Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Background.

The unplanned use of dual induction therapy with interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies (IL2rAb) and antithymocyte globulin (ATG) may portend adverse outcomes.

Methods.

We used national transplant registry data to study clinical correlates and outcomes of single versus dual induction therapy in adult kidney-only transplant recipients in the United States (2005–2018). The risk of death and graft loss at 1 and 5 y, according to induction therapy type, was assessed using multivariate Cox regression analysis (adjusted hazard ratio with 95% upper and lower confidence limits [LCLaHRUCL]).

Results.

Of the 157 351 recipients included in the study, 67% were treated with ATG alone, 29% were treated with IL2rAb alone, and 5% were treated with both. Compared with IL2rAb alone, the strongest correlates of dual induction included Black race, calculated panel reactive antibody ≥80%, prednisone-sparing maintenance immunosuppression, more recent transplant eras, longer cold ischemia time, and delayed graft function. Compared with ATG alone, dual induction was associated with an increased 5-y risk of death (aHR 1.071.151.23; P < 0.0001), death-censored graft failure (aHR 1.051.131.22; P < 0.05), and all-cause graft failure (aHR 1.061.121.18; P < 0.0001).

Conclusions.

Further research is needed to develop risk-prediction tools to further inform optimal, individualized induction protocols for kidney transplant recipients.

INTRODUCTION

The optimization of short-term graft survival is closely related to the prevention of early acute rejection following organ transplant. Induction therapy is widely used in the immediate posttransplant period to rapidly reduce the immune response against an allograft. Biologic induction agents target the T and B lymphocytes responsible for organ rejection and consist of either monoclonal antibodies, such as interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies (IL2rAb), or polyclonal antibodies, such as antithymocyte globulin (ATG). The 2009 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guideline for the “Care of Kidney Transplant Recipients” recommends that IL2rAb be the first-line induction agent, whereas polyclonal lymphocyte-depleting induction agents be considered for recipients at higher immunologic risk.1 The recipient’s immunologic risk assessment is individualized and considers multiple factors, such as Black race, allosensitization, and retransplant. In addition to assessing immunologic risk, the deleterious effects of induction therapy must also be considered, as ATG is associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, as well as high costs.2

In challenging cases, recipients deemed as low immunologic risk may initially be treated with IL2rAb induction, only to be switched to ATG if later deemed to be at high immunologic risk, resulting in unplanned treatment with both induction therapy agents. There is limited research on the risk factors and outcomes of recipients unexpectedly treated with dual induction therapy. We previously reported on a single-center Canadian study of 430 kidney transplant recipients showing that 1 in 10 recipients treated with IL2rAb induction was also treated with ATG induction.3 Compared with the ATG-alone recipients, the dual induction recipients had worse graft function at 1 y (mean estimated glomerular filtration rate, 42 versus 59 mL/min/1.73 m2; P = 0.0008) and an increased risk of all-cause graft failure (ACGF: 31% versus 13%; P = 0.02) and death-censored graft failure (DCGF: 16% versus 4%; P = 0.03). Limitations of this study included small sample size and too few events to perform meaningful adjusted analyses to characterize clinical correlates. In the current study, we extend on our previous work by using national transplant data from the United States to assess clinical correlates and outcomes of single versus dual induction therapy in a large cohort of kidney transplant recipients from 2005 to 2018. Based on our previous studies,3,4 we hypothesized that there would be differences in induction therapy between US and Canadian recipients, but that US recipients treated with dual induction therapy would have worse outcomes than recipients treated with single-agent induction therapy, as in the Canadian cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using linked healthcare databases in the United States to ascertain patient characteristics, pharmacy fill records, and outcome events for kidney transplant recipients. This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR includes data on all donors, waitlist candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Additional data were drawn from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Social Security Death Master File. The Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, oversees the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

Population and Covariates

We considered all adult (>18 y) kidney-only transplant recipients who underwent transplant in the United States between 2005 and 2018. We excluded pediatric recipients (≤18 y) and those who received a simultaneous multiorgan transplant (eg, kidney-pancreas) because these recipients are primarily managed by services other than the adult kidney transplant service. Induction immunosuppression was defined by center reporting to the registry and recorded as a binary answer (given or not), including the indication (discriminating use for induction versus treatment of acute rejection), but information on dose and days of treatment was not available. We categorized induction therapy as IL2rAb alone, ATG alone, or both (IL2rAb + ATG). We collected recipient and donor clinical and demographic characteristics from OPTN Transplant Candidate Registration and Transplant Recipient Registration forms. Maintenance immunosuppression was categorized on the basis of data at the time of discharge: triple therapy (prednisone [Pred] + tacrolimus [Tac] + mycophenolic acid [MPA: mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolate sodium] or azathioprine [AZA]), steroid-sparing (Tac + MPA/AZA), MPA/AZA-sparing (Pred + Tac or Tac alone), mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor (mTORi)-based (sirolimus, or everolimus) with or without Tac or cyclosporine [CsA]), CsA-based (CsA without sirolimus or everolimus), and other maintenance regimens (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Recipient and transplant characteristics according to type of induction therapy used

| Characteristic | Overall | IL2rAb alone | ATG alone | IL2rAb + ATG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 157 351) | (n = 45 128) | (n = 104 786) | (n = 7437) | |

| Recipients factors | ||||

| Age (y) | 53.0 (20.0) | 55.0 (21.0) | 52.0 (19.0)‡ | 54.0 (20.0)‡ |

| 19–30 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 7.8 |

| 31–44 | 21.1 | 18.7 | 22.1 | 20.3 |

| 45–59 | 37.9 | 35.2 | 39.0 | 37.4 |

| ≥60 | 32.4 | 37.4 | 30.1 | 34.6 |

| Female sex | 39.4 | 34.4 | 41.7‡ | 35.9* |

| Race | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| White | 50.2 | 55.5 | 48.9 | 38.1 |

| Black | 25.8 | 18.6 | 28.4 | 32.8 |

| Hispanic | 15.8 | 16.4 | 15.0 | 22.8 |

| Other | 8.2 | 9.5 | 7.8 | 6.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (7.7) | 27.2 (7.4) | 27.5 (7.8)‡ | 27.5 (7.8)‡ |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 29.8 | 30.7 | 29.5 | 29.7 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 32.9 | 34.0 | 32.4 | 33.2 |

| Obese (≥30) | 32.6 | 30.8 | 33.2 | 33.7 |

| Missing | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| Primary cause of ESKD | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 27.2 | 28.6 | 26.4 | 29.3 |

| Hypertension | 22.2 | 19.9 | 22.8 | 27.5 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 20.5 | 20.4 | 20.7 | 18.2 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 9.7 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 8.6 |

| Other/missing | 20.5 | 21.0 | 20.6 | 16.4 |

| Pretransplant dialysis modality | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Preemptive | 15.9 | 19.6 | 14.6 | 11.1 |

| Hemodialysis | 43.4 | 42.1 | 43.0 | 56.5 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 7.8 |

| Missing | 32.3 | 29.7 | 34.1 | 24.6 |

| Dialysis duration (y) | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| None | 15.9 | 19.6 | 14.6 | 11.1 |

| 0–2 | 26.6 | 30.3 | 25.4 | 20.9 |

| >2–5 | 31.1 | 28.9 | 31.9 | 34.8 |

| >5 | 25.7 | 20.4 | 27.5 | 32.2 |

| Missing | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| ABO blood group | ‡ | * | ||

| O | 44.7 | 43.6 | 45.1 | 45.5 |

| A | 37.0 | 37.9 | 36.7 | 35.7 |

| B | 13.4 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.6 |

| AB | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.3 |

| Most recent cPRA (%) | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| 0 | 62.8 | 74.4 | 57.3 | 70.4 |

| 1–9 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 9.8 |

| 10–79 | 18.3 | 12.7 | 20.9 | 14.2 |

| ≥80 | 9.7 | 2.7 | 13.0 | 5.3 |

| Missing | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Previous organ transplant | 14.3 | 9.0 | 16.8‡ | 10.1* |

| Hypertension | 70.5 | 69.7 | 70.3* | 77.3‡ |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33.0 | 34.1 | 32.4‡ | 34.6 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.1* | 2.5 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 6.8 | 7.1 | 6.6† | 7.3 |

| COPD | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1† | 0.9* |

| Malignancy | 7.8 | 9.0 | 7.3‡ | 6.6‡ |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Pred + Tac + MPA/AZA | 65.2 | 72.5 | 62.9 | 52.6 |

| Tac + MPA/AZA (no Pred) | 22.7 | 11.5 | 26.6 | 36.4 |

| Pred + Tac or Tac alone | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| mTORi-based | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 2.2 |

| CsA-based | 4.1 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| Other/missing | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 4.5 |

| Primary payer | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Private | 34.7 | 38.4 | 33.7 | 27.7 |

| Public | 65.0 | 61.2 | 66.1 | 71.9 |

| Missing | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Donor and transplant factors | ||||

| Transplant era | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| 2005–2008 | 25.6 | 31.8 | 22.8 | 28.0 |

| 2009–2012 | 27.3 | 28.7 | 26.7 | 28.6 |

| 2013–2015 | 21.2 | 19.0 | 22.2 | 20.4 |

| 2016–2018 | 25.9 | 20.5 | 28.4 | 23.0 |

| Donor type | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Standard criteria donor | 45.1 | 38.7 | 47.5 | 49.9 |

| Expanded criteria donor | 9.6 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 13.2 |

| Donation after circulatory death donor | 11.2 | 7.6 | 12.7 | 11.1 |

| Living (related) donor | 21.8 | 31.0 | 18.2 | 17.3 |

| Living (unrelated) donor | 12.4 | 13.6 | 12.2 | 8.4 |

| Donor age (y) | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| ≤18 | 7.7 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 7.6 |

| 19–30 | 20.8 | 19.5 | 21.4 | 20.4 |

| 31–44 | 28.9 | 29.6 | 28.8 | 27.0 |

| 45–59 | 34.3 | 35.2 | 33.8 | 36.1 |

| ≥60 | 8.2 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 9.0 |

| HLA mismatches | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Zero A, B, DR | 7.7 | 9.6 | 7.0 | 5.2 |

| Zero DR | 11.2 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 10.8 |

| Other | 81.1 | 79.7 | 81.5 | 83.9 |

| CMV status | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | 16.0 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 12.2 |

| Donor (+)/recipient (–) | 16.7 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 15.6 |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 64.3 | 63.0 | 64.4 | 69.9 |

| Missing | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

| EBV status | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Donor (+)/recipient (–) | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 69.9 | 67.0 | 71.7 | 62.0 |

| Missing | 22.3 | 25.1 | 20.7 | 28.8 |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| 0–12 | 46.8 | 53.6 | 44.8 | 33.3 |

| 13–24 | 33.8 | 29.5 | 36.1 | 26.7 |

| >24 | 13.5 | 9.7 | 13.8 | 32.6 |

| Missing | 6.0 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 7.4 |

| Delayed graft functiona | 18.8 | 14.8 | 19.8‡ | 28.7‡ |

Data are presented as proportions, except for age, BMI, and dialysis duration, which are presented as median (interquartile range).

aDefined as receipt of dialysis within the first wk of transplant.

P values for pairwise comparison (reference to IL2rAb alone):

*P < 0.05–0.002.

†P = 0.001–0.0001.

‡P < 0.0001.

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; AZA, azathioprine; BMI, body mass index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; cPRA, calculated panel reactive antibody; CsA, cyclosporine; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies; MPA, mycophenolic acid; mTORi-based, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; Pred, prednisone; Tac, tacrolimus.

Outcomes

Recipients were followed from their transplant date until death, outcome of interest, or end of study (December 31, 2019). The primary outcomes were all-cause death, DCGF, and ACGF. Graft failure was defined as return to maintenance dialysis or “preemptive” retransplant. ACGF included graft loss due to patient death. Outcomes were assessed at 1 and 5 y posttransplant.

Statistical Analyses

Datasets were merged and analyzed with SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Distributions of clinical and demographic characteristics among recipients with each induction therapy type, compared with IL2rAb alone, were compared by the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. We modeled the likelihood of ATG alone and IL2rAb + ATG induction use compared with IL2rAb alone using multivariable logistic regression (adjusted odds ratio with 95% upper and lower confidence limits [LCLaORUCL]). IL2rAb alone was the referent induction because it is considered first-line therapy. Also, the most common scenario for receipt of dual induction therapy is initial use of IL2rAb followed by subsequent use of ATG.3 Thus, these recipients are initially deemed to be at low immunologic risk (similar to the IL2rAb-alone recipients) but are later deemed to be at high immunologic risk (similar to the ATG-alone recipients). For this reason, the ATG-alone group was the referent induction for the outcome analyses. Risk of death and graft loss at 1 and 5 y, according to induction therapy type, was assessed using multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusting for the covariates in Table 1 (LCLaHRUCL). Cumulative incidence of death and graft loss were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess statistical significance of differences in unadjusted incidence across induction therapy types. Given the potential for confounding by indication, we performed additional analyses comparing recipients with and without delayed graft function. We interpreted 2-tailed P < 0.05 as statistically significant. The study followed guidelines for observational studies (Table S1, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TXD/A348).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

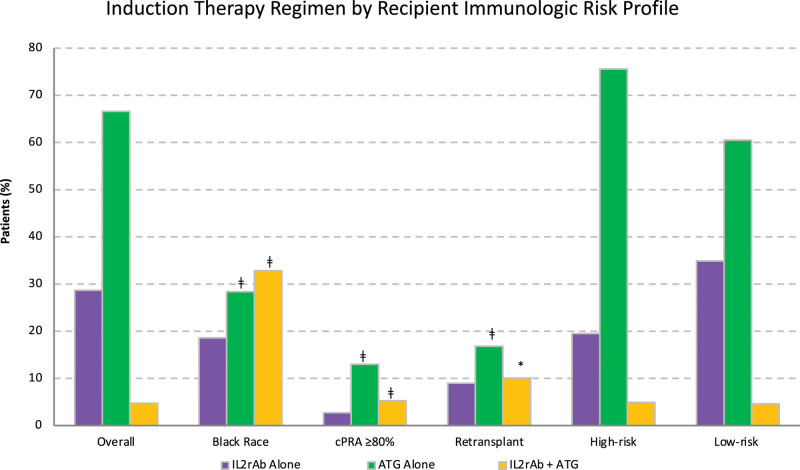

The study cohort consisted of 157 351 adult kidney-only transplant recipients, of whom 67% were treated with ATG alone, 29% were treated with IL2rAb alone, and 5% were treated with both IL2rAb + ATG (Figure 1). Overall, the median age at transplant was 53 y (interquartile range, 20), 39% of recipients were female individuals, and 50% were White (Table 1). Diabetes mellitus was the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), affecting 27% of recipients, followed by hypertension (22%) and glomerulonephritis (21%). The incidence of delayed graft function, defined as dialysis within the first week of transplant, was 19% in our cohort. At the time of discharge, standard triple maintenance immunosuppression (Pred + Tac + MPA/AZA) was the most commonly used regimen (65% of recipients).

FIGURE 1.

Induction therapy regimen overall and by recipient immunologic risk profile, wherein high risk was defined as Black race, cPRA ≥80%, or retransplant. *P < 0.05–0.002; †P=0.001–0.0001; ‡P < 0.0001. ATG, antithymocyte globulin; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies; cPRA, calculated panel reactive antibody.

Correlates of Dual Induction Therapy

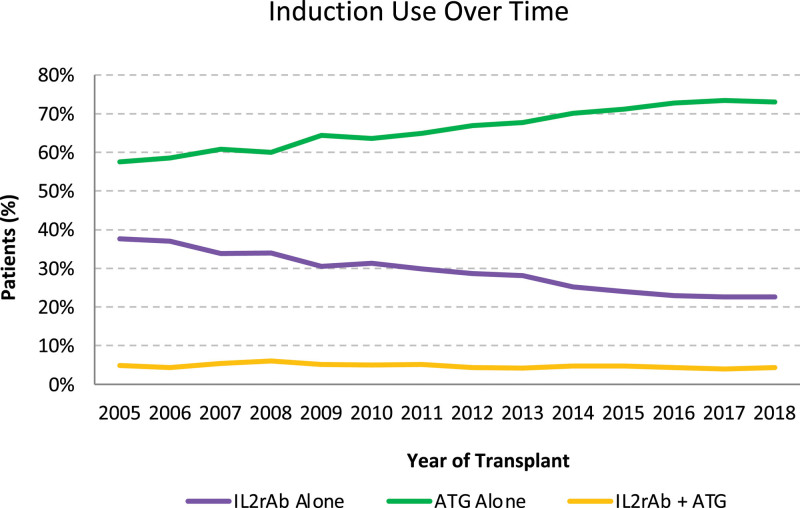

Over the years, the use of IL2rAb alone for induction decreased, whereas ATG alone for induction increased and dual IL2rAb + ATG induction remained stable (Figure 2). The use of dual induction therapy was similar in lower- and higher-risk recipients (4.6% versus 4.9%) (Figure 1). Compared with IL2rAb-alone induction, recipients treated with dual induction therapy were more likely to be female individuals, Black race (versus White race), have hypertension as a comorbidity and cause of ESKD (versus glomerulonephritis), have a longer dialysis duration, be more sensitized, have a 0 DR HLA mismatch (versus 0 A, B, DR mismatch), have had a previous transplant, be discharged on a prednisone-sparing maintenance regimen (versus Pred + Tac + MPA/AZA), have received a transplant in the more recent eras (versus 2005–2008), have received an expanded criteria donor kidney (vs standard criteria donor), have had a longer cold ischemia time (versus 0–12 h), and have experienced delayed graft function (Table 2). Also, they were less likely to be older, have had a preemptive transplant, have had a previous malignancy, have been discharged on a CsA-based maintenance regimen, and have received a living donor kidney. Results were similar for recipients who received ATG-alone induction. The association with highly sensitized recipients (calculated panel reactive antibody [cPRA] ≥80%) was stronger with ATG-alone induction than with dual induction therapy (aOR 4.614.925.24 versus 1.691.922.19).

FIGURE 2.

National trends in kidney transplant induction over time. ATG, antithymocyte globulin; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies.

TABLE 2.

Associations of recipient and transplant characteristics with type of induction therapy used compared with IL2rAb alone (referent induction)

| Characteristic | aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| ATG Alone | IL2rAb + ATG | |

| Recipients factors | ||

| Age (y) | ||

| 19–30 | 1.02 (0.97-1.07) | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) |

| 31–44 | Referent | Referent |

| 45–59 | 0.93 (0.90-0.96)‡ | 0.92 (0.86-0.99)* |

| ≥60 | 0.65 (0.63-0.68)‡ | 0.74 (0.69-0.80)‡ |

| Female sex | 1.20 (1.17-1.23)‡ | 1.14 (1.08-1.20)‡ |

| Race | ||

| White | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 1.41 (1.36-1.45)‡ | 1.75 (1.63-1.88)‡ |

| Hispanic | 0.90 (0.86-0.93)‡ | 1.45 (1.35-1.56)‡ |

| Other | 0.81 (0.77-0.85)‡ | 0.72 (0.64-0.80)‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.88 (0.82-0.96)* | 0.96 (0.80-1.14) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | Referent | Referent |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08)* | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) |

| Obese (≥30) | 1.13 (1.09-1.16)‡ | 1.06 (1.00-1.14) |

| Missing | 1.62 (1.49-1.76)‡ | 0.49 (0.39-0.62)‡ |

| Primary cause of ESKD | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) | 1.04 (0.91-1.18) |

| Hypertension | 1.04 (1.00-1.08)* | 1.12 (1.03-1.22)* |

| Glomerulonephritis | Referent | Referent |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) |

| Other/missing | 0.89 (0.86-0.93)‡ | 0.85 (0.78-0.92)† |

| Pretransplant dialysis modality | ||

| Hemodialysis | Referent | Referent |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.80 (0.72-0.88)‡ |

| Missing | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | 0.68 (0.63-0.73)‡ |

| Dialysis duration (y) | ||

| None | 0.95 (0.91-0.99)* | 0.75 (0.68-0.83)‡ |

| 0–2 | Referent | Referent |

| >2–5 | 1.04 (1.01-1.08)* | 1.17 (1.09-1.27)‡ |

| >5 | 1.05 (1.01-1.09)* | 1.21 (1.11-1.32)‡ |

| Missing | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) | 1.63 (1.25-2.12)† |

| ABO blood group | ||

| O | 1.02 (0.99-1.04) | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) |

| A | Referent | Referent |

| B | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) |

| AB | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | 1.11 (0.98-1.24) |

| Most recent cPRA (%) | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1–9 | 1.16 (1.11-1.21)‡ | 1.08 (0.99-1.18) |

| 10–79 | 2.10 (2.03-2.18)‡ | 1.29 (1.20-1.40)‡ |

| ≥80 | 4.92 (4.61-5.24)‡ | 1.92 (1.69-2.19)‡ |

| Missing | 2.16 (1.81-2.59)‡ | 0.87 (0.49-1.53) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Previous organ transplant | 1.60 (1.54-1.67)‡ | 1.39 (1.26-1.52)‡ |

| Hypertension | 1.13 (1.10-1.17)‡ | 1.20 (1.12-1.29)‡ |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.00 (0.95-1.06) | 0.90 (0.80-1.01) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.19 (1.13-1.25)‡ | 0.92 (0.82-1.04) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) | 1.07 (0.90-1.26) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.87 (0.83-0.91)‡ | 0.97 (0.87-1.07) |

| COPD | 0.89 (0.80-0.99)* | 0.83 (0.64-1.07) |

| Malignancy | 0.80 (0.77-0.84)‡ | 0.79 (0.72-0.88)‡ |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | ||

| Pred + Tac + MPA/AZA | Referent | Referent |

| Tac + MPA/AZA (no Pred) | 3.60 (3.47-3.72)‡ | 5.31 (5.00-5.64)‡ |

| Pred + Tac or Tac alone | 1.28 (1.15-1.42)‡ | 1.11 (0.87-1.41) |

| mTORi-based | 1.69 (1.59-1.80)‡ | 1.01 (0.86-1.20) |

| CsA-based | 0.51 (0.48-0.54)‡ | 0.61 (0.53-0.71)‡ |

| Other/missing | 1.19 (1.11-1.27)‡ | 2.28 (2.00-2.59)‡ |

| Primary payer | ||

| Private | 1.07 (1.04-1.10)‡ | 0.96 (0.90-1.03) |

| Public | Referent | Referent |

| Missing | 0.86 (0.69-1.06) | 1.65 (1.11-2.46)* |

| Donor and transplant factors | ||

| Transplant era | ||

| 2005–2008 | Referent | Referent |

| 2009–2012 | 1.25 (1.20-1.29)‡ | 1.31 (1.22-1.41)‡ |

| 2013–2015 | 1.58 (1.52-1.64)‡ | 1.51 (1.39-1.64)‡ |

| 2016–2018 | 1.82 (1.74-1.90)‡ | 1.77 (1.61-1.94)‡ |

| Donor type | ||

| Standard criteria donor | Referent | Referent |

| Expanded criteria donor | 1.18 (1.12-1.24)‡ | 1.14 (1.03-1.27)* |

| Donation after circulatory death donor | 1.39 (1.33-1.45)‡ | 1.04 (0.95-1.13) |

| Living (related) donor | 0.57 (0.55-0.60)‡ | 0.78 (0.70-0.85)‡ |

| Living (unrelated) donor | 0.77 (0.74-0.81)‡ | 0.87 (0.78-0.97)* |

| Donor age (y) | ||

| ≤18 | 1.08 (1.03-1.14)* | 0.98 (0.88-1.09) |

| 19–30 | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | 1.05 (0.98-1.13) |

| 31–44 | Referent | Referent |

| 45–59 | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 1.06 (0.99-1.14) |

| ≥60 | 0.94 (0.89-0.99)* | 1.00 (0.88-1.13) |

| HLA mismatches | ||

| Zero A, B, DR | Referent | Referent |

| Zero DR | 1.73 (1.63-1.83)‡ | 2.03 (1.78-2.32)‡ |

| Other | 1.78 (1.70-1.87)‡ | 2.02 (1.80-2.26)‡ |

| CMV status | ||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | Referent | Referent |

| Donor (+)/recipient (–) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 1.08 (0.98-1.19) |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 0.94 (0.91-0.97)† | 1.12 (1.03-1.21)* |

| Missing | 1.25 (1.16-1.35)‡ | 0.83 (0.69-1.00) |

| EBV status | ||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | Referent | Referent |

| Donor (+) recipient (–) | 0.89 (0.79-1.02) | 0.51 (0.41-0.64)‡ |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 0.94 (0.84-1.06) | 0.41 (0.33-0.50)‡ |

| Missing | 0.94 (0.83-1.06) | 0.63 (0.51-0.78)‡ |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | ||

| 0–12 | Referent | Referent |

| 13–24 | 1.00 (0.96-1.03) | 1.02 (0.94-1.10) |

| >24 | 1.10 (1.05-1.15)‡ | 3.38 (3.12-3.67)‡ |

| Missing | 1.16 (1.10-1.22)‡ | 1.80 (1.62-2.00)‡ |

| Delayed graft functiona | 1.18 (1.14-1.22)‡ | 1.66 (1.55-1.77)‡ |

aDefined as receipt of dialysis within the first week of transplant.

P values for pairwise comparison (reference to IL2rAb alone):

*P < 0.05–0.002.

†P = 0.001–0.0001.

‡P < 0.0001.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; AZA, azathioprine; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; cPRA, calculated panel reactive antibody; CsA, cyclosporine; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies; MPA, mycophenolic acid; mTORi-based, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; Pred, prednisone; Tac, tacrolimus.

Death and Graft Failure According to Induction Regimen

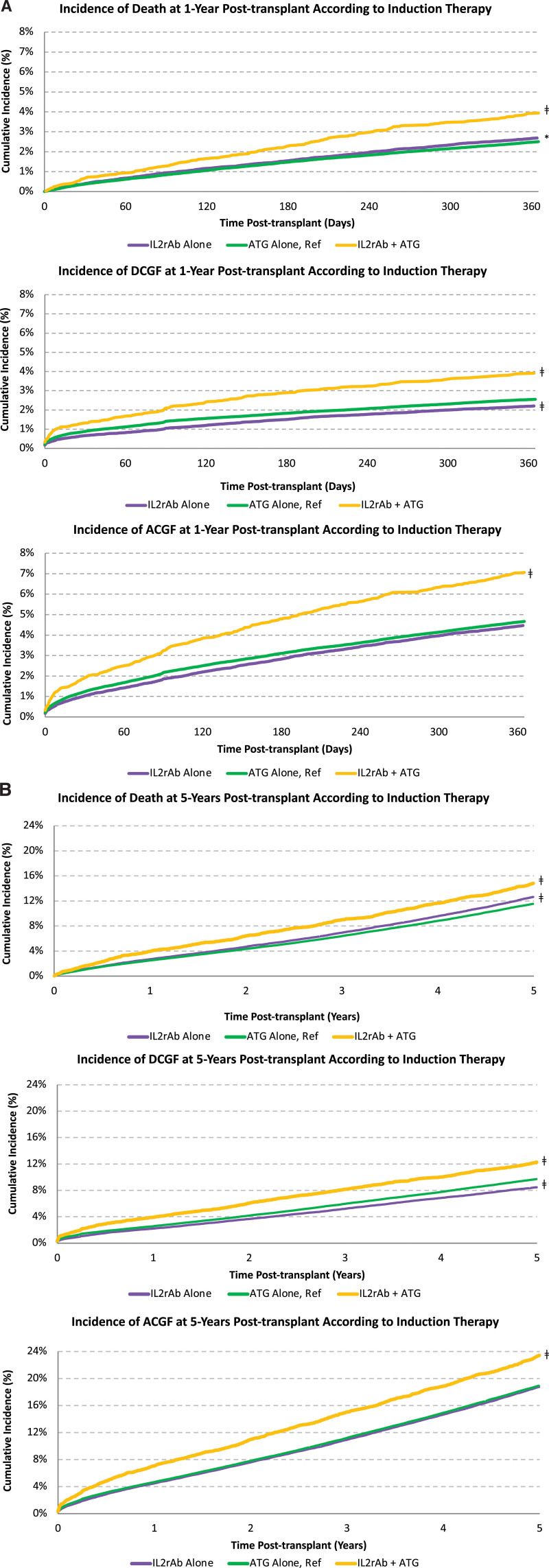

The incidence of death and graft failure at 1 and 5 y posttransplant was higher in the dual induction therapy group than in the IL2rAb-alone group or ATG-alone group (Figure 3). For example, by 5 y posttransplant, the incidence of death, DCGF, and ACGF for recipients treated with dual induction therapy was 15%, 12%, and 23%, respectively, compared with 12%, 10%, and 19%, respectively, for recipients treated with ATG-alone induction (P < 0.0001 for all).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence of death and graft failure according to type of induction therapy at (A) 1 y posttransplant and (B) 5 y posttransplant. *P < 0.05–0.002; †P=0.001–0.0001; ‡P < 0.0001. ACGF, all-cause graft failure; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; DCGF, death-censored graft failure; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies.

Compared with induction with ATG alone, dual induction therapy was associated with an increased 5-y risk of death (aHR 1.071.151.23; P < 0.0001), DCGF (aHR 1.051.131.22; P < 0.05), and ACGF (aHR 1.061.121.18; P < 0.0001) (Table 3). Results were similar to the IL2rAb-alone induction group, except that DCGF did not reach statistical significance. Higher sensitization (cPRA, 10% to 79% and ≥80% versus 0%); previous organ transplant; comorbid chronic pulmonary disease; MPA/AZA-sparing, mTORi-based, and CsA-based maintenance regimens; receipt of an expanded criteria donor kidney; older donor age (45–59 and ≥60 y versus 31–44 y); cytomegalovirus mismatch (donor positive/recipient negative versus donor negative/recipient negative); and positive cytomegalovirus recipient serology, cold ischemia time >24 h (versus 0 to 12 h), and delayed graft function were all associated with an increased risk of death and graft failure. Conversely, Hispanic race, polycystic kidney disease as a cause of ESKD, pretransplant peritoneal dialysis, preemptive transplant, comorbid hypertension, private primary payer, more recent transplant era, younger donor age (19–30 versus 31–44 y), and receipt of a living donor kidney were associated with a lower risk of death and graft failure.

TABLE 3.

Associations of induction therapy type and recipient and transplant characteristics with death and graft failure at 5 y posttransplant

| Characteristic | aHR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death | Death-censored graft failure | All-cause graft failure | |

| Recipients factors | |||

| Induction therapy | |||

| IL2rAb alone | 1.09 (1.05-1.13)‡ | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07)* |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.15 (1.07-1.23)‡ | 1.13 (1.05-1.22)* | 1.12 (1.06-1.18)‡ |

| Age (y) | |||

| 19–30 | 0.74 (0.66-0.83)‡ | 1.79 (1.69-1.90)‡ | 1.49 (1.42-1.58)‡ |

| 31–44 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 45–59 | 1.82 (1.72-1.94)‡ | 0.71 (0.68-0.75)‡ | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) |

| ≥60 | 3.37 (3.17-3.58)‡ | 0.60 (0.57-0.64)‡ | 1.45 (1.39-1.51)‡ |

| Female sex | 0.93 (0.90-0.96)‡ | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 0.96 (0.93-0.99)* |

| Race | |||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 0.80 (0.77-0.84)‡ | 1.47 (1.41-1.54)‡ | 1.09 (1.06-1.13)‡ |

| Hispanic | 0.59 (0.56-0.63)‡ | 0.83 (0.78-0.88)‡ | 0.69 (0.67-0.72)‡ |

| Other | 0.61 (0.57-0.65)‡ | 0.86 (0.80-0.93)† | 0.71 (0.68-0.75)‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1.21 (1.08-1.35)* | 0.92 (0.82-1.05) | 1.05 (0.96-1.15) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95)‡ | 1.09 (1.04-1.14)† | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) |

| Obese (≥30) | 0.90 (0.87-0.94)‡ | 1.24 (1.18-1.29)‡ | 1.05 (1.02-1.09)* |

| Missing | 1.07 (0.97-1.17) | 1.06 (0.95-1.17) | 1.08 (1.00-1.16)* |

| Primary cause of ESKD | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.40 (1.30-1.50)‡ | 0.91 (0.84-1.00)* | 1.16 (1.09-1.23)‡ |

| Hypertension | 1.30 (1.22-1.37)‡ | 1.02 (0.97-1.08) | 1.13 (1.09-1.18)‡ |

| Glomerulonephritis | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0.81 (0.75-0.88)‡ | 0.73 (0.67-0.79)‡ | 0.76 (0.71-0.80)‡ |

| Other/missing | 1.23 (1.16-1.31)‡ | 1.01 (0.95-1.06) | 1.07 (1.03-1.11)* |

| Pretransplant dialysis modality | |||

| Hemodialysis | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.84 (0.79-0.89)‡ | 0.86 (0.81-0.92)‡ | 0.83 (0.80-0.87)‡ |

| Missing | 0.85 (0.81-0.89)‡ | 0.82 (0.78-0.86)‡ | 0.84 (0.81-0.87)‡ |

| Dialysis duration (y) | |||

| None | 0.68 (0.64-0.73)‡ | 0.66 (0.61-0.71)‡ | 0.68 (0.65-0.72)‡ |

| 0–2 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| >2–5 | 1.11 (1.07-1.17)‡ | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08)* |

| >5 | 1.41 (1.34-1.48)‡ | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | 1.18 (1.13-1.23)‡ |

| Missing | 1.07 (0.90-1.28) | 0.84 (0.68-1.03) | 0.95 (0.82-1.10) |

| ABO blood group | |||

| O | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00)* |

| A | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| B | 0.95 (0.88-1.02) | 0.93 (0.85-1.01) | 0.94 (0.88-0.99)* |

| AB | 0.96 (0.93-0.99)* | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) |

| Most recent cPRA (%) | |||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1–9 | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | 1.05 (1.00-1.09)* |

| 10–79 | 1.08 (1.03-1.12)* | 1.08 (1.03-1.14)* | 1.07 (1.03-1.10)† |

| ≥80 | 1.11 (1.04-1.19)* | 1.20 (1.12-1.29)‡ | 1.14 (1.08-1.20)‡ |

| Missing | 0.78 (0.58-1.05) | 1.03 (0.76-1.39) | 0.92 (0.74-1.15) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Previous organ transplant | 1.25 (1.19-1.32)‡ | 1.10 (1.04-1.16)* | 1.17 (1.12-1.22)‡ |

| Hypertension | 0.93 (0.89-0.97)† | 0.93 (0.89-0.98)* | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.38 (1.30-1.47)‡ | 1.02 (0.95-1.10) | 1.20 (1.14-1.26)‡ |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.21 (1.15-1.28)‡ | 1.04 (0.96-1.11) | 1.15 (1.10-1.21)‡ |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.16 (1.07-1.26)† | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | 1.12 (1.04-1.20)* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.38 (1.31-1.45)‡ | 1.08 (1.00-1.16) | 1.27 (1.22-1.33)‡ |

| COPD | 1.59 (1.44-1.75)‡ | 1.26 (1.09-1.45)* | 1.45 (1.33-1.58)‡ |

| Malignancy | 1.18 (1.12-1.24)‡ | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 1.13 (1.08-1.18)‡ |

| Maintenance immunosuppression | |||

| Pred + Tac + MPA/AZA | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Tac + MPA/AZA (no Pred) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11)* | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) |

| Pred + Tac or Tac alone | 1.24 (1.10-1.40)† | 1.46 (1.29-1.67)‡ | 1.36 (1.23-1.49)‡ |

| mTORi-based | 1.31 (1.22-1.41)‡ | 1.38 (1.28-1.49)‡ | 1.35 (1.28-1.43)‡ |

| CsA-based | 1.22 (1.14-1.30)‡ | 1.34 (1.24-1.44)‡ | 1.27 (1.20-1.34)‡ |

| Other/missing | 1.29 (1.19-1.41)‡ | 1.63 (1.50-1.78)‡ | 1.46 (1.37-1.55)‡ |

| Primary payer | |||

| Private | 0.80 (0.77-0.83)‡ | 0.90 (0.86-0.94)‡ | 0.85 (0.82-0.87)‡ |

| Public | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Missing | 0.48 (0.30-0.77)* | 0.50 (0.31-0.80)* | 0.50 (0.36-0.71)‡ |

| Donor and transplant factors | |||

| Transplant era | |||

| 2005–2008 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 2009–2012 | 0.90 (0.87-0.94)‡ | 0.89 (0.85-0.93)‡ | 0.90 (0.87-0.93)‡ |

| 2013–2015 | 0.78 (0.74-0.82)‡ | 0.70 (0.67-0.74)‡ | 0.76 (0.73-0.79)‡ |

| 2016–2018 | 0.67 (0.62-0.71)‡ | 0.57 (0.53-0.62)‡ | 0.63 (0.60-0.66)‡ |

| Donor type | |||

| Standard criteria donor | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Expanded criteria donor | 1.15 (1.09-1.22)‡ | 1.37 (1.28-1.46)‡ | 1.20 (1.15-1.26)‡ |

| Donation after circulatory death donor | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

| Living (related) donor | 0.84 (0.79-0.90)‡ | 0.78 (0.73-0.83)‡ | 0.81 (0.77-0.85)‡ |

| Living (unrelated) donor | 0.79 (0.73-0.85)‡ | 0.79 (0.73-0.86)‡ | 0.79 (0.75-0.84)‡ |

| Donor age (y) | |||

| ≤18 | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | 0.96 (0.90-1.04) | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) |

| 19–30 | 0.89 (0.84-0.93)‡ | 0.87 (0.83-0.92)‡ | 0.88 (0.85-0.92)‡ |

| 31–44 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 45–59 | 1.10 (1.06-1.15)‡ | 1.28 (1.22-1.34)‡ | 1.18 (1.15-1.22)‡ |

| ≥60 | 1.27 (1.19-1.35)‡ | 1.47 (1.35-1.60)‡ | 1.35 (1.28-1.43)‡ |

| HLA mismatches | |||

| Zero A, B, DR | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Zero DR | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 1.25 (1.14-1.37)‡ | 1.09 (1.02-1.16)* |

| Other | 1.07 (1.00-1.14)* | 1.47 (1.36-1.59)‡ | 1.21 (1.15-1.27)‡ |

| CMV status | |||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Donor (+)/recipient (–) | 1.21 (1.14-1.28)‡ | 1.17 (1.10-1.25)‡ | 1.19 (1.14-1.24)‡ |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 1.07 (1.02-1.12)* | 1.08 (1.02-1.14)* | 1.07 (1.03-1.11)† |

| Missing | 1.09 (0.98-1.21) | 1.12 (1.00-1.25)* | 1.11 (1.02-1.20)* |

| EBV status | |||

| Donor (–)/recipient (–) | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Donor (+)/recipient (–) | 1.17 (0.96-1.42) | 1.01 (0.84-1.23) | 1.07 (0.93-1.24) |

| Donor (–/+)/recipient (+) | 1.06 (0.88-1.27) | 0.94 (0.78-1.13) | 0.98 (0.85-1.12) |

| Missing | 1.11 (0.92-1.34) | 0.95 (0.79-1.14) | 1.01 (0.88-1.16) |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | |||

| 0–12 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 13–24 | 1.06 (1.02-1.11)* | 1.02 (0.97-1.07) | 1.04 (1.01-1.08)* |

| >24 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17)‡ | 1.12 (1.06-1.19)† | 1.12 (1.08-1.17)‡ |

| Missing | 1.05 (0.98-1.13) | 1.08 (1.00-1.17)* | 1.06 (1.01-1.13)* |

| Delayed graft functiona | 1.51 (1.45-1.56)‡ | 1.96 (1.89-2.05)‡ | 1.68 (1.63-1.73)‡ |

aDefined as receipt of dialysis within the first wk of transplant.

*P < 0.05–0.002.

†P = 0.001–0.0001.

‡P < 0.0001.

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; AZA, azathioprine; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; cPRA, calculated panel reactive antibody; CsA, cyclosporine; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies; MPA, mycophenolic acid; mTORi-based, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; Pred, prednisone; Tac, tacrolimus.

The incidence of death and graft failure at 1 and 5 y posttransplant according to type of induction therapy and presence or absence of delayed graft function is presented in Figure S1 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TXD/A348). For recipients who did not experience delayed graft function, dual induction with IL2rAb + ATG was associated with a 30% increase in the 1-y risk of death, DCGF, and ACGF, compared with ATG alone and a 15% increase at 5 y (Table 4). One-year outcomes were similar between the IL2rAb-alone and ATG-alone induction groups. Recipients treated with IL2rAb alone had a 7% higher 5-y risk of death than recipients treated with ATG alone, but the risk of DCGF and ACGF was similar.

TABLE 4.

Adjusted associations of type of induction therapy with posttransplant outcomes by delayed graft function (adjusted for recipient and transplant factors in Table 1)

| Outcome | Type of induction therapy | No DGF | DGF |

|---|---|---|---|

| aHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | ||

| 1-y outcomes | |||

| All-cause death | IL2rAb alone | 1.01 (0.92-1.10) | 1.22 (1.09-1.37)† |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.31 (1.11-1.56)* | 1.23 (1.03-1.47)* | |

| Death-censored graft failure | IL2rAb alone | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.32 (1.08-1.61)* | 1.00 (0.85-1.17) | |

| All-cause graft failure | IL2rAb alone | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 1.06 (0.98-1.15) |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.31 (1.15-1.50)‡ | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) | |

| 5-y outcomes | |||

| All-cause death | IL2rAb alone | 1.07 (1.02-1.12)* | 1.13 (1.06-1.21)† |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.14 (1.04-1.25)* | 1.12 (1.01-1.25)* | |

| Death-censored graft failure | IL2rAb alone | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.15 (1.05-1.27)* | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | |

| All-cause graft failure | IL2rAb alone | 1.03 (0.99-1.06) | 1.08 (1.02-1.14)* |

| ATG alone | Referent | Referent | |

| IL2rAb + ATG | 1.14 (1.07-1.22)† | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) | |

*P < 0.05–0.002.

†P = 0.001–0.0001.

‡P < 0.0001.

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CI, confidence interval; DGF, delayed graft function; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies.

For recipients who did experience delayed graft function, the 1- and 5-y outcomes with IL2rAb alone and IL2rAb + ATG were similar to ATG-alone induction. For example, compared with ATG alone, the 1- and 5-y risk of death was higher in recipients treated with IL2rAb alone (aHR, 1 versus 5 y: 1.091.221.37 versus 1.061.131.21) or IL2rAb + ATG induction (aHR, 1 versus 5 y: 1.031.231.47 versus 1.011.121.25). The 1- and 5-y risk of graft failure was similar between IL2rAb alone and IL2rAb + ATG compared with ATG-alone induction.

DISCUSSION

In this large national study of 157 351 kidney transplant recipients in the United States, we found that dual induction therapy with IL2rAb + ATG induction occurred in 5% of transplant recipients and 14% of all transplants treated with IL2rAb. Compared with IL2rAb-alone induction, the strongest predictors of dual induction therapy included Black race, cPRA ≥80%, prednisone-sparing maintenance immunosuppression, more recent transplant eras, longer cold ischemia time, and delayed graft function. Recipients of IL2rAb + ATG dual induction had an increased risk of death, DCGF, and ACGF at 5 y posttransplant than those who received ATG alone. In the subset of recipients who experienced delayed graft function, risk of death in the IL2rAb + ATG group was 12% higher than in the ATG-alone group, but the risk of graft failure was not significantly different between the 2 groups at 5 y posttransplant.

Our study is an extension of a smaller, single-center Canadian study of 430 kidney transplant recipients that found that dual induction therapy occurred in 7% of transplants and 9% of all transplants treated with IL2rAb.3 Most (78%) of the dual induction therapy group received IL2rAb initially followed by ATG on postoperative day 1 or 2. The mean cumulative ATG dose per patient was similar to that of the ATG-alone group (5.8 versus 6.4 mg/kg, P = 0.4), but they received half the IL2rAb dose that the IL2rAb-alone group did (24 versus 40 mg, P < 0.0001). Unfortunately, the induction therapy data submitted to the SRTR do not contain detailed information on timing or dosage of drug given. It is likely that a similar pattern of use occurred in this US cohort of kidney transplant recipients, wherein recipients deemed to be at low immunologic risk are initially treated with IL2rAb and then converted to ATG because of an event, such as slow or delayed graft function. In the Canadian study, the unplanned use of dual induction therapy was associated with a longer hospitalization than either IL2rAb or ATG induction alone and worse graft function at 1 y compared with ATG alone (mean creatinine, 2.6 versus 1.5 mg/dL, P = 0.0004; mean estimated glomerular filtration rate, 42 versus 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.0008). Similar to the current study, the dual induction therapy group also had an increased risk of graft failure after a follow-up of 3 y, suggesting that poor outcomes occur when there is a misjudgment of immunologic risk. A better understanding of the factors most predictive of receiving dual induction therapy may result in the upfront use of ATG alone, sparing overexposure to immunosuppression and its related cost and complications. In this study, many high-risk characteristics were associated with IL2rAb + ATG use compared with IL2rAb alone use, including Black race, cPRA ≥80%, and retransplant, that were similarly found in the ATG-alone recipients.5

In the current study, another possibility may be that the use of dual induction therapy was intentional rather than unplanned. Some US (many from the University of Miami)6-15 and international centers16-22 have used different induction combinations in kidney-alone6,7,10,12,13,15,16,18-21 and kidney-pancreas transplants,8,9,11,14,17,22 as per center protocol9,14,17,19-22 or clinical trial6-8,10-13,15,16,18 (Table 5). The combination of IL2rAb + ATG induction may result in the prolonged depletion of CD3 lymphocyte counts, similar to ATG alone, with more significant prolonged depletion of CD25 cells compared with ATG alone.12 Some studies have shown that the combined use of IL2rAb and low-dose ATG may be associated with a lower rate of rejection and viral infection compared with standard-dose ATG induction.12,16,19,21 This may be a useful strategy for older recipients, who often receive kidneys from older donors and are at high risk of delayed graft function but may not tolerate standard-dose ATG induction because of concerns about overimmunosuppression.18,19 Also, achieving early and effective lymphocyte depletion with dual induction therapy may allow for delayed introduction of calcineurin inhibitors, early steroid withdrawal, and possible lower daily dosages of maintenance immunosuppression.6,7,10,13,17-19,21 Additional combinations, including the use of alemtuzumab (an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) with ATG, also show promising results in suppressing peripheral T cells and preventing rejection.12,13 Last, there may be the added benefit of cost-efficacy associated with dual induction therapy if low-dose ATG is used compared with standard-dose ATG alone.12,16 One study reported a per-patient treatment savings of about €3000 ($3800 USD) with planned IL2rAb + low-dose ATG compared with standard-dose ATG induction.16 Obviously, these cost savings would be negated in the unplanned use of dual induction therapy if standard dosing of both agents were subsequently used.

TABLE 5.

Summary of studies reporting use of combination induction therapy in kidney or kidney-pancreas transplant recipients

| Author (year), place | Study type planned vs unplanned use | Recipients (y) | Induction therapy regimen | Patient and graft survival outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL2rAb or other (%; dose) | ATG (%; dose) | ||||

| Lam et al (2020), USA | Multicenter Retrospective Planned + Unplanned |

157 351 kidney-only (2005–2018) | Basi alone (29%; dose N/A) Basi (dose N/A) + ATG (5%) |

ATG alone (67%; dose N/A) Basi + ATG (dose N/A) |

5-y incidence of death: IL2rAb + ATG: 15% ATG alone: 12% 5-y incidence of DCGF: IL2rAb + ATG: 12% ATG alone: 10% 5-y incidence of ACGF: IL2rAb + ATG: 23% ATG alone: 19% |

| Jeong et al (2020),3 Edmonton, AB, Canada | Single center Retrospective Unplanned |

430 kidney-only (2013–2018) | Basi alone (71%; mean cumulative dose 40 mg/patient) Basi (mean cumulative dose 24 mg/patient) + ATG (7%) |

ATG alone (22%; mean cumulative dose 6.3 mg/kg) Basi + ATG (mean cumulative dose 5.8 mg/kg) |

Death (median follow-up, 3 y): IL2rAb alone: 5.6% ATG alone: 10.8% IL2rAb + ATG: 21.9% DCGF (mean follow-up, 3 y): IL2rAb alone: 2.0% ATG alone: 4.3% IL2rAb + ATG: 15.6% ACGF (mean follow-up, 3 y): IL2rAb alone: 6.9% ATG alone: 12.9% IL2rAb + ATG: 31.3% |

| Ciancio et al (2018),23 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

200 kidney-only (2006–2009) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (50%) Alem (0.3 mg/kg × 1) + ATG (50%) |

Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) Alem + ATG (1 mg/kg × 1) |

8.5-y survival: Graft (death-censored): 88% |

| Li et al (2018),17 Hamburg, Germany | Single center Retrospective Planned |

25 SPK (2009–2015) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (low dose: 1–1.5 mg/kg; mean cumulative dose 100 mg/patient) | 1-y survival: Patient: 100% Pancreas: 95.8% Kidney: 100% 5-y survival: Patient: 94.4% Pancreas: 95.8% Kidney: 100% |

| Spagnoletti et al (2017),19 Rome, Italy | Single center Retrospective Planned |

235 kidney-only (2007–2017) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (200 mg total over 3 d) | 8-y survival: Patient: 83% Graft: 74% |

| Ciancio et al (2017),13 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

200 kidney-only (2006–2009) | Dac (1 mg/kg x 2) + ATG (50%) Alem (0.3 mg/kg × 1) + ATG (50%) |

Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) Alem + ATG (1 mg/kg × 1) |

Survival (median follow-up, 8 y): Patient: 89% Graft: 79% |

| Ciancio et al (2016),15 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

30 kidney-only (2011–2014) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (1 mg/kg × 2) | 1-y survival: Patient: 100% Graft: 100% |

| Gentile et al (2015),21 Bergamo, Italy | Single center Matched cohort Planned |

48 kidney-only (2004–2011) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (67%) | ATG alone (33%; 0.5 mg/kg/d × 7) Basi + ATG (0.5 mg/kg/d × 7) |

18-mo survival: Patient: 100% Graft: 100% |

| Sageshima et al (2014),14 Miami, FL | Single center Retrospective Planned |

25 SPK (2011–2013) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (1 mg/kg × 5) | Survival (median follow-up, 14 mo): Patient: 100% Kidney: 96% Pancreas: 100% |

| Ciancio et al (2012),24 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

170 SPK (2000–2009) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 5) | 10-y survival: Patient: 82% Kidney (death-censored): 84% Pancreas (death-censored): 95% |

| Gennarini et al (2012),20 Bergamo, Italy | Single center Matched cohort Planned |

75 kidney-only (2004–N/A) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (0.5 mg/kg × 7) | 1-y survival: Patient: 100% Graft: 100% |

| Ciancio et al (2011),6 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

200 kidney-only (2006–2009) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (50%) Alem (0.3 mg/kg x 1) + ATG (50%) |

Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) Alem + ATG (1 mg/kg × 1) |

2-y patient survival: IL2rAb + ATG: 96% Alem + ATG: 92% 2-y graft survival: IL2rAb + ATG: 91% Alem + ATG: 83% |

| Sageshima et al (2011),12 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

236 kidney-only (2002–2006) | Dac alone (16%; 1 mg/kg × 5) Alem alone (17%; 0.3 mg/kg × 2) Alem (0.3 mg/kg x 1) + ATG (26%) Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (25%) |

ATG alone (16%; 1 mg/kg × 7) Alem + ATG (1 mg/kg x 1) Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) |

N/A |

| Ciancio et al (2011),10 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

150 kidney-only (2004–2006) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) | 4-y survival: Patient: 93% Graft: 81% |

| Sageshima et al (2011),11 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

50 kidney-only 88 SPK | Dac alone (54%; 1 mg/kg × 5) Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (100%) |

ATG alone (46%; 1 mg/kg × 4–7) Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 5) |

N/A |

| Favi et al (2010),18 Rome, Italy | Single center Prospective Planned |

46 kidney-only (2007–2009) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Basi + ATG (200 mg total over 3 d) | 6-mo survival: Patient: 98% Graft: 96% |

| Ciancio et al (2008),7 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

150 kidney-only (2004–2006) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Dac + ATG (1 mg/kg × 3) | 1-y survival: Patient: 99% Graft: 97% |

| Ruggenenti et al (2006),16 Bergamo, Italy | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

33 kidney-only (2000–2003) | Basi (20 mg × 2) + ATG (52%) | Basi + ATG (low dose: 0.5 mg/kg/d up to 7 d) ATG alone (48%; standard dose: 2 mg/kg/d up to 7 d) |

6-mo patient survival: IL2rAb + ATG: 100% ATG alone: 100% 6-mo graft survival: IL2rAb + ATG: 100% ATG alone: 94% |

| Schulz et al (2005),25 Bochum, Germany | Single center Retrospective Planned |

25 SPK (1999–2000) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 5) + ATG (100%) | Dac + ATG (4–6 mg/kg × 1) | 3-y survival: Patient: 100% Kidney: 92% Pancreas: 84% |

| Burke et al (2002),9 Miami, FL | Single center Retrospective Planned |

55 SPK (1999–2001) | Dac alone (36%; 1 mg/kg × 5) Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (11%) Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (53%) |

Dac + ATG (1.5 mg/kg × 5) Dac + ATG (1.0–1.5 mg/kg × 5) |

2-y survival: Patient: 100% Kidney: 100% Pancreas: 98% |

| Burke et al (2002),8 Miami, FL | Single center Randomized trial Planned |

42 SPK (2000–2001) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 2) + ATG (100%) | Dac + ATG (1.0–1.5 mg/kg × 5) | Survival (mean follow-up 6 mo): Patient: 100% Pancreas: 98% Kidney: 100% |

| Dette et al (2002),22 Bochum, Germany | Single center Retrospective Planned |

31 SPK (2000–2001) | Dac (1 mg/kg × 5) + ATG (32%) | ATG alone (2.5 mg/kg × 1) Dac + ATG (2.5 mg/kg × 1) |

3-mo survival: Patient: 97% Kidney: 97% Pancreas: 90% |

ACGF, all-cause graft failure; Alem, alemtuzumab; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; Basi, basiliximab; Dac, daclizumab; DCGF, death-censored graft failure; IL2rAb, interleukin-2 receptor-blocking antibodies; N/A, not applicable/available; SPK, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation.

Our study has a number of strengths, including the use of a national registry to study induction therapies in >150 000 kidney transplant recipients. Our large sample size allowed us to perform subgroup analyses to delineate the outcomes based on the presence or absence of delayed graft function, likely a strong indication for dual induction therapy use. We found that when delayed graft function occurred, recipients treated with IL2rAb alone or IL2rAb + ATG induction had a similar increased risk of death as recipients treated with ATG alone, with no appreciable increased risk of graft failure. The IL2rAb-alone group with delayed graft function was not treated with ATG initially or adjunctively because of either concern about nonimmunologic causes for delayed graft function or concern about ATG tolerability, such as recipient frailty or comorbidities. Our exploratory analyses suggest that further research is needed to better understand the prognostic indicators associated with poor outcomes and whether the addition of ATG to IL2rAb in the setting of delayed graft function affects long-term patient and graft survival.

There are limitations worth noting. As mentioned, the SRTR does not collect data on induction scheduling or dosing, so we were unable to determine the order or timing of dual induction therapy or compare the cumulative dosing received between the groups. Although data from the SRTR differentiate use between induction versus rejection therapy, SRTR does not collect information on rationale for choice of regimen; thus, we were unable to determine if the use of dual induction therapy was planned versus unplanned. The database lacked complete information on variables that may be confounders for induction therapy use and outcomes of death and graft failure, including frailty, perioperative hypotension, and bleeding risk. Also, we did not have comprehensive data on biopsy-proven rejection (including pathology results) or subsequent treatment of rejection in our national data set. However, we were able to distinguish between the use of IL2rAb and ATG as induction therapy versus rejection therapy. As previously discussed, there is the potential for confounding by indication, wherein recipients of dual induction therapy had worse outcomes due to the indication for IL2rAb + ATG, such as slow or delayed graft function, rather than the therapy itself. In our study, we were able to perform subgroup analyses by the presence or absence of delayed graft function to explore this possibility. We also focused our analyses on IL2rAb and ATG induction and did not include other induction regimens such as alemtuzumab, as this was beyond the scope of our research question but warrants further investigation based on our findings. Finally, as this was an observational study, we are only able to describe correlates and outcomes of IL2rAb + ATG induction and cannot infer that interventions aimed at reducing the use of dual induction therapy will improve outcomes.

Induction therapy is the most potent immunosuppression used immediately posttransplant to prevent acute rejection but at a risk of potential morbidity and mortality that may negate any potential benefit related to prolonging graft survival. Our study suggests that 1 in 20 kidney transplant recipients receive both IL2rAb + ATG for induction therapy and that these recipients have an increased risk of death and graft loss compared with those who receive ATG alone. Ideally, induction therapy is tailored to the individual’s immunological risk profile to optimize lymphocyte depletion while minimizing toxicity and associated costs. This risk assessment profile considers many recipient and donor factors, and there are currently no validated prediction tools to help physicians make decisions when it comes to choosing the right type or combination of induction therapy for a given patient. Further research is needed to develop risk-prediction tools to guide the safe and optimal induction protocol for kidney transplant recipients. Better tools are needed to identify recipients who may benefit from planned dual induction therapy while avoiding its unplanned use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was conducted under the auspices of the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, contractor for the SRTR, as a deliverable under contract no. HHSH250201000018C (US Department of Health and Human Services, HRSA, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation). The US Government (and others acting on its behalf) retains a paid-up, nonexclusive, irrevocable, worldwide license for all works produced under the SRTR contract, and to reproduce them, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government. The authors thank Mary Van Beusekom for article editing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 23 July, 2021.

N.N.L. conceived of the study and drafted the article. N.N.L. and K.L.L. participated in study design and interpreted the results. H.X. performed the data analysis. All authors contributed to and approved the final article.

K.L.L., M.M.D., D.A.A., and M.A.S. received funding from a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) R01DK120518. K.L.L. is supported by the Mid-America Transplant/Jane A. Beckman Endowed Chair in Transplantation.

K.L.L. serves on the Sanofi-Genzyme speakers bureau. D.A.A. is a consultant to Sanofi-Genzyme. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board. Individual participant deidentified data will not be shared by the authors due to the restrictions of data use agreements. SRTR registry data can be obtained from the SRTR.

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantationdirect.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(suppl 3):S1–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster AC, Ruster LP, McGee RG, et al. Interleukin 2 receptor antagonists for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD003897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong R, Quinn RR, Lentine KL, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of kidney transplant recipients treated with both basiliximab and antithymocyte globulin. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharnidharka VR, Naik AS, Axelrod DA, et al. Center practice drives variation in choice of US kidney transplant induction therapy: a retrospective analysis of contemporary practice. Transpl Int. 2018;31:198–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD, et al. ; Thymoglobulin Induction Study Group. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1967–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, Sageshima J, et al. Randomized trial of dual antibody induction therapy with steroid avoidance in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92:1348–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciancio G, Burke GW, Gaynor JJ, et al. Randomized trial of mycophenolate mofetil versus enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium in primary renal transplant recipients given tacrolimus and daclizumab/thymoglobulin: one year follow-up. Transplantation. 2008;86:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke G, 3rd, Ciancio G, Figueiro J, et al. Can acute rejection be prevented in SPK transplantation? Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1913–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke GW, 3rd, Ciancio G, Figueiro J, et al. Steroid-resistant acute rejection following SPK: importance of maintaining therapeutic dosing in a triple-drug regimen. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1918–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, Zarak A, et al. Randomized trial of mycophenolate mofetil versus enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium in primary renal transplantation with tacrolimus and steroid avoidance: four-year analysis. Transplantation. 2011;91:1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sageshima J, Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, et al. Addition of anti-CD25 to thymoglobulin for induction therapy: delayed return of peripheral blood CD25-positive population. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E132–E135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sageshima J, Ciancio G, Guerra G, et al. Prolonged lymphocyte depletion by single-dose rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin and alemtuzumab in kidney transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2011;25:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, Guerra G, et al. Randomized trial of rATg/Daclizumab vs. rATg/Alemtuzumab as dual induction therapy in renal transplantation: results at 8 years of follow-up. Transpl Immunol. 2017;40:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sageshima J, Ciancio G, Chen L, et al. Everolimus with low-dose tacrolimus in simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciancio G, Tryphonopoulos P, Gaynor JJ, et al. Pilot randomized trial of tacrolimus/everolimus vs tacrolimus/enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium in adult, primary kidney transplant recipients at a single center. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2006–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggenenti P, Codreanu I, Cravedi P, et al. Basiliximab combined with low-dose rabbit anti-human thymocyte globulin: a possible further step toward effective and minimally toxic T cell-targeted therapy in kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Koch M, Kramer K, et al. Dual antibody induction and de novo use of everolimus enable low-dose tacrolimus with early corticosteroid withdrawal in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2018;50:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Favi E, Gargiulo A, Spagnoletti G, et al. Induction with basiliximab plus thymoglobulin is effective and safe in old-for-old renal transplantation: six-month results of a prospective clinical study. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1114–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spagnoletti G, Salerno MP, Calia R, et al. Thymoglobuline plus basiliximab a mixed cocktail to start? Transpl Immunol. 2017;43–44: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gennarini A, Cravedi P, Marasà M, et al. Perioperative minimal induction therapy: a further step toward more effective immunosuppression in transplantation. J Transplant. 2012;2012:426042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentile G, Somma C, Gennarini A, et al. Low-dose RATG with or without basiliximab in renal transplantation: a matched-cohort observational study. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dette K, Woeste G, Schwarz R, et al. Daclizumab and ATG versus ATG in combination with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids in simultaneous [correction of simultaneus] pancreas-kidney transplantation: analysis of early outcome. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1909–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, Guerra G, et al. Antibody-mediated rejection implies a poor prognosis in kidney transplantation: results from a single center. Clin Transplant. 2018;32:e13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciancio G, Sageshima J, Chen L, et al. Advantage of rapamycin over mycophenolate mofetil when used with tacrolimus for simultaneous pancreas kidney transplants: randomized, single-center trial at 10 years. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3363–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulz T, Flecken M, Kapischke M, et al. Single-shot antithymocyte globuline and daclizumab induction in simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant recipient: three-year results. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1818–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.