Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the existence and degree of the health disparities in the treatment of pediatric patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) based on sociodemographic factors.

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study at a large academic medical center including children ages 5–18 years old diagnosed with SVT. Patients with congenital heart disease and myocarditis were excluded. Initial treatment and ultimate treatment with either medical management or ablation were determined. The odds of having an ablation procedure were determined based on patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance status.

Results:

There was a larger portion of non-White patients (p=0.033) within the cohort that did not receive an ablation during the study period. Patients that were younger, female, American Indian/Alaskan Native, unknown race, and had missing insurance information were less likely to receive ablation therapy during the study period.

Conclusion:

In this single center, regional evaluation, we demonstrated that disparities in the treatment of pediatric SVT are present based on multiple patient sociodemographic factors. This study adds evidence to the presence of inequities in health care delivery across pediatric populations.

Keywords: Health Equity, Race and Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, Supraventricular Tachycardia, Pediatric Cardiology

Introduction

In the United States, there are disparities of health and wellness as a function of race, ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status[1]. A health disparity is defined as any difference in disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality in a specific population when compared to another population. Children are not immune to these disparities, and disparities are present in many pediatric conditions such as obesity, asthma, infant mortality, and prematurity [2], [3].

Disparities in outcomes of children with congenital heart disease also exist. Infants with severe congenital heart disease born to mothers who have public insurance or do not have any insurance have increased mortality when compared to infants with private insurance[4]. Disparities due to race are the most well-described type in congenital heart disease. Studies have shown increased mortality among non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients for a variety of congenital heart defects across a variety of age groups [4]–[10]. Additional studies looking at the effect of patient ethnicity have shown an increased risk of mortality among Hispanic patients with congenital heart disease [6], [7].

While there are demonstrated health disparities in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease, there are no data to determine if similar disparities exist in the treatment of pediatric arrhythmias. Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is the most common arrhythmia of childhood, affecting up to 0.4% of children [11]. Treatment options for SVT include observation alone, medical therapy, or catheter ablation [12]. Medication can be very effective in preventing recurrences of SVT, but can affect quality of life due to the need to be taken daily and potential medication side effects. Catheter ablation is an invasive procedure with a very high success rate at achieving a permanent cure to SVT with success rates typically reported at > 95% [13]–[15]. In pediatric patients, the procedure is typically only performed at pediatric cardiac centers and children’s’ hospitals, often after a complex referral process, which may limit access for some patients. Since there are both non-invasive and invasive approaches to the treatment of SVT in pediatric patients, each with a unique risk/benefit balances and different barriers to treatment, there is risk of sociodemographic bias. In this study, we investigated if disparities exist in the modality of treatment of pediatric SVT based on age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance status.

Methods

Study Population

We identified all patients 5–18 years of age assessed in the Duke University Health System (both inpatient and outpatient) with confirmed supraventricular tachycardia between January 1, 2000 and January 1, 2018. Supraventricular tachycardia was confirmed if it was documented by electrocardiogram (ECG), ambulatory event monitor, or electrophysiology (EP) study. We excluded patients with congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis. Patients with missing outcome data (type of SVT treatment) and those less than five years of age at the time of diagnosis were excluded. Those less than five years of age were excluded as ablation would not be standard of care for these patients. This study was approved by Duke Health Institutional Review Board and did not require consent.

Study Design

This was a single center, retrospective cohort study. Patient demographics were extracted from the electronic health record using DEDUCE (Duke Enterprise Data Unified Content Explorer). Clinical data were obtained via chart review. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Duke University.

Study Variables

Based on electronic health record registration data, patient race was categorized as one of the following: White, Black, Asian/ Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, 2 or more races, other or unknown. Ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. Insurance status was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES). The insurance type at the time of the encounter was obtained from the patient’s chart and classified as public, private (including commercial and employer-based), uninsured, or missing.

Date of initial symptoms was recorded based on patient report within provider documentation. Date of diagnosis was obtained by documentation of ECG, ambulatory ECG, or EP study positive for SVT. Initial type of treatment that patient received after diagnosis of SVT was determined by chart review of provider notes. Initial treatment was classified as medical management, ablation, or no treatment. Whether or not the patient ultimately received an ablation at some point during the study period was determined by a review for documentation for an ablation procedure.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics were described by treatment group. Fisher’s exact test (patient sex, insurance status) or chi-square test (all other variables) were used for comparison of categorical characteristics between groups. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparisons of continuous characteristics between groups. Odds ratios were calculated for each association between potential risk factor (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance status) and ultimate ablation treatment. Adjusted odds ratios were obtained using multiple logistic regression models, with potential risk factors as predictors and ablation versus medical treatment or no treatment as outcomes. These potential risk factors included age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance type. Data analysis was performed using SAS software (SAS version 9.4).

Results

From initial sample 1,128 patients were found to have documented SVT. Patients were excluded for age < 5 years old (n=181) or >18 years old (n=18), missing diagnosis date (n=292) or incomplete data (n=2). During the study period, 635 patients were found to meet inclusion criteria as above. Mean age at diagnosis was 12.8 years (Table 1). Males accounted for 48.0% of patients (n=305) and females accounted for 52.0% (n=330). The racial make-up of the cohort was 67.9% White (n=431), 15.9% Black (n=101), 1.3% Asian/ Pacific Islander (n=8), 1.7% American Indian/ Alaskan Native (n=11), 3.3% two or more races (n=21), 4.9% other race (n=31), and 5.0% unknown (n=32). Hispanic patients made up 3.3% of patients (n=21). Patients with public insurance made up 18.0% (n= 110/594) of the cohort while 43.4% of patient had private insurance (n=258/594). Insurance information was missing for 37.5% of patients (n=223/594).

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Patients with SVT

| Characteristic | Patients (N=635) |

|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 12.8 (3.5) |

| Sex, % (n) | |

| Male | 48.0 (305) |

| Female | 52.0 (330) |

| Race, % (n) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1.7 (11) |

| Asian/ Pacific Islander | 1.3 (8) |

| Black | 15.9 (101) |

| White | 67.9 (431) |

| Two or more races | 3.3 (21) |

| Other | 4.9 (31) |

| Unknown | 5.0 (32) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | |

| Hispanic | 3.3 (21) |

| Non-Hispanic | 96.7 (614) |

| Insurance Type, % (n) | |

| Public | 18.5 (110/594) |

| Private | 43.4 (258/594) |

| Uninsured | 0.5 (3/594) |

| Missing | 37.5 (223/594) |

| Initial Type of treatment, % (n) | |

| Ablation | 43.8 (277) |

| Medical Therapy | 41.6 (263) |

| No Treatment | 12.2 (77) |

| Unknown | 2.4 (15) |

| Received Ablation, n (%) | 510 (81.9) (510) |

Initial Treatment of SVT

There were 277 patients (43.8%) who received ablation therapy as initial SVT treatment (Table 2). There were 263 patients (41.6%) who received pharmacologic therapy as initial SVT treatment. The remainder of the patients had no treatment or unknown initial type of treatment. Those who had an ablation were older compared to the medical management group (13.3 years vs 12.3 years, p=0.001). There was no difference in the sex, race, ethnicity, or insurance status to medical center in ablation versus medical therapy or no treatment for the initial treatment.

Table 2.

Demographics stratified by initial type of SVT treatment during the study period.

| Ablation (N=277) | Medical therapy (N=263) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 13.3 (3.4) | 12.3 (3.6) | 0.001 |

| Sex, % (n) | 0.085 | ||

| Male | 50.2 (139) | 42.6 (112) | |

| Female | 49.8 (138) | 57.4 (151) | |

| Race, % (n) | 0.140 | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.4 (1) | 3.0 (8) | |

| Asian/ Pacific Islander | 1.8 (5) | 0.8 (2) | |

| Black or African American | 15.5 (43) | 12.5 (33) | |

| White | 68.2 (189) | 68.4 (180) | |

| Multiracial | 3.6 (10) | 3.0 (8) | |

| Other | 4.3 (12) | 6.8 (18) | |

| Unknown | 6.1 (17) | 5.3 (14) | |

| Hispanic, %, n | 3.6 (9/249) | 3.0 (7/232) | 0.715 |

| Insurance, % (n) | |||

| Public | 29.8 (48/161) | 28.3 (43/152) | 0.323 |

| Private | 68.3 (110/161) | 71.7 (109/152) | |

| Distance to Hospital (miles), mean, SD | 81.3 (93.7) | 88.2 (112.5) | 0.303 |

Values presented are counts (%) for categorical variables or median(IQR) for continuous variables. p-Values derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, Fisher exact test for dichotomous variables, and chi-square test for categorical variables

Ablation of SVT During the Study Period

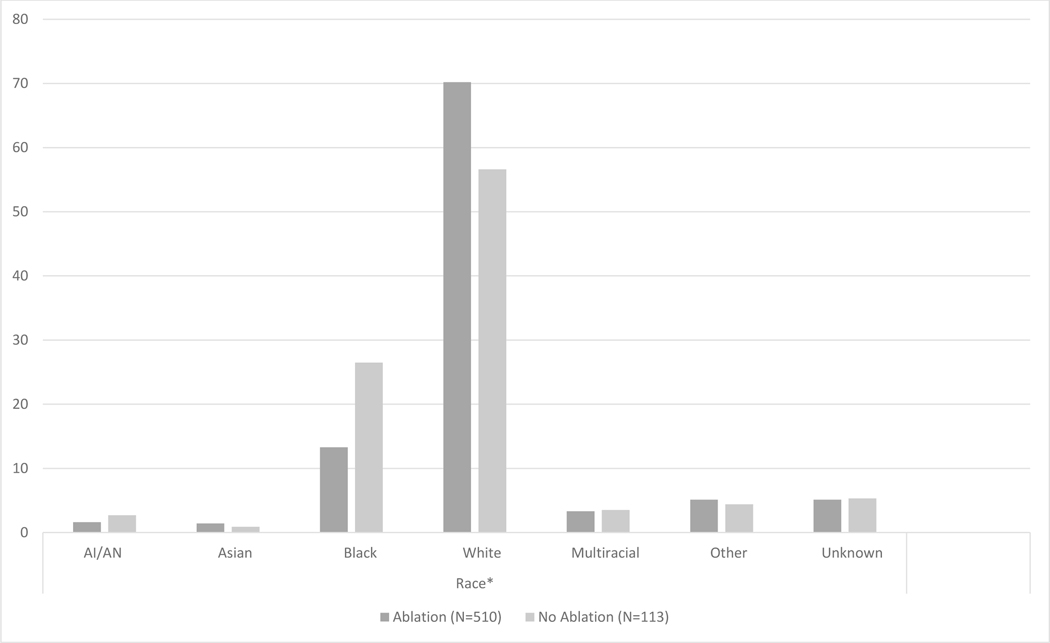

Overall, 81.9% of patients received an ablation (n= 510) during the study period (Table 3). There were 113 patients that did not receive an ablation at any time during the study period. There were 11 patients that did not have documentation on whether they ultimately received an ablation which were excluded. The mean age was higher in the patients that received an ablation at any time during the study period compared to those that did not receive an ablation at any time during the study period (12.9 years vs 12.1 years, p=0.017). There was a difference in the cohort of patients who received an ablation based on race: more White patients received ablation therapy during the study period than other racial groups (Figure 1, p=0.033). There was no difference in the number of patients ultimately receiving an ablation based on sex, ethnicity, or insurance status.

Table 3.

Demographics stratified by final type of SVT treatment during the study period.

| Characteristic | Ablation (N=510) | No Ablation (N=113) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean, SD | 12.9 (3.5) | 12.1 (3.6) | 0.017 |

| Sex, % (n) | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 48.2 (246) | 47.8 (54) | |

| Female | 51.8 (264) | 52.2 (59) | |

| Race, % (n) | 0.033 | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1.6 (8) | 2.7 (3) | |

| Asian | 1.4 (7) | 0.9 (1) | |

| Black or African American | 13.3 (68) | 26.5 (30) | |

| White | 70.2 (358) | 56.6 (64) | |

| Multiracial | 3.3 (17) | 3.5 (4) | |

| Other | 5.1 (26) | 4.4 (5) | |

| Unknown | 5.1 (26) | 5.3 (6) | |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | 0.491 | ||

| Hispanic | 3.1 (16) | 4.4 (5) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 96.9 (494) | 95.6 (108) | |

| Insurance, % (n) | |||

| Public | 27.9 (79/283) | 36.3 (30/82) | 0.276 |

| Private | 71.0 (201/283) | 63.4 (52/82) | |

| Uninsured | 1.1 (3/283) | 0 (0/82) | |

| Distance to Hospital (miles), mean, SD | 86.5 (101.4) | 58.6 (84.3) | <0.001 |

Values presented are counts (%) for categorical variables or median(IQR) for continuous variables. p-Values derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, Fisher exact test for dichotomous variables, and chi-square test for categorical variables

Figure 1.

Race stratified by final type of SVT treatment during the study period.

Unadjusted odds ratio of having an ablation during the study period were not significant for patient sex, race, ethnicity (Table 4). When adjusting ORs for candidate risk factors (Table 5), patients that were older had an increased likelihood of receiving an ablation (OR 1.145, 95% CI 1.043, 1.256). Female patients had decreased odds of having an ablation (OR 0.374, 95% CI 0.176, 0.795). Patients who were American Indian/ Alaskan Native (OR 0.138, 95% CI 0.024, 0.784) and unknown race (0.011, 95% CI <0.001, 0.307) were also less likely to have an ablation during the study period. Differences in ablation based on race were attenuated when adding insurance status to the model.

Table 4.

Unadjusted Odds Ratio of receiving ablation therapy during the study period.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age | 0.901 (0.833, 0.975) |

| Sex | 1.830 (0.996, 3.362) |

| Race | |

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native | 3.557 (0.713, 17.735) |

| Asian | - |

| Black or African American | 1.843 (0.854, 3.976) |

| White/ Caucasian | Ref |

| Multiracial | 0.721 (0.093, 5.597) |

| Other | 2.477 (0.885, 6.935) |

| Unknown | 2.381 (0.853, 6.647) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanc v Non-Hispanic) | 0.659 (0.085, 5.077) |

| Insurance (Public v private) | 1.717 (0.853, 3.459) |

| Distance | 1.000 (0.997, 1.003) |

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds Ratio of receiving ablation therapy during the study period.

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR*1 (95% CI) | Adjusted OR*2 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (1 year) | 1.145 (1.043, 1.256) | 1.143 (1.036, 1.260) |

| Sex (Female v Male) | 0.374 (0.176, 0.795) | 0.452 (0.207, 0.987) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native | 0.138 (0.024, 0.784) | 0.182 (0.029, 1.136) |

| Asian | - | - |

| Black or African American | 0.482 (0.210, 1.108) | 0.621 (0.250, 1.542) |

| White/ Caucasian | Ref | Ref |

| Multiracial | 0.931 (0.112, 7.725) | 2.129 (0.232, 19.647) |

| Other | 0.217 (0.032, 1.459) | 0.275 (0.037, 2.061) |

| Unknown | 0.011 (<0.001, 0.307) | - |

| Ethnicity | 6.006 (0.421, 85.711) | 2.149 (0.159, 0.896) |

| Insurance | - | |

| Private | - | Ref |

| Missing | - | 0.377 (0.159, 0.896) |

| Public | - | 1.736 (0.689, 4.377) |

1Adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity

2 Adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance

Discussion

There is significant evidence that sociodemographic factors affect congenital heart disease outcomes, and we have now determined they also play a role in pediatric arrhythmia treatment. Age, sex, and race affect a pediatric patient’s likelihood of receiving ablation therapy for the treatment of SVT. Patients that were older and male were more likely to ultimately have an ablation. In this study, we showed that patients who underwent ablation therapy were more likely to be White compared to other races. Patients identified as American Indian/ Alaskan Native or those with an unknown race were significantly less likely to receive an ablation during the study period. It is likely that this unknown group has a heterogenous make-up.

Race/ Ethnicity

We found a larger portion of races other than White in patients who did not receive an ablation during the study period. American Indian/ Alaskan Native patients have decreased odds of receiving ablation therapy for SVT in adjusted analysis. These findings are similar to other pediatric studies showing that patients identifying as a race other than White are less likely to receive specific treatments such as pain medication or ADHD medications [16], [17]. Similar disparities exist in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease with Black patients consistently experiencing poorer outcomes compared to their White peers[6], [18]. These differences may represent differential access to care which have been seen in other pediatric conditions and may also be a function of patient family income, neighborhood residency, access to transportation, and insurance status [19]. Interestingly, this investigational cohort has an under representation of Black patients in the cohort compared to the state population from which most patients are seen (15.9% vs 22.2%) [20]. This suggests that Black patients may be referred to subspecialty care at this tertiary care center with less frequency than their White peers with SVT, a phenomena which has been seen in other pediatric conditions [21], [22].

Another cause of these observed differences may be patient and parent preference for one treatment over the other. Parents may have different expectations of what treatment for their child’s SVT should look like. There may be different levels of trust in the medical system based on past discrimination and racism that make some groups less likely to choose a more invasive procedure like an ablation [23]. Provider perceptions may also play a role in these differences. If patients and families seem reluctant for ablation procedure, providers may not fully explain its benefits. Implicit provider bias may also change the way that treatment options are presented.

We did not observe any differences in the likelihood of receiving ablation therapy based on Hispanic ethnicity. This cohort was made up of only 3.3% Hispanic patients which is less than the overall state make-up of 9.8% and may again represent differences in referral pattern based on ethnicity that is similarly seen in race [20].

Socioeconomic status

Prior studies of disparities in pediatric congenital heart disease have shown mixed outcomes on the effect of insurance status, used as an indicator of SES, on mortality in pediatric patients [6], [24]–[28]. In this study, we also used insurance type as a surrogate for SES to compare the likelihood of receiving ablation and did not find a difference. The use of insurance status as a single indicator of SES may not accurately represent the social and financial barriers that patients might face in obtaining ablation therapy. Family income or a more robust SES score that includes education level, occupational status, and measures of wealth may more accurately represent a patient’s true socioeconomic status.

Interestingly, in our cohort of patients for this study, only 18.5% had public insurance. This is significantly less than the 41.5% of children in our state that received Medicaid in 2018 [29]. Similar to race and ethnicity, this finding may represent the fact that patients with public insurance are less likely to be referred for ablation therapy or seek out this treatment due to socioeconomic challenges associated with ultimately obtaining an ablation procedure, such as missed worked, transportation, or additional financial costs.

Limitations

This study is a single-center, retrospective study and similar disparities may or may not exist at other centers. As we only had data available from our center, it is possible that patients within our cohort underwent ablation procedures at other centers. Additionally, some of the clinical data was extracted from provider documentation, which is not standardized, making available data variable. There were electronic health record system changes during the study period making patient insurance status especially difficult to track. Furthermore, a more robust measure of SES made by prospectively collecting individual patient SES data might provide better insight into its effect on receiving ablation therapy. Given the duration of study period, means with which race and ethnicity (patient reported or staff assigned) were variable. In our study of 18 years of data, we likely captured almost all patient that would have ultimately had an ablation, however those included towards the end of the study period may eventual go on to receive an ablation at a later time.

Conclusion

The decision for treatment of SVT with medication or ablation a unique decision involving patients, families and providers. We found that pediatric patients with SVT are less likely to receive ablation treatment if they are a race other than White. We did not find a difference in likelihood of ablation therapy based on SES. Further investigation is needed into determining if similar disparities exist in other institutions and the etiology of these disparities.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R38HL143612 and by the Duke Pediatric Research Scholars Program.

Abbreviations:

- SVT

Supraventricular tachycardia- SVT

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EP

electrophysiology

- SES

socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Author Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this case to disclose.

References

- [1].Smedley BD, Stith AY, and Nelson AR, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care - PubMed - NCBI. National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Matoba N. and Collins JW, “Racial disparity in infant mortality,” Semin. Perinatol, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 354–359, Oct. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Oberg C, Colianni S, and King-Schultz L, “Child Health Disparities in the 21st Century,” Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 291–312, Sep. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nembhard WN, Xu P, Ethen MK, Fixler DE, Salemi JL, and Canfield MA, “Racial/ethnic disparities in timing of death during childhood among children with congenital heart defects.,” Birth Defects Res. A. Clin. Mol. Teratol, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Collins JW, Soskolne G, Rankin KM, Ibrahim A, and Matoba N, “African-American:White Disparity in Infant Mortality due to Congenital Heart Disease,” J. Pediatr, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Benavidez OJ, Gauvreau K, and Jenkins KJ, “Racial and ethnic disparities in mortality following congenital heart surgery,” Pediatr. Cardiol, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oster ME, Strickland MJ, and Mahle WT, “Racial and ethnic disparities in post-operative mortality following congenital heart surgery,” J. Pediatr, vol. 159, no. 2, pp. 222–226, Aug. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang Y, Liu G, Druschel CM, and Kirby RS, “Maternal race/ethnicity and survival experience of children with congenital heart disease.,” J. Pediatr, vol. 163, no. 5, pp. 1437–42.e1–2, Nov. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang Y. et al. , “Racial/ethnic differences in survival of United States children with birth defects: A population-based study,” J. Pediatr, vol. 166, no. 4, pp. 819–826.e2, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kucik JE et al. , “Role of health insurance on the survival of infants with congenital heart defects,” Am. J. Public Health, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Scognamiglio R, “The science and practice of pediatric cardiology, second edition: Volumes I and II: Edited by Garson Arthur Jr, Bricker J. Timothy, Fisher David J., and Neish Williams Steven R.& Wilkins Baltimore(1998) 3,200 pages, illustrated, $299.00 ISBN: 0–683-0,” Clin. Cardiol, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Paul T, Bertram H, Kriebel T, Windhagen-Mahnert B, Tebbenjohanns J, and Hausdorf G, “[Supraventricular tachycardia in infants, children and adolescents: diagnosis, drug and interventional therapy].,” Z. Kardiol, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 546–58, Jun. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Van Hare GF et al. , “Prospective assessment after pediatric cardiac ablation: design and implementation of the multicenter study,” Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 332–341, Jan. 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Deisenhofer I. et al. , “Cryoablation versus radiofrequency energy for the ablation of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (the CYRANO Study): results from a large multicenter prospective randomized trial,” Circulation, vol. 122, no. 22, pp. 2239–2245, Nov. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kugler JD, Danford DA, Houston KA, and Felix G, “Pediatric radiofrequency catheter ablation registry success, fluoroscopy time, and complication rate for supraventricular tachycardia: comparison of early and recent eras,” J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 336–341, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Walls M, Allen CG, Cabral H, Kazis LE, and Bair-Merritt M, “Receipt of Medication and Behavioral Therapy Among a National Sample of School-Age Children Diagnosed With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,” Acad. Pediatr, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 256–265, Apr. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hewes HA, Dai M, Mann NC, Baca T, and Taillac P, “Prehospital Pain Management: Disparity By Age and Race,” Prehospital Emerg. Care, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 189–197, Mar. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chan T, Pinto NM, and Bratton SL, “Racial and insurance disparities in hospital mortality for children undergoing congenital heart surgery,” Pediatr. Cardiol, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 1026–1039, Oct. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nembhard WN, Salemi JL, Ethen MK, Fixler DE, DiMaggio A, and Canfield MA, “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Risk of Early Childhood Mortality Among Children With Congenital Heart Defects,” Pediatrics, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].“U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: North Carolina.” [Online]. Available: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NC. [Accessed: 19-May-2021]. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mitchell SJ, Bilderback AL, and Okelo SO, “Racial Disparities in Asthma Morbidity among Pediatric Patients Seeking Asthma Specialist Care,” Acad. Pediatr, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 64–67, Jan. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brown ZD et al. , “Racial disparities in health care access among pediatric patients with craniosynostosis,” in Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 2016, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, and Lemore M, “On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities | Health Affairs,” Health Affairs Blog, 2021. [Online]. Available: 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/. [Accessed: 22-Jun-2021]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chan T, Lion KC, and Mangione-Smith R, “Racial disparities in failure-to-rescue among children undergoing congenital heart surgery,” J. Pediatr, vol. 166, no. 4, pp. 812–818.e4, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chan T, Barrett CS, Tjoeng YL, Wilkes J, Bratton SL, and Thiagarajan RR, “Racial variations in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use following congenital heart surgery,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg, vol. 156, no. 1, pp. 306–315, Jul. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gonzalez PC, Gauvreau K, DeMone JA, Piercey GE, and Jenkins KJ, “Regional racial and ethnic differences in mortality for congenital heart surgery in children may reflect unequal access to care,” Pediatr. Cardiol, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 103–108, Mar. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Klitzner TSTS, Lee M, Rodriguez S, and Chang RKR, “Sex-related disparity in surgical mortality among pediatric patients,” Congenit. Heart Dis, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 77–88, May 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Peterson JK, Chen Y, Nguyen DV, and Setty SP, “Current trends in racial, ethnic, and healthcare disparities associated with pediatric cardiac surgery outcomes,” Congenit. Heart Dis, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 520–532, Jul. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brooks T. and Gardner A, “CCF.GEORGETOWN.EDU SNAPSHOT OF CHILDREN WITH MEDICAID Snapshot of Children with Medicaid by Race and Ethnicity, 2018,” 2020. [Google Scholar]