Abstract

Background:

Churches can be important settings for promoting physical activity (PA) among Latinos. Little is known about what factors across the church context – social, organizational, physical (outdoor spaces) – are associated with Latinos’ PA to inform faith-based PA interventions. This study investigated associations of church contextual factors with Latinos’ PA.

Methods:

We used cross-sectional data from a Latino adult sample recruited from six churches that each had an adjacent park in Los Angeles, CA (n=373). Linear or logistic regression models examined associations of church PA social support, PA social norms, perceived quality and concerns about the park near one’s church, and church PA programming with four outcomes: accelerometer-based moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) and self-reported adherence to PA recommendations, use of the park near one’s church, and park-based PA.

Results:

Park quality and concerns were positively associated with using the park near one’s church. Church PA programming was positively associated with park-based PA. None of the factors were related to accelerometer-based MVPA or meeting PA recommendations.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest targeting church PA programming and nearby parks may be key for improving Latinos’ park use. Church and local parks department partnerships may help enhance park conditions to support churchgoing Latinos’ PA and health.

Keywords: Latinos, faith-based intervention, physical activity, parks, multilevel

Introduction

Religiosity is related to engaging in more physical activity, which contributes to favorable physical and mental health by improving physiological processes and psychological functioning.1 Although Latinos report higher church attendance than non-Latino whites,2 they are less physically active during leisure-time,3 which is associated with increased risk of poor health.4 Churches have extensive reach in the Latino population in the U.S. and are increasingly targeted for public health interventions, but a recent systematic review identified gaps in faith-based interventions targeting physical activity (PA).5 Specifically, the review identified 16 faith-based interventions focused on Latinos, with only four targeting PA promotion, most of which intervened at the individual- or social-level.5 To inform faith-based interventions to promote PA among churchgoing Latinos, a better understanding is needed of the modifiable targets from the church context, including factors across the social, physical (e.g., outdoor spaces), and organizational levels, as supported by socio-ecological frameworks.6 To date, most research on PA correlates among Latinos has focused on the individual (e.g., self-efficacy) and social (e.g., social support) levels; less attention has been placed on the physical environmental and organizational levels.5,7 Generally, interventions solely focused on individual and social processes have had limited success in improving Latinos’ PA and as such, interventions targeting multiple levels of influence may be more effective.7,8 Although there are a growing number of faith-based health interventions, including for PA promotion, few target multiple levels of influence.9 The available evidence to inform multilevel PA interventions is limited to findings from studies focused on contexts other than the church, such as studies focused on neighborhood or family/home environments. To our knowledge, no published study has examined multilevel factors across the church context in relation to Latinos’ PA. Such evidence is needed to identify appropriate targets for faith-based PA interventions, which could help optimize their effects on increasing PA among Latinos.5

With respect to the social environment, several studies point to a positive association between PA social support from friends or family and Latinos’ PA.7,10 Studies focused on churchgoing African Americans also show that social support from other church members may help reinforce PA among parishioners;11,12 but such an association is not well understood among Latinos. PA social norms (behaviors or attitudes of others) are also associated with PA, independent of social support.13 However, much of the evidence about PA social norms is focused on family or friends and less attention has been placed on PA social norms in the church. A study with African Americans found that seeing fellow parishioners use PA facilities at the church was positively associated with parishioners’ PA.11 A qualitative study in San Diego, CA also found that church leaders and staff perceived that the PA behaviors of pastors were important for motivating Latino parishioners’ PA.14 To our knowledge, no published quantitative study has examined the role of church PA social norms on Latino’s PA.

At the physical environmental level, little is known about the health-promoting environments surrounding churches. Research on the environmental correlates of Latinos’ PA is largely focused on attributes of the home neighborhood such as access to open spaces like parks.15,16 Living close to a park can provide opportunities for PA, and park-based PA can support individuals towards achieving national PA recommendations.17,18 Although evidence from a national study suggests that residents of predominantly Latino neighborhoods live closer to parks compared to residents of areas with fewer Latinos,19 such parks are largely underutilized.20 Concerns about safety or other problems (e.g., poor maintenance) can deter park use.21 Given many churches in low-income settings have access to outdoor spaces such as parks,22 they can play a role in addressing park barriers by mobilizing parishioners to advocate for park improvements.23 To our knowledge, no study has evaluated how churchgoing Latinos use parks near their churches and potential facilitators or barriers to using them, particularly for PA.

To promote greater use of parks near churches, having organized PA programming at the church (an organizational factor) may be key. Churches can provide additional support and opportunities for parishioners to engage in PA by delivering education messages about exercise and offering PA classes, among other activities.5 However, no published study that we are aware of has examined how church PA programming is related to Latinos’ PA or park use.

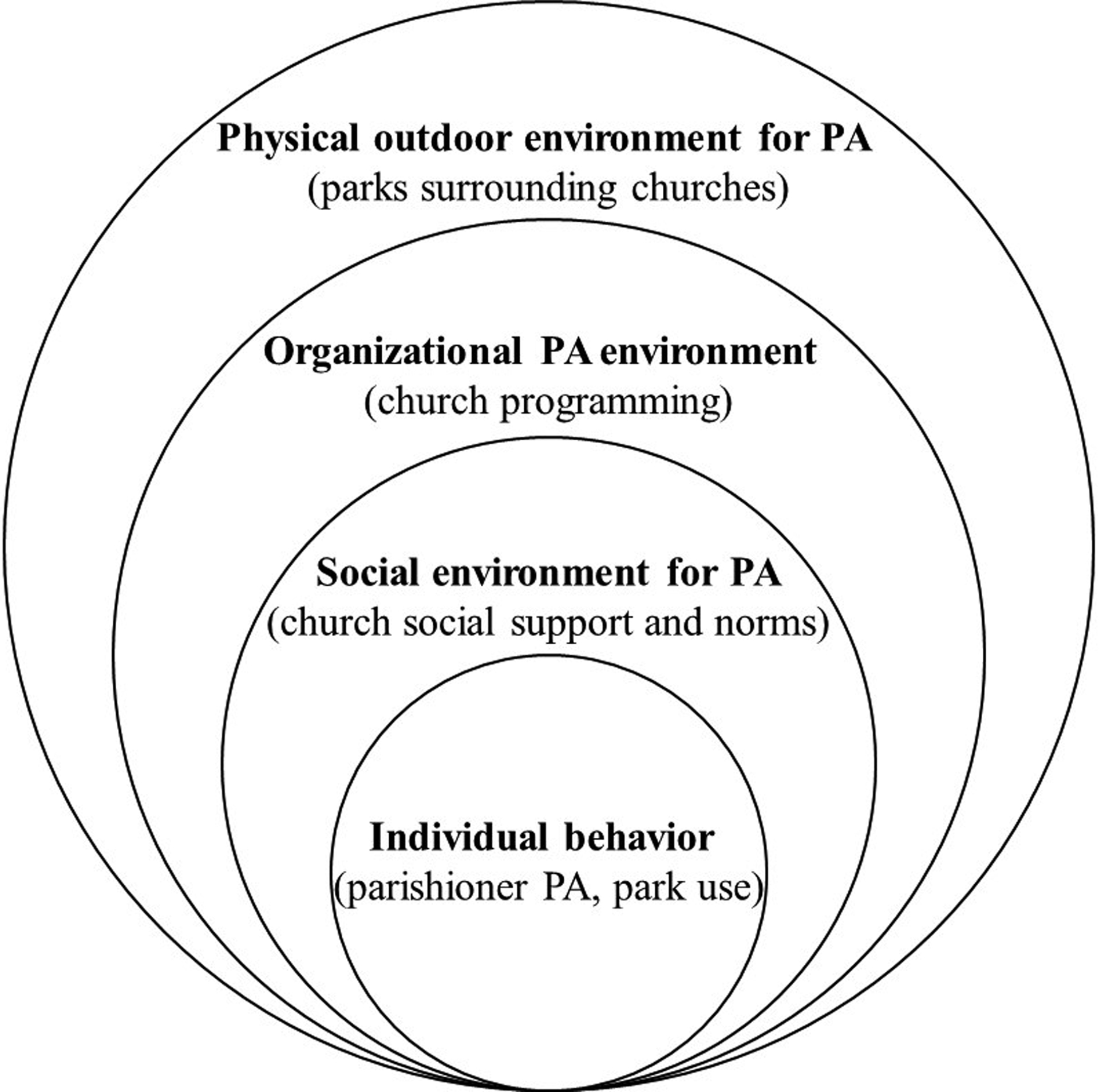

To address the aforementioned gaps, this cross-sectional study aimed to examine associations of factors across the social, organizational, and physical environmental (nearby park) levels of the church context with PA and park use among churchgoing Latino adults (conceptual framework presented in Figure 1). We examine multiple objective and self-reported outcomes to identify behavior-specific correlates (i.e., potential targets) to inform multilevel faith-based interventions aimed to improve Latinos’ PA and health.

Figure 1.

Socio-ecological framework for physical activity (PA) and park use correlates across the church context.

Methods

Overview

This study used baseline data from an ongoing cluster randomized controlled trial to promote PA in parks among churchgoing Latino adults. The study is an academic-community collaboration involving a non-profit research organization, a kinesiology department at a Hispanic-serving state university, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles City Department of Recreation and Parks. The intervention is being implemented in two cohorts, and the present analysis uses data collected in 2019 from the first cohort. The Institutional Review Board of the lead institution approved this study and participants provided written informed consent.

Sample Recruitment

The study team and community collaborators identified six Catholic churches from one Deanery in East Los Angeles and randomized half to receive the intervention and the other half to a waitlist control group. Given the intervention aims to promote park-based PA among Latino adults, churches in neighborhoods that were at least 80% Latino per U.S. Census figures were eligible if they had a park nearby (≤0.6 miles along a safe walking route). The Principal Investigator and project manager met with the pastor at eligible churches to discuss the study and obtain institutional commitment.

Parishioners from the participating churches were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: self-identified as Latino; 18 years of age or older; attended the church for at least the past 6 months and more than once/month; planned on attending the church for the next 12 months; did not attend any of the other participating churches; resided within 15 minutes driving distance from the church; planned to live in the same neighborhood for the next 12 months; and were able to attend activities at the church during the week. If an individual did not meet any these criteria, they were deemed not eligible. A health screener assessed history and symptoms of health conditions that could preclude PA.24 If an individual reported one or more of the listed health symptoms (e.g., chest discomfort with exertion), they were asked to get a doctor’s note authorizing participation. Those who reported a health condition but engaged in exercise at least three times a week in the last three months were still eligible. Originally, if an individual reported on the screener that they engaged in 150 or more minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week, they would be deemed not eligible. However, parish leaders wanted lay peer leaders to participate to motivate others, so we revised our protocol and did not restrict eligibility based on reported PA minutes but aimed to recruit larger numbers than originally planned.

Of 718 parishioners screened for eligibility, 597 met the inclusion criteria, of which 557 consented and were enrolled in the study. For the present analysis, we focused on those who completed the health survey and the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ; which was administered separately) and/or had valid accelerometry data (valid wear time criteria are described below). Among the 510 who completed the health questionnaire, 498 also completed the GPAQ and 408 had valid accelerometry data. We dropped participants from the analyses if they had missing data on the independent variables of interest (church multilevel factors), socio-demographics, or outcomes. Overall, most of the missing data came from two variables: park quality rating (n=73) and church PA programming (n=60). This reduced the analytic sample to 373 for the self-reported PA and park-use models (minus 1 participant who had missing data on frequency of using the park near one’s church), and 295 for the accelerometer-based PA model.

Data Collection

Between March and November 2019, trained bilingual/bicultural research assistants (RAs) collected baseline data, including a health survey and the GPAQ,25 both offered in English or Spanish via tablet; biometrics (e.g., weight, body fat); and accelerometry. RAs administered the GPAQ for all participants and the health survey for those requesting assistance. Participants received a $25 gift card for completing baseline measures.

Measures: Outcomes

Objective moderate-to vigorous PA (MVPA).

Participants were asked to wear an ActiGraph wGT3X-BT activity monitor (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL) initialized to collect data at a sampling rate of 30 Hz. Participants were instructed to wear the ActiGraph on an elastic belt around the hip for 7 consecutive days and remove it during water activities (e.g., showering) and sleeping. We defined non-wear time as 60 consecutive minutes of zero count values as recommended for adult samples.26 We defined wear time as ≥10 hours/day of data for at least 3 days, similar to a large cohort study of Latinos27. We downloaded the data as 60-second epoch files and processed the files using ActiLife v6.13.4 (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL). We used the Freedson 1998 cut-points28 to define moderate-intensity as 1952–5724 counts per minute (CPM) and vigorous activity as 5725–9498 CPM. The software computed average daily minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA), which we multiplied by 7 to estimate MVPA minutes per week. Data were normally distributed.

Meeting PA recommendations.

The GPAQ assessed participants’ frequency and duration of PA during leisure-time, work, and transportation.25 The present analysis focused on the six items for leisure-time PA (LTPA), which assessed whether participants did sports, fitness, or recreational activities at moderate or vigorous intensity for at least 10 minutes continuously. Those who responded ‘yes’ were then asked how many days they did those activities in a typical week and the time spent in those activities in a typical day. After summing the leisure-time moderate- and vigorous-minutes per week, we found that about half of the sample reported no LTPA. Thus, we created a binary variable using the 2018 PA Guidelines29 to classify participants as meeting/not meeting PA recommendations via LTPA. Although all domains of PA can be included in meeting the recommendations, we focused on LTPA given the intervention is focused on exercise and park-based PA. Participants who reported ≥150 minutes/week of moderate PA, or ≥75 minutes/week of vigorous PA, or ≥600 metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes of MVPA during leisure-time were classified as meeting PA recommendations.

Use of park near one’s church.

Given one of the eligibility criteria for churches was that the church had a park nearby, we examined parishioners’ use of that park. One item, created by the study team, asked participants to report how often they visited the park adjacent to their church (park name was specified) (0=never to 6=daily). Responses were highly skewed, with about half reporting ‘never’ visiting the park; thus, we dichotomized park use as ‘any’ versus ‘never’.

Park-based PA.

We also created an item to assess what activities participants usually do while visiting a park (could include the park near their church). Those who selected ‘exercise,’ ‘play team sports,’ and/or ‘walk’ from a list of eight different activities were classified as engaging in park-based PA, and those who selected only passive activities (e.g., picnics) or none of the activities were classified as not engaging in park-based PA.

Measures: Multilevel Factors

Church social environment.

Church PA social norms was assessed with two items created by the study team that separately asked how often participants saw a) other parishioners and b) their pastor or other religious leader participate in PA such as walking, jogging, bicycling, or playing sports (0=never to 4=very often). Church PA social support was assessed with three items asking participants how often other members of their church “do PA with you,” “offer to do PA with you,” and “give you encouragement to do PA” (0=never to 4=very often). Items were adapted from a validated scale about social support from family and friends.30 Both scales had good internal consistency among our sample (α= 0.70 for social norms and 0.92 for social support). We computed mean scores for each scale, with higher scores indicating more favorable social norms or support.

Church organizational environment.

Church PA programming was assessed by one item developed by the study team that asked participants to identify from a list of nine activities, those that had occurred at their church in the last six months, e.g., text messaging about the importance of PA, workshops about exercise, and exercise classes or walking groups. We created a sum score (range: 0–9), with higher scores reflecting a more active organizational environment.

Park environment.

Quality of the park near one’s church was assessed with one item created by the study team that asked participants to rate the park adjacent to their church (park name was specified) (1=poor to 5=excellent). Higher scores are indicative of better perceived quality. Concerns about the park near one’s church was assessed with one item created by the study team that asked participants to select from a list of nine options, which were concerns that they had about the park adjacent to their church (e.g., crime or violence; gang members; homeless). We created a sum score (range: 0–9), with higher scores reflecting more perceived problems. Both items on park quality and park concerns were asked of all participants, regardless of whether they visited the park near their church. Individuals could know a park by reputation and have negative beliefs or suspicions about the park that could impede their motivation to visit, or an individual could have visited the park years ago but not recently; thus, we allowed all participants a chance to answer these park-related questions. Data missingness on these items did not differ among those who reported visiting the park and those who never visited it.

Measures: Covariates

We selected variables correlated with our outcomes in preliminary analyses, including age, gender, education, and marital status. We dichotomized education (less than high school vs. high school or more) and marital status (single, divorced, separated, widowed vs. married or living with partner, but not married). We included country of origin for descriptive purposes given most participants are from Mexico. We also included church affiliation, based on the parish from which the participant was recruited.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the outcomes, multilevel factors, and socio-demographic variables. We used linear regression for the accelerometer-based MVPA outcome and logistic regression for the other three self-reported binary outcomes. Bivariate models estimated the associations between each of the five multilevel factors and outcomes. Then, we conducted three “single-level” models in which factors at each level (social, organizational, park) were tested separately in relation to each outcome, adjusting for the socio-demographic variables and church affiliation. The final “full models” tested all five factors across the three levels simultaneously in relation to each outcome, adjusting for the covariates. We tested for multicollinearity among the independent variables and found no issues. We performed all analyses using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics, including an average age of 50 years (SD= 14), the majority are of Mexican origin (89%) and female (78%), and about half completed at least high school. On average, participants engaged in 188.4 minutes/week (SD= 150.5) of accelerometer-based MVPA and reported 132.8 minutes/week (SD= 292.8) of leisure-time MVPA. About 30% met PA recommendations based on LTPA, 55% reported using the park near their church, and 67% reported park-based PA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Latino analytic sample (N=373).

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 50.4 (14.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 84 (22.5%) |

| Female | 289 (77.5%) |

| Education completed, n (%) | |

| Less than high school | 181 (48.5%) |

| High school or higher | 192 (51.5%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single or not married (divorced, separated, widowed) | 166 (44.5%) |

| Married or living with partner, but not married | 207 (55.5%) |

| Country of origin | |

| Mexico | 329 (88.2%) |

| Other | 44 (11.8%) |

| Objective outcome | |

| Accelerometer-based MVPA (min/week), mean (SD)a | 188.4 (150.5) |

| Self-report outcomes | |

| Leisure-time MVPA (min/week), mean (SD) | 132.8 (292.8) |

| Meets PA recommendations via leisure-time PA, n (%) | |

| Yes | 112 (30.0%) |

| No | 261 (70.0%) |

| Frequency of using park near one’s church, n (%) | |

| Any | 206 (55.4%) |

| Never | 166 (44.6%) |

| Engages in park-based PA, n (%) | |

| Yes | 249 (66.8%) |

| No | 124 (33.2%) |

| Church context, mean (SD) b | |

| Church PA social norms (range 0–4) | 0.78 (0.87) |

| Parishioner PA social support (range 0–4) | 0.49 (0.84) |

| Church PA programming (range 0–9) | 1.78 (2.02) |

| Quality of park near one’s church (range 1–5) | 2.79 (1.01) |

| Concerns about park near one’s church (range 0–9) | 2.45 (2.16) |

Notes: MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA= physical activity; SE = standard error

n=295. Among the 373, we dropped 78 who did not have valid accelerometry data.

Higher scores indicate more favorable perceptions of the contextual factors, with the exception of concerns about the park, where higher scores indicate more perceived problems.

Associations of Factors at Each Church Level with PA and Park Use

Bivariate associations between each factor and outcome can be found in Table 2. Table 3 presents the adjusted single-level models linking factors at each level of the church context (social, organizational, or park) with each outcome. The models focused only on the social environment factors show that parishioner PA social support is significantly associated with a higher odds of using the park near one’s church (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.06–1.98), and marginally associated with meeting PA recommendations (OR=1.33, 95% CI: 0.98–1.80). The models focused on the organizational environment show church PA programming is significantly associated with meeting PA recommendations (OR=1.12, 95% CI: 1.00–1.26), using the park near one’s church (OR=1.14, 95% CI: 1.02–1.28), and park-based PA (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.00–1.27), but not accelerometer-based MVPA (Table 3). The final models focused on the conditions of parks near participants’ churches show that both perceived park quality (OR=2.19, 95% CI: 1.66–2.89) and concerns (OR=1.20, 95% CI: 1.06–1.34) are positively associated with using those parks, but not any of the other outcomes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Bivariate models assessing the associations of each factor across the church context with accelerometer-based or self-report PA and park use outcomes among Latinos.

| Self-report outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Accelerometer-based MVPA (n=295) | Meets PA recommendations via leisure-time PA (n=373) | Uses park near one’s church (n=372) | Engages in park-based PA (n=373) | |

| B (SE) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) |

|

| Social environment | |||||

| Church PA social norms | 9.71 (10.19) | 0.34 | 1.19 (0.93–1.53) |

1.52 (1.17–1.97) * |

1.01 (0.79–1.29) |

| Parishioner PA social support | −2.48 (11.09) | 0.82 | 1.25 (0.97–1.61)† |

1.53 (1.17–2.02) * |

0.98 (0.76–1.27) |

| Organizational environment | |||||

| Church PA programming | −1.33 (4.24) | 0.75 | 1.10 (0.99–1.23)† |

1.20 (1.08–1.34) * |

1.11 (0.99–1.25)† |

| Park environment | |||||

| Quality of park near one’s church | −7.56 (9.03) | 0.40 | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) |

1.96 (1.54–2.49) * |

1.02 (0.82–1.26) |

| Concerns about park near one’s church | 5.86 (4.06) | 0.15 | 1.02 (0.93–1.13) |

1.02 (0.92–1.12) |

1.06 (0.96–1.18) |

p<0.05;

p<0.10

Notes: CI= confidence interval; MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; OR= odds ratio; PA= physical activity; SE = standard error

Table 3.

Adjusted single-level modelsa examining the associations of factors at each level of the church context with accelerometer-based or self-reported PA and park use outcomes among Latinos.

| Self-report outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Accelerometer-based MVPA (n=295) | Meets PA recommendations via leisure-time PA (n=373) | Uses park near one’s church (n=372) | Engages in park-based PA (n=373) | |

| B (SE) | p-value | OR 95% CI |

OR 95% CI |

OR 95% CI |

|

| Social environment (model 1) | |||||

| Church PA social norms | 11.83 (10.62) | 0.27 | 1.12 (0.82–1.51) |

1.26 (0.94–1.70) |

1.03 (0.78–1.37) |

| Parishioner PA social support | −4.38 (11.61) | 0.71 | 1.33 (0.98–1.80)† |

1.45 (1.06–1.98) * |

1.04 (0.77–1.39) |

| Organizational environment (model 2) | |||||

| Church PA programming | −1.74 (3.99) | 0.66 | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) * |

1.14 (1.02–1.28) * |

1.13 (1.00–1.27) * |

| Park environment (model 3) | |||||

| Quality of park near one’s church | 2.04 (9.17) | 0.82 | 1.01 (0.78–1.30) |

2.19 (1.66–2.89) * |

1.05 (0.83–1.34) |

| Concerns about park near one’s church | 6.37 (4.15) | 0.13 | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) |

1.20 (1.06–1.34) * |

1.08 (0.96–1.21) |

p<0.05;

p<0.10

Notes: CI= confidence interval; MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; OR= odds ratio; PA= physical activity; SE = standard error

Separate models assessed the associations between the factors at each level (social, organizational, park) and each outcome, adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, and church affiliation (total of 3 models per outcome).

Associations of Factors across All Church Levels with PA and Park Use

In the full model testing all five church factors simultaneously, we found significant correlates for the park use outcomes only (Table 4). Higher park quality (OR=2.13, 95% CI: 1.60–2.83) and number of park concerns (OR=1.19, 95% CI: 1.06–1.34) were significantly associated with higher odds of using the park near one’s church, independent of the social and organizational environments (Table 4). Further, more types of church PA programming were significantly related to higher odds of engaging in park-based PA (OR=1.15, 95% CI: 1.01–1.31), independent of the social and park environments. There were no significant correlates for accelerometer-based MVPA or meeting PA recommendations.

Table 4.

Adjusted full modelsa assessing the associations of all five factors across the three levels of the church context simultaneously with accelerometer-based or self-reported PA and park use outcomes among Latinos.

| Self-report outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Accelerometer-based MVPA (n=295) | Meets PA recommendations via leisure-time PA (n=373) | Uses park near one’s church (n=372) | Engages in park-based PA (n=373) | |

| B (SE) | p-value | OR 95% CI |

OR 95% CI |

OR 95% CI |

|

| Social environment | |||||

| Church PA social norms | 14.55 (10.96) | 0.19 | 1.10 (0.81–1.50) |

1.20 (0.87–1.65) |

0.98 (0.73–1.31) |

| Parishioner PA social support | −2.89 (12.10) | 0.81 | 1.27 (0.92–1.75) |

1.30 (0.92–1.83) |

0.93 (0.68–1.27) |

| Organizational environment | |||||

| Church PA programming | −3.24 (4.43) | 0.46 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) |

1.08 (0.94–1.23) |

1.15 (1.01–1.31) * |

| Park environment | |||||

| Quality of park near one’s church | 0.95 (9.32) | 0.92 | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) |

2.13 (1.60–2.83) * |

1.05 (0.82–1.33) |

| Concerns about park near one’s church | 6.43 (4.17) | 0.12 | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) |

1.19 (1.06–1.34) * |

1.08 (0.97–1.22) |

p<0.05;

p<0.10

Notes: CI= confidence interval; MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; OR= odds ratio; PA= physical activity; SE = standard error

Full models tested the associations of all five factors simultaneously with each outcome, adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, and church affiliation (1 model per outcome).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to investigate the associations of factors across multiple levels of the church context – social, organizational, and physical environment (nearby parks)– with Latinos’ PA and park use. Overall, when examining each level one at a time, we found significant correlates for all self-report PA and park use outcomes but not accelerometer-based MVPA. However, when accounting for all three levels simultaneously, only a few of these associations remained significant, specifically for the two self-reported park use outcomes. The park factors (quality and concerns) remained positively associated with using the park near one’s church, independent of the social and organizational factors, and church PA programming remained positively related to park-based PA, independent of the social and park factors. The lack of significant associations between the church multilevel factors and accelerometer-based MVPA or meeting PA recommendations was unexpected but given both outcomes are based on moderate-to vigorous-intensity activity, PA behaviors at this intensity level may be less common in the church compared to light activity (e.g., walking). The accelerometer also captures total activity across all-domains (leisure, work, transport) and is not specific to PA behaviors that can be done in the church environment.

Our findings suggest that focusing on a single level (e.g., social) may be ignoring the broader context in which that level operates (e.g., organizational), and may be too narrow to inform faith-based interventions to promote PA among Latinos. As such, our study provides support for socio-ecological frameworks to understand and intervene on different levels of the church context, particularly organizational programming and outdoor spaces (parks), to address PA disparities among churchgoing Latinos.

Although faith-based interventions often target church social networks and health programming,5,31 no published study to our knowledge has examined these factors simultaneously in relation to Latinos’ PA behaviors. Studies examining church correlates of PA have largely focused on one level. For example, a study with African Americans that focused only on the church social environment showed that anticipated religious social support was related to higher moderate-intensity PA.12 In our single-level model focused on the social environment only, parishioner PA social support was marginally related to meeting PA recommendations; but when accounting for the park and organizational factors in the full model, this association was non-significant. Further, although findings from a qualitative study suggests that church PA social norms may be important for motivating Latino parishioners’ PA,14 this factor was not related to any of the outcomes in our study. Given most participants visit their church on one day of the week for mass (1 hr on Sundays), this may be insufficient exposure to allow parishioners to interact with one another to talk about PA (social support) or see their fellow church members or leaders engage in PA (norms). To enhance the role of the church social environment for PA promotion among churchgoing Latinos, additional programming may be needed throughout the week that provides opportunities for parishioners to connect beyond mass times, particularly in activities that focus on PA.

To our knowledge, our study is one of the first to examine church multilevel correlates of park use behaviors among Latinos. Our full model for the outcome ‘use of the park near one’s church’ showed significant associations with the park-level factors only. This finding suggests that park conditions (quality and concerns) are the most important targets for promoting parishioners’ use of parks next to churches, over and above parishioner PA social support or norms and church PA programming. The church social and organizational factors were significantly related to use of the park near one’s church in the single-level models but not the full model. It is possible that the social, organizational, and park factors influence one another to shape park use. For example, participants may have concerns about the park near their church, but those concerns might not impede their use of the park if they see other church members engaging in park-based PA (social norms). Mediation analyses with longitudinal data are needed to examine the mechanisms by which these factors work together to influence PA.

Our finding linking better park quality ratings with use of the park near one’s church is consistent with studies focused on neighborhood park use.32,33 Further, although our finding linking greater number of concerns about the park near one’s church with higher use of that park was unexpected, this finding is also in line with another study from South Carolina,34 which found a positive association between neighborhood park incivilities and number of park visitors. Another study from Los Angeles found that park use may also depend on the type of concern; for example, the presence of homeless individuals was associated with more park visitors but the presence of intoxicated persons was associated with fewer park visitors.21 Our study used a sum score of perceived concerns about the church park instead of examining individual concerns given the low frequencies for some concerns. Another possible explanation for our finding is that those who more frequently visited the park near their church were more aware of problems in the park, which would indicate a bidirectional relationship between park concerns and park use.

Finally, for park-based PA, the only significant correlate was the organizational factor (church PA programming), independent of the social and park factors. This suggests that having favorable park conditions was not sufficient to support participant’s PA in parks and church PA programming may be necessary. A review of 38 intervention studies found that targeting only the physical conditions of urban green spaces were largely ineffective, while interventions that combined physical changes with promotion/marketing programs that encouraged use of the green spaces showed significant increases in park use and PA.35 One study from Los Angeles found that improvements to park facilities were not associated with changes in park use or PA; instead, increases in organized activities in the parks appeared to have the greatest effect.36 Faith-based interventions to promote PA among Latinos may need to help enhance PA programming at nearby parks to increase parishioners use of parks for exercise.

Overall, our findings suggest that the conditions of parks near churches may be an important target for promoting park use among churchgoing Latinos. Faith-based interventions aimed to promote PA may need to build partnerships with local parks departments to address barriers to using nearby parks for exercise and to support additional church programming around PA (or other health topics), particularly if churches have limited space or resources to support health programming. Engaging parishioners in identifying park barriers to exercise is important for ensuring their most pressing needs are targeted, but their engagement should not be limited to understanding barriers; additional efforts to empower parishioners to identify potential solutions is also critical. For example, one intervention in San Diego, CA engaged a non-profit focused on neighborhood walkability to train promotoras (Community Health Workers) and youth from a church to identify park barriers through park audits and to advocate for improvements of the park near their church.23 Further, interventions must not overlook the potential influence of the church social environment. Although our study did not find significant associations of the church social environmental factors with any of the PA outcomes, this remains a critical level of influence that may be activated with enhancements to church PA programming in parks and parishioner empowerment to collectively identify park barriers to PA and solutions to those barriers.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used a socio-ecological framework to understand how church factors across the social, organizational, and physical environmental levels are associated with objective and self-reported PA and park use outcomes, thereby addressing limitations of past research that has largely focused on a single level. We examined a range of outcomes, allowing us to detect behavior-specific correlates. Although our sample included both men and women, the higher proportion of women may have influenced the prevalence of the outcomes assessed (e.g., women are less likely to visit parks but more likely to participate in park-based PA programs than men37).

The present analysis was cross-sectional and thus, we are unable to make causal inferences. Missing data for some of the variables of interest reduced our sample size and likely, statistical power to detect associations; this may have also introduced bias. Our self-report measures may have also been subject to different sources of bias (e.g., respondent bias, recall bias, and social desirability).

Conclusions

Given churches have extensive reach among Latinos, they have great potential for implementing PA interventions. Efforts to improve PA among Latinos need to move beyond changing individual and social factors and consider integrating environmental or organizational changes. Overall, our results suggest that the conditions of parks next to churches may be important targets for promoting churchgoing Latinos’ use of those parks, but church organizational support through PA programming may be more important for promoting exercise in nearby parks.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the Parishes & Parks study team for their assistance on the project intervention activities and data collection efforts.

Funding sources:

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA218188). The lead author was funded by a Diversity Supplement from the National Cancer Institute (3R01CA218188-03S2).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lilian G. Perez, Associate Policy Researcher, Behavioral and Policy Sciences Department, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA,.

Deborah A. Cohen, Research Scientist III, Division of Behavioral Health, Kaiser Permanente, Pasadena, CA,; Previous affiliation: RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Rachana Seelam, Research Programmer, Research Programming, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA,.

Bing Han, Research Scientist III, Division of Biostatistics Research, Kaiser Permanente, Pasadena, CA,; Previous affiliation: RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Elva M. Arredondo, Professor, Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA,.

Gabriela Castro, Policy Analyst, Behavioral and Policy Sciences Department, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA,.

Claudia Rodriguez, Assistant Policy Researcher and PhD candidate, Pardee RAND Graduate School, Santa Monica, CA,.

Michael A. Mata, Visiting Professor of Urban Studies and Theology, Nazarene Theological Seminary, Kansas City, MO,.

Anne Larson, Professor, Department of Kinesiology & Nutritional Science, California State University, Los Angeles, CA,.

Kathryn P. Derose, Professor, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, and Senior Policy Researcher, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

References

- 1.Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:278730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pew Research Center. 2014 Religious Landscape Study. https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/racial-and-ethnic-composition/. Published 2015. Accessed June 9, 2021.

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics. QuickStats: Percentage of adults who met federal guidelines for aerobic physical activity through leisure-time activity, by race/ethnicity - National Health Interview Survey, 2008–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(12):292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleven L, Krell-Roesch J, Nigg CR, Woll A. The association between physical activity with incident obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes and hypertension in adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies published after 2012. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derose KP, Rodriguez C. A systematic review of church-based health interventions among Latinos. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(4):795–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz KR, B.K.; Viswanath K, ed. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen BA, Noble ML, Murray KE, Marcus BH. Physical activity in Latino men and women: Facilitators, barriers, and interventions. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;9(1):4–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallis JF. Needs and challenges related to multilevel interventions: Physical activity examples. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(5):661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Florez KR, Payan DD, Palar K, Williams MV, Katic B, Derose KP. Church-based interventions to address obesity among African Americans and Latinos in the United States: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2020;78(4):304–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto SH, Arredondo EM, Haughton J, Shakya H. Leisure-time physical activity and characteristics of social network support for exercise among Latinas. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(2):432–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermstad A, Honeycutt S, Flemming SS, et al. Social environmental correlates of health behaviors in a faith-based policy and environmental change intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(5):672–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debnam K, Holt CL, Clark EM, Roth DL, Southward P. Relationship between religious social support and general social support with health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. J Behav Med. 2012;35(2):179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ball K, Jeffery RW, Abbott G, McNaughton SA, Crawford D. Is healthy behavior contagious: Associations of social norms with physical activity and healthy eating. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haughton J, Takemoto ML, Schneider J, et al. Identifying barriers, facilitators, and implementation strategies for a faith-based physical activity program. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tovar M, Walker JL, Rew L. Factors associated with physical activity in Latina women: A systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40(2):270–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murillo R, Reesor LM, Hernandez DC, Obasi EM. Neighborhood walkability and aerobic physical activity among Latinos. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(4):802–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaczynski AT, Besenyi GM, Stanis SA, et al. Are park proximity and park features related to park use and park-based physical activity among adults? Variations by multiple socio-demographic characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han B, Cohen D, McKenzie TL. Quantifying the contribution of neighborhood parks to physical activity. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):483–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen M, Zhang X, Harris CD, Holt JB, Croft JB. Spatial disparities in the distribution of parks and green spaces in the USA. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45 Suppl 1:S18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen DA, Han B, Derose KP, et al. Neighborhood poverty, park use, and park-based physical activity in a Southern California city. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2317–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen DA, Han B, Derose KP, et al. The paradox of parks in low-income areas: Park use and perceived threats. Environ Behav. 2016;48(1):230–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernhart JA, La Valley EA, Kaczynski AT, et al. Investigating socioeconomic disparities in the potential healthy eating and physical activity environments of churches. J Relig Health. 2020;59(2):1065–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arredondo E, Mueller K, Mejia E, Rovira-Oswalder T, Richardson D, Hoos T. Advocating for environmental changes to increase access to parks: Engaging promotoras and youth leaders. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(11):2473–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. 2006;14(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Ekelund U, et al. Accelerometer data collection and processing criteria to assess physical activity and other outcomes: A systematic review and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2017;47(9):1821–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evenson KR, Sotres-Alvarez D, Deng YU, et al. Accelerometer adherence and performance in a cohort study of US Hispanic adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(4):725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Haughton J, et al. Fe en Accion: Promoting physical activity among churchgoing Latinas. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1109–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rung AL, Mowen AJ, Broyles ST, Gustat J. The role of park conditions and features on park visitation and physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8 Suppl 2:S178–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormack GR, Rock M, Toohey AM, Hignell D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health Place. 2010;16(4):712–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banda JA, Wilcox S, Colabianchi N, Hooker SP, Kaczynski AT, Hussey J. The associations between park environments and park use in southern US communities. J Rural Health. 2014;30(4):369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter RF, Cleland C, Cleary A, et al. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: A meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ Int. 2019;130:104923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen DA, Golinelli D, Williamson S, Sehgal A, Marsh T, McKenzie TL. Effects of park improvements on park use and physical activity: Policy and programming implications. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):475–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derose KP, Han B, Park S, Williamson S, Cohen DA. The mediating role of perceived crime in gender and built environment associations with park use and park-based physical activity among park users in high poverty neighborhoods. Prev Med. 2019;129:105846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]