Abstract

Purpose

Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) plus bevacizumab is the standard second-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) who are refractory or intolerant to fluoropyrimidines and oxaliplatin. However, the benefits of incorporating fluoropyrimidines into second-line chemotherapy for patients with mCRC who are refractory to fluoropyrimidines are unknown.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated patients with mCRC who were administered irinotecan plus bevacizumab or FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line chemotherapy at a single institution from January 2010 to April 2020. We compared the efficacy and safety of irinotecan plus bevacizumab (IRI group) with those of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (FOLFIRI group).

Results

Of the 255 enrolled patients, 107 (IRI/FOLFIRI group, 31/76 patients) were eligible for analysis. After a median follow-up of 13.1 months (range 1.2–48.4) and 14.3 months (range 0.9–46.5) for the IRI and FOLFIRI groups, respectively, the median progression-free survival was 6.4 months and 5.8 months [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR), 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.50–1.34, p = 0.44] and the median overall survival was 16.6 months and 16.5 months (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI 0.59–1.69; p = 0.97) in the IRI and FOLFIRI groups, respectively. All-grade nausea, stomatitis, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, Grade 3/4 neutropenia, and febrile neutropenia occurred more frequently in the FOLFIRI group than in the IRI group.

Conclusion

Our study suggests omitting fluorouracil from FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as the second-line chemotherapy decreases adverse events without affecting the treatment efficacy in patients with mCRC who are refractory to fluoropyrimidines. Further randomized prospective studies are warranted to validate our result.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Chemotherapy, Fluoropyrimidine, Irinotecan, Bevacizumab

Introduction

Fluorouracil (5-FU)/leucovorin (LV) plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) combined with bevacizumab [antivascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)] is a standard second-line chemotherapeutic regimen with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients who are refractory or intolerant to fluoropyrimidines plus oxaliplatin as first-line treatment. This regimen is supported by the results of the GERCOR V308 phase 3 study, which showed a similar efficacy between 5-FU/LV plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) followed by FOLFIRI and FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX (Tournigand et al. 2004). For patients with mCRC who were refractory to irinotecan and bolus 5-FU/LV, FOLFOX was superior to single-agent oxaliplatin (Rothenberg et al. 2003). However, it is unclear whether the addition of 5-FU to irinotecan enhances efficacy in patients with mCRC who are refractory to 5-FU. Moreover, continuing fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with mCRC who progressed after standard first-line fluoropyrimidines-based treatment may only result in increased side effects. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the effect of omitting 5-FU from FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line chemotherapy for patients with mCRC who were refractory to fluoropyrimidines.

Patients and methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed data for patients with mCRC who received irinotecan plus bevacizumab (IRI group) or FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (FOLFIRI group) as second-line chemotherapy after first-line treatment with fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy at the Aichi Cancer Center Hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) second-line chemotherapy initiated from January 2010 to April 2020, (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 0–2, (3) pathological diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma, (4) available data on KRAS mutational status, (5) refractory to fluoropyrimidines, (6) refractory or intolerant to oxaliplatin, (7) no prior treatment with irinotecan, (8) CT scan within 28 days before the initiation of second-line chemotherapy and application of a standard dose of each drug. Patients in the IRI group received an intravenous infusion of irinotecan of 150 mg/m2 and bevacizumab of 5 mg/kg on day 1, every 2 weeks. Patients in the FOLFIRI group received intravenous infusion of l-leucovorin isomers of 200 mg/m2, a bolus of 5-FU of 400 mg/m2, a 46-h continuous infusion of 5-FU at 2400 mg/m2, irinotecan at 150 mg/m2, and bevacizumab at 5 mg/kg on day 1, every 2 weeks. Resistance to fluoropyrimidines was defined as disease progression during or within 8 weeks of the last dose of first-line fluoropyrimidine therapy, or relapse within 6 months of the last dose of adjuvant fluoropyrimidine therapy. Previous use of bevacizumab as first-line treatment was permitted. Oxaliplatin-containing adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens were regarded as first-line treatment if relapse occurred within 6 months from the last dose of oxaliplatin. In contrast, fluoropyrimidines alone as adjuvant chemotherapy were not considered first-line treatment in any case. All the patients provided written informed consent for receiving chemotherapy. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Aichi Cancer Center Hospital (2020-1-339) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

We reviewed medical records and collected patient characteristics, pathological features, and treatment history with a cutoff date of May 31, 2020. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were defined as the time from the date of initiation of second-line treatment to the date of disease progression and to the date of death from any cause, respectively. Tumor response was assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1). Adverse events were assessed during second-line chemotherapy according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) for PFS and OS were calculated using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model and contained variables with p values < 0.05 in a univariate analysis to reduce the imbalance between groups. Variables included in the univariate and multivariate analyses were as follows: age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65), sex (male vs. female), KRAS (wild-type vs. mutant), BRAF V600E (wild-type vs. mutant), histology (well- or moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma vs. poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, or mucinous carcinoma), previous colorectal resection (yes vs. no), primary tumor location (right-sided vs. left-sided), the number of metastatic sites (1–2 vs. ≥ 3), first-line PFS (< 6 months vs. ≥ 6 months), previous fluoropyrimidine therapy (capecitabine or S-1 vs. fluorouracil), previous use of bevacizumab in first-line treatment (yes vs. no), ECOG PS (0 vs. 1–2), liver metastasis (yes vs. no), lung metastasis (yes vs. no), peritoneal metastasis (yes vs. no), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels (< 300 vs. ≥ 300 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (< 400 vs. ≥ 400 U/L). The cut-off levels of ALP and LDH were decided with reference to the previous reports on the prognostic factors in patients with mCRC (Kohne et al. 2002; Shitara et al. 2011, 2013).

Right-sided tumors arise from the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon, whereas left-sided tumors arise from the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. In addition, subgroup analyses according to these factors were assessed with a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate hazard ratios for treatment effect. We assessed the difference in response rate (RR), disease control rate (DCR), and the proportion of patients with mCRC who were treated with third-line chemotherapy using Fisher’s exact tests. The differences in patient characteristics were evaluated using Fisher’s exact tests. In addition, deepness of response (DpR) was defined as the rate of tumor shrinkage from baseline CT. The relative dose intensity (RDI) of each drug was compared between the two treatment groups using an analysis of variance. Differences in p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using JMP® 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

From January 2010 to April 2020, 255 patients with mCRC received irinotecan plus bevacizumab or FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line chemotherapy after first-line treatment with fluoropyrimidines plus oxaliplatin at the Aichi Cancer Center Hospital. Of the 107 eligible patients, 31 received irinotecan plus bevacizumab (IRI group) and 76 received FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (FOLFIRI group). The reasons for exclusion were as follows: initial dose reduction of irinotecan or 5-FU (n = 119), unknown KRAS status (n = 3), over 28 days from the last CT evaluation (n = 22), not refractory to 5-FU (n = 1), simultaneous triple colorectal cancers (n = 1), change of regimen during first- or second-line treatment before disease progression (n = 1), unknown details regarding first-line treatment (n = 1).

The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The patients in the IRI group contained more patients who received oral fluoropyrimidines and bevacizumab in first-line chemotherapy compared with the FOLFIRI group (65% vs. 34%; p = 0.005, and 84% vs. 63%; p = 0.04, respectively). On the other hand, fewer patients in the IRI group had right-sided tumors (19% vs. 43%, p = 0.03) and liver metastases (42% vs. 62%) compared with those in the FOLFIRI group. Both groups exhibited a similar proportion of the other characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | IRI group | FOLFIRI group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 31 | n = 76 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | 0.13 | ||

| Median (margin) | 67 (33–86) | 62 (34–76) | |

| < 65 | 14 (45) | 48 (63) | |

| ≥ 65 | 17 (55) | 28 (37) | |

| Sex | 0.82 | ||

| Male | 21 (68) | 48 (63) | |

| Female | 10 (32) | 28 (37) | |

| KRAS status | 0.68 | ||

| Wild-type | 17 (55) | 38 (50) | |

| Mutant | 14 (45) | 38 (50) | |

| BRAF V600E status | 0.50 | ||

| Wild-type | 27 (88) | 64 (84) | |

| Mutant | 2 (6) | 8 (11) | |

| Unknown | 2 (6) | 4 (5) | |

| Histology | 0.81 | ||

| Well, mod | 22 (71) | 52 (68) | |

| Por, sig, muc | 8 (26) | 24 (32) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous colorectal resection | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 5 (16) | 24 (32) | |

| No | 26 (84) | 52 (68) | |

| Primary tumor location | 0.03 | ||

| Right-sided | 6 (19) | 33 (43) | |

| Left-sided | 25 (81) | 43 (56) | |

| Metastatic sites | 0.42 | ||

| 1–2 | 23 (74) | 63 (83) | |

| ≥ 3 | 8 (26) | 13 (17) | |

| First-line PFS | 0.50 | ||

| < 6 months | 12 (39) | 23 (30) | |

| ≥ 6 months | 19 (61) | 53 (70) | |

| Previous fluoropyrimidine | 0.005 | ||

| Capecitabine or S-1 | 20 (65) | 26 (34) | |

| Fluorouracil | 11 (35) | 50 (66) | |

| Previous bevacizumab | 0.04 | ||

| Yes | 26 (84) | 48 (63) | |

| No | 5 (16) | 28 (37) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.52 | ||

| 0 | 14 (45) | 41 (54) | |

| 1, 2 | 17 (55) | 35 (46) | |

| Liver metastasis | 0.09 | ||

| Yes | 13 (42) | 47 (62) | |

| No | 18 (58) | 29 (38) | |

| Lung metastasis | 0.67 | ||

| Yes | 17 (55) | 37 (49) | |

| No | 14 (45) | 39 (51) | |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 0.82 | ||

| Yes | 9 (29) | 25 (33) | |

| No | 22 (71) | 51 (67) | |

| ALP | 0.52 | ||

| < 300 U/L | 15 (48) | 30 (40) | |

| ≥ 300 U/L | 16 (52) | 45 (59) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| LDH | 1.00 | ||

| < 400 U/L | 26 (84) | 65 (86) | |

| ≥ 400 U/L | 4 (13) | 9 (12) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

Well well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, mod moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, por poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, sig signet-ring cell carcinoma, muc mucinous carcinoma, PFS progression-free survival, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, ALP alkaline phosphatase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase

Median follow-up time was 13.1 months (range 1.2–48.4) in the IRI group and 14.3 months (range 0.9–46.5) in the FOLFIRI group. On May 31, 2020, 100 patients (93%) experienced disease progression during second-line treatment, which included 29 patients (94%) in the IRI group and 71 patients (93%) in the FOLFIRI group. After disease progression following second-line treatment, 18 patients (62%) and 52 patients (73%) received third-line chemotherapy in the IRI group and in the FOLFIRI group, respectively (p = 0.50), which consisted of trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab (IRI group vs. FOLFIRI group, 33% vs. 25%), regorafenib (6% vs. 6%), irinotecan plus panitumumab or cetuximab (39% vs. 36%), or other treatment regimens (22% vs. 33%).

Efficacy

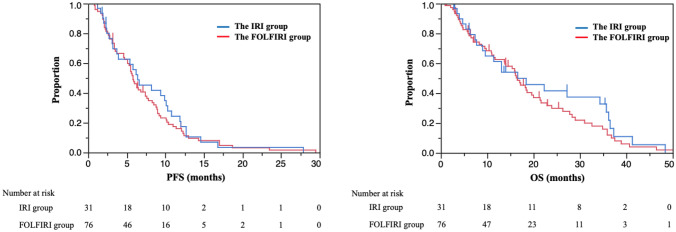

PFS in the IRI group was similar to that in the FOLFIRI group in univariate analysis [median PFS, 6.4 months vs. 5.8 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.57–1.38; p = 0.64] (Fig. 1). Multivariate analysis showed that the aHR for PFS was 0.82 (95% CI 0.50–1.34; p = 0.44) with covariates of previous colorectal resection, number of metastatic sites, ECOG PS, liver metastasis, and LDH levels.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival and progression-free survival. The median follow-up time was 13.1 (range 1.2–48.4) months in the IRI group and 14.3 (range 0.9–46.5) months in the FOLFIRI group. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.4 months in the IRI group and 5.8 months in the FOLFIRI group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57–1.38; p = 0.64; adjusted HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.50–1.34, p = 0.44]. PFS was adjusted for previous colorectal resection, the number of metastatic sites, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), liver metastasis, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Median overall survival (OS) was 16.6 months in the FOLFIRI group versus 16.5 months in the FOLFIRI group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI 0.51–1.32; p = 0.44; aHR, 1.01; 95% CI 0.59–1.69; p = 0.97). OS was adjusted for previous colorectal resection, the number of metastatic sites, liver metastasis, peritoneal metastasis, and LDH levels

OS in the IRI group was similar to that in the FOLFIRI group according to the univariate analysis (median OS, 16.6 vs. 16.5 months; HR, 0.83; 95% CI 0.51–1.32; p = 0.44) (Fig. 1). Multivariate analysis showed that the aHR for PFS was 1.01 (95% CI 0.59–1.69; p = 0.97) with the covariates of previous colorectal resection, number of metastatic sites, liver metastasis, peritoneal metastasis, and LDH levels. The results of the subgroup analyses for PFS and OS according to patient characteristics were consistent with those of the entire population, including primary tumor location and previous use of bevacizumab in first-line treatment that were significantly different between both groups.

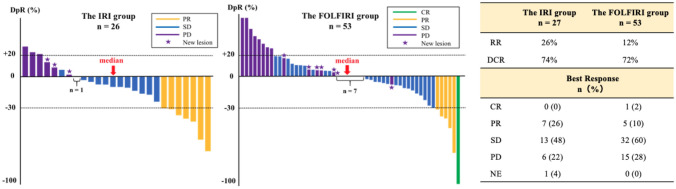

Among the patients with measurable lesions, RR was 26% in the IRI group and 12% in the FOLFIRI group. (p = 0.12). DCR was 74% in the IRI group and 72% in the FOLFIRI group (p = 1.00) (Fig. 2). DpR in the IRI group (median − 10.3%; range − 74 to 30%) was similar to that in the FOLFIRI group (median 0%; range − 100 to 129%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Best response. Among 107 patients, 27 patients in the IRI group and 53 patients in the FOLFIRI group had measurable lesions. The deepness of response (DpR) presented as a waterfall plot was defined as the rate of tumor shrinkage from baseline CT. In the IRI group, the response rate (RR) and disease control rate (DCR) were 26% and 74%, respectively. In the FOLFIRI group, RR and DCR were 12% and 72%, respectively. CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease, NE not evaluated

Relative dose intensity RDI)

RDI of irinotecan and bevacizumab was similar in the IRI and FOLFIRI groups [median (range) RDI of irinotecan, 80% (44–100) vs. 82% (26–100) (p = 0.63); median RDI of bevacizumab, 86% (35–100) vs. 83% (20–100) (p = 0.62)]. Additionally, the median RDI of bolus and infusional 5-FU was 66% (2–100) and 83% (20–100), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative dose intensity

| Drug | IRI group | FOLFIRI group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 31 | n = 76 | ||

| % (range) | % (range) | ||

| Bolus 5-FU | – | 66 (2–100) | – |

| Infusional 5-FU | – | 83 (20–100) | – |

| Irinotecan | 80 (44–100) | 82 (26–100) | 0.63 |

| Bevacizumab | 86 (35–100) | 83 (20–100) | 0.62 |

5-FU fluorouracil, IRI irinotecan, BEV bevacizumab

Safety

All grade nausea (IRI group vs. FOLFIRI group, 32% vs. 59%, p = 0.02), vomiting (13% vs. 29%, p = 0.09), decreased appetite (35% vs. 53%, p = 0.14), stomatitis (13% vs. 36%, p = 0.02), hand-foot syndrome (0% vs. 13%, p = 0.06), neutropenia (42% vs. 79%, p < 0.001), thrombocytopenia (1% vs. 29%, p = 0.002), increased creatinine (6% vs. 21%, p = 0.09), Grade 3/4 neutropenia (23% vs. 59%, p < 0.001), and febrile neutropenia (0% vs. 3%, p = 1.00) occurred more frequently in the FOLFIRI group than in the IRI group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Events | IRI group | FOLFIRI group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 31 | n = 76 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| All grade | Grade ≥ 3 | All grade | Grade ≥ 3 | |

| Hematological | ||||

| Leukocytopenia | 12 (39) | 7 (23) | 44 (58) | 12 (16) |

| Neutropenia | 13 (42) | 7 (23) | 60 (79) | 45 (59) |

| Anemia | 10 (32) | 0 | 32 (42) | 3 (4) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (3) | 0 | 23 (29) | 2 (3) |

| Nonhematological | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | – | 0 | – | 2 (3) |

| ALT increased | 10 (32) | 1 (3) | 24 (32) | 2 (3) |

| Creatinine increased | 2 (6) | 0 | 16 (21) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 20 (65) | 2 (6) | 43 (57) | 5 (7) |

| Fatigue | 12 (39) | 0 | 34 (45) | 0 |

| Nausea | 10 (32) | 0 | 45 (59) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 11 (35) | 0 | 40 (53) | 2 (3) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (13) | 0 | 11 (14) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 12 (39) | – | 33 (43) | – |

| Vomiting | 4 (13) | 0 | 22 (29) | 0 |

| Constipation | 13 (42) | 2 (6) | 25 (33) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 4 (13) | 0 | 27 (36) | 2 (3) |

| HFS | 0 | 0 | 10 (13) | 0 |

| Rash | 5 (16) | 0 | 9 (12) | 0 |

| Hiccup | 4 (13) | 0 | 5 (7) | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 4 (13) | 0 | 7 (9) | 0 |

ALT alanine transaminase, HFS hand-foot syndrome

Discussion

In this retrospective study, the PFS and OS of irinotecan plus bevacizumab were similar to that of FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab with a decrease in adverse events. Tumor shrinkage, RR, and DCR of irinotecan plus bevacizumab were also comparable to the FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab regimen, whereas the RDI of irinotecan and bevacizumab did not show a significant difference in both groups. This indicates that irinotecan plus bevacizumab is an alternative treatment for FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line chemotherapy for patients with mCRC who are refractory to fluoropyrimidines. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports that compared the survival outcomes and safety of irinotecan monotherapy to that of FOLFIRI with the same initial dose of irinotecan in combination with bevacizumab as second-line treatment.

Four clinical trials compared the efficacy and safety of the FOLFIRI combination therapy with those of irinotecan monotherapy as second-line treatment (Becouarn et al. 2001; Graeven et al. 2007; Seymour et al. 2007; Clarke et al. 2011). In summary of these four studies, FOLFIRI showed no improvement in OS (a summary HR, 0.92; 95% CI 0.75–1.14), and limited benefit for PFS (a summary HR, 0.83; 95% CI 0.58–1.19), and reduced alopecia and diarrhea compared to irinotecan monotherapy (Wulaningsih et al. 2016). However, these studies did not evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of continuing 5-FU as the second-line chemotherapy, because the initial dose and administration interval of irinotecan were different in both arms. Kuramochi et al. (2017) reported a phase 2 study of irinotecan plus bevacizumab as second-line chemotherapy for patients with mCRC after the first-line chemotherapy containing fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab. Patients received 150 mg/m2 of irinotecan and 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 2 weeks. In this phase 2 study, PFS and OS of patients treated with irinotecan and bevacizumab were 5.7 and 11.8 months, respectively, and adverse events were manageable. No Grade 3/4 oral mucositis and 3.3% Grade 3/4 fatigue were observed. However, this phase 2 study could not determine whether irinotecan plus bevacizumab was superior to FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab because it was a single-arm study.

FOLFIRI is an inconvenient regimen because it requires 46 h of continuous infusion and central venous catheter implantation. Therefore, combination regimens of oral capecitabine or S-1 and oxaliplatin (CAPOX or SOX) without central venous catheter implantation are frequently administered as first-line chemotherapy in Japan. The results of this study could contribute a treatment strategy for mCRC without central venous catheter implantation from first-line to later-line treatment, with a difference in the proportion of patients receiving oral fluoropyrimidines (65% vs. 34%, IRI group vs. FOLFIRI group). Moreover, this strategy resulted in a reduction of medical expenses and resources. As second-line treatment, other antiangiogenic agents, such as ramucirumab and aflibercept, may be used in combination with FOLFIRI. Our results will be useful when using these drugs in combination with irinotecan (Van Cutsem et al. 2012; Tabernero et al. 2015).

This study had several limitations. First, it was a nonrandomized retrospective study with a small sample size with differences in patient characteristics, especially the primary tumor location and previous use of bevacizumab, and did not have an expected non-inferiority margin. However, the subgroup analysis including these characteristics also showed no significant difference between both groups. Moreover, we established strict eligibility criteria, such as a CT scan within 28 days before initiation of second-line chemotherapy and the standard initial dose of each drug to obtain more accurate results. In addition, BRAF V600E, which is a poor prognostic factor for patients with mCRC, was tested in 94% and 95% of patients in the IRI group and FOLFIRI group, respectively (Tran et al. 2011; Kayhanian et al. 2018) Second, interpreting the frequency of neutropenia and diarrhea was difficult because the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A1 genotype was not evaluated in our study. Approximately 10% of Japanese patients are homozygous or double heterozygous for UGT1A1 *6 and UGT1A1 *28, which are predictive markers of hematological toxicity for irinotecan (Ando et al. 2000; Minami et al. 2007). This frequency may be relatively small, so we considered that the impact of this limitation to our results was not significant. Finally, the effect of newly approved drugs during the eligibility period on OS was not considered, such as trifluridine/tipiracil or regorafenib.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our retrospective study suggests that omitting fluorouracil from FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as the second-line chemotherapy decreases adverse events without affecting the treatment efficacy in patients with mCRC who are refractory to fluoropyrimidines in daily practice. Further randomized prospective studies are warranted to validate our result.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enago (http://www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by YM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by YM and TM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following conflicts of interest: YM received honorania from Takeda, Merck Bio Pharma, and Taiho. TM received honorania from Takeda, Chudai, Merck Bio Pharma, Taiho, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Yakult Honsha, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, and Bristol-myers squibb and research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, and Novartis. TO received honorania from Ono, Bristol-myers squibb, Taiho, MSD, and Eli Lilly. TN received honorania from Eli Lilly. YN received honorania from Yakult Honsha, Taiho, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, and AstraZeneca and research funding from Ono, and Bristol-myers squibb. YN was also a part of the advisory board of Daiichi Sankyo. HB received honorania from Eli Lilly and Taiho and research funding from Ono. HT received honorania from Taiho, Chugai, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Merck Biopharma, and Yakult Honsha. SK received honorania from Bristol-myers squibb, Chugai, Merck Bio Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Ono, Bayer, Taiho, and Esai and research funding from Ono, Taiho, MSD, Nobelpharma, Bristol-myers squibb, Eli Lilly, and Chugai. MT received honorania from EA Pharma. KM received honorania from Ono, Chugai, Takeda, Taiho, Sanofi, Bristol-myers squibb, Eli Lilly, and Bayer; research funding from Solasia Pharma, Merck Serono, Daiichi Sankyo, Parexel International, Pfizer, MSD, Amgen, ONO, Astellas, Sanofi, Taiho, and Esai; and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Ono, and Amgen. KM was also a part of the advisory boards of Ono, MSD, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, and Solasia Pharma.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board (Aichi Cancer Center Hospital IRB, ref, 2020-1-339). The institutional review board approved the waiving of informed consent because of the observational retrospective study design, with an optout opportunity provided on the institution’s website.

Consent to participate

Informed consent of participants was waived by the ethics committee as a substitute opt-out.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ando Y, Saka H, Ando M, Sawa T, Muro K, Ueoka H, Yokoyama A, Saitoh S, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y (2000) Polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene and irinotecan toxicity: a pharmacogenetic analysis. Cancer Res 60(24):6921–6926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becouarn Y, Gamelin E, Coudert B, Négrier S, Pierga JY, Raoul JL, Provençal J, Rixe O, Krisch C, Germa C, Bekradda M, Mignard D, Mousseau M (2001) Randomized multicenter phase II study comparing a combination of fluorouracil and folinic acid and alternating irinotecan and oxaliplatin with oxaliplatin and irinotecan in fluorouracil-pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 19(22):4195–4201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SJ, Yip S, Brown C, van Hazel GA, Ransom DT, Goldstein D, Jeffrey GM, Tebbutt NC, Buck M, Lowenthal RM, Boland A, Gebski V, Zalcberg J, Simes RJ (2011) Single-agent irinotecan or FOLFIRI as second-line chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer; results of a randomised phase II study (DaVINCI) and meta-analysis [corrected]. Eur J Cancer 47(12):1826–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeven U, Arnold D, Reinacher-Schick A, Heuer T, Nusch A, Porschen R, Schmiegel W (2007) A randomised phase II study of irinotecan in combination with 5-FU/FA compared with irinotecan alone as second-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Onkologie 30(4):169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayhanian H, Goode E, Sclafani F, Ang JE, Gerlinger M, Gonzalez de Castro D, Shepherd S, Peckitt C, Rao S, Watkins D, Chau I, Cunningham D, Starling N (2018) Treatment and survival outcome of BRAF-mutated metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective matched case-control study. Clin Colorect Cancer 17(1):e69–e76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KohneKöhne CH, Cunningham D, Di Costanzo F, Glimelius B, Blijham G, Aranda E, Scheithauer W, Rougier P, Palmer M, Wils J, Baron B, Pignatti F, Schöffski P, Micheel S, Hecker H (2002) Clinical determinants of survival in patients with 5-fluorouracil-based treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a multivariate analysis of 3825 patients. Ann Oncol 13(2):308–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H, Ando M, Itabashi M, Nakajima G, Kawakami K, Hamano M et al (2017) Phase II study of bevacizumab and irinotecan as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 79(3):579–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami H, Sai K, Saeki M, Saito Y, Ozawa S, Suzuki K, Kaniwa N, Sawada J, Hamaguchi T, Yamamoto N, Shirao K, Yamada Y, Ohmatsu H, Kubota K, Yoshida T, Ohtsu A, Saijo N (2007) Irinotecan pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and UGT1A genetic polymorphisms in Japanese: roles of UGT1A1*6 and *28. Pharmacogenet Genom 17(7):497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg ML, Oza AM, Bigelow RH, Berlin JD, Marshall JL, Ramanathan RK et al (2003) Superiority of oxaliplatin and fluorouracil-leucovorin compared with either therapy alone in patients with progressive colorectal cancer after irinotecan and fluorouracil-leucovorin: interim results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 21(11):2059–2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour MT, Maughan TS, Ledermann JA, Topham C, James R, Gwyther SJ, Smith DB, Shepherd S, Maraveyas A, Ferry DR, Meade AM, Thompson L, Griffiths GO, Parmar MK, Stephens RJ, National Cancer Research Institute Colorectal Clinical Studies Group (2007) Different strategies of sequential and combination chemotherapy for patients with poor prognosis advanced colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370(9582):143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitara K, Matsuo K, Yokota T, Takahari D, Shibata T, Ura T, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, Sato Y, Najima M, Muro K (2011) Prognostic factors for metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy. Gastrointest Cancer Res 4(5–6):168–172 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitara K, Yuki S, Yamazaki K, Naito Y, Fukushima H, Komatsu Y, Yasui H, Takano T, Muro K (2013) Validation study of a prognostic classification in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who received irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 139(4):595–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL, Obermannova R, Bodoky G, Garcia-Carbonero R, Ciuleanu TE, Portnoy DC, Van Cutsem E, Grothey A, Prausová J, Garcia-Alfonso P, Yamazaki K, Clingan PR, Lonardi S, Kim TW, Simms L, Chang SC, Nasroulah F, R. S. (2015) Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 16(5):499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang ZQ, Lieu CH, Agarwal A, Maru DM, Sieber O, Desai J (2011) Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 117(20):4623–4632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournigand C, Andre T, Achille E, Lledo G, Flesh M, Mery-Mignard D et al (2004) FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol 22(2):229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, Prenen H, Prausová J, Macarulla T, Ruff P, van Hazel GA, Moiseyenko V, Ferry D, McKendrick J, Polikoff J, Tellier A, Castan R, Allegra C (2012) Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol 30(28):3499–3506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulaningsih W, Wardhana A, Watkins J, Yoshuantari N, Repana D, Van Hemelrijck M (2016) Irinotecan chemotherapy combined with fluoropyrimidines versus irinotecan alone for overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced and. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016(2):CD008593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.