Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to describe the process of adapting an evidence-based patient engagement intervention, enhanced medical rehabilitation (E-MR), for inpatient spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D) rehabilitation using an implementation science framework.

Design:

We applied the collaborative intervention planning framework and included a community advisory board (CAB) in an intervention mapping process.

Setting:

A rehabilitation hospital.

Participants:

Stakeholders from inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation (N=7) serving as a CAB and working with the research team (N=7) to co-adapt E-MR.

Interventions:

E-MR.

Main Outcome Measures:

Logic model and matrices of change used in CAB meetings to identify areas of intervention adaptation.

Results:

The CAB and research team implemented adaptations to E-MR, including (1) identifying factors influencing patient engagement in SCI/D rehabilitation (eg, therapist training); (2) revising intervention materials to meet SCI/D rehabilitation needs (eg, modified personal goals interview and therapy trackers to match SCI needs); (3) incorporating E-MR into the rehabilitation hospital’s operations (eg, research team coordinated with CAB to store therapy trackers in the hospital system); and (4) retaining fidelity to the original intervention while best meeting the needs of SCI/D rehabilitation (eg, maintained core E-MR principles while adapting).

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated that structured processes guided by an implementation science framework can help researchers and clinicians identify adaptation targets and modify the E-MR program for inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.

Keywords: Implementation science, Patient engagement, Patient participation, Rehabilitation, Spinal cord injuries

Each year, 17,500 individuals experience an acute traumatic injury that leads to spinal cord injury/disease (SCI/D), and they complete an average of 35 days of inpatient rehabilitation in the United States.1 SCI/D profoundly affects an individual’s functioning, activity participation, and quality of life.2 Multidisciplinary care teams work with patients to improve functioning, mobility, and self-management through specialized SCI/D rehabilitation programs. However, patients with new SCI/D experience barriers to engagement in rehabilitation, including adjustments to new functional capacities3,4 and organizational factors that discourage patient engagement.5 These barriers may extend inpatient stays and increase health care costs.

Patient-centered care (PCC) is a holistic approach characterized by respectful and individualized empowerment of patients to engage in their care actively.6 Although there is no consensus about its core components, patient engagement (or participation) is a critical cornerstone for PCC.7,8 Researchers have defined patient engagement (or participation) as a deliberate effort and commitment to working toward the goals of rehabilitation therapy, typically demonstrated through active participation and cooperation with treatment providers.9 Earlier research indicated that increased patient engagement (or participation) is associated with increased functional improvement and shorter lengths of stay.10,11

Collaborative goal setting is a treatment activity consistent with PCC principles and a key component of rehabilitation planning. Shared goals between clinicians and patients can drive the clinical decision-making process, improve team-based practice, enhance patient engagement in therapy, and optimize treatment outcomes.12,13 A systematic review indicated that patient involvement in setting rehabilitation goals could improve patient outcomes, including health-related quality of life, emotional health, and self-efficacy.14 Both PCC and collaborative goal setting provide shared goals for clinicians and patients, elevate patients’ self-determination, and encourage active patient engagement in therapy. Last, the International Spinal Cord Society has identified teamwork, shared goal setting, and patient engagement as recommended knowledge and skills for SCI/D medicine.15

Patient engagement (or participation) interventions are systematic and standardized approaches to optimally involving patients in therapy.10 Some patient engagement interventions exist in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation, especially those focusing on goal setting and clinician-patient collaboration. Interventions that encourage active patient participation in their rehabilitation increase patients’ self-determination aligned with PCC rehabilitation.7 Adapting and implementing patient engagement interventions designed for non-SCI/D populations may also benefit patients with SCI/D. Previous studies3,4 identified adapting information for individuals with SCI/D and addressing barriers to engagement as patient-centered practices elevating the quality of SCI/D rehabilitation. Recently, a research team developed a patient engagement intervention, enhanced medical rehabilitation (E-MR), for an older adult rehabilitation population. The trials indicated that engagement-focused rehabilitation interventions might reduce the length of stay, optimize treatment intensity, and enhance the quality of rehabilitation.10,11,16

E-MR is a behavior-based17 patient engagement intervention that trains occupational therapists (OTs) and physical therapists (PTs) to optimize patients’ engagement, motivation, and functional gains in rehabilitation.10,11 Three core principles underlie E-MR: (1) patient as boss; (2) optimize intensity; and (3) link activities to goals. Researchers developed standard E-MR materials to increase patient engagement and clinician adherence to core principles.10 E-MR consists of training manual and standardized materials that PTs and OTs learn to use in a clinical training program.18 Therapists receiving E-MR training empower patients to direct their rehabilitation by (1) selecting personalized goals with their therapist; (2) linking therapeutic activities to personalized goals; and (3) maximizing engagement and effort to pursue personalized goals.

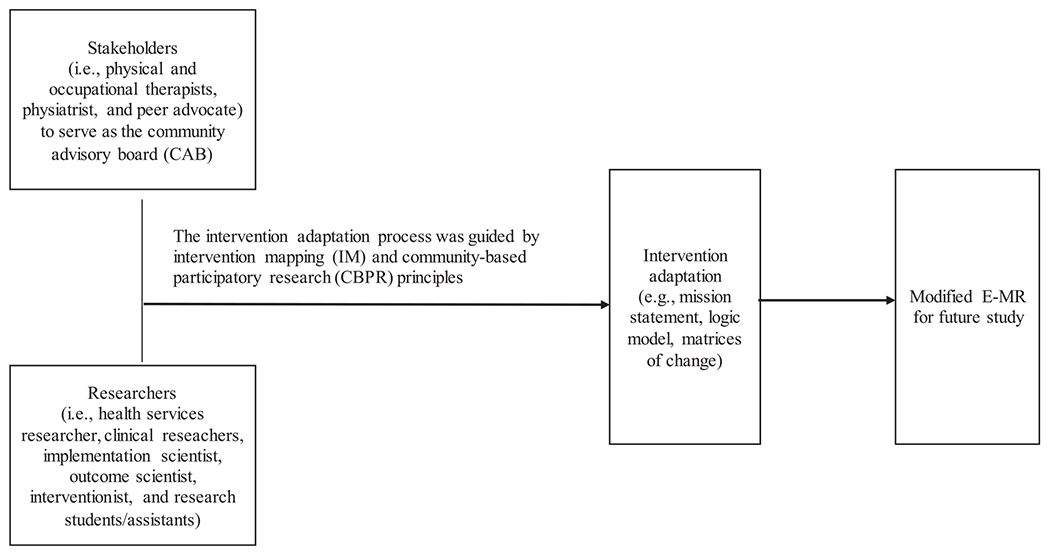

Adapting existing interventions for new settings, practitioners, and patients is a pragmatic approach to optimizing quality in value-based care.19 Dissemination and implementation (D&I) frameworks offer rigorous strategies to adapt evidence-based interventions for new contexts or populations.13 One D&I framework for intervention adaptation is the collaborative intervention planning framework (CIPF).20,21 The CIPF combines intervention mapping (IM) and community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles to engage stakeholders (eg, clinicians, researchers, and patients) in a community advisory board (CAB) to adapt an intervention. IM is a step-by-step systematic framework for intervention planning, implementation, and evaluation.22 CBPR equitably involves researchers, community members, and other stakeholders in the research process to improve practices, change organizations, and reduce health costs.23 Our CAB and research team collaboration followed some CBPR principles: (1) involving stakeholders and researchers in all stages; (2) co-learning among stakeholders; (3) valuing multiple knowledge sources to inform intervention adaptations; (4) employing strengths-based ecological perspectives to activities; and (5) building stakeholders’ capacity to use the adapted intervention.21,24

Because researchers originally developed E-MR in an older population, some content was likely irrelevant to patients with SCI/D who have different demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and needs. After applying the CIPF, E-MR may enhance the engagement of patients with SCI/D in therapy. Thus, we conducted this study to modify E-MR before formally implementing and testing it. This study aimed to describe the process of adapting E-MR for inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.

Methods

Project planning

The hospital, Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, aims to promote PCC and encourage active patient and family engagement to optimize long-term outcomes.25 To support this hospital aim, the lead investigator worked with the SCI/D practice leader over 3-4 grant preparation meetings to conceptualize and plan the project. We planned to form a CAB of inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation stakeholders to obtain expert guidance in adapting E-MR for the cultural context of the hospital.26 The CAB’s purpose was to assess and modify the E-MR program customized for patients in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. Our overall goals were to generate pragmatic adaptations to the original E-MR program and identify potential factors that would influence intervention success in the setting. The research team would customize the E-MR based on the feedback obtained from subsequent CAB meetings (described in later sections).

Participants—Research team and CAB

The research team consisted of a health services researcher, 2 clinical researchers, an implementation scientist, 2 experts in outcomes research and pragmatic clinical trials, and 3 research assistants/graduate students. Two research team members participated in the recent E-MR study in an older population,10 1 serving as the E-MR trainer and another as the PI. Three OTs, 2 PTs, and 1 physiatrist working in the SCI program at the hospital engaged in the CAB. Each had at least 2 years of experience working in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation and had expertise in the organization’s activities, OT and PT services, and knowledge of SCI/D. Last, the CAB included 1 patient advocate who lived with SCI/D. He was employed at the hospital and had SCI/D rehabilitation research experience. All CAB members provided informed consent to participate.

Setting, procedures, and measures

We conducted this study in a hospital providing postacute inpatient, outpatient, and day rehabilitation services in the Midwestern United States. The hospital has employed more than 3000 medical professionals, research staff, and support personnel. The SCI/D center in the hospital admits around 350 patients with SCI/D each year.

We followed the IM approach20–22 to engage the CAB in a structured adaptation process. IM enables clinicians and researchers to review intervention and prioritize targets of change in a step-by-step fashion.22,27 These steps included (1) setting the stage and conducting a needs assessment; (2) introducing E-MR and developing a logic model; and (3) appraising E-MR and developing an implementation plan. Figure 1 presents the collaborative framework for this study. Based on earlier CIPF studies20,21 and the project’s budget consideration, we organized 5 CAB meetings to complete these steps. Each meeting lasted 1.5 hours and included a meeting agenda developed by the research team with input from CAB members. All members of the research team and CAB met monthly for 5 months to generate E-MR adaptation. Research assistants summarized the discussion and recorded it in minutes for each meeting. After each meeting, the research team synthesized discussions and materials and shared meeting summaries with CAB members for approval and feedback before the next meeting. Throughout these meetings, the research team and CAB generated products, such as a mission statement, logic model, and matrices of change. Table 1 summarizes the planning steps and expected intervention adaptation products. The institutional review board of the university and hospital approved the study. CAB members received a $50 honorarium for each meeting that they attended.

Fig 1.

Steps for intervention mapping following the collaborative intervention planning framework.

Table 1.

Meeting structure and intervention mapping process

| Step | Meeting | Goal | Intervention Mapping Objective18 | Major Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Setting the Stage and Needs Assessment | Complete icebreakers; identify engagement needs and factors affecting engagement; generate mission statement | Determine organizational capacity for the SCI/D population and intervention; select performance objectives | Mission statement |

| 2 | E-MR Overview and Logic Model Development | Deep dive into E-MR; develop an intervention logic model | Identify determinants and evidence underlying the development of E-MR; prioritize changes to E-MR determinants and components; share perspectives regarding the research team and CAB’s needs | Intervention adaptation logic model |

| 3 | E-MR Appraisal and Implementation Plan | Review and appraise E-MR materials | Assess feasibility and practicality of original E-MR methods and strategies for SCI/D rehabilitation; prioritize changes to E-MR materials | Draft of matrices of change |

| E-MR Appraisal and Implementation Plan | Discuss changes to the E-MR program; overview of training and implementation logistics | Compare modified and original E-MR; discuss factors influencing E-MR implementation in a new site | Final matrices of change; draft of adapted E-MR | |

| E-MR Appraisal and Implementation Plan | Share and approve finalized E-MR materials; discuss implementation concerns | Foster agreement about final E-MR materials; address implementation barriers | Finalized adapted E-MR; Implementation plan |

The D&I literature has suggested documenting all aspects of adaptation to understand the process better.28 Thus, we describe specific goals and tasks for each IM step below. We document adaptation processes/actions and essential findings/products in the results section.

Step 1: Setting the stage and needs assessment

Our goals were to (1) foster partnership and collaboration; (2) introduce project aims and adaption processes; and (3) identify factors affecting patient engagement at the hospital. We first conducted icebreaker activities to familiarize the research team and CAB with each other, discuss roles, and learn about the project and adaptation process. Then, we conducted a needs assessment to identify the hospital’s need to improve patient engagement and finalized a mission statement. We allocated the first meeting to complete these tasks.

Step 2: E-MR introduction and logic model development

Our goals were to (1) disseminate E-MR-related information to the CAB; and (2) identify areas of intervention adaptation. We first conducted an information-sharing presentation in which we exchanged perspectives about research evidence, clinical experiences, and common challenges while working with patients with SCI/D. We then developed an E-MR adaptation logic model. The logic model facilitated analysis and modification of E-MR to make the intervention fit better the inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.21 We allocated the second meeting to complete these tasks.

Step 3: E-MR appraisal and implementation plan

Our goals were to (1) appraise E-MR components; (2) develop matrices of changes for E-MR component adaptations; and (3) finalize the adapted E-MR program. We first reviewed E-MR materials and drafted matrices of change to prioritize adaption. The matrices of change depicted each component of E-MR in a diagram to understand key concerns about E-MR. The team customized specific aspects of the delivery and content without diluting the core E-MR components.21 We then discussed recommended changes to E-MR and finalized the matrices of changes. Last, we finalized the adapted E-MR program by incorporating all recommendations. We allocated 3 meetings to complete these tasks.

Results

This section delineates intervention adaptation processes/actions and findings/products.

Step 1. Setting the stage and needs assessment

In the first meeting, the research team and CAB members shared their professional backgrounds and SCI/D experiences. Then, the research team briefly introduced the project to CAB members. The research team and CAB members discussed proposed goals, expectations, roles, and activities in the adaptation phase. The research team conducted the needs assessment by examining the hospital’s needs and practices to optimize engagement of patients with SCI/D with CAB members. The needs assessment identified several factors influencing engagement of patients with SCI/D: at the patient level, psychological adjustments to new disability and capacity to engage in therapy influenced engagement; at the clinician level, improving therapists’ abilities to effectively coach patients and balance many clinical demands influenced patient engagement; and at the contextual level, payment, hospital resources, and interaction with family members influenced patient engagement.

The research team drafted the mission statement and shared it with CAB members during the first meeting. To foster a shared vision between the research team and CAB, all members reviewed the mission statement, revised its content, and reached a consensus.29 Supplement 1 (available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/) shows the final mission statement.

Step 2. E-MR introduction and logic model development

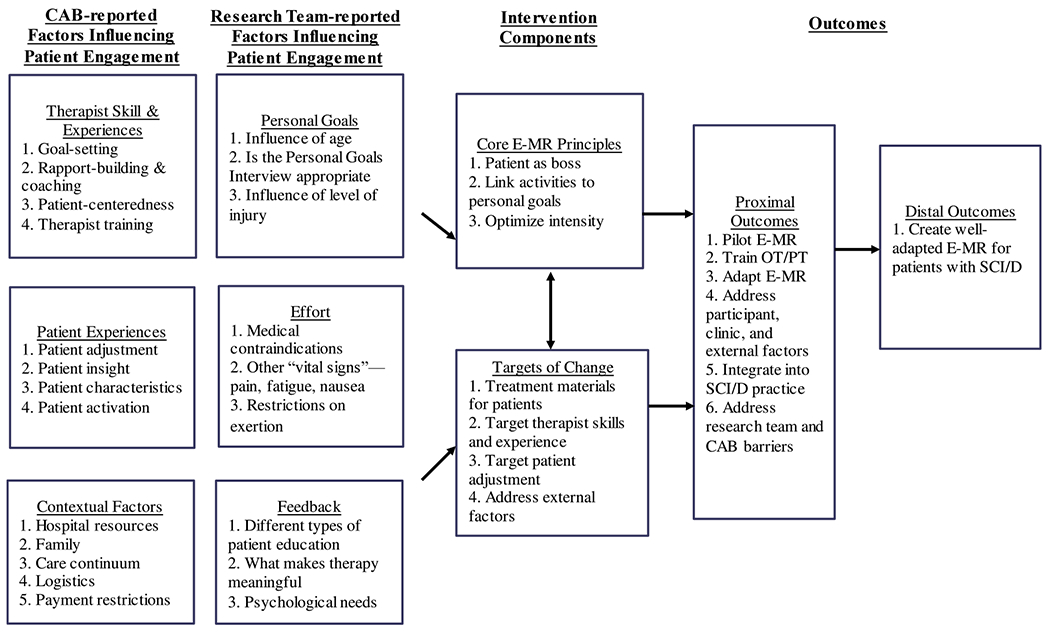

In the second meeting, a research team member who served as a trainer from the most recent E-MR study10 led a group education session to educate the CAB about E-MR’s history, evidence, and development in skilled nursing facilities. After that, the research team asked CAB members to imagine a situation in which the E-MR would be implemented in their setting. The research team gave CAB members index cards to write down and brainstorm factors influencing patient engagement in SCI/D rehabilitation. The research team placed these cards on a dry erase board and discussed how E-MR might address these factors with CAB members. Then, the research team binned and winnowed CAB members’ responses to develop a logic model. Figure 2 summarizes factors influencing patient engagement in SCI/D rehabilitation through (1) therapist skills and experiences; (2) patient experiences; and (3) contextual factors to be addressed in the modification of E-MR.

Fig 2.

Logic model.

Between the second and third meetings, the research team brainstormed potential factors influencing engagement and embedded them into 3 steps of the E-MR process, including goal setting between therapists and patients, effort spent by patients, and feedback provided by therapists to patients. Specifically, the research team identified materials, methods, and training programs in the original E-MR program as modifiable targets of change. To maintain fidelity to the original intervention’s intent while optimizing feasibility in the new context, the research team identified 3 core principles of E-MR (ie, patient as the boss, optimizing intensity, and linking activities to goals) as unmodifiable components. Finally, we connected factors influencing engagement and targets of change to proximal and distal outcomes of the adaptation process. We summarize the findings in a logic model (fig 2).

Step 3. E-MR appraisal and implementation plan

In the third and fourth meetings, the CAB worked with the research team to appraise the 3 major components of E-MR: (1) goal setting; (2) effort; and (3) progress tracking by identifying which components to be revised, deleted, added, or unchanged if the E-MR were to be implemented in SCI/D rehabilitation. Then, we co-developed matrices of change for E-MR adaptation. First, CAB members worked in small groups to complete an appraisal worksheet with research team members. The worksheet enabled CAB members to write down E-MR components (eg, materials, methods, treatment and theoretical principles, or implementation logistics) that they believe should be unchanged, revised, deleted, or added. After working in small groups, the whole CAB and research team met to corroborate information and prioritize key findings. The CAB prioritized adapting E-MR materials, including (1) the personal goals interview for goal setting; (2) the effort card and patient active time measure for effort reporting; and (3) the therapy tracker for feedback and progress tracking as the modifiable targets of change in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation (Table 2). In this context, the research team organized the matrices of change as a framework to group the CAB’s targets of change (ie, therapist skills and experiences, patient experiences, and contextual factors) into categories of goal setting, effort, and feedback. We summarize these findings in the matrices of change (Table 3), containing the intervention modifications discussed in the third and fourth meetings.

Table 2.

Overview of key E-MR components addressed in the study11

| Component | Description | Guidelines | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal goals interview | Card sort of pictures of common activities individuals enjoy | The therapist instructs the patient in sorting cards into activities most and least important to them | Determine individualized goals to personalize therapy and increase patient motivation |

| Active time | An observer-rated amount of time the patient is active in the therapy | Throughout treatment sessions, the patient maintains >65% of therapy time as active time in therapy | Ensure that patients are active in therapy to optimize engagement and effort |

| Progress tracker | Individualized patient brochure of goals, therapeutic activities, and progress | The therapist records patient priority goals and therapeutic activities needed to reach those goals with each patient; patient-friendly progress charts are developed by the therapist on the therapy tracker; the therapy tracker is shown to the patient before and after therapy activities | Visually depict how each activity performed in a therapy session relates to a patient’s goal. |

NOTE. Adapted from Lenze et al.10 See Supplement 2 for an example of personal goals interview, Supplement 3 for an example of redefining “active time” to “engaged time,” and Supplement 4 for an example of a progress tracker.

Table 3.

Matrices of change with examples of E-MR changes

| E-MR Component | Issues | Materials to Review | Final Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Goals Interview—Activity Card Sort | The original card activities can be condensed into broader domains of goals. The card activities should be more fitting for patients with SCI/D. | Draft of card sort; table of goal categories | We condensed the activities into 8 categories (see supplementary 2 for an example). Each category depicts 5-10 specific activities. We added and modified some cards with new activities to fit patients with SCI/D. |

| Effort—Active Time | Patient “active time” may need to be redefined for the SCI/D population. | The definition of “active time” with examples used in the original E-MR. | We redefined “active time” as “engaged time” to encompass skilled activities, such as education, setup, and stretching. |

| Feedback and Progress—Progress Tracker | The paper version of the therapy trackers may be misplaced. Therapeutic activities in the original tracker do not match with activities in inpatient SCI/D settings. | A list of therapeutic activities used in the original E-MR tracker. | Research team coordinated with the CAB to store progress trackers electronically. We modified and added new activities to accommodate more therapeutic activities for patients with SCI/D, and we divided the trackers for PT and OT separately. |

Between the fourth and fifth meetings, the research team synthesized all targets of change to modify the E-MR program. First, prior E-MR trials utilized the Activity Card Sort,30 a card-based assessment containing various activities designed for older adults, to identify activities patients like to do as personal goals. We changed the cards for helping patients identify personal goals to increase face validity. For example, we changed images and activities to increase relevance to the SCI/D population, and we recategorized activities into new activity domains. Second, we modified the therapy trackers to include therapeutic activities relevant to inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. We also developed 2 separate therapy trackers for OT and PT sessions. CAB members indicated some therapeutic activities as essential but not fun for patients. Our trackers included these “not-fun” activities (eg, stretching), but E-MR-trained therapists would link those activities to patient-selected goals to increase patient engagement. Third, we changed “patient active time” to “patient engaged time” on the effort card to evaluate patient engagement. Patient active time in the original E-MR program was defined as when the patient is actively and physically engaged in a therapeutic activity. However, inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation entailed types of education and discharge planning in which patients are cognitively but not physically active. Thus, we changed the term to patient engaged time to assess engagement level during therapy sessions.

In the fifth meeting, the research team incorporated all recommendations generated in earlier steps to develop an implementation plan for E-MR adaptation. It summarized (1) details of adapted intervention components; (2) rationales for adaptation; and (3) descriptions of the adaptation. The research team shared the updated materials with the CAB for final review and approval. We also made notes of potential implementation concerns to plan for the next phase of a randomized controlled trial of the adapted E-MR program. For example, the research team coordinated with the CAB to store therapy trackers electronically in the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab before starting the trial. Supplements 2–5 (available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/) show examples of final products made to customize the E-MR program for inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.

Discussion

Wedescribed applying an implementation science framework to engage researchers, clinicians, and the SCI/D peer advocate in adapting an existing patient engagement intervention, E-MR, for inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. Common D&I frameworks, such as the Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance framework,31 the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Interventions,28,32 the Behaviour Change Wheel,33 and the CIPF20,21 have been used for the intervention development or modification to improve its uptake into health care settings. We used the CIPF to inform our research approach to adapt E-MR and improve PCC in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. The CIPF has involved multiple stakeholders in the adaptation process to understand the unique needs of the new population and context and identified intervention adaptation targets. The CIPF has incorporated IM to engage stakeholders in intervention adaption.20,21 IM provides a step-by-step group process to systematically analyze each intervention component and its fit with the new patient population, provider, and setting. This approach resolves the common problem seen in other D&I frameworks in which stakeholders are involved in the adaptation procedures are unspecified, making it difficult for others to replicate.21 Additionally, the CIPF incorporates CBPR principles emphasizing researcher and stakeholder involvement in all phases of the process and building stakeholders’ capacities to use the adapted intervention. These principles are critical to advancing the intervention’s acceptability, adoption, and sustainable implementation after adaptation.

Even though the CIPF has offered several advantages for intervention adaptation, some but not all components of the original E-MR could be adapted for inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. We identified that unmodifiable components are core principles of E-MR—(1) patient as boss; (2) optimize intensity; and (3) link activities to goals—as relevant to SCI/D rehabilitation. Thus, we did not modify these principles to retain the fidelity to the original intervention.27 Conversely, we identified several E-MR materials requiring modification to meet inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation’s unique needs. First, we adapted the goal-setting cards by adding new activities that younger age groups usually perform to facilitate collaborative patient-therapist goal setting. Second, we adapted assessments of patient effort and engagement during therapy sessions by modifying the standardized effort card and changing the operational definition of patient active time. Third, we adapted progress tracking and feedback by adding therapeutic activities suited for inpatient SCI/D settings to the therapy trackers. However, we did not include the home photograph guide from the original E-MR because it requires caregivers to compile and attach photographs of patients’ homes. Implementing this E-MR component is difficult for caregivers as the original study showed low completion rates.10 Future research may examine pragmatic strategies to engage caregivers or family members in therapy sessions to maximize patient engagement and rehabilitation outcomes.34

This study has used the CIPF to promote researcher-stakeholder collaboration to optimize the fit of an intervention in a new setting. The CIPF emphasizes research partnership in which both the research team and other stakeholders actively engage in each part of the research process. This collaborative approach shares similarities to integrated knowledge guiding principles for SCI/D research in terms of a commitment to partnering with researcher users, such as persons with SCI/D, service providers, other researchers, policymakers, professional organizations, funders, and industry partners, in the research process and the co-creation of knowledge.35 For example, our study has conducted ice breaker activities and dialogs, promoting open and honest communication of all partners and fostering the development of partner relationships based on trust, respect, dignity, and transparency. Also, the research team and CAB co-developed the intervention logic model and matrices of change, fostering shared decision making and respecting all partners’ practical considerations and constraints.

Stakeholder engagement and fidelity to the E-MR succeeded in engaging a research team and stakeholders in collaboration to optimize the fit of an intervention in a new setting. Through collaboration, we identified needed changes and modified the intervention to increase the fit of E-MR with the inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation setting. Also, the CBPR principles and IM procedures embedded in the CIPF enabled researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates to co-address knowledge and practice gaps, thereby facilitating reflection about existing barriers and potential resources to adapt the intervention for the local setting.27 By collaborating with CAB members to assess factors influencing E-MR implementation in their organization, we increase the probability that the intervention will be acceptable, feasible, and efficacious to its end users: clinicians and patients. Researchers may utilize the CIPF as a blueprint to adapt other interventions. This study highlights the application of CIPF to customize the delivery and content of an intervention systematically. This strategy enables stakeholders to meet clinical and organizational needs in a changing health care landscape that prioritizes value-based care and quality.19,36

Limitations and recommendations

Our study had several limitations. This study was descriptive and explored neither association nor causation between the adapted E-MR and patient outcomes. Future steps could include testing this adapted E-MR to examine its feasibility and initial effects. Due to budget constraints, this study only conducted 5 1.5-hour CAB sessions and had 7 SCI/D rehabilitation stakeholders in our CAB. CAB members might not have insufficient time to evaluate all intervention components. Researchers interested in applying the CIPF may seek funders to ensure adequate study resources. Also, only 1 SCI/D patient advocate with a high level of function and extensive research experience at the hospital joined the adaptation process. Future studies may benefit from including patients with SCI/D with varying levels of functioning and professional knowledge and their families and caregivers. As experts on the effect of their own disabilities on their lives, patients offer perspectives that enhance the development of interventions.36,37 Although patient engagement is an essential concept in PCC, the adapted E-MR program focused on OT and PT inpatient services. Other providers, patients, funders, and policymakers may benefit from patient engagement interventions.27 Future research may adopt an interprofessional approach to identify patients’ needs and test whether E-MR could apply to other disciplines, such as psychology, counseling, social work, speech therapy, and nursing, to achieve a comprehensive view of interprofessional rehabilitation. Funders, policymakers, and industry partners offer valued perspectives. Our next step is to conduct a randomized controlled trial to explore the feasibility of the adapted E-MR.

Conclusion

Inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation faces barriers to patient engagement. We used stakeholder collaboration and modified intervention mapping to adapt E-MR to inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation. Our findings highlight the potential success of using CIPF to modify the E-MR as a patient engagement intervention implemented in inpatient SCI/D rehabilitation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the funding agencies. We certify that all financial and material support for this research and work is clearly identified in the article. We acknowledge Megen Devine at Washington University for her editorial assistance with this article. We also thank the researchers, clinicians, and administrative staff at Washington University in St. Louis and Shirley Ryan AbilityLab for their assistance with this study.

This work was supported by the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (542448). The National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (K01HD095388) and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, & Rehabilitation Research (90SIMS0015) supported a portion of Dr Wong’s effort for the write-up and science development.

Disclosures:

Dr Lenze reported research support (loaned equipment for research) from MagStim, grant support from the Mercatus Center Emergent Ventures, and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, outside the submitted work. He has served as a consultant for the Prodeo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Boehringer Ingelheim. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

List of abbreviations:

- CAB

community advisory board

- CBPR

community-based participatory research

- CIPF

collaborative intervention planning framework

- D&I

dissemination and implementation

- E-MR

enhanced medical rehabilitation

- OT

occupational therapist

- PCC

patient-centered care

- PT

physical therapist

- SCI/D

spinal cord injury/disease

- IM

intervention mapping

Footnotes

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. Birmingham: University of Alabama at Birmingham; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu H, Shewchuk RM, Chen YY, Richards JS. Evaluating the quality of acute rehabilitation care for patients with spinal cord injury: an extended Donabedian model. Qual Manag Health Care 2010;19:47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg J, Kreuter M, Taft C, Person LO. Patient participation in care and rehabilitation from the perspective of patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013;51:834–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melin J, Persson LO, Taft C, Kreuter M. Patient participation from the perspective of staff members working in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2018;56:614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wade D Rehabilitation—a new approach. Part four: a new paradigm, and its implications. Clin Rehabil 2016;30:109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinemann AW, LaVela SL, Etingen B, et al. Perceptions of person-centered care following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bright FA, Kayes NM, Worrall L, McPherson KM. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:643–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lequerica AH, Donnell CS, Tate DG. Patient engagement in rehabilitation therapy: physical and occupational therapist impressions. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenze EJ, Lenard E, Bland M, et al. Effect of enhanced medical rehabilitation on functional recovery in older adults receiving skilled nursing care after acute rehabilitation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e198199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenze EJ, Host HH, Hildebrand MW, et al. Enhanced medical rehabilitation increases therapy intensity and engagement and improves functional outcomes in postacute rehabilitation of older adults: a randomized-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:708–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown M, Levack W, McPherson KM, et al. Survival, momentum, and things that make me “me”: patients’ perceptions of goal setting after stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1020–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levack W, Tomori K, Takahashi K, Sherrington AJ. Development of an English-language version of a Japanese iPad application to facilitate collaborative goal setting in rehabilitation: a Delphi study and field test. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levack WM, Weatherall M, Hay-Smith EJ, Dean SG, McPherson K, Siegert RJ. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(7):CD009727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thumbikat P, Marshall R, Moslavac S. Recommended knowledge and skills framework for spinal cord medicine. Available at: https://www.iscos.org.uk/recommended-knowledge-and-skills-framework-for-spinal-cord-medicine. Accessed January 21, 2022.

- 16.Host HH, Lang CE, Hildebrand MW, et al. Patient active time during therapy sessions in postacute rehabilitation: development and validation of a new measure. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 2014;32:169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bland MD, Birkenmeier RL, Barco P, Lenard E, Lang CE, Lenze EJ. Enhanced medical rehabilitation: effectiveness of a clinical training model. NeuroRehabilitation 2016;39:481–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juckett LA, Robinson ML, Wengerd LR. Narrowing the gap: an implementation science research agenda for the occupational therapy profession. Am J Occup Ther 2019;73. 7305347010p1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabassa LJ, Druss B, Wang Y, Lewis-Fernández R. Collaborative planning approach to inform the implementation of a healthcare manager intervention for Hispanics with serious mental illness: a study protocol. Implement Sci 2011;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, et al. Using the collaborative intervention planning framework to adapt a health-care manager intervention to a new population and provider group to improve the health of people with serious mental illness. Implement Sci 2014;9:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory- and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav 1998;25:545–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J. The Leap Advisory Board, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol 2018;73:884–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. Inpatient care. Available at: https://www.sralab.org/services/inpatient-care. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- 26.Dévieux JG, Malow RM, Rosenberg R, et al. Cultural adaptation in translational research: field experiences. J Urban Health 2005;82 (Suppl 3). iii82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones TM, Dear BF, Hush JM, Titov N, Dean CM. Application of intervention mapping to the development of a complex physical therapist intervention. Phys Ther 2016;96:1994–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2019;14:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zoellner J, Hill JL, Brock D, et al. One-year mixed-methods case study of a community-academic advisory board addressing childhood obesity. Health Promot Pract 2017;18:833–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum CA, Edwards D. Activity Card Sort: test manual. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2013;8:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster AM, Armstrong J, Buckley A, et al. Encouraging family engagement in the rehabilitation process: a rehabilitation provider’s development of support strategies for family members of people with traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:1855–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gainforth HL, Hoekstra F, McKay R, et al. Integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for conducting and disseminating spinal cord injury research in partnership. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102:656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haywood C, Martinez G, Pyatak EA, Carandang K. Engaging patient stakeholders in planning, implementing, and disseminating occupational therapy research. Am J Occup Ther 2019;73:7301090010p1-p9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chudyk AM, Waldman C, Horrill T, et al. Models and frameworks of patient engagement in health services research: a scoping review protocol. Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.