Abstract

We report the synthesis of a degradable polyphosphoramidate via ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) with the Grubbs initiator (IMesH2)(C5H5N)2(Cl)2Ru═CHPh. Controlled ROMP of a low ring strain diazaphosphepine-based cyclic olefin was achieved at low temperatures to afford well-defined polymers that readily undergo degradation in acidic conditions via the cleavage of the acid-labile phosphoramidate linkages. The diazaphosphepine monomer was compatible in random and block copolymerizations with phenyl and oligo(ethylene glycol) bearing norbornenes. This approach introduced partial or complete degradability into the polymer backbones. With this chemistry, we accessed amphiphilic poly(diazaphosphepine-norbornene) copolymers that could be used to prepare micellar nanoparticles.

Graphical Abstract

Degradable polymers are attractive in a host of applications, including drug delivery, tissue engineering, and fabricating electronic devices and recyclable materials.1–6 Traditionally, ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of cyclic monomers, such as cyclic ketene acetals, lactides, and lactones, is harnessed to synthesize well-defined degradable polyesters.7–11 Recently, polymers containing a variety of hydrolytically and redox degradable moieties have been prepared via ruthenium-based metathesis polymerizations, including acyclic diene metathesis (ADMET) polymerization,12,13 cascade enyne metathesis polymerization,14,15,16 and ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP).

ROMP is known as a powerful tool for the synthesis of polymers with predictable molecular weights, narrow molecular weight distributions, and complex architectures.17–22 In particular, the development of well-defined ruthenium carbene initiators has enabled efficient polymerization with excellent functional group tolerance.23–25 Despite the tremendous diversity of functional nondegradable polymers accessed via ROMP,17–25 examples of well-defined high molecular weight polymers consisting of fully degradable backbones remain rare. In 2013, Kiessling and co-workers demonstrated the controlled ROMP of bicyclic oxazinones, resulting in polymers that degrade under both acidic and basic conditions.26 Recently, Johnson and co-workers reported the statistical copolymerization of silyl ether-based cyclic olefins with norbornene-based macromonomers via ROMP to generate backbone degradable bottlebrush and star copolymers.27 Other monomers, including dioxepins,28 cyclic phosphates,29 disulfide containing cyclic olefin,30 levoglucosenol,31 cyclic carbonate,32 and cyclic enol ethers,33 have been reported in the preparation of degradable polymers via ROMP. However, in these cases, some fundamental limitations were observed, including poor control over the polymer molecular weight and dispersity, as well as being limited to producing high molecular weight fragments upon the degradation of copolymers consisting of both degradable and nondegradable monomer units.

In 2012, Kilbinger and co-workers reported the synthesis of a diazaphosphepine-based cyclic olefin, 2-phenoxy-1,3,4,7-tetrahydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphepine 2-oxide (PTDO), which was used as a sacrificial agent for amine end-functionalization of living ROMP polymers.34 The researchers claimed the formation of an unreactive ruthenium carbene post PTDO incorporation. We envisioned that PTDO should be a good candidate for the preparation of fully degradable polymers via ROMP under the appropriate conditions. It is well-known that the release of ring strain of cyclic monomers serves as the main driving force in ROMP, compensating for entropy loss during polymerization.24 However, an evaluation of the ring strain energy of PTDO via a density functional theory calculation revealed a low ring strain of 10.86 kcal/mol (Figure S1). This number is markedly lower than the strain energy of norbornene (27.2 kcal/mol), the most widely used monomer class employed for ROMP.35,36 In the case of low ring strain monomers such as cyclopentene, one approach to achieve high monomer conversion is to lower the reaction temperature.25,37–40 Therefore, we hypothesized that ROMP of PTDO would be achieved at low reaction temperatures to afford polymers with controlled molecular weight and low dispersity. Furthermore, upon hydrolysis, the polymer would degrade into a phosphoric acid and 1,4-diamino-2-butene, which is an unsaturated analog of biogenic amines involved in cell growth and differentiation, leading to a potentially biocompatible material.41

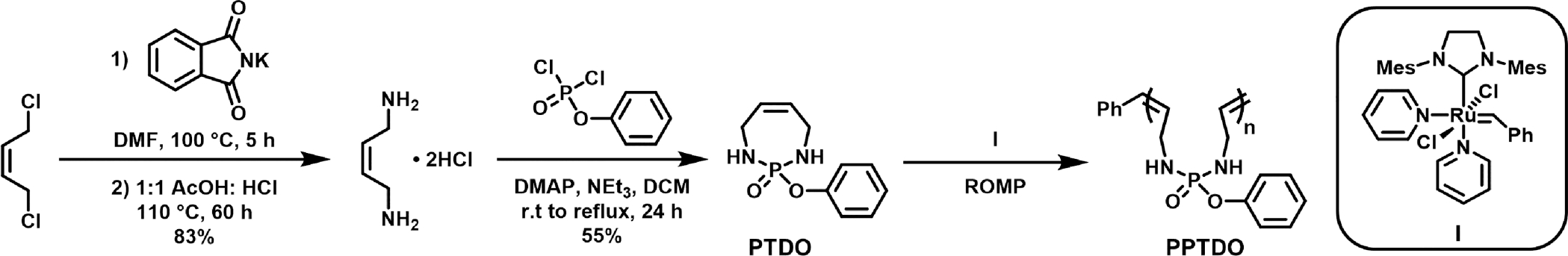

To start the investigation, the seven membered cyclic monomer PTDO was prepared via a two-step synthesis with an overall yield of 44% (Figure 1).34,42 The monomer was then subjected to the Grubbs initiator (IMesH2)-(C5H5N)2(Cl)2Ru═CHPh (I) at different reaction temperatures (Table 1). This initiator was chosen due to its fast initiation rate and high reactivity toward less active olefins.25,43 Initial screening was performed with 0.3 M PTDO (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Despite the nearly 50% monomer conversion at 20 °C, we only observed the formation of oligomers with a broad dispersity of 1.62. A secondary peak at 25.8 min on size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) indicated the presence of side reactions such as adverse backbiting and early termination (Figure S2). By decreasing the reaction temperature to 2 °C, a high molecular weight polymer with narrow dispersity was obtained (Mn = 19.3 kDa, Đ = 1.10). An increase in initial monomer concentration to 0.5 M did not lead to changes in Mn or Đ, but significantly reduced side reactions (Figure S2). As such, ROMP with 0.5 M PTDO at 2 °C proved to be optimal, resulting in 55% PTDO conversion in 5 h (Mn = 14.2 kDa, Đ = 1.16, Table 1, entry 5). Further decreases in reaction temperature led to a reduction in monomer conversion (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). At −20 °C, more than 95% of PTDO was retrieved after quenching the reaction with ethyl vinyl ether (EVE), indicating a failure to initiate.25 Polymerizations with the bromopyridine-modified Grubbs initiator43 (IMesH2)-(C5H4NBr)2(Cl)2Ru═CHPh were also performed, affording a similar trend with respect to the effect of temperature on the polymerization (Table S1 and Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Synthesis and ring-opening metathesis polymerization of 2-phenoxy-1,3,4,7-tetrahydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphepine 2-oxide (PTDO) to afford polymers bearing phosphoramidate linkages.

Table 1.

ROMP of PTDO at Varying Temperaturesa

| entry | T (°C) | [M]0 (M) | conv.b (%) | Mn,theoc (kDa) | Mn,MALSd (kDa) | Đ d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 0.3 | 48 | 10.7 | 5.1 | 1.62 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.3 | 58 | 13.1 | 19.3 | 1.10 |

| 3 | 20 | 0.5 | 42 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 1.26 |

| 4 | 10 | 0.5 | 47 | 10.5 | 14.6 | 1.19 |

| 5 | 2 | 0.5 | 55 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 1.16 |

| 6 | −5 | 0.5 | 44 | 9.9 | 12.6 | 1.16 |

| 7 | −20 | 0.5 | <5 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

ROMP was performed in 10/90 v/v MeOH in DCM under N2 for 5 h and quenched with ethyl vinyl ether. A feed ratio of 100:1 [M]0:[I] was used for all reactions.

Monomer conversion was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Theoretical molecular weight Mn,theo = DPmonomer × MWmonomer where DP = feed ratio × conversion.

Molecular weight and dispersity were determined by size-exclusion chromatography with multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) with a measured dn/dc of 0.1174 mL/g (Figure S4).

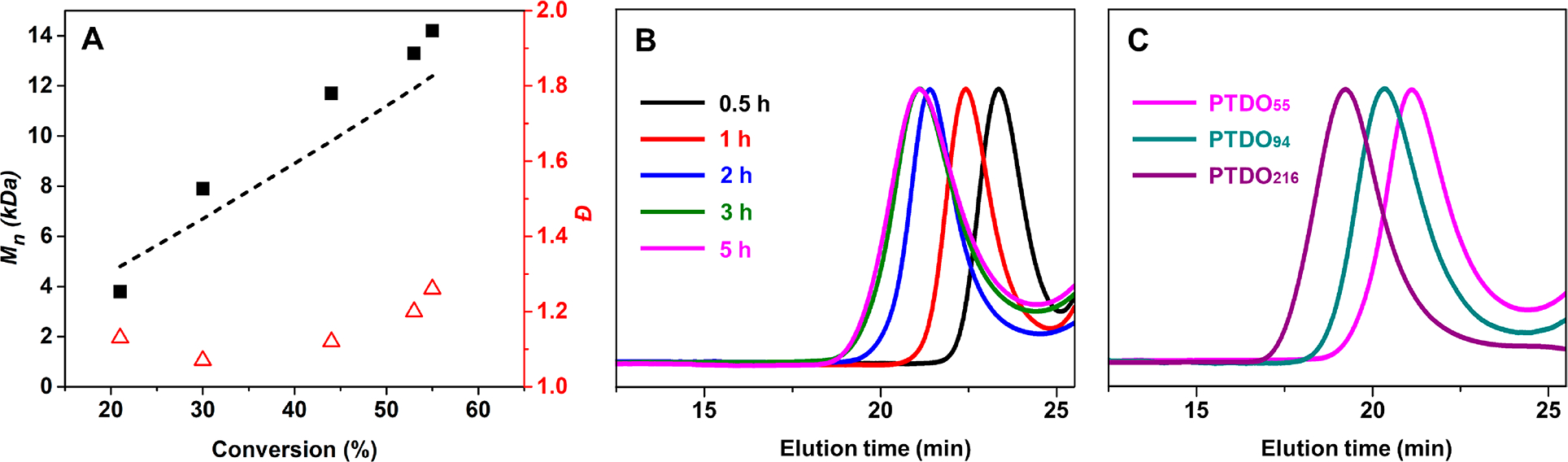

To examine the chain growth nature of PTDO polymerization, parallel reactions were setup and quenched at different times (Figure 2, Table 2, entries 1–5). The polymer molecular weight increased linearly with respect to monomer conversion and maintained a low Đ (1.07–1.26), indicative of good control over the polymerization (Figures 2A and S5–S7). A plot of ln([M]0/[M]t) versus time revealed a linear relationship to 3 h, indicating pseudo first-order kinetics consistent with a controlled polymerization (Figure S6). At 5 h, no significant increase in PTDO conversion and Mn was observed as the reaction reached equilibrium between monomer and polymer (Figure 2B). However, broadening of the SEC peaks was noticed at equilibrium, indicating chain transfer and backbiting events at high monomer conversion. Throughout the polymerizations, both E and Z alkene configurations were observed according to 1H NMR analysis. An E/Z ratio of 5:1 was determined for the backbone olefins based on the integration of olefin signals, suggesting the predominant formation of trans-olefin under the investigated polymerization conditions (Figures S5 and S7). By increasing the [M]0:[I] ratio, a series of PPTDOs with different molecular weights and consistently low Đ were synthesized (Figure 2C, Table 2, entries 5–7). The theoretical molecular weights were in good agreement with the measured Mn from SEC-MALS. These results unequivocally indicate that PTDO undergoes controlled ROMP before reaching equilibrium. Terminating the reaction at early times (3–5 h) enables access to well-defined PPTDO with a predictable molecular weight.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of PPTDOs by ROMP in accordance with Table 2. (A) Plot of Mn and Đ vs monomer conversion, obtained by a combination of SEC-MALS and 1H NMR analysis. The dotted line represents the theoretical Mn. (B) SEC traces (normalized RI) of PPTDOs quenched at different reaction times (correlated to Table 2, entries 1–5). (C) SEC traces (normalized RI) of PPTDOs of different molecular weights (correlated to Table 2, entry 5: PTDO55; entry 6: PTDO94; entry 7: PTDO216).

Table 2.

Kinetics of PTDO Homopolymerization and Synthesis of Different Molecular Weight PPTDOa

| entry | [M]0:[I] | time (h) | conv.b (%) | Mn,theoc (kDa) | Mn,MALSd (kDa) | Đ d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100:1 | 0.5 | 21 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 1.13 |

| 2 | 100:1 | 1 | 30 | 6.7 | 7.9 | 1.07 |

| 3 | 100:1 | 2 | 44 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 1.12 |

| 4 | 100:1 | 3 | 53 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 1.20 |

| 5 | 100:1 | 5 | 55 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 1.26 |

| 6 | 200:1 | 5 | 47 | 21.1 | 19.4 | 1.20 |

| 7 | 400:1 | 5 | 54 | 48.4 | 44.3 | 1.17 |

Polymerization condition: 2 °C under N2.

Conversion was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Theoretical Mn was calculated from monomer conversion.

Molecular weight and dispersity were determined via SEC-MALS.

The thermal properties of PPTDO (DP = 94, E/Z = 7:1) were then investigated. At room temperature, PPTDO appeared as a yellow, brittle solid. The polymer became rubbery when left open to air, possibly due to the plasticizing effect of moisture. Thermogravimetric analysis revealed that the polymer decomposes at 235 °C (Figure S8). By differential scanning calorimetry, only the glass transition temperature of 42 °C was observed, indicating the amorphous and noncrystalline nature of the polymer (Figure S9). In combination, the thermal analyses show PPTDO is thermally stable and should have a long shelf life at room temperature or lower, under anhydrous conditions.

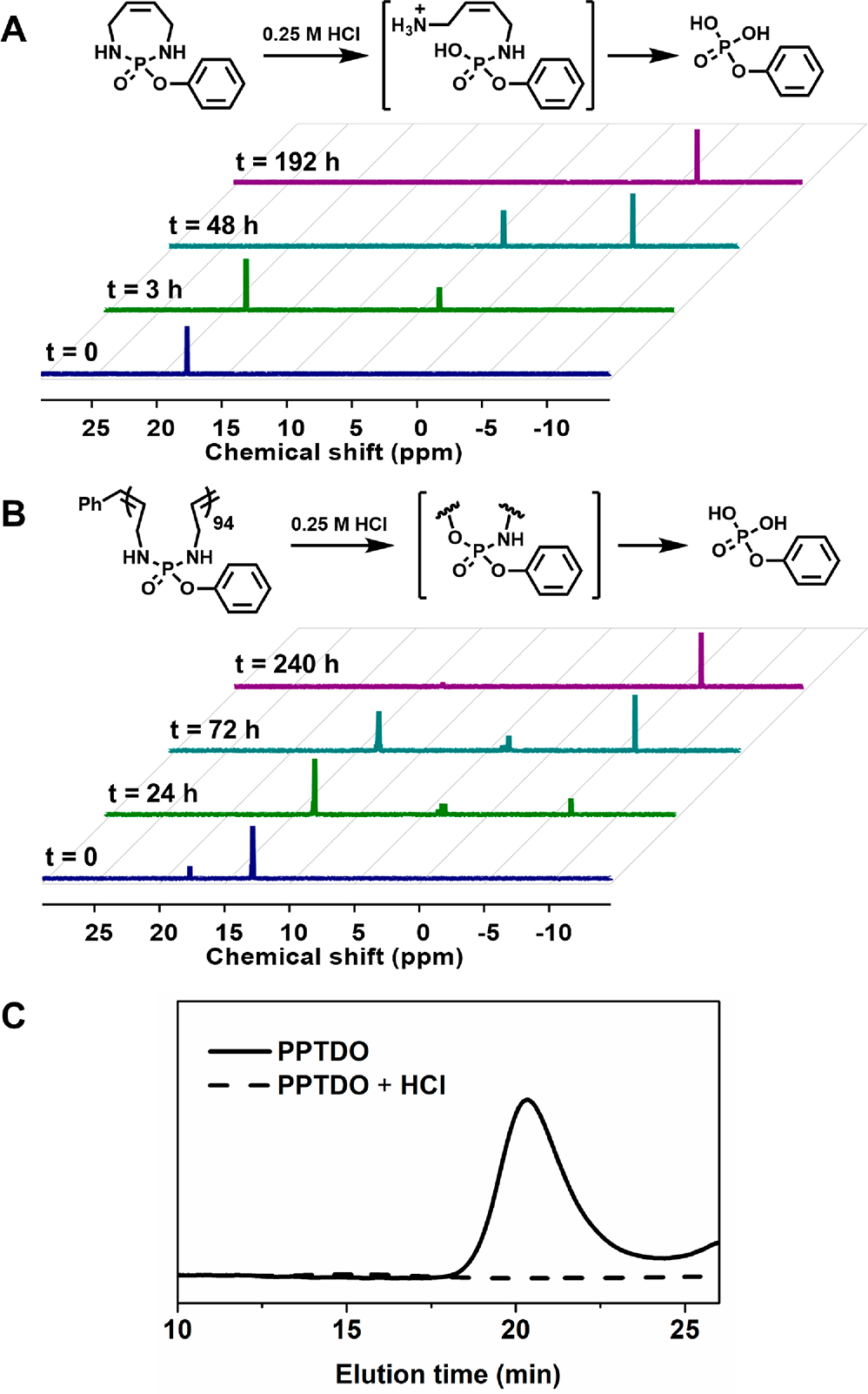

To understand the degradation mechanism of the material, both PTDO and PPTDO were subjected to a mixture of 0.25 M HCl in DMSO-d6. Both 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopies were used to monitor the degradation kinetics (Figures S10–S15). Over 48 h, the PTDO monomer completely degraded, as indicated by the disappearance of the 31P resonance at 18.07 ppm (Figure 3A). The appearance of a peak at 3.20 ppm attributed to be the single phosphoramidate linkage cleavage product. The signal at −6.72 ppm is well aligned with phenylphosphoric acid (δ = −6.23 ppm). The minor difference in chemical shift is caused by the different protonation state. The full PTDO to phenylphosphoric acid conversion was achieved in 192 h. 1H NMR spectroscopy further confirmed the identities of the degraded products as phenylphosphoric acid and 1,4-diamino-2-butene (Figure S13). Notably, the degradation of PPTDO was slower than that of the monomer (Figure S10). At 240 h, more than 80% of the polymer degraded into phenylphosphoric acid as the 31P resonance at 13.00 ppm disappeared and a signal at −6.72 ppm emerged (Figure 3B). The peaks between 2.8 and 3.5 ppm represent the intermediate degraded polymers with different degrees of backbone hydrolysis. Finally, no high molecular weight species were detected by SEC-MALS, further confirming complete backbone degradation (Figure 3C). We expected that by modifying the molar mass of the polymer and solution pH, different backbone degradation rates could be achieved. Motivated by these results, we then moved on to investigate the possibility of using PTDO as a comonomer to introduce degradability into other ROMP derived polymers (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Degradation of PTDO and PPTDO (DP = 94) in 0.25 M HCl in DMSO-d6 at room temperature. 31P NMR spectra of (A) PTDO degradation and (B) PPTDO degradation at different times. (C) SEC traces of PPTDO before and after 240 h acid treatment. Note: 31P NMR spectroscopy of phenylphosphoric acid was measured to give a signal at −6.23 ppm.

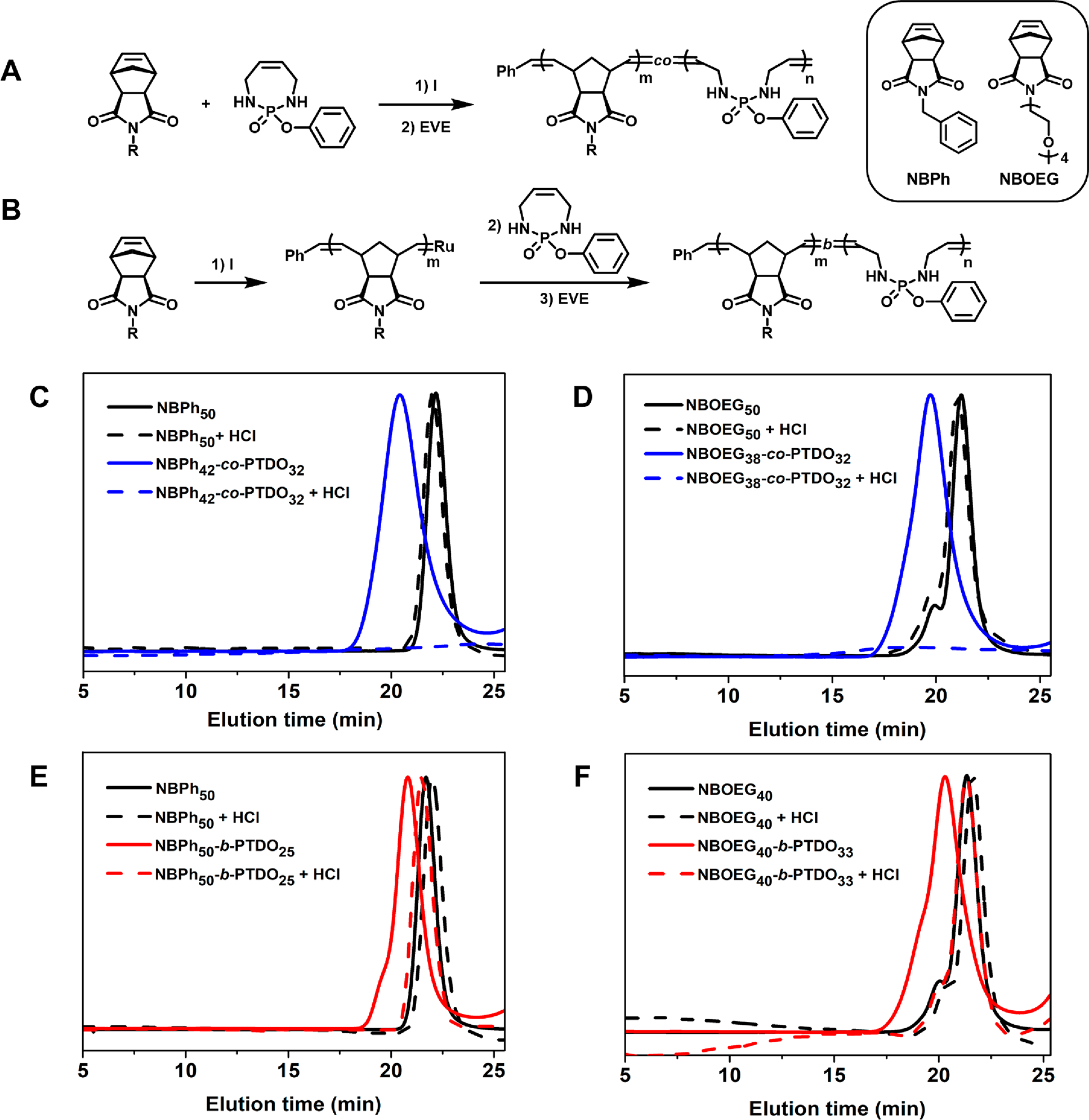

Figure 4.

Synthesis and degradation of NB-PTDO copolymers. Synthetic scheme for the preparation of (A) random copolymers, and (B) block copolymers of NB and PTDO. SEC traces (normalized RI) of random copolymers with (C) NBPh, and (D) NBOEG before and after acid treatment. SEC traces (normalized RI) of block copolymers with (E) NBPh, and (F) NBOEG before and after acid treatment. Degradation condition: 0.5 M HCl in DMSO for 24 h at room temperature.

Random copolymerization of PTDO with norbornenes bearing phenyl and oligo(ethylene glycol) (NBPh and NBOEG) were performed (Figure 4A). A 1:1 ratio of PTDO: NB was dissolved in a mixture of MeOH/DCM and cooled to 2 °C before the addition of 0.02 equiv. of I. The reaction was quenched after 5 h with EVE. 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed an 84% conversion of NBPh and a 64% conversion of PTDO, yielding the polymer NBPh42-co-PTDO32 with Đ of 1.13 (Figure S16). Similarly, NBOEG copolymerized with PTDO to give the polymer NBOEG38-co-PTDO32 with Đ of 1.13 (Figure S17). In both cases, PTDO conversion (~64%) was higher than that for PTDO homopolymerization (vide supra), possibly because of a more active chain end post norbornene incorporation. Both copolymers and their corresponding norbornene homopolymers were analyzed by SEC-MALS before and after 0.5 M HCl treatment (Figure 4C,D). In both cases, the copolymers completely degraded into small molecules, indicating a statistical incorporation of PTDO. The norbornene homopolymers remained unchanged post acid treatment. Next, two block copolymers of PTDO and norbornene were synthesized (Figure 4B). Norbornene was first polymerized with I at room temperature to yield the first block. Then the reaction mixture was cooled to 2 °C, followed by PTDO addition for chain extension. 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed a PTDO conversion between 40~50% (Figures S18–S19). After treating the block copolymers NBPh50-b-PTDO25 and NBOEG40-b-PTDO33 with acid, SEC traces shifted toward longer retention times overlapping with signals from the polynorbornene controls (Figure 4E,F). These results show that, by controlling the PTDO feed ratio and position in the backbone, we can achieve controlled degradation, either partial or complete, of ROMP-derived polymers.

A potential application of PTDO containing amphiphilic copolymers is to produce biodegradable nanoparticles for biomedical applications, such as drug delivery. Both the block and random copolymers NBOEG40-b-PTDO33 and NBOEG38-co-PTDO32 self-assembled into spherical nanoparticles in aqueous solution, as evidenced by dry state transmission electron microscopy.44 The nanoparticles assembled from the block copolymer NBOEG40-b-PTDO33 were uniform in size with a diameter of 24 ± 4 nm, whereas two separate populations were observed in NBOEG38-co-PTDO32 based nanoparticles: 55 ± 8 nm and 133 ± 27 nm (Figure S20A,B). Cytotoxicity of the NBOEG-PTDO nanoparticles against human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells was evaluated by a CellTiter-Blue assay. No appreciable cytotoxicity was observed even at a high concentration of nanoparticles at 150 μg/mL, highlighting the potential of these nanoparticles as nontoxic nanocarriers (Figure S20C).

In summary, we demonstrate an approach to generate degradable polymers featuring phosphoramidate linkages in their backbones. ROMP of the low strain diazaphosphepine based monomer, PTDO, at low temperatures proceeded in a controlled manner, affording high molecular weight polyphosphoramidates that undergo complete backbone degradation upon acid treatment. We also showed that the PTDO monomer copolymerized efficiently with norbornenes, introducing partial or complete degradability into those polymer backbones. Furthermore, the amphiphilic copolymers of PTDO and oligo(ethylene glycol) bearing norbornene self-assembled into micellar nanoparticles and showed no discernible cell cytotoxicity. Moving forward, we expect a plurality of cyclic diazaphosphepine based monomers can be generated via ring-closing metathesis and subsequently polymerized via ROMP.45 Future studies, including the synthesis and polymerization of functionalized phosphoramidates, modifying the degradation rates of polymers and nanoparticles, as well as applications in drug delivery and recyclable materials are underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

N.C.G. acknowledges support of this research from the NIH through the NHLBI (R01HL139001). Additional support was provided by the IMSERC at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-1542205), the State of Illinois, and the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00401.

Experimental details and additional analytical results (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00401

Contributor Information

Yifei Liang, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Simpson-Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, Lurie Cancer Center, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Hao Sun, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Simpson-Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, Lurie Cancer Center and Departments of Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Pharmacology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Wei Cao, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Simpson-Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, Lurie Cancer Center and Departments of Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Pharmacology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States.

Matthew P. Thompson, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Simpson-Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, Lurie Cancer Center and Departments of Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Pharmacology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States

Nathan C. Gianneschi, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Simpson-Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, Lurie Cancer Center and Departments of Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science and Engineering, and Pharmacology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Delplace V; Nicolas J Degradable vinyl polymers for biomedical applications. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hillmyer MA; Tolman WB Aliphatic Polyester Block Polymers: Renewable, Degradable, and Sustainable. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2390–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Semsarilar M; Perrier S ‘Green’ reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Feig VR; Tran H; Bao ZN Biodegradable Polymeric Materials in Degradable Electronic Devices. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Farah S; Anderson DG; Langer R Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications - A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wilson JA; Luong D; Kleinfehn AP; Sallam S; Wesdemiotis C; Becker ML Magnesium Catalyzed Polymerization of End Functionalized Poly(propylene maleate) and Poly(propylene fumarate) for 3D Printing of Bioactive Scaffolds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Becker G; Wurm FR Functional biodegradable polymers via ring-opening polymerization of monomers without protective groups. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7739–7782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tardy A; Nicolas J; Gigmes D; Lefay C; Guillaneuf Y Radical Ring-Opening Polymerization: Scope, Limitations, and Application to (Bio)Degradable Materials. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 1319–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fu CK; Xu JT; Boyer C Photoacid-mediated ring opening polymerization driven by visible light. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7126–7129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hill MR; Kubo T; Goodrich SL; Figg CA; Sumerlin BS Alternating Radical Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Ketene Acetals: Access to Tunable and Functional Polyester Copolymers. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 5079–5084. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Agarwal S Chemistry, chances and limitations of the radical ring-opening polymerization of cyclic ketene acetals for the synthesis of degradable polyesters. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 953–964. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lv A; Cui Y; Du FS; Li ZC Thermally Degradable Polyesters with Tunable Degradation Temperatures via Postpolymerization Modification and Intramolecular Cyclization. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 8449–8458. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shearouse WC; Lillie LM; Reineke TM; Tolman WB Sustainable Polyesters Derived from Glucose and Castor Oil: Building Block Structure Impacts Properties. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bhaumik A; Peterson GI; Kang C; Choi TL Controlled Living Cascade Polymerization to Make Fully Degradable Sugar-Based Polymers from D-Glucose and D-Galactose. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 12207–12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Fu LB; Sui XL; Crolais AE; Gutekunst WR Modular Approach to Degradable Acetal Polymers Using Cascade Enyne Metathesis Polymerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15726–15730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Gutekunst WR; Hawker CJ A General Approach to Sequence-Controlled Polymers Using Macrocyclic Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8038–8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bielawski CW; Grubbs RH Living ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Grubbs RH; Khosravi E Handbook of Metathesis: Polymer Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Varlas S; Keogh R; Xie YJ; Horswell SL; Foster JC; O’Reilly RK Polymerization-Induced Polymersome Fusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20234–20248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fu LB; Zhang TQ; Fu GY; Gutekunst WR Relay Conjugation of Living Metathesis Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12181–12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tan XY; Lu H; Sun YH; Chen XY; Wang DL; Jia F; Zhang K Expanding the Materials Space of DNA via Organic-Phase Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Chem. 2019, 5, 1584–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lee PW; Isarov SA; Wallat JD; Molugu SK; Shukla S; Sun JEP; Zhang J; Zheng Y; Dougherty ML; Konkolewicz D; Stewart PL; Steinmetz NF; Hore MJA; Pokorski JK Polymer Structure and Conformation Alter the Antigenicity of Virus-like Particle-Polymer Conjugates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3312–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ogba OM; Warner NC; O’Leary DJ; Grubbs RH Recent advances in ruthenium-based olefin metathesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4510–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sutthasupa S; Shiotsuki M; Sanda F Recent advances in ring-opening metathesis polymerization, and application to synthesis of functional materials. Polym. J. 2010, 42, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Song K; Kim K; Hong D; Kim J; Heo CE; Kim HI; Hong SH Highly active ruthenium metathesis catalysts enabling ring-opening metathesis polymerization of cyclopentadiene at low temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fishman JM; Kiessling LL Synthesis of Functionalizable and Degradable Polymers by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5061–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Shieh P; Nguyen HVT; Johnson JA Tailored silyl ether monomers enable backbone-degradable polynorbornene-based linear, bottlebrush and star copolymers through ROMP. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 1124–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Fraser C; Hillmyer MA; Gutierrez E; Grubbs RH Degradable Cyclooctadiene Acetal Copolymers - Versatile Precursors to 1,4-Hydroxytelechelic Polybutadiene and Hydroxytelechelic Polyethylene. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 7256–7261. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Steinbach T; Alexandrino EM; Wurm FR Unsaturated poly(phosphoester)s via ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 3800–3806. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chang CC; Emrick T Functional Polyolefins Containing Disulfide and Phosphoester Groups: Synthesis and Orthogonal Degradation. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Debsharma T; Behrendt FN; Laschewsky A; Schlaad H Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Biomass-Derived Levoglucosenol. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6718–6721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).McGuire TM; Perale C; Castaing R; Kociok-Kohn G; Buchard A Divergent Catalytic Strategies for the Cis/Trans Stereoselective Ring-Opening Polymerization of a Dual Cyclic Carbonate/Olefin Monomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 13301–13305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Feist JD; Xia Y Enol Ethers Are Effective Monomers for Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization: Synthesis of Degradable and Depolymerizable Poly(2,3-dihydrofuran). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1186–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nagarkar AA; Crochet A; Fromm KM; Kilbinger AFM. Efficient Amine End-Functionalization of Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymers. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4447–4453. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Schleyer PV; Williams JE; Blanchard KR Evaluation of Strain in Hydrocarbons - Strain in Adamantane and Its Origin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hlil AR; Balogh J; Moncho S; Su HL; Tuba R; Brothers EN; Al-Hashimi M; Bazzi HS Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP) of Five-to Eight-Membered Cyclic Olefins: Computational, Thermodynamic, and Experimental Approach. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 3137–3145. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hejl A; Scherman OA; Grubbs RH Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of functionalized low-strain monomers with ruthenium-based catalysts. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7214–7218. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Neary WJ; Kennemur JG Variable Temperature ROMP: Leveraging Low Ring Strain Thermodynamics to Achieve Well-Defined Polypentenamers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 4935–4941. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tuba R; Grubbs RH Ruthenium catalyzed equilibrium ring-opening metathesis polymerization of cyclopentene. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 3959–3962. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Neary WJ; Isais TA; Kennemur JG Depolymerization of Bottlebrush Polypentenamers and Their Macromolecular Metamorphosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 14220–14229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Martin B; Posseme F; Le Barbier C; Carreaux F; Carboni B; Seiler N; Moulinoux JP; Delcros JG (Z)-1,4-diamino-2-butene as a vector of boron, fluorine, or iodine for cancer therapy and imaging: Synthesis and biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 2863–2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Huang WM; Zhu ZS; Wen J; Wang X; Qin M; Cao Y; Ma HB; Wang W Single Molecule Study of Force-Induced Rotation of Carbon-Carbon Double Bonds in Polymers. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Love JA; Morgan JP; Trnka TM; Grubbs RH A practical and highly active ruthenium-based catalyst that effects the cross metathesis of acrylonitrile. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4035–4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Li LY; Raghupathi K; Song CF; Prasad P; Thayumanavan S Self-assembly of random copolymers. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13417–13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sprott KT; McReynolds MD; Hanson PR Ring-closing metathesis strategies to amino acid-derived P-heterocycles. Synthesis 2001, 2001, 612–620. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.