Abstract

Central sleep apnea is not a single disorder; it can present as an isolated disorder or as a part of other clinical syndromes. In some conditions, such as heart failure, central apneic events are due to transient inhibition of ventilatory motor output during sleep, owing to the overlapping influences of sleep and hypocapnia. Specifically, the sleep state is associated with removal of wakefulness drive to breathe; thus, rendering ventilatory motor output dependent on the metabolic ventilatory control system, principally PaCO2. Accordingly, central apnea occurs when PaCO2 is reduced below the “apneic threshold”. Our understanding of the pathophysiology of central sleep apnea has evolved appreciably over the past decade; accordingly, in disorders such as heart failure, central apnea is viewed as a form of breathing instability, manifesting as recurrent cycles of apnea/hypopnea, alternating with hyperpnea. In other words, ventilatory control operates as a negative—feedback closed-loop system to maintain homeostasis of blood gas tensions within a relatively narrow physiologic range, principally PaCO2. Therefore, many authors have adopted the engineering concept of “loop gain” (LG) as a measure of ventilatory instability and susceptibility to central apnea. Increased LG promotes breathing instabilities in a number of medical disorders. In some other conditions, such as with use of opioids, central apnea occurs due to inhibition of rhythm generation within the brainstem. This review will address the pathogenesis, pathophysiologic classification, and the multitude of clinical conditions that are associated with central apnea, and highlight areas of uncertainty.

Keywords: central apnea, loop gain, controller gain, plant gain, apneic threshold, hypocapnia, continuous positive pressure therapy (CPAP), bi-level positive pressure therapy (BPAP), Adaptive-Servo Ventilation (ASV)

Statement of Significance.

This paper provides a physiologically driven classification of central apnea based on the underlying mechanism of rather than the level of baseline PaCO2. This classification will inform the identification and testing of targeted therapies for central apnea and would further promote the goal of improving breathing, sleep, and quality of life for patients with central apnea.

Introduction

Central sleep apnea (CSA), as a polysomnographic finding may be associated with several cardiovascular and CNS disorders or with medication use. When no predisposing condition is found, CSA is referred to as idiopathic. Our understanding of the specific mechanism(s) of CSA has grown appreciably in the past decade, though the underlying pathophysiology of CSA in some disorders remains to be elucidated.

In this review, we will provide a new classification for central apnea, in part based on pathophysiology where known or suspected.

Determinants of central apnea during NREM sleep

The final common pathway for generation of a central apnea is the transient inhibition of ventilatory motor output during sleep, due to the failure of the respiratory rhythmogenesis. This results in the loss of activation of inspiratory thoracic pump muscles and cessation of oronasal airflow into the lungs. However, multiple factors including state of sleep (NREM vs, REM), level of PaO2 and PaCO2, circadian rhythm, arousal threshold, position (supine vs lateral), and upper airway reflexes may contribute to development and maintenance of CSA, the “turning on and off” of the ventilatory motor output. We briefly review the major determinants of central apnea, as details have been published previously [1–5].

Central apneas and instabilities in breathing occur primarily in non-rapid-eye movement (NREM) sleep. This appears to be the case in various causes of CSA such as in CHF and with opioids use.

Two physiologically important mechanisms mediate development of CSA in NREM sleep: The PaCO2-metabolic control of ventilation and the unmasking of a sensitive hypocapnic apneic threshold. In certain conditions, such as use of certain drugs and in neurodegenerative disorders, the rhythm generation by the pre-Botzinger Complex [6], the presumed center for rhythmogenesis, is impaired causing CSA. In such disorders, the hyperpnea following a central apnea will lower the prevailing PaCO2 below the apneic threshold perpetuating the periodic breathing. In all the conditions, CSA occurs primarily in NREM sleep and commonly in supine position.

The removal of wakefulness drive to breathe, in NREM sleep renders ventilatory motor output dependent on the metabolic ventilatory control system, principally PaCO2; thus a small drop in PaCO2, 3 to 5 mm Hg below baseline levels is enough to cause central apnea [1–5]. Thus, NREM sleep unmasks a highly reproducible hypocapnic apneic threshold, resulting in central apnea when the level of PaCO2 drops below this threshold. Using nasal mechanical ventilation, numerous studies have demonstrated that central apnea can be induced by lowering arterial PaCO2, below the apneic threshold.

With above introduction, below we discuss the pathophysiological classification of causes of CSA. So far, CSA classification has been based on PaCO2 level, and disorders classified under hypocapnic and hypercapnic categories. However, there is considerable overlap. For example, CSA associated with HFrEF is in the hypocpnic category, yet many such participants have normal PaCO2 [7]. In contrast, opioids-induced CSA is in the hypercapnic category, yet a number of such participants could have PaCO2 values within normal levels [8].

With the above introduction, below we will discuss the pathophysiological classification of causes of CSA (Table 1). We emphasize that more than one mechanism may be involved in some conditions, including opposing ones. Further, in some conditions, the mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Table 1.

Pathophysiological classification of central sleep apnea

| I. High loop gain/increased controller gain |

| 1. Heart failure |

| 2. Atrial fibrillation |

| 3. High altitude |

| 4. Idiopathic |

| 5. Acromegaly |

| 6. Treatment-emergent CSA (TECSA; Complex CSA) |

| • CPAP |

| • Nasal expiratory positive airway device |

| • Oral appliance |

| • Hypoglossal nerve stimulation |

| • Tracheostomy |

| • f. Tonsillectomy |

| • Maxillomandibular surgery |

| 7. Chronic renal failure |

| 8. Drugs |

| • Ticagleror |

| • Opioids |

| II. High loop gain/increased plant gain |

| Chronic hypercapnia |

| 1. Alveolar hypoventilation with normal pulmonary function |

| • Congenital and Primary |

| 2. Brainstem and spinal cord disorders |

| • Encephalitis |

| • Tumor |

| • Infracts |

| • Cervical cordotomy |

| • Anterior cervical spinal artery syndrome |

| 3. Neuromuscular disorders |

| • Muscular disorders |

| • Myotonic dystrophy |

| • Duchenne dystrophies, |

| • Acid maltase deficiency |

| 4. Neuromuscular junction disorders |

| • Myasthenia gravis |

| 5. Spinal cord/peripheral nerve disorders |

| • Spinal cord injury |

| • Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| • Poliomyelitis |

| III. Failure of rhythm generation (pre-Botzinger Complex) |

| 1. Drugs |

| • Opioids |

| • Sodium oxybate |

| • Baclofen |

| • Valproic acid |

| 2. Neurodegenerative disorders (synucleinopathies) |

| • Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| • Multiple system atrophy |

| • Parkinson disease |

| • Dementia with Lewy bodies |

| 3. Brainstem disorders |

| • Infarct |

| • Tumor |

| • Chiari malformation |

| IV. Miscellaneous |

| 1. Pulmonary hypertension |

| 2. Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis |

Classification of central apnea

As noted in Table 1, we have categorized various conditions based on the underlying mechanism potentially causing CSA. The loop gain (LG) model described below, accounts for CSA in a number of CVD such as heart failure. In this model, there are 2 major categories i.e. those related to increased chemical LG vs those related to elevated plant gain (PG). The disorders associated with high LG model are distinctly different from other conditions such as use of opioids, neurodegenerative disorders, stroke; conditions that could cause CSA, not based on a high LG, but rather by inhibiting rhythm generation. Please note that the taxonomy used below for various categories and disorders follow those in Table 1.

What is loop gain?

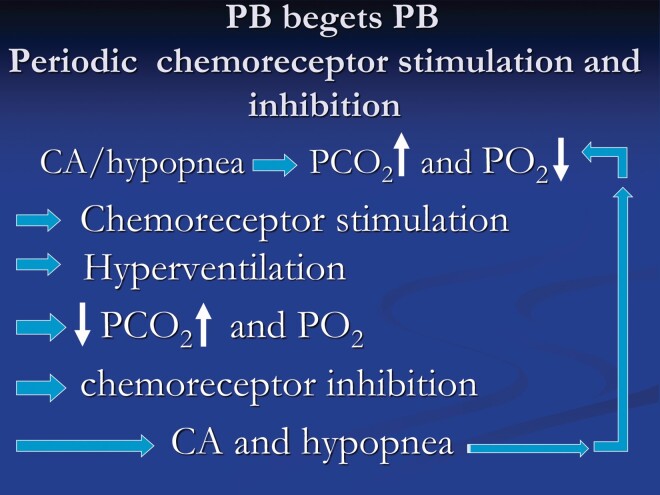

Central apnea does not occur as a single event, but as cycles of apnea/hypopnea alternating with hyperpnea (Figure 1). We adopt the engineering concept of “loop gain” (LG) (Figures 2 and 3) as a measure of ventilatory stability and susceptibility to central apnea and recurrent breathing instability [4, 9–12]. The basis for this concept is the notion that ventilatory control operates as a negative feedback closed-loop system to maintain homeostasis of blood gas tensions within a relatively narrow physiologic range, principally PaCO2. Therefore, when a breathing disturbance occurs, for example, with a short pause in breathing and Pa O2 decreases and PaCO2 increases, the peripheral and central chemoreceptors are stimulated, and ventilation increases appropriately to mitigate the disturbance. Therefore, ventilation quickly returns to normal. However, in the presence of certain conditions such as heart failure, ventilatory overshoot may occur with the ventilatory response being greater in magnitude than the disturbance. This overshoot reflects elevated LG (LG ≥ 1). When the response is greater in magnitude than the disturbance itself, ventilatory overshoot is followed by undershoot and breathing destabilizes in a periodic breathing pattern (Figures 1 and 4).

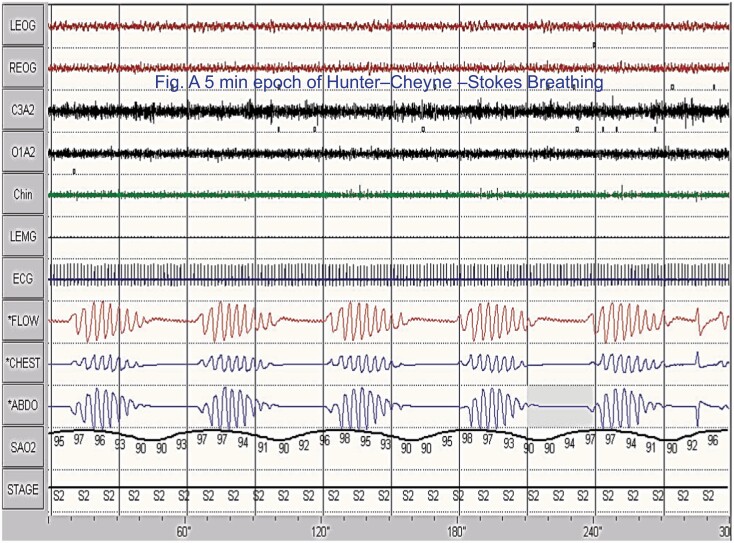

Figure 1.

A 5 min polysomnographic example of Hunter–Cheyne–Stokes breathing. Tracings are: electro-oculogram (EOG, 1and 2), electroencephalogram (EEG, 3 and 4), chin electromyogram (EMG, 5), Leg EMG (6, idle), ECG (7) airflow measured by thermocouple (8) rib cage (RC, 9), abdominal (ABD, 10), and combined (11th) excursions, and oxyhemoglobin saturation(12). Please note, airflow is absent and channels are flat consistent with central sleep apnea. Also, note the smooth and gradual changes in the thoracoabdominal excursions and in the crescendo and decrescendo arms of the cycle.

Figure 2.

Depicts the concept of loop gain (LG). When LG is less than 1, the ventilatory response to a disturbance is limited and breathing soon stabilizes (A). In contrast, when the magnitude of the ventilatory response is greater than the magnitude of the initial disturbance, the system overshoots and breathing instability occurs (B). From Javaheri and Dempsey [4].

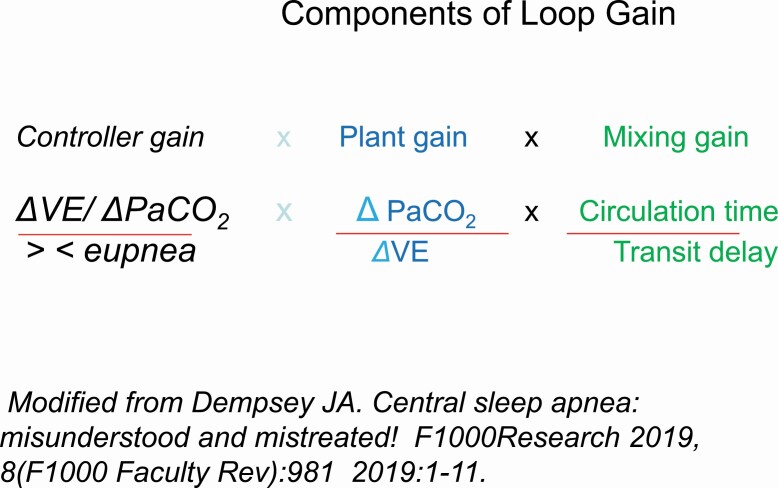

Figure 3.

Depicts the 3 components of the loop gain, consisting of the controller gain, plant gain, and the mixing gain. Loop gain represents the overall ventilatory response to a disturbance. The classic 3 components of loop gain include 1, the controller gain, the plant gain, and the mixing gain. Collectively, under normal circumstances, loop gain as a negative feedback system functions to keep arterial blood gases and pH within normal range.The controller gain is the chemoreflex control mediated by carotid bodies and central chemoreceptors. It represents the sensitivity of these receptors to changes in blood gases, above and below eupnea.

The plant gain represents the efficiency of the respiratory system to clear CO2.

The mixing gain represents the transfer of information, i.e. changes in pulmonary capillary.

Modified from Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea: misunderstood and mistreated! F1000Research 2019, 8(F1000 Faculty Rev):981 2019:1–11.

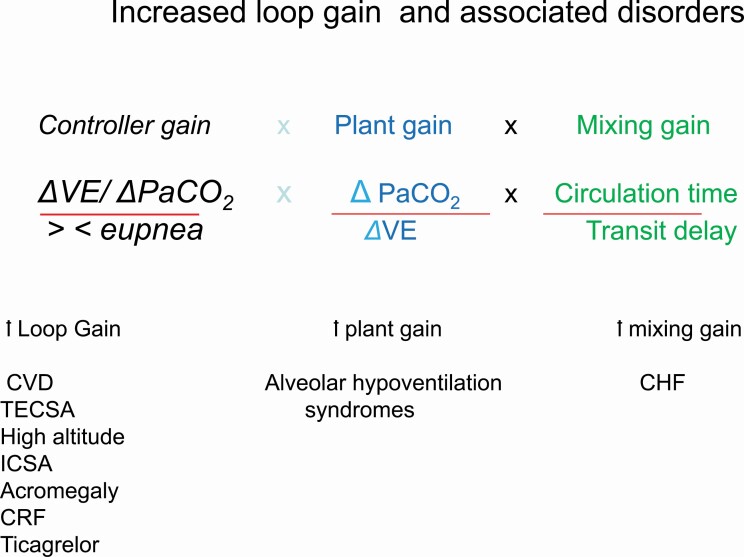

Figure 4.

The increased controller gain represents augmented chemoreflex control because of hypersensitivity of the carotid bodies and central chemoreceptors to changes in PaCO2 and PO2. The disorders associated with increased controller gain are noted (Table 1).The increased plant gain is due to increased CO2 clearance for a given change in ventilation. When plant gain is increased a small increase in ventilation, decreases PaCO2 excessively. As a restate PaCO2 is lowered below apneic threshold facilitating central apnea. the disorders associated with increased plant gain are noted (Table 1).

The mixing gain is related to increased circulation time unique to heart failure, prolonging the cycle time of periodic breathing.

Loop gain represents a composite of the overall response of the controller gain the plant gain and the mixing gain (Figure 2) [7–9]. The greater the magnitude of the controller gain (primarily the magnitude of chemoreceptors responsiveness to changes in PO2 and PaCO2), the greater the plant gain (change in PaCO2 for a change in ventilation representing the effectiveness of eliminating CO2), and mixing gain (reflecting the circulation time, defined as the time required to transfer changes in pulmonary blood PO2 and PaCO2 between the plant and the controllers), the higher the likelihood of developing periodic breathing [7, 8]. (Figure 3) Below, we briefly define the 3 components of the LG:

The controller gain represents the responsiveness of the peripheral arterial (carotid bodies), and the central chemoreceptors in the medullary brain stem to changes in PaCO2 and PO2. When the ventilatory response of these receptors to decreased PO2 or increased PaCO2 is inappropriately elevated, periodic breathing could occur, best studied in HF. Here, we emphasize that the two sets of receptors function in an interdependent fashion [10]. It is established that combined interaction of both receptors is required for CSA to occur. In animal models of CSA, isolated perfusion studies of carotid bodies, and central chemoreceptors show that neither receptor by itself can cause central apnea, in spite of severe local hypocapnia. These data strongly indicate the interdependence of the peripheral and central chemoreceptors for in the genesis of central apnea [10].

It is well established that hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses are elevated in heart failure [12, 13]. However, patients with heart failure and CSA exhibit exaggerated ventilatory response to both hypoxia and hypercapnia, when compared to those without CSA [14, 15]. Based on animal models of heart failure, reduction in carotid body blood flow leads to its sensitization with increased tonic activity a to hypoxia [16, 17]. The molecular signatures mediating upregulation of the glomus cells of the carotid bodies involve alterations in multiple neurotransmitters [17, 18]. However, the molecular mechanisms upregulating exaggerated ventilatory response to changes in CO2 have not been studied sufficiently, despite the key role that such response plays in the development of CSA in HF. This is because during NREM sleep, breathing is metabolically controlled, principally by PaCO2. In this regard, chemosensitivity to CO2 is increased both above [14, 15] and below eupnea [19]. The former, during wakefulness, is measured by the slope of CO2 rebreathing, the hypercapnic ventilatory response (HCVR), and the latter during sleep, when the level of arterial PaCO2 (PaCO2) could be lowered by mechanical ventilation imposed upon a participant for a few minutes. These two properties interact to promote periodic breathing and central apnea. Increased chemosensitivity below eupnea causes the apneic threshold to be close to the prevailing eucapnia PaCO2 (diminished CO2 reserve). Therefore, a small reduction in ventilation is enough to lower the PaCO2 below the apneic threshold causing cessation of breathing. Conversely, when an arousal follows a central apnea, increased chemosensitivity above eupnea causes exaggerated hyperventilatory response lowering the PaCO2 considerably, and upon resumption of sleep, this level of CO2 is low enough to be below apneic threshold resulting in CSA. One other feature in heart failure is increased circulation time, delaying the transfer of information of pulmonary capillary blood gas tensions to the chemoreceptors converting a negative feedback system to a positive one (see below).

Here, we note that in participants with HF, PB not only occur during sleep but also while awake and during exercise [20, 21]. This is because these components of the LG operate both during sleep and wakefulness promoting PB across 24 h. However, full blown severe PB with central apneas occur only during transition to sleep and in non-REM sleep. This is because, apneic threshold PaCO2 and CO2 sensitivity below eupnea (see below) are unmasked in NREM sleep. Central apneas do not occur during wakefulness; when, visually, we observe central apnea “while the patient is “awake”, the participant is actually dozing off and if EEG was available, it would be observed that the brain alpha waves are slowing down, an indication of transition from wakefulness to sleep.

As described above, the loop-gain framework describes a rhythmic oscillation of apnea alternating with hyperpnea. However, the complexity of the ventilatory control system introduces several variables that may affect the overall response of the system. The occurrence of central apnea is associated with several consequences that conspire to promote further breathing instability: Once ventilatory motor output completely ceases, rhythmic breathing does not resume at eupneic PaCO2, but requires an increase by 4–6 mmHg above eupnea for resumption of respiratory effort, this due to inertia of the ventilatory control system [10]. This possible explanation is that perhaps representing the time it takes before the central chemoreceptors sense the new PaCO2 level. The longer the circulation time, the longer it takes for chemoreceptors to sense alterations in pulmonary capillary blood (increased mixing gain). This means a delay in compensatory response, allowing prolongation of apnea, and subsequent excessive response. Consequently, if cardiac function changes across the night, LG changes as well. Thus, LG is not a single value, rather, it has dynamic characteristics [22]. Other factors that affect the value of the LG are changes during transitions between NREM and REM sleep, sleep position, arousal threshold, and increased LG during the night, perhaps circadian-related.

Below, we briefly discuss the role of position, arousal threshold, and changes in LG in REM and NREM sleep.

Body Position

Like obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), CSA worsens in supine position [23]. One possible mechanism is decreased lung volume in the supine position observed in healthy participants and patients with lung, heart, neuromuscular disease, or obesity [24]. Decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) is associated with increased loop gain [22], likely due to increased plant gain via reduced FRC. Likewise, narrowing of the upper airway during central apnea has been shown endoscopically [25] and by esophageal pressure monitoring [26].

Notably, Issa and Sullivan [27] reported on successful treatment of CSA in supine and suggested that CSA may be triggered by stimulation of upper airway receptors in supine position [28, 29]; this notion was corroborated empirically in a study demonstrating that negative pressure-induced deformation of the upper airway causes central apnea in awake and sleeping dogs [30].

The occurrence of pharyngeal collapse in the supine position could lead to apnea prolongation via tissue adhesion forces [31], potentially converting a central apnea to a mixed one [26]. Subsequent termination of apnea is associated with further hypoxia and hypercapnia resulting in increased controller gain, and consequent ventilatory overshoot with hypocapnia, and further apnea/hypopnea.

Arousal threshold

There is evidence that the duration of central apnea increases during NREM sleep as the night progresses [32]. Similarly, studies have shown a similar increase in the duration of obstructive events as the night progresses [33]. Potential mechanisms include a progressive decline in the arousal response to neural stimuli and/or increased LG (see below).

Changes in loop gain

LG is a dynamic property changing during sleep across the night. It has been shown that it increases late in the night and being higher in NREM sleep than in REM sleep [34]. Therefore, central apnea is rare during REM sleep, unlike OSA. This is the case for HF [35], opioids [8, 36], and PAP-emergent CSA [36, 37]. It appears that REM sleep is impervious to changes in chemical, stimuli, likely due to attenuated inhibitory response to any given magnitude of hypocapnia [38].

The augmented LG in NREM sleep as night progresses could account for increased frequency and lengthening of central apneas in the last segments of NREM sleep shown in patients with heart failure [32]. The increased CSA burden in NREM sleep later in the night be one of the reasons in part accounting for lack of positive outcome in patients with HFrEF receiving ASV, who demonstrated evidence of low adherence [39].

With the above background, below, we discuss the disorders causing CSA. The taxonomy follows the sequence in Table 1.

Disorders related to high loop gain with increased controller gain

Heart failure

Central sleep is observed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and in diastolic dysfunction [40]. However, the prevalence and mechanisms of central sleep apnea have been most extensively studied in participants with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

Several studies have shown that patients with HFrEF and CSA have high LG, characterized by increased chemosensitivity when compared to those without CSA [14, 15, 41]. Notably, increased chemical chemosensitivity as depicted by the slope of the hypercapnic ventilatory response during wakefulness, correlates strongly with apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in full night polysomnography [14]. Similarly, the slope of the hypocapnic ventilatory response during sleep, i.e. increased chemosensitivity below eupnea, is significantly steeper in those with CSA than without [19]. Increased chemosensitivity is reflected in decreased PaCO2 reserve. For the two reasons, patients with HF and increased chemosensitivity above and below eupnea are most vulnerable to developing CSA: The increased chemosensitivity above eupnea increases ventilation excessively during arousals. Consequently, when sleep resumes, PaCO2 may be below the apneic threshold, thus causing central apnea. With central apnea PaCO2 increases causing hyperventilation which lowers PaCO2 fostering cycles of apnea-hyperventilation to recur. This pattern was first described by Hunter, four decades before Cheyne reported it. For this reason, we refer to the pattern as Hunter–Cheyne–Stokes breathing (reviewed in reference [44]). This pattern is unique and is characterized by prolonged cycle time because of prolonged circulation time (increased mixing gain) (Figure 1). The pattern is distinctly different from medications-induced CSA shown later.

As noted earlier, periodic breathing occurs across 24 h, though it is most pronounced during sleep. This is partly related to the state of sleep itself, but also exaggerated in supine position [42]. In this position, rostrally shifting fluid from lower extremities can become compartmentalized in the neck area or in the lung. The former causes congestion and swelling of the pharyngeal area promoting upper airway occlusion. The latter, with fluid in the lung, particularly with HF-related compromised central circulation, pulmonary congestion could occur increasing pulmonary capillary pressure. This could promote more periodic breathing, as increased pulmonary capillary pressure, increases the LG, for reasons not quite understood [43]. Here, we note that underlying mechanism of PB and CSA are complex and as discussed in detail elsewhere [4, 5, 44], several other factors such as changes in cerebral blood flow, position and state of sleep (reviewed above), collectively could contribute to PB.

It has been commonly assumed that HCSB is associated with severe left ventricular dysfunction and HF. However, HCSB is quite common in asymptomatic participants with left ventricular dysfunction [45], and notably, evidence is accumulating that CSA/HCSB is not necessarily the consequence of symptomatic severe left ventricular dysfunction. In a long-term prospective study of 2865 community-dwelling older men who underwent baseline polysomnography and followed for a mean 7.3 years, elevated CAI/HCSB was significantly associated with increased risk of decompensated heart failure and/or development of clinical heart failure [46].

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained rhythm disorder, affecting 33 million individuals worldwide, and is associated with an increased risk of cerebral and cardiovascular complications, as well as excess mortality [47]. The relationship between AF and CSA is bidirectional. CSA is common in patients with atrial fibrillation, and CSA could herald incident AF. Atrial fibrillation appears to be a major risk factor for the presence of CSA among patients with HFrEF [48, 49] and HFpEF [50]. In a prospective study of100 participants with HFrEF, 80% of those with AF had CSA [49]. The association is less in HFpEF; among 150 patients with HFpEF and AF, CSA was observed in 31% of the participants [50]. In both aforementioned studies, CSA occurred in association with HCSB pattern suggesting that CSA is due to high LG. AF is commonly associated with dilated left atrium [51]; as noted earlier, increased mean left atrial pressure could promote CSA [43]. This was demonstrated in naturally sleeping dogs, who exhibited periodic breathing when left atrial pressure was increased by inflating a balloon in the left atrium [43]. In these chronically instrumented animals, CO2 sensitivity below eupnea was increased with subsequent narrowing of PaCO2 reserve, mediating development of CSA. Consistent with the aforementioned animal study, in a study of 25 patients with HFrEF and CSA, increased left atrial volume index calculated from echocardiography was associated with heightened CO2 chemosensitivity and greater frequency of CSA. We note that at times, right atrium may trigger AF [52] in which case the aforementioned mechanisms may not apply.

The prevalence of AF is also high in patients with” idiopathic CSA”. In a study involving 60 consecutive patients with idiopathic CSA, 27% had atrial fibrillation [53]. It is plausible that AF was the cause of CSA; in other words, CSA was not idiopathic. Mechanistically, AF may be a cause of CSA by increasing left atrial pressure and hence decreasing the PaCO2 reserve, as discussed above. Therefore, we recommend that an electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram be performed for all patients with “idiopathic CSA”.

Finally, CSA could also be a cause of incident AF. At least two observational longitudinal studies of several years duration, showed that baseline CSA heralds the development of future AF. In the Sleep Heart Study, 2912 individuals were followed for 5.3 years. CSA was a predictor of incident AF in all adjusted models with 2- to 3-fold increase in the odds ratio [54]. This OR was similar to that of the multicenter Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study [55] which followed 843 older adults followed for an average of 6.5 years. In the adjusted model, those with CSA at baseline were 2.6 times more likely to develop HF than those without CSA.

High altitude

At altitudes above 3000 m, almost all healthy participants develop periodic breathing [56–58]. The principal reason for periodic breathing and CSA during sleep in hypoxic environment is likely the augmented chemical controller gain—as evidenced by the steep increase in CO2 response slope as well as well as increased ventilatory responsiveness to hypoxia [59].

The pattern of PB and CSA at high altitude differs morphologically from CSA in HF. These unique patterns are easily recognizable. In contrast to PB in HF, PB at high altitude is not smooth, not crescendo–decrescendo in nature, and without a prolonged cycle time. At high altitude, PB is repeated cluster-type pattern of a few augmented breaths followed by apnea. The central apnea and the cycle length are much shorter, 20–30 s in duration. The reason for these differences is the absence of prolonged circulation time, the pathological feature of HF. However, there are some similarities. As noted before, PB is state-independent(occurs while awake or sleep), and like in HF, PB at high altitude may also occur in wakefulness, during periods of drowsiness, and even during physical exercise at extreme altitude [60]. Like in HF, PB at high altitude occurs primarily in NREM sleep. Like in HF, hypocapnia, per se should decrease the plant gain and potentially counteracting hypoxia related chemosensitivity increased chemosensitivity. The balance of these 2 opposing elements of LG determines the magnitude and severity of PB. Finally, like in heart failure, treatment with oxygen improves CSA at high altitude, as in both conditions, periodic breathing is mediated by elevated chemical loop gain.

Idiopathic

When all identifiable causes of CSA noted in Table 1 have been eliminated, CSA is referred to as “primary or idiopathic (ICSA), a rare disease of unknown etiology. The true prevalence of ICSA in the general population is not known but among participants referred to a sleep center, the prevalence varies from 4% to 7% of those with CSA [61]. The prevalence increases further among participants with polysomnographic evidence of CSA [62]. In a study of 151 consecutive participants who had CSA,16 participants (11%) participants had ICSA [62]. Full night polysomnography showed that ICSA was associated with poor sleep architecture, repeated arousals and desaturation, poor quality of life measured by several metrics(including short form 12), and excessive daytime sleepiness [62]. Long-term treatment of ICSA improves sleep disordered breathing, arousals, and desaturation with consequent improvement in daytime symptoms and quality of life [62]. ICSA is categorized as high LG disorder, as such patients exhibit elevated chemical LG (increased controller gain) characterized by the increased slope of the hypercapnic ventilatory response [63]. With sleep fragmentation and arousals, hyperventilation occurs lowering PaCO2 below the apneic threshold PaCO2 causing central apnea [64].

Acromegaly

Both OSA and CSA have been reported in participants with acromegaly [65–67]. In one study of 53 patients with acromegaly, 14 (33%) had predominantly CSA [65], whereas in another study [67], the prevalence of CSA was much lower, though in this study [67] only 29 patients had active disease, of whom 2 had CSA and 1 mixed apnea.

Patients with acromegaly and CSA exhibit augmented hypercapnic ventilatory response which increases the loop gain (the controller gain) and could potentially increase the propensity to develop CSA [65]. The mechanisms mediating increased chemosensitivity remain to be determined. However, treatment of acromegaly with octreotide is associated with decreased apnea severity, both central and obstructive.

It is also noted that patients with acromegaly may suffer from cardiac dysfunction which as noted earlier could contribute to increased chemosensitivity and the development of CSA.

Treatment-emergent CSA (TECSA; complex CSA)

Appearance of central sleep apnea after treatment with CPAP was referred to as complex sleep apnea coined by Thomas and colleagues [68]. However, it is best referred to as “Treatment-Emergent Central Sleep Apnea”(TECSA), as CSA may appear with both CPAP [36]as well as other therapeutic modalities of OSA [69].

A study of 1286 participants with OSA [36] and without known heart disease, described different subtypes of CPAP-emergent CSA defined as CAI ≥ 5 per hour of sleep. In this study [36], after an initial full night attendant diagnostic polysomnography, participants underwent two additional full night CPAP titration studies. The subtypes included, a group with a transitory CPAP-emergent CSA (first CPAP study) which in most cases disappeared after about 8 weeks of use of CPAP (second CPAP study), at the same CPAP level that induced CSA during the first titration. Second, was a minority group who had CSA on both the first and second CPAP titration (CPAP-persistent CSA); the third group, CPAP-resistant CSA, consisted of a number of participants with OSA who had some component of CSA at baseline polysomnography which did not go away after 8 weeks of CPAP use, in spite of good adherence. In a propensity matching [36], those with most severe OSA, atrial fibrillation, or CSA on baseline polysomnography had more incident CPAP-emergent CSA than the matched group. In addition, some of the participants with OSA and CPAP resistant were on opioids. Excluding opioids as a potential reason for emergent CSA, we hypothesize that an elevated LG is the underlying reason for emergent CSA discussed below.

Multiple polysomnographic and clinical findings at baseline have been shown to be associated with emergent CSA. These include presence of severe OSA, presence of CSA, presence of mixed apnea. These conditions could herald presence of elevated LG. As noted above [36], severe OSA (AHI ≥ 30/h of sleep) at baseline [36] was associated with CPAP-emergent CSA, and severe OSA, as opposed to milder cases has been shown to be associated with an elevated LG [70]. In a physiological overnight split polysomnographic study [71], the elevated slope of the dynamic hypercapnic ventilatory response and elevated PaCO2 initially, decreased with CPAP treatment. The reduction in the slope suggests that elevated loop gain is reversible. This was consistent with the study of Salloum et al [72] who demonstrated increased propensity for central apnea in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, which resolved after a 6-week therapy with CPAP. The aforementioned physiological studies corroborate clinical studies showing that in most patients with severe OSA, CPAP-emergent CSA disappeared with tracheostomy [73, 74] or use of CPAP [36].As noted, presence of CSA or mixed apnea at baseline is also associated with CPAP-emergent CSA related to a high loop gain [75]. Thus, elevated LG may account for persistent CSA on CPAP [76]. Finally, we note that the most common association of TECSA has been with CPAP, which we suggest could be mediated by the additive effect of CPAP-related increased lung volume activating stretch receptors (Herring–Breuer reflex) further facilitating development of CSA.

Chronic renal failure

Sleep disordered breathing is common in individuals with chronic renal failure, and the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea increase as kidney function declines [77]. In fact, SDB is present in 50% to 70% patients living with ESRD [78]. Though OSA is most prevalent, CSA occurs in a subset of patients [79]. Notably, fluid removal by ultrafiltration immediately improves sleep apnea in patients with ESRD [80], likely through removal of fluid that has accumulated via cephalad movement of fluid into the neck area and the lungs promoting OSA and CSA [42].

Evidence in the literature indicates that high loop gain contributes to SDB in patients with ESRD. Beecroft and colleagues investigated chemosensitivity in patients with ESRD. The major finding was increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia and hypercapnia in participants with ESRD and sleep apnea compared to non-apneic participants [79].

Medications

Ticagrelor

The P2Y12 receptor is a G Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) in platelets, where it plays a critical role in platelet aggregation and arterial thrombosis. This receptor has been a target of antithrombotic drugs used in treatment of coronary syndrome [81]. Ticagrelor is an oral, reversible, inhibitor of the adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 with pronounced platelet inhibition [82, 83]. There are reports of dyspnea and periodic breathing after initiation of ticagrelor [84, 85]. Gionnoni and colleagues reported on few patients with normal systolic and diastolic function, as well as normal spirometry who had PB with CSA on ticagrelor. Discontinuation of the medication was associated with decreased hypercapnic ventilatory response and the disappearance of periodic breathing (Figure 3). In another study of 80 patients receiving ticagrelor, 24 (30%) had CSAH with AHI ≥/hour 15 [85]. The mechanism (s) underlying increased chemosensitivity after ticagrelor administration remains unclear. However, independent of the mechanism, CSA is associated with adverse consequences including hypoxemia and increased sympathetic activity which could have adverse cardiovascular consequences particularly in participants with acute coronary syndrome.

Opioids

The pathophysiology of opioid induced breathing disturbances during sleep is complex, including impairment of the rhythmogenesis discussed later, motor neuron output (leading to obstructive hypopneas), influence on hypoxic ventilatory response, sustained diminution of ventilation (clinically sustained hypoventilation [86, 87]). Notably, a single study [88] has sown elevated HVR in long-term users of methadone. If findings of this study are confirmed, and the elevated HVR is a class action, then opioids could promote CSA by elevated loop gain. However, opioids-mu receptor is inhibitory and opioids are known to depress ventilation, both HVR and HCVR [89], for which reason the methadone study should be confirmed.

In a later section, we discuss the animal data showing how opioids induce central apnea, via their effects on pre-Botzinger complex. However, the pattern of periodic breathing associated with use of opioids (Figure 4) is quite different from that of heart failure (Figure 5) which is related to a high loop gain

Figure 5.

The figure depicts the important role of augmented chemical control in promoting periodic breathing in heart failure. Chemostimulation increases ventilation lowering arterial PaCO2 towards or below apneic threshold causing chemoinhibition with consequent hypopnea and central apnea. With diminished ventilation, PaCO2 increases and PO2 decreases causing chemostimulation and the cycle keeps repeating.

Disorders related to high loop gain with increased plant Gain

Conditions associated with chronic hypercapnia could be associated with central apnea and reduced for several reasons. One mechanism is increased plant gain dictated by the hyperbolic alveolar ventilation curve. In addition, diminished ventilation could also be impart related to the pathology involving respiratory centers.

Based on the isometabolic alveolar ventilation curve at elevated PaCO2 levels, a small increment in ventilation causes a large drop in PaCO2 and vice versa Therefore, when ventilation increases slightly (e.g. with an arousal from sleep), change in position or sleep stage, a considerable drop in PaCO2 occurs. Consequently, if PaCO2 decreases below the apneic threshold, central apnea or long expiratory pause occurs, which is sustained until PaCO2 rises above the apneic threshold for PaCO2. Conversely, if ventilation decreases slightly, the PaCO2will increase considerably. Therefore, with sleep onset, and removal of the wakefulness drive to breathe, ventilation decreases, which normally increases PaCO2 slightly, but in the presence of hypercapnia, the rise in PaCO2 is considerable such that the higher the baseline PaCO2, the higher the rise in sleep onset PaCO2. These exaggerated fluctuations in PaCO2 are due to increased plant gain at elevated PaCO2 level. Increased plant gain at elevated PaCO2 level, is in contract to decreased plant gain at low PaCO2 level protecting against developing CSA. Here, we note that with hypercapnia, the apneic threshold is also elevated and is close to the elevated eupneic PaCO2 [90].

Alveolar hypoventilation is the hallmark of a plethora of conditions (Table 1), which are beyond the scope of this review. However, some of these disorders could occur without hypercapnia in which case increased plant gain does not apply, if CSA is present. Characteristically, patients with chronic hypercapnia demonstrate worsening of hypoventilation with diminutive tidal volumes, rather than repetitive central apneas. As noted above, diminished ventilation could also be impart related to the pathology involving respiratory centers when present. An example is CCHS [91], a rare disorder, due to the paired-like homeobox 2B (PHOX2B) gene mutation in which, occasionally central sleep apneas are observed [92, 93]. CCHS is a disorder of infancy; adult-onset CCHS is rare [93].

Spinal cord injury(SCI) has recently been shown to be associated with increased plant gain. The prevalence of SDB is higher among individuals living with SCI, compared to the general population. In addition, people living with cervical SCI have a very high prevalence of central apnea. Sankari et al [94] found that 60% of patients with cervical SCI demonstrated central SDB, a finding that was corroborated by a systematic review [95]. In fact, tetraplegia is potentially an independent risk factor for CSA, owing to increased plant gain [96], the latter is due to mild sleep related hypoventilation caused by the intercostal muscle paralysis [97, 98]. Additional risk factors include the use of opioid analgesics including baclofen.

We also emphasize that in some of these disorders such as stroke and Chiari malformation noted in Table 1, CSA could occur without hypercapnia. Under such circumstances, increased plant gain does not apply, and CSA is caused by the pathological involvement of the brainstem respiratory centers (please see disorders under section Conditions associated with failure of rhythm generation (pre-Botzinger Complex).

Conditions associated with failure of rhythm generation (pre-Botzinger Complex)

Medications

Studies of Feldman and colleagues have implicated the pre-Botzinger complex (preBöt-Complex) as the site of inspiratory rhythmogenesis in mammals [99–101]. Accordingly, there are two respiratory rhythm generators in the ventrolateral medullary portion of the neonatal rat brainstem, the preBöt-Complex and the retrotrapezoid nucleus/parafacial respiratory group (RTN/pFRG). These two distinct neuronal aggregates have intrinsic pacemaker capability and generate normal respiratory rhythm. The preBöt-Complex is the dominant site for inspiration and lesions in this area causes irregular breathing pattern during wakefulness and apneas during sleep. These findings in neonatal rats are similar to those in adult rats, injected with toxin saporin conjugated to substance P, which selectively ablates neurons expressing neurokinin 1 receptor or substance P mixed with saporin (unconjugated), which does not ablate neurons (n = 4), was injected bilaterally into the preBot-Complex. demonstrating increasing loss of preBöt-Complex neurokinin 1 receptor neurons leads to central apneas in REM sleep, followed by NREM sleep, and eventually in wakefulness [101, 102].

Neurons in the preBöt-Complex have a number of receptors including NK1, μ-opioid, and GABA B receptors [103]. An animal study that demonstrates intravenous as well as that selective application of opioid agonist to the neurons of preBöt-Complex depresses breathing, and importantly, selective application of naloxone to the neurons of preBöt-Complex, a mu receptor antagonist used in man to reverse opioids-induced respiratory depression, reverses depressed breathing [104, 105].

Multiple polysomnographic studies in human have shown that opioids cause CSA [106, 107], and CPAP-emergent CSA; which are eliminated by detoxification [107]. Detoxification, is perhaps the best approach to treat opioid-induced CSA, but difficult to achieve.

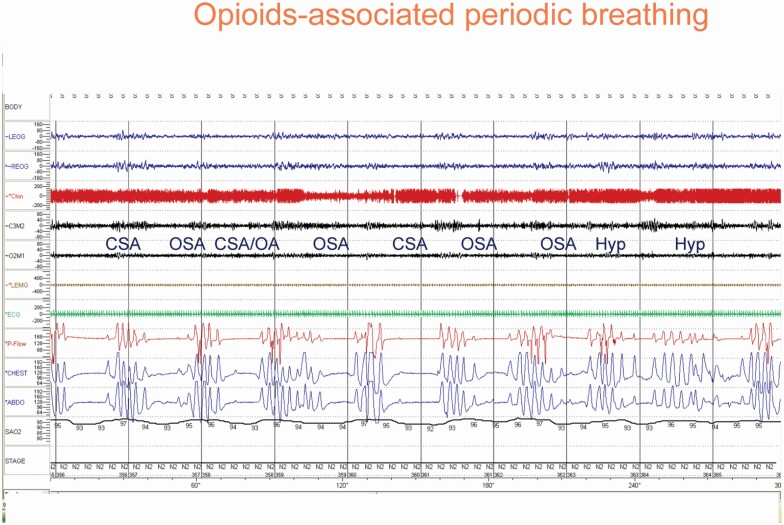

The pattern of breathing associated with opioid is also unique and is characterized by ataxic breathing, distinctly different from HCSB (Figure 6, vs Figure 1). Central apneas are variable in duration and short cycles (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

An example of sleep-disordered breathing in association with opioid use. The breathing is quite ataxic, in contrast to that in heart failure(Figure 1). CSA = central sleep apnea; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; Hyp = hypopnea.

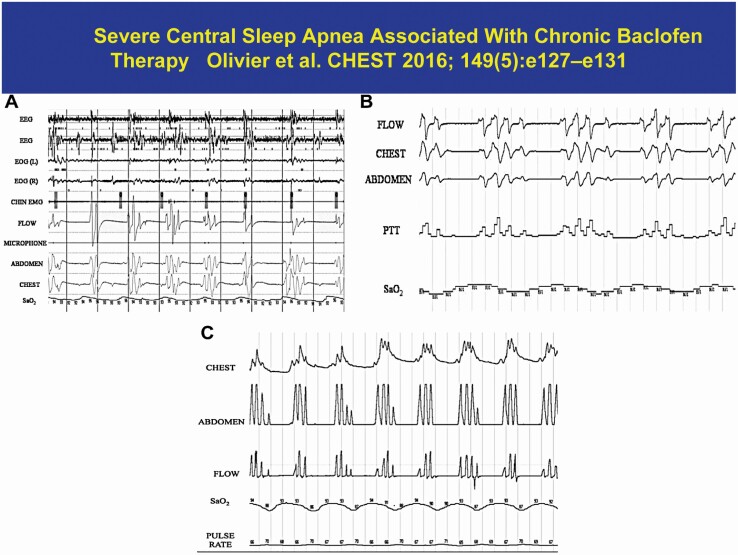

A number of medications have been associated with CSA potentially affecting preBöt-Complex. There are several reports of central apnea in association with baclofen use (Figure 7). Baclofen, a Gamma-aminobutyric acid-B agonist (GABA B agonist), is used as a muscle-relaxant with antispasmodic properties and to treat severe spasticity associated with spinal cord lesions or neurologic disorders [108]. Likewise, there are a few case reports implicating sodium oxybate, the sodium salt of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), an endogenous compound and metabolite of the neurotransmitter GABA that is used for treatment of cataplexy [109, 110]. The mechanism of action is hypothesized to be mediated through GABAB actions at noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons. Finally, valproic acid, an anticonvulsant, thought to block voltage-gated sodium channels and hence leads to increased brain levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and CSA [111] One possible common pathway is the possibility that these depressant medications act on the inspiratory neurons in preBöt-Complex to cause CSA. In this complex, μ-opioid receptors and GABA B receptors are colocalized, and the pattern of breathing associated with aforementioned medications resembles that of opioids.

Figure 7.

An example of baclofen induced central sleep apnea. Please note the pattern is similar to that of opioids in Figure 6.

Neurodegenerative disorders (synucleinopathies)

Pathologically, these disorders are characterized by intracellular alpha-synuclein inclusions with involvement of medullary neurons invoked in breathing, in particular with degeneration of the preBöt-Cmp neurons. Feldman and colleagues have suggested that sleep disordered breathing in neurodegenerative disorders including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [112], multiple systems atrophy [113], or Parkinson disease [114] are due to loss of neurons in preBöt-Comp, in whom NK1R neurons are depleted significantly suggesting substantial damage to the preBöt-Comp [115]. Similar pathological alterations have been reported in dementia with Lewy bodies [116].

Brainstem disorders

A number of brainstem disorders, such as stroke and Chiari malformation (Table 1) can cause CSA with or without hypercapnia. In a meta-analysis [117] of 2343 patients in 29 studies of stroke and TIA, 38% had an AHI of more than 20 per hour, with CSA accounting for 7% of the disorders. In most patients, however, CSA resolves with time, perhaps as inflammation and edema subside [118]. However, CSA and periodic breathing resembling HCSB, may persist in the presence of comorbid LV systolic dysfunction [119].

Central apnea may also be caused by Chiari malformation a structural abnormality of the central nervous system related to the descend of the cerebellar tonsils and brain stem through the foramen magnum [120]. Notably, CSA improves with surgery [121], suggesting that involvement of brainstem respiratory centers is reversible, an observation similar to evolution of CSA from acute to chronic settings.

Summary

In this monograph, we have presented a new approach and classification of central sleep apnea. This classification is based on the mechanism of action of the various causes of CSA. The classification differs from previous classification which primarily was based on the level of arterial PaCO2. The classification should direct therapy targeting to the mechanism underlying CSA. For example for the high LG category medications such as buspirone and oxygen in HF. In medication-induced CSA, withdrawal of the offending medication when possible, replacing with another alternative (Clopidogrel for ticagrelor), and eventually an antagonist (ampakine for opioids).

Contributor Information

Shahrokh Javaheri, Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine, Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Division of Pulmonary Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

M Safwan Badr, Department of Internal Medicine, Liborio Tranchida, MD, Endowed Professor of Medicine, Wayne State University School of Medicine, University Health Center, Detroit, MI, USA.

Funding

Dr. M. S. Badr was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Merit Review #1I01CX001040 and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of Health #R01HL-130552.

Disclosure Statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Skatrud JB, et al. Interaction of sleep state and chemical stimuli in sustaining rhythmic ventilation. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1983;55(3):813–822. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.3.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Badr MS, et al. Central sleep apnea: a brief review. Curr Pulmonol Rep. 2019;8(1):14–21. doi: 10.1007/s13665-019-0221-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dempsey JA. . Crossing the apnoeic threshold: causes and consequences. Exp Physiol. 2005;90(1):13–24. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Javaheri S, et al. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):141–163. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea: misunderstood and mistreated!. F1000Res. 2019;8:981. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18358.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKay LC, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing after targeted ablation of preBotzinger complex neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(9):1142–1144. doi: 10.1038/nn1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Javaheri S. Central sleep apnea and heart failure. Circulation. 2000;342:293–294. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Javaheri S, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for treatment of opioids-associated central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:637–643. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khoo MC, et al. Sleep-induced periodic breathing and apnea: a theoretical study. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1991;70(5):2014–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leevers AM, et al. Apnea after normocapnic mechanical ventilation during NREM sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1994;77(5):2079–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blain GM, et al. Peripheral chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO(2). J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 13):2455–2471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giannoni A, et al. Combined increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia and hypercapnia as a prognosticator in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ponikowski P, et al. Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity: an ominous sign in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104(5):544–549. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Javaheri SA. mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(13):949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Solin P, et al. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2194–2200. PMID: 11112137. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ding Y, et al. Role of blood flow in carotid body chemoreflex function in heart failure. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 1):245–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prabhakhar NR, et al. Tasting arterial blood: what do the carotid chemoreceptors sense? Front Physiol. 2014;5:524. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schultz HD, et al. Role of the Carotid body chemoreflex in the pathophysiology of heart failure: a perspective from animal studies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;860:167–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18440-1_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xie A, et al. Apnea-hypopnea threshold for CO2 in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1245–1250. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-022OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emdin M, et al. Prognostic significance of central apneas throughout a 24-hour period in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(11):1351–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giannoni A, et al. Upright Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2934–2946. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joosten SA, et al. Dynamic loop gain increases upon adopting the supine body position during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirology. 2017;22(8):1662–1669. doi: 10.1111/resp.13108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sahlin C, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and supine dependency. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(5):829–833. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00107904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katz S, et al. The effect of body position on pulmonary function: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0723-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Badr MS, et al. Pharyngeal narrowing/occlusion during central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1995;78(5):1806–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowdell WT, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration presenting as sleep apnea syndrome. Clinical and polysomnographic features. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(4 Pt 1):871–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Issa FG, et al. Reversal of central sleep apnea using nasal CPAP. Chest. 1986;90(2):165–171. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.2.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hwang JC, et al. Receptors responding to changes in upper airway pressure. Respir Physiol. 1984;55(3):355–366. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(84)90057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mathew OP, et al. Genioglossus muscle responses to upper airway pressure changes: afferent pathways. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;52(2):445–450. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.2.445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harms CA, et al. Negative pressure-induced deformation of the upper airway causes central apnea in awake and sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1996;80(5):1528–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morrell MJ, et al. Effect of surfactant on pharyngeal mechanics in sleeping humans: implications for sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(2):451–457. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00273702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Javaheri S, et al. In patients with heart failure the burden of central sleep apnea increases in the late sleep hours. Sleep. 2019;42(1). PMID: 30325462; PMCID: PMC6609878. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montserrat JM, et al. Mechanism of apnea lengthening across the night in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4 Pt 1):988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landry SA, et al. Ventilatory control sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea is sleep stage dependent. Sleep. 2018;41(5). PMID: 29741725; PMCID: PMC5946836. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Javaheri S, et al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97(21):2154–2159. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Javaheri S, et al. The prevalence and natural history of complex sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):205–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zeineddine S, et al. Treatment-emergent central apnea: physiologic mechanisms informing clinical practice. Chest. 2021;159(6):2449–2457. PMID: 33497650. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xi L, et al. Effects of rapid-eye-movement sleep on the apneic threshold in dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1993;75(3):1129–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Javaheri S, et al. SERVE-HF: more questions than answers. Chest 2016;149(4):900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Javaheri S, et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):841–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Topor, ZL, et al. Dynamic ventilatory response to CO2 in congestive heart failure patients with and without central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91: 408–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yumino D, et al. Nocturnal rostral fluid shift: a unifying concept for the pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea in men with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;121(14):1598–1605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chenuel BJ, et al. Increased propensity for apnea in response to acute elevations in left atrial pressure during sleep in the dog. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;101(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Javaheri S. Heart failure. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Goldstein C, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 7/e. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2022: 1462–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lanfranchi PA, et al. Central sleep apnea in left ventricular dysfunction: prevalence and implications for arrhythmic risk. Circulation. 2003;107(5):727–732. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000049641.11675.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Javaheri S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and incident heart failure in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(5):561–568. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0536OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chugh SS, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129(8):837–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sin DD, et al. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(4):1101–1106. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Javaheri S. Sleep disorders in systolic heart failure: a prospective study of 100 male patients. The final report. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bitter T, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with atrial fibrillation and normal systolic left ventricular function. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 2009;106(10):164–170. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Calvin AD, et al. . Left atrial size, chemosensitivity, and central sleep apnea in heart failure. Chest. 2014;146(1):96–103. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Haïssaguerre M, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leung RS, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and central sleep apnea. Sleep. 2005;28(12):1543–1546. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.12.1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tung P, et al. Obstructive and central sleep apnea and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in a Community Cohort of Men and Women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7):e004500. PMID: 28668820; PMCID: PMC5586257. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. May AM, et al. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(7):783–791. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1523OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Manning E, et al. Sleep and breathing at high altitude. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Goldstein C, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 7/e. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2022: 1389–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Burgess KR, et al. Central sleep apnea at high altitude. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;903:275–283. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7678-9_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Burgess KR, et al. Central and obstructive sleep apnoea during ascent to high altitude. Respirology. 2004;9(2):222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nakayama H, et al. Effect of ventilatory drive on carbon dioxide sensitivity below eupnea during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1251–1260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Garde A, et al. Time-varying signal analysis to detect high-altitude periodic breathing in climbers ascending to extreme altitude. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2015;53(8):699–712. doi: 10.1007/s11517-015-1275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task F. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL:2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Javaheri S, et al. . Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation to treat idiopathic central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(12):2099–2107. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xie A, et al. Hypocapnia and increased ventilatory responsiveness in patients with idiopathic central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):1950–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grunstein RR, et al. Central sleep apnea is associated with increased ventilatory response to carbon dioxide and hypersecretion of growth hormone in patients with acromegaly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(2):496–502. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Xie A, et al. Interaction of hyperventilation and arousal in the pathogenesis of idiopathic central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(2):489–495. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Grunstein RR, et al. Effect of octreotide, a somatostatin analog, on sleep apnea in patients with acromegaly. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(7):478–483. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-7-199410010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roemmler J, et al. Elevated incidence of sleep apnoea in acromegaly-correlation to disease activity. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(4):1247–1253. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0641-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gilmartin GS, et al. Recognition and management of complex sleep-disordered breathing. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11(6):485–493. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000183061.98665.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Javaheri S., et al. Central sleep apnoea. In: Elliott M, Nava S, Schönhofer B, eds. Non-Invasive Ventilation and Weaning: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, New York, London:Taylor & Francis Group; 2019: Chapter 43: 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Younes M, et al. Chemical control stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(5):1181–1190. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2007013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Loewen A, et al. Determinants of ventilatory instability in obstructive sleep apnea: inherent or acquired? Sleep. 2009;32(10):1355–1365. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.10.1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Salloum A, et al. Increased propensity for central apnea in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(2):189–193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1658OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Coccagna G, et al. Tracheostomy in hypersomnia with periodic breathing. Bulletin de physio-pathologie respiratoire. 1972;8(5):1217–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Guilleminault C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and tracheostomy. Long-term follow-up experience. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141(8):985–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pavsic K, et al. Mixed apnea metrics in obstructive sleep apnea predict treatment-emergent central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(6):772–775. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202007-2816LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stanchina M, et al. Clinical use of loop gain measures to determine continuous positive airway pressure efficacy in patients with complex sleep apnea. A pilot study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(9):1351–1357. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201410-469BC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nicholl DDM, et al. Declining kidney function increases the prevalence of sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxia. Chest. 2012;141(6):1422–1430. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kraus MA, et al. Sleep apnea in renal failure. Adv Perit Dial. 1997;13:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Beecroft J, et al. Enhanced chemo-responsiveness in patients with sleep apnoea and end-stage renal disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(1):151–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00075405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lyons OD, et al. Effect of ultrafiltration on sleep apnea and sleep structure in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(11):1287–1294. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2288OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gachet C. P2Y(12) receptors in platelets and other hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8(3):609–619. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9303-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wallentin L, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Storey RF, et al. Incidence of dyspnea and assessment of cardiac and pulmonary function in patients with stable coronary artery disease receiving ticagrelor, clopidogrel, or placebo in the ONSET/OFFSET study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(3):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Giannoni A, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration, chemoreflex, and ticagrelor-related dyspnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):1004–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1601662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Meurin P, et al. Central sleep apnea after acute coronary syndrome and association with ticagrelor use. Sleep Med. 2021;80:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chowdhuri S, et al. Sleep disordered breathing caused by chronic opioid use: diverse manifestations and their management. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(4):573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Javaheri S, et al. Opioids-Induced central sleep apnea: mechanisms and therapies. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Teichtahl H, et al. Ventilatory responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in stable methadone maintenance treatment patients. Chest. 2005;128(3):1339–1347. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Weil JV, et al. Diminished ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia after morphine in normal man. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(21):1103–1106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197505222922106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Boden AG, et al. Apneic threshold for CO2 in the anesthetized rat: fundamental properties under steady-state conditions. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85(3): 898–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Weese-Mayer DE, et al. An official ATS clinical policy statement: congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: genetic basis, diagnosis, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):626–644. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1069ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Weese-Mayer DE, et al. ATS clinical policy statement: congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Genetic basis, diagnosis and management. Rev Mal Respir. 2013;30(8):706–733. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hino A, et al. Adult cases of late-onset congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and paired-like homeobox 2B-mutation carriers: an additional case report and pooled analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(11):1891–1900. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sankari A, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in chronic spinal cord injury. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(1):65–72. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chiodo AE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(4):374–382. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2015.1126449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sankari A, et al. Tetraplegia is a risk factor for central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;116(3):345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bascom AT, et al. Sleep onset hypoventilation in chronic spinal cord injury. Physiol Rep. 2015;3(8):e12490. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Sankari A, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and spinal cord injury: a state-of-the-art review. Chest. 2019;155(2):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Feldman JL, et al. Looking for inspiration: new perspectives on respiratory rhythm. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(3):232–242. doi: 10.1038/nrn1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. McKay LC, et al. Unilateral ablation of pre-Botzinger complex disrupts breathing during sleep but not wakefulness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(1):89–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1901OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Nattie EE, et al. Substance P-saporin lesion of neurons with NK1 receptors in one chemoreceptor site in rats decreases ventilation and chemosensitivity. J Physiol. 2002;544(Pt 2):603–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Alheid GF, et al. The chemical neuroanatomy of breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164(1-2):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Montandon G, et al. PreBotzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons mediate opioid-induced respiratory depression. J Neurosci. 2011;31(4):1292–1301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4611-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Varga AG, et al. Differential impact of two critical respiratory centres in opioid-induced respiratory depression in awake mice. J Physiol. 2020;598(1):189–205. doi: 10.1113/JP278612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Farney RJ, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing associated with long-term opioid therapy. Chest. 2003;123(2):632–639. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Javaheri S, et al. Opioids cause central and complex sleep apnea in humans and reversal with discontinuation: a plea for detoxification. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(6):829–833. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Olivier PY, et al. Severe central sleep apnea associated with chronic baclofen therapy: a case series. Chest. 2016;149(5):e127–e131. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Bensmail D, et al. Pilot study assessing the impact of intrathecal baclofen administration mode on sleep-related respiratory parameters. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(1):96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Frase L, et al. Sodium oxybate-induced central sleep apneas. Sleep Med. 2013;14(9):922–924. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Heshmati A. Central Sleep apnea with sodium oxybate in a pediatric patient. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(3):515–517. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Guichard K, et al. Association of Valproic acid with central sleep apnea syndrome: two case reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(6):681–684. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ferguson KA, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chest. 1996;110(3):664–669. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Munschauer FE, et al. Abnormal respiration and sudden death during sleep in multiple system atrophy with autonomic failure. Neurology. 1990;40(4):677–679. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.4.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Maria B, et al. Sleep breathing disorders in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Respir Med. 2003;97(10):1151–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00188-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Benarroch EE, et al. Depletion of ventromedullary NK-1 receptor-immunoreactive neurons in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 10):2183–2190. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Presti MF, et al. Degeneration of brainstem respiratory neurons in dementia with Lewy bodies. Sleep. 2014;37(2):373–378. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Johnson KG, et al. Frequency of sleep apnea in stroke and TIA patients: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(2):131–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Parra O, et al. Time course of sleep-related breathing disorders in first-ever stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Nopmaneejumruslers C, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration in stroke: relationship to hypocapnia and occult cardiac dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):1048–1052. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1591OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Leu RM. Sleep-related breathing disorders and the Chiari 1 malformation. Chest. 2015;148(5):1346–1352. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-3090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Abenza Abildúa MJ, et al. Central apnea-hypopnea syndrome and Chiari malformation type 1: pre and post-surgical studies. Sleep Med. 2021;88:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]