Abstract

Study design

Prospective observational study

Objective

The population of patients with advanced stages of cancer, including metastatic spinal disease, is growing because of better treatment options allowing for longer control of disease. The main goal of treatment for these patients is to improve or maintain their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). A spine oncology-specific outcome measure has been developed by the Spine Oncology Study Group and validated through international studies. We proposed to translate and validate the questionnaire in Italian language.

Methods

The cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire has been performed according to guidelines previously proposed. After this process, an observational prospective study has been conducted to validate the efficacy of SOSGOQ in Italian language. SOSGOQ has been compared to SF-36 (Short Form Health Survey-36), a generic validated questionnaire to assess HRQOL. Starting from January 2020, SOSGOQ and SF-36 questionnaires were auto-administered to 150 patients affected by spinal metastases who provided written informed consent for study participation.

Results

The confirmatory factor analysis on the 4 domains examined showed a good model fit (comparative fit index, .95; RMSEA .07 (90% CI, .05-.09) and SRMR, .05), endorsing construct validity. The analysis of concurrent validity demonstrated strong correlation for physical function, pain and mental health domains with the corresponding domain scores of SF-36. The reliability across item was high with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .91.

Conclusions

The statistical analysis of the results will allow to accept the Italian version of SOSGOQ as a specific and efficient tool to measure HRQOL in Italian-speaking patients affected by spinal metastases.

Keywords: Spinal Oncology Study Group Outcome Questionnaire, spinal metastases, quality of life, patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

The population of patients with advanced stages of cancer and a diagnosis of bone metastases is growing due to the better treatment options allowing for longer control of disease. 1 One of the goals of the treatment of these patients is to improve or maintain their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and for this reason it is important to have efficient tools for the patient’s self-assessment (Patient Reported Outcomes, PROMs) of HRQOL in order to optimize the care.

Validated generic questionnaires are used to assess HRQOL in patients’ populations, such as EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D) and SF-36, while several cancer-specific questionnaires have been developed and approved by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. 2 Moreover, a disease-specific instrument in addition to a generic (cancer) HRQOL measure would increase the sensitivity and specificity of HRQOL assessments. The Spinal Oncology Study Group Outcome Questionnaire (SOSGOQ) was developed as the first specific questionnaire for oncological pathology of the spine, in particular for patients with vertebral metastases. The questionnaire was developed through consensus discussion of the SOSG (Spine Oncology Study Group), followed by a systematic evaluation to examine if all quality of life domains were adequately represented. 3

The SOSGOQ was then validated through international studies in its first version 4 and in its revised version (SOSOQ 2.0), 5 which is currently used.

The first version of SOSGOQ was composed by 27 questions with 5 answer options, divided into 6 domains: physical function with 4 items, neurological function with 4 items, pain with 4 items, mental health with 4 items, social function with 4 items, and post-therapy questions with 7 items (Table 1), while the revised version (SOSGOQ 2.0) consists of 5 HRQOL domains (physical function, neurological function, pain, mental health, and social function) and an additional set of post-treatment questions for follow-up evaluation.

Table 1.

Domains and Items of the Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire (SOSGOQ), Adapted from Janssen et al. 4 .

| Domains | Items |

|---|---|

| Domain I: Physical function | 1. What is your current level of activity? |

| 2. What is your ability to work (including at home)/study? | |

| 3. Does your spine limit your ability to care for yourself? | |

| 4. Do you require assistance from others to travel outside of the home? | |

| Domain II: Neurological function | 5. Do you have weakness in your legs? |

| 6. Do you have weakness in your arms? | |

| 7. What assistance do you need with your walking? | |

| 8. Do you have difficulty controlling your bowel and bladder function beyond episodes of diarrhea or constipation? | |

| Domain III: Pain | 9. Overall, on average, how much back or neck pain have you had in the past 4 weeks? – |

| 10. When you are in your most comfortable position, do you still experience back or neck pain (limiting your sleep)? | |

| 11. How much has your pain limited mobility (sitting, standing, your walking)? | |

| 12. How confident do you feel about your ability to manage your pain on your own? | |

| Domain IV: Mental health | 13. Have you felt depressed over the past 4 weeks? |

| 14. Do you feel anxiety about your health related to your spine? | |

| 15. Do you have a lot of energy? | |

| 16. When I feel pain, it is awful and I feel it overwhelms me | |

| Domain V: Social function | 17. Does your spine influence your ability to concentrate on conversations, reading, and television? |

| 18. Do you feel that your spine condition impairs or compromises your personal relationships? | |

| 19. Are you comfortable meeting new people? | |

| 20. Do you leave the house for social functions? | |

| Domain VI: Post therapy questions | 21. Are you satisfied with the results of your spine tumor management? |

| 22. Would you choose the same management of your spine tumor again? | |

| 23. How has treatment of your spine changed your physical function and ability to pursue activities of daily living? | |

| 24. How has treatment of your spine affected your spinal cord or nerve function? | |

| 25. How has your treatment affected your overall pain from your spine? | |

| 26. How has treatment of your spine changed your depression and anxiety? | |

| 27. How has treatment of your spine changed your ability to function socially? |

SOSGOQ was developed in English language as most questionnaires. However, in multicenter international studies and registries it is necessary to provide questionnaires and tools for patients in the language of each country included. Also within each country, it is relevant to assess the HRQOL even in presence of significant cultural and ethnic diversity of the population due the presence of immigrant populations, especially when their exclusion could lead to a systematic bias in studies of healthcare utilization or quality of life. 6

Thus, the objective of this study was to translate and validate the SOSOGOQ 2.0 in Italian language.

Materials and Methods

Development and Validation of the Italian Version of the Questionnaire

The validation process took several steps: it started with the translation of the English version of SOSGOQ 2.0 in Italian language and it ended up with a clinical study where the Italian version of SOSGOQ 2.0 was compared to the Italian version of SF-36.

For the translation process, we relied on the guidelines elaborated by Beaton et al., 6 following 6 stages:

Stage 1. In the first step the translation of the original questionnaire was realized by 2 different Italian-native-speakers (T1 and T2 versions). One of the 2 translators should have knowledge in surgical spine oncology, whereas the other should be an outsider in the field (naïve translator).

Stage 2. After this, the 2 translators worked with a “recording observer” to synthesize the results of the translations: they discussed about T1 and T2 with the aim to create a new version, called T-12, which was a synthesis of the 2 translations obtained through the consensus of the 3 evaluators.

Stage 3. 2 new translators (both English native speakers and both without any specific competence or background in the subject) worked on the T-12 version of the questionnaire, totally blinded to the original version and to the concepts explored. They translated the questionnaire back into the original language, obtaining 2 back-translations: BT1 and BT2.

- Stage 4. At this point, an expert committee, formed by 2 physicians, 1 methodologist, 1 health professional and the 4 translators (forward and back translators), had the role to consolidate all the versions of the questionnaire and develop the prefinal version for the testing. The expert committee reviewed all the translations (T1, T2, BT1, and BT2) and reached a consensus on any discrepancy, considering to achieve equivalence between the source and the target in 4 areas:

- • Semantic equivalence: same meaning of the words in the source and in the target;

- • Idiomatic equivalence and pertinence: colloquialisms and idioms should have an equivalent expression in the target version;

- • Perception equivalence: the items of the questionnaire should refer to experiences of daily life in the target culture;

- • Conceptual equivalence: the translation has to taking into account how a single word could have different linguistic and meaning nuances.

Stage 5. The prefinal questionnaire obtained in stage 4 was then tested in a group of 30 persons: each subject completed the questionnaire, and was interviewed to probe about what he or she thought was meant by each questionnaire item and the chosen response. This stage provides some useful insights about the comprehension of the questionnaire’s items, but not about validity and reliability.

Stage 6. The last stage requires the submission of all the reports and forms to the developer or to a special committee whose role is to evaluate the correctness of the procedure followed. In our case, the procedure was evaluated and approved by AO Spine Foundation.

Clinical Study

After the approval of the adaptation procedure, we designed a prospective observational clinical study to assess the final Italian version of SOSGOQ 2.0 (Figure 1), which was approved by the Comitato Etico di Area Vasta Emilia Romagna on March 2020 (protocol ID: 140/2020/Oss/IOR).

Figure 1.

Italian translation of the Spinal Oncology Study Group Outcome Questionnaire 2.0.

The study population included patients affected by spinal metastatic disease, originating from solid and hematologic tumors, who were admitted in our Institute between March 2020 and March 2021: 150 patients aged 18 or over were enrolled.

At the admission, each patient received the Italian version of SOSGOQ 2.0 together with the Italian version of SF-36 by the same clinician, who provided all the indications and instructions necessary to fill the forms. The post-treatment questions were not administered to patients because these questions appeared more suitable for follow-up evaluation. Thus, the statistical analysis was performed on 20 items.

Moreover, demographic and clinical data was collected, including the primary tumor origin, the spinal metastases localization and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status evaluation to assess the general condition of the patient. This data is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and SOSGOQ 2.0 Score of Study Participants.

| Overall Sample (n = 150) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 63y (19 – 89) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 81 (54) |

| Female | 69 (46) |

| ECOG, n (%) | |

| 1 | 48 (32) |

| 2 | 45 (30) |

| 3 | 30 (20) |

| 4 | 7 (4.7) |

| Na | 20 (13.3) |

| Localization, n (%) | |

| Thoracic | 40 (26) |

| Lumbar | 34 (23) |

| Thoraco-lumbar | 24 (16) |

| Cervical | 9 (6) |

| Cervico-thoracic | 9 (6) |

| Other | 34 (23) |

| Type of metastases, n (%) | |

| Solid metastases | 104 (69) |

| Hematological metastases | 46 (31) |

| Primary tumor of solid metastases, n/N | |

| Kidney | 29/104 |

| Breast | 23/104 |

| Gastrointestinal | 18/104 |

| Lung | 10/104 |

| Thyroid | 7/104 |

| Prostate | 3/104 |

| Gynecological | 3/104 |

| Other | 11/104 |

| Physical function, mean±SD | 52.2 ± 28.7 |

| Pain, mean±SD | 47.8 ± 25.0 |

| Mental health, mean±SD | 61.1 ± 25.4 |

| Social function, mean±SD | 63.4 ± 24.8 |

| Neurological function legs, mean±SD | 61.3 ± 36.6 |

| Neurological function arms, mean±SD | 79.7 ± 28.6 |

| Neurological function bladder, mean±SD | 80.7 ± 27.3 |

| Neurological function bowel, mean±SD | 88.3 ± 23.1 |

| Total score, mean±SD | 56.1 ± 20.0 |

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with the mean and standard deviation or the median and range, and categorical variables were summarized with absolute values and percentages.

The sample size was set to a minimum of 140 subjects with 20 items in the questionnaire in order to perform a factor analysis, for which at least a subject-to-item ratio 1:7 is considered to be adequate.

All items, except for item 6, item 14, and item 20, were reversed in a positive direction where higher score denotes higher quality of life.

The construct validity of SOSGOQ2.0 was evaluated by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on the factor structure proposed by Versteeg et al. 5 The factor structure was examined by computing 3 model fit indicators: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Higher CFI values indicate better model fit, with values of .95 or more indicating good model fit and values above and near .90 indicating acceptable fit. 8 RMSEA values below .08 indicate good model fit, while values exceeding this criterion provide inadequate support for good fit. Lastly, SRMR values lower than .08 indicate good model fit. 8 Moreover, the construct (convergent/discriminant) validity of each item with the own domain or with other domains was analyzed by multitrait analysis using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs).

The concurrent validity was examined by correlating the SOSGOQ2.0 domain score with the domain scores of SF-36, using the Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The domains sharing the same quality aspects were expected to reach a higher correlation of at least .4.

Patients were classified in 2 groups on the basis of the baseline ECOG value (<2, ≥2). The clinical validity of SOSGOQ2.0 was tested as ability in discriminating between patients’ groups, comparing mean scores by the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. A P value of <.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

The reliability of SOSGOQ2.0. was estimated by internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha). Reliability coefficients were calculated for each domain and for the entire instrument by analyzing all 20 items as a single scale. A Cronbach’s α value between .70 and .90 was defined as an accepted standard of minimum reliability. 9 Corrected item-total correlation values were used to identify items which were inconsistent with other items in the SOSGOQ2.0. Corrected item-total correlation values <.2 were deemed as unacceptable. 9 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

The study sample consists of 150 patients. The majority were males (54%) with a median age of 63 years (range 19-89) (Table 2). All patients were affected by spinal metastases (solid metastases 104, hematological metastases 46), even if these lesions were not surgically treated in all cases. Concerning the origin of solid metastases, 29 were from kidney cancer, 23 from breast cancer, 18 were of gastrointestinal origin, and 10 were from lung cancer.

Concerning the spinal localization, there were 40 thoracic localizations, 24 lumbar localizations and 24 thoraco-lumbar localizations (T11-L1), 9 cervical localizations, and 9 cervico-thoracic localizations (C7-T2) (Table 2).

All included patients completed the SOSGOQ 2.0 questionnaire before the surgery. Patients reported high quality of life score on the neurological function items of bowel, bladder, and arms while they reported a low quality of life score on pain and physical function domains (Table 2).

Validity

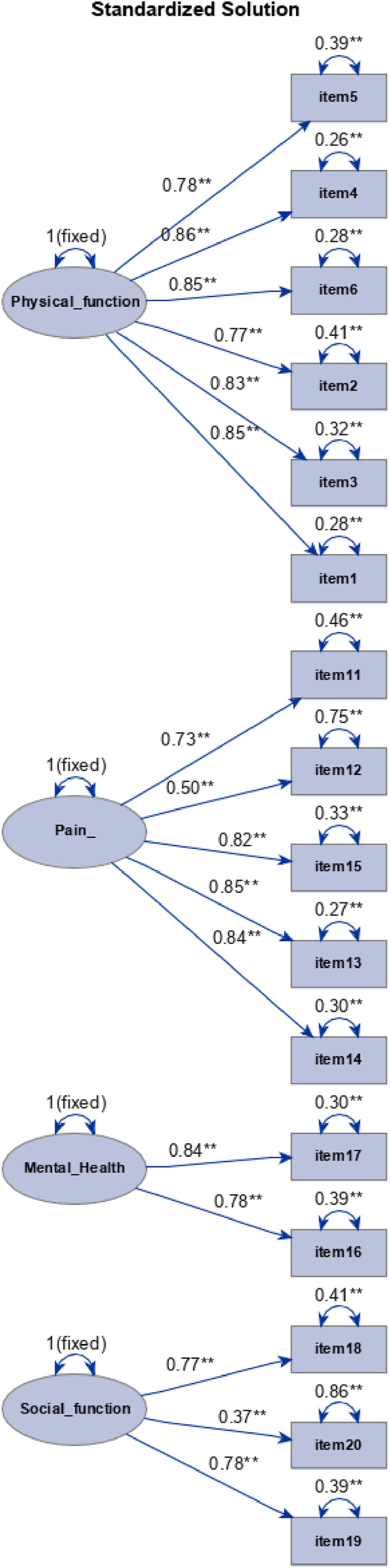

The confirmatory factor analysis on the 4 domains showed a good model fit (CFI, .95; RMSEA .07 (90%CI, .05-.09), and SRMR, .05), endorsing construct validity. The standardized coefficient estimates between each item and the corresponding domains are shown in Figure 2. The standardized coefficients for each items and the corresponding domain ranged from .77 to .86 for physical function, from .50 to .85 for pain, from .78 to .84 for mental health, and from .37 to .78 for social function. Except for item 20, having a coefficient .37 (error variance= .86), all standardized coefficients were greater than .5, suggesting that the items are valid indicators of the 4 domains.

Figure 2.

Path diagram for the standardized solution of the confirmatory factor analysis. Note: the estimates on single-headed arrows that connect domains with items, are the standardized factor loading; the estimate on double-headed arrows above domains represent variance while the estimates on double-headed arrows above itmes represent error variances.

A positive and high correlation was found between the items and their domain confirming convergent validity and a weak correlation was found between neurological function items and the other items in the scale (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman Correlation (rs) Between Item and Domains of the SOSGOQ 2.0 Questionnaire.

| rs | Physical Function | Pain | Mental Health | Social Function | Neurological Function Legs | Neurological Function Arms | Neurological Function Bladder | Neurological Function Bowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | .86 | .54 | .17 | .41 | .42 | .03 | .24 | .14 |

| Item 2 | .81 | .55 | .15 | .43 | .32 | .08 | .24 | .02 |

| Item 3 | .86 | .58 | .25 | .49 | .46 | .13 | .26 | .06 |

| Item 4 | .91 | .55 | .25 | .38 | .46 | .12 | .27 | .10 |

| Item 5 | .82 | .46 | .18 | .27 | .38 | .00 | .23 | .15 |

| Item 6 | .87 | .55 | .32 | .51 | .43 | .10 | .18 | .10 |

| Item 11 | .44 | .84 | .19 | .39 | .21 | .08 | .14 | −.06 |

| Item 12 | .30 | .66 | .20 | .28 | .25 | .12 | .17 | .02 |

| Item 13 | .69 | .83 | .24 | .49 | .39 | .08 | .23 | .16 |

| Item 14 | .59 | .83 | .41 | .54 | .36 | .20 | .25 | .06 |

| Item 15 | .55 | .86 | .38 | .55 | .36 | .09 | .33 | .14 |

| Item 16 | .21 | .29 | .89 | .46 | .20 | .24 | .20 | .14 |

| Item 17 | .26 | .35 | .92 | .45 | .30 | .24 | .19 | .07 |

| Item 18 | .45 | .53 | .44 | .80 | .26 | .09 | .12 | .02 |

| Item 19 | .42 | .49 | .55 | .82 | .32 | .09 | .19 | .16 |

| Item 20 | .32 | .32 | .28 | .72 | .23 | .12 | .13 | .05 |

| Item 7 | .49 | .37 | .29 | .32 | 1.00 | .16 | .31 | .29 |

| Item 8 | .11 | .14 | .26 | .13 | .16 | 1.00 | .26 | .10 |

| Item 9 | .27 | .27 | .22 | .18 | .31 | .26 | 1.00 | .45 |

| Item 10 | .12 | .08 | .11 | .08 | .29 | .10 | .45 | 1.00 |

The analysis of concurrent validity reported in Table 4 demonstrated a strong correlation for physical function, pain and mental health domains and the SF36 domains sharing the same quality of life information (range: .61-.83). A moderate correlation (>.50) was observed for social function domain with SF36 emotional well-being, social functioning and energy/fatigue, and for the neurological function legs item and SF36 physical functioning. Item 8, item 9, and item 10 were uncorrelated with SF36 domains.

Table 4.

Spearman Correlation (rs) Between SOSGOQ 2.0 and SF36 Questionnaire.

| rs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOSGOQ 2.0 | ||||||||

| Physical Function | Pain | Mental Health | Social Function | Neurological Function Legs | Neurological Function Arms | Neurological Function Bladder | Neurological Function Bowel | |

| (Item 1, Item 2, Item 3 Item 4, Item 5, Item 6) | (Item 11, Item 12, Item 13 Item 14, Item 15) | (Item 16, Item 17) | (Item 18, Item 19, Item 20) | (Item 7) | (Item 8) | (Item 9) | (Item 10) | |

| SF36 | ||||||||

| Physical functioning | .83 | .60 | .24 | .49 | .51 | .05 | .24 | .14 |

| Role limitation physical | .61 | .57 | .28 | .47 | .39 | .14 | .23 | .05 |

| Role limitation emotional | .29 | .31 | .56 | .47 | .13 | .16 | .24 | .13 |

| Pain | .56 | .78 | .21 | .42 | .27 | .08 | .21 | −.02 |

| General health | .23 | .35 | .46 | .47 | .28 | .16 | .24 | .15 |

| Emotional well-being | .30 | .39 | .73 | .50 | .19 | .19 | .19 | −.08 |

| Social functioning | .58 | .59 | .44 | .55 | .41 | .13 | .19 | .08 |

| Energy/fatigue | .40 | .53 | .57 | .52 | .30 | .26 | .28 | .08 |

ECOG data was available only on 130 patients, no patient had ECOG performance score of 0. Overall, patients with an ECOG performance score of 1 reported a significantly higher SOSGOQ score compared to patients with ECOG performance score ≥2 (SOSGOQ total score: 62.0±19.3 vs 50.3±19.1, P=.0014). Across the SOSGOQ domains, a significant increase of quality of life for patients with baseline ECOG score of 1 was observed for physical function and social function domains, while for pain and mental health domains the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean Score in Patients with ECOG Performance Score of 1 or ≥2.

| ECOG 1 (n = 48) | ECOG ≥2 (n = 82) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOSGOQ 2.0 | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | |

| Physical function | 64.7 ± 25.8 | 42.0 ± 26.8 | <.0001 |

| Pain | 49.0 ± 24.1 | 43.1 ± 23.9 | .1981 |

| Mental health | 66.2 ± 22.2 | 57.9 ± 25.5 | .0682 |

| Social function | 68.2 ± 24.1 | 58.2 ± 24.3 | .0393 |

| Neurological function legs | 77.1 ± 27.2 | 51.2 ± 38.5 | .0003 |

| Neurological function arms | 79.2 ± 29.8 | 80.8 ± 28.1 | .8646 |

| Neurological function bladder | 85.4 ± 25.2 | 77.7 ± 29.1 | .1018 |

| Neurological function bowel | 94.8 ± 16.3 | 87.5 ± 22.3 | .0230 |

| Total score | 62.0 ± 19.3 | 50.3 ± 19.1 | .0014 |

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the whole SOSGOQ2.0 scale was .91, indicating good internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the physical function, pain and mental health domains were .92, .87, and .79, respectively, also indicating good internal consistency. Regarding social function domain, the alpha coefficient was .65. The corrected item-total correlation was >2 for all items, except for item 8 (r = .16). A low corrected item-total correlation was found also for item 10 (r = .25) and item 20 (r = .34). The deletion of item 8, item 10, and item 20 did not significantly change overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (.92), while Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for social function increased to .75 if item 20 was removed.

Discussion

Primary and metastatic tumors of the spine have a relevant impact on the quality of life of patients, due to a significant impairment in domains that include physical function, neural function, pain, mental health, and social roles.

The literature concerning clinical outcomes in spinal tumors healthcare is characterized by outcome measures that are process variables (including survival, local recurrence, and complications) and some measures of function (like Frankel score, ambulatory status). Moreover, over the past decade there has been an increasing amount of literature reporting on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes.

As a main goal of treatments for spinal tumors is the improvement of HRQOL, patient self-assessment instruments, that permit a direct measure of the value of care as perceived by the patient, are necessary. Self-assessment instruments used in spinal oncology are: cancer-specific questionnaires, as ESAS (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System) and ECOG Performance Status, spine-generic questionnaires (created and largely used for degenerative disease of the spine), as ODI (Oswestry Disability Index), NDI (Neck Disability Index), and others generic HRQOL questionnaires, as SF-36 and EQ-5D. These outcomes instruments are not designed for patients with metastatic tumors of the spine and they are not specific and/or sensitive.

In a patient with metastatic disease of the spine patient-reported quality of life and physical function is determined by psychosocial reactions to the cancer experience, innumerable disease-related issues, and the consequences of treatment of both the primary and secondary lesions.

A disease-specific self-assessment instrument is intended to maximize the specificity of the instrument for a disorder, and the sensitivity of the instrument to detect change in the condition. In response to this, the Spine Oncology Study Group has developed an Outcome Questionnaire specific for patients with metastatic disease of the spine, named SOSGOQ (Spinal Oncology Study Group Outcome Questionnaire). It is based on 6 domains concerning physical function, neural function, pain, mental health, social function and post-treatment evaluation. As most of the other questionnaires used, also SOSGOQ covers all the 4 domains of the International Classification of Function (ICF) which is based on the biopsychosocial model of functioning, disability, and health.

The first version of SOSGOQ, validated by Janssen et al. in 2017, 4 showed its strong correlation with EQ-5D-5 L. In 2018, Versteeg et al. 5 provided a new validation of a second version of SOSGOQ (SOSGOQ 2.0) comparing its items with SF-36, obtaining a good reliability.

Since 2018, our Department participates in MTRON study, an AOSpine multicenter registry that includes 27 centers all over the world: the aim of the registry is to collect data of patients hospitalized and treated for spinal metastases to produce high quality evidences. SOSGOQ is included in the study as self-assessment outcome measure but only for English-speaking countries. In order to reach a higher level of homogeneity between groups we thought that an Italian version of SOSGOQ was needed.

According to the guidelines processed by Beaton et al. in 2000 6 for a transcultural and transethnical translation, we created and validated through a prospective study an Italian version of SOSGOQ 2.0. Beaton and co-workers 6 investigated a suitable method for the translation of self-report measures, considering that the correct syntactic and literal transposition is not sufficient, as a cross-cultural adaptation requires a semantical and conceptual comprehension by patients with different ethno-cultural backgrounds.

Following the same guidelines, recently Luksanapruksa et al. 7 have published a Thai version of SOSGOQ 2.0 validating it with a sample of 68 patients and Datzmann et al. 10 have published a German version of SOSGOQ 2.0.

We enrolled 150 patients surgically treated for spinal metastases, a sample size sufficient to evaluate a statistical significant validity. The results reported in this paper showed an overall good reliability and validity of our Italian version of SOSGOQ 2.0.

A confirmatory factor analysis on the 4 main domains demonstrated the construct validity. All standardized coefficients were greater than .5 suggesting that the items are valid indicators of the 4 domains. Only the item n. 20 results to have a lower coefficient (.37), probably due to a rephrasing of the question in order to achieve a greater adaptation in Italian language.

The analysis of concurrent validity demonstrated a strong correlation for physical function, pain and mental health domains and the SF36 domains sharing the same quality of life information (range: .61-.83), while a moderate correlation (>.50) was observed for social function domain with SF36 emotional well-being, social functioning and energy/fatigue, and for the neurological function legs item and SF36 physical functioning.

Moreover, a good internal consistency was demonstrated by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the whole SOSGOQ2.0 scale (.91), and it was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the physical function, pain, and mental health domains (.92, .87, and .79, respectively). Regarding social function domain, the alpha coefficient was a little lower (.65), probably due the presence of item n. 20, as previously observed.

A limitation of the study was the small number of patients who answered the domain VI questions, concerning post-therapy (only 12 patients). Moreover, these items (21-27) do not have corresponding items in SF-36 questionnaire used as standard for construct validation. Thus, they were not included in the statistical analysis for validation.

Conclusion

Validation data obtained from a prospective study on 150 patients treated for spinal metastases showed that the Italian version of SOSGOQ2.0 proposed here should be considered a specific, reliable, valid and easy to understand tool for evaluating health-related quality of life in Italian patients affected by spinal metastases.

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank AO Spine for having granted permission to use and translate the SOSGOQ 2.0 and in particular Dr. Anne Versteeg for helpful advice and support. The work was support by grant 5×1000 of Italian Ministry for Health- Healthcare research program.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Cristiana Griffoni https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8344-7534

Elisa Carretta https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4534-6000

References

- 1.Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, et al. Bone metastases: An overview. Onco Rev. 2017;11:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprangers MA, Cull A, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Aaronson NK. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Approach to quality of life assessment: Guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Qual Life Res : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 1993;2:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Street J, Lenehan B, Berven S, Fisher C. Introducing a new health-related quality of life outcome tool for metastatic disease of the spine: content validation using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health; on behalf of the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine. 2010;35:1377-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen SJ, Teunis T, van Dijk E, et al. Validation of the Spine Oncology Study Group-Outcomes Questionnaire to assess quality of life in patients with metastatic spine disease. Spine J. 2017;17:768-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Versteeg AL, Sahgal A, Rhines LD, et al. Psychometric evaluation and adaptation of the Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire to evaluate health-related quality of life in patients with spinal metastases. Cancer. 2018;124:1828-1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luksanapruksa P, Phikunsri P, Trathitephun W, et al. Validity and reliability of the Thai version of the Spine Oncology Study Group Outcomes Questionnaire version 2.0 to assess Quality of Life in Patients with Spinal Metastasis. Spine J. 2021;16:S1529-S9430. 00241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd ed.. New York, NY: Guilford publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach's alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datzmann T, Kisel W, Kramer J, et al. eCross-cultural adaptation of the spine oncology-specific SOSGOQ2.0 questionnaire to German language and the assessment of its validity and reliability in the clinical setting. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]