Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Given equivocal results related to overall survival (OS) for patients with multiple primary melanomas (MPMs) compared with those with single primary melanomas (SPMs) in previous reports, the authors sought to determine whether OS differs between these 2 cohorts in their center using their UPCI-9 6–99 database. Secondary aims were to assess the differences in recurrence-f ree survival (RFS). In a subset of patients, transcriptomic profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was performed to assess disease-associated genes of interest.

METHODS:

This retrospective case-controlled study included patients with MPMs and age-, sex-, and stage-matched controls with SPMs at a 1:1 ratio. Cox regression models were used to evaluate the effect of the presence of MPMs on death and recurrence. NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling was used to assess peripheral blood immune status in patients.

RESULTS:

In total, 320 patients were evaluated. The mean patient age was 47 years; 43.8% were male. Patients with MPMs had worse RFS and OS (P = .023 and P = .0019, respectively). The presence of MPMs was associated with an increased risk of death (hazard ratio [HR], 4.52, P = .0006), and increased risk of disease recurrence (HR, 2.17; P = .004) after adjusting for age, sex, and stage. The degree of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) was different between the first melanoma of MPMs and SPMs. Expression of CXCL6 and FOXJ1 was increased in PBMCs isolated from patients with MPMs.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with MPMs had worse RFS and OS compared with patients with SPMs. Immunologic differences were also observed, including TIL content and expression of CXCL6/FOXJ1 in PBMCs of patients with MPMs, which warrant further investigation.

Keywords: immune profile, melanoma, multiple primary, survival, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

INTRODUCTION

Patients with melanoma are at increased risk (1%−8 %) of subsequent melanoma based on multiple reports, with the highest risk occurring within 2 years of first primary melanoma diagnosis.1,2 Subsequent melanomas tend to be thinner, are diagnosed at stage I or stage 0 (in situ) and are more likely to present in different anatomical locations.3 The impact of subsequent melanomas on patient prognosis remains poorly resolved.

Studies evaluating the overall survival (OS) in patients with multiple primary melanomas (MPMs) have yielded conflicting results. Large population-b ased Dutch and Australian studies suggest reduced survival among patients with MPMs versus single primary melanoma (SPMs), whereas a single-c enter Australian study reported improved survival among patients with MPMs.4–6 In the subset of patients with Breslow thickness >4 mm, improved melanoma-specific survival has been reported in patients with MPMs in an international Genes, Environment and Melanoma study.7 A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data analysis argued for comparable OS among patients with MPMs and SPMs.8

With the advent of multiple new effective immunotherapy approaches for patients with melanoma and a significant improvement in patient survival in comparison to historical data, it has become increasingly important to address the prognostic impact of MPMs on OS and its potential value in determining patient management strategies.9

Developing peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC)–based biomarkers of disease prognosis is of significant interest, given the less invasive nature of the sampling procedure (vs biopsy) and the theoretical advantage such biomarkers might provide as a tool for systemic dynamic monitoring of patients over time. Indeed, PBMC gene expression profiling has led to the identification of differentially expressed genes reflective of disease status in patients with a range of solid tumors.10–12 In a small cohort of patients with melanoma receiving ipilimumab, PBMC displayed decreases in various immune subtypes in comparison to healthy donors’ PBMC.13

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether OS differs between patients with MPMs versus SPMs. Secondary objectives include assessment of recurrence-free survival (RFS) differences among these 2 cohorts, description of metastatic patterns, and pathological characteristics of patients with MPMs. We also explored the PBMC transcriptomic profile in a subset of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

All patients were enrolled in the Melanoma Center of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center biospecimen repository under protocol UPCI 96–99 (1996–2021), supported in part by the Melanoma and Skin Cancer Program SPORE (P50CA254865) within the time windows 2008 to 2019 and 2021 to 2026. Patients provided written informed consent for enrollment into this database and biospecimen repository. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board.

This case-control study included cases with MPMs and age-, sex-, and stage-matched controls with SPMs at a 1:1 ratio. Patients who had 2 or more primary melanomas (invasive and/or melanoma in situ [MIS]) were included in the MPM cohort. If a patient with MPM had both MIS and invasive melanoma, matching was performed based on the stage of the invasive melanoma in that patient. Age matching was performed based on patient age at diagnosis of first melanoma (<50 vs ≥50 years). The information regarding diagnosis of first and subsequent melanomas, staging, follow-up data, location of melanoma, age at diagnosis of first melanoma, and patient sex was obtained from an electronic medical record review. Follow-u p data including dead/alive status, presence or absence of disease recurrence, and site of recurrent disease was also obtained from the electronic medical record review. Pathological characteristics such as histology, Breslow thickness, the degree of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and presence or absence of ulceration were retrieved from patient pathology reports. TILs were categorized as 1 of 3 categories: 1) brisk, defined as TILs abundantly present across the base of the tumor; 2) absent, defined as a complete absence of lymphocyte infiltration; and 3) nonbrisk, defined as cases not conforming to either the brisk or absent categories. We also report the mutational status of BRAF, NRAS, and NF in the patient’s melanoma(s), if known.

Immune Profiling

Peripheral blood was aseptically collected by venipuncture into sodium heparin vacutainer tubes and processed immediately for PBMC extraction. Whole blood was transferred into sterile 50-mL conical tubes and diluted 1:2 with Hanks phosphate-buffered saline (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ten milliliters of lymphocyte separation media were underlaid and tubes were centrifuged at 880g for 25 minutes. The interface layer containing mononuclear cells was isolated by aspiration, with the recovered cells washed with phosphate-buffered saline by centrifugation (550g for 12 minutes). After discarding supernatants, the cell pellet was resuspended in Iscove’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich; ie, freezing medium). Approximately 107 cells in 1 mL of freezing medium were transferred into 1.5-mL cryovials (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with vials then placed in a Nalgene Cryo Freezing Container with 70% ethanol and then stored in a −140°C freezer until time of analysis.

The NanoString nCounter PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (NanoString Technologies Inc, Seattle, Washington) was used to assess the transcriptomic profile of cryopreserved PBMCs. This is a multiplexed gene expression panel that targets 770 genes of immuno-oncologic interest. The RNA extraction from cells was performed using Trizol by the Genomics Research Core of the University of Pittsburgh. Recovered RNA was then analyzed using the Nanostring nCounter technology and nSolver analysis software.

Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, we report mean or median and interquartile range. For categorical variables, we report numbers and percentages. We used a t test for comparison of continuous variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for nonnormally distributed variables. For categorical variables, we used the χ2 test with large numbers and the Fisher exact test for those with a small number. The logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between recurrence and variables of interest. OS was defined as elapsed time from date of diagnosis until date of death or last follow-up. RFS was defined as elapsed time from date of diagnosis until disease recurrence. The survival plots were created using the Kaplan-Meier approach. Log-rank tests were performed to compare RFS and OS between groups. The Cox regression model was used to evaluate the effect of MPMs on OS and RFS adjusting for age, sex, and stage of melanoma at diagnosis. If the patient with MPM was diagnosed with MIS and later developed invasive melanoma, the staging of invasive melanoma was included in the analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were reported for SPM or MPM status, age, sex, and stage. The relationship between MPMs and expression of each raw gene was studied with a univariate logistic regression model. The raw gene expression data were log-transformed before analysis. All genes with univariate P values < 0.2 were used as candidates for the multivariable logistic regression model selection. The selection was done using alpha levels of 0.05 for insertion and 0.15 for deletion. After finding genes associated with MPMs, we aimed to find optimal cutoff values for each of them. We plotted receiver operating characteristic curves and evaluated the performance of these cutoff points by fitting univariate logistic regression models for MPMs and selected the cutoff value, which maximized the Youden index. The multivariable model with binary predictors was also used. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 for gene expression profile analysis and R 4.1.0 for survival analysis.

RESULTS

In total, we enrolled 160 patients with MPMs and 160 patients with SPMs. The baseline characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. The mean ages at diagnosis for patients with SPMs and MPMs were 46 and 48 years, respectively. A total of 43.8% of patients were male in both groups. Seventeen patients (10.7%) with MPMs had MIS as an initial diagnosis of melanoma. Of these patients, 70.5% developed subsequent invasive melanoma, with all but 1 patient having stage I melanoma. A total of ~20% of melanomas were stage III. Among patients with stage III disease, 96.4% versus 86.2% of patients (P = .371) received systemic adjuvant therapy in the SPM and MPM groups, respectively. In comparison to first melanomas, subsequent melanomas were thinner, less frequently ulcerated, and had divergent histology (different histology such as superficial spreading vs nodular vs acral lentiginous morphotype between first and subsequent melanomas). They were more likely to be diagnosed at stage I or MIS (Table 2). Forty-one of 160 (26.1%) of subsequent melanomas were MIS. Overall, 96.1% of patients had the same degree or an increase in TIL content in subsequent melanomas. The degree of TIL infiltration was different between the first melanoma of patients with MPMs and those with SPMs, with MPM initial primaries having a lower proportion of brisk TIL (9.8% vs 26.5%, P = .02).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients (N = 320)

| Variable | SPMs (N = 160) | MPMs (N = 160) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.42 (14.82) | 47.83 (16.31) | .42 |

| Sex, No. (%) | 1 | ||

| Male | 70 (43.8) | 70 (43.8) | |

| Female | 90 (56.2) | 90 (56.2) | |

| First melanoma stage, No. (%) | .06 | ||

| I | 92 (57.9) | 81 (50.9) | |

| II | 33 (20.8) | 32 (20.1) | |

| III | 29 (18.2) | 29 (18.2) | |

| MIS | 5 (3.1) | 17 (10.7) | |

| Histology, No. (%) | .52 | ||

| Acral lentiginous | 2 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | |

| Superficial spreading | 76 (69.1) | 100 (72.5) | |

| Desmoplastic | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Nodular | 18 (16.4) | 13 (9.4) | |

| Other | 13 (11.8) | 20 (14.5) | |

| Location, No. (%) | .31 | ||

| Head and neck | 20 (12.6) | 24 (15.3) | |

| Lower extremity | 32 (20.3) | 40 (25.5) | |

| Upper extremity | 38 (24.1) | 34 (21.7) | |

| Trunk | 68 (43.0) | 58 (36.9) | |

| Ulceration, No. (%) | .46 | ||

| Yes | 29 (19.1) | 23 (15.2) | |

| Breslow thickness, median (IQR), mm | 1.10 (0.53–2.30) | 0.85 (0.45–1.70) | .04 |

| Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, No. (%) | .02 | ||

| Absent | 10 (10.2) | 11 (13.4) | |

| Nonbrisk | 62 (63.3) | 63 (76.8) | |

| Brisk | 26 (26.5) | 8 (9.8) | |

| Molecular testing, No. (%) | .24 | ||

| CDKN2A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | |

| NRAS G13R | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | |

| NRAS G61K | 2 (6.9) | 1 (2.7) | |

| NRAS G61L | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.8) | |

| NRAS G61R | 5 (17.2) | 2 (5.4) | |

| BRAF V600E | 9 (31.0) | 14 (37.8) | |

| BRAF V600K | 3 (10.3) | 1 (2.7) | |

| BRAF wild type | 10 (34.5) | 12 (32.4) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile ratio; MIS, melanoma in situ; MPMs, multiple primary melanomas; NA, not applicable; SPMs, single primary melanomas.

TABLE 2.

First Versus Subsequent Melanoma in Patients With Multiple Primary Melanoma

| Variable | First Melanoma | Subsequent Melanoma | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breslow thickness, median (IQR), mm | 0.85 (0.45–1.70) | 0.40 (0.05–0.79) | <.001 |

| Ulceration, No. (%) | .01 | ||

| Yes | 23 (15.2%) | 9 (5.9%) | |

| Histology, No. (%) | .001 | ||

| Acral lentiginous | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Superficial spreading | 100 (72.5) | 89 (63.1) | |

| Desmoplastic | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.8) | |

| Nodular | 13 (9.4) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Other | 20 (14.5) | 42 (29.8) | |

| Stage, No. (%) | <.001 | ||

| I | 81 (50.9) | 100 (63.7) | |

| II | 32 (20.1) | 13 (8.3) | |

| III | 29 (18.2) | 3 (1.9) | |

| MIS | 17 (10.7) | 41 (26.1) | |

| Location, No. (%) | .83 | ||

| Head and neck | 24 (15.3) | 20 (12.7) | |

| Lower extremity | 40 (25.5) | 38 (24.2) | |

| Upper extremity | 34 (21.7) | 40 (25.5) | |

| Trunk | 58 (36.9) | 58 (36.9) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MIS, melanoma in situ.

During our first analysis, we included only those patients with invasive melanoma and excluded those who had MIS in both groups. The mean follow-up time was not different between the 2 groups (109.19 vs 107.32 months, P = .84). During this follow-up timeline, 26 of 264 patients (9.85%) died and 42 of 264 patients (15.91%) developed recurrent disease among all patients evaluated without MIS. The rate of disease recurrence was higher in patients with MPMs versus SPMs (29.4% vs 14.8%, P = .013), with death occurring in 17.4% and 4.5% (P = .007) of patients with MPMs and SPMs, respectively. Patients with MPMs had a 2-f old higher incidence of visceral metastasis, 15.6% versus 7.1%, (P = .045). There was no significant difference in the incidence of lymph node metastasis (7.3% vs 5.8% in MPM and SPM groups, respectively; P = .81).

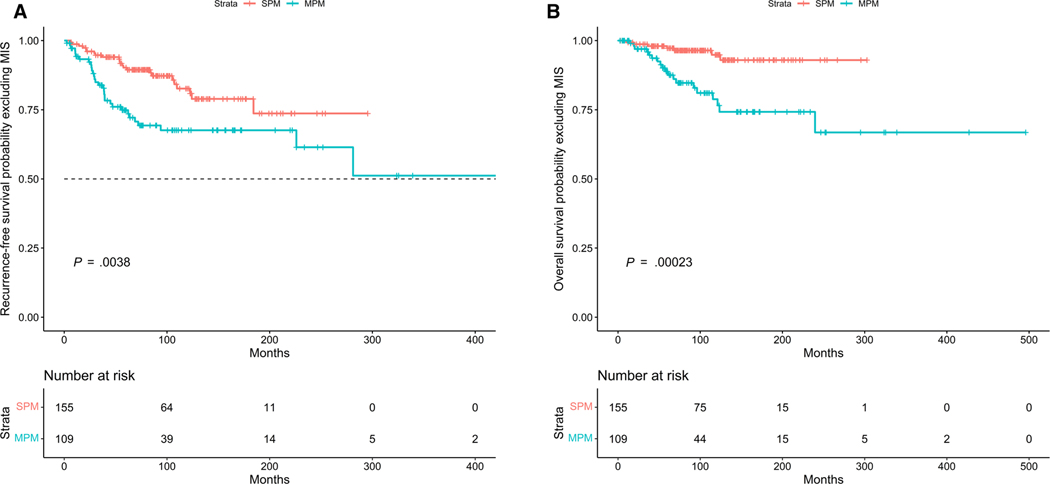

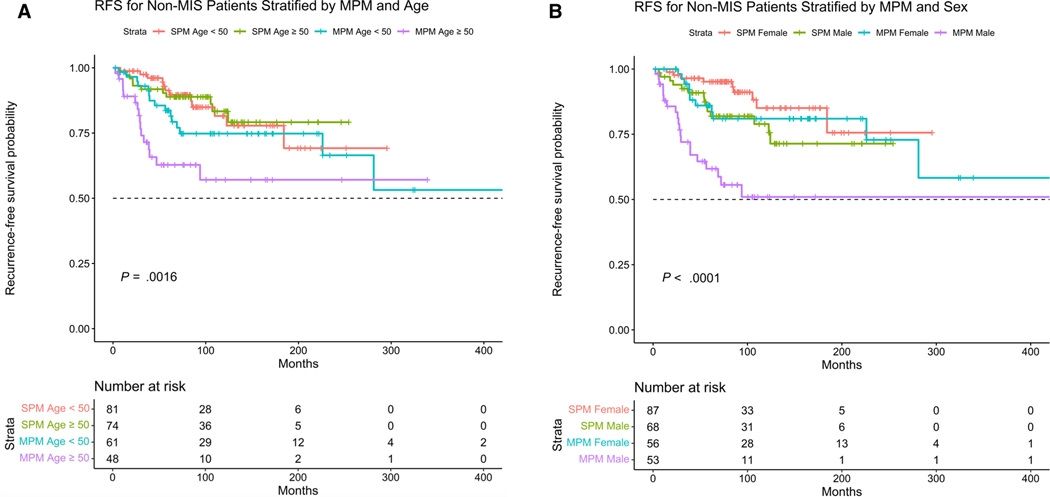

The patients with MPMs had worse RFS and OS (log-rank test P = .0038 and P = .00023, respectively) (Fig. 1A,B). The presence of MPM was associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence after adjusting for age, sex, and stage (HR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.37–4 .17; P = .002). Male sex, increasing age, and presence of stage III were also associated with increased risk of disease recurrence. MPM was associated with increased risk of death after adjusting for age, sex, and stage of melanoma (HR, 5.13; 95% CI, 2.12–12.44; P < .001). We further stratified patients by age and sex along with presence/absence of MPMs and determine worse RFS in patients with MPMs and age >50 years, and males with MPMs (P = .0016 and P < .0001, respectively) (Fig. 2A,B).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing RFS in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas excluding patients with MIS. The patients with MPM had worse RFS (log-r ank test P = .0038). (B) Kaplan-M eier curves showing (S) in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas excluding patients with melanoma in situ. The patients with MPMs had worse OS (log-r ank test P = .00023). MIS indicates melanoma in situ; MPMs, multiple primary melanomas; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-f ree survival; SPM, single primary melanoma.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing RFS in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas excluding patients with melanoma in situ and stratifying by age. The patients with MPMs and ≥50 years old had worse RFS (log-rank test P = .0016). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing RFS in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas excluding patients with melanoma in situ and stratifying by sex. The male patients with MPM had worse RFS (log-r ank test P < .0001). MIS indicates melanoma in situ; MPMs, multiple primary melanomas; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SPMs, single primary melanomas.

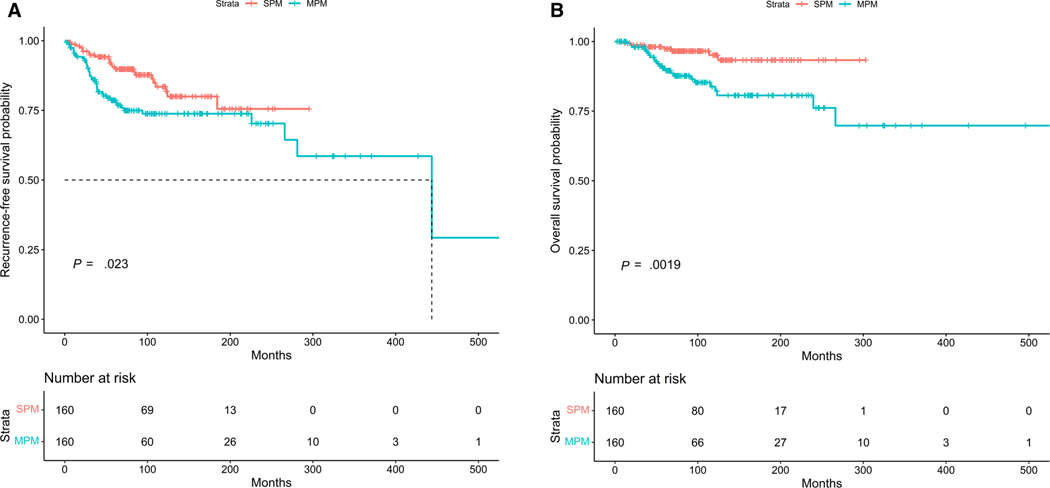

Next, we performed survival analyses including patients with MIS as well and accounted for the highest invasive stage of melanoma in patients with MPMs. The patients with MPMs had worse RFS and OS (log-rank test P = .023 and P = .0019 respectively) (Fig. 3A,B). Among all patients, presence of MPM was associated with an increased risk of recurrence (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.27–3.70; P = .004) and death (HR, 4.52; 95% CI, 1.90–10.74; P = .0006) after adjusting for age, sex, and worst stage of melanoma. The factors associated with disease recurrence among all patients are summarized in Table 3. Increasing age, male sex, presence of ulceration, and stage III disease were associated with increased risk of recurrent disease. Conversely, brisk TILs, Breslow thickness <1 mm, and superficial spreading histology were associated with decreased risk of recurrence. Among patients who had molecular profiling available, there was no difference in RFS (log-rank P = .99) (Supporting Fig. 1).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Kaplan-M eier curves showing RFS in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas. The patients with MPM had worse RFS (log-r ank test P = .023). (B) Kaplan-M eier curves showing OS in patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas. The patients with MPM had worse OS (log-rank test P = .0019). MPMs indicate multiple primary melanomas; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SPM, single primary melanoma.

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated With Melanoma Recurrence in Patients With Single and Multiple Primary Melanomas

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | .01 |

| Male | 2.73 | 1.55–4.89 | <.001 |

| Brisk TILs | 0.12 | 0.02–0.59 | .02 |

| Presence of ulceration | 3.29 | 1.70–6.32 | <.001 |

| Breslow thickness <1 mm | 0.07 | 0.02–0.18 | <.001 |

| Stage III | 6.11 | 1.57–40.6 | .02 |

| Superficial spreading | 0.17 | 0.03–0.99 | .04 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

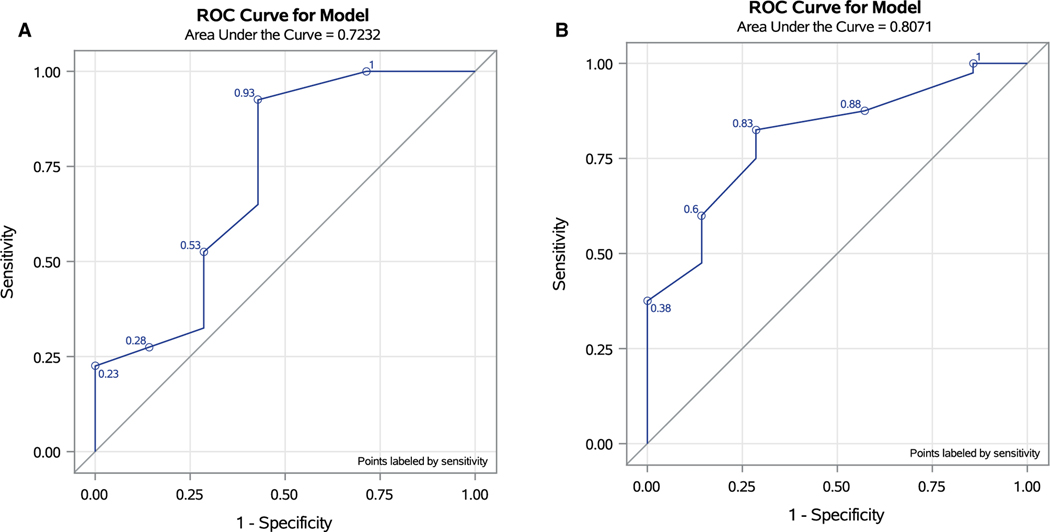

We investigated whether systemic immune status is reflective of risk to develop MPMs via further analyzing the transcriptomic profile of PBMCs isolated from 40 patients with MPMs versus 10 patients with SPMs. Of the 50 samples, 3 did not pass quality control because of low RNA quality and were excluded from the final analysis. Our analysis of patient PBMC suggests that patients with MPMs exhibit increased expression of CXCL6 and FOXJ1. Supporting Table 1 includes differentially expressed genes associated with MPMs. In the final multivariable analysis, only FOXJ1 and CXCL6 were significantly associated with MPMs (Table 4). For log CXCL6, the cutoff value was 1.95 with sensitivity and specificity of 0.93 and 0.57, respectively, for prediction of MPMs. The cutoff value of 2.20 for log (FOXJ1) had a sensitivity and specificity of 0.83 and 0.71, respectively (Fig. 4).

TABLE 4.

FOXJ1 and CXCL6 Association With Multiple Primary Melanoma Abbreviations: MPMs, multiple primary melanomas; OR, odds ratio; SPMs, single primary melanomas.

| Group | MPMs | SPMs | Total | OR (95% CI), P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Log (FOXJ1) >2.20 | 31 (94%) 2 (6%) | 33 | 8.61 (1.42–52.09), P = .02 | |

| Log (FOXJ1) ≤2.20 | 9 (64%) | 5 (36%) | 14 | |

| Total | 40 | 7 | 47 | |

| CXCL6 >1.95 | 34 (92%) 3 (8%) | 37 | 7.56 (1.34–42.63), P = .02 | |

| CXCL6 ≤1.95 | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | 10 | |

| Total | 40 | 7 | 47 | |

| Multivariable analysis | ||||

| Log (FOXJ1) >2.20 vs not | 9.28 (1.28–67.06), P = .03 | |||

| Log (CXCL6) >1.95 vs not | 8.24 (1.15–58.85), P = .03 | |||

FIGURE 4.

(A,B) Receiver operating characteristic curve for CXCL6 and FOXJ1 as predictive biomarkers in the setting of multiple primary melanomas (MPMs). For CXCL6, the area under the curve was 0.72 with sensitivity and specificity of 0.93 and 0.57 respectively, for prediction of MPMs. For FOXJ1 area under the curve was 0.81 with sensitivity and specificity of 0.83 and 0.71, respectively. MPMs indicate multiple primary melanomas.

DISCUSSION

Beyond the rising incidence of primary cutaneous melanoma, a recent report from the Swedish Cancer Registry showed an increasing trend for development of subsequent melanomas as well.14–16 It has therefore become important to study the effect of MPM on disease course, particularly in the context of current guidelines that do not differentiate follow-up or overall management strategies between patients with SPMs and MPMs.

A fraction of previous studies has reported that the presence of MPM is associated with improved overall survival.4,7 This was based on an argument for enhanced potential immunization among patients with MPMs. In a study by Saleh et al, histologic regression was noted in 33% of subsequent melanomas in comparison to none of first melanomas in those with MPMs or melanomas of patients with SPMs. Subsequent melanomas also displayed decreased areas of MART-1–positive staining (ie, antigen-loss variants).17 In contrast, our study suggests an increased risk of death in patients with MPM versus SPM. We observed that the presence of MPM was also associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence and a 2-fold higher incidence of visceral metastasis. Consistent with our study, Youlden et al recently reported decreased 10-year melanoma-specific survival in patients with MPM, with an HR of 2.01 for death among patients with 2 melanomas, which increased to 2.91 for patients with 3 melanomas.18 A report from the Netherlands Cancer Registry also described inferior survival of patients with MPMs (HR, 1.32).19

To investigate the underlying etiology of the observed worse outcomes among patients with MPMs, we further studied the clinical, pathological, and immunological characteristics of these patients. Consistent with other studies, subsequent melanomas were found to be thinner and more likely to be noninvasive.20 Subsequent melanomas were also less often ulcerated and exhibited differing histology versus first primary melanomas. Although previous studies have discussed clinical and occasional pathological features of MPM, no study to date has described TIL and peripheral blood immune profiling in these patients.1,2 In this series of patients with MPMs, they were found to have a lower proportion with brisk TIL in the first melanoma, which could play a role in worse outcomes in these patients because of ongoing limitations in immune surveillance. TIL content assessed between the 2 instances of melanoma were found to be the same (nonbrisk) or increased (absent → nonbrisk or nonbrisk → brisk) in subsequent melanomas, suggesting that first melanomas do not regularly lead to a state of immune tolerance or to the inability of the host to respond to subsequent melanomas.

The absence of differences in RFS among patients with various molecular profiling is likely due to small sample size and that patients with early-stage melanoma had no molecular profile available; only small subset of patients had molecular profiling either at the time of disease recurrence or after being diagnosed with stage III melanoma because in our institution molecular profiling of early-stage melanoma (I, II) is not routinely performed.

The granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 (GCP-2)/CXCL6 is a chemokine produced by myeloid cells, including conventional dendritic cells and follicular dendritic cells, which may promote tumor growth and metastasis via enhanced neutrophil recruitment and promotion of angiogenesis.21,22 Interestingly, GCP-2–expressing melanomas exhibit increased levels of infiltrating neutrophils, increased expression of gelatinase B, and increased angiogenesis, even at early disease stages. Administration of neutralizing/blocking monoclonal antibodies against murine GCP-2 results in reduced growth and metastasis to lymph nodes in murine melanoma models.23 GCP-2 has also been reported to serve as an autocrine growth factor for melanomas in addition to serving as a proangiogenic factor.24 FOXJ1 is a transcriptional activator primarily expressed by T cells, where it serves to downregulate T-cell activity and promote tolerance via repression of nuclear factor–κB signaling. FOXJ1-deficient chimeras demonstrated robust systemic autoimmune inflammation.25 In addition to its role in cellular responses, FOXJ1 also appears to be involved in dysregulated B-cell homeostasis and autoimmune humoral responses through its ability to antagonize nuclear factor–κB and IL-6.26 Notably, FOXJ1 has been reported to be overexpressed in prostate, bladder, and renal cell cancers, where it is associated with poorer prognosis.27–29

Our study has several strengths. The study included all patients with MPMs who were diagnosed and followed at a single referral institution, eliminating the potential confounding effects of multi-institutional factors on study results. We performed age-, sex-, and stage-matched studies within the biospecimen repository of this institution. These factors are important to account for because we previously reported that patients with MPMs were younger at time of diagnosis of first primary melanoma, and more likely to be diagnosed at stage 0 or 1.3 Our MPM cohort also shows female predominance, whereas melanoma has been classically viewed as a male-biased disease.15 The major limitations included the number of samples reporting TILs and with PBMCs available for transcriptional profiling, although these results were exploratory in nature.

In summary, we report that patients with MPMs have a worse OS compared with patients with SPMs. They also had an increased risk of disease recurrence and a higher incidence of visceral metastases. RFS was worse in male patients with MPMs and patients with MPMs >50 years old. These results argue for closer surveillance for patients with MPMs. Differences in TIL and the differential expression of CXCL6/FOXJ1 (protumor/immunosuppressive) factors in the peripheral blood warrant further investigation as potential biomarkers of risk to develop subsequent melanomas.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING SUPPORT

Melanoma Center Internal Funding.

We thank Min Mo, Erica Fong, Amy Simsik, and Debby Hollingshead for their guidance and technical support. This project used the University of Pittsburgh Melanoma and Skin Cancer Program Biospecimen Repository (UPCI 96-9 9) under Melanoma Center and SPORE P50 P50CA254865 funding, HSCRF Genomics Research Core (RRID: SCR_018301 RNA isolation), and NanoString services.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

John M. Kirkwood has served as a consultant for BMS, Checkmate, Novartis, and Amgen Inc; has received research support from BMS, Amgen Inc, Checkmate, Castle Biosciences Inc, Immunocore LLC, Iovance, and Novartis; has received payment or honoraria from BMS; and has received travel reimbursement from BMS, Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis. The other authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrone CR, Ben Porat L, Panageas KS, et al. Clinicopathological features of and risk factors for multiple primary melanomas. JAMA. 2005;294:1647–1654. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwa C, Price LS, Belitskaya-Levy I, et al. Single versus multiple primary melanomas. Cancer. 2012;118:4184–4192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karapetyan L, Yang X, Wang H, et al. Indoor tanning exposure in association with multiple primary melanoma. Cancer. 2021;127:560–568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doubrovsky A, Menzies SW. Enhanced survival in patients with multiple primary melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1013–1018. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.8.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Sharouni MA, Witkamp AJ, Sigurdsson V, van Diest PJ. Comparison of survival between patients with single vs multiple primary cutaneous melanomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1049–1056. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe CJ, Law MH, Palmer JM, MacGregor S, Hayward NK, Khosrotehrani K. Survival outcomes in patients with multiple primary melanomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kricker A, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, et al. Survival for patients with single and multiple primary melanomas: the genes, environment, and melanoma study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:921–927. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman D, Farnham JM, Hyngstrom J, et al. Similar survival of patients with multiple versus single primary melanomas based on Utah Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data (1973–2011). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karapetyan L, Kirkwood JM. State of melanoma: an historic overview of a field in transition. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021;35:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2020.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twine NC, Stover JA, Marshall B, et al. Disease-associated expression profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6069–6075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang DH, Rutledge JR, Patel AA, Heerdt BG, Augenlicht LH, Korst RJ. The effect of lung cancer on cytokine expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baine MJ, Chakraborty S, Smith LM, et al. Transcriptional profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in pancreatic cancer patients identifies novel genes with potential diagnostic utility. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotson D, Alvarado R, Conroy A, et al. Systems biology analysis of immune signaling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab; basis for clinical response biomarker identification. J Immunother Cancer. 2013;1:P257. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-1-S1-P257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helgadottir H, Isaksson K, Fritz I, et al. Multiple primary melanoma incidence trends over five decades: a nationwide population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:318–328. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welch HG, Mazer BL, Adamson AS. The rapid rise in cutaneous melanoma diagnoses. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:72–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJM.sb2019760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saleh FH, Crotty KA, Hersey P, Menzies SW. Primary melanoma tumour regression associated with an immune response to the tumour-associated antigen melan-A/MART-1. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:551–557. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Youlden DR, Baade PD, Soyer HP, et al. Ten-y ear survival after multiple invasive melanomas is worse than after a single melanoma: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2270–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardo LM, van der Leest RJ, de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, Nijsten T, Hollestein LM. Comparing survival of patients with single or multiple primary melanoma in the Netherlands: 1994–2009. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:531–533. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menzies S, Barry R, Ormond P. Multiple primary melanoma: a single centre retrospective review. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:638–640. doi: 10.1097/cmr.0000000000000395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Damme JO, Wuyts A, Froyen G, et al. Granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 and related CXC chemokines: from gene regulation to receptor usage. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:563–569. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.5.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ZhM, BagstafM, WolJ. Production and upregulation of granulocyte chemotactic protein-2/CXCL6 by IL-1β and hypoxia in small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1936–1941. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verbeke H, Struyf S, Berghmans N, et al. Isotypic neutralizing antibodies against mouse GCP-2 /CXCL6 inhibit melanoma growth and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2011;302:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Coillie E, Van Aelst I, Wuyts A, et al. Tumor angiogenesis induced by granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 as a countercurrent principle. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1405–1414. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62527-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin L, Spoor MS, Gerth AJ, Brody SL, Peng SL. Modulation of Th1 activation and inflammation by the NF-κB repressor Foxj1. Science. 2004;303:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.1093889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L, Brody SL, Peng SL. Restraint of B cell activation by Foxj1-mediated antagonism of NF-κB and IL-6. J Immunol. 2005;175:951–958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lan Y, Hu X, Jiang K, Yuan W, Zheng F, Chen H. Significance of the detection of TIM-3 and FOXJ1 in prostate cancer. J Buon. 2017;22:1017–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xian S, Shang D, Kong G, Tian Y. FOXJ1 promotes bladder cancer cell growth and regulates Warburg effect. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu P, Piao Y, Dong X, Jin Z. Forkhead box J1 expression is upregulated and correlated with prognosis in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:1487–1494. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.