Abstract

Patient: Male, 60-year-old

Final Diagnosis: MSSA bacteremia • osteomyelitis • prostate abscess

Symptoms: Fevers • chills • flank pain • dysuria

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: CT guided percutaneous abscess drainage

Specialty: Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Staphylococcus aureus (SA) is a rare cause of prostatic abscess. Risk factors include genito-urinary instrumentalization and immunocompromised states. Because of the lack of guidelines on the diagnosis, management, and follow-up of SA prostate abscess, the diagnosis can sometimes be challenging. Our patient was a 60-year-old man who initially presented with lower back pain and was diagnosed with a methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia, prostate abscess, osteomyelitis, and myositis.

Case Report:

A 60-year-old man presented with lower back pain. He had a past medical history of incompletely treated MSSA cervical osteomyelitis with epidural abscess, alcohol use disorder, intravenous drug use (IVDU), and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM). He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Laboratory test results revealed leukocytosis and an elevated C reactive protein (CRP). Lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed vertebral osteomyelitis and right psoas myositis. Blood cultures isolated MSSA. The patient was treated with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam. On day 5, our patient reported having fever, chills, flank pain, and dysuria. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 4.0×4.9 cm prostatic abscess. CT-guided percutaneous abscess drainage was performed, and fluid culture revealed MSSA. Both antibiotics were discontinued and cefazolin was started following sensitivities. Post-drainage pelvic ultrasound (US) showed resolution of the abscess.

Conclusions:

This case highlights the importance of a rapid diagnosis of SA prostate abscess in patients with documented risk factors and characteristic symptoms. Timely management with antibiotics and drainage as indicated are imperative to avoid further complications from the underlying bacteremia, including sepsis and metastatic infections.

Keywords: Abscess, Bacteremia, Case Reports, Myositis, Osteomyelitis, Prostate

Background

Prostate abscess is a rare condition. The majority of prostatic abscesses are caused by gram-negative enteric bacteria (especially Escherichia coli) [1,2]. Staphylococcus aureus (SA) is a rare cause of prostatic abscess [3] and only a few cases have been reported. Risk factors for SA prostate abscess include urinary tract instrumentalization or damage, bladder voiding disturbances, and immunocompromised states [4–7]. Despite the absence of clear guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of prostate abscess, physicians should promptly recognize and treat prostate abscess, as delayed management can lead to complications, including urosepsis and septic shock [2,8]. Our patient was a 60-year-old man who initially presented with lower back pain and was diagnosed with a methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia, prostate abscess, osteomyelitis, and myositis.

Case Report

History of Present Illness

A 60-year-old man presented with a 1-week history of lower back pain, worse on flexion of the right thigh. He also reported a week-long course of poorly localized, pressure-like chest pain, lasting a few minutes. He denied any fever, chills, malaise, dysuria, flank pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, headache, shortness of breath, palpitations, or cough.

Past Medical History

Our patient had a history of incompletely treated MSSA cervical osteomyelitis with epidural abscess 2 years prior, coronary artery disease (CAD) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). He had chronic alcohol use disorder, long-term intravenous drug use (IVDU) on methadone, and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM).

Physical Examination

On admission, the patient had a temperature of 36.5°C (97.7°F), a blood pressure of 183/104 mmHg, a pulse of 87/min, and a respiratory rate of 20/min, with an oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Cardiac auscultation showed a systolic murmur predominant in the tricuspid area, lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally, and a spine examination showed lumbar spine tenderness. The rest of the physical examination was within normal limits.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis of 32.22×103/mcL with neutrophilic predominance of 90%, and a C reactive protein (CRP) of 331 mg/L. His troponin level was normal. Urinalysis was negative for nitrites, leukocytes esterase, bacteria, leukocytes, and red blood cells. A chest X-ray did not show any new infiltrate, but revealed surgical metal sutures and median sternotomy. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm without evidence of ischemia. Blood and urine cultures were sent and the patient was empirically started on vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam.

Imaging and Initial Management

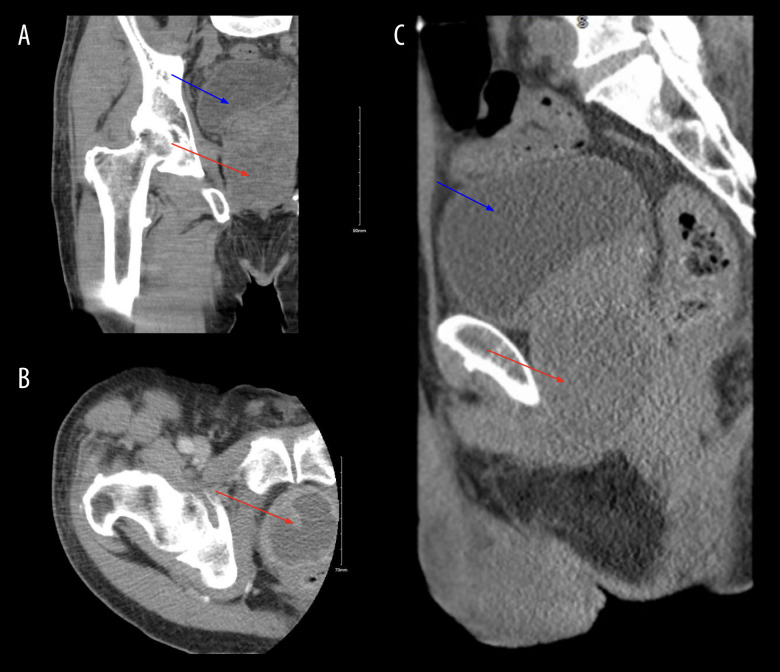

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine with contrast on day 2 showed patchy marrow edema and enhancement within L2 and L3 vertebral bodies, suggesting osteomyelitis, along with right psoas myositis, and phlegmon of paravertebral soft tissues. No drainable abscess was seen; therefore, surgical intervention was not indicated. A transthoracic echo-cardiogram (TTE) on day 4 did not rule out valvular vegetation, and showed unquantified tricuspid regurgitation, moderately elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (40–50 mmHg), and a normal left ventricular ejection fraction, diastolic dysfunction, chordae, and mitral leaflet calcification. The diagnosis of tricuspid valve infective endocarditis was considered. The patient was initially treated with i.v. vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for broad antibiotic coverage for osteomyelitis, right psoas myositis, and paravertebral soft tissue phlegmon. On day 4, blood and urine cultures yielded MSSA sensitive to cefazolin. We discontinued piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin, and started i.v. cefazolin. The patient remained afebrile, with reduction in inflammatory markers (white blood count 16×10/mcL and the CRP 259.8 mg/L). On day 5, the patient reported having subjective fever, chills, flank pain, and dysuria. He denied hematuria or straining on urination. A digital rectal exam revealed a tender prostate without bogginess or fluctuance. Differentials included acute bacterial prostatitis and prostate abscess. A contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the right hip demonstrated a 4.0×4.9 cm peripherally enhancing fluid collection suggestive of prostatic abscess (Figure 1). Blood cultures remained positive for MSSA. The diagnosis of MSSA prostate abscess was made. The question of whether the prostate abscess was the source of the bacteremia or a metastatic infection secondary to MSSA bacteremia remains unknown.

Figure 1.

Contrast computed tomography (CT) of the right hip with coronal (A), axial (B) and sagittal views (C) showing a 4.0×4.9 cm peripherally enhanced fluid collection within the prostate, suspicious for an abscess (see red arrow), along withbladder distension (see blue arrow).

Treatment and Follow-Up

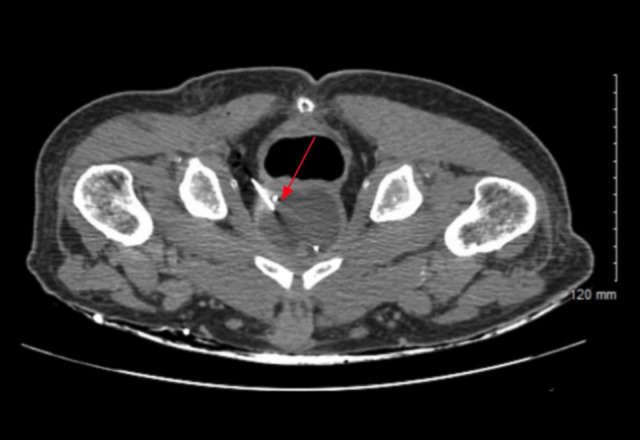

CT-guided percutaneous abscess drainage was performed on day 8 (Figure 2), and abscess fluid culture grew MSSA. He was continued on i.v. cefazolin. Follow-up pelvic ultrasound after drainage on day 13 showed an enlarged prostate measuring 3.18×4.87 cm, without abscess (Figure 3). Prostate fluid culture yielded MSSA sensitive to cefazolin. His condition remained stationary, his back pain was controlled with hydromorphone, and he remained afebrile. Laboratory values showed decreasing white blood cell count (13.26×10/mcL). The subsequent 3 blood cultures were negative. The patient was discharged on day 20 on i.v. cefazolin to complete 6 weeks of treatment, hydromorphone for pain control, methadone, and insulin.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (CT)-guided prostate abscess transgluteal (or transperineal) drainage (see red arrow). Approximately 60 mL of purulent fluid was aspirated, and specimens were collected for fluid culture.

Figure 3.

Post-drainage pelvic ultrasound shows a severely enlarged prostate (volume 40cc) without fluid collection (see blue arrows).

Discussion

Prostate abscess can be a diagnostic challenge. We present a case of MSSA prostate abscess discovered on day 5 of admission in a patient with a history of incompletely treated MSSA epidural abscess, IVDU, and poorly-controlled DM. Our patient initially presented for low back pain, and on day 5 started reporting flank pain, subjective fever, chills, and dysuria.

Prostate abscess is a rare condition. Gram-negative Enterobacteria, especially E. coli, are the leading pathogens causing prostate abscesses [1,2], while SA remains an uncommon cause, with most cases secondary to MRSA [3]. However, studies have shown that invasive MSSA is a public health problem in the United States, and the incidence of MSSA infections was 1.8 times higher than MRSA in 2015 [9]. SA prostate abscess mostly occurs in patients with a history of urinary tract instrumentalization (eg, biopsy or surgery) or damage (eg, perineal injury), bladder voiding disturbances, immunocompromised patients (including IVDU and DM), and patients with bacteriemia [4–7,10]. IVDU, poorly-controlled DM, and incompletely treated MSSA epidural abscess were notable risk factors in our patient. He initially presented only with lower back pain, while fever, chills, dysuria, and flank pain were noted on day 5 of admission. Similarly, the most common symptoms reported in the literature were abdominal or perineal pain, fever, and urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urinary retention, and difficulty of micturition [11]. The modality of imaging that was mostly used was CT [12–15].

Currently, there are no guidelines for management and follow-up of prostate abscess. However, current clinical practice revolves around parenteral antibiotics with or without drainage [2,16]. There are a few cases reports of resolution of the abscess without drainage [11–15,17–19]. Drainage options for prostate abscesses include transrectal, transurethral, transperineal, and open approaches [20]. According to the literature, small abscesses <1 cm respond well to medical therapy, while large abscesses >1 cm require drainage [21]. In our case report, the 4.0×4.9 cm abscess was drained percutaneously with CT-guided prostate aspiration, with resolution of the abscess. The choice of antibiotics is also variable among authors, the most common being vancomycin [11]. Anti-staphylococcal antibiotics such as linezolid and clindamycin were found to decrease SA toxic effects [22]. Prompt diagnosis and treatment have been shown to decrease morbidity in cases of prostate abscess [7,8]. Rapid clinical improvement was seen in our patient. He was discharged with i.v. cefazolin to complete 6 weeks of medical therapy.

Conclusions

This case highlighted the importance of a rapid diagnosis of SA prostate abscess in patients with documented risk factors and characteristic symptoms. Timely management with antibiotics and drainage as indicated is imperative to avoid further complications from the underlying bacteremia, including sepsis and metastatic infections.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Weinberger M, Cytron S, Servadio C, et al. Prostatic abscess in the antibiotic era. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(2):239–49. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DS, Choe HS, Kim HY, et al. Acute bacterial prostatitis and abscess formation. BMC Urol. 2016;16(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll DE, Marr I, Huang GKL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess: A clinical case report and a review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granados EA, Riley G, Salvador J, Vincente J. Prostatic abscess: Diagnosis and treatment. J Urol. 1992;148(1):80–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barozzi L, Pavlica P, Menchi I, et al. Prostatic abscess: Diagnosis and treatment. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(3):753–57. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.3.9490969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira P, Andrade JA, Porto HC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of prostatic abscess. Int Braz J Urol. 2003;29(1):30–34. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382003000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aravantinos E, Kalogeras N, Zygoulakis N, et al. Ultrasound-guided transrectal placement of a drainage tube as therapeutic management of patients with prostatic abscess. J Endourol. 2008;22(8):1751–54. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelmoteleb H, Rashed F, Hawary A. Management of prostate abscess in the absence of guidelines. Int Braz J Urol. 2017;43(5):835–40. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2016.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson KA, Gokhale RH, Nadle J, et al. Public health importance of invasive methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infections: Surveillance in 8 US Counties, 2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(6):1021–28. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichenberger EM, Shoff CJ, Rolfe R, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess in the setting of prolonged S. aureus bacteremia. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2020;2020:7213838. doi: 10.1155/2020/7213838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll DE, Marr I, Huang GKL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess: A clinical case report and a review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande A, Haleblian G, Rapose A. Prostate abscess: MRSA spreading its influence into Gram-negative territory: Case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009057. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park SC, Lee JW, Rim JS. Prostatic abscess caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Urol. 2011;18(7):536–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2011.02774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng X, Wang X, Zhou J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess involving the seminal vesicle: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(3):835–38. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jana T, Machicado JD, Davogustto GE, Pan JJ. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prostatic abscess in a liver transplant recipient. Case Rep Transplant. 2014;2014:854824. doi: 10.1155/2014/854824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackerman AL, Parameshwar PS, Anger JT. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with prostatic abscess in the post-antibiotic era. Int J Urol. 2018;25(2):103–10. doi: 10.1111/iju.13451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin MY, Rezai K, Schwartz DN. Septic pulmonary emboli and bacteremia associated with deep tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(4):1553–55. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02379-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beckman TJ, Edson RS. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prostatitis. Urology. 2007;69(4):779.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nargund VH, Stewart PA. Acute bacterial prostatitis with osteomyelitis. J R Soc Med. 1995;88(6):355P–56P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elshal AM, Abdelhalim A, Barakat TS, et al. Prostatic abscess: Objective assessment of the treatment approach in the absence of guidelines. Arab J Urol. 2014;12(4):262–68. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou YH, Tiu CM, Liu JY, et al. Prostatic abscess: Transrectal color Doppler ultrasonic diagnosis and minimally invasive therapeutic management. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30(6):719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dumitrescu O, Badiou C, Bes M, et al. Effect of antibiotics, alone and in combination, on panton-valentine leukocidin production by a Staphylococcus aureus reference strain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(4):384–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]