal and proximal prostate were visualized using the violin plot API of the Seaborn package. Statistical tests and p-values annotated and described in the figures were performed using the Scipy package.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All experiments were performed using 3–9 mice in independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used to determine the significance in two-group experiments. For all statistical tests, the two-tail p≤0.05 level of confidence was accepted for statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their support to this study, thank the faculty and staff of the rapid autopsy teams for their contributions to the University of Washington Medical Center Prostate Cancer Donor Rapid Autopsy Program. We also thank Brenda Nghiem and Lori Kollath for sample identification and processing. This work was supported by NIH R01DK107436 (L.X.), R01DK092202 (L.X.), R01CA234715 (P.S.N.), Prostate Cancer Foundation 19CHAL11 (L.X., P.S.N.), DoD W81XWH-20-1-0039 (X.W.), the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50CA97186), the PO1 NIH grant (PO1 CA163227), and the Institute for Prostate Cancer Research (IPCR).

Source of support:

NIDDK, NCI, DoD, PCF,

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Staack A, Donjacour AA, Brody J, Cunha GR, and Carroll P 2003. Mouse urogenital development: a practical approach. Differentiation 71:402–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ittmann M 2018. Anatomy and Histology of the Human and Murine Prostate. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abate-Shen C, and Shen MM 2000. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer. Genes Dev 14:2410–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xin L 2019. Cells of Origin for Prostate Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 1210:67–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marker PC, Donjacour AA, Dahiya R, and Cunha GR 2003. Hormonal, cellular, and molecular control of prostatic development. Dev Biol 253:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H, Loh KM, and Nusse R 2014. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science 346:1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nusse R, and Clevers H 2017. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 169:985–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banziger C, Soldini D, Schutt C, Zipperlen P, Hausmann G, and Basler K 2006. Wntless, a conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell 125:509–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang BE, Wang XD, Ernst JA, Polakis P, and Gao WQ 2008. Regulation of epithelial branching morphogenesis and cancer cell growth of the prostate by Wnt signaling. PLoS One 3:e2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madueke I, Hu WY, Hu D, Swanson SM, Vander Griend D, Abern M, and Prins GS 2019. The role of WNT10B in normal prostate gland development and prostate cancer. Prostate 79:1692–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis JC, Thomsen MK, Taketo MM, and Swain A 2013. beta-catenin is required for prostate development and cooperates with Pten loss to drive invasive carcinoma. PLoS Genet 9:e1003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons BW, Hurley PJ, Huang Z, Ross AE, Miller R, Marchionni L, Berman DM, and Schaeffer EM 2012. Wnt signaling though beta-catenin is required for prostate lineage specification. Dev Biol 371:246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allgeier SH, Lin TM, Vezina CM, Moore RW, Fritz WA, Chiu SY, Zhang C, and Peterson RE 2008. WNT5A selectively inhibits mouse ventral prostate development. Dev Biol 324:10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L, Pu Y, Hu WY, Birch L, Luccio-Camelo D, Yamaguchi T, and Prins GS 2009. The role of Wnt5a in prostate gland development. Dev Biol 328:188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prins GS, and Putz O 2008. Molecular signaling pathways that regulate prostate gland development. Differentiation 76:641–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X, Wang Y, Jiang M, Bierie B, Roy-Burman P, Shen MM, Taketo MM, Wills M, and Matusik RJ 2009. Activation of beta-Catenin in mouse prostate causes HGPIN and continuous prostate growth after castration. Prostate 69:249–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta V, Abler LL, Keil KP, Schmitz CT, Joshi PS, and Vezina CM 2011. Atlas of Wnt and R-spondin gene expression in the developing male mouse lower urogenital tract. Dev Dyn 240:2548–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei X, Zhang L, Zhou Z, Kwon OJ, Zhang Y, Nguyen H, Dumpit R, True L, Nelson P, Dong B, et al. 2019. Spatially Restricted Stromal Wnt Signaling Restrains Prostate Epithelial Progenitor Growth through Direct and Indirect Mechanisms. Cell Stem Cell 24:753–768 e756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kypta RM, and Waxman J 2012. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 9:418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, Montgomery B, Taplin ME, Pritchard CC, Attard G, et al. 2015. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 161:1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu X, Wang Y, DeGraff DJ, Wills ML, and Matusik RJ 2011. Wnt/beta-catenin activation promotes prostate tumor progression in a mouse model. Oncogene 30:1868–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valkenburg KC, Yu X, De Marzo AM, Spiering TJ, Matusik RJ, and Williams BO 2014. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in a subpopulation of murine prostate luminal epithelial cells induces high grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia. Prostate 74:1506–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, Lee RJ, Zhu H, Broderick KT, Desai R, Fox DB, Brannigan BW, Trautwein J, et al. 2015. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science 349:1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Campisi J, Higano C, Beer TM, Porter P, Coleman I, True L, and Nelson PS 2012. Treatment-induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nat Med 18:1359–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon OJ, Choi JM, Zhang L, Jia D, Li Z, Zhang Y, Jung SY, Creighton CJ, and Xin L 2020. The Sca-1(+) and Sca-1(−) mouse prostatic luminal cell lineages are independently sustained. Stem Cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon OJ, Zhang L, Jia D, and Xin L 2020. Sox2 is necessary for androgen ablation-induced neuroendocrine differentiation from Pten null Sca-1(+) prostate luminal cells. Oncogene. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon OJ, Zhang L, and Xin L 2016. Stem Cell Antigen-1 Identifies a Distinct Androgen-Independent Murine Prostatic Luminal Cell Lineage with Bipotent Potential. Stem Cells 34:191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph DB, Henry GH, Malewska A, Reese JC, Mauck RJ, Gahan JC, Hutchinson RC, Malladi VS, Roehrborn CG, Vezina CM, et al. 2021. Single-cell analysis of mouse and human prostate reveals novel fibroblasts with specialized distribution and microenvironment interactions. J Pathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karthaus WR, Iaquinta PJ, Drost J, Gracanin A, van Boxtel R, Wongvipat J, Dowling CM, Gao D, Begthel H, Sachs N, et al. 2014. Identification of multipotent luminal progenitor cells in human prostate organoid cultures. Cell 159:163–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahi P, Seethammagari MR, Valdez JM, Xin L, and Spencer DM 2011. Wnt and Notch pathways have interrelated opposing roles on prostate progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Stem Cells 29:678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon OJ, Zhang Y, Li Y, Wei X, Zhang L, Chen R, Creighton CJ, and Xin L 2019. Functional Heterogeneity of Mouse Prostate Stromal Cells Revealed by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. iScience 13:328–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaacs JT 1985. Control of cell proliferation and death in normal and neoplastic prostate: A stem cell model. In Benigh prostatic hyperplasia. C.D.S. Rodgers CH, Cunha GR, editor. Bethesda. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunha GR 1973. The role of androgens in the epithelio-mesenchymal interactions involved in prostatic morphogenesis in embryonic mice. Anat Rec 175:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan G, Fukabori Y, Nikolaropoulos S, Wang F, and McKeehan WL 1992. Heparin-binding keratinocyte growth factor is a candidate stromal-to-epithelial-cell andromedin. Mol Endocrinol 6:2123–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simitsidellis I, Gibson DA, Cousins FL, Esnal-Zufiaurre A, and Saunders PT 2016. A Role for Androgens in Epithelial Proliferation and Formation of Glands in the Mouse Uterus. Endocrinology 157:2116–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y, Yu H, Pask AJ, Fujiyama A, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Shaw G, and Renfree MB 2018. Hormone-responsive genes in the SHH and WNT/beta-catenin signaling pathways influence urethral closure and phallus growth. Biol Reprod 99:806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiros GJ, Ceruti JM, Castellanos ML, Kusinsky AG, and Balana ME 2017. Androgens modify Wnt agonists/antagonists expression balance in dermal papilla cells preventing hair follicle stem cell differentiation in androgenetic alopecia. Mol Cell Endocrinol 439:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Cheng YI, Pan QI, Hu W, Xu LI, Meng X, Wu J, Xie C, Yan H, and Sun Z 2016. Changes in mitotic reorientation and Wnt/AR signaling in rat prostate epithelial cells exposed to subchronic testosterone. Exp Ther Med 11:1361–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng D, Decker KF, Zhou T, Chen J, Qi Z, Jacobs K, Weilbaecher KN, Corey E, Long F, and Jia L 2013. Role of WNT7B-induced noncanonical pathway in advanced prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res 11:482–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu H, Mazor M, Kawano Y, Walker MM, Leung HY, Armstrong K, Waxman J, and Kypta RM 2004. Analysis of Wnt gene expression in prostate cancer: mutual inhibition by WNT11 and the androgen receptor. Cancer Res 64:7918–7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi N, Zhang B, Zhang L, Ittmann M, and Xin L 2012. Adult murine prostate basal and luminal cells are self-sustained lineages that can both serve as targets for prostate cancer initiation. Cancer Cell 21:253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xin L, Ide H, Kim Y, Dubey P, and Witte ON 2003. In vivo regeneration of murine prostate from dissociated cell populations of postnatal epithelia and urogenital sinus mesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 Suppl 1:11896–11903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valdez JM, Zhang L, Su Q, Dakhova O, Zhang Y, Shahi P, Spencer DM, Creighton CJ, Ittmann MM, and Xin L 2012. Notch and TGFbeta form a reciprocal positive regulatory loop that suppresses murine prostate basal stem/progenitor cell activity. Cell Stem Cell 11:676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.