Abstract

Despite high levels of need, racial and ethnic minoritized (REM) youth are much less likely than their White peers to engage in mental health treatment. Concerns about treatment relevance and acceptability and poor therapeutic alliance have been shown to impact treatment engagement, particularly retention, among REM youth and families. Measurement-based care (MBC) is a client-centered practice of collecting and using client-reported progress data throughout treatment to inform shared decision-making. MBC has been associated with increased client involvement in treatment, improved client-provider communication, and increased satisfaction with treatment services. Despite its promise as a treatment engagement strategy, the use of MBC in this capacity has not been studied with REM youth or systematically modified to address the needs of culturally-diverse populations. In this paper, we propose a culturally-modified version of MBC, Strategic Treatment Assessment with Youth (STAY), to improve treatment engagement among REM youth and families. Specifically, STAY is designed to target perceptual barriers to treatment to improve treatment retention and ultimately, client outcomes. The four STAY components (i.e., Introduce, Collect, Share, and Act) are based on an existing MBC practice framework and modified to address perceptual barriers to treatment among REM youth. The application of this model to clinical efforts is presented via a case example. Finally, future research directions to explore the use of MBC as a treatment retention strategy with REM populations are provided.

Keywords: measurement-based care, racial and ethnic minoritized youth, mental health services, cultural modification, treatment engagement

Racial and ethnic minoritized (REM) youth are a large and growing population within the United States (U.S.). In 2019, more than half of all youth in the U.S. identified as a member of a REM group (Frey, 2019), with approximately two in three youth projected to be a race other than non-Hispanic White by 2060 (Vespa et al., 2018). Numerous studies have pointed to higher rates of mental health concerns among African-American/Black, Asian American, Latina/o, and Native American youth and adolescents as compared to their White peers (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Georgiades et al., 2018; McLaughlin et al., 2007). Moreover, REM youth with mental health concerns have been noted to experience more persistent, severe and debilitating symptoms than White youth (McGuire & Miranda, 2008). Despite this greater need, REM youth with mental health concerns are less likely to initiate and remain in mental health treatment, with significant negative and long-term implications (Alegria et al., 2011; Cummings et al., 2011). Thus, racial and ethnic disparities in youth engagement in mental health treatment are a serious public health concern (Alegria et al., 2011), and improving initial and ongoing treatment engagement among REM youth with mental health needs is crucial to achieving more equitable public health outcomes for this population (Ingoldsby, 2010).

In the following review, we discuss how treatment engagement is defined in youth mental health services, disparities in and barriers to treatment engagement among REM youth, and previous efforts to improve treatment engagement among REM youth populations. These findings informed our proposed model to address gaps related to perceptual barriers to treatment among REM youth.

Treatment Engagement

Treatment engagement is a multi-phase process which begins with the recognition of youth symptoms, followed by the referral of youth and their families to a mental health provider and the youth being seen by a provider (McKay & Bannon, 2004). Further, treatment engagement has historically included both initial engagement of the youth or family as well as retention in treatment over time (McKay & Bannon, 2004). More nuanced expansions of this definition include the therapists’ assessment of the appropriateness of treatment termination (Johnson et al., 2008). Here, successful treatment completion or termination is typically marked by the youth, family and clinician agreeing to end treatment when there is no longer a need; this is contrasted with unsuccessful termination or “dropout,” which occurs when the youth and family opt to end treatment before the clinicians believes it is appropriate (Johnson et al., 2008). Other scholars have underscored the importance of going beyond session attendance or treatment completion as a measure of treatment engagement to include behavioral components of treatment, such as session participation and homework completion, and attitudinal dimensions of engagement, which refer to the youth or family’s commitment to or emotional investment in treatment (Staudt, 2007). Thus, a comprehensive picture of ongoing treatment engagement and retention for youth likely requires attention to multiple areas of focus, including session attendance, participation in treatment, attitudinal engagement, and successful treatment completion.

Treatment Engagement Among REM Youth

Despite a range of treatment engagement definitions, the primary method of assessing treatment engagement continues to be session attendance (Gopalan et al., 2010). Using this measure, the average length of treatment among REM youth in urban, inner-city clinics has been found to be three to four sessions (McKay et al., 2002), a number significantly lower than estimates from White youth (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2008). Further, REM status has been found to consistently differentiate between those who complete treatment and those who terminate early (de Haan et al., 2018). For instance, in an early study, Kazdin and colleagues (1995) found a significant difference in dropout rates between African-American/Black (i.e., 59.6%) and White (i.e., 41.7%) youth with externalizing problems. In another, Saloner and colleagues (2014) noted that African-American/Black and Latina/o youth were significantly less likely than White youth to complete treatment for substance use. Additional studies have found similar results, noting higher rates of treatment termination among REM youth than their White peers (Bagner & Graziano, 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2011; Kazdin et al., 1997; Miller et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2013; Stein et al., 2012). These findings further highlight the need to address treatment engagement among REM youth and families (de Haan et al., 2018).

Barriers to Treatment Engagement Among REM Youth

Disparities in mental health treatment engagement by race and ethnicity have been attributed to numerous factors (Pumariega et al., 2005) including sociocultural barriers at the organizational, structural and clinical levels (Betancourt et al., 2003). One approach to conceptualizing barriers to treatment engagement has differentiated between pragmatic and perceptual barriers to treatment (Bannon & McKay, 2005; Yeh et al., 2005). Pragmatic, or logistical or concrete barriers, include various structural and sociopolitical barriers, such as poverty (Carrillo et al., 2011), lack of insurance (Cohen & Martinez, 2014), and insufficient access to community mental health services (Glied & Cuellar, 2003). Perceptual barriers among youth and caregivers, in turn, include stigma regarding mental health services (Alvidrez et al., 2008; Turner et al., 2015) and concerns about poor alliance or clinician cultural competence (Flicker et al., 2008; Garcia & Weisz, 2002). Additional perceptual barriers include thoughts and beliefs about treatment, such as perceived need for treatment, perceived relevance of treatment, parental expectations about the therapeutic process, and other such ethnocultural beliefs (e.g., that caregivers should be able to help their children overcome mental health difficulties (Kazdin et al., 1997; McKay et al., 2011; Nock & Kazdin, 2001). Together, these barriers have been shown to disproportionately affect REM youth leading to disparities in engagement and retention in mental health care services (Gopalan et al., 2010). Other research has further explored perceptual factors among REM youth and families as barriers to treatment engagement (Lindsey et al., 2014). For instance, Flicker and colleagues (2008) found that the relation between different levels of therapeutic alliance and treatment dropout was stronger among Latina/o as compared to White families, suggesting that insufficient attention to cultural factors by therapists, and the systems or organizations for whom therapists work, contributed to difficulties with treatment engagement among Latina/o families. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop and evaluate evidence-based interventions to target perceptual barriers uniquely experienced by REM youth and their caregivers to increase treatment retention of REM youth (Bannon & McKay, 2005).

Increasing Treatment Engagement

A significant body of literature has examined approaches to increase treatment engagement among youth and families. These interventions are organized into two groups: those implemented prior to or early on in treatment and those integrated throughout treatment (Nock & Ferriter, 2005). Examples of strategies in the first group include providing appointment reminders (Watt et al., 2007), brief interventions to address pragmatic barriers to treatment (McKay, McCadam, et al., 1996; McKay et al., 1998) and family therapy-based engagement strategies (e.g., joining, family genograms; Coatsworth et al., 2002; Dakof et al., 2015; Szapocznik et al., 1988). These interventions have demonstrated varying levels of success, with pre- and early-treatment interventions leading to improvements in initial engagement, with less support for retaining families in services once they have begun (Ingoldsby, 2010). Among the latter group, interventions integrated throughout the treatment, strategies include both structural changes to treatment delivery (e.g., offering monetary incentives for attendance at appointments, increasing training for providers, telemental health) and modifications to clinical methods integrated throughout treatment (Ingoldsby, 2010). Adding family support sessions (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003; Prinz & Miller, 1994) and motivational interviewing components (Grote et al., 2008; Grote et al., 2007; Lindsey et al., 2009; Nock & Ferriter, 2005) have been examined but again, findings are mixed. Specifically, some interventions (e.g., monetary incentives; Guyll, Spoth & Redmond, 2003) have demonstrated a positive impact on initial engagement but not retention; others, namely those which sought to address families’ motivations, expectations and needs for treatment, have led to increased success in improving treatment engagement and retention. Moreover, while occasionally including diverse populations of youth with more severe mental health needs, most treatment engagement research has less systematically focused on improving treatment engagement among REM populations (Ingoldsby, 2010). Overall, given the scale of treatment engagement barriers disproportionally affecting REM youth and their families, additional treatment engagement intervention development and testing specifically for REM youth and families is needed (Yancey et al., 2006).

STAY: A Model for Engaging REM Youth in Treatment

The current paper describes a novel, culturally-informed engagement model, Strategic Treatment Assessment with Youth (STAY), to improve ongoing mental health treatment engagement for REM youth and their families. In the following section, we provide a rationale for STAY, including the use of measurement-based care (MBC) as a treatment engagement strategy and the need for modifications to optimize cultural fit and engagement outcomes among REM youth and families. Next, we describe how STAY was developed, based on a foundation of “MBC as usual” materials with three modifications selected to correspond to barriers to treatment engagement (i.e., service relevance and acceptability and therapeutic alliance) uniquely experienced by REM youth. We then provide a clinical case example to illustrate the model and guide its practical application, followed by a description of STAY intended outcomes.

Promoting Engagement Through Measurement-Based Care (MBC)

One particularly promising intervention to promote ongoing engagement and ultimately, treatment retention, among REM youth is measurement-based care (MBC). MBC is an evidence-informed, client-centered practice which involves collecting client-reported progress data throughout treatment to inform shared decision-making (Scott & Lewis, 2015). MBC includes three components: (a) collecting progress data from the client to track goals, (b) sharing progress data with the client and eliciting their reactions, and (c) acting upon progress data together (Dollar et al., 2019). MBC typically involves collecting standardized, client-reported, diagnosis-specific symptom measures (Fortney et al., 2017). However, MBC can also include monitoring progress on other indicators of client wellness and functioning, such as individualized goals, functioning in various life domains, readiness to change, session feedback and the therapeutic relationship (Scott & Lewis, 2015). MBC has been associated with improved client outcomes for a variety of treatment settings and presenting concerns among adults (Guo et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2018; Shimokawa et al., 2010; Trivedi et al., 2006) and youth (Bickman et al., 2011). A recent Cochrane review indicated that using standardized assessments to track client progress, but not adjust the treatment approach when needed, results in little to no benefit (Kendrick et al., 2016). This is a signal that MBC’s effectiveness is contingent on treatment adjustments. Readers should note that the literature base supporting MBC is still growing, and there are fewer rigorous studies of MBC with youth than with adults (see Parikh et al., 2020 for a recent review of MBC with youth). MBC is purported to improve treatment engagement through collaborative work between the clinician and client to set goals, track progress, and evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment approach (Lambert et al., 2003; Resnick & Hoff, 2020). Indeed, research has found that MBC activates numerous treatment engagement mechanisms, including increasing client expectation of treatment gains, improving therapeutic alliance, and signaling when treatment should be adjusted based on client progress (Castonguay et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2019). Several studies have found that, when used to enhance usual care, MBC is associated with increased client sense of involvement in treatment (Eisen et al., 2000), increased knowledge about one’s diagnosis (Dowrick et al., 2009), improved client-provider communication (Dowrick et al., 2009), and increased satisfaction with treatment services (Castonguay et al., 2006). Also, a review of 89 successful engagement interventions from 40 randomized clinical trials found that psychoeducation about services and assessment were two of the most frequent practices included in those interventions (Becker et al., 2015). These practices are highly consistent with those contained in MBC, supporting the association between MBC practices and engagement.

Despite MBC’s potential to improve engagement in mental health treatment services (Scott & Lewis, 2015), no research to our knowledge has examined MBC as an engagement strategy to reduce mental health disparities among any specific client population. However, given its inherent focus on personalized treatment planning, shared decision-making and client-centered communication, MBC has clear potential to address many of the unique barriers to treatment faced by REM youth.

STAY Foundation: MBC As Usual

STAY is based on a foundation of MBC delivered “as usual” across various client populations and clinical settings. We used the MBC clinical model developed by and disseminated throughout the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for the Veterans Health Administration Measurement-Based Care in Mental Health initiative (Resnick & Hoff, 2020). The model was designed to support MBC across the entire mental health continuum of care and can be used by practicing clinicians serving clients with a wide variety of presenting concerns, acuity, and mental health treatment experiences. The model consists of three components: 1) “Collect”, 2) “Share”, and 3) “Act.” Collect involves providing a rationale for using measures as well as explaining how measures will be used by the clinician and client1 to track progress and make collaborative decisions throughout treatment. The role of the client as an important and active partner in decision making is emphasized during Collect. The rationale for and description of how MBC works may need to be repeated throughout treatment to ensure that the client understands and can participate in the process. This component also includes selecting and administering measures required by clinical program or site (if applicable) or collaboratively considering additional measures relevant to the client and determining the frequency of administration.

The next component, Share, refers to sharing the results with the client in a timely manner, ideally immediately after the measures are completed. Key elements of the share component include reporting the scores to the client in a non-directive, transparent way, explaining their meaning, and discussing whether they match the client’s subjective experience. Discussions should touch upon the client’s understanding of progress over time, scores on individual items that are noteworthy (e.g., strengths and areas for future clinical focus), as well as how scores fit into existing norms, if applicable. Clinicians are also prompted to provide clarification about the measures or scores as needed and then capture the scores and details about the discussion with the client in the medical record.

The final component, Act, involves the clinician and client engaging in a transparent, collaborative conversation about the scores to evaluate progress, generate possible adjustments to the treatment approach, if applicable, and then engaging in shared decision-making to select the best option. Shared decision-making includes an emphasis on client choice, providing options with decision support, and opportunity to explore and make decisions (Elwyn et al., 2012). The Act component can also occur based on a recent outcome measure score from another provider’s visit or based on more than one recently-collected score if available. Clinicians are encouraged to engage in shared decision making with the client, which may involve some compromise if there is a lack of agreement on priorities and desired next steps.

The Collect, Share, Act model emphasizes the importance of enhancing the quality of clinical care based on an individualized, responsive, collaborative approach with the client. This model is highly pragmatic yet non-specific to any given set of measures, client presenting concerns or clinical setting. Therefore, it offers a flexible, adaptable foundation that can be adjusted and modified for more specific MBC implementation purposes.

STAY: MBC Modifications to Improve Cultural Fit

While treatment engagement is reasonably targeted by MBC as usual (Resnick & Hoff, 2020), we posit the need for several modifications to MBC in order to optimize treatment engagement among REM youth populations that will target perceptual barriers. We propose several modifications to MBC to ensure that two critical perceptual barriers, 1) treatment relevance and acceptability; and 2) therapeutic alliance, are deliberately and adequately addressed (Staudt, 2007; Stevens et al., 2006). STAY is specifically for REM youth and their parent(s) or caregiver(s) involved in treatment, so it is designed to address both youth and caregiver perceptions of treatment.

Treatment Relevance and Acceptability

Treatment relevance and acceptability refers to what extent the youth and caregiver believe services are appropriate, important, satisfactory and in line with their expectations (Kazdin, 2000; Kazdin & Wassell, 2000; Staudt, 2007). Past research has pointed to the central role of treatment relevance and acceptability in subsequent treatment engagement (Staudt, 2007; Stevens et al., 2006). For instance, caregiver-reported acceptability of treatment has been linked to actual treatment caregivers pursued and youth received (Krain et al., 2005). Further, studies have demonstrated the importance of treatment relevance and acceptability among REM populations as the fit of evidence-based interventions has been questioned for REM youth populations (Arora et al., 2017). As such, attending to youth and caregiver perceptions about treatment process, outcomes and need has been highlighted as a critical aspect of improving treatment relevance and acceptability (Ingoldsby, 2010), particularly among REM youth and families (Alegría et al., 2002; Calzada et al., 2013).

Therapeutic Alliance

Therapeutic alliance refers to the “the relational, emotional, and cognitive connection between the youth client and a therapist (e.g., bond, trust, feeling allied, and positive working relationship” (Karver et al., 2008; p. 16). Indeed, the importance of a collaborative bond and shared decision-making between the clinician and client is a key component of therapeutic alliance (Bordin, 1976; Martin et al., 2000). Caregiver-reported problems with the therapeutic relationship have been found to account for more variance in premature treatment termination than caregivers’ perceptions of treatment need or treatment effectiveness (Garcia & Weisz, 2002). Numerous findings also point to the relative importance of the therapeutic alliance among REM youth. For instance, in a recent review of mental health treatment dropout among REM youth, therapeutic relationship emerged as a consistent predictor of dropout among numerous studies (de Haan et al., 2018). Specifically, early problems with alliance (between Sessions 1 and 2) and discrepancies between caregiver-clinician and youth-clinician alliance predicted premature termination for REM families (Flicker et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2006).

Modification Approach

We used the heuristic framework proposed by Barrera & Castro (2006) to inform modifications to improve cultural fit. Proposed modifications are “selective and directed” based on past research indicating the need for clinical practices and processes that improve REM youth treatment engagement (Lau, 2006). We focused specifically on findings that address how to promote REM youth and caregiver beliefs about treatment relevance and acceptability and therapeutic alliance.

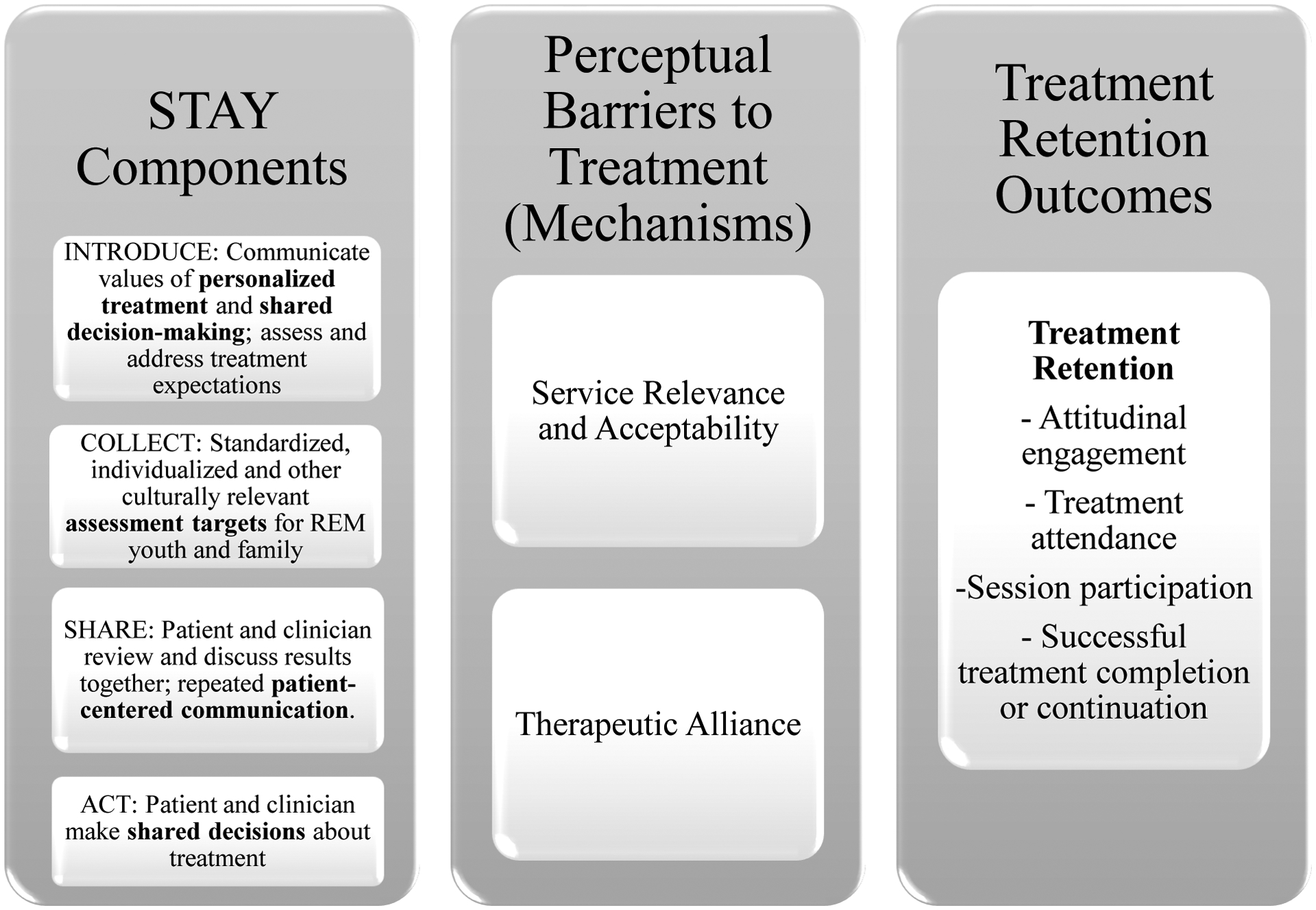

Based on our review of literature detailing the link of MBC to treatment engagement, as well as these two treatment engagement barriers for REM youth, we posited that three modifications would be beneficial when using MBC as a treatment engagement intervention with this population. Each modification is designed to target both perceptual barriers to ongoing treatment engagement and retention among REM youth (see Table 1). Next, we describe each modification and literature supporting its association with the targeted barriers. We then provide a clinical case example to illustrate the model and guide its practical application. The STAY conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

STAY Modifications for REM Youth

| MBC Component | Modification | Description | Rationale | Target Engagement Barrier Service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance and Acceptability | Therapeutic Alliance | ||||

| Collect | Add “Introduce” | Extract “Rationale” as a distinct component and called “Introduce” | Emphasize shared decision-making with measures | ✓ | ✓ |

| Collect, Share, Act | Include an Idiographic Measure | Include individualized measure(s) specific to client goals and progress markers | Standardized measures can be narrowly focused on clinical symptoms and may have limited validity with REM groups | ✓ | ✓ |

| Collect, Share, Act | Include a Sociocultural Measure | Include measure(s) of perceived discrimination, racial identity, or other variable related to race, ethnicity, nationality, or cultural identity | Ensure explicit assessment and discussion of issues related to race that may pertain to building alliance and/or treatment goals. | ✓ | ✓ |

Figure 1.

Strategic Treatment Assessment with Youth (STAY) Conceptual Framework

Modification 1: Focus on Introduce

The “Collect” component of MBC includes providing youth and caregivers with a rationale about why youth- and/or caregiver-reported measures will be collected and how they will be used (Resnick & Hoff, 2020). The rationale is provided in the context of client-clinician communication about key aspects of the treatment process and emphasis on shared decision-making, both of which improve perceived treatment acceptability (Klingaman et al., 2015) and therapeutic alliance (Joosten et al., 2008). However, despite being even more relevant for REM patients, research has indicated that client-clinician communication about the treatment process and shared decision-making may occur less often with this population (Lin & Kressin, 2015). Indeed, misconceptions about one’s illness and how treatment will work has been cited as a barrier to treatment among REM clients (Uebelacker et al., 2012). Findings from a systematic review of 23 studies on communication interventions to improve REM treatment engagement found that discussing treatment relevance, explaining service delivery in a way that is consistent with how the client understands their own illness and care, and attending to confidentiality issues are key elements of client-clinician communication that improve treatment engagement among REM populations (Aggarwal et al., 2016).

Further, establishing early therapeutic alliance and trust is a significant predictor on ongoing engagement and treatment retention for REM youth (Gopalan et al., 2010; Robbins et al., 2006). In fact, among a predominantly REM youth sample, developing a foundation for a collaborative working relationship and engaging the youth and family in the helping process as early as the initial interview has been associated with ongoing engagement as measured by session attendance for up to eighteen weeks (McKay, Nudelman, et al., 1996)

In line with these recommendations, the STAY model further emphasizes the importance of providing a rationale by including a distinct first component called, “Introduce.” The “Introduce” component ensures an explicit focus on establishing trust and developing a therapeutic alliance as early as the first session of treatment. During “Introduce,” the clinician discusses how measures are collected, used, and stored confidentially; whether other providers have access to them; and that any changes in the treatment approach will be based on a conversation between the youth, caregiver and clinician. Although features of the original model, having a distinct “Introduce” step emphasizes the importance of explaining all of these elements to clients as part of improving treatment relevance and acceptability. Separating the rationale into “Introduce” also ensures that client-clinician communication about shared decision-making, based on collaboratively monitoring, discussing and acting on client-reported progress throughout treatment, stays central to the process.

Modification 2: Include an Individualized Measure

Standardized patient-reported symptom measures, which have the same established items, response options, administration guidelines and scoring rules for every client, are the prevailing type of measure used in MBC (Gondek et al., 2016; Krägeloh et al., 2015). Standardized measures sometimes also allow clinicians to estimate clinical cutoffs based on norm references and visualize and discuss progress with clients based on established benchmarks and expected recovery curves (Ashworth et al., 2019; De Jong, 2017).

While using a standardized measure specific to the client’s presenting concern is conventional, there is a burgeoning emphasis in research and practice to incorporate both standardized and individualized measures within an MBC approach (Chorpita et al., 2014; Connors et al., 2020; Lyon et al., 2017). Integrating individualized goal tracking with standardized symptom monitoring has become recommended clinical practice in MBC for optimal engagement and client outcomes (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018). Individualized measures, also referred to as idiographic or patient-generated measures, gather client-reported progress on a personalized treatment goal using an established metric to rate progress over time (Lloyd et al., 2019; Sales & Alves, 2016). Examples include fear ratings, instances of self-harm, daily school attendance, instances of behavioral activation or pleasurable activities, use of time out, or any other client-generated goal that can be tracked with an agreed-upon metric over an agreed-upon period of time. Goal attainment scaling and the Youth Top Problems rating scale provide structures for developing these measures and a rating system (Kiresuk et al., 1982; Turner-Stokes, 2009; Weisz et al., 2011).

The use of idiographic measures is believed to improve treatment relevance and acceptability and therapeutic alliance (Lewis et al., 2018), and thus treatment engagement due to offering a personalized approach to tracking and discussing progress (Sales & Alves, 2012) (Sales & Alves, 2012). A recent study with a national sample of 504 clinicians found that clinicians hold more positive views of individualized measures which they reported are more relevant and acceptable to clients (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018) Among REM youth in particular, the use of standardized measures have been questioned (Garland et al., 2003; Hunsley & Mash, 2007; Kazdin, 2005). This is attributable to the fact that the cultural validity and reliability of standardized assessment tools is limited for REM populations (Huey & Polo, 2008). Accordingly, clinicians should augment standardized assessments with other data sources to determine which elements are most relevant for any individual client (Hunsley & Mash, 2007; McLeod et al., 2013). As such, the STAY model augments a standardized measure with an idiographic measure, a practice that has empirical support with youth populations (see Weisz et al., 2011; Wolpert et al., 2012).

Modification 3: Include a Sociocultural Measure

The STAY model includes incorporating at least one sociocultural measure of perceived discrimination, racial identity, or other variable related to race, ethnicity, nationality, or cultural identity into the practice. A growing body of research shows that discussing race, experiences of racism or discrimination, and racial differences in treatment is a critically important cultural competency skill for clinicians to build a trusting therapeutic relationship and environment with REM clients (Cardemil & Battle, 2003; Fuertes et al., 2002). In fact, in one study of 102 young adult and adult outpatient clients revealed that, as compared to White clients, REM clients felt it was significantly more important that their clinician be aware of their racial/ethnic group’s history of discrimination and that their clinician discuss issues related to race and ethnicity in treatment (Meyer & Zane, 2013). Including explicit assessment and discussion of these race, ethnicity and culture-related issues in treatment has been directly linked to treatment relevance and acceptability and therapeutic alliance across numerous studies (Calzada et al., 2013; Fox et al., 2017; Knox et al., 2003; Uebelacker et al., 2012). Accordingly, assessing factors related to race, ethnicity and culture are likely key to improving treatment relevance and acceptability and increase therapeutic alliance among REM youth and families.

Many potentially relevant assessment targets in this broad category exist, including personal experiences of racism and/or discrimination, acculturation, social determinants of health or other socioeconomic factors which are more likely to impact REM youth. Clinical approaches for assessing cultural factors related to treatment are sometimes semi-structured (c.f., Lewis-Fernández & Díaz, 2002) or draw upon a handful of items related to a construct of interest such as discrimination from a more global measure (Gee et al., 2009). However, we recommend using a client-reported measure with standardized items to assess race or ethnicity-related factors and use those results to start a discussion with the youth and caregiver about how and whether race, ethnicity and/or culture influences their beliefs, expectations, goals, or preferences about treatment. Moreover, this conversation should not end at the initial diagnosis and assessment phase but continue throughout treatment.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of validated screening and assessment tools for sociocultural and community factors (e.g., discrimination, racism, social cohesion) that pertain to individuals’ access to and engagement in mental health treatment services (Lange et al., 2020). Assessing social determinants of health in the mental health treatment context is increasingly emphasized, but leading measures such as PRAPARE (National Association of Community Mental Health Centers, 2016) appear to focus predominantly on structural or practical barriers to treatment instead of sociocultural aspects (Lange et al., 2020; Sokol et al., 2019). Our review of the literature yielded measures available for specific sociocultural factors such as ethnic identity (i.e., American Identity Measure, (Schwartz et al., 2012); Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, (Roberts et al., 1999), discrimination (i.e., Everyday Discrimination Scale, (Williams et al., 1997); The Adolescent Discrimination Distress Index, (Fisher et al., 2000), acculturation (i.e., Societal Attitude Familial Environment – For Children, (Chavez et al., 1997); Acculturation, Habits, and Interests Multicultural Scale for Adolescents, (Unger et al., 2002), but did not return any measures that appear to be comprehensive of a wide array of sociocultural factors that would be relevant to all clients. Therefore, clinicians are encouraged to work with their clients to select a standardized sociocultural measure or two and then set and track individualized goals accordingly. This approach will individually tailor treatment to optimize treatment alliance, relevance and acceptability (Lewis et al., 2018; Tharinger et al., 2013).

Youth and Caregiver Involvement

Using STAY, clinicians can target ongoing engagement with the youth and their caregiver(s) as therapeutic alliance and service relevance and acceptability apply to both parties. Measures should be completed and reviewed by the youth and/or caregiver depending on youth age and presenting concerns. The youth and caregiver should both be involved in the decision-making process about when, whether, and how to adjust the treatment plan according to progress data collected and conversations about those data in session. As youth and their caregivers may disagree on target problems when treatment begins (Hawley & Weisz, 2003), and these discrepancies can predict caregiver engagement (Israel et al., 2006), the process of collecting youth- and caregiver-reported measures, discussing discrepancies, and reviewing progress together with the youth and caregiver to inform shared decision-making is an important therapeutic process.

Current research indicates that caregivers prefer to be involved in treatment, and while youth may prefer to meet mainly with the clinician alone, they still prefer that some information be shared with their caregiver (Langer et al., 2021). Progress data check ins and conversations as part of STAY offer an ideal mechanism for the caregiver, youth and clinician to collaboratively discuss progress and treatment planning even if most sessions are individual with the teen. Indeed, cultural factors may influence how REM caregivers conceptualize and report the symptoms and distress of their youth (Liang, Matheson, & Douglas, 2016). Yet, the literature regarding caregiver involvement in REM adolescent mental health treatment is very underdeveloped. Literature reviews on caregiver engagement in child and family mental health treatment sometimes include REM populations in the sample but do not specifically address REM populations (c.f., Haine-Schlagel & Walsch, 2005). Related work has examined factors that contribute to Latino family participation in general child mental health services (Kapke & Gerdes, 2016) and proposed a culturally infused treatment engagement model (Yasui et al., 2017), but we were unable to locate specific examinations of caregiver involvement in REM adolescent mental health treatment. STAY is designed specifically for REM youth and their parent(s) or caregiver(s) involved in treatment to advance research and practice in this area.

STAY Clinical Case Example

“Xavier,” a 15-year-old who identifies as a Black male, is attending his first session of outpatient mental health treatment in a community-based clinic in his neighborhood. Xavier is attending with his father, “Mr. Jackson,” and neither Xavier nor Mr. Jackson have prior experience receiving mental health services. Over the past three months, Xavier has been experiencing depressed mood and irritability. Xavier self-reports low energy and lack of interest in or energy for socializing with friends. He has increasing difficulty completing schoolwork and his most recent report shows a significant decline in grades. Xavier is also having trouble sleeping and has been staying up late at night and sleeping in late in the morning, Mr. Jackson has been increasingly concerned about his son and learned of this clinic from a family member.

This first clinical session is taking place after the intake process. The clinician, Ms. Taylor, focuses on introducing STAY by describing the process in plain words and ensuring Xavier and Mr. Jackson know what to expect related to measure collection and use. Ms. Taylor also emphasizes why collecting and reviewing youth-reported measures throughout treatment is important for shared decision-making and tracking progress toward personalized goals. Ms. Taylor has been a licensed clinician for 11 years and identifies as White, heterosexual, cisgender woman. She specializes in child and family treatment, has experience working with African-American/Black teens and their caregivers, and attends annual professional to continuously develop her cultural competence. The clinical interaction for the “Introduce” component is as follows:

Ms. Taylor: It’s important that the therapy you get here is actually working for you and helping you feel better. One of the ways we do that is by checking in with you about how you’re doing now and throughout therapy using some short surveys. They only take about 5 minutes to fill out and we can review your answers right away. Each time you come to see me, I’ll ask you to fill out one or two surveys about how you are feeling and how things are going for you. Then, we’ll look at the scores together and talk about how you’re doing to decide whether to keep therapy the same or change things to make it more useful for you. This is one way for us to make sure that we are getting your input and that therapy is working for you. What questions do you have so far?

Xavier: So, it’s like a quiz?

Ms. Taylor: Not quite. There are no right or wrong answers…it’s really about what you are feeling. This helps us keep track of what’s going well in therapy for you and what we might need to change up to help you feel better. The most important thing is that therapy is useful for you – and these scores help us decide what works best for you. I should also mention that these scores are just for us to use and are stored in your chart. No other clinicians or doctors you’ve seen before or might see in the future can see your chart unless you give permission for us to share it.

The first session also includes the “Collect” component, when Ms. Taylor explains the measurement tools in more detail and the youth is asked to complete them. In this case, Ms. Taylor uses three measures. One is a standardized depression symptom measure. Ms. Taylor presents explains that these type of questionnaires will help them all “check in on things that some teens with depression experience, like sadness, problems with sleep, low energy, and doing fun things you usually enjoy.” Ms. Taylor also explains that they can use the total scores and specific items to track progress over time. After showing a couple of options to Xavier and Mr. Jackson, they decide to use the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is a brief, standardized, validated depression measure for initial assessment and progress monitoring.

Another measure she uses is the Youth Top Problems (Weisz et al., 2011), which is an idiographic measure that allows Ms. Taylor, Xavier and Mr. Jackson to develop three top goals that they can complete each session, where 0 = “not at all” and 10 = “very, very much.” They have a conversation about therapy goals using the intake forms as a starting point. Xavier reports would like to have the energy to start socializing with friends again. Mr. Jackson reports he would like Xavier to turn in all his schoolwork on time to get his grades up. Ms. Taylor lists these two goals and Xavier and Mr. Jackson each provide initial ratings on them. The third goal is initially left blank until more information is gathered.

The third measure Ms. Taylor presented was the Cultural Acceptability of Treatment Survey – Version 2.0 (Leff et al., 2010). The CATS was chosen based on literature suggesting that REM clients prefer when issues of race and ethnicity are discussed in treatment and provide client-reported feedback to inform discussion of how and what to integrate into the treatment approach. After reviewing the whole measure, the three questions Xavier and Mr. Jackson chose to answer and select for individualized tracking over time are “How important is it to you that we discuss experiences of your racial and ethnic group in therapy?” (1 = Very Unimportant; 5 = Very Important), “How satisfied are you with how we talk about your experience of your racial/ethnic group (e.g., African-American/Black, Latina/o, Asian American) in therapy with our discussions of the experiences of your identified racial/ethnic group in therapy?” (1 = Very Dissatisfied; 5 = Very Satisfied); and “How satisfied are you with how we talk about experiences of discrimination and prejudices faced by your racial/ethnic group (e.g., African-American/Black, Latina/o, Asian American) in therapy?”. The first item would be collected in the first session, but the other two could be collected in sessions thereafter.

After explaining and collecting initial ratings on the three brief measures, Ms. Taylor shares the results of the surveys with Xavier and Mr. Jackson. The “Share” interaction occurs as follows:

Ms. Taylor: So, your PHQ-9 score today was a 19. This means you’re experiencing pretty high levels of depression, which is about what we expect when people start out in therapy. According to your PHQ-9 scores, you are having the most problems with sleep, appetite, feeling tired and trouble concentrating. Does that fit with how you’ve been feeling?

Xavier: Yeah, that is about right. But even though I didn’t feel like a failure that often, like on the form, I realized that, when I filled this out, that’s kind of a big issue for me. I just feel like I can’t do things right. Like, I let my family down all the time. Even being here, my dad has to take time off from work.

Mr. Jackson: I didn’t realize that you feel like that. Why would you think you were a failure?! This has just been a rough year, and you haven’t been yourself.

Ms. Taylor: It sounds like this year has been hard and its affected you in a lot of different ways. It also sounds like we’re learning some new information. This is one of the reasons it’s important we use the surveys as a starting point but they are never the full story. Even though something only happened “several days” in the past 2 weeks, it can still be a big problem that is bothering you a lot. Is this something we should make sure we’re working on in therapy? I’m wondering if we should add it to the goal list.

Mr. Jackson: Yes, this seems pretty important to address.

Xavier: Yeah, that would be okay. I don’t really know how therapy is going to help with this part but I guess we can try it out.

Ms. Taylor: Well, I have some ideas. First, I want to hear a little bit more about what’s causing you to feel this way and when it started. Then we can work together on some ways to help you feel more confident or successful, whatever we decide is the goal. Let’s also talk about your scores on the other question – you rated that it’s “important” to you that we discuss experiences of Black youth in therapy. Can you tell me more about that?

Xavier: Yeah, that question was kind of interesting because you know, being a Black male, that is something that really impacts me and my dad who always talks to me about it. It’s a lot especially right now because every day on the news it’s another situation getting out of hand against Black people. It just weighs on a person so much, you know?

Ms. Taylor: Absolutely. It sounds like this is a really important part of what we should check in about when we meet, not just experiences of Black males in general, and perhaps the Black community, but also your personal experiences, especially because it’s weighing on you so much.

Xavier: Yeah, I don’t really know how much it connects to me being here, like now, but I do feel kind of hopeless about it sometimes which doesn’t help my current situation.

Ms. Taylor: I hear you. Dealing with racism is part of your everyday life and is probably adding more stress on top of feeling depressed. Thank you so much for being open to sharing what is important to you and why you’re here. By setting goals that matter the most to you and picking out some surveys or questions to rate each time we meet we can have a clear way to see if what we’re doing together is working. How does that sound?

Together, Xavier, Ms. Taylor and Mr. Jackson agree on a third goal for the youth to track, “Feeling good about myself as a person at least once a day.” The clinician documents the PHQ-9 results in the youth’s record after the session, including brief notes that the youth and caregiver reported that feeling like a failure or letting others down is an important focus of therapy.

During sessions two and three, Xavier talk about his personal goals and aspirations in different life domains, and how his depression and experiences of racism in his community is getting in the way of feeling good about himself as a person, a friend, and family member. Xavier and Ms. Taylor create a list of positive thoughts and memories that they put in their phone to remind him what he’s good at, and how he is an important part of his family and friend circle when they are feeling really down.

At this fourth session, Xavier completes the PHQ-9, YTP and CATS questions. His symptoms are improving. After talking through the results, everyone understands that these scores do show how Xavier has really been feeling lately. While the PHQ-9 scores have improved and Xavier is feeling less depressed overall, he has made less progress on “Feeling good about myself as a person.” Ms. Taylor is now going to review the ratings to talk about progress and how therapy has been working so far, consistent with the “Share” component, as follows:

Ms. Taylor: How much improvement do you think we’ve made so far? Does it feel to you like we’re on the right track with what we’re working on together or that we need to do something differently?

Xavier: So far, it’s been OK. I am feeling a little better just talking about the things that are bothering me. The reminders in my phone are good to look at, but I still haven’t felt like hanging out with my friends and I’m sleeping through first period every day, so my dad isn’t too happy about that.

Ms. Taylor: I can tell from your ratings here that your sleep and energy are still low. I’m wondering if we should talk about changing some things we work on in our sessions.

Xavier: How do you mean?

Ms. Taylor: Well, we could focus a little more on your sleep routines to help you get a full night’s sleep and up in time for school. Or, we could also do something called “activity scheduling” where you basically schedule one way every day to make sure you do something fun. Sometimes these options can help us get our energy back. What ideas do you have?

Xavier: Well, I’m not too good with schedules and I might not do it and feel worse about myself. Maybe we could start with the sleep thing. But, I like how we’ve been talking so far and I like the phone reminders about my positive thoughts and memories.

Ms. Taylor: Okay, let’s keep the phone reminders and start work on the sleep thing then. We could put together a plan to start with that might help with your sleep, and we could use your phone to set reminders for bedtime, kind of “dos” and “don’ts” before bed that will help you sleep, and an alarm in the morning. And, we’ll keep touching base about how it’s going. How does that sound?

Implementing STAY

Effective implementation of STAY will likely be most successful in the context of several pertinent best practices in mental health treatment services. First and foremost, clinicians should receive ongoing professional development related to cultural competence, including implicit and explicit biases, positionality of the clinician and potential impact to the client’s experience of care and therapeutic relationship, and anti-racist approaches to treatment (Kodjo, 2009; FitzGerald & Hurst, 2017). Specific to culturally-relevant MBC, clinicians should be trained and supported (e.g., through ongoing, practice-specific peer consultation or supervision) to present, administer and discuss all measures in a culturally informed manner. Related, STAY will likely require initial training plus ongoing consultation, coaching, or supervision for clinicians with process evaluation for quality improvement whenever possible to optimize clinician cultural competence, skill, and client outcomes (Betancourt & Green, 2010). Finally, as is the case with MBC generally, STAY must be provided in conjunction with evidence-based, individualized, and culturally relevant treatment interventions.

Discussion

MBC is a person-centered approach to collect and use client-reported progress and outcomes to inform shared decision-making among the client and clinician. Applications of MBC with REM clients (adults or children) has not been explicitly studied, but it has been associated with increased engagement in services and can be applied to a wide range of diagnostic categories, using a wide range of client-reported measures. Moreover, MBC has the opportunity to target perceptual barriers to treatment such as alliance and perceived relevance by ensuring treatment targets are individualized and developed through shared partnership with the youth and their family.

Consistent with MBC, we put forth a culturally-modified, MBC approach, STAY, to improve treatment engagement among REM youth and families. STAY emphasizes youth- and family- centered decision-making about treatment based on collaborative monitoring of patient-reported outcomes. Cultural modifications to MBC included in STAY with the goal of optimizing ongoing engagement among REM youth include: 1) adding a separate component to focus on the initial introduction of and rationale for MBC, 2) including an idiographic measure and 3) adding a sociocultural measure. While these modifications could be considered as part of traditional clinical practice of MBC, they are further emphasized and detailed in STAY to address some of the most salient barriers to ongoing treatment engagement for REM youth. Assessment practices, especially when conducted in a collaborative, transparent manner with youth and families, have been emphasized in prior research to improve treatment engagement (Becker, Boustani, Gellatly, & Chorpita, 2017; Tharinger et al., 2013)

We propose that clinicians treating REM youth can incorporate MBC to 1) address perceptual barriers to treatment starting in the first encounter; 2) explicitly assess and plan to address, when relevant, sociocultural factors that may influence youth mental health strengths and needs; and 3) improve care quality for REM youth by adopting this personalized, client-centered, data-driven approach to guiding treatment. Ultimately, if the STAY model effectively improves treatment retention and engagement, we would anticipate that a higher “dosage” of treatment could be received which would, in turn, improve client outcomes including symptomatic improvement and goal attainment (Cordaro et al., 2012; Labouliere et al., 2017; Shirk et al., 2008). Comprehensive treatment retention measurement may include treatment attendance, session participation, attitudinal engagement, and successful treatment completion or continuation (Lindsey et al., 2013). Admittedly, there are numerous other mechanisms of treatment relevance, engagement and completion beyond effective, collaborative use of patient-reported outcome measures. As has been pointed out recently, MBC must complement other aspects of evidence-based practice, including using evidence-based interventions and sound clinical judgment (Lustbader & Borer, 2020).

Limitations

The STAY model should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. First, STAY is not inclusive of the wide array of engagement interventions or treatment modifications relevant to improving REM youth treatment engagement. These include addressing stigma through mental health literacy, ethnic matching of clients and clinicians, or focusing on multicultural competency training for therapists. Rather, it is designed to enhance aspects of MBC specifically to optimize REM youth treatment engagement.

Additionally, the MBC modifications outlined here are preliminary based on our review of the literature, clinical experiences and input from a small group of stakeholders with relevant expertise. STAY is yet to be further refined and then validated by input from REM youth, caregivers, and clinicians, a current and future area of research among this team. For instance, our team carefully considered inclusion of a working alliance measure, but opted to not include such a measure as a recommended component of STAY at this time for two reasons. First, as three measures are already recommended for progress monitoring in each session, the addition of a working alliance measure could negatively impact the feasibility of implementation. Relatedly, the use of a working alliance measure in addition to a sociocultural, standardized and individualized measure, specifically for REM adolescents, is not well known. Among ethnic minoritized clients, including issues regarding race and ethnicity in care has been associated with greater treatment satisfaction (Meyer & Zane, 2013), so inclusion of a sociocultural measure in STAY should promote greater treatment relevance, acceptability and satisfaction for REM clients. However, this is an empirical question that we have yet to explore.

Certainly, extant literature emphasizes the importance of adult and youth client perceptions of alliance and monitoring client-reported alliance and related experiences in treatment (Bachelor, 2011; Horvath & Symonds, 1991; Ormhaug, Shirk & Wentzenl-Larsen, 2015). However, the direction of relation between alliance scores and outcome is not well known (Castonguay et al 2006) and studies examining how alliance measures and clinical conversations operate specifically within the context of REM adolescent mental health treatment are greatly needed. It has been initially proposed that working alliance may need to be reconceptualized in a cross-cultural counseling context (Shonfeld-Ringel, 2001).

Should clinicians prefer to include an alliance measure, they could alternate administration with one of the other measures (to reduce client burden) or select a standardized measure or measurement system that includes an alliance measure or set of items, such as the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery or The Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS). The current MBC evidence base with youth most commonly represents proprietary measurement systems that include standardized symptom and/or functioning outcome measures and some measure of relational engagement or satisfaction with services (Hansen, Howe, & Ronan, 2015; Riemer et al., 2012; Timimi et al., 2012).

Finally, an important clarification is that including a sociocultural measure as part of MBC practice for REM youth does not take the place of culturally-relevant diagnosis and assessment in the initial phase of treatment. Turner and Mills (2016) provide and excellent review of conducting diagnosis and assessment in a culturally-relevant manner which includes understanding cultural expressions of symptoms, how race and culture influence assessment processes and results, cultural competence on the part of the clinician to have awareness of their own cultural beliefs/biases and that of their clients, and familiarity with the reliability and validity of standardized measures among REM client samples (Turner & Mills, 2016). In fact, including sociocultural measures during the initial assessment and diagnosis phase could lay an early foundation to 1) assess and discuss sociocultural factors related to treatment with clients and 2) select standardized measures and/or individualized goals to track progress in these areas throughout treatment.

Current and Future Research

To date, our procedures followed Barrera & Castro’s (2006) early stages of adaptation development, including information gathering via literature review to inform MBC adjustments most likely to address why REM youth are at risk of early treatment termination. Our preliminary modification design to MBC as outlined in this paper will be followed by current and future research to test this model with service recipients and providers to inform continued refinement. Moreover, future clinical research informed by clinical innovations and expertise from consumers and providers is greatly needed to better understand the role of assessing and addressing sociocultural factors (i.e., oppression, racism, discrimination, language, citizenship, social influencers of health such as education, economic stability, built environment, health and health care, social and community context) that may influence REM youth mental health strengths, needs, and treatment goals.

Impact Statement:

Youth who identify as racial or ethnic minorities are more likely to leave mental health treatment early than youth who identify as White. This paper describes a way that therapists can address this by building a positive relationship with the youth and their primary caregiver and making sure that therapy is relevant and personalized to the issues they are most concerned about. The practice we describe involves the youth, caregiver, and therapist working together to select a few personalized ways to track the youth’s progress and then using progress updates the youth and caregiver report over time to make decisions together about next steps in treatment.

Acknowledgement:

We are grateful to Dr. Michael Awad for his assistance with references and formatting.

Footnotes

We use the term “client” when describing MBC As Usual because the Collect, Share, Act framework was developed for an adult, veteran population. However, when MBC is implemented with child and adolescent populations, as is the case with STAY, both the child or adolescent and their parent are involved as “clients” in collecting, reviewing, discussing, and making decisions on the basis of progress data.

References

- Aggarwal NK, Pieh MC, Dixon L, Guarnaccia P, Alegria M, & Lewis-Fernandez R (2016). Clinician descriptions of communication strategies to improve treatment engagement by racial/ethnic minorities in mental health services: a systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(2), 198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, & Ortega AN (2002). Mental health care for Latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53(12), 1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, & Keefe K (2011). Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, & Kaiser DM (2008). The experience of stigma among Black mental health consumers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(3), 874–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PG, Nastasi BK, & Leff SS (2017). Rationale for the cultural construction of school mental health programming. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 5(3), 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth M, Guerra D, & Kordowicz M (2019). Individualised or standardised outcome measures: A co-habitation? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(4), 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelor A (2013). Clients’ and therapists’ views of the therapeutic alliance: Similarities, differences and relationship to therapy outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(2), 118–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, & Graziano PA (2013). Barriers to success in parent training for young children with developmental delay: The role of cumulative risk. Behavior Modification, 37(3), 356–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon WM, & McKay MM (2005). Are barriers to service and parental preference match for service related to urban child mental health service use? Families in Society, 86(1), 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, & Castro FG (2006). A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Boustani M, Gellatly R, & Chorpita BF (2018). Forty years of engagement research in children’s mental health services: Multidimensional measurement and practice elements. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, & Chorpita BF (2015). The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, & Green AR (2010). Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Academic Medicine, 85(4), 583–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, & Ananeh-Firempong O (2003). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health Care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293–302. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.4.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Kelley SD, Breda C, de Andrade AR, & Riemer M (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- sychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16, 252–260.Brookman-Frazee L, Haine RA, Gabayan EN, & Garland AF (2008). Predicting frequency of treatment visits in community-based youth psychotherapy. Psychological Services, 5(2), 126–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Basil S, & Fernandez Y (2013). What Latina mothers think of evidence-based parenting practices: A qualitative study of treatment acceptability. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(3), 362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, & Battle CL (2003). Guess who’s coming to therapy? Getting comfortable with conversations about race and ethnicity in psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(3), 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JE, Carrillo VA, Perez HR, Salas-Lopez D, Natale-Pereira A, & Byron AT (2011). Defining and targeting health care access barriers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(2), 562–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay LG, Constantino MJ, & Holtforth MG (2006). The working alliance: Where are we and where should we go? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(3), 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez DV, Moran VR, Reid SL, & Lopez M (1997). Acculturative stress in children: A modification of the SAFE scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 19(1), 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, & Collins KS (2014). Managing and adapting practice: A system for applying evidence in clinical care with youth and families. Clinical Social Work Journal, 42(2), 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2002). Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(2), 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, & Martinez ME (2014). Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-March 2014. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Connors EH, Douglas S, Jensen-Doss A, Landes SJ, Lewis CC, McLeod BD, Stanick C, & Lyon AR (2020). What gets measured gets done: How mental health agencies can leverage measurement-based care for better patient care, clinician supports, and organizational goals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaro M, Tubman JG, Wagner EF, & Morris SL (2012). Treatment process predictors of program completion or dropout among minority adolescents enrolled in a brief motivational substance abuse intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 21(1), 51–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Wen H, & Druss BG (2011). Racial/ethnic differences in treatment for substance use disorders among US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(12), 1265–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakof GA, Henderson CE, Rowe CL, Boustani M, Greenbaum PE, Wang W, Hawes S, Linares C, & Liddle HA (2015). A randomized clinical trial of family therapy in juvenile drug court. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(2), 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan AM, Boon AE, de Jong JT, & Vermeiren RR (2018). A review of mental health treatment dropout by ethnic minority youth. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(1), 3–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong K (2017). Effectiveness of progress monitoring: A meta-analysis. The 48th International Annual Meeting for the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Toronto, CA, [Google Scholar]

- Dollar KM, Kirchner JE, DePhilippis D, Ritchie MJ, McGee-Vincent P, Burden JL, & Resnick SG (2019). Steps for implementing measurement-based care: Implementation planning guide development and use in quality improvement. Psychological Services, 17(3), 247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowrick C, Leydon GM, McBride A, Howe A, Burgess H, Clarke P, Maisey S, & Kendrick T (2009). Patients’ and doctors’ views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: Qualitative study. BMJ, 338(b663). doi: 10.1136/bmj.b663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen SV, Dickey B, & Sederer LI (2000). A self-report symptom and problem rating scale to increase inpatients’ involvement in treatment. Psychiatric Services, 51(3), 349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, & Rollnick S (2012). Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, & Fenton RE (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(6), 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald C, & Hurst S (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker SM, Turner CW, Waldron HB, Brody JL, & Ozechowski TJ (2008). Ethnic background, therapeutic alliance, and treatment retention in functional family therapy with adolescents who abuse substances. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, Pyne JM, Smith GR, Schoenbaum M, & Harbin HT (2017). A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatric Services, 68(2), 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Bibi F, Millar H, & Holland A (2017). The role of cultural factors in engagement and change in Multisystemic Therapy (MST). Journal of Family Therapy, 39(2), 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Frey WH (2019). Less than half of US children under 15 are white, census shows. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/less-than-half-of-us-children-under-15-are-white-census-shows/

- Fuertes JN, Mueller LN, Chauhan RV, Walker JA, & Ladany N (2002). An investigation of European American therapists’ approach to counseling African American clients. The Counseling Psychologist, 30(5), 763–788. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, & Weisz JR (2002). When youth mental health care stops: Therapeutic relationship problems and other reasons for ending youth outpatient treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Kruse M, & Aarons GA (2003). Clinicians and outcome measurement: What’s the use? The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 30(4), 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, & Chae D (2009). Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiologic Reviews, 31(1), 130–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Paksarian D, Rudolph KE, & Merikangas KR (2018). Prevalence of mental disorder and service use by immigrant generation and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(4), 280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glied S, & Cuellar AE (2003). Trends and issues in child and adolescent mental health. Health Affairs, 22(5), 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondek D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Fink E, Deighton J, & Wolpert M (2016). Feedback from outcome measures and treatment effectiveness, treatment efficiency, and collaborative practice: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 325–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Weersing VR, Warnick EM, Scahill LD, & Woolston JL (2011). Predictors of treatment attrition among an outpatient clinic sample of youths with clinically significant anxiety. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(5), 356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, & McKay MM (2010). Engaging families into child mental health treatment: updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry/Journal de l’Académie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent, 19(3): 182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Swartz HA, & Zuckoff A (2008). Enhancing interpersonal psychotherapy for mothers and expectant mothers on low incomes: Adaptations and additions. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 38(1), 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Zuckoff A, Swartz H, Bledsoe SE, & Geibel S (2007). Engaging women who are depressed and economically disadvantaged in mental health treatment. Social Work, 52(4), 295–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, Hu CQ, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Correll CU, Lai KY, Feng L, & Geng Y (2015). Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(10), 1004–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Spoth R, & Redmond C (2003). The effects of incentives and research requirements on participation rates for a community-based preventive intervention research study. Journal of Primary Prevention, (24), 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, & Walsh NE (2015). A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B, Howe A, Sutton P, & Ronan K (2015). Impact of client feedback on clinical outcomes for young people using public mental health services: A pilot study. Psychiatry Research, 229(1–2), 617–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EJ, Lambert MJ, Vermeersch DA, Slade KL, & Tuttle KC (2004). The Therapeutic Effects of Providing Patient Progress Information to Therapists and Patients. Psychotherapy Research, 14(3), 308–327. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, & Weisz JR (2003). Child, parent and therapist (dis) agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist’s dilemma and its implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, & Symonds BD (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(2), 139. [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, & Polo AJ (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, & Mash EJ (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 29–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM (2010). Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(5), 629–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel P, Thomsen PH, Langeveld JH, & Stormark KM (2007). Parent–youth discrepancy in the assessment and treatment of youth in usual clinical care setting: Consequences to parent involvement. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16(2), 138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Smith AM, Becker-Haimes EM, Ringle VM, Walsh LM, Nanda M, Walsh SL, Maxwell CA, & Lyon AR (2018). Individualized progress measures are more acceptable to clinicians than standardized measures: Results of a national survey. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(3), 392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E, Mellor D, & Brann P (2008). Differences in dropout between diagnoses in child and adolescent mental health services. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(4), 515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA (2008). Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77(4), 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapke TL, & Gerdes AC (2016). Latino family participation in youth mental health services: Treatment retention, engagement, and response. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(4), 329–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver M, Shirk S, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Crisp H, Gudmundsen G, & McMakin D (2008). Relationship processes in youth psychotherapy: Measuring alliance, alliance-building behaviors, and client involvement. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2000). Perceived barriers to treatment participation and treatment acceptability among antisocial children and their families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9(2), 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2005). Treatment outcomes, common factors, and continued neglect of mechanisms of change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12(2), 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, & Crowley M (1997). Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from child therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(3), 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Stolar MJ, & Marciano PL (1995). Risk factors for dropping out of treatment among White and Black families. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(4), 402–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Wassell G (2000). Predictors of barriers to treatment and therapeutic change in outpatient therapy for antisocial children and their families. Mental Health Services Research, 2(1), 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Whitley MK (2003). Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiresuk TJ, Stelmachers ZT, & Schultz SK (1982). Quality assurance and goal attainment scaling. Professional Psychology, 13(1), 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Klingaman EA, Medoff DR, Park SG, Brown CH, Fang L, Dixon LB, Hack SM, Tapscott SL, Walsh MB, & Kreyenbuhl JA (2015). Consumer satisfaction with psychiatric services: The role of shared decision making and the therapeutic relationship. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(3), 242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]