Abstract

Racial health disparities in the United States are a major concern, with Black or African Americans experiencing more morbidity and mortality at earlier ages compared to White Americans. More data is needed on the biological underpinnings of this phenomenon. One potential explanation for racial health disparities is that of accelerated aging, which is associated with increased stress exposure. Black Americans face disproportionate levels of environmental stress, specifically racial/ethnic discrimination. Here we investigated associations between self-reported experiences of discrimination and pubertal development (PD) in a diverse sample of young American adolescents (N=11,235, mean age 10.9 years, 20.5% Black participants) from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. Compared to their non-Black counterparts, Black youth experienced more racial/ethnic discrimination in the past year (10.4% vs 3.1%) and had a greater likelihood of being in late/post-pubertal status (3.6% vs 1.5% in boys, 21.3% vs 11.4% in girls). In both sexes, multivariable regression models run in the full sample revealed a cross-sectional association of experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination with pubertal development (boys: standardized beta [β]=0.123, P<.001; girls: β=0.110, P<.001) covarying for demographics, BMI, and dietary habits. Associations remained significant when controlling for multiple other environmental confounders including other forms of (non-racial/ethnic) discrimination and other environmental adversities including poverty and negative life events, and when using parent-reported assessment of pubertal development. Furthermore, racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with elevated estradiol levels in girls (β=0.057, P=.002). Findings suggest an association between experiences of discrimination and pubertal development that is independent of multiple environmental stressors. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to establish causal mechanism.

Keywords: discrimination, puberty, stress, adolescence, health disparities

1. INTRODUCTION

Black or African Americans experience health disparities compared to White Americans, facing increased morbidity and mortality at younger ages (Smedley et al., 2003). A conceptual framework that aims to explain these disparities is that of the weathering hypothesis (Geronimus, 1992), which suggests that chronic exposure to social and economic adversity leads to comparatively earlier deterioration of health (Forde et al., 2019). It’s well understood that environmental stress is associated with poorer health outcomes; within the context of the weathering hypothesis, stressors that disproportionately affect Black Americans, such as racial/ethnic discrimination, emerge as key to maintaining health disparities across the lifespan (Jones et al., 2019; Williams and Mohammed, 2009). To combat these disparities, it is important to identify and understand biological factors associated with discrimination, which can propel mechanistic investigations of the relationship between racism and health outcomes (Harnett and Ressler, 2021).

One potential mediating mechanism between stress and health outcomes is that of accelerated biological aging – often measured by cellular aging and telomere length in adult populations (López-Otín et al., 2013), and by early pubertal timing in children and adolescents (Colich et al., 2020). While cellular measures of accelerated aging have been tied to morbidity and mortality (Wang et al., 2018), the later-life impacts of early onset puberty are less clear, though evidence suggests links to unhealthy body-mass index (BMI), diabetes, cardiovascular issues, and various psychopathological manifestations, particularly in women (Lee and Spence, 2013). Multiple studies to date have demonstrated that Black Americans face accelerated cellular aging in association with socioeconomic stressors such as racial/ethnic discrimination, which is in turn tied to negative health outcomes (Carter et al., 2019; Geronimus et al., 2010; McKenna et al., 2021; Simons et al., 2020). Few, however, have examined pubertal development in this context.

There is ample data suggesting that Black children begin puberty earlier than other racial groups (Ramnitz and Lodish, 2013), highlighting the need to better understand pubertal development in diverse populations (Deardorff et al., 2019). Despite this, little data exists surrounding the link between experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and aging in youth. Encouragingly, recent work has aimed to address this gap, linking discrimination and racial identity with perceived earlier pubertal timing in 13- to 17-year-old Black adolescent boys (Carter et al., 2020) and girls (Seaton and Carter, 2019). More data is needed, however, regarding the association between discrimination and pubertal development earlier in the lifespan.

Here we investigated the association between experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and pubertal development in a large, diverse, early adolescent (ages 10-11) sample from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (Barch et al., 2018). We aimed to (i) specifically assess the association of racial/ethnic discrimination (over and above other environmental adversities) with advanced pubertal development; and (ii) explore sex- and race-based differences in the discrimination-pubertal development relationship.

2. METHODS

We included data from the 1-year follow-up assessment of the ABCD Study® (data release 3.0; https://abcdstudy.org/; N=11,235, mean age 10.9 years, 52.3% male, 20.2% Black), which was the first assessment of discrimination in this sample. All participants gave assent. Parents/caregivers signed informed consent. The ABCD Study protocol was approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board (IRB), and was exempted from a full review by the University of Pennsylvania IRB.

We used linear regression where the main independent variable was self-reported experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination as measured by the ABCD Youth Discrimination Measure (mean score of 7-item questionnaire, each on a 5-point Likert scale from almost never [1] to very often [5]). The main dependent variable was youth-reported pubertal status as measured by the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; report of pre-, early, mid-, late, post-pubertal status based on bodily changes). Measures used from the ABCD Study are described in detail in the Supplemental Methods. Due to significant sex differences in pubertal development in the study age range (1.9% of the boys were late/post pubertal according to youth-report; 13.5% of the girls were late/post pubertal according to youth-report), we conducted sex-stratified analyses.

Main analyses covaried for age, race (White, Black, Other), Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and dietary habits (measured by the Child Nutrition Assessment [Model 1]). We further assessed the specificity of the association between racial/ethnic discrimination and pubertal development by covarying for (i) other discrimination types (towards non-US born individuals; sexual orientation-based; weight-based [Model 2]); (ii) other, non-discrimination environmental factors (parent education, household income, family poverty, negative life events [Model 3]); and (iii) psychopathology (externalizing and internalizing disorders, psychosis spectrum [Model 4]), which has been suggested as a potential mediator between environmental stress and aging (Wertz et al., 2021).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses using different outcome measures to further test the observed relationship between discrimination and pubertal development: (1) binary late/post-pubertal status (as opposed to pre-/early/mid-pubertal status; based on youth-report PDS); (2) parent-reported pubertal development (based on parent-report PDS); (3) salivary sex hormone levels (testosterone, estradiol, dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA]). We also conducted sensitivity analyses using different measures of discrimination: (1) an abbreviated measure derived from the 7-item questionnaire including only items that specifically reference interpersonal experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination; (2) the individual components of the questionnaire assessing interpersonal discrimination (discrimination by teachers, other adults, peers, and others). To explore potential differences between racial or ethnic groups in the association between discrimination and pubertal development, separate stratified models were run in non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic youths. To account for potential within-family effects, we ran a structural equation model (SEM) accounting for family relatedness.

SPSS 27.0 statistical package and Mplus 8.4 were used for data analysis. Univariate comparisons were made using t-tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical variables, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing when appropriate. Listwise deletion was employed for missing data. Rates of missing data were under 7.1% for discrimination measures and were 8.6% and 13.3% for boys’ and girls’ self-reported pubertal development, respectively. All other missing data were below 3.3%.

3. RESULTS

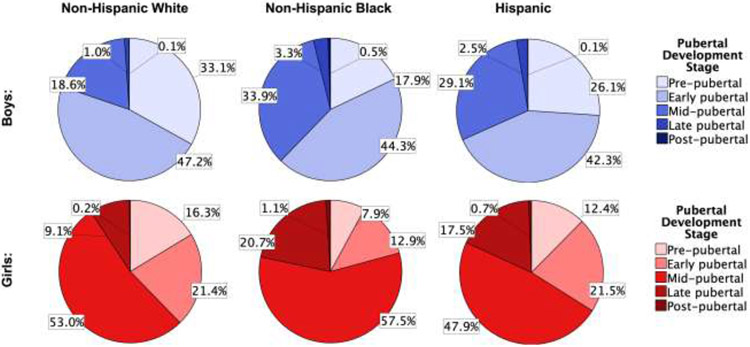

Black participants reported significantly more experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination than non-Black participants over the past year (10.4% vs 3.1%, P<.001). Both Black boys and Black girls had a greater likelihood of being in late/post-pubertal status, assessed by both youth-report (3.6% vs 1.5% in boys, 21.3% vs 11.4% in girls, P’s<.001) and parent-report (3.1% vs 0.8% in boys, 22.0% vs 11.3% in girls, P’s<.001). Full data concerning sex and racial/ethnic differences in pubertal development in the ABCD Study sample are displayed in Figure 1 and supplemental Table S1.

Figure 1. Sex and racial/ethnic differences in progression of pubertal development in the ABCD Study sample.

Youth-reported pubertal development is displayed in relation to sex (boys/girls) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic). Darker color signifies more advanced pubertal development in both sexes.

Racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with advanced pubertal development (See Table 1 for full models’ statistics and Figure 2 for visualization) in both boys (standardized beta [β]=0.123, P<.001) and girls (β=0.110, P<.001) when covarying for age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and dietary habits. These associations remained significant when co-varying for other discrimination types (βboys=0.098, βgirls=0.102, P’s<.001), other environmental factors (βboys=0.077, βgirls=0.088, P’s<.001), and psychopathology (βboys=0.045, Pboys=0.010; βgirls=0.077, Pgirls<.001).

Table 1.

Multivariable modeling of racial/ethnic discrimination’s association with pubertal status

| Boys | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | ||

| Discrimination | Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination | 0.123 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.098 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.077 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.045 | 0.02 | 0.010 |

| Past 12 months discrimination towards non-US born individuals | 0.013 | 0.13 | 0.400 | 0.013 | 0.13 | 0.420 | 0.006 | 0.13 | 0.693 | ||||

| Past 12 months sexual orientation-based discrimination | 0.030 | 0.08 | 0.054 | 0.025 | 0.09 | 0.123 | 0.011 | 0.09 | 0.498 | ||||

| Past 12 months weight-based discrimination | 0.028 | 0.07 | 0.075 | 0.020 | 0.07 | 0.209 | 0.005 | 0.07 | 0.758 | ||||

| Environment | Parental education | −0.043 | 0.02 | 0.038 | −0.037 | 0.02 | 0.072 | ||||||

| Household income | −0.034 | 0.02 | 0.118 | −0.033 | 0.02 | 0.137 | |||||||

| Poverty experiences | 0.014 | 0.02 | 0.403 | 0.015 | 0.02 | 0.366 | |||||||

| Negative life events | 0.057 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.032 | 0.02 | 0.057 | |||||||

| Psychopathology | Psychosis scale | 0.118 | 0.02 | <.001 | |||||||||

| Any externalizing Dx | 0.014 | 0.03 | 0.381 | ||||||||||

| Depression Dx | 0.020 | 0.07 | 0.211 | ||||||||||

| Anxiety Dx | −0.015 | 0.10 | 0.351 | ||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.082 | 0.088 | 0.096 | 0.106 | |||||||||

| Girls | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

| β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | β | S E |

P | ||

| Discrimination | Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination | 0.110 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.102 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.088 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.077 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Past 12 months discrimination towards non-US born individuals | −0.003 | 0.14 | 0.833 | 0.009 | 0.16 | 0.589 | 0.008 | 0.16 | 0.623 | ||||

| Past 12 months sexual orientation-based discrimination | 0.056 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.051 | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.045 | 0.10 | 0.006 | ||||

| Past 12 months weight-based discrimination | −0.013 | 0.07 | 0.420 | −0.022 | 0.07 | 0.177 | −0.026 | 0.08 | 0.112 | ||||

| Environment | Parental education | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.782 | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.594 | ||||||

| Household income | −0.005 | 0.02 | 0.834 | −0.009 | 0.02 | 0.684 | |||||||

| Poverty experiences | 0.020 | 0.02 | 0.232 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.228 | |||||||

| Negative life events | 0.042 | 0.02 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.02 | 0.100 | |||||||

| Psychopathology | Psychosis scale | 0.051 | 0.02 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| Any externalizing Dx | −0.008 | 0.04 | 0.619 | ||||||||||

| Depression Dx | 0.017 | 0.08 | 0.278 | ||||||||||

| Anxiety Dx | −0.022 | 0.09 | 0.153 | ||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.210 | 0.218 | 0.222 | 0.225 | |||||||||

Four linear regression models were run to disentangle the role of racial/ethnic discrimination (independent variable) from other notable stressors in association with pubertal development (dependent variable).

Model 1 covaries for age, race (Black, White, Other), ethnicity (Hispanic), BMI, and dietary habits.

Model 2 builds on Model 1 by adding other types of discrimination and their associated identities (non-US born, identification as LGBT, BMI).

Model 3 builds on Model 2 by adding environmental factors including parental education, household income, family poverty, and life events.

Model 4 builds on Model 3 by covarying for psychopathology (prodromal psychosis scale, any externalizing Dx, depression Dx, and anxiety Dx).

Missing data: Rates of missing values for all variables included in the current study were lower than 3.3%, with the exception of the following discrimination measures (towards non-US born individuals [3.4% in boys], sexual orientation-based [7.0% in boys; 6.3% in girls], and weight-based [4.8% in boys; 3.7% in girls]) and pubertal development measures (youth-report [8.6% in boys; 13.3% in girls])

Abbreviations: β = standardized beta; SE = standard error; P = p-value; UGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender; BMI = body mass index; Dx = diagnosis.

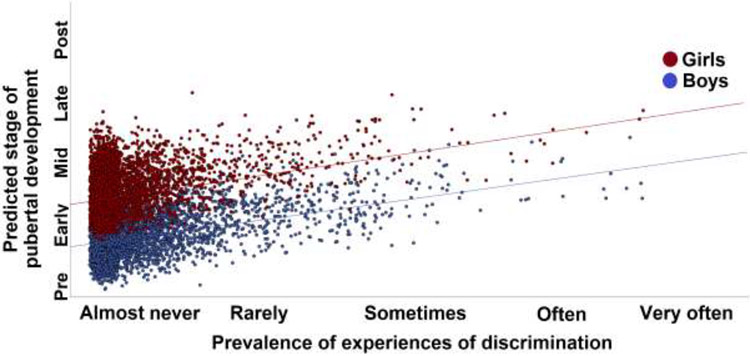

Figure 2. Predicted stage of pubertal development by frequency of experiences of discrimination.

Mean score on the ABCD discrimination questionnaire is plotted against unstandardized predicted value of PDS score derived from a linear regression using mean discrimination score as the independent variable and youth-reported pubertal development as the dependent variable. Model covaries for age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and dietary habits.

Abbreviations: ABCD = Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development; BMI = body mass index.

Racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with binary late/post-pubertal status in Model 1 for both boys (odds ratio [OR]=2.09, 95%CI=1.47-2.96) and girls (OR=2.07, 95%CI=1.60-2.68). These associations remained significant in all remaining models for girls, but only Model 2 for boys (supplemental Table S2). Similarly, discrimination was associated with parent-reported pubertal development in Model 1 for both boys (β=0.033, P=.016) and girls (β=0.059, P<.001). Associations remained significant in all models for girls, while associations were nonsignificant in all other models for boys (supplemental Table S3). Furthermore, racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with elevated estradiol levels in girls (β=0.057, P=.002), but was associated with no other hormone in either sex (supplemental Table S4). Analyses using different measures of discrimination also proved similar.1

Accounting for family relatedness revealed similar findings to main results in direction and significance (ORboys=2.09, Pboys=0.005; ORgirls=2.07, Pgirls<.001; supplemental Table S7). Stratifying by race and ethnicity revealed similar associations between discrimination and pubertal development across non-Hispanic White (βboys=0.142, βgirls=0.082), non-Hispanic Black (βboys=0.065, βgirls=0.094), and Hispanic (βboys=0.164, βgirls=0.181) participants. All findings were significant (P’s<0.01) apart from the model run in non-Hispanic Black boys (P=0.078, see Table 2 for full statistics).

Table 2.

Multivariable modeling of racial/ethnic discrimination’s association with pubertal status stratified by race and ethnicity

| Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P |

| Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination | 0.142 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.065 | 0.03 | 0.078 | 0.164 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.059 | 0.020 | 0.064 | ||||||

| Girls | |||||||||

| Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination | 0.082 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.094 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.181 | 0.04 | <.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.202 | 0.159 | 0.176 | ||||||

Three linear regression models were run to assess the association of racial/ethnic discrimination (independent variable) with youth-reported pubertal development (dependent variable), stratified by race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black) and ethnicity (Hispanic). Non-Hispanic-White- and non-Hispanic-Black-stratified models covary for age, BMI, and dietary habits. Hispanic-stratified model covaries for age, race (Black, White, Other), BMI, and dietary habits. Missing data: Rates of missing values for all variables included in the current study were lower than 3.3%, with the exception of the following pubertal development measures (youth-report [8.6% in boys; 13.3% in girls]).

Abbreviations: β = standardized beta; SE = standard error; P = p-value; BMI = body mass index

4. DISCUSSION

Here we investigated the relationship between racial/ethnic discrimination and pubertal development in a large sample of American youth. In line with existing literature, we found that Black participants both experience disproportionate amounts of racial/ethnic discrimination and show advanced pubertal development at earlier ages compared to their non-Black counterparts (Nagata et al., 2021; Ramnitz and Lodish, 2013). In the full sample, multivariate analyses demonstrate an association between the experience of racial/ethnic discrimination and pubertal development in both sexes that is independent of multiple confounders including other environmental adversities and psychopathology. These associations were also observed in models using parent-reported pubertal development that controlled for demographics (Model 1), though the association in boys became nonsignificant upon addition of environmental confounders (Models 2-4). These findings suggest a specific association between experiences of discrimination and pubertal development. However, it is important to note that the current study design cannot establish directionality of effect. One possibility is that discrimination imposes substantial stress on preadolescent youths, which drives accelerated aging via earlier pubertal development in adolescence (Colich et al., 2020). Nevertheless, another possibility is that the early maturation of Black preadolescents puts them at higher risk to be victimized by their environment, singled out by their peers, and subjected to experiences of discriminated (Nadeem and Graham, 2005).

In the context of this study, it is important to address and discuss important conceptual limitations pertaining to our ability to capture and understand experiences of racism and racial/ethnic discrimination. The tool used to measure these experiences was a 7-item measure administered to preadolescent participants (mean age 10.9 years), including 4 items probing unfair/negative treatment based on the participants’ ethnic background and 3 items probing feelings of exclusion or marginalization in American society. Notably, these items do not directly assess concrete instances of racism/racial discrimination, limiting our ability to capture such experiences and relate findings to the literature on racism-related stress (Harrell, 2000). Despite this, our findings demonstrate a significant association between endorsement of multiple domains of discrimination and advanced pubertal development that should be noted. Interestingly, this association is present in all racial/ethnic groups in our study, including in White participants.

As expected, compared to members of racial and ethnic marginalized groups, White participants of the ABCD Study report a low prevalence (2.8%) of racial/ethnic discrimination (Nagata et al., 2021). One may argue that inclusion of White participants in a study of racial/ethnic discrimination stress is not justified, as this is a unique stressor that impacts people of color. We chose to include the full ABCD Study sample in this analysis, including the White participants. We made this choice as despite their low prevalence, endorsed experiences of discrimination in the White subsample were significantly associated with pubertal development in the current study, and were also demonstrated to be associated with clinical mental health risk previously (Argabright et al., 2021). Due to this apparent clinical significance and the limited granularity in assessment of race, ethnicity, and racial/ethnic discrimination in the ABCD Study, we believe dismissal of these endorsed experiences as insignificant or invalid would be incorrect.

We suggest two potential explanations for the endorsement of experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination by White participants. First, it is likely that the White-identifying sample in the ABCD Study is not homogeneous and includes racial/ethnic groups that have historically been marginalized (e.g., individuals of Middle Eastern descent or Jewish ethnicity). Second, children within the ABCD age range likely have vastly different experiences of racial socialization, the process by which children come to understand the role of race in society and their own lives (Hughes et al., 2006). For example, White children who grow up in families who employ “color-blind” practices tend to develop different understandings of race and racism than families who are “color-conscious” (Hagerman, 2014). Sociologists have demonstrated the consequences of “color-blind” parenting practices, whereby parents may stress the non-importance of racial categories in contemporary society or avoid discussion of race altogether. This can result in children constructing their own explanations for observed racial differences that tend to favor their own group, and which serve to perpetuate racial biases and inequities (Zucker and Patterson, 2018). Thus, differential experiences of racial socialization may significantly alter how children perceive interactions between themselves and their peers and affect their responses to race/ethnic-based discrimination questions in the ABCD Study assessment.

Some further limitations must also be considered. First, we analyzed cross-sectional data, so neither causality nor direction of association between discrimination and pubertal development can be inferred. Second, the association of racial/ethnic discrimination with advanced pubertal development was generally consistent across models and sensitivity analyses in girls, but to a lesser extent in boys. This may be because pubertal development in this study’s age range (9.1-13 years) was heavily skewed, particularly among boys, with very few participants in advanced pubertal stages. This problem was especially limiting in stratified analyses, as dividing the sample further by race and ethnicity limited statistical power to detect a reliable signal, particularly in boys (nWhite boys=56, nBlack boys=37, nHispanic boys=27 at late/post-pubertal status), potentially explaining the lack of an observed statistical significance in Black boys specifically (P=0.078). Despite this, the trend observed in this subgroup was consistent with main results. A lack of power likely explains the lack of statistical significance of models employing parent-reported pubertal development in boys as well, as only 69 boys (1.2%) were reported to be at late/post-pubertal status by parents. As the ABCD cohort matures into mid-late adolescence, future studies will be better powered to investigate stress-puberty associations, particularly in male participants.

4.1. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we present evidence suggesting an association between discrimination and advanced pubertal development. We hope that our findings highlight the need for more detailed phenotyping of race and race-related stressors and propel further investigation aimed at delineating the mechanisms linking discrimination with early pubertal development and accelerated aging, which may have implications for racial health disparities throughout the lifespan (Deardorff et al., 2019; Pfeifer et al., 2021). Together, by combatting bias in academia and openly studying the impacts of race-related stressors on development, we have the power to improve health outcomes for all children.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We studied associations between experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and pubertal development in a large diverse sample of US adolescents (N=11,235, mean age 10.9 years).

Black or African American adolescents were more likely to experience racial/ethnic discrimination and were more likely to be at more advanced pubertal development compared to their non-Black counterparts.

Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination were significantly associated with more advanced pubertal development even when co-varying for multiple environmental stressors.

Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination were associated with elevated estradiol levels in girls.

Acknowledgments:

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development™ (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9-10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study® is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators.

Funding/support:

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers K23MH120437 (RB), R01MH117014 (TMM)]; the Lifespan Brain Institute of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Role of funder/sponsor:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Stirling Argabright: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing, Visualization Tyler Moore: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing- Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition Elina Visoki: Software, Data Curation Grace DiDomenico: Data Curation, Project Administration Jerome Taylor: Writing- Review & Editing Ran Barzilay: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing- Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

All authors significantly contributed to writing the manuscript and have all approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest:

Dr Barzilay serves on the scientific board and reports stock ownership in ‘Taliaz Health’, with no conflict of interest relevant to this work. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Substitution of the discrimination measure with an abbreviated (4-item) measure of interpersonal discrimination was associated with advanced pubertal development in both boys and girls in all models (supplemental Table S5). When breaking this 4-item measure into its components (discrimination by teachers, adults, peers, others), all experiences of discrimination were still associated with pubertal development in both boys (βteachers=0.053, βadults=0.068, βpeers=0.113, βothers=0.075, P’s<.001) and girls (βteachers=0.073, βadults=0.060, βpeers=0.073, βothers=0.077, P’s<.001); see supplemental Table S6.

References

- Argabright ST, Visoki E, Moore TM, Ryan DT, Didomenico GE, Njoroge WFM, Taylor JH, Gur RC, Gur RE, Benton TD, Barzilay R, 2021. Association between discrimination stress and suicidality in preadolescent children. Under Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, Chang L, Clark DB, Glantz MD, Hudziak JJ, Jemigan TL, Tapert SF, Yurgelun-Todd D, Alia-Klein N, Potter AS, Paulus MP, Prouty D, Zucker RA, Sher KJ, 2018. Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci 32, 55–66. 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Seaton EK, Blazek JL, 2020. Comparing associations between puberty, ethnic–racial identity, self-concept, and depressive symptoms among African American and Caribbean Black boys. Child Dev. 91, 2019–2041. 10.1111/cdev.13370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SE, Ong ML, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Lei MK, Beach SRH, 2019. The effect of early discrimination on accelerated aging among African Americans. Health Psychol. 38, 1010–1013. 10.1037/hea0000788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colich NL, Rosen ML, Williams ES, McLaughlin KA, 2020. Biological aging in childhood and adolescence following experiences of threat and deprivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull 146, 721–764. 10.1037/bul0000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Hoyt LT, Carter R, Shirtcliff EA, 2019. Next steps in puberty research: Broadening the lens toward understudied populations. J. Res. Adolesc 29, 133–154. 10.1111/jora.12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde AT, Crookes DM, Suglia SF, Demmer RT, 2019. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann. Epidemiol 33, 1–18.e3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, 1992. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethn. Dis 2, 207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken MT, Pearson JA, Seashols SJ, Brown KL, Cruz TD, 2010. Do US black women experience stress-related accelerated biological aging?: A novel theory and first population-based test of black-white differences in telomere length. Hum. Nat 21, 19–38. 10.1007/s12110-010-9078-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman MA, 2014. White families and race: Colour-blind and colour-conscious approaches to White racial socialization. Ethn. Racial Stud 37, 2598–2614. 10.1080/01419870.2013.848289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harnett NG, Ressler KJ, 2021. Structural racism as a proximal cause for race-related differences in psychiatric disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 579–581. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21050486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP, 2000. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 70, 42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P, 2006. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Dev. Psychol 42, 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NL, Gilman SE, Cheng TL, Drury SS, Hill CV, Geronimus AT, 2019. Life course approaches to the causes of health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 109, S48–S55. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E-Y, Spence J, 2013. Does pubertal timing matter? The association between pubertal timing and health indicators in adulthood. Can. J. Diabetes 37, S286. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.03.338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G, 2013. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna BG, Mekawi Y, Katrinli S, Carter S, Stevens JS, Powers A, Smith AK, Michopoulos V, 2021. When anger remains unspoken: Anger and accelerated epigenetic aging among stress-exposed Black Americans. Psychosom. Med 83, 949–958. 10.1097/psy.0000000000001007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Graham S, 2005. Early puberty, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms in ethnic minority adolescents. J. Early Adolesc 25, 197–222. 10.1177/0272431604274177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Sajjad OM, Benabou SE, Bibbins-Domingo K, 2021. Prevalence of perceived racism and discrimination among US children aged 10 and 11 years: The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 861–863. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Williams JL, Fuligni A, Galván A, Dahl R, Allen N, Burrow A, Leve L, Mackey A, Odgers C, Russell S, Wilbrecht L, Worthman C, Sterling S, Yeager D, 2021. The intersection of adolescent development and anti-Black racism. [Google Scholar]

- Ramnitz MS, Lodish MB, 2013. Racial disparities in pubertal development. Semin. Reprod. Med 31, 333–339. 10.1055/s-0033-1348891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Carter R, 2019. Perceptions of pubertal timing and discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black girls. Child Dev. 90, 480–488. 10.1111/cdev.13221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lei MK, Klopack E, Beach SRH, Gibbons FX, Philibert RA, 2020. The effects of social adversity, discrimination, and health risk behaviors on the accelerated aging of African Americans: Further support for the weathering hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Med 113169. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. 10.17226/12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhan Y, Pedersen NL, Fang F, Hägg S, 2018. Telomere length and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev 48, 11–20. 10.1016/j.arr.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz J, Caspi A, Ambler A, Broadbent J, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Hogan S, Houts RM, Leung JH, Poulton R, Purdy SC, Ramrakha S, Rasmussen LJH, Richmond-Rakerd LS, Thorne PR, Wilson GA, Moffitt TE, 2021. Association of history of psychopathology with accelerated aging at midlife. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 530–539. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA, 2009. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med 32, 20–47. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker JK, Patterson MM, 2018. Racial socialization practices among White American parents: Relations to racial attitudes, racial identity, and school diversity. J. Fam. Issues 39, 3903–3930. 10.1177/0192513X18800766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.