Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between goal attainment and patient-reported outcomes in patients who engaged in a 6-session, telephone-based, cognitive-behavioral–based physical therapy (CBPT) intervention after spine surgery.

Methods

In this secondary analysis of a randomized trial, data from 112 participants (mean age = 63.3 [SD = 11.2] years; 57 [51%] women) who attended at least 2 CBPT sessions (median = 6 [range = 2–6]) were examined. At each session, participants set weekly goals and used goal attainment scaling (GAS) to report goal attainment from the previous session. The number and type of goals and percentage of goals met were tracked. An individual GAS t score was computed across sessions. Participants were categorized based on goals met as expected (GAS t score ≥ 50) or goals not met as expected (GAS t score < 50). Six- and 12-month outcomes included disability (Oswestry Disability Index), physical and mental health (12-Item Short-Form Health Survey), physical function (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), pain interference (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), and back and leg pain intensity (numeric rating scale). Outcome differences over time between groups were examined with mixed-effects regression.

Results

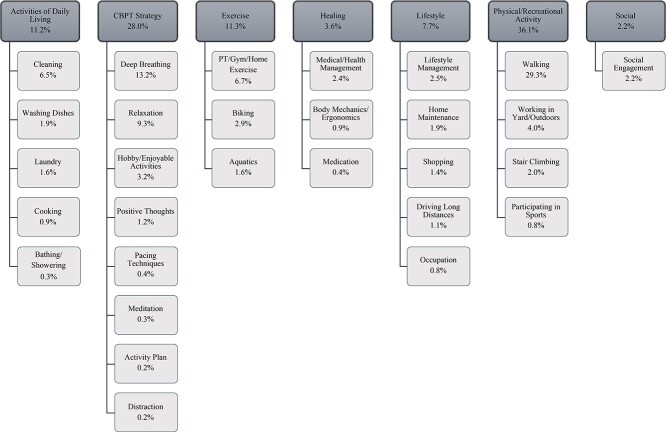

Participants set a median of 3 goals (range = 1–6) at each session. The most common goal categories were recreational/physical activity (36%), adopting a CBPT strategy (28%), exercising (11%), and performing activities of daily living (11%). Forty-eight participants (43%) met their goals as expected. Participants who met their goals as expected had greater physical function improvement at 6 months (estimate = 3.7; 95% CI = 1.0 to 6.5) and 12 months (estimate = 2.8; 95% CI = 0.04 to 5.6). No other outcome differences were noted.

Conclusions

Goal attainment within a CBPT program was associated with 6- and 12-month improvements in postoperative physical functioning.

Impact

This study highlights goal attainment as an important rehabilitation component related to physical function recovery after spine surgery.

Keywords: Arthrodesis, Back Pain, Postoperative Care, Psychotherapy, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Patient-centered goal setting is a core behavioral component of rehabilitation programs, where individuals, in collaboration with a health care provider, identify and set meaningful goals based on what is important for them to accomplish.1 Patient-centered goal setting involves a complex interaction between the individual and provider and may not reflect standard physical therapist practice.2 Common challenges to patient-centered goal setting in the clinic include inadequate time, communication barriers, and lack of clinician self-awareness of patient-centered principles and practices.3–5 Individuals may also experience difficulty in expressing meaningful goals.6 Greater awareness of commonly expressed patient-centered goals could offer insight into the range of activities or behaviors individuals consider meaningful.

Patient-centered goal setting is an essential process in the transformation of standard physical therapy to psychologically informed physical therapy (PIPT), an optimal approach to the management of musculoskeletal pain.7,8 Current evidence suggests that physical therapists can be trained in patient-centered goal setting as part of these programs.9,10 PIPT has shown promising effects for improving persistent pain and physical function in individuals with chronic pain undergoing spine surgery.11–13 One such program developed by Archer et al,11,14 cognitive-behavioral–based physical therapy (CBPT), demonstrated preliminary efficacy for reducing pain and disability and improving general health in a single-site randomized controlled trial in high-risk individuals undergoing spine surgery. The CBPT program was recently tested in a larger multisite trial in a broader population.15 Individuals were randomly assigned after surgery to either a 6-week telephone-based CBPT program or telephone-based education attention control. The CBPT program emphasized patient-centered goal setting along with other cognitive and behavioral strategies to improve physical function and pain outcomes.

As part of the CBPT intervention, individuals set weekly activity/social goals with a physical therapist. Goal attainment of weekly goals using goal attainment scaling (GAS)16 was recorded by the therapist. GAS is a reliable method of scoring how patient-centered goals are achieved and has been used to assess outcomes after rehabilitation.17 Muller et al found associations between rehabilitation goal attainment and improved functioning in postacute populations.18,19 Currently, there is limited evidence on whether patient-centered goal attainment during PIPT programs is associated with improved outcomes in individuals with musculoskeletal pain.

The results of the multisite CBPT trial by Archer et al15 did not show a significant difference in primary outcomes between CBPT or education at 6 or 12 months.15 However, exploration of group differences with program completers showed significant differences between CBPT and education for 12-month disability and physical health. The motivation for the current study, therefore, was to examine whether goal attainment in individuals who engaged with the CBPT program was associated with 6- and 12-month outcomes.

The first objective of this study was to categorize and assess the frequency of patient-centered goals set during the CBPT program. There is direct clinical relevance to knowing the most common types of goals individuals consider meaningful after surgery because this can enhance patient-centered care. The second objective was to examine the relationship between patient-centered goal attainment during the CBPT program and patient-reported outcomes after lumbar spine surgery. We hypothesized that individuals who met their goals as expected would have greater improvements in outcomes at 6 and 12 months after surgery than those who did not meet their goals as expected. Results from this study will be an initial step in exploring whether goal attainment is a potential factor associated with improved patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from a randomized controlled trial comparing postoperative CBPT with an education program in 248 individuals after surgery for a degenerative lumbar spine condition. The randomized controlled trial was conducted in accordance with CONSORT guidelines and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02184143).

As noted above, primary results of the trial were previously reported.15 In the present study, we included primary (disability, pain, and physical and mental health) and secondary (physical function, pain interference) outcomes from the trial.

Participants

The current analysis included 112 participants from the CBPT intervention arm (total number = 124) who completed at least 2 sessions and had available GAS data. The median of CBPT sessions completed by the included cohort was 6 (range = 2–6). The included sample of 112 participants had baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics similar to those of the 12 randomized participants excluded from analyses (P > .05).

CBPT participants underwent a laminectomy with or without fusion for a lumbar degenerative condition at 1 of 2 academic medical centers (Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Johns Hopkins University). Patients randomized to CBPT were ≥21 years of age and English speaking. Individuals undergoing spine surgery for deformity, pseudarthrosis, trauma, infection, or tumor or revision surgery as the primary indication were excluded from the study. Additional exclusion criteria included duration of back or leg pain <3 months, history of neurological disease resulting in moderate to severe movement dysfunction, presence of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, surgery occurring under workers’ compensation, and inability to return to the clinic for standard follow-up visits or to provide a stable address and telephone number. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment and randomization. Ethics approval was obtained by the institutional review boards at the respective sites.

Procedures

Enrolled CBPT participants completed a preoperative intake assessment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Medical comorbidities and surgical information were extracted from the medical record. A baseline assessment was completed 6 weeks after surgery and included validated patient-reported primary outcome measures for disability (Oswestry Disability Index [ODI]), physical and mental health (12-Item Short-Form Health Survey [SF-12]), physical function (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS]), pain interference (PROMIS), and back and leg pain intensity (numeric rating scale). Outcomes of disability, physical and mental health, physical function, pain interference, and pain intensity were reassessed at 6 and 12 months after surgery. All baseline and outcomes data were entered and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture hosted at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Research Electronic Data Capture is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.20

CBPT Intervention

CBPT is a self-management program developed to address fear of movement and low self-efficacy and to promote recovery in individuals with chronic pain and undergoing spine surgery.11,14 CBPT content and strategies were informed by evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapy programs for chronic pain10,21,22 and self-management approaches for older adults.23,24 The CBPT program’s main behavioral strategy was weekly patient-centered goal setting and a graded activity plan. Additional behavioral and cognitive strategies included deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, distraction techniques, automatic thoughts, coping self-statements, pacing techniques, and relapse prevention and symptom management plans. Each CBPT participant received a manual with detailed information and handouts. Participants worked through the manual with a physical therapist over 6 weekly telephone calls starting 6 weeks after surgery. The median duration of the first session call was 46 (interquartile range = 36–55) minutes, and that for the follow-up weekly calls was 23 (interquartile range = 16–30) minutes. Weekly goal setting and GAS were completed by the participant and the physical therapist.

Two study physical therapists (S.W.V. and B.M.) were trained to deliver the CBPT intervention by the senior physical therapist (K.R.A.) and clinical psychologist (S.T.W.) investigators. Details of the therapist training approach are documented in a prior publication.11 Procedures to monitor fidelity of CBPT delivery were implemented and included checklist completion at each session (see Suppl. Appendix 1 for an example of a session 1 checklist) by the therapists and audiotape reviews by the senior investigators (K.R.A. and S.T.W.).

Patient-Centered Goal Setting

At each weekly CBPT session, participants set specific activity goals for the upcoming week. Goals were based on a graded activity plan that the participant completed during the initial session.25 The graded activity plan included a list of meaningful and functional/social activities important to the participant that they were not currently doing (see Suppl. Appendix 2 for an example of a graded activity plan). Within the graded activity plan, activities were listed in hierarchical manner from least to most difficult. Example activities from participants’ graded activity plans included emptying the dishwasher, taking a bath, doing yard work, going out to dinner or a movie, and attending church. Participants could also expand activities to include health care services, such as attending in-person physical therapy or taking medication at a scheduled time. Participants were encouraged to set goals for these functional/social activities, walking, and practicing specific CBPT strategies (ie, deep breathing, distraction).

The study physical therapists guided the participant in setting their most important goals for the week, starting with the least difficult activities on the graded activity plan. Goals were encouraged to follow the SMART framework of being specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time bound.26 For each goal, participants were asked to express their confidence in achieving the goal using a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 was “not confident at all” and 10 was “completely confident.” If a participant rated a goal <8, then the physical therapists encouraged the participant to modify or set a more confident goal and problem solve any barriers to achieving the goal. Confidence is an important component of goal setting and is closely related to self-efficacy (ie, the participant’s belief in their ability to achieve the goal).27 Importantly, the physical therapists used motivational interviewing to help participants set goals, reflect on their confidence scores, and enhance commitment to the goal(s).28 No limit was placed on the number of weekly goals a participant could set.

Goal Attainment Scaling

GAS was used to monitor attainment of each goal set from the previous CBPT session (see Suppl. Appendix 3 for an example of a GAS score form).29 At each follow-up session, the physical therapists reviewed the previous week’s goals with the participant. The physical therapists30 asked the participant to rate the degree to which they met each goal using a 5-point Likert scale. The options included “much less than expected,” “somewhat less than expected,” “as expected,” “somewhat more than expected,” and “much more than expected.” The scale options were scored from −2 (“much less than expected”) to +2 (“much more than expected”). Individual GAS scores were used to compute a t score for each participant that reflected their level of goal attainment across the CBPT program.29 A GAS t score of 50 is interpreted as goals being met, on average, as expected across CBPT sessions. GAS has good interrater reliability and has been validated as an outcome measure in various rehabilitation settings.17,29,31

Outcome Measures

The outcomes for this study were patient-reported disability (ODI), physical and mental health (SF-12), physical function (PROMIS), pain interference (PROMIS), and back and leg pain intensity (numeric rating scale). Outcomes were assessed at 6 weeks (baseline) and 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Disability

Disability was assessed using the 10-item ODI.32 The ODI assesses the degree to which lumbar spine conditions affect everyday activities, such as lifting, walking, and sleeping. Participants rate each item using a 6-point Likert scale. ODI scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher disability. The ODI is a widely used, reliable, and valid measure of disability for low back pain and lumbar spine surgery.33,34

Physical and Mental Health

Physical health and mental health were assessed with the physical component scale and the mental component scale of the SF-12, respectively.35 The SF-12 physical component scale includes subdomains of physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health. The SF-12 mental component scale includes subdomains for vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. For both SF-12 scales, total scores are computed such that higher scores represent higher physical or mental health, and the general population coincides with a mean of 50 and an SD of 10. The SF-12 is a valid measure of physical and mental health in individuals with lumbar spine conditions.36,37

Physical Function and Pain Interference

Physical function and pain interference were assessed using a PROMIS computerized adaptive test. PROMIS computerized adaptive tests have been designed to assess a variety of health domains that contribute to an individual’s overall health.38 PROMIS scores range from 0 to 100, with a score of 50 (SD = 10) representing the general population mean and SD for the United States. Higher scores indicate higher levels of physical function or pain interference.38 PROMIS measures have been shown to be valid and reliable for spine surgery.37,39,40

Back and Leg Pain Intensity

Back and leg pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point numeric rating scale.41,42 Participants were asked to rate their pain, on average, in the past week using a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning “no pain” and 10 meaning “pain as bad as can imagine.” The numeric rating scale for pain intensity has good test-reliability in older adults and individuals with chronic pain.43,44

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the means, SDs, and frequencies of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Participant goals were thematically categorized as follows: activities of daily living, CBPT strategy, exercise, healing, lifestyle, physical/recreational activity, and social (Tab. 1). Categorization was conducted by a single investigator (R.A.C.) in consultation with the investigative team and independently reviewed by the senior physical therapist investigator (K.R.A.). Each goal was included in only 1 category. Subcategories within each thematic category were also generated. We computed the total number of goals set and met, the median goals set per session, and the number and percentage of goals within each type. Participants with GAS t scores ≥ 50 were grouped as “goals met as expected,” whereas participants with t scores < 50 were grouped as “goals not met as expected.”

Table 1.

Goal Categories and Examplesa

| Goal Category | Examples of Goals |

|---|---|

| Activities of daily living | Vacuuming, taking out trash, cooking, doing laundry |

| CBPT strategy | Deep breathing, thinking positively, relaxing |

| Exercise | Attending physical therapy, completing home exercises |

| Healing | Attending doctor’s appointment, using heat or ice |

| Lifestyle | Paying bills, shopping, looking for job |

| Physical/recreational activity | Walking, going up stairs, performing yard work |

| Social | Going to church, getting together with friends |

CBPT = cognitive–behavioral–based physical therapy.

We compared sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between goal attainment groups using independent t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Differences in outcome scores across time points between goal attainment groups were examined using linear mixed-effects regression with fixed effects for group (goals met as expected, goals not met as expected) and time (baseline, 6 months, 12 months) and random intercepts for each participant. Mixed-effects regression has advantages for longitudinal analyses, especially when data are unbalanced and contain missing observations.45 In the current study, complete outcome data were available for 108 participants (96%) at 6 months and 106 participants (95%) at 12 months. All available data were analyzed with mixed-effects regression without dropping cases. The alpha level for statistical significance was set at .05.

Role of the Funding Source

The funder played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of the 112 CBPT participants (mean age = 63.3 [SD = 11.2] years; 51% women) are depicted in Table 2. Sixty-seven CBPT participants (60%) underwent fusion surgery.

Table 2.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics (N = 112)a

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.3 (11.2) |

| Women | 57 (51) |

| White | 96 (86) |

| Some college education or more | 86 (77) |

| Employment status | |

| Working | 41 (37) |

| Retired | 36 (32) |

| Not working because of illness | 32 (29) |

| Not working for other reason | 3 (3) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 32.1 (6.1) |

| Pain duration, mean (SD), mo | 48.2 (87.2) |

| Fusion surgery | 67 (60) |

Data are reported as number (%) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Patient-Centered Goals

CBPT participants set a total of 1395 goals over all sessions. The median number of goals set at each session was 3 (range = 1–6). The median number of goals set by participants across sessions was 13 (range = 1–25). The most common goals set across all sessions were related to physical/recreational activity (36%), CBPT strategy (28%), exercise (11%), and activities of daily living (11%) (Fig. 1). Totals of 110 participants (98%) and 106 participants (95%) set at least 1 physical/recreational activity or CBPT strategy goal during the CBPT program. Fifty-six participants (50%) set an exercise goal during at least 1 CBPT session. The least common goals were related to social activities (2%), with only 20 participants (18%) setting a social goal at any session. Common specific goals set across sessions were related to walking (29%), deep breathing (13%), relaxation (9%), physical therapy/gym/home exercise (7%), and cleaning (7%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of goals set within each goal category. CBPT = cognitive-behavioral–based physical therapy; PT = physical therapy.

Goal Attainment Groups

Forty-eight participants (43%) met goals as expected (GAS t scores of ≥50), and 64 (57%) did not. There were no differences in baseline sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between groups, except for current working status and baseline leg pain intensity (Tab. 3). Participants who met goals as expected included a higher proportion of working individuals (50% vs 27%; P < .05), reported lower leg pain intensity (mean rating = 1.7 [SD = 2.3] vs 2.7 [SD = 2.4]; P < .05), and met a higher percentage of their goals (mean percentage of goals met = 85.8 [SD = 12.8] vs 63.2 [SD = 17.5]; P < .05).

Table 3.

Comparison of High and Low Goal Attainment Groupsa

| Variable | Goals Met as Expected (n = 48) | Goals Not Met as Expected (n = 64) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 64.0 (10.1) | 62.8 (12.0) | .59 |

| Womenb | 20 (42) | 37 (58) | .09 |

| Whiteb | 42 (88) | 54 (84) | .64 |

| Some college education or moreb | 40 (83) | 46 (72) | .16 |

| Employment statusb | <.05 | ||

| Working | 24 (50) | 17 (27) | |

| Retired | 17 (35) | 19 (30) | |

| Not working because of illness | 6 (13) | 26 (41) | |

| Not working for other reason | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.2 (5.2) | 32.9 (6.6) | .15 |

| Pain duration, mo | 52.6 (116.0) | 44.9 (57.7) | .65 |

| Fusion surgeryb | 30 (63) | 37 (58) | .77 |

| Baseline outcome scores | |||

| Disability, ODI | 28.8 (18.7) | 34.4 (18.4) | .12 |

| Physical health, SF-12 | 33.0 (10.8) | 32.8 (9.9) | .91 |

| Mental health, SF-12 | 53.4 (12.2) | 50.7 (10.6) | .20 |

| Physical function, PROMIS | 38.3 (8.4) | 37.7 (8.4) | .68 |

| Pain interference, PROMIS | 55.7 (10.8) | 58.9 (9.2) | .09 |

| Back pain intensity, NRS | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.5 (2.7) | .15 |

| Leg pain intensity, NRS | 1.7 (2.3) | 2.7 (2.4) | <.05 |

| Patient-centered goals | |||

| Total no. of goals set | 11.5 (5.6) | 13.3 (5.4) | .10 |

| Total no. of goals met | 9.8 (4.7) | 8.6 (4.3) | .15 |

| % of total goals met | 85.8 (12.8) | 63.2 (17.5) | <.05 |

Data are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. NRS = numeric rating scale; ODI = Oswestry Disability Index; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SF-12 = 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

Reported as number (%) of participants.

Differences in Outcomes Based on Goal Attainment

In the mixed-effects regression, there was a significant group × time interaction for physical function (P < .05) (Tab. 4; Fig. 2), indicating greater improvement from baseline to 6 months (estimate = 3.7; 95% CI = 1.0 to 6.5) and 12 months (estimate = 2.8; 95% CI = 0.04 to 5.6) in participants who met goals as expected than in participants who did not meet goals as expected. A significant interaction was not observed for disability, physical or mental health, pain interference, back pain intensity, or leg pain intensity (P > .05).

Table 4.

Summary Results From Linear Mixed-Effects Regressiona

| Variable | Disability | Physical Health | Mental Health | Physical Function | Pain Interference | Back Pain Intensity | Leg Pain Intensity | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | Est | 95% CI | P | |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 34.4 | 30.0 to 38.9 |

<.05 | 32.8 | 29.9 to 35.7 | <.05 | 50.7 | 48.3 to 53.1 | <.05 | 37.7 | 35.7 to 39.7 | <.05 | 58.7 | 56.3 to 61.1 | <.05 | 3.5 | 2.9 to 4.1 | <.05 | 2.7 | 2.1 to 3.3 | <.05 |

| Group | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Goals met as expected | −5.6 | −12.4 to 1.2 | .11 | 0.2 | −4.2 to 4.6 | .92 | 2.8 | −0.9 to 6.4 | .14 | 0.6 | −2.4 to 3.7 | .68 | −2.9 | −6.6 to 0.7 | .12 | −0.7 | −1.6 to 0.2 | .13 | −0.9 | −1.9 to −0.03 | <.05 |

| Time | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 mo | −7.5 | −11.1 to −4.0 | <.05 | 5.1 | 2.6 to 7.7 | <.05 | 2.4 | −0.1 to 4.9 | .06 | 2.6 | 0.9 to 4.4 | <.05 | −3.4 | −5.5 to −1.4 | <.05 | −0.3 | −0.8 to 0.2 | .26 | −0.1 | −0.7 to 0.6 | .89 |

| 12 mo | −8.2 | −11.8 to −4.7 | <.05 | 4.8 | 2.2 to 7.4 | <.05 | 1.5 | −1.0 to 4.0 | .24 | 3.4 | 1.6 to 5.2 | <.05 | −4.0 | −6.0 to −1.9 | <.05 | −0.1 | −0.6 to 0.5 | .83 | 0.2 | −0.5 to 0.8 | .64 |

| Group × time | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Goals met as expected in 6 mo | −0.9 | −6.3 to 4.4 |

.73 | 2.8 | −1.1 to 6.7 | .16 | −0.02 | −3.8 to 3.8 | .99 | 3.7 | 1.0 to 6.5 | <.05 | −0.3 | −3.5 to 2.8 | .85 | −0.2 | −1.0 to 0.7 | .72 | 0.1 | −0.9 to 1.0 | .85 |

| Goals met as expected in 12 mo | −0.8 | −6.2 to 4.6 |

.77 | 3.6 | −0.4 to 7.6 | .08 | 1.4 | −2.4 to 5.2 | .47 | 2.8 | 0.04 to 5.6 | <.05 | −0.5 | −3.7 to 2.7 | .76 | −0.5 | −1.3 to 0.4 | .27 | 0.04 | −0.9 to 1.0 | .94 |

| Random effects | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Residual variance (SD) | 100.1 (10.0) | 53.6 (7.3) | 49.4 (7.0) | 26.1 (5.1) | 33.5 (5.8) | 2.3 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.8) | ||||||||||||||

| ICC | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||

Est = estimate; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

Figure 2.

Baseline, 6-month, and 12-month mean outcome scores by goal attainment. Error bars are 95% CIs. *Significant outcome difference between groups. NRS = numeric rating scale; ODI = Oswestry Disability Index; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SF-12 = 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

Discussion

Patient-centered goal setting is an essential component within rehabilitation for patients with chronic pain. Understanding the most common types of goals patients set can assist clinicians in directing meaningful therapeutic strategies. In the current study, we found that participants often prioritized goals related to physical/recreational activity, use of CBPT strategies, exercise, and activities of daily living. Participants who met goals as expected throughout the CBPT program reported better physical function at 6 and 12 months. We did not observe differences over time between groups for disability, physical or mental health, pain interference, or pain intensity. These data suggest patient-centered goal setting using the GAS may be an important strategy of PIPT programs for improving physical function.

There are several notable comparisons to previous studies describing patient-centered goals for individuals with lumbar spine conditions. In a study of individuals with acute back pain undergoing therapy, Mullis et al46 classified the top 5 most frequent type of goals as recreation/leisure (28%), walking (19%), caring for household objects (17%), doing housework (11%), and remunerative employment (8%). In the current study, occupational goals were categorized within our Lifestyle category and represented a very low percentage of overall goals set by participants (<1%). This may relate to differences in sociodemographics in the sample conditions (eg, acute nonspecific back pain in Mullis et al46 vs degenerative spine conditions requiring surgery in the current study). Participants in the current study were also older (average age of 65 years) than those in the study by Mullis et al46 (average age of 50 years), and a significant proportion of participants in the current sample (32%) were retired.

For chronic back pain, Gardner et al47 reported that physical activity (49%) was overwhelmingly the most common type of goal set, followed by workplace (14%), coping skills (11%), relationships (6%), and sleep/energy (6%). Similarly, Heapy et al48 found that physical activity (29%) was the most common goal category, followed by functional status (25%), wellness (16%), recreational activities (11%), house/yard work (10%), socializing (7%), and work/school (2%). Direct comparison of chronic back pain goal categories is difficult because of differences in the way specific goal activities were categorized. For example, in some studies, physical activity included exercise, whereas other studies distinguished among the activities of walking, recreation, or house/yard work. Nevertheless, physical/recreational activities and exercise make up the most common goals for individuals. Social goals were less frequently expressed by participants but often included goals for attending church, holiday, or sporting events or having important conversations with family and friends. The low proportion of social goals may reflect the fact that most of our participants maintained their social relationships or engagement after surgery. There may be a need to further examine the influence of social goal attainment within PIPT interventions in select individuals who report loneliness, isolation, withdrawal, feeling disconnected from others, or disrupted roles and responsibilities.49,50

A lower proportion of participants in our sample met goals as expected (43%) compared with the results of Mannion et al,51 who found that 65% of participants who had chronic back pain and completed physical therapy had GAS t scores ≥ 50. Comparison of individuals who met goals as expected and those who did not meet goals as expected was not performed by Mannion et al.51 We found few baseline differences between goal attainment groups. As expected, participants who met goals as expected met a higher percentage of their goals. This result was due to a combination of slightly more goals met and fewer goals set across sessions. To our knowledge, there is no standard for the optimal number of patient-centered goals to enhance attainment. A potential clinical impact of this finding may be that setting fewer patient-centered goals within a SMART framework is preferred. Importantly, all goals set in the CBPT program required a high level of confidence for attainment by the participant. Fewer goals set may allow individuals to dedicate greater effort and time during the week to trying to accomplish what they desire most.

Few studies have examined associations between goal attainment and patient-reported outcomes. Mannion et al51 found higher goal attainment was associated with greater change in pain and disability after exercise-based physical therapy. Regarding a cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention, Heapy et al48 found a significant association between goal achievement and posttreatment pain interference and intensity, which contrasts with the current study. We did not find support that goal attainment was associated with common primary outcome measures used in spine surgery intervention studies. These inconsistent findings could relate to lower levels of baseline disability and pain in our population or the overall physical function and activity focus of the CBPT program. Relatively higher baseline pain levels (considered “moderate” pain) were reported in the nonoperative studies by Mannion et al51 and Heapy et al.48 Baseline scores in our CBPT participants reflected “low” pain levels, on average, that were likely reduced by spine surgery. Additionally, CBPT therapists were encouraged to help participants focus primarily on physical function recovery as opposed to pain reduction. Although there is potential overlap in outcome measures used in this study, the clinical relevance of our finding may relate to optimal postoperative outcome assessment and which measures to assess in therapy. Physical function, as measured with a tool such as PROMIS, may be an appropriate construct informing postoperative rehabilitation progress and should be considered alongside measures of disability and pain. Further, physical function is part of recommended core outcome domains for back pain.52

Our study has important clinical considerations for physical therapists working with individuals after lumbar spine surgery. Previous qualitative work has reported on variability in patient-centered goal-setting practices of physical therapists and potential barriers.4–6 Our study outlines 1 standard way in which physical therapists could approach goal setting using a graded activity plan and GAS. To address potential issues with clinical time, a graded activity plan handout (Suppl. Appendix 2) could be offered to individuals to complete at home before the next visit. This would give individuals time to identify meaningful activities and reduce interference with usual physical therapy procedures. At the next visit, the physical therapist could thank the individual for completing the graded activity plan and start the goal-setting conversation around the least difficult activity. The therapist could gauge the individual’s confidence level for attaining their goal using a confidence scale (0–10) and revisit a goal if confidence is low (<8 out of 10). A discussion on possible ways the individual can manage barriers to goal attainment could also be helpful.

This discussion could occur while individuals are engaged in other active or passive clinical procedures. The therapist could consider having the individual write down their goals to increase likelihood of goal attainment. Specific goals set by individuals can be documented along with the patient’s confidence score (Suppl. Appendix 3). During GAS assessment, therapists could assess the individual’s level of goal attainment for each goal set. Individual goal scores ≥0 would inform therapists that the individual’s goals are being attained as expected. In situations where individuals are not achieving their individual goals as expected, therapists could revisit the individual’s goals and discuss ways to enhance attainment.

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations of our study. Our GAS process was modified for application within our CBPT program. For example, we did not weight each goal for difficulty or importance or obtain baseline scaling parameters for goals. Our use of GAS scores was limited to “postassessment” only and did not include goal score change. We focused our primary analyses on the effect of goal attainment on our patient-reported outcomes. We did not have a priori hypotheses regarding potential factors that could influence this relationship. Future work should explore confounders, moderators, or mediators of the association between goal attainment and outcome.

In conclusion, monitoring goal attainment progress at subsequent visits is an essential part of PIPT.53 Our study found that individuals express a variety of goals within a CBPT program, with common activities including daily walking, exercise, and use of PIPT strategies such as deep breathing, relaxation, and engaging in enjoyable activities. Social activity goals were not commonly reported. Fewer meaningful goals seem to be preferred in the postoperative setting. The attainment of patient-centered goals may be an important rehabilitation component related to improvements in physical functioning after spine surgery.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: R.A. Coronado, H. Master, J.S. Pennings, S.W. Vanston, S.T. Wegener, K.R. Archer

Writing: R.A. Coronado, H. Master, J.A. Bley, P.E. Robinette, E.K. Sterling, R.L. Skolasky, K.R. Archer

Data collection: M.T. O’Brien, B. Myczkowski, R.L. Skolasky, K.R. Archer

Data analysis: R.A. Coronado, H. Master, J.A. Bley, E.K. Sterling, A.L. Henry, J.S. Pennings

Project management: R.A. Coronado, R.L. Skolasky, K.R. Archer

Fund procurement: K.R. Archer

Providing participants: R.L. Skolasky

Providing facilities/equipment: R.L. Skolasky, S.T. Wegener

Providing institutional liaisons: R.L. Skolasky

Clerical/secretarial support: B. Myczkowski

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): J.S. Pennings, B. Myczkowski, R.L. Skolasky, S.T. Wegener, K.R. Archer

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained by the institutional review boards at the respective sites.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI, CER-1306-01970) and Foundation for Physical Therapy Research and by a CTSA award (UL1TR000445 UL1TR000445) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr Coronado also was supported by a Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Research Scholars award (KL2TR002245 KL2TR002245) during manuscript development.

Clinical Trial Registration

The randomized controlled trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02184143).

Disclosures and Presentations

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

A portion of this study was presented at the American Physical Therapy Association’s Combined Sections Meeting, February 12–15, 2020, in Denver, Colorado, USA; at the North American Spine Society Annual Meeting, September 30, 2021 (virtual); and at the PROMIS International Conference, October 17–18, 2021 (virtual).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Rogelio A Coronado, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Osher Center for Integrative Health, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Hiral Master, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Jordan A Bley, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Payton E Robinette, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Emma K Sterling, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Michael T O’Brien, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Abigail L Henry, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Jacquelyn S Pennings, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Susan W Vanston, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Brittany Myczkowski, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Richard L Skolasky, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Stephen T Wegener, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Kristin R Archer, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Osher Center for Integrative Health, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

References

- 1. Tryon GS, Winograd G. Goal consensus and collaboration. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2011;48:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd A, Roberts AR, Freeman JA. ‘Finding a balance’ in involving patients in goal setting early after stroke: a physiotherapy perspective. Physiother Res Int. 2014;19:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cameron LJ, Somerville LM, Naismith CE, Watterson D, Maric V, Lannin NA. A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:827–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parry RH. Communication during goal-setting in physiotherapy treatment sessions. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:668–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schoeb V. “The goal is to be more flexible”--detailed analysis of goal setting in physiotherapy using a conversation analytic approach. Man Ther. 2009;14:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schoeb V, Staffoni L, Parry R, Pilnick A. “What do you expect from physiotherapy?”: a detailed analysis of goal setting in physiotherapy. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1679–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keefe FJ, Main CJ, George SZ. Advancing psychologically informed practice for patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: promise, pitfalls, and solutions. Phys Ther. 2018;98:398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Phys Ther. 2011;91:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall A, Richmond H, Copsey B, et al. Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:1–9. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1236155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keefe FJ, Dunsmore J, Burnett R. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to chronic pain: recent advances and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Archer KR, Devin CJ, Vanston SW, et al. Cognitive-behavioral-based physical therapy for patients with chronic pain undergoing lumbar spine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2016;17:76–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lotzke H, Brisby H, Gutke A, et al. A person-centered prehabilitation program based on cognitive-behavioral physical therapy for patients scheduled for lumbar fusion surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1069–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, et al. Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Archer KR, Motzny N, Abraham CM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral-based physical therapy to improve surgical spine outcomes: a case series. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1130–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Archer KR, Haug CM, Pennings J. Comparing Two Programs to Improve Disability, Pain, and Health Among Patients Who Have Had Back Surgery. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); 2020. 10.25302/04.2020.CER.130601970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J. 1968;4:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurn J, Kneebone I, Cropley M. Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:756–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kus S, Muller M, Strobl R, Grill E. Patient goals in post-acute geriatric rehabilitation: goal attainment is an indicator for improved functioning. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muller M, Strobl R, Grill E. Goals of patients with rehabilitation needs in acute hospitals: goal achievement is an indicator for improved functioning. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Philips C. The Psychological Management of Chronic Pain: a Treatment Manual. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. In: Loeser JD, ed., Bonica's Management of Pain. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001: 1751–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lorig K, Holman H. Arthritis self-management studies: a twelve-year review. Health Educ Q. 1993;20:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39:1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanders S, Operant treatment. Back to basics. In: Turk DC, Gatchel RJ, eds., Psychological Approaches to Pain Management: a Practitioner’s Handbook. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002: 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poulsen AA, Ziviani J, Kotaniemi K, Law M. ‘I think I can’: measuring confidence in goal pursuit. Brit J Occup Ther. 2014;77:64–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krasny-Pacini A, Hiebel J, Pauly F, Godon S, Chevignard M. Goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation: a literature-based update. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;56:212–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pangarkar SS, Kang DG, Sandbrink F, et al. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2620–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fisher K, Hardie RJ. Goal attainment scaling in evaluating a multidisciplinary pain management programme. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2940–2953, discussion 2952. 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2002;82:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pratt RK, Fairbank JC, Virr A. The reliability of the Shuttle Walking Test, the Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire, the Oxford Spinal Stenosis Score, and the Oswestry Disability Index in the assessment of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luo X, George ML, Kakouras I, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the short form 12-item survey (SF-12) in patients with back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:1739–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee CE, Browell LM, Jones DL. Measuring health in patients with cervical and lumbosacral spinal disorders: is the 12-item short-form health survey a valid alternative for the 36-item short-form health survey? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:829–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rubery PT, Houck J, Mesfin A, Molinari R, Papuga MO. Preoperative PROMIS scores assist in predicting early postoperative success in lumbar discectomy. Spine. 2019;44:325–333. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boody BS, Bhatt S, Mazmudar AS, Hsu WK, Rothrock NE, Patel AA. Validation of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) computerized adaptive tests in cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28:268–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patel AA, Dodwad SM, Boody BS, et al. Validation of patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) computer adaptive tests (CATs) in the surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43:1521–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. What is the maximum number of levels needed in pain intensity measurement? Pain. 1994;58:387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herr KA, Spratt K, Mobily PR, Richardson G. Pain intensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993;55:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT. Linear Mixed Models: a Practical Guide Using Statistical Software. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2007. 10.1201/9781420010435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mullis R, Lewis M, Hay EM. What does minimal important change mean to patients? Associations between individualized goal attainment scores and disability, general health status and global change in condition. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, Goodall S, Hubscher M, Smith L. Patient led goal setting in chronic low back pain-what goals are important to the patient and are they aligned to what we measure? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1035–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Heapy AA, Wandner L, Driscoll MA, et al. Developing a typology of patient-generated behavioral goals for cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain (CBT-CP): classification and predicting outcomes. J Behav Med. 2018;41:174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Karayannis NV, Baumann I, Sturgeon JA, Melloh M, Mackey SC. The impact of social isolation on pain interference: a longitudinal study. Ann Beha Med. 2019;53:65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sturgeon JA, Dixon EA, Darnall BD, Mackey SC. Contributions of physical function and satisfaction with social roles to emotional distress in chronic pain: a Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR) study. Pain. 2015;156:2627–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mannion AF, Caporaso F, Pulkovski N, Sprott H. Goal attainment scaling as a measure of treatment success after physiotherapy for chronic low back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1734–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH task force on research standards for chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2014;15:569–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harkin B, Webb TL, Chang BP, et al. Does monitoring goal progress promote goal attainment? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:198–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.