Abstract

Background

Cancer patients constitute one of the highest-risk patient groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, it was aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine both the incidence and ICU (Intensive Care Unit) admission rates and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients.

Methods

The PRISMA guidelines were closely followed during the design, analysis, and reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis. A comprehensive literature search was performed for the published papers in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, medRxiv, Embase, and Web of Science (WoS) databases. SARS-CoV-2 infection pooled incidence in the cancer populations and the risk ratio (RR) of ICU admission rates/mortality in cancer and non-cancer groups, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated using the random-effects model.

Results

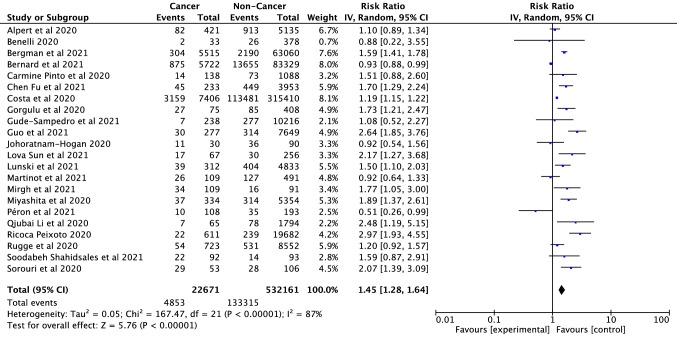

A total of 58 studies, involving 709,908 participants and 31,732 cancer patients, were included in this study. The incidence in cancer patients was calculated as 8% (95% CI: 8–9%). Analysis results showed that mortality and ICU admission rate was significantly higher in patients with cancer (RR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.94–2.62, P < 0.001; RR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.28–1.64, p < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

As a result, cancer was an important comorbidity and risk factor for all SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. This infection could result in severe and even fatal events in cancer patients. Cancer is associated with a poor prognosis in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer patients should be assessed more sensitively in the COVID-19 outbreak.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-022-04191-y.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Cancer, ICU admission, Mortality

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which started with a case detected in China on 12 December 2019, was declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 (WHO 2022, 2021; Rothe et al. 2020; Lu et al. 2020; Ge et al. 2020; Sung et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2020). Currently (May 1, 2020), WHO reported there are 500 million confirmed cases worldwide, with over 6 million deaths documented (WHO 2022). One of the most important problems caused by pandemics is the difficulty in the management of chronic diseases, the frequency of which is increasing with the prolongation of life expectancy in today’s world. Today, cancer constitutes a very important subset of chronic diseases. According to the GLOBOCAN (Global Cancer Observatory), in 2040, there will be 9.5 million new cancer cases globally and approximately 6.2 million new cancer-related deaths (GLOBOCAN 2022). It is obvious that the fight against this disease, which is currently very difficult to manage, requires the participation of many branches, and is quite deadly, has become even more difficult during the COVID-19 outbreak. But cancer and cancer-related deaths are just as important as the COVID-19 pandemic (Sung et al. 2021). This reveals the need to continue follow-up and treatment of patients even throughout the pandemic. Studies on COVID-19 revealed that advanced age and the presence of several comorbidities in patients result in a more severe COVID-19 clinical tableau and increased mortality (Zhang et al. 2020).

Cancer patients constitute the highest risk patient group during the pandemic due to both underlying diseases, most cancers occur at advanced age, and many chronic diseases increase with age (Rothe et al. 2020; Lu et al. 2020; Ge et al. 2020; Sung et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2020). The majority of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients experience mild to moderate respiratory symptoms; however, 13.8 percent of COVID-19 patients have severe symptoms, which can lead to multiple organ failure or death (Tian et al. 2020; Pascarella et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020a, b; Jin et al. 2020). According to recent research, SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals with comorbidities, such as endocrinopathies, chronic respiratory, renal, or chronic neurological disease, heart illness and cancer, had a worse prognosis (Jin et al. 2020; Espinosa et al. 2020; Chow et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2020; Wu and McGoogan, 2020).

Current studies have highlighted that cancer enhances sensitivity to SARS-CoV-2 infection and is a risk factor for worse clinical outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (Gao et al. 2020; Giannakoulis et al. 2020; Dai et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020). In a meta-analysis conducted by Giannakoulis et al. (2020), which included a total of 32 studies, on 46,499 SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with malignancy, it was reported that all-cause mortality increased in patients with cancer (RR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.33–2.07, p < 0.001). Similarly, in another meta-analysis that included a total of 63,019 participants, it was concluded that mortality was higher in populations with cancer (RR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.38–2.35, p < 0.001) (Yang et al. 2021). However, current studies had a relatively small sample size for COVID-19. New studies are emerging on this subject day by day. Therefore, the incidence, mortality and ICU admission rate in SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients should be calculated in larger samples and wide geographies. The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis involving a total of 709,908 participants from 4 continents and 16 countries (Brazil, USA, Sweden, Iran, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Turkey, Korea, Ireland, Nigeria, UK, Japan, Italy, People’s Republic of China, and India) to determine both the incidence, ICU admission rate and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients.

Material and methods

Literature search and search strategy

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) reporting guidelines were closely followed during the reporting, design, and analysis of this systematic review and meta-analysis (Liberati et al. 2009). Between March and April 11 (2022), a comprehensive literature searches were conducted for the published papers in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, medRxiv, Embase, and Web of Science (WoS) databases, and an update was performed on April 29 for this search. Related major factors were considered for the search query lines when choosing the keywords: “COVID-19”, “clinical characteristics”, “coronavirus”, “2019-nCoV”, “tumour”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “cancer”, “malignancy”, “outcomes”, and “neoplasm”. The related keywords were combined using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text terms, and the Boolean operators AND/OR were used to integrate the keywords. The search strategy was developed in the PubMed, Scopus and WoS databases and applied to other databases (medRxiv, Embase). Search strategies in the related literature are available in Supplemental Table S1. Relevant studies that could be included in the meta-analysis were downloaded from related databases. Afterward, these studies were transferred to Mendeley data management program for data evaluation and analysis.

Study selection and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Original research (case–control or cohort) published about the effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cancer from the beginning of the pandemic to April 29th were included in this study. Original studies that were published in the English language were researched, and no other types of paper were examined. In addition, studies covering the following criteria listed below were included in this research: (i) determination of patients in the study as SARS-CoV-2 through clinical/laboratory diagnosis; (ii) the research includes information on the number of cases or deaths or ICU (Intensive Care Unit) admission of participants with and without cancer in populations infected with SARS-CoV-2. Exclusion criteria: (i) reviews, guidelines, opinions, or other non-original data publications; (ii) projects and clinical trials that were incomplete; and (iii) no clinical evidence from animal and laboratory studies.

PICOS:

1. Population: “SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer and non-cancer patients”.

2. Intervention: “Cancer”.

3. Comparison: “Non-cancer”.

4. Outcomes: (i) “SARS-CoV-2 infection risk in patients with cancer”; (ii) “COVID-19 severity risk, including: ICU admission/mortality risk”.

5. Study: “Cohort or case-control studies”.

Data extraction, acquisition, and quality assessment

Papers were initially scanned based on the title and abstract in related database, and the full text of the appropriate papers were examined. The article titles and abstracts, and any differences amongst co-authors regarding which papers were eligible and which were not were handled using Delphi consensus criteria were examined by two independent authors (MEA and HE) (Verhagen et al. 1998), and the data was extracted into a pre-defined spreadsheet created using Microsoft Excel®. COVID-19 infection incidence, ICU admission, and mortality in cancer patients were separated into three groups and their risks were evaluated. Location, population, type of study, sex, number of patients with cancer and without cancer, ICU admission and mortality in patients with cancer and without cancer, with median age (if given) were also extracted into the same Excel file, in addition to the three key outcomes indicated above. To overcome data limitations-in case of missing data or doubt- the corresponding author(s) of the articles were contacted via email to obtain more details. Prepared data were cross-checked by two investigators via a standard spreadsheet to reach consensus. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality rating scale (NOS) was applied to all studies to evaluate the quality of the articles (Stang 2010).

Statistical analysis

Forest plots were utilized to compute and graphically illustrate the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of COVID-19 infection incidence, ICU admission and mortality rates in the cancer and non-cancer groups, and to summarize them. All research that reported SARS-CoV-2 infection incidence, mortality and/or ICU admission rates in cancer patients as an outcome were evaluated in primary and secondary meta-analyses. Sensitivity analysis -all studies were excluded from analysis separately- was performed to test the reliability of the study results. Mortality and ICU admission rate results in Europe, America and Asia were included in the subgroup analyses. I2 statistics and Cochran’s Q test were used to quantified between-study heterogeneity in all meta-analyses. A ratio of more than 50% in I2 statistics and a p ≤ 0.05 in Cochran’s Q test revealed that significant heterogeneity (Higgins et al. 2003). If the findings were heterogeneous, the analysis was carried out using random-effect models. Non-heterogeneous findings were calculated using fixed-effects models. For each significant outcome in our research, Egger’s linear regression test and funnel plots were utilized to examine the possibility of publication bias. Furthermore, NOS risk assessment method was used to evaluate the risk of bias in the included studies (Stang 2010). For each study, this instrument assigns a maximum score of nine in three categories: “selection”, “comparability”, and “outcome”. The statistical significance level was determined as a 2-sided p < 0.05. The Review Manager (v.5.4) (RevMan, 2020), ProMeta3® (Prometa-3, 2015) and Jamovi (version 2.3.3) (Jamovi, 2021) software were used for all the analyses.

Results

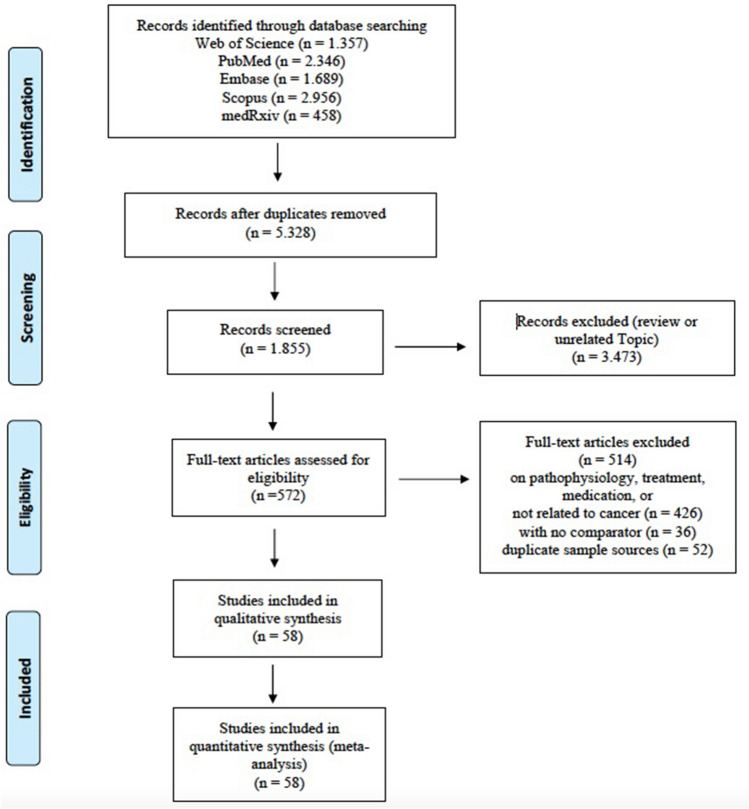

In the initial search, a total of 8806 articles were found, with 1357 in Web of Science, 2346 in PubMed, 1689 in Embase, 2956 in Scopus, and 458 in medRxiv databases. After a preliminary review and the elimination of duplicates, 5328 papers were screened and chosen for further evaluation. A total of 58 studies (Adejumo et al. 2021; Akhtar et al. 2021; Alpert et al. 2021; Arslan et al. 2021; Azarkar et al. 2021; Baker et al. 2021; Benelli et al. 2020; Bennett et al. 2021; Bergman et al. 2021; Bernard et al. 2021; Bhargava et al. 2021; Borobia et al. 2020; Pinto et al. 2020; Chai et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2021; Chudasama et al. 2021; Costa et al. 2021; Duanmu et al. 2020; Gold et al. 2020; Görgülü et al. 2020; Goyal et al. 2020; Gude-Sampedro et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2021; Joharatnam-Hogan et al. 2020; Katkat et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2021; Kokturk et al. 2021; Liang et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2021; Cavanna et al. 2020; Lunski et al. 2021; Martinot et al. 2021; Mirgh et al. 2021; Miyashita et al. 2020; Nakamura et al. 2021; Nikpouraghdam et al. 2020; Panda et al. 2022; Péron et al. 2021; Poli et al. 2022; Li et al. 2020a, b; Reddy et al. 2021; Regina et al. 2020; Ricoca-Peixoto et al. 2020; Giorgi-Rossi et al. 2020; Rugge et al. 2020; Erdal et al. 2021; Sami et al. 2020; Santorelli et al. 2021; Pérez-Segura et al. 2021; Serraino et al. 2021; Shahidsales et al. 2021; Sorouri et al. 2020; Stroppa et al. 2020; Tehrani et al. 2021; Vergara et al. 2021; Vila-Corcoles et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2021) (30 in Europe, 16 in Asia, 11 in America, and 1 in Africa) and 709,908 participants (31,732 cancer patients) were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis after applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A flow diagram demonstrating the selection process is available in Fig. 1, and the major parameters of the included studies are presented in Table 1. The quality scores of the included studies ranged from 6 to 9. The quality risk assessment of the relevant articles is shown in Supplementary Table S2. Furthermore, a bubble chart showing the distribution of studies by years is visually presented in Fig. S7.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study collection process

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of included studies in qualitative and quantitative synthesis

| Author | Country | Type of study | Sex (Male) | Median age | Cancer patients | Total patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adejumo et al. (2021) | Nigeria | R. cohort | 1872 | 60 | 14 | 2848 |

| Akhtar et al. (2021) | UK | R. cohort | 169 | NA | 51 | 293 |

| Alpert et al. (2020) | USA | R. cohort | 2907 | 66.5 | 421 | 5556 |

| Arslan et al. (2021) | Turkey | R. cohort | 374 | 52 | 41 | 713 |

| Azarkar et al. (2021) | Iran | R. cohort | 207 | 45 | 11 | 364 |

| Baker et al. (2021) | UK | R. cohort | 173 | 75 | 33 | 316 |

| Benelli et al. (2020) | Italy | R. cohort | 359 | 70.5 | 33 | 411 |

| Bennett et al. (2021) | Ireland | R. cohort | 8636 | NA | 747 | 19,789 |

| Bergman et al. (2021) | Sweden | R. case-control | 26,808 | NA | 5515 | 68,575 |

| Bernard et al. (2021) | France | R. cohort | NA | NA | 5722 | 89,051 |

| Bhargava et al. (2021) | USA | R. cohort | 294 | 64.4 | 46 | 565 |

| Borobia et al. (2020) | Spain | R. cohort | 1074 | 61 | 385 | 2226 |

| Pinto et al. (2020) | Italy | R. cohort | 733 | 71.7 | 138 | 1226 |

| Chai et al. (2021) | China | R. cohort | 246 | 65 | 166 | 498 |

| Fu et al. (2021) | USA | R. Case-control | 2438 | 71 | 233 | 4186 |

| Chudasama et al. (2021) | UK | R. cohort | 981 | NA | 179 | 1706 |

| Costa et al. (2021) | Brazil | R. cohort | 181,419 | NA | 7406 | 322,816 |

| Duanmu et al. (2020) | USA | R. cohort | 56 | 45 | 3 | 100 |

| Gold et al. (2020) | USA | R. cohort | 151 | 60 | 12 | 305 |

| Gorgulu et al. (2020) | Turkey | R. cohort | 278 | 74.4 | 75 | 483 |

| Goyal et al. (2020) | USA | R. cohort | 238 | 62.2 | 23 | 393 |

| Gude-Sampedro et al. (2021) | Spain | R. cohort | 4172 | 58 | 238 | 10,454 |

| Guo et al. (2021) | China | R. cohort | 3827 | 55 | 277 | 7926 |

| Joharatnam-Hogan et al. (2020) | UK | R. case-control | 80 | NA | 30 | 120 |

| Katkat et al. (2021) | Turkey | R. cohort | 270 | NA | 34 | 508 |

| Kim et al. (2021) | Korea | R. cohort | 3095 | 47 | 569 | 7590 |

| Kokturk et al. (2021) | Turkey | R. cohort | 850 | NA | 76 | 1500 |

| Liang et al. (2021) | China | R. cohort | NA | 65 | 109 | 3060 |

| Sun et al. (2021) | USA | R. cohort | 137 | 56 | 67 | 323 |

| Cavanna et al. (2020) | Italy | R. cohort | NA | 71 | 51 | 973 |

| Lunski et al. (2021) | USA | R. cohort | 2013 | NA | 312 | 5145 |

| Martinot et al. (2021) | France | R. cohort | 346 | 71.09 | 109 | 600 |

| Mirgh et al. (2021) | India | R. cohort | 126 | 43 | 109 | 200 |

| Miyashita et al. (2020) | USA | R. cohort | NA | NA | 334 | 5688 |

| Nakamura et al. (2020) | Japan | R. cohort | 22 | 74.5 | 32 | 235 |

| Nikpouraghdam et al. (2020) | Iran | R. cohort | 1955 | 56 | 17 | 2964 |

| Panda et al. (2022) | India/China | R. cohort | 279 | 37 | 10 | 420 |

| Péron et al. (2021) | France | R. case-control | 143 | 76.5 | 108 | 301 |

| Poli et al. (2021) | Italy | R. cohort | 653 | 71 | 141 | 1091 |

| Li et al. (2020a, b) | China | R. cohort | 934 | 59 | 65 | 1859 |

| Reddy et al. (2021) | India | R. cohort | NA | 40 | 23 | 4494 |

| Regina et al. (2020) | Swiss | R. cohort | 120 | 70.0 | 26 | 200 |

| Ricoca Peixoto et al. (2020) | Portugal | R. cohort | 8370 | NA | 611 | 20,270 |

| Rossi et al. (2021) | Italy | R. cohort | 1328 | 63.2 | 301 | 2653 |

| Rugge et al. (2020) | Italy | R. cohort | 4529 | NA | 723 | 9275 |

| Erdal et al. (2021) | Turkey | R. cohort | NA | 62 | 71 | 4489 |

| Sami et al. (2020) | Iran | R. cohort | 299 | 56.6 | 15 | 490 |

| Santorelli et al. (2021) | UK | R. cohort | 329 | NA | 47 | 582 |

| Segura et al. (2021) | Spain | R. cohort | NA | 75 | 770 | 5838 |

| Serraino et al. (2021) | Italy | R. cohort | 19,328 | NA | 3098 | 41,366 |

| Shahidsales et al. (2021) | Iran | R. case-control | 111 | 59.6 | 92 | 185 |

| Sorouri et al. (2020) | Iran | R. case-control | 91 | NA | 53 | 159 |

| Stroppa et al. (2020) | Italy | R. case-control | NA | NA | 25 | 56 |

| Tehrani et al. (2021) | USA | R. cohort | 4991 | 60.4 | 892 | 8222 |

| Vergara et al. (2021) | Italy | R. cohort | 710 | 71.1 | 49 | 1049 |

| Vila-Corcoles et al. (2021) | Spain | R. cohort | 235 | NA | 67 | 536 |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | China | R. cohort | 17,662 | 59 | 824 | 36,358 |

| Zhou et al. (2021) | China | R. case-control | 171 | 66 | 103 | 309 |

| Total | 31,732 | 709,908 |

Cancer incidence in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients

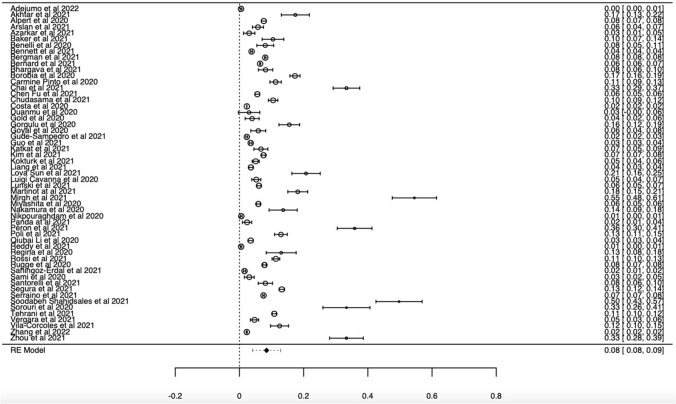

Data were analyzed from a total of 55 studies (Adejumo et al. 2021; Akhtar et al. 2021; Alpert et al. 2021; Arslan et al. 2021; Azarkar et al. 2021; Baker et al. 2021; Benelli et al. 2020; Bennett et al. 2021; Bergman et al. 2021; Bernard et al. 2021; Bhargava et al. 2021; Borobia et al. 2020; Pinto et al. 2020; Chai et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2021; Chudasama et al. 2021; Costa et al. 2021; Duanmu et al. 2020; Gold et al. 2020; Görgülü and Duyan, 2020; Goyal et al. 2020; Gude-Sampedro et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2021; Katkat et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2021; Kokturk et al. 2021; Liang et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2021; Cavanna et al. 2020; Lunski et al. 2021; Martinot et al. 2021; Mirgh et al. 2021; Miyashita et al. 2020; Nakamura et al. 2021; Nikpouraghdam et al. 2020; Panda et al. 2022; Péron et al. 2021; Poli et al. 2022; Li et al. 2020a, b; Reddy et al. 2021; Regina et al. 2020; Giorgi Rossi et al., 2020; Rugge et al. 2020; Erdal et al. 2021; Sami et al. 2020; Santorelli et al. 2021; Pérez-Segura et al. 2021; Serraino et al. 2021; Shahidsales et al. 2021; Sorouri et al. 2020; Tehrani et al. 2021; Vergara et al. 2021; Vila-Corcoles et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2021) on the incidence of cancer in SARS-CoV-2 infected participants (689,462 total participants, 31,066 with cancer). The pooled incidence of cancer in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients is presented in Fig. 2. The pooled ES of incidence in cancer patients was calculated as 8% (95% CI: 8–9%). The cancer incidence in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients was higher than the global cancer incidence (approximately 0.2%) (Bray et al. 2018). The incidence differences between countries were also examined. Among the included studies, the highest incidence was in France (16.912%, 5939/89,952); the lowest incidence was found in Nigeria and Brazil (0.024%, 7406/322,816; 0.004%, 14/2848) (Supplementary Table S3). There was no significant publication bias in the analysis results (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S2). In our analysis, a significant level of heterogeneity was determined among the studies (df = 54, I2 = 99%, p < 0.001). Sensitivity analyzes were performed by extracting each study separately. No significant change was observed in the analysis results. Thus, the robustness of the analysis results was confirmed by sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot illustrating the incidence of patients with cancer in all SARS-CoV-2 infected participants

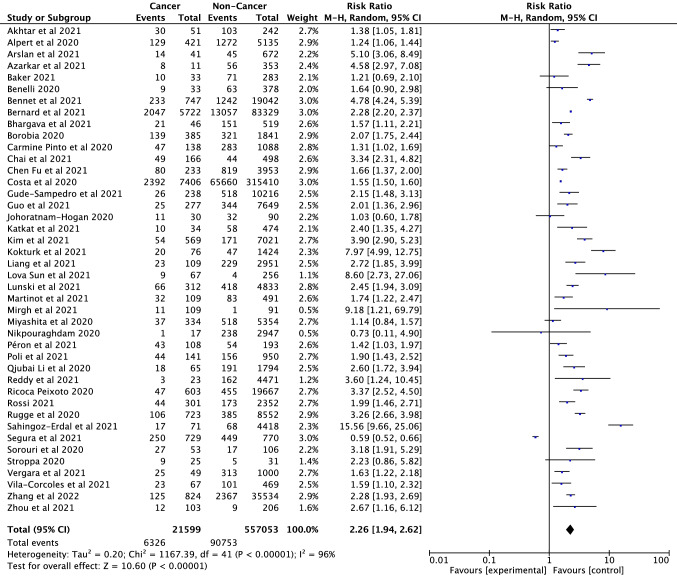

Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer and non-cancer patients

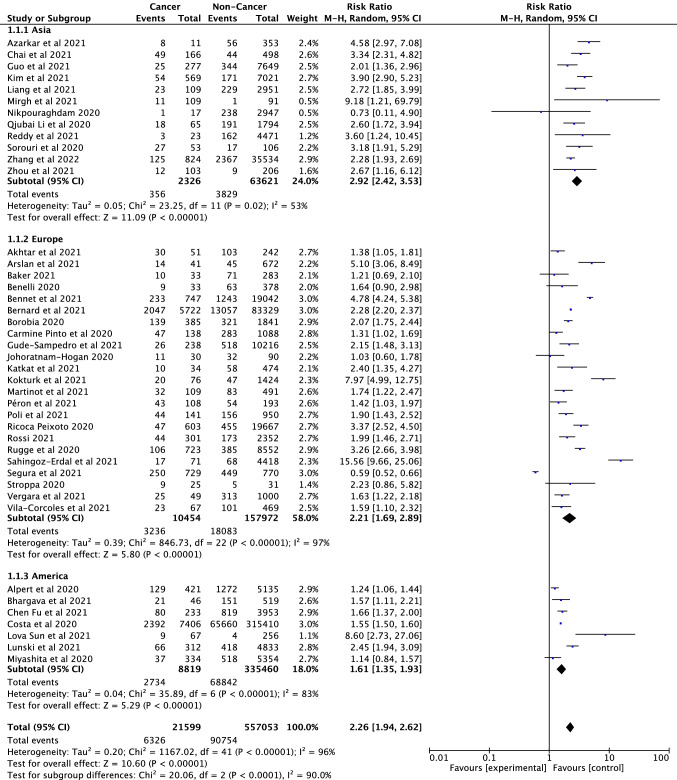

A total of 42 studies (Akhtar et al. 2021; Alpert et al. 2021; Arslan et al. 2021; Azarkar et al. 2021; Baker et al. 2021; Benelli et al. 2020; Bennett et al. 2021; Bernard et al. 2021; Bhargava et al. 2021; Borobia et al. 2020; Pinto et al. 2020; Chai et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2021; Gude-Sampedro et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2021; Joharatnam-Hogan et al. 2020; Katkat et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2021; Kokturk et al. 2021; Liang et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2021; Lunski et al. 2021; Martinot et al. 2021; Mirgh et al. 2021; Miyashita et al. 2020; Péron et al. 2021; Poli et al. 2022; Li et al. 2020a, b; Reddy et al. 2021; Ricoca Peixoto et al. 2020; Giorgi-Rossi et al. 2020; Rugge et al. 2020; Erdal et al. 2021; Pérez-Segura et al. 2021; Serraino et al. 2021; Shahidsales et al. 2021; Sorouri et al. 2020; Stroppa et al. 2020; Vergara et al. 2021; Vila-Corcoles et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2021) were included in the analysis to compare the mortality rates of cancer and non-cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. There were a total of 557,053 participants, of whom 21,599 were cancer patients. According to the analysis results, cancer is a serious risk factor for mortality among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (RR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.94–2.62, P < 0.001, Fig. 3). Mortality rates between continents were also evaluated as subgroup analysis and presented in Fig. 4. Mortality in cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 varies between continents, with the highest mortality rate in the Asian continent (RR = 2.92, CI: 2.42—3.53) and with the lowest in the European Continent (RR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.69–2.89, p < 0.001). No noticeable publication bias and obvious asymmetry was observed among the included studies (Supplementary Fig. S3 and S5). We found significant heterogeneity in this study results as seen in Fig. 3 (df = 41, I2 = 96%, p < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses were conducted by subtracting each of the studies. No significant change was observed in the analysis results.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot illustrating the mortality of patients with cancer/non-cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for region subgroup analysis of the cancer mortality of patients with cancer/non cancer in all SARS-CoV-2 infected participants

ICU admission rates in SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer and non-cancer patients

ICU admission rates of a total of 22,671 SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients and 532,161 non-cancer patients were analyzed from 22 eligible studies (Alpert et al. 2021; Benelli et al. 2020; Bergman et al. 2021; Bernard et al. 2021; Pinto et al. 2020; Fu et al. 2021; Costa et al. 2021; Görgülü et al. 2020; Gude-Sampedro et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2021; Joharatnam-Hogan et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2021; Lunski et al. 2021; Martinot et al. 2021; Mirgh et al. 2021; Miyashita et al. 2020; Péron et al. 2021; Li et al. 2020a, b; Ricoca Peixoto et al. 2020; Rugge et al. 2020; Shahidsales et al. 2021; Sorouri et al. 2020). The rate of ICU admission in patients with cancer was significantly higher than in individuals without cancer (RR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.28–1.64, p < 0.001; heterogeneity: df = 21, I2 = 87%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5). It was determined that there was no publication bias according to the symmetry of the funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression test (Supplementary Fig. S4). ICU admission in cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 varies between continents, with the highest ICU admission rate in the Asian continent (RR = 2.26, CI: 1.80–2.83) and with the lowest in the European Continent (RR = 1.13, 95% CI: 0.86–1.48, p < 0.001) with no publication bias (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S6). Although there is a significant heterogeneity in Europe and America (df = 8, I2 = 78%, p < 0.001; df = 5, I2 = 86%, p < 0.001, respectively), no significant heterogeneity was observed in the Asian continent (df = 3, I2 = 0%, p = 0.61).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot illustrating the ICU admission of patients with cancer/non-cancer in all SARS-CoV-2 infected participants

Discussion

It is a well-known fact that the incidence of cancer continues to increase rapidly worldwide, with lifestyle changes and environmental factors such as poor nutrition, polluted air, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle (Sung et al. 2021). Cancer patients have been severely affected by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Studies with COVID-19 and cancer patients have reported that cancer is a risk factor that can lead to adverse clinical outcomes for SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients (Desai et al. 2020; Serraino 2020). However, in several studies, it was revealed that there was no significant difference in cancer and non-cancer populations in terms of mortality rates of COVID-19 (Liu et al. 2020; Spezzani et al. 2020; Barlesi et al. 2020). In another study conducted in France, it was reported that serious events in breast cancer patients were proximate to the general population. It has been stated that the reason for this situation is the stricter social distance procedures in terms of the location of cancer patients (Vuagnat et al. 2020). In addition to all these, in meta-analyses conducted on relatively small samples to our studies evaluating mortality, incidence and ICU hospitalization rates in cancer and non-cancer groups, it was reported that both mortality and ICU hospitalization rates of cancer patients were higher than non-cancer patients (Giannakoulis et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2021; Salunke et al. 2020). Therefore, a more comprehensive meta-analysis is required to perform for determine the relationship between cancer and COVID-19 in larger geographies and samples.

A total of 58 papers were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. 709,908 SARS-CoV-2 infected participants worldwide were systematically analyzed and a meta-analysis was performed. The incidence of cancer was estimated in all SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (8%, 95% CI: 8–9%). We concluded that this result is much higher than the rate of approximately 2% in the general population (Bray et al. 2018). However, cancer appeared to be an important risk factor for mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (RR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.94–2.62, P < 0.001). In addition, the ICU admission rate was significantly higher in patients with cancer than in patients without cancer (RR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.28–1.64, p < 0.001). The risk of infection in cancer patients differs according to factors such as genetic predisposition, physical condition, ethnicity, nutritional status, age and sex of individuals (Zhang et al. 2020). Thus, virus can more easily enter cells in cancer patients (Zhang et al. 2020; Dai et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020). Moreover, it can make the immune system weak in cancer patients even more dysfunctional (Zhang et al. 2020; Dai et al. 2020). Besides, patients with cancer must visit the hospital on a routine basis to have their treatment. This may be a factor that directly increases the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Previous studies (Giannakoulis et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2020; Salunke et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2021) were carried out with relatively smaller samples compared to our study. Studies on COVID-19 are constantly increasing cumulatively. Our study included a substantial sample covering large geographic regions and many countries. There were studies with duplicate samples. To avoid duplication of sample sources, we included only studies with the largest sample size. We evaluated the quality of the included studies using the NOS. Studies with a score of six or more were considered high-quality studies. Sensitivity analysis, a method that excludes each study separately, was performed. There was no noticeable difference in the analysis results. These findings showed that the study was stable and robust.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this research. The most of data in the included studies were from hospital-based studies. In this regard, there may be inherent biases, particularly in patient selection, medical and surgical treatment regimens, and loss of follow-up of patients. In addition, most SARS-CoV-2 infected cancer patients without hospitalization may have been excluded. Because most of the included studies did not have information on the effect of treatment or chemotherapy on ICU admission and / or mortality, their impact could not be evaluated. In addition to all these, the inability to compare cancer patients without COVID-19 with cancer patients suffering from COVID-19, which can be resulting in a potential bias in the study, was another important limitation of the study. A high level of heterogeneity was detected in most of the results, including the incidence analysis. Furthermore, although we performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, these results were not sufficient to explain the source of heterogeneity. However, our study included large sample sizes in a wide range of countries and populations across several geographies. This may indicate that healthcare, lifestyles, ethnic differences, treatment types and procedures may have increased or decreased susceptibility to cancer or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Importantly, the COVID-19 pandemic was managed diversely in different nations, as were the techniques adopted to control and prevent to SARS-CoV-2 infection. All these reasons could potentially have influenced the high level of heterogeneity. Finally, in all countries, further improvement, and development of community-based registries, where hospital-based information is collected, may also allow meta-analyses to be conducted with larger populations.

Conclusions

To date, the pandemic has caused the loss of many people. But it should be kept in mind that cancer is at least as deadly as COVID-19. As a result, cancer was an important comorbidity and risk factor for all COVID-19 patients, and SARS-CoV-2 infection could result in severe and even fatal events in cancer patients. The results of the current systematic review and meta-analysis show that cancer patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have higher ICU admission and higher mortality rates. The most important advantage of this study was that the sample size was very large, and it represented and covered a wide range of geographies. This study emphasized the importance of managing patients with comorbidities, especially cancer, during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, cancer patients may have more hospital visits due to multi-stage treatment in cancer. Thus, cancer patients may become prone and susceptible to COVID-19. So, the frequency of follow-up of cancer patients could be reduced during periods when the rate of the epidemic was high, and if possible, treatments could be postponed for a while. Also, and importantly, healthcare professionals should be vigilant for cancer patients, especially COVID-19 period, individualized treatment plans should be devised to avoid disease progression.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MEA: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing-original draft preparation, writing-reviewing and editing, critical review. NK, UK, CK, DK, MEK, AVK, SK, AK, MAK, IGK, EBK, EK, BK, FK, BK: visualization, investigation, validation, writing-original draft preparation, critical review. HE: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing-original draft preparation, writing-reviewing and editing, critical review. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adejumo OA, Ogunniyan T, Adesola S, Gordon I, Oluwadun OB, Oladokun OD et al (2021) Clinical presentation of COVID-19-positive and-negative patients in Lagos Nigeria: a comparative study. Niger Postgrad Med J 28:75. 10.4103/npmj.npmj_547_21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar Z, Gallagher MM, Yap YG, Leung LW, Elbatran AI, Madden B et al (2021) Prolonged QT predicts prognosis in COVID-19. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 44:875–882. 10.1111/pace.14232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert N, Rapp JL, Marcellino B, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Flores R, Taioli E (2021) Clinical course of cancer patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. JNCI Cancer. 10.1093/jncics/pkaa085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan Y, Dogan D, Ocal N, Koc A, Ayaz T, Ozkan R et al (2021) The boundaries between survival and nonsurvival at COVID-19: experience of tertiary care pandemic hospital. Int J Clin Pract 75:e14461. 10.1111/ijcp.14461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarkar Z, Salehiniya H, Kazemi T, Abbaszadeh H (2021) Epidemiological, imaging, laboratory, and clinical characteristics and factors related to mortality in patients with COVID-19: a single-center study. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 12:169–176. 10.24171/j.phrp.2021.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KF, Hanrath AT, van der Loeff IS, Tee SA, Capstick R, Marchitelli G et al (2021) COVID-19 management in a UK NHS foundation trust with a high consequence infectious diseases centre: a retrospective analysis. Med Sci 9:6. 10.3390/medsci9010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlesi F, Foulon S, Bayle A, Gachot B, Pommeret F, Willekens C et al (2020) Outcome of cancer patients infected with COVID-19, including toxicity of cancer treatments. AACR Annual Meeting 2020 Online abstr.CT403:27–28.

- Benelli G, Buscarini E, Canetta C, La Piana G, Merli G, Scartabellati A et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 comorbidity network and outcome in hospitalized patients in Crema, Italy. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.14.20053090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KE, Mullooly M, O’Loughlin M, Fitzgerald M, O’Donnell J, O’Connor L et al (2021) Underlying conditions and risk of hospitalisation, ICU admission and mortality among those with COVID-19 in Ireland: a national surveillance study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 5:100097. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Ballin M, Nordström A, Nordström P (2021) Risk factors for COVID-19 diagnosis, hospitalization, and subsequent all-cause mortality in Sweden: a nationwide study. Eur J Epidemiol 36:287–298. 10.1007/s10654-021-00732-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard A, Cottenet J, Bonniaud P, Piroth L, Arveux P, Tubert-Bitter P et al (2021) Comparison of cancer patients to non-cancer patients among COVID-19 inpatients at a national level. Cancers 13:1436. 10.3390/cancers13061436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava A, Szpunar SM, Sharma M, Fukushima EA, Hoshi S, Levine M et al (2021) Clinical features and risk factors for in-hospital mortality from COVID-19 infection at a tertiary care medical center, at the onset of the US COVID-19 pandemic. J Intensive Care Med 36:711–718. 10.1177/08850666211001799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borobia AM, Carcas AJ, Arnalich F, Alvarez-Sala R, Montserrat J, Quintana M et al (2020) A cohort of patients with COVID-19 in a major teaching hospital in Europe. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.29.20080853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna L, Citterio C, Toscani I, Franco C, Magnacavallo A, Caprioli S et al (2020) Cancer patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study of 51 patients in the district of Piacenza, northern Italy. Future Sci OA. 7:FSO645. 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai C, Feng X, Lu M, Li S, Chen K, Wang H et al (2021) One-year mortality and consequences of COVID-19 in cancer patients: a cohort study. IUBMB Life 73:1244–1256. 10.1002/iub.2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow N, Fleming-Dutra K, Gierke R, Hall A, Hughes M, Pilishvili T et al (2020) Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 – United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:382–386. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama YV, Zaccardi F, Gillies CL, Razieh C, Yates T, Kloecker DE et al (2021) Patterns of multimorbidity and risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: an observational study in the UK. BMC Infect Dis 21:1–12. 10.1186/s12879-021-06600-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa GJ, de Azevedo CRAS, Júnior JIC, Bergmann A, Thuler LCS (2021) Higher severity and risk of in-hospital mortality for COVID-19 patients with cancer during the year 2020 in Brazil: a countrywide analysis of secondary data. Cancer 127:4240–4248. 10.1002/cncr.33832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z et al (2020) Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov 10:783–791. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R (2020) COVID-19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol 6:557–559. 10.1200/GO.20.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duanmu YY, Brown IP, Gibb WR, Singh J, Matheson LW, Blomkalns AL et al (2020) Characteristics of emergency department patients with COVID-19 at a single site in northern California: clinical observations and public health implications. Acad Emerg Med 27:505–509. 10.1111/acem.14003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdal GS, Polat O, Erdem GU, Korkusuz R, Hindilerden F, Yilmaz M et al (2021) The mortality rate of COVID-19 was high in cancer patients: a retrospective single-center study. Int J Clin Oncol 26:826–834. 10.1007/s10147-021-01863-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa OA, Zanetti ADS, Antunes EF, Longhi FG, Matos TA, Battaglini PF (2020) Prevalence of comorbidities in patients and mortality cases affected by SARS-CoV2: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 62:e43. 10.1590/S1678-9946202062043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Stoeckle JH, Masri L, Pandey A, Cao M, Littman D et al (2021) COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients with active cancer: experiences from a major New York city health care system. Cancer 127:3466–3475. 10.1002/cncr.33657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Liu M, Shi S, Chen Y, Sun Y, Chen J et al (2020) Cancer is associated with the severity and mortality of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.05.01.2008703133330887 [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Wang X, Yuan X, Xiao G, Wang C, Deng T et al (2020) The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 39:1011–1019. 10.1007/s10096-020-03874-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Siempos II (2020) Effect of cancer on clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of patient data. JCO Global Oncol 6:799–808. 10.1200/GO.20.00225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi Rossi P, Marino M, Formisano D, Venturelli F, Vicentini M, Grilli R (2020) Characteristics and outcomes of a cohort of SARS-CoV-2 patients in the province of Reggio Emilia, Italy. PLoS ONE 15:e0238281. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLOBOCAN (Globoal Cancer Observatory) (2022) Cancer Tomorrow. Estimated Number of New Cases and Deaths from 2020 to 2040, Both sexes, Age [0–85+]. Accessed on: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/bars?mode=population&key=total&show_bar_mode_prop=1&types=1. Accessed 24 April 2022

- Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, Patel PR, Rossow J, da Silva J et al (2020) Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 – Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:545–550. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görgülü Ö, Duyan M (2020) Effects of comorbid factors on prognosis of three different geriatric groups with COVID-19 diagnosis. SN Compr Clin Med 2:2583–2594. 10.1007/s42399-020-00645-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York city. N Engl J Med 382:2372–2374. 10.1056/NEJMc2010419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gude-Sampedro F, Fernández-Merino C, Ferreiro L, Lado-Baleato Ó, Espasandín-Domínguez J, Hervada X et al (2021) Development and validation of a prognostic model based on comorbidities to predict COVID-19 severity: a population-based study. Inter J of Epidemiol 50:64–74. 10.1093/ije/dyaa209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Wang H, Zhu Q, Yuan Y (2021) Clinical Characteristics of cancer patients with COVID-19: a retrospective multicentric study in 19 hospitals within Hubei, China. Front Med 8:614057. 10.3389/fmed.2021.614057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The jamovi project (2021) jamovi (Version 2.3.3) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- Jin Y, Yang H, Ji W, Wu W, Chen S, Zhang W et al (2020) Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of COVID-19. Viruses 12:372. 10.3390/v12040372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joharatnam-Hogan N, Hochhauser D, Shiu K-K, Rush H, Crolley V, Butcher E et al (2020) Outcomes of the 2019 novel coronavirus in patients with or without a history of cancer – a multi-centre north London experience. Ther Adv Med Oncol 12:1758835920956803. 10.1177/1758835920956803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katkat F, Karahan S, Varol S, Kalyoncuoglu M, Okuyan E (2021) Mortality prediction with CHA2DS2-VASc CHA2DS2-VASc-HS and R2CHA2DS2-VASc score in patients hospitalized due to COVID-19. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25:6767–6774. 10.26355/eurrev_202111_27121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Kim YC, Park JY, Jung J, Lee JP, Kim H (2021) Evaluation of the prognosis of COVID-19 patients according to the presence of underlying diseases and drug treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:5342. 10.3390/ijerph18105342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokturk N, Babayigit C, Kul S, Cetinkaya PD, Nayci SA, Baris SA et al (2021) The predictors of COVID-19 mortality in a nationwide cohort of Turkish patients. Respir Med 183:106433. 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB et al (2020a) COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol 92:577–583. 10.1002/jmv.25757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Chen L, Li Q, He W, Yu J, Chen L et al (2020b) Cancer increases risk of in-hospital death from COVID-19 in persons< 65 years and those not in complete remission. Leukemia 34:2384–2391. 10.1038/s41375-020-0986-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang WH, Guan WJ, Li CC, Li YM, Liang HR, Zhao Y et al (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 treated in Hubei (epicentre) and outside Hubei (nonepicentre): a nationwide analysis of China. Eur Respir J 55:2000562. 10.1183/13993003.00562-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Jin G, Liu T, Wen J, Li G, Chen L et al (2021) Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in cancer patients with COVID-19. Front Med 15:264–274. 10.1007/s11684-021-0845-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzla J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6:e1000100. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhao Y, Okwan-Duodu D, Basho R, Cui X (2020) COVID-19 in cancer patients: risk, clinical features, and management. Cancer Biol Med 17:519–527. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW (2020) Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol 92:401e1. 10.1002/jmv.25678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunski MJ, Burton J, Tawagi K, Maslov D, Simenson V, Barr D et al (2021) Multivariate mortality analyses in COVID-19: comparing patients with cancer and patients without cancer in Louisiana. Cancer 127:266–274. 10.1002/cncr.33243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Yin J, Qian Y, Wu Y (2020) Clinical characteristics and prognosis in cancer patients with COVID-19: a single center’s retrospective study. J Infect 81:318–356. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinot M, Eyriey M, Gravier S, Bonijoly T, Kayser D, Ion C et al (2021) Predictors of mortality, ICU hospitalization, and extrapulmonary complications in COVID-19 patients. Infect Dis Now 51:518–525. 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirgh SP, Gokarn A, Rajendra A, More A, Kamtalwar S, Katti KS et al (2021) Clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters and outcomes of COVID-19 in cancer and non-cancer patients from a tertiary cancer centre in India. Cancer Med 10:8777–8788. 10.1002/cam4.4379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita H, Mikami T, Chopra N, Yamada T, Chernyavsky S, Rizk D et al (2020) Do patients with cancer have a poorer prognosis of COVID-19? An experience in New York city. Ann Oncol 31:1088–1089. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Kanemasa Y, Atsuta Y, Fujiwara S, Tanaka M, Fukushima K et al (2021) Characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with cancer: a single-center retrospective observational study in Tokyo, Japan. Int J Clin Oncol 26:485–493. 10.1007/s10147-020-01837-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikpouraghdam M, Jalali Farahani A, Alishiri G, Heydari S, Ebrahimnia M, Samadinia H et al (2020) Epidemiological characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in Iran: a single center study. J Clin Virol 127:104378. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Roy S, Garg RK, Hui G, Gorard J, Bhutada M et al (2022) COVID-19 disease in hospitalized young adults in India and China: evaluation of risk factors predicting progression across two major ethnic groups. J Med Virol 94:272–278. 10.1002/jmv.27315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, Bruno F, Del Buono R, Costa F et al (2020) COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med 288:192–206. 10.1111/joim.13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Segura P, Paz-Cabezas M, Núñez-Gil IJ, Arroyo-Espliguero R, Eid CM, Romero R et al (2021) Prognostic factors at admission on patients with cancer and COVID-19: analysis of HOPE registry data. Med Clin 157:318–324. 10.1016/j.medcle.2021.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péron J, Dagonneau T, Conrad A, Pineau F, Calattini S, Freyer G et al (2021) COVID-19 presentation and outcomes among cancer patients: a matched case-control study. Cancers 13:5283. 10.3390/cancers13215283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto C, Berselli A, Mangone L, Damato A, Iachetta F, Foracchia M et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 positive hospitalized cancer patients during the Italian outbreak: the cohort study in Reggio Emilia. Biology 9:181. 10.3390/biology9080181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli D, Antonucci E, Ageno W, Prandoni P, Palareti G, Marcucci R (2022) Low in-hospital mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 receiving thromboprophylaxis: data from the multicentre observational START-COVID register. Intern Emerg Med 17:1013–1021. 10.1007/s11739-021-02891-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ProMeta-3 professional statistical software for conducting meta-analysis (2015) It is based on ProMeta 2.1 deployed by Internovi in 2015. https://idostatistics.com/prometa3/

- Reddy KP, Elagandula J, Patel S, Patidar R, Asati V, Shrivastav SP et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care in a tertiary care facility. South Asian J Cancer 10:32–35. 10.1055/s-0041-1731577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regina J, Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Burger R, Filippidis P, Tschopp J, Desgranges F et al (2020) Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in a Swiss university hospital: an observational retrospective study. PLoS ONE 15:e0240781. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4 (2020) The Cochrane Collaboration. Available at revman.cochrane.org

- Ricoca Peixoto V, Vieira A, Aguiar P, Sousa P, Carvalho C, Thomas D et al (2020) COVID-19: determinants of hospitalization, ICU and death among 20,293 reported cases in Portugal. Euro Surveill 26:2001059. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.33.2001059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C et al (2020) Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 382:970e1. 10.1056/NEJMc2001468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugge M, Zorzi M, Guzzinati S (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Italian Veneto region: adverse outcomes in patients with cancer. Nat Cancer 1:784–788. 10.1038/s43018-020-0104-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salunke AA, Nandy K, Pathak SK, Shah J, Kamani M, Kottakota V et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 in cancer patients on severity of disease and fatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:1431–1437. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sami R, Soltaninejad F, Amra B, Naderi Z, Haghjooy Javanmard S, Iraj B et al (2020) A one-year hospital-based prospective COVID-19 open-cohort in the eastern Mediterranean region: the khorshid COVID cohort (KCC) study. PLoS ONE 15:e0241537. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santorelli G, McCooe M, Sheldon TA, Wright J, Lawton T (2021) Ethnicity, pre-existing comorbidities, and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Wellcome Open Res. 6:32. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16580.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serraino D (2020) COVID-19 and cancer: looking for evidence. Eur J Surg Oncol 46:929–930. 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serraino D, Zucchetto A, Dal Maso L, Del Zotto S, Taboga F, Clagnan E et al (2021) Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of SARS-COV-2 infection among cancer patients. A population-based study in northern Italy. Cancer Med 10:7781–7792. 10.1002/cam4.4271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahidsales S, Aledavood SA, Joudi M, Molaie F, Esmaily H et al (2021) COVID-19 in cancer patients may be presented by atypical symptoms and higher mortality rate, a case-controlled study from Iran. Cancer Rep 4:e1378. 10.1002/cnr2.1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorouri M, Kasaeian A, Mojtabavi H, Radmard AR, Kolahdoozan S, Anushiravani A et al (2020) Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and risk factors for mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and cancer history: a propensity score-matched study. Infect Agents Cancer 15:1–11. 10.1186/s13027-020-00339-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spezzani V, Piunno A, Iselin HU (2020) Benign COVID-19 in an immunocompromised cancer patient – the case of a married couple. Swiss Med Wkly 150:w20246. 10.4414/smw.2020.20246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in metaanalyses. Eur J Epidemiol 25:603–605. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroppa EM, Toscani I, Citterio C, Anselmi E, Zaffignani E, Codeluppi M et al (2020) Coronavirus disease-2019 in cancer patients. a report of the first 25 cancer patients in a western country (Italy). Future Oncol 16:1425–1432. 10.2217/fon-2020-0369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Surya S, Le AN, Desai H, Doucette A, Gabriel P et al (2021) Rates of COVID-19–related outcomes in cancer compared with noncancer patients. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 10.1093/jncics/pkaa120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A et al (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani DM, Wang X, Rafique AM, Hayek SS, Herrmann J, Neilan TG et al (2021) Impact of cancer and cardiovascular disease on in-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 patients: results from the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Cardio-Oncology 7:1–8. 10.1186/s40959-021-00113-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Hu N, Lou J, Chen K, Kang X, Xiang Z et al (2020) Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect 80:401–406. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara P, Rossi L, Biagi A, Falasconi G, Pannone L, Zanni A et al (2021) Role of comorbidities on the mortality in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an Italian cohort study. Minerva Med. 10.23736/S0026-4806.21.07187-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Bouter LM et al (1998) The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1235–1241. 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00131-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Corcoles A, Satue-Gracia E, Vila-Rovira A, de Diego-Cabanes C, Forcadell-Peris MJ, Ochoa-Gondar O et al (2021) COVID19-related and all-cause mortality risk among middle-aged and older adults across the first epidemic wave of SARS-COV-2 infection: a population-based cohort study in southern Catalonia, Spain, March–June 2020. BMC Public Health 21:1–15. 10.1186/s12889-021-11879-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuagnat P, Frelaut M, Ramtohul T, Basse C, Diakite S, Noret A et al (2020) COVID-19 in breast cancer patients: a cohort at the Institut Curie Hospitals in the Paris area. Breast Cancer Res 22:55. 10.1186/s13058-020-01293-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2021) Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 20 July 2021 Edition 49. Accessed on: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---20-july-2021 Accessed 29 January 2022

- WHO (2022) WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports, https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Accessed 01 May 2022

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 323:1239–1242. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Chai P, Yu J, Fan X (2021) Effects of cancer on patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 63,019 participants. Cancer Biol Med 18:298. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, Wang C, Wang J, Chen R et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol 31:894–901. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wu Y, He Y, Liu X, Liu M, Tang Y et al (2021) Age-related risk factors and complications of patients with COVID-19: a population-based retrospective study. Front Med 8:757459. 10.3389/fmed.2021.757459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Yang Q, Ye J, Wu X, Hou X, Feng Y et al (2021) Clinical features and death risk factors in COVID-19 patients with cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 21:1–10. 10.1186/s12879-021-06495-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.