Abstract

This investigation analyzes the main contributions that additive manufacturing (AM) technology provides to the world in fighting against the pandemic COVID-19 from a materials and applications perspective. With this aim, different sources, which include academic reports, initiatives, and industrial companies, have been systematically analyzed. The AM technology applications include protective masks, mechanical ventilator parts, social distancing signage, and parts for detection and disinfection equipment (Ju, 2020). There is a substantially increased number of contributions from AM technology to this global issue, which is expected to continuously increase until a sound solution is found. The materials and manufacturing technologies in addition to the current challenges and opportunities were analyzed as well. These contributions came from a lot of countries, which can be used as a future model to work in massive collaboration, technology networking, and adaptability, all lined up to provide potential solutions for some of the biggest challenges the human society might face in the future.

Keywords: Additive manufacturing, Covid-19, Coronavirus, 3D printing

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing is a disruptive technology with very significant reaches in the actual crisis, the pandemic, with applications include protective masks, mechanical ventilator parts, social distancing signage, and parts for detection and disinfection equipment (Ju, 2020) [1]. Crisis scenarios raise problematic situations that need to be solved through the implementation of innovative solutions within a crisis management framework [2]. Disaster risk management (DRM) seeks to help states prepare for adverse impacts of disasters [3]. DRM comprises three phases: before, during and after the disaster. The first phase includes risk identification and assessment, as well as prevention to mitigate risks; The second phase includes the response to the emergency that includes rescue, relief and recovery; and the third phase has to do with resilience and repair, aiming for a quick recovery. Successful implementation of DRM strategies depends both on government policies and on the development of reaction capacities that allow disasters to be adequately managed [4]. In this sense, the provisions implemented by the affected countries to mitigate the COVID-19 contingency have generated a significant economic impact worldwide [5].

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 is one of the biggest challenges faced by the human society of the modern era due to the mortality (up today more than 600,000 deaths in the world), detrimental effects in the health care system, social issues, and tremendous economic implications worldwide, now comparable to some of the scenes since the World War Two [6]. One of the main issues related to COVID-19 is that is highly contagious when compared to other world diseases in the past [7], and including asymptomatic carriers in mechanisms still matter of investigation [8]. The economic recovery is still very uncertain, but in all cases predicted with long and adverse effects in a long period of time [9]. During this global threat, the manufacturing sector as other economic areas has suffered with major global threat; the manufacturing sector as other economic areas has suffered with major job cuts [10] and market lost [11], with all the society consequences that this can produce. Although almost all economic sectors have been affected adversely, additive manufacturing (AM) or 3D Printing has been anointed as a lifesaver and promoter of new businesses during the pandemic, showing a high adaptability to this complex situation elsewhere, as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Additive manufacturing has been a symbol of the manufacturing industry for supporting the pandemic.

Additive manufacturing has been one of the more rapidly growing technologies worldwide in the recent decades due to its versatility in manufacturing simple as well as very complex geometries, for its use of almost any type of raw material, and because it produced new business models from large scale high production to even home production for everyone. AM is a technology where a part is fabricated by adding layer by layer of material controlled from a computer-generated 3D model [12], where the shapes can be produced by design with computer aided design (CAD) software, or by scanning of objects via 3D scans or tomography techniques [13]. Remarkably, one of the key advantages of this technology is the almost limitless to produce any complex geometry with almost any type of material [14,15], education strategies [16], circular economy [17,18], and other characteristics not found in other manufacturing technologies.

Among the main contributions from AM technology to provide solutions for COVID-19 disease are the protective masks [19], mechanical ventilator parts [20], and COVID sampling [21]. Therefore, the main applications are in critical health supplies, which is essential not only for people surviving the pandemic, but also important for keeping the operations of nations, which would be the most important contribution of AM up to now. Thus, the present investigation explores the current contributions of AM during the pandemic, including the materials, the methodologies, and the current state of the art according to various databases, networking of important groups worldwide, and companies.

Taking the above into account, this paper presents an analysis of the strategies and alternatives offered by AM technologies to assist health personnel in DRM work. This will invariably be a key factor in mitigating the aftermath of future claims, making it possible to devise strategies that reduce the subsequent adverse effects of this type of disaster.

2. Methodology

The methodology followed in this paper is based on a systematic review of formal academic sources (peer review publications: research articles, editorials, review papers and letters to the editor); and other more informal sources such as company information from the internet and networks. This approach was selected for several reasons, which include: the importance of the academic community in the progress of AM contributions to the COVID-19 disease, with the main new scientific and technical achievements; the increasing industrial sector in this area, acting as a motor for the applications and implementation of the first, and its rapid adaption to the new reality draw by the pandemic situation; and finally, the networks created worldwide, showing a new way to work in collaboration, in some cases with goals beyond the academic reputation or the economy obsession.

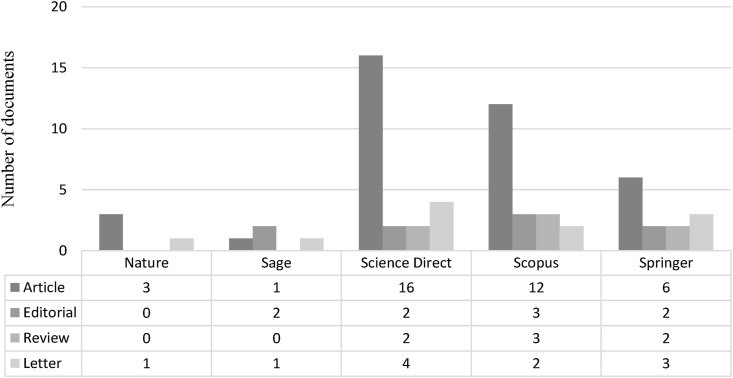

The bibliographic review was carried out with information compiled until June 24, 2020, through one of a thorough exploration in databases of five internationally recognized databases: Nature, Sage, Science Direct, Scopus, and Springer. The search was conducted taking into consideration four kinds of publications: (1) research articles, (2) editorials, (3) review articles, and (4) letters to the editor. The results were obtained from the specific keywords (covid AND (“3D printing” OR “additive manufacturing”)). Of the analyzed works, 38 were research articles, 11 letters to the editor, 10 editorials, and 7 review articles. A classification according to the type of document is shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Number of publications found in the consulted databases.

Regarding the information of companies, a search using the internet via Google search was performed combining some company names and the term COVID-19. In this way, several specific sections were found within the main page of each one where it is shown in general what each company does, how it does it, and how the external community can either request or provide help or support to the problem. In this way, the type of parts that could be manufactured by each additive manufacturing technology could be established. The selection of the company names was based on reviews that cite the main industrial leaders in the area of AM.

Also, not only the bibliographic review, the main companies and networks against the COVID-19 were analyzed, but also the information was organized in tables, and important aspects from this information such as the AM technologies with their manufacturing issues, the printing materials, the disinfectants for Coronavirus (COVID-19), applications, and other aspects were systematically analyzed and the information organized in tables.

3. Results

3.1. Networks and 3D printing companies working against the Covid-19 pandemic

Table 1 shows a comparison of the actual and potential production capacity of some of the companies, which have intervened in the manufacturing of parts that somehow support the deficit of personal protective equipment (PPE) and other essential elements to combat the pandemic.

Table 1.

Companies utilizing 3D printing to provide medical supplies during COVID-19 pandemic [22].

| Company | Country | medical supplies | potential weekly production capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consortium - Formlabs, Carbon, EnvisionTec, and Origin | United States | nasophryngeal swabs | 4,000,000 |

| Nexa3D | United States | Test swabs | 500,000 |

| Face shields | 10,000 | ||

| Stratasys & Origin | United States | Nasopharyngeal swabs | 950,000a |

| Nissan | Japan | Face shields | 100,000 |

| Voodoo Manufacturing | United States | Face shields and swabs | 2500 |

| Swabs | 50,000 | ||

| Ricoh 3D | UK | Face shields | 40,000 |

| 3D Hubs | Netherlands | Face shields | 20,000a |

| Forecast 3D | United States | Face shields, nasopharyngeal swabs, stopgap masks, and other PPE products | 50,000a |

| Prusa Research | Czech Republic | Face shields | 10,000 |

| Mobility/Medical goes Additive consortium | Germany | Face shields | 5000 |

| Unnamed/unknown (Large-scale PPE manufacturer) | China | Safety googles | 10,000a |

| Stratasys | United States | Full-face shields | 5,000a |

| Protolabs | France | Ventilator components | 3,000a |

| Fast Radius | United States | Face shield | 50,000a |

| Azul3D | United States | Face shields | 20,000a |

| SmileDirectClub | United States | Face shields | 37,500a |

| Photocentric | UK | Valves for respirators | 40,000a |

| Y Soft 3D | Czech Republic | Face shields | 2500 |

| Weerg & PressUP | Italy | Protective visors | 500b |

| BCN3D | Spain | Face shields | 2,000b |

| Formlabs | United States | Test swabs | 375,000a |

| Photocentric | UK | Face shield parts | 24,300 |

| Omni3D | Poland | Face shields | 600a |

| Consortium led by Leitat technology center | Spain | Pieces for respirators | 500a |

| Isinnova | Italy | Respirator valves | 2500 |

Estimated on a five day per week basis.

Units produced.

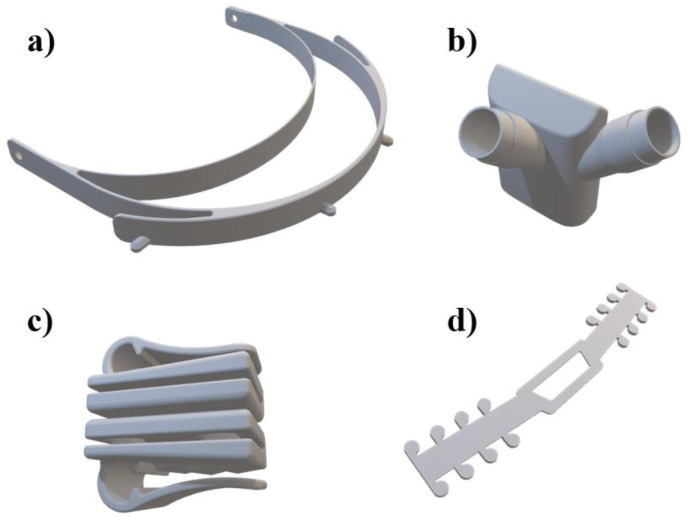

The CAD models were obtained from Thingiverse using the words PPE, Covid-19, Face shield, Mask Strap, and Ventilator Connector. Fig. 3 shows some of the models used by the local iniciative Hacer para Salvar (HxS), from Medellin, Colombia. This type of initiatives reveals a new type of super collaborative manufacturing, implying a new type of networking with companies and individuals working at industrial and individual or home levels. In the case of HxS, it has more than 150 participants, including companies, doctors, designers, and manufacturers. Up to now, 19,000 donated masks have been delivered, from which more than 15,000 come from companies and the rest from independent makers. Donations were made by ordinary people and companies through bank consignments and raw printing materials (PETG, PLA, ABS), acetates, or connecting parts. The printing process, disinfection of the fabricated materials according to the local standards for medical use, and assembly are mostly voluntary works made in a significant part for university students. The magnitude of the 3D printing contribution is just demonstrated by this relatively small-scale network, which is working in similar ways in many countries and has a larger scale in Asia, USA, and Europe. Certainly, the current worldwide situation revealed new needs, and the AM technologies showed both high adaptability and collaborative skills.

Fig. 3.

a) Face shield (HxS) b) Ventilator connector c) Clips for alternative face shield (HxS) d) face mask strap [27].

According to the information collected and the statements made in notes such as in the Additive Manufacturing Magazine [23], the 3D printed parts with the greatest impact to date are nasopharyngeal swabs due to the great shortage created by the pandemic [24]. Swabs open the category of testing, and face shields, along with masks, and connectors of ventilators or valves would enter a classification of medical equipment, with the second place on impact and over 100 different 3D printable designs [25]. Finally, the objects that have been very useful but perhaps with less media impact are accessories used not only the medical personnel but for anyone elsewhere.

(Fig. 3a) shows the main part of the face shield fabricated by HxS, which for this specific case is made up of three parts (3D printed piece, acetate, and elastic) that are assembled for final use. (Fig. 3b) is a part of a ventilator connector. (Fig. 3c) shows clips to be used in combination with acetate instead the conventional face shield, being more practical for users who are not directly exposed to sick patients, and adaptable to be used with glasses, caps, helmets, and elastics. These clips are also recommended for food and construction industry. (Fig. 3d) is a face mask trap, which is an accessory that avoids the contact of the elastics of the mask with the ears. There are a lot more applications and designs that include glasses frames adapted for COVID19 and swab 3D models, which depend of the company and can be printed with vat photopolymerization, FDM, or HP Jet Fusion printers with the typical materials such as resins and thermoplastics [24,26].

Besides the clear contribution of AM technology to the current COVID19 pandemic, it is important to know that the collaborative fabrication must be carefully coordinated to fulfill the appropriate technical high standards that medical equipment requires, in strict accordance with recommendations made by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [28]. Other recommendations regarding the printing technologies itself include if printing with FDM, it is recommended to use PETG or PLA and avoid using bed adhesives; while when printing with stereolithography, it is recommended to use approved resins for medical applications, and follow carefully the company's recommendations [[29], [30], [31]].

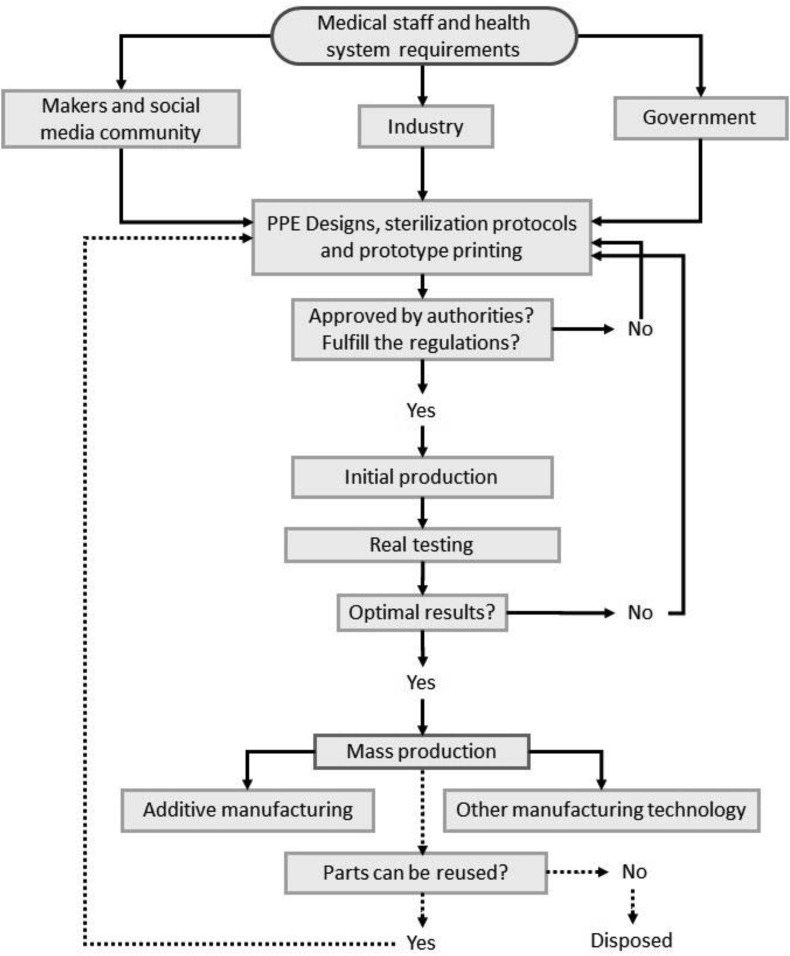

A general model showing the collaboration related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the AM technologies is presented in Fig. 4 , which summarizes most of the path followed elsewhere [25] and also in Colombia with the local initiative HxS. The process starts with support requirement from the medical personnel or health system, and there are three main options to respond to this demand: the traditional are industry (or private sector) and government (or official sector), who may supply the needs for keep the system operating. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic emerged makers and social media as a powerful networking with the advantage of quick adaptation and response to changes. This 3D printing community existed from long before [32] this global emergency, and therefore the response was quick and natural. In all cases, the applicant must carry out a survey to classify the level and type of need. From here it is defined what type of pieces they require, if there is already a printed design and prototypes or the require design. These must be approved by the respective authority and fulfil the necessary regulations, before starting to produce a small quantity to be tested under real conditions during a specific time interval. In case there is not approval process, the technical parameters must be adapted until the protocols are followed. If the design, manufacturing process, and sometimes disinfection are finally approved and validated in a small scale with real tests and with positive results, a mass production can begin and the process can be developed with AM, with other manufacturing technology or with a combination of techniques. Many of the PPE are manufactured to be for single use, but in countries with insufficient supply capacity, it is necessary to look for alternatives to reuse parts or to design them to be reusable. An alternative is disinfection over selected parts and materials that allow them to meet quality, regulations, and health standards compliance [33].

Fig. 4.

Flowchart showing the general overview of the strategy for AM supporting COVID-19.

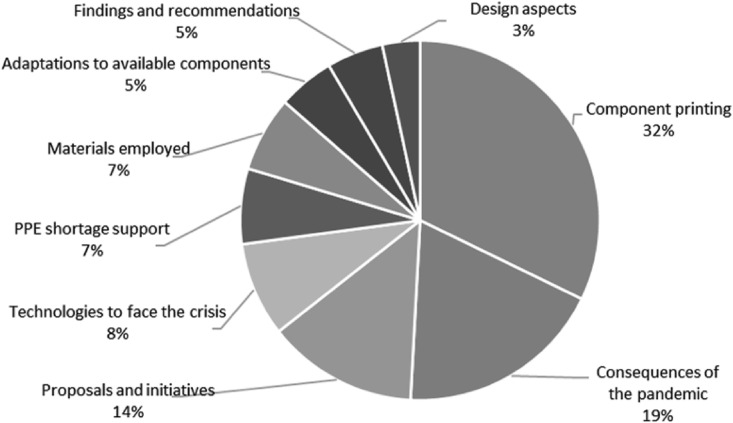

3.2. Bibliographic review

In the initial search, 95 articles were found, of these, 80 were chosen after the relevance and deduplication of classification. From these, 59 articles were exposed to in-depth review, which were classified into nine categories, namely: design aspects, printing of components, support in the face of a shortage of PPE, consequences of the pandemic, technologies to cope with the crisis, proposals and initiatives, adaptations to available components, materials used, and recommendations. From these, the categories of greatest contribution were the printing of components and consequences of the pandemic, with 19 and 11 respectively, as shown in Fig. 5 . The most revealing aspects of this exploration are presented below.

Fig. 5.

Proportion of articles reviewed according to the proposed classification.

4. COVID 19 and manufacturing issues

Likewise, the current world situation has generated a series of implications that, in the end, promote development in various aspects. Among these, van Barneveld et al. [34], suggest that COVID-19 will activate some technological transformations, among them, developments in 3D printing and generating consequences in work activities. For his part, Queiroz et al. [35] exposes the urgency to explore 3D printing to effectively and successfully support the development of hospital components. Furthermore, they suggest that digital manufacturing and Industry 4.0 will likely play a key role in overcoming traumatic circumstances in supply chains. Likewise, to reduce the possibility of damages due to possible complications in the supply chain and insufficient raw materials, it is necessary to have provisions close to consumers, which will surely favor emerging technologies such as 3D printing and different forms of commercial activities [36]. On the other hand, the lack of fans and facial protection elements have led professionals to use their experiences to design scalable options applying technologies such as 3D printing to meet the needs of health services [37,38]. Besides, Ivanov proposes a supply chain model that incorporates aspects of agility, resilience, and sustainability through adaptation and recovery activities that include a technological structure, which incorporates additive manufacturing, robotics, smart production, and industry 4.0. Bagaria and Sahu [39] suggest the current times of crisis have directed us to transform our reality and deploy 3D printing and artificial intelligence skills to propose novel solution alternatives. In addition, Acuto [40] notes the COVID-19 has fueled teleworking and creating web-based clusters that promote 3D printing of components ranging from test swabs to fans.

On the other hand, the current global pandemic situation has unleashed a series of challenges in many aspects, including an unforeseen shortage of PPE. In this sense, Vordos et al. [25] presented an analysis on how 3D printing and social networks have addressed the shortage of PPE. For their part, Iyengar et al. [41], pose some challenges and solutions in relation to the urgency of producing PPE for patients with COVID-19. However, the 3DP printable elements that are currently available on the web do not meet some requirements, especially in aspects related to the comfort and time required for their manufacture [42]. To address this shortage, Ishack and Lipner [43] propose 3D printing as a very convenient technology to produce complex elements.

Another approach, in relation to the sudden needs for medical supplies to face the current crisis, consists of adapting commercially available elements. Among these initiatives, Thierry et al. [44] adapted a diving mask as PPE using four components made using 3DP. On the other hand, Erickson et al. [45], using 3DP modified a helmet to be used as PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, Dente and Hashimoto have proposed the use of snorkel masks adapted to hospital ventilators.

5. AM technologies during COVID-19

Recent technological development opens up a series of alternatives that could be quite beneficial to respond to a global public health contingency. According to Vaishya et al. [46,47], it is necessary to use several of the recent engineering-based technologies like big data, artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing, internet of things, blockchain, cloud computing, and 5G technologies, plus others. Mazingi et al. [48,49] propose to reduce the adherence to global supply chains for PPE by locally producing affordable options, where additive manufacturing techniques gain relevance in prototype manufacturing. For his part, Mahajan [50] says that the concept of scale manufacturing is not currently important, as it requires vast manufacturing plants, as well as very large distribution and supply chains. For its part, additive manufacturing is emerging in the field of medicine for the manufacture of critical components and personalized elements [51]. For their part, Chhabra et al. [52] highlight the need for modern professionals to acquire skills in 3D printing, unmanned robotic devices, and the innovation of PPEs. Likewise, Haleem et al. [53] highlight the importance of developing future innovations with the help of new technologies such as big data, AI, and 3D printing.

6. Additive manufacturing and printing materials

Additive Manufacturing (AM) refers to the set of manufacturing production processes through which the material is increased, layer by layer, in a controlled manner based on digital models. This technology stood in contrast to the usual subtractive technologies [54]. Among the AM technologies that have shown the greatest growth during the COVID-19 contingency for applications, they mainly include those that use polymeric materials and metallic materials as raw materials. Commonly, additive techniques incorporate various processes, which present a series of advantages and disadvantages (B.A et al., 2021). In general, AM technologies can be classified into three categories, namely: powder bed fusion techniques, photopolymerization techniques, and extrusion-based methods.

Powder bed fusion techniques melt and fuse small powder particles to build 3D components. Among the materials most used with this technique are polymers, metals, ceramics and composite materials. The main technologies that make use of powder bed fusion include Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), electron-beam melting (EBM), Selective laser melting (SLM), Selective heat sintering (SHS) and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) [55]. Among its advantages is that of making possible the production of components in metallic alloys with very consistent internal structures.

For its part, photopolymerization techniques use liquid polymer resins that are cured using a UV laser to form 3D parts. Stereolithography (SLA) is the most widely used technology using this technique. Before being cured, the finished pieces are subjected to a chemical bath to eliminate excess resin [56]. Its relative advantages in relation to other techniques include its profitability, flexibility and good dimensional accuracy [55].

Finally, extrusion-based systems allow the manufacture of small-volume plastic prototypes in small-scale production. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) is the fundamental technology of extrusion-based systems, where a filament is drawn and melted by an extruder, which deposits the material precisely, layer by layer, on a printing platform [57]. Among its advantages is that of offering a wide variety of thermoplastic materials with various properties and degrees of resistance.

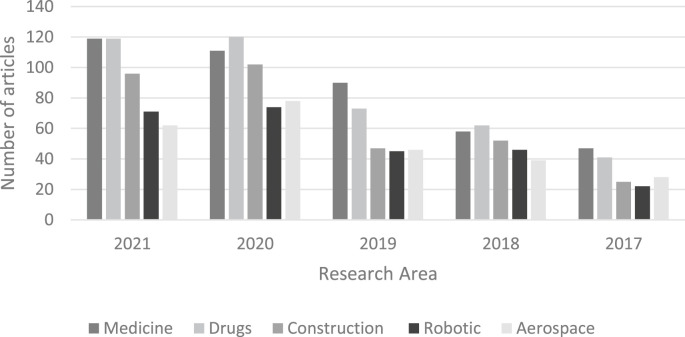

The rise of 3D printing technologies in recent years has been fundamentally derived from the development and implementation of new and diverse materials, which has allowed various industries to implement the benefits of 3D printing techniques in their processes. That is why new and improved materials emerge every day that make additive manufacturing practices increasingly accessible and versatile. Among the areas of application that have taken the greatest advantage from 3DP technologies, we can mention the areas of medicine, pharmaceuticals and construction, although, other areas such as robotics, aerospace and food have also exhibited significant attention from recent literature. Where, according to a review carried out in the Science Direct database, in the first semester of 2021, in recent years a constant increase has been observed in such research areas, as shown in Fig. 6 . In accordance with the trend shown by Fig. 6, it can be observed how, in general, all areas present an inclination to advance in the development of the state of the art, which will lead to a growing boom in the implementation of AM techniques. However, the medical and pharmaceutical areas are the ones that have benefited the most from the use of 3DP in recent years, in part due to the worldwide impact of the current health emergency.

Fig. 6.

Articles published in recent years in 3DP in different areas.

Among the 3DP technologies that have had the most application during the years affected by COVID-19 are the techniques of Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), Stereolithography (SLA) and Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) [58]. However, other technologies such as Selective laser sintering (SLS), Binder Jetting and Selective laser melting (SLM) have also been applied as a tool to try to counteract the devastating effects of the current pandemic. Each of these technologies makes use of specific materials.

In the literature review, it was found that the materials with the greatest application in this 3DP focus are thermoplastic polymers, which have been used in the manufacture of various components such as: swabs, which have been manufactured in nylon 12 [59], PETG [24], methyl-acrylate photopolymer 217 resin [60]; face masks which are manufactured in ABS [43], PLA [61]; Visors/Face shields of polyamide composite [62] and PLA [58], Door handle attachments manufactured in ABS [63], Hand sanitizer holders, valves. Likewise, Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) is used in biomedical structures [[64], [65], [66]]. Equally, composite filaments for biomedical applications have been made PVC and PP filaments reinforcement of hydroxyapatite powder (HAp) [67].

Another type of material that has been gaining interest in the field of 3D printing are hydrogels, which are being used in various applications such as drug administration [68,69], heavy metal removal [70], tissue engineering [71,72], ophthalmology [73] and biosensors [74], among other applications.

Table 2 shows a non-extensive list of materials used in 3D printing in recent years, in which the most relevant properties, the technologies used for their application and the most frequent uses at the productive level are indicated.

Table 2.

Some materials used currently in 3DP applications.

| Material | Properties | Technologies | Use | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Biocompatibility, degradability | fused deposition modeling (FDM) | Musculoskeletal tissue engineering, implants and microneedles | [75,76] |

| Poly-D,l-Lactic acid (PDLLA) | Biocompatibility hydrophobic | FDM | Orthopedic rehabilitation and tissue engineering | [77] |

| Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) | Heat endurance, robust impact strength | FDM and selective laser sintering (SLS) | Cartilage engineering technologies | [78] |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | hydrophilic, Used as bioink | stereolithography (SLA) | Drug delivery system, tissue engineering scaffold formation, | [79] |

| Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) | Nonbiodegradable | FDM | Orthopedic applications | [64] |

| Poly-glycolic acid (PGA) | Biocompatibility, degradation products not toxic | FDM | Bone internal fixation devices and in preparation of resorbable sutures. | [80] |

| Poly Caprolactone (PCL) | Stiffness, nontoxic, biocompatibility, and degradability. | SLS | Bone regeneration and cell ingrowth capability. | [79] |

| Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT) | Biocompatible, degrade in aqueous media | FDM and SLA | Canine bones and in tissue regeneration | [81] |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Biodegradable elastomer, biocompatibility | SLA and DLP | Cartilage tissue engineering, bone fabrication, construction of muscle and nerve scaffolds | [82] |

| Poly-vinyl alcohol (PVA) | Biocompatible, biodegradable, bioinert, and semi-crystalline | SLS | Craniofacial defect treatment and bone tissue engineering applications, Tablets | [83] |

| Polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) | Biodegradable | FDM | Bone regeneration animal and tissue-restoring systems | [84] |

| Stainless steel | Excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical properties | directed energy deposition (DED) | Bone Plates, Bone screws and pins, Wires | [85] |

| Cobalt Chromium Alloys | high resistance to corrosion, biocompatibility | Selective Laser Melting (SLM) | artificial joints (hips and knees), dental partial bridges | [86] |

| Copper alloys | High thermic and electric conductivity, biostatic | SLM | electrical wiring | [87] |

| Titanium Matrix Composites | Good resistance to oxidation, high strength at elevated temperature | binder jetting | Implants in the field of orthopedics and dentistry | [88] |

| Alumina (aluminum oxide) | High hardness, good resistance to corrosion and temperature changes. | Powder Bed Selective Laser Processing (PBSLP) | General engineering applications. | [89] |

| Zirconia (ZrO2) | Superior thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties | PBSLP | Electronics and biomedical | [89] |

| Calcium phosphate | Chemical resistance, biocompatibility | PBSLP | Medical applications | [89] |

| Silicon carbide | high mechanical stiff-ness, low density, low coefficient of expansion, high thermal stability, and resistance to corrosive environments, | PBSLP | High-power microwave devices for commercial and military systems; electronic devices; high temperature electronics/optics for automotive, aerospace | [89] |

It is important to consider that a process of disinfection of printed models must be carried out and for this it is necessary to have knowledge about the effectiveness of the chosen disinfectant product and if it can cause any dimensional alteration in the printed material [90]. The disinfection process can be divided into three categories according to the level of effectiveness: High-level disinfection involves the inactivity of most pathogenic microorganisms. The intermediate level implies the destruction of microorganisms, and the low level promotes little antimicrobial activity [91]. Table 3 Shows a list of disinfectants for coronavirus (COVID-19) approved by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Table 3.

Disinfectants for coronavirus (COVID-19) [92].

| Active Ingredient(s) | Contact Time (min)i | Formulation Typei | Surface Typei | Use Sitei |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary ammonium | 10 | Dilutable | HN; FCR; P (laundry presoak only) | Healthcare; Institutional; Residential |

| Quaternary ammonium | 10 | Dilutable | HN; FCR; P (laundry presoak only) | Healthcare; Institutional; Residential |

| Quaternary ammonium | 10 | Dilutable | HN; FCR; P (laundry presoak only) | Healthcare; Institutional; Residential |

| Quaternary ammonium | 10 | Dilutable | HN; FCR; P (laundry presoak only) | Healthcare; Institutional; Residential |

| Sodium carbonate peroxyhydrate; Tetraacetyl ethylenediamine | 15 | Dilutable | HN; P (laundry) | Healthcare; Institutional; Residential |

| Peroxyacetic acid (Peracetic acid); Hydrogen peroxide | 5 | Dilutable | P (laundry) | Healthcare; Institutional |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Consult user manual or label | Vapor (use in conjunction with VHP generator) | HN; P; FCNR | Institutional |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Consult user manual or label | Vapor (use in conjunction with VHP generator) | HN; P | Institutional |

| Quaternary ammonium | 5 | Dilutable | P (laundry presoak only) | Residential |

| Sodium chlorite | Consult user manual or label | Gas (use in conjunction with DRS equipment) | HN; P | Healthcare; Institutional |

HN: Hard Nonporous; FCR: Food Contact Post-Rinse Required; P: Porous; FCNR: Food Contact No Rinse.

Additive manufacturing of various types of polymers is a well-developed practice that supplies medical devices and personalized devices. Recent and current examples of PPEs made from polymeric materials include masks, protectors, and vents, among others [93]. On the other hand, there is great potential for AM to manufacture respirators and other PPEs, based on metal dust, to meet the huge requirement in the present pandemic. Therefore, these areas will increase the demand for metal dust in the coming years [94]. According to Hsiao et al. [95], 3DP is viable as a response to the manufacture of emergency drugs in solid oral dosage forms that could help vulnerable patients in rural or isolated areas. In addition, Zuniga and Cortes [96] affirm that a polymeric structure with copper nanoparticles exhibits an antimicrobial action superior to micro particles or metal surfaces, and they also state that copper is more convenient than stainless steel to mitigate the viability of COVID-19. Therefore, these antimicrobial polymers could significantly contribute for the advancement of clinical components by applying 3DP.

Table 4 summarizes the materials used to fabricate some PPE elements that are manufactured by companies that supply 3D printing.

Table 4.

Materials used to make PPE.

| Company | Products | Material | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hewlett–Packard Company | Swabs, Masks and adjusters, Face shields, Breathing apparatus components, Hands-free door openers, | PA12 | [32] |

| 3D Systems | Face masks and shields, Ventilator components, | Nylon | [105] |

| Stratasys Inc. | Face shields | PLA | [106] |

| Prusa3D | Personal Protective Wear | PETG | [107] |

| University of Sunderland | Door opener | PLA | [108] |

| Formalabs | Swabs | PA12 | [26] |

| MatterHackers | Face shields | PLA, PETG, ABS | [109] |

| Ultimaker | Face shields | PLA, PETG, ABS | [110] |

7. Applications

As mentioned before, 3D printing has made possible the conception and elaboration of various devices and elements, elaborated through 3DP, which have made it possible to help in the task of preventing the spread and helping in the treatment of patients infected with COVID-19. The literature review has identified some specific applications such as the development of 3D printed robotic arms [97], a printable adapter for medical headlamps [98], the development of a reusable face mask prototype custom printed [62], the development of medical face shields [[99], [100], [101]], the development of a UV-C disinfection environment for medical observation environments [102], and creating face shields and manufacturing disinfection tunnels [103]. [104] developed a PPE that allows the entry of oxygen or compressed air behind the head and provides an outflow close to the nose.

Jacob et al. [111] designed an endotracheal tube clamp that allows for clamping or release during intubation or extubation and other procedures such as suction for use in COVID-19 patients. Hung et al. [112] conceived a negative pressure protective defense for extubation of patients with COVID-19. François et al. [63] have developed a door opener without hands, a door hook and a push button in order to reduce the risks of contagion with COVI-19 by reducing direct friction. Chen et al. [113] made a door handle to mitigate COVID-19 hand infection. For their part, Pecchia et al. [114] warn about the use of vacuum cleaner filter materials as face mask filters, since they could put the user's safety at risk due to the eventual presence of dangerous glass microfibers.

8. Proposals and initiatives

In order to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, various initiatives have been proposed by researchers around the world. In this sense, Tino et al. [115] highlight some recent efforts and contributions made by companies, hospitals, and researchers to use 3D printing. According to Scott et al. [116], a way in which 3D printers can be implemented as shared solutions in schools or municipal centers to be used by vulnerable communities should be explored, facilitating the use of essential supplies to expand the chances of survival in cases such as those currently experienced. For their part, Sarkis et al. [117] propose that supply and production systems be well located and supported by technologies such as additive manufacturing, generating a trend towards “glocalization”, which is “the location of the global network and the joint consideration of global aspects and local”. Likewise, Paramasivam et al. [118] propose the manufacture of human organs by 3D printing, which can be used in preoperative training activities, or for the analysis and diagnosis of diseased limbs. Similarly, Lockhart et al. [119] propose to promote the development of EPPs through 3D printing for health professionals. On the other hand, Armani et al. [120] propose the Exchange of 3D impressions in Institutes of Health as an open resource supported on the web that would allow locating, sharing, and making medical application models that can be printed in 3D system. The initiatives presented here are synthesized samples in Table 5 . Thus, AM should be taken into consideration as a technology that can give real and massive support not only to health issues, but also to other worldwide problems that require other type of fabrication, using networks or even individuals working at home in their own machine.

Table 5.

Proposed initiatives to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Initiative | Aspect treated | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Role of 3D printing in medicine in relation to patients with COVID-19 | contributions made by companies, hospitals and researchers to use 3D printing | [115] |

| Public policy implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and Possible avenues for future research related to COVID-19. | Investigate several of the most pressing issues that have emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic | [116] |

| implications for employment and industrial structures and impacts of this reconstruction process | It is proposed that production systems should be supported by technologies such as AM. | [117] |

| Fabrication of human organs by AM | 3D printing of human anatomical models for surgical planning | [118] |

| Keeping healthcare providers safe and sound by maintaining the availability of adequate PPE supplies | framework for understanding the principles and practices surrounding PPE decision making. | [119] |

| Exchange of 3D prints in Institutes of Health as an open resource supported on the web | Location, sharing and modeling of medical applications that can be printed on a 3D system | [120] |

9. Conclusion

From this research it has been evident the notable role of a manufacturing technique in the world pandemic COVID-19, which is important not only for the humanitarian and economical contributions, but also because it shows a route for the success of massive and future technologies: the collaborative work, the manufacturing from companies with important facilities to the manufacturing from individuals from their houses. The pandemic has been spreading for more than six months intensively causing world damages, enough to reveal a significant amount of diverse literature and evidence of other information regarding the AM technology use contribution to mitigate the COVID-19 threat. In addition, the importance of collaboration between scientists is highlighted, as well as that of entrepreneurs and innovators from all areas, who, thanks to global connectivity, can develop, adapt, and share ideas that will ultimately preserve the existence of our species. All of this experience is without a doubt not only one of the most significant contributions of AM in its relatively low history, but also is a landmark for technologies to face the new world and survive as evolutionary technologies able to solve challenges that go beyond the commercialization and economic impacts. It is notable that the 3DP materials involved in the pandemic COVID-19 started from polymers, to a wider alloys and ceramics. Composites and perhaps engineering ceramics will be the next generation of materials in devices though to compose components in varied applications but developed to minimize the virus transmission or with disinfection of surfaces purposes. Certainly, the innovations in these areas will give companies an advantage in the new post pandemic world. This study has shown the practical positive implications that advanced manufacturing technologies such as AM can have in contributing to a worldwide problem is appropriately used, Since technologies as AM can be adapted to new manufacturing, artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things, and other top-notch developments, massive solutions can be given in short time with participation of engineers and many other actors elsewhere. This aspect represents a hope not only for future pandemics, but also for other world scale issues that require a global response via high technology. Thus, from the theoretical or academic point of view, the search for these new developments can motivate high impact and large-scale solutions for other issues such as virus, famine, water and energy demand, among other megatrends. Clearly this study shows that AM changed the way manufacturing was always conceived, now everyone and elsewhere can make parts and machines, and even work out of an industrial traditional environment, at home.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We agree with paper submission, evaluation, and possible publication by JMRT.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to the Universidad de Antioquia and the Antonio Nariño University for the support for the development of this work. Likewise, they express their gratitude to the “Hacer para Salvar” group for the support provided.

Biographies

Henry A. Colorado is a Professor at the Universidad Antioquia, Colombia, and director of the CCComposites group. He is an active member of The Materials and Minerals Society, ABM Brazil, and from the American Ceramics Society. Henry works in solid waste utilization, 3D printing, and in the development of composite materials. Henry obtained a PhD in Materials Science from UCLA in 2013.

David E Mendoza is a Mechanical Engineering from Universidad de Antioquia. David is leading 3D printing technology in Medellin with industrial solutions to several sectors and is part of the COVID 19 support for several hospitals.

Hua-Tay Lin is a Distinguished Professor in the School of Electromechanical Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, at Guangzhou, China. He is a leading researcher in the manufacturing of ceramics. Prof. Lin is a Fellow of the American Ceramic Society and ASM International, and Academician of the World Academy of Ceramics.

Elkin Gutierrez-Velasquez is an Associate Professor from Universidad Antonio Nariño, Colombia. He is expert in sensors, numerical modeling and additive manufacturing. Elkin obtained his PhD in Mechanical Engineering at the Universidade Federal de Itajubá, Brazil.

References

- 1.Ju C. Work motivation of safety professionals: a person-centred approach. Saf Sci. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardito L., Coccia M., Messeni Petruzzelli A. R and D Management; 2021. Technological exaptation and crisis management: evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks; p. 51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gevaert C.M., Carman M., Rosman B., Georgiadou Y., Soden R. Fairness and accountability of AI in disaster risk management: opportunities and challenges. Patterns. 2021;2:100363. doi: 10.1016/J.PATTER.2021.100363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaziri R., Miralam M.S. The impact of crisis and disasters risk management in COVID-19 times: insights and lessons learned from Saudi Arabia. Ethics, Med Public Health. 2021;18:100705. doi: 10.1016/J.JEMEP.2021.100705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burhan M., Salam M.T., Hamdan O.A., Tariq H. Crisis management in the hospitality sector SMEs in Pakistan during COVID-19. Int J Hospit Manag. 2021;98:103037. doi: 10.1016/J.IJHM.2021.103037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng J., Huang J., Pan L. How to balance acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19: the protocols from Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1111–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., Ristenpart W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci Technol. 2020;54:635–638. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin R., Maur B.W. di. 2021. Economics in the time of covid-19 | VOX. [CEPR Policy Portal n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes N. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. SSRN Electron J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3557504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skeel D. 2020. Bankruptcy and the coronavirus: Part II. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson I., Rosen D.W., Stucker B. Springer; US: 2010. Additive manufacturing technologies: rapid prototyping to direct digital manufacturing. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordoñez E., Gallego J.M., Colorado H.A. 3D printing via the direct ink writing technique of ceramic pastes from typical formulations used in traditional ceramics industry. Appl Clay Sci. 2019;182 doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2019.105285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngo T.D., Kashani A., Imbalzano G., Nguyen K.T.Q., Hui D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): a review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos B Eng. 2018;143:172–196. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colorado H.A., Gutiérrez-Velásquez E.I., Monteiro S.N. Sustainability of additive manufacturing: the circular economy of materials and environmental perspectives. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9:8221–8234. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.04.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colorado H.A., Mendoza D.E., Valencia F.L. A combined strategy of additive manufacturing to support multidisciplinary education in arts, biology, and engineering. J Sci Educ Technol. 2020;30:58–73. doi: 10.1007/S10956-020-09873-1. 2020 30:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vergara L.A., Colorado H.A. Additive manufacturing of Portland cement pastes with additions of kaolin, superplastificant and calcium carbonate. Construct Build Mater. 2020;248:118669. doi: 10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2020.118669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revelo C.F., Colorado H.A. 3D printing of kaolinite clay with small additions of lime, fly ash and talc ceramic powders. Processing and Appl Ceramics. 2019;13:287–299. doi: 10.2298/PAC1903287R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha M.S., Bourgeois F.T., Sorger P.K. Personal protective equipment for COVID-19: distributed fabrication and additive manufacturing. Am J Publ Health. 2020;110:1162–1164. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce J.M. A review of open source ventilators for COVID-19 and future pandemics. F1000Research. 2020;9:218. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22942.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallup N., Pringle A.M., Oberloier S., Tanikella N.G., Pearce J.M. 2020. Parametric nasopharyngeal swab for sampling COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses: open source design, SLA 3-D printing and UV curing system. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holst A. 2020. Companies utilizing 3D printing to provide medical supplies during COVID-19 pandemic. Statista 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Additive manufacturing magazine. 2021. [n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox J.L., Koepsell S.A. 3D-Printing to address COVID-19 testing supply shortages. Lab Med. 2021;51:E45–E46. doi: 10.1093/LABMED/LMAA031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vordos N., Gkika D.A., Maliaris G., Tilkeridis K.E., Antoniou A., Bandekas D.V., et al. How 3D printing and social media tackles the PPE shortage during Covid – 19 pandemic. Saf Sci. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Formlabs . 2020. 3D printed test swabs for COVID-19 testing.https://formlabs.com/covid-19-response/covid-test-swabs/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thingiverse . 2020. Digital designs for physical objects.https://www.thingiverse.com/search?q=covid&type=things&sort=relevant [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Institutes of Health . 2020. COVID-19 supply chain response.https://3dprint.nih.gov/collections/covid-19-response [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prusa_Research. 3D printed face shields for medics and professionals. 2020. https://www.prusa3d.com/covid19/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.MatterHackers . 2020. COVID-19 additive manufacturing response.https://www.matterhackers.com/covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ultimaker . 2020. Guidance on 3D printing and design support for COVID-19.https://assets.ctfassets.net/7cnpidfipnrw/5AFVjyATJPhGQQctDMCfK5/757b08d9af5e7b7ae5d34da7e5ac2593/Guidance_on_3D_printing_and_design_support_for_COVID-19_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belhouideg S. Impact of 3D printed medical equipment on the management of the Covid 19 pandemic. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hpm.3009. hpm.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleischer J.C., Diehl J.C., Wauben L.S.G.L., Dankelman J. The effect of chemical cleaning on mechanical properties of three-dimensional printed polylactic acid. J Med Dev Trans ASME. 2020;14 doi: 10.1115/1.4046120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Barneveld K., Quinlan M., Kriesler P., Junor A., Baum F., Chowdhury A., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ Lab Relat Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1035304620927107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Queiroz M.M., Ivanov D., Dolgui A., Fosso Wamba S. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann Oper Res. 2020:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rapaccini M., Saccani N., Kowalkowski C., Paiola M., Adrodegari F. Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: the impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Ind Market Manag. 2020;88:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bapuji H., de Bakker F.G.A., Brown J.A., Higgins C., Rehbein K., Spicer A. Business and society research in times of the corona crisis. Bus Soc. 2020;59:1067–1078. doi: 10.1177/0007650320921172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antwi-Afari M.F., Li H. Fall risk assessment of construction workers based on biomechanical gait stability parameters using wearable insole pressure system. Adv Eng Inf. 2018;38:683–694. doi: 10.1016/J.AEI.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagaria V., Sahu D. Orthopaedics in times of COVID 19. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54:400–401. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acuto M. COVID-19: lessons for an urban(izing) world. One Earth. 2020;2:317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iyengar K., Bahl S., Raju Vaishya, Vaish A. Challenges and solutions in meeting up the urgent requirement of ventilators for COVID-19 patients. Diabetes and Metabol Synd: Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.048. Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mostaghimi A., Antonini M.-J., Plana D., Anderson P.D., Beller B., Boyer E.W., et al. Regulatory and safety considerations in deploying a locally fabricated, reusable, face shield in a hospital responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/J.MEDJ.2020.06.003. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishack S., Lipner S.R. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19–related supply shortages. Am J Med. 2020;133:771–773. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thierry B., Célérier C., Simon F., Lacroix C., Khonsari R.-H.H. 2020. How and why use the EasyBreath® Decathlon surface snorkeling mask as a personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic? European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erickson M.M.M.M., Richardson E.S.E.S., Hernandez N.M.N.M., Bobbert D.W.D.W., Gall K., Fearis P. Helmet modification to PPE with 3D printing during the COVID-19 pandemic at duke university medical center: a novel technique. J Arthroplasty. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaishya R., Haleem A., Vaish A., Javaid M. Emerging technologies to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Experiment Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ji Z., Pons D.J., Pearse J. Integrating occupational health and safety into plant simulation. Saf Sci. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazingi D., Navarro S., Bobel M.C., Dube A., Mbanje C., Lavy C. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on progress towards achieving global surgery goals. World J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05627-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deshmukh S.G., Haleem A. Framework for manufacturing in post-covid-19 world order: an Indian perspective. Int J Global Business and Competitiveness. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s42943-020-00009-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahajan G. J Creat Value. 2020;6:7–9. doi: 10.1177/2394964320922937. Editorial. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Javaid M., Haleem A., Vaishya R., Bahl S., Suman R., Vaish A. Industry 4.0 technologies and their applications in fighting COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes and Metabol Synd: Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chhabra H.S., Bagaraia V., Keny S., Kalidindi K.K.V., Mallepally A., Dhillon M.S., et al. COVID-19: current knowledge and best practices for orthopaedic surgeons. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54:411–425. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haleem A., Javaid M., Khan I.H., Vaishya R. Significant applications of big data in COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Orthop. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandolla C., Petruzzelli A.M., Percoco G., Urbinati A. Building a digital twin for additive manufacturing through the exploitation of blockchain: a case analysis of the aircraft industry. Comput Ind. 2019;109:134–152. doi: 10.1016/J.COMPIND.2019.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.B A P N.L., Buradi A N.S., B L P R.V. A comprehensive review of emerging additive manufacturing (3D printing technology): methods, materials, applications, challenges, trends and future potential. Mater Today Proc. 2021 doi: 10.1016/J.MATPR.2021.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y., Mao J., Wu J. Microwave transparent crosslinked polystyrene nanocomposites with enhanced high voltage resistance via 3D printing bulk polymerization method. Compos Sci Technol. 2018;157:160–167. doi: 10.1016/J.COMPSCITECH.2018.01.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dul S., Fambri L., Pegoretti A. Fused deposition modelling with ABS–graphene nanocomposites. Compos Appl Sci Manuf. 2016;85:181–191. doi: 10.1016/J.COMPOSITESA.2016.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin-Noguerol T., Paulano-Godino F., Menias C.O., Luna A. Lessons learned from COVID-19 and 3D printing. AJEM (Am J Emerg Med) 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams E., Bond K., Isles N., Chong B., Johnson D., Druce J., et al. Pandemic printing: a novel 3D-printed swab for detecting SARS-CoV-2. Med J Aust. 2020;213:276–279. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Callahan C.J., Lee R., Zulauf K.E., Tamburello L., Smith K.P., Previtera J., et al. Open development and clinical validation of multiple 3d-printed nasopharyngeal collection swabs: rapid resolution of a critical covid-19 testing bottleneck. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00876-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jafferson J.M., Pattanashetti S. Use of 3D printing in production of personal protective equipment (PPE) - a review. Mater Today Proc. 2021;46:1247–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swennen G.R.J., Pottel L., Haers P.E. Custom-made 3D-printed face masks in case of pandemic crisis situations with a lack of commercially available FFP2/3 masks. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.François P.M., Bonnet X., Kosior J., Adam J., Khonsari R.H. 3D-printed contact-free devices designed and dispatched against the COVID-19 pandemic: the 3D COVID initiative. J Stomatol, Oral and Maxillofacial Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li S., Wang T., Hu J., Li Z., Wang B., Wang L., et al. Surface porous poly-ether-ether-ketone based on three-dimensional printing for load-bearing orthopedic implant. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;120:104561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Horn M.R., Beard R., Wang W., Cunningham B.W., Mullinix K.P., Allall M., et al. Comparison of 3D-printed titanium-alloy, standard titanium-alloy, and PEEK interbody spacers in an ovine model. Spine J. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rezvani Ghomi E., Eshkalak S.K., Singh S., Chinnappan A., Ramakrishna S., Narayan R. Fused filament printing of specialized biomedical devices: a state-of-the art review of technological feasibilities with PEEK. Rapid Prototyp J. 2021;27:592–616. doi: 10.1108/RPJ-06-2020-0139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ranjan N., Kumar R. On processing of PVC-PP-hap thermoplastic composite filaments for 3D printing in biomedical applications. Int J Eng Trends Technol. 2021;69:160–164. doi: 10.14445/22315381/IJETT-V69I2P222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dreiss C.A. Hydrogel design strategies for drug delivery. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;48:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2020.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kamlow M.A., Vadodaria S., Gholamipour-Shirazi A., Spyropoulos F., Mills T. 3D printing of edible hydrogels containing thiamine and their comparison to cast gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;116:106550. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pei R., Fan L., Zhao F., Xiao J., Yang Y., Lai A., et al. 3D-Printed metal-organic frameworks within biocompatible polymers as excellent adsorbents for organic dyes removal. J Hazard Mater. 2020;384:121418. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laird N.Z., Acri T.M., Chakka J.L., Quarterman J.C., Malkawi W.I., Elangovan S., et al. Applications of nanotechnology in 3D printed tissue engineering scaffolds. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2021;161:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Melchels F.P.W., Domingos M.A.N., Klein T.J., Malda J., Bartolo P.J., Hutmacher D.W. Additive manufacturing of tissues and organs. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:1079–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zidan G., Greene C.A., Etxabide A., Rupenthal I.D., Seyfoddin A. Gelatine-based drug-eluting bandage contact lenses: effect of PEGDA concentration and manufacturing technique. Int J Pharm. 2021;599:120452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kalkal A., Kumar S., Kumar P., Pradhan R., Willander M., Packirisamy G., et al. Recent advances in 3D printing technologies for wearable (bio)sensors. Additive Manufact. 2021;46:102088. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2021.102088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vanaei H., Shirinbayan M., Deligant M., Raissi K., Fitoussi J., Khelladi S., et al. Influence of process parameters on thermal and mechanical properties of polylactic acid fabricated by fused filament fabrication. Polym Eng Sci. 2020;60:1822–1831. doi: 10.1002/pen.25419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vanaei H.R., Deligant M., Shirinbayan M., Raissi K., Fitoussi J., Khelladi S., et al. A comparative in-process monitoring of temperature profile in fused filament fabrication. Polym Eng Sci. 2021;61:68–76. doi: 10.1002/pen.25555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang P.C., Luo H.T., Lin Z.J., Tai W.C., Chang C.H., Chang Y.C., et al. Preclinical evaluation of a 3D-printed hydroxyapatite/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffold for ridge augmentation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khan I., Kumar N. Fused deposition modelling process parameters influence on the mechanical properties of ABS: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2020;44:4004–4008. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.202. Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bose S., Sarkar N., Banerjee D. Effects of PCL, PEG and PLGA polymers on curcumin release from calcium phosphate matrix for in vitro and in vivo bone regeneration. Mater Today Chem. 2018;8:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ye J., Chu T., Chu J., Gao B., He B. A versatile approach for enzyme immobilization using chemically modified 3d-printed scaffolds. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019 doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun S., Gan X., Wang Z., Fu D., Pu W., Xia H. Dynamic healable polyurethane for selective laser sintering. Additive Manufact. 2020;33:101176. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2020.101176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marcos-Fernández Á.A., Navarro R., Benito E., Guzmán J., Garrido L. Properties of polyurethanes derived from poly(diethylene glycol terephthalate) Eur Polym J. 2021;155:110576. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parhi R. Fabrication and characterization of PVA-based green materials. Adv Green Mater. 2021:133–177. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-819988-6.00009-4. Elsevier. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carlier E., Marquette S., Peerboom C., Amighi K., Goole J. Development of mAb-loaded 3D-printed (FDM) implantable devices based on PLGA. Int J Pharm. 2021;597:120337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mitra I., Bose S., Dernell W.S., Dasgupta N., Eckstrand C., Herrick J., et al. 3D Printing in alloy design to improve biocompatibility in metallic implants. Mater Today. 2021;45:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2020.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang H., Lim J.Y. Metal-ceramic bond strength of a cobalt chromium alloy for dental prosthetic restorations with a porous structure using metal 3D printing. Comput Biol Med. 2019;112:103364. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang C., Ouyang D., Pauly S., Liu L. 3D printing of bulk metallic glasses. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2021;145:100625. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2021.100625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yadav P., Fu Z., Knorr M., Travitzky N. Binder jetting 3D printing of titanium aluminides based materials: a feasibility study. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22 doi: 10.1002/adem.202000408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grossin D., Montón A., Navarrete-Segado P., Özmen E., Urruth G., Maury F., et al. A review of additive manufacturing of ceramics by powder bed selective laser processing (sintering/melting): calcium phosphate, silicon carbide, zirconia, alumina, and their composites. Open Ceramics. 2021;5:100073. doi: 10.1016/j.oceram.2021.100073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Azevedo M.J., Correia I., Portela A., Sampaio-Maia B. A simple and effective method for addition silicone impression disinfection. J Adv Prosthodontics. 2019;11:155. doi: 10.4047/JAP.2019.11.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sartori IA.de M., Rocha Bernardes S., Soares D., Thomé G. 2020. Biosafety and disinfection of impression materials for dental prosthetics professionals. [Google Scholar]

- 92.United States Environmental Protection Agency . 2021. List N tool: COVID-19 disinfectants.https://cfpub.epa.gov/wizards/disinfectants/ US EPA. [Google Scholar]

- 93.AlMaadeed M.A. Emergent materials and industry 4.0 contribution toward pandemic diseases such as COVID-19. Emergent Materials. 2020;3:107–108. doi: 10.1007/s42247-020-00102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kaitwade N. COVID-19 Shatters global automotive industry; Sales of metal powder take a nosedive amid wavering demand. Met Powder Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mprp.2020.06.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hsiao W.-K., Lorber B., Paudel A. Can 3D printing of oral drugs help fight the current COVID-19 pandemic (and similar crisis in the future)? Expet Opin Drug Deliv. 2020 doi: 10.1080/17425247.2020.1772229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zuniga J.M., Cortes A. The role of additive manufacturing and antimicrobial polymers in the COVID-19 pandemic. Expet Rev Med Dev. 2020;17:477–481. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2020.1756771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeldovich L. The robot will see you NowRoboticists worldwide are joining the fight against pandemics. Mech Eng. 2020;142:34–39. doi: 10.1115/1.2020-JUN1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Viera-Artiles J., Valdiande J.J.J.J. 3D-printable headlight face shield adapter. Personal protective equipment in the COVID-19 era. Am J Otolaryngol - Head and Neck Med Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shokrani A., Loukaides E.G., Elias E., Lunt A.J.G. Exploration of alternative supply chains and distributed manufacturing in response to COVID-19; a case study of medical face shields. Mater Des. 2020;192 doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neijhoft J., Viertmann T., Meier S., Söhling N., Wicker S., Henrich D., et al. Manufacturing and supply of face shields in hospital operation in case of unclear and confirmed COVID-19 infection status of patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amin D., Nguyen N., Roser S.M.S.M., Abramowicz S. 3D printing of face shields during COVID-19 pandemic: a technical note. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.She R.C., Chen D., Pak P., Armani D.K., Schubert A., Armani A.M. 2020. Build-at-home UV-C disinfection system for healthcare settings. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shah A.U.M., Safri S.N.A., Thevadas R., Noordin N.K., Rahman A.A., Sekawi Z., et al. COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia: actions taken by the Malaysian government. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maracaja L., Blitz D., Maracaja D.L.V., Walker C.A. W.B. Saunders; 2020. How 3D printing can prevent spread of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals during times of critical shortage of protective personal equipment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.COVID-19 digital manufacturing and 3D printing Response| 3D systems. 2021. [n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Files and instructions for 3D printing personal protective equipment. 2021. [n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Updated April 2nd - From design to mass 3D printing of medical shields in three days. 2021. [Prusa Printers n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 108.University researchers create 3D printed door opener to help fight the spread of COVID-19. 2021. [Education Technology n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 109.COVID-19 additive manufacturing response. 2021. [USA | MatterHackers n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 110.How engineers and manufactures can collaborate to combat COVID-19. 2021. [n.d] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jacob M., Ruivo E., Portela I., Tavares J., Varela M., Moutinho S., et al. An innovative endotracheal tube clamp for use in COVID-19. Can J Anesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01703-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hung O., Hung D., Hung C., Stewart R. A simple negative-pressure protective barrier for extubation of COVID-19 patients. Can J Anesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen K.-L., Wang S.-J., Chuang C., Huang L.-Y., Chiu F.-Y., Wang F.-D., et al. Novel design for door handle—a potential technology to reduce hand contamination in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pecchia L., Piaggio D., Maccaro A., Formisano C., Iadanza E. The inadequacy of regulatory frameworks in time of crisis and in low-resource settings: personal protective equipment and COVID-19. Health Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12553-020-00429-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tino R., Moore R., Antoline S., Ravi P., Wake N., Ionita C.N., et al. COVID-19 and the role of 3D printing in medicine. 3D Printing in Med. 2020;6 doi: 10.1186/s41205-020-00064-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scott M.L., Martin K.D., Wiener J.L., Ellen P.S., Burton S. vol. 39. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2020. (The COVID-19 pandemic at the intersection of marketing and public policy). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sarkis J., Cohen M.J., Dewick P., Schröder P. A brave new world: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for transitioning to sustainable supply and production. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020;159 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paramasivam V., Sindhu, Singh G., Santhanakrishnan S. 3D printing of human anatomical models for preoperative surgical planning. Procedia Manuf. 2020;48:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2020.05.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lockhart S.L., Duggan L.v., Wax R.S., Saad S., Grocott H.P. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for both anesthesiologists and other airway managers: principles and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01673-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Armani A.M., Hurt D.E., Hwang D., McCarthy M.C., Scholtz A. Low-tech solutions for the COVID-19 supply chain crisis. Nat Rev Mater. 2020;5:403–406. doi: 10.1038/s41578-020-0205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]