Abstract

Background:

Alcohol-induced blackouts describe memory loss resulting from alcohol consumption. Approximately half of college students report experiencing a blackout in their lifetime. Blackouts are associated with an increased risk for negative consequences, including serious injury. Research has documented two types of blackouts, en bloc (EB) and fragmentary (FB). However, research is limited by lack of a validated measure that differentiates between these two forms of blackout. This study used a mixed methods approach to improve the assessment of FB and EB among young adults. We specifically sought to improve the existing Alcohol-Induced Blackout Measure (ABOM), which was derived from a relatively small pool of items that did not distinguish FB from EB.

Methods:

Study 1 used three rounds of cognitive interviewing with college students (N=31) to refine existing assessment items. Nineteen refined blackout items were retained for Study 2. Study 2 used face validity, factor analysis, item response theory, and external validation analyses to test the two-factor blackout model among heavy-drinking college students (N=474) and to develop and validate a new blackout measure (ABOM-2).

Results:

Iterative factor analyses demonstrated that the items were well-represented by correlated EB and FB factors, consistent with our hypothesis. External validation analyses demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity, and there was preliminary evidence for the two factors having differential predictive validity (e.g., FB correlated with enhancement drinking motives, while EB correlated with coping and conformity motives).

Conclusions:

The Alcohol-Induced Blackout Measure-2 (ABOM-2) improves measurement of blackout experiences among college students and will facilitate examination of EB and FB as differential predictors of alcohol-related outcomes in future studies.

Keywords: Blackout, memory, assessment, young adult, measurement

Introduction

Alcohol-induced blackouts describe memory loss resulting from acute alcohol consumption. They typically occur at high blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels (~.14 g/dl), although risk for alcohol-induced blackout begins around .06 g/dl (Hartzler & Fromme, 2003a; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016). During an alcohol-induced blackout, the ability to transfer memories to long-term storage (i.e., memory consolidation) is either temporarily or permanently blocked, whereas short-term memory is relatively unaffected (Jennison & Johnson, 1994; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016). Approximately half of college students report experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout in their lifetime, with past year estimates ranging from 20 to 50% (e.g., Barnett et al., 2014; Hingson et al., 2016; Marino & Fromme, 2015; Wechsler et al., 1998). This is concerning because alcohol-induced blackouts are associated with an increased risk for negative consequences, such as serious injury or death (Hingson et al., 2016), risky sexual behavior (Merrill et al., 2016; Silveri et al., 2014), and poor academic performance (Park, 2004). Perhaps most troubling is that alcohol-induced blackouts are associated with neurotoxicity and related outcomes, such as poorer cognitive functioning (e.g., lower performance on event-based prospective memory tasks; Zamroziewicz et al., 2017). Because adolescence and young adulthood are critical periods of neurodevelopment, college students are in a “window of vulnerability” with respect to the impact of heavy alcohol use on the brain (e.g., Hermens et al., 2013; Pfefferbaum et al., 1994). Alcohol-induced blackouts at age 20 also predict the occurrence of alcohol use disorder (AUD) five years later (Studer et al., 2019), pointing to the importance of prevention, identification, and treatment for college students experiencing alcohol-induced blackouts.

When asked about their alcohol-induced blackout experiences, individuals with AUD and young adults who tend to drink for more social reasons consistently report two types of alcohol-induced blackout: en bloc and fragmentary (Goodwin et al., 1969; Hartzler & Fromme, 2003a; Miller, et. al., 2018). En bloc blackouts (EBs) are characterized by complete memory loss from a specific point in the drinking occasion onwards (Rose & Grant, 2010; White, 2003). EBs are thought to occur at high BAC levels (e.g., around 0.31 g/dl; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016). When consumed at such high levels, alcohol disrupts the consolidation of encoded information into long-term memory, resulting in a failure to retrieve information even with prompting (Hartzler & Fromme, 2003a). Fragmentary blackouts (FBs), in comparison, describe temporary memory impairment, meaning individuals can recall lost memories after being reminded with cues (Perry et al., 2006). FBs are thought to occur at a wide range of BACs (e.g., between .14 g/dl and .20 g/dl; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016), and individuals often describe these memories as “fuzzy” (Hartzler & Fromme, 2003a; Hartzler & Fromme, 2003b; Lee et al., 2009). Indeed, FBs are thought to be more related to a process of not remembering (rather than forgetting), and result from difficulties with memory retrieval, such as impaired encoding (Rose & Grant, 2010). As such, EBs and FBs differ phenomenologically and seem to occur as a result of different neurobiological processes (Wetherill & Fromme, 2016).

Although EBs and FBs are thought to be relatively distinct processes, there exist no standardized measures that separately assess these two alcohol-induced blackout types. The authors are aware of only one attempt to validate a measure that included both EB and FB assessment items. Specifically, Miller and colleagues (2019) investigated the factor structure of 10 existing and investigator-generated alcohol-induced blackout assessment items, but they found that a single alcohol-induced ‘blackout’ component (rather than two separate EB and FB factors) fit the data best. We propose that the relatively small pool of items may not have adequately differentiated between FB and EB experiences, precluding extraction of two factors (e.g., Bollen & Lennox, 1991). It is also possible that participants did not adequately understand the items; for example, memory loss “while drinking” may be misinterpreted as memory loss only during (and not also after) a drinking episode (see Table 2 for additional examples). These weaknesses limit construct validity and increase likelihood of measurement error, prompting a need for expansion upon and improvement of the items.

Table 2.

Comparison of Initial Blackout Items and Items Used in Study 2

| Original Source | Round 1 Item (adapted for frequency in the past 30 days) | Final Item for Study 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Russell, 1994 (TWEAK) | In the past 30 days, how often has a friend or family member told you about things you said or did while you were drinking that you could not remember? | In the past 30 days, how often has someone told you about things you said or did while you were drinking that you could not remember? |

| Hurlbut & Sher, 1992 (YAAPST) | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened the morning after drinking and been unable remember something you did or said? | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened the morning after drinking and been unable remember something you did or said? |

| Hingson et al., 2016 | In the past 30 days, how often did you forget where you were or what you did while drinking? | DROPPED – “while drinking” interpreted as asking about memory only during (not also after) a drinking episode |

| Jellinek, 1946 | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often did you wake up in the morning after a party with no idea where you had been or what you had done after a certain point? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often did you wake up with no idea where you had been or what you had done after a certain point? En bloc |

| Labhart et al., | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you unable to remember what happened, even for a short period of time? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you unable to remember a few minutes of what happened? Fragmentary |

| author-generated alternative | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you able to remember a few minutes of what happened only after being reminded later? Fragmentary | |

| Marino & Fromme, 2018 | In the past 30 days, how often did you have difficulty remembering things you said or did, or events that happened, while you were drinking? | DROPPED – double-barreled item |

| Merrill et al., 2016 | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you unable to remember some part of the day or night? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you unable to remember a small part of the day? fragmentary |

| author-generated alternative | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you able to remember a small part of the day only after being reminded? Fragmentary | |

| White & Labouvie, 1989 (RAPI) | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you suddenly found yourself in a place that you could not remember getting to? | In the past 30 days, during a drinking episode, how often have you suddenly “come to” in a place that you could not remember getting to? En bloc |

| author-generated alternative | In the past 30 days, while still in a drinking situation, how often have you suddenly realized that you have no memory of how you got to be where you are? En bloc | |

| Nelson et al., 2004 | In the past 30 days, how often have you drank enough that, even though you did not pass out while drinking, the next day you could not remember things you had said or done? | DROPPED – difficulty distinguishing between blacking out and passing out |

| Saunders et al., 1993 (AUDIT) | In the past 30 days, how often have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? | In the past 30 days, how often have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? |

| O’Neill et al., 2002 (ASQ) | In the past 30 days, how often have you forgotten part of an evening after drinking alcohol? | DROPPED – overlap with other items |

| Read et al., 2006 (YAACQ) | In the past 30 days, how often have you woken up in an unexpected place after heavy drinking? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you woken up in an unexpected place? En bloc |

| Read et al., 2006 (YAACQ) | In the past 30 days, how often have you not been able to remember large stretches of time while drinking heavily? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you not been able to remember large stretches of time? En bloc |

| author-generated alternative | In the past 30 days, how often were you not able to remember hours at a time after drinking heavily? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you unable to remember hours at a time? En bloc |

| Read et al., 2006 (YAACQ) | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened the day after drinking and found that you could not remember a part of the evening before? | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened the day after drinking and found that you could not remember a part of the evening before? |

| Schuckit et al., 2015 | In the past 30 days, how often have you been in a drinking situation where you couldn’t remember things? | DROPPED – interpreted as asking about memory only during (not also after) a drinking episode |

| Sweeney, 2008 | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you lost several hours of your life with no idea what happened? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you lost several hours of your life with no idea what happened? en bloc |

| Wetherill & Fromme, 2011 | In the past 30 days, after drinking heavily, have you experienced a period of time that you could not remember things you said or did? | DROPPED – overlap with other items; “drinking heavily” and “period of time” described as too subjective |

| Wetherill & Fromme, 2011 | In the past 30 days, when you experienced difficulty remembering things that you said or did while drinking, how often did you later remember when given cues or reminded later? | In the past 30 days, how often did you have to be reminded about things you had previously forgotten due to alcohol use? fragmentary |

| Wetherill et al., 2013 | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, have you experienced periods of time that you later could not remember? | DROPPED – overlap with other items |

| White et al., 2004 | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened from a night of drinking not able to remember things that you did or places that you went? | In the past 30 days, how often have you awakened from a night of drinking not able to remember things that you did or places that you went? |

| Miller et al., 2019 (ABOM) | In the past 30 days, how often have you had fuzzy memories of events that occurred while you were drinking? | In the past 30 days, how often have you had fuzzy memories of events that occurred while you were drinking? fragmentary |

| Miller et al., 2019 (ABOM) | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you had memories that became clear only after someone or something gave you cues or reminded you later? | In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often have you had memories that became clear only after being reminded later? fragmentary |

| Miller et al., 2018 | For the purposes of this interview, an “en bloc” blackout is defined as “being unable to remember events that happened while you were drinking, even if someone tries to remind you later.” Based on this definition, in the past 30 days, how often have you had an “en bloc” blackout as a result of alcohol use? en bloc | |

| Miller et al., 2018 | A “fragmentary” blackout is defined as “having fuzzy or incomplete memories of drinking events” – OR – “remembering drinking events only after someone or something reminded you later.” Based on this definition, in the past 30 days how often have you had a “fragmentary” blackout as a result of alcohol use? fragmentary |

Note. “DROPPED”=item was not included after Round 1 of cognitive interviews. A full description of items across each round, including reasons for dropping or revising items are available in Supplemental Materials. ABOM=Alcohol Induced Blackout Measure; ASQ=Alcohol Sensitivity Questionnaire; AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; Authors=created by authors; RAPI=Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; TWEAK=Tolerance, Worried, Eye-opener, Amnesia, and K/Cut down; YAACQ=Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire; YAPPST=Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test.

One useful approach for improving the measurement of target constructs is cognitive interviewing (Willis, 2005). Cognitive interviewing involves studying how individuals process and respond to survey questions. It evaluates the degree to which participants understand the construct of interest and, thus, is a way of assessing construct validity (Willis, 2005), or the degree to which a test accurately measures what it intends to measure (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). The goal of cognitive interviewing is to identify and address systematic sources of measurement error in survey items to better ensure that researchers are accurately measuring the construct(s) of interest (Willis, 2005). Although cognitive interviewing has been used infrequently in substance use disorder (SUD) research, it is recommended for SUD measure development, specifically during item generation and refinement (Boness & Sher, 2020). Cognitive interviewing’s focus on reducing measurement error is especially useful at this stage, given known difficulties in assessing SUD and related constructs. For example, false positives for SUD criteria such as withdrawal, tolerance, and impaired control likely result from imprecise and, therefore, inaccurately interpreted assessment items (e.g., Boness et al., 2016; Chung & Martin, 2005; Slade et al., 2013). False positives are problematic because they have the potential to influence prevalence rates as well as the identification of those in need of treatment. Consequently, cognitive interviewing provides one approach for improving the ability of items to accurately capture the target construct.

The current study used a mixed methods approach to improve the assessment of alcohol-induced blackouts among young adults. In Study 1, we aimed to refine existing EB and FB items – including the items from Miller and colleagues’ (2019) Alcohol-Induced Blackout Measure (ABOM) – using cognitive interviewing. This allowed us to develop a set of items that assess EBs and FBs separately, given most existing items in the literature fail to clearly distinguish between the two. In Study 2, we used the refined item pool from Study 1 to estimate the factor structure of the items, evaluate item characteristics, and construct a revised ABOM scale (i.e., ABOM-2).

Study 1: Qualitative Methods and Results

Sample

Participants were 31 undergraduates enrolled in introduction to psychology courses at a large Midwestern university. They were recruited via an online research participation system. Students were required to be over age 18 and report heavy drinking1 in the past 30 days. Students self-selected to participate, and course credit was awarded upon completion. Participants were on average 19.42 (SD=1.39) years of age, equally split in terms of sex and gender (52% female), and largely White (87%) and non-Hispanic (87%). In the past 30 days, participants reported an average of 1.44 (SD=1.27) drinking days per week and 3.93 (SD=2.83) drinks per occasion. Eighty-one percent (n=25) of participants reported they were “unable to remember what happened the night before because [they] had been drinking” at least once in the past year. Demographics are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in Each Round of Study 1 (N=31) and Study 2 (N=474)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (n=10) | Round 2 (n=10) | Round 3 (n=11) | N=474 | ||||

| Age M (SD) | 18.70 (1.06)a | 20.00 (1.41)a | 19.55 (1.44)a | 19.03 (1.41) | |||

| Biological sex (assigned female at birth) | 50.00 (5)a | 60.00 (6)a | 45.45 (5)a | 67.72 (321) | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female % (n) | 50.00 (5)a | 60.00 (6)a | 45.45 (5)a | 66.88 (317) | |||

| Male % (n) | 50.00 (5)a | 40.00 (4)a | 54.55 (6)a | 32.07 (152) | |||

| Trans man % (n) | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.42 (2) | |||

| Trans woman % (n) | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0) | |||

| Gender-queer/non-nonconforming/other | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.42 (2) | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 90.00 (9)a | 100.00 (10)a | 72.73 (8)a | 93.88 (445) | |||

| Black | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 9.09 (1)a | 4.43 (21) | |||

| Native or Indigenous American | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 1.69 (8) | |||

| Samoan | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.21 (1) | |||

| Asian Indian | 10.00 (1)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.42 (2) | |||

| Chinese | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 2.11 (10) | |||

| Filipino | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 1.05 (5) | |||

| Japanese | 10.00 (1) | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.84 (4) | |||

| Korean | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.42 (2) | |||

| Vietnamese | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 1.05 (5) | |||

| “Other Asian” | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 9.09 (1)a | 0.42 (2) | |||

| “Some Other Race” | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 0.00 (0)a | 1.27 (6) | |||

| Hispanic/Latinx % (n) | 0.00 (0)a | 20.00 (2)a | 18.18 (2)a | 4.85 (23) | |||

| Native English speaker % (n) | 100.00 (10)a | 100.00 (10)a | 81.82 (9)a | 96.84 (459) | |||

| Biological parent w “drinking problem” M (SD) | 10.00 (1)a | 20.00 (2)a | 18.18 (2)a | 28.48 (135) | |||

| Age of first full drink M (SD) | 15.30 (1.25)a | 15.80 (1.81)a | 16.27 (2.00)a | 15.77 (1.65) | |||

| Age first drunk M (SD) | 16.10 (1.10)a | 16.30 (2.00)a | 16.63 (1.91)a | 16.25 (1.65) | |||

| Past 30-day alcohol consumption | |||||||

| Drinking days/week | 1.72 (1.38)a | 1.57 (1.40)a | 1.07 (1.06)a | 1.76 (1.28) | |||

| Average drinks per occasion | 5.22 (1.92)a | 4.80 (3.16)a | 2.09 (2.30)b | 5.06 (2.28) | |||

| Frequency “buzzed” (days/week) | 1.13 (0.58)a | 0.98 (1.07)a | 0.75 (1.08)a | 1.33 (1.16) | |||

| Frequency drunk (days/week) | 1.03 (0.58)a | 0.74 (0.67)a | 0.53 (0.66)a | 1.14 (1.07) | |||

| Days with 5+/4+ drinks in sitting/week | 1.30 (0.93)a | 1.12 (1.37)a,b | 0.42 (0.58)b | 1.09 (1.11) | |||

| Days with 12+ drinks in sitting/week | 0.36 (0.63)a | 0.34 (0.62)a | 0.15 (0.45)a | 0.23 (0.58) | |||

| Maximum drinks M (SD) | 9.11 (4.01)a | 7.30 (4.50)a,b | 4.55 (4.16)b | 8.05 (4.38) | |||

| Past 30-day drug use % (n) | - | - | - | 51.27 (243) | |||

| AUDIT score M (SD) | 12.89 (3.92)a | 9.80 (3.82)a | 10.60 (4.22)a | 9.71 (5.33) | |||

| Any blackout past year % (n) | 80.00 (8) | 90.00 (9) | 72.63 (8) | 69.62 (330) | |||

| ABOM score M (SD) | 6.00 (3.92)a | 3.60 (2.72)a,b | 2.20 (2.78)b | 3.32 (3.66) | |||

| Any blackout past month % (n) | 80.00 (8) | 80.00 (8) | 50.00 (5) | 68.99 (327) | |||

| ABOM-2 score M (SD) | - | - | - | 6.00 (6.87) | |||

| Fragmentary M (SD) | - | - | - | 4.16 (4.33) | |||

| En bloc M (SD) | - | - | - | 1.85 (2.99) | |||

| Any blackout past month % (n) | - | - | - | 73.21 (347) | |||

| Drinking motives M (SD) | |||||||

| Social | - | - | - | 16.59 (5.44) | |||

| Coping | - | - | - | 10.89 (4.40) | |||

| Enhancement | - | - | - | 15.22 (5.33) | |||

| Conformity | - | - | - | 7.26 (3.28) | |||

| BYAACQ M (SD) | 6.88 (5.17)a | 4.30 (3.80)a | 7.73 (7.16)a | 6.27 (4.38)† | |||

| EMQ M (SD) | - | - | - | 11.79 (10.80) | |||

| DERS M (SD) | - | - | - | 37.46 (12.06) | |||

| GAD-7 M (SD) | 5.80 (7.79)a | 3.70 (4.62)a | 4.55 (4.63)a | 6.34 (5.72) | |||

| PHQ-9 M (SD) | 6.00 (7.15)a | 3.10 (4.12)a | 5.63 (6.98)a | 6.77 (5.99) | |||

| ISI M (SD) | - | - | - | 7.61 (5.54) | |||

Note. For race participants could select more than one option. Values with different letters in their superscripts for Study 1 differ significantly (p < .05) from one another according to t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Pairwise comparisons were only made if the omnibus 3-way ANOVA (for continuous variables) or Fisher’s Exact Test (for categorical variables) was significant. Dashed line indicates a measure that was not administered for a given study.

excludes item indexing blackout from sum score. Ns may not add up to total N given participants had the option not to respond to certain items and therefore their responses were missing for that item.

AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; ABOM=Alcohol-Induced Blackout Measure; EMQ=Everyday Memory Questionnaire; DERS=Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale; GAD-7=Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item; PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item; ISI=Insomnia Severity Index.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants self-reported on age, gender, sex, race, ethnicity, native language, and family history of a “drinking problem” (see Table 1).

Alcohol-Induced Blackout items.

The initial alcohol-induced blackout item pool included 23 items (see Table 2). In April 2019, the authors collected a list of alcohol-induced ‘blackout’ items used in published studies to date. This resulted in a list of 67 items, 28 of which were self-report and non-redundant (e.g., experimental recall/recognition paradigms could not be included; some items were used in multiple studies). Items that differed only slightly (e.g., “having difficulty remembering things you said or did” vs “could not remember things you had said or done”) were also reduced to a single item, resulting in a list of 23 items (see Table 2). The initial response options were never (0), 1 time (1), 2–3 times (2), weekly (3), or twice a week or more (4) in the past 30 days.

Alcohol consumption.

Seven items assessing past 30-day alcohol consumption were adapted from Sher and Rutledge (2007). Items assessed quantity, frequency, binge frequency, heavy drinking (12+ drinks) frequency, frequency buzzed, frequency drunk, and maximum number of drinks in a single sitting. Items were standardized and summed to create a “heaviness of consumption” composite. Participants also reported the age at which they consumed their first full drink of alcohol and the first time they became drunk.

Alcohol-related risk.

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Kahler et al., 2005, 2008). Participants indicated (yes/no) if they had experienced 24 consequences, such as feeling sick to one’s stomach, as a result of drinking in the past month. The alcohol-induced blackout item was removed from validation analyses to avoid confounding. Responses were summed, with higher scores indicating more consequences (range=0–23). In addition, participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993), a 10-item self-report instrument assessing consumption and harmful drinking. Higher scores (range=0–40) are associated with a greater likelihood of AUD (Babor et al., 2001). The AUDIT has consistently demonstrated favorable psychometric properties among college students (e.g., Fleming et al., 1991; Kokotailo et al., 2004). For substantive analyses, item 8 (blackout) was removed to avoid confounding.

Anxiety and depression.

Participants completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9). The GAD-7 is an anxiety disorder screening tool and symptom severity measure. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety symptoms. The PHQ-9 assesses and screens for symptoms of depression, with higher scores indicating more severe depression symptoms. Both scales assessed the previous two weeks and have been validated for use with college students (e.g., Byrd-Bredbenner et al., 2021; Keum, et al., 2018).

Procedure

Study 1 included two phases: a self-report Qualtrics survey completed in the laboratory and a cognitive interview completed face-to-face with a trained research assistant (RA). Cognitive interviews assessing participant interpretations for each initial alcohol-induced blackout item were conducted in an iterative process (see Table 1). Three rounds of interviews were completed, with a target sample of 10 participants per round. All interviews were conducted by the first, second, and third authors, under the training and supervision of the first author.

During the cognitive interview, participants were instructed to use a “think-aloud procedure” (Willis, 1994) when deciding on their response. This provides in-depth information on a participant’s responses, with little interviewer intervention. Standardized probes were used to evaluate whether participants understood the key constructs within each item and to assess the appropriateness of the instructions and response scale(s) (e.g., “Can you tell me in your own words what this question is asking?” Probes available at https://osf.io/gnfu4/). Both the think-aloud and standard probe procedures have been used to reduce measurement error in alcohol survey items (e.g., Boness & Sher, 2020; Chung & Martin, 2005). Interviews were conducted in-person for Round 1 and via Zoom (due to COVID-19) for Rounds 2 and 3. The average duration of interviews was 45 minutes (SD=17.75). Between rounds of interviews, alcohol-induced blackout items were revised based on the findings of the most recent round, resulting in a new set of items for the subsequent round of interviews (see Supplemental Table 1 for the items included in each round and the rationale for changes).

All interviews were video-recorded. Weekly meetings among the first, second, and third authors were held to review video and ensure the accuracy of the information documented in the interviewer sheets. All methods and procedures were reviewed by the university’s institutional review board (IRB #2018721).

Data Analysis

Consistent with recommendations (Willis, 1994), results were analyzed using a narrative, text-summary approach. This approach allows identification of prominent themes, conclusions, and problems that occurred repeatedly and is most appropriate when the overall goal of cognitive interviewing is to make revisions quickly for further testing. Changes from the initial item pool to the final item pool are displayed in Table 2 and described more thoroughly in Supplemental Table 1.

Results

Relationship between fragmentary and en bloc blackouts.

Several participants reported FB experiences that later progressed to EB experiences. Thus, they were endorsing both EBs and FBs in reference to the same drinking episode. For example, participants sometimes reported they had some fuzzy memories (fragmentary) prior to experiencing a full (en bloc) blackout: “The time I have been most drunk… I didn’t remember several hours the next day. I woke up in my boyfriends’ room and… just for a second was like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know I was here.’ I think I have a couple of really brief memories from that time period but nothing solid… I sort of remembered saying something to someone but [people told me things I did] that I have no memory of. I couldn’t remember anything” (ID21: 18y, White, non-Hispanic, female, AUDIT=12). This suggests that FBs may be a precursor to EBs in some situations.

Difficulty assessing fragmentary blackouts.

Fragmentary items were more often misunderstood than en bloc items, and participants had more difficulty reporting examples of FBs than EBs. For example, one participant (ID29: 23y, Taiwanese, female, AUDIT=9) accurately paraphrased the item, “In the past 30 days, as a result of alcohol use, how often were you only able to remember a few minutes of what happened after being reminded later?” as, “Have I ever been able to remember a few minutes after a friend reminded me of the event?” However, when asked to provide an example of this happening, she reported: “All of us went out and I got really drunk. I remember going to a friend’s house, but I fell asleep a little or something like that. So I don’t remember the details of the events…. but I do remember being there for sure.… [I was eventually able to remember] some of it, but there are some parts of it that I don’t remember. It might also be me not paying attention during that time.” Based on this and similar comments, FBs may be more difficult to assess because they are relatively non-discrete experiences that may be confused with general memory impairment or inattentiveness. This is especially concerning, given FBs are relatively more common and therefore important to assess.

Providing participants with definitions.

In the final phase of the interview, participants were provided with operational definitions of EB and FB. Specifically, instructions stated, “For the purposes of this interview, an ‘en bloc’ blackout is defined as being unable to remember events that happened while you were drinking, even if someone tries to remind you later. A ‘fragmentary’ blackout is defined as ‘having fuzzy or incomplete memories of drinking events’ OR ‘remembering drinking events only after someone or something reminded you later.’” Participants were generally able to paraphrase these definitions of EB and FB accurately, and they were usually able to offer accurate examples of these experiences. This suggests that EB and FB are distinguishable and there may be utility in providing participants with the operational definitions of these terms.

Response scale.

Several different response scales were tested during the cognitive interviews (see Supplemental Table 1). The stem for all iterations of the scale read, “In the past 30 days, how often have you…[blackout item]?” The initial set of items used the original ABOM response scale: 0 (never), 1 (1 time), 2 (2–3 times), 3 (weekly), and 4 (twice weekly or more). Several respondents reported confusion about this response scale because it shifted from the number of times per month (i.e., 2=2–3 times) to the number of times per week (i.e., 4=twice a week or more). To address this, we tested several other response scale options. In general, respondents tended to prefer response scales on the same metric (e.g., number of times per week or number of times per month, not both) and those with ranges (e.g., 0=Never, 1=1–2 times). One participant stated, “I think generally the response options were easy to discern… [it] feels like a range would be more helpful because it’s hard to remember specific numbers” (ID22: 19y, Latino, male, AUDIT=11). This suggests that participants may have difficulty choosing the discrete number of times an alcohol-induced blackout has occurred. However, because the difference between 1 and 2 alcohol-induced blackouts may be important, we used a discrete scale with response options of never (0), 1 time (1), 2 times (2), 3 times (3), and 4 or more times (4) in the past 30 days and aimed to examine the usefulness of this scale quantitatively in Study 2.

Subjective nature of time frames.

Several items included vague timeframes, such as “a short period of time,” “several hours,” “large stretch of time,” and “hours at a time.” Participants reported widely varying interpretations of such timeframes. For example, when participants were asked to define “a small part of the day,” different participants responded, “a few minutes or so,” “1 to 2 hours,” and “half the night.” Widely varying interpretations may have impacted participants’ responses to the items and resulted in false positives or false negatives. To address this, we aimed to create a refined item pool that represented varying memory loss durations.

Study 2: Quantitative Methods and Results

The goal of Study 2 was to (a) quantitatively evaluate the 19 refined alcohol-induced blackout items resulting from Study 1 (see Table 2), (b) test the hypothesized structure of items using factor analyses and item response theory (IRT) analyses, and (c) evaluate the validity of EB and FB subscales. Regarding the factor structure of the items, we predicted that the items would load on two factors (representing EB and FB) and that the factors would be highly correlated. This hypothesis was premised on research suggesting that FB and EB represent distinct, but related processes with distinguishable neurobiological underpinnings (e.g., Wetherill & Fromme, 2016). In regard to validity, we expected the EB and FB subscales to be highly correlated with hazardous drinking and alcohol-related consequences (indicative of convergent validity), given they are associated with heavy use. We also expected drinking motives to be highly correlated with the subscales because motives are sometimes associated with heavy use and problems such as alcohol-induced blackout (particularly enhancement, coping, and conformity motives, which we expected to be the most correlated with the subscales; e.g., Carey & Correia, 1997). We expected the FB and EB subscales to be less correlated with symptoms of anxiety and depression, difficulties with emotion regulation, and insomnia severity (indicative of discriminant validity), given they are less directly related to heavy use but are likely still relevant to drinking (e.g., negative emotionality, including anxiety and depression, may be an etiologic risk factor for alcohol use disorder; see Boness et al., 2021). Because EB tends to occur at higher BACs (Wetherill & Fromme, 2016) and college students reporting EB (vs FB) tend to report more alcohol-related problems (Miller et al., 2018), we expected that EB scores would be more strongly associated with hazardous drinking and alcohol-related consequences than FB scores. Regarding drinking motives, we expected those drinking motives associated with heavier use (e.g., conformity, coping, and enhancement motives) to be more strongly associated with the EB subscale than the FB subscale. Study 2 hypotheses and analyses were pre-registered prior to data collection (https://osf.io/6yhpt).

Sample

Recruitment for Study 2 was identical to recruitment for Study 1. Of the 539 undergraduate students who signed up to participate, 30 did not complete the survey, 18 were not adults, 7 demonstrated implausible response time (<10min), 2 responded inconsistently (e.g., age drunk earlier than age of first drink), and 8 denied past-30-day drinking. These 65 participants were excluded, resulting in final sample of 474 participants. Demographics are available in Table 1.

Measures

In addition to all measures collected in Study 1, we also collected the following in Study 2:

Refined alcohol-induced blackout items.

A total of 19 alcohol-induced blackout items refined from Study 1 were included in Study 2. This included 7 fragmentary items, 7 en bloc items, and 5 ambiguous items (not clearly representing FB or EB; see Table 3). Items were rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (4+ times) in the past 30 days.

Table 3.

Face Validity Outcomes for Candidate Alcohol-Induced Blackout Items

| Short Version of Item | Type | n | Definitely fragmentary | Probably fragmentary | Unsure | Probably en bloc | Definitely en bloc | % correct | % uncertain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. unable to remember a few minutes of what happened | Fragmentary | 469 | 200 | 195 | 34 | 26 | 14 | 84.2 | 7.25 |

| 2. unable to remember a small part of the day | Fragmentary | 469 | 121 | 185 | 50 | 83 | 30 | 65.2 | 10.66 |

| 3. reminded about things you had previously forgotten | Fragmentary | 471 | 138 | 193 | 57 | 52 | 31 | 70.3 | 12.10 |

| 4. fuzzy memories of events | Fragmentary | 472 | 200 | 223 | 36 | 8 | 5 | 89.6 | 7.63 |

| 5. memories that became clear after being reminded | Fragmentary | 471 | 232 | 183 | 33 | 17 | 6 | 88.1 | 7.01 |

| 6. able to remember a few minutes after being reminded | Fragmentary | 471 | 223 | 183 | 26 | 27 | 12 | 86.2 | 5.52 |

| 7. able to remember a small part of the day after being reminded | Fragmentary | 470 | 205 | 189 | 37 | 25 | 14 | 83.8 | 7.87 |

| 8. wake up with no idea where you had been or what you had done | En bloc | 470 | 8 | 19 | 31 | 101 | 311 | 87.7 | 6.60 |

| 9. suddenly “come to” in a place that you could not remember | En bloc | 469 | 25 | 104 | 45 | 151 | 144 | 62.9 | 9.59 |

| 10. woken up in an unexpected place | En bloc | 471 | 6 | 33 | 35 | 167 | 230 | 84.3 | 7.43 |

| 11. not been able to remember large stretches of time | En bloc | 469 | 11 | 39 | 28 | 151 | 240 | 83.4 | 5.97 |

| 12. unable to remember hours at a time | En bloc | 472 | 13 | 73 | 39 | 187 | 160 | 73.5 | 8.26 |

| 13. lost several hours of your life with no idea what happened | En bloc | 470 | 13 | 25 | 21 | 116 | 295 | 87.4 | 4.47 |

| 14. suddenly realized you have no memory | En bloc | 470 | 12 | 40 | 37 | 121 | 260 | 81.1 | 7.87 |

| 15. someone told about things you said or did | Ambiguous | 471 | 25 | 85 | 54 | 167 | 140 | N/A | 11.46 |

| 16. awakened and been unable to remember | Ambiguous | 471 | 36 | 143 | 65 | 117 | 110 | N/A | 13.80 |

| 17. unable to remember what happened the night before | Ambiguous | 469 | 8 | 34 | 46 | 135 | 246 | N/A | 9.81 |

| 18. awakened and could not remember a part of the evening | Ambiguous | 470 | 55 | 157 | 53 | 112 | 93 | N/A | 11.28 |

| 19. awakened not able to remember things or places | Ambiguous | 471 | 2 | 24 | 35 | 132 | 274 | N/A | 7.43 |

Note. “Face valid” items depicted in bold. Boxed responses coded as ‘correct.’ Shaded boxes indicate how the majority of the participants classified the “ambiguous” items. N/A = not applicable.

Drug use.

A single (yes/no) indicator of past 30-day drug use was estimated based on participant responses to past-30-day, non-prescription use of cannabis, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, methamphetamine, pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, sedatives or barbiturates, and cough or cold medicine, given research demonstrating drug use increases the likelihood of alcohol-induced blackout (White, 2003). Items were drawn from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Drinking motives.

The 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ; Cooper, 1994) was used to assess social, coping, enhancement, and conformity motives for drinking. Higher scores indicate greater motivations. The DMQ has been extensively validated, including for use in college students (e.g., Martin et al., 2016).

Emotion regulation.

Participants also completed the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale-18 (Victor & Klonsky, 2016), an 18-item scale where higher scores indicate greater difficulties with regulating emotions. The original DERS was validated in a college student sample (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), and the DERS-18 was partially validated in a college student sample (Victor & Kolonsky, 2016).

Memory failure.

To gauge overall memory difficulties in participants over the past 30 days, the 13-item Everyday Memory Questionnaire-Revised (EMQ; Royle & Lincoln, 2007) was administered. Higher scores indicate more memory difficulties.

Insomnia.

The Insomnia Severity Index (Morin, 1993) is a 7-item scale assessing insomnia severity over the last two weeks. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

Procedure

Participants in Study 2 completed self-report survey measures online from remote locations. All methods and procedures were reviewed by the university’s institutional review board (IRB #2018721).

Data Analysis

Face validity (N=474).

Consistent with our pre-registration, we first examined univariate and bivariate associations of the 19 candidate alcohol-induced blackout items (see Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). We then assessed the face validity of those 19 items to determine if participants correctly recognized items as fragmentary or en bloc (see Table 3). The 12 items that participants identified with >70% accuracy (see % correct column in Table 3) were retained for factor analyses, consistent with recommendations to use participants (as opposed to researchers) as raters of face validity (Nevo, 1985; Thomas, Hathaway, & Arheart, 1992).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; n1=237).

Following guidelines by Greene and colleagues (2022), and because the literature suggests that alcohol-induced blackout is best represented by two correlated FB and EB factors2, we specified indicators as ordinal and used CFA with the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator to test the hypothesized factor structure of the 12 items using a random half of the sample (n1=237). We also compared the correlated two-factor model to a one-factor model, given the original ABOM items were represented by a single factor (Miller et al., 2019). We considered a combination of the χ2 test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) fit statistics when evaluating models. We used the following model fit guidelines: CFI and TLI>.95 for reasonably good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999), RMSEA=.08 for adequate fit, and RMSEA=.05 for close fit (MacCallum et al., 1996). We did not use χ2 and its associated p-value to index model fit because it is overly sensitive to factors like sample size, but these are still reported for completeness and transparency. We also report coefficient omega (Ω; Revelle & Zinbarg, 2009), which reflects the proportion of variance in the observed total score attributable to all modeled sources of common variance.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA; n2=237).

We used EFA with goemin rotation in the other half of the sample (n2=237) to perform a more stringent test of our model. We conducted two EFAs: one including the 12 face valid items listed in Table 3 and one including the 12 face valid and 5 ambiguous items listed in Table 3. We used Horn’s parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) and Velicer’s MAP test (Velicer, 1976) to determine the number of factors to retain. The sequencing of exploratory after confirmatory analyses provide a stringent test of our hypothesized confirmatory model (Popper, 1959) by examining how well the same structure can be recovered with no specifications or influences of the data (see Greene et al., 2021). Eleven items were retained for IRT analyses (see results below).

Item Response Theory (IRT; N=474).

A single two-parameter logistic (2PL) model (with responses dichotomized as 0=never and 1=any other response) was used to evaluate item difficulty and discrimination. A single model, in comparison to two separate models for the FB and EB factors, was used to allow direct comparison of all items at once. Graded response polytomous IRT models were then used to evaluate the usefulness of the ordinal response options. Items with redundancy (based on similar 2PL severity thresholds) were removed, resulting in a final set of 8 items.

Final model and validity (N=474).

An additional CFA was estimated in the full sample using the final 8 items. Items were summed to create full scale and subscale scores, consistent with the original ABOM measure (Miller et al., 2019; see Appendix A). External validation analyses, including bivariate and regression analyses, were conducted with the subscale scores to evaluate convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity.3 Specifically, we examined the extent to which FB and EB subscales were associated with hazardous drinking (AUDIT), other alcohol-related consequences (BYAACQ), and drinking motives (DMQ; indicators of convergent validity), as well as with symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7), symptoms of depression (PHQ-9), difficulties with emotion regulation (DERS), and insomnia severity (ISI; indicators of discriminant validity). We then tested the predictive validity of the FB and EB subscales for the convergent validity outcomes (i.e., AUDIT, BYAACQ, DMQ) to determine whether there were differential associations with these outcomes by the EB versus FB subscales. All models controlled for sex (0=assigned female at birth, 1=assigned male at birth), alcohol consumption, other substance use (0=no, 1=yes), and past-30-day memory failure (EMQ).

Results

Descriptive statistics and polychoric correlations for all 19 candidate alcohol-induced blackout items are reported in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Notably, item means were at or below 1 day (range=0.17–1.39) in the past 30 days and the median was zero for all but 5 items, suggesting many participants had not experienced a blackout in the past 30 days.

Face validity.

Face validity was examined for 14 non-ambiguous items (7 fragmentary, 7 en bloc) and 5 ambiguous items. Two of the 14 non-ambiguous items were removed from further analyses due to lack of face validity (items 2 and 9, see Table 3). At least 70% of the sample accurately identified all other non-ambiguous alcohol-induced blackout items as representing either fragmentary (range=70–90% correct) or en bloc blackout (74–88% correct), resulting in a total of 12 face-valid items (6 FB and 6 EB). Two of the 5 ambiguous items were also identified by >70% as representing en bloc blackout (items 17 and 19, see Table 3).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses.

A two-factor CFA fit the 12 face valid alcohol-induced blackout items (χ2=8310; RMSEA=.053; CFI=.996; TLI=.995; Ωfragmentary=.94; Ωen bloc=.91) and was superior to a one-factor model (χ2=210; RMSEA=.113; CFI=.981; TLI=.977; Ω=.96). Standardized factor loadings in the two-factor model were all significant and ranged from .67 to .95 (all SEs < .08). The FB and EB factors were correlated .84. See Supplemental Table 4 for complete statistics.

Exploratory Factor Analyses.

The 12 face valid items were also subjected to EFA. Parallel analysis and the MAP test suggested that there were 2 factors in the data. One-, two-, and three-correlated factor models were extracted to allow comparison of the interpretability of factors (see Supplemental Table 5). The two-factor model best fit the data, with FB and EB factors correlated at .77. As an additional set of exploratory analyses, we conduced EFAs including both face valid and ambiguous items, for a total of 17 items. To be comprehensive, we extracted both 1-factor and 2-factor models (see Supplemental Table 6). Again, parallel analysis and the MAP test suggested that a 2-factor model best fit the data.

Results of EFAs were used to refine the scale. One face valid EB item (item 11) was removed because it cross-loaded (>.3) on the FB factor and another face valid EB item (10) was removed because it loaded <.3 on either factor. We also retained one ambiguous item (item 17, being unable to remember what happened the night before) because (a) it was classified by 81% of participants as EB in face validity analyses and (b) it loaded well (.63) on the EB factor (see Supplemental Table 6). This resulted in a total of 11 items (6 fragmentary, 5 en bloc) for IRT analyses.

Item-Response Theory.

To test the assumptions of IRT, we modeled a single-factor CFA with the remaining 11 items in half of the sample. This model adequately fit the data (χ2=160; RMSEA=.107; CFI=.985; TLI=.981), suggesting IRT analyses are viable for this purpose. Remaining IRT analyses were conducted in the full sample (N=474).

2PL Dichotomous IRT.

The 2PL model indicated that all items demonstrated adequate ability to discriminate between people at different points along the alcohol-induced blackout construct (see Table 4). Items also demonstrated a range of difficulty/severity, which is defined by the point along the alcohol-induced blackout construct at which half the sample is likely to endorse each item. As such, more “severe” items were less frequently endorsed. Items are arranged in order of severity in Table 4. Three items (5, 6, and 13) demonstrated similar severity parameters to other items within the scale; therefore, these items were removed (see Table 4). This resulted in a total of 8 items (4 FB, 4 EB) for the final ABOM-2 scale.

Table 4.

2PL Item Response Theory Estimates for 11 Alcohol-Induced Blackout Items (Full Sample, N=474)

| Short Version of Item | Type | Discrimination | Difficulty/ Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4. fuzzy memories of events | Fragmentary | 4.07 | −0.51 |

| 5. memories that became clear after being reminded | Fragmentary | 3.57 | −0.16 |

| 1. unable to remember a few minutes | Fragmentary | 2.86 | −0.11 |

| 3. reminded about things you had previously forgotten | Fragmentary | 3.50 | 0.11 |

| 6. able to remember a few minutes after being reminded | Fragmentary | 2.68 | 0.13 |

| 7. able to remember a small part of the day after being reminded | Fragmentary | 3.64 | 0.26 |

| 17. unable to remember what happened the night before | Amb/En Bloc | 3.95 | 0.37 |

| 12. unable to remember hours at a time | En Bloc | 3.47 | 0.70 |

| 13. lost several hours of your life with no idea what happened | En Bloc | 3.76 | 0.81 |

| 8. wake up with no idea where you had been or what you had done | En Bloc | 3.06 | 0.83 |

| 14. suddenly realized you have no memory | En Bloc | 2.08 | 1.18 |

Note. Amb=ambiguous item. Difficulty estimates in squares indicate redundancy. Difficulty estimates in bold were those retained from among the redundant items.

Polytomous IRT.

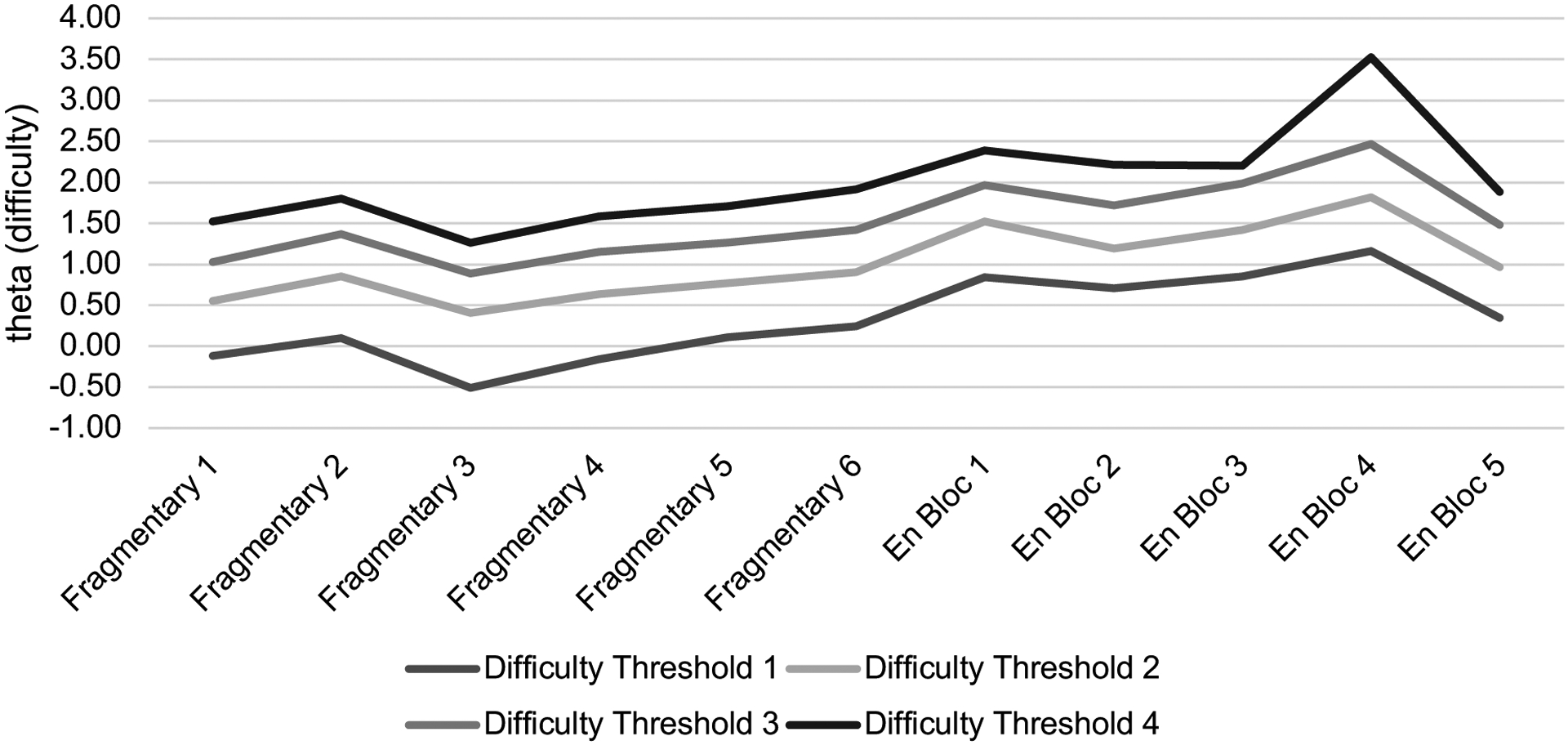

The results of graded-response IRT models are depicted in Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 7. Difficulty thresholds represent the threshold between two response options; for example, “difficulty threshold 1” is equal to the difficulty threshold between a response of 0 (never) and 1 (1 time), “difficulty threshold 2” represents the difficulty threshold between a response of 1 (1 time) and 2 (2 times), etc. As indicated by the non-overlapping lines in Figure 1, results suggested that each ordinal response differentiated between certain points of the alcohol-induced blackout construct and, therefore, are useful to retain.

Figure 1. Graded Response Model Item Threshold Estimates.

Difficulty thresholds represent the threshold between two response options such that “Difficulty Threshold 1” is equal to the difficulty threshold between a response of 0 (never) and 1 (1 time), “Difficulty Threshold 2” represents the difficulty threshold between a response of 1 (1 time) and 2 (2 times), etc. There are four total thresholds for each item because there are 5 possible response options ranging from 0 (Never in the past 30 days) to 4 (4+ times in the past 30 days). Fragmentary 1=unable to remember a few minutes, Fragmentary 2=reminded about things you had previously forgotten, Fragmentary 3=fuzzy memories of events, Fragmentary 4=memories that became clear only after reminded, Fragmentary 5=remember a few minutes after being reminded, Fragmentary 6=remember a small part of the day after being reminded, En Bloc 1=wake up with no idea where you had been, En Bloc 2=unable to remember hours at a time, En Bloc 3=lost several hours of your life, En Bloc 4=suddenly realized you have no memory, En Bloc 5=unable to remember what happened the night before.

Final CFA.

Based on theory and previous research (Goodwin et al., 1969; Hartzler & Fromme, 2003; Wetherill & Fromme, 2016; White, 2003), as well as our own data demonstrating that a two-factor model consistently fit better than a one-factor model, we retained a correlated two-factor model for a final CFA in the full sample (N=474) with 8 items. Model fit was excellent (χ2=8885; RMSEA=.000; CFI=1.00; TLI=1.00; Ωfragmentary=.91; Ωen bloc=.87), and all standardized factor loadings ranged from .76 to .92. The FB and EB factors were correlated .91 (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Final 2-Factor ABOM-2 Model (N=474)

| Fragmentary | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Version of Item | est. std | se | z | pvalue | ci. lower | ci. upper |

| 1. unable to remember a few minutes | 0.87 | 0.02 | 51.66 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.90 |

| 3. reminded about things you had previously forgotten | 0.90 | 0.02 | 57.28 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| 4. fuzzy memories of events | 0.92 | 0.01 | 72.24 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.95 |

| 7. able to remember a small part of the day after being reminded | 0.85 | 0.02 | 42.68 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| En Bloc | ||||||

| est. std | se | z | pvalue | ci. lower | ci. upper | |

| 8. wake up with no idea where you had been | 0.86 | 0.02 | 38.92 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.90 |

| 12. unable to remember hours at a time | 0.87 | 0.02 | 40.66 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.91 |

| 14. suddenly realized you have no memory | 0.76 | 0.04 | 21.72 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.83 |

| 17. unable to remember what happened the night before | 0.92 | 0.02 | 59.63 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

Note. est.std=standardized estimate; se=standard error; z=z-score; ci=95% confidence interval. Fragmentary and en bloc factors r=0.91.

External Validation.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between external validators (BYAACQ, AUDIT, DERS, DMQ, GAD-7, PHQ-9, and ISI) are available in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 8, respectively.

Convergent and discriminant validity.

Bivariate correlations demonstrate positive and significant correlations between ABOM-2 scores and almost all external validators (rs=.10–86; Supplemental Table 8). As hypothesized, ABOM-2 scores were more strongly associated with drinking variables (e.g., alcohol consumption, AUDIT score, alcohol-related consequences; r=.50–.62) than variables less directly related to alcohol use (e.g., symptoms of anxiety or depression, insomnia; r=.12–.21). Contrary to hypotheses, conformity motives had the lowest correlation with the FB [r=.08, ns] and EB [r=.11, p<.05] subscales compared to other external validators, whereas coping and enhancement motives had middling associations with the FB [rs=.34–.35, p<.05] and EB [r=.29–.35, p<.05] subscales compared to other external validators.

Predictive validity.

The ABOM-2 FB and EB subscales demonstrated differential validity in predicting AUDIT scores, alcohol-related consequences, and drinking motives (see Table 6) in a relatively stringent test controlling for memory. Consistent with expectations, the EB score was more strongly associated with AUDIT score and coping and conformity motives. Contrary to expectations, FB score was more strongly associated with number of alcohol-related consequences and drinking for enhancement.

Table 6.

Predictive validity of the ABOM-2 (N=474)

| Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDIT | BYAACQ | DMQ-Soc | DMQ-Cop | DMQ-Enh | DMQ-Con | ||

| Predictors | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Male sex | 0.01 (0.35) | −0.06 (0.36) | −0.08 (0.56) | −0.05 (0.41) | −0.01 (0.51) | −0.07 (0.33) | |

| Alcohol use | 0.47 (0.03) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.22 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.03) | |

| Substance use | 0.02 (0.33) | 0.09 (0.34) | 0.06 (0.52) | 0.04 (0.38) | 0.09 (0.48) | 0.00 (0.30) | |

| Memory | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.01) | |

| Fragmentary | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.07 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.08) | −0.11 (0.05) | |

| En bloc | 0.22 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.06 (0.13) | 0.14 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.08) | |

Note. Significant standardized estimates (p<.05) depicted in bold. AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, excluding item 8 (blackout). DMQ=Drinking Motives Questionnaire. Soc=social. Cop=coping. Enh=enhancement. Con=conformity. GAD-7=Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire-9. DERS=Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. ISI=Insomnia Severity Index. SE=standard error.

Discussion

Young adults and individuals with AUD consistently report two different types of alcohol-induced blackout (Goodwin et al., 1969; Hartzler & Fromme, 2003a; Miller, et. al., 2018), but these cannot be rigorously evaluated in research because validated measures of FB and EB do not exist. This study developed and validated the ABOM-2, an 8-item measure of alcohol-induced blackouts that includes FB and EB subscales. Our hypothesis that a correlated two-factor alcohol-induced blackout model would be superior to a unidimensional model was supported, and there is preliminary support to suggest that EB and FB subscales have differential associations with related outcomes.

A major strength of this project was the use of cognitive interviewing to refine the item set prior to measure development. This is key for ensuring participants understand the items as intended, but is typically overlooked (Boness & Sher, 2020). Study 1 allowed us to identify problematic items that needed refinement prior to a larger-scale data collection, evaluate the appropriateness of our response scale, and identify common challenges among the items. We were then able to answer some of these questions empirically (e.g., whether the response scale discriminates along different points on the alcohol-induced blackout construct).

Validation of a two-factor alcohol-induced blackout model and the resulting ABOM-2 subscales is also a major advantage over other alcohol-induced blackout items and measures. The ability to assess EB and FB validly and reliably is key for identifying differential predictors of alcohol-related outcomes in future studies. In this study, EB and FB did have differential associations with outcomes of interest, but not always in the hypothesized direction. Specifically, EB was more strongly associated with hazardous drinking (AUDIT), but FB was more strongly associated with number of alcohol-related consequences (BYAACQ). Similarly, EB was associated with coping and conformity drinking motives, while FB was associated with enhancement motives. This pattern of results seems to indicate that EB is more strongly associated with potentially problematic motives for drinking (conformity and coping) and risk for hazardous alcohol use (as indicated by the AUDIT), while FB is more strongly associated with drinking in response to positive emotions (enhancement motives) and a broader range of potentially less severe consequences of drinking (e.g., doing embarrassing things or having a hangover). This is consistent with conceptualizations of EB as the more severe and potentially harmful of the two types of alcohol-induced blackout (Miller et al., 2018). This distinction is expected to help identify opportunities to connect young adults at risk for adverse neurobiological outcomes with appropriate interventions (e.g., Acuff et al., 2019). This, in turn, may reduce alcohol-related consequences and associated medical costs (Mundt & Zakletskaia, 2012). However, given the preliminary nature of these analyses, additional research is needed to determine if this differential pattern is replicated and/or evident over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was not without limitations. First, the COVID-19 pandemic began part way through Study 1 and continued for the duration of the project. As demonstrated in Table 1, there were some significant consumption-related differences between Rounds 2 and 3 of the cognitive interviews, at which point many students had left campus and experienced residential changes (e.g., moving home) that may have resulted in decreased drinking (Acuff et al., 2021; White et al., 2020). We do not view this as a significant limitation because participants had to screen positive for heavy drinking to participate, and the goal of this study was not to assess change in drinking or alcohol-induced blackout. However, this may have impacted the past-30-day prevalence of blackout in this sample. The 30-day timeframe for the measure was chosen so that the ABOM-2 can be used as an outcome measure in prevention and intervention trials that often include 30-day follow-ups. The relatively short timeframe is also expected to minimize recall bias and may be ideal for screening and referral. Specifically, alcohol-induced blackout seems to enhance motivation to decrease drinking (Fairlie, Ramirez, Patrick, & Lee, 2016; Marino & Fromme, 2018), in which case recent blackout experience may be an appropriate prompt for brief intervention referral. However, as a result of the short follow-up, the ABOM-2 does not characterize broader (e.g., past-year, lifetime) experience with blackouts that may be more relevant for lighter-drinking samples. Future investigations may determine whether the timeframe can be extended beyond 30 days. Alternatively, measures with longer assessment windows (e.g., AUDIT) may be preferable for lighter-drinking samples. We were also unable to evaluate the stability of the ABOM-2 (e.g., test-retest reliability) or to test the final measure in an independent sample, which may be a focus of future work.

Another significant challenge to validity when studying alcohol-induced blackout experiences is related to memory. Because alcohol-induced blackout is characterized by some degree of memory loss, it is difficult to know how accurately participants can report on these experiences. In many cases, realizing an alcohol-induced blackout occurred may be dependent upon information from others. In the absence of such information, it is possible that participants fail to identify an alcohol-induced blackout occurred, particularly FBs. For this reason, future research might consider the inclusion of informants, such as drinking partners, to validate participant responses to alcohol-induced blackout items.

Constraints on generality.

Although the demographics of our samples are largely consistent with the demographics of the university where this research was conducted, the lack of diversity may impact generalizability. For example, samples in both studies were largely White and non-Hispanic. Although samples were relatively evenly split between biological sex and gender, transgender or gender-queer participants were not well represented. Thus, our findings may not generalize beyond participants outside of undergraduate college students and the majority groups reported. We consider this a significant limitation for the cognitive interviews, given the interpretation of self-report items is likely contextually-embedded and therefore dependent upon features such as one’s culture or primary language (Knowles & Condon, 2000). Thus, it is possible that our items are more appropriate for some subgroups than others and that these items need additional refinement in more racially, ethnically, and gender-diverse participants. Although alcohol-induced blackouts are most prevalent among young adults, it would also be useful to validate the ABOM-2 in samples with a broader age range.

These studies fill a gap in the literature by carefully developing and validating a measure of alcohol-induced blackout that includes both FB and EB subscales (ABOM-2). This measure improves upon previous alcohol-related blackout assessments, which traditionally include a single item or a unidimensional set of items, allowing for more precision in the assessment of alcohol-related blackouts. Improved assessment of alcohol-induced blackouts will help better identify young adults at risk for alcohol-related harm and increase the likelihood that they are connected with appropriate interventions.

Supplementary Material

Public significance statement:

Alcohol-induced blackouts are associated with a range of negative consequences, particularly among young adults. This manuscript offers an updated measure of blackouts that utilizes a range of research methods to increase the likelihood that young adults experiencing blackouts are accurately identified.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by a Student Research Fellowship from the American Psychological Association’s Division 12, Section IX (Assessment). Investigator effort was supported in part by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA026177, Principal Investigator: Cassandra L. Boness; K23AA026895, PI Miller; R21AA025175, PI Miller). Funding sources had no involvement in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript. Authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Nicole A. Hall to the early stages of data collection for this project.

Footnotes

Materials for this study are available at https://osf.io/gnfu4/ and data is available by emailing the corresponding author.

Heavy drinking was defined as (a) having 5 or more (males) or 4 or more (females) drinks containing any kind of alcohol on a single occasion OR (b) drinking more than 14 drinks (males), or more than 7 drinks (females) in a week (NIAAA, 2003).

A model with a higher order blackout factor and two lower order FB and EB factors may be more conceptually appropriate here, although statistically equivalent. To remain consistent with our pre-registration, we test at correlated two-factor model but wish to note that the data was equally well represented by a higher order model.

This reflects a deviation from the pre-registration, where we noted we would test incremental validity over the original ABOM. Incremental validity over the original ABOM was limited. We chose to prioritize reporting of predictive validity here because (a) the mixed methods used to refine the item set are sufficient to justify use of user-refined items over researcher-generated items in the original ABOM and (b) emergence of FB and EB subscales gives us the opportunity to determine if FB and EB differentially predict relevant outcomes.

References

- Acuff SF, Strickland JC, Tucker JA and Murphy JG, 2022. Changes in alcohol use during COVID-19 and associations with contextual and individual difference variables: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(1), p.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Voss AT, Dennhardt AA, Borsari B, Martens MP and Murphy JG, 2019. Brief motivational interventions are associated with reductions in alcohol‐induced blackouts among heavy drinking college students. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research, 43(5), pp.988–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB and Monteiro MG, 2001. The alcohol use disorders identification test (pp. 1–37). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Fingeret A and Kahler CW, 2014. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), pp.103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K and Lennox R, 1991. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological bulletin, 110(2), p.305. [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL and Sher KJ, 2020. The case for cognitive interviewing in survey item validation: a useful approach for improving the measurement and assessment of substance use disorders. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 81(4), pp.401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Lane SP and Sher KJ, 2016. Assessment of withdrawal and hangover is confounded in the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule: Withdrawal prevalence is likely inflated. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(8), pp.1691–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Watts AL, Moeller KN and Sher KJ, 2021. The etiologic, theory-based, ontogenetic hierarchical framework of alcohol use disorder: A translational systematic review of reviews. Psychological Bulletin, 147(10), p.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd-Bredbenner C, Eck K and Quick V, 2021. GAD-7, GAD-2, and GAD-mini: Psychometric properties and norms of university students in the United States. General hospital psychiatry, 69, pp.61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB and Correia CJ, 1997. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(1), pp.100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T and Martin CS, 2005. What were they thinking?: Adolescents’ interpretations of DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptom queries and implications for diagnostic validity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 80(2), pp.191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, 1994. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological assessment, 6(2), p.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ and Meehl PE, 1955. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological bulletin, 52(4), p.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie AM, Ramirez JJ, Patrick ME and Lee CM, 2016. When do college students have less favorable views of drinking? Evaluations of alcohol experiences and positive and negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), p.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Barry KL and Macdonald R, 1991. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. International Journal of the Addictions, 26(11), pp.1173–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Crane JB and Guze SB, 1969. Phenomenological aspects of the alcoholic “blackout”. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 115(526), pp.1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL and Roemer L, 2004. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 26(1), pp.41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Greene AL, Watts AL, Forbes MK, Kotov R, Krueger RF and Eaton NR, 2022. Misbegotten methodologies and forgotten lessons from Tom Swift’s electric factor analysis machine: A demonstration with competing structural models of psychopathology. Psychological Methods. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B and Fromme K, 2003b. Fragmentary blackouts: Their etiology and effect on alcohol expectancies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(4), pp.628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J, Tobias-Webb J, De Regt T, Dore G, Juckes L, Latt N and Hickie IB, 2013. Pathways to alcohol-induced brain impairment in young people: a review. Cortex, 49(1), pp.3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, 1965. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), pp.179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Simons‐Morton B and White A, 2016. Alcohol‐induced blackouts as predictors of other drinking related harms among emerging young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(4), pp.776–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT and Bentler PM, 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), pp.1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC and Sher KJ, 1992. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41(2), pp.49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek EM, 1946. Phases in the drinking history of alcoholics. Analysis of a survey conducted by the official organ of Alcoholics Anonymous (Memoirs of the Section of Studies on Alcohol). Quarterly journal of studies on alcohol, 7(1), pp.1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM and Johnson KA, 1994. Drinking-induced blackouts among young adults: Results from a national longitudinal study. International journal of the addictions, 29(1), pp.23–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR and Borsari B, 2008. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 69(4), pp.611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR and Read JP, 2005. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(7), pp.1180–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keum BT, Miller MJ and Inkelas KK, 2018. Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the PHQ-9 across racially diverse US college students. Psychological assessment, 30(8), p.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles ES and Condon CA, 2000. Does the rose still smell as sweet? Item variability across test forms and revisions. Psychological Assessment, 12(3), p.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotailo PK, Egan J, Gangnon R, Brown D, Mundt M and Fleming M, 2004. Validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test in college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(6), pp.914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labhart F, Livingston M, Engels R and Kuntsche E, 2018. After how many drinks does someone experience acute consequences—determining thresholds for binge drinking based on two event‐level studies. Addiction, 113(12), pp.2235–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Roh S and Kim DJ, 2009. Alcohol-induced blackout. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(11), pp.2783–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW and Sugawara HM, 1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological methods, 1(2), p.130. [Google Scholar]

- Marino EN and Fromme K, 2015. Alcohol-induced blackouts and maternal family history of problematic alcohol use. Addictive behaviors, 45, pp.201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino EN and Fromme K, 2018. Alcohol-induced blackouts, subjective intoxication, and motivation to decrease drinking: Prospective examination of the transition out of college. Addictive behaviors, 80, pp.89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Ferreira JA, Haase RF, Martins J and Coelho M, 2016. Validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised across US and Portuguese college students. Addictive behaviors, 60, pp.58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Treloar H, Fernandez AC, Monnig MA, Jackson KM and Barnett NP, 2016. Latent growth classes of alcohol-related blackouts over the first 2 years of college. Psychology of addictive behaviors, 30(8), p.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Merrill JE, DiBello AM and Carey KB, 2018. Distinctions in alcohol‐induced memory impairment: A mixed methods study of en bloc versus fragmentary blackouts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(10), pp.2000–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, DiBello AM, Merrill JE and Carey KB, 2019. Development and initial validation of the alcohol-induced blackout measure. Addictive behaviors, 99, p.106079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, 1993. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. Guilford press. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt MP and Zakletskaia LI, 2012. Prevention for college students who suffer alcohol-induced blackouts could deter high-cost emergency department visits. Health Affairs, 31(4), pp.863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Council Task Force on Recommended Alcohol Questions. 2003. Recommended alcohol questions. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Fu Q, Knopik V, Lynskey MT, Whitfield JB, Statham DJ and Martin NG, 2004. Genetic epidemiology of alcohol-induced blackouts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(3), pp.257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo B, 1985. Face validity revisited. Journal of Educational Measurement, 22(4), pp.287–293. [Google Scholar]