Abstract

The nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich receptor (NLR) protein HOPZ-ACTIVATED RESISTANCE 1 (ZAR1), an immune receptor, interacts with HOPZ-ETI-DEFICIENT 1 (ZED1)-related kinases (ZRKs) and AVRPPHB SUSCEPTIBLE 1-like proteins to form a pentameric resistosome, triggering immune responses. Here, we show that ZAR1 emerged through gene duplication and that ZRKs were derived from the cell surface immune receptors wall-associated protein kinases (WAKs) through the loss of the extracellular domain before the split of eudicots and monocots during the Jurassic period. Many angiosperm ZAR1 orthologs, but not ZAR1 paralogs, are capable of oligomerization in the presence of AtZRKs and triggering cell death, suggesting that the functional ZAR1 resistosome might have originated during the early evolution of angiosperms. Surprisingly, inter-specific pairing of ZAR1 and AtZRKs sometimes results in the formation of a resistosome in the absence of pathogen stimulation, suggesting within-species compatibility between ZAR1 and ZRKs as a result of co-evolution. Numerous concerted losses of ZAR1 and ZRKs occurred in angiosperms, further supporting the ancient co-evolution between ZAR1 and ZRKs. Our findings provide insights into the origin of new plant immune surveillance networks.

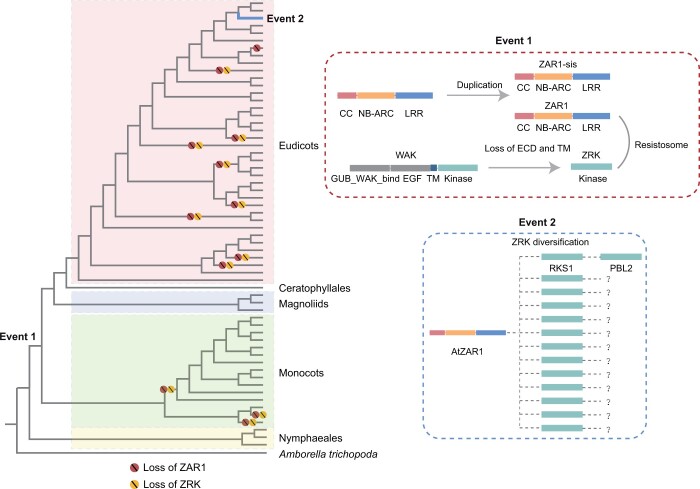

The ZAR1 resistosome, a pentameric complex that triggers plant immune signaling, is likely to have originated before the last common ancestor of eudicots and monocots during the Jurassic period.

Introduction

Plants and microbial pathogens have been engaged into antagonistic relationships for hundreds of millions of years (Han, 2019). Plants have evolved diverse immune strategies to thwart microbial pathogens (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Gao et al., 2018; Han, 2019; Zhou and Zhang, 2020). The first tier of plant immunity relies on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the cellular surface, most of which are receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (essentially RLKs lacking the intracellular kinase domain) (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Antolin-Llovera et al., 2012; Zhou and Zhang, 2020). PRRs are responsible for the perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns from invading pathogens or damage-associated molecular patterns derived from plants, eliciting pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) to cope with pathogen infection. In turn, microbes have evolved counter-strategies and secrete effector proteins into the host cells, thereby suppressing PTI (Dou and Zhou, 2012). Plants have further developed a second tier of defense mechanisms governed by the intracellular immune receptors nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich receptors (NLRs). NLRs detect pathogen effectors either directly or indirectly, inducing an array of defense responses, namely effector-triggered immunity (ETI), including a programmed cell death called the hypersensitive response (HR) (Zhou and Zhang, 2020). However, the dichotomy of plant immunity appears to be an oversimplified model, and PTI and ETI pathways can mutually potentiate to activate strong resistance to pathogens (Ngou et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2021).

NLR proteins are typically classified into two types, Toll/interleukin-1 receptor-NLRs and coiled-coil (CC)-NLRs (CNLs), based on their N-terminal signaling domains (Gao et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis thaliana, the CNL HOPZ-ACTIVATED RESISTANCE 1 (AtZAR1) is required for the recognition of diverse effector proteins (Lewis et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015; Seto et al., 2017; Laflamme et al., 2020). AtZAR1 constitutes preformed immune receptor complexes with closely related receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCKs), including ARABIDOPSIS HOPZ-ETI-DEFICIENT 1 (AtZED1), RESISTANCE-RELATED KINASE1 (RKS1), and ZED1-RELATED KINASE 3 (AtZRK3), which belong to the RLCK XII subfamily (referred to as ZRKs hereafter) (Wang et al., 2019a, 2019b). The AtZAR1–AtZED1, AtZAR1–AtRKS1, and AtZAR1–AtZRK3 complexes sense the bacterial canker or blast (Pseudomonas syringae) effectors HopZ1a and HopX1 (Lewis et al., 2013; Martel et al., 2020), the black rot pathogen (Xanthomonas campestris) effector AvrAC (Wang et al., 2015), and the P. syringae effectors HopF2 and HopO1 (Seto et al., 2017; Martel et al., 2020), respectively. In Nicotiana benthamiana, NbZAR1 indirectly recognizes the Xanthomonas perforans effector XopJ4 through an association with another ZRK member, XOPJ4 IMMUNITY 2 (JIM2) (Schultink et al., 2019). AvrAC is an enzyme that uridylylates RLCK VII subfamily members, including BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE 1 (AtBIK1), which is a key component of immune signaling modules mediated by PRRs (Zhou and Zhang, 2020), and AVRPPHB SUSCEPTIBLE 1-LIKE 2 (AtPBL2). AtBIK1 is a virulence target of AvrAC, which uridylylates AtBIK1 to impair plant defense responses (Feng et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). In contrast, the uridylylated AtPBL2 (AtPBL2UMP) is recruited to the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 complex through a direct interaction with AtRKS1 to trigger immunity, and thus AtPBL2 acts as a decoy that enables the perception of AvrAC (Feng et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015).

Recent cryo-electron microscopy structural studies showed that the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 complex is maintained in the resting state through an interaction between AtRKS1 and the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain of ADP-bound AtZAR1 (Wang et al., 2019a, 2019b). AtPBL2UMP binding to AtRKS1 causes a steric clash between a segment of AtRKS1 and the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) of AtZAR1 to release ADP, enabling AtZAR1 to bind ATP (Wang et al., 2019a). The ATP binding induces structural remodeling of AtZAR1 and the conformational switching of the CC domain, resulting in the formation of a pentameric AtZAR1–AtRKS1–AtPBL2UMP complex, known as the ZAR1 resistosome (Wang et al., 2019a). The very N-terminal amphipathic α helix (α1) of the CC domain forms a funnel-shaped structure required for its association to the plasma membrane (PM), which is essential for the cell death and disease resistance conferred by AtZAR1 (Wang et al., 2019a). A most recent study showed that the AtZAR1 resistosome acts as a calcium-permeable channel that triggers immune signaling by increasing cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (Bi et al., 2021).

Although evolutionary analyses of ZAR1 homologs indicated an ancient origin of ZAR1 (Lewis et al., 2010; Adachi et al., 2021), it remains largely mysterious how the ZAR1 resistosome originated and evolved in plants. In this study, we used a phylogenomic approach combined with functional analyses to explore the evolutionary history of the ZAR1 resistosome. We found that the functional ZAR1 resistosome originated during the early evolution of angiosperms and was lost convergently in many angiosperm lineages. Our study provides a comprehensive picture of how a plant resistosome originated and evolved, which has important implications for understanding the origin of new plant immune surveillance networks.

Results

ZAR1 originated through a duplication that occurred before the split of eudicots and monocots

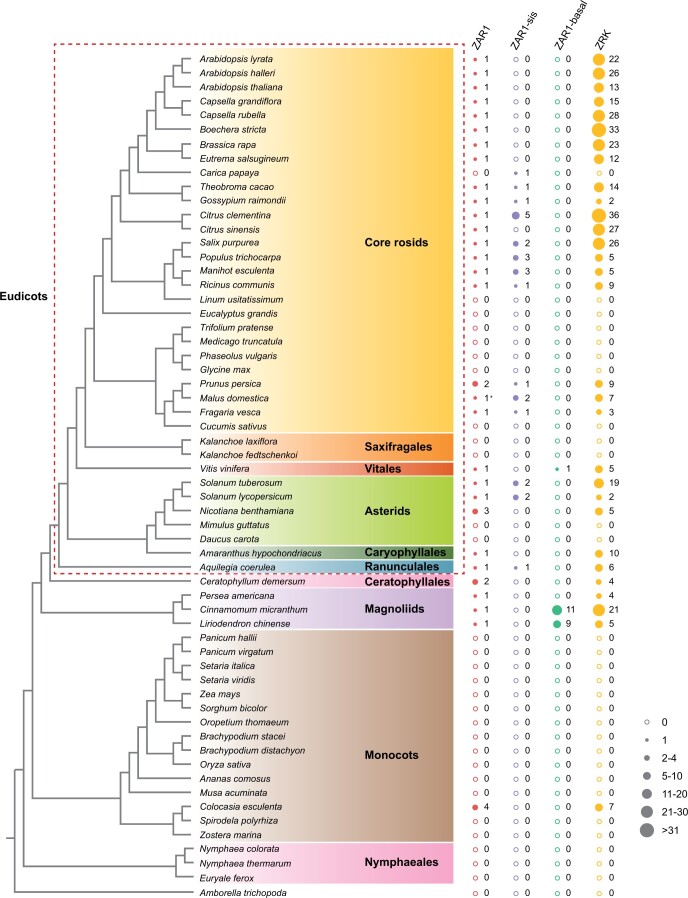

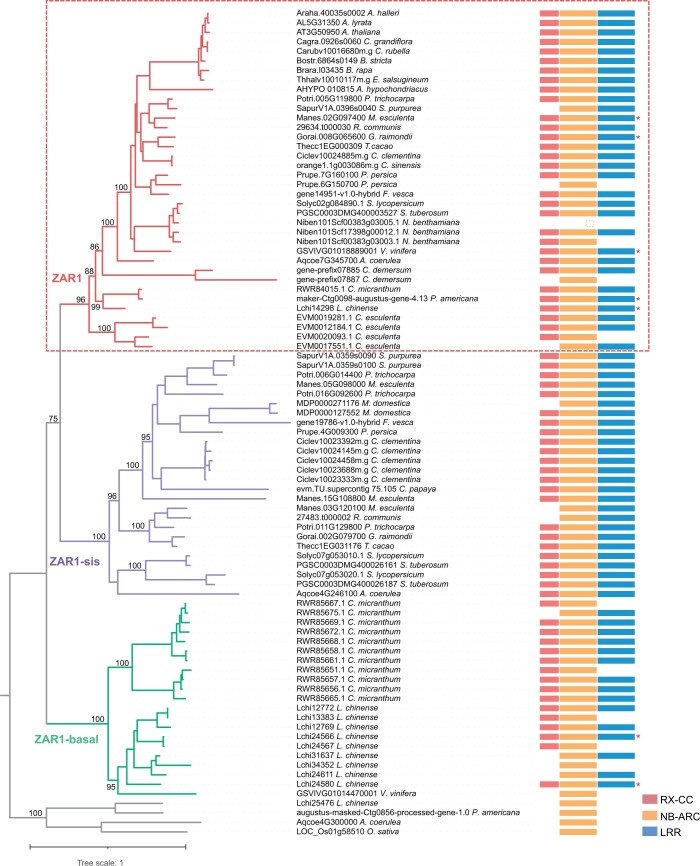

We employed a phylogenomic approach to explore the evolutionary history of the ZAR1 resistosome. Due to the extremely high copy numbers of NLRs and RLKs/RLCKs in plants (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001; Gao et al., 2018; Han, 2019; Gong and Han, 2021), we first used a combined similarity search and phylogenetic analysis approach to identify the proteins closely related to the ZAR1 resistosome components, namely AtZAR1 and AtZRKs, across 72 plant species that cover the major diversity of plants (Figure 1; Supplemental Data Set 1). We then performed phylogenetic analyses of the proteins closely related to AtZAR1 and AtZRKs. We found that the proteins closely related to AtZAR1 cluster into three groups with strong support, termed ZAR1 (ultrafast bootstrap approximation [UFBoot] = 96%), ZAR1-sis (UFBoot = 100%), and ZAR1-basal (UFBoot = 100%) (Figure 2; Supplemental Data Set 2). The ZAR1 group includes AtZAR1 and proteins from eudicots, Ceratophyllales, magnoliids, and monocots. No protein from Nymphaeales or Amborella trichopoda (the sister lineage to the other extant flowering plants) (Amborella Genome, 2013) was identified in the ZAR1 group (Figure 2). The ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal groups include proteins from eudicots and magnoliids, respectively (Figure 2). Taken together, our phylogenetic analyses suggest that ZAR1 arose from a gene duplication that occurred before the last common ancestor of eudicots and monocots, but likely after the divergence of angiosperms from Nymphaeales during the Jurassic period (Magallon et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Distribution of ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins in plants. For each plant species, the copy numbers of ZAR1, ZAR1-sis, ZAR1-basal, and ZRKs are shown next to the species names. The solid and open circles represent the presence and absence of the corresponding proteins, respectively. The size of each solid circle reflects the copy number. The asterisk indicates that the ZAR1 gene was identified using the TBLASTN algorithm to search the genome. The plant phylogeny is based on the literature (Li et al., 2019; One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes, 2019; Zeng et al., 2017).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of ZAR1-related proteins. The phylogeny was reconstructed based on full-length protein sequences using the maximum likelihood method. Four NLRs indicated by gray branches were used as outgroups. The ZAR1-related proteins are classified into three groups: ZAR1 (in red), ZAR1-sis (in purple), and ZAR1-basal (in green). For each protein, the domain architecture is shown next to the protein name. Different domains are indicated using different color stripes, and the color key is shown on the lower right. The asterisks indicate that these proteins were reannotated based on RNA-seq and genomic data. The values near the nodes are UFBoot values.

The three distinct groups of ZAR1-related proteins exhibit different evolutionary patterns. The copy numbers of ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal genes vary among different plants. This observation is consistent with the birth and death model of gene family evolution in which gene duplication repeatedly create new genes, and some new genes are maintained for a long time, while others become nonfunctional or are lost (Nei et al., 1997, 2008; Michelmore and Meyers, 1998). In contrast, most of the angiosperms in which ZAR1 was identified retain only one intact copy of ZAR1 (Figures 1 and 2). Several species (peach [Prunus persica], N. benthamiana, and Ceratophyllum demersum) encode more than one copy of ZAR1, but only one for each species contains an intact domain structure with a CC domain, nucleotide-binding site, and LRR (Figure 2). The only exception is Colocasia esculenta, a monocot that encodes four copies of ZAR1 (two of them possess intact domain structures). Because angiosperms underwent multiple independent whole genome duplications and prevalent small-scale gene duplications (Van de Peer et al., 2017; Clark and Donoghue, 2018), ZAR1 appears to have been convergently restored to single-copy status immediately following gene duplication (Paterson et al., 2006; De Smet et al., 2013). Notably, the integrated domains within ZAR1 orthologs of several species (Adachi et al., 2021) might be due to annotation errors, because no RNA-seq reads span the junction between ZAR1 and integrated domains. Thus, these ZAR1 sequences were reannotated based on RNA-seq and genome data (Figure 2).

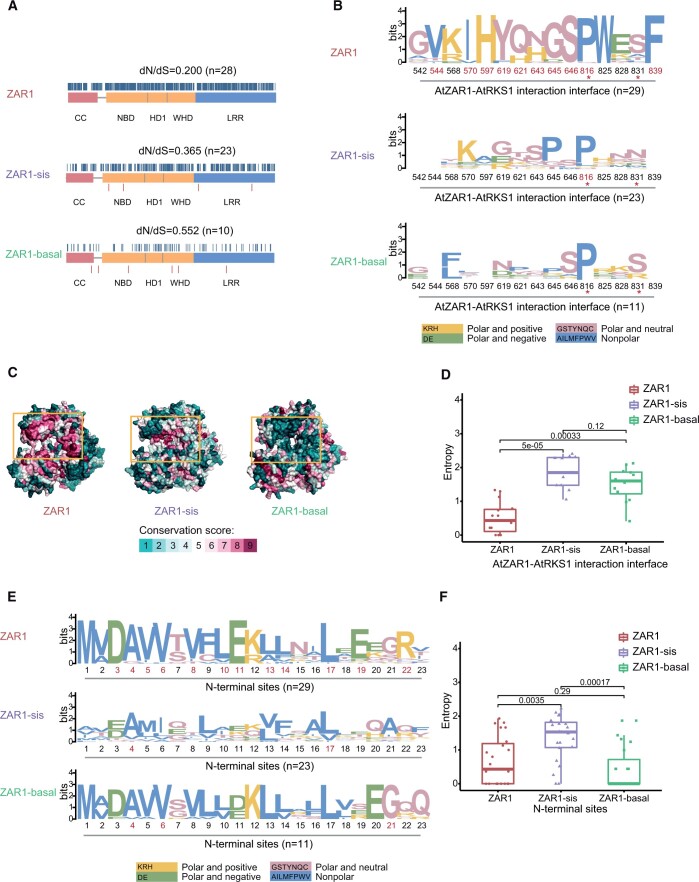

To assess the selection pressure acting on different ZAR1-related genes, we estimated the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous nucleotide substitution rates (dN/dS) and detected sites subject to negative or positive selection. The ZAR1 group (dN/dS = 0.200) underwent much stronger functional constraint than both the ZAR1-sis group (dN/dS = 0.365) and the ZAR1-basal group (dN/dS = 0.552) (Figure 3A). Moreover, the proportion of negatively selected sites in the ZAR1 group (56.5%; 492/871) is much higher than that in the ZAR1-sis group (35.0%; 308/879) and the ZAR1-basal group (10.0%; 87/873) (Figure 3A). The sites on the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interface are generally conserved, and 10/15 of these sites are subject to negative selection (Figure 3, B and C). However, for the ZAR1-sis group and the ZAR1-basal group, the corresponding sites are highly variable, and only 1/15 and none of these sites are under negative selection, respectively (Figure 3, B and C). For these sites, the Shannon entropy scores of both the ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal groups are significantly higher than that of the ZAR1 group (ZAR1 versus ZAR1-sis, P = 5 × 10−5, Wilcoxon test; ZAR1 versus ZAR1-basal, P = 0.00033, Wilcoxon test; Figure 3D), confirming that these sites are much more conserved in the ZAR1 group. Amino acids can be classified into four groups based on their polarity and charge; amino acid substitutions within the same group and between groups are termed conservative and radical changes, respectively (Zhang, 2000). For the ZAR1 group, most of the amino acid substitutions occurring in sites crucial for the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction are conservative changes (Supplemental Figure S1A). However, the changes between ZAR1 and ZAR1-sis or between ZAR1 and ZAR1-basal are frequently radical or indels (insertion-deletions) (Supplemental Figure S1A). Similarly, the first 23 N-terminal residues, which are essential for the channel activity, cell death, and disease resistance conferred by AtZAR1 (Wang et al., 2019a; Bi et al., 2021), exhibit different evolutionary patterns among the three ZAR1 groups. While 12 out of the 23 sites are subject to negative selection for the ZAR1 group, only 2 and 3 sites are negatively selected in the ZAR1-sis group and the ZAR1-basal group, respectively (Figure 3E). The Shannon entropy score of the ZAR1-sis group is significantly higher than that of the ZAR1 group (P = 0.0035, Wilcoxon test; Figure 3F). Taken together, these results suggest that the three groups of ZAR1-related genes have experienced different functional constraints and that the ZAR1 group proteins are likely to be associated with ZRKs to form the ZAR1 resistosome, posing stronger functional constraints on ZAR1 group proteins.

Figure 3.

Evolutionary analysis of the ZAR1-related proteins. A, Selection pressures on ZAR1-related proteins. For each group, typical domain architecture is shown with dN/dS ratio on the top. Blue and red short vertical lines represent sites subject to negative selection and positive selection, respectively. Numbers in brackets indicate the numbers of sequences analyzed. B, Sequence logos of the residues crucial for AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction. Amino acids are highlighted with different colors based on their polarity and charge, and the color key is shown at the bottom. Red asterisks indicate that these sites are not AtZAR1–AtRKS1 binding sites, but can affect AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction. Sites under negative selection are highlighted in red. Numbers in brackets indicate the numbers of sequences analyzed. C, Different conservation patterns of AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interfaces on the structures of ZAR1-related proteins. The structure of ZAR1 (6j5w) and predicted structure models of ZAR1-sis (Potri.006G014400) and ZAR1-basal (RWR85656.1) are colored based on the ConSurf conservation score of each residue. Yellow boxes represent the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interface. D, Differences in Shannon’s entropy scores for the residues crucial for AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction among three ZAR1-related groups. Entropy scores are illustrated using box plots. The upper and lower hinges represent the first and third quartiles, and the line within the box marks the median. The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 times that of interquantile range (IQR), and the upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no more than 1.5 times that of IQR. The names of groups are shown on the x-axis. Within the dataset of each group, the entropy score of each site is shown as scatter with no scale on the x-axis. Pairwise significance was determined by Wilcoxon test. E, Sequence logos of the first 23 residues. Amino acids are highlighted with different colors based on their polarity and charge, and the color key is shown at the bottom. Sites under negative selection are highlighted in red. Numbers in brackets indicate the numbers of sequences analyzed. F, Differences in Shannon’s entropy scores for the first 23 residues among three ZAR1-related groups. Entropy scores are illustrated using box plots. The upper and lower hinges represent the first and third quartiles, and the line within the box marks the median. The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 times of IQR, and the upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no more than 1.5 times of IQR. The names of groups are shown on the x-axis. Within the dataset of each group, the entropy score of each site is shown as scatter with no scale on the x-axis. Pairwise significance was determined by Wilcoxon test.

ZRKs originated from wall-associated protein kinases (WAKs) via the loss of the extracellular domain before the split of eudicots and monocots

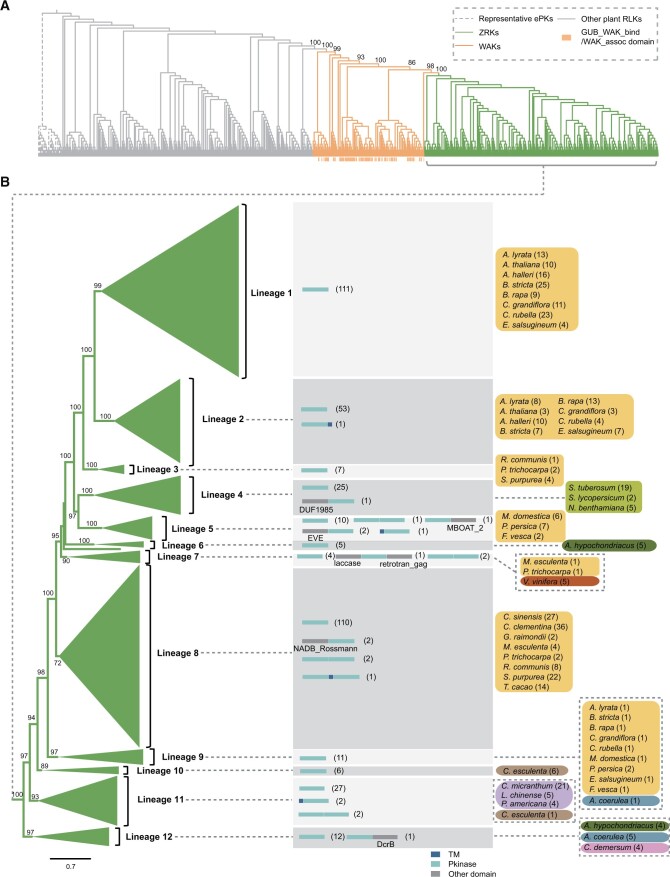

Next, we also used a phylogenomic approach to explore the origin and evolutionary history of ZRKs. Interestingly, large-scale phylogenetic analysis showed that ZRK-related proteins nest within the diversity of wall-associated protein kinases (WAKs), namely RLKs with extracellular wall-associated receptor kinase galacturonan-binding and epidermal growth factor domains, with strong support (UFBoot = 100%) (Figure 4A). It follows that ZRKs originated from WAKs by losing their extracellular domains. Consistent with the distribution of ZAR1 proteins, ZRKs were identified in eudicots, Ceratophyllales, magnoliids, and monocots, but not in Nymphaeales or A. trichopoda (Figure 1; Supplemental Data Set 3). Unlike ZAR1, the copy numbers of ZRKs vary greatly among different species (Figure 1). The phylogenetic analysis showed that ZRKs from each plant species fall into distinct lineages, suggesting that ZRKs underwent a complex history of gene duplication and gene loss (Figure 4B). Among the well characterized ZRKs, AtRKS1 and AtZRK3 are more closely related to each other than to AtZED1, and AtZED1 and AtRKS1/AtZRK3 originated through a gene duplication occurring during the early evolution of Brassicaceae, more specifically before the spit of Arabidopsis and Brassica during the Eocene period (Beilstein et al., 2010).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationship of ZRK-related proteins. A, Relationship of ZRK-related proteins, WAKs, and other RLKs. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed based on the kinase domain sequences using the maximum likelihood method. Other ePKs (shown with dashed branches) were used as outgroups. The values near the selected nodes are UFBoot values. B, Enlarged phylogenetic tree of ZRK-related proteins. The values near the nodes are UFBoot values. ZRKs are classified into 12 lineages (collapsed into 12 gray triangles). ZRK domain architectures are displayed near the corresponding lineages. Different domains are highlighted in different color stripes, and the color key is shown on the lower right. The numbers near each domain architecture indicate the copy numbers of the ZRKs with this domain architecture. The numbers in brackets next to the plant species names represent the copy numbers of ZRKs in that plant species.

The sites on the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interface are well conserved among the AtZRKs (Supplemental Figure S2A). For the Arabidopsis WAKs (AtWAKs), some of these sites are well conserved but exhibit different conservation patterns. Notably, residues 35, 41, 44, 45, and 338 (corresponding to AtRKS1) of AtZRKs are well conserved, but are different from those of the AtWAKs, suggesting that AtZRKs gained the ability to interact with AtZAR1 after ZRKs originated from WAKs. In contrast, the sites on the AtRKS1–AtPBL2 interaction interface are highly variable among the AtZRKs, but more conserved among the AtWAKs (Supplemental Figure S2B). The different conservation patterns among AtZRKs on AtZAR1–AtRKS1 and AtRKS1–AtPBL2 interaction interfaces were also observed across different ZRK lineages (Supplemental Figure S2, C and D), indicating that ZRKs might have maintained association with ZAR1 and diversified to recognize diverse decoys/guardees.

The prominent catalytic motifs, the ATP-binding β3 lysine, the catalytic aspartate within the catalytic loop His-Arg-Asp-X-X-X-X-Gln (HRDXXXXN) motif, and the metal-binding aspartate of the activation loop Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) motif (Kwon et al., 2019), are highly conserved among the AtWAKs, but not among AtZRKs, which is consistent with the pseudo-kinase nature of ZRKs (Supplemental Figure S2E). Taken together, our results suggest that ZRKs originated from WAKs by losing their extracellular domains, at least before the split of eudicots and monocots but possibly after the divergence of angiosperms from Nymphaeales during the Jurassic period (Magallon et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019).

ZAR1 orthologs, but not ZAR1 paralogs, confer cell death when triggered by AtZRKs

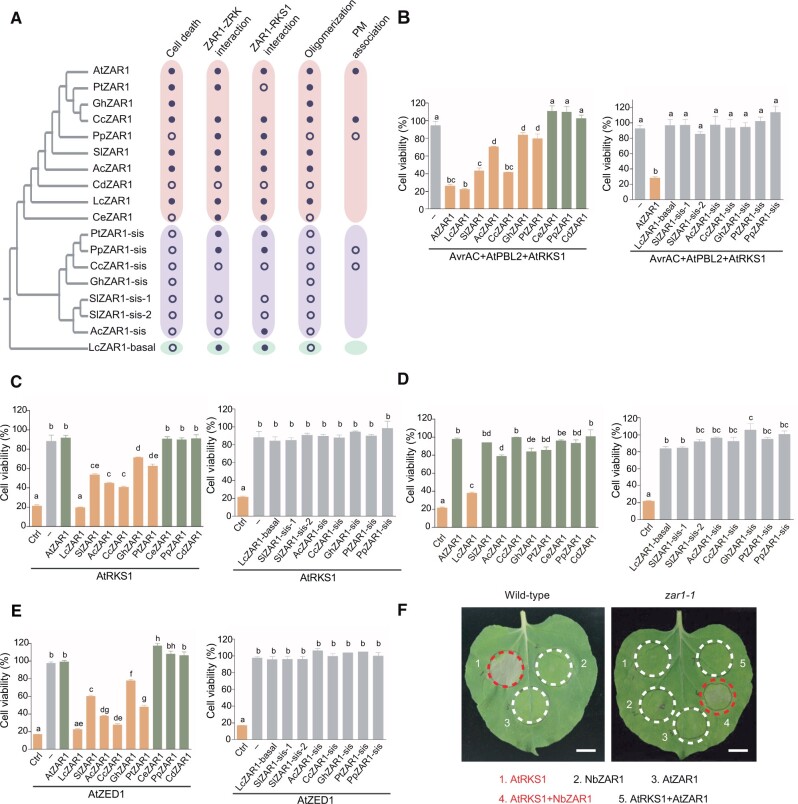

To investigate the functionality of ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs (ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal proteins), we focused on 10 representative plant species, including 7 eudicots (A. thaliana, Gossypium hirsutum [cotton, Malvales], Citrus clementina [clementine, Sapindales], Populus trichocarpa [poplar, Malpighiales], P. persica [peach, Rosales], Solanum lycopersicum [tomato, Solanales], and Aquilegia coerulea [columbine, Ranunculales]), one Ceratophyllales (C. demersum), one Magnoliids (Liriodendron chinense), and one monocot (Colocasia esculenta [taro, Alismatales]). We cloned a total of 18 ZAR1-related genes, among which 10 were ZAR1 orthologs, 7 were ZAR1-sis genes, and 1 was a ZAR1-basal gene (Figure 5A; Supplemental Figure S1B; Supplemental Data Set 4). We examined the ability of ZAR1 orthologs or paralogs to complement the Arabidopsis zar1 mutant in cell death response in protoplasts. As previously observed, transient overexpression of AvrAC, AtRKS1, AtPBL2, and AtZAR1 in zar1 protoplasts led to cell death (Figure 5B). Six additional ZAR1 orthologs (LcZAR1, SlZAR1, AcZAR1, CcZAR1, GhZAR1, and PtZAR1) induced cell death when co-expressed with AvrAC, AtRKS1, and AtPBL2 in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts, whereas the remaining three (CeZAR1, PpZAR1, and CdZAR1) did not (Figure 5B). We also tested seven ZAR1-sis group members (SlZAR1-sis-1, SlZAR1-sis-2, AcZAR1-sis, CcZAR1-sis, GhZAR1-sis, PtZAR1-sis, and PpZAR1-sis) and one ZAR1-basal group member (LcZAR1-basal), but none of them triggered cell death (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Functional analysis of ZAR1-related proteins. A, Summary of functional analysis results. Solid and open circles represent the presence and absence of the corresponding function, respectively. The phylogenetic relationship of the ZAR1-related proteins is based on Figure 2. Oligomerization and PM association indicate oligomerization and PM association induced by AtRKS1, respectively. B, Multiple ZAR1 orthologs (left) but not paralogs (right) confer AvrAC-induced cell death in protoplasts. Cell viability of Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts transfected with ZAR1s, AtRKS1, AtPBL2, and AvrAC was measured at 12 h after transfection. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtPBL2/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a positive control (Ctrl) of immune-activated cell death. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtPBL2/AtRKS1 served as a mock control (–). Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error (se) from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. C, Multiple ZAR1 orthologs (left) but not paralogs (right) confer AtRKS1-induced cell death in protoplasts. Cell viability of Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts transfected with ZAR1s and AtRKS1 was measured at 12 h after transfection. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtPBL2/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a positive control (Ctrl) of immune-activated cell death. Protoplasts expressing AtRKS1 alone served as a mock control (–). Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± SE from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were performed 3 times with similar results. D, ZAR1 orthologs (left) or paralogs (right) alone cannot trigger cell death in protoplasts, with the exception of LcZAR1. Protoplasts in the zar1 background were transfected with the indicated constructs, and cell viability was measured. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtPBL2/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a positive control (Ctrl) of immune-activated cell death. Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± se from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. E, Multiple ZAR1 orthologs (left) but not paralogs (right) confer AtZED1-induced cell death in protoplasts. Cell viability of Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts transfected with ZAR1s and AtZED1 was measured at 12 h after transfection. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtPBL2/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a positive control (Ctrl) of immune-activated cell death. Protoplasts expressing AtZED1 alone served as a mock control (–). Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± se from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. F, AtRKS1 overexpression triggers NbZAR1 activation. The indicated genes were transiently expressed using Agrobacterium in N. benthamiana WT and the zar1-1 mutant. HR (red circles) was assessed 2 days after inoculation. The experiments were performed 3 times with similar results. Scale bars, 1 cm.

To further investigate whether cell death was the result of complementation in AvrAC recognition, we examined with the catalytic mutant AvrACH469A. Transient overexpression of AvrACH469A, AtRKS1, AtPBL2, and AtZAR1 no longer activated cell death. However, AvrACH469A still activated six additional ZAR1 orthologs (LcZAR1, SlZAR1, AcZAR1, CcZAR1, GhZAR1, and PtZAR1), as did AvrAC (Supplemental Figure S3), suggesting that the AvrAC recognition may not account for the observed cell death of ZAR1 orthologs. We hypothesize that cell death may be due to autoactivation.

Surprisingly, overexpression of these six ZAR1 orthologs (LcZAR1, SlZAR1, AcZAR1, CcZAR1, GhZAR1, and PtZAR1) and AtRKS1 triggered cell death in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts without the overexpression of AtPBL2 and AvrAC, whereas overexpression of AtZAR1 and AtRKS1 did not trigger cell death (Figure 5C). This is unexpected and suggests that AtRKS1 by itself is capable of activating these heterologous ZAR1 proteins. Because none of the AtZRKs, when overexpressed, activates AtZAR1 in the absence of AtPBL2 and AvrAC (Wang et al., 2015), these results suggest that the inter-specific pairing of ZAR1s and AtZRKs may sometimes cause cell death. In support of the notion that the activation of these heterologous ZAR1s depends on AtRKS1, overexpression of five out of these six ZAR1s did not cause cell death in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts (Figure 5D). The only exception was with LcZAR1, whose overexpression lowered cell viability to 40% (Figure 5D), suggesting that the native levels of AtRKS1 and/or other AtZRKs might be sufficient to partially activate LcZAR1. Consistent with this notion, overexpression of AtRKS1 further enhanced the LcZAR1-mediated cell death and lowered the viability to 20% (Figure 5C). To further test this hypothesis, we transiently overexpressed various ZAR1s together with AtZED1 in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts. Indeed, overexpression of AtZED1 with SlZAR1, AcZAR1, CcZAR1, GhZAR1, and PtZAR1 similarly triggered cell death in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts (Figure 5E).

We then transiently overexpressed AtRKS1 in N. benthamiana, and this was sufficient to induce a strong HR in wild-type (WT) leaves, but not in the Nbzar1 mutant (Figure 5F), indicating that AtRKS1 overexpression triggers NbZAR1 activation. It should be noted, however, that transient overexpression of AtZED1 did not activate NbZAR1 in N. benthamiana (Baudin et al., 2017). Taken together, these results provide evidence that the mismatch of some of the ZAR1s and AtZRKs may sometimes, but not always, activate ZAR1s and trigger cell death. To test whether ZRKs from other species could activate ZAR1s, we transiently overexpressed various ZRK proteins (AtRKS1, LcZRK, SlZRK, AcZRK, CcZRK, GhZRK, PtZRK, CeZRK, PpZRK, and CdZRK) in Arabidopsis rks1 protoplasts. Expression of these ZRKs alone did not induce cell death (Supplemental Figure S4A). When AtZAR1 or CcZAR1 and various ZRKs were coexpressed, the co-expression of AtRKS1/SlZRK and CcZAR1 triggered cell death in Arabidopsis rks1 protoplasts (Supplemental Figure S4, B and C). These data indicate that interspecific interactions of ZAR1s and ZRKs can activate ZAR1s. Nevertheless, our results suggest that ZAR1 orthologs, but not ZAR1 paralogs, can induce cell death in the presence of AtZRKs, indicating functional divergence between ZAR1 orthologs and ZAR1 paralogs.

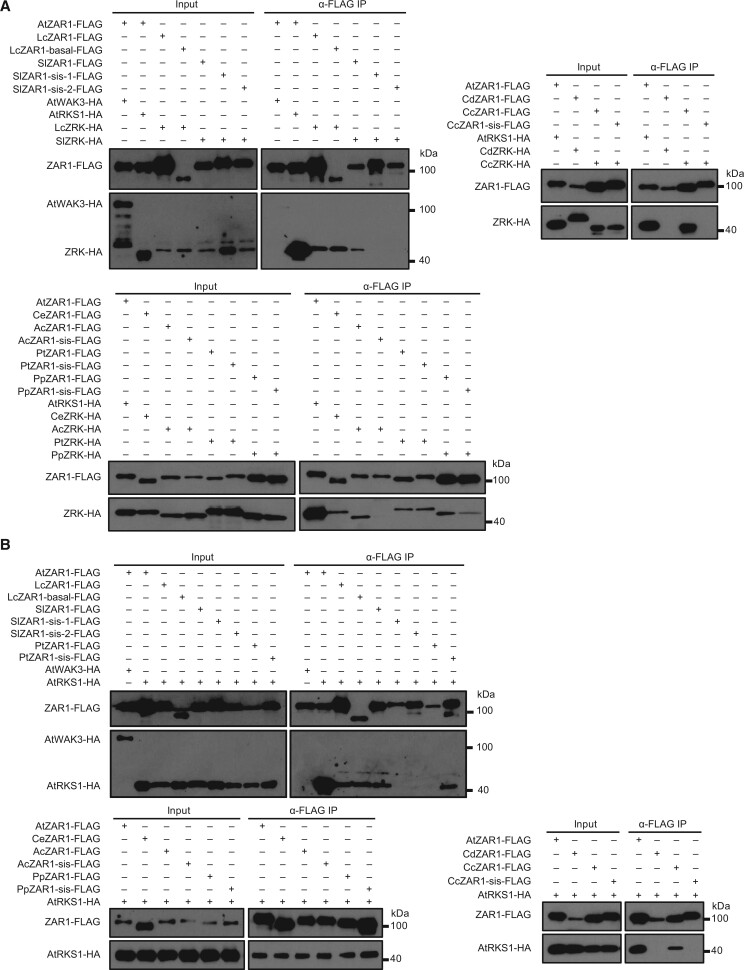

Differential interactions of ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs with ZRK proteins

Given the functional divergence between ZAR1 orthologs and ZAR1 paralogs, we sought to investigate whether their ability to interact with ZRKs explains their functional difference in triggering cell death. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments showed that eight out of nine ZAR1 orthologs tested (AtZAR1, LcZAR1, SlZAR1, CeZAR1, AcZAR1, PtZAR1, PpZAR1, and CcZAR1) interacted with their corresponding ZRKs, with the exception of CdZAR1, whereas seven ZAR1 paralogs exhibited variable abilities to interact with their corresponding ZRKs. Two SlZAR1-sis, one AcZAR1-sis, and one CcZAR1-sis failed to interact with their corresponding ZRKs (Figure 6A), but PtZAR1-sis, PpZAR1-sis, and LcZAR1-basal appeared to be able to interact with their corresponding ZRKs. We further tested the ability of ZAR1 orthologs and ZAR1 paralogs to interact with the AtRKS1 protein by co-IP assays. The results were largely consistent with the results described above, with only two exceptions: AcZAR1-sis (which did not interact with AcZRK) interacted with AtRKS1, and PtZAR1 (which interacted with PtZRK) did not interact with AtRKS1 (Figure 6B). Consistent with the evolutionary analyses, AtWAK3 failed to interact with AtZAR1, indicating that ZRKs likely gained the ability to interact with ZAR1s after diverging from WAKs (Figure 6, A and B). Therefore, the interactions detected by co-IP per se seem to be insufficient to explain the functional differentiation between ZAR1 orthologs and ZAR1 paralogs.

Figure 6.

Interaction analysis of ZAR1-related proteins with ZRK-related proteins. A, ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs differentially interact with ZRKs. The indicated constructs were transfected into Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts. Total protein was subjected to co-IP assays. Co-IP was performed using agarose-conjugated anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) antibodies, and immunoblots were detected with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. All assays were performed 3 times, and a representative photograph is shown. B, ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs differentially interact with AtRKS1. Protoplasts isolated from Arabidopsis rks1 plants were transfected with the indicated constructs for co-IP assays. Co-IP was performed using α-FLAG antibodies, and immunoblots were detected with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. All assays were performed 3 times, and a representative photograph is shown.

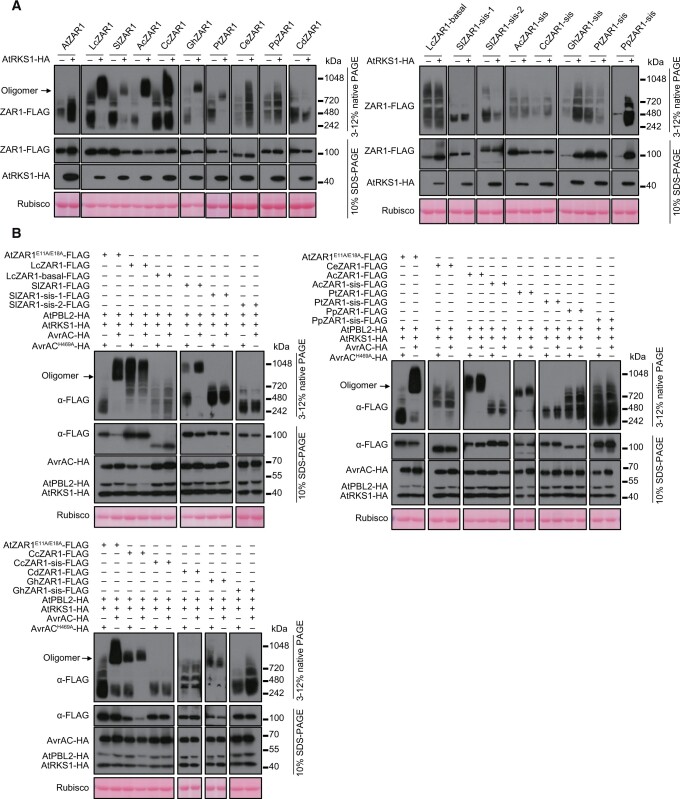

Functional oligomerization only occurs for ZAR1 orthologs that are capable of triggering cell death

Because AtZAR1 is activated by a steric clash between an AtRKS1 loop and the NBD of ZAR1 upon the recruitment of AtPBL2UMP, the precise conformational arrangements of the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 complex are crucial for this process. The extensive variations of the ZRK-interacting interface in ZAR1 paralogs (Figure 3, B and C) suggest that the observed interactions with ZRKs for some of these ZAR1 paralogs are likely to be nonproductive. To test this possibility, we took advantage of the activation of ZAR1 by inter-specific pairing with AtRKS1 and employed blue native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) assays to test whether this activation is associated with an AtRKS1-induced oligomerization of these ZAR1 orthologs and ZAR1 paralogs in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts. Consistent with the functional data described above, LcZAR1, SlZAR1, AcZAR1, CcZAR1, GhZAR1, and PtZAR1 (which possess cell death-triggering activity) migrated to large complexes induced by AtRKS1, which is indicative of oligomerization of these ZAR1 orthologs (Figures 5, A and 7, A). In contrast, none of the ZAR1 paralogs tested (SlZAR1-sis-1, SlZAR1-sis-2, AcZAR1-sis, CcZAR1-sis, GhZAR1-sis, PtZAR1-sis, PpZAR1-sis, and LcZAR1-basal) showed an AtRKS1-induced mobility shift in zar1 protoplasts (Figures 5, A and 7, A).

Figure 7.

Oligomerization analysis of ZAR1-related proteins. A, ZAR1 orthologs but not paralogs oligomerize upon activation by AtRKS1. BN-PAGE assays show AtRKS1-induced oligomerization of ZAR1 orthologs but not paralogs in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The indicated constructs were transfected into zar1 protoplasts. Total protein was subjected to BN-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. All assays were performed 3 times, and a representative photograph is shown. B, ZAR1 orthologs but not paralogs oligomerize upon activation by AvrAC. Protoplasts isolated from Arabidopsis zar1 plants were transfected with the indicated constructs for BN-PAGE assays. All assays were performed 3 times, and a representative photograph is shown.

We also tested three ZAR1 orthologs that were incapable of triggering cell death: CeZAR1, PpZAR1, and CdZAR1. While these proteins showed a smearing pattern in BN-PAGE, this occurred even in the absence of AtRKS1 overexpression. Similarly, some of the ZAR1 paralogs also displayed smear patterns independent of AtRKS1 overexpression in BN-PAGE assays. This phenomenon has been observed in some of the nonfunctional AtZAR1 mutants (Hu et al., 2020). These smear patterns were probably caused by the aggregation of misfolded proteins unrelated to ZAR1 activation. These results support the notion that the ZAR1 paralogs and several nonfunctional ZAR1 orthologs were unable to form productive protein complexes with AtRKS1. Moreover, we investigated whether AvrAC could induce oligomerization of various ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs. As expected, AvrAC, but not the catalytic mutant AvrACH469A, induced AtZAR1E11A/E18A oligomerization in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts. LcZAR1, AcZAR1, and CcZAR1, which showed strong mobility shifts in response to AtRKS1 overexpression, did not further respond to AvrAC (Figure 7B). GhZAR1 and PtZAR1, which showed modest mobility shifts in response to AtRKS1 overexpression, did not further respond to AvrAC. Interestingly, SlZAR1, which showed a modest mobility shift in response to AtRKS1 overexpression, displayed a much stronger mobility shift in response to AvrAC compared to AvrACH469A, indicating that AvrAC further enhanced SlZAR1 oligomerization (Figure 7B). This result is consistent with the greater cell death observed when SlZAR1 was co-transfected with AtRKS1, AtPBL2, and AvrAC (∼40% viability) compared to co-transfection of SlZAR1 and AtRKS1 (∼55% viability; Figure 5, B and C). For other ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs, AvrAC and AvrACH469A were similarly unable to induce a mobility shift (Figure 7B). Together, these results suggest that ZAR1 orthologs, but not ZAR1 paralogs, can form productive oligomers in response to AtRKS1 to trigger cell death.

To investigate whether the observed oligomerization is indeed functional, we tested whether AtRKS1 overexpression leads to increased PM association for ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs. Indeed, membrane fractionation experiments showed that CcZAR1, but not CcZAR1-sis, PpZAR1 or PpZAR1-sis, exhibited an AtRKS1-induced PM enrichment (Figure 5A; Supplemental Figure S5A). We further tested whether AvrAC could enhance the PM association for selected ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs. As expected, AvrAC-induced PM association was observed for AtZAR1 and SlZAR1, but not for SlZAR1-sis-1, PpZAR1, or PpZAR1-sis (Supplemental Figure S5B). These results are consistent with the results of oligomerization and cell death observation, suggesting that the PM association only occurs to ZAR1 orthologs that are functional in cell death and oligomerization.

The entire ZAR1 resistosome was repeatedly lost in angiosperms

Initially, we found that ZAR1 and ZRKs were absent in many angiosperms, and most of the monocots examined in this study lacked ZAR1 or ZRK proteins in their genomes. When mapping the distribution of ZAR1 and ZRKs across angiosperms, an intriguing pattern emerged: in all the species studied, if there was no ZAR1, there were also no ZRKs (Figure 1). Given that ZRKs from one species fall into distinct lineages, the distribution pattern involves a concerted loss of diverse ZRKs following the loss of ZAR1. We identified a total of 11 independent resistosome loss events across 56 angiosperms, suggesting that the ZAR1 resistosome was repeatedly lost as a whole during the course of angiosperm evolution. In contrast, no such concerted loss was observed between ZAR1-sis and ZRKs or between ZAR1-basal and ZRKs. The concerted loss of ZAR1 and ZRKs in multiple angiosperm lineages further supports the notion that ZAR1 and ZRKs co-evolved and that ZAR1 and ZRKs were assembled into the resistosome complex before the emergence of the last common ancestor of eudicots and monocots.

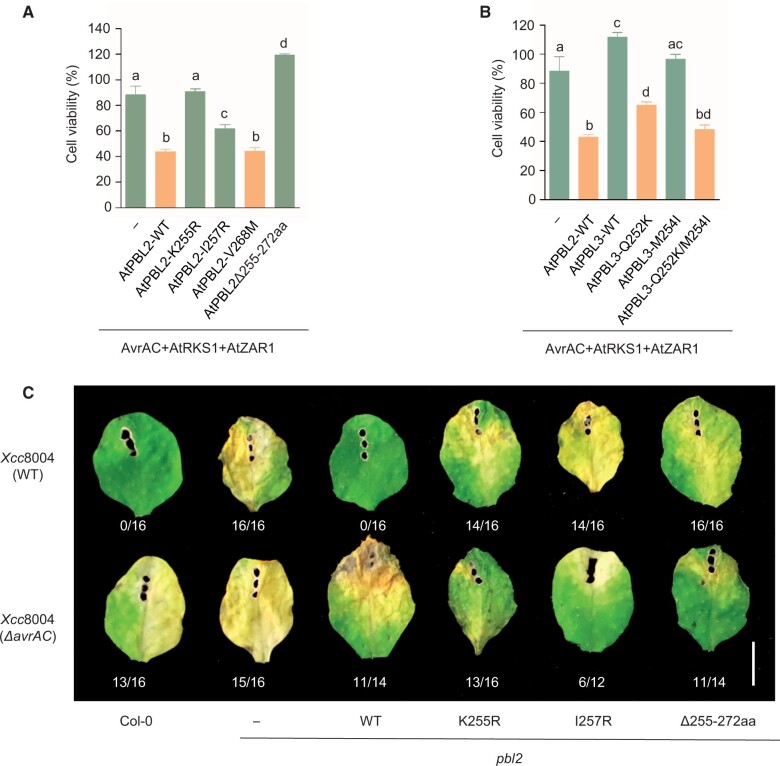

AtPBL2 was recruited into the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 complex in relatively recent time

AvrAC uridylylates a number of RLCK VII members including AtBIK1 and many AtPBLs to promote bacterial virulence (Feng et al., 2012). The uridylylation of AtPBL2, however, is not required for virulence but is required for AtZAR1-mediated ETI (Wang et al., 2015). AtPBL2 is thus considered to be a decoy that specifically monitors the activity of AvrAC to trigger AtZAR1-mediated ETI. The uridylalated loop of AtPBL2 directly interacts with the activation segment of RKS1. Besides the two uridylylated residues (Ser253 and Thr254), five additional residues (Lys255, Gly258, Val268, Thr270, and Gly271) located immediately after the uridylylation sites also make direct contact with AtRKS1 (Supplemental Figure S6). We investigated how mutations in this segment affect AvrAC-induced cell death and disease resistance. AtPBL2K255R, AtPBL2I257R, and AtPBL2Δ255-272aa, but not AtPBL2V268M mutations reduced the cell death activity in pbl2 protoplasts and resistance to Xcc8004 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure 8, A and C; Supplemental Figure S7C). Expression of the catalytic mutant AvrACH469A no longer induced cell death (Supplemental Figure S7A). These results indicate that Lys255 and Ile257 are essential for the immune function of AtPBL2.

Figure 8.

Functional analyses of AtPBL2/AtPBL3 proteins. A, AtPBL2 mutations impair AvrAC-induced cell death in Arabidopsis. Cell viability of pbl2 protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs was measured at 12 h after transfection. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtRKS1/AtZAR1/AtPBL2 served as a positive control. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a mock control (–). Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± se from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. B, AtPBL3 substitutions confer AvrAC-induced cell death in Arabidopsis. Cell viability of pbl2 protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs was measured at 12 h after transfection. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtRKS1/AtZAR1/AtPBL2 served as a positive control. Protoplasts expressing AvrAC/AtRKS1/AtZAR1 served as a mock control (–). Shown are values relative to the mock control, which is set as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± se from three biological replicates of protoplasts transfected with the indicated constructs. Different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-test). The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. C, AtPBL2 K255 and I257 confer disease resistance to Xcc8004 in Arabidopsis. WT (Col-0) and pbl2 transgenic plants carrying the indicated AtPBL2 transgenes were inoculated with the indicated bacteria, and disease symptoms were photographed 7 days after inoculation. The numbers indicate the number of leaves showing disease symptoms out of the total number of leaves inoculated. Scale bars, 0.5 cm. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results. –, pbl2 control plants.

Evolutionary analyses suggested that AtPBL2 and AtPBL3 originated through a duplication that occurred before the split between Arabidopsis and Brassica in the middle Eocene period (∼43 million years ago) (Supplemental Figure S6; Beilstein et al., 2010). Previous studies showed that the loss-of-function mutation of AtPBL2 is sufficient to abolish the recognition of AvrAC delivered by Xcc8004 (Guy et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). We verified this by transfecting pbl2 protoplasts with AtPBL2 and AtPBL3 constructs. As expected, pbl2 protoplasts transfected with AtPBL2, but not AtPBL3, along with AtZAR1, AtRKS1, and AvrAC triggered strong cell death (Figure 8B). Lys255 and Ile257 in AtPBL2 transitioned from Gln and Met, respectively, after the gene duplication event, creating AtPBL2 and AtPBL3 (Supplemental Figure S6). We substituted the corresponding residue Gln252 in AtPBL3 with Lys (AtPBL3Q252K). pbl2 protoplasts transfected with AtPBL3Q252K along with AvrAC, AtZAR1, and AtRKS1 showed pronounced cell death activity, albeit slightly weaker than that conferred by AtPBL2 (Figure 8B). Because Ile257 is unique to AtPBL2 (Supplemental Figure S6) and is required for cell death triggered by AvrAC, we introduced this residue into AtPBL3 to generate AtPBL3Q252K/M254I. Transfection of pbl2 protoplasts with this construct led to strong cell death indistinguishable from that of pbl2 protoplasts transfected with AtPBL2 (Figure 8B), and the expression of the catalytic mutant AvrACH469A no longer induced cell death (Supplemental Figure S7B), supporting the notion that these two substitutions are responsible for the evolution of AtPBL2. Therefore, these results suggest that AtPBL2 might have been recruited into the ZAR1 resistosome in relatively recent time, only before the split of Arabidopsis and Brassica.

Discussion

In this study, we used a phylogenomic approach combined with functional analyses to investigate the origin and evolution of the ZAR1 resistosome. We found that both ZAR1 and ZRKs originated during the early evolution of angiosperms. ZAR1 arose through a gene duplication of NLRs, which is consistent with a recent study (Adachi et al., 2021), whereas ZRKs were derived from WAKs through the loss of the extracellular domains. The sites on the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interfaces are well conserved in the ZAR1 group, but more variable in ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal groups. These variations are correlated with productive interactions of multiple ZAR1 orthologs, but not paralogs, with AtRKS1. All these lines of evidence suggest that the functional ZAR1 resistosome is likely to have originated before the last common ancestor of eudicots and monocots but after the divergence of angiosperms from Nymphaeales in the Jurassic period (Magallon et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). The ZAR1 resistosome is not present in all green plants, but is specific to angiosperms. The ZAR1 resistosome originated through tinkering with pre-existing immune proteins, representing an intriguing example of molecular tinkering, which proposes that evolution primarily works on what already exists to produce novelties (Jacob, 1977).

Our experimental data provide the unexpected finding that interspecific pairing of AtZRKs with ZAR1 orthologs, but not with ZAR1 paralogs, often led to cell death activation, suggesting that interspecific interactions of ZAR1s and ZRKs may sometimes lead to premature activation of ZAR1s. This is reminiscent of the phenomenon of hybrid necrosis in which combination of certain alleles of immune components leads to autoimmunity in the absence of pathogen attack (Bomblies and Weigel, 2007; Li and Weigel, 2021). Thus, the co-evolution of ZAR1s and ZRKs within the species seems to be important for maintaining the proper configuration of preformed ZAR1–ZRK complexes so that the ZAR1 is not activated prematurely. Although we do not know precisely how the premature activation of ZAR1s occurred, it is plausible that interspecific ZAR1–ZRK pairs adopt a configuration in which a certain segment impedes the proper conformation of the ZAR1 NBD to release ADP, mimicking the effect caused by AtPBL2UMP binding to AtRKS1.

Although it is not possible at this point to predict which effectors are recognized by all the ZRKs, our results suggest that functional divergence exists between ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs. Some ZAR1-sis and ZAR1-basal proteins seem to be able to interact with ZRKs in co-IP assays, possibly through interfaces different from those in the ZAR1–RKS1 interaction. These interactions were nonproductive, as indicated by a lack of AtRKS1-induced or AvrAC-induced oligomerization and PM association of these ZAR1 paralogs in Arabidopsis zar1 protoplasts, possibly due to a different conformation from that of the ZAR1 resistosome. Further functional analyses showed that AtRKS1-induced cell death only occurred to ZAR1 orthologs that were able to form productive interactions with ZRKs, but not ZAR1 paralogs.

NLR genes typically evolve through frequent gene duplication and gene deletion events, a process known as the birth and death model (Michelmore and Meyers, 1998), and thus the copy numbers of NLR genes vary among different plant species (Gao et al., 2018). Many NLRs are subject to strong positive selection, having important implications for resistance specificities (Michelmore and Meyers, 1998; Mondragon-Palomino et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2018; Han, 2019). However, as a CNL gene, ZAR1 exhibits a rather different mode of evolution. ZAR1 has been retained mostly as a singleton gene during the course of angiosperm evolution, although angiosperms underwent multiple independent whole-genome duplications and pervasive small-scale gene duplications, suggesting that ZAR1 is likely to be a so-called “duplication resistant” gene (Paterson et al., 2006). No signal of positive selection was detected in ZAR1, but instead ZAR1 underwent strong negative selection, as illustrated by the low ratio of dN/dS (dN/dS = 0.200) and the high proportion (56.5%) of negatively selected sites. It follows that ZAR1 evolved slowly due to strong functional constraints. The lack of positive selection is also consistent with the mode of effector-recognition by ZAR1, which relies on the diversity of ZRKs and PBL proteins. In contrast, ZRKs appear to have evolved by the birth and death process, leading to variable copy numbers of ZRKs in different angiosperm species. Different regions in ZRKs evolved in contrasting modes: the sites on the interaction interface with ZAR1 are highly conserved, but the sites on the interaction interface with PBL2 are highly variable (Supplemental Figure S2, C and D). These evolutionary patterns again suggest that ZAR1 has been maintaining associations with ZRKs and that ZRKs are free to diversify to recognize different decoys/guardees. Indeed, our analyses showed that AtPBL2 was likely recruited into the ZAR1 resistosome only in relatively recent times.

We did not identify the presence of ZAR1 or ZRKs in many angiosperm species. The resistosome as a whole has been lost tens of times during the evolution of angiosperms, strongly supporting the notion that ZAR1s and ZRKs coevolved with each other across angiosperms and assembled into resistosomes (Figure 9). However, no such concerted loss was observed between ZAR1-sis and ZRKs or between ZAR-basal and ZRKs. The notion that ZAR1 and ZRKs coevolved is also consistent with the observed compatibility between ZAR1 and ZRKs within the species. Accompanying the loss of the ZAR1 gene, the loss of ZRKs took place coordinately, even though ZRKs from a plant species might cluster into multiple distinct ZRK lineages. The pervasive loss of the ZAR1 resistosome might be related to the everchanging pathogen burden in angiosperms. Although ZRKs diversified to recognize a number of effectors, ∼60% of P. syringae isolates are not recognized by AtZAR1 in the Col-0 ecotype (Laflamme et al., 2020). Thus, we propose a possible explanation for the recurrent losses of the ZAR1 resistosome. In the absence of pathogens carrying cognate effectors, the functional constraint on the ZAR1 and ZRK genes is relaxed, and/or the presence of the ZAR1 resistosome is costly (Tian et al., 2003; Karasov et al., 2014), which might eventually lead to the loss of the ZAR1 resistosome.

Figure 9.

Evolutionary model of the ZAR1 resistosome. The plant phylogeny is based on the literature (Zeng et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes, 2019). The circles with slashes on the branches represent the loss events of ZAR1 or ZRK proteins. Red dotted box (Event 1) represents the possible evolutionary scenario for the origin of the ZAR1 resistosome. ZAR1 originated through a duplication in the common ancestor of eudicots and monocots, and ZRKs originated from WAKs through the loss of the extracellular domain before the split of eudicots and monocots. ZAR1s were then associated with ZRKs during the early evolution of angiosperms, forming the ZAR1 resistosome. In the blue dotted box (Event 2), ZRK experienced amplification and diversification during the course of angiosperm evolution to recognize various decoys/guardees, including AtPBL2.

Our results show that ZRKs originated from WAKs through the loss of extracellular domains. WAKs are PRRs that have been known to recognize pectin and oligogalacturonides and participate in resistance to multiple pathogens, including Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, Sporisorium reilianum, and Exserohilum turcicum (Brutus et al., 2010; Hurni et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017). It follows that the ZAR1-mediated resistosome might have evolved partially from pre-existing PTI signaling modules. Taken together, our study illuminates how a new plant immune surveillance network originated via tinkering with pre-existing immunity-related proteins and modules.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The A. thaliana plants used in this study include Col-0, zar1-1, pbl2, and pbl2 transgenic lines complemented with various mutants (Lewis et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). The N. benthamiana plants used were WT and the zar1-1 mutant, provided by Brian Staskawicz (University of California, Berkeley). The plants were grown in soil at 23°C under a 10/14-h light/dark photoperiod with white light (90 μE m−2s−1). The fresh leaves were harvested from adult plants of P. trichocarpa, P. persica, and L. chinense grown in Beijing Botanical Garden (Beijing, China). The tomato (S. lycopersicum) cultivar M82 was provided by Professor Cao Xu (Chinese Academy of Sciences). The cotton (G. hirsutum) was provided by Dr. Yiqin Wang (Chinese Academy of Sciences). The A. coerulea was a gift from Professor Guixia Xu (Chinese Academy of Sciences). The C. clementina was gathered from National Citrus Engineering and Technology Research Center, Citrus Research Institute, Southwest University. The taro (C. esculenta) was collected in Jiangsu, China. The C. demersum plants were obtained from Fujian, China.

Identification of ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins

To investigate the distribution and evolution of ZAR1 resistosome components across plants, we conducted similarity searches combined with phylogenetic analyses within 72 representative plant species (Supplemental Data Set 1). First, we used the BLASTp algorithm to search against plant proteomes with the NB-ARC domain sequence of AtZAR1 (the Arabidopsis ZAR1) and the kinase domain sequence of AtRKS1 (the Arabidopsis RKS1) as the queries and an e cut-off value of 10−5. The significant hits of AtZAR1 were retrieved and aligned with all the NB-ARC domain sequences of Arabidopsis NLRs using HMMER (Eddy, 1998; Gao et al., 2018). The significant hits of AtRKS1 were retrieved and aligned with all the kinase domain sequences of representative RLKs and eukaryotic kinases using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013; Gong and Han, 2021). The alignments were refined by trimAl and manually edited (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009). Large-scale phylogenetic analyses were performed using an approximate maximum likelihood method implemented in FastTree (Price et al., 2010). Significant hits that clustered with AtZAR1 and AtZRKs were retrieved as ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins (Supplemental Data Sets 2 and 3). To confirm the absence of ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins in some angiosperms, we used the tBLASTn algorithm to search against their genomes and performed phylogenetic analyses as described above. The domain organization of each protein was annotated by CD-Search, and the transmembrane region was predicted by TMHMM server version 2.0 (Krogh et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2020). Seven ZAR1-related proteins with integrated domains might be annotation errors, with no RNA-seq reads from the Sequence Read Archive spanning the junctions between ZAR1s and integrated domains, and were reannotated based on RNA-seq and genomic data.

Phylogenetic analysis

To explore the evolutionary relationships among ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins, we reconstructed phylogenetic trees of ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins. Notably, among the 83 ZAR1-related genes identified here, we found only ten genes with alternative isoforms: eight are identical coding regions, and the remaining two were found to be misannotated and were not supported by transcriptome data. Isoforms did not affect our analyses. The ZAR1-related proteins and representative NLRs were aligned using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The kinase domain sequences of the ZRK-related proteins, WAKs closely related to ZRKs, and other representative RLKs and eukaryotic protein kinases (ePKs) were aligned using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The representative NLRs and RLKs were selected based on the aforementioned large-scale phylogenetic trees. The alignments were refined using trimAl and manually edited (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the maximum likelihood method implemented in IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al., 2015). The ModelFinder algorithm was used to choose the best-fit substitution model (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). Supports for the nodes were assessed using the UFBoot approach with 1,000 replicates (Hoang et al., 2018). Phylogenetic trees were annotated using iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2019).

Selection analysis of ZAR1-related proteins

To assess selection pressure and functional constraints on different ZAR1-related groups, we estimated dN/dS ratios for the ZAR1, ZAR1-sis, and ZAR1-basal groups. For these three ZAR1 related groups, coding regions were retrieved with incomplete gene sequences excluded. A total of 28 ZAR1 sequences, 23 ZAR1-sis sequences, and 10 ZAR1-basal sequences were used. Coding regions were aligned based on codons using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using the maximum likelihood method implemented in IQ-TREE (Hoang et al., 2018). The overall dN/dS ratios and sites subject to negative and positive selection were inferred using the FEL method implemented in the HyPhy with a P-value of 0.05 (Kosakovsky Pond and Frost, 2005; Pond et al., 2005; Delport et al., 2010).

Conservation analysis

Sequences of ZAR1- and ZRK-related proteins were aligned using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Logo plots of conserved sites in proteins with intact domain organizations were generated using weblogo (Crooks et al., 2004). Shannon’s entropy scores were calculated using Bio3d in R version 4.0.5, according to the H.10 criteria, in which 22 amino acid residues are classified into 10 types (Grant et al., 2006). Sites with <50% coverage were excluded, and 15, 11, and 12 sites crucial for AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interactions were used for the ZAR1, ZAR1-sis, and ZAR1-basal group, respectively. Twenty three N-terminal sites were used for all three groups. The conservation patterns of the AtZAR1–AtRKS1 interaction interfaces on the 3D structures of ZAR1-related proteins were illustrated based on the ConSurf conservation scores (Ashkenazy et al., 2016). The 3D structures of ZAR1-sis (Potri.006G014400) and ZAR1-basal (RWR85656.1) were predicted by SWISS-MODEL using the structure of AtZAR1 (6j5w) as the modeling template (Waterhouse et al., 2018).

To compare the conservation patterns between AtZRKs and AtWAKs, AtWAKs were aligned with AtRKS1 using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Logo plots of conserved sites involved in ZAR1 resistosome function and kinase catalytic motifs were generated using weblogo (Crooks et al., 2004). Eighteen ZAR1 proteins tested in functional analyses were aligned using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT as well (Katoh and Standley, 2013).

Evolutionary analysis of PBL2-related proteins

We used the BLASTp algorithm to search against 72 representative plant proteomes (Supplemental Data Set 1) with the kinase domain sequence of AtPBL2 (the Arabidopsis PBL2) as the query and an e-value of 10−5. Significant hits were retrieved and aligned with the kinase domain sequences of Arabidopsis RLKs and representative eukaryotic kinases (Gong and Han, 2021) using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The alignment was refined using trimAl and manually edited (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009). Large-scale phylogenetic analysis was performed using the approximate maximum likelihood method implemented in FastTree (Price et al., 2010). Significant hits that cluster with Arabidopsis RLCK-VII-9 proteins (AtPBL2, AtPBL3, AtPBL4, AtPBL18) and AtPBL29 were retrieved and aligned with other Arabidopsis PBLs and representative Arabidopsis RLKs (Rao et al., 2018) using the L-INS-I strategy in MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The alignment was refined using trimAl and manually edited (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009). The phylogenetic tree of PBLs was reconstructed by the maximum likelihood method implemented in IQ-TREE with 1,000 UFBoot replicates (Hoang et al., 2018).

Plasmid constructs and transgenic plants

The genes cloned in this study were as follows: LcZAR1 (Lchi14298), LcZAR1-basal (Lchi31637), LcZRK (Lchi34311), SlZAR1 (Solyc02g084890), SlZAR1-sis-1 (Solyc07g053010), SlZAR1-sis-2 (Solyc07g053020), SlZRK (Solyc06g060690), CeZAR1 (EVM0019281), CeZRK (EVM0023206), AcZAR1 (Aqcoe7G345700), AcZAR1-sis (Aqcoe4G246100), AcZRK (Aqcoe5G242100), PtZAR1 (Potri.005G119800), PtZAR1-sis (Potri.006G014400), PtZRK (Potri.002G004900), PpZAR1 (Prupe.7G160100), PpZAR1-sis (Prupe.4G009300), PpZRK (Prupe.8G149400), CdZAR1 (prefix07885), CdZRK (prefix07886), CcZAR1 (Ciclev10024885m.g), CcZAR1-sis (Ciclev10023333m.g), CcZRK (Ciclev10005345m.g), GhZAR1 (D12G006440.1), GhZAR1-sis (A01G071500.1), and GhZRK (D03G004890.1). To generate constructs for protoplast transfection, the full-length cDNA fragments were amplified by RT-PCR with primers designed based on the end sequences (Supplemental Data Set 4) and subsequently cloned into the cloning vector pUC19-35S-HA-RBS with KpnI/SalI sites or pUC19-35S-FLAG-RBS with XhoI/BstBI sites using a ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (no. C112; Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China).

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 was used for transient gene expression. Bacterial cells were suspended with the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 and infiltrated into expanding leaves of 4-week-old N. benthamiana.

Arabidopsis pbl2 plants were transformed with ProPBL2:PBL2-HA using the floral dip method. Transgenic plants were identified by immunoblot analysis for transgene expression. Total protein was extracted from young leaves of transgenic plants with protein extraction buffer (50-mM 4-[2-hydroxyethyl]-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) [pH 7.5], 150-mM KCl, 1-mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.5% Triton X-100, 1-mM dithiothreitol (DTT), protease inhibitor cocktail). Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Total protein was separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) gel and detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibodies (TianGen, Cat#CW0092m, dilution: 1:3,000).

co-IP assay

For the co-IP assay, isolation and transformation of Arabidopsis protoplasts were performed as previously described (He et al., 2007). After incubation for 12 h, the protoplasts were harvested and resuspended in protein extraction buffer (50-mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150-mM KCl, 1-mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1-mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail). Total protein extracts were incubated with 50-μL anti-FLAG M2 agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 3 h at 4°C. The agarose was washed 6 times with protein extraction buffer (50-mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150-mM KCl, 1-mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1-mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail) and eluted with 60-μL of 0.5-mg/mL 3 × FLAG peptide (Sigma) for 1 h at 4°C. Proteins were separated on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma; Cat#F3165, dilution: 1:5,000) or anti-HA antibodies (TianGen, Cat#CW0092m, dilution: 1:3,000).

Blue native PAGE assay

BN-PAGE was performed using the Bis–Tris Native PAGE system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as previously described (Hu et al., 2020).

Membrane fractionation assays

Membrane fractionation assays were performed using a PM Protein Isolation Kit for Plants (Invent, SM-005-P) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, protoplasts expressing the indicated plasmids were incubated for 12 h and homogenized in 300 μL buffer A. After incubation for 5 min on ice, the homogenates were transferred onto a filter cartridge and centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 30 s at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended as the total protein for partitioning. Total protein was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 1 min at 4°C. The pellet contained nuclei and larger debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh 1.5-mL microfuge tube and centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 40 min at 4°C to separate the new supernatant (the cytosolic fraction) and pellet fractions (the total membrane fraction including the organelle membrane and PM). The membrane fraction was resuspended in 200-μL buffer B and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to separate the supernatant and pellet fractions (the organelle membrane fraction). The supernatant was suspended in 1.6-mL cold PBS and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet containing the PM fraction was dissolved in protein extraction buffer. The proteins were separated on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel and detected by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma; Cat#F3165, dilution: 1:5,000) or anti-UGPase antibodies (Agrisera, Cat#AS05086, dilution: 1:5,000).

Protoplast viability assay

All the genes were cloned into pUC19-35S-HA-RBS with KpnI/SalI sites or pUC19-35S-FLAG-RBS with XhoI/BstBI sites for protoplast transfection. The Arabidopsis protoplasts expressing the indicated constructs were incubated for 12 h, and cell viability was determined using the Cell Titer-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, G7570) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay is a homogeneous method to determine the number of viable protoplasts based on the amount of ATP, which signals the presence of metabolically active cells. ATP-based luminescence intensity in viable cells was recorded by an EnSpire Multimode plate Reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The percentage of cell survival was calculated, and the cell viability of mock control cells was set as 100%.

Bacterial strains and inoculations

The bacterial strains X. campestris pv. campestris carrying or lacking avrAC were suspended to 5 × 108 colony-forming units/milliliter. Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants were wound-inoculated in the main leaf vein. Disease symptoms were scored at 7 days after inoculation.

Statistical analysis

For the protoplast viability assays, data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism version 8.0 software (https://www.graphpad.com/). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-test (Supplemental Data Set 5). The statistical significance for pairwise difference of Shannon’s entropy scores among three ZAR1-related groups was determined using Wilcoxon test.

Accession numbers

The sequences of the genes cloned in this study were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: LcZAR1 (MZ322967), LcZAR1-basal (MZ322968), LcZRK (MZ322969), SlZAR1 (MZ322970), SlZAR1-sis-1 (MZ322971), SlZAR1-sis-2 (MZ322972), SlZRK (MZ322973), CeZAR1 (MZ322974), CeZRK (MZ322975), AcZAR1 (MZ322976), AcZAR1-sis (MZ322977), AcZRK (MZ322978), PtZAR1 (MZ322979), PtZAR1-sis (MZ322980), PtZRK (MZ322981), PpZAR1 (MZ322982), PpZAR1-sis (MZ322983), PpZRK (MZ322984), CdZAR1 (MZ322985), CdZRK (MZ322986), CcZAR1 (MZ322987), CcZAR1-sis (MZ322988), CcZRK (MZ322989), GhZAR1 (MZ322990), GhZAR1-sis (MZ322991), GhZRK (MZ322992). The accession numbers of Arabidopsis genes are as following: AtZAR1 (TAIR: AT3G50950), AtRKS1 (TAIR: AT3G57710), AtZED1 (TAIR: AT3G57750), AtPBL2 (TAIR: AT1G14370), AtPBL3 (TAIR: AT2G02800), AtWAK3 (TAIR: AT1G21240).

Resources of all plant genomes analyzed in this study are available in Supplemental Data Set 1. The datasets generated in this study, including all alignment files used for phylogenetic analyses and phylogenetic tree files, are available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3n3stnvzyk/draft?a=40c6c5dd-ddb3-48d0-8be0-864e67dae519.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Conservation patterns of ZAR1-related proteins.

Supplemental Figure S2. Evolutionary patterns of ZRK-related proteins.

Supplemental Figure S3. Functional analysis of ZAR1 orthologs and paralogs.

Supplemental Figure S4. Functional analysis of ZRK-related proteins.

Supplemental Figure S5. PM association analysis of ZAR1-related proteins.

Supplemental Figure S6. Phylogenetic analysis of PBL2-related proteins.

Supplemental Figure S7. Functional analysis of AtPBL2/AtPBL3 proteins.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Information about the genomes used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 2. Domain architectures of ZAR1-related proteins identified in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 3. Domain architectures of ZRK-related proteins identified in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 4. Primer sequences used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 5. ANOVA results.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31922001 to G.Z.H. and 31521001 to J.M.Z.).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Zhen Gong, College of Life Sciences, Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Microbes and Functional Genomics, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210023, China.

Jinfeng Qi, State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Innovation Academy for Seed Design, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China.

Meijuan Hu, State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Innovation Academy for Seed Design, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China.

Guozhi Bi, State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Innovation Academy for Seed Design, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China.

Jian-Min Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Innovation Academy for Seed Design, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100101, China; CAS Center for Excellence in Biotic Interactions, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China.

Guan-Zhu Han, College of Life Sciences, Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Microbes and Functional Genomics, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210023, China.

G.Z.H. and J.M.Z. conceptualized the work. Z.G. and G.Z.H. conducted evolutionary analyses. J.Q. performed the majority of experiments. M.H. and G.B. contributed to part of the cell death and protein analyses. Z.G., J.Q., J.M.Z., and G.Z.H. wrote the article.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plcell) are: Jian-Min Zhou (jmzhou@genetics.ac.cn) and Guan-Zhu Han (guanzhu@njnu.edu.cn).

References

- Adachi H, Sakai T, Kourelis J, Hernandez JLG, Maqbool A, Kamoun S (2021) Jurassic NLR: conserved and dynamic evolutionary features of the atypically ancient immune receptor ZAR1. bioRxiv, doi: 2020.2010.2012.333484 (December 12, 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amborella Genome P (2013) The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342: 1241089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antolin-Llovera M, Ried MK, Binder A, Parniske M (2012) Receptor kinase signaling pathways in plant-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol 50: 451–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazy H, Abadi S, Martz E, Chay O, Mayrose I, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N (2016) ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res 44: W344–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin M, Hassan JA, Schreiber KJ, Lewis JD (2017) Analysis of the ZAR1 immune complex reveals determinants for immunity and molecular interactions. Plant Physiol 174: 2038–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilstein MA, Nagalingum NS, Clements MD, Manchester SR, Mathews S (2010) Dated molecular phylogenies indicate a Miocene origin for Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18724–18728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G, Su M, Li N, Liang Y, Dang S, Xu J, Hu M, Wang J, Zou M, Deng Y, et al. (2021) The ZAR1 resistosome is a calcium-permeable channel triggering plant immune signaling. Cell 184: 3528–3541.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies K, Weigel D (2007) Hybrid necrosis: autoimmunity as a potential gene-flow barrier in plant species. Nat Rev Genet 8: 382–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutus A, Sicilia F, Macone A, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G (2010) A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 9452–9457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T (2009) trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25: 1972–1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JW, Donoghue PCJ (2018) Whole-genome duplication and plant macroevolution. Trends Plant Sci 23: 933–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14: 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet R, Adams KL, Vandepoele K, Van Montagu MC, Maere S, Van de Peer Y (2013) Convergent gene loss following gene and genome duplications creates single-copy families in flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 2898–2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delport W, Poon AF, Frost SD, Kosakovsky Pond SL (2010) Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics 26: 2455–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou D, Zhou JM (2012) Phytopathogen effectors subverting host immunity: different foes, similar battleground. Cell Host Microbe 12: 484–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR (1998) Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14: 755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F, Yang F, Rong W, Wu X, Zhang J, Chen S, He C, Zhou JM (2012) A Xanthomonas uridine 5'-monophosphate transferase inhibits plant immune kinases. Nature 485: 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CSP, Sauquet H, van der Merwe M, McPherson H, Rossetto M, Ho SYW (2017) Evaluating the impact of genomic data and priors on bayesian estimates of the angiosperm evolutionary timescale. Syst Biol 66: 338–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wang W, Zhang T, Gong Z, Zhao H, Han GZ (2018) Out of water: the origin and early diversification of plant R-genes. Plant Physiol 177: 82–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Han GZ (2021) Flourishing in water: the early evolution and diversification of plant receptor-like kinases. Plant J 106: 174–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BJ, Rodrigues AP, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, Caves LS (2006) Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics 22: 2695–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy E, Lautier M, Chabannes M, Roux B, Lauber E, Arlat M, Noel LD (2013) xopAC-triggered immunity against Xanthomonas depends on Arabidopsis receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase genes PBL2 and RIPK. PLoS One 8: e73469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han GZ (2019) Origin and evolution of the plant immune system. New Phytol 222: 70–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Shan L, Sheen J (2007) The use of protoplasts to study innate immune responses. Methods Mol Biol 354: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS (2018) UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol 35: 518–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Cao J, Zhang J, Xia F, Ke Y, Zhang H, Xie W, Liu H, Cui Y, Cao Y, et al. (2017) Improvement of multiple agronomic traits by a disease resistance gene via cell wall reinforcement. Nat Plants 3: 17009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Qi J, Bi G, Zhou JM (2020) Bacterial effectors induce oligomerization of immune receptor ZAR1 in vivo. Mol Plant 13: 793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurni S, Scheuermann D, Krattinger SG, Kessel B, Wicker T, Herren G, Fitze MN, Breen J, Presterl T, Ouzunova M, et al. (2015) The maize disease resistance gene Htn1 against northern corn leaf blight encodes a wall-associated receptor-like kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 8780–8785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F (1977) Evolution and tinkering. Science 196: 1161–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS (2017) ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 14: 587–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasov TL, Kniskern JM, Gao L, DeYoung BJ, Ding J, Dubiella U, Lastra RO, Nallu S, Roux F, Innes RW, et al. (2014).The long-term maintenance of a resistance polymorphism through diffuse interactions. Nature 512: 436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD (2005) Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol 22: 1208–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305: 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon A, Scott S, Taujale R, Yeung W, Kochut KJ, Eyers PA, Kannan N (2019) Tracing the origin and evolution of pseudokinases across the tree of life. Sci Signal 12: eaav3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme B, Dillon MM, Martel A, Almeida RND, Desveaux D, Guttman DS (2020) The pan-genome effector-triggered immunity landscape of a host-pathogen interaction. Science 367: 763–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P (2019) Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res 47: W256–W259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Lee AH, Hassan JA, Wan J, Hurley B, Jhingree JR, Wang PW, Lo T, Youn JY, Guttman DS, et al. (2013) The Arabidopsis ZED1 pseudokinase is required for ZAR1-mediated immunity induced by the Pseudomonas syringae type III effector HopZ1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 18722–18727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Wu R, Guttman DS, Desveaux D (2010) Allele-specific virulence attenuation of the Pseudomonas syringae HopZ1a type III effector via the Arabidopsis ZAR1 resistance protein. PLoS Genet 6: e1000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Yi TS, Gao LM, Ma PF, Zhang T, Yang JB, Gitzendanner MA, Fritsch PW, Cai J, Luo Y, et al. (2019) Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat Plants 5: 461–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Weigel D (2021) One hundred years of hybrid necrosis: hybrid autoimmunity as a window into the mechanisms and evolution of plant-pathogen interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol 12: eaav3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]