Abstract

Background:

Rates of alcohol use disorders in individuals with bipolar disorder are 3 to 5 times greater than in the general population and exceed rates of alcohol use disorders reported in other affective and anxiety disorders. Despite this high rate of comorbidity, our understanding of the psychosocial and neural mechanisms that underlie the initiation of alcohol misuse in young adults with bipolar disorder remains limited. Prior work suggests that individuals with bipolar disorder may misuse alcohol as a coping mechanism, yet the neural correlates of coping drinking motives and associated alcohol use have not been previously investigated in this population.

Methods:

Forty-eight young adults (22 bipolar disorder type I, 26 typically developing; 71% women; average age ± standard deviation = 22 ± 2 years) completed the Drinking Motives and Daily Drinking Questionnaires, and a Continuous Performance Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Task with Emotional and Neutral Distracters. We calculated the relative difference in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functional coupling with the anterior insula and amygdala in response to emotional distracters compared with neutral stimuli and investigated the relations with coping drinking motives and alcohol use.

Results:

Across all participants, coping drinking motives were associated with greater quantity of recent alcohol use. In individuals with bipolar disorder, greater ACC-anterior insula functional coupling was associated with greater coping drinking motives, and greater quantity and frequency of recent alcohol use. The relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling was not associated with coping drinking motives or alcohol use in the typically developing group. Greater ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in individuals with bipolar disorder was also associated with greater anxiety symptoms and recent perceived psychological stress. Exploratory analyses suggest that the relations between ACC-anterior insula functional coupling and coping drinking motives may be confounded by anticonvulsant use.

Conclusion:

Results suggest that a difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling during emotion processing may underlie alcohol use as a maladaptive coping mechanism in young adults with bipolar disorder.

Keywords: drinking motives, bipolar disorder, alcohol drinking, anterior cingulate cortex, anterior insula

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are highly prevalent in individuals with bipolar disorder (Di Florio et al., 2014, Scavone et al., 2018) with up to a 60% co-occurrence rate (Regier et al., 1990). The rate of AUDs in bipolar disorder exceeds those observed in the general population (Regier et al., 1990) and other affective and anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 1996). Despite this high comorbidity rate, our understanding of the neural and psychosocial mechanisms underlying alcohol misuse in young adults with bipolar disorder remains limited. Using alcohol as a maladaptive coping strategy may represent one mechanism that contributes to greater alcohol misuse in this population. Self-medication with drugs or alcohol has been reported as a motive in up to 93% of individuals with bipolar disorder (Weiss et al., 2004), and national epidemiological data in the United States indicate that bipolar I disorder has the highest rates of reported self-medication with drugs and alcohol (41%) among all mood disorders (Bolton et al., 2009). While the self-medication hypothesis is debated (Strakowski and DelBello, 2000)—and alcohol use does not effectively “treat” underlying bipolar disorder pathology—alleviation of affective symptoms is one of the most commonly cited reasons for alcohol misuse in this population (McDonald and Meyer, 2011). Using alcohol to cope with negative affect has been reported in psychiatric groups, including bipolar disorder, with a history of alcohol or drug use treatment (Carey and Carey, 1995); however the neural correlates of coping drinking motives and associated alcohol use patterns have not been previously investigated in young adults with bipolar disorder. Understanding these factors could improve existing treatment approaches and help develop novel interventions to decrease the rate of alcohol misuse initiation prior to the development of addiction in those with bipolar disorder.

Affect dysregulation is a key characteristic of bipolar disorder. Variations in the structure, function, and connectivity of anterior limbic and paralimbic regions in the brain have been implicated in both alcohol misuse and affect dysregulation. Specifically, studies have shown differences in the structural morphology and reactivity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula, and amygdala, may be associated with the development, or be a consequence, of problematic drinking in typically developing individuals (Cheetham et al., 2014, Elsayed et al., 2018, Gorka et al., 2020, Wrase et al., 2008, Mashhoon et al., 2014). Alterations in structure, function, and connectivity of anterior limbic and paralimbic regions are consistently reported in bipolar disorder (Chase and Phillips, 2016, Phillips and Swartz, 2014). Specifically, an increase in functional connectivity between the ACC and insula (Ellard et al., 2019) and a loss of functional connectivity between the ACC and amygdala (Wang et al., 2009) during negative emotion processing has been reported in adults with bipolar disorder. Alterations in anterior limbic and paralimbic regions are thought to contribute to affect dysregulation and risk for developing alcohol use problems (Lippard et al., 2017, Lippard et al., 2020, Chase and Phillips, 2016). In bipolar disorder, neurochemical variations in anterior limbic and paralimbic networks have been associated with alcohol dependence in adults (Nery et al., 2010, Prisciandaro et al., 2017) and risky drinking patterns in youth (Chitty et al., 2013). Structural differences in limbic and paralimbic networks have also been associated with prospective development of problematic drinking in youth with bipolar disorder (Lippard et al., 2017). Variation in top-down modulation of limbic and paralimbic systems in bipolar disorder, and associated affect dysregulation, may moderate (i.e., enhance or attenuate) the endorsement of coping drinking motives and associated alcohol use in young adults with bipolar disorder, particularly during exposure to negative affective stimuli. Indeed, relations between variation in function of the insula and greater endorsement of coping drinking motives have been reported in young adults with and without alcohol use disorders (Gorka et al., 2020). It is unclear if variation in anterior limbic and paralimbic systems relate to drinking motives in bipolar disorder.

The Current Study

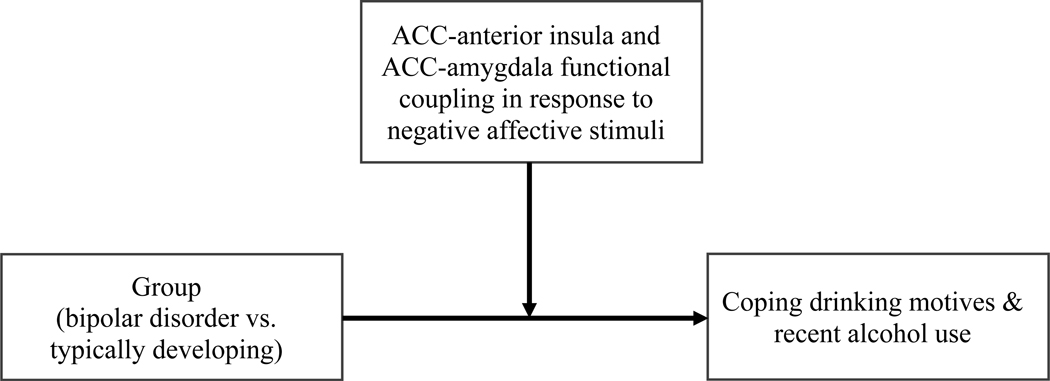

The current study investigated coping drinking motives, alcohol use, and their relations to relative difference in functional coupling among ACC, amygdala, and anterior insula during negative emotion processing in young adults with bipolar I disorder compared to typically developing young adults. Participants completed the Continuous Performance fMRI Task with Emotional and Neutral Distracters (CPT-END). We used the CPT-END as our paradigm of interest as it elicits responses in anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and amygdala, including changes in functional coupling among ROIs during emotion processing (Strawn et al., 2016, Lippard et al., 2020). We hypothesized the way the brain responds to negative affective stimuli in individuals with bipolar disorder may moderate the degree to which they endorse using alcohol to cope and, therefore, their overall alcohol use patterns (see Figure 1). Specifically, we predicted young adults with bipolar disorder would endorse greater coping drinking motives as a cause for drinking compared to typically developing young adults. We also hypothesized that greater coping drinking motives in bipolar disorder would be associated with a loss of functional coupling between ACC and amygdala and conversely an increase in functional coupling between ACC and anterior insula in response to emotional relative to neutral stimuli. To test these hypotheses, relations among coping drinking motives, relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling to negative emotional stimuli (compared to neutral stimuli), and recent alcohol use, were examined across all participants. Interactions with group were investigated. Additionally, we explored how relative difference in functional coupling among ROIs associated with coping drinking motives, relate to depression and anxiety symptoms and recent perceived psychological stress in young adults with bipolar disorder. These exploratory analyses were conducted to examine clinical features that may relate to variation in ACC-ROI functional coupling during emotion processing. Additional sensitivity and exploratory analyses were conducted examining relations with impulsivity (Supporting Information 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed causal model depicting hypothesized relations among neural processing of negative affective stimuli, coping drinking motives, and alcohol use in young adults with bipolar I disorder.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Participants

Participants between the ages of 18 to 25 were recruited using flyers and word-of-mouth on the University of Texas at Austin campus and mental health clinics in the surrounding area. Participants completed a phone screen to assess eligibility prior to study participation. The study sample consisted of 48 young adults (22 with bipolar I disorder and 26 typically developing; see Table 1). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Research Version (SCID-5-RV)(First et al., 2015) was used to confirm all diagnoses, including bipolar I disorder, alcohol/substance use disorders (A/SUDs) and anxiety disorders. Mood symptoms were determined using the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories (BDI, BAI respectively) (Beck et al., 1988, Beck et al., 1961) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978). Full-scale intelligence quotient-2 subtests (FSIQ-2) was measured for each participant using the verbal comprehension and matrix reasoning subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition (WASI-II). The University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and written consent was obtained from all participants. Additionally, all participants were financially compensated for their participation.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Factors Stratified by Group

| Bipolar disorder (N=22) | Typically developing (N=26) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Demographics | Mean Age (SD) | 22 (2) | 21 (2) | 0.33 |

| Number of Females (%) | 16 (73) | 18 (69) | 1.00 | |

| Mean WASI-II FSIQ-21 (SD) | 118 (10) | 118 (13) | 0.87 | |

| Caucasian/White (%) | 8 (36) | 12 (46) | 0.70 | |

| Hispanic/Latino (%) | 7 (32) | 7 (27) | 0.96 | |

| African/ African American/ Black (%) |

2 (9) | 0 | 0.20 F | |

| Asian (%) | 2 (9) | 4 (15) | 0.67 F | |

| Mixed Race (%) | 3 (14) | 3 (12) | 1.00 F | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical Factors | Mood Symptoms: | |||

| Mean BDI Score (SD) | 14 (8) | 3 (4) | < 0.001 W | |

| Mean BAI Score (SD) | 11 (7) | 4 (5) | 0.001 W | |

| YMRS Score (SD) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.82 W | |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol/Substance Use Disorder Comorbidities | Current Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) 2 | |||

| AUD mild (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| AUD moderate (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

| AUD severe (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

|

| ||||

| Past Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) | ||||

| AUD mild (%) | 3 (14) | 0 | 0.09 F | |

|

| ||||

| Current Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) | ||||

| Cannabis Use Disorder, mild (%) | 4 (18) | 1 (4) | 0.16 F | |

| Cannabis Use Disorder, moderate (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

|

| ||||

| Past Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) | ||||

| Cannabis Use Disorder, mild (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| Cannabis Use Disorder, severe (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| Stimulant Use Disorder, severe (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| Sedative Use Disorder, mild (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| Sedative Use Disorder, moderate (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

|

| ||||

| Urine toxicology screen | Tetrahydrocannabinol (%) | 7 (32) | 5 (19) | 0.50 |

| Amphetamines (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

| Methamphetamines (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

| Benzodiazepines (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

| Phencyclidines (%) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.46 F | |

|

| ||||

| Other Clinical | Rapid Cycling (%)3 | 6 (27) | - | - |

| Factors and Comorbidities | Lifetime Psychotic Symptoms (%) | 11 (50) | - | - |

| Lifetime Suicide Attempt (%) | 8 (36) | - | - | |

| Co-occurring Anxiety Disorders (%)4 | 8 (36) | - | - | |

|

| ||||

| Psychiatric Medications | Unmedicated at scan (%) | 6 (27) | - | - |

| Antipsychotic (%) | 8 (36) | - | - | |

| Anticonvulsant (%) | 5 (23) | - | - | |

| Antidepressant / SSRIs (%) | 4 (18) | - | - | |

| Stimulant (%) | 1 (5) | - | - | |

| Lithium (%) | 9 (41) | - | - | |

| Anxiolytics (%) | 2 (9) | - | - | |

| Sedatives/Antihistamines (%) | 6 (27) | - | - | |

|

| ||||

| Handedness | Right (%) | 20 (91) | 24 (92) | 1.00 F |

| Left (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

| Ambidextrous (primary right) (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 1.00 F | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking Status | Current nicotine use (%) | 7 (32) | 1 (4) | 0.02 F |

Note: Between-group (bipolar disorder vs. typically developing) differences in full scale intelligence quotient-2 subtests (FSIQ-2) and age were compared using a two-sample t-test. All other factors were examined with a Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon Test, or Fisher Exact tests where appropriate. Rapid cycling, lifetime psychotic symptoms, lifetime suicide attempt, comorbid anxiety disorders, and psychiatric medications were considered an exclusion criterion, and thus not present, in the typically developing group. Superscript letter “W” represents p-value calculated with a Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon Test. Superscript letter “F” represents p-value calculated with Fisher exact test. Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; SD, standard deviation; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition (WASI-II) was used to obtain FSIQ-2 which represents the composite score for the full-scale intelligence quotient comprising verbal comprehension and matrix reasoning subtests.

Refers to AUDs in the past 12 months.

Rapid Cycling reflects past-year rapid cycling in participants with bipolar disorder.

Comorbid anxiety disorders included generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety. Two of these individuals screened for an anxiety disorder but we were unable to complete the anxiety module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5-Research Version.

Participants were assessed for the following exclusion criteria: pregnancy, IQ<85, history of major medical illness with possible neurological or central nervous system effects, or any medical condition preventing participation in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Unlike many studies, participants were not excluded by the presence of AUDs or other substance use disorders since these factors were being investigated. Participants were assessed for possible pregnancy and substance use on the day of scan via urinalysis. All participants were asked to abstain from any drug or alcohol use for 24-hours preceding the functional MRI scan.

Measures

Drinking Motives

Drinking motives were assessed using the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R) (Cooper, 1994). The DMQ-R is a 20-item, four-factor, self-report questionnaire with response options ranging from 1 (Never/Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always/Always). Scores from individual items are summed to derive four subscale scores for coping, social, enhancement, and conformity drinking motives. Given our interest in the neural correlates of alcohol use as a maladaptive coping mechanism, this manuscript focuses on coping drinking motives. Items that comprised the coping drinking motives factor included drinking alcohol to forget about worries, to help with feelings of depression or nervousness, to cheer up when in a bad mood, to feel more self-confident and surer of oneself, and to forget about problems.

Alcohol Use

Total quantity and frequency of prior month’s alcohol use was assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) (Collins et al., 1985). Participants were asked to think of a typical week during the last 30 days and report the total number of standard drinks they typically consumed during each of the seven days of that week. To assess for age of alcohol use initiation, participants answered a stand-alone question asking the age of first full drink, not just a sip from an adult’s glass and not including drinking as part of religious ceremonies.

Recent Perceived Stress

Recent perceived psychological stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS is a 10-item self-report measure, which measures the degree to which participants appraise life situations in the previous 30 days as stressful (Cohen et al., 1983). Response options range from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very Often). Items include statements such as “felt that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do,” “been able to control irritations in your life” and “been upset because of something that had happened unexpectedly.” Scores from individual items are summed to derive a total score of recent perceived stress.

Impulsivity

All participants completed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) as a measure of trait-level impulsivity (Patton et al., 1995). The BIS-11 is a 30-item self-report questionnaire, with response options ranging from 1 (Rarely/Never) to 4 (Almost Always/Always). Scores from individual items can be summed to derive three subscale scores for motor, cognitive-attention, and non-planning impulsivity. Items were summed to derive a total impulsivity score.

Image Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis

MRI Acquisition

A three-dimensional gradient echo (MPRAGE) T1-weighted sequence with a 32-channel head coil was used on a 3-Tesla Siemens Skyra (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) to obtain all high-resolution sagittal structural MRI images. The following parameters were used: echo time (TE)=2.42ms, repetition time (TR)=1900ms, field of view=220×220mm2, matrix=224×224, 192 one-mm slices without gap and one average. A single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence was used to acquire all functional MRI data, aligned with the anterior-posterior commissure plane with multiband factor of 3, TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, matrix=128×128, field of view=220 × 220mm2, and 72 two-mm slices without gap.

Continuous Performance Task with Emotional and Neutral Distracters (CPT-END)

During fMRI acquisition, participants completed a Continuous Performance task with Emotional and Neutral Distracters (CPT-END). This task is a visual oddball paradigm in which participants are presented a series of standard images. Seventy percent of the stimuli are squares, 10% are circles (targets), 10% are emotionally neutral pictures, and 10% are emotionally unpleasant pictures (emotional distracters). Circles, neutral, and emotional pictures are presented at random. Emotional and neutral distracters were images taken from the International Affective Pictures Set (IAPS; University of Florida) (Yamasaki et al., 2002). Emotional distracters are unpleasant human scenes, and neutral distracters are ordinary activities. All distracters are chosen based on normative ratings of arousal (1-low, 9=high) and valence (1=negative, 9=positive). Participants are asked to press “2” on the button box whenever they see the target (circles) and “1” for all other stimuli (squares, emotional and neutral distracters). Imaging sessions consist of 2 runs of 158 stimuli presented for 2 seconds at 3 second intervals. A fixation cross is presented for 1 second between images.

Functional Coupling Preprocessing

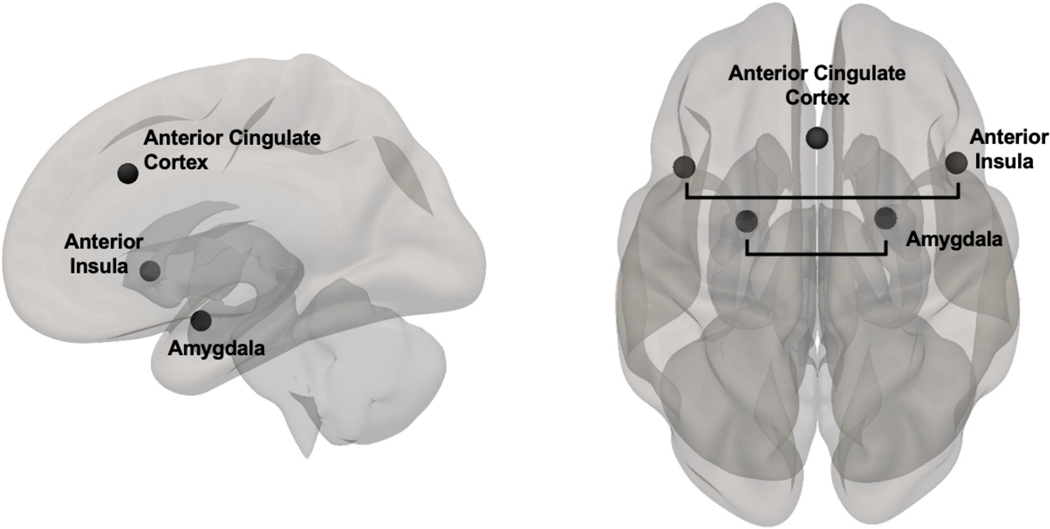

All functional images were preprocessed in SPM12 through the CONN toolbox (version 20.b; www.nitrc.org/projects/conn) (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012) using a previously described preprocessing utility (Ismaylova et al., 2018, Pressl et al., 2019). Details of the CONN preprocessing procedures are included in Supporting Information 2. A priori ROIs included bilateral ACC, anterior insula, and amygdala (see Figure 2). ACC (MNI center coordinates: [x = 0, y = 22, z = 35]) and left and right anterior insula, (MNI right center coordinates: [x = 47, y = 14, z = 0]; MNI left center coordinates: [x = −44, y = 13, z = 1]) were anatomically defined from a predefined network atlas in CONN and were originally derived from an independent component analysis (ICA) based on the Human Connectome Project (HCP) dataset of 497 subjects (Whitfield-Gabrieli & Nieto-Castanon, 2012). Bilateral amygdala ROIs were defined from the FSL Harvard-Oxford Atlas in CONN. An ROI-to-ROI bivariate correlation was conducted using CONN. This approach uses the CompCor method to reduce noise in the BOLD signal (Behzadi et al., 2007). Functional coupling in response to emotional, neutral, and target (i.e., circle) stimuli compared to squares were modeled at the first level in CONN using the weighted General Linear Model for weighted correlation (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). Fisher-transformed correlation coefficients between each pair of ROIs for emotional, neutral, and target stimuli were extracted. Relative difference in functional coupling between each ACC-ROI pair for emotional minus neutral stimuli was calculated for subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

Lateral and superior view of the a priori regions of interest (ROIs), including anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and bilateral anterior insula and amygdala. ACC [MNI center coordinates: (x=0, y=22, z=35] and left and right anterior insula [MNI right center coordinates: (x=47, y=14, z=0); MNI left center coordinates: (x=−44, y=13, z=1)] were defined from a pre-defined network atlas in CONN and were originally derived from an independent component analysis (ICA) based on the Human Connectome Project (HCP) dataset of 497 subjects (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). Bilateral amygdala ROIs were defined from the FSL Harvard-Oxford Atlas in CONN.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.4.2 (https://www.r-project.org/about.html). Analyses included a combination of multiple linear regression and mixed modelling. Distributions of residuals from each primary model were inspected and any non-normally distributed outcome variables were logarithmically transformed.

Between-group Differences in Demographic and Clinical Factors, Drinking Motives, Alcohol Use, Perceived Stress, Age of Alcohol Initiation, Impulsivity, CPT-END Behavior

Between-group differences in demographic and clinical factors, coping drinking motives, recent alcohol use, recent perceived stress, and age of alcohol initiation were examined using t-tests, Chi-square, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests (for non-normally distributed variables; Shapiro Wilke test, p<.05), and Fisher’s exact as appropriate. We also explored between group differences in other drinking motives on the DMQ-R to explore if groups differed on non-coping drinking motives, as well as BIS-11 total impulsivity scores. Finally, between-group t-tests and Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests were also used to assess between-group differences in average number of incorrect responses and average number of non-responses to all stimuli on the CPT-END task. Between-group difference in average reaction time to emotional compared to neutral stimuli (reaction time to emotional minus neutral stimuli), reaction time to target (circle) stimuli, as well as average number of non-responses to emotional compared to neutral stimuli (average non-responses to emotional minus neutral stimuli) were also investigated. All findings were considered significant at alpha ≤.05.

Covariates

All of the following analytic models controlled for sex to account for the fact that total quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption is typically higher in men than in women (Kanny et al., 2018) and sex-differences may also contribute to alcohol-related problems in bipolar disorder (Lippard et al., 2017). Similarly, sex differences have been reported in the endorsement of coping drinking motives (Foster et al., 2014, Peltier et al., 2019), depression and anxiety (Bangasser and Cuarenta, 2021), and perceived stress (Graves et al., 2021). Finally, sex differences have also been found in functional connectivity patterns across limbic and paralimbic neural network (Moriguchi et al., 2014, Weis et al., 2020). Earlier age of alcohol use onset has also been associated with heavier alcohol use (Buchmann et al., 2009) and may be associated with coping drinking motives (Buchmann et al., 2010) in youth. Consequently, we also controlled for age of alcohol initiation when examining relations with alcohol-related outcome variables, including coping drinking motives and recent alcohol use.

Associations Between Coping Drinking Motives and Recent Alcohol Use

Multiple linear regression was performed with coping drinking motives, group (bipolar disorder, typically developing), and their interaction as predictor variables, and total drinks per typical week in the past 30 days as the dependent variable, controlling for sex and age of alcohol initiation. A parallel model was conducted with total drinking days per typical week in the past 30 days as the dependent variable. Findings were considered significant at alpha ≤.025 (Bonferroni correction for two drinking variables).

Coping Drinking Motives, Recent Alcohol Use, and Relative Difference in Functional Coupling Between Regions of Interest

Linear mixed models were used with relative difference in functional coupling between ACC and anterior insula (calculated as emotional minus neutral stimuli), group, and group by relative difference in functional coupling by hemisphere interaction as between-subjects variables. Hemisphere of anterior insula ROI (left, right) was modeled as the repeated within-subjects variable, and coping drinking motives as the dependent variable, controlling for sex and age of alcohol use initiation. The same analysis was completed with relative difference in ACC-amygdala functional coupling as the between-subjects variable. If there were no interactions with hemisphere, the models were repeated after removing interaction with hemisphere from the model. Findings were considered significant at alpha ≤.025 (corrected for two a priori ROI functional coupling pairs [relative difference in ACC-anterior insula and relative difference in ACC-amygdala functional coupling]). We repeated these models with functional coupling between ACC and ROIs in response to targets as the between-subjects variable to explore specificity of neural responses during negative affect and relations with coping drinking motives.

Between-group comparisons in relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling that showed a significant association with coping drinking motives were assessed using linear mixed models. Group and group by hemisphere interaction were modelled as the between-subjects variable, hemisphere of ROIs (left, right) as a repeated within-subjects variable, and relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling as the dependent variable. These models also controlled for sex.

Relations between alcohol use and any relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling that significantly related to coping drinking motives were then investigated. Specifically, linear mixed models were used as above modeling group by relative difference in functional coupling interaction, this time with total drinks per typical week in the past 30 days as the dependent variable, covarying sex and age of alcohol initiation. A parallel model was conducted with total drinking days per typical week in the past 30 days as the dependent variable. Findings were considered significant at alpha ≤.025 (corrected for two drinking variables). Tests of simple slopes were used to probe any significant interactions in the above models. Models were repeated with functional coupling between ACC and ROIs in response to targets as the between-subjects variable to explore relations with alcohol use.

Medication Use

Within the bipolar disorder group, t-tests were used to explore differences in coping drinking motives and recent alcohol use between participants taking/not taking any medications, as well as between those taking/not taking any specific medication class with at least five participants on/off that medication. To explore relations between medication and relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling (in ACC-ROI pairs that showed a significant relation with coping drinking motives), a mixed model was used with medication use as a between subject variable, hemisphere as a within subject variable, and relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling as the dependent variable, covarying biological sex. Medication classes explored included sedatives/antihistamines, antipsychotics, lithium, and anticonvulsants, as well overall medication use. Significance was set at alpha <.05 for these exploratory analyses.

Sensitivity Analyses

Post hoc sensitivity analyses were conducted for all primary models, including those examining between-group difference in coping drinking motives, and relations between relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling with coping drinking motives and recent alcohol use. Sensitivity analyses included excluding 1) individuals with any current or past A/SUDs, 2) co-occurring anxiety disorders per the SCID-5-RV or 3) those taking anticonvulsants. We included a sensitivity analysis on anticonvulsant use following a main effect of anticonvulsant use on primary outcomes. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted for models examining relations between relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling with coping drinking motives and recent alcohol use, which included covarying 1) current medication use (yes/no), 2) current nicotine use (yes/no), 3) positive urine toxicology screen (yes/no), and 4) any behavioral measures that differed by group during the CPT-END task. Any main effects that did not maintain significance in these sensitivity analyses are reported below.

Exploratory Analyses

Relative Difference in ACC Functional Coupling with Anterior Insula in Response to Negative Emotional Distracters: Relations with Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, and Recent Perceived Stress

To better interpret any relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling that significantly related to coping drinking motives and alcohol use patterns in those with bipolar disorder compared to those that are typically developing, we explored how relative difference in ACC-ROI functional coupling relate to clinical constructs such as anxiety, depression, and recent perceived stress within each group. A mixed model was used with relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling and relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling by hemisphere interaction as the between subject variables, hemisphere as a within subject repeated variable, and depression symptoms (BDI) as the dependent variable, covarying sex, stratified by group. Separate parallel models were conducted with anxiety symptoms (BAI) and recent perceived stress (PSS). Significance was set at alpha <.05 for these exploratory analyses.

RESULTS

Between-group Differences in Demographic and Clinical Factors, Drinking Motives, Alcohol Use, Perceived Stress, Age of Alcohol Initiation, Impulsivity, and CPT-END Behavior

Current depressive and anxiety symptoms were higher in the bipolar disorder group, compared to the typically developing group (BDI: W=516.5, p<.001; BAI: W=452, p=.001). Additionally, there was a greater number of individuals reporting current nicotine use in the bipolar disorder group compared to the typically developing group (p=.02). See table 1 for a breakdown of the demographic and clinical factors stratified by group. There was a significant between-group difference in coping drinking motives (Wilcoxon rank sum test, W=382, p=.04), with the bipolar disorder group endorsing more coping drinking motives than the typically developing group. Similarly, there was a significant difference in recent perceived stress (t(46)=5.38, p<.001), with the bipolar disorder group exhibiting higher recent perceived stress scores than their typically developing peers. There was a significant between-group differences in total impulsivity scores (t(46)=4.56, p<.001), with higher total impulsivity scores in those with bipolar disorder compared to typically developing young adults (Table 2). No significant between-group difference was observed for recent alcohol use or age of alcohol initiation, and there were no between-group differences in social (p=.25), enhancement (p=.45) or conformity (p=.26) drinking motives (Table 2).

Table 2.

Between-group Differences in Drinking Motives, Recent Alcohol Use, Recent Perceived Stress, Age of Alcohol Initiation and Impulsivity

| Bipolar disorder (N=22) Mean (SE) |

Typically developing (N=26) Mean (SE) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Coping Drinking Motives (DMQ-R) 1 | Average Coping Drinking Motives Score | 10 (1.2) | 7 (0.6) | 0.04 W |

|

| ||||

| Average Social Drinking Motives Score | 13 (1.3) | 15 (1.0) | 0.25 W | |

|

| ||||

| Average Enhancement Drinking Motives Score | 12 (1.3) | 13 (0.9) | 0.45 W | |

|

| ||||

| Average Conformity Drinking Motives Score | 7 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 0.26 W | |

|

| ||||

| Recent Alcohol Use (DDQ) 2 | Total Drinks Consumed During Typical Drinking Week (past 30 days) | 5 (0.9) | 4 (0.8) | 0.81 W |

| Total Drinking Days During Typical Drinking Week (past 30 days) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0.82 W | |

|

| ||||

| Recent Perceived Stress 3 | Average Perceived Stress Scale Score | 33 (1.5) | 23 (1.3) | < .001 |

|

| ||||

| Age of Alcohol Initiation | Age of first drink, not just a sip from an adult’s glass, and not including drinking as part of religious ceremonies | 16 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) | 0.30W |

|

| ||||

| Impulsivity (BIS-11) 4 | BIS-11 TOTAL | 67 (2.3) | 56 (1.4) | < .001 |

Note: Between-group (bipolar disorder vs. typically developing) differences were assessed with Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon Test and two-sample t-test where appropriate. Superscript letter “W” represents p-value calculated with Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test.

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

Drinking motives were measured with the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ-R).

Alcohol use in the past 30 days was measured with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ-R).

Recent perceived stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).

Total impulsivity was measured with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11).

There was a significant between-group difference in average number of non-responses to all stimuli on the CPT-END (W=375, p<.05), with the bipolar disorder group exhibiting more non-responses (on average three non-responses) than the typically developing group (on average 0.5 non-responses). Similarly, there was a significant between-group difference in average reaction time to emotional compared to neutral stimuli on the CPT-END (t(46)=3.19, p<.01), with the bipolar disorder group exhibiting longer reaction times to negative emotional compared to neutral stimuli. Specifically, those with bipolar disorder on average took 84ms longer to respond to negative emotional compared to neutral stimuli than their typically developing peers who on average took 19ms longer to respond to emotional compared to neutral stimuli. There was no significant between-group difference in average number of incorrect responses or average number of non-responses to emotional compared to neutral stimuli, or reaction time to target (circle) stimuli on the CPT-END.

Associations Between Coping Drinking Motives and Recent Alcohol Use

Residuals from primary analyses manifested non-normality, and as such both drinking variables were logarithmically (1+x) transformed. Across both groups, higher coping drinking motives were associated with greater total drinks consumed (B=0.1, p=.001, overall model F(4,43)=4.1, p=.01, R2=.28) during a typical drinking week in the prior month. There was no significant group by coping drinking motives interaction on total drinks consumed in the prior month.

Coping Drinking Motives, Recent Alcohol Use, and Relative Difference in Functional Coupling Between Regions of Interest

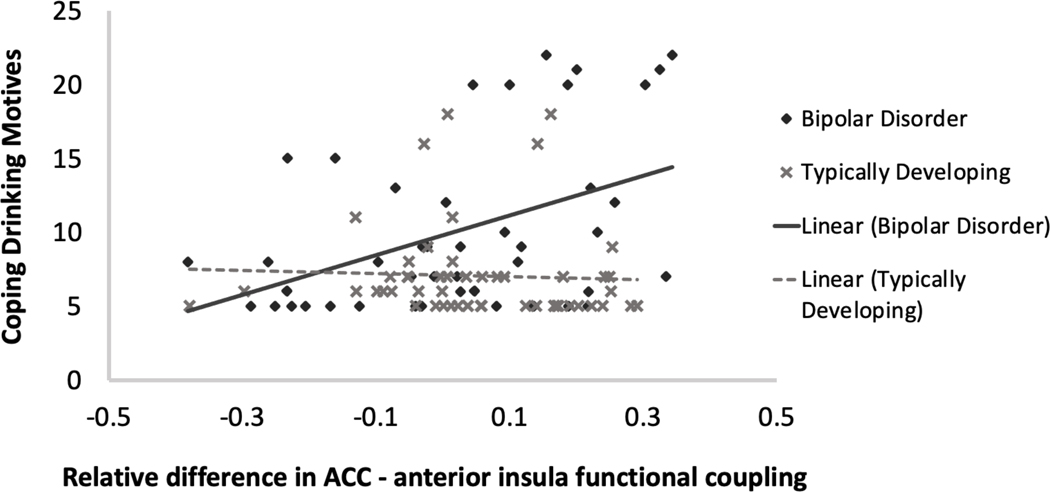

Residuals from primary analyses exhibited non-normality, and as such coping drinking motives and both drinking outcome variables were logarithmically transformed. A significant group by relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling interaction was observed on coping drinking motives (B = −1.22, p=.023, Cohen’s d= −.49). Test of simple slopes indicated that bilateral increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters was associated with higher ratings of coping drinking motives in those with bipolar disorder (B =1.0, p=.004, 95% CI [.33, 1.68]; Figure 3). There was no significant association between relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling and coping drinking motives in the typically developing group. Additionally, there was a main effect of age of alcohol use initiation and group, with earlier age of alcohol initiation associated with greater coping drinking motives (B = −.06, p=.02, d= −.49) and the bipolar disorder group presenting with higher coping drinking motives (B = −.26, p=.003, d= −.63) than the typically developing group. Relative difference in ACC-amygdala functional coupling in response to emotional distracters was not significantly associated with coping drinking motives (group by relative difference in ACC-amygdala functional coupling interaction, p=.08). Relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters did not significantly differ between groups. There were no significant associations between ACC-ROI functional coupling in response to targets and coping drinking motives.

Figure 3.

Linear mixed models were used to examine relations between coping drinking motives and relative difference in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)-anterior insula functional coupling during negative emotion processing. Greater coping drinking motives were significantly associated with greater increase in bilateral ACC-anterior insula functional coupling during negative emotion processing in those with bipolar disorder only. All analyses covaried biological sex and age of alcohol initiation. Bipolar Disorder type I: N=22; Typically Developing: N=26.

A significant group by relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling interaction was observed on total drinks consumed (B = −3.98, p<.001, d= −.77) and total drinking days (B = −2.57, p<.001, d= −.84) during typical drinking week in the past month. Tests of simple slopes indicated that increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters was associated with greater total drinks consumed (B =2.25, p=.002, 95% CI [.86, 3.65]) and greater total drinking days (B =1.6, p<.001, 95% CI [.77, 2.43]) in those with bipolar disorder. ACC-anterior insula functional coupling was not significantly associated with alcohol use in the typically developing group. There was a main effect of age of alcohol use initiation, with earlier age of alcohol initiation associated with greater total drinks consumed (B = −.12, p=.025, d= −.48) and greater total drinking days (B = −.08, p=.01, d= −.54) across all participants. Relative difference in ACC-amygdala functional coupling during emotion processing was not associated with alcohol use (all p’s≥.6). There were no significant associations between ACC-ROI functional coupling in response to targets and either recent quantity or frequency of alcohol use.

Medication Use

There was a significant difference in coping drinking motives between those taking/not taking anticonvulsants (t(20)=2.1, p=.048), with higher coping drinking motives reported in those taking (M: 14.6, SD: 7.9) versus not taking (M: 8.8, SD: 4.6) this medication class. There were no statistically significant differences in coping drinking motives or alcohol use patterns between those taking/not taking any medications in general, as well as those taking/not taking sedatives/antihistamines, antipsychotics, or lithium specifically (see Supporting Information 3 for model details). There was a significant main effect of taking any medication on relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling, wherein medication use was associated with greater relative increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters (B =.13, p=.04, d=.68). There was no statistically significant relation between any medication subclass and relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters (p’s ≥.5), although taking an anticonvulsant was associated with a relative increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters at trend level (B =.13, p=.06, d=.6).

Sensitivity Analyses

When modeling between-group difference in coping drinking motives there was no longer a significant difference after removing individuals with any current or past A/SUDs (W=132, p=.22), co-occurring anxiety disorders (W=239.5, p=.1), and anticonvulsant use (W=280.5, p=.1). Nevertheless, when modeling coping drinking motives relation with relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling, there was still a main effect of group on coping drinking motives after removing those with current or past A/SUDs (B = −.4, p=.004, d= −.8), co-occurring anxiety disorders (B = −.29, p=.003, d= −.7), and anticonvulsant use (B = −.19, p=.03, d= −.49) with the bipolar disorder group presenting with higher coping drinking motives than their typically developing peers in these sensitivity analyses. The group by relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling interaction on coping drinking motives remained significant when removing individuals with any current or past A/SUDs (B = −2.44, p<.001, d= −1.1), however it was no longer significant after removing those using anticonvulsants (B = −.81, p=.13, d= −.34). Group by relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling interaction on coping drinking motives was reduced to trend when covarying medication use (B = −1.08, p=.048, d= −.43; test of simple slopes, bipolar disorder: B =.86 p=.02, 95% CI [.14, 1.57]; typically developing: not significant). Group by relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling interaction on recent alcohol use remained significant in all sensitivity analyses.

When conducting linear mixed models, the main effect of age of alcohol use initiation on coping drinking motives was no longer significant after removing individuals with any current or past A/SUDs (B = −.03, p=.33, d= −.26), co-occurring anxiety disorders (B = −.03, p=.3, d= −.24), or anticonvulsant use (B = −.03, p=.25, d= −.26). Additionally, main effect of group on coping drinking motives was no longer significant when covarying medication use (B = −.09, p=.54, d= −.13). Main effect of age of alcohol use initiation on total drinks consumed was no longer significant after removing individuals with any current or past A/SUDs (B = −.11, p=.09, d= −.45), co-occurring anxiety disorders (B = −.06, p=.3, d= −.24), or anticonvulsant use (B = −.1, p=.12, d= −.35). Additionally, main effect of age of alcohol use initiation on total drinking days was no longer significant after removing individuals with co-occurring anxiety disorders (B = −.07, p=.06, d= −.44), or anticonvulsant use (B = −.06, p=.11, d= −.36).

Exploratory Analyses

Relative Difference in ACC Functional Coupling with Anterior Insula in Response to Negative Emotional Distracters: Relations with Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, and Recent Perceived Stress

Greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to emotional distracters was significantly associated with greater anxiety symptoms (B =12.3, p=.03, d=.69) and recent perceived stress (B =11.5, p<.01, d=.94) in the bipolar disorder group. There was no significant association between ACC-anterior insula functional coupling and depression symptoms. There was no significant association between ACC-anterior insula functional coupling and anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, or recent perceived stress in the typically developing group.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine how relative difference in functional coupling among ACC, amygdala, and anterior insula in response to negative affective compared to neutral stimuli relates to coping drinking motives and alcohol use in young adults with bipolar disorder compared to those that are typically developing. Results support our hypotheses. Specifically, coping drinking motives were rated higher in young adults with bipolar disorder than their typically developing peers, with greater coping drinking motives associated with greater quantity of recent alcohol use across both groups. While functional coupling among ROIs in response to negative emotional stimuli did not differ between groups, greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in response to negative emotional stimuli was associated with greater coping drinking motives, as well as greater quantity and frequency of recent alcohol use in bipolar disorder only. Lastly, in young adults with bipolar disorder greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling was related to greater anxiety symptoms and recent perceived stress suggesting possible clinical factors that may increase coping drinking motives and contribute to alcohol misuse in this psychiatric group.

To better interpret findings, the individual roles of the ACC and anterior insula regions in emotion regulation must be considered. The ACC is part of an attentional circuit implicated in cognitive and affective regulation processes (Bush et al., 2000) with neuroanatomical projections to both prefrontal cognitive control networks and the affective limbic system (Stevens et al., 2011). Both the anterior insular cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex comprise critical structures of the salience network implicated in attentional control (Uddin, 2015). Additionally, the anterior insula is highly connected with limbic and paralimbic systems, including the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices and has been implicated in the subjective feeling of emotions (i.e., emotional awareness). The anterior insula is increasingly recognized as having a key role in processing of interoceptive information (Chen et al., 2021). Greater insula reactivity during emotion processing has been previously reported in anxiety-prone individuals (Stein et al., 2007), and greater unpredictable-threat-related insula reactivity has been associated with coping drinking motives and problematic drinking in individuals with AUDs (Gorka et al., 2020). These observations suggest greater insula activity contributes to increased subjective awareness of emotions. For example, acute alcohol intake has been shown to dampen ACC-insula functional connectivity which has, in turn, been associated with increased subjective ratings of calmness (Gorka et al., 2018).

In our sample of young adults with bipolar disorder, greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling to negative affective stimuli was also associated with greater self-reported anxiety symptoms and recent perceived psychological stress. Of note, ACC-anterior insula functional coupling was not related to anxiety symptoms or recent perceived stress in the typically developing group, which may be attributable to lower levels of perceived stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms observed in this group on the day of scan. Although this study cannot infer causality, results may suggest greater attention towards interoceptive signals in those with bipolar disorder, and through this mechanism, a corresponding desire to use alcohol as a maladaptive coping strategy. Future studies designed and powered to investigate mediation effects of coping drinking motives on alcohol use, as well as clinical factors such as emotion dysregulation and distress tolerance that may contribute to alcohol misuse in this population, are necessary to further clarify the directionality of these associations.

There were no statistically significant between-group differences in recent alcohol use or relative difference in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling in our results. This may be attributable to the fact that participants are early in the course of bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is a progressive condition (Strakowski et al., 2012, Weathers et al., 2018) and more distinct between-group differences in alcohol use and neural functional coupling may emerge later in the course of illness. Additionally, greater differences in functional coupling among anterior limbic and paralimbic regions may exist during mania or depression. For example, recently we reported a loss of functional connectivity between the ACC and amygdala during mania in youth with bipolar disorder (Lippard et al., 2020). Additionally, greater coping drinking motives have been suggested to relate to depressive mood states in adults with bipolar disorder (Meyer et al., 2012). As most of our sample were euthymic, future research investigating neural correlates that may contribute to changes in motives during mania and depression is needed.

Most participants in the bipolar disorder group were medicated at the time of scan. Although recruiting an unmedicated sample could address this issue, it could limit generalizability of findings. While exploratory analyses suggest medication use, i.e., anticonvulsants, may be associated with greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling to negative affective stimuli, this study was not powered to investigate medication effects. Consequently, findings must be interpreted with caution and causality cannot be inferred. Medication use may indicate general illness severity and differences in neural reactivity to emotional stimuli or endorsement of coping drinking motives may be associated with illness severity rather than use of medications. In the bipolar disorder group, the five participants taking anticonvulsants objectively presented with higher coping drinking motives (mean:15, standard error:3.5) than those not taking this medication class (mean:9, standard error:1.1). In healthy participants, anticonvulsants have been found to impact corticolimbic circuitry, with greater anterior cingulate functional connectivity reported when participants were dosed with an anticonvulsant (Li et al., 2011). In bipolar disorder, evidence suggests psychotropic medications may normalize brain function, and thereby, minimize between-group differences (Hafeman et al., 2012, Li et al., 2019). More systematic studies are needed in this area. Critically, medication is not prescribed randomly and anticonvulsants have shown efficacy for treatment of alcohol/substance use problems, including treatment of withdrawal symptoms, and heavy alcohol use and craving (Mason et al., 2014, Hammond et al., 2015). We cannot discern if anticonvulsant use and/or related changes in neural circuitry contributed to drinking motives or if other confounding factors relate to this association. Future studies powered to investigate effects of medication on neural response, associated coping drinking motives, and alcohol use are needed, including individual medications and combinations of drugs commonly prescribed in bipolar disorder.

Several limitations and considerations for future investigation must be noted. The first of these is the small sample size that limits power, particularly for exploratory analyses. Additionally, most young adults in the bipolar disorder group were medicated at the time of scan. While we explored the effects of medication on our variables of interest, this study was not powered to investigate the impact of medication on findings specifically. This is particularly important given some of the observed preliminary findings for anticonvulsant use. It is important to note that our sample is reflective of a generalizable group of young adults with bipolar disorder, with history of suicide attempt(s), psychotic symptoms, comorbid alcohol, and other substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders. Although alleviation of affective symptoms is one of the most cited reasons for alcohol and other substance misuse in this population, individuals with bipolar disorder may misuse alcohol for other non-mood-related reasons (Bizzarri et al., 2007, McDonald and Meyer, 2011). Studies are needed to investigate alternate drinking motives using fMRI tasks suited for their investigation (e.g., a reward-processing fMRI task to investigate enhancement drinking motives). These studies could further examine relations with different mood states, alcohol use, and neural functional coupling. Additionally, due to the nature of the CPT-END task, participants were exposed to fewer emotional stimuli than would have been the case in a pure emotional stimulus task. This may have contributed to the lack of observed between group differences, and the attentional component of the CPT-END may have influenced emotion processing. Although we did not see relations among functional coupling to targets and either coping drinking motives or recent alcohol use, future investigation is needed to replicate our results utilizing fMRI tasks intended to study neural response to affective stimuli (e.g., facial affect processing fMRI task).

Additional limitations and suggestions for future investigation include the need to investigate sex differences (Lippard et al., 2017, Kuntsche et al., 2006) and alcohol use assessment on the day of scan. Specifically, we were underpowered to investigate sex differences, although we did control for sex in all main models. Additionally, while participants were asked to abstain from alcohol and other drug use for 24 hours prior to their scan, and the sample is generally representative of light social drinkers that drink on average 2 days a week, we cannot rule out that some individuals may have consumed alcohol or other drugs within 24 hours of their scan. This may have impacted study findings. Studies have shown acute alcohol exposure and withdrawal symptoms may relate to differences in function and connectivity within prefrontal-limbic systems (Gorka et al., 2013, Tapert et al., 2004). While we cannot discern directionality (if recent alcohol use directly contributes to differences in BOLD response or if BOLD response may distinguish those that have difficulty abstaining from alcohol use), findings highlight need for future studies to investigate recent alcohol use—including latency since last drinking episode—and craving and withdrawal symptoms (Ekhtiari et al., 2022), their relation to neural function, coping drinking motives, and prospective alcohol use. It is important to note, however, that findings in heavier alcohol using samples may not generalize to lighter/social drinkers, like those included in this study. Finally, as with all self-report assessments, this study cannot discern whether a participant’s endorsement of coping drinking motives reflects an accurate self-report of why an individual drinks or if greater endorsement of coping motives reflects how an individual may explain their drinking to themselves and others. Nevertheless, it is important to note that self-talk is a critical element in behavior change (D’Amico et al., 2015). While greater increase in ACC-anterior insula functional coupling relations with greater coping drinking motives, anxiety, and recent perceived stress in bipolar disorder may suggest underlying biomarkers that contribute to greater coping drinking motives, longitudinal investigations are needed to disentangle relations among these constructs. Regardless, these results are an important first step in informing the hypotheses, design, and implementation of larger powered neuroimaging investigations in this highly understudied area.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors were supported by research grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) K01 AA027573 (ETCL), R21 AA027884 (ETCL), R01 AA020637 (KF), T32 AA007471 (VT); and the Jones/Bruce Fellowship from the Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research (DEK, VT). We acknowledge the contributions of Wade Weber, Sara Fudjack and Sepeadeh Radpour for participant recruitment and data collection. We thank our participants for volunteering their time and supporting our research.

Data Sharing:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Disclosures: We do not believe any of these relationships could influence the reported results, but we report them for transparency. SMS serves as DSMB chair for Sunovion and served recently on a DMC for Otsuka. He is also a contributor to Medscape. ETCL received funding for a Janssen-sponsored study through University of Texas at Austin. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bangasser DA & Cuarenta A. 2021. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: circuits and mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G. & Steer RA 1988. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol, 56, 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J. & Erbaugh J. 1961. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 4, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi Y, Restom K, Liau J. & Liu TT 2007. A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage, 37, 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarri JV, Sbrana A, Rucci P, Ravani L, Massei GJ, Gonnelli C, Spagnolli S, Doria MR, Raimondi F. & Endicott J. 2007. The spectrum of substance abuse in bipolar disorder: reasons for use, sensation seeking and substance sensitivity. Bipolar Disorders, 9, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, Robinson J. & Sareen J. 2009. Self-medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Affect Disord, 115, 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann AF, Schmid B, Blomeyer D, Becker K, Treutlein J, Zimmermann US, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Schmidt MH, Esser G. & Banaschewski T. 2009. Impact of age at first drink on vulnerability to alcohol-related problems: testing the marker hypothesis in a prospective study of young adults. J Psychiatr Res, 43, 1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann AF, Schmid B, Blomeyer D, Zimmermann US, Jennen‐Steinmetz C, Schmidt MH, Esser G, Banaschewski T, Mann K. & Laucht M. 2010. Drinking against unpleasant emotions: possible outcome of early onset of alcohol use? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P. & Posner MI 2000. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci, 4, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB & Carey MP 1995. Reasons for drinking among psychiatric outpatients: Relationship to drinking patterns. Psychol Addict Behav, 9, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW & Phillips ML 2016. Elucidating neural network functional connectivity abnormalities in bipolar disorder: toward a harmonized methodological approach. Biological psychiatry: cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 1, 288–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Whittle S, Simmons J, Yücel M. & Lubman DI 2014. Volumetric differences in the anterior cingulate cortex prospectively predict alcohol-related problems in adolescence. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 231, 1731–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, Simmons JM, Cui C, Valentino R, Gnadt JW, Nielsen L, Hillaire-Clarke CS & Spruance V. 2021. The emerging science of interoception: sensing, integrating, interpreting, and regulating signals within the self. Trends Neurosci, 44, 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty KM, Lagopoulos J, Hickie IB & Hermens DF 2013. Risky alcohol use in young persons with emerging bipolar disorder is associated with increased oxidative stress. J Affect Disord, 150, 1238–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T. & Mermelstein R. 1983. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav, 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA & Marlatt GA 1985. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol, 53, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML 1994. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess, 6, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Houck JM, Hunter SB, Miles JN, Osilla KC & Ewing BA 2015. Group motivational interviewing for adolescents: change talk and alcohol and marijuana outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol, 83, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Craddock N. & van den Bree M. 2014. Alcohol misuse in bipolar disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of comorbidity rates. Eur Psychiatry, 29, 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekhtiari H, Zare-Bidoky M, Sangchooli A, Janes AC, Kaufman MJ, Oliver J, et al. 2022. A methodological checklist for fMRI drug cue reactivity studies: development and expert consensus. Nature Protocols, 17, 567–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Gosai AK, Felicione JM, Peters AT, Shea CV, Sylvia LG, Nierenberg AA, Widge AS, Dougherty DD & Deckersbach T. 2019. Deficits in frontoparietal activation and anterior insula functional connectivity during regulation of cognitive‐affective interference in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders, 21, 244–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed NM, Kim MJ, Fields KM, Olvera RL, Hariri AR & Williamson DE 2018. Trajectories of alcohol initiation and use during adolescence: the role of stress and amygdala reactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 57, 550–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS & Spitzer RL (eds.) 2015. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV), Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Young CM, Steers M-LN, Quist MC, Bryan JL & Neighbors C. 2014. Tears in your beer: Gender differences in coping drinking motives, depressive symptoms and drinking. International journal of mental health and addiction, 12, 730–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Fitzgerald DA, King AC & Phan KL 2013. Alcohol attenuates amygdala–frontal connectivity during processing social signals in heavy social drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 229, 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Kreutzer KA, Petrey KM, Radoman M. & Phan KL 2020. Behavioral and neural sensitivity to uncertain threat in individuals with alcohol use disorder: Associations with drinking behaviors and motives. Addict Biol, 25, e12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Phan KL & Childs E. 2018. Acute calming effects of alcohol are associated with disruption of the salience network. Addict Biol, 23, 921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves BS, Hall ME, Dias-Karch C, Haischer MH & Apter C. 2021. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS One, 16, e0255634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, Chang KD, Garrett AS, Sanders EM & Phillips ML 2012. Effects of medication on neuroimaging findings in bipolar disorder: an updated review. Bipolar disorders, 14, 375–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CJ, Niciu MJ, Drew S. & Arias AJ 2015. Anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and alcohol use disorders. CNS drugs, 29, 293–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismaylova E, Di Sante J, Gouin J-P, Pomares FB, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE & Booij L. 2018. Associations between daily mood states and brain gray matter volume, resting-state functional connectivity and task-based activity in healthy adults. Front Hum Neurosci, 12, 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanny D, Naimi TS, Liu Y, Lu H. & Brewer RD 2018. Annual total binge drinks consumed by US adults, 2015. Am J Prev Med, 54, 486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG & Leaf PJ 1996. The epidemiology of co‐occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 66, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G. & Engels R. 2006. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav, 31, 1844–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ji E, Tang F, Qiu Y, Han X, Zhang S, Zhang Z. & Yang H. 2019. Abnormal brain activation during emotion processing of euthymic bipolar patients taking different mood stabilizers. Brain Imaging Behav, 13, 905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Large CH, Ricci R, Taylor JJ, Nahas Z, Bohning DE, Morgan P. & George MS 2011. Using interleaved transcranial magnetic stimulation/functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and dynamic causal modeling to understand the discrete circuit specific changes of medications: lamotrigine and valproic acid changes in motor or prefrontal effective connectivity. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 194, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard ET, Mazure CM, Johnston JA, Spencer L, Weathers J, Pittman B, Wang F. & Blumberg HP 2017. Brain circuitry associated with the development of substance use in bipolar disorder and preliminary evidence for sexual dimorphism in adolescents. J Neurosci Res, 95, 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard ET, Weber W, Welge J, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Almeida J, DelBello MP & Strakowski SM 2020. Variation in rostral anterior cingulate functional connectivity with amygdala and caudate during first manic episode distinguish bipolar young adults who do not remit following treatment. Bipolar disorders, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashhoon Y, Czerkawski C, Crowley DJ, Cohen‐Gilbert JE, Sneider JT & Silveri MM 2014. Binge alcohol consumption in emerging adults: anterior cingulate cortical “thinness” is associated with alcohol use patterns. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38, 1955–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M. & Begovic A. 2014. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine, 174, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JL & Meyer TD 2011. Self‐report reasons for alcohol use in bipolar disorders: why drink despite the potential risks? Clin Psychol Psychother, 18, 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TD, McDonald JL, Douglas JL & Scott J. 2012. Do patients with bipolar disorder drink alcohol for different reasons when depressed, manic or euthymic? J Affect Disord, 136, 926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi Y, Touroutoglou A, Dickerson BC & Barrett LF 2014. Sex differences in the neural correlates of affective experience. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 9, 591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen H-H, Hatch JP, Nicoletti MA, Monkul ES, Lafer B. & Soares JC 2010. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatr Res, 44, 278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS & Barratt ES 1995. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol, 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier MR, Verplaetse TL, Mineur YS, Petrakis IL, Cosgrove KP, Picciotto MR & McKee SA 2019. Sex differences in stress-related alcohol use. Neurobiology of stress, 10, 100149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML & Swartz HA 2014. A critical appraisal of neuroimaging studies of bipolar disorder: toward a new conceptualization of underlying neural circuitry and a road map for future research. Am J Psychiatry, 171, 829–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressl C, Brandner P, Schaffelhofer S, Blackmon K, Dugan P, Holmes M, Thesen T, Kuzniecky R, Devinsky O. & Freiwald WA 2019. Resting state functional connectivity patterns associated with pharmacological treatment resistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res, 149, 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisciandaro J, Tolliver B, Prescot A, Brenner H, Renshaw P, Brown T. & Anton R. 2017. Unique prefrontal GABA and glutamate disturbances in co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence. Translational psychiatry, 7, e1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL & Goodwin FK 1990. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA, 264, 2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scavone A, Timmins V, Collins J, Swampillai B, Fonseka TM, Newton D, Naiberg M, Mitchell R, Ko A. & Shapiro J. 2018. Dimensional and categorical correlates of substance use disorders among Canadian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 159–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS & Paulus MP 2007. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. Am J Psychiatry, 164, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens FL, Hurley RA & Taber KH 2011. Anterior cingulate cortex: unique role in cognition and emotion. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 23, 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Adler CM, Almeida J, Altshuler LL, Blumberg HP, Chang KD, DelBello MP, Frangou S, McIntosh A. & Phillips ML 2012. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a consensus model. Bipolar disorders, 14, 313–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM & DelBello MP 2000. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev, 20, 191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Cotton S, Luberto CM, Patino LR, Stahl LA, Weber WA, Eliassen JC, Sears R. & DelBello MP 2016. Neural function before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in anxious adolescents at risk for developing bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 26, 372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Schweinsburg AD, Barlett VC, Brown SA, Frank LR, Brown GG & Meloy MJ 2004. Blood oxygen level dependent response and spatial working memory in adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 1577–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ 2015. Salience processing and insular cortical function and dysfunction. Nature reviews neuroscience, 16, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Kalmar JH, He Y, Jackowski M, Chepenik LG, Edmiston EE, Tie K, Gong G, Shah MP & Jones M. 2009. Functional and structural connectivity between the perigenual anterior cingulate and amygdala in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 66, 516–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers J, Lippard ET, Spencer L, Pittman B, Wang F. & Blumberg HP 2018. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study of adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 57, 111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis S, Patil KR, Hoffstaedter F, Nostro A, Yeo BT & Eickhoff SB 2020. Sex classification by resting state brain connectivity. Cereb Cortex, 30, 824–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Kolodziej M, Griffin ML, Najavits LM, Jacobson LM & Greenfield SF 2004. Substance use and perceived symptom improvement among patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. J Affect Disord, 79, 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S. & Nieto-Castanon A. 2012. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect, 2, 125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase J, Makris N, Braus DF, Mann K, Smolka MN, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Hodge SM, Tang L. & Albaugh M. 2008. Amygdala volume associated with alcohol abuse relapse and craving. Am J Psychiatry, 165, 1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H, LaBar KS & McCarthy G. 2002. Dissociable prefrontal brain systems for attention and emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99, 11447–11451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE & Meyer DA 1978. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 133, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.