Abstract

Maintaining stable native conformation of a protein under a given ecological condition is the prerequisite for survival of organisms. Extremophilic bacteria and archaea have evolved to adapt under extreme conditions of temperature, pH, salt, and pressure. Molecular adaptations of proteins under these conditions are essential for their survival. These organisms have the capability to maintain stable, native conformations of proteins under extreme conditions. The enzymes produced by the extremophiles are also known as extremozyme, which are used in several industries. Stability and functionality of extremozymes under varying temperature, pH, and solvent conditions are the most desirable requirement of industry. α-Amylase is one of the most important enzymes used in food, pharmaceutical, textile, and detergent industries. This enzyme is produced by diverse microorganisms including various extremophiles. Therefore, understanding its stability is important from fundamental as well as an applied point of view. Each class of extremophiles has a distinctive set of dominant non-covalent interactions which are important for their stability. Static information obtained by comparative analysis of amino acid sequence and atomic resolution structure provides information on the prevalence of particular amino acids or a group of non-covalent interactions. Protein folding studies give the information about thermodynamic and kinetic stability in order to understand dynamic aspect of molecular adaptations. In this review, we have summarized information on amino acid sequence, structure, stability, and adaptability of α-amylases from different classes of extremophiles.

Keywords: Extremophile, α-Amylase, Protein adaptation, Folding, Protein stability

Introduction

Microorganisms which have capability to survive well in extreme environment and also reproduce in that environment are called extremophiles. Extremophiles thrive well under physicochemical extremes of temperature, pH, pressure, and salt (Brininger et al. 2018; Merino et al. 2019). They are classified as thermophilic (adapted to extreme temperature), psychrophilic (thrive well at lower temperature), halophilic (salt-tolerant ability), acidophilic (at acidic pH), and barophilic or piezophilic (high pressure) (Rampelotto 2013; Dumorne et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2020). Some of the extremophiles can survive in more than one extreme condition like extreme pH and temperature for thermoacidophile, thermoalkaliphile, psychroacidophile, and psychroalkaliphile (Rampelotto 2013). Most of the extremophiles belong to the domain archaea and eubacteria while very few to the eukaryote (Hug et al. 2016). Extremophile research is important not only from an academic but also from industrial point of view. Additionally, understanding of the extremophile chemistry and biology can answer fundamental questions like origin of life on earth, possibility of life on other planets, and molecular adaptation of biomolecules (Hough and Danson 1999; Harrison et al. 2013; Merino et al. 2019). The applied aspects of extremophile research are mainly focused on enzymes which are produced by these organisms and which have industrial applications. Enzymes having extremophilic origin are also termed as extremozymes. There is a long list of such enzymes, e.g., α-amylase, cellulase, DNA polymerase, lipase, proteases, pullulanase, and xylanase, which have important industrial applications (Kumar et al. 2018; Raddadi et al. 2015; Dumorne et al. 2017). Extremozymes can be isolated from microorganisms of diverse habitats. The marine habitat has huge variation, e.g., salinity, pressure, and temperature, in terms of unfavorable conditions whose potential has yet to be explored (Dalmaso et al. 2015). Extraordinary capability of the extremozymes to keep themselves stable both structurally and functionally in adverse environmental conditions make them highly efficient and useful in the enzyme industry. Extreme environments pose new challenges to microorganisms for their survival; therefore, different strategies are adopted by extremophiles. Molecular adaptation may occur at DNA, lipid, and protein level but being dynamic in nature, protein adaptation is the most prominent. The relative distribution and usage of twenty amino acids in the structure play a major role towards the adaptations of these proteins under extreme environment (Panja et al. 2020).

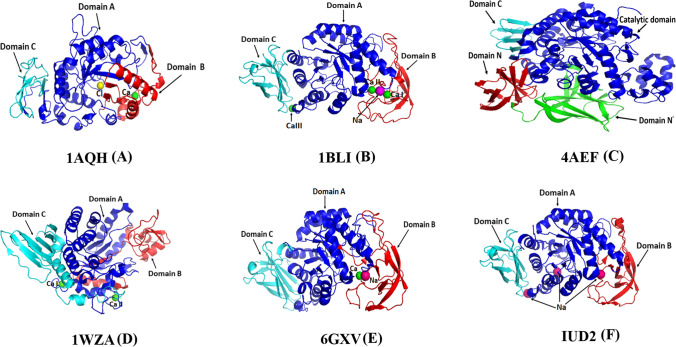

α-Amylase is an amylolytic enzyme which catalyzes breakdown of the internal α,1–4-glycosidic bond of various polymers like starch and other polysaccharides and converts them into low molecular weight monomers and oligomers (Janecek et al. 2014; Janecek and Gabrisko 2016). On the basis of amino acid sequence analysis, α-amylases have been classified as part of the glycoside hydrolase family 13 (GH 13) (Janecek and Gabrisko 2016; Janecek and Svensson 2016). Microbial α-amylases are one of the most important industrial enzymes having applications in pharmaceutical, medical, textile, paper, and alcohol industries (Farooq et al.2021; Mehta and Satyanarayana 2016). They also have potential in the biodegradation of n-alkanes which are produced as a petroleum by-product (Pinto et al. 2020). Some of the bacterial α-amylase require metal ions like calcium and sodium for their structural and functional integrity but this requirement may vary depending on the sources from which they have been isolated (Li et al. 2016; Cheng et al. 2017). Physicochemical properties of α-amylases vary enormously depending on their ecological habitat. Among α-amylases, bacterial and archaea α-amylases have shown more variability in terms of their adaptation towards pH, temperature, and salinity (Mehta and Satyanarayana 2016). Thermophilic and hyperthermophilic enzymes survive well at temperatures above 60 and 80 °C respectively and even sometimes above 100 °C (Janicke and Böhm 1998; Nisha and Satyanarayana 2016). Acidophilic and alkaliphilic enzymes require pH lower than 4 and greater than 8 respectively and can even survive at extreme pH (Dhakar and Pandey, 2016; Jin et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2020). In terms of pressure, they are found in the deep ocean where pressures can reach up to 110 MPa or 1100 bar (Dalmaso et al. 2015; Ichiye 2018). The molecular weight of microbial α-amylases varies from 10 to 210 kDa (Janecek et al. 2014; Mehta and Satyanarayana 2016). α-Amylases from different microorganisms differ in their amino acid sequence but most of them have common structural features like the presence of an alpha beta barrel fold (α/β)8 and three domain architectures (with the exception of maltogenic amylases, where there is an additional domain called D domain with unknown function) (Nielsen and Borchert, 2000; Janecek et al. 2014). Another notable variation observed in the α-amylase from Halothermothrix orenii (AmyA) is the occurrence of an additional N-terminal domain, called the N domain (Tan et al. 2008). Active-site residues are conserved among α-amylases from microbial, plant, and animal sources with the catalytic triad consisting of two aspartic acids and one glutamic acid. The number of active-site amino acids also varies from enzyme to enzyme (Janecek et al. 2014). Four residues are typically involved in calcium binding, out of which three residues are strictly conserved among different α-amylases (Asn, Asp, and His) while the fourth residue is not conserved (Janecek et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017). Although a large number of extremophilic α-amylases are known, very few have been studied in detail with regard to their structure, stability, folding, and dynamics which together may hold the answer to the extraordinarily adaptability of this class of enzymes. This review discusses progress made to understand the molecular determinants of stability and flexibility in extremophilic α-amylases that are responsible for their adaptation in diverse extreme environments. To understand the mechanism of adaptation, comparative analysis of sequences and structures of representative α-amylases from psychrophilic, thermophilic, halophilic, acidophilic, and alkaliphilic microorganisms has been carried out with reference to α-amylases from mesophilic microorganisms. Despite the huge number of industrial applications of α-amylases, correlation between structural adaptations and protein dynamics is still not clear; this might be due to fewer unfolding/folding studies available in literature. The majority of published studies on α-amylases have been restricted to find melting temperature (Tm), pH optima, salt requirement, sequence, and structural comparison. In this review, for the first time, we have included and discussed the protein unfolding-folding studies of the α-amylases from all the major classes of extremophiles. These studies are important to understand both thermodynamic and kinetic stability. There are a number of other reviews on microbial α-amylases covering classification, source organisms, industrial and biotechnological applications, etc. (Nielsen and Borchert 2000; Farooq et al.2021; Mehta and Satyanarayana 2016). Some review articles have discussed the specific adaptation in α-amylases like thermophilic (Kikani and Singh 2021; Hiteshi and Gupta 2014) and psychrophilic (Feller 2013) but none of them has covered all the major extremophilic adaptations. Here we have summarized structural and functional adaptations in different classes of extremophilic alpha amylases in light of their static and dynamic properties. Additionally, multiple extremophilic adaptations like thermoacidophilic, alkalithermophilic, and halothermophilic in α-amylases have also been discussed. This information may help in engineering and designing novel α-amylases with potentially multiple extremophilic adaptations for industrial applications. For understanding molecular adaptations in α-amylases, we have included enzymes with known crystal structures and representative structures of each class of extremophile (shown as Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structure of extremophilic α-amylases from psychrophilic, PDB ID 1AQH (Aghajari et al., 1998) (A); thermophilic, IBL1 (Machius et al., 1998) (B); hyperthermophilic, 4AEF (Park et al., 2013) (C); halophilic, 1WZA (Sivakumar et al., 2006) (D); acidophilic, 6GXV (Agirre et al., 2019) (E); and alkaliphilic microorganisms 1UD2 (Nonaka et al., 2003) (F)

Factors responsible for protein stability in extreme environments

Each protein has the intrinsic property of maintaining its native conformation in different environmental conditions which is dictated by its amino acid sequence (Anfinsen 1973). The intrinsic stability of a protein is additive effect of various intermolecular and intramolecular non-covalent interactions (Jaenicke 1991; Goldenzweig and Fleishman 2018). Although protein stability can be achieved through thermodynamic and kinetic means, the property of kinetic stability may be of particular importance to industrial enzymes because in industrial environment, they get exposed to harsh conditions like extreme pH, temperature, and solvent. Thermodynamic stabilization refers specifically to a large free energy difference between the native and the unfolded states; on the other hand, kinetic stabilization corresponds to the existence of free energy barriers between the native and the unfolded states in the unfolding pathway (Colón et al. 2017; Lindorff-Larsen and Teilum 2021, Sanchez-Ruiz, 2010). One of the important factors controlling protein unfolding and folding is the cis–trans isomerization of X-Pro peptide bonds (Feller 2018). The stability of extremophilic proteins under extreme environmental conditions is governed by the interplay between a number of interactions such as hydrogen bonding, disulfide bonds, and electrostatic interactions (Chakravorty et al. 2017; Brininger et al. 2018). The stability of thermophilic proteins is due to some structural features like presence of increased number of salt bridges, electrostatic interactions, and strong hydrophobic protein core and a higher number of prolines (Hough and Danson 1999; Pace et al. 2011; Yu and Huang 2014; Chakravorty et al. 2017; Pucci and Rooman 2017). Structural flexibility of proteins from psychrophilic organisms result from low hydrophobicity in the protein core, low proline, and high glycine content (Hough and Danson1999; Feller 2003; Pica and Graziano 2016; Pucci and Rooman 2017). Thermophilic proteins, like Thermoanaerobacter brockii alcohol dehydrogenase (TBADH), show the involvement of additional salt bridges, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobicity, oligomerization, and strategically placed prolines to provide higher conformational stability than the mesophilic counterpart, Clostridium beijerinckii alcohol dehydrogenase (CBADH) (Bogin et al. 1998; Mishra et al. 2008). Similarly, acidophilic and alkaliphilic proteins show the preferences of acidic and basic amino acid residues respectively as their adaptive mechanism (Hough and Danson 1999; Reed et al. 2013).

These adaptive strategies of extremophilic proteins are not universal; they may vary depending on the origin and types of proteins. Bacterial and archaeal α-amylases are multidomain proteins which tend to unfold irreversibly (Strucksberg et al. 2007) (with the exception of cold-adapted α-amylase, Feller et al. 1999), so it may not be possible to determine the thermodynamic parameters of unfolding transition for most of the α-amylases. Thermophilic α-amylases unfold irreversibly by temperature, pH, and chemical denaturants (Fitter 2005). Therefore, their stability is expressed in terms of the half denaturation points by different denaturing agents, although this approach does not give the information regarding the unfolding pathway (Wakayama et al. 2019). While in the case of reversibly unfolding system, stability is measured using thermodynamic Eq. (1).

| 1 |

In the above equation, thermodynamic parameters like free energy of unfolding (∆G), change in enthalpy (∆H), heat capacity change (∆Cp), and entropy change (∆S) give the estimate of protein stability (Wakayama et al. 2019; Drobnak et al. 2010; Fersht 1999). In the case of solvent denaturation, m value (Eq. (2)) which is a proportionality constant and gives the idea of relative exposure of protein surface upon unfolding also helps to determine the unfolding transition (Fersht 1999). In Eq. (2), D is the denaturant concentration and ∆GH2O is the free energy of unfolding in water.

| 2 |

In this review, we have described different static and dynamic factors contributing towards the adaptive mechanism of different extremophilic α-amylases. The extremophilic α-amylases whose structure has been solved to illustrate the molecular adaptations in different α-amylases are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative α-amylases with known structures from extremophilic microorganisms

| Source organism | PDB ID | Ecological adaptation | Temp optima (°C) | pH optima | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis (AHA) | 1AQH | Psychrophilic | 4–25 | 7.5 | Aghajari et al., 1998, Feller et al., 1992 |

| Bacillus licheniformis (BLA) | 1BLI | Thermophilic | 90 | 7.0 | Machius et al., 1998, Yuuki et al., 1985 |

| Bacillus stearothermophilus (BSTA) | 1HVX | Thermophilic | 70 | 8.0 | Brosnan et al. 1990, Suvd et al., 2001 |

| Pyrococcus woesei (PWA) | 1MWO | Hyperthermophilic | > 100 | 5.5 | Linden et al., 2003, Koch et al., 1991 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus (PFTA) | 4AEF | Hyperthermophilic | 100 | 4.5 | Park et al., 2013, Jorgensen et al. 1997 |

| Halothermothrix orenii (AmyA) | 1WZA | Halophilic | 65 | 7.5 | Sivakumar et al., 2006, Mijts and Patel, 2002 |

| Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius (ABA) | 6GXV | Thermoacidophilic | 70 | 3.0 | Agirre et al., 2019, Schwermann et al., 1994 |

| Bacillus sp. KSM-K38 (AmyK38) | 1UD2 | Alkaliphilic | 55–60 | 8–9 | Nonaka et al., 2003, Hagihara et al., 2001 |

| Bacillus isolate KSM-1378 (AmyK1378) | 2DIE | Alkaliphilic | 55 | 8–8.5 | Shirai et al., 2007, Igarashi et al., 1998 |

Psychrophilic α-amylases

The psychrophilic organisms represent the most dominant class of extremophiles which are adapted to live at lower temperature (Feller 2003). The cold-adapted enzymes exhibit an increased flexibility in their protein core, as compared to their mesophilic and thermophilic counterparts, which results from several factors, such as a reduced number of electrostatic interactions, a lower number of prolines, a higher number of glycines, more hydrophobic residues on the protein surfaces, a fewer number of interface interactions, and noticeably shorter surface loops (Cavicchioli et al. 2011). The psychrophilic α-amylases have gotten the attention of the scientific community due to their industrial and academic importance (Feller 2013; Vester et al. 2015; Al-Ghanayem and Joseph 2020). In the past few years, these enzymes have been extensively used in the detergent industry as a key active enzyme component (Li et al. 2014). In beverage and food industries, α-amylases able to function at low temperature are preferred over their high-temperature counterparts due to advantages in energy conservation, lower contamination risk, and increased storage time (Sarmiento et al. 2015). There is a further need for stability and folding studies of these enzymes for their optimum application in different industries. One of the few extremophilic α-amylases which have been studied in detail in terms of their structure, stability, and folding perspective is the psychrophilic α-amylase from bacterium Alteromonas haloplanctics (AHA) (Feller et al. 1992, 1994, 1999; Feller 2003; Siddiqui et al. 2005a, b). The conformational changes during temperature unfolding of AHA when followed by circular dichroism (CD) and fluorescence spectroscopy showed reversible and cooperative unfolding transitions, having Tm 43.7 °C. The stability curve of AHA provides the optimum structural stability at low temperature (Feller et al. 1999). Thermodynamic parameters were calculated by differential scanning calorimetry. Despite multidomain protein, this is the only α-amylase known to exhibit reversible two-state thermal unfolding (Feller et al. 1999; Siddiqui et al. 2005b). The wild-type and Asn12Arg mutant of AHA exhibited biphasic unfolding pattern during transverse gradient gel electrophoresis (TUG-GE) at 12 °C, which is in contrast to thermal unfolding (Siddiqui et al. 2005a). In biphasic unfolding, the first transition corresponds to the unfolding of the least stable domain A, which also contains the active site, as confirmed by comparing the unfolding behavior of wild-type to the Asn12Arg mutant. The mutation Asn12Arg is located in domain A, and the Arg mutant is capable of forming an additional salt bridge with Asp15, thus disrupting the cooperativity of unfolding of Asn12Arg mutant (Siddiqui et al. 2005a). Unfolding studies of AHA indicate that disulfide bonds are also important for the activity of AHA by maintaining the correct conformation specifically around the active site, which gets disrupted upon reduction (although somewhat surprisingly, not even a single disulfide was found to be involved in the gross structural stabilization of AHA; Siddiqui et al. 2005a, b).

The arginine provides larger stability than the lysine by establishing a higher number of ionic interactions with the help of its guanidinium group (Sokalingam et al. 2012). Siddique et al. (2006) have investigated the role of individual lysine residues especially near the active site (K106) in cold adaptation of AHA by replacing with homoarginine (hR). For this, K106 of the domain B was modified to hR which shows that AHA with hR exhibit greater conformational stability than the wild-type enzyme. This might be due to the capability of hR to form salt bridge with side chain of E138. Simultaneously, the presence of the ion pair (hR106-E138) in modified AHA results in increased active-site rigidity and therefore a lower activity as compared to wild-type AHA (Siddiqui et al. 2006). Calorimetric measurements of kinetic (Km and Kcat) and thermodynamic parameters (enthalpy and entropy) of substrate hydrolysis and ligand binding respectively demonstrate that the active site of AHA exhibits enhanced structural fluctuations relative to mesophilic α-amylase from pig pancreas (PPA). As active-site residues are conserved in both AHA and PPA, the enhanced mobility may originate from side chains located distant to the active site. This study provides the kinetic and thermodynamic evidence for greater flexibility and reduced stability of active site in AHA, which may be a common cold-adaptive feature of psychrophilic proteins (D’ Amico et al. 2006). The unusual sensitivity of the active site in AHA to mutation has been recently explained by computational study (Socan et al. 2020). The role of non-covalent interactions in the temperature adaptation of AHA has been investigated by constructing two multiple mutants (Mut5 and Mut5CC) of AHA and comparing them with PPA. The results indicate that all these mutations collectively increase the network of weaker interactions in both the mutants which consequently increases the Tm and calorimetric enthalpy and decreases the cooperativity and reversibility of unfolding of AHA. Similarly, kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of enzymes with mutations in the catalytic fold were shifted towards PAA. Thus, it is clear that weaker interactions play the defining role in the temperature adaptations of AHA (D’ Amico et al. 2003). By using multiple AHA mutants (Mut5 and Mut5CC), equilibrium and kinetic unfolding/refolding in chemical and thermal denaturant demonstrates the importance of salt bridges, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonds in protein flexibility and stability (Cipolla et al. 2011).

The crystal structure of AHA shows low proline content in loops and turns. Proline provides rigidity to the X-Pro bond and therefore having less proline in loops and turns helps to increase the flexibility of secondary structure elements and hence facilitates the activity of the enzyme at lower temperatures (Aghajari et al. 1998). It also has a lower number of arginines in its core, because one arginine can form 5 hydrogen bonds, so having less Arg will have weaker electrostatic interactions and thus a reduced number of interdomain interactions which decreases the rigidity of the protein core. AHA also has fewer surface charge residues and thus has a smaller number of hydrogen bonds and consequently increased flexibility at its outer surface. The protein core of AHA in comparison with mesophilic α-amylases is less compact due to weaker hydrophobic interactions (Aghajari et al. 1998). All the above structural features collectively enhance the flexibility of AHA, thus making it suitable to work at low temperature. Flexibility at the active site is a major adaptation of psychrophilic α-amylases as evident by the abovementioned structure. Although the number of glycines may not be the indicator, the presence of a cluster of glycines provides the flexibility required for psychrophilic enzymes (Cavicchioli et al. 2011). By comparing the structure and amino acid sequence of psychrophilic α-amylases with the mesophilic α-amylase Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (BAA), it becomes clear that substitution and deletion of amino acids like proline, glycine in the loop regions, and non-covalent interactions like ion-pairs, aromatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and helix dipoles are less abundant in psychrophilic enzymes (Cavicchioli et al. 2011). Contrary to thermophilic proteins, higher proportions of non-polar groups and relatively larger number of negatively charged residues are present in the psychrophilic α-amylase (Feller 2003).

Thermophilic/hyperthermophilic α-amylases

Organisms which normally grow above 60 and 80 °C are called thermophiles and hyperthermophiles respectively. It is puzzling how a set of just twenty amino acid mutations (together with their non-covalent interactions) provides such an extraordinary stability to the thermophilic proteins (Jaenicke and Böhm 1998). There is an industrial requirement for thermophilic enzymes in various industries and as such this group of enzymes has been most extensively studied for the origin of thermostability (Berezovsky and Shakhnovich 2005; Luke et al. 2007; Carstensen et al. 2012). The α-amylase from archaea Pyrococcus furiosus (PFTA) is a hyperthermophilic enzyme which has been reported to maintain a stable and rigid conformation over a broad temperature range from 40 to 140 °C (Koch et al. 1990; Jorgensen et al. 1997). PFTA is a calcium-containing enzyme; however, the enzyme remains functional even at higher temperature in the absence of calcium (Laderman et al. 1993). Contrary to this, mutational analysis has shown that Cys165 was involved in zinc binding and both calcium and zinc together play determining role in the thermal stability of PFTA. PFTA is a homodimer with each subunit having a molecular weight of approximately 50 kDa (Savchenko et al. 2002). The crystal structure of PFTA was solved at 2.34 Å and revealed domains N, C, catalytic, and an additional N′ domain. The active site consists of three conserved residues Asp411, Glu437, and Asp502 and the two sides of the active site were lined by hydrophobic residues. The Lys92 from the N′ domain forms a salt bridge with the Glu504 of the catalytic domain and this interaction helps in the stabilization of the two domains. Due to this special feature of the active site, it is capable of hydrolyzing both starch and cyclodextrin even at higher temperature and thus has become an important industrial enzyme (Park et al. 2013). Kinetic studies of PFTA have revealed that thermal unfolding profile follows a two-state mechanism although due to onset of aggregation it appears biphasic. The activation energy of the unfolding pathway is 316 kJ/mol at 121 °C. Thermal denaturation data obtained from differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) shows a Tm around 106–107 °C; above this temperature, enzyme unfolds irreversibly but below this, it shows reversibility (Brown et al. 2013).

Another hyperthermophilic α-amylase which has been studied from structural point of view is that obtained from archaea Pyrococcus woesei (PWA). The enzyme exhibits extreme thermal stability and the maximum activity was observed at 100 °C (Koch et al. 1991). The crystal structure was solved at 2.5 Å resolution in three different forms in the presence of the ligands zinc, acrobase, zinc, and Tris (Linden et al. 2003). The special features of the PWA structure are the presence of two metal centers (Ca/Zn) in the vicinity of the active site. The first site (Site I) corresponds to calcium binding and the second site (Site II) is occupied by zinc. The zinc-binding site (Site II) is coordinated by His147, His152, and Cys166. Replacement of Cys166 by any other residues decreases the activity of PWA at high temperatures which indicates the importance of zinc in thermal stability. The disulfide bridges which are formed between Cys388 and Cys432 and another between Cys153 and Cys154 also thought to be involved in the thermal stability of PWA. The crystal structure of PWA showed the presence of additional ligand-binding sites. It is not clear how the presence of such a large number of metal ions are involved in hyperthermal stability of PWA (Linden et al. 2003).

The most studied thermophilic α-amylase is that obtained from Bacillus licheniformis (BLA). In fact, this is a mesophilic bacterium, but BLA isolated from this bacterium shows thermophilic-like characteristics (Tomazic and Klibanov 1988; Machius et al. 1995). There are several factors which impart thermal adaptation to BLA relative to its mesophilic counterpart BAA from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Structural comparison and mutational studies have shown that BLA has few internal domain regions (Asp121-Arg127 in B domain, and Glu250-Lys251 in A domain) and interdomain salt bridges (between Asp60-Arg146 and Asp204-Lys237 connect domains A and B) (Machius et al. 1995; Declerck et al. 2000). Mutational analysis involving the replacement of Asp190 by Phy190 shows the importance of aromatic-aromatic interactions in the stabilization of BLA (Machius et al. 2003). One of the most significant factors is the presence of a large number of histidine residues in BLA relative to BAA, which decreases the entropy of the unfolded state and thus stabilizes its native confirmation (Alikhajeh et al. 2010). It is one of the few examples where comparative study from structural, unfolding, and cosolvent-mediated refolding has been carried out in detail (Ahmad and Mishra 2020, 2022). Thermal unfolding of BLA and BAA shows that both enzymes undergo irreversible unfolding with Tm of 101 °C and 86 °C respectively in the presence of 2 mM calcium (Fitter and Haber-Pohlmeier, 2004). The comparative unfolding of both BLA and BAA in urea and guanidinium hydrochloride (GdmCl) indicates that BLA has an unusually higher stability towards urea denaturation than BAA and molten globule-like intermediates were observed during GdmCl unfolding of BLA (Ahmad and Mishra 2020). Highly thermal and acid-stable α-amylase with pH and temperature optima at 5 and 100 °C respectively was obtained from Bacillus licheniformis B4-423. As for the already discussed amino acid sequence and structural comparison between BAA and BLA, shortening of the loop region by deletion of Glu178-Gly179 in domain B and the orientation of Ala298 which helps to interact with Lys234 and Glu189 through ionic interactions in domain B are found to be key structural determinants of its thermal stability (as with BLA) (Wu et al. 2018). The α-amylase from Bacillus stearothermophilus, previously known as Geobacillus stearothermophilus (BSTA), is a thermophilic enzyme with pH and temperature optima at 5.5 and 75 °C respectively (Brosnan et al. 1990; Vihinen et al. 1990). Although BSTA shares significant amino acid sequence similarity (65%) with respect to the BAA and BLA enzymes, it still shows variation in its thermal stability, with optimum temperature of enzymatic activity for BSTA, BAA, and BLA being 75 °C, 60 °C, and 90 °C respectively. Such differences in thermal stability can be analyzed by comparing their amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structures. The crystal structure of BSTA was solved at 2.0 Å in the presence of the inhibitor acrobase and was compared with BLA in order to explain the stability differences between BSTA and BLA (Suvd et al. 2000, 2001).

Amino acid substitution in BSTA at IIe181-Gly182 changes the spatial arrangement of other residues, such as Asp207, which is no longer capable of coordinating with Ca2+ ion. The hydrogen bonding network is less prominent in BSTA than BLA, particularly domain A which has 10 fewer H bonds in the α-helices of BSTA and the (α/β)8 barrel is less stabilized than the BLA. However, domain B of BSTA has 6 more H bonds, which might be compensated by other factors in BLA. In addition to this, the protein core of BSTA is less hydrophobic than BLA as there are 13 histidines in BLA, while only 6 in BSTA (Suvd et al. 2001). Linden and Wilmanns (2004) have also described origin of temperature adaptations in thermophilic/hyperthermophilic and psychrophilic α-amylases by comparing the crystal structures of four α-amylases, each from mesophilic, psychrophilic, thermophilic, and hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Their results indicate that salt bridges confer significant thermal stability to hyperthermophilic (PWA) and thermophilic α-amylases (BSTA) as PWA has specially placed ring-like network of salt bridges in its domain B involving two residues Lys33 and Glu36 of α-helix 1 and another two residues Glu18 and Lys323 from α-helix 8. Although BSTA lacks such a network, it has a greater number of salt bridges than the mesophilic α-amylase Hordeum vulgare (HVA) and psychrophilic α-amylase Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis (PHA). Besides this, dimetal centers involving (Ca, Zn) and (Ca, Ca) also play important roles in the thermal stability of hyperthermophilic (PWA) and thermophilic (BSTA, BLA) α-amylases respectively (Linden and Wilmanns 2004).

There are a large number of factors which govern the stability of thermophilic proteins such as the increased hydrophobicity of the protein core, a higher number of salt bridges, an increased hydrogen bonding, a shortening of surface loops, an increased proline content, and a greater number of disulfide bonds (Jaenicke and Böhm 1998). Amino acid sequence analysis and structural comparison of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic α-amylases with their mesophilic counterparts indicate that the most significant factors are the presence of the salt bridges at specific places, an increased number of H bonds, and an increased hydrophobicity of the protein core in thermophilic α-amylases (BLA and BSTA) relative to the mesophilic α-amylases (BAA) (Machius et al. 1995; Alikhajeh et al. 2010). In addition to the above factors, disulfide bonds also play a crucial role in the hyperthermostability of PFTA and PWA (Linden et al. 2003; Park et al. 2013).

Halophilic α-amylases

Halophiles are a class of organisms which grow at high salt concentration; however, the requirement for salt (as a structural element) among the halophiles varies. Some halophiles can tolerate a certain level of salinity and are known as salt tolerant while others can cope with extreme conditions of salinity and are hence known as extreme halophiles. The halophilic microorganisms are mainly isolated from the deep ocean, salt pans, and salt marshes. The proteins of halophiles are adapted to withstand high salt concentration where other proteins get denatured (Tadeo et al. 2009; Moreno et al. 2013). These microorganisms employ molecular and physiological means to adapt to extreme salinity. The amino acid sequence comparison of 26 halophilic proteins showed the dominance of acidic over basic residues with significant reduction in positively charged lysine residues (Madern et al. 2000). Halophilic proteins exhibit certain key structural changes in their adaptation to high salt environments such as high content of acidic residues, fewer hydrophobic residues, and presence of increased number of salt bridges between acidic and basic residues (Sinha and Khare 2014; Arakawa et al. 2017). Halothermothrix orenii secretes α-amylase (AmyA) which has dual adaptation, i.e., halophilic as well as thermophilic, and grows optimally in 5% (w/v) NaCl at 65 °C (Mijts and Patel 2002). Therefore, its stability and adaptation provide glimpse of both thermo and halophilic world. The crystal structure of AmyA exhibits the typical structure of GH 13 family α-amylase with three domains A, B, and C and characteristic (α/β)8 barrel fold (Sivakumar et al. 2006). The active site is conserved with the catalytic triad made up of Asp224, Glu260, and Asp330. H. orenii secretes a second α-amylase (AmyB) with novel domain organization (Tan et al. 2008). Its structure consists of domains A, B, and C and an additional N domain, which helps to bind raw starch. This domain encompasses residues from 15 to 108 and forms an immunoglobin-like β-sandwich structure. Unlike AmyA, the calcium and sodium triad in AmyB consists of Ca,Na,Ca which forms additional interactions between domains A and B similar to BLA (Machius et al. 1995). Unlike other halophilic proteins which have predominantly acidic surfaces (Delgado-García et al., 2012), AmyA has a neutral protein surface with an equal number of negatively and positively charged residues. The negatively charged residues bind salt ions and thus help with the halophilic adaptation of proteins (Delgado-García et al. 2012). The presence of negatively charged residues, Asp128, Glu260, and Asp230 in the (α/β)8 barrel domain might be the most important characteristic of this enzyme. Like other α-amylases, this one also has two calcium and one sodium ion binding sites. Thermal stability of AmyA significantly increases with increasing salt (NaCl) concentration and stabilization mechanism is based on the formation of the oligomeric states in the presence of salt (Sivakumar et al. 2006). One of the particularly interesting α-amylases is that produced by the moderate halophile Halomonas meridiana which shows a maximum enzymatic activity in 10% NaCl (w/v); however, it can retain the activity even in 30% NaCl (Coronado et al. 2000). This α-amylase has a pH 7.0 optima but is functional up to pH 10.0. Due to this property, it is an important enzyme in detergent industry. Apart from mesophilic bacterial α-amylases, there are some α-amylases of archaeal origin which have halophilic adaptations, such as α-amylases from Haloferax mediterranei. Unlike previously discussed α-amylases which were moderately halophilic, this enzyme is extremely halophilic and is active at 50 °C and within the pH range 7.0 to 8.0. The enzyme requires 2.0 to 4.0 M NaCl for its optimal activity (Perez et al. 2003). An α-amylase (KVA) with moderate halophilicity has been isolated from bacteria Kocuria varians. Despite having a 68% sequence similarity to BAA and the same number of acidic and basic residues, this enzyme is halophilic in nature. Unlike BAA, the protein surface of KVA is dominated by acidic residues. Although in most of the cases, halophilic proteins undergo reversible thermal unfolding, this enzyme exhibited a salt-dependent reversibility to its thermal unfolding transition. The extent of reversibility is highly concentration dependent with a maximum 65% reversibility achieved at 2 M NaCl (Yamaguchi et al. 2011). A moderately halophilic α-amylase, having 110 kDa molecular weight, was isolated from Nesterenkonia sp. strain F. Maximum enzymatic activity of this α-amylase was observed in the range from pH 7.0 to 7.5 and 45 to 50 °C and it retained more than 60% of its maximum catalytic activity from 0 to 4 M NaCl. Its higher temperature optima, as compared to mesophiles, and its capability to work over a wide salt concentration range, have proved helpful in many industrial applications (Shafiei et al. 2012). In order to adapt in high salt environment, halophilic α-amylase from Marinobacter sp. has a larger number of acidic and hydrophobic residues (Kumar et al. 2016). During pH-induced unfolding, a molten globule state was observed and further to this the role of salt binding in the stabilization of secondary and tertiary structure of this α-amylase has been shown by using CD and fluorescence spectroscopy (Kumar and Khare 2015; Kumar et al. 2016).

The α-amylase from the halophilic archaeon, Haloarcula hispanica, as studied by Hutcheon et al. (2005), showed unique adaption, retaining almost 30% enzymatic activity even in the absence of salt in spite of being highly halophilic in nature. A recent study of the amino acid sequence of this enzyme suggests that this might belong to a new subfamily GH 13 and the characteristic feature is the presence of Tyr79 in TIM barrel of catalytic site (Janecek and Zamocka 2020). It retained a fully folded conformation even after incubation in 6 M urea in the presence of 4 M NaCl. However, the removal of salt leads to its unfolding in urea (Hutcheon et al. 2005). The maximum activity of this α-amylase was obtained at pH 6.5, 50 °C, and 4–5 M NaCl (Hutcheon et al. 2005). In silico structural and amino acid sequence analysis of three α-amylases from the halophilic archaea, Haloarcula marismortui, Haloarcula hispanica, and Halalkalicoccus jeotgali, reveals that in comparison to their non-halophilic homologs, they possess some special conformational features, such as a lesser tendency for helix formation and a higher coil-forming propensity. These topological properties help to generate a flexible conformation in environments with high ionic strength. Negatively charged residues, especially Asp, are favored the most due to their helix-breaking capacities. Non-polar residues with less hydrophobic side chains (Ala and Val) are also preferred over residues with long side chain like Lys. The presence of less hydrophobic residues in halophilic proteins reduces the chances of aggregation due to non-specific intramolecular interactions (Zorgani et al. 2014). For detailed understanding of molecular determinants of halophilic adaptations of α-amylase, more crystal structures need to be solved and compared against their mesophilic counterparts. Besides that, unfolding and refolding studies at different pH and in different chemical denaturants are required for understanding the contribution of electrostatic interactions for their adaptation.

Acidophilic α-amylases

The initial steps of starch hydrolysis (like liquefaction and saccharification) are carried out at acidic pH by alpha amylase. Thus, stability at low pH is a necessity of hydrolytic enzymes (like α-amylases) which are used in several starch-based industries like paper, textile, food, brewing, and detergents (Parashar and Satyanarayana 2018). Most proteins lose their structural integrity at acidic or basic pH because extremes of pH cause alteration in ionization states of negatively charged (aspartic and glutamic acid) and positively charged (lysine and arginine) residues, which results in electrostatic repulsion and eventually loss of structure (Reed et al. 2013). Thus, the proteins of acidophilic organism must find the way to survive in such an adverse condition of pH, which may include the presence of a higher number of acidic residues (Asp and Glu), an increased extent of hydrogen bonding, and salt bridges (Settembre et al. 2004; Charkravorty et al. 2017; Parashar and Satyanarayana 2018). Acidophiles and alkaliphiles are adapted for their peripheral structural proteins while the cytoplasm of these organisms is maintained at neutral pH by ATP-driven proton pumps (Sanchez 2010). Acidophilic bacteria are often found in thermophilic environments; therefore, they frequently exhibit both acidic and thermal adaptation (Settembre et al. 2004). In this class, a calcium-independent α-amylase was obtained from Bacillus acidicola (Sharma and Satyanarayana 2012). This enzyme remains active over a broad pH range (3.0 to 7.0) and temperature (30 to 100 °C) range, although its maximum catalytic activity was observed at pH 4 and 60 °C. The optimal activity of this α-amylase is completely independent of calcium (Sharma and Satyanarayana 2012). Further changes in temperature and pH result in a loss of activity which coincides with the loss of secondary structure (Sharma and Satyanarayana 2013). A thermoacidophilic calcium-independent α-amylase with an optimum activity at pH 6 and 80 °C was isolated from Geobacillus thermoleovorans (Sudan et al. 2018). A clear biphasic unfolding transition was observed during thermal unfolding as monitored by far-ultraviolet circular dichroism (UV CD) spectroscopy. The first transition appears between 60 and 75 °C and the second between 85 and 95°. The second phase between 75 and 85° corresponds to an intermediate species (Sudan et al. 2018). One more calcium-independent α-amylase (KRA) was expressed and purified from Bacillus sp. KR8104. Although this enzyme remains active over a broad pH range, its maximum activity is observed at acidic pH (4.0–6.0) and elevated temperatures (75–80 °C). Both the enzyme activity and the stability of this α-amylase were found to be independent of its calcium binding (Sajedi et al. 2005). It was demonstrated that shifting the pKa values of amino acid residues at or around active site of this α-amylase towards acidic pH is due to changes in hydrogen bonding, solvent accessibility of active-site residues, and shape of the active site (Alikhajeh et al. 2007). Sequence alignment and structural comparison with BLA showed that the amino acid substitutions A52S, V154N, I212T, Y265N, T297S, and A379S near the active site may affect mobility and structure of the active site, most probably through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Some replacements of basic amino acid residues in KRA as compared to BLA were observed at N188R, N246K, D260K, N280K, and Q291H which increases the positive charge and thus impacts upon the pH profile of KRA. It has been shown that hydrogen bonding changes the pKa values of amino acid residues (Porter et al. 2006). As KRA has one extra hydrogen bond between Glu261 and Arg229, this may have a significant effect on the pKa of the active-site residues (Sajedi et al. 2005).

One of the most extensively studied acidophilic amylases is that obtained from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius strain ATCC 27,009 (Amy) which grows optimally at pH 3.0 and 75 °C. There is a 30% reduction in both positive and negatively charged surface residues in Amy as compared to its most closely related sequence neighbors (Schwermann et al. 1994). Reduction in the number of surface charge residues in acidophilic proteins is an adaptation to low pH environment due to the fact that at low pH, positively charged residues get protonated and the resultant repulsion between promotes protein unfolding. In the same way, presence of excess negatively charged residues may result in their destabilization due to disruption of stabilizing interaction above their pI values (Schwermann et al. 1994; Parashar and Satyanarayana 2018). The crystal structure of α-amylase from Alicyclobacillus sp. was solved at 2.1 Å and this structure reveals the presence of subsites in the active site which help to accommodate the α-1,6 branch point in the substrate. It can accommodate both amylopectin and pullulan substrates which increases its applicability from an industrial point of view. The catalytic site residues of this α-amylase are conserved with the signature triad of the GH 13 family, i.e., Asp234, Glu265, Asp332 (Agirre et al. 2019). Presence of more negatively charged and less positively charged residues along with their strategic placement of hydrogen bonds are just a few of the structural adaptations of acidophilic α-amylases. However, more structural studies of the acidophilic α-amylases along with investigations of their charged residue mutants are required before generalizing these factors.

Alkaliphilic α-amylase

Alkaliphiles survive in highly alkaline environment (pH > 9.0) and belong to all three domains of life, i.e., bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (Mamo, 2020; Horikoshi 1999). However, industrially important alkaliphilic enzymes like proteases, cellulases, lipases, and amylases are commonly obtained from Bacillus sp. (Fujinami and Fujisawa 2010; Mamo and Mattiasson 2020). Alkaliphilic α-amylases are extensively used in the detergent industry (Fujinami and Fujisawa 2010; Sarethy et al. 2011). As for acidophilic α-amylases, a few alkaliphilic α-amylases also show thermophilic adaptation (Gu et al. 2021). An alkaliphilic α-amylase with broad pH and temperature optima isolated from the Bacillus subtilis strain AS-S01a does not require added calcium for its optimal activity and stability—a feature which may be useful for future industrial applications. The maximum enzymatic activity of this α-amylase is obtained at pH 9 and 55 °C (Roy et al. 2012). Another alkaliphilic α-amylase, AmyK38, was expressed, purified, and characterized from Bacillus sp. KS38 (Hagihara et al. 2001). The optimum ranges of pH and temperature for this α-amylase were 8.0 to 9.5 and 55 to 60 °C respectively. The enzyme showed a high resistance towards chelating agents like EGTA and EDTA. The crystal structure of AmyK38 was solved in the absence of calcium at 2.13 Å resolution (Nonaka et al. 2003). Although it shares the same fold as BLA, it requires Na+ ions instead of Ca2+ ions to maintain structural integrity with three sodium ion-binding sites confirmed by structure (Nonaka et al. 2003).

Recombinant α-amylase from Bacillus sp. strain TS-23 is thermoalkaliphilic as shown in its pH and temperature profile. Maximum activity is observed at pH 8 and 70 °C; however, more than 80% of its activity is retained at pH 6.1 to 9.0. A heating rate dependence of the irreversible thermal unfolding kinetics suggests the presence of kinetic barriers during unfolding (Chi et al. 2010). The unfolding transitions in urea and GdmCl are non-coincidental with respect to loss of structural and functional properties. The stability of its native conformation is more susceptible to GdmCl than urea denaturation. Both thermal and chemical unfolding transitions are fully irreversible. It shows significant resistance towards thermal and chemical unfolding in the presence of stabilizing cosolvents TMAO and sorbitol in a concentration-dependent manner (Chi et al. 2010, 2012).

Moderately alkaliphilic α-amylase (AmyK1378) with pH and temperature optima at 8.5 and 55 °C respectively was isolated from Bacillus sp. KSM 1378 (Igarashi et al. 1998). Amino acid sequence comparison with other α-amylases has shown the presence of four conserved regions which have been designated as regions I, II, III, and IV. The crystal structure of the enzyme was solved at 2.1 Å and compared with other alkaline and non-alkaline enzymes including α-amylase (Shirai et al. 2007). The enzyme retained GH 13 characteristic folds with three domains A, B, and C, three calcium-binding sites, and one sodium-binding site. The active site of AmyK1378 is conserved with respect to α-amylase from AmyK38, with residues Asp236, Glu266, and Asp333. Similar to the other alkaliphilic enzymes including α-amylases, AmyK1378 also shows loss of Lys-Asp pair and gain of Arg-Asp/Glu pair as an adaptive feature.

An alkaliphilic α-amylase with novel domain organization was isolated form Bacillus spAAH31 (Saburi et al. 2013). Although this α-amylase lacks hydrolytic activity towards pullulan, the enzyme has a catalytic domain similar to neo-pullulanase-like α-amylase with a central region similar to them (Gly395-Asp689). In addition to this, it also has an N-terminal carbohydrate-binding module like domain CBM20, which helps in the substrate binding. As alkaliphilic α-amylases are extensively used in the detergent industry, it is rational to dissect the mechanism of their stability in alkaliphilic environment. Presently, there are limited numbers of studies which have focused on the stability of alkaliphilic α-amylases. Thus, factors which determine their stability are still not well understood. Mutational studies, particularly role of arginine, are required in order to deduce their contribution on alkaliphilic adaptations. Preference of positively charged arginine over another positively charged lysine is another point which needs further investigation. Further, detergent enzyme interactions are required in enzyme industry.

Amino acid sequence analysis of selected α-amylases

In our sequence analysis, the relative compositions of amino acid residues which affect stability and folding like proline, glycine, positively and negatively charged residues, histidine, and cystine from each class of α-amylases have been obtained through computation using the Expasy-ProtParam program (Gasteiger et al. 2005). The proline content in thermophilic (BSTA) and hyperthermophilic (PWA) alpha amylases are 4.7 and 4.6% respectively which is greater than the mesophilic (BAA) α-amylase which has only 3.7%. Although α-amylases with thermophilic-like properties (BLA) have less proline content than the mesophilic α-amylase (BAA), this factor in BLA is compensated by the presence of a higher number of histidine than BAA (Machius et al. 1995). The psychrophilic (AHA) α-amylase has only 2.9% proline (Table 2). As proline increases the rigidity and thus enhances the stability of proteins, the presence of either higher or lower proline content seems a plausible adaptation in thermophilic and psychrophilic α-amylases respectively (Cavicchioli et al. 2011). AHA has 1.8% cysteine, which forms four intradomain disulfide bonds including two disulfide bonds in domain A, one in B, and one in C. Compared to AHA, an extra disulfide bond between Cys70 and Cys115 connecting domains A and B was observed in mesophilic pig α-amylases. Thus, a lack of this disulfide bond in the AHA may provide greater flexibility around the active site which helps it to work at low temperatures (Aghajari et al. 1998). Like proline, glycine also acts to control the flexibility of proteins in an opposite way to proline: the higher the glycine content in the loop region, the greater the flexibility and thus lower the thermal stability (Tronelli et al. 2007). Among all the α-amylases discussed here, the lowest glycine content (6.8%) was observed in hyperthermophilic PFTA, which may contribute to its enhanced thermal adaptation while the highest glycine (10.3%) content was also observed in a hyperthermophilic α-amylase (PWA). This factor in PWA might be compensated by the presence of disulfide bonds. The relative content of charged residues (Asp + Glu + Arg + Lys) in α-amylases from different classes is similar, i.e., the mesophilic α-amylases BAA and BHA both have 23.4 and 21.2% respectively; however, their relative distribution in the protein structure is different and this factor may be critically important (Alikhajeh et al. 2010; Lyhne-Iversen et al., 2006). Acidophilic (ABA) and alkaliphilic (AmyK38 and AmyK1378) α-amylases have 20.6, 20.6, and 20% charged residues respectively. Similarly, thermophilic (BSTA), halophilic (HOA), and hyperthermophilic (PWA) have charged residues 21.4, 25.3, and 20.5 respectively. The maximum number of charged residues is present in PFTA (28.4%) which indicates a dominant contribution of electrostatic interactions in its thermal stabilization. Besides this, the lowest amounts of charged residues were observed in psychrophilic α-amylase (AHA) (16.2%) (Aghajari et al. 1998; Siddiqui et al. 2005a). The amino acid sequence analysis provides the information about the adaptive preference of selected amino acid residues in different extremophilic α-amylases.

Table 2.

Amino acid composition of α-amylases with known structures from different classes of microorganisms

| α-Amylase | Class | pI | Proline (%) | Glycine (%) | Charged residues | Cysteine (%) | Histidine (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAA | Mesophilic | 5.31 | 3.70 | 9.30 | 24.20 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| BHA | Mesophilic | 5.72 | 3.50 | 9.40 | 21.20 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| AHA | Psychrophilic | 4.82 | 2.90 | 9.90 | 16.10 | 1.8 | 2.6 |

| BLA | Thermophilic | 6.05 | 3.10 | 9.50 | 22.77 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| BSTA | Thermophilic | 5.61 | 4.70 | 8.90 | 21.40 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| PFTA | Hyperthermophilic | 8.89 | 3.40 | 6.80 | 28.21 | 0.2 | 2.6 |

| PWA | Hyperthermophilic | 4.82 | 4.60 | 10.30 | 20.45 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| AmyA | Halophilic | 5.35 | 5.10 | 8.80 | 25.20 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| ABA | Acidophilic | 5.18 | 2.90 | 10.30 | 17.56 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| AmyK38 | Alkaliphilic | 4.52 | 2.70 | 9.80 | 21.66 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| AmyK1378 | Alkaliphilic | 6.31 | 3.30 | 10.10 | 20.00 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

Note: Amino acid sequences of α-amylases for protparameter analysis have been obtained from their respective PDB sources

Although such amino acid content information is not a conclusive sign of an adaptive feature, it may also vary from protein to protein within the class; for example, disulfide bonds play an important role in thermal stability of PWTA, while no such role was observed in PWA. Therefore, to understand the differential stability among different extremozymes, information from the kinetics of unfolding is required.

Summary and conclusions

This review has discussed microbial α-amylases from different extremophilic classes with specific reference to their acquired molecular adaptations that allow them to remain functional. This information provides an introduction to the type adaptations of α-amylases associated with the different classes of extremophiles and highlights the importance of structure, stability, and folding studies on understanding this industrially important class of enzyme. To remain functional at low temperature, psychrophilic α-amylase adjusts its stability and flexibility (Cavicchioli et al. 2011; Feller 2013). Salient features of the most studied psychrophilic α-amylase (AHA) are low proline content in loop regions, high glycine content, low arginine content, less hydrophobic residues, and a relatively low number of charged residues such as arginine and lysine (Table 2). Furthermore, we have reviewed evidence that the active site of psychrophilic α-amylase (AHA) showed lower stability and higher flexibility (Siddiqui et al. 2005a; D’ Amico et al. 2006). Molecular adaptations of psychrophilic α-amylases depend on the interplay of activity, flexibility, and stability (Sanchez 2010; Feller 2013). Contrary to psychrophilic α-amylases, thermophilic α-amylases exhibit a higher number of ionic interactions and increased hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions in protein core enhance enzyme rigidity (Machius et al. 1995; Jaenicke and Böhm 1998; Linden and Wilmanns 2004; Ahmad and Mishra 2020). The thermophilic-like α-amylase, BLA, shows an increased hydrophobicity of its protein core due to presence of additional histidine as compared to its mesophilic counterparts (BAA) (Machius et al. 1995). Hyperthermophilic α-amylases also show unique features like the presence of additional zinc ion-binding sites in PWA and PFTA, disulfide bonds in PWA, and unique domain organization in PFTA which may help to retain its native conformation at extreme temperature (> 110 °C) (Linden et al. 2003; Machius et al. 2003). Similar to other halophilic proteins, halophilic α-amylase (AmyA) has a high content of charged residues (Sivakumar et al. 2006; Sanchez 2010) (Table 2). However, unlike other halophilic proteins, halophilic α-amylase (AmyA) lacks acidic residues at the protein surface which might be compensated by oligomerization which helps in the stabilization of AmyA in halophilic environment (Sivakumar et al. 2006; Sanchez 2010). As per amino acid sequence information, acidophilic proteins have increased content of acidic residues (Sanchez 2010) while acidophilic α-amylase with known crystal structure (ABA) possesses acidic residues comparable to that of mesophilic α-amylase (BAA) (Sivakumar et al. 2006; Alikhajeh et al. 2010; Sanchez 2010). Additional hydrogen bonds near active site of acidophilic α-amylase might be considered as an adaptive feature, but due to limited structural information on this class, it cannot be generalized. The amino acid sequence and crystal structure of alkaliphilic α-amylase from AmyK38 showed a loss of the acidic residues relative to thermophilic BLA (Nonaka et al. 2003) while AmyK1378 showed a gain of Arg-Asp/Glu pair at the cost of Lys-Asp/Glu pair. Finally, it can be concluded that temperature adaptation in thermophilic and hyperthermophilic α-amylases is mainly controlled by high hydrophobicity of protein core, increased number of salt bridges, H bonding, and metal ion binding. Unlike this, pH adaptations in microbial α-amylases arise due to the preference of one type of amino acid over others. Acidic residues are preferred more in acidophilic and basic residues in alkaliphilic α-amylases. Similar to the thermophilic α-amylases, H bonding is also involved in pH adaptation. In halophilic α-amylases, charge residues are preferred as they bind more salt and thus help in halophilic adaptation. Besides this, oligomerization of protein at high salt concentration is also an adaptation in halophilic α-amylases. It has been observed that halophilic, acidophilic, and alkaliphilic adaptations in α-amylases can also provide thermophilic adaptation. Thus, these groups of α-amylases share certain common features like increased hydrogen bonding, hydrophobicity, and ionic interactions. This indicates the evolutionary relatedness among these α-amylases.

Future perspectives

For gaining a detailed understanding of the molecular determinants of protein stability in different extremophilic microbial α-amylases, there is a need for more atomic resolution structures. Static information obtained from amino acid sequence and atomic resolution structures is a prerequisite for understanding molecular adaptation; however, a complete understanding may not be possible without additional dynamic studies. Given the huge industrial importance of this class of enzymes, protein folding-unfolding studies in different denaturants are required to understand thermodynamic and kinetic stability. Further studies on the reversibility of protein folding, the kinetics of unfolding-refolding, and the determination of their rate constants may shed light on the molecular adaptation of this class of enzyme. The role of extremolytes in molecular adaptation also needs to be explored. Further, comparative proteomic analysis of molecular chaperones, peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPI), and protein disulfide isomerases (PDI) are required to understand the role of these helper proteins and the enzymes in the stability and folding of various extremophilic α-amylases.

Author contribution

R.M. conceptualized and outlined the review. A.A. and R.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Rahamtullah compared structures using PyMol program and all three authors finalized the manuscript.

Funding

The work on stability and folding in RM laboratory is supported by University Grants Commission (MAJOR-BIOT-2013–32040). Aziz Ahmad is supported by UGC and Rahamtullah is supported by DBT fellowship.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aghajari N, Feller G, Gerday C, Haser R. Structures of the psychrophilic Alteromonas haloplanctis alpha-amylase give insights into cold adaptation at a molecular level. Structure. 1998;6:1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agirre J, Moroz O, Meier S, Brask J, Munch A, Hoff T, Andersen C, Wilson KS, Davies GJ. Structure of the AliC GH13 α-amylase from Alicyclobacillus sp. reveals the accommodation of starch branching points in the α-amylase family. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2019;75:1–7. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318014900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Mishra R. Differential effect of polyol and sugar osmolytes on the refolding of homologous alpha amylases: a comparative study. Biophys Chem. 2022;281:106733. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2021.106733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Mishra R. Different unfolding pathways of homologous alpha amylases from Bacillus licheniformis (BLA) and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (BAA) in GdmCl and urea. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;159:667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghanayem AA, Joseph B. Current prospective in using cold-active enzymes as eco-friendly detergent additive. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104(7):2871–2882. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhajeh J, Khajeh K, Ranjbar B, Naderi-Manesh H, Lin YH, Liu E, Guan HH, Hsieh YC, Chuankhayan P, Huang YC, Jeyaraman J, Liu MY, Chen C. Structure of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens alpha amylase at high resolution: implications for thermal stability. Acta Cryst Sec F. 2010;66:121–129. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhajeh J, Khajeh K, Naderi-Manesh M, Ranjbar B, Sajedi RH, Naderi-Manesh H. Kinetic analysis, structural studies and prediction of pKa values of Bacillus KR-8104 a-amylase: the determinants of pH-activity profile. Enzym Microbiol Technol. 2007;41:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2007.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anfinsen CB. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa T, Yamaguchi R, Tokunaga H, Tokunaga M. Unique features of halophilic proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(1):65–71. doi: 10.2174/1389203717666160617111140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averhoff B, Müller V. Exploring research frontiers in microbiology: recent advances in halophilic and thermophilic extremophiles. Res Microbiol. 2010;161(6):506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovsky IN, Shakhnovich EI (2005) Physics and evolution of thermophilic adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 12742-7. 10.1073/pnas.0503890102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brininger C, Spradlin S, Cobani L, Evilia C. The more adaptive to change, the more likely you are to survive: protein adaptation in extremophiles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;84:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogin O, Peretz M, Hacham Y, Korkhin Y, Frolow F, Kalb (Gilboa) AJ, Burstein Y (1998) Enhanced thermal stability of Clostridium beijerinckii alcohol dehydrogenase after strategic substitution of amino acid residues with prolines from the homologous thermophilic Thermoanaerobacter brockii alcohol dehydrogenase. Protein Sci 7(5):1156–1163. 10.1002/pro.5560070509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brosnan MP, Kelly CT, Fogarty WM. Maltogenic amylases of Bacillus stearothermophilus. BiochemSoc Trans. 1990;18:311–312. doi: 10.1042/bst0180311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I, Dafforn TR, Fryer PJ, Cox PW. Kinetic study of the thermal denaturation of a hyperthermostable extracellular α-amylase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:2600–2605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canganella F, Wiegel J. Anaerobic thermophiles. Life (basel) 2014;4(1):77–104. doi: 10.3390/life4010077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L, Zoldák G, Schmid FX, Sterner R. Folding mechanism of an extremely thermostable (βα)(8)-barrel enzyme: a high kinetic barrier protects the protein from denaturation. Biochemistry. 2012;51(16):3420–3432. doi: 10.1021/bi300189f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli R, Charlton T, Ertan H, Mohd Omar S, Siddiqui KS, Williams TJ. Biotechnological uses of enzymes from psychrophiles. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty D, Khan MF, Patra S. Multifactorial level of extremostability of proteins: can they be exploited for protein engineering? Extremophiles. 2017;21(3):419–444. doi: 10.1007/s00792-016-0908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Luo Z, Lu M, Gao S, Wang S. The hyperthermophilic α-amylase from Thermococcus sp. HJ21 does not require exogenous calcium for thermostability because of high-binding affinity to calcium. J Microbiol. 2017;55(5):379–387. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi MC, Wu TJ, Chuang TT, Chen HL, Lo HF, Lin LL. Biophysical characterization of a recombinant α-amylase from thermophilic Bacillus sp strain TS-23. Protein J. 2010;29(8):572–82. doi: 10.1007/s10930-010-9287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi MC, Wu TJ, Chen HL, Lo HF, Lin LL. Sorbitol counteracts temperature- and chemical-induced denaturation of a recombinant α-amylase from alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. TS-23. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;12:1779–1788. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla A, D'Amico S, Barumandzadeh R, Matagne A, Feller G. Stepwise adaptations to low temperature as revealed by multiple mutants of psychrophilic α-amylase from Antarctic bacterium. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(44):38348–38355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón W, Church J, Sen J, Thibeault J, Trasatti H, Xia K. Biological roles of protein kinetic stability. Biochemistry. 2017;56(47):6179–6186. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronado M, Vargas C, Hofemeister J, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Production and biochemical characterization of an alpha-amylase from the moderate halophile Halomonas meridiana. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;183:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico S, Sohier JS, Feller G. Kinetics and energetics of ligand binding determined by microcalorimetry: insights into active site mobility in a psychrophilic alpha-amylase. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:1296–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico S, Gerday C, Feller G. Temperature adaptation of proteins: engineering mesophilic-like activity and stability in a cold-adapted alpha-amylase. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmaso GZ, Ferreira D, Vermelho AB. Marine extremophiles: a source of hydrolases for biotechnological applications. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(4):1925–1965. doi: 10.3390/md13041925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck N, Machius M, Wiegand G, Huber R, Gaillardin C. Probing structural determinants specifying high thermostability in Bacillus licheniformis alpha amylase. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1041–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza PM, de Oliveira MP. Application of microbial α-amylase in industry—a review. Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:850–861. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-García M, Valdivia-Urdiales B, Aguilar-González CN, Contreras-Esquivel JC, Rodríguez-Herrera R. Halophilic hydrolases as a new tool for the biotechnological industries. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92(13):2575–2580. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakar K, Pandey A. Wide pH range tolerance in extremophiles: towards understanding an important phenomenon for future biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(6):2499–2510. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobnak I, Vesnaver G, Lah J. Model-based thermodynamic analysis of reversible unfolding processes. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(26):8713–8722. doi: 10.1021/jp100525m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumorné K, Córdova DC, Astorga Eló M, Renganathan P. Extremozymes: a potential source for industrial applications. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27:649–659. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1611.11006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleuche S, Schröder C, Sahm K, Antranikian G. Extremozymes biocatalysts with unique properties from extremophilic microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;29:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq MA, Ali S, Hassan A, Tahir HM, Mumtaz S, Mumtaz S. Biosynthesis and industrial applications of α-amylase: a review. Arch Microbiol. 2021;203(4):1281–1292. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-02128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G. Molecular adaptations to cold in psychrophilic enzymes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:648–662. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2155-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G. Psychrophilic enzymes: from folding to function and biotechnology. Scientifica (cairo) 2013;2013:512840. doi: 10.1155/2013/512840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G. Protein folding at extreme temperatures: current issues. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;84:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G, d'Amico D, Gerday C. Thermodynamic stability of a cold-active alpha-amylase from the Antarctic bacterium Alteromonas haloplanctis. Biochemistry. 1999;38(14):4613–4619. doi: 10.1021/bi982650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G, Lonhienne T, Deroanne C, Libioulle C, Van Beeumen J, Gerday C. Purification, characterization, and nucleotide sequence of the thermolabile alpha-amylase from the Antarctic psychrotroph Alteromonas haloplanctis A23. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5217–5221. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42754-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller G, Payan F, Theys F, Qian M, Haser R, Gerday C. Stability and structural analysis of alpha-amylase from the antarcticpsychrophile Alteromonas haloplanctis A23. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science: a guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fitter J. Structural and dynamical features contributing to thermostability in alpha-amylases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(17):1925–1937. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5079-2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitter J, Haber-Pohlmeier S. Structural stability and unfolding properties of thermostable bacterial alpha-amylases: a comparative study of homologous enzymes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9589–9599. doi: 10.1021/bi0493362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinami S, Fujisawa M. Industrial applications of alkaliphiles and their enzymes past, present and future. Environ Technol. 2010;31:845–856. doi: 10.1080/09593331003762807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker JM (ed) The proteomics protocols handbook, Springer Protocol Handbooks. Humana Press. 10.1385/1-59259-890-0:571

- Goldenzweig A, Fleishman SJ. Principles of protein stability and their application in computational design. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87:105–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Fu L, Pan A, Gui Y, Zhang Q, Li J. Multifunctional alkalophilic α-amylase with diverse raw seaweed degrading activities. AMB Express. 2021;11(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s13568-021-01300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara H, Igarashi K, Hayashi Y, Endo K, Ikawa-Kitayama K, Ozaki K, Kawai S, Ito S. Novel alpha-amylase that is highly resistant to chelating reagents and chemical oxidants from the alkaliphilic Bacillus isolate KSM-K38. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1744–1750. doi: 10.1128/aem.67.4.1744-1750.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JP, Gheeraert N, Tsigelnitskiy D, Cockell CS. The limits for life under multiple extremes. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(4):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiteshi K, Gupta R. Thermal adaptation of α-amylases: a review. Extremophiles. 2014;18(6):937–944. doi: 10.1007/s00792-014-0674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi K (1999) Alkaliphiles: some applications of their products for biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63:735–750. 10.1128/MMBR.63.4.735-750.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hough DW, Danson MJ. Extremozymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug LA, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Probst AJ, Castelle CJ, Butterfield CN, Hernsdorf AW, Amano Y, Ise K, Suzuki Y, Dudek N, Relman DA, Finstad KM, Amundson R, Thomas BC, Banfield JF. A new view of the tree of life. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16048. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon GW, Vasisht N, Bolhuis A. Characterisation of a highly stable alpha-amylase from the halophilic archaeon Haloarcula hispanica. Extremophiles. 2005;9:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiye T. Enzymes from piezophiles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;84:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Hatada Y, Hagihara H, Saeki K, Takaiwa M, Uemura T, Ara K, Ozaki K, Kawai S, Kobayashi T, Ito S. Enzymatic properties of a novel liquefying alpha-amylase from an alkaliphilic Bacillus isolate and entire nucleotide and amino acid sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3282-3289.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke R. Protein stability and molecular adaptation to extreme conditions. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:715–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke R, Böhm G. The stability of proteins in extreme environments. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8(6):738–748. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeček Š, Gabriško M. Remarkable evolutionary relatedness among the enzymes and proteins from the α-amylase family. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(14):2707–2725. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeček Š, Svensson B. Amylolytic glycoside hydrolases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(14):2601–2602. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeček Š, Svensson B, MacGregor EA. α-Amylase: an enzyme specificity found in various families of glycoside hydrolases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:1149–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeček Š, Zámocká B. A new GH13 subfamily represented by the α-amylase from the halophilic archaeon Haloarcula hispanica. Extremophiles. 2020;24(2):207–217. doi: 10.1007/s00792-019-01147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Gai Y, Guo X, Hou Y, Zeng R. Properties and applications of extremozymes from deep-sea extremophilic microorganisms: a mini review. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(12):656. doi: 10.3390/md17120656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen S, Vorgias CE, Antranikian G (1997) Cloning, sequencing, characterization, and expression of an extracellular alpha-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 16335-42. 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16335 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kikani BA, Singh SP (2021) Amylases from thermophilic bacteria: structure and function relationship. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1-17. 10.1080/07388551.2021.1940089 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koch R, Spreinat A, Lemke K, Antranikian G. Purification and properties of a hyperthermoactive α-amylase from the archaeobacterium Pyrococcus woesei. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:572–578. doi: 10.1007/BF0024535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koch R, Zablowski P, Spreinat A, Antranikian G. Extremely thermostable amylolytic enzyme from the archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03792.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Alam A, Tripathi D, Rani M, Khatoon H, Pandey S, Ehtesham NZ, Hasnain SE. Protein adaptations in extremophiles: an insight into extremophilic connection of mycobacterial proteome. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;84:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Khare SK (2015) Chloride activated halophilic α-amylase from Marinobacter sp. EMB8: production optimization and nanoimmobilization for efficient starch hydrolysis. Enzyme Res.:859485. 10.1155/2015/859485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]