Abstract

Background

Vaginal neoplasms are rare. To study the survival of patients depending on tumour characteristics and age, the data from the national cancer registries in Germany were analysed.

Methods

In a retrospective analysis, data from 2006 to 2015 on disease stage, survival, and factors that might affect prognosis were analysed.

Results

Altogether, out of 4004 datasets, 2194 were deemed adequate to be included in the analysis. Overall survival at 5 years (5YSR) and relative survival (5RSR) were 48.6% (95%CI 45.4–52.1%) and 58.7% (95%CI 55.3–61.2%) for carcinomas, but significantly worse at 20.2% (95%CI 8.3–32.0%) and 24.2% (95%CI 16.4–32.0%) for melanomas and 38.3% (95%CI 23.3–53.5%) and 44.4% (95%CI 31.5–56.8%) for sarcomas. 5YSR and 5RSR correlated significantly with FIGO stages (5YSR: 66.9–10.1%; 5RSR: 81.7–11.9%, p = 0.04). Furthermore, survival depended on the absence of LN metastases (5RSR: 59.1% vs. 38.0%, p < 0.001), and the tumour grading had an influence (5RSR: 83.7–52.1%). We also noted that prognosis was worse for older patients ≥75 years (5RSR:51.2%) than for patients <55 years (62.2%) and 55–74 years of age (61.6%).

Conclusion

Unless LN metastases, local advanced tumours and G3 grading are associated with a worse prognosis. Relative survival of older patients decreases, perhaps indicating that treatment compromises have been made

Keywords: Vaginal cancer, Epidemiology, Survival, Age

Introduction

Primary vaginal cancer is one of the rarest cancers. Worldwide, 17,600 new cases and 8000 deaths were documented in 2018, which is less than 0.1% of all cancers worldwide (Bray et al. 2018). In Germany, the average number of annual new cases between 1999 and 2017 was 467, which corresponds to 1.6% of genital cancers and is less than that for male breast cancer (628/year) (Centre for Cancer Registry Data at the Robert Koch Institute 2020). This proportion is similar to that of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the USA (1.3% of genital cancers) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2018). Most of the time, vaginal cancer affects older patients, with more than half of those diagnosed being over 70 years old (Centre for Cancer Registry Data at the Robert Koch Institute 2020). Due to its morphological similarity to cervical and vulvar cancer, neoplasms that affect one of the two neighbouring organs in addition to the vagina are counted as cervical or vulvar cancer, making isolated vaginal cancer even rarer. Most cases of vaginal neoplasms are squamous cell carcinomas, followed by the much smaller group of adenocarcinomas and the scarce melanomas or sarcomas (Adams and Cuello 2018). HPV infection is probably the main risk factor, but chronic vaginitis and foreign objects such as vaginal pessaries are also implicated at times (Daling et al. 2002; Merino 1991). As with other HPV-related carcinomas, early sexual contact, smoking, and low socioeconomic status are also are suspected risk factors. However, previous HPV-associated carcinomas or precancerous lesions of the cervix or anus and the presence of genital warts are of particular importance (Adams and Cuello 2018; Daling et al. 2002; Ebisch et al. 2017). A particularly increased risk of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia has been described for patients who underwent a hysterectomy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (Jentschke et al. 2016; Cao et al. 2021). Overall, HPV can be detected in ¾ of the cases of invasive vaginal cancer (Alemany et al. 2014).

Vaginal cancer is classified according to clinical manifestations. Both the TNM classification of the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) (Committee and on Cancer 2017) and the classification of the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2018) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of staging systems for vaginal cancer according to TNM and FIGO

| Stage grouping (TNM) | FIGO stage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

T1a N0 M0 T1b N0 M0 |

I |

Cancer only in the vagina and ≤ 2.0 cm Cancer only in the vagina and > 2.0 cm |

||||

|

T2a N0 M0 T2b N0 M0 |

II |

Cancer grown through the vaginal wall ≤ 2.0 cm Cancer grown through the vaginal wall> 2.0 cm |

||||

|

T3 N0 M0 T1-3 N1 M0 |

III |

Cancer any size and might be growing into the pelvic wall, and/or growing blocked the flow of urine N1 lymph nodes in the pelvis or groin (inguinal) area (N1) |

||||

| T4 N0/1 M0 | Iva | Cancer into the bladder or rectum or out of the pelvis (T4) | ||||

| T1-4 N0/1 M1 | IVb | Cancer spread distant organs | ||||

Due to the rarity of the disease, there are almost no randomised studies, and only a few retrospective studies exist that have a sufficiently large patient cohort to allow conclusions to be drawn about the prognosis and influencing factors. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess prognosis based on various factors using 10 years of nationwide population-based cancer registry data in Germany. Thus, studies suggest that the most important prognostic factor is the involvement of the lymph nodes. Beyond that, we wanted to find out whether other criteria of tumour characteristics and age have a direct influence on the survival of patients.

Materials and methods

For this study, all datasets of the German Centre for Cancer Registry Data, compiled from the epidemiological state cancer registries1 of patients who had a first diagnosis of vaginal cancer in Germany from 01/01/2006 to 31/12/2015, were collected; data on survival in the cancer registries were available up to and including 2017. The use of the data for this study was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Board of the German Centre for Cancer Registry Data, Robert Koch Institute. Patients who did not have epithelial carcinoma, but sarcoma or melanoma was analysed separately. In addition, patients were excluded from the evaluation if diagnosis was reported at the time of death by death certificate only (DCO). The disease was only considered vaginal cancer if there was no concomitant involvement of the cervix, vulva or carcinoma in these areas in the past. The Centre for Cancer Registries annually compiles the data from the regional cancer registries and estimates their completeness. In the process, an existing under-recording in the regions is corrected. Based on this, during the years 2006–2015, 4004 of 4843 (83%) patients with vaginal carcinoma could be recorded in the cancer registries, whereby the coverage in the different years ranged from 70% in 2006 to 90% in 2013. Of these, 8.7% of new cases were only documented via death certificates (DCO cases).

Patients were also excluded if the available information did not allow analysis of the disease according to the FIGO classification. The date of diagnosis and end date of observation, death, and tumour data according to TNM and FIGO classification were recorded. In addition to pathological findings, clinical and imaging findings were also used for classification. Lymph-node (LN) metastases were classified as N1 according to the UICC and FIGO classification if they were located iliac or inguinofemoral; metastases in the paraaortic LN corresponded to distant metastases (M1). The tumours were categorised into squamous cell, adeno- or other carcinomas, sarcoma or melanoma according to the ICD-O code. Processing and data analysis were performed with the statistical programme BIOS for WindowsTM (version 11.1 Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany) using the Mann–Whitney test for data without normal distribution as well as the Fisher–Yates exact test and the Haldane–Dawson test. Survival time analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier estimator and the log-rank test according to Peto and Pike. The confidence level was p = 0.05. Due to the median age of the patients being 70 years and the need to consider tumour-related and independent deaths, relative survival to a comparable general population was calculated. Relative survival was calculated by comparing the survival time from diagnosis to death of the patients with the survival in the German women in the corresponding age group. The expected survival in the population was determined from mortality tables according to the Ederer II method (Ederer et al. 1961), and SurvSoft software (version 2.0, Erlangen, Germany) was used for the calculations (Geiss and Meyer 2013). In the analysis of the results, survival was considered significantly reduced if the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval was less than the lower limit of the compared group.

Results

Of a total of 4004 datasets obtained from the cancer registries, 2194 patients were included in the analysis. Of these, 1880 patients had epithelioid vaginal cancer, 174 patients had vaginal melanoma, and 94 patients had vaginal sarcoma, which were analysed separately. The median age of patients with carcinoma was 69 years (range: 18–93 years); for patients with melanoma, it was 70 years (34–90 years); and for patients with sarcoma, it was 70 years (31–88 years).

Due to missing (n = 1549) or incomplete data (n = 253) of the tumour, it was not possible to classify the other patients according to the Figo system. An in situ stage was found in 8 patients or the UICC classification was T0 N0 M0. Among the patients, the median age was 73 years. The carcinoma patients were classified according to the TNM and FIGO classification. The classification was not applied to sarcomas and melanomas, as the definitions are not transferable to them. FIGO I stage was most common with 744 patients (38.8%), whereas FIGO II (n = 340, 17.7%) and FIGO III (n = 386, 20.1%) were found less frequently. An FIGO IV stage was present in 445 patients (23.3%). In 486 patients (25.3%) with vaginal carcinoma, metastases were found in the regional lymph nodes in the groin or pelvis. Overall, squamous cell carcinoma was the most common histological feature in 1615 (86.2%) followed by adenocarcinoma in 8.3% of patients (n = 160). The grading was divided into G1 (5.4%), G2 (49.5%), and G3 (36.4%). The distribution of grading did not differ for the histological subtypes (see Table 2 for patient characteristics). The data on the different treatment options were apparently so incomplete that a reasonable analysis did not seem sensible and was therefore not carried out.

Table 2.

Clinical findings of carcinoma cases according to the FIGO classification, sarcomas, and melanomas show no significant differences between the groups

| All carcinoma | FIGO I | FIGO II | FIGO III | FIGO IV | Melanoma | Sarcoma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1915 | 744 (38.8%) | 340 (17.7%) | 386 (20.1%) | 445 (23.3%) | 174 | 94 |

| Median age (years, range) | 69 (18–93) | 69 (27–92) | 70 (26–91) | 69 (23–92) | 69 (18–93) | 70 (34–90) | 70 (31–88) |

| Tumour stage | |||||||

| T1 | 835 (43.6%) | 744 | 0 | 74 (19.2%) | 17 (3.8%) | ||

| T2 | 512 (26.7%) | 0 | 340 | 144 (37.4%) | 28 (6.3%) | ||

| T3 | 172 (8.9%) | 0 | 0 | 151 (39.2%) | 21 (4.7%) | ||

| T4 | 315 (16.4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 315 (69.6%) | ||

| Lymph-node status | |||||||

| N1 | 486 (25.3%) | 0 | 0 | 291 (75.6%) | 185 (41.9%) | ||

| Grading | |||||||

| G1 | 105 (5.4%) | 73 (9.8%) | 14 (4.2%) | 8 (2.0%) | 10 (1.9%) | ||

| G2 | 947 (49.5%) | 408 (54.9%) | 158 (46.5%) | 195 (50.3%) | 186 (45.8%) | ||

| G3 | 697 (36.4%) | 212 (28.9%) | 147 (43.2%) | 150 (39.0%) | 188 (42.6%) | ||

| Histologya | |||||||

| SCC | 1651 (86.2%) | 680 (94.0%) | 293 (88.5%) | 327 (84.9%) | 351 (79.6%) | ||

| ADC | 160 (8.3%) | 41 (5.7%) | 33 (10.0%) | 36 (9.3%) | 50 (11.3%) |

SCC squamous cell carcinoma, ADC adenocarcinoma

aThe TNM and FIGO classifications were not applied to sarcomas and melanomas

Survival analysis

For all patients with vaginal cancer, the median overall survival (OS) was 58 months (95% confidence interval (CI):51.1–64.8), and the 5-year survival rate (5YSR) was 48.6% (CI:45.4–52.1%). Compared to this, overall survival for patients with vaginal melanoma or sarcoma was significantly worse at only 19 months (5YSR: 20.2%; CI:8.3–32.0%; p < 0.001) and 26 months (5YSR: 38.3%; CI:23.3–53.5%; p < 0.001), respectively. The analysis of overall survival according to the FIGO stages showed that the 5YSR in FIGO stage I was 66.9% (CI:61.9–72.5%, Hazard ratio (HR) 1), whereas it was significantly reduced in stages II (50.5%; CI:41.9–57.9%, HR 1.79), III (44.0%; CI:36.7–51.6% HR 2.09), IVa (30.5% CI:21.0–40.1% HR 3.21), and IVb (10.2% CI:0–20.7%, HR 6.18 p = 0.04). The median survival is therefore between 123 and 9 months (see Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Survival was found to be significantly worse with increase in FIGO stage (p = 0.04) and for melanoma and sarcoma (p < 0.001)

| All carcinoma | FIGO I | FIGO II | FIGO III | FIGO IV | Melanoma | Sarcoma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVa | IVb | |||||||

|

Overall survival (95% confidence interval) |

||||||||

|

Median (month) |

58 (51.1–64.8) |

123 (112.4–133) |

60 (43.2–76.8) |

48 (36.2–59.8) |

20 (16–23-7) |

9 (7.1–10.6) |

19 (16.8–21.2) |

26 (3.1–48.9) |

| 5-year survival rate |

48.6% (45.4–52.1%) |

66.9% (61.9–72.5%) |

50.5% (41.9–57.9%) |

44% (36.7–51.6%) |

30.5% (21.0–40.1% |

10.2% (0–20.7%) |

20.2% (8.3–32.0%) |

38.3% (23.3–53.5%) |

|

Relative survival rate (95% confidence interval) |

||||||||

| 1 year |

83.0% (81.2–84.9%) |

97.9% (96.2–99.6%) |

87.2% (82.9–91.0%) |

80.1% (75.3–84.1%) |

74.2% (67.1–79.1%) |

41.2% (32.5–46.2%) |

74.7% (67.7–81.7%) |

65.2% (55.0–75.4%) |

| 3 year |

64.9% (62.4–67.4%) |

87.7% (84.1–90.9%) |

67.4% (61.1–72.8%) |

59.2% (53.3–64.6%) |

41.5% (34.3–48.2%) |

18.3% (12.8–24.0%) |

30.2% (23.2–38.8%) |

50.1% (38.7–61.4%) |

| 5 year |

58.2% (55.3–61.2%) |

81.7% (77.3–86.3%) |

59.1% (52.0–65.5%) |

52.0% (45.4–58.0%) |

36.0% (29.0–43.6%) |

11.9% (6.1–16.6%) |

24.2% (16.4–32.0%) |

44.4% (31.5–56.8%) |

Fig. 1.

Results of the Kaplan–Meier analysis show that overall survival is significantly different between FIGO stages (log-rank test p = 0.04)

Due to the late age of onset of the disease, it is also necessary to calculate relative survival compared to a population at large. The 5-year relative survival rate (5RSR) ranges from 81.7% in stage I to 12% in stage IVb (see Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The annual relative survival rates and 95% confidence intervals for the patient groups according to FIGO stages I–IVa/b

The patients in FIGO III showed considerable differences; this group included locally advanced tumours up to the pelvic wall without LN metastases (T3N0: n = 59) as well as patients with LN metastases in early (T1/2N1: n = 218) and advanced carcinoma (T3N1 n = 118). We found a difference in median OS between these groups (T3N0: 37 months CI:15.0–58.9; T1/2N1: 60 months CI:42.2–77.8; T3N1: 28 months CI:5.9–50.1, n.s.), but there was no difference in 5YSR (T3N0: 41.1%;CI:21.8–60.3%; T1/2N1: 47.7% CI:37.7–57.7%; T3N1: 38.8% CI:27.7–59.4%, n.s.). There was also no difference in 5RSR, which was 44.3% (T3N0 CI:29–59.3%), 50.4% (T1/2N1 CI:42.6–58.3%), and 47.4% (T3N1 CI:34.0–60.7%).

The presence of lymph-node metastases had a significant impact on overall and relative survival. When lymph-node metastases were not detected, the median OS was 83 months (5YSR: 57.7% CI:54.2–63.7%), whereas in the presence of lymph-node metastases, this was reduced to 24 months (5YSR: 33.0% CI:26.7–40.1%, p < 0.001). The same was found for relative survival after 5 years (5RSR: 59.1% versus 38.0%). Tumour grading also had a significant influence on overall survival; here, the median OS was 118 months (5YSR: 68.6%; 5RSR: 83.7%) for grade 1, which was reduced to 77 months (5YSR: 52.0%; 5RSR: 63.6%) and 44 months (5YSR:42.8%; 5RSR: 52.1%, p < 0,001) for grades 2 and 3, respectively. It should be noted that patients in the G1 group were significantly more likely to be in FIGO stage I, and the lymph nodes were tumour-free in all of them (see Table 3).

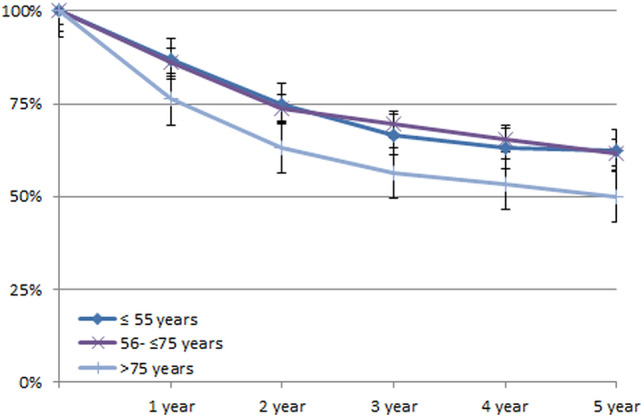

Influence of age on relative survival

To determine the impact of age on relative survival, we classified the patients into 3 groups: <55 years, 55–74 years, and ≥75 years. The groups did not differ in terms of distribution in FIGO stages, the presence of lymph-node metastases, or grading. Nevertheless, we found almost identical relative survival in the two groups of younger patients (5RSR: 62.4 and 61.7%), while this was significantly worse in patients over 75 years of age (5RSR: 49.9%, see Table 4 and Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Clinical findings and relative survival of patients with vaginal cancer according to age groups <55 years, 55 to 74 years, and ≥75 years show a significantly worse survival in the ≥75 group

| All | <55 years | 55–74 years | ≥75 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1915 | 347 (18.1%) | 951 (49.7%) | 617 (32.2%) |

| Median age (years, range) | 69 (18–93) | 48 (18–54) | 66 (55–74) | 80 (75–93) |

| FIGO stage | ||||

| I | 744 (38.6%) | 142 (40.9%) | 374 (39.3%) | 228 (37.0%) |

| II | 340 (17.8%) | 65 (18.7%) | 170 (17.8%) | 105 (17.0%) |

| III | 386 (19.2%) | 59 (17.0%) | 197 (20.7%) | 130 (21.1%) |

| IV | 445 (23.2%) | 81 (23.3%) | 210 (22.0%) | 154 (25.0%) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 486 (25.3%) | 105 (30.3%) | 243 (25.6%) | 137 (22.2%) |

| Grading | ||||

| G1 | 105 (5.4%) | 19 (5.5%) | 48 (5.0%) | 38 (6.1%) |

| G2 | 947 (49.5%) | 175 (50.4%) | 479 (50.4%) | 293 (47.5%) |

| G3 | 697 (36.4%) | 125 (56.0%) | 343 (36.1%) | 229 (37.1%) |

| Morphology | ||||

| SCC | 1651 (86.2%) | 293 (84.4%) | 803 (84.4%) | 555 89.9%) |

| ADC | 160 (8.3%) | 35 (9.7%) | 90 (9.4%) | 35 (5.6%) |

| Relative survival rate (95% confidence interval) | ||||

| 1 year | 83.0% (81.2–84.9%) | 88,5% (85.0–91.9%) | 86.3% (84.0–88.6%) | 75.5% (71.1–79.1%) |

| 3 year | 64.9% (62.4–67.4%) | 67.7% (62.6–72.8%) | 69.4% (65.7–723%) | 56.6% (51.4–61.9%) |

| 5 year | 58.2% (55.3–61.2%) | 62.2% (56.8–678%) | 61.6% (57.8–.65.5%) | 51.2% (44.6–57.8%) |

SCC squamous cell carcinoma, ADC adenocarcinoma

Fig. 3.

The survival plots for patients in the three age groups did not exceed the 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Vaginal cancer is a rare disease, even for most gynaecological oncologists. Using a subset of the national population-based dataset comprising more than 2000 patients with newly diagnosed invasive vaginal neoplasia over a 10-year period, we were able to retrieve detailed and accurate information on the stage distribution and survival of this rare disease. Hence, for the first time, stratified survival data for vaginal carcinoma in Germany from a large cohort are presented. Guidelines—if they exist at all—are usually based on the few available data from smaller, retrospective studies (Diagnostics, Therapy and Follow-up Care of Vaginal Cancer and its Precursors 2018). Due to the low incidence of vaginal carcinoma, the national cancer registries often report only on new cases but not on survival (Siegel et al. 2019).

Unlike cervical carcinoma, there is no organised screening or early detection effort for vaginal carcinoma, although there is a detectable precursor, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN), for which there are several treatment options (Tainio et al. 2016). The progression from VAIN to invasive carcinoma is unpredictable and is reported to be between 1.4 and 15.4% (Sopracordevole et al. 2016). The largest number of patients was diagnosed at FIGO stage I. Nevertheless, in our study, these made up only 38% of the total patients. This was similar to those found in studies (31.4%) as well as in the Danish cancer registry data (35.9%) (Yang et al. 2020; Bertoli et al. 2020). The percentage was slightly higher in a study by Wu and colleagues, in which 42.6% of invasive carcinomas were described as localised (Wu et al. 2018). However, regional lymph-node metastases (25.6%) and distant metastases (16.2%) were found in a relatively large number of patients at first presentation. This was more frequent than in the data reported in the other studies (16.1 and 7.2%, respectively) (Sopracordevole et al. 2016; Gunderson et al. 2013) and in the Danish Cancer Registry (distant metastases 9.6%) (Yang et al. 2020). Additionally, the patients’ age in our study did not differ from the data in the other publications, and only Yang found a significantly younger median age of 63 years for patients with stages I and II disease (Sopracordevole et al. 2016). Analysis of our data showed that 5YSR and RSR were directly dependent on the extent of disease spread as measured by FIGO stages. However, the 5-year RSR of 81.7% for FIGO stage I patients was significantly higher than the data reported in the SEER cancer statistics, which was 66% for localised cancers (Wu et al. 2018). Invasive tumour growth was associated with a reduction in patient survival. 5RSR for tumour growth beyond the vaginal wall (FIGO II) was 59.1% and that for tumour growth into the pelvic wall and/or lymph-node involvement (FIGO III) was 52.0%. This was even worse in stages IVa and IVb, with 36.0% and 11.9%, respectively. Stages II–IVa survival rate corresponds to that of regional cancer in the SEER database (5RSR 55%). It should be noted that even for patients with advanced FIGO stage III disease, nearly 65.6% had survived at least 2 years, and more than half survived 5 years. Yang's study described a disease-specific survival (DSS) for stages I and II of 84 and 73%, respectively, but an unusually good DSS for stage III at 78.7%. However, this rate was reduced to 28.8% in a subgroup in which brachytherapy (BT) had not been performed (Sopracordevole et al. 2016). As confirmed in other studies, although not to this extent (Perez et al. 1988; Reshko et al. 2021), the combination of external beam radiotherapy and BT is recommended for stage III disease (Diagnostics, Therapy and Follow-up Care of Vaginal Cancer and its Precursors 2018; Donato et al. 2012).

The presence of lymph-node metastases was identified as the main factor influencing survival. When analysed for the entire patient population, the 5RSR decreased from 59.1% without nodes to 38% with lymph-node metastases, but was still much better than that in a Japanese database analysis, where it was 61% and 15%, respectively (Yagi et al. 2017). We also found G3 grading to be another influencing factor that was associated with a worse prognosis, confirming data from earlier studies (Kucera and Vavra 1991; Urbański et al. 1996). Analysis of the different age groups showed that patients ≤55 years and between 56 and 75 years had a comparably favourable prognosis, but patients ≥75 years had a poorer overall survival. This is consistent with observations from previous studies where survival was also reduced in older patients (Yang et al. 2020; Perez et al. 1988; Reshko et al. 2021). As the patient groups in our cohort did not differ in tumour-specific data, the question remains whether this is dependent on comorbidity or possibly on the therapy performed. Unfortunately, this question remains unanswered, because the inconsistencies within the tumour registry data collection do not allow any definitive statements to be made in this regard. The analysis of the data concerning melanoma and sarcoma of the vagina shows that, overall, we have a significantly worse survival prognosis than for carcinoma, which also agrees with previously published data (Puri and Asotra 2019).

However, despite the large data set, it is important to point out the limitations of the present study. It is likely that cases are underreported in the registries, which is reflected in the proportion of DCO cases in gynaecological tumours (6.9%) and vaginal carcinomas in particular (8.7%). Another possible source of underreporting of incidences, particularly of advanced stages, could be that vaginal carcinomas with involvement of neighbouring tissues might be counted as vulvar or cervical carcinomas.

Within the registry, information on HPV status and tumour size in mm was not collected, which has also been a source of controversies in the other studies (Chyle et al. 1996; Perez et al. 1999) Unfortunately, we were not able to analyse the influence of surgical, chemotherapeutic, and radiotherapeutic medical interventions on the clinical outcome, as detailed information on therapeutic management is not yet reliably and comprehensively available in the nationwide dataset. In addition, a large proportion of patients (45.2%) lacked information on tumour stage at initial diagnosis and hence had to be excluded from the study. No change in the quality of documentation could be seen during the 10-year period. We can only guess about the reasons for this, but the lack of motivation on the part of the doctors and clinics obliged to document was certainly one of the main problems. Therefore, an additional prospective German vaginal cancer registry study is currently initiated by the Vulva/Vagina Commission of the Association for Gynaecological Oncology (AGO) to obtain more detailed and specifically relevant clinical data, such as treatment modalities for future patients, beyond the cancer registry data set.

Conclusion

The analysis of tumour registry data is an opportunity to obtain survival data from a large cohort of vaginal malignancies. As expected, LN metastases, local growth of an advanced tumour, and G3 grading were associated with a worse prognosis. The fact that older patients have a poorer 5RSR begs the question whether therapy compromises have been made in this group.

Funding

Our research received no funding.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author report no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The use of the data for this study was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Board of the German Centre for Cancer Registry Data, Robert Koch Institute.

Footnotes

Robert Koch-Institute, Department of Epidemiology and Health Monitoring, German Centre for Cancer Registry Data, Berlin, Germany.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams TS, Cuello MA (2018) Cancer of the vagina. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 143(Suppl 2):14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemany L, Saunier M, Tinoco L et al (2014) Large contribution of human papillomavirus in vaginal neoplastic lesions: a worldwide study in 597 samples. Eur J Cancer 50:2846–2854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Joint Committee on Cancer. Vagina. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017:641–47.

- Bertoli HK, Baandrup L, Aalborg GL, Kjaer AK, Thomsen LT, Kjaer SK (2020) Time trends in the incidence and survival of vaginal squamous cell carcinoma and high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia in Denmark - a nationwide population-based study. Gynecol Oncol 158:734–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424 (Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:313.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D, Wu D, Xu Y (2021) Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia in patients after total hysterectomy. Curr Probl Cancer. 45:100687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Cancer Registry Data at the Robert Koch Institute: Database query with estimates of the incidence, prevalence and survival of cancer in Germany based on epidemiological state cancer registry data (DOI: 10.18444/5.03.01.0005.0015.0002)

- Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, Wharton JT, Delclos L (1996) Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 35:891–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM et al (2002) A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol Oncol 84:263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato V, Bellati F, Fischetti M, Plotti F, Perniola G, Panici PB (2012) Vaginal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 81:286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostics, therapy and follow-up care of vaginal cancer and its precursors. Guideline of the DGGG and OEGGG (AWMF 032/42 Oct. 2018 http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/032-042.html

- Ebisch RMF, Rutten DWE, IntHout J et al (2017) Long-lasting increased risk of human papillomavirus-related carcinomas and premalignancies after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol 35:2542–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ederer F, Astell LM, Cutler SJ (1961) The relative survival rate: a statistical methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 6:101–121 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss K, Meyer M (2013) A Windows application for computing standardized mortality ratios and standardized incidence ratios in cohort studies based on calculation of exact person-years at risk. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson CC, Nugent EK, Yunker AC et al (2013) Vaginal cancer: the experience from 2 large academic centers during a 15-year period. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 17:409–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentschke M, Hoffmeister V, Soergel P, Hillemanns P (2016) Clinical presentation, treatment and outcome of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293:415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, Vavra N (1991) Radiation management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: clinical and histopathological variables associated with survival. Gynecol Oncol 40:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino MJ (1991) Vaginal cancer: the role of infectious and environmental factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 165:1255–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CA, Camel HM, Galakatos AE et al (1988) Definitive irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina: long-term evaluation and results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 15:1283–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Garipagaoglu M et al (1999) Factors affecting longterm outcome of irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 44:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri S, Asotra S (2019) Primary vaginal malignant melanoma: a rare entity with review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther 15:1392–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshko LB, Gaskins JT, Metzinger DS, Todd SL, Eldredge-Hindy HB, Silva SR (2021) The impact of brachytherapy boost and radiotherapy treatment duration on survival in patients with vaginal cancer treated with definitive chemoradiation. Brachytherapy 20:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2019) Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:7–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopracordevole F, Barbero M, Clemente N et al (2016) High-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of progression to vaginal cancer: a multicentre study of the Italian Society of Colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal Pathology (SICPCV). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20:818–824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tainio K, Jakobsson M, Louvanto K et al (2016) Randomised trial on treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia-Imiquimod, laser vaporisation and expectant management. Int J Cancer 139:2353–2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualizations, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html Accessed 25 April 2021

- Urbański K, Kojs Z, Reinfuss M, Fabisiak W (1996) Primary invasive vaginal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy: analysis of prognostic factors. Gynecol Oncol 60:16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Matanoski G, Chen VW, Saraiya M, Coughlin SS, King JB, Tao XG et al (2008) Descriptive epidemiology of vaginal cancer incidence and survival by race, ethnicity, and age in the United States. Cancer 113:2873–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi A, Ueda Y, Kakuda M et al (2017) Descriptive epidemiological study of vaginal cancer using data from the Osaka Japan population-based cancer registry: Long-term analysis from a clinical viewpoint. Medicine 96:e7751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Delara R, Magrina J et al (2020) Management and outcomes of primary vaginal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 159:456–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]