Introduction

Medication-related problems are a significant contributor to morbidity, mortality and health care resource utilization in Canada and globally.1 -5 Medication reviews are 1 proposed strategy to help reduce preventable adverse drug events and hospital admissions. 6 A medication review consists of a structured, critical examination of a patient’s medications and aims to provide education, improve medication adherence, resolve drug therapy problems and optimize medication management. The ultimate goal is to yield better health outcomes for the patient. 7

While informal medication review is encompassed in the scope of practice for all pharmacists across Canada, government reimbursement for these services is not universal. Ontario was the first province to compensate community pharmacies for medication reviews, introducing the MedsCheck program in 2007 and expanding to include patients with diabetes, home-bound patients and residents of long-term care homes in 2010. 8 Although the terminology and eligibility of programs vary, 8 provinces reimburse pharmacies for providing medication review services. Please refer to Table 1 in brief and Appendix 1 (available in the online version of the article) for a detailed summary of publicly funded fee-for-service medication review services across Canadian provinces and territories. The purpose of this research brief is to introduce the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network (OPEN) Atlas of MedsCheck services and describe changes in the delivery of publicly funded medication review (MedsCheck) services over time in Ontario. Broader considerations across Canada for medication review services are included in the Discussion section.

Table 1.

Summary of publicly funded medication review services across Canada*

| Province/territory | Program start date | Publicly reimbursed medication review program available | All beneficiaries eligible | Medication review programs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Long-term care | Diabetes | Home | ||||

| British Columbia | 2011/04 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓* | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Alberta | 2012/07 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓* | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Saskatchewan | 2013/07 | ✓ | ✰ | ✓* | ✗ | ✗ | ✓* |

| Manitoba | n/a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Ontario | 2007/04 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓* | ✓* | ✓* | ✓ |

| Quebec | n/a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| New Brunswick | 2012/06 | ✓ | ✰ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Prince Edward Island | 2013/04 | ✓ | ✰ | ✓* | ✗ | ✓* | ✗ |

| Nova Scotia | 2008/04 | ✓ | ✰ | ✓* | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2012/09 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Yukon | n/a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Northwest Territories | n/a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Nunavut | n/a | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Follow-up service available. n/a = Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut do not currently reimburse for pharmacy medication review services with a professional service fee. A check mark indicates covered. Ontario MedsCheck long-term care service-fee code was delisted effective January 1, 2020, under a capitation model that includes medication annual and quarterly review services 21 ; thus, coverage continues yet dates are no longer identifiable. The star symbol indicates that only specific beneficiaries were covered; refer to the details given in Appendix 1. X indicates not reimbursed under the public plan.

Methods

A description of the technical methods for the development of the OPEN Atlas of Professional Pharmacy Services Tool has been previously published. 9 MedsCheck services are reimbursed on a fee-for-service model through product identification numbers submitted by pharmacies to the Ontario Drug Benefit Program. The MedsCheck Atlas includes a suite of interactive tools, 1 for each type of the 4 MedsCheck service programs: 1) the original MedsCheck Annual, 2) MedsCheck Diabetes, 3) MedsCheck Home and 4) MedsCheck Long-Term Care.8 -10 We created cohorts for each MedsCheck service based on date of first service submitted to the Ontario Drug Benefit Program, through to the end of December 2019. Patient age, sex and postal code were obtained from the Registered Persons Database. These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Patients who were missing age or sex or who had a recorded death date before the first service were excluded. In addition, pediatric patients (age <18 years) were excluded from MedsCheck Long-Term Care, because only adults are eligible residents of long-term care homes in Ontario. 11 Patients with a missing postal code were excluded from regional analyses. Duplicate claims for the same patient and service month-year were excluded. In this brief, we report the monthly number of services plotted by type of MedsCheck service and summarize descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, lower quartile, upper quartile) for age by sex. Readers are encouraged to consult the OPEN Atlas Tool for histograms with numbers of claims, histograms of age distributions by sex at the time of first service delivery and maps of standardized rates that are interactive by calendar year and region defined by the Ontario-based Local Health Integration Network system. 10

Results

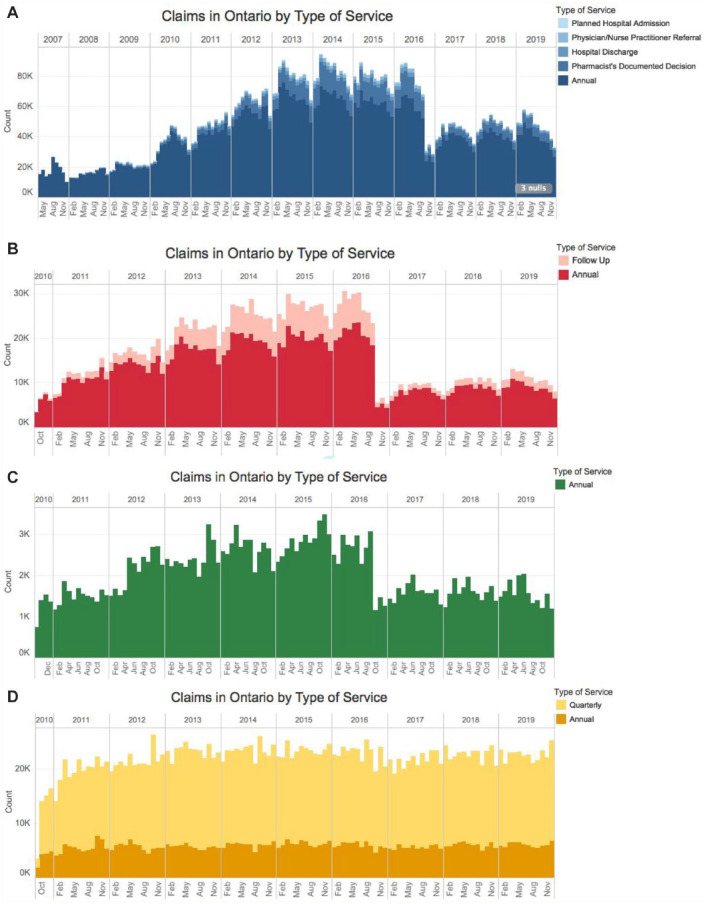

A total of 7,753,130 MedsCheck Annual services were delivered to 2,804,559 Ontarians from program launch in April 2007 through to the end of December 2019. Expansion of the medication review program in September 2010 resulted in the delivery of 1,858,805 MedsCheck Diabetes services to 704,026 patients, 229,001 MedsCheck Home services to 146,081 patients and 2,456,667 MedsCheck Long-term Care services to 281,777 residents. MedsCheck services delivered in the community pharmacy (MedsCheck Annual and MedsCheck Diabetes) and patients’ home (MedsCheck Home) demonstrated rapid initial uptake and a steady increase through to 2013, after which monthly service delivery remained relatively stable until October 2016 (Figure 1A-C). As noted previously, 8 abrupt policy changes effective October 2016 that added documentation and training requirements resulted in an immediate drop in service delivery. The Atlas Tool includes data through to the end of December 2019, providing evidence that the number of services have yet to recover to previous levels 3 years after the initial policy change in October 2016. Of interest and previously reported, 8 there was little change in MedsCheck service delivery in long-term care following the 2016 policy changes (Figure 1D). The recommendation to conduct regular medication review for all long-term care residents in Ontario, 12 combined with established infrastructure, may largely explain the consistency and resilience of MedsCheck delivery in long-term care.

Figure 1.

Monthly number of MedsCheck services (A: Annual, B: Diabetes, C: Home, D: Long-term Care) delivered in Ontario

Patients receiving MedsCheck services in community pharmacies were on average 62 years of age and shared a similar pattern of age distribution, yet they were on average younger than patients of MedsChecks delivered in the home (mean age = 74.6 years) or in a long-term care facility (mean age = 82.5 years; Table 2). The difference in age distribution was expected, given the unique eligibility criteria for MedsCheck Home and MedsCheck Long-term Care, which capture more vulnerable populations.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of age distribution by sex and type of MedsCheck service, April 2007 to September 2019*

| Service type | Sex | N | Mean | SD | Median | Lower quartile | Upper quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | Men | 1,289,592 | 61.6 | 15.7 | 64 | 53 | 73 |

| Women | 1,514,967 | 61.5 | 17.0 | 64 | 51 | 74 | |

| Diabetes | Men | 382,733 | 61.9 | 13.3 | 63 | 53 | 71 |

| Women | 321,293 | 62.2 | 14.4 | 64 | 53 | 72 | |

| Home | Men | 53,936 | 71.2 | 18.0 | 76 | 61 | 85 |

| Women | 92,145 | 76.6 | 15.1 | 81 | 70 | 87 | |

| Long-term Care | Men | 96,753 | 80.0 | 11.4 | 82 | 75 | 88 |

| Women | 185,024 | 83.8 | 10.0 | 86 | 80 | 90 |

Age was calculated based on the first service date of that type over the entire observation period. MedsCheck Annual services have been available since April 2007 and other services since September 2010.

Discussion

The OPEN Atlas of MedsCheck services includes a suite of interactive tools that enable the visualization of descriptive analyses for each publicly funded medication review pharmacy service in Ontario. The Atlas may be of particular value for understanding the uptake and planning for medication review services in Canada. Ontario was the first province in Canada to offer a publicly funded medication review program, with an expanded selection of services targeting different populations in need. In the community setting, all provinces except Quebec and Manitoba offer publicly funded medication reviews to residents meeting certain eligibility requirements, yet eligibility criteria and reimbursement schemes vary. Variation in service delivery across jurisdictions is not unique to Canada. 13 Indeed a recent call encourages pharmacies to unite at an international level to better standardize medication review services.13,14

In 2019, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) published its review of the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reviews. 15 Examining 4 systematic reviews from across the globe, CADTH reported improvements in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and blood pressure control. In addition, CADTH reviewed an economic evaluation conducted in Spain and found a net benefit to the national health system. However, it is worth noting that direct clinical evidence of medication review programs remains scarce. Studies of various quality report conflicting results.6,16 -20 Therefore, it is of high public interest to have more well-designed, rigorous studies to investigate the health outcomes and economic implications of pharmacist-led medication reviews. The data provided by the OPEN Atlas Tool, which leverages health care administrative databases and robust statistical analyses, provides a helpful basis for considering how to design future studies.

It will no longer be possible to monitor the extent of the medication review in Ontario long-term care homes, because the Ontario MedsCheck Long-term Care program was delisted effective January 1, 2020. A new fee-per-bed capitation model has been introduced in long-term care homes that replaces the old fee-for-service model. Under the fee-per-bed capitation model, medication reviews (annual and quarterly), pharmaceutical opinions and smoking cessation are included and thus can no longer be billed separately for patients who reside in long-term care. 21 Although we do not anticipate that medication reviews will cease in long-term care, we believe that an ability to track the time from entry into a long-term care facility before medication review is completed could shed some light on the quality of service delivery. Presumably, the earlier a medication review is performed, the better care a new patient is receiving. Similarly, how often regular quarterly medication reviews are completed will no longer be traceable yet is of interest as a marker of medication review service quality.

As evidenced by the OPEN Atlas, atlases of service utilization can be used to identify the susceptibility of publicly funded pharmacy services to policy change, such as the continued impact of the October 2016 changes to MedsCheck services. 8 More recently, the Ontario government declared a state of emergency on March 17, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.22 -24 Emergency measures such as physical distancing have facilitated virtual pharmacy service delivery.25 -27 Better understanding of the impact of policy changes on the number and quality of professional pharmacy services is important. Community pharmacy provides a unique opportunity to provide primary care and initiate public health initiatives such as infectious disease testing (e.g., COVID-19) and vaccination programs.28,29 The transformation of primary health care services prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic may help spearhead coordinated innovative primary health care solutions in community pharmacies. 14 The data provided by the OPEN Atlas of MedsCheck services demonstrate the widespread delivery of medication review services in Ontario that are susceptible to policy changes. Better integration of community pharmacy services into primary health care systems is encouraged. ■

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Brittany Salmon for contributing to the summary table of services across Canada.

Footnotes

Preliminary results were presented at the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network Summit in March 2019 and Pharmacy Experience Pharmacie conference in June 2019.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC, ministry grant No. 6674) and the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy. This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the MOHLTC. All analyses were completed at the ICES University of Toronto site, supported by the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the MOHLTC and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to study design, interpreting study results and critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication. SMC was responsible for project funding, administration and staff /student supervision. NH completed analyses at ICES, MC prepared analytical tables and figures and QG and ASL summarized medication review services across Canada.

Statement of Conflicting Interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Considerations: ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board. This project was conducted under section 45 and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Legal Office.

ORCID iDs: Lisa Dolovich  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0061-6783

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0061-6783

Contributor Information

Qihang Gan, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Avery S. Loi, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Maha Chaudhry, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Nancy He, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; ICES, Toronto, Ontario.

Ahmad Shakeri, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Lisa Dolovich, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; ISchool of Pharmacy, University of Waterloo, Kitchener, Ontario; Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

Suzanne M. Cadarette, From the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; ICES, Toronto, Ontario; Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors: quality chasm series. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hakkarainen KM, Sundell KA, Petzold M, Hägg S. Prevalence and perceived preventability of self-reported adverse drug events: a population-based survey of 7099 adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73166.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in the elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sichieri K, Rodrigues ARB, Takahashi JA, et al. Mortality associated with the use of inappropriate drugs according Beers criteria: a systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Pharm. 2013;1(2):74-84. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zed PJ, Haughn C, Black KJL, et al. Medication-related emergency department visits and hospital admissions in pediatric patients: a qualitative systematic review. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):477-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huiskes VJB, Burger DM, van den Ende CHM, van den Bemt BJF. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pammett R, Jorgenson D. Eligibility requirements for community pharmacy medication review services in Canada. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2014;147(1):20-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shakeri A, Dolovich L, MacCallum L, Gamble JM, Zhou L, Cadarette SM. Impact of the 2016 policy change on the delivery of MedsCheck services in Ontario: an interrupted time-series analysis. Pharmacy. 2019;7(3):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cadarette SM, He N, Chaudhry M, Dolovich L. The Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network interactive atlas of professional pharmacy services. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2021;154:153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. OPEN. Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network Interactive Atlas Tool. Available: https://www.pharmacy.utoronto.ca/research/centres-initiatives/centre-practice-excellence/open-interactive-atlas-professional-pharmacist-services (accessed Feb. 15, 2021)

- 11. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Long-term care overview. Published November 2019. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/page/about-long-term-care (accessed Aug. 15, 2020).

- 12. Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. Professional pharmacy services guidebook 3.0. Toronto (Ontario): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2016. Available: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/medscheck/docs/guidebook.pdf (accessed Oct. 1, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rose O, Cheong V-L, Dhaliwall S, et al. Standards in medication review: an international perspective. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2020;153(4):215-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raiche T, Pammett R, Dattani S, et al. Community pharmacists’ evolving role in Canadian primary health care: a vision of harmonization in a patchwork system. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(4):2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shane A, Argáez C. Pharmacist-led medication reviews: a review of clinical utility and cost-effectiveness. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 09062019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kolhatkar A, Cheng L, Chan FKI, Harrison M, Law MR. The impact of medication reviews by community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(5):513-20.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Currie K, Evans C, Mansell K, Perepelkin J, Jorgenson D. Community pharmacists’ experiences with the Saskatchewan Medication Assessment Program. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2019;152(3):193-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jokanovic N, Tan ECK, Sudhakaran S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: an overview of systematic reviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):661-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Messerli M, Blozik E, Vriends N, Hersberger KE. Impact of a community pharmacist-led medication review on medicines use in patients on polypharmacy—a prospective randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lapointe-Shaw L, Bell CM, Austin PC, et al. Community pharmacy medication review, death and re-admission after hospital discharge: a propensity score-matched cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(1):41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ministry of Health. Notice: policy for pharmacy payments under the long-term care home capitation funding model, 2020. Toronto (Canada): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2020:13. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/opdp_eo/notices/exec_office_20191216_2.pdf (accessed Sep. 17, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Statement from Premier Ford, Minister Elliott, and Minister Lecce on the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Office of the Premier. Published March 12, 2020. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/56270/title (accessed Sep. 17, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ontario enacts declaration of emergency to protect the public. Office of the Premier. Published March 17, 2020. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56356/ontario-enacts-declaration-of-emergency-to-protect-the-public (accessed Sep. 17, 2020).

- 24. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Ontario extends emergency orders to help stop the spread of COVID-19. Office of the Premier. Published April 23, 2020. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56746/ontario-extends-emergency-orders-to-help-stop-the-spread-of-covid-19 (accessed Sep. 17, 2020).

- 25. Ontario Pharmacists Association. COVID-19 pandemic: a pharmacist’s guide to pandemic preparedness. 2020:23. Available: https://www.opatoday.com/Media/Default/Default/2020-03-17%20OPA%20GUIDE%20FOR%20PANDEMIC%20PREPAREDNESS_FINAL.pdf (accessed Sep. 17, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health. Notice: Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) program changes and guidance for dispensers during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Published March 20, 2020. Available: https://www.ona.org/wp-content/uploads/covid19_odbprogramchangesandguidancefordispensers_20200320.pdf (accessed Sep. 17, 2020).

- 27. Ministry of Health. Executive officer notice: removal of the 30-days’ supply dispensing limit recommendation. Published June 12, 2020. Available: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/opdp_eo/notices/exec_office_20200612.pdf

- 28. Chaudhry M, He N, Waite NM, Houle SKD, Kwong JC, Cadarette SM. The Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network Atlas of community pharmacy influenza immunization services. Can Pharm J. 2021;154(5):305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poudel A, Lau ETL, Deldot M, Campbell C, Waite NM, Nissen LM. Pharmacist role in vaccination: evidence and challenges. Vaccine. 2019;37(40):5939-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]