Abstract

Information flow in neurons proceeds by integrating inputs in dendrites, generating action potentials near the soma and releasing neurotransmitters from nerve terminals in the axon. We found that in the striatum, acetylcholine-releasing neurons induce action potential firing in distal dopamine axons. Spontaneous activity of cholinergic neurons produced dopamine release that extended beyond acetylcholine signaling domains, and traveling action potentials were readily recorded from dopamine axons in response to cholinergic activation. In freely moving mice, dopamine and acetylcholine covaried with movement direction. Local inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors impaired dopamine dynamics and affected movement. Our findings uncover an endogenous mechanism for action potential initiation independent of somatodendritic integration, and establish that this mechanism segregates the control of dopamine signaling between axons and somata.

One-Sentence Summary

Activity of cholinergic neurons triggers action potential firing in distal dopamine axons to regulate striatal function.

Neurons receive input through dendrites and send output through axons. While axonal function is regulated locally, it is thought that distal axons are not equipped with endogenous, physiological mechanisms for action potential induction. Midbrain dopamine neurons innervate the striatum with extensively arborized axons to regulate a wide variety of functions (1–4). One to three percent of striatal neurons are tonically active interneurons that release acetylcholine (ACh), and their axons intertwine with those of dopamine neurons (5, 6). Dopamine axons express high levels of nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs), and synchronous activation of these receptors can drive dopamine release directly (6–12). Hence, distal dopamine axons are under local striatal control and can release dopamine independent of activity ascending from their midbrain somata. However, because the command for neurotransmitter release generally originates from the soma, fundamental questions remain as to how nAChR activation is translated into dopamine release and whether this process represents a bona fide regulation employed by the dopamine system.

The striatal cholinergic system broadcasts dopamine release

We expressed GRABDA2m (abbreviated as GRABDA,a D2 receptor-based dopamine sensor (13)) in midbrain dopamine neurons and monitored fluorescence changes in acute striatal slices (Fig. 1A). Restricting GRABDA expression to dopamine axons provides a widespread sensor network in the striatum and facilitates detection as the sensors are present in the immediate vicinity of dopamine release (Fig. 1B). Dopamine release was detected in both dorsal and ventral striatum without any stimulation, and this spontaneous release was sensitive to DHβE, a blocker of β2-containing nAChRs (Fig. 1, A to E, and fig. S1A, and Movie S1). Release occurred stochastically and exhibited all-or-none properties: either an event covered a large area, estimated to contain 3–15 million dopamine terminals (14), or no release was detected (Fig. 1C, and fig. S1C). Because midbrain dopamine cell bodies are absent in this striatal slice preparation, the detected release is induced without involvement of dopamine neuron somata.

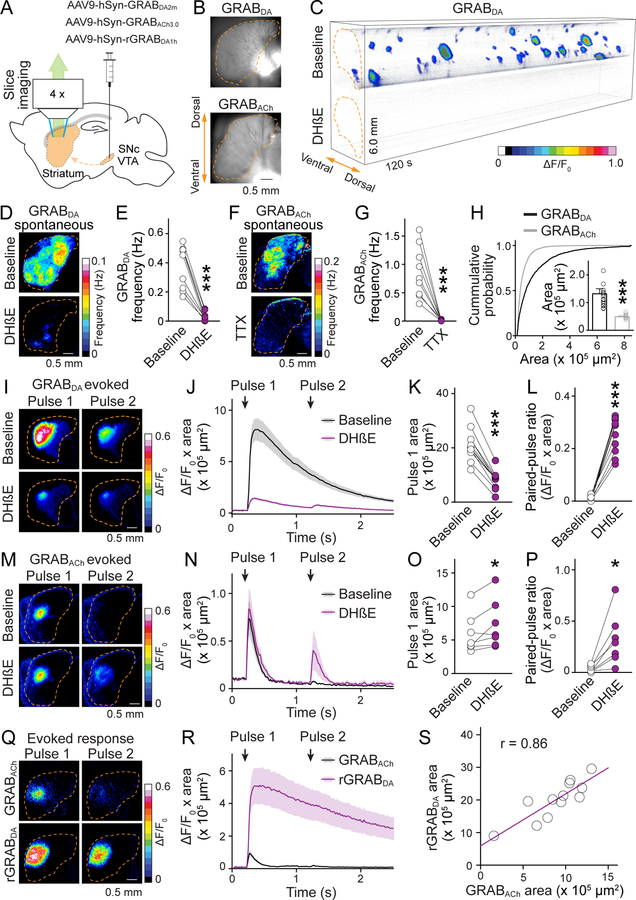

Fig. 1. ACh-induced dopamine secretion expands beyond ACh release.

(A) Schematic of midbrain AAV injection for dopamine axonal expression of GRABDA, rGRABDA or GRABACh sensors followed by widefield fluorescence imaging in parasagittal striatal slices. (B) GRABDA and GRABACh expression in striatal slices. Dashed lines (orange) outline the striatum. (C) Volume-rendered time series of spontaneous GRABDA fluctuations (expressed as ΔF/F0, color-coded for magnitude) before (top) and after (bottom) application of DHβE (1 μM). Areas with ΔF/F0 < 0.02 were made transparent for clarity. (D, E) Example frequency maps (D) and quantification (E) of spontaneous GRABDA events detected before and after 1 μM DHβE; n = 9 slices/4 mice. (F, G) As (D, E), but for GRABACh before and after 1 μM TTX; n = 9/3. (H) Comparison of the area covered by GRABDA and GRABACh events; n = 1010 events/17 slices/4 mice for GRABDA, 2087/14/4 for GRABACh. (I to L) Example images (I) and quantification (J to L) of GRABDA fluorescence evoked by paired electrical stimuli (1-s interval) before and after 1 μM DhβE; n = 11/4. (M to P) As I to L, but for GRABACh; n = 7/3. (Q, R) As (I, J), but for simultaneous assessment of GRABACh and rGRABDA; n = 12/4. (S) Correlation of areas in (R). Data are mean ± SEM; * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001; Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for (E), (G), (K), (L), (O), and (P); Mann-Whitney rank-sum test for (H).

Using a corresponding strategy with GRABACh3.0 (abbreviated as GRABACh, an M3-receptor-based ACh sensor (15)), we also detected spontaneous ACh release in both dorsal and ventral striatum, consistent with previous work on spontaneous ACh neuron activity (16). ACh release was sensitive to the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX), and exhibited an all-or-none pattern like dopamine (Fig. 1, F and G, fig. S1, A to C, and movie S2). The frequency of ACh release was ~three-fold higher than that of dopamine release, suggesting that not all ACh triggers dopamine release (Fig. 1, E and G). Although less frequent, areas covered by dopamine release were ~three times larger compared to those of ACh (Fig. 1H). Adjusting event detection thresholds or enhancing GRABACh expression by injecting the respective AAV directly into the striatum slightly influenced the signals (fig. S1, D to G), but dopamine release continued to be less frequent and broader than ACh release. Increasing slice thickness enhanced dopamine release frequency, but blocking synaptic transmission only marginally influenced dopamine and ACh release (fig. S2).

Cholinergic interneurons exhibit multiple firing activities: they have spontaneous pacemaker activity and they respond with pause-rebound firing in vivo to a variety of sensory stimuli (17–20). Because spontaneous cholinergic activity drives dopamine release stochastically (Fig. 1, C and D), we speculated that pause-rebound firing might induce time-locked dopamine release. We mimicked ACh pause-rebound activity in striatal slices and found that it induces a robust dopamine transient during rebound firing (fig. S3).

We next evoked dopamine and ACh release using electrical stimulation. A large proportion of electrically evoked dopamine release was driven by activation of nAChRs (Fig. 1, I and J) (6, 10, 12, 14). Consistent with the findings from spontaneous release, evoked dopamine release covered an area three to four times larger than evoked ACh release, and nAChR blockade strongly reduced its area (Fig. 1, K and O). Similar results were obtained when ACh and dopamine release were measured simultaneously (with GRABACh and rGRABDA1h, abbreviated as rGRABDA, a red-shifted dopamine sensor (13)), and the release areas were positively correlated with one another (Fig. 1, Q to S).

Dopamine release with nAChR activation depressed more strongly during repetitive stimulation than release evoked without it (Fig. 1 I to L) (12, 14). This is thought to be a result of rapid nAChR-desensitization, but our data indicate that it is most likely caused by depression of ACh release after the first stimulus (Fig. 1, M to P). The depression of ACh release was attenuated by blocking nAChRs or D2 receptors, but not AMPA, NMDA, or GABAA receptors (Fig. 1, P and fig. S4), suggesting that it is due to feedback inhibition mediated by dopamine. Blocking nAChRs or D2 receptors also increased ACh release in response to the first stimulus (Fig. 1, M to O, and fig. S4, E to G), likely because ACh release is tonically inhibited by dopamine (18).

Acetylcholine- and action potential-induced dopamine secretion share release mechanisms

We next asked why dopamine release spreads beyond the area of ACh release (Fig. 1, Q to S). We first examined the organization of striatal ACh terminals and dopamine axons using 3D-SIM superresolution microscopy. Although synaptophysin-tdTomato labeled ACh terminals were intermingled with TH-labeled dopamine axons, no prominent association was detected (8, 21) and their contact frequency was much lower than the density of release sites in dopamine axons (Fig. 2, A and B) (14).

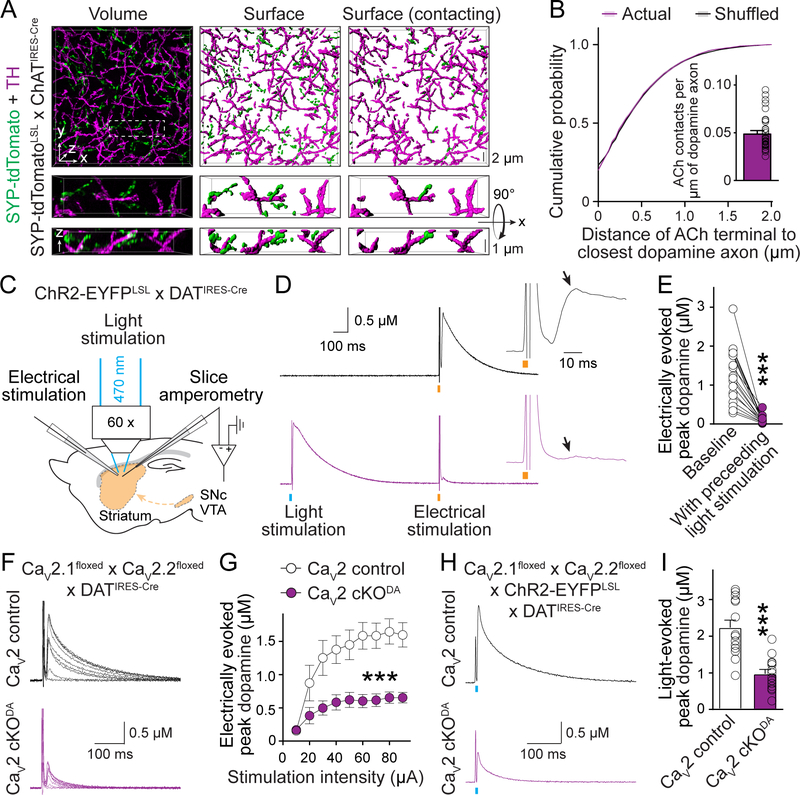

Fig. 2. ACh triggers dopamine secretion through the same release mechanisms as dopamine neuron action potentials.

(A) Example 3D-SIM images of dorsal striatal slices showing dopamine axons (labeled with TH antibodies) and ACh nerve terminals (labeled by crossing Cre-dependent Synpatophysin-tdTomato mice, SYP-tdTomatoLSL, with ChATIRES-Cre mice). Images were obtained by volume rendering of an image stack (left), surface rendering of detected objects (middle), and surface rendering of ACh terminals that contact dopamine axons (right, > 0 voxel overlap). (B) Comparison of the minimal distance of ACh terminals from the nearest dopamine axons. Controls were generated by averaging 1000 rounds of local shuffling and distance calculation of each ACh terminal within 5 × 5 × 1 μm3; n = 5482 objects/33 images/4 mice. (C) Schematic of slice recordings. ChR2-EYFP was expressed in dopamine neurons (by crossing ChR2-EYFPLSL with DATIRES-Cre mice), and dopamine release was measured using amperometry in dorsal striatal slices in the area of light stimulation. (D, E) Example traces (D) and quantification (E) of peak amplitude of the second dopamine release phase (arrows) evoked by electrical stimulation (orange bar) with (bottom) or without (top) a preceding 1-ms light stimulus (blue bar, 1 s before); n = 18 slices/3 mice. (F, G) Example traces (F) and quantification of peak dopamine amplitude (G, second phase) evoked by electrical stimulation in CaV2 cKODA mice (CaV2.1 + 2.2 double floxed mice crossed to DATIRES-Cre mice) and sibling CaV2 control mice; n = 1¾ each (p < 0.001 for genotype, stimulation intensity and interaction; two-way ANOVA; genotype effect reported in the figure). (H, I) Similar to (F, G), but with dopamine release evoked by light stimulation in mice expressing ChR2-EYFP transgenically in dopamine neurons; n = 14/5 each. Data are mean ± SEM; *** p < 0.001; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for (B); Wilcoxon signed-rank test for (E); Mann-Whitney rank-sum test for (I).

Dopamine axons contain varicosities that are filled with vesicles, but only a small fraction of the vesicles are releasable, and only a subset of the varicosities contains active release sites to respond to action potentials (3, 14, 22). Thus, one way for ACh neurons to boost dopamine release could be by recruiting additional vesicles and/or release sites. To test this possibility, we performed cross-depletion experiments. We expressed the light-activated cation channel channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in dopamine axons and evoked dopamine release with light (to specifically activate dopamine axons) followed by electrical stimulation (to activate dopamine axons and ACh neurons, Fig. 2C). Electrical stimulation induces dopamine release with two phases (fig. S5), and the second phase is entirely mediated by ACh (12, 14). Preceding light stimulation nearly abolished the second phase (Fig. 2, D and E), indicating that vesicles and release sites are shared between the two release modes.

In principle, ACh may trigger dopamine release in three ways. First, because nAChRs (including the α6- and α4-containing nAChRs on dopamine axons (8)) are non-selective cation channels (23), Ca2+ entry through them might directly trigger dopamine vesicle fusion. Second, nAChR activation might depolarize the dopamine axon membrane and activate low voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to induce dopamine release. Last, nAChR activation on dopamine axons might initiate ectopic action potentials followed by opening of low and high voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and release.

We started distinguishing between these possibilities by characterizing the Ca2+ sources for ACh-induced dopamine release. Double knockout of CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) and CaV2.2 (N-type) channels in dopamine neurons similarly reduced ACh-induced release (the second phase in response to electrical stimulation) and action potential-induced release (by optogenetic activation of dopamine axons, Fig. 2, F to I, and fig. S5A). Removing CaV2.3 (R-type) channels had no effect (fig. S5, B to D). Hence, both release modes rely on these voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to a similar extent, ruling out that nAChRs are the main source of Ca2+ influx. Because CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 are high voltage-activated and open efficiently at membrane potentials higher than typical action potential thresholds (24, 25), generating ectopic action potentials in dopamine axons is most likely necessary for ACh to induce dopamine release.

Striatal cholinergic activation induces action potential firing in distal dopamine axons

To test whether ACh can induce dopamine axon firing, we expressed ChR2 in dopamine or ACh neurons and recorded evoked dopamine release and field potentials in striatal slices using a carbon fiber electrode (Fig. 3A, and fig. S6, A and B). Optogenetic activation of dopamine axons evoked robust dopamine release and a triphasic field potential that was abolished by TTX, but insensitive to a range of neurotransmitter receptor blockers (Fig. 3B, and fig. S7A). This indicates that the field potential represents dopamine axon population firing. Optogenetic activation of the cholinergic system produced a similar triphasic response that was disrupted by DHβE or by 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-lesion of dopamine axons (Fig. 3C, and fig. S6C), demonstrating that it is evoked by nAChR activation and originates from dopamine axons.

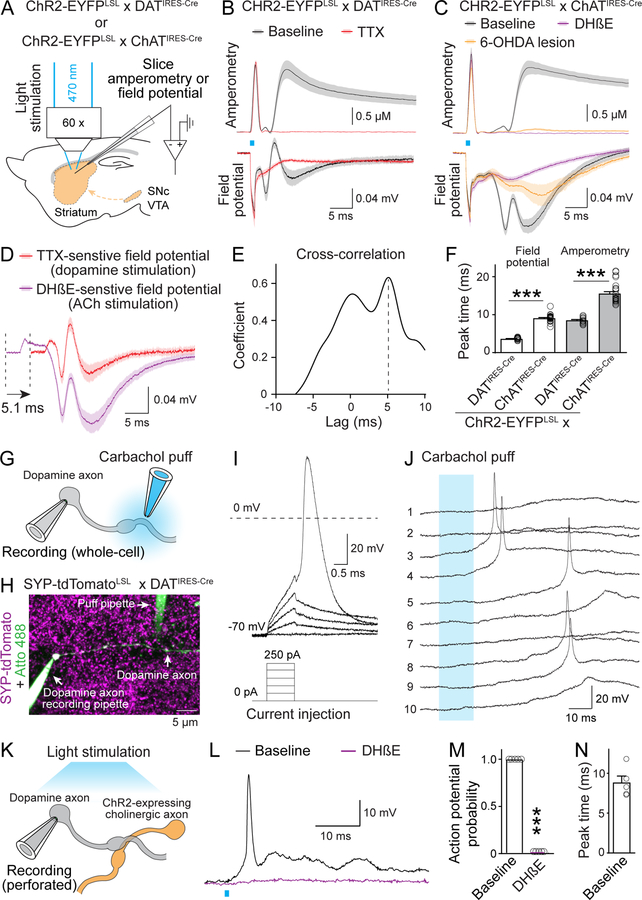

Fig. 3. Activation of nAChR triggers action potentials in striatal dopamine axons.

(A) Schematic of recordings with carbon fiber electrodes in voltage-clamp (0.6 V, amperometric recordings) or current-clamp (no current injection, field potential recordings). (B, C) Average traces of light-evoked dopamine release (top, amperometry) and field potentials (bottom) in brain slices of mice with CHR2-EYFP in dopamine axons (B) or ACh neurons (C). Example traces are in fig. S7, B and C. Recordings were in ACSF (baseline), in 1 μM TTX (B), in 1 μM DHβE (C) or after 6-OHDA injection (C); B, n = 12 slices/3 mice each; C, 25/6 (each) for baseline, 21/6 (amperometry) and 9/4 (field potentials) for DHβE, and 11/6 each for 6-OHDA. (D) Comparison of TTX-sensitive and DHβE-sensitive field potentials (obtained by subtraction; fig. S7, B and C). TTX-sensitive components are right-shifted by 5.1 ms (lag detected in E); n as in (B) and (C). (E) Cross-correlation of TTX- and DHβE-sensitive components shown in (D). (F) Lag of peak response from the start of the light stimulus; n as in (B) and (C). (G, H) Schematic (G) and example two-photon image (H) of direct recording from dopamine axons. Synaptophysin-tdTomato was expressed using mouse genetics in dopamine axons, the recorded axon was filled with Atto 488 (green) through the recording pipette, and the puff pipette contained carbachol and Atto 488. (I, J) Example responses of a dopamine axon to current injections through the whole-cell pipette (I) or to 10 consecutive carbachol puffs (100 μM, numbered, 10-s intervals, J). (K) Schematic of dopamine axon perforated patch recording in mice expressing ChR2-EYFP in ACh neurons. (L to N) Example traces (L), probability of action potential firing (M) and lag of action potential peak times to light onset (N) in dopamine axon recordings with optogenetic ACh interneuron activation before and after 1 μM DHβE; n = 5 axons/3 mice. Data are mean ± SEM; *** p < 0.001; Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance with post hoc Dunn’s test for (F); Mann-Whitney rank-sum test for (M).

The shape of the DHβE-sensitive component of cholinergic activation was similar to the TTX-sensitive component of dopamine axon stimulation (Fig. 3, D and E, and fig. S7, B and C), suggesting that ACh induces firing in dopamine axons. The potential induced via cholinergic activation lagged 5.1 ms behind that of dopamine axon stimulation, consistent with the timing of ACh-induced dopamine release (Fig. 3, D to F) (12, 14). Similar to evoked ACh release (fig. S4, E to H), the field potential induced by cholinergic activation exhibited a strong depression during repetitive stimulation that was partially relieved by blocking D2 receptors (fig. S7, D and E).

To investigate the firing of individual axons, we performed direct recordings (26) from genetically labeled dopamine axons (Fig. 3, G and H). Current injection reliably induced large and brief action potentials (Fig. 3I, amplitude: 113 ± 2 mV, half-width: 0.64 ± 0.03 ms, n = 24 axons/9 mice). Upon puffing of carbachol (an nAChR agonist) onto the axon 20–40 μm away from the recording site, 3 out of 14 axons exhibited action potential firing (Fig. 3J, and fig. S7F). To test whether action potentials can be induced by endogenous ACh release, we expressed ChR2 in cholinergic interneurons and performed perforated patch recordings from dopamine axons (Fig. 3K). Optogenetic activation of ACh neurons could be tuned to evoke action potentials in all five recorded dopamine axons, and nAChR blockade abolished firing (Fig. 3, L and M). Action potential peak times matched precisely with those of the potentials measured in the field recordings (Fig. 3, F and N).

Striatal acetylcholine and dopamine covary with movement direction

To investigate the functional significance of ACh-induced dopamine release, we expressed GRABDA or GRABACh together with tdTomato in the right dorsal striatum and monitored the dynamics of the corresponding transmitters using dual-color fiber photometry in mice exploring an open field arena (Fig. 4A, and fig. S8). Because striatal dopamine and ACh might play important roles in movement initiation (27–31), we aligned GRABDA or GRABACh signals to movement onset. We found that both exhibited an increase on average, but there was strong heterogeneity in individual responses (fig. S9).

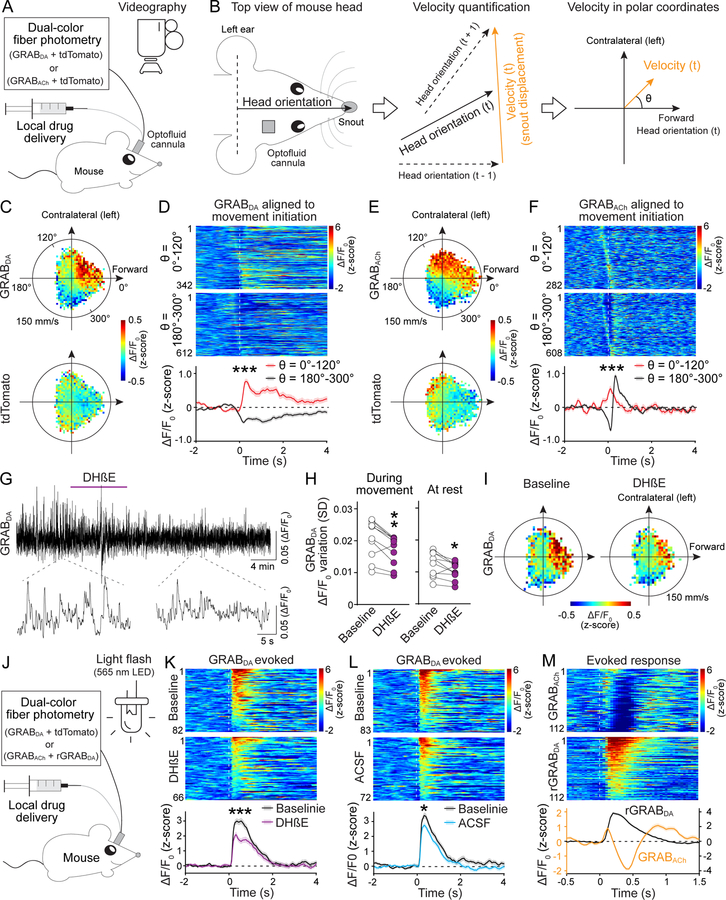

Fig. 4. Dopamine and ACh dynamics correlate with movement direction, and dopamine dynamics are attenuated after blocking nAChRs.

(A) Strategy for simultaneous measurements of dopamine or ACh dynamics and behavior in freely moving mice. (B) Fiber photometry and drug delivery were in the right dorsal striatum using an optofluid cannula. Head orientation was defined as the direction from the center point between the ears to the snout. Instantaneous velocity at time point t was calculated from the displacement of the snout from t − 1 to t + 1 and plotted in polar coordinates with head orientation at t defined as θ = 0°. (C) Average GRABDA and tdTomato signals registered to their concurrent velocities in polar coordinates; n = 10 mice. (D) Individual (heatmap) and average GRABDA fluctuations aligned to movement initiation (dashed line) with θ = 0°–120° (top) or 180°–300° (bottom). Heatmaps were sorted by peak time; n = 342 events/10 mice for θ = 0°–120°, 612/10 for θ = 180°–300°. (E, F) As (C, D), but for GRABACh; n = 282/11 for θ = 0°–120°, 608/11 for θ = 180°–300°. (G, H) Example trace (G) and quantification (H, standard deviation of ΔF/F0) of GRABDA fluorescence before and after DHβE (50 μM, 1 μl) delivered via the optofluid canula; n = 10 mice. (I) Average GRABDA signals registered to concurrent velocities before and after DHβE; n = 10. (J) Schematic for measurements of dopamine release induced by 200-ms light flashes in freely moving mice. (K, L) Individual (heatmap) and average GRABDA fluctuations aligned to the light flash (dashed line) before and after local infusion of DhβE (K) or ACSF (L); K, n = 82 responses/10 mice for baseline, 66/10 for DhβE; L, 83/10 for baseline, 72/10 for ACSF. (M) Similar to K but for simultaneous assessment of GRABACh and rGRABDA; n = 112/4. Data are mean ± SEM; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05; Mann-Whitney rank-sum tests for areas under the curve (0–400 ms) in (D), (F), (K) and (L). Wilcoxon signed-rank test for (H).

In previous studies, movement was often restricted to specific directions and/or treated as a scalar quantity (27–31). In our experiments, mice traveled freely in a large arena and constantly adjusted body posture and movement direction. If only the amplitude of velocity (speed) is considered, spatial information is lost. Hence, we treated velocity as a two-dimensional vector relative to the mouse’s head orientation and registered photometry signals to the corresponding velocity plotted in polar coordinates (with angle θ defined as the direction of velocity; Fig. 4B, and fig. S10, A and D). Striatal dopamine and ACh levels were highly correlated with movement direction (Fig. 4, C and E): both exhibited an increase when the animal was turning to the contralateral side or moving forward (θ = 0°–120°), and a decrease when the animal was turning to the ipsilateral side or backward (θ = 180°–300°). This pattern became more evident when the time series of velocity was right-shifted (fig. S10, B and E), indicating that the velocity peak precedes that of the photometry signal.

When aligned to movement initiations with selected directions, dopamine responses diverged. There was an increase at θ = 0°–120° and a decrease at θ = 180°–300°, and dopamine transients peaked ~150 ms after movement onset (Fig. 4C and D, and fig. S10, A to C). ACh levels also diverged when aligned to movement onset with selected directions. However, instead of a monotonic decrease, ACh exhibited a decrease followed immediately by an increase for movement initiations with θ = 180°–300° (Fig. 4, E and F). This was also detected in the polar coordinates when the velocity time course was right-shifted (fig. S10, D to F).

Striatal acetylcholine contributes to dopamine dynamics

Local inhibition of nAChRs by infusion of DHβE through the optofluid canula slightly decreased dopamine fluctuations (Fig. 4, G and H, and fig. S11, A and B). Dopamine cell bodies and the striatal cholinergic system both drive firing in dopamine axons. The effect of nAChR blockade may be limited because firing of dopamine cell bodies might dominate the signal, and somatic firing could also compensate for the loss of dopamine release induced by blocking nAChRs.

The correlation between dopamine fluctuations and movement direction was largely preserved after unilateral nAChR block with DHβE (Fig. 4I and fig. S11C). However, unilateral DhβE infusion caused a robust reduction in both amplitude and frequency of movement initiations with θ = 0°–120°, but only a slight change in amplitude and no change in frequency of those with θ = 180°–300° (fig. S11, D to G).

Dopamine neurons respond to salient sensory stimuli (4). We evoked dopamine release by applying 200-ms flashes of light to the open field arena at random intervals (Fig. 4J). Local infusion of DhβE reduced the evoked GRABDA response (Fig. 4, K and L, fig. S11H). ACSF infusion also caused a reduction, likely due to habituation of the mice to the repeated stimuli, that was smaller than the one induced by nAChR blockade (Fig. 4L and fig. S11H). When dopamine and ACh were monitored simultaneously with rGRABDA and GRABACh, respectively, light stimulation evoked a triphasic ACh response with the initial rise in ACh preceding that of dopamine (Fig. 4M and fig. S11I).

Discussion

Neurotransmitter release from nerve terminals is generally determined by action potentials initiated at the axon initial segment near the soma. Ectopic action potentials are less common, and their functional roles remain elusive (32, 33). Here, we show that ACh induces firing in distal dopamine axons as a physiological mechanism to regulate dopamine signaling. This explains how the striatal cholinergic system broadcasts dopamine release. Ectopic action potentials likely propagate through the axonal network and trigger release along the path. This firing mechanism also accounts for the all-or-none pattern of spontaneous dopamine release and answers why coincident activity in multiple cholinergic neurons is necessary (6): ACh has to quickly depolarize dopamine axons to trigger action potentials before the opening of potassium channels and before ACh is degraded by acetylcholinesterase.

Axonal transmitter secretion is generally viewed to rely on the interplay between firing from the soma (which recruits the entire axon) and local regulation in single nerve terminals (which locally tunes release). We find that local ACh release not only triggers dopamine release (6, 9–12), but hijacks the dopamine axon network to expand signaling with high temporal precision. The exceptionally high levels of nAChRs on dopamine axons (7, 8) might serve to initiate axonal firing. Because presynaptic nAChRs enhance release in multiple types of neurons (34), this axonal firing mechanism might be important beyond the dopamine system.

As individual dopamine terminals are indifferent as to where an action potential is generated, an immediate question is the functional significance of initiating action potentials in two distinct brain areas. We propose that ACh-induced dopamine axon firing not only represents a distinct input, but also sculpts a different dopamine signaling architecture compared to somatic firing. Both phasic somatic and axonal firing induction recruit groups of dopamine axons. Striatal ACh triggers action potentials in neighboring axons centered around the site of ACh release. Phasic firing in the midbrain, in contrast, recruits cell bodies that share excitatory input, and their axons may or may not be intermingled in the striatum (1, 35, 36). Hence, ACh-induced dopamine release might endow dopamine signaling with spatial control over striatal circuitry that is distinct from release induced by activating midbrain somata. Our work further suggests that information flow in dopamine neurons between the midbrain and striatum might be bidirectional. Axon→soma signaling could occur through action potential backpropagation (37, 38) upon striatal cholinergic activity to regulate somatodendritic dopamine release, dendritic excitability, or other midbrain processes.

Roles for striatal dopamine and ACh are under intense investigation, and both excitation and inhibition in the firing have been associated with spontaneous movement (27, 28, 30, 31). We demonstrate that striatal dopamine and ACh not only correlate with movement initiation but also with its direction, potentially explaining the heterogeneity of their responses at movement onset. The findings that ACh and dopamine covary with movement direction and that ACh enhances dopamine dynamics suggest that the two systems are coordinated for their roles in motor control (27). They fit well with classical observations that unilateral lesions of dopamine or ACh systems induce asymmetric behavior and support that dynamic transmitter balance between hemispheres is important for adjusting body posture (29, 39). Finally, we observe that dopamine dynamics are regulated by nAChRs regardless of movement state, indicating that ACh-induced dopamine release likely has additional physiological roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Qiao, M. Han, and J. Wang for technical assistance; Drs. N. Uchida, M. Watabe-Uchida, and I. Tsutsui-Kimura for advice on setting up fiber photometry; Drs. A. van den Maagdenberg for CaV2.1floxed mice and T. Schneider for CaV2.3floxed mice; and Drs. C. Harvey, B. Sabatini, W. Regehr, N. Uchida, J. Williams and R. Wise for discussions and comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge the Neurobiology Imaging Facility (supported by P30NS072030) and Cell Biology Microscopy Facility for microscope availability and advice.

Funding:

This work was supported by the NIH (R01NS103484 and R01NS083898 to PSK, NINDS Intramural Research Program Grant NS003135 to ZMK), the European Research Council (ERC CoG 865634 to SH), the German Research Foundation (DFG; HA6386/10-1 to SH), the Dean’s Initiative Award for Innovation (to PSK), a Harvard-MIT Joint Research Grant (to PSK), and a Gordon family fellowship (to CL). XC is a visiting graduate student and received a PhD Mobility National Grants fellowship from Xi’an Jiaotong University/China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

Data and material availability:

References and Notes

- 1.Matsuda W et al. , J. Neurosci. 29, 444–53 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berke JD, What does dopamine mean? Nat. Neurosci. 21 (2018), pp. 787–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu C, Goel P, Kaeser PS, Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 345–358 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O, Neuron. 68, 815–34 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson CJ, Neuron. 45, 575–585 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Threlfell S et al. , Neuron. 75, 58–64 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Novère N, Zoli M, Changeux JP, Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 2428–39 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones IW, Bolam JP, Wonnacott S, J. Comp. Neurol. 439, 235–47 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorguieff MF, Le Floc’h ML, Glowinski J, Besson MJ, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 200, 535–44 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou F-M, Liang Y, Dani JA, Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1224–1229 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cachope R et al. , Cell Rep. 2, 33–41 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L et al. , J. Physiol. 592, 3559–3576 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun F et al. , Nat. Methods. 17, 1156–1166 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Kershberg L, Wang J, Schneeberger S, Kaeser PS, Cell. 172, 706–718.e15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jing M et al. , Nat. Methods. 17, 1139–1146 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamaligas AA, Ford CP, Neuron. 91, 574–586 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz JM, Oswald MJ, Reynolds JNJ, J. Neurosci. 31, 11133–43 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris G, Arkadir D, Nevet A, Vaadia E, Bergman H, Neuron. 43, 133–43 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai Y, Ford CP, Cell Rep. 25, 3148–3157.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub C, Tritsch NX, Hagan NA, Gu C, Sabatini BL, J. Neurosci. 34, 8557–69 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang HT, Brain Res. Bull. 21, 295–304 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira DB et al. , Nat. Neurosci. 19, 578–586 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Decker ER, Dani JA, J. Neurosci. 10, 3413–20 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Held RG et al. , Neuron. 107, 667–683.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J et al. , Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 317 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritzau-Jost A et al. , Cell Rep. 34, 108612 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howe M et al. , Elife. 8 (2019), doi: 10.7554/eLife.44903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodson PD et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, E2180–E2188 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaneko S et al. , Science. 289, 633–637 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howe MW, Dombeck DA, Nature. 535, 505–510 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva JA, Tecuapetla F, Paixao V, Costa RM, Nature. 554, 244–248 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugladze T, Schmitz D, Whittington MA, Vida I, Gloveli T, Science. 336, 1458–1461 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheffield MEJ, Best TK, Mensh BD, Kath WL, Spruston N, Nat. Neurosci. 14, 200–207 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dani JA, Bertrand D, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 699–729 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eshel N, Tian J, Bukwich M, Uchida N, Nat. Neurosci. 19, 479–486 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker JG et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 13491–13496 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grace AA, Bunney BS, Science. 210, 654–6 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gentet LJ, Williams SR, J. Neurosci. 27, 1892–901 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker NF et al. , Nat. Neurosci. 19, 845–854 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6342359 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6342367 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.