Abstract

Human–animal interaction research is growing in popularity and methodological rigor; however, there remains a need for psychometrically validated measures and inclusion of broader populations. This study addressed these gaps by reporting on the psychometric properties of the Comfort from Companion Animals Scale (CCAS) in a sample of sexual and gender minority emerging adults. Participants included 138 emerging adults between the ages of 18–21 years (M = 19.33 years, SD = 1.11; 38.4% racial/ethnic minority) who identified as a gender (48.6%) and/or sexual minority (98.6%) and who reported living with a companion animal in the past year. We utilized the following analytic methods: (a) confirmatory factor analyses to compare the unidimensional structure of the CCAS with the two alternative models, (b) multiple group analyses to test measurement invariance across demographic groups, and (c) structural equation models to evaluate construct validity. Preliminary analysis found that the majority of participants did not endorse the two lowest response options. To conduct invariance testing, we eliminated items 3, 5, and 8 from the CCAS and collapsed the lowest response options. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis supported the use of this revised unidimensional model. We found evidence of measurement invariance across gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity groups. Construct validity was supported by comparing the CCAS with factors on the Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale; the positive association between the CCAS and anxiety are discussed in the context of prior research. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of validating human–animal interaction measures across samples from diverse backgrounds. We recommend that future studies continue to test the CCAS and other measures of human–animal attachment among diverse samples to delineate which aspects of human–animal interaction may be most beneficial in promoting mental health in vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Attachment, emotional comfort, human–animal bond, human–animal interaction, LGBTQ, measurement

The role that companion animals may play in promoting human health and wellbeing is gaining increased attention due, in part, to the burgeoning field of human–animal interaction (HAI) science. Although the field of HAI continues to grow and advance in methodological rigor, there is significant need for valid instruments that can reliably measure the quality and characteristics of human–animal relationships and interactions across population groups. Multiple scholars have argued that the paucity of measures that have undergone extensive psychometric testing is a barrier to advancing the rigor of HAI science as it limits meaningful comparisons of outcomes across studies (Bures et al., 2019; Esposito et al., 2011; McCune et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2018). This limitation, combined with low rates of inclusion of minority populations in HAI research to date, severely limits our ability to understand under what conditions and for whom HAI can offer the greatest public health benefits. The current study addresses this gap by examining the psychometric properties of the Comfort from Companion Animals Scale (CCAS; Zasloff, 1996) in a diverse sample of sexual and gender minority (SGM) emerging adults. In this study, the term sexual minority refers to those whose sexual orientation does not align with, or falls outside the scope of, the dominant culture of heteronormative sexuality (e.g., lesbian, gay, pansexual, bisexual, asexual, and queer-identified people); gender minority refers to individuals whose gender identity and/or expression is different, or may be perceived as different, than the biological sex they were assigned at birth (e.g., transgender, non-binary, gender expansive, gender queer-identified people; Schrager et al., 2019).

SGM Emerging Adults and Companion Animals

Emerging adulthood (i.e., approximately ages 18–29 years) is a particularly important developmental period that involves instability, increases in autonomy, and identity exploration (Arnett et al., 2014). Approximately 30% of emerging adults (ages 18–24) identify as an SGM (Flores et al., 2016; The Williams Institute, 2019). In addition to the stressors associated with this developmental period, SGM emerging adults experience additional risk for SGM-related stressors, such as family and/or peer rejection and difficulty securing employment and/or housing, that can contribute to increased risk for suicidal ideation, substance use, and mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Eisenberg et al., 2017; Johns et al., 2019; Meyer, 2003; Newcomb et al., 2012).

Social support and emotional comfort are important factors that promote SGM emerging adults’ identity development and mental health (Doan Van et al., 2019; Ehlke et al., 2020; McDonald, 2018; Vaccaro & Mena, 2011). Evidence suggests that companion animals can provide a source of social support and emotional comfort; therefore, it is not surprising that estimates suggest that SGM adults may have higher rates (67–78%) of companion animal ownership than cisgender and heterosexual adults (Community Marketing & Insights, 2019; Falkner & Garber, 2002; Harris Interactive, 2010). For example, SGM adults have reported in qualitative studies that their pets provide companionship, emotional comfort, and assistance with coping with stress and mental health (Putney, 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2020; Schmitz et al., 2021). Additionally, Riggs et al. (2018) found that pet ownership buffered the relation between family victimization and psychological stress, and McDonald, Murphy, et al. (2021) found evidence of an indirect effect between exposure to SGM-related microaggressions and greater personal hardiness (i.e., interpersonal resilience) via HAI.

Due to the additional stressors SGM individuals experience (Frost et al., 2014; Morse et al., 2019), their relationships with companion animals may manifest differently compared with their non-SGM peers, particularly during emerging adulthood when they encounter a variety of new heteronormative social contexts, such as living with roommates, attending college, and navigating employment (Pachana et al. 2011; Piper & Uttley, 2019; Wagaman et al., 2014). Therefore, a priority of HAI science should be to evaluate commonly used HAI instruments in SGM emerging adult populations. To do so, this requires that researchers ensure that scales perform similarly across demographic groups, such as sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. Failing to do so may result in test bias (i.e., when the measure does not equivalently assess the construct in a new population compared with the original population in which it was normed), which makes interpreting differences in scores difficult as those differences may be due to measurement error instead of true differences on the construct of interest. One method of testing how a measure performs across populations is to explore the psychometric properties of the measure within each additional group (Cooper et al., 2017).

Assessment of Emotional Comfort from Companion Animals

Emotional comfort derived from companion animals may be a particularly important construct to measure, due to the role of pets in coping with minority stress (Matijczak et al., 2021; McDonald, Matijczak, et al., 2021; McDonald, O’Connor, et al., 2021). Emotional comfort has been defined as a feeling of relaxation and overall positive feelings that is often perceived as therapeutic (Williams et al., 2017). This construct predominantly appears in nursing-related literature, and it has been linked to improved physical comfort, recovery, and psychological wellbeing (i.e., anxiety, depression scores) within hospitalized populations (Sun et al., 2021; Williams & Irurita, 2005, 2006). Within the HAI context, the construct of emotional comfort is often linked to attachment bonds with pets. Although human secure attachment relationships are characterized by the attachment figure providing comfort during times of distress (Bowlby, 1983), this is just one aspect of an attachment relationship. Human attachment bonds and human–animal attachment bonds are also argued to be unique constructs (Crawford et al., 2006). Therefore, it is important to tease apart the specific aspects of HAI, such as emotional comfort versus attachment, that promote mental health, particularly among vulnerable populations with reduced access to supportive human relationships (e.g., SGM individuals) and during developmental transitions characterized by increased stress (e.g., emerging adulthood).

Currently, based on our search of the literature and a 2012 systematic review by Wilson and Netting, only five published measures of human–companion animal relationships have been intentionally designed to assess emotional comfort derived from companion animals or an individual’s emotional bond with the pet (i.e., Contemporary Companion Animal Bonding Scale, Triebenbacher, 1999; Monash Dog Ownership Relationship Scale, Dwyer et al., 2006; Pet/Friend Q Sort, Davis, 1987; Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale, Cromer & Barlow, 2013; Comfort from Companion Animals Scale, Zasloff, 1996). However, to date, the Comfort from Companion Animals Scale (CCAS; Zasloff, 1996) remains the only English-language measure designed solely to assess emotional comfort received from companion animals, instead of a broader construct such as emotional bond or attachment.

Comfort from Companion Animals Scale

The CCAS has been included as an instrument in 20 studies since it was published in 1996. Across studies, participants’ scores on the CCAS correlated with scores on other measures assessing relationships with companion animals (e.g., Blazina & Bartone, 2016; Loven, 2005; Zilcha-Mano et al., 2011), measures of perceived stress (le Roux & Wright, 2020), and life satisfaction and mood (Luhmann & Kalitzki, 2018). Out of the 12 peer-reviewed studies using the CCAS, only eight of those reported psychometric properties of the measure (e.g., Blazina & Bartone, 2016; Schofield, 2003). However, these studies solely report on reliability of the scale, which does not provide sufficient evidence of internal consistency or unidimensionality (Sijtsma, 2009; Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016).

Another limitation of prior studies utilizing the CCAS concerns emerging evidence of sex/gender, racial/ethnic, and developmental differences in HAI (Mueller, 2014; Piper & Uttley, 2019; Risley-Curtiss et al., 2006; Saunders et al., 2017). A majority of HAI studies to date, including those using the CCAS, have not examined measurement invariance of HAI constructs across developmental periods or contemporary identity groups. Only five studies utilizing the CCAS examined differences across sex and/or gender groups, five studies explored age differences in scores, and only four studies examined differences across racial/ethnic groups. Despite some studies finding significant differences in CCAS scores between these demographic groups (e.g., le Roux & Wright, 2020; Tardif-Williams & Bosacki, 2015), no study to date has examined measurement invariance of the CCAS across demographic variables. Generally, these studies show that researchers continue to utilize the CCAS mean score to explore relations with other outcomes of interest under the potentially false assumption that the measure functions similarly across demographic groups (e.g., sex/gender, race/ethnicity, age). Moreover, to our knowledge, all previous studies examining measurement invariance of HAI constructs across gender and/or sex groups have relied on assumptions that these are binary identities and have failed to include or acknowledge other identities (e.g., non-binary, transgender, intersex). This is a concerning limitation of HAI science as approximately 1.4 million adults in the United States identify as a gender minority with identities that are expansive and do not fall within binary categories of gender and/or sex (Flores et al., 2016).

Current Study

In this study, we addressed several gaps in the literature on HAI measurement by evaluating the psychometric properties of the CCAS within a sample of SGM young adults. Specifically, we tested competing factor structures of the CCAS (see Table 1), comparing the unidimensional model with alternative 2- and 3-factor models informed by item sets on the Contemporary Companion Animal Bonding Scale (i.e., emotional bond, physical proximity; Triebenbacher, 1999) and My Pet Inventory (i.e., nurturance, satisfaction; Furman, 1989). We hypothesized that the unidimensional model representing emotional comfort derived from companion animals would fit our data best. Once we found the best-fitting model of the CCAS, we tested measurement invariance across sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. We also examined relations between the CCAS and attachment to companion animals to evaluate construct validity, hypothesizing that the scores on the CCAS would be positively correlated with similar instruments measuring attachment to companion animals. Additionally, we tested a structural equation model to examine relations between the CCAS and psychological stress as an additional test of validity. Based on prior findings that pet ownership is both positively (Barker et al., 2020; Matijczak et al., 2021; McDonald, O’Connor, et al., 2021) and negatively associated with psychological stress (le Roux Wright, 2020; Rhoades et al., 2015; Riggs et al., 2018), we considered this analysis exploratory and did not have a priori hypotheses.

Table 1.

CCAS items and alternative factor models.

| Model | Factor | 11-item CCAS (Zasloff, 1996) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of items | Items included | ||

|

| |||

| Unidimensional model | Emotional comfort | 11 | 1. My pet provides me with companionship. 2. Having a pet gives me something to care for. 3. My pet provides me with pleasurable activity.a 4. My pet is a source of constancy in my life. 5. My pet makes me feel needed.a 6. My pet makes me play and laugh. 7. Having a pet gives me something to love. 8. I get comfort from touching my pet.a 9. I enjoy watching my pet. 10. My pet makes me feel loved. 11. My pet makes me feel trusted. |

|

| |||

| 2 factor model | Emotional bond | 7 | 1. My pet provides me with companionship. |

| 4. My pet is a source of constancy in my life. | |||

| 5. My pet makes me feel needed. | |||

| 7. Having a pet gives me something to love. | |||

| 8. I get comfort from touching my pet. | |||

| 10. My pet makes me feel loved. | |||

| 11. My pet makes me feel trusted. | |||

| Physical proximity | 4 | 2. Having a pet gives me something to care for. | |

| 3. My pet provides me with pleasurable activity. | |||

| 6. My pet makes me play and laugh. | |||

| 9. I enjoy watching my pet. | |||

|

| |||

| 3 factor model | Comfort | 4 | 1. My pet provides me with companionship. |

| 4. My pet is a source of constancy in my life. | |||

| 8. I get comfort from touching my pet. | |||

| 11. My pet makes me feel trusted. | |||

| Nurturance | 4 | 2. Having a pet gives me something to care for. | |

| 5. My pet makes me feel needed. | |||

| 7. Having a pet gives me something to love. | |||

| 10. My pet makes me feel loved. | |||

| Satisfaction | 3 | 3. My pet provides me with pleasurable activity. | |

| 6. My pet makes me play and laugh. | |||

| 9. I enjoy watching my pet. | |||

Item deleted.

Methods

Participant Recruitment and Sample Selection

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study that focused on SGM youths’ experiences of stressors and supports. Participants of the overarching study included youth between the ages of 15 and 21 who self-identified as a SGM and communicated by spoken English. Due to our interest in the emerging adulthood period and the limited number of adolescent participants (n = 4), the current study restricted analyses to emerging adult participants between the ages of 18–21 years (M = 19.33, SD = 1.11) who reported having lived with at least one companion animal in the past year (n = 138). Participants identified with various gender identities and sexual orientations: 48.6% self-reported a gender minority identity (e.g., transgender, non-binary) and 98.6% self-identified as a sexual minority (e.g., lesbian, gay). Approximately 97% of our sample reported having lived with a dog and/or a cat in the past year (only four participants reported exclusively living with other types of companion animals, such as fish and rodents). Additional participant demographic information is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant demographics (n = 138).

| Variable name | Variable categories | n | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | Arab/Arab American | 1 | 0.7 | |||

| Asian/Asian American | 3 | 2.2 | ||||

| Black/African American | 20 | 14.5 | ||||

| Latina/Latino/Latinx | 8 | 5.8 | ||||

| Multiracial/Mixed Race | 19 | 13.8 | ||||

| South Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.7 | ||||

| White | 85 | 61.6 | ||||

| Prefer to self-describe | 1 | 0.7 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Gender Identity | Agender | 4 | 2.9 | |||

| Cisgender man | 10 | 7.2 | ||||

| Cisgender woman | 61 | 44.2 | ||||

| Genderfluid | 2 | 1.4 | ||||

| Genderqueer | 5 | 3.6 | ||||

| Nonbinary | 11 | 8.0 | ||||

| Transgender man | 16 | 11.6 | ||||

| Transgender woman | 2 | 1.4 | ||||

| Not sure/questioning/prefer to self-describe | 6 | 4.3 | ||||

| Identified with multiple categories | 21 | 15.2 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Sexual Orientation | Asexual | 2 | 1.4 | |||

| Bisexual | 31 | 22.5 | ||||

| Demisexual | 1 | 0.7 | ||||

| Gay | 11 | 8.0 | ||||

| Lesbian | 18 | 13.0 | ||||

| Pansexual | 13 | 9.4 | ||||

| Queer | 19 | 13.8 | ||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 2 | 1.4 | ||||

| Identified with multiple categories | 41 | 29.7 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Pet Type a | Lived with | Primary caretakerb | Consider pet family memberb | |||

|

| ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||||

| Bird | 3 | 2.2 | 3 | 100.0 | 3 | 100.0 |

| Cat | 80 | 58.0 | 40 | 50.0 | 75 | 93.8 |

| Dog | 90 | 65.2 | 27 | 30.0 | 88 | 97.8 |

| Fish | 11 | 8.0 | 10 | 90.9 | 6 | 54.5 |

| Lagomorph | 9 | 6.5 | 4 | 44.4 | 8 | 88.9 |

| Reptile | 5 | 3.6 | 4 | 80.0 | 3 | 60.0 |

| Rodent | 9 | 6.5 | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 100.0 |

| Tarantula | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Participants reported information on up to three pets. The categories are not mutually exclusive.

Percentages are based on total number of participants that lived with the specific pet type.

Procedures

Participants were recruited between April 2019 and June 2020 within an urban city in an eastern region of the United States. We recruited participants via diverse efforts such as posting flyers in the community, posting study information online via social media and listservs, and distributing flyers at local community events. Interested participants contacted the project coordinators via phone or e-mail and completed a screening interview over the phone; those who met eligibility criteria scheduled a time to meet with study staff either in a private space at the university or at a community partner agency. Prior to beginning the interview, a research assistant described the purpose of the study to participants and completed the consent process. Participants then completed a self-administered survey on a laptop via RedCap; the research assistant was present, but not able to see the participant’s responses. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted using the video-conference platform, Zoom (version 5; March 17, 2020). This procedure applied to 10.1% of our sample. Participants received $50 in compensation either in cash for those completed in-person or by check for those via Zoom. All procedures were approved by the university IRB (HM20014415).

Measures

Comfort from Companion Animals Scale (CCAS):

The CCAS consists of 11 items and was developed to assess the level of emotional comfort companion animal owners receive from their companion animal (Zasloff, 1996). Participants provided responses on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to items such as “My pet is a source of consistency in my life” and “My pet makes me feel loved.” Internal consistency in the current study was excellent (α = 0.91).

Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale (PALS):

Pet attachment was assessed using the PALS (Cromer & Barlow, 2013), which consists of 35 items and four subscales: love (e.g., “My pet is part of my family,” “My pet gives me unconditional love”), regulation (e.g., “My pet teaches me to trust,” “My pet provides stability for me”), personal growth (e.g., “My pet teaches me responsibility,” “I have learned compassion from my pet”), and negative impact (e.g., “My pet is a financial hardship,” “Having a pet is stressful”). Participants rated how strongly each statement reflected the impact their companion animal had on their life on a 5-point Likert scale (from “not at all” to “very much”). Preliminary analysis found that a three-factor derivation of the PALS (i.e., love [α = 0.92], regulation [α = 0.86], personal growth [α = 0.83]) fit our data best and was utilized as a latent variable in our validity analysis.

Psychological Stress:

Psychological stress was measured using subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Savitz, 2000). Participants reported the intensity of distress they experienced in the past seven days for 53 items on a 5-point scale (“not at all” to “extremely”). Subscales included in this analysis were anxiety (α = 0.87), depression (α = 0.86), somatic complaints (α = 0.87), and interpersonal sensitivity (α = 0.80). These constructs were measured using observed scores, which were calculated by averaging the items on each subscale.

Analysis Strategy

We used MPlus (version 8.4) to test competing models of the CCAS factor structure, to evaluate measurement invariance across gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity, and to examine relations between CCAS, attachment to companion animals, and psychological stress. Due to the response format of the measures (i.e., Likert-type), items were treated as ordered categorical. A weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimator (WLSMV) was used to account for differences in the distances between ordinal categories (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006; Rhemtulla et al., 2012). Although the items were rated on a 4-point scale, preliminary analyses indicated that the response categories needed to be collapsed as few participants selected the lowest response options (i.e., on average 1.7% endorsed “strongly disagree” and 13.7% endorsed “disagree”). In order for the WLSMV estimator to run without error, the bivariate table across all variables cannot contain empty cells, which required us to collapse response options to a binary response scale (“strongly agree” and “do not strongly agree”). Due to empty cells resulting from low endorsement of categories other than “strongly agree,” which prevented measurement invariance testing, three items were deleted (see Table 1). The original 11-item version and the collapsed 8-item version were highly correlated (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) and had comparable internal consistencies (α = 0.91 and 0.89, respectively). Further, deletion of those items did not significantly affect model fit; therefore, the CCAS results reflect the eight remaining items in all models.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses and Measurement Invariance

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to compare the hypothesized unidimensional model of the CCAS with two competing models; our sample size was adequate to conduct this analysis (Wolf et al. 2013). We tested a 2-factor model (i.e., emotional bond, physical proximity) and a 3-factor model (i.e., comfort, nurturance, and satisfaction) based on similar item sets in related measures (Furman, 1989; Triebenbacher, 1999). Overall model fit for each was assessed using chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI). Non-significant chi-square tests, RMSEA values < 0.05, and CFI and TLI values > 0.95 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999); RMSEA values < 0.08 and CFI and TLI > 0.90 are indicative of adequate fit (Hooper et al., 2008). Chi-square difference tests were used to evaluate the fit of both competing models against the unidimensional model (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006), with significant p-values indicating that the model with more parameters and fewer degrees of freedom (i.e., alternative model) provided a better fit than the unidimensional model.

We conducted multiple group analyses to test for measurement invariance of the best-fitting model across sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity (i.e., whether the structure of the CCAS and item loadings are similar across demographic groups). Due to the requirement of non-empty cells, we dichotomized gender identity (cisgender, gender minority) and race/ethnicity (white/non-Latinx, racial/ethnic minority), and collapsed sexual orientation identities into three groups (gay/lesbian, bisexual/pansexual, other [queer, asexual, demisexual, multiple identities]) largely based on groups used by Arseneau et al. (2013) in a similar study with a SGM sample. Measurement invariance was examined by fitting an unconstrained model specifying the same factor structure across groups (i.e., configural invariance) and then comparing this model with a model that constrained factor loadings and thresholds to be equal across groups (i.e., scalar or strong invariance). We followed Cheung and Resvold’s (2002) recommendation and used change in CFI (ΔCFI) to evaluate measurement invariance due to the sensitivity of chi-square to sample size. The null hypothesis was not rejected if the ΔCFI was less than or equal to 0.01. Support for scalar invariance allows for comparison of means across subgroups.

Structural Equation Models

We tested the validity of the CCAS by examining associations between the CCAS and each of the three factors of the PALS via a structural equation model (SEM); we also employed an additional SEM to test relations between the CCAS and several domains of psychological stress (i.e., anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, interpersonal sensitivity), which were treated as observed variables in the model. We adjusted for age (continuous), gender identity (0 = cisgender; 1 = gender minority), sexual orientation (gay/lesbian, bisexual/pansexual, queer/asexual/demisexual/multiple identities), race/ethnicity (0 = racial/ethnic minority; 1 = White/non-Latinx), and participation before (= 0) or after (= 1) the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the SEM exploring relations between the CCAS and psychological stress. We included the COVID-19 covariate to adjust for how the pandemic may have influenced participants’ level of psychological stress and HAI.

Results

CCAS Structural Model

All of the models met the criteria recommended for adequate fit. Table 3 reflects fit statistics of the models. Differences in fit statistics between the unidimensional model and the alternative models were marginal; chi-square difference test results were not significant for the 2-factor or 3-factor model. Both alternative models resulted in identification errors (due to correlations > 1 between factors). Therefore, the original unidimensional model was retained for subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Fit indices of competing factor structure models of the Comfort from Companion Animals Scale.

| Model | χ 2 | df | χ 2 diffa | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unidimensional model | 23.56 | 20 | 0.036 | 0.998 | 0.997 | |

| 2-factor model | 23.47 | 19 | 1.34 | 0.041 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

| 3-factor model | 22.31 | 17 | 7.84 | 0.048 | 0.997 | 0.994 |

Note: n = 138. df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index.

Chi-square difference tests were not significant.

Measurement Invariance

We conducted multiple-group analyses to examine measurement invariance across gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity using the unidimensional model. Although the unidimensional model fit the data well based on the full sample, the structure may fit differently across subgroups. We tested the unidimensional model separately for gender minority groups; the model fit the data well for both the cisgender and the gender minority group (see Models G1 and G2 in Table 4). A model specifying the same factor structure across gender identity also fit the data well (Model G3 in Table 4), which supported configural invariance. The fit of a model that constrained factor loadings and item thresholds across gender identity changed minimally (i.e., ΔCFI = 0.001), which provided evidence for scalar invariance (i.e., the structure of the CCAS and the loadings were similar across groups; see Model G4 in Table 4).

Table 4.

Fit indices for measurement invariance tests of the unidimensional model of the CCAS.

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Multiple group by gender identity a | |||||

|

| |||||

| Cisgender only, n = 71 (G1) | 18.79 | 20 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.002 |

| Gender minority only, n = 67 (G2) | 26.67 | 20 | 0.071 | 0.993 | 0.990 |

| Configural invariance (G3) | 46.18 | 40 | 0.047 | 0.996 | 0.995 |

| Scalar invariance (G4) | 51.45 | 46 | 0.041 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

|

| |||||

| Multiple group by sexual orientation a | |||||

|

| |||||

| Gay and lesbian only, n = 34 (S1) | 19.56 | 20 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.002 |

| Bisexual and pansexual only, n = 56 (S2) |

24.20 | 20 | 0.061 | 0.996 | 0.994 |

| Other, n = 46 (S3)b | 17.91 | 20 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.005 |

| Configural invariance (S4) | 61.33 | 60 | 0.022 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| Scalar invariance (S5) | 70.11 | 72 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 |

|

| |||||

| Multiple group by race/ethnicity a | |||||

|

| |||||

| White only, n = 85 (R1) | 24.65 | 20 | 0.052 | 0.996 | 0.995 |

| Minority race/ethnicity only, n = 53 (R2) |

23.13 | 20 | 0.054 | 0.994 | 0.992 |

| Configural invariance (R3) | 47.54 | 40 | 0.052 | 0.996 | 0.994 |

| Scalar invariance (R4) | 51.39 | 46 | 0.041 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

Note: n = 138 for all models except for the multiple group model by sexual orientation. Two participants identified as heterosexual and were excluded as there was not sufficient sample size to examine as a separate group. df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index.

Model fit statistics are based on the unidimensional structure.

Queer, asexual, demisexual, multiple identities.

Similar analyses were conducted to examine the fit of the unidimensional model across the three sexual orientation groups. The unidimensional model fit well in separate analyses for all groups (see Models S1, S2, and S3 in Table 4). Multiple group analysis indicated that the model specifying the same factor structure across groups fit the data well, providing evidence for configural invariance (see Model S4 in Table 4). The model that constrained loadings and thresholds equal across subgroups did not change model fit (ΔCFI = 0.001; see Model S5 in Table 4), which supported scalar invariance. A final set of multiple group analyses examined invariance across racial/ethnic groups (i.e., white/non-Latinx vs. minority). Model fit across both groups was good (see Model R1 and R2 in Table 4). The configural model fit the data well (Model R3 in Table 4), and the scalar model did not change model fit (i.e., ΔCFI = 0.001; Model R4 in Table 4), which supported scalar invariance.

Structural Equation Models

We utilized structural equation modeling to assess the validity of the CCAS by examining relations of the latent variable with a related construct, attachment to companion animals. CCAS scores were positively and significantly correlated with the PALS scales which supported our hypothesis. Specifically, love (r = 0.90, p < 0.001), regulation, (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), and personal growth (r = 0.85, p < 0.001) were all strongly correlated with the CCAS. The PALS subscales also were strongly correlated with each other (rs > 0.80, p < 0.001). It should be noted that the PALS subscales used in this analysis excluded items found to be poor indicators of the construct via CFA (i.e., the love subscale excluded items 9, 18, and 19; the regulation subscale excluded items 23, 25, and 33).

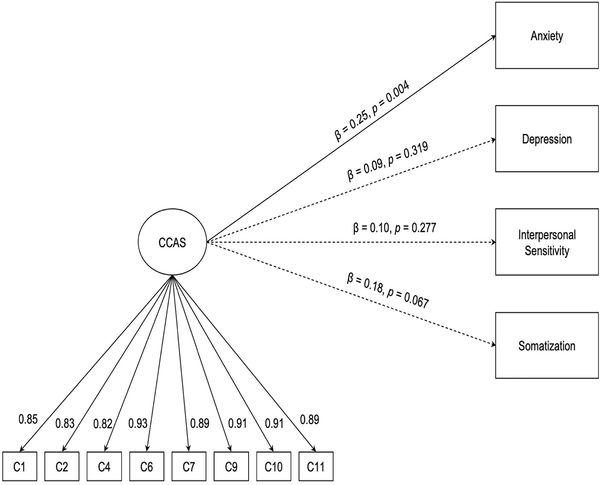

A final structural equation model was used to test the relations between the CCAS (i.e., the final CFA-supported latent variable model) and different domains of psychological stress: anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, and interpersonal sensitivity, adjusting for covariates. The resulting model fit the data well: 2(96) = 112.57, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98. Figure 1 displays the standardized coefficients for each domain of psychological stress. The CCAS was positively and significantly associated with anxiety (β = 0.21, p = 0.007). However, the CCAS was not uniquely associated with depression, somatic complaints, or interpersonal sensitivity. There was only one significant covariate effect. Those who identified as bisexual or pansexual reported lower levels of interpersonal sensitivity than individuals who reported other sexual orientations (d = –0.84, p = 0.046). We provide the mean and standard deviations for the CCAS, PALS, and BSI scale scores for each of the covariate groups tested in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model of associations between CCAS and domains of psychological stress. Note: n=136. Due to including the sexual orientation subgroups used in invariance testing as a covariate, two participants who identified as heterosexual were excluded. β indicates that the results of the SEM have been standardized in standard deviation units, such that a 1 standard deviation increase in CCAS corresponds to a change in the standard deviation of the outcome variables equivalent to the β-coefficient value (e.g., 0.25). To reduce complexity, covariates, residuals, and residual covariances are not reported in the figure. Dotted lines represent nonsignificant relations; solid lines represent significant associations.

Table 5.

Means and standard deviations of the CCAS, PALS, and BSI scales for each covariate group.

| Measure | White/non-Latinx | Racial/ethnic minority | t | df | p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| CCAS a | 85 | 13.66 | 2.78 | 51 | 13.29 | 2.74 | 0.56 | 106.58 | 0.46 | |||

| Lovea | 83 | 2.47 | 0.51 | 52 | 2.41 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 101.81 | 0.48 | |||

| Regulationa | 85 | 2.08 | 0.64 | 53 | 2.00 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 107.09 | 0.49 | |||

| Personal growth | 84 | 2.12 | 0.61 | 52 | 2.02 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 102.38 | 0.38 | |||

| Depression | 85 | 1.88 | 0.89 | 53 | 1.90 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 100.83 | 0.91 | |||

| Anxiety | 85 | 1.94 | 0.84 | 53 | 1.85 | 0.87 | 0.40 | 107.29 | 0.53 | |||

| Somatization | 85 | 1.45 | 0.88 | 53 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 2.76 | 116.91 | 0.10 | |||

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 85 | 1.97 | 0.98 | 53 | 2.02 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 114.40 | 0.77 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Gender identity | Cisgender | Gender minority | t | df | p | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| CCASa | 71 | 13.83 | 2.65 | 65 | 13.18 | 2.86 | 1.87 | 130.46 | 0.17 | |||

| Lovea | 70 | 2.51 | 0.46 | 65 | 2.38 | 0.58 | 2.15 | 122.55 | 0.15 | |||

| Regulationa | 71 | 2.05 | 0.62 | 67 | 2.05 | 0.68 | 0.001 | 132.88 | 0.97 | |||

| Personal growth | 69 | 2.17 | 0.58 | 67 | 1.99 | 0.65 | 2.96 | 131.36 | 0.09 | |||

| Depression | 71 | 1.79 | 0.97 | 67 | 2.00 | 0.88 | 1.77 | 135.74 | 0.19 | |||

| Anxiety | 71 | 1.80 | 0.97 | 67 | 2.02 | 0.69 | 2.34 | 126.40 | 0.13 | |||

| Somatization | 71 | 1.27 | 0.84 | 67 | 1.45 | 0.88 | 1.56 | 134.56 | 0.21 | |||

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 71 | 1.93 | 0.94 | 67 | 2.06 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 134.41 | 0.41 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 | Before | After | t | df | p | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| CCASa | 122 | 13.62 | 2.74 | 14 | 12.64 | 2.82 | 1.53 | 15.96 | 0.23 | |||

| Lovea | 121 | 2.48 | 0.52 | 14 | 2.20 | 0.50 | 3.83 | 16.43 | 0.07 | |||

| Regulationa | 124 | 2.10 | 0.63 | 14 | 1.64 | 0.69 | 5.64 | 15.59 | 0.03* | |||

| Personal growth | 122 | 2.10 | 0.62 | 14 | 1.99 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 15.77 | 0.56 | |||

| Depression | 124 | 1.89 | 0.95 | 14 | 1.94 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 17.55 | 0.81 | |||

| Anxiety | 124 | 1.91 | 0.86 | 14 | 1.86 | 0.82 | 0.06 | 16.33 | 0.81 | |||

| Somatization | 124 | 1.40 | 0.87 | 14 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 3.54 | 16.85 | 0.08 | |||

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 124 | 1.96 | 0.96 | 14 | 2.26 | 0.91 | 1.33 | 16.45 | 0.27 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Sexual orientation | Gay/lesbian | Bisexual/pansexual | Otherb | t | df | p | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| CCASa | 33 | 14.24 | 2.31 | 56 | 13.00 | 2.95 | 46 | 13.63 | 2.76 | 2.42 | 83.56 | 0.10 |

| Lovea | 34 | 2.53 | 0.46 | 55 | 2.37 | 0.52 | 44 | 2.46 | 0.57 | 1.22 | 81.39 | 0.30 |

| Regulationa | 34 | 2.02 | 0.64 | 56 | 2.02 | 0.67 | 46 | 2.09 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 81.28 | 0.84 |

| Personal growth | 33 | 2.18 | 0.58 | 56 | 2.00 | 0.67 | 45 | 2.10 | 0.60 | 0.97 | 81.17 | 0.38 |

| Depression | 34 | 1.94 | 0.99 | 56 | 1.75 | 0.89 | 46 | 1.98 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 78.71 | 0.41 |

| Anxiety | 34 | 1.99 | 0.96 | 56 | 1.73 | 0.86 | 46 | 2.04 | 0.74 | 1.98 | 78.07 | 0.15 |

| Somatization | 34 | 1.41 | 0.92 | 56 | 1.23 | 0.78 | 46 | 1.45 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 77.27 | 0.39 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 34 | 2.13 | 1.09 | 56 | 1.76 | 0.89 | 46 | 2.20 | 0.90 | 3.40 | 76.90 | 0.04* |

The CCAS excluded items 3, 5, and 8 and reflects the collapsed response options; the love subscale excluded items 9, 18 and 19; and the regulation subscale excluded items 23, 25, and 33.

Queer, asexual, demisexual, multiple identities.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to address gaps in HAI measurement by assessing the psychometric properties of the CCAS among a sample of SGM emerging adults. Our study found that a modified version of the CCAS fit our data best. Three items were deleted (see Table 1) and response categories were collapsed to address empty cells that resulted from participants not endorsing lower response options (i.e., strongly disagree, disagree), which suggests that the scale may not perform as originally intended among SGM emerging adults. Future studies employing the CCAS in research with this population should examine the fit of the scale to their data given these measurement issues.

The skewed distribution of responses is consistent with prior studies utilizing the CCAS (Luhmann & Kulitzski, 2018; Ratchsen et al., 2020), although a broader range of scores (i.e., 18–44) has been reported (Ramón et al., 2010). Zasloff’s (1996) testing of the CCAS found that participants’ average score was 39.95 (out of a total of 44), indicating that participants in their sample also did not endorse lower response options; however, Zasloff did not provide justification for retaining the 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” We are unaware of any studies examining the use of the CCAS response scale, which is an important direction for future research. Future studies should assess the use of the response scale in a variety of population groups and across developmental periods as individual samples may interpret the items and available response options differently. Additionally, response options may not adequately capture variation in those with extremely high or low levels of comfort from companion animals.

Using the modified version of the CCAS, our model demonstrated strong invariance across gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity groups. This provides evidence that the CCAS consistently measures emotional comfort from companion animals for individuals similar to those who participated in our study, when identities are dichotomized into the groupings used in our research; however, further testing should be conducted. Our findings also supported construct validity, although this should be considered in light of the modified scale and a double-barreled item on the CCAS that may have influenced validity. Item six, “My pet makes me play and laugh,” potentially resulted in participants responding in terms of “play” and/or “laugh.” Inclusion of this item can lead to inconsistent responses, which limits our ability to determine whether item six is a good indicator of the construct (DeVellis, 2017; Sullivan & Artino, 2017). Despite this potential issue, we found that the CCAS was significantly correlated with the PALS. This is consistent with prior research that found the CCAS to be correlated with other measures of human–pet attachment (e.g., Johnson et al., 1992; Schofield, 2003; Zilcha-Mano et al., 2011).

Although the CCAS is hypothesized to measure emotional comfort as a unique aspect of attachment to companion animals, the strong, positive correlations suggest that the CCAS and the three factors of the PALS may be measuring the same construct. For example, when determining alternative factor models to test in the current study, an examination of the items comprising the CCAS and the PALS identified several items that overlap (i.e., my pet is a companion, makes me feel needed, gives me something to love, teaches me trust, calms me down, cheers me up, provides stability/constancy, and is fun/entertaining). The results of our study highlight the need for researchers to further explore whether emotional comfort derived from pets is distinct from other human–animal bond-related constructs, such as pet attachment. Our findings reinforce prior arguments that a lack of consistency in definition and measurement of human–animal attachment, and more broadly HAI, makes accurately interpreting results and comparing findings across studies difficult (Crawford et al., 2006; Esposito et al. 2011; Purewal et al., 2017).

The results of the final structural equation model testing the relation between the CCAS and psychological stress domains found that the CCAS was not significantly associated with depression or interpersonal sensitivity but was significantly and positively associated with anxiety, adjusting for covariates. Although this did not support our hypothesis regarding the relation between the CCAS and psychological stress, the positive associations are consistent with prior studies of emerging adult samples (Matijczak et al., 2021; McDonald, O’Connor et al., 2021): for example, a study of undergraduate students found that living with a pet significantly predicted internalizing symptoms (Barker et al., 2020). The results of these studies, as well as the current study, utilize cross-sectional data and thus do not allow causal inferences. Therefore, the positive associations found between pet ownership, CCAS scores, and mental health outcomes may result from those who experience greater mental health symptoms relying on their pet more for emotional comfort.

Given the current public health crisis, it is important to note that participation before or after the implementation of our COVID-19 procedures was not a significant covariate in the relation between the CCAS and psychological stress in the SEM. There was only one significant covariate effect in the SEM. Although the overall relation between the CCAS and interpersonal sensitivity was not significant, participants who identified as bisexual or pansexual reported lower levels of interpersonal sensitivity than those who identified as other sexual orientations. This is in contrast to prior research that found bisexual and/or pansexual individuals reported higher rates of mental health issues, including interpersonal sensitivity, than those who identified as heterosexual or other sexual orientations (D’Augelli, 2002; Flanders et al., 2017; Volpp, 2010). In the context of HAI, our results highlight the importance of continuing to explore the potential protective benefits received from companion animals, accounting for differences across expansive SGM identities.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of our study should be interpreted in light of several methodological limitations. Although the hypothesized unidimensional structure fit the data well, participants did not use the response scale as intended, which required the three lowest categories to be combined and the deletion of three items. Psychometric testing of the CCAS would benefit from revising the response options and/or revising the measure to include items and/or response categories that better differentiate those who experience low and high levels of comfort from companion animals. Further, our study’s sample size required us to dichotomize gender identity and race/ethnicity and create a collapsed three-group variable for sexual orientation to test measurement invariance in the CFA. This limited our ability to test invariance across all SGM and racial/ethnic minority groups. Further, multiple group modeling was not possible for the larger SEM because a larger sample is needed for more complex models with more parameters (i.e., at least 100 participants per group; Kline, 2005). Our sample was also predominantly dog and/or cat owners (97%), which prevented us from testing invariance based on pet type due to power concerns. Therefore, the ability of the CCAS to accurately and validly assess emotional comfort across expansive SGM identities, race/ethnicities, and pet types should be explored in future research. Until further investigations can definitively make recommendations to use the revised (binary) response scale, we recommend that researchers continue to use the full scale with caution. Researchers should be aware of the potential need to collapse response categories due to infrequent endorsement of lower response options and the potential for measurement non-invariance when comparing groups. This study emphasizes the importance of testing for measurement invariance and making adjustments to the scale when necessary.

Although emotional comfort derived from companion animals is an important construct owing to the associated benefits for mental health, future studies should seek to delineate which aspects of HAI (e.g., emotional comfort, attachment, caretaking behaviors) may be most important in buffering and/or exacerbating the effects of distinct forms of stress or adversity in relation to specific mental health outcomes. In addition, we did not find that the timing of the interview (pre- or during COVID-19) was related to the independent or dependent variable in the final SEM; however, this result should be interpreted with caution because of the unequal sample sizes in each group (n = 14 versus n = 124) – this may have influenced our power to detect differences between groups and/or biased our estimates. This contrasts with recent findings that both HAI and psychological stress have been influenced by pandemic-related stress (e.g., Applebaum et al., 2020; Holman et al., 2020; McGinty et al., 2020; Shoesmith et al., 2021).

Another limitation involves our use of cross-sectional data and our inability to determine whether SGM emerging adults who reported greater emotional comfort from companion animals may have had greater psychological stress and thus relied more on their pet for comfort, or whether owning and caring for a companion animal may have resulted in additional psychological stress. Given their increased risk for mental health symptoms as a result of stress associated with the emerging adult period and/or SGM-related stress, future longitudinal studies should seek to disentangle relations between emotional comfort derived from companion animals and psychological stress over time, as well as examine the temporal stability of the CCAS.

HAI researchers testing the CCAS, and other HAI instruments, would do well to include diverse samples across a wide range of developmental stages. Specifically, owing to the associated benefits emotional comfort provides for mental health, researchers should continue to test the CCAS among SGM samples. The current lack of a valid and reliable measure of emotional comfort is a limitation to HAI researchers who seek to draw conclusions regarding mean scores across demographic groups to inform practice, intervention, and policy recommendations regarding companion animals.

Conclusion

This is the first study to psychometrically test the CCAS among a sample of SGM emerging adults and to examine alternative factor structures and measurement invariance across demographic groups. We found that a modified unidimensional structure of the CCAS fit our data best; the lack of responses endorsing lower levels of comfort from companion animals required the response scale to be collapsed. Although we found invariance across demographic groups, due to the modifications required, further testing of the CCAS is needed. Our results emphasize the importance of rigorously testing measures that assess domains of HAI (e.g., attachment or emotional comfort) within and across diverse populations, especially minoritized and vulnerable populations. This is critical to advance methodological rigor in HAI science to be able to meaningfully utilize tested measures within studies that seek to identify under what conditions and for whom HAI confers the greatest public health risks and benefits.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the youth and young adults who participated in this research by graciously sharing their stories. We also thank the staff at Side by Side, Virginia League for Planned Parenthood, Nationz Foundation, and Health Brigade for their contribution to this work and continued investment in our project. We thank Dr. Alex Wagaman and Dr. Traci Wike for their contributions to the research design and supervision of research assistants during the planning process. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

Data collection for the LGBTQ+ Youth Supports study was funded by the VCU Presidential Research Quest Fund (PI: McDonald). The research reported in this publication is supported by a National Institute of Health, Health Disparities Loan Repayment Program Award through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1L60HD103238-01, PI: McDonald).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Applebaum JW, Tomlinson CA, Matijczak A, McDonald SE, & Zsembik BA (2020). The concerns, difficulties, and stressors of caring for pets during COVID-19: Results from a large survey of U.S. pet owners. Animals, 10(10), Article 1882. 10.3390/ani10101882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, & Sugimura K (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneau JR, Grzanka PR, Miles JR, & Fassinger RE (2013). Development and initial validation of the Sexual Orientation Beliefs Scale (SOBS). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 407–420. 10.1037/a0032799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2006, May 26). Robust chi square difference testing with mean and variance adjusted test statistics. Mplus. https://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/webnote10.pdf

- Barker SB, Schubert CM, Barker RT, Kuo SI, Kendler KS, & Dick DM (2020). The relationship between pet ownership, social support, and internalizing symptoms in students from the 1st to 4th year of college. Applied Developmental Science, 24, 279–293. 10.1080/10888691.2018.1476148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel A, & Herzberg PY (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling, 13(2), 186–203. 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blazina C, & Bartone AS (2016). The roles animal companions play in middle-aged males’ lives: Examining the psychometric properties of a measure assessing males’ human–animal interactions. In Blazina C & Kogan L (Eds.), Men and their dogs (pp. 215–229). Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-30097-9_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1983). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books. (Original work published 1969) [Google Scholar]

- Bures RM, Mueller MK, & Gee NR (2019). Measuring human–animal attachment in a large U.S. survey: Two brief measures for children and their primary caregivers. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 107. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Resvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Community Marketing & Insights. (2019, July). 13th Annual LGBTQ community survey: USA summary report. https://www.communitymarketinginc.com/documents/temp/CMI-13th_LGBTQ_Community_Survey_US_Profile.pdf

- Cooper SR, Gonthier C, Barch DM, & Braver TS (2017). The role of psychometrics in individual differences research in cognition: A case study of the AX-CPT. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford EK, Worsham NL, & Swinehart ER (2006). Benefits derived from companion animals, and the use of the term “attachment”. Anthrozoös, 19(2), 98–112. 10.2752/089279306785593757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cromer LD, & Barlow MR (2013). Factors and convergent validity of the Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale (PALS). Human–Animal Interaction Bulletin, 1(2), 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 433–456. 10.1177/1359104502007003010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JH (1987). Preadolescent self-concept development and pet ownership. Anthrozoös, 1(2), 90–99. 10.2752/089279388787058614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delacre M, Lakens D, & Leys C (2017). Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 92–101. 10.5334/irsp.82 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Savitz KL (2000). The SCL–90–R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in primary care. In Maruish ME (Ed.), Handbook of psychological assessment in primary care settings (pp. 297–334). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Doan Van EE, Mereish EH, Woulfe JM, & Katz-Wise SL (2019). Perceived discrimination, coping mechanisms, and effects on health in bisexual and other non-monosexual adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 159–174. 10.1007/s10508-018-1254-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer F, Bennett PC, & Coleman GJ (2006). Development of the Monash Dog Owner-Relationship Scale (MDORS). Anthrozoös, 19(3), 243–256. 10.2752/089279306785415592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlke SJ, Braitman AL, Dawson CA, Heron KE, & Lewis RJ (2020). Sexual minority stress and social support explain the association between sexual identity with physical and mental health problems among young lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles, 83, 370–381. 10.1007/s11199-019-01117-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Gower AL, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, Shea G, & Coleman E (2017). Risk and protective factors in the lives of transgender/gender non-conforming adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61, 521–526. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito L, McCune S, Griffin JA, & Maholmes V (2011). Directions in human–animal interaction research: Child development, health, and therapeutic interventions. Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 205–211. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00175.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner A, & Garber J (2002). 2001 gay/lesbian consumer online census. Syracuse University, OpusComm Group, and GSociety. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Dobinson C, & Logie C (2017). Young bisexual women’s perspectives on the relationship between bisexual stigma, mental health, and sexual health: A qualitative study. Critical Public Health, 27(1), 75–85. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1158786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, & Brown TNT (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Adults-US-Aug-2016.pdf

- Frost DM, Meyer IH, & Hammock PL (2014). Health and well-being in emerging adults’ same-sex relationships: Critical questions and directions for research in developmental science. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 3–13. 10.1177/2167696814535915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W (1989). The development of children’s social networks. In Belle D (Ed.), Children’s social networks and social supports (pp. 151–172). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF Jr., Black WC, Babin BJ, & Anderson RE (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education international. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Interactive. (2010). The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) population at-a-glance. https://www.witeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/HI_LGBT_SHEET_WCC_AtAGlance.pdf

- Holman EA, Thompson RR, Garfin DR, & Silver RC (2020). The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic: A probability-based, nationally representative study of mental health in the United States. Science Advances, 6(2), Article eabd5390. 10.1126/sciadv.abd5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, & Mullen MR (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Poteat VP, Horn SS, & Kosciw J (2019). Strengthening our schools to promote resilience and health among LGBTQ youth: Emerging evidence and research priorities from The State of LGBTQ Youth Health and Wellbeing symposium. LGBT Health, 6(4), 146–155. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Garrity TF, & Stallones L (1992). Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös, 5(3), 160–175. 10.2752/089279392787011395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Methodology in the social sciences: Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- le Roux MC, & Wright S (2020). The relationship between pet attachment, life satisfaction, and perceived stress: Results from a South African online survey. Anthrozoös, 33(3), 371–385. 10.1080/08927936.2020.1746525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loven AM (2005). The effect of pet ownership/attachment on the stress level of multiple sclerosis patients [Master’s thesis, Texas A & M University]. OAKTrust. https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/2527 [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M, & Kalitzki A (2018). How animals contribute to subjective well-being: A comprehensive model of protective and risk factors. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(2), 200–214. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1257054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matijczak A, McDonald SE, Tomlinson CA, Murphy JL, & O’Connor K (2021). The moderating effect of comfort from companion animals and social support on the relationship between microaggressions and mental health in LGBTQ+ emerging adults. Behavioral Sciences, 11, Article 1. 10.3390/bs11010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune S, Kruger KA, Griffin JA, Esposito L, Freund LS, Hurley KJ, & Bures R (2014). Evolution of research into the mutual benefits of human–animal interaction. Animal Frontiers, 4(3), 49–58. 10.2527/af.2014-0022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald K (2018). Social support and mental health in LGBTQ adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(1), 16–29. 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SE, Matijczak A, Nicotera N, Applebaum JW, Kremer L, Natoli G, O’Ryan R, Booth LJ, Murphy JL, Tomlinson CA, & Kattari SK (2021). “He was like, my ride or die”: Sexual and gender minority emerging adults’ perspectives on living with pets during the transition to adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. Advance online publication. 10.1177/2167696821102534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SE, Murphy JL, Tomlinson CA, Matijczak A, Applebaum JW, Wike TL, & Kattari SK (2021). Relations between sexual and gender minority stress, personal hardiness, and psychological stress in emerging adulthood: Examining indirect effects via human–animal interaction. Youth & Society, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.11770044118X21990044 [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SE, O’Connor K, Matijczak A, Murphy JL, Applebaum JW, Tomlinson CA, Wike T, & Kattari S (2021). Victimization and psychological wellbeing among sexual and gender minority emerging adults: Testing the moderating role of emotional comfort from companion animals. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0044118X21990044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, & Barry CL (2020). Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA, 324(1), 93–94. 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse AML, Wax A, Malmquist EJ, & Hopmeyer A (2019). Protester, partygoer, or simply playing it down? The impact of crowd affiliations on LGBT emerging adult socioemotional and academic adjustment to college. Journal of Homosexuality. Advance online publication. 10.1080/00918369.2019.1657752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MK (2014). Human–animal interaction as a context for positive youth development: A relational developmental systems approach to constructing human–animal interaction theory and research. Human Development, 57, 5–25. 10.1159/000356914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, & Mustanski B (2012). Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A longitudinal multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73, 783–793. 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachana NA, Massavelli BM, & Robleda-Gomez S (2011). A developmental psychological perspective on the human–animal bond. In Blazina C, Boyraz G, & Shen-Miller D (Eds.), The psychology of the human–animal bond (pp. 151–165). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-9761-6_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piper LJ, & Uttley CM (2019). Adolescents and pets. In Kogan L & Blazina C (Eds.), Clinician’s guide to treating companion animals: Addressing human animal interaction (pp. 47–75). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-812962-3.00004-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purewal R, Christley R, Kordas K, Joinson C, Meints K, Gee N, & Westgarth C (2017). Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 234. 10.3390/ijerph14030234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JM (2014). Older lesbian adults’ psychological well-being: The significance of pets. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 26(1), 1–17. 10.1080/10538720.2013.866064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón ME, Slater MR, & Ward MP (2010). Companion animal knowledge, attachment and pet cat care and their associations with household demographics for residents of a rural Texas town. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 94(3–4), 251–263. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratschen E, Shoesmith E, Shahab L, Silva K, Kale D, Toner P, Reeve C, & Mills DS (2020). Human–animal relationships and interaction during the Covid-19 lockdown phase in the UK: Investigating links with mental health and loneliness. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0239397. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PE, & Savalei V (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17, 354–373. 10.1037/a0029315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, & Rice E (2015). Pet ownership among homeless youth: Associations with mental health, service utilization and housing status. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 46(2), 237–244. 10.1007/s10578-014-0463-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DW, Taylor N, Signal T, Fraser H, & Donovan C (2018). People of diverse genders and/or sexualities and their animal companions: Experiences of family violence in a binational sample. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 4226–4247. 10.1177/0192513X18811164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risley-Curtiss C, Holley LC, Wolf S (2006). The animal–human bond and ethnic diversity. Social Work, 51(3), 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez KE, Guérin NA, Gabriels RL, Serpell JA, Schreiner PJ, & O’Haire ME (2018). The state of assessment in human–animal interaction research. Human–Animal Interaction Bulletin, 6, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Riggs DW, Taylor N, & Fraser H (2020). ‘Being together really helped’: Australian transgender and non-binary people and their animal companions living through violence and marginalisation. Journal of Sociology, 56(4), 571–590. 10.1177/1440783319896413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Parast L, Babey SH, & Miles JV (2017). Exploring the differences between pet and non-pet owners: Implications for human–animal interaction research and policy. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0179494. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz RM, Carlisle ZT, & Tabler J (2021). “Companion, friend, four-legged fluff ball”: The power of pets in the lives of LGBTQ+ young people experiencing homelessness. Sexualities. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1363460720986908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield VL (2003). A comparison of the perceived well-being of pet owners and non-pet owners. FSU Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schrager SM, Steiner RJ, Bouris AM, Macapagal K, & Brown CH (2019). Methodological considerations for advancing research on the health and wellbeing of sexual and gender minority youth. LGBT Health, 6(4), 156–165. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoesmith E, Shahab L, Kale D, Mills DS, Reeve C, Toner P, Santos de Assis L, & Ratschen E (2021). The influence of human–animal interactions on mental and physical health during the first COVID-19 lockdown phase in the U.K.: A qualitative exploration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), Article 976. 10.3390/ijerph18030976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsma K (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107–120. 10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GM, & Artino AR Jr. (2017). How to create a bad survey instrument. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(4), 411–415. 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00375.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Jia M, Wu H, Yang Q, Wang Q, Wang L, & Xu H (2021). The effect of comfort care based on the collaborative care model on the compliance and self-care ability of patients with coronary heart disease. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(1), 501–508. 10.21037/apm-20-2520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif-Williams CY, & Bosacki SL (2015). Evaluating the impact of a humane education summer camp program on school-aged children’s relationship with companion animals. Anthrozoös, 28(4), 587–600. 10.1080/08927936.2015.1070001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Williams Institute. (2019, January). LGBT demographic data interactive. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT#about-the-data

- Triebenbacher SL (1999). Re-evaluation of the Companion Animal Bonding Scale. Anthrozoös, 12(3), 169–173. 10.2752/089279399787000200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trizano-Hermosilla I, & Alvarado JM (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 769. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro A, & Mena JA (2011). It’s not burnout, it’s more: Queer college activists of color and mental health. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 15(4), 339–367. 10.1080/19359705.2011.600656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp SY (2010). What about the “B” in LGB: Are bisexual women’s mental health issues same or different? Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14(1), 41–51. 10.1080/19359700903416016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagaman MA, Keller MF, & Cavaliere SJ (2014). What does it mean to be a successful adult? Exploring perceptions of the transition into adulthood among LGBTQ emerging adults in a community-based service context. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 28(2), 140–158. 10.1080/10538720.2016.1155519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, & Irurita VF (2005). Enhancing the therapeutic potential of hospital environments by increasing the personal control and emotional comfort of hospitalized patients. Applied Nursing Research, 18(1), 22–28. 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, & Irurita VF (2006). Emotional comfort: The patient’s perspective of a therapeutic context. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(4), 405–415. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, Lester L, Bulsara C, Petterson A, Bennett K, Allen E, & Joske D (2017). Patient Evaluation of Emotional Comfort Experienced (PEECE): Developing and testing a measurement instrument. BMJ Open, 7(1), e012999. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CC, & Netting FE (2012). The status of instrument development in the human–animal interaction field. Anthrozoös, 25(Suppl. 1), S11–S55. 10.2752/175303712X13353430376977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, & Miller MW (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution property. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. 10.1177/0013164413495237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff RL (1996). Measuring attachment to companion animals: A dog is not a cat is not a bird. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 47(1–2), 43–48. 10.1016/0168-1591(95)01009-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S, Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2011). An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(4), 345–357. 10.1016/j.jrp.2011.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]