Abstract

Background

The Indian Armed Forces, on entry, vaccinates all cadets and recruits with varicella vaccine for the prevention of varicella. This health technology assessment (HTA) report puts forth evidence for HTA of varicella vaccination in the Armed Forces in various domains namely clinical, societal, ethical, economic, and legal.

Methods

The policy question under each domain has been developed according to best-practice methods for HTA. The costs included were hospitalization cost due to varicella infection; training lost cost; the varicella vaccine cost; cost of the side effects of vaccine; and the outbreak investigation cost. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for varicella cases averted and man-days saved, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained due to varicella vaccination strategy were calculated.

Results

Evidence suggests a reduction of 81% in hospitalization rates with 19392 man-days saved per 1 lakh population due to varicella vaccination strategy. The ICER for varicella cases averted is estimated to be Rs 56732/- per case averted and Rs 5687/- per man-day saved. QALYs gained due to two-dose varicella vaccination strategy is estimated to be 1152 per 1 lakh population with cost per QALY gained Rs 95735/-.

Conclusion

The study showed a large reduction in hospitalizations and consequently man-days lost after the introduction of the vaccination strategy. The QALYs was another aspect of importance brought out by this study. Thus, a two-dose vaccination strategy for varicella-zoster virus (VZV) for the Armed Forces trainees is a cost-effective policy.

Keywords: Health technology assessment, Cost effectiveness, Varicella, Chickenpox

Introduction

Varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles) is caused by the Varicella-zoster virus (VZV).1 Varicella spreads through direct contact and by the respiratory way by inhalation of aerosols,2 with an incubation period of 10–21 days.3 Varicella is highly infectious with a large reproduction number or transmissibility (R0) with an average number of secondary infections produced by primary cases ranging from 12 to 18 and a secondary attack rate of >80% (range 61–100%).4 The temperate and tropical regions show epidemiological variations throughout the world. In temperate countries like the United States and the UK, 95–100% seropositivity is seen in 6–8 years and early adolescence;5 however, tropical regions have different age-specific seroprevalence6. Specifically, India witnesses chickenpox in early adulthood and beyond.6

The Indian Armed Forces, under the Ministry of Defence (MoD) of the Government of India, is the world's third-largest military with a strength of over 1.4 million. The Army Medical Core is responsible for providing health services to the Armed Forces of India. As per the annual health report of the Armed Forces for the year 2018, the hospitalization admission rate due to chickenpox was 2.21/1000 for cadets and 2.93/1000 for recruits. The overall morbidity due to chickenpox is 2.44/1000 for the Armed Forces. Due to close living conditions and training environments, susceptibility to chickenpox in the Armed Forces personnel is unavoidable. High attack rate and aerosol spread makes it very conducive for the virus to spread quickly through close social contacts in the military.7 Substantial morbidity and absence from work is reported due to chickenpox illness, which can last up to 2 weeks as also the management of outbreaks is difficult in densely populated military camps. Many economically developed countries like United States, Germany, Australia, Spain, Greece, and Italy have adopted the WHO recommendation of the universal routine varicella vaccination program.2,8, 9, 10 Many militaries around the world, including the United States, UK, Singapore, Iran, Canada11,12 have varicella vaccination policy implemented for their Armed Forces. The Indian Armed Forces adopted the strategy to vaccinate recruits and cadets as part of the vaccination policy against varicella in the year 2013, although it is not a part of the routine vaccination schedule of the country. Studies from the United States13, 14, 15 and Israel16 have reported varicella vaccination in the military population to be cost-effective with reduced incidence of chickenpox cases and hospitalization.

As per World Health Organisation (WHO), Health technology assessment (HTA) is the systematic evaluation of the technology in terms of its properties and effects, which would help in informed decision making. It is a multidisciplinary field that evaluates the various domains, namely clinical, economic, social, and ethical. These domain evaluations help answer the research questions around investment. It is important for the Armed Forces to assess whether it is worth investing in varicella vaccination.

There is no study available for uniformed forces, specifically the Indian Armed Forces, regarding the cost-effectiveness of the introduction of varicella vaccination. This paper fills the gap in this context with the main objectives under each of the domains of HTA and based on the best practices17 for undertaking HTAs. The objectives w.r.t clinical effectiveness were addressed in terms of estimating the man-days lost due to varicella infection in the Armed Forces and the varicella cases averted due to vaccination. In terms of the value of money, the specific question addressed was the cost-effectiveness of adding the varicella vaccine to the existing immunization schedule as compared to no introduction of the varicella vaccine from the healthcare provider's perspective. In terms of the social aspect, it is the acceptability of the vaccine by the population, and in ethical considerations, the benefits of vaccination, or costs of not vaccinating and equity in vaccination in different groups. We also calculated the Quality of Life years gained due to varicella vaccination.

Materials and methods

A full comprehensive health technology assessment of varicella vaccination in the Armed Forces is carried out in this study after obtaining institutional ethical clearance. All the domains of Health Technology are being worked on in terms of health problems, and current use technology, Safety and Clinical effectiveness of vaccination, Costs and economic evaluation of vaccination, and the ethical, organizational and legal aspects of varicella vaccination are also explored from the healthcare provider's perspective.

For estimating the burden of disease, information was extracted from annual health report of the Armed Forces18 Management Information System Organization (MISO) data and from data of the three directorates of Army, Navy, and Air Force. Information was collected on hospitalization rates and duration of hospitalization. We also used literature and experts' information for other parameters and assumptions. The prevaccination average rate of hospitalization was considered for 10 years from 2003 to 2012 before the varicella vaccination policy was introduced in the Armed Forces. Data for the years 2014–2016 were not considered for analysis due to nonavailability, as well as the interrupted flow of vaccines in the Armed Forces. Post-2016, the supply chain functioned effectively and hence postvaccination average hospitalization due to varicella was calculated based on the reported hospitalization for the years 2017 and 2018. The data on man-days lost because of hospitalization due to varicella were obtained separately for cadets and recruits from MISO and the three directorates of Army, Navy, and Air Force. Man-days lost was described as mean (SD).

Economic evaluation in terms of cost-effectiveness analysis was carried out. The costs included were: hospitalization cost due to varicella; training lost cost; the varicella vaccine cost; cost of the side effects of the vaccine; and the outbreak investigation cost. The training cost and hospitalization cost were obtained from the hospital stoppage rates (HSR) as per the Regulations for Medical Services in Armed Forces 2010 (RMSAF).19 Negligible cost was assumed for the administration of varicella vaccination as the mass vaccination for varicella of cadets and recruits upon entry is part of an existing vaccine program for other diseases. The costs of the vaccination were compared with the benefits in terms of the number of varicella cases averted and man-days saved. The Incremental Cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for varicella cases averted and man-days saved were calculated. We also calculated Quality- Adjusted Life years (QALYs) gained due to the varicella vaccination strategy. As morbidity due to VZV is more compared to mortality, QALYs is a more appropriate measure than life-years gained. All costs are considered in INR. The affordability by the receiver was not assessed as it was provided free of cost by the organization. The statistical software used was IBM SPSS version 23.0 (IBM USA).

Sensitivity Analysis was performed varying the hospitalization days after acquiring varicella and outbreak investigation days. The coverage of varicella vaccination is 100% in the Armed Forces and was not used in the sensitivity analysis. The values for the variables varied from 50% to 150% of their original values, and their effects on cost were evaluated.

Results

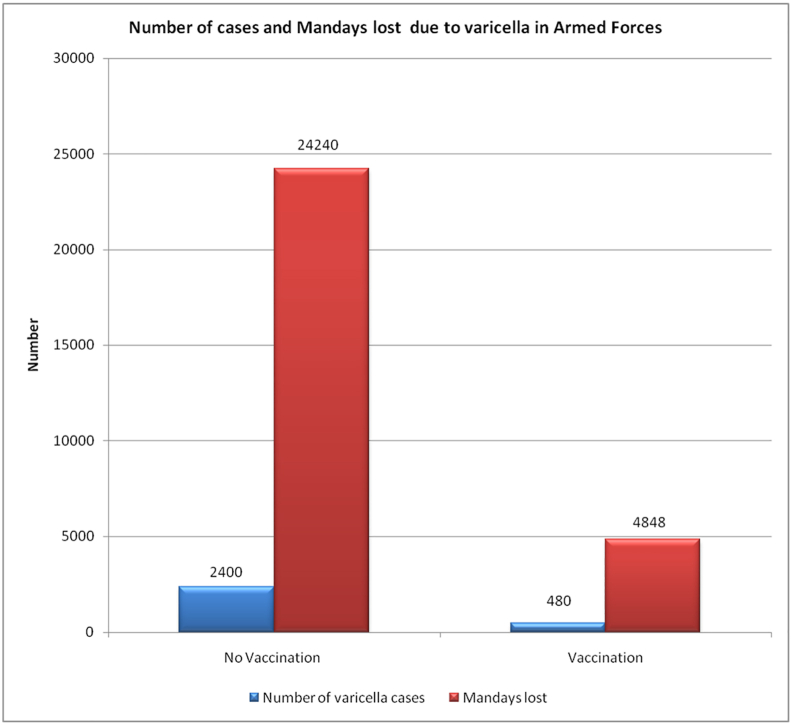

Hospitalization rate due to Chicken Pox for 10 years prior to vaccination program in the Armed Forces, as per Annual Health report 2018, is presented in Table 1. The average rate of hospitalization prevaccination, from 2003 to 2012 was 24 per 1000 (SD = 7.99), whereas postvaccination was 4.57 per 1000 (SD = 1.65). The average number of man-days lost from varicella was 9.96 (SD = 2.68) days for officer trainees and 10.25 (SD = 2.75) days for nonofficer trainees. Combined man-days lost due to hospitalization for both was 10.10 (SD = 2.71) days per case of varicella. By assuming a hypothetical cohort of 1,00,000 (1 lakh) trainees, of 1 lakh total, 6% will be officer trainees and 94% non-officer trainees as per information from O/o DGAFMS. Table 2 provides details of estimates of cases averted and man-days saved. Reduction of 81% in hospitalization rates is seen due to varicella vaccination with a total of 19392 man-days saved per 1 lakh population due to varicella vaccination strategy. Fig. 1 shows the number of cases and man-days lost due to varicella in the Armed Forces as per vaccination strategy.

Table 1.

Incidence per 1000 of varicella for the year 2003–2018.

| Year | Incidence per 1000 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadets | Recruits | Combined | |

| 2003 | 34.36 | ||

| 2004 | 14.93 | ||

| 2005 | 34.00 | ||

| 2006 | 29.24 | ||

| 2007 | 25.50 | ||

| 2008 | 25.39 | ||

| 2009 | 25.40 | ||

| 2010 | 22.24 | ||

| 2011 | 10.87 | 9.84 | 10.36 |

| 2012 | 22.69 | 9.38 | 16.04 |

| 2013 | 1.81 | 7.79 | 4.80 |

| 2014 | 7.21 | 6.38 | 6.79 |

| 2015 | 6.71 | 12.13 | 9.42 |

| 2016 | 6.68 | 17.01 | 11.85 |

| 2017 | 4.00 | 8.20 | 6.10 |

| 2018 | 2.11 | 3.54 | 2.82 |

Table 2.

Estimates for cases averted and man-days saved.

| S No | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Average hospitalization rate pre vaccination per 1000 (SD) | 24 (7.99) |

| 2 | Number of cases due to varicella with no varicella vaccination strategy per lakh | 2400 |

| 3 | Average hospitalization rate post vaccination per 1000 (SD) | 4.57 (1.65) |

| 4 | Number of cases due to varicella with two-dose varicella vaccination strategy per lakh | 480 |

| 5 | Reduction in hospitalization rates (cases averted due to varicella vaccination) | 81% |

| 6 | ∗Average number of man-days lost for officer trainees (SD) | 9.96 (2.68) |

| 7 | Average number of man-days lost for nonofficer trainees (SD) | 10.25 (2.75) |

| 8 | Combined man-days lost for all trainees (SD) | 10.10 (2.71) |

| 9 | Total man-days lost per 1 lakh population (10.10 × 2400) | 24,240 |

| 10 | Total number of varicella cases averted due to vaccination strategy (81% reduction of 2400 cases per one lakh population) | 1944 |

| 11 | Total man-days saved per 1 lakh population due to varicella vaccination strategy (24240- (480∗10.10) =(24,240–4848) | 19,392 |

Fig. 1.

Number of cases and man-days lost due to varicella in Armed Forces.

Cost analysis (what costs were included)

The following costs in INR were included for cost-effectiveness analysis. Table 3 gives the total cost of varicella in cadets and recruits derived from the system.

-

A.

Hospitalization cost due to varicella

Table 3.

Total cost of varicella in cadets and recruits derived from system.

| Vaccination program | Cadet | Recruit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Cost | 650 (INR) Per Dose (2 doses required) | 650 (INR) Per Dose (2 doses required) | O/o DGAFMS a per the rate contract |

| Rate of side effects | 5% | 5% | |

| Cost of vaccine side effects | One man-day lost per dose administration (Total 2 man-days lost) | One man-day lost per dose administration (Total 2 man-days lost) | Estimated |

| Training cost associated with one man-day lost | 1343/- per day | 286/- per day | O/o DGAFMS, AMC, Lucknow, ASC Banglore and AFMC |

| Cost of hospitalization for varicella | 1800/- per day | 450/- per day | Hospital Stoppage Rates |

| Man-days lost due to hospitalization due to varicella | Mean = 9.96 days SD = 2.68 |

Mean = 10.25 days SD = 2.75 |

Annual Health Report, MISO data, Data obtained from the Army, Navy and Air Force Directorate |

| Cost associated with Man-days lost due to hospitalization due to varicella | 1800∗9.96 = 17928 | 450∗10.25 = 4612.5 | Estimated |

| Lost training (productivity) cost due to hospitalization due to varicella | 1343∗9.96 = 13376.28 | 286∗10.25 = 2931.5 | Estimated |

| Cost of outbreak management of varicella | 100 man-days lost | Estimated | |

| Average number of varicella outbreaks in a year | 2 | Annual Health Report |

The hospital stoppage rates (HSR)19 for one-day hospitalization cost for officer and nonofficer Trainees is Rs 1800/- and Rs 450/-, respectively.

These costs include basic medication and hospitalization bed, including diet. The number of cases hospitalized due to varicella with no varicella vaccination was 2400 cases per 1 lakh population per year.

Assuming the distribution of hospitalization of cadet to recruit due to varicella at 6%–94% respectively, that is, 144 and 2256 out of 2400, respectively, the average number of man-days lost by cadets and recruits to hospitalization due to varicella is 9.96 and 10.25 days, respectively; hospitalization cost due to varicella per cadet = 1800∗9.96 = 17928; hospitalization cost due to varicella per recruit = 450∗10.25 = 4612.5;

Thus, total hospitalization cost due to varicella per year = 17928∗144 + 4612.5∗2256 = 12987432.

-

B.

Training lost costs

(Data were obtained from the AMC, Lucknow, ASC Banglore and AFMC, Pune).19

Training cost for cadets = Rs 9400/- per week (Rs 1343/- per day); Training cost for recruits = Rs 51480/- per 6 months (Rs 286/- per day); Lost training (productivity) cost due to hospitalization for varicella: For cadets = 1343∗9.96 = 13376.28; For recruits = 286∗10.25 = 2931.5.

Thus, total training lost cost due to varicella per year = 13376.28∗144 + 2931.5∗2256 = 8539648.

The training cost Non-AMC unit and Non-ASc units are considered to be similar.

-

C.

Varicella vaccine cost

The varicella vaccine cost is obtained from the O/o DGAFMS as per the rate contract.

Cost of one dose of varicella vaccine = Rs 650/- per dose. Each cadet and recruit is being given two doses of varicella vaccine. Hence the cost for two doses of vaccine per person = Rs 1300/-.

Thus, total vaccine cost for vaccinating a cohort of 1,00,000 population = Rs. 1,300,00,000/-

-

D.

Cost of side effects of vaccine

It is assumed that approximately 5% of cadets and recruits vaccinated would suffer one man-day loss due to fever and rash as side effects.20 Vaccine is administered twice, thus 2 days of training cost per person who experiences side effects = 5%∗total number of given vaccines∗cost of 2 lost days):

For cadets = 0.05∗6000∗1343∗2 = 805800; For recruits = 0.05∗94000∗286∗2 = 2688400;

Total Cost of side effects of vaccine = 805800 + 2688400 = Rs. 34,94,200.

-

E.

Outbreak investigation cost

Two or more cases of varicella within 3 weeks in the same unit, including the index case, are defined as an outbreak.21 It is estimated that approximately 100 workdays will be utilized to initiate preventive measures to investigate an outbreak, from the start of contact tracing to report submission.22 On an average two outbreaks of varicella occur per year in the Armed Forces (Annual health report). The outbreak investigation team considered is a mid-level epidemiologist (Lt Col), and two ORs. The average per day salary without taxation for Lt Col is considered to be Rs 6900/- and for ORs as Rs 1500/- per day. The number of cases hospitalized and the training cost is considered in respective subheads.

Number of days lost in investigating an outbreak of varicella = 100 man-days lost.Thus.

Outbreak Investigation Cost = Rs 16,80,000/-

-

F.

Vaccine administration Cost

As the mass vaccination for varicella of cadets and recruits upon entry is part of an existing vaccine program for other diseases, negligible costs are assumed for the administration cost for the varicella vaccine.

Cost-effective analysis

The costs of the vaccination were compared with the benefits in terms of the number of varicella cases averted and man-days saved.

Total Cost with no varicella vaccination = Hospitalization cost due to varicella+ Training Lost Costs + Outbreak Investigation Cost = 12987432 + 8539648+1680000 = 23207080.

Total cost of varicella vaccination = Varicella vaccination cost+ Vaccine administration Cost+ Cost of side effects of vaccine = 130000000 + 0+3494200 = 133494200/-

Additional cost incurred = ΔC=(Total cost of varicella vaccination strategy)- (Total cost without varicella vaccination strategy) = 133494200-23207080 = Rs 110287120/-

Additional benefits in terms of cases averted = = Δd = 1944 cases averted;

Additional benefit in terms of man-days saved = Δd = 19392 man-days saved.

Incremental Cost-effectiveness ratio for varicella cases averted

= ICER = ΔC/Δd = 110287120/1944.

= Rs 56732.

= Rs 56732/- per case averted.

Incremental Cost-effectiveness ratio for man-days saved

= ICER = ΔC/Δd = 110287120/19392.

= Rs 5687.23.

= Rs 5687/- per man-days saved.

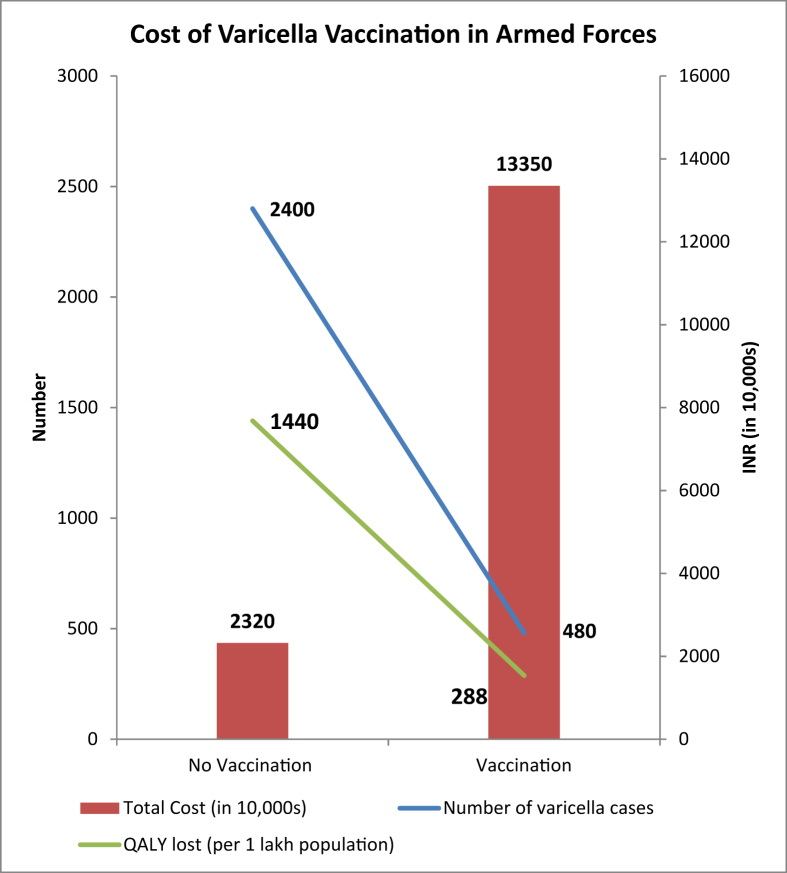

Quality-Adjusted Life years gained

We used cost per QALY as the primary outcome.

Number of cases due to varicella with no varicella vaccination strategy.

= 2400 cases per 1 lakh population.

Quality of Life lost in adults during hospitalization due to varicella = 0.60

Total number of QALYs lost during hospitalization with no varicella vaccination per 1 lakh population = 2400∗0.60 = 1440 per 1 lakh population.

Number of cases due to varicella with two-dose varicella vaccination = 480 cases per 1 lakh population.

Total number of QALYs lost during hospitalization with two-dose varicella vaccination per 1 lakh population = 480∗0.60 = 288 per 1 lakh population.

QALYs gained due to two-dose varicella vaccination strategy = ΔQ = 1152 per 1 lakh population.

Cost per QALY gained = ΔC/ΔQ = 110287120/1152 = Rs 95735/-

Equity and ethics

As per the Annual Health report, hospitalization due to varicella has seen an increasing trend not only for cadets and recruits but also for MNS (nursing cadre), especially in the Army.

Sufficient coverage

For the profits of varicella vaccination to be recognized in the Armed Forces, it is necessary to vaccinate all of the population. As per the Armed Forces Immunization Schedule for serving personnel, including cadets and recruits by O/o DGAFMS, it is mandatory for all the cadets and recruits on entry, two doses of Varicella Vaccine (live attenuated vaccine against chicken pox) four weeks apart 0.5 ml subcutaneous injection (outer upper aspect-Deltoid). Coverage rate is 100%; however, there are other barriers to vaccination in terms of the vaccine not available at times, which need to be addressed.

Legal issues

Varicella vaccination may see a surge in the incidence of Herpes Zoster. The Annual Health report of the Armed Forces by the O/o DGAFMS covers the morbidity/mortality and trend of hospitalization due to chickenpox for all the subcategories of the population i.e. Officers (male/female), MNS, JCO/OR, Cadets, and Recruits. While varicella zoster infection or chickenpox is currently listed under ICD No B01, Herpes Zoster infection is not currently listed in the Annual Health report at all.

Fig. 2 shows the cost of varicella vaccination in the Armed Forces.

Fig. 2.

Cost of varicella vaccination in the Armed Forces.

Sensitivity Analysis

The model was more sensitive to days lost due to hospitalization with ICER per case averted Rs 62371/- for 50% of the original value and Rs 51502/- for 150% of original value i.e. for 5 days of hospitalization and 15 days of hospitalization, respectively. Similarly, the ICER per man-days saved was Rs 12630/- and Rs 3476/-, respectively. The cost per QALY gained was Rs 105251/- and Rs 86909/-, respectively. When varicella outbreak investigation days lost was varied over 50–150% for sensitivity analysis, ICER per case averted Rs 57164/- and Rs 56300/-, respectively. ICER per man-days saved was Rs 5730/- and Rs 5643/-, respectively, and cost per QALY gained was Rs 96464/- and Rs 95006/-, respectively.

Discussion

Childhood vaccination paves the way for adult immunization. In adults, the immunization guidelines vary as per region, unlike the Paediatric Immunization Guidelines. For protecting the susceptible adult population, the requirement for vaccination in adults is to boost efficacy and protect when the immunity of an individual decreases. But this vaccination may not have an effect on the epidemiology of the disease but will protect at-risk adult individuals. However, child vaccination will have a significant impact on the epidemiology of the disease. The elimination of disease will depend on high vaccine coverage to shift in older children and adults with partial coverage. At present, this vaccine will have a lower priority in the National Immunization Schedule that does not have MMR and typhoid, which have a greater socioeconomic impact. Hence, at the present time, WHO does not recommend the inclusion of varicella vaccination into the routine immunization programs of developing countries.23

Although susceptibility is similar in military personnel compared to their age-matched civilian counterpart, the work and living environment of military personnel promotes the rapid spread of highly contagious infections like varicella.24 The trainees with chickenpox living in the barracks and dwellings are routinely isolated and hospitalized to avoid the spread of the epidemic. Even if chickenpox does not cause severe illness, the military consequences are high. Post varicella infection trainees need hospitalization of around 2 weeks for recovery, which disturbs the training schedules and affects the operational functioning of the military. Investigating a varicella outbreak costs time and money for screening and tracing the contacts and vaccinating the susceptible population.22 Varicella infection can result in high morbidity and mortality, especially in young adults, and the risks increases with increasing age.25 Outbreak of chickenpox is quite often reported in training institutes under the Armed Forces, where students share rooms and have common dining facilities.26

A review of the literature on vaccine efficacy for two doses show better protection around 93% compared to one dose of any varicella vaccine at 80%.27 Studies report 70–90% vaccine efficacy against varicella infection, and 90–100% against moderate and severe disease and confers protection ranging from 11 to 20 years.28 It is also suggesting that the vaccine is safe. Countries that have introduced varicella vaccination show a reduction in incidental cases and hospitalizations, and deaths. Our study is consistent with the findings of studies in militaries showing vaccination reduces the incidence of chickenpox.29 Another study on US military recruits found that vaccination reduced the chickenpox cases by 80% and was also the most cost-effective decision.30 Our study noted an 81% reduction in the hospitalization rates (from 2400 to 456) due to varicella vaccination. Cost-effectiveness studies on varicella on a specific population of the military have shown a high cost of vaccination. A study on the US Army evaluating varicella vaccination strategies concluded that the most cost-effective strategy was serologically testing soldiers and vaccinating those without protective antibodies.14 A study on vaccination in the Singapore Armed Forces estimated 72.0 work days per 1000 saved at the cost of SG$6,544 per 1000.21 A study on French adolescents and adults also showed vaccination to be effective.31 A study in England estimated 651000 cases of varicella resulting in 18000 QALYs lost. Adolescent vaccination is estimated to be cost-effective at £18,000 per QALY gained.32 Our study has certain limitations. There is a likelihood of underreporting of cases due to atypical or subclinical in the vaccinated cohort. The outbreak investigation cost is assumed to be 100 man-days lost based on literature and not estimated for our study. As the trainees in the Armed Forces are young, the study lacks generalizability to other nonmilitary settings; however, our study results have high internal validity and generalizable to similar age populations staying in shared spaces.

Conclusions

The study showed a large reduction in hospitalizations and consequently man-days lost after the introduction of the vaccination strategy for the Armed Forces trainees (cadets and recruits). A large reduction in man-days lost was also evident from the analysis. The QALYs was another aspect of importance brought out by this study. Thus, a two-dose vaccination strategy for VZV for the Armed Forces trainees is a cost-effective policy. It appears prudent that the nonavailability, as well as the interrupted flow of vaccines in the Armed Forces, derails the benefits achieved by vaccination, and hence, effective supply chain functioning needs to be maintained. Periodic reviews of the results of the varicella vaccination program are likely to benefit both the authorities and the cadets and recruits. Data from healthy young adults in the military should be tracked closely, as they are likely to reveal changes in the evolving epidemiology of varicella in the post-vaccine era.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

(a) This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 4654/2015 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

(b) We also acknowledge the help provided by AMC Lucknow, ASC Bangalore and the Armed Forces Medical College (AFMC), Pune and the Hospital Stoppage Rates from the Hospital Administration, Department of AFMC, Pune.

(c) Our sincere thanks to the three directorates of Army, Navy, and Air Force and the Management Information System Organization (MISO).

References

- 1.Mueller N.H., Gilden D.H., Cohrs R.J., Mahalingam R., Nagel M.A. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.011. 675-viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moffat J., Ku C.C., Zerboni L., et al. In: Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Arvin A., Campadelli-Fiume G., Mocarski E., et al., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. VZV: pathogenesis and the disease consequences of primary infection.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47382/ Chapter 37. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varicella (Chickenpox), Center for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, [accessed 14 May 2020] https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/transmission.html.

- 4.Jane F Seward, Mona Marin, Varicella Disease Burden and Varicella Vaccines On behalf of the SAGE VZV Working Group, WHO SAGE Meeting April 2, 2014, CDC Immunization https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/april/2_SAGE_April_VZV_Se ward_Varicella.pdf?ua=1.

- 5.Munech R., Nassim C., Nikku S. Sero-epidemiology of varicella. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:153–155. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee B.W. Review of varicella zoster epidemio-logy in India and South East Asia. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;11:886–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National advisory committee on immunization (NACI) update on varicella. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2004 Feb 1; 30:1-26. [PubMed]

- 8.Macartney K.K., Burgess M.A. Varicella vaccination in Australia and New Zealand. J Infect Dis. 2008 Mar 1;197(suppl 2):S191–S195. doi: 10.1086/522157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch Robert. Institut Empfehlungen der StändigenImpfkommission (STIKO) am Robert Koch-Institut/Stand: July 2006. Epidemiol Bull. 2006;30:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin M., Güris D., Chaves S.S., Schmid S., Seward J.F., Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007 Jun 22;56(RR-4):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabenstein John D., Pittman Phillip R., Greenwood John T., Engler Renata J.M. Immunization to protect the US armed forces: heritage, current practice, and prospects. Epidemiol Rev. August 2006;28(1):3–26. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep) 2007;56(RR-4):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan M.A., Smith T.C., Honner W.K., Gray G.C. Varicella susceptibility and vaccineuse among young adults enlisting in the United States Navy. J Med Virol. 2003;70(suppl 1):S15–S19. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerant A.F., DeGaetano J.S., Epperly T.D., Hannapel A.C., Miller D.R., Lloyd A.J. Varicella susceptibility and vaccination strategies in young adults. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:296–306. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.11.4.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrin V.E., Gray G.C. Decreasing rates of hospitalization for varicella among young adults. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:835–838. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mimouni D., Levine H., Tzurel Ferber A., Rajuan-Galor I., Huerta-Hartal M. Secular trends of chickenpox among military population in Israel in relation to introduction of varicella zoster vaccine 1979–2010. Hum Vaccin Immun other. 2013;9:1303–1307. doi: 10.4161/hv.23943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busse R., Orvain J., Velasco M. Best practice in undertaking and reporting health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:361–422. doi: 10.1017/s0266462302000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annual Health Report of Armed Forces. AHR); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regulations of Medical Services in Armed Forces. RMSAF); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wise R.P., Salive M.E., Braun M.M., Mootrey G.T., Seward J.F., Rider L.G., Krause P.R. Postlicensure safety surveillance for varicella vaccine. JAMA. 2000 Sep 13;284(10):1271–1279. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh J.J.K., Ho M., Koh W.M., et al. An economic analysis of varicella immunization in the Singapore military. Military Med Res. 2016;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40779-016-0070-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez Adriana S., Marin Mona. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Strategies for the Control and Investigation of Varicella Outbreaks Manual.https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/outbreaks/manual.html#appx [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhave S.Y. Controversies in chicken-pox immunization. Indian J Pediatr. 2003 Jun;70(6):503–507. doi: 10.1007/BF02723143. PMID: 12921321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afshar Paiman S., Izadi M., Jonaidi Jafari N., et al. Varicella Susceptibility in Iran military conscripts: a study among military garrisons. ArchClin Infect Dis. 2017;12(1) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guess H.A., Broughton D.D., Melton LJ 3d, Kurland L.T. Population-based studies of varicella complications. Pediatrics. 1986;78(4 Pt 2):723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatti V.K., Budhathoki L., Kumar M., Singh G., Nath A., Nair G.V. Use of immunization as strategy for outbreak control of varicella zoster in an institutional setting. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70(3):220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cenoz M.G., Martinez-Artola V., Guevara M., Ezpeleta C., Barricarte A., Castilla J. Effectiveness of one and two doses of varicella vaccine in preventing laboratoryconfirmed cases in children in Navarre, Spain. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9:1172–1176. doi: 10.4161/hv.23451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause P., Klinman D. Efficacy, immunogenicity, safety, and use of live attenuated chickenpox vaccine. J Pediatr. 1995;127:518–525. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray G.C., Palinkas L.A., Kelley P.W. Increasing incidence of varicella hospitalizations in United States Army and Navy personnel: are today's teenagers more susceptible? Should recruits be vaccinated? Pediatrics. 1990 Dec;86(6):867–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan M.A., Smith T.C., Honner W.K., Gray G.C. Varicella susceptibility and vaccine use among young adults enlisting in the United States Navy. J Med Virol. 2003;70(suppl 1):S15–S19. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanslik T., Boëlle P.Y., Schwarzinger M., et al. Varicella in French adolescents and adults: individual risk assessment and cost-effectiveness of routine vaccination. Vaccine. 2003;21(25-26):3614–3622. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brisson M., Edmunds W.J. Varicella vaccination in England and Wales: cost-utility analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(10):862–869. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.10.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]