Abstract

Percutaneous ventricular assist devices have been used for high-risk ventricular tachycardia ablation when hemodynamic decompensation is expected. Utilizing a case example, we present our experience with development of a coordinated, team-based approach focused on periprocedural management of patients with high-risk ventricular tachycardia. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Key Words: ablation, hemodynamics, multidisciplinary care, percutaneous mechanical circulatory support, ventricular tachycardia

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AHD, acute hemodynamic decompensation; CPO, cardiac power output; HR-VTA, high-risk ventricular tachycardia ablation; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; pVAD, percutaneous ventricular assist device; SVO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; VTA, ventricular tachycardia ablation

Central Illustration

Ventricular tachycardia ablation (VTA) is increasingly performed in patients with advanced heart failure.1 Ablation often requires induction and mapping of ventricular arrhythmias and may be associated with acute hemodynamic decompensation (AHD). Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) during VTA has increased, and observational studies using the PAINESD score suggest a mortality benefit.2 The PAINESD score estimates the risk of AHD during VTA. Among patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and a PAINESD score ≥15, MCS during VTA decreased 30-day rehospitalization, repeat ablation, recurrent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy, and 3-month mortality.3 Moreover, prophylactic implementation of MCS in high-risk patients is associated with a 3.5-fold reduction in mortality or need for heart transplantation.4,5

Learning Objectives

-

•

Acute hemodynamic decompensation may occur during ablation of ventricular tachycardia irrespective of the mapping/ablation strategy.

-

•

Objective measures of cardiac function and tissue perfusion can be used to assess the efficacy of mechanical circulatory support and guide weaning.

-

•

A multidisciplinary approach to periprocedural hemodynamic management with objective measures of perfusion and a framework for weaning mechanical support ensures the best clinical outcome for the patient.

Although evidence supports MCS during high-risk VTA (HR-VTA), pathways for case selection, preprocedural assessment, and multidisciplinary coordination have not been elucidated. Currently, there are no established weaning protocols to guide postprocedure care. We present a multidisciplinary approach for HR-VTA requiring MCS, including recommendations for weaning.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old man with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (20%-25%) due to ischemic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular (LV) aneurysm, and history of coronary artery bypass grafting, mitral valve repair, and closure of an atrial septal defect presented for evaluation of ventricular tachycardia (VT), resulting in appropriate ICD therapy. He had a history of VT storm treated with catheter ablation using a substrate-based approach and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support 5 months prior, and had previously failed treatment with amiodarone, sotalol, and dofetilide. The patient presented after multiple ICD shocks for sustained monomorphic VT. He was evaluated by electrophysiology and considered a candidate for repeat VT ablation; however, the patient preferred medical therapy. He was discharged on sotalol and re-admitted 11 days later after receiving 4 shocks for monomorphic VT with a single morphology. At this point, the patient elected for repeat catheter ablation.

A multidisciplinary conference with electrophysiology and a heart failure cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, and cardiac anesthesiologist was convened. Electrophysiology recommended an activation and entrainment mapping strategy rather than a substrate-based approach given the recurrence of VT within 6 months of ablation. Pre-emptive MCS with a percutaneous ventricular assist device (pVAD) was planned because the patient was deemed high risk (PAINESD score of 17).

Anesthesia

Before induction, American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors were placed, cerebral oximetry was initiated, and the radial artery was cannulated. General anesthesia was induced with etomidate and succinylcholine, followed by endotracheal intubation. A pulmonary artery catheter was placed via the right internal jugular vein. Norepinephrine and epinephrine infusions were titrated to maintain blood pressure within 20% of baseline, cerebral saturation >60% and within 20% of baseline, as well as cardiac index >2 L/min/m2, mixed venous oxygen saturation (SVO2) >60%, cardiac power output (CPO) >0.6 W, and serum lactate <2 mmol/L.

Percutaneous Ventricular Support

The right common femoral artery was accessed under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance, and angiography confirmed position before placement of a 6-F sheath. A pigtail catheter was positioned at the abdominal aortic bifurcation, and an angiogram was performed to evaluate for significant peripheral artery disease. Heparin was administered to maintain activated clotting time >300 seconds. The arteriotomy site was progressively dilated before placing a 14-F peel-away sheath. The pigtail catheter was advanced into the left ventricle, and a pVAD was placed with resultant 3.8 L/min flow.

Ablation

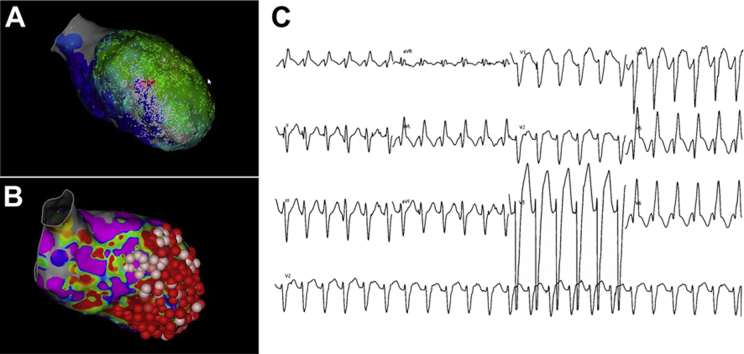

Right femoral vein access was obtained under ultrasound guidance. A long, fixed curve sheath was used to perform a transseptal puncture and was exchanged for a large curl deflectable sheath. An irrigated force-sensing ablation catheter was advanced through the sheath into the left ventricle. A detailed bipolar voltage map of the left ventricle showed a large anterior wall scar corresponding to the location of the aneurysm (Figure 1). VT was induced and mapped using a multielectrode splined mapping catheter; the activation map identified a critical isthmus-based activation pattern and presence of mid-diastolic potentials. Ablation was performed, and the clinical VT was no longer inducible after targeted ablation. Additional ablation was performed around and within the scar with a core isolation approach. Pacing at high output confirmed the scar was electrically unexcitable postablation.

Figure 1.

Left Ventricular Mapping: Clinical Ventricular Tachycardia

(A) Left ventricular activation map of the clinical ventricular tachycardia. (B) Left ventricular voltage map showing large anterior scar extending to the septum along with ablation lesions. (C) Left bundle morphology, superior axis, precordial transition in V5, and positive in lead I.

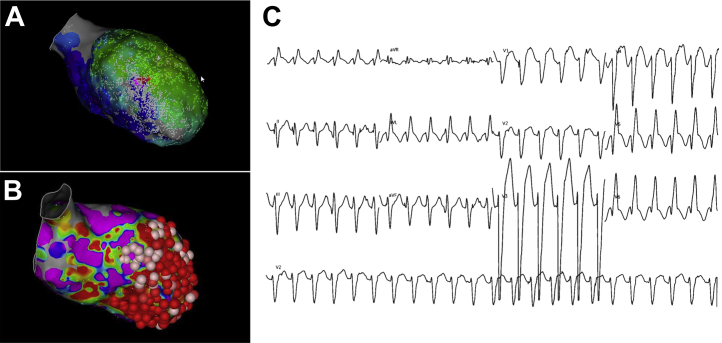

Induction was attempted after scar homogenization, and a second, morphologically distinct VT was induced. An activation map of the left ventricle was created, but the full cycle length of the tachycardia was not captured in the LV endocardium, suggesting an epicardial component of the circuit (Figure 2). Additional ablation was performed at the exit site based on findings of the activation map. After extensive endocardial ablation, a sustained nonclinical VT with an epicardial component remained inducible, but the initial clinical VT remained noninducible.

Figure 2.

Left Ventricular Mapping: Nonclinical Ventricular Tachycardia

(A) Two views of a left ventricular activation map of induced nonclinical ventricular tachycardia showing focal breakthrough from the anterior wall. (B) Right bundle, inferior axis, negative in lead I and negative in V2 to V6.

Weaning MCS and Postprocedure Care

Postablation, the CPO was 0.9 W, consistent with baseline, and was maintained as the pVAD was weaned from “Auto” to P2 over 40 minutes. On P2, the arterial pulsatility was preserved and mean arterial pressure was 70 mm Hg on norepinephrine 3 μg/kg/min, SVO2 was >60%, and serum lactate was 1.4 mmol/L. The pVAD was removed, and hemostasis was obtained with suture-based closure devices. The patient was extubated, and his care was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit where norepinephrine was weaned, and his home heart failure medication regimen was restarted. He was discharged home 2 days’ postablation. At 1-year follow-up, he remains free of sustained VT and has not required ICD therapy.

Question 1: What Is the Benefit of MCS During HR-VTA?

MCS improves hemodynamics and continuously unloads the left ventricle; we believe this action translates into improved end-organ perfusion during HR-VTA. Indeed, cerebral desaturation has been observed during fast VT (tachycardia cycle length <300 milliseconds), but with MCS, the incidence of cerebral desaturation decreases significantly.6 Prophylactic MCS is superior to a rescue strategy, and 30-day mortality is higher with rescue compared with pre-emptive pVAD implantation in high-risk patients experiencing AHD during VTA.7 Even with successful rescue and improved hemodynamics, 40.2% of patients with AHD during VTA died within 30 days.8 Furthermore, pre-emptive MCS may reduce inotropic and vasopressor usage and avoid the associated myocardial oxygen demand and impairment in tissue perfusion. This underscores the importance of preprocedure risk stratification and pre-emptive MCS. Pre-emptive MCS should be considered irrespective of VTA strategy, as activation and entrainment techniques as well as substrate mapping may precipitate AHD. We prefer pVAD because of the ease of placement and its ability to unload the left ventricle. The PAINESD score has been validated as an effective way to risk stratify patients; our use of objective perfusion measures provides additional guidance when MCS may be warranted and can guide weaning.

Question 2: What Is the Approach to Multidisciplinary Care?

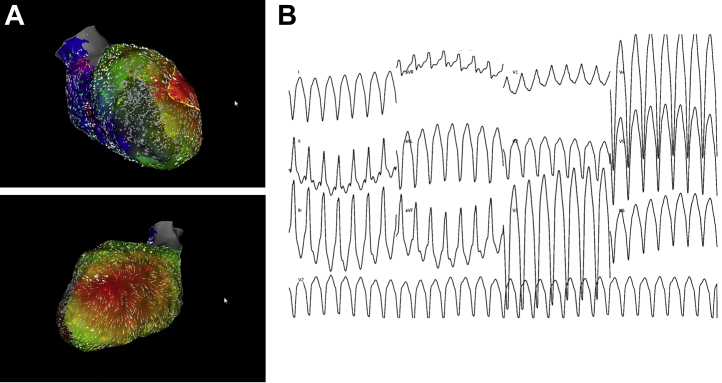

Multidisciplinary care in a dedicated VT unit favorably affects VT recurrence and hospitalization.9 However, multidisciplinary management of HR-VTA is not well established. Ideally, HR-VTA includes interdisciplinary expertise from interventional cardiology, a heart failure specialist, cardiac anesthesiologist, and occasionally, a cardiac/vascular surgeon, in addition to the treating electrophysiologist (Table 1). MCS implantation and explantation should be performed by an experienced interventional cardiologist who is proficient with large-bore vascular access and adheres to best practices (Table 2). The interventionalist and electrophysiologist coordinate the timing of MCS insertion as well as need for epicardial access. The cardiac anesthesiologist has a critical role in preprocedure planning and periprocedural hemodynamic management. The anesthesiologist is tasked with maintaining end-organ perfusion even in the presence of recurrent VT and AHD (Figure 3). The heart failure cardiologist assists with optimizing volume status before the procedure, and, at our center, heart failure medications are typically held to reduce periprocedural hypotension. They also assist with weaning MCS, provide postprocedure care, and are instrumental in assessing candidacy for advanced heart failure therapies. When epicardial access is planned, cardiothoracic surgery is also involved with multidisciplinary care.

Table 1.

Multidisciplinary Periprocedural Care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; MCS = mechanical circulatory support; PA = pulmonary arterial; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; VTA = ventricular tachycardia ablation.

Table 2.

Best Practices for Implant and Explant of MCS

| Vascular access | Ultrasound and fluoroscopy-guided access |

| Access with micropuncture kit and confirmation with femoral angiography | |

| Abdominal aortogram to assess for peripheral artery disease | |

| Intraprocedural monitoring | Periodic assessment for hematoma or oozing around the sheath given prolonged nature of VTA and high ACTs (>300 s) |

| Assessment of distal limb perfusion, recommend ipsilateral or contralateral femorofemoral bypass in case of occlusive large-bore sheath | |

| Closure | Pre-close technique recommended |

| Contralateral femoral or left radial arterial access for “dry-closure” or endovascular balloon tamponade, especially in patients with increased bleeding risk (long-term anticoagulation, access site calcification, vascular tortuosity, and/or large pannus) | |

| Reversal of anticoagulation with protamine sulfate in cases of persistent bleeding |

ACT = activated clotting time; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

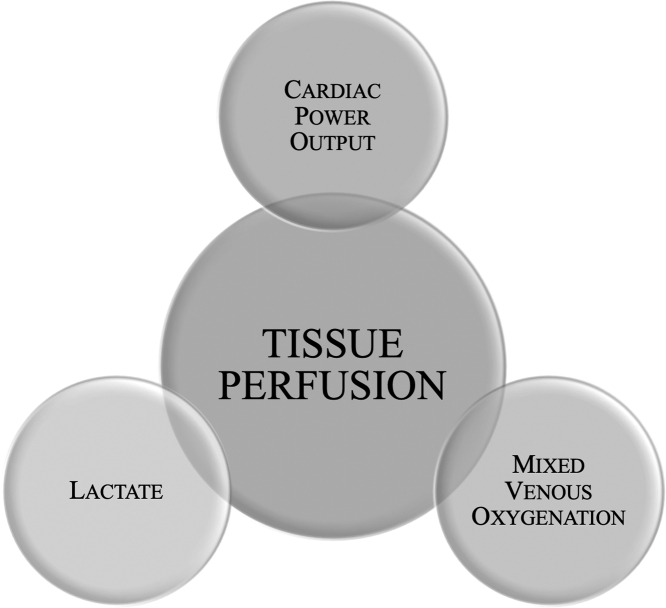

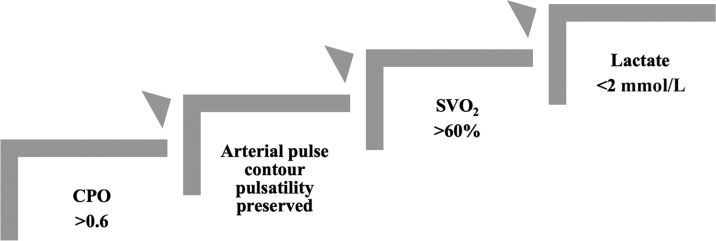

Figure 3.

Objective Assessment of Tissue Perfusion

Maintenance of end-organ perfusion even during induction of ventricular tachycardia is paramount. We aim to maintain cardiac index >2 L/min/m2, mixed venous oxygenation >60%, cardiac power output >0.6 W, and lactate <2 mmol/L, as well as blood pressure and cerebral oximetry 60% to 90% and within 20% of baseline.

Question 3: What Parameters Guide Weaning of MCS?

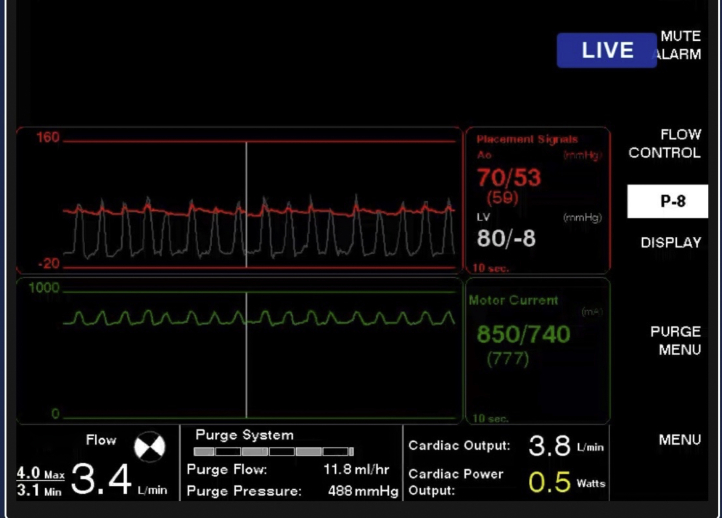

During HR-VTA, we monitor CPO and objective measures of end-organ perfusion (Figure 3) as perfusion delineates the efficacy of MCS and defines our weaning criteria (Figure 4). Weaning begins with assessment of CPO, as this is an important marker of end-organ perfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock.10 A CPO >0.6 W suggests adequate intrinsic cardiac function. Next, the arterial waveform is evaluated; loss of pulsatility indicates dependence on MCS (Figure 5). Pulsatility should be preserved without significant vasopressor or inotropic support. A SVO2 >60% and lactate levels <2 mmol/L also suggest that tissue perfusion is adequate. We suggest decreasing device flows and reassessing weaning criteria before withdrawing MCS. Delayed weaning should be considered when baseline LV ejection fraction is <20% and/or CPO is <0.6 W. In our experience, objective assessment of perfusion helps avoid AHD during HR-VTA even without MCS, as these parameters guide vasoactive support and suggest when ventricular arrhythmias should be terminated and/or mapping discontinued.

Figure 4.

Weaning MCS

Prolonged tachycardia and hypotension may provoke myocardial ischemia and stunning, increasing reliance on mechanical circulatory support (MCS). We recommend assessment of cardiac power output (CPO), pulsatility of the arterial waveform, mixed venous oxygenation saturation (SVO2), and lactate before decreasing device flows. We suggest reassessing weaning criteria after each reduction and before withdrawing MCS.

Figure 5.

Loss of Intrinsic Arterial Pulsatility

Hemodynamics from the percutaneous ventricular assist device console showing loss of pulsatility of native heart and dependence on mechanical circulatory support.

Conclusions

We present an approach to HR-VTA with MCS and highlight the importance of multidisciplinary coordination and objective hemodynamic assessment. This potentially paradigm-shifting approach to HR-VTA with MCS should be interrogated systematically to evaluate clinical outcomes.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

This work was supported by research funding from Abiomed. Dr Bharadwaj is a consultant, speaker, and proctor for Abiomed. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

JetPub Scientific Communications LLC, supported by Abiomed, assisted in the preparation of this paper, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Tzou W.S., Tung R., Frankel D.S., et al. Ventricular tachycardia ablation in severe heart failure: an international ventricular tachycardia ablation center collaboration analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariani S., Napp L.C., Lo Coco V., et al. Mechanical circulatory support for life-threatening arrhythmia: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2020;308:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aryana A., Gearoid O'Neill P., Gregory D., et al. Procedural and clinical outcomes after catheter ablation of unstable ventricular tachycardia supported by a percutaneous left ventricular assist device. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muser D., Castro S.A., Liang J.J., Santangeli P. Identifying risk and management of acute haemodynamic decompensation during catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018;7:282–287. doi: 10.15420/aer.2018.36.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muser D., Liang J.J., Castro S.A., et al. Outcomes with prophylactic use of percutaneous left ventricular assist devices in high-risk patients undergoing catheter ablation of scar-related ventricular tachycardia: a propensity-score matched analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1500–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller M.A., Dukkipati S.R., Chinitz J.S., et al. Percutaneous hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 during scar-related ventricular tachycardia ablation (PERMIT 1) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:151–159. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.975888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathuria N., Wu G., Rojas-Delgado F., et al. Outcomes of pre-emptive and rescue use of percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with structural heart disease undergoing catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2017;48:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10840-016-0168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kar B., Gregoric I.D., Basra S.S., Idelchik G.M., Loyalka P. The percutaneous ventricular assist device in severe refractory cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:688–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Della Bella P., Baratto F., Tsiachris D., et al. Management of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias: long-term outcome after ablation. Circulation. 2013;127:1359–1368. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basir M.B., Kapur N.K., Patel K., et al. Improved outcomes associated with the use of shock protocols: updates from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:1173–1183. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]