Abstract

Nutrient import by APC-type transporters is predicted to have a high energy demand because it depends on the plasma membrane proton gradient established by the ATP-driven proton pump Pma1. We show that Pma1 is indeed a major energy consumer and its activity is tightly linked to the cellular ATP levels. The low Pma1 activity caused by acute loss of respiration resulted in a dramatic drop in cytoplasmic pH, which triggered the downregulation of the major proton importers, the APC transporters. This regulatory system is likely the reason for the observed rapid endocytosis of APC transporters during many environmental stresses. Furthermore, we show the importance of respiration in providing ATP to maintain a strong proton gradient for efficient nutrient uptake.

Graphical Abstract

Our study highlights the importance of respiration for Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains commonly used for cell biological studies. We show that fermentation does not compensate for the lack of mitochondrial ATP production. As a consequence, loss of respiration reduces the plasma membrane proton gradient, which slows both nutrient import and growth.

Introduction

The Amino Acid Polyamine Organocation (APC) protein superfamily represents a major group of transporters that are responsible for the import of amino acids and other small molecules from the extracellular medium. Members of this superfamily are found in all organisms, from archaea to mammals (reviewed in (Hundal and Taylor, 2009)). The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae expresses ~26 different APC transporters. Cells have developed complex regulatory systems that determine the surface pool of each nutrient transporter. Yeast relies mainly on post-translational regulation of APC transporters to rapidly respond to frequent changes in environmental nutrient availability. For example, high extracellular nutrient concentration causes rapid endocytosis and degradation of the corresponding transporter, whereas the presence of low nutrients stabilizes the APC proteins. This substrate-dependent regulation of APC transporters aims at maintaining a constant flux of nutrients into the cell. Studies of the APC transporter Fur4 (uracil importer) identified a protein-intrinsic mechanism that regulates turnover depending on the concentration of uracil (Keener and Babst, 2013). An N-terminal domain of Fur4 is exposed upon uracil binding, allowing the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 to access and ubiquitinate key lysine residues. Ubiquitinated Fur4 is endocytosed and degraded by the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway (Galan et al., 1996; Seron et al., 1999). The same conformation sensing mechanism is also responsible for quality control of Fur4. It seems that any conformation that does not represent the Fur4 ground-state (properly folded and not substrate bound) is targeted for degradation (Babst, 2014; Keener and Babst, 2013). Based on studies of other APC transporters it appears that the Fur4 system may be representative of the regulation of many members of this nutrient importer family (Ghaddar et al., 2014; Gournas et al., 2017).

An additional layer of APC transporter regulation is provided by alpha-arrestins, also referred to as ART (Arrestin Related Trafficking) adaptor proteins (Lin et al., 2008). These proteins bind to a specific set of transporters and aid in the recruitment of Rsp5, thereby increasing the rate of ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. The activity of the alpha-arrestins is often regulated by phosphorylation, which allows yeast to increase or decrease the turnover rate of the corresponding transporters (Becuwe and Leon, 2014; Becuwe et al., 2012; Crapeau et al., 2014; Hovsepian et al., 2017; Llopis-Torregrosa et al., 2016).

Most yeast APC transporters are proton-nutrient symporters that require the proton gradient across the plasma membrane for their import function. This gradient is maintained by the P2-type H+-ATPase Pma1. Pma1 is one of the most abundant proteins in yeast and represents a major ATP consumer (Cyert and Philpott, 2013; Perlin et al., 1989). It is therefore not surprising that Pma1 activity is tightly controlled by the metabolic state of the cell (Goossens et al., 2000). Pma1 is an essential protein because it is required not only in nutrient uptake but also in maintaining ion homeostasis and cytoplasmic pH (Serrano et al., 1986).

APC transporters are linked in several ways to the metabolism of the cell. Both the nutrients they import and the ATP required to facilitate import (via Pma1) have important consequences for the cells’ metabolism. In this study, we sought to better understand the relationship between transporters and energy metabolism in yeast strains commonly used for trafficking studies.

Results

Reduced energy levels trigger rapid endocytosis of APC transporters.

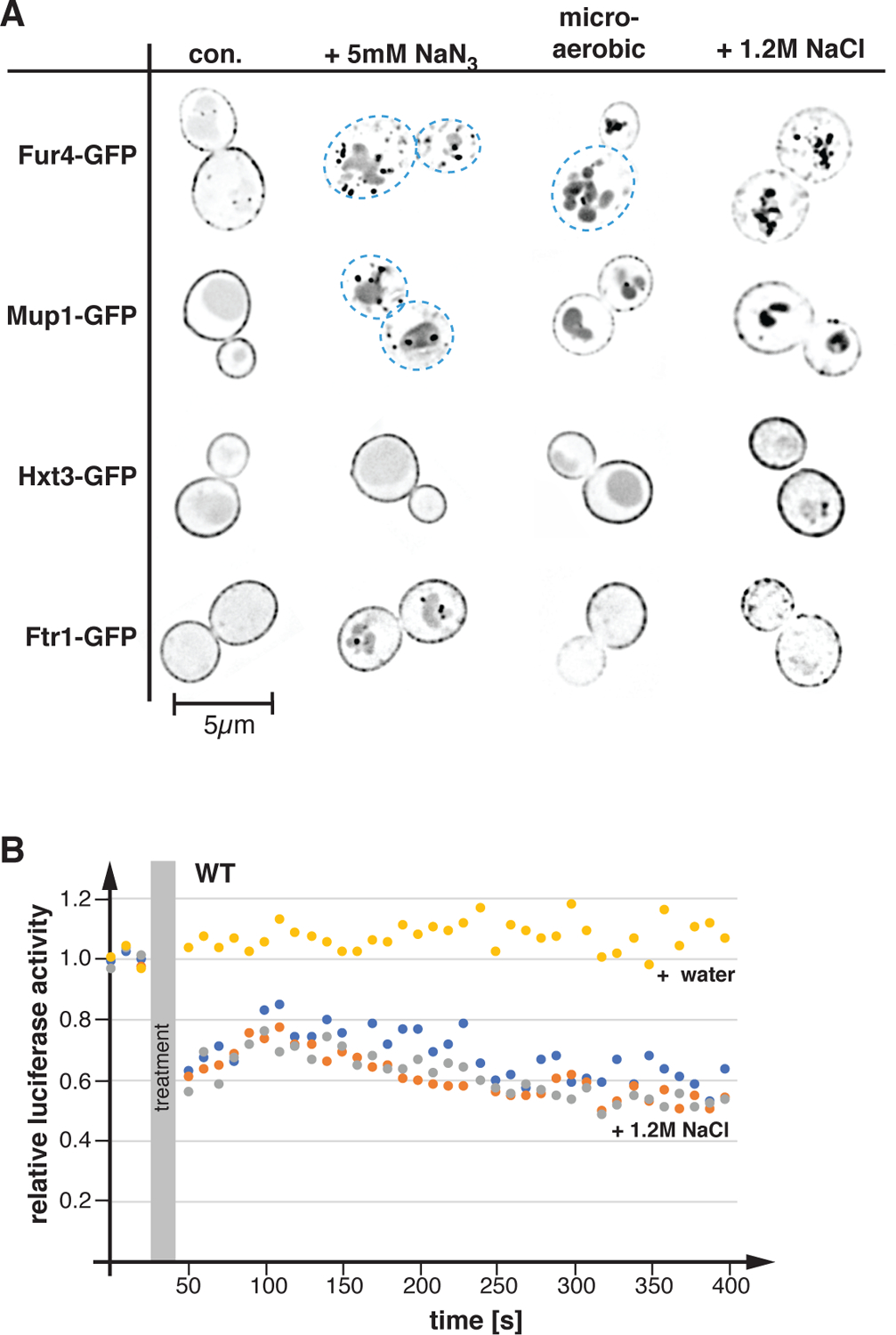

Trafficking studies of APC transporters identified a surprisingly large number of treatments or stress conditions that cause the degradation of these transporters (Bultynck et al., 2006; Crapeau et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Lang et al., 2014; Volland et al., 1994). In fact, almost any change in environmental conditions seems to impact stability of APC transporters, even changes that have no obvious effect on nutrient homeostasis. For example, addition of 1.2M salt to a growing yeast culture causes an acute turnover of the APC transporters Fur4 (imports uracil) and Mup1 (imports methionine). Fluorescence microscopy showed that 1h after the salt addition, a large portion of Fur4-GFP and Mup1-GFP localized to the vacuolar lumen (Figure 1A), suggesting rapid endocytosis and subsequent degradation of these proteins (GFP is a very stable protein and thus accumulates in the vacuole). In contrast, we observed only minor effects on the stability of other types of nutrient transporters, such as the glucose transporter Hxt3, and the iron transporter Ftr1 (Figure 1A). It should be noted that these observations were not consistent with a previous mass spectrometry study, which indicated that salt stress induces a broad endocytic response that affected many cell surface proteins, including Hxt3 and Ftr1 (Szopinska et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Stress conditions affect ATP levels and the localization of APC transporters. A) Yeast strains were grown in SDcom, SDcom-ura or SDcom-leu-met medium to mid-log phase, treated for 1h as indicated and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (con.: control before treatment). The pictures show one optical section from the middle of the cell. The pictures were inverted for better visualization of the GFP signal (GFP signal is shown in black). Blue dashed line indicates the cell outline where surface expression of the GFP-tagged protein is low. The following strains were used: Fur4-GFP (SEY6210 pJK19), Mup1-GFP (SEY6210 pPL4146), Hxt3-GFP (DLY050), Ftr1-GFP (CBY118). B) The cellular ATP levels of BY4741 pMB522 (WT) grown in SDcom-ura medium were determined by a luciferase assay. The values of the luciferase activity were standardized relative to starting conditions. For the treatment, NaCl (5M stock solution, 1.2M final concentration; orange, grey and blue data points) or equal volume water (yellow data point) was added.

A common theme among several stress treatments is that they are expected to either impair energy metabolism or cause increased ATP consumption, suggesting that low energy levels might trigger the degradation of APC transporters. To test if salt stress affected cellular ATP levels, we performed in vivo luciferase activity assays. Light production by luciferase is ATP dependent and thus measuring emitted photons provides a readout of changes in cellular ATP levels. We observed that the addition of 1.2M NaCl resulted in a drop of ATP levels, whereas adding the same volume of water (control) did not affect cellular energy levels (Figure 1B). Although it is not obvious how the presence of high salt affects ATP levels, the high energy demand of increased ion pump activity and the production of osmolytes might explain the ATP drop. Therefore, reduced energy levels might be the culprit that caused the APC transporter degradation during stress conditions.

To further test the link between APC transporter stability and cellular energy levels, we treated exponentially growing wild-type cells (SEY6210) expressing the different GFP-tagged transporters for 1h with NaN3 (blocks oxidative phosphorylation) or oxygen depletion. Both treatments impair respiration, which is expected to only partially reduce energy levels of yeast growing at high glucose concentrations (growth medium contains 2% glucose). At high glucose concentrations, yeast has been reported to rely mainly on fermentation for ATP production (Crabtree effect; (De Deken, 1966; Johnston and Kim, 2005). Both treatments (azide, microaerobic) caused increased endocytosis and vacuolar delivery of Fur4-GFP and Mup1-GFP (Figure 1A), suggesting that loss of respiration does impact the stability of APC transporters. In contrast, the surface expression of Hxt3-GFP showed only a slight increase in vacuolar localization after oxygen depletion, whereas Ftr1-GFP exhibited some intracellular localization in presence of azide (Figure 1A). Together, the data suggested that in comparison with other nutrient importers, APC transporters respond particularly sensitively to reduced energy levels.

What is the link between ATP levels and APC transporters? In contrast to other nutrient transporters such as Hxt3 and Ftr1, APC-type transporters use the proton gradient across the plasma membrane to drive import of molecules. Yeast expresses ~26 different APC transporters, which represent major consumers of the proton gradient. To avoid acidification of the cytoplasm it is essential to maintain the balance between the proton influx mediated by APC transporters and the proton efflux by Pma1, the ATP-driven proton pump at the plasma membrane (Morsomme et al., 2000). Pma1 is the most abundant cell surface protein and is predicted to be one of the largest ATP consumers in yeast (Cyert and Philpott, 2013; Perlin et al., 1989). A drop in ATP production is expected to lower Pma1 activity and as a consequence, the cell might remove APC transporters to restore proton flux balance.

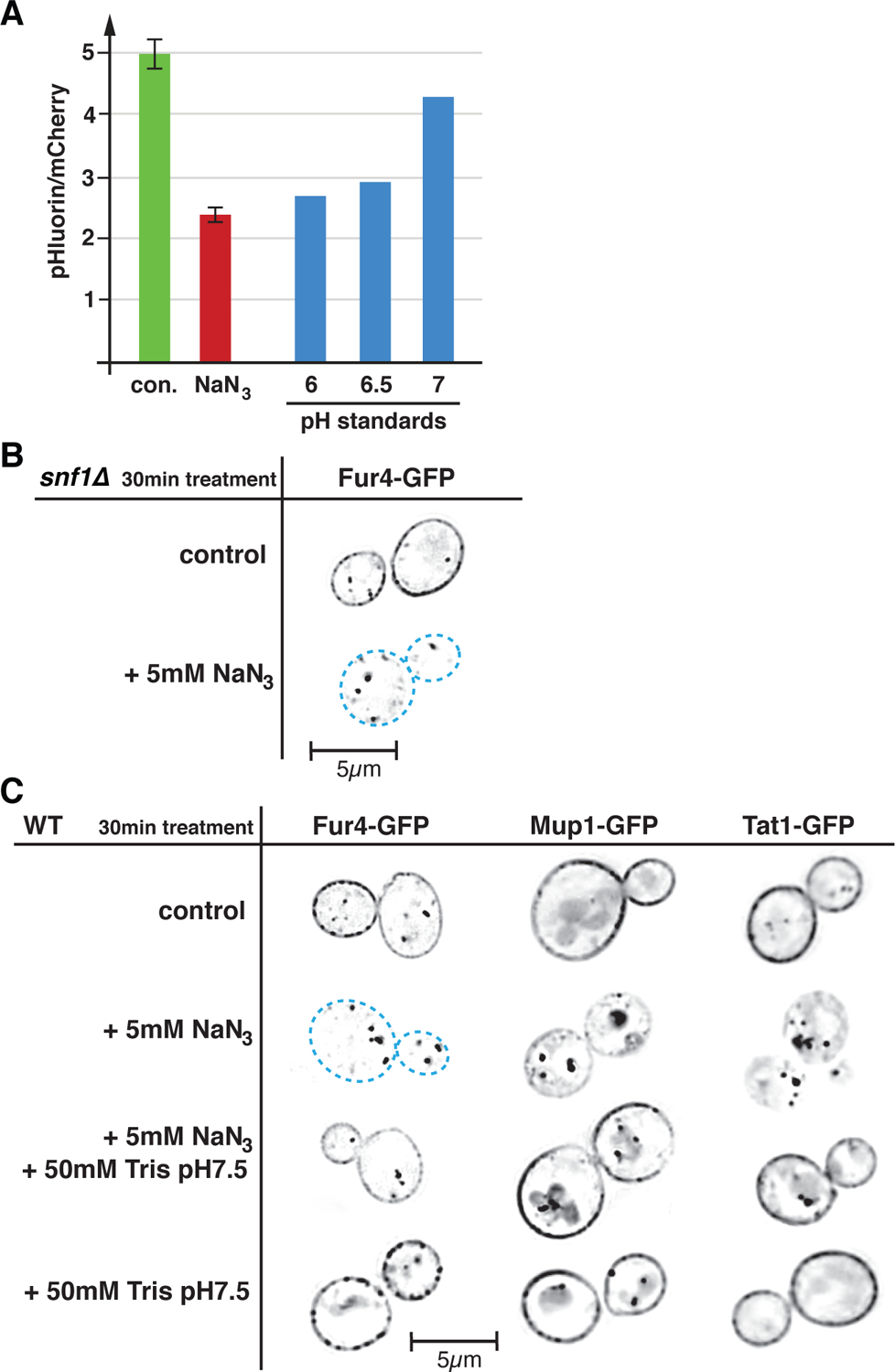

Based on the model described above we would predict that NaN3 treatment causes an acute drop in cytoplasmic pH (reduced ATP production causes reduced Pma1 activity, and thus cytoplasmic accumulation of protons). To test this prediction, we determined changes in the cytoplasmic pH of yeast by measuring the ratio of pHluorin (pH sensitive GFP variant) to mCherry (not pH sensitive) fluorescence before and after addition of 5mM NaN3. The data indicated a rapid drop of the cytoplasmic pH from >7 to <6 after inhibition of respiration (Figure 2A). A similar drop in cytoplasmic pH has been previously reported in energy-depleted cells (treated with 2-deoxyglucose and antimycin A; (Munder et al., 2016)), suggesting that acute loss of respiration represents a severe energy crisis.

Figure 2.

Loss of respiration causes low cytoplasmic pH which triggers APC transporter downregulation. A) Azide induced changes in cytoplasmic pH were determined by measuring the ratio of pHluorin to mCherry fluorescence of cells expressing a pHluorin-mCherry fusion protein (SEY6210 pMB517). The green column shows the ratio before treatment (con.), the red column shows the ratio 2min after addition of 5mM NaN3. Using the same culture, the pH standards were determined by resuspending the cells in 1M buffer solution (pH6 MES, pH6.5 MES, pH7 Tris) in presence of 5mM NaN3 and 5mM NaF (blocks ATP production and thus collapses all proton gradients). Each data point represents the median of 150,000 cells (analyzed by flow cytometry). The control and azide treated samples were measured in triplicates. B) Fluorescence microscopy of snf1Δ (AMY20 pJK19) expressing Fur4-GFP (optical section through the middle of the cell). The cells were analyzed after 30min of azide treatment. Black represents GFP signal, dashed blue lines mark the outlines of the cells with no Fur4-GFP surface signal. C) Wild type cells expressing GFP-tagged APC transporters (SEY6210 pJK19, SEY6210 pPL4146, QAY1055) were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy as described in B.

Low cytoplasmic pH is involved in azide-induced downregulation.

An obvious candidate that could be involved in the regulation of APC-type nutrient transporters is AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a highly conserved energy homeostasis sensor that is activated by many stress conditions affecting cellular ATP levels (Kayikci and Nielsen, 2015). AMPK is known to regulate the function of alpha-arrestins, adaptors that aid in the downregulation of certain nutrient transporters (O’Donnell and Schmidt, 2019). Furthermore, AMPK was shown to affect eisosomes, the storage compartment of many APC transporters (Moharir et al., 2018). Therefore, we investigated how deletion of the kinase subunit Snf1 of the hetero-trimeric AMPK complex would affect Fur4 turnover during acute loss of respiration. We found that a snf1Δ strain maintained the ability to rapidly degrade Fur4-GFP upon addition of azide (Figure 2B), indicating that AMPK is not required for the observed downregulation of Fur4 during acute loss of respiration.

The in Figure 2A observed rapid drop in cytoplasmic pH upon NaN3 addition might serve as a trigger for the endocytosis of APC transporters. To test this idea, we treated Fur4-GFP expressing cells with both 5mM NaN3 and 50mM Tris pH7.5. The addition of Tris pH7.5 alone did not affect the stability of the APC transporters (Figure 2B) but it increased the pH of the growth medium from 4 to 6.7, thereby minimizing the possible cytoplasmic acidification. The results showed that Tris addition indeed prevented most of the Fur4 endocytosis associated with loss of respiration (Figure 2B), suggesting a regulatory role for cytoplasmic acidification. Analogues to Fur4, two other APC transporters, Mup1 and Tat1 (imports hydrophobic amino acids), also exhibited pH dependent downregulation during azide treatment. However, in case of Mup1 and Tat1 the addition of Tris buffer was not able to completely block the endocytic response, indicating the presence of additional mechanisms that regulate energy-dependent surface expression of APC transporters.

Energy production of lab strains.

The finding that blocking respiration has strong effects, both on APC transporter stability and cytoplasmic pH, was unexpected since the literature highlights the fact that at glucose concentrations commonly used in labs (2%), yeast relies strongly on fermentation for the synthesis of ATP (De Deken, 1966; Johnston and Kim, 2005). Oxidative phosphorylation is suppressed under high-glucose conditions and only de-repressed when glucose is depleted (diauxic shift; (Galdieri et al., 2010)). Although the literature agrees on this general regulation, the extent to which glucose suppresses respiration varies in different studies. The findings of metabolic studies are often difficult to generalize, because of the use of different yeast strains, growth conditions and methods to determine changes in the metabolic state. Therefore, we decided to analyze the metabolic behavior of lab strains and growth conditions we commonly used for our cell biological studies.

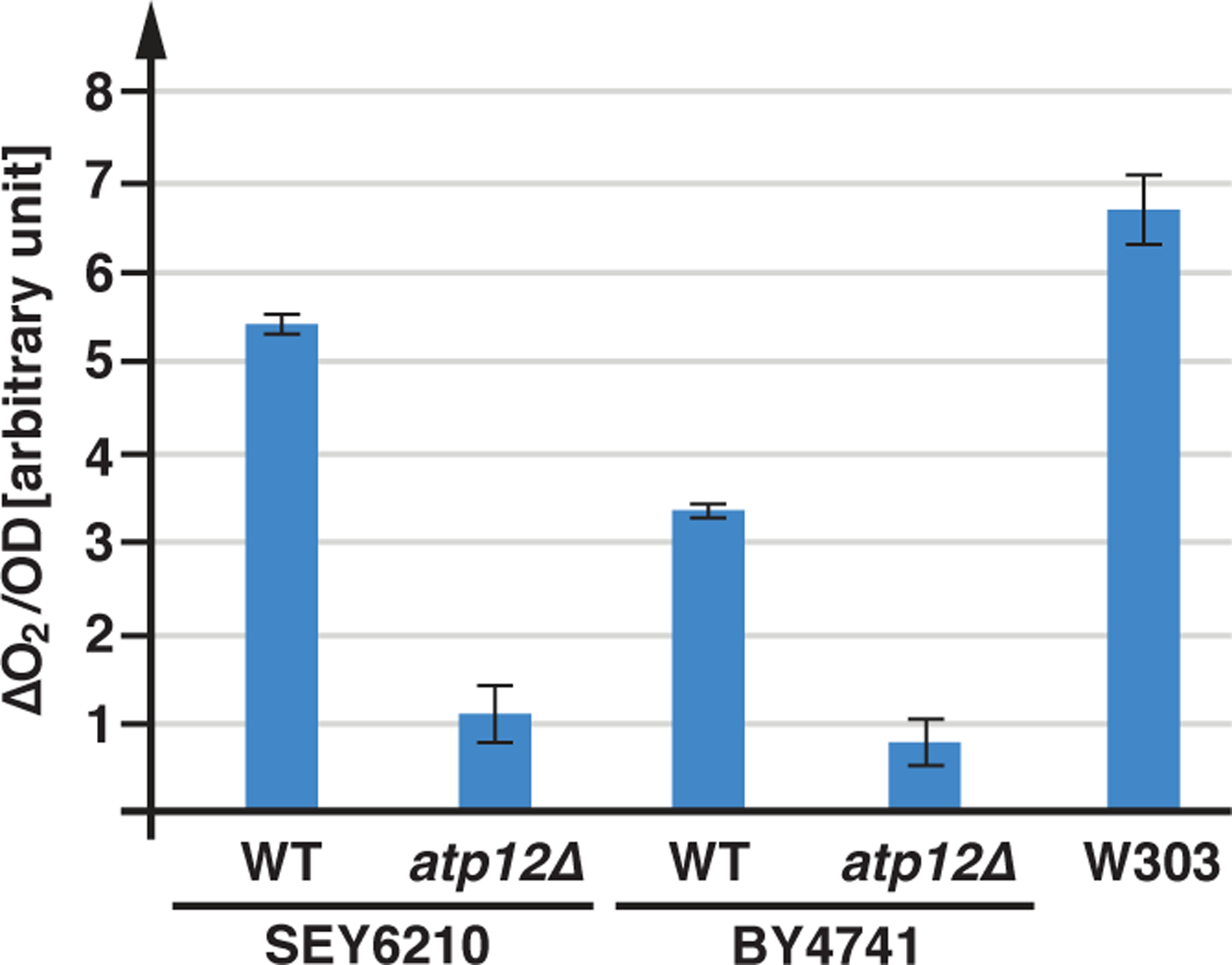

We determined the oxygen consumption of the wild-type strains SEY6210, BY4741 and W303 in rich medium containing 2% glucose (YPD medium). The cells were grown to mid-log phase and the oxygen consumption was measured at the same growth conditions using a Clark electrode (the data were standardized by cell density). The data indicated that all three strains respired, but at different rates. The respiration of SEY6210 and W303 was comparable whereas BY4741 exhibited approximately half the rate of the oxygen consumption (Figure 3), a reduction in respiration that could not be explained by growth rates (all three wild type strains grow very similar in YPD). BY4741 is known to have a mutation in the gene encoding the Hap1 transcription factor, which regulates the expression of electron transport chain components, thus explaining the observed reduced respiration rate (Gaisne et al., 1999). As a control, we determined the oxygen consumption rate of a SEY6210 and a BY4741 strain deleted for ATP12, a gene encoding a chaperone essential for the assembly of the mitochondrial FOF1 ATP-synthase. These mutant strains exhibited an ~80% reduction in respiration, indicating the majority of oxygen consumption by the wild-type yeast strains was linked to mitochondrial ATP production (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Respiration of lab strains. Wild-type and atp12Δ (AMY36, YJL180C) strains were grown in YPD to a density of OD600=0.7–1.0 and oxygen consumption was measured using a Clark electrode. The data were standardized by the cell density (OD). The graphs show the average and standard deviation of 3 measurements (based on t-test analysis, all discussed differences are statistically relevant with p<0.05).

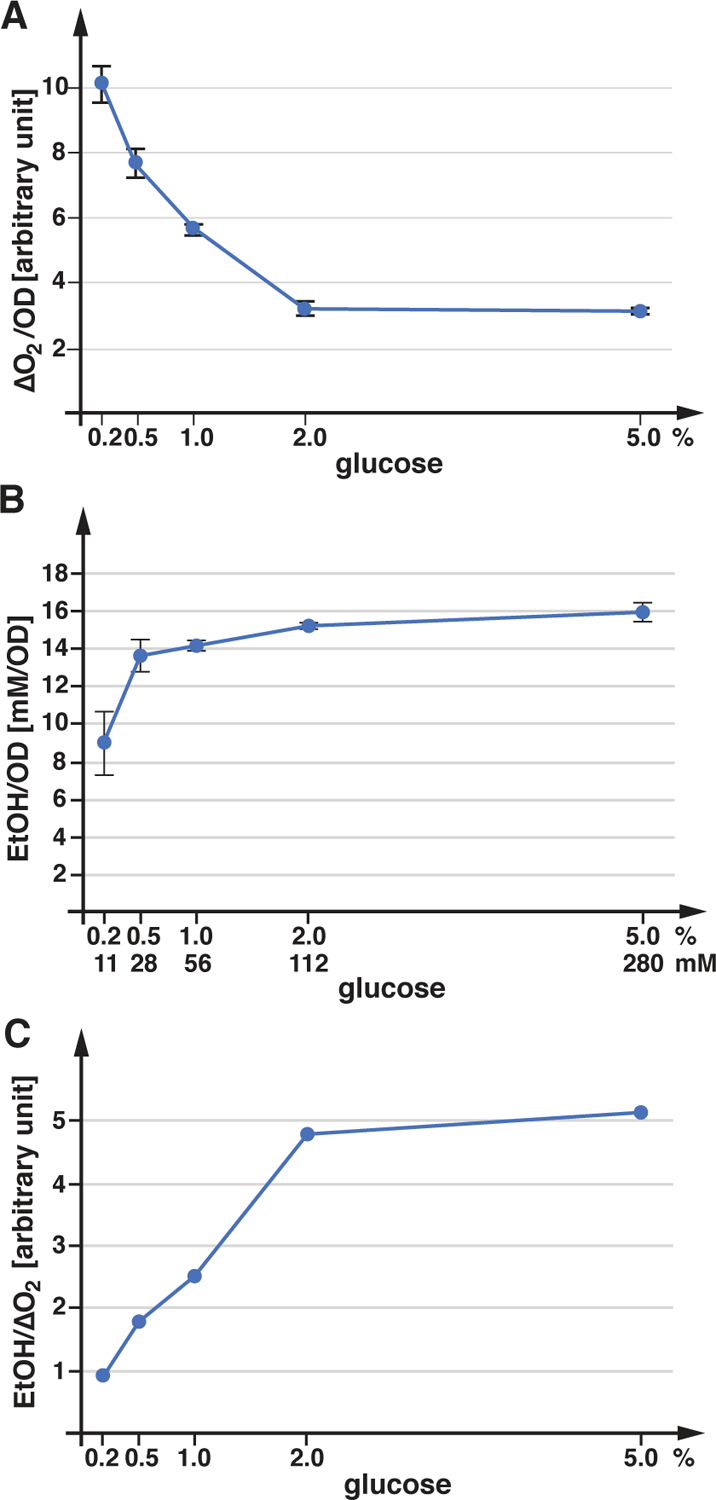

In the next set of experiments, we determined the oxygen consumption of SEY6210 as a function of the glucose concentration (synthetic complete, SDcom medium). As expected, the data showed a strong increase in oxygen consumption at low glucose concentration (0.2%) compared to high glucose conditions (>2%; ~3-fold induction; Figure 4A). It should be noted that at the time the cultures were used for the measurements some of the glucose was already consumed and thus the effective glucose concentration of the samples was at least 0.1% lower than indicated (based on the growth curve of yeast in presence of 0.2% glucose). The de-repression of the oxidative phosphorylation (diauxic shift) is predicted to occur at glucose concentrations below 0.2% (Otterstedt et al., 2004). However, our data did not fit to a sharp transition point but indicated a much more gradual adjustment of respiration rates to glucose concentrations. Furthermore, above ~2% glucose, oxygen consumption plateaus at a minimal activity of ~30% relative to the low glucose sample and this activity does not further diminish at higher glucose levels (Figure 4A). This result suggested that the glucose metabolism of SEY6210 is saturated above 2% glucose and never shows complete suppression of respiration.

Figure 4.

Energy metabolism of SEY6210. The graphs in A and B show the average and standard deviation of 3 measurements. A) SEY6210 was grown in SDcom containing the indicated glucose concentrations (concentration of the starting growth medium) and oxygen consumption was determined. B) SEY6210 was grown in SDcom in presence of various glucose concentrations. The ethanol concentrations present in the growth medium was quantified by GC-MS and standardized by the cell density. C) Ratio of ethanol concentration to oxygen consumption, using the data sets from A and B.

After demonstrating that our lab yeast strains may be respiring more than previously appreciated, we were interested in determining ethanol production as a readout for the energy production by fermentation. We measured by mass spectrometry the ethanol concentration of SEY6210 cultures grown to mid-log phase (OD600nm=1.0) in presence of different glucose concentrations. The data indicated that fermentation rates are close to saturation at a glucose concentration of 0.5% and only the 0.2% sample showed a substantial drop in ethanol production (~half of maximal; Figure 4B). Compared to the oxygen consumption rates, the rates of ethanol production showed an inverse correlation to the glucose concentration, resulting in a saturation curve of the fermentation/respiration ratio that plateaued at >2% glucose (Figure 4C).

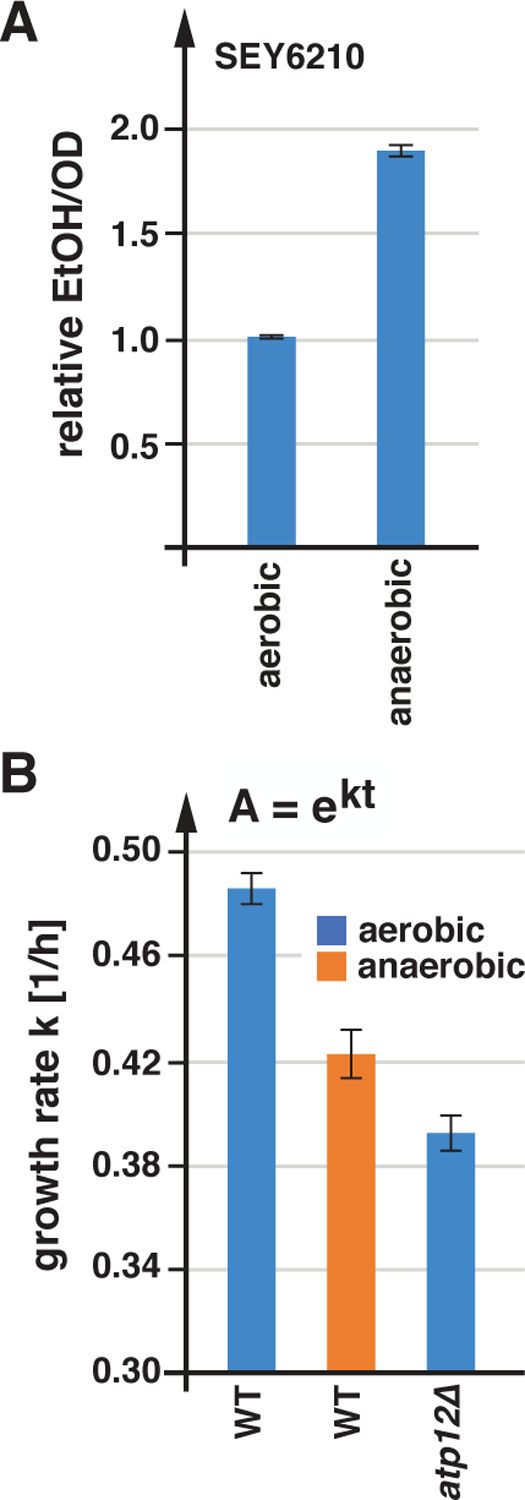

To estimate the contribution of respiration to the energy production of yeast, we compared the ethanol levels of cultures grown anaerobically relative to that of aerobic cultures. We observed that in presence of 2% glucose, ethanol production doubled in anaerobic conditions (Figure 5A). Since anaerobic growth rates are only slightly lower than growth rates under aerobic conditions (Figure 5B), the data indicated that even at glucose-saturation, aerobic cultures produce close to 50% of their energy by respiration. At lower glucose concentrations, the contribution of respiration to the energy production of SEY6210 is even higher (Figure 4A).

Figure 5.

Anaerobically grown cells show increased fermentation and decreased growth rates. A) Ethanol concentrations of SEY6210 grown in SDcom either aerobically or anaerobically were measured by GC-MS. The data were standardized to the cell density and represented relative to the measurements of the aerobically grown cells (n=3; standard deviation). B) Growth rates of SEY6210 strains growing in SDcom medium either aerobically or anaerobically. The data represent the average and standard deviation of the growth rates of 3 cultures.

In summary, the ATP production of aerobically grown SEY6210 depends strongly on respiration and the strain is not able to rapidly upregulate fermentation to compensate for an acute block in respiration, which explains the azide-induced acidification of the cytoplasm. In addition, a strain lacking the FOF1 ATPase (atp12Δ) or wild type growing anaerobically exhibited a reduction in growth rates (Figure 5B), suggesting that even after adaptation, fermentation was not able to fully compensate for the lack of respiration.

Pma1 is a major energy consumer.

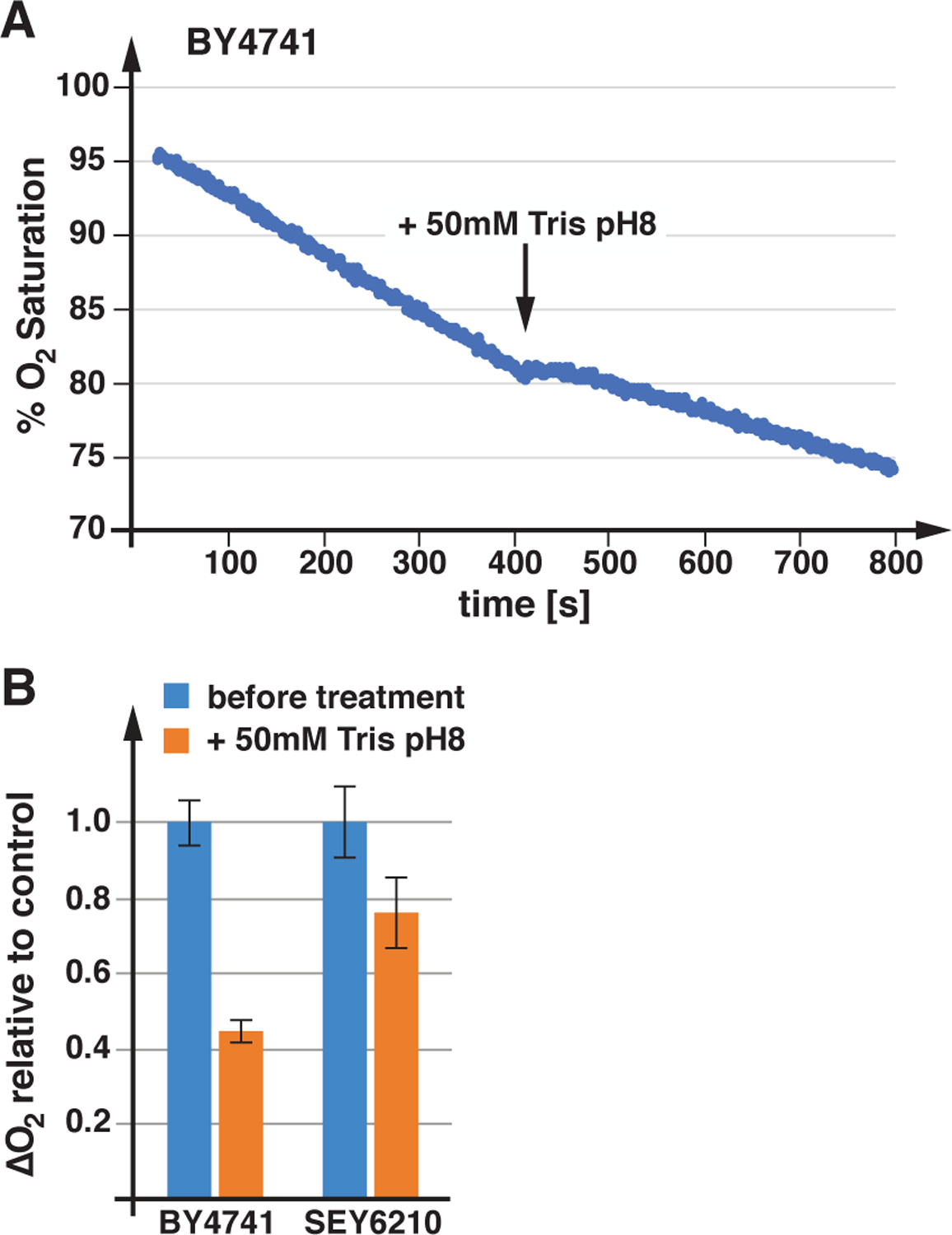

One cellular activity that has been proposed to be energy intensive is nutrient import by the APC transporter–Pma1 system (based on rough estimates of proton flux; (Cyert and Philpott, 2013; Perlin et al., 1989)). Because Pma1 is essential and specific inhibitors have not been identified, direct measurements of the impact this ATPase has on the energy balance of yeast are not available. However, it is possible to dramatically reduce Pma1 activity by raising the extracellular pH from ~4 (medium acidified by growing yeast) to 7.5 by the addition of 50mM Tris pH8. This Tris treatment collapses the plasma membrane proton gradient (Appadurai et al., 2020) and thus is expected to reduce proton flux. Consistent with this prediction, BY4741 cells decreased oxygen consumption by 55% and SEY6210 by 25% after Tris treatment (Figure 6). The observed reduction in respiration supported the claim that Pma1 is a major energy consumer in yeast. The more dramatic response of BY4741 to alkaline stress is likely a consequence of the reduced respiratory rate of this strain. Since respiration rates of BY4741 are half of that of SEY6210 (Figure 3), the absolute drop in oxygen consumption after Tris treatment is similar in both strains. Together, the data highlighted the link between the plasma membrane proton gradient and mitochondrial ATP production.

Figure 6.

Loss of plasma membrane proton gradient lowers respiration rates. A) Drop in oxygen saturation of the growth medium containing wild type (BY4741), before and after Tris treatment. B) The bar graph indicates the average and standard deviation of three oxygen consumption measurements performed before and after Tris pH8 addition (as shown in A).

Loss of respiration reduces the proton gradient.

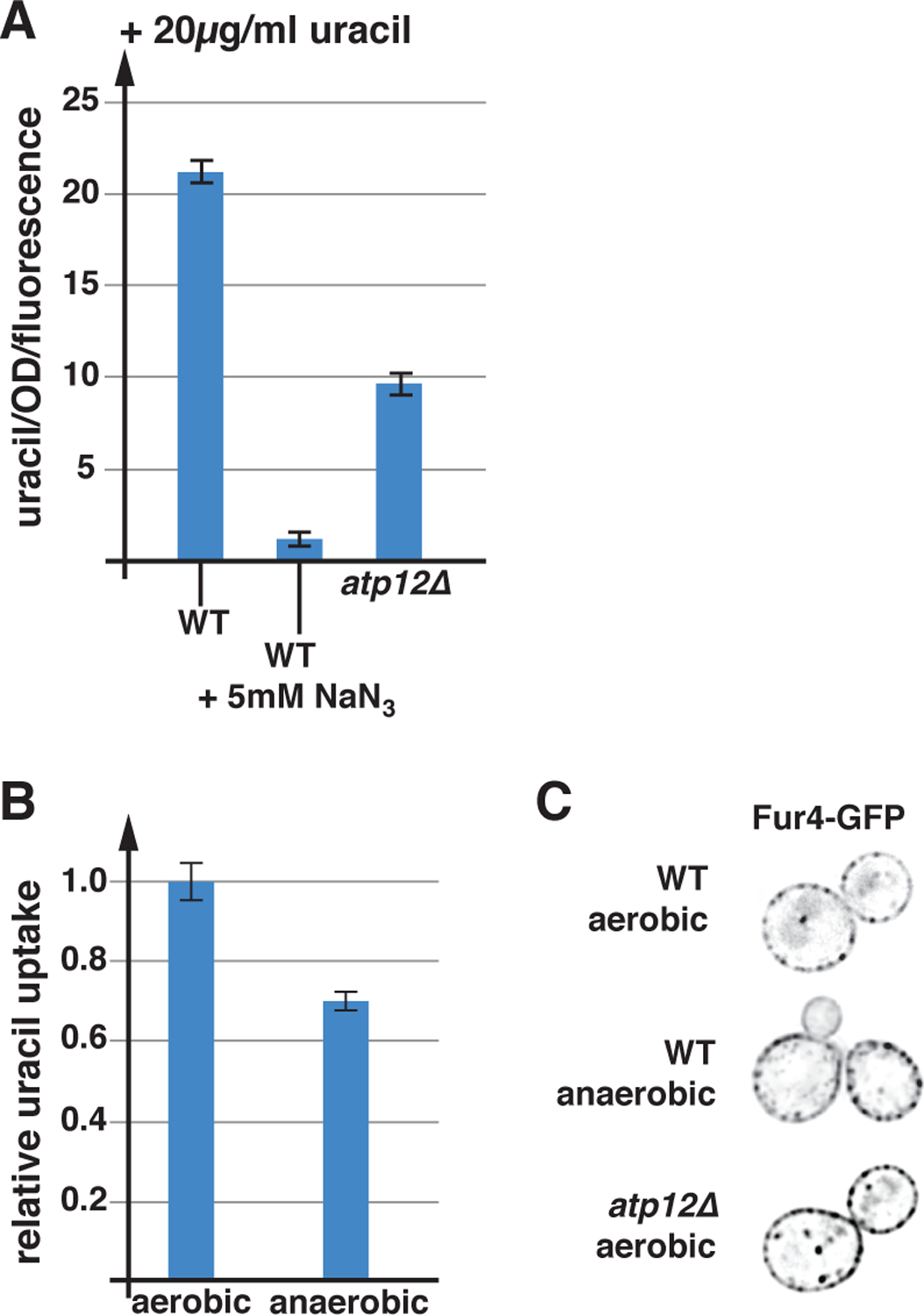

Since maintaining the plasma membrane proton gradient is energy intensive, we expected that changes in ATP production should impact the strength of the proton gradient. The kinetics of uracil import by the APC-transporter Fur4 is dependent on the uracil concentration in the growth medium, the number of Fur4 transporters and the strength of proton gradient. Therefore, by keeping the concentration of uracil and Fur4 constant we were able to use uracil import as a readout for the strength of the plasma membrane proton gradient in different yeast strains and growth conditions. For these experiments we grew the yeast strains in uracil-free medium to mid-logarithmic growth phase, added 20μg/ml uracil for 10min and after washing with ice-cold water the cells were extracted with methanol at 50°C which was injected into the HPLC system for analysis. We measured uracil import in strains expressing a plasmid-encoded Fur4(ΔN)-GFP, an N-terminally truncated form of Fur4 that is not ubiquitinated and thus is expected to maintain similar expression levels in the different strains (Keener and Babst, 2013). In addition, we quantified the expression levels of Fur4(ΔN)-GFP by flow cytometry and used the average fluorescence intensity to standardize the uracil import data. It should be noted that the strains also express the genomically encoded FUR4 gene and thus the measured import activity is the sum of both transporters, Fur4 and Fur4(ΔN)-GFP. However, SEY6210 without the fur4(ΔN)-GFP plasmid exhibited ~10-fold lower uracil import activity (data not shown) and therefore we ignored the contribution of the genomically encoded Fur4.

We found that in SEY6210 expressing Fur4(ΔN)-GFP, inhibiting ATP production by the addition of NaN3 5 min before the addition of uracil, dramatically impaired uracil uptake (Figure 7A), suggesting that the proton gradient across the plasma membrane collapses rapidly after losing respiration. This result is consistent with the drop in cytoplasmic pH we observed after azide treatment (Figure 2A). Together, the data suggested that Pma1 activity is severely inhibited by the acute loss of respiration. Blocking mitochondrial ATP synthesis by deleting ATP12 resulted only in a ~50% drop in uracil uptake (Figure 7A), indicating that over time cells adapt to the loss of oxidative phosphorylation and are able to partially restore the proton gradient. However, the regulatory system that governs energy metabolism and Pma1 function seems to be unable to fully compensate for the loss of mitochondrial respiration (e.g. by upregulating fermentation). This statement is further supported by the finding that anaerobic growth reduces uracil import kinetics (−30%; Figure 7B), suggesting that fermentation alone is not sufficient to maintain the proton gradient at full strength. This difference in the strength of the proton gradient between aerobically and anaerobically grown cells is not reflected in the pH of the growth medium, since both growth conditions acidified the medium to the same low pH of 3.9.

Figure 7.

Respiration plays an important role in nutrient import. A) For the uracil uptake assays the strains were grown in SDcom-ura medium. The following strains were used for these experiments: WT (SEY6210 pJK88), atp12Δ (AMY36 pJK88) (n=3). B) Relative uracil uptake of wild-type (SEY6210 pJK88) grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions (n=3). C) Fluorescence microscopy of yeast strains grown in SDcom-ura expressing Fur4-GFP (single cross section). The imaged strains are: WT (SEY6210 pJK19), atp12Δ (AMY36 pJK19).

The data in Figure 7A highlight the difference in nutrient uptake between a strain that acutely lost respiration (azide) and a strain that has adapted to the lack of respiration (atp12Δ). During the acute phase, yeast might dramatically lower Pma1 activity to preserve energy for the adaption process, resulting in the observed drop in proton gradient (Figure 7A), drop in cytoplasmic pH (Figure 2A) and the downregulation of nutrient transporters (Figure 1A). However, the atp12Δ strain or anaerobically growing wild type that has fully adapted to the lack of respiration showed only a partial loss of the proton gradient (Figures 7A and 7B) and no increased turnover of the APC transporter Fur4 (Figure 7C). Nevertheless, the lower efficiency of nutrient uptake is likely the reason for the reduced growth rate of these strains (SEY6210: anaerobic or atp12Δ; Figure 5B).

In summary, the uracil import assays highlighted the close connection between cellular energy levels and the strength of the plasma membrane proton gradient. The proton gradient on the other hand is the driving force for the import of many nutrients, in particular amino acids that can be limiting in a fast-growing organism such as yeast.

Discussion

We started this study with the goal to better understand the downregulation of APC transporters observed during different stress conditions. A key finding from our experiments was that an acute drop in cellular energy levels triggered the rapid endocytosis of Fur4, Mup1 and Tat1, three representatives of the 26 member APC-transporter superfamily. This endocytic response is specific for these proteins and other types of nutrient transporters are not affected (e.g. Hxt3, Ftr1). A likely reason for this regulation is the high ATP demand of the plasma membrane proton pump Pma1, which maintains the proton gradient that drives nutrient import by the APC transporters. Balancing proton import and export is essential to prevent acidification of the cytoplasm. A drop in ATP levels reduces proton export by Pma1 and as a result, cells reduce proton import by downregulating APC transporters.

One of the conditions that caused APC transporter degradation was the addition of azide, a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration. Azide addition resulted in a dramatic drop of the cytoplasmic pH, indicating that loss of respiration impaired proton efflux by Pma1. Interestingly, the low cytoplasmic pH was important for the subsequent downregulation of the APC transporters, suggesting that acidification served as a signal to trigger transporter endocytosis. There is no obvious candidate for the protein/molecule that senses cytoplasmic acidification. Since the pH change is rather dramatic (~1,5 units), it is likely that many cellular activities are affected by the low pH, which could include ubiquitination systems that regulate APC transporter stability.

The dramatic response to azide treatment (cytoplasmic acidification, transporter downregulation) prompted us to investigate the role of respiration in the ATP production of our commonly used lab strain, SEY6210. Many past studies highlight the fact that at high glucose concentrations used in our growth medium (2% glucose), S. cerevisiae relies mainly on glycolysis/fermentation for ATP production (e.g. (Fendt and Sauer, 2010)). This aerobic fermentation is also referred to as the “Crabtree effect” (a variation on the Warburg effect), which describes an energy metabolism that even in presence of oxygen shunts most of the imported glucose to ethanol production and suppresses respiration. However, strains used for metabolic studies often differ significantly from the strains used in cell biology and even among those strains, genetic diversity has complicated the view of yeast metabolism (as shown for the respiratory defective strain BY4741; Figure 3). Based on the azide response data we considered two possibilities: either respiration is a major producer of ATP, or respiration is a minor contributor to ATP production, which would indicate that Pma1 responds very sensitively to the small drop in energy levels. We found that SEY6210, the yeast strain we commonly used for our trafficking studies, exhibited robust respiration with rates that provided at least 50% of ATP during aerobic growth. The remaining ATP was the product of fermentation, which, consistent with the Crabtree effect, converted most of the imported glucose to ethanol (in yeast, fermentation is ~9x less efficient in ATP production per glucose than respiration; (Pfeiffer and Morley, 2014)). Together, our data suggested that the acute loss of respiration has a major impact on the energy levels of the cell, explaining the strong endocytic response we observed after azide treatment.

In contrast to acute azide treatment, anaerobically growing cells adapted to the loss of respiration showed no increased turnover of APC transporters, indicating that these cells were able to maintain proton flux homeostasis with APC transporters at the cell surface. This adaptation was possible by doubling fermentation rates and by lowering the proton gradient across the plasma membrane. As a consequence, anaerobically growing cells showed reduced efficiency of nutrient uptake which most likely is the reason for the observed slower growth rate of these cells. Similarly, aerobically grown atp12Δ cells that lacked a functioning ATP synthase exhibited a reduction both in the proton gradient and growth rate. Together, the data suggested that fermentation was not able to fully compensate for the loss of respiratory ATP production.

In summary, our study highlights the close relationship between energy metabolism, Pma1 activity and nutrient import by APC transporters (Figure 8). In our yeast strain, only respiratory growth is able to provide the energy required for optimal nutrient import by APC transporters. It is not obvious why the regulatory systems in yeast, such as the AMPK-Mig1 system, are not able to upregulate fermentation to a level that would compensate for the lack of respiration. It is possible that lab yeast strains adjusted their metabolic regulation to an aerobic lifestyle which are the growth conditions used in a laboratory setting. It is also possible that Pma1 activity is sensitive to mitochondrial ATP production because of proximity of the mitochondria to the plasma membrane, which could allow for high local ATP flux. This functional connection between mitochondria and Pma1 has been observed before in a genome-wide analysis of factors that influence cytoplasmic pH (Orij et al., 2012). This study also supported our observation that cytoplasmic acidification serves as a signal that might regulate many cellular activities, including APC transporter trafficking.

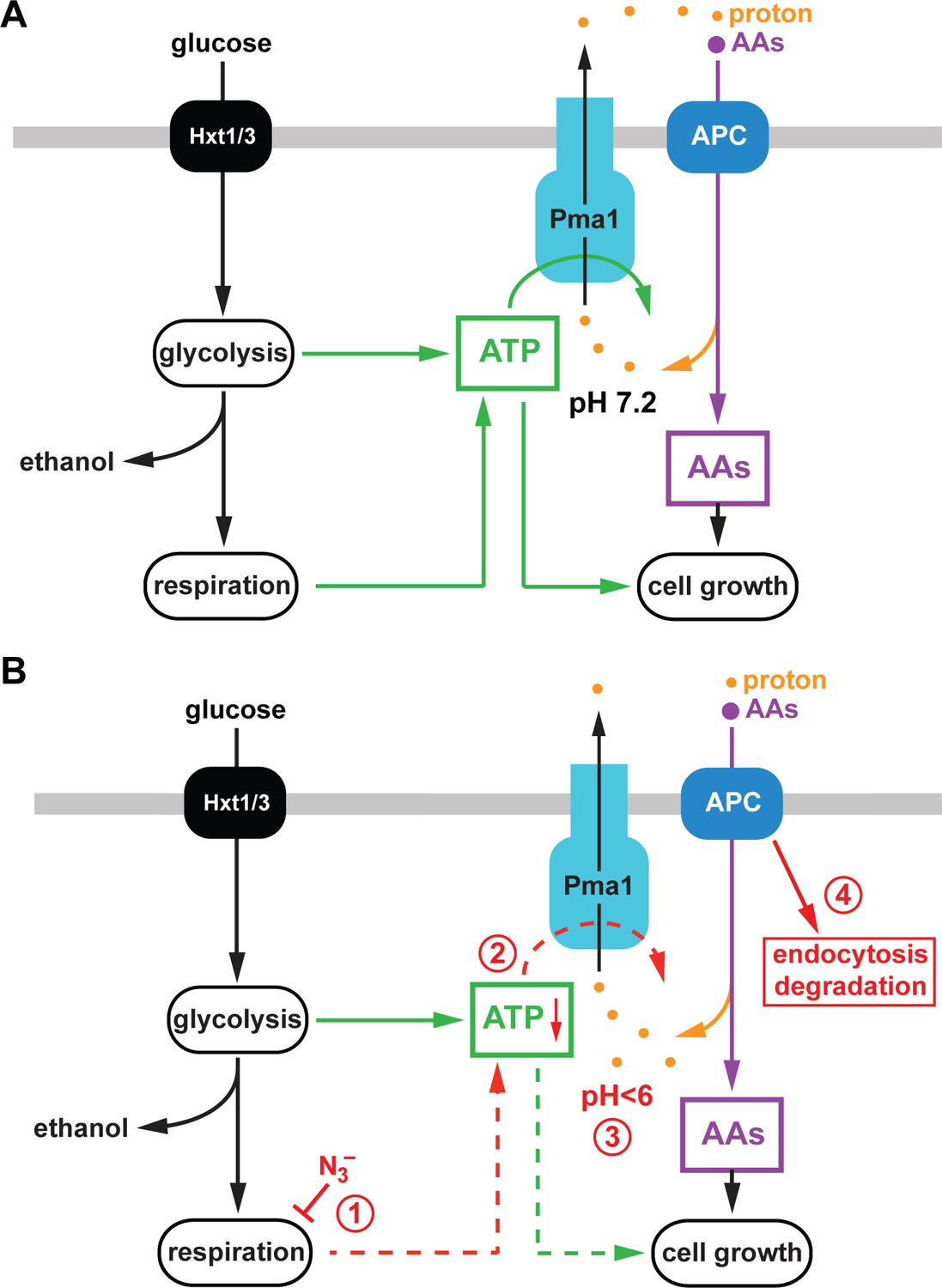

Figure 8.

Model of the link between the APC transporter system and the metabolic state of yeast. A) The APC transporters require a strong plasma membrane proton gradient for their function, which is maintained by the ATP-dependent proton pump Pma1. ATP required for Pma1 activity is synthesized by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (respiration) and glycolysis/fermentation. High levels of amino acids (AAs) and ATP support the fast growth rates of yeast. B) The presence of azide blocks respiration (1), which causes in a drop of ATP levels (2). The resulting decrease of Pma1 activity lowers the cytoplasmic pH (3) which serves as a signal to induce endocytosis and degradation of APC transporters (4).

Materials and Methods

S. cerevisiae strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Genomic deletion and tagging were made by homologous recombination as described previously (Longtine et al., 1998). The resulting insertions or gene replacements were confirmed by PCR. The yeast strains were grown either in rich YPD (yeast extract, peptone, and 2% dextrose) or Synthetic Dextrose (SD) medium (yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose) either with amino acids (SDcom). Depending on plasmids present in the strains the SDcom medium lacked certain nutrients (-uracil, -leucine). For microscopy experiments with Mup1-GFP expressing strains the SDcom medium lacked methionine. To induce expression of constructs containing the CUP1–1 promoter 0.1 mM cupric sulfate was added to the medium.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains | Descriptive Name | Genotype or Description | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | WT | MATα leu2–3,112 ura3–52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2–801 suc2-Δ9 GAL | (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| AMY20 | snf1Δ | SEY6210, SNF1::TRP1 | This study |

| AMY36 | atp12Δ | SEY6210, ATP12::KANMX6 | This study |

| BY4741 | WT | MATa leu2–3112, ura3–52, his3-Δ200 | (Winston et al., 1995) |

| W303 | WT | MATa leu2–3112, trp1–1 can1–100 ura3–1 ade2–1 his3–11,15 [phi+] | (Voth et al., 2005) |

| CBY118 | FTR1-GFP | SEY6210, FTR1-GFP, HISMX | (Jones et al., 2012) |

| QAY1055 | TAT1-GFP | BY4741, TAT1-GFP, KANMX | Mara Duncan |

| DLY050 | HXT3-GFP | BY4742, HXT3-GFP, KANMX | (Lang et al., 2014) |

| YJL180C | atp12Δ | BY4741, ATP12::KANMX | Δ collection strain, Open Biosystems |

| Plasmids | |||

| pJK19 | P(CUP1)-FUR4-GFP | URA3 (pRS416) P(CUP1)-FUR4-GFP | (Keener and Babst, 2013) |

| PJK88 | P(SNF7)- fur4(ΔN)-GFP | URA3 (pRS416) P(SNF7)-fur4(Δ60)-GFP | This study |

| pPL4146 | P(CUP1)-MUP1-GFP |

LEU2 (pRS315) P(CUP1)-MUP1-GFP |

(Stringer and Piper, 2011) |

| pMB517 | P(CUP1)-sepHluorin-mCherry | URA3 (pRS416) P(CUP1)- sepHluorin-mCherry | (Moharir et al., 2018) |

| pMB522 | mCherry-LUCIFERASE | URA3(pRS416) P(CUP1)-mCherry-LUCIFERASE | (Moharir et al., 2018) |

| pRS416 | vector | URA3(pRS416) | (Christianson et al., 1992) |

Fluorescence microscopy.

For microscopy, cells were grown overnight and then diluted into fresh medium in the morning to OD600=0.1. The cells were analyzed in exponential growth phase (OD600=0.6–0.8). For the microscopy a deconvolution microscope (DeltaVision, GE, Fairfield, CT, USA) was used.

Uracil uptake assay.

For the uracil uptake assay, cells were grown in SDcom-uracil media to mid log phase and 20μg/mL uracil was added to the cells for 10 minutes after which cells were kept on ice for 5 minutes. Cells were washed three times with ice cold water and resuspended in 50 μl of methanol. They were heated to 55°C for 10min, spun down and the supernatant was separated on an HPLC system using a Luna-NH2 column (Phenomenex) in presence of a 100%−80% acetonitrile/water gradient. The presence of uracil was detected by absorption spectroscopy at 260nm.

ATP measurements.

To follow ATP levels strains were transformed with pMB522, a plasmid expressing Syn-ATP (optimized version of luciferase, (Rangaraju et al., 2014)). Cells were grown in SDcom-ura to mid log phase. 10mM MES buffer pH 6 was added for 10 minutes prior to ATP measurement. The measurements were performed in a 96 well plate using the Polarstar Optima microplate reader (BMG Labtech). The mid-log phase cells together with 4mM luciferin were added to the well and the light emission over time was measured at 30°C.

Oxygen consumption.

Cells were grown to mid-log phase and oxygen consumption was measured at 30°C with a Clark electrode (Ocean Optics FOXY-R) and data was collected using the OOI sensors software program. Data were normalized according to OD600 of the individual cultures.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jasmine Phan, Brenden Adams and Madi Smith for critical reading of the manuscript. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS R01 GM123147 to M.B).

Abbreviations:

- MVB

multivesicular body

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- APC

amino acid polyamine organocation

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

Data accessibility

All data supporting the findings of this study can be found in Figures 1–7.

References:

- Appadurai D, Gay L, Moharir A, Lang MJ, Duncan MC, Schmidt O, Teis D, Vu TN, Silva M, Jorgensen EM, et al. (2020). Plasma membrane tension regulates eisosome structure and function. Mol Biol Cell 31, 287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M (2014). Quality control: quality control at the plasma membrane: one mechanism does not fit all. J Cell Biol 205, 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becuwe M, and Leon S (2014). Integrated control of transporter endocytosis and recycling by the arrestin-related protein Rod1 and the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5. eLife 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becuwe M, Vieira N, Lara D, Gomes-Rezende J, Soares-Cunha C, Casal M, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Vincent O, Paiva S, and Leon S (2012). A molecular switch on an arrestin-like protein relays glucose signaling to transporter endocytosis. J Cell Biol 196, 247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultynck G, Heath VL, Majeed AP, Galan JM, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, and Cyert MS (2006). Slm1 and slm2 are novel substrates of the calcineurin phosphatase required for heat stress-induced endocytosis of the yeast uracil permease. Mol Cell Biol 26, 4729–4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, and Hieter P (1992). Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapeau M, Merhi A, and Andre B (2014). Stress conditions promote yeast Gap1 permease ubiquitylation and down-regulation via the arrestin-like Bul and Aly proteins. J Biol Chem 289, 22103–22116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyert MS, and Philpott CC (2013). Regulation of cation balance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 193, 677–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deken RH (1966). The Crabtree effect: a regulatory system in yeast. J Gen Microbiol 44, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt SM, and Sauer U (2010). Transcriptional regulation of respiration in yeast metabolizing differently repressive carbon substrates. BMC Syst Biol 4, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisne M, Becam AM, Verdiere J, and Herbert CJ (1999). A ‘natural’ mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains derived from S288c affects the complex regulatory gene HAP1 (CYP1). Curr Genet 36, 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan JM, Moreau V, Andre B, Volland C, and Haguenauer-Tsapis R (1996). Ubiquitination mediated by the Npi1p/Rsp5p ubiquitin-protein ligase is required for endocytosis of the yeast uracil permease. J Biol Chem 271, 10946–10952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdieri L, Mehrotra S, Yu S, and Vancura A (2010). Transcriptional regulation in yeast during diauxic shift and stationary phase. OMICS 14, 629–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaddar K, Merhi A, Saliba E, Krammer EM, Prevost M, and Andre B (2014). Substrate-induced ubiquitylation and endocytosis of yeast amino acid permeases. Mol Cell Biol 34, 4447–4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens A, de La Fuente N, Forment J, Serrano R, and Portillo F (2000). Regulation of yeast H(+)-ATPase by protein kinases belonging to a family dedicated to activation of plasma membrane transporters. Mol Cell Biol 20, 7654–7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gournas C, Saliba E, Krammer EM, Barthelemy C, Prevost M, and Andre B (2017). Transition of yeast Can1 transporter to the inward-facing state unveils an alpha-arrestin target sequence promoting its ubiquitylation and endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 28, 2819–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovsepian J, Defenouillere Q, Albanese V, Vachova L, Garcia C, Palkova Z, and Leon S (2017). Multilevel regulation of an alpha-arrestin by glucose depletion controls hexose transporter endocytosis. J Cell Biol 216, 1811–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundal HS, and Taylor PM (2009). Amino acid transceptors: gate keepers of nutrient exchange and regulators of nutrient signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296, E603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, and Kim JH (2005). Glucose as a hormone: receptor-mediated glucose sensing in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Soc Trans 33, 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CB, Ott EM, Keener JM, Curtiss M, Sandrin V, and Babst M (2012). Regulation of membrane protein degradation by starvation-response pathways. Traffic 13, 468–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayikci O, and Nielsen J (2015). Glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener JM, and Babst M (2013). Quality control and substrate-dependent downregulation of the nutrient transporter fur4. Traffic 14, 412–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang MJ, Martinez-Marquez JY, Prosser DC, Ganser LR, Buelto D, Wendland B, and Duncan MC (2014). Glucose starvation inhibits autophagy via vacuolar hydrolysis and induces plasma membrane internalization by down-regulating recycling. J Biol Chem 289, 16736–16747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, MacGurn JA, Chu T, Stefan CJ, and Emr SD (2008). Arrestin-related ubiquitin-ligase adaptors regulate endocytosis and protein turnover at the cell surface. Cell 135, 714–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llopis-Torregrosa V, Ferri-Blazquez A, Adam-Artigues A, Deffontaines E, van Heusden GP, and Yenush L (2016). Regulation of the Yeast Hxt6 Hexose Transporter by the Rod1 alpha-Arrestin, the Snf1 Protein Kinase, and the Bmh2 14-3-3 Protein. J Biol Chem 291, 14973–14985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, and Pringle JR (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moharir A, Gay L, Appadurai D, Keener J, and Babst M (2018). Eisosomes are metabolically regulated storage compartments for APC-type nutrient transporters. Mol Biol Cell 29, 2113–2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsomme P, Slayman CW, and Goffeau A (2000). Mutagenic study of the structure, function and biogenesis of the yeast plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1469, 133–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munder MC, Midtvedt D, Franzmann T, Nuske E, Otto O, Herbig M, Ulbricht E, Muller P, Taubenberger A, Maharana S, et al. (2016). A pH-driven transition of the cytoplasm from a fluid- to a solid-like state promotes entry into dormancy. eLife 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell AF, and Schmidt MC (2019). AMPK-Mediated Regulation of Alpha-Arrestins and Protein Trafficking. Int J Mol Sci 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orij R, Urbanus ML, Vizeacoumar FJ, Giaever G, Boone C, Nislow C, Brul S, and Smits GJ (2012). Genome-wide analysis of intracellular pH reveals quantitative control of cell division rate by pH(c) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol 13, R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterstedt K, Larsson C, Bill RM, Stahlberg A, Boles E, Hohmann S, and Gustafsson L (2004). Switching the mode of metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Rep 5, 532–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin DS, Harris SL, Seto-Young D, and Haber JE (1989). Defective H(+)-ATPase of hygromycin B-resistant pma1 mutants fromSaccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 264, 21857–21864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer T, and Morley A (2014). An evolutionary perspective on the Crabtree effect. Front Mol Biosci 1, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaraju V, Calloway N, and Ryan TA (2014). Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell 156, 825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Klionsky DJ, Banta LM, and Emr SD (1988). Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol Cell Biol 8, 4936–4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seron K, Blondel MO, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, and Volland C (1999). Uracil-induced down-regulation of the yeast uracil permease. J Bacteriol 181, 1793–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R, Kielland-Brandt MC, and Fink GR (1986). Yeast plasma membrane ATPase is essential for growth and has homology with (Na+ + K+), K+- and Ca2+-ATPases. Nature 319, 689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer DK, and Piper RC (2011). A single ubiquitin is sufficient for cargo protein entry into MVBs in the absence of ESCRT ubiquitination. J Cell Biol 192, 229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szopinska A, Degand H, Hochstenbach JF, Nader J, and Morsomme P (2011). Rapid response of the yeast plasma membrane proteome to salt stress. Mol Cell Proteomics 10, M111 009589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volland C, Urban-Grimal D, Geraud G, and Haguenauer-Tsapis R (1994). Endocytosis and degradation of the yeast uracil permease under adverse conditions. J Biol Chem 269, 9833–9841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth WP, Olsen AE, Sbia M, Freedman KH, and Stillman DJ (2005). ACE2, CBK1, and BUD4 in budding and cell separation. Eukaryot Cell 4, 1018–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F, Dollard C, and Ricupero-Hovasse SL (1995). Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11, 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study can be found in Figures 1–7.