Abstract

Objectives

It is likely that the number of older adults who eat alone has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Older adults who eat alone tend to experience weight fluctuations. Weight loss and underweight in older adults cause health problems. The study objective was to longitudinally investigate the association between changes in eating alone or with others and body weight status in older adults.

Methods

This longitudinal cohort study was conducted in March and October 2020 in Minokamo City, Gifu Prefecture, Japan. Questionnaire data for 1071 community-dwelling older adults were analyzed. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed using changes in eating alone or with others as the independent variable and body weight status as the dependent variable. The analysis was adjusted for age, sex, living arrangements, educational level, diseases receiving medical treatment, cognitive status, depression, and instrumental activities of daily living. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation.

Results

The average age of participants was 81.1 y (SD, 4.9 y). Individuals who reported eating alone in both surveys were more likely to report weight loss than those who reported eating with others in both surveys (adjusted model: odds ratio, 2.25; 95% confidence interval, 1.06–4.78; P = 0.04).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that measures to prevent weight loss in older adults who eat alone are particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Body mass index; Eating together, Japan, Nutrition, Underweight, Weight loss

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted substantial lifestyle changes. Under Japan's national and prefectural policy to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the population has received multiple requests to refrain from outings, leisure, and travel activities. Although these requests have not included lockdowns as strict as those implemented in other countries, many people have experienced reductions in social interaction, including eating with others [1].

There is considerable global interest in the tendency of older adults in aging societies to eat alone [2]. In Japan, both the number of older adults and the number of older adults who eat alone are increasing, which is problematic [3]. Eating alone can lead to health problems in older adults, particularly in older adults who live with others but eat alone and in those with depression [4]. This is partly because such older adults have a low food intake and poorly balanced meals [5]. The resulting insufficient nutrition and weight loss cause various health problems, such as a higher mortality [4], [5], [6], [7]. Weight loss (even if subjective) is associated with increasing frailty and higher mortality [8,9]. Underweight resulting from weight loss is also associated with increased mortality [6]. Moreover, weight loss, rather than muscle mass loss, may reduce quality of life [10] and thus is an important health-related factor in older adults.

Strategies to promote the health of older adults who eat alone should therefore address weight loss. Weight fluctuation can be measured and checked on a routine basis. Therefore, clarifying the relationship between eating alone or eating together and weight fluctuation can demonstrate the importance of weight management to older adults who eat alone and can generate valuable data for health promotion strategies in this population. Monitoring eating behavior is important during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to a reduction in social interaction [1].

Most studies of older adults who eat alone are cross-sectional studies, and there are few longitudinal studies on weight fluctuation in older adults [11]. Moreover, it remains unclear how changes in eating alone or together, such as the shift from eating with others to eating alone, affect weight fluctuation. Furthermore, the effect of eating alone on weight fluctuation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic is unknown. The effect of eating alone on weight loss is a concern because of the current pandemic-related restrictions on social interactions, including eating with others.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to longitudinally investigate the association of changes in eating alone or together with body weight status in older adults. We hypothesized that older adults who transitioned from eating with others to eating alone or who continued to eat alone would have poorer body weight status than those who ate with others.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a longitudinal cohort study. Data were collected using two mail surveys. Self-administered questionnaires were mailed to respondents, who were asked to return them after completion. No survey reminders were sent. Only respondents who returned the survey were included in the study.

The baseline survey comprised the “survey of needs in spheres of daily life” for care prevention formulated by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [12] in March 2020, before the declaration of a state of emergency in response to the first COVID-19 wave. After the baseline survey, a nationwide request was declared to restrict various activities from April 16, 2020, to May 25, 2020, to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and prefecture-level requests were declared to restrict various activities from July 31 to August 31, 2020, in the survey areas. A follow-up survey was conducted on October 2020 after the requests to restrict various activities were lifted. In addition to the factors assessed in the baseline survey, the follow-up survey investigated life changes prompted by COVID-19.

This survey was conducted in Minokamo City, Gifu Prefecture, Japan. Minokamo is located in the central and southern part of Gifu prefecture and is a wealthy city with a thriving industry. As of April 1, 2021, the population of the city was 57 171, the population density was 1 270.18 persons per square kilometer of habitable area, and the population included 13 226 individuals (23.13%) aged 65 y or older.

Participants

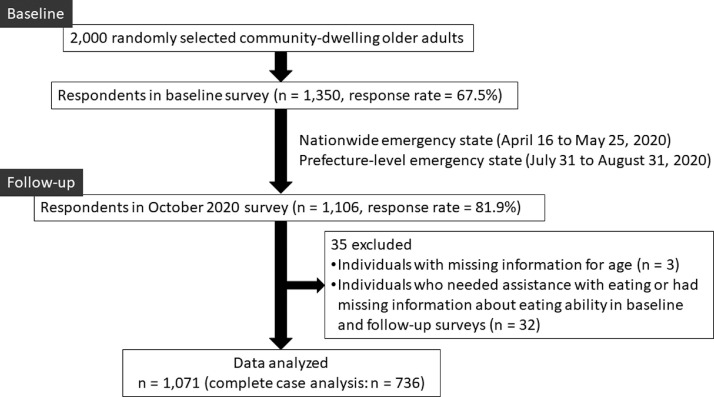

The participants of the baseline survey were 2000 randomly selected, community-dwelling older adults (aged ≥65 y) not certified as having long-term care needs. Of these, 1350 respondents (response rate: 67.5%) participated in the follow-up survey. In the follow-up survey, 1106 older adults responded (response rate: 81.9%). Of these, respondents with missing information about age were excluded. In addition, respondents who needed assistance with eating or had missing information about eating ability in the baseline and follow-up surveys were excluded. Finally, data from 1071 individuals were analyzed (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

Measures

Eating alone

Eating alone was assessed using the question, “Do you have the opportunity to eat with someone?” This question is used in the survey of needs in spheres of daily life as an indicator of eating alone. The question had five response options: every day, several times a week, several times a month, several times a year, or none. Previous studies have defined “eating together” as eating with someone at least once a day [13]. Therefore, we categorized, every day as “eating with others” and categorized all other responses as “eating alone.” In the two surveys, changes in eating alone or together were categorized as “eating alone” (eating alone at both survey points), “shift to eating with others” (eating alone at the baseline survey to eating with others at the follow-up survey), “shift to eating alone” (eating with others at the baseline survey to eating alone at the follow-up survey), and “eating with others” (eating with others at both survey points).

Body weight status

Body weight status was assessed using the body mass index (BMI) and weight loss in the past 6 mo. The BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight in both baseline and follow-up surveys. A BMI <20.0 kg/m2 was defined as underweight [6]. We focused on underweight as defined by BMI, not BMI itself, because underweight has greater negative effects on the health status of older adults than does obesity [6]. Underweight was categorized in terms of underweight at both survey points, shift from underweight to non-underweight, shift from non-underweight to underweight, and non-underweight at both survey points.

Weight loss in the past 6 mo was assessed using the question, “Has your weight declined by 2–3 kg or more in the last 6 mo?” Possible responses were yes or no. This question is frequently used as an assessment of weight fluctuation and is associated with reduced frequency of balanced-meal consumption and food intake [14,15]. The presence or absence of weight loss in the two surveys was categorized in terms of four groups: presence of weight loss at both survey points, shift from presence to absence of weight loss, shift from absence to presence of weight loss, and absence of weight loss at both survey points.

Covariates

Data on demographic characteristics, cognitive status, depression, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) were obtained from the baseline survey, and these variables were used as covariates. Demographic data comprised age, sex, living arrangements (living alone or living with others), and educational level (6–9 y, 10–12 y, or ≥13 y of education). Cognitive status was assessed as self-awareness of forgetfulness (possible responses were yes or no). Depression was defined as affirmative answers to either of the following questions [16]: “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” Instrumental ADLs were assessed using a subscale of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence [17]. This subscale consists of the following five questions: “Can you use public transportation (bus or train) by yourself?”, “Are you able to shop for daily necessities?”, “Are you able to prepare meals by yourself?”, “Are you able to pay bills?”, and “Can you handle your own banking?” Negative responses to any one of these questions was defined as IADL disability [18].

Data analysis

First, the data for each measure were examined using descriptive statistics. Baseline and follow-up survey data on eating alone or with others were compared using the χ2 test. Then, multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the effects of and changes in eating alone or with others on body weight status. Changes in eating alone or with others composed the independent variable, and body weight status was the dependent variable. Two models were generated: a crude model and an adjusted model. The latter model was adjusted for age, sex, living arrangements, educational level, cognitive status, depression, and IADLs. In the analysis, the reference was eating with others. In addition, to confirm the robustness of the results of the analysis of self-perceived weight loss, we conducted a similar analysis of differences in self-reported weight between the two surveys.

In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, multiple imputation using chained equations was performed for missing data; following previous recommendations, 20 imputed data sets were created [19]. Before performing multiple imputation, Little's missing completely at random test was used. The results confirmed that the missing data were not missing completely at random (P < 0.01).

In addition, complete cases and individuals with missing data were compared using the t test and χ2 test. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed using complete case data as a sensitivity analysis.

SPSS Statistics, version 24.0 for Microsoft Windows (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan), was used for all analyses. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the research ethics committee of Seijoh University (approval number: 2020 C0013). Participants received the study questionnaire together with an explanation of the study purpose and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Completion of the questionnaire was considered to constitute informed consent.

Results

The demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 . The average age of the participants analyzed was 81.1 y (SD, 4.9 y). Of the 1071 participants analyzed, 495 (46.2%) were men. Regarding eating alone or with others, 448 individuals (41.8%) reported eating alone at the baseline survey, and 522 (48.7%) reported eating alone at the follow-up survey (48.7%) (P < 0.01; data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n = 1071)

| Mean or No. | SD or % | Missing, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 81.1 | 4.9 | 0 (0.0) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 495 | 46.2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Living alone. No. (%) | 140 | 13.1 | 56 (5.2) |

| Educational level, No. (%) | |||

| 6–9 y | 449 | 41.9 | 15 (1.4) |

| 10–12 y | 439 | 41.0 | |

| ≥13 y | 168 | 15.7 | |

| Eating alone, No. (%) | |||

| Baseline | 448 | 41.8 | 76 (7.1) |

| Follow-up | 522 | 48.7 | 14 (1.3) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 22.2 | 3.5 | 40 (3.7) |

| Follow-up | 22.0 | 2.9 | 37 (3.5) |

| 2–3 kg weight loss in past 6 mo, No. (%) | |||

| Baseline | 93 | 8.7 | 92 (8.6) |

| Follow-up | 159 | 14.8 | 40 (3.7) |

| Self-awareness of forgetfulness, No. (%) | 463 | 43.2 | 24 (2.2) |

| Depression, No. (%)* | 393 | 36.7 | 84 (7.8) |

| No instrumental activities of daily living disability, No. (%)† | 119 | 11.1 | 40 (3.7) |

The presence of depression was defined as affirmative answers to either of the following questions: “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?”

The presence of an instrumental activities of daily living disability was defined as a score <5 on a subscale of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence

Regarding changes in eating alone or with others, 339 participants reported eating alone at both survey points, 104 individuals changed from eating alone to eating with others, 143 changed from eating with others to eating alone, and 399 reported eating with others at both survey points. Table 2 shows demographic characteristics by eating alone/together.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics by eating alone or together

| Eating alone → eating alone (n = 339) | Eating alone → eating with others (n = 104) | Eating with others → eating alone (n = 143) | Eating with others → eating with others (n = 399) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing, No. (%) | Missing, No. (%) | Missing, No. (%) | Missing, No. (%) | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 81.9 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 80.8 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 81.1 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 80.4 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 139 (41.0) | 0 (0.0) | 55 (52.9) | 0 (0.0) | 73 (51.0) | 0 (0.0) | 188 (47.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Living alone, No. (%) | 116 (34.2) | 15 (4.4) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (3.8) | 3 (2.1) | 9 (6.3) | 4 (1.0) | 20 (0.5) |

| Educational level, No. (%) | ||||||||

| 6–9 y | 173 (51.0) | 6 (1.8) | 41 (39.4) | 2 (1.9) | 59 (41.3) | 0 (0.0) | 147 (36.8) | 5 (1.3) |

| 10–12 y | 118 (34.8) | 43 (41.3) | 57 (39.9) | 181 (45.4) | ||||

| ≥13 y | 42 (12.4) | 18 (17.3) | 27 (18.9) | 66 (16.5) | ||||

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | ||||||||

| Baseline | 22.2 (3.7) | 9 (2.7) | 21.7 (2.6) | 3 (2.9) | 22.2 (3.1) | 4 (2.8) | 22.3 (3.7) | 11 (2.8) |

| Follow-up | 22.0 (2.8) | 16 (4.7) | 21.8 (2.6) | 5 (4.8) | 22.0 (2.7) | 4 (2.8) | 22.2 (3.0) | 6 (1.5) |

| Presence of underweight, No. (%) * | ||||||||

| Baseline | 78 (23.0) | 9 (2.7) | 20 (19.2) | 3 (2.9) | 41 (28.7) | 4 (2.8) | 94 (23.6) | 11 (2.8) |

| Follow-up | 75 (22.1) | 16 (4.7) | 22 (21.2) | 5 (4.8) | 42 (29.4) | 4 (2.8) | 97 (24.3) | 6 (1.5) |

| Presence of weight loss, No. (%)† | ||||||||

| Baseline | 41 (12.1) | 14 (4.1) | 13 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (8.4) | 1 (0.7) | 25 (6.3) | 11 (2.8) |

| Follow-up |

68 (20.1) | 17 (5.0) | 10 (9.6) | 5 (4.8) | 18 (12.6) | 5 (3.5) | 47 (11.8) | 10 (2.5) |

| Presence of self-awareness of forgetfulness, No. (%) | 166 (49.0) | 3 (0.9) | 47 (45.2) | 1 (1.0) | 62 (43.4) | 1 (0.7) | 155 (38.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Presence of depression, No. (%)‡ | 137 (40.4) | 24 (7.1) | 31 (29.8) | 8 (7.7) | 51 (35.7) | 8 (5.6) | 140 (35.1) | 30 (7.5) |

| Presence of instrumental activities of daily living disability, No. (%)§ | 31 (9.1) | 16 (4.7) | 14 (13.5) | 2 (1.9) | 19 (13.3) | 9 (6.3) | 45 (11.3) | 5 (1.3) |

Underweight was defined as a body mass index <20.0 kg/m2

The presence of weight loss was defined as 2–3 kg of weight loss in the past 6 months

The presence of depression was defined as affirmative answers to either of the following questions: “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?”

The presence of instrumental activities of daily living disability was defined as a score <5 on a subscale of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology Index of Competence

The results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis are shown in Tables 3 and 4 . Participants who ate alone were more likely to report weight loss than were those who ate with others (crude model: odds ratio (OR), 2.36; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.18–4.73; P = 0.01; adjusted model: OR, 2.25, 95% CI, 1.06–4.78; P = 0.04). However, the prevalence of underweight (as defined by BMI) was not associated with eating alone or together. Analysis of differences in self-reported weight showed that eating alone tended to be associated with weight loss, but the effect was not significant (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3.

Effects of changes in eating alone or together on body mass index changes: Multinomial logistic regression analysis (n = 1071)

| OR (95% CI) for body mass index changes |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight* → underweight |

Underweight → non-underweight |

Non-underweight → underweight |

Non-underweight → non-underweight |

||||||||||||||

| Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Eating alone → eating alone | 1.12 | 0.77–1.61 | 1.06 | 0.68–1.65 | 1.46 | 0.66–3.25 | 0.86 | 0.31–2.36 | 1.83 | 0.82–4.09 | 1.61 | 0.65–4.02 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | |||||||||||||||||

| Eating alone → eating with others | 1.00 | 0.56–1.76 | 1.05 | 0.59–1.88 | 1.22 | 0.39–3.80 | 1.27 | 0.40–4.00 | 2.39 | 0.90–6.34 | 2.38 | 0.89–6.35 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | |||||||||||||||||

| Eating with others → eating alone | 1.02 | 0.60–1.73 | 1.04 | 0.61–1.78 | 1.85 | 0.75–4.58 | 1.85 | 0.73–4.65 | 2.01 | 0.74–5.45 | 1.87 | 0.68–5.13 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | |||||||||||||||||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

None of the associations in the table were significant; the adjusted model adjusted for age, sex, living arrangements, educational level, cognitive status, depression, and instrumental activities of daily living

Underweight was defined as a body mass index <20.0 kg/m2

Table 4.

Effects of changes in eating alone or together on weight loss: Multinomial logistic regression analysis (n = 1071)

| OR (95% CI) for body weight changes |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence* → presence |

Presence → absence |

Absence → presence |

Absence → absence |

|||||||||||||

| Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

Crude model |

Adjusted model |

|||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Eating alone → eating alone | 2.36 | 1.18–4.73† | 2.25 | 1.06–4.78† | 2.28 | 1.03–5.04† | 1.80 | 0.72–4.52 | 2.02 | 1.23–3.29‡ | 1.59 | 0.90–2.77 | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | ||||||||||||||||

| Eating alone → eating with others | 1.45 | 0.52–4.04 | 1.53 | 0.54–4.35 | 2.52 | 0.95–6.69 | 2.38 | 0.88–6.45 | 0.61 | 0.23–1.63 | 0.60 | 0.22–1.59 | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | ||||||||||||||||

| Eating with others → eating alone | 1.30 | 0.50–3.38 | 1.23 | 0.46–3.27 | 1.58 | 0.58–4.28 | 1.40 | 0.51–3.84 | 1.09 | 0.55–2.14 | 1.04 | 0.52–2.06 | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| (reference) Eating with others → eating with others | ||||||||||||||||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

The adjusted model adjusted for age, sex, living arrangements, educational level, cognitive status, depression, and instrumental activities of daily living

The presence of weight loss was defined as 2–3 kg of weight loss in the last 6 months

P value < 0.05.

P value < 0.01.

A comparison of complete cases and individuals who had missing data showed many significant differences. Individuals with missing data tended to be women and to be older compared with complete cases. The sensitivity analysis showed a slight difference between the results of the multiple-imputation data sets and the complete cases (Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of changes in eating alone or together on body weight. The proportion of older adults in the study sample who ate alone increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eating alone was associated only with perception of weight loss in both the baseline and follow-up surveys, and eating together at baseline and eating alone at follow-up did not lead to weight loss. Therefore, our hypothesis was partly rejected.

Older adults who eat alone are more likely to lose weight because they have fewer opportunities to eat a well-balanced meal and because they have a low food intake [5]. Although the results of this study do not completely support previous findings that self-perceived weight loss is associated with poor meal quality [14,15], the present findings are important. In addition, there was no association between eating changes and weight loss in the group that changed from eating with others to eating alone. It is likely that many individuals in this group followed the government request to avoid eating with people with whom they did not normally spend time [20]. The interval between the baseline and follow-up surveys in this study was only 7 mo. Depending on the timing of individuals’ shift from eating with others to eating alone in response to the government request, it is possible that individuals completed the follow-up survey shortly after starting to eat alone, which may have weakened the effect of eating alone. One study showed that 5.8% of community-dwelling older adults in Japan experienced losing more than 10% of their body weight during a period of 3 y [21]. Therefore, it is likely that few older adults experience weight loss over a short period. Additionally, because the effects of eating alone are stronger in older adults who live with others but eat alone or are depressed, it is possible that such individuals are more prone to weight fluctuations [4]. For example, in households where the timing of meals is changed to prevent infection between cohabitants, individuals may start eating alone. In such cases, the effects of eating alone on older adults may be strong.

We found no association between underweight and eating alone or together. This is probably because even if weight loss occurred, the investigation period of 7 mo was not long enough for individuals to become underweight. However, because the perception of weight loss occurred in many older adults who ate alone, it is likely that a longer-term survey would identify a higher number of underweight adults.

The comparison of complete cases and individuals with missing data demonstrated significant differences in many variables, suggesting that the complete case analysis may have generated bias. Therefore, we used multiple imputation to prevent such bias.

Study limitations and strengths

There were several study limitations. First, because participants responded to both baseline and follow-up surveys, it is possible that the sample contained only older adults with high health awareness who were interested in this type of survey. However, we tried to prevent selection bias as much as possible by randomly selecting participants. Owing to the use of a self-administered questionnaire, caution is needed in interpreting the results. Community-dwelling older adults aged ≥65 y were included, but the small sample size prevented us from conducting an age-stratified analysis. Although we statistically adjusted for the effect of age, the heterogeneity of this effect could not be addressed. Furthermore, the survey was conducted in one region of Japan, and the geographic and cultural background of that region may have affected the results. Because the survey was conducted in March and October, the results may have been affected by other factors, such as season. The results may also have been affected by bias in living arrangements, because many individuals in the eating alone group lived alone. However, bias caused by the number of individuals living alone may have been limited because the living-arrangements variable was used as a covariate in the analysis. Although previous dietary researchers have highlighted the importance of investigating with whom people are eating [22], it was not possible in this study to determine with whom respondents were eating. We plan to investigate the effect of different eating partners on weight fluctuations in the future. Additionally, the number of times individuals actually eat with others, rather than the opportunity to eat with others, should be investigated to determine its effect on weight fluctuations.

Conclusion

This study showed that only the individuals who continued to eat alone had self-perceived weight loss. However, because weight loss (even if subjective) has a negative effect on the health of older adults, interventions for weight loss in older adults who eat alone are required. Such interventions are particularly important during the current COVID-19 pandemic because the number of older adults who eat alone may be increasing. Longer-term investigations on the effect of eating alone during the COVID-19 pandemic are needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diane Williams, Ph.D., from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up: No. 19 K24277; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [C]: 19 K02200); a research grant from the Health Science Center Foundation (2019–2020); a Japan Full-hap Survey Research Grant from the Japan Small Business Welfare Foundation (2020); a research grant from the Foundation for Total Health Promotion (2019–2020); and grants from Seijoh University. These funding sources had no involvement in how the research was conducted, in data analysis and interpretation, in writing the article, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.nut.2022.111697.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Arai Y, Oguma Y, Abe Y, Takayama M, Hara A, Urushihara H, et al. Behavioral changes and hygiene practices of older adults in Japan during the first wave of COVID-19 emergency. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vesnaver E, Keller HH. Social influences and eating behavior in later life: A review. J Nutr Gerontol.Geriatr. 2011;30:2–23. doi: 10.1080/01639366.2011.545038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries; 2017. Shokuiku Promotion Policies: FY2018 (White Paper on Shokuiku.https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/wpaper/pdf/h30_eng_all.pdf [Summary]Available at: Accessed April 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tani Y, Kondo N, Noma H, Miyaguni Y, Saito M, Kondo K. Eating alone yet living with others is associated with mortality in older men: The JAGES cohort survey. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73:1330–1334. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae W, Ju YJ, Shin J, Jang SI, Park EC. Association between eating behaviour and diet quality: Eating alone vs. eating with others. Nutr J. 2018;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minagawa Y, Saito Y. The role of underweight in active life expectancy among older adults in Japan. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76:756–765. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishida MM, Okura M, Ogita M, Aoyama T, Tsuboyama T, Arai H. Two-year weight loss but not body mass index predicts mortality and disability in an older Japanese community-dwelling population. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:1654.e11–1654.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carneiro JA, de Almeida Lima C, da Costa FM, Caldeira AP. Health care are associated with worsening of frailty in community older adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2019;53:1–10. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2019053000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alharbi TA, Paudel S, Gasevic D, Ryan J, Freak-Poli R, Owen AJ. The association of weight change and all-cause mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50:697–704. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim M, Kim J, Won CW. Association between involuntary weight loss with low muscle mass and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: Nationwide surveys (KNHANES 2008–2011) Exp Gerontol. 2018;106:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björnwall A, Sydner YM, Koochek A, Neuman N. Eating alone or together among community-living older people—A scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3495. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Instructions of conducting the public survey of long-term care prevention and needs in spheres of daily life. October 23, 2019. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12301000/000560423.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2022.

- 13.Sakurai R, Kawai H, Suzuki H, Kim H, Watanabe Y, Hirano H, et al. Association of eating alone with depression among older adults living alone: Role of poor social networks. J Epidemiol. 2021;31:297–300. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20190217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura M, Ojima T, Nakade M, Ohtsuka R, Yamamoto T, Suzuki K, et al. Poor oral health and diet in relation to weight loss, stable underweight, and obesity in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study from the JAGES 2010 project. J Epidemiol. 2016;26:322–329. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20150144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama Y, Kitamura A, Nishi M, Seino S, Taniguchi Y, Amano H, et al. Frequency of balanced-meal consumption and frailty in community-dwelling older Japanese: A cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol. 2019;29:370–376. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20180076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi M, Sakata R, Sasaki Y, Murayama C, et al. Working from home and dietary changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study of Health App (CALO Mama) users. Appetite. 2021;165 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyano W, Shibata H, Nakazato K, Haga H, Suyama Y. Measurement of competence: Reliability and validity of the TMIG Index of Competence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1991;13:103–116. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(91)90053-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujihara S, Tsuji T, Miyaguni Y, Aida J, Saito M, Koyama S, et al. Does community-level social capital predict decline in instrumental activities of daily living? A JAGES prospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:828. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo Y, Ishimaru T, Hino A, Nagata M, Ikegami K, Tateishi S, et al. A cross-sectional study of the association between frequency of telecommuting and unhealthy dietary habits among Japanese workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12281. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusama T, Nakazawa N, Kiuchi S, Kondo K, Osaka K, Aida J. Dental prosthetic treatment reduced the risk of weight loss among older adults with tooth loss. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2498–2506. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scander H, Yngve A, Wiklund ML. Assessing commensality in research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.