Abstract

This mini-review, mainly based on our resonance Raman studies on the structural origin of cooperative O2 binding in human adult hemoglobin (HbA), aims to answering why HbA is a tetramer consisting of two α and two β subunits. Here, we focus on the Fe-His bond, the sole coordination bond connecting heme to a globin. The Fe-His stretching frequencies reflect the O2 affinity and also the magnitude of strain imposed through globin by inter-subunit interactions, which is the origin of cooperativity. Cooperativity was first explained by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux, referred to as the MWC theory, but later explained by the two tertiary states (TTS) theory. Here, we related the higher-order structures of globin observed mainly by vibrational spectroscopy to the MWC theory. It became clear from the recent spectroscopic studies, X-ray crystallographic analysis, and mutagenesis experiments that the Fe-His bonds exhibit different roles between the α and β subunits. The absence of the Fe-His bond in the α subunit in some mutant and artificial Hbs inhibits T to R quaternary structural change upon O2 binding. However, its absence from the β subunit in mutant and artificial Hbs simply enhances the O2 affinity of the α subunit. Accordingly, the inter-subunit interactions between α and β subunits are nonsymmetric but substantial for HbA to perform cooperative O2 binding.

Keywords: Resonance Raman, Iron-histidine bond, Hemoglobin, Cooperativity, Quaternary structure, Subunits

Introduction

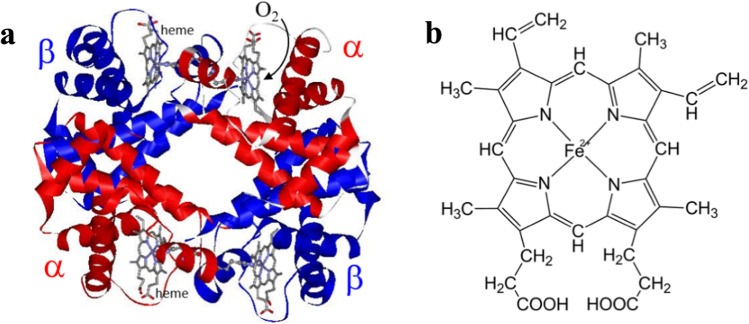

Human adult hemoglobin (HbA) is a blood protein that transports O2 from the lungs to different tissues of the body. The HbA molecule is a tetramer consisting of two α and two β subunits (Fig. 1a). Each subunit contains a heme (Fe-protoporphyrin IX complex, Fig. 1b), which is bound to the Nε2 of a histidine (His) residue of globin, called the proximal His. Therefore, the Fe-His bond is the sole coordination bond that connects heme to globin. O2 is bound to the trans site of proximal His and forms a hydrogen bond (H-bond) with distal His. Several previous studies have focused on HbA, including the Bohr effect (Bohr et al. 1904), Hill plot analysis (Hill 1913), determination of four-step O2 binding (or Adair) constants (Adair 1925), and successful X-ray crystallographic analysis by Perutz et al. (1960). Based on a detailed X-ray analysis, Perutz pointed out the presence of two quaternary structures: those of deoxyHb (fully deoxygenated form) and oxyHb (four O2-bound form) (Perutz 1970, 1979), in both of which the (α1β1) dimer is moved to (α2β2) by the twofold symmetry axis. The experimental O2 binding curves obtained under various conditions (Imai 1982) were fully explained by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux, referred to as the MWC theory. It postulates the presence of two states, and the transition between a low- (T) and a high-affinity state (R) is the origin of cooperative O2 binding (Monod et al. 1965). Perutz proposed that these two states correspond to the quaternary structures of deoxyHb (T) and oxyHb (R) (Perutz 1970, 1979). Perutz’s idea, combined with MWC theory, was mathematically supported (Szabo and Karplus 1972) and has been referred to as the MWC scheme. In addition, different theories based on successive O2 binding to each subunit are referred to as the KNF model (Koshland et al. 1966) and a model of a dimer of (αβ) dimers (Ackers and Holt 2006, Ackers et al. 1997; Ackers 1998; Johnson and Ackers 1982). In Acker’s model, eight partially ligated intermediates (n = 1, 2, 3) were considered. From the analysis of the binding energies of intermediates, for instance, in n = 2, cooperativity occurs when the second O2 binds to the same dimer to which the first O2 bound. However, cooperativity does not occur in the other three intermediates where O2 binds to both αβ dimers. Thus, the model emphasizes the contribution of intra-dimers to cooperativity, though it is reported that Acker’s model is invalid from studies using Ni–Fe (XL[α(Fe2+)β(Ni)]2, XL[α(Ni)β(Fe2+)]2, XL[α(Fe2+)β(Ni)][α(Ni)β(Fe2+)], XL[α(Fe2+)β(Fe2+)][α(Ni)β(Ni)]: XL means cross-linked between Kβ81 and Kβ82) and valency hybrid Hb (α(Fe3+-CN)β(Fe3+-CN)][α(Fe2+)β(Fe2+)]) (Shibayama et al. 1995; 1997; 1998). The MWC model cannot explain the heterotropic allosteric effectors (pH and organic phosphates, such as inositol hexakisphosphate (IHP) and bezafibrate (BZF)). To overcome the defect, Eaton’s group (Henry et al. 2002) proposed the two tertiary states (TTS) theory, assuming that the tertiary structures of globins (represented by t and r) determine the O2 affinity, where t and r correspond to the tertiary structures of each globin with low- and high-O2 affinity.

Fig. 1.

a Molecular structure of human adult hemoglobin (HbA); red, α subunit; blue, β subunit from 2DN2 (Park et al. 2006). b The molecular structure of heme (Fe-protoporphyrin IX complex)

Moreover, experimentally, several new features which are difficult to interpret with the MWC scheme have been accumulated. Sol–gel experiments by Shibayama and Saigo (2001) demonstrated the presence of two affinity states in the quaternary T structure. Comprehensive structural studies on ligand binding to Hb by Ho’s group using NMR spectroscopy (Yuan et al. 2015) stressed the importance of the tertiary structure in O2 affinity. Yonetani et al. (2002) found that the cooperativity in O2 binding is completely lost and the O2 affinity is lowered more than that in the normal T state due to the presence of allosteric effectors such as 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (BPG), IHP, and BZF, but the quaternary structure was changed by CO (as mimic of O2) binding (Nagatomo et al. 2005). To explain these results, a global allostery model was proposed (Yonetani and Laberge 2008; Yonetani and Kanaori 2013) in which large-amplitude segmental motions of the E and F helices determine O2 affinity. The presence of such segmental motion has not yet been spectroscopically confirmed in the GHz and THz frequency regions.

Allosteric effects are fundamental subjects of general proteins to be explored on the basis of structures. HbA is a typical molecule which exhibits the allosteric effects on the O2 binding. The structures of HbA including intermediates in the O2 binding have been investigated with various techniques. Accordingly, many models explaining a mechanism of allosteric effects have been reported as described above. However, none of them explicitly distinguishes the role of the α from that of β subunits in the tetramer, though their properties are almost alike in separated states and, to the best of our knowledge, do not explain why HbA must consist of α and β subunits. Therefore, in this report, we attempt to answer this question by focusing on the structures of intermediately ligand-bound states and the communication pathways between the α and β subunits, which are different depending on the direction in transmitting the information of O2 binding of a heme to subunit interfaces through tertiary structure changes. About the α subunit, Perutz indicated that oxygen binding to the α subunit is a trigger of quaternary structural changes (Perutz1970). Paoli et al. showed a rupture of Fe-His of the α subunit (not the β subunit) maintained T structure in the full ligand bindings (α(Fe3+-CN)β(Fe3+-CN)) and prevented quaternary structural change to R structure (Paoli et al. 1997).

In the following sections, the protein structures of CO-bound HbA (COHb) and oxyHb are considered identical, and the quaternary structures of deoxyHb and oxyHb are denoted as the T and R structures, respectively. Tertiary structures of globins corresponding to the low- and high-affinity states are represented by t and r, respectively. The low- and high-affinity states of MWC theory (Monod et al. 1965) are conveniently represented as the T and R states, respectively. Only when two α subunits are distinguished, they will be denoted as α1 and α2, and this is the same for β subunits. The angle taken by the α1β1 and α2β2 heterodimers in the α2β2 tetramer changes by 15° upon ligand binding, that is, upon the T–R transition (Perutz 1970, 1979); thus, the α1–β2 contact (same as α2–β1 contact) is changed by it.

Globin properties

The α and β subunits of HbA consist of 141 and 146 residues, respectively, and exhibit a residue homology of approximately 46%. When the tetramer was separated, the isolated α and β chains were in equilibrium with α2 and β4 oligomers, respectively, both of which exhibited no cooperative O2 binding (Imai 1982; Tyuma et al. 1971). The separated chains have a higher O2 affinity than HbA and are not influenced by allosteric effectors, such as BPG and IHP (Imai 1982; Tyuma et al. 1971). The α and β chains are composed of seven and eight α helices, respectively, named the A-H helix from the N-terminus. Therefore, the H helix is closest to the C-terminus. The largest difference between the two subunits was the lack of a D helix in the α subunit. The structural parameters of the α and β subunits in the tetramer are summarized in Table 1 and are discussed in detail later.

Table 1.

Structural parameters of the α and β subunits

| α1 | α2 | β1 | β2 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of amino acid residues | 141* | 146* | (Perutz 1970) | ||

| Number of α-helices | 7 | 8 | (Perutz 1970) | ||

| Fe-His bond distance in deoxyHbA/Å | 2.20 | 2.21 | 2.16 | 2.19 | (Park et al. 2006) |

| Fe-His bond distance in oxyHbA/Å | 2.07 | 2.06 | (Park et al. 2006) | ||

| H-bond distance from Nε2 of His H7/Å | (Park et al. 2006) | ||||

| O1, | 2.82 | 3.06 | |||

| O2: | 2.70 | 3.02 | |||

| Fe–O-O angle (°) | 124 | 126 | (Park et al. 2006) | ||

| Fe-His stretching frequency in deoxyHb/cm−1 | (Nagai and Kitagawa 1980) | ||||

| T-state | 203–207 | 217–220 | |||

| R-state | 222–223 | 224 | |||

| O2 binding kinetic constant, k’on/μM−1 s−1 | (Unzai et al. 1998) | ||||

| T-state | 11 | 4.0–5.8 | |||

| R-state | 36–40 | 77–80 | |||

| O2 dissociation kinetic constant, koff/s−1 | (Unzai et al. 1998) | ||||

| T-state | 4300–5200 | 1300–2100 | |||

| R-state | 12–14 | 25–31 | |||

| K = koff/k’on | (Unzai et al. 1998) | ||||

| T-state | 0.0021–0.0026 | 0.0019–0.0045 | |||

| R-state | 2.9–3.0 | 2.6–3.1 | |||

| Effect of O2-binding on quaternary structure | Large | Small | (Nagatomo et al 2011a) | ||

| Role of Fe-His bond in O2-affinity control | Essential to T → R structure change | Lowering of affinity of α subunit | (Nagatomo et al. 2015) | ||

* When the number is present between α1 and α2 columns or between β1 and β2 columns, it means that α1 and α2 (or β1 and β2) cannot be distinguishable. When two numbers are combined with a hyphen, a precise number cannot be determined but is located between the two numbers

The α and β differences in the globin responses upon O2 binding

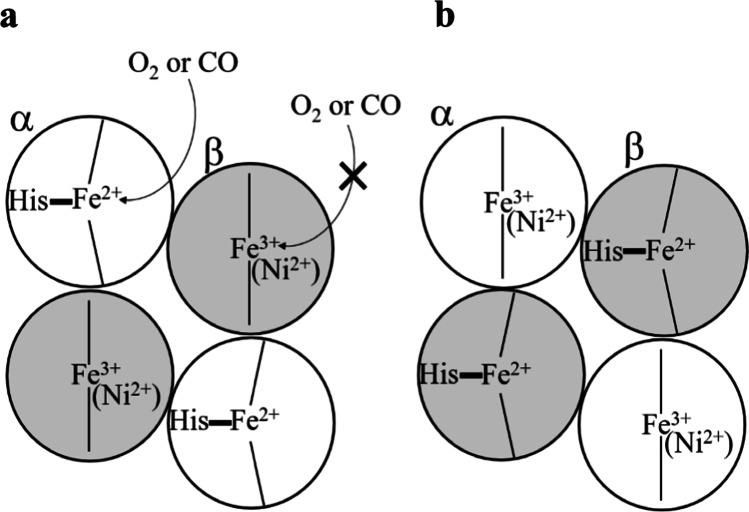

The O2 affinity differences between the α and β subunits in the α2β2 tetramer were investigated using several types of hybrid Hbs, as illustrated in Fig. 2, in which O2 could be bound to only the α (Fig. 2a) or β subunit (Fig. 2b). The former type includes natural valency hybrid Hbs, HbM Hyde Park (βH92Y), HbM Saskatoon (βH63Y), HbM Milwaukee (βV67E), with Fe3+ heme in the β subunit, and an artificial Ni-hybrid Hb α(Fe2+)β(Ni2+) (Nagatomo et al. 2002a), with Ni-coordinated heme in the β subunit, as well as a cavity mutant Hb, rHb(βH92G), with no proximal His (Nagatomo et al. 2015). Conversely, the latter includes natural mutant Hb such as HbM Iwate (αH87Y) and HbM Boston (αH58Y), with Fe3+ heme in the α subunit an artificial Ni-hybrid Hb, α(Ni2+)β(Fe2+) (Nagatomo et al 2002a) with Ni2+-heme in the α subunit, and a cavity mutant Hb, rHb(αH87G) with no proximal His in the α subunit (Nagatomo et al. 2015). In the cavity mutant Hb, which was first prepared by Ho’s group (Barrick et al. 2001), the proximal His is replaced by glycine (Gly) in the presence of imidazole (Im). Thus, the Fe-His bonds in the corresponding subunits are substituted by Fe-Im bonds without a covalent linkage between the heme and the F helix. Therefore, the strain in the Fe-His bond imposed by the quaternary structure change, assumed in the Perutz model (Perutz 1979), ceases to exist in the mutated subunit.

Fig. 2.

Illustrative diagram of hybrid Hbs. The circle denotes the α (no color) or β (gray) subunits, comprising Fe (or Ni) heme, with Fe presence coordinated by the His residue of a protein. a α(Fe2+)β(Fe3+: M2+) An O2 or CO molecule can bind to the Fe2+ heme of the α subunit. b α(Fe3+: M2+)β(Fe2+) An O2 or CO molecule can bind to the Fe2+ heme of the β subunit (M represents a metal like Ni)

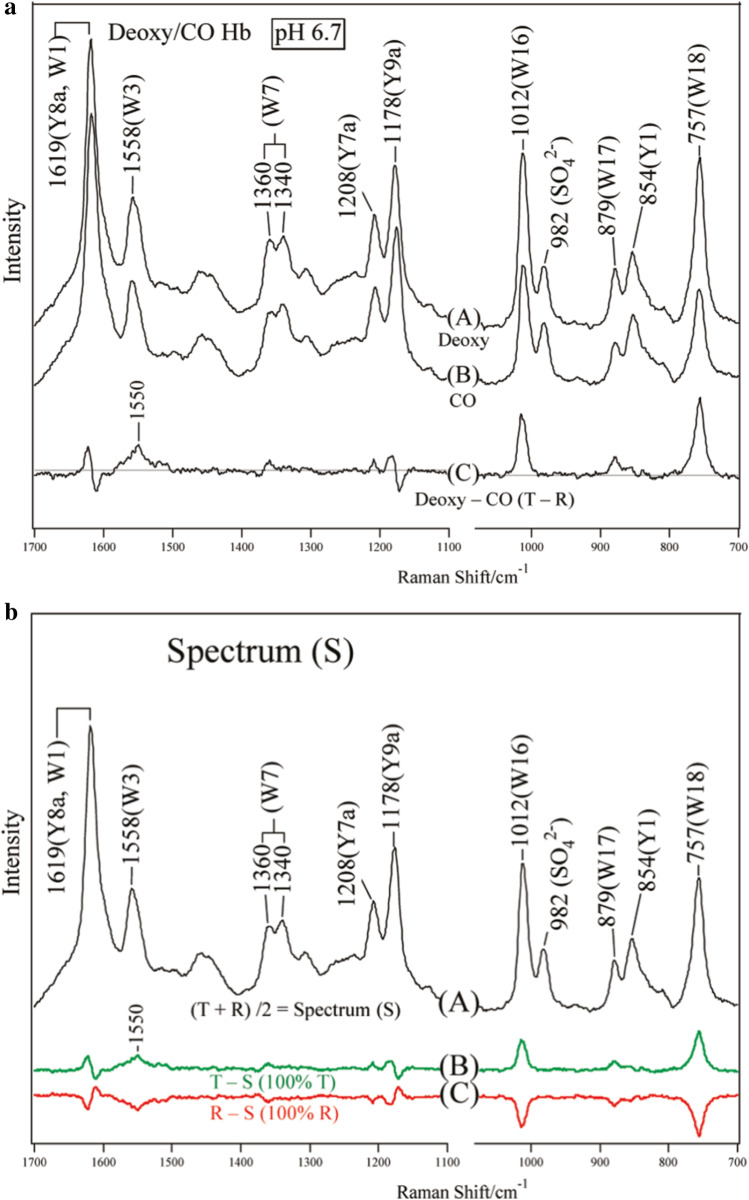

We investigated the changes in the quaternary structure upon ligand binding using UV-resonance Raman (UVRR) spectroscopy (Nagatomo et al. 2011a), in which, only the vibrations of the aromatic residues were selectively intensity-enhanced. Because the frequencies and intensities of certain bands are sensitive to H-bonding, we focused on changes in inter-subunit H-bonds upon ligand binding. Figure 3a shows the UVRR spectra of deoxyHbA (A) and COHbA (B) excited at 235 nm and their difference (C) [= (A) − (B)]. Raman bands arising from tryptophan (Trp) and tyrosine (Tyr) residues are marked by W and Y, respectively, followed by the mode numbers determined separately (Harada and Takeuchi 1986). Both samples contained a determined amount of sodium sulfate, and the 982 cm−1 band of SO42− served as an intensity standard. The difference spectrum (C) was calculated to yield the zero intensity of the 982 cm−1 band. It is evident that the W3, W17, and W18 bands are more intense in the T state, presumably because of a shift of the Bb absorption band of Trp to a longer wavelength, which is closer to the excitation wavelength, while their frequencies are unaltered. The Y8a and Y9a bands of Tyr shifted to higher frequencies in the T state.

Fig. 3.

a UVRR spectra of deoxyHbA (A) and COHbA (B) at pH 6.7 excited at 235 nm and their difference (C) [= (A) − (B)]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Nagatomo et al. (2011a), Fig. 2. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society. b Newly defined spectrum (S), which is the average of the spectra of deoxyHbA and COHbA. It shows spectrum (A). The digitally obtained difference spectra of the deoxyHbA-spectrum (S) and COHbA-spectrum (S) are delineated by traces (B) and (C), respectively, which indicate the states of the 100%T and 100%R in the difference spectra. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Nagatomo et al. (2011a), Fig. 6. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society

Through mutation experiments on each Trp and Tyr residue of HbA, the Raman bands of Trp and Tyr giving rise to the different peaks were assigned to a specific residue and their frequencies indicated whether they were H-bonding or not (Nagatomo et al. 2011a; b). It became evident that the observed UVRR bands mainly arose from Trpβ37, Tyrα140, Tyrα42, and Tyrβ145. Therefore, UVRR spectral changes were attributed to changes in the subunit contacts of Trpβ37-Aspα94 and Tyrα42-Aspβ99, as indicated by X-ray crystallography (Perutz 1979). Similar UVRR spectral differences between the T and R states have also been observed by Spiro’s group, who determined UVRR spectral changes together with UV absorption changes in a time-resolved manner (Balakrishnan et al. 2004).

To prepare for further analysis, a standard spectrum (S) is newly defined here as an average of the T and R spectra of Fig. 3b; that is, spectrum (S) = (spectrum A + spectrum B) of Fig. 3a/2 (Nagatomo et al, 2011a). We show the spectrum S in Fig. 3b. Then, the difference spectra, (B) of Fig. 3b and (C) of Fig. 3b, indicate the difference spectra, [(100% T) − (S)] and [(100% R) − (S)], respectively. In the case of Trp bands, positive and negative peaks appear in the former and latter difference spectra, respectively, the peak intensities of which correspond to the cases of the 100% T structure and the 100% R structure, respectively. Since the base line indicates the 50% T (or 50% R) structure, the half intensities denote 75% T structure in the positive peaks and 75% R structure in the negative peaks, respectively. In the case of Tyr bands, since the difference peaks of spectrum C in Fig. 3a are of differential type, their appearances in this difference calculation are complicated but the same principle as the case of Trp bands is applied. On the basis of the shapes and signs of Trp and Tyr difference peaks, we can deduce whether Trp and Tyr are strongly H-bonded (T), weakly H-bonded, or no H-bonded (R).

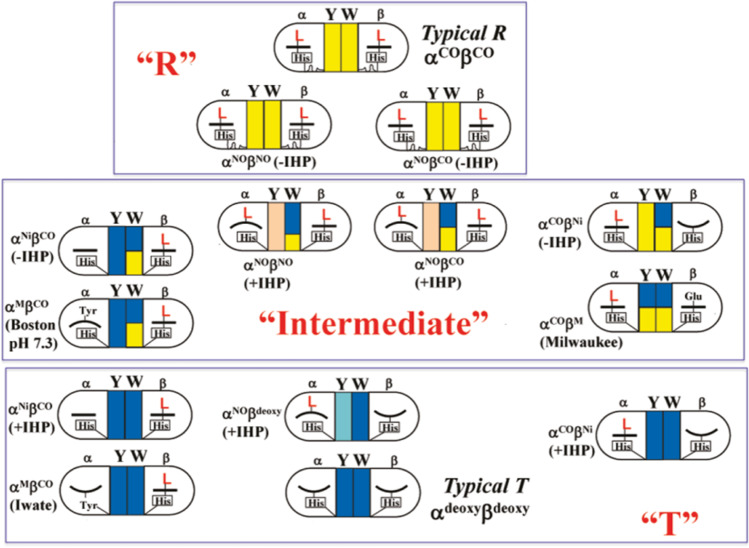

The UVRR spectra were observed for the deoxy-, CO-, and partially ligand-bound forms of the hybrid Hbs in the presence of the same amounts of sodium sulfates as used for the measurements of spectra of Fig. 3a. The spectra observed for the individual states normalized with the reference band of sulfates at 982 cm−1, were subjected to calculations of the difference spectrum with regard to the spectrum S and the results were compared with the results from HbA. The comparisons are practically depicted in Figs. 7 and 8 of the original paper (Nagatomo et al. 2011a). Thus, the amounts of T and R contacts of Trp and Tyr were estimated from the intensities of difference spectra with the peaks of Trp and Tyr bands separately. In other words, amounts of T (or R) structures were determined with the numbers of H-bonded (or no H-bonded) Trp and Tyr residues; that is, by whether Trpβ37, Tyrα140, and Tyrα42 are H-bonded (Nagatomo et al. 1999, 2002a, b, 2011b, 2015). The results are summarized in Fig. 4, where an Hb molecule is represented by a single ellipse, and Trp (W) and Tyr (Y) residues of the α and β subunits are shown on the left and right sides of the subunit centers, respectively, and colors denote whether H-bonds are formed (blue) or not (yellow). In the case of the R structure, both W and Y are highlighted with non-formed H-bonds (yellow). In contrast, in the T structure, H-bonds were formed around W and Y (blue). Dilute colors are used when the intensities of the difference peaks are weak but appreciable.

Fig. 7.

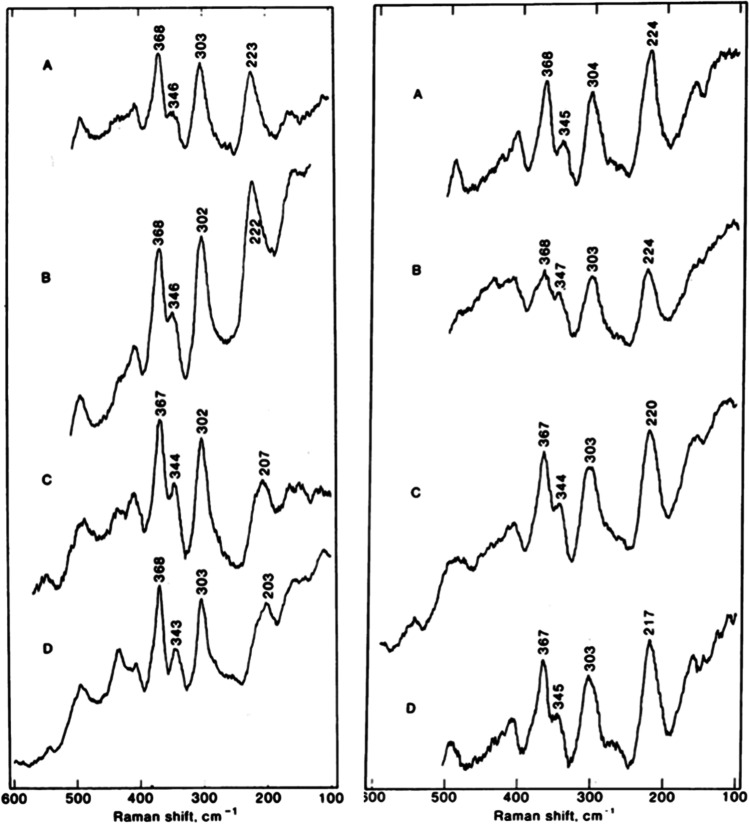

Raman spectra, A~D, of the α(Fe2+) (left panel) and β(Fe2+) (right panel) subunits. In both, the spectra, A, at the top were observed for isolated chains. The second spectra, B, were observed for valency hybrid tetramers, the α(Fe2+)β(Fe3+) (left panel) and α(Fe3+)β(Fe2+) (right panel) placed in the R state. The third spectra, C, were observed for the α(Fe2+)β(Fe3+) (left panel) and α(Fe3+)β(Fe2+) (right panel) placed in the T state. The spectra, D, at the bottom were observed for the deoxyHbM Milwaukee at pH 6.5 (left panel) and deoxyHbM Boston at pH 6.5 (right panel).

Source: Nagai K, Kitagawa T, 1980

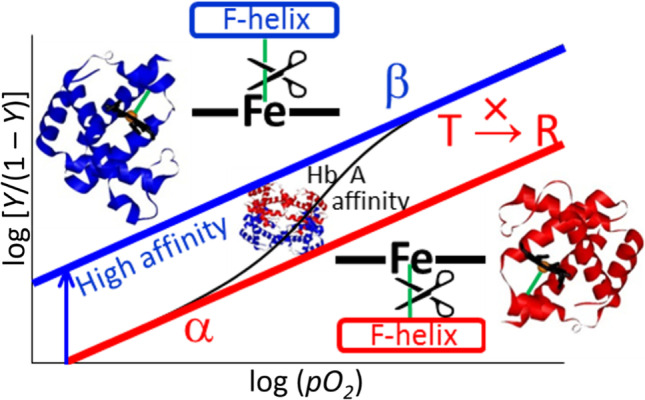

Fig. 8.

O2 binding equilibrium curves of HbA and structures of individual subunits in the tetramer. The cleavage of the Fe-His bond of the β subunit increases the affinity of the α subunit but, in contrast, that of the α subunit does not increase the affinity of the β subunit and does not induce a quaternary structure change (T → R)

Fig. 4.

Illustrative representation of Hb quaternary structures in various liganded states. The left and right half-circles symbolically represent the α1 and β2 subunits, respectively, and the two squares between them indicate the Tyr (Y) and Trp (W) residues at the subunit contact region. The squares in blue and yellow indicate the T- and R-contacts respectively, and their areas are proportional to the relative numbers with T and R contact. Light blue and pink indicate the nearly T- and R-contacts, respectively. L denotes CO molecules. His in a rectangle denotes the proximal (F8) histidine. The heme shape is represented by a bar (planar) or bowl (domed), and the Fe-His bond is represented, if present, by a short line between the heme and His. The solid lines and waved lines under the His indicate the constrained or relaxed states of the Fe-His bond, respectively. These Hbs could be categorized into “T,” “intermediate,” and “R” structure based on the color distribution of the contact region. When the colors of both Y and W are blue and yellow, the corresponding Hbs are categorized as “T” and “R,” respectively. Hbs with mixed colors are designated into an “intermediate” group. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Nagatomo et al. (2011a), Fig. 10. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society

Figure 4 clearly shows that the structures of certain Hb molecules are classified as typical T or R from the H-bonding states at the subunit interface. Furthermore, Fig. 4 shows that (1) CO binding only to the α subunit could generate the R structure (intermediate, T, right side), and (2) CO binding only to the β subunit could not generate the full R structure (intermediate, T, left side). This conclusion comes from the fact that CO binding to the α subunit changed all the Trpβ37, Tyrα140, and Tyrα42 spectra while that CO binding to the β subunit changed only the Trpβ37 spectrum. These differences likely reflect different effects on the distal side. In other words, structural changes in the β subunit induced by CO binding to the α subunit were different from those in the β subunit induced by CO binding to the β subunit. This is one reason why an α-β combination is required for cooperativity.

Communications between the α and β subunits

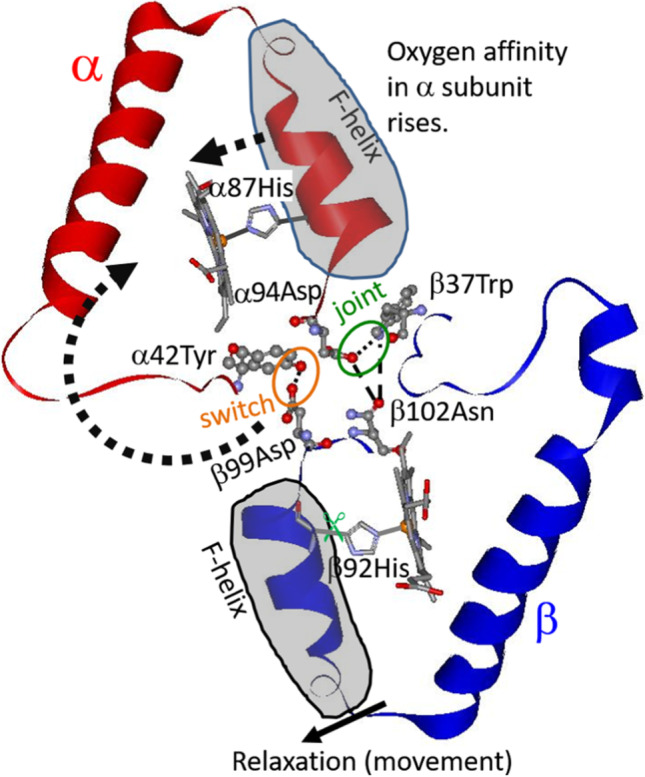

The cooperative O2 binding of Hb arises from structural communication among the four subunits, which results in four different binding constants for four O2 molecules, which served as the basis for the KNF theory (Koshland et al. 1966). X-ray crystallographic analysis has already pointed out that H-bonds are formed between Tyrα42 and Aspβ99 just as well as between Aspα94 and Trpβ37 in deoxyHb, but are broken in oxyHb at both ends of the successive O2 binding (Perutz 1979). Based on this, we deduced that O2 binding to the α subunit of deoxyHb in the T state destroys the H-bond between Aspα94 and Trpβ37 without a change in Asnβ102, and it also breaks the H-bond between Valα93 and Tyrα140 within the α subunit. Therefore, it changes to an R quaternary structure (Nagatomo et al. 2002a; 2011a: 2015). However, O2 binding to the β subunit of deoxyHb in the T state causes Asnβ102 to form H-bonds with Aspα94 and Trpβ37 and to break the H-bond between Aspα94 and Trpβ37. Meanwhile, the H-bond between Valβ98 and Tyrβ145 within the β subunit is maintained and does not induce a quaternary structural change to R (Nagatomo et al. 2017a). However, at pH values above 8, the H-bond between Aspβ94 and Hisβ146 ceases to exist, and the F helix of the β subunit moves more easily (Nagatomo et al. 2017a). The H-bond between Valβ98 and Tyrβ145 breaks. The Tyr UVRR spectral changes observed for HbM Boston and HbM Iwate at higher pH (Nagatomo et al. 2017a) could be attributed to this structural change.

Before these studies, three possible pathways for transmission of the information of the O2 binding of the α subunit to the heme in the β subunit were proposed from comprehensive NMR studies (Ho 1992). O2 binding to heme first induces movement of Hisα87, followed by:

A conformational change of Valα93 is transmitted to Argβ40 through a change in Argα92. This change is returned to Tyr α42, then to Aspβ99. Finally, it is transmitted to heme through Valβ98.

A conformational change of Valα93 breaks the intra-subunit H-bond between Valα93 and Tyrα140, which is transmitted to Trpβ37, then to Thrβ38, Gluβ39, and Argβ40. Subsequently, the signal is transmitted to the heme in β subunit in the next step.

A conformational change until Tyrα42 occurs in the same path as (1), and a conformational change in Tyrα42 is transmitted to Thrα41. It is then transmitted to Tyrβ145, adjacent to Thrα41. A conformational change in Tyrβ145 is associated with Valβ98 through the intra-subunit H-bond between Valβ98 and Tyrβ145. Finally, it is communicated to heme through Valβ98.

We agree with this mechanism for these β subunits. However, regarding the β-to-α subunit transmission, we proposed another pathway passing through Asnβ102, as mentioned above, although Ho (1992) proposed inverse pathways for the β-to-α subunit transmission. This difference is presumably induced by the differences in the magnitudes of the strain imposed on the Fe-His bond, which is stronger in the α subunit than in the β subunit.

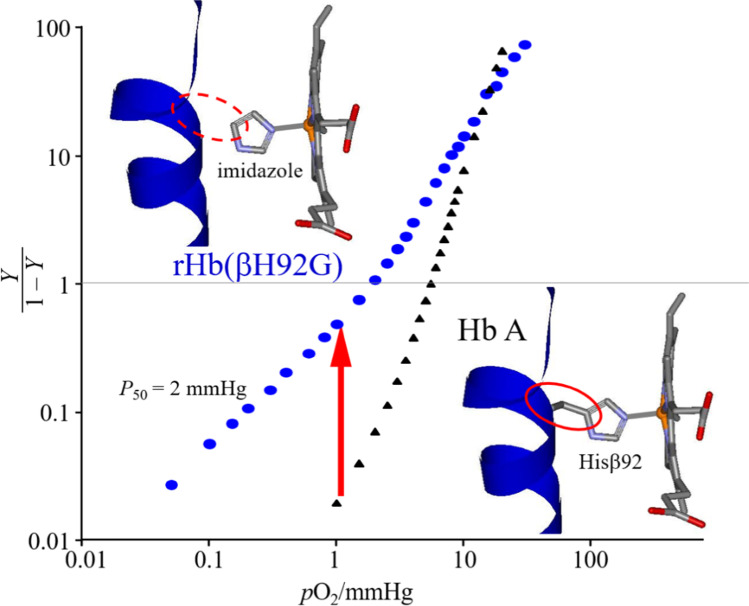

The O2 affinities of the α and β subunits in the α2β2 tetramer were determined independently using valency- and metal-hybrid Hbs. Their affinities were the same as those of deoxyHb (Unzai et al. 1998). In general, the affinity changes of both the α and β subunits are accompanied by a quaternary structural change in the presence of the Fe-His bond. However, in its absence, it is also possible to achieve high affinity within the T quaternary structure in the case of the α subunit (Nagatomo et al. 2017b). In the case of rHb(αH87G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the α subunit, the affinity of the normal β subunit is similar to that of deoxyHb (P50 ~ 60 mmHg), but the affinity of the normal α subunit of rHb(βH92G) is raised to a level of the R state (P50 ~ 2 mmHg) (Fig. 5) (Nagatomo et al. 2015) in maintaining the T quaternary structure. Here, P50 is defined as the oxygen pressure when 50% heme is oxygenated in all hemes of hemoglobin. Therefore, P50 was used as the standard for oxygen affinity. When P50 is large and small, the oxygen affinities are low and high, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Oxygen equilibrium curves of human adult hemoglobin (HbA) (black) and cavity mutant Hb, rHb(βH92G) (blue). The insertions illustrate the relation between the F helix and F8 histidine.

Source: Nagatomo et al. 2015. Molecular structure of HbA is from 2DN2 (Park et al. 2006) and that of rHb(βH92G) is shown by modification from 2DN2 (Park et al. 2006)

Therefore, rHb(βH92G) serves as an example of an inconsistency between the affinity and quaternary structure. It is likely that the local tertiary structure around the heme changes from t to r because of the absence of covalent bonds between the F-helix and Hisβ92 being present in the normal case. The possible local tertiary structure will be discussed later in “The α and β differences in the crystallographic structures.” We consider that the absence of covalent bonds between the F-helix and imidazole in rHb(βH92G) has the same effect as cleavage of the Fe-His bond. A similar phenomenon, in which the O2 affinity of the α subunit becomes high in the T quaternary structure, was also found in a natural mutant HbM with an abnormal chain in the β subunit (Nagatomo et al. 2017b). This suggests that the relaxation of the F tension (interpreted in “The α and β difference in the roles for performing cooperativity”) in the β subunit is transmitted to the α subunit with no change in a quaternary structure as illustrated in Fig. 6. Thus, F tension is a force which heme-Fe in β subunit affects F helix in β subunit. Therefore, when Fe-His in β subunit cleaves or is replaced by Fe-Tyr such as Hb M Hyde Park (βHis92 → Tyr), F helix in β subunit moves to the minimum point of conformational energy of β globin as shown in Fig. 6. In contrast to HbM, which has an abnormal chain in the α subunit, the O2 affinity remained low (P50 ~ 25–50 mmHg), similar to the T quaternary structure (Nagatomo et al. 2002b).

Fig. 6.

Amino acid residues potentially involved when the relaxation of the F helix of the β subunit is communicated to the α subunit. This pathway was deduced with ultraviolet resonance Raman spectroscopy (UVRR)

The α and β differences in the strain imposed to the Fe-His bond

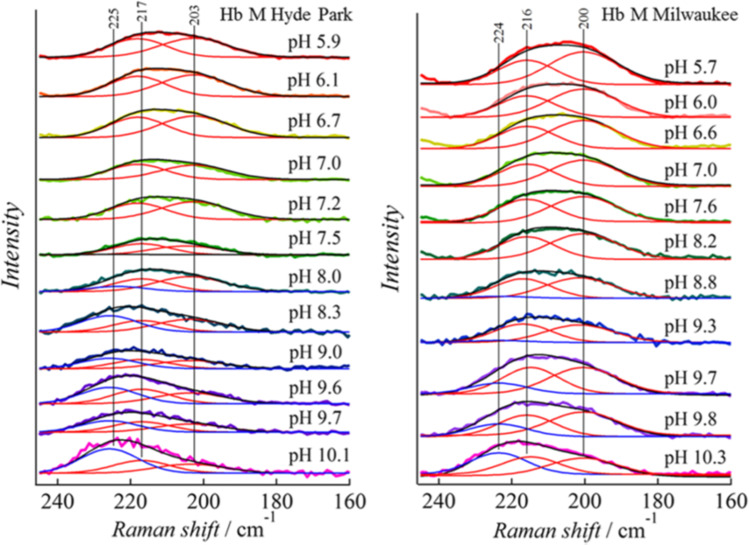

The Fe-His stretching mode of deoxyHb at 215 cm−1 was assigned with the isotope substitution of heme Fe (Kitagawa et al. 1979; Kitagawa and Nagai 1982) and has been considered to reflect the magnitude of the strain imposed on the Fe-His bond (Nagai et al. 1980b) on the basis of Perutz’s strain model (Perutz 1979). This band seems to reflect the O2 affinity of HbA; the higher the frequency, the higher the affinity (Matsukawa et al. 1985). Therefore, it appears to be closely related to the states of the MWC theory (Monod et al. 1965). However, it became clear that the frequency is different between the α and β subunits (Nagai and Kitagawa 1980): 222–223 cm−1 and 224 cm−1 for the α and β subunits, respectively, in the R structure [Fig. 7(A) and (B) in both panels], but 203–207 cm−1 for the α subunit [(C) and (D) in the left panel] and 217–220 cm−1 for β subunit [(C) and (D) in the right panel] in the T structure, as demonstrated in Fig. 7. From this observation, the magnitude of the strain was deduced to be three times larger in the α subunit than in the β subunit (Kitagawa 1988). In a recent application to TTS theory, the Fe-His stretching frequency is considered to reflect tertiary structures (Jones et al. 2012); its frequency is lower in the t structure than in the r structure. In practice, in typical cases, the t and r structures are dominant in the T and R structures, respectively.

Yonetani et al. (2002) demonstrated that the R structure does not always indicate high O2 affinity in the presence of allosteric effectors, such as IHP and BZF. Therefore, Nagatomo et al. (2017b) examined the relationship between O2 affinity and Fe-His stretching frequencies with valency hybrid HbM (αFe2+βFe3+, αFe3+βFe2+). The Fe-His stretching frequency of the normal α subunit in αFe2+βFe3+ (Hb M Hyde Park, HbM Saskatoon, HbM Milwaukee) is not related to the O2 affinity in the T structure (Nagatomo et al. 2017b) but the Fe-His stretching frequency of the β subunit in αFe3+βFe2+ (HbM Iwate and HbM Boston) has a meaningful relationship within the T structure; it increases in the case of higher O2 affinity (Nagatomo et al. 2017a). The high-frequency shift of the Fe-His mode correlates with the pKa of Hisβ146, which is involved in the H-bond between Aspβ94 and Hisβ146 (Nagatomo et al. 2017a). The importance of this H-bond was previously reported by Perutz (1970).

The α and β differences in kinetics on O2 binding

In Ackers’ model, the pairing of the α and β subunits in the α2β2 tetramer is considered essential for the αβ dimer as an operand. Unzai et al. (1998) determined the kinetic constants of O2 binding (kon) and dissociation (koff) using a metal hybrid Hb. In the metal (M)–Fe hybrid Hb, the tetramer adopts the T state for M = Ni2+, Mg2+, and Cu2+ and the R state for M = Cr3+ and Co2+, irrespective of whether O2 is bound to Fe2+ or not (Unzai et al. 1998). They used Hb with an equilibrium constant (K = kon/koff) larger than 0.003 × 106 M−1 but smaller than 3 × 106 M−1, in terms of P50/mmHg, 0.2–200 mmHg. Here, it is calculated under the assumption that Henry’s gas constant (P/atm = K’m). For O2 at 298 K, K’ = 773 atm mol−1 kg (Chang and Thoman (2014)), and molar concentrations (molarity) are nearly weight molar concentrations, m (molality). The samples covered the T-to-R states. The overall trend is that kon is larger than koff in the R state than in the T state. This finding is in good agreement with the general idea of T and R states. Here, it is emphasized that both kon and koff show little difference between the α and β subunits in both the T and R states. A small difference between the α and β subunits in preserving the T and R differences is necessary to yield a large Hill constant. Thus, the conclusion from the M-Fe hybrid Hb is that the differences between α and β are negligible with respect to the O2 affinity.

According to the combined use of 1H NMR and spectrophotometric methods (Ho 1992; Johnson and Ho 1974; Sato et al. 2011), the O2 affinities of α and β subunits of HbA are indistinguishable in the absence of an allosteric effector. However, in the presence of IHP, the O2 affinity of the β subunits is slightly lower than that of the α subunits. Spiro’s group (Balakrishnan et al. 2009) pointed out from time-resolved resonance Raman studies distinguishing both subunits with isotope-labeled hemes that the ν4 mode reflects the tension of the T structure in the α subunit, but not that of the β subunit upon photodissociation of COHb, though, geminate recombination occurred equally in both.

The α and β differences in the crystallographic structures

Recently, the resolution of X-ray crystallographic analyses has become so high that the locations of hydrogen atoms can be deduced from the difference Fourier map (Park et al. 2006). The structural differences between the α and β subunits are presented in Table 1.

The deviation of the Fe ion from the heme plane (plane determined with 24 atoms of porphyrin ring, as shown in Fig. 1b) is 0.50 and 0.60 Å in two α subunits, and 0.45 and 0.40 Å in two β subunits in the deoxyHb (T structure). In contrast, it is 0.09 Å in α and 0.06 Å in the β subunits in the oxyHb (R structure). Thus, Fe is located slightly more out of the heme plane in the α than in the β subunits in the deoxyHb, but is in-plane in both the α and β subunits in the oxyHb. As shown in Table 1, the Fe-His bond lengths are 2.20 and 2.21 Å in two α, 2.16 and 2.19 Å in two β subunits in the deoxyHb, and 2.07 Å in α and 2.06 Å in the β subunit in the oxyHb. The location of the distal His (HisE7 = αH58, βH63) is important for the bound O2 to form an H-bond with Nε2 of HisE7. Close examination revealed that the H-bond distances from the O1 and O2 atoms are 2.82 and 2.70 Å in the α subunits and 3.06 and 3.02 Å in the β subunits. Therefore, the H-bond is stronger in the α subunits than in the β subunits. The Fe–O-O bond angle is 124° in the α subunits and 126° in the β subunits. Therefore, there is no essential difference between the α and β subunits in the structures of heme and its neighbors. Meanwhile, it has been pointed out that a H2O molecule is present in the heme pocket of the α subunit in deoxyHb and forms an H-bond with His E7 (αH58), but there is no H2O molecule in the heme pocket of β subunits.

The positions of hydrogen atoms can be determined more precisely using neutron diffraction for deuterated samples. The residues responsible for the Bohr effects were determined through pKa determination of the His residues with titrations combined with deuterium substitution (Ohe and Kajita 1980), and observations of NMR proton signals (Ho 1992). Although the α1β1 heterodimer was not distinguished from the α2β2 heterodimer in these studies, neutron scattering experiments successfully distinguished between the α1β1 and α2β2 heterodimers (Kovalevsky et al. 2010). To date, βHis146 has been thought to contribute to the alkaline Bohr effect in deoxyHb, and it was clarified by neutron diffraction that the β1His146 of α1β1 is protonated and forms a salt bridge with β1Asp94, but the β2His146 of α2β2 is neutral and its Cε-H and Nε-H interact with the COO− of β2Asp94 within a subunit (Kovalevsky et al. 2010). This is not the difference between the α and β subunits but definitely indicates that the α1β1 heterodimer is not the same as the α2β2 heterodimer.

The α and β difference in the roles for performing cooperativity

It was anticipated from the observation of the Fe-His stretching frequencies by Nagai and Kitagawa (1980) that the strain of the Fe-His bond in the T state would be larger in the α than the β subunits. Therefore, it was supposed that the effects of the movement of the Fe-His bond on the quaternary structure change are larger in the α subunits than in the β subunits. Ligand binding to the α subunit induces a quaternary structural change (Nagatomo et al. 2002a; 2011a). However, in the cavity mutant rHb(αH87G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the α subunit, ligand binding to the β subunits did not result in a quaternary structural change (Nagatomo et al. 2015). Unexpectedly, the affinity of the α subunits increased in rHb(βH92G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the β subunits (Fig. 5), and became similar to that of sperm whale Mb (Nagatomo et al. 2015), implying that it is equivalent to a monomer, whereas the structure of the deoxy state remained in the T structure (Nagatomo et al. 2015).

These observations suggest that the existence of the Fe-His bond in the α subunit causes a change in the quaternary structure of the tetramer to the R structure upon O2 binding, and increases the affinity of the β subunits (together with that of the remaining α subunit). Perutz pointed out that oxygen binding to the α subunit causes quaternary structural changes (Perutz 1970). In contrast, the Fe-His bond of the β subunit lowers the affinity of the α subunit, as illustrated in Fig. 8 (Nagatomo et al. 2015). The mechanism is unknown, but it has been observed that the EPR signal of Co2+ of α subunits exhibits large changes upon ligand binding to Fe2+ of the β subunits in α(Co2+)β(Fe2+) (Inubushi et al. 1983).

To explain this unknown mechanism, we assume the presence of a new force. In the α2β2 tetramer, the proximal His of F-helix is pulled toward Fe by the Fe-His chemical bond. On the contrary, the proximal His is pulled toward the protein due to the deviation from the minimum point of conformational energy of the globin in the absence of heme-Fe. They are in balance in the presence of heme-Fe. We call the protein force F tension, tentatively. The F tension strengthens Perutz force in the T state but weakens in the absence Fe-His bond. Thus F tension is independent from Perutz’s pulling force, and affects structure of F helix and globin conformation. Therefore, in the absence of Fe-His in rHb(βH92G), F tension is absent, and F helix in β subunit moves against the hemeFe as shown in Fig. 6. Although the presence of F tension is confirmed in β subunit, it is not in α subunit yet.

In the β mutant, rHb(βH92G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the β subunit, this movement is then transmitted to the subunit interfaces and finally to the heme of the α subunit. As a result, the affinity of the α subunits is expected to increase. We consider the tertiary structure change within the T structure to be t → r as mentioned earlier in “The α and β differences in the globin responses upon O2 binding.”

Actually, in the β mutant, Hb M Hyde Park (βH92Y), oxygen affinity (P50 = 20 mmHg) of α subunit is higher than that of α subunit of deoxyHbA. Probably, a distance, connected by Fe3+-Tyr, between F-helix and heme of the β subunit in HbM Hyde Park will be farther from heme than that in deoxyHbA. In the β mutant, HbM Milwaukee (βV67E), Fe3+-His instead of Fe2+-His is present. Although there is a difference between Fe2+ and Fe3+, a distance between F-helix and heme of the β subunit in Hb M Milwaukee will be almost the same as that in deoxyHbA. In fact, in the β mutant, HbM Milwaukee (βV67E), oxygen affinity (P50 = 40 mmHg) of α subunit is lower than that in rHb(βH92G) and HbM Hyde Park (βH92Y). An essence of this idea is also described on previous our paper (Nagatomo et al. 2017b).

By the way, the α and β difference in role for performing cooperativity could be found in valency hybrid Hbs. Philo et al. (1996) showed a significant difference between α and β subunit in the allosteric properties using valency hybrid Hbs (α+β and αβ+). For αβ+ the allosteric constant changed greatly in going from fluoride (high spin ligand of ferric heme) to azide (low spin ligand), whereas for α+β changed slightly. According to the Perutz stereochemical mechanism for cooperativity (Perutz 1979), the quaternary equilibrium in Hb is governed by the coupling of the changes in heme stereochemistry to the globin structure via the proximal His. Perutz mechanism is directly related to the spin state of the heme iron. A low-spin ferric heme is a good stereochemical mimic of an oxy- or CO-liganded ferrous heme, whereas the high-spin ferric heme state is in intermediate between the ferrous deoxy and ferrous liganded.

The α1–β2 interface is particularly important, where the so-called switch region (βFG and αC are in contact) and flexible joint (αFG and βC are in contact) are present. The H-bonds involving α42Tyr-β99Asp and β37Trp-α94Asp in deoxyHb mentioned above are cleaved in oxyHb; instead, another H bond is formed between β102Asn and α94Asp. When a mutation occurs in the former case, deoxy state is destabilized, and the affinity is raised and cooperativity disappears. When a mutation occurs in the latter case, oxy state is destabilized, and in Hb Kansas (β102Asn → Thr), both affinity and cooperativity decrease. Using recombinant hemoglobins, rHb(αH87G), rHb(βH92G), and rHb(αH87G/βH92G), Barrick et al. (2001) indicated that rHb(αH87G) and rHb(αH87G/βH92G) kept T structure, but rHb(βH92G) did not take the T structure upon ligand (CO) binding, and that rHb(βH92G)-CO binding tended to be dissociated to dimer, and that a ligand affinity of rHb(αH87G) was higher in α subunit than in β subunit. Furthermore, Barrick et al. (2001) pointed out that with the cavity mutant Hb, rHb(βH92G), four O2 molecules can bind to Hb molecules with higher affinity and less cooperativity. Furthermore, its β mutant, rHb(βH92G), was dissolved into dimers, although Nagatomo et al. (2021) prepared the same mutant and characterized the isolated tetramer in addition to the isolated dimer for the β mutant, rHb(βH92G). The Fe-His bond of the β subunit is required not only to yield cooperativity but also to maintain the tetramer structure.

In the ligand binding to the α or β subunit, we propose here the direction-dependent communication pathways between α and β subunits through the F tension: (i) αFe-His → F tension → αFG corner (joint region) → βC helix and (ii) βFe-His → F tension → βFG corner (switch region) → αC helix. If accepted, this would satisfactorily explain that in the α cavity mutant rHb(αH87G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the α subunit, (i) cannot take place, but (ii) can. It would also satisfactorily explain that in opposition, (i) can take place, but (ii) cannot occur in the β cavity mutant rHb(βH92G), which lacks the Fe-His bond in the β subunit. However, it is unknown why a decrease in the F tension in the β subunit of rHb(βH92G) raises the oxygen affinity of the α subunit (Nagatomo et al. 2015: 2017b).

The affinity of the α subunits is increased in the absence of the Fe-His bond of the β subunits, and the oxygen affinity of the β subunits is low irrespective of whether the Fe-His bond of the α subunits exists or not (Yonetani et al. 1998; Shibayama et al. 1986). Using Ni–Fe hybrid hemoglobins, α2(Ni)β2(Fe) and α2(Fe)β2(Ni), Shibayama et al. (1986) indicated as follows. In α2(Ni)β2(Fe), O2 binding to the β heme does not show cooperativity regardless of pH but the effect of O2 binding is transmitted to the α subunit, and probably induces the structure change of the α subunit upon O2 binding and α2(Ni)β2(Fe-CO), in which Ni-His bond is cleaved (namely, Ni2+ is four-coordinated), shows deoxy-like structure. On the other hand, in α2(Fe)β2(Ni), O2 binding to the α heme shows cooperativity at high pH (pH 8.5), though the cooperativity is asymmetric. This is probably due to dimer formation during oxygenation. Ni2+ coordination of α2(Fe-CO)β2(Ni) is five and Ni-His bond is usually formed regardless of pH.

Using nitric oxide (NO)–bound hemoglobin, Yonetani et al. (1998) indicated that cleavage of Fe-His of the α subunit prevented quaternary structural change of T to R and caused low oxygen affinity and they called it “Low-Affinity Extreme.”

Putting together these results, we summarize as follows: when the Fe-His in α subunit is absent, quaternary structure change from T to R prevents ligand bindings, namely, maintains T structure; on the other hand, perturbation of the Fe-His in β subunit (such as a cleavage of Fe-His in β subunit or ligand binding to β subunit) causes the tetramer structure to be unstable and a structure changes around heme in α subunit. We describe the same conclusions about the loss of Fe-His in α subunit. However, we found that loss of the Fe-His in β subunit causes an increase of oxygen affinity of α subunit by using rHb(βH92G) of tetramer. We concluded that relaxation (movement) of F helix in the β subunits as shown in Fig. 6 by disappearance of F tension is important to transmission to α subunit via α1β2 interaction through structure changes of the heme and then increase oxygen affinity of the α subunit.

This behavioral difference between the α and β subunits might reflect the difference in the magnitudes of strain imposed on the Fe-His bond of the α and β subunits. Thus, the asymmetry in the F tension reduction effects between the α and β subunits can be explained.

In deoxyHbA with α2β2 tetramer, affinity is low in both the α and β subunits, but ligand binding to the α subunit changes the quaternary structure and raises the affinities of the remaining subunits. The existence of the Fe-His bond in the β subunit lowers the affinity of the α subunit in the deoxy state, as revealed by the observation of rHb(βH92G) (Nagatomo et al. 2015). Therefore, the cooperative O2 binding in HbA is due to the different roles of the Fe-His bonds in the α and β subunits.

Although it has not been focused on so far, some differences may be present between the same type of subunits. In the metal hybrid Hb-like α(Fe2+)β(Fe3+ or M2+), the Fe-His stretching RR band shape of the α subunit is asymmetric, as shown in Fig. 9, whereas the Fe-His stretching band of the β subunit in the opposite combination is symmetric, suggesting that the two α subunits are not the same, while the two β subunits are identical (Fig. 9) (Nagatomo et al. 2015; 2017b; Nagai and Kitagawa 1980).

Fig. 9.

Demonstration of the Fe-His stretching RR band asymmetry of the α subunit in deoxyHbMs Hyde Park and Milwaukee, [α(Fe2+)β(Fe3+)]. The two deconvoluted bands in the T structure are shown by a red line. The blue-colored bands, which appear at higher pH, are attributed to the Fe-His stretching RR band of the R structure. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Nagatomo et al. (2017b), Fig. 6. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society

Beyond the Perutz-MWC scheme

As mentioned in the “Introduction,” the Perutz model (Perutz 1979) combined with the MWC theory (Monod et al. 1965) has attracted the attention of several researchers on Hb, and it is still popular. The essence of MWC theory is that cooperativity does not occur within a T or R quaternary structure, but the transition between them is the origin of cooperativity. A serious defect of this theory is that it cannot explain the effects of the heterotropic allosteric effectors (pH and organic phosphates). It was explained that the allosteric effectors bind to Hb only in the T state, changing the affinity but not the cooperativity (Perutz 1970).

To overcome these defects, Eaton’s group proposed the TTS theory, in which the tertiary structures t and r determine the affinity (Henry et al. 2002). The populations of deoxy- and several partially O2-bound states were deduced based on their free energies calculated from the partition functions with suitable binding constants specific to the t and r structures. The kinetic properties of the intermediates were investigated by encapsulation in silica gels in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors (Viappiani et al. 2004). The reduction of geminate recombination by IHP and BZF was explained in terms of a reduction in the population of r but not by a change in binding rate, under the assumption that the effectors do not affect R (Viappiani et al. 2004). This conclusion was also supported by a simulation in which the calculated saturation curve could reproduce the observed ones and the populations of partially O2-bound forms indicated the cooperativity of O2 binding (Viappiani et al. 2014). One of the difficulties in interpreting the observed results with the TTS theory is that the rate of tertiary structure change is slow. Therefore, the transition of the ns intermediate from R to T after the photodissociation of COHb remains difficult to explain.

To justify the TTS theory experimentally, Spiro’s group has extensively accumulated visible and ultraviolet absorption and resonance Raman data for intermediates in the ligand binding process of deoxyHbA (Balakrishnan et al. 2004; 2009; Jones et al. 2012; 2014). Pump/probe time-resolved absorption and Raman spectroscopies can be used for the photodissociation of COHb in the R-to-T direction (Balakrishnan et al. 2004). The silica-gel technique developed by Shibayama and Saigo (1999) was applied to detect the intermediates in the ligand binding process in the T-to-R direction, and it was found that the R to T transition of Trpβ37 in the hinge contact occurs with τs of 2.9 μs but that of Tyrα42 in the switch contact does with τs of 21 μs (Jones et al. 2014). Mizutani’s group reported an R → T quaternary change at approximately 20 μs from observations of ναFe-His and νβNi-His of Fe–Ni hybrid HbA, αFeβNi (Yamada et al. 2013).

The difference between the α and β subunits was investigated by labeling the α or β subunit with mesoheme (Jones et al. 2014) or isotope-substituted heme (Balakrishnan et al. 2009). It became clear that IHP binds to the α1α2 cleft, lowering the Fe-His stretching frequency of only the α subunit in the R state of the transient state (Jones et al. 2014). However, crystallographic analysis shows that BPG binds, which is a heterotropic allosteric effector such as IHP, between two β subunits in the T structure (Richard et al. 1993). In addition to the functional differences between the α and β subunits mentioned above, the conformations of the heme side chains, such as vinyl and propionyl groups, may be different (Marzocchi and Smulevich 2003; Nagai et al. 2018). The out-of-plane deformation of side chains upon ligand binding takes place in the β subunit of the α2β2 tetramer, but it does not occur in the isolated β subunits, as revealed by CD measurements (Nagai et al. 2018). Thus, changes in heme structure are associated with inter-subunit interactions. This might explain why protoheme IX was present in HbA during the evolution process. In fact, HbA reconstituted with mesoheme in which vinyl is substituted by an ethyl group (Fig. 1b) resulted in smaller cooperativity in O2 binding (Hill constant, n = 1.6 ~ 1.7) (Sugita and Yoneyama 1971; Yamamoto and Yonetani 1974) than the native HbA, which has protohemes (n = 2.5 ~ 3.0) (Imai 1982).

It is important to note that the structures represented by t and r in this study do not always indicate the static tertiary structures of the protein but also certain dynamical states of the E and F helices, as pointed out by Yonetani and Kanaori (2013), or certain deformed states of heme side-chains, as described below. The dynamical structures related with O2 affinity have been highlighted in a wide-angle X-ray scattering study by Makowski et al. (2011). The picosecond time-resolved RR measurements demonstrated that deformations of heme side chains occur prior to the out-of-plane movement of the Fe ion upon CO photodissociation, implying that the side chains of heme might be responsible for the primary process of ligand binding to HbA (Nagai et al. 2018).

The remaining problems to be solved are to clarify the markers of t and r of the α and β subunits in the T and R quaternary structures, and to confirm that the reality of t in T is identical to that of t in R. The Fe-His stretching frequency was used to diagnose the t and r of deoxyHb, but this band is practically absent in the ligand-bound form with the R structure. The quaternary structures can be classified into T or R using the UVRR bands of the Tyr and Trp residues and 1H NMR signals of H-bonded Tyrα42(-Aspβ99) and Trpβ37(-Aspα94). It is possible that quaternary structural changes under physiological conditions always involve local changes in tertiary structures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author contribution

Shigenori Nagatomo had the idea of the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Teizo Kitagawa. Shigenori Nagatomo and Masako Nagai commented on the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology for Scientific Research (C) to S.N. (17K05606), (20K03877) and Scientific Research (B) to T.K. (24350086), and by a research grant from the Research Center for Micro-Nano Technology, Hosei University, to M.N.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ackers GK, Perrella M, Holt JM, Denisov I, Huang Y. Thermodynamics stability of the asymmetric doubly-ligated hemoglobin tetramer (α+CNβ+CN)(αβ): methodological and mechanistic issues. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10822–10829. doi: 10.1021/bi971382x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackers GK. Deciphering the molecular code of hemoglobin allostery. Adv Protein Chem. 1998;51:185–253. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60653-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackers GK, Holt JM. Asymmetric cooperativity in a symmetric tetramer: Human hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1441–11443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair GS. The hemoglobin system. VI. The oxygen dissociation curve of hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1925;63:529–545. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)85018-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan G, Case MA, Pevsner A, Zhao X, Tengroth C, McLendon GL, Spiro TG. Time-resolved absorption and UV resonance Raman spectra reveal stepwise formation of T quaternary contacts in the allosteric pathway of hemoglobin. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:843–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan G, Zhao X, Podstawska E, Proniewicz LM, Kincaid JR, Spiro TG. Subunit-selective interrogation of CO recombination in carbonmonoxy hemoglobin by isotope-edited time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3120–3126. doi: 10.1021/bi802190f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick D, Ho NT, Simplaceanu V, Ho C. Distal ligand reactivity and quaternary structure studies of proximally detached hemoglobins. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3780–3795. doi: 10.1021/bi002165q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr C, Hasselbalch K, Krogh A. Über einen in biologischer Beziehung wichtigen Einfluss, den die Kohlensaurespannung des Blutes auf dessen Sauerstoffbindung ubt. Skand Arch Physiol. 1904;16:402–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1904.tb01382.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang R, Thoman JW., Jr . Physical chemistry for the chemical and biological sciences. University Science Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richard V, Dodson GG, Mauguen Y. Human deoxyhaemoglobin-2,3-diphosphoglycerate complex low-salt structure at 2.5 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:270–274. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV. The combination of haemoglobin with oxygen and with carbon monoxide. Biochem J. 1913;7:471–480. doi: 10.1042/bj0070471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada I, Takeuchi H (1986) Raman and ultraviolet resonance Raman spectra of proteins and related compounds. In: Clark RJH, Hester RE (eds) Advances in spectroscopy, John Wiley & Sons, Chiester, 113–196

- Henry ER, Bettati S, Hofrichter H, Eaton WA. A tertiary two-state model for hemoglobin. Biophys Chem. 2002;98:149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance studies on hemoglobin: cooperative interactions and partially ligated intermediates. Adv Protein Chem. 1992;43:153–312. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K. Allosteric effects in haemoglobin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Inubushi T, Ikeda-Saito M, Yonetani T. Isotropically shifted NMR resonances for the proximal histidyl imidazole NH protons in cobalt hemoglobin and iron-cobalt hybrid hemoglobins. Binding of the proximal histidine toward porphyrin metal ion in the intermediate state of cooperative ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1983;22:2904–2907. doi: 10.1021/bi00281a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, Ho C. Effects of ligands and organic phosphates on functional properties of human adult hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3653–3661. doi: 10.1021/bi00715a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Ackers GK. Thermodynamic analysis of human hemoglobin in terms of Perutz mechanism: extensions of the Szabo-Karplus model to include subunit assembly. Biochemistry. 1982;21:201–211. doi: 10.1021/bi00531a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EM, Balakrishnan G, Spiro TG. Heme reactivity in uncoupled from quaternary structure in gel-encapsulated hemoglobin: resonance Raman spectroscopic study. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3461–3471. doi: 10.1021/ja210126j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EM, Monza E, Balakrishnan G, Blouin GC, Mak PJ, Zhu Q, Kincaid JR, Guallar V, Spiro TG. Differential control of heme reactivity in alpha and beta subunits of hemoglobin: A combined Raman spectroscopic and computational study. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10325–10339. doi: 10.1021/ja503328a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa T, Nagai K, Tsubaki M. Assignment of the FeNε(His F8) stretching band in the resonance Raman spectra of deoxy myoglobin. FEBS Lett. 1979;104:376–379. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80856-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa T, Nagai K. Resonance Raman evidence for a stretched FeNε (His F8) bond in the T-structure deoxyhemoglobin. In: Ho C, editor. Hemoglobin and oxygen binding. New York: Elsevier Biomedical; 1982. pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa T. The heme protein structure and the iron histidine stretching mode. In: Spiro TG, editor. Biological applications of Raman spectroscopy. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- Koshland DE, Némethy G, Filmer D. Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevsky AY, Chatake T, Shibayama Park SY, Ishikawa T, Mustyakimov M, Fisher Z, Langan P, Morimoto Y. Direct determination of protonation states of histidine residues in a 2 Å neutron structure of deoxy-human normal adult hemoglobin and implications for the Bohr effect. J Mol Biol. 2010;398:276–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski L, Bardhan J, Gore D, Lal J, Mandava S, Park S, Rodi DJ, Ho NT, Ho C, Fischetti RF. WAXS studies of the structural diversity of hemoglobin in solution. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:909–921. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzocchi MP, Smulevich G. Relationship between heme vinyl conformation and the protein matrix in peroxidases. J Raman Spectrosc. 2003;34:725–736. doi: 10.1002/jrs.1037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa S, Mawatari K, Yoneyama Y, Kitagawa T. Correlation between the ironhistidine stretching frequencies and oxygen affinity of hemoglobins. A continuous strain model. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1108–1113. doi: 10.1021/ja00291a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: A plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Nagai M, Tsuneshige A, Yonetani T, Kitagawa T. UV resonance Raman studies of α-nitrosyl hemoglobin derivatives: Relation between the α1-β2 subunit interface interactions and the Fe-histidine bonding of α heme. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9659–9666. doi: 10.1021/bi990567w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Nagai M, Shibayama N, Kitagawa T. Differences in changes of the α1-β2 subunit contacts between ligand binding to the α and β subunits of hemoglobin A: UV resonance Raman analysis using Ni-Fe hybrid hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10010–10020. doi: 10.1021/bi0200460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Jin Y, Nagai M, Hori H, Kitagawa T. Changes in the abnormal α-subunit upon CO-binding to the normal β-subunit of Hb M Boston: Resonance Raman, EPR, and CD study. Biophys Chem. 2002;98:217–232. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(02)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Nagai M, Mizutani Y, Yonetani T, Kitagawa T. Quaternary structures of intermediately ligated human hemoglobin A and influences from strong allosteric effectors: Resonance Raman investigation. Biophys J. 2005;89:1203–1213. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Nagai M, Kitagawa T. A new way to understand quaternary strucature changes of hemoglobin upon ligand binding on the basis of UV-resonance Raman evaluation of inter-subunit interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10101–10110. doi: 10.1021/ja111370f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo S, Nagai M, Kitagawa T (2011b) Resonance Raman investigation of quaternary structure change in hemoglobin upon ligand binding. In: Nagai M (ed) Hemoglobin: Recent Developments and Topics, Research Signpost, Kerala, India, pp 37–61

- Nagatomo S, Nagai Y, Aki Y, Sakurai H, Imai K, Mizusawa N, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Nagai M (2015) An origin of cooperative oxygen binding of human adult Hemoglobin: different roles of the α and β subunits in the α2β2 tetramer. PLoS ONE 10:e0135080. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nagatomo S, Okumura M, Saito K, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Nagai M (2017a) Interrelationship among the Fe-His bond strengths, oxygen affinities and intersubunit hydrogen-bonding changes upon ligand binding in β subunit of human hemoglobin; the alkaline Bohr effect. Biochemistry 56:1261–1273. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01118 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagatomo S, Saito K, Yamamoto K, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Nagai M (2017b) Heterogeneity between two α subunits of α2β2 human hemoglobin and O2 binding properties: Raman, 1H nuclear magnetic resonance, and terahertz spectra. Biochemistry 56:6125–6136. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00733 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Nagai M (2021) Roles of Fe-His bonds in stability of hemoglobin: recognition of protein flexibility by Q Sepharose. Biophys J 120:1–12. 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nagai K, Kitagawa T. Differences in Fe(II)-Nε(His-F8) stretching frequencies between deoxyhemoglobins in the two alternative quaternary structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2033–2037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, Kitagawa T, Morimoto H. Quaternary structures and low frequency molecular vibrations of haems of deoxy and oxyhaemoglobin studied by resonance Raman scattering. J Mol Biol. 1980;136:271–289. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Mizusawa N, Kitagawa T, Nagatomo S. A role of heme side-chains of human hemoglobin in its function revealed by circular dichroism and resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biophys Rev. 2018;10:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s12551-017-0364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohe M, Kajita A. Changes in pKa values of individual histidine residues of human hemoglobin upon reaction with carbon monoxide. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4443–4450. doi: 10.1021/bi00560a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoli M, Dodson G, Liddington RC, Wilkinson AJ. Tension in haemoglobin revealed by Fe-His(F8) bond rupture in the fully liganded T-state. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:161–167. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Yokoyama T, Shibayama N, Shiro Y, Tame YJR. 1.25 Å resolution crystal structures of human haemoglobin in the oxy, deoxy and carbonmonoxy forms. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz MF, Rossmann MG, Cullis AF, Muirhead H, Will G, North AC. Structure of haemoglobin: a three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 5.5-A. Resolution, obtained by X-ray analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz MF. Stereochemistry of cooperative effects in haemoglobin. Nature. 1970;228:726–739. doi: 10.1038/228726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz MF. Regulation of oxygen affinity of hemoglobin: Influence of structure of the globin on the heme iron. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:327–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philo JS, Dreyer U, Lary JW. Quaternary structure dynamics and carbon monoxide binding kinetics of hemoglobin valency hybrids. Biophys J. 1996;70:1949–1965. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79760-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Tai H, Nagatomo S, Imai K, Yamamoto Y. Determination of oxygen binding properties of the individual subunits of intact human adult hemoglobin. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2011;84:1107–1111. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.20110104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Morimoto H, Miyazaki G. Oxygen equilibrium study and light absorption spectra of Ni(II)-Fe(II) hybrid hemoglobins. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Imai K, Morimoto H, Miyazaki G, Saigo S. Oxygen equilibrium properties of Nickel(II)-Iron(II) hybrid hemoglobins cross-linked between 82β1 and 82β 2 lysyl residues by bis(3,5-dibromosalicyl)fumarate: determination of first two-step microscopic Adair constants for human hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4773–4780. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Morimoto H, Saigo S. Reexamination of the hyper thermodynamics stability of asymmetric cyanomet valency hybrid hemoglobin, (α+CN-β+CN-)(αβ): no preferentially populating asymmetric hybrid at equilibrium. Biochemistry. 1997;34:4375–4381. doi: 10.1021/bi970009m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Morimoto H, Saigo S. Asymmetric cyanomet valency hybrid hemoglobin, (α+CN-β+CN-)(αβ): the issue of valency exchange. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6221–6228. doi: 10.1021/bi980134d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Saigo S. Kinetics of the allosteric transition in hemoglobin within silicate sol-gels. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:444–445. doi: 10.1021/ja983652k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama N, Saigo S. Direct observation of two distinct affinity conformations in the T state human deoxyhemoglobin. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:50–53. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y, Yoneyama Y. Oxygen equilibrium of hemoglobins containing unnatural Hemes. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:389–394. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Karplus M. A mathematical model for structure-function relations in hemoglobin. J Mol Biol. 1972;72:163–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyuma I, Shmizu K, Imai K. Effect of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate on the cooperativity in oxygen binding of human adult hemoglobin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;43:423–428. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(71)90770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unzai S, Eich R, Shibayama N, Olson JS, Morimoto H. Rate constants for O2 and CO binding to the α and β subunits within the R and T states of human hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23150–23159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viappiani C, Bettati S, Bruno S, Ronda L, Abbruzzetti S, Mozzarelli A, Eaton WA. New insights into allosteric mechanisms from trapping unstable protein conformations in silica gels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14414–14419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405987101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viappiani C, Abbruzzetti S, Ronda L, Bettati S, Henry ER, Mozzarelli A, Eaton WA. Experimental basis for a new allosteric model for multisubunit proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12758–12763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413566111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Ishikawa H, Mizuno M, Shibayama N, Mizutani Y. Intersubunit communication via changes in hemoglobin quaternary structures revealed by time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy: direct observation of the Perutz mechanism. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:12461–12468. doi: 10.1021/jp407735t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Yonetani T. Studies on modified hemoglobins: IV. Hybrid hemoglobins containing proto- and mesohemes and their oxygenation characteristics. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7964–7968. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonetani T, Tsuneshige A, Zhou Y, Chen X. Electron paramagnetic resonance and oxygen binding studies of α-nitrosyl hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20323–20333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonetani T, Park SI, Tsuneshige A, Imai K, Kanaori K. Global allostery model of hemoglobin. Modulation of O2 affinity, cooperativity, and Bohr effect by heterotropic allosteric effectors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34508–34520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonetani T, Laberge M. Protein dynamics explain the allosteric behaviors of hemoglobin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonetani T, Kanaori K (2013) How does hemoglobin generate such diverse functionality of physiological relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834:1873–1884. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yuan Y, Tam MF, Simplaceanu V, Ho C. New look at hemoglobin allostery. Chem Rev. 2015;115:1702–1724. doi: 10.1021/cr500495x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]